Submitted:

03 January 2026

Posted:

05 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- We propose a unified and challenge-centric taxonomy that systematically organizes federated learning research across the entire FL pipeline, explicitly highlighting the interdependencies and trade-offs among six foundational challenges, rather than treating them in isolation.

- We provide a comprehensive synthesis of state-of-the-art methods for each challenge category, critically analyzing their underlying assumptions, algorithmic designs, theoretical guarantees, empirical performance, and practical limitations across diverse deployment settings.

- We conduct an in-depth examination of emerging learning paradigms, including meta-learning, personalized federated learning, self-supervised learning, contrastive learning, and continual learning, and elucidate how these paradigms intersect with, extend, and reshape classical federated learning formulations.

- We identify open research problems and unresolved bottlenecks at the algorithmic, system, and application levels, and outline promising future research directions toward building scalable, communication-efficient, robust, and trustworthy federated learning systems.

2. Background & Foundations

2.1. Definition of Federated Learning

2.2. Architecture for a Federated Learning System

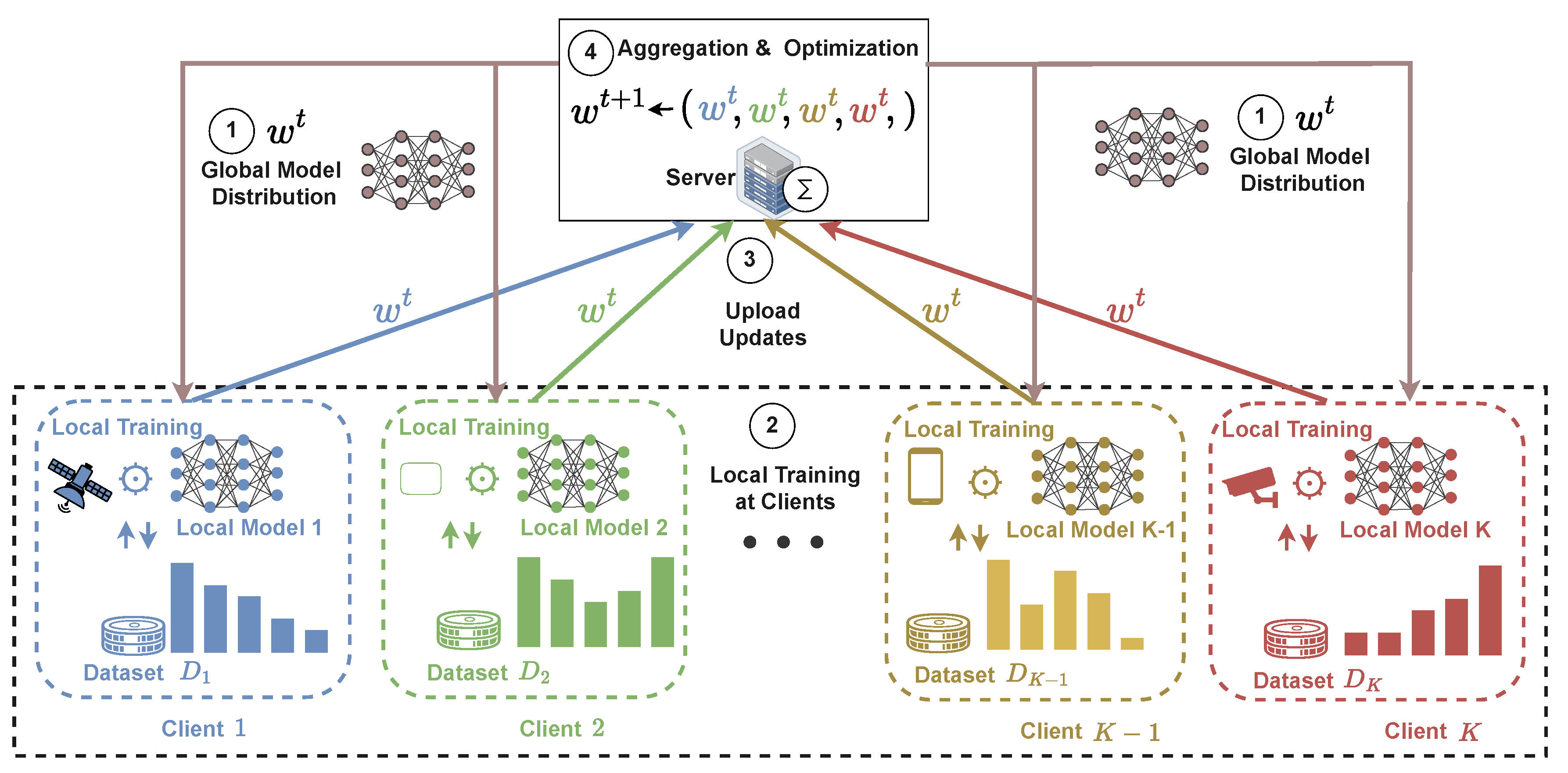

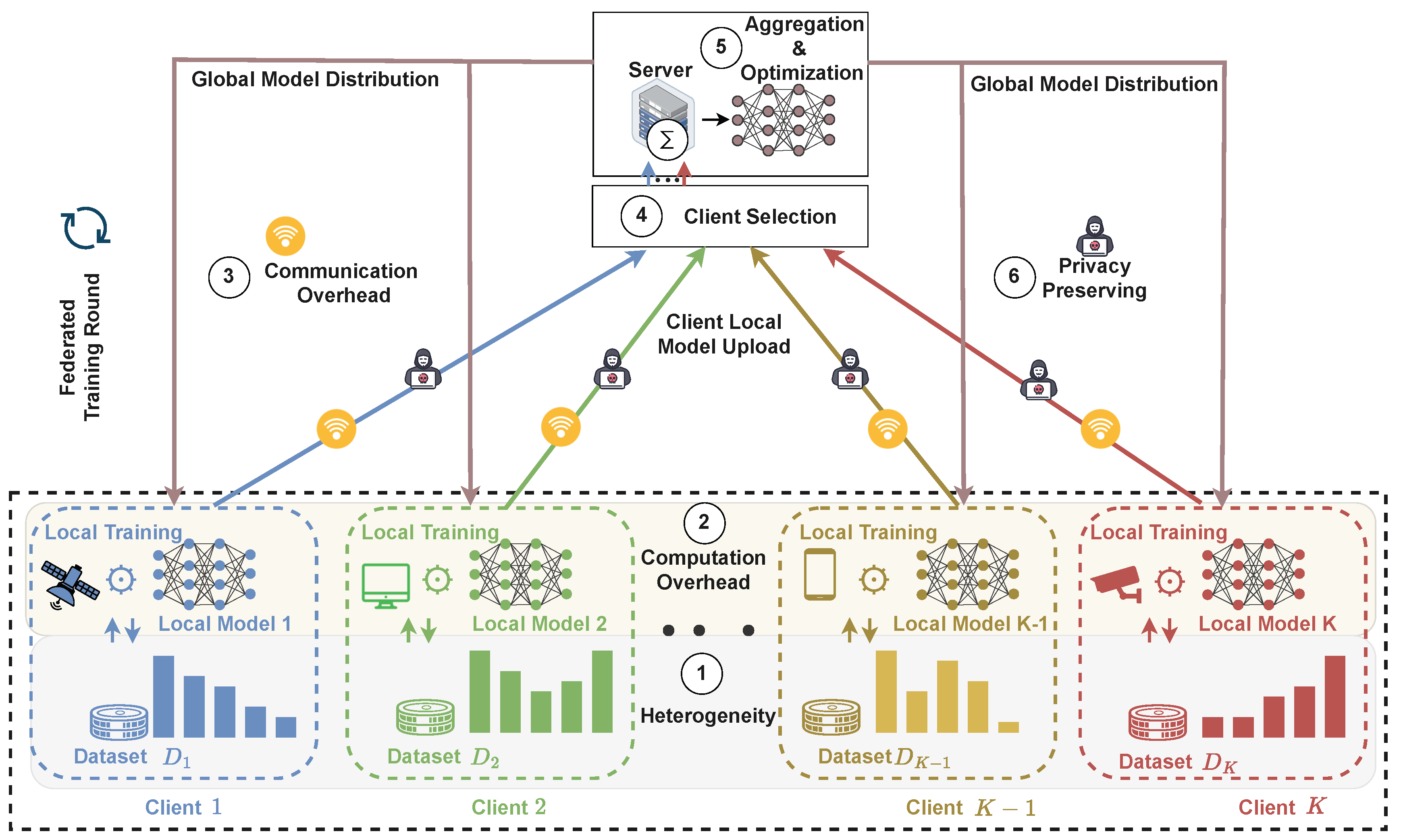

- Step 1(Global Model Distribution): At communication round t, the server maintains the current global model and selects a subset of available clients for participation. The server broadcasts along with basic training settings, such as the learning rate and number of local training epochs.

- Step 2(Local Training at Clients): Each selected client k updates the received global model using its own local dataset . All clients begin local training from the same model parameters and perform training independently, while all data remain stored and processed locally.

- Step 3(Model Update Upload): After completing local training, each participating client sends its updated model parameters (or model changes relative to ) back to the server. Only model-related information is communicated; the underlying datasets are never shared.

- Step 4(Model Aggregation at the Server): The server aggregates the updates received from participating clients to form the next global model . The aggregation reflects the collective contribution of the clients, commonly accounting for differences in local dataset sizes.

- Step 5(Iterative Model Refinement): The updated global model is redistributed to clients, and Steps 1–4 are repeated over multiple communication rounds until convergence or a predefined stopping criterion is met. The final outcome is a single global model learned collaboratively across decentralized datasets.

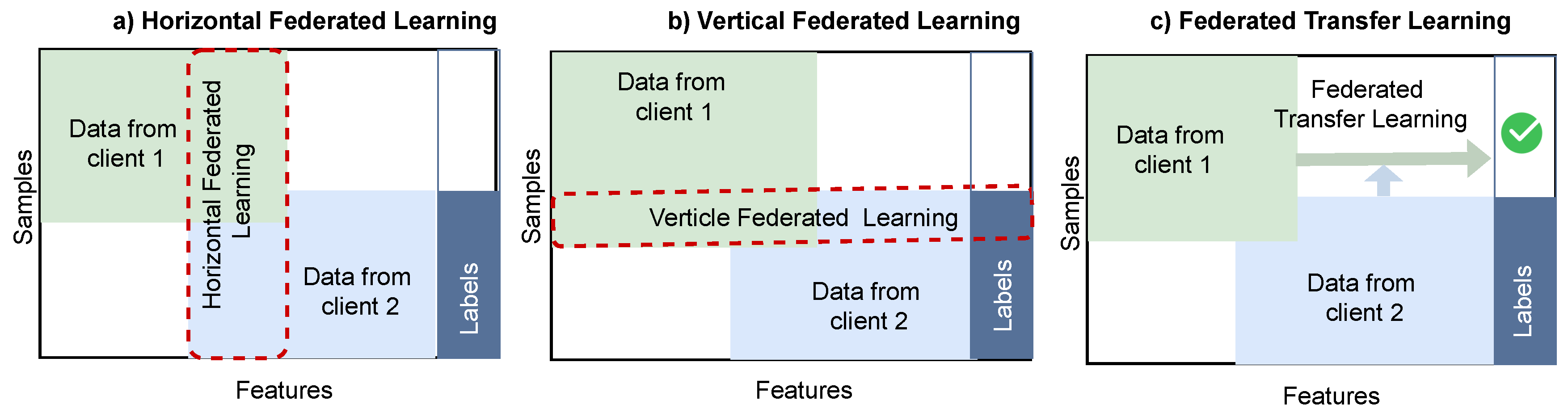

2.3. A Categorization of Federated Learning

2.3.1. Horizontal Federated Learning (HFL)

2.3.2. Vertical Federated Learning (VFL)

2.3.3. Federated Transfer Learning (FTL)

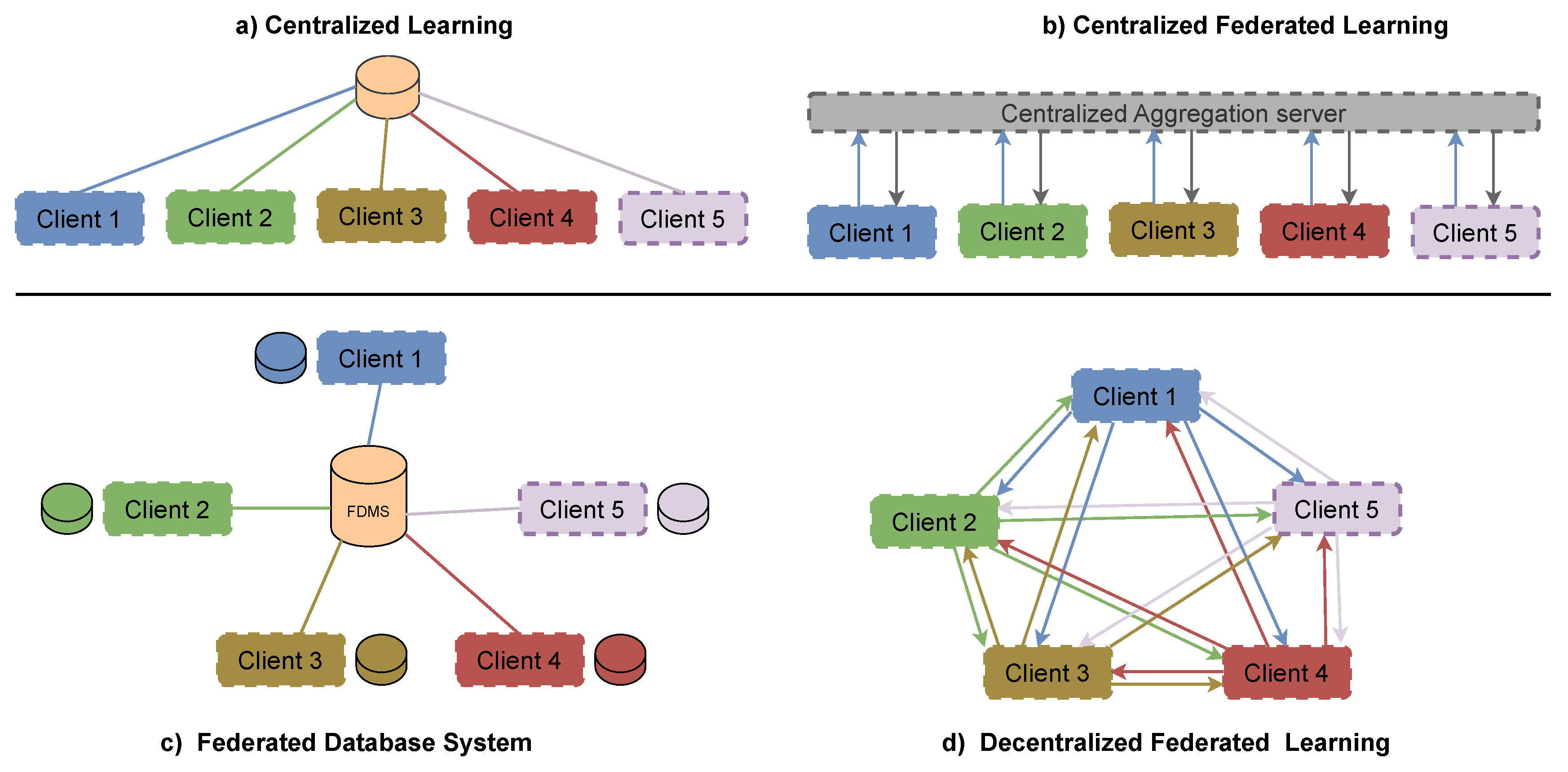

2.4. Centralized, Federated, and Decentralized Learning

2.4.1. Centralized Learning

2.4.2. Centralized Federated Learning

2.4.3. Federated Database Systems

2.4.4. Decentralized Federated Learning

2.5. Federated Learning Versus Edge Computing

2.5.1. Edge Computing

2.5.2. Federated Learning

2.5.3. Conceptual Relationship

2.5.4. Learning and Communication Perspective

2.5.5. Complementarity and Integration

| Notation | Description |

|---|---|

| K | Total number of clients participating in FL |

| k | Client index, |

| Local dataset stored at client k | |

| Number of samples at client k | |

| n | Total number of samples, |

| i-th data sample (feature vector) at client k | |

| Corresponding label of | |

| w | Global model parameters |

| Global model at communication round t | |

| Local model of client k at round t | |

| d | Dimensionality of model parameters, |

| Global objective function | |

| Local objective function at client k | |

| Sample-wise loss function | |

| Aggregation weight of client k, | |

| Learning rate | |

| E | Number of local training epochs per round |

| t | Communication round index |

| Set of clients selected at round t |

| Acronym | Meaning |

|---|---|

| FL | Federated Learning |

| HFL | Horizontal Federated Learning |

| VFL | Vertical Federated Learning |

| FTL | Federated Transfer Learning |

| PFL | Personalized Federated Learning |

| DFL | Decentralized Federated Learning |

| FedAvg | Federated Averaging |

| IID | Independent and Identically Distributed |

| Non-IID | Non-Identically Distributed Data |

| SGD | Stochastic Gradient Descent |

| DP | Differential Privacy |

| SMPC | Secure Multi-Party Computation |

| HE | Homomorphic Encryption |

| TEE | Trusted Execution Environment |

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| P2P | Peer-to-Peer |

| QoS | Quality of Service |

| NAS | Neural Architecture Search |

| GNN | Graph Neural Network |

3. Related Surveys

4. Survey Protocol and Taxonomy

4.0.6. Research Methodology and Research Questions

- RQ1: What are the major research directions, system architectures, and application domains of federated learning across academia and industry?

- RQ2: What fundamental challenges arise when deploying federated learning in realistic, large-scale, and heterogeneous environments?

- RQ3: What algorithmic techniques, system designs, and optimization strategies have been proposed to address these challenges?

- RQ4: How do these challenges interact across the federated learning pipeline, and what trade-offs emerge among communication efficiency, optimization performance, privacy guarantees, fairness, and robustness?

- RQ5: Which challenges remain insufficiently addressed, and what open problems and research opportunities emerge from current limitations?

4.0.7. Search Strategy

4.0.8. Study Selection Criteria

4.0.9. Taxonomy Construction

5. Challenge 1: Heterogeneity

6. Challenge 2: Computation Overhead

7. Challenge 3: Communication Bottlenecks

8. Challenge 4: Client Selection

9. Challenge 5: Aggregation and Optimization

10. Challenge 6: Privacy Preservation

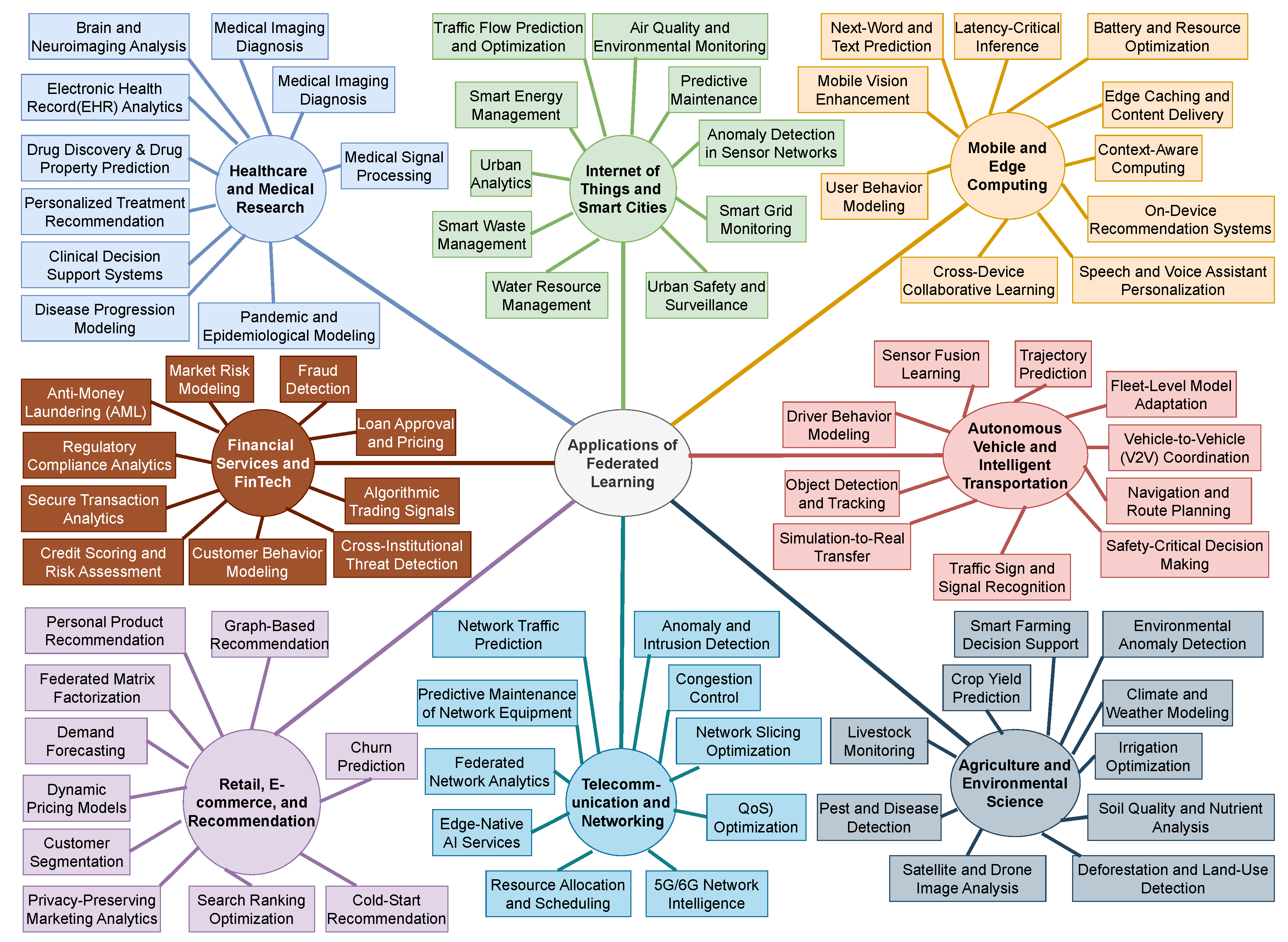

11. Applications of Federated Learning

12. Open Source Systems

13. Future Directions

14. Conclusion

References

- Kuutti, S.; Bowden, R.; Jin, Y.; Barber, P.; Fallah, S. A Survey of Deep Learning Applications to Autonomous Vehicle Control. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems 2021, 22, 712–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozaffari, S.; Al-Jarrah, O.Y.; Dianati, M.; Jennings, P.; Mouzakitis, A. Deep Learning-Based Vehicle Behavior Prediction for Autonomous Driving Applications: A Review. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems 2022, 23, 33–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Lu, S.; Zhong, R.; Wu, B.; Yao, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Shi, W. Computing Systems for Autonomous Driving: State of the Art and Challenges. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2021, 8, 6469–6486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Zheng, Y.; Han, X.; et al. A Systematic Literature Review on Integrating AI-Powered Smart Glasses into Digital Health Management for Proactive Healthcare Solutions. npj Digital Medicine 2025, 8, 410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yalcin, N.; Alisawi, M. Enhancing Social Interaction for the Visually Impaired: A Systematic Review of Real-Time Emotion Recognition Using Smart Glasses and Deep Learning. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 102092–102108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, M.L. A Review of Developments and Metrology in Machine Learning and Deep Learning for Wearable IoT Devices. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 106035–106054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, J.; Hsiang, E.L.; He, Z.; et al. Augmented Reality and Virtual Reality Displays: Emerging Technologies and Future Perspectives. Light: Science & Applications 2021, 10, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberatore, M.J.; Wagner, W.P. Virtual, Mixed, and Augmented Reality: A Systematic Review for Immersive Systems Research. Virtual Reality 2021, 25, 773–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, Y.; Liu, H.; Zhang, Z. Advancements in Humanoid Robots: A Comprehensive Review and Future Prospects. IEEE/CAA Journal of Automatica Sinica 2024, 11, 301–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpentier, J.; Wieber, P.B. Recent Progress in Legged Robots Locomotion Control. Current Robotics Reports 2021, 2, 231–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotha, S.S.; Akter, N.; Abhi, S.H.; Das, S.K.; Islam, M.R.; Ali, M.F.; Ahamed, M.H.; Islam, M.M.; Sarker, S.K.; Badal, M.F.R.; et al. Next Generation Legged Robot Locomotion: A Review on Control Techniques. Heliyon 2024, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, F.; Mohanta, J.C.; Keshari, A.; et al. Recent Advances in Unmanned Aerial Vehicles: A Review. Arabian Journal for Science and Engineering 2022, 47, 7963–7984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Küçükerdem, H.; Yilmaz, C.; Kahraman, H.T.; et al. Autonomous Control of Unmanned Aerial Vehicles: Applications, Requirements, Challenges. Cluster Computing 2025, 28, 734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohsan, S.A.H.; Othman, N.Q.H.; Li, Y.; et al. Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs): Practical Aspects, Applications, Open Challenges, Security Issues, and Future Trends. Intelligent Service Robotics 2023, 16, 109–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Analytics, IoT. State of IoT 2025: Number of connected IoT devices growing 1421.1 billion globally and projected to 39 billion by 2030. Available online: https://iot-analytics.com/number-connected-iot-devices/ (accessed on 2025 October 16).

- Fayyad, U.; Piatetsky-Shapiro, G.; Smyth, P. The KDD process for extracting useful knowledge from volumes of data. Commun. ACM 1996, 39, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shearer, C. The CRISP-DM Model: The New Blueprint for Data Mining. 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Baylor, D.; Breck, E.; Cheng, H.T.; et al. TFX: A TensorFlow-Based Production-Scale Machine Learning Platform. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 23rd ACM SIGKDD Int. Conf. on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Mohd Noor, M.H.; Ige, A.O. A survey on state-of-the-art deep learning applications and challenges. Engineering Applications of Artificial Intelligence 2025, 159, 111225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baduwal, M. Hybrid(Transformer+CNN)-based Polyp Segmentation. arXiv 2025, arXiv:eess. [Google Scholar]

- General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). 2016. Available online: https://gdpr.eu/.

- California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA). 2018. Available online: https://oag.ca.gov/privacy/ccpa.

- Challenges of Centralized Machine Learning in Modern Data Ecosystems. arXiv 2020.

- Silver, D.; Huang, A.; Maddison, C.J.; Guez, A.; Sifre, L.; van den Driessche, G.; Schrittwieser, J.; Antonoglou, I.; Panneershelvam, V.; Lanctot, M.; et al. Mastering the Game of Go with Deep Neural Networks and Tree Search. Nature 2016, 529, 484–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NVIDIA. Nemotron 3 Nano: Open, Efficient Mixture-of-Experts Hybrid Mamba-Transformer Model for Agentic Reasoning, 2025. Technical report.

- Team, Q. Qwen3 Technical Report. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2505.09388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ChatGPT: Proprietary AI Agent and Conversational Assistant Closed-source large language model agent for conversational AI and automated workflows. OpenAI Product 2025.

- Microsoft Copilot: AI-Driven Agentic Assistance Enterprise-grade proprietary agent integrated with Microsoft 365 and developer tools. Microsoft Product 2025.

- Google Antigravity: Proprietary Agent-First AI IDE. Google Product Agent-centric proprietary coding environment powered by Gemini 3 Pro and integrated agents. 2025.

- Anthropic Claude with Opus Agentic Capabilities Proprietary agentic reasoning and task automation enhancements in Claude powered by Opus 4.5. Anthropic AI Model 2025.

- IBM watsonx: Enterprise-Grade Proprietary AI Agents. IBM Product Suite, 2025. Proprietary AI agents and orchestration within IBM’s watsonx platform for businesses.

- McMahan, B.; Moore, E.; Ramage, D.; Hampson, S.; y Arcas, B.A. Communication-efficient learning of deep networks from decentralized data. In Proceedings of the Artificial intelligence and statistics. PMLR, 2017; pp. 1273–1282. [Google Scholar]

- European Data Protection Supervisor. Opinion on privacy and federated learning. 2020. Available online: https://edps.europa.eu.

- Mothukuri, V.; Parizi, R.M.; Pouriyeh, S.; Huang, Y.; Dehghantanha, A.; Srivastava, G. A survey on security and privacy of federated learning. Future Generation Computer Systems 2021, 115, 619–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federated Learning: Applications and Opportunities. In Frontiers in Artificial Intelligence; 2021.

- Federated Learning for Medical Applications. In Frontiers in Medicine; 2021.

- McMahan, B.; Moore, E.; Ramage, D.; Hampson, S. Communication-Efficient Learning of Deep Networks from Decentralized Data. Proceedings of AISTATS, 2017 . [Google Scholar]

- Federated Intelligence in Smart Cities. In Frontiers in Sustainable Cities; 2021.

- Federated Learning for COVID-19 Diagnosis and Analysis. In Nature Communications; 2020.

- Privacy-preserving Analytics during the COVID-19 Pandemic with Federated Learning. In PMC; 2020.

- Stripelis, D.; Ambite, J.L.; Lam, P.; Thompson, P. Scaling neuroscience research using federated learning. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 18th international symposium on biomedical imaging (ISBI), Ieee, 2021; pp. 1191–1195. [Google Scholar]

- Stripelis, D.; Gupta, U.; Saleem, H.; Dhinagar, N.; Ghai, T.; Anastasiou, C.; Sánchez, R.; Ver Steeg, G.; Ravi, S.; Naveed, M.; et al. A federated learning architecture for secure and private neuroimaging analysis. Patterns 2024, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Gu, Y.; Dvornek, N.; Staib, L.H.; Ventola, P.; Duncan, J.S. Multi-site fMRI analysis using privacy-preserving federated learning and domain adaptation: ABIDE results. Medical image analysis 2020, 65, 101765. [Google Scholar]

- Thapaliya, B.; et al. Efficient Federated Learning for Distributed Neuroimaging Data. Frontiers in Neuroinformatics 2024, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadilek, A.; Liu, L.; Nguyen, D.; Kamruzzaman, M.; Serghiou, S.; Rader, B.; Ingerman, A.; Mellem, S.; Kairouz, P.; Nsoesie, E.O.; et al. Privacy-first health research with federated learning. NPJ digital medicine 2021, 4, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Glicksberg, B.S.; Su, C.; Walker, P.; Bian, J.; Wang, F. Federated learning for healthcare informatics. Journal of healthcare informatics research 2021, 5, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Miao, D.; Wu, Q.; Hong, C.; D’Agostino, D.; Li, X.; Ning, Y.; Shang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Liu, M.; et al. Federated learning in healthcare: A benchmark comparison of engineering and statistical approaches for structured data analysis. Health Data Science 2024, 4, 0196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diniz, J.M. The Missing Subject in Health Federated Learning: Preventive and Personalized Care. In Federated Learning Systems: Towards Privacy-Preserving Distributed AI; Springer, 2025; pp. 107–127. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, W.; Luo, J.; White, A.D. Federated learning of molecular properties with graph neural networks in a heterogeneous setting. Patterns 2022, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Y.; Gao, Y.; Song, J. Molcfl: A personalized and privacy-preserving drug discovery framework based on generative clustered federated learning. Journal of biomedical informatics 2024, 157, 104712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smajić, A.; Grandits, M.; Ecker, G.F. Privacy-preserving techniques for decentralized and secure machine learning in drug discovery. Drug Discovery Today 2023, 28, 103820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Xue, D.; Chuai, G.; Yang, Q.; Liu, Q. FL-QSAR: a federated learning-based QSAR prototype for collaborative drug discovery. Bioinformatics 2020, 36, 5492–5498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C. Breaking data silos in drug discovery with federated learning. Nature Chemical Engineering 2025, 2, 288–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.; Ye, X.; Sakurai, T. Multi-party collaborative drug discovery via federated learning. Computers in Biology and Medicine 2024, 171, 108181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanser, T.; Ahlberg, E.; Amberg, A.; Anger, L.T.; Barber, C.; Brennan, R.J.; Brigo, A.; Delaunois, A.; Glowienke, S.; Greene, N.; et al. Data-driven federated learning in drug discovery with knowledge distillation. Nature Machine Intelligence 2025, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oldenhof, M.; et al. Industry-Scale Orchestrated Federated Learning for Drug Discovery. Proceedings of the Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence 2023, Vol. 37, 497–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dritsas, E.; Trigka, M.; Kavallieros, D. Federated Learning for IoT: A Survey of Techniques, Challenges, and Applications. Sensors 2025, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- War, M.R.; Singh, Y.; Sheikh, Z.A.; Singh, P.K. Review on the Use of Federated Learning Models for the Security of Cyber-Physical Systems. Scalable Computing: Practice and Experience 2025, 26, 16–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Huang, X.; Dai, Y.; Maharjan, S.; Zhang, Y. Federated Learning for Data Privacy Preservation in Vehicular Cyber-Physical Systems. IEEE Network 2020, 34, 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, G.; Tan, Y.; Jiang, J.; Zhang, C. Federated Learning for Open Banking. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2108.10749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awosika, T.; Shukla, R.M.; Pranggono, B. Transparency and Privacy: The Role of Explainable AI and Federated Learning in Financial Fraud Detection. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 64551–64560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Xiao, J.; Wang, L.; Yao, J. A novel federated learning approach with knowledge transfer for credit scoring. Decision Support Systems 2024, 177, 114084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Cai, L.; Lu, W.S. Federated Learning for Data Trading Portfolio Allocation With Autonomous Economic Agents. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems 2025, 36, 1467–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abadi, A.; Doyle, B.; Gini, F.; Guinamard, K.; Murakonda, S.K.; Liddell, J.; Mellor, P.; Murdoch, S.J.; Naseri, M.; Page, H.; et al. Starlit: Privacy-Preserving Federated Learning to Enhance Financial Fraud Detection. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2401.10765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMahan, H.B.; Moore, E.; Ramage, D.; Hampson, S.; y Arcas, B.A. Communication-Efficient Learning of Deep Networks from Decentralized Data. arXiv 2023, arXiv:1602.05629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalamala, S.R.; et al. Federated Learning to Comply with Data Protection Regulations. CSI Transactions on ICT 2022, 10, 47–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blika, A.; Palmos, S.; Doukas, G.; Lamprou, V.; Pelekis, S.; Kontoulis, M.; Ntanos, C.; Askounis, D. Federated Learning for Enhanced Cybersecurity and Trustworthiness in 5G and 6G Networks: A Comprehensive Survey. IEEE Open Journal of the Communications Society 2025, 6, 3094–3130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Chen, M.; Wong, K.K.; Poor, H.V.; Cui, S. Federated Learning for 6G: Applications, Challenges, and Opportunities. Engineering 2022, 8, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Solat, F.; Kim, T.Y.; Poor, H.V. Federated Learning-Empowered Mobile Network Management for 5G and Beyond Networks: From Access to Core. IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials 2024, 26, 2176–2212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Challenges and Future Directions in Federated Learning. arXiv 2022.

- A Comprehensive Survey of Challenges in Federated Learning. In Frontiers in AI; 2023.

- Survey of Federated Learning: Taxonomies and Challenges. IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials, 2022 .

- Finn, C.; Abbeel, P.; Levine, S. Model-Agnostic Meta-Learning for Fast Adaptation. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Contrastive Federated Learning: Mitigating Non-IID with Representation Learning. In Proceedings of the CVPR, 2021.

- Konečný, J.; McMahan, H.B.; Ramage, D.; Richtárik, P. Federated Optimization: Distributed Machine Learning for On-Device Intelligence. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1610.02527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konečný, J.; McMahan, H.B.; Yu, F.X.; Richtárik, P.; Suresh, A.T.; Bacon, D. Federated Learning: Strategies for Improving Communication Efficiency. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1610.05492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Sahu, A.K.; Talwalkar, A.; Smith, V. Federated learning: Challenges, methods, and future directions. IEEE Signal Processing Magazine, 2020 . [Google Scholar]

- Konečný, J.; et al. Federated Optimization: Distributed Machine Learning for On-Device Intelligence. In Proceedings of the arXiv, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Sheller, M.J.e.a. Federated learning in medicine: facilitating multi-institutional collaborations without sharing patient data. Scientific Reports 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, W.; Dustdar, S. Edge Computing: Vision and Challenges. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2016, 3, 637–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satyanarayanan, M. The Emergence of Edge Computing. Computer 2017, 50, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Sahu, A.K.; Talwalkar, A.; Smith, V. Federated Learning: Challenges, Methods, and Future Directions. IEEE Signal Processing Magazine 2020, 37, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, W.Y.B.; et al. Federated Learning in Mobile Edge Networks: A Comprehensive Survey. IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials 2020, 22, 2031–2063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Liu, Y.; Chen, T.; Tong, Y. Federated Machine Learning: Concept and Applications. ACM Trans. Intell. Syst. Technol. 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Sahu, A.K.; Talwalkar, A.; Smith, V. Federated Learning: Challenges, Methods, and Future Directions. IEEE Signal Processing Magazine 2020, 37, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kairouz, P.; McMahan, H.B.; et al. Advances and Open Problems in Federated Learning. In Foundations and Trends in Machine Learning; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Q.; Wen, Z.; Wu, Z.; Hu, S.; Wang, N.; Li, Y.; Liu, X.; He, B. A Survey on Federated Learning Systems: Vision, Hype and Reality for Data Privacy and Protection. IEEE Transactions on Knowledge and Data Engineering 2023, 35, 3347–3366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Huang, J.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, X.; Liu, S.; Gu, Q. From distributed machine learning to federated learning: a survey. Knowledge and Information Systems 2022, 64, 885–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Lv, N.; Guo, Y.; Li, Y. Recent advances on federated learning: A systematic survey. Neurocomputing 2024, 597, 128019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, J.; Zhang, Z.; Lan, Y.; Cui, Z.; Cai, J.; Zhang, W. A survey on federated learning: challenges and applications. International Journal of Machine Learning and Cybernetics 2023, 14, 513–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yurdem, B.; Kuzlu, M.; Gullu, M.K.; Catak, F.O.; Tabassum, M. Federated learning: Overview, strategies, applications, tools and future directions. Heliyon 2024, 10, e38137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, R.K.; Kumar, R.; Saxena, N. A systematic review on federated learning system: a new paradigm to machine learning. Knowledge and Information Systems 2025, 67, 1811–1914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasim, M.A.A.; Soshi, F.T.J.; Biswas, P.; Ferdous, A.S.M.A.; Rashid, A.; Biswas, A.; Gupta, K.D. Principles and Components of Federated Learning Architectures. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2502.05273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aledhari, M.; Razzak, R.; Parizi, R.M.; Saeed, F. Federated Learning: A Survey on Enabling Technologies, Protocols, and Applications. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 140699–140725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, S.K.; Lu, Q.; Wang, C.; Paik, H.Y.; Zhu, L. A Systematic Literature Review on Federated Machine Learning: From a Software Engineering Perspective. ACM Comput. Surv. 2021, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.; Alam, T. Survey on Federated-Learning Approaches in Distributed Environment. Wireless Personal Communications 2022, 125, 1631–1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pouriyeh, S.; Shahid, O.; Parizi, R.M.; Sheng, Q.Z.; Srivastava, G.; Zhao, L.; Nasajpour, M. Secure Smart Communication Efficiency in Federated Learning: Achievements and Challenges. Applied Sciences 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahlool, D.H.; Alsalihi, M.H. A Comprehensive Survey on Federated Learning: Concept and Applications. In Proceedings of the Mobile Computing and Sustainable Informatics; Singapore, Shakya, S., Ntalianis, K., Kamel, K.A., Eds.; 2022; pp. 539–553. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, D.C.; Ding, M.; Pathirana, P.N.; Seneviratne, A.; Li, J.; Vincent Poor, H. Federated Learning for Internet of Things: A Comprehensive Survey. IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials 2021, 23, 1622–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, W.Y.B.; Luong, N.C.; Hoang, D.T.; Jiao, Y.; Liang, Y.C.; Yang, Q.; Niyato, D.; Miao, C. Federated Learning in Mobile Edge Networks: A Comprehensive Survey. IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials 2020, 22, 2031–2063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahab, O.A.; Mourad, A.; Otrok, H.; Taleb, T. Federated Machine Learning: Survey, Multi-Level Classification, Desirable Criteria and Future Directions in Communication and Networking Systems. IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials 2021, 23, 1342–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mammen, P.M. Federated Learning: Opportunities and Challenges. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2101.05428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abreha, H.G.; Hayajneh, M.; Serhani, M.A. Federated Learning in Edge Computing: A Systematic Survey. Sensors 2022, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirohi, D.; Kumar, N.; Rana, P.S.; Verma, A.; Singh, M.; Kumar, G. Federated learning for 6G-enabled secure communication systems: a comprehensive survey. Artificial Intelligence Review 2023, 56, 11297–11389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albshaier, L.; Almarri, S.; Albuali, A. Federated Learning for Cloud and Edge Security: A Systematic Review of Challenges and AI Opportunities. Electronics 2025, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, N.; Qu, Z.; Ye, B.; Wang, Y.; Hu, S.; Guo, S. A Comprehensive Survey on Communication-Efficient Federated Learning in Mobile Edge Environments. IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials 2025, 1–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Fan, Y.; Tse, M.; Lin, K.Y. A review of applications in federated learning. Computers & Industrial Engineering 2020, 149, 106854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharati, S.; Mondal, M.R.H.; Podder, P.; Prasath, V.S. Federated learning: Applications, challenges and future directions. International Journal of Hybrid Intelligent Systems 2022, 18, 19–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moshawrab, M.; Adda, M.; Bouzouane, A.; Ibrahim, H.; Raad, A. Reviewing Federated Machine Learning and Its Use in Diseases Prediction. Sensors 2023, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moshawrab, M.; Adda, M.; Bouzouane, A.; Ibrahim, H.; Raad, A. Reviewing Federated Learning Aggregation Algorithms; Strategies, Contributions, Limitations and Future Perspectives. Electronics 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez Beltrán, E.T.; Pérez, M.Q.; Sánchez, P.M.S.; Bernal, S.L.; Bovet, G.; Pérez, M.G.; Pérez, G.M.; Celdrán, A.H. Decentralized Federated Learning: Fundamentals, State of the Art, Frameworks, Trends, and Challenges. IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials 2023, 25, 2983–3013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almanifi, O.R.A.; Chow, C.O.; Tham, M.L.; Chuah, J.H.; Kanesan, J. Communication and computation efficiency in Federated Learning: A survey. Internet of Things 2023, 22, 100742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco-Justicia, A.; Domingo-Ferrer, J.; Martínez, S.; Sánchez, D.; Flanagan, A.; Tan, K.E. Achieving security and privacy in federated learning systems: Survey, research challenges and future directions. Engineering Applications of Artificial Intelligence 2021, 106, 104468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhu, H.; Wang, F.; Zhao, J.; Xu, Q.; Li, H. Security and Privacy Threats to Federated Learning: Issues, Methods, and Challenges. Security and Communication Networks 2022, 2022, 2886795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, S.; Hota, A.; Chattopadhyay, A.K.; Banerjee, S.; De, D. A multifaceted survey on privacy preservation of federated learning: progress, challenges, and opportunities. Artificial Intelligence Review 2024, 57, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, K.; Gong, S.; Zhang, Q.; Cheng, S.; Li, Q.; Xu, Y. An overview of implementing security and privacy in federated learning. Artificial Intelligence Review 2024, 57, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.; Gupta, J. Federated learning using game strategies: State-of-the-art and future trends. Computer Networks 2023, 225, 109650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neto, H.N.C.; Hribar, J.; Dusparic, I.; Mattos, D.M.F.; Fernandes, N.C. A Survey on Securing Federated Learning: Analysis of Applications, Attacks, Challenges, and Trends. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 41928–41953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qammar, A.; Karim, A.; Ning, H.; Li, D.; Sajid, A.; Liu, X. Securing federated learning with blockchain: a systematic literature review. Artificial Intelligence Review 2023, 56, 3951–3985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, J.; Cao, J.; Saxena, D.; Jiang, S.; Ferradi, H. Blockchain-empowered Federated Learning: Challenges, Solutions, and Future Directions. ACM Comput. Surv. 2023, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, R. Federated Learning: A Survey on Privacy-Preserving Collaborative Intelligence. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2504.17703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tariq, A.; Serhani, M.A.; Sallabi, F.M.; Barka, E.S.; Qayyum, T.; Khater, H.M.; Shuaib, K.A. Trustworthy Federated Learning: A Comprehensive Review, Architecture, Key Challenges, and Future Research Prospects. IEEE Open Journal of the Communications Society 2024, 5, 4920–4998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, M.; Fang, X.; Du, B.; Yuen, P.C.; Tao, D. Heterogeneous Federated Learning: State-of-the-art and Research Challenges. ACM Comput. Surv. 2023, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; He, K.; Chen, X. Personalized Federated Learning for Intelligent IoT Applications: A Cloud-Edge Based Framework. IEEE Open Journal of the Computer Society 2020, 1, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, A.Z.; Yu, H.; Cui, L.; Yang, Q. Towards Personalized Federated Learning. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems 2023, 34, 9587–9603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Zhang, H.; Jin, Y. From federated learning to federated neural architecture search: a survey. Complex & Intelligent Systems 2021, 7, 639–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, L.; Wang, J.; Zhou, Y.; Ma, F. Multimodal Federated Learning: A Survey. Sensors 2023, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niknam, S.; Dhillon, H.S.; Reed, J.H. Federated Learning for Wireless Communications: Motivation, Opportunities and Challenges. arXiv 2020, arXiv:eess. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, V.; Kulkarni, M.; Pant, A. Survey of Personalization Techniques for Federated Learning. In Proceedings of the 2020 Fourth World Conference on Smart Trends in Systems, Security and Sustainability (WorldS4), 2020; pp. 794–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.; Zhu, Y.; Hu, J. A Comprehensive Survey of Privacy-preserving Federated Learning: A Taxonomy, Review, and Future Directions. ACM Comput. Surv. 2021, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, L.U.; Saad, W.; Han, Z.; Hossain, E.; Hong, C.S. Federated Learning for Internet of Things: Recent Advances, Taxonomy, and Open Challenges. IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials 2021, 23, 1759–1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, D.; Yao, X.; Yang, Q. A Survey on Heterogeneous Federated Learning. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2210.04505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asad, M.; Shaukat, S.; Hu, D.; Wang, Z.; Javanmardi, E.; Nakazato, J.; Tsukada, M. Limitations and Future Aspects of Communication Costs in Federated Learning: A Survey. Sensors 2023, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alotaibi, B.; Khan, F.A.; Mahmood, S. Communication Efficiency and Non-Independent and Identically Distributed Data Challenge in Federated Learning: A Systematic Mapping Study. Applied Sciences 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Q.; Jiang, S.; Jiang, L.; Huang, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Khan, S.; Dai, W.; Liu, Z.; Wu, K. Efficiency Optimization Techniques in Privacy-Preserving Federated Learning With Homomorphic Encryption: A Brief Survey. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2024, 11, 24569–24580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, H.; Rani, V.; Kumar, M.; Singh, A.; Gupta, S. Federated learning: a comprehensive review of recent advances and applications. Multimedia Tools and Applications 2024, 83, 54165–54188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimireddy, S.P.; Kale, S.; Mohri, M.; Reddi, S.; Stich, S.; Suresh, A.T. SCAFFOLD: Stochastic Controlled Averaging for Federated Learning. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 37th International Conference on Machine Learning; III PMLR; H.D. Singh, A., Ed.; Proceedings of Machine Learning Research, 13-18 Jul 2020; Vol. 119, pp. 5132–5143. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, Z.; Meng, L.; Chen, Z.; Hu, H.; Lin, H.; Meng, X. Cross-Silo Prototypical Calibration for Federated Learning with Non-IID Data. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 31st ACM International Conference on Multimedia, New York, NY, USA, 2023; MM ’23, pp. 3099–3107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Z.; Zhou, S.; Meng, L.; Hu, H.; Yu, H.; Meng, X. Federated Deconfounding and Debiasing Learning for Out-of-Distribution Generalization. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2505.04979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Dai, W.; Huang, W.; Chen, J. Geometric Knowledge-Guided Localized Global Distribution Alignment for Federated Learning. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), June 2025; pp. 20958–20968. [Google Scholar]

- McMahan, B.; Moore, E.; Ramage, D.; Hampson, S.; Arcas, B.A. Communication-Efficient Learning of Deep Networks from Decentralized Data. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 20th International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Statistics; Singh, A., Zhu, J., Eds.; PMLR; Proceedings of Machine Learning Research, 20-22 Apr 2017; Vol. 54, pp. 1273–1282. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Q.; Diao, Y.; Chen, Q.; He, B. Federated Learning on Non-IID Data Silos: An Experimental Study. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 38th International Conference on Data Engineering (ICDE), 2022; pp. 965–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Sahu, A.K.; Zaheer, M.; Sanjabi, M.; Talwalkar, A.; Smith, V. Federated Optimization in Heterogeneous Networks. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of Machine Learning and Systems; Dhillon, I., Papailiopoulos, D., Sze, V., Eds.; 2020; Vol. 2, pp. 429–450. [Google Scholar]

- Yurochkin, M.; Agarwal, M.; Ghosh, S.; Greenewald, K.; Hoang, N.; Khazaeni, Y. Bayesian Nonparametric Federated Learning of Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 36th International Conference on Machine Learning; Chaudhuri, K., Salakhutdinov, R., Eds.; PMLR; Proceedings of Machine Learning Research, 09-15 Jun 2019; Vol. 97, pp. 7252–7261. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.; Li, M.; Lai, L.; Suda, N.; Civin, D.; Chandra, V. Federated Learning with Non-IID Data. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, M.; Chen, F.; Hu, D.; Zhang, Y.; Liang, J.; Feng, J. No Fear of Heterogeneity: Classifier Calibration for Federated Learning with Non-IID Data. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; Ranzato, M., Beygelzimer, A., Dauphin, Y., Liang, P., Vaughan, J.W., Eds.; Curran Associates, Inc., 2021; Vol. 34, pp. 5972–5984. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, H.; Hu, Z.; Yang, L.; Zheng, M.; Xu, A.; Wang, B. FedCALM: Conflict-aware Layer-wise Mitigation for Selective Aggregation in Deeper Personalized Federated Learning. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), June 2025; pp. 15444–15453. [Google Scholar]

- Dennis, D.K.; Li, T.; Smith, V. Heterogeneity for the Win: One-Shot Federated Clustering. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 38th International Conference on Machine Learning; Meila, M., Zhang, T., Eds.; PMLR; Proceedings of Machine Learning Research, 18-24 Jul 2021; Vol. 139, pp. 2611–2620. [Google Scholar]

- Stallmann, M.; Wilbik, A. Towards Federated Clustering: A Federated Fuzzy c-Means Algorithm (FFCM). arXiv 2022, arXiv:cs. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, C.; Sima, J.; Prakash, S.; Rana, V.; Milenkovic, O. Machine Unlearning of Federated Clusters. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2210.16424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Chen, H.Y.; Chao, W.L.; Zhang, Y. Jigsaw Game: Federated Clustering. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2407.12764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, D.; Ding, C.; Fan, J. Federated Spectral Clustering via Secure Similarity Reconstruction. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; Oh, A., Naumann, T., Globerson, A., Saenko, K., Hardt, M., Levine, S., Eds.; Curran Associates, Inc., 2023; Vol. 36, pp. 58520–58555. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Chang, T.H. Federated Matrix Factorization: Algorithm Design and Application to Data Clustering. IEEE Transactions on Signal Processing 2022, 70, 1625–1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Liu, J.; Ning, Y.Z.; Zhang, Z.Y. SDA-FC: Bridging federated clustering and deep generative model. Information Sciences 2024, 681, 121203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Fu, L.; Ye, F.; Liao, T.; Deng, B.; Zhang, C.; Chen, C. Soft-consensual Federated Learning for Data Heterogeneity via Multiple Paths.

- Fang, X.; Ye, M.; Du, B. Robust Asymmetric Heterogeneous Federated Learning With Corrupted Clients. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 2025, 47, 2693–2705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.; Ye, M. Noise-Robust Federated Learning With Model Heterogeneous Clients. IEEE Transactions on Mobile Computing 2025, 24, 4053–4071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Fu, L.; Li, Y.; Chen, C.; Zheng, Z.; Dai, H.N. A Cross-Client Coordinator in Federated Learning Framework for Conquering Heterogeneity. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems 2025, 36, 8828–8842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Z.; Meng, L.; Li, Z.; Hu, H.; Meng, X. Cross-Silo Feature Space Alignment for Federated Learning on Clients with Imbalanced Data. Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence 2025, 39, 19986–19994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, H.; Ma, J.; Xiong, L.; Yang, C. Federated Graph Classification over Non-IID Graphs. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; Ranzato, M., Beygelzimer, A., Dauphin, Y., Liang, P., Vaughan, J.W., Eds.; Curran Associates, Inc., 2021; Vol. 34, pp. 18839–18852. [Google Scholar]

- Baek, J.; Jeong, W.; Jin, J.; Yoon, J.; Hwang, S.J. Personalized Subgraph Federated Learning. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 40th International Conference on Machine Learning PMLR; Krause, A., Brunskill, E., Cho, K., Engelhardt, B., Sabato, S., Scarlett, J., Eds.; Proceedings of Machine Learning Research, 23-29 Jul 2023; Vol. 202, pp. 1396–1415. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Tian, X.; Peng, H.; Liu, T.; Han, B. Fedfed: Feature distillation against data heterogeneity in federated learning. Advances in neural information processing systems 2023, 36, 60397–60428. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, Y.; Fu, H.; Li, Y.; Xie, J.; Ma, J.; Yang, G.; Zhu, L. A Simple Data Augmentation for Feature Distribution Skewed Federated Learning. arXiv 2024, arXiv:cs. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Wang, Z.; Wang, Z.; Fan, X.; Wang, C. Federated Learning with Domain Shift Eraser. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2503.13063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Li, S.; Li, A.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, F.; Zhu, C.; Zhang, L. Subspace Constraint and Contribution Estimation for Heterogeneous Federated Learning. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 2025; pp. 20632–20642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raswa, F.H.; Lu, C.S.; Wang, J.C. HistoFS: Non-IID Histopathologic Whole Slide Image Classification via Federated Style Transfer with RoI-Preserving. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Conference (CVPR), June 2025; pp. 30251–30260. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, H.; et al. FedMP: Federated Learning with Model Pruning for Efficient Communication and Computation. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems, 2022 . [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Wen, Y.; et al. LotteryFL: Personalized and Communication-Efficient Federated Learning with Lottery Ticket Hypothesis. In Proceedings of the ICLR, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J. colleagues. Quantized Federated Learning: Optimizing Training Efficiency for Edge Devices. IEEE Internet of Things Journal, 2022 . [Google Scholar]

- Seo, H.; et al. Federated Knowledge Distillation for Resource-Constrained Edge Devices. In Proceedings of the NeurIPS Workshop on Federated Learning, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, Y.; Lyu, L.; Chen, J. ScaleFL: Resource-Adaptive Federated Learning with Scalable Neural Networks. IEEE Transactions on Mobile Computing, 2022 . [Google Scholar]

- Diao, E.; Ding, J.; Tarokh, V. HeteroFL: Computation and Communication Efficient Federated Learning for Heterogeneous Clients. In Proceedings of the ICML, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, R.; et al. Sub-FL: Training Subnetworks for Efficient Federated Learning on Heterogeneous Devices. Pattern Recognition, 2022 . [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, S.; Raskar, R. Split Learning for Distributed Deep Learning. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1905.08821. [Google Scholar]

- Thapa, C.; Arachchige, P.; et al. SplitFed: When Federated Learning Meets Split Learning. In Proceedings of the ACL Workshop on Federated Learning, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, W.; et al. Hybrid Split-Pruned Federated Learning for Resource-Constrained Edge Devices. IEEE Transactions on Mobile Computing, 2023 . [Google Scholar]

- Lai, F.; et al. Oort: Efficient Federated Learning via Intelligent Client Selection. In Proceedings of the OSDI, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, F.; et al. Adaptive Federated Optimization for Heterogeneous Devices. Neurocomputing, 2022 . [Google Scholar]

- Xie, C.; et al. Asynchronous Federated Optimization. In Proceedings of the AISTATS, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; et al. Staleness-Aware Asynchronous Federated Learning. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems, 2021 . [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, T.D.; Pham, M.; Tran, T. Federated Learning with Buffered Asynchronous Aggregation. In Proceedings of the MLSys Conference, 2021 . [Google Scholar]

- He, C.; et al. Resource-Aware Federated Learning: Optimizing Performance under System Constraints. IEEE Transactions on Mobile Computing, 2021 . [Google Scholar]

- Aji, A.F.; Heafield, K. Sparse communication for distributed gradient descent. In Proceedings of the EMNLP, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Y.; Han, S. Deep gradient compression: Reducing the communication bandwidth for distributed training. In Proceedings of the ICLR, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Stich, S. Sparsified SGD with Memory. NeurIPS, 2018 . [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein, J.; et al. signSGD: Compressed Optimization for Non-Convex Problems. In Proceedings of the ICML, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Alistarh, D.; et al. QSGD: Communication-Efficient SGD via Gradient Quantization and Encoding. In Proceedings of the NeurIPS, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, W.; et al. TernGrad: Ternary Gradients to Reduce Communication in Distributed Deep Learning. In Proceedings of the NeurIPS, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Horvath, S.; et al. Natural Compression for Distributed Deep Learning. NeurIPS, 2019 . [Google Scholar]

- McMahan, B.; et al. Communication-Efficient Learning of Deep Networks from Decentralized Data. In Proceedings of the AISTATS, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; et al. Adaptive Federated Learning in Resource-Constrained Edge Computing Systems. In Proceedings of the IEEE INFOCOM, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Li, T.; et al. Federated Optimization in Heterogeneous Networks. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of MLSys, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, C.; et al. Asynchronous Federated Optimization. In Proceedings of the AISTATS, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; et al. Asynchronous Distributed Learning via Stale Gradient Methods. IEEE Journal on Selected Areas in Communications, 2019 . [Google Scholar]

- Lalitha, A.; et al. Peer-to-Peer Federated Learning on Graphs. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1901.11173. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, S.; et al. Communication-Efficient Edge-Assisted Federated Learning. In Proceedings of the IEEE GLOBECOM, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bonawitz, K.; et al. Towards Federated Learning at Scale: System Design. In Proceedings of the SysML, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Karimireddy, S.P.; et al. SCAFFOLD: Stochastic Controlled Averaging for Federated Learning. In Proceedings of the ICML, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Basu, D.; et al. Qsparse-local-SGD: Distributed SGD with Quantization, Sparsification, and Local Computation. In Proceedings of the NeurIPS, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Sattler, F.; et al. Clustered Federated Learning: Model-Agnostic Distributed Multi-Task Optimization. In Proceedings of the NeurIPS, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, Y.; et al. Towards Statistical-Quality-Aware Client Selection for Federated Learning. IEEE Transactions on Mobile Computing, 2022 . [Google Scholar]

- Tang, X.; Yu, Y. Auction-Based Federated Learning via Truthful Mechanism Design. IEEE Transactions on Mobile Computing, 2025 . [Google Scholar]

- Tang, X.; Yu, H. A Cost-Aware Utility-Maximizing Bidding Strategy for Auction-Based Federated Learning. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems 2025, 36, 12866–12879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Y.; et al. Reinforcement Learning-Based Client Selection for Efficient Federated Learning. In Proceedings of the AAAI, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Q.; et al. Fair Resource Allocation in Federated Learning. In Proceedings of the ICML Workshop on Federated Learning, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Liu, Q.; Liang, H.; Joshi, G.; Poor, H.V. Tackling the Objective Inconsistency Problem in Heterogeneous Federated Optimization. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; Larochelle, H., Ranzato, M., Hadsell, R., Balcan, M., Lin, H., Eds.; Curran Associates, Inc., 2020; Vol. 33, pp. 7611–7623. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, T.; Kong, L.; Stich, S.U.; Jaggi, M. Ensemble Distillation for Robust Model Fusion in Federated Learning. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; Larochelle, H., Ranzato, M., Hadsell, R., Balcan, M., Lin, H., Eds.; Curran Associates, Inc., 2020; Vol. 33, pp. 2351–2363. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Z.; Hong, J.; Zhou, J. Data-Free Knowledge Distillation for Heterogeneous Federated Learning. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 38th International Conference on Machine Learning; Meila, M., Zhang, T., Eds.; PMLR; Proceedings of Machine Learning Research, 18-24 Jul 2021; Vol. 139, pp. 12878–12889. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Li, Y.; Xu, W.; Li, R.; Zhan, Y.; Zeng, Z. DaFKD: Domain-Aware Federated Knowledge Distillation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), June 2023; pp. 20412–20421. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, S.; Liao, T.; Fu, L.; Chen, C.; Bian, J.; Zheng, Z. Data-free knowledge distillation via generator-free data generation for Non-IID federated learning. Neural Networks 2024, 179, 106627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.; Cao, Y.; Li, A.; Li, Z.; Liu, C.; Li, T.; Chen, M.; Liu, Y. FedMut: Generalized Federated Learning via Stochastic Mutation. Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence 2024, 38, 12528–12537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, J.; Xia, Z.; Li, R.; Hu, M.; Chen, M. FedQP: Towards Accurate Federated Learning using Quadratic Programming Guided Mutation. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2411.15847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraboni, Y.; Vidal, R.; Kameni, L.; Lorenzi, M. Clustered Sampling: Low-Variance and Improved Representativity for Clients Selection in Federated Learning. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 38th International Conference on Machine Learning; Meila, M., Zhang, T., Eds.; PMLR; Proceedings of Machine Learning Research, 18-24 Jul 2021; Vol. 139, pp. 3407–3416. [Google Scholar]

- Li, A.; Wang, G.; Hu, M.; Sun, J.; Zhang, L.; Tuan, L.A.; Yu, H. Joint Client-and-Sample Selection for Federated Learning via Bi-Level Optimization. IEEE Transactions on Mobile Computing 2024, 23, 15196–15209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Chen, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Kailkhura, B. FedCluster: Boosting the Convergence of Federated Learning via Cluster-Cycling. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Conference on Big Data (Big Data), 2020; pp. 5017–5026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Z.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Z.; Wang, R.; Meng, X.; Meng, L. Clustering-based Curriculum Construction for Sample-Balanced Federated Learning. In Proceedings of the Artificial Intelligence; Cham, Fang, L., Povey, D., Zhai, G., Mei, T., Wang, R., Eds.; 2022; pp. 155–166. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, M.; Yue, Z.; Xie, X.; Chen, C.; Huang, Y.; Wei, X.; Lian, X.; Liu, Y.; Chen, M. Is Aggregation the Only Choice? Federated Learning via Layer-wise Model Recombination. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 30th ACM SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, New York, NY, USA, 2024; KDD ’24, pp. 1096–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.; Zhou, P.; Yue, Z.; Ling, Z.; Huang, Y.; Li, A.; Liu, Y.; Lian, X.; Chen, M. FedCross: Towards Accurate Federated Learning via Multi-Model Cross-Aggregation. Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 40th International Conference on Data Engineering (ICDE) 2024, 2137–2150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Z.; Hu, M.; Yan, D.; Liu, R.; Li, A.; Xie, X.; Chen, M. MultiSFL: Towards Accurate Split Federated Learning via Multi-Model Aggregation and Knowledge Replay. Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence 2025, 39, 914–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasr, M.; Shokri, R.; Houmansadr, A. Comprehensive Privacy Analysis of Deep Learning: Passive and Active White-box Inference Attacks against Centralized and Federated Learning. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SP), 2019; pp. 739–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; Li, S.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Sharif, K.; Hu, H.; Li, Y. Membership Inference Attacks Against Deep Learning Models via Logits Distribution. IEEE Transactions on Dependable and Secure Computing 2023, 20, 3799–3808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonawitz, K.; Ivanov, V.; Kreuter, B.; Marcedone, A.; McMahan, H.B.; Patel, S.; Ramage, D.; Segal, A.; Seth, K. Practical Secure Aggregation for Privacy-Preserving Machine Learning. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2017 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security, New York, NY, USA, 2017; CCS ’17, pp. 1175–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwork, C.; Roth, A. The Algorithmic Foundations of Differential Privacy. Foundations and Trends® in Theoretical Computer Science 2014, 9, 211–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Yang, J. Towards Making Systems Forget with Machine Unlearning. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy, 2015; pp. 463–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Q.; Li, S.; Raviv, N.; Kalan, S.M.M.; Soltanolkotabi, M.; Avestimehr, S.A. Lagrange Coded Computing: Optimal Design for Resiliency, Security, and Privacy. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Twenty-Second International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Statistics PMLR; Chaudhuri, K., Sugiyama, M., Eds.; Proceedings of Machine Learning Research, 16-18 Apr 2019; Vol. 89, pp. 1215–1225. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.; Hou, S.; Buyukates, B.; Avestimehr, S. Secure Federated Clustering. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2205.15564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Pang, W.; Pedrycz, W. One-Shot Federated Clustering Based on Stable Distance Relationships. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics 2024, 20, 13262–13272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, J.; Lampert, C.H.; Saulpic, D. Differentially Private Federated k-Means Clustering with Server-Side Data. arXiv 2025, arXiv:cs. [Google Scholar]

- MCQUEEN, J. Some methods of classification and analysis of multivariate observations. Proc. of 5th Berkeley Symposium on Math. Stat. and Prob., 1967 ; pp. 281–297. [Google Scholar]

- Ikotun, A.M.; Ezugwu, A.E.; Abualigah, L.; Abuhaija, B.; Heming, J. K-means clustering algorithms: A comprehensive review, variants analysis, and advances in the era of big data. Information Sciences 2023, 622, 178–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, A.; Jordan, M.; Weiss, Y. On Spectral Clustering: Analysis and an algorithm. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; Dietterich, T., Becker, S., Ghahramani, Z., Eds.; MIT Press, 2001; Vol. 14. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, L.; Li, C.; Jin, D.; Ding, S. Survey of spectral clustering based on graph theory. Pattern Recognition 2024, 151, 110366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naeem, A.; Anees, T.; Naqvi, R.A.; Loh, W.K. A comprehensive analysis of recent deep and federated-learning-based methodologies for brain tumor diagnosis. Journal of Personalized Medicine 2022, 12, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, J.; Timothy, T.Y.; Ma, D.; Zang, P.; Owen, J.P.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, R.K.; Beg, M.F.; Lee, A.Y.; Jia, Y.; et al. Federated learning for microvasculature segmentation and diabetic retinopathy classification of OCT data. Ophthalmology Science 2021, 1, 100069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, S.; Landman, B.A.; Huo, Y.; Gokhale, A. Communication-efficient federated learning for multi-institutional medical image classification. Proceedings of the Medical Imaging 2022: Imaging Informatics for Healthcare, Research, and Applications. SPIE 2022, Vol. 12037, 6–12. [Google Scholar]

- Antunes, R.S.; André da Costa, C.; Küderle, A.; Yari, I.A.; Eskofier, B. Federated Learning for Healthcare: Systematic Review and Architecture Proposal 2022. 13. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Yu, H.; Liu, Y.; Bao, R.; Jiang, J.; Nie, Z.; Xu, Q.; Yang, Q. Contribution-Aware Federated Learning for Smart Healthcare. Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence 2022, 36, 12396–12404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Zhang, J.; Hao, W.; Spell, G.P.; Carin, L. Flop: Federated learning on medical datasets using partial networks. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 27th ACM SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining, 2021; pp. 3845–3853. [Google Scholar]

- Ogier du Terrail, J.; Ayed, S.S.; Cyffers, E.; Grimberg, F.; He, C.; Loeb, R.; Mangold, P.; Marchand, T.; Marfoq, O.; Mushtaq, E.; et al. Flamby: Datasets and benchmarks for cross-silo federated learning in realistic healthcare settings. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2022, 35, 5315–5334. [Google Scholar]

- Sarma, K.V.; Harmon, S.; Sanford, T.; Roth, H.R.; Xu, Z.; Tetreault, J.; Xu, D.; Flores, M.G.; Raman, A.G.; Kulkarni, R.; et al. Federated learning improves site performance in multicenter deep learning without data sharing. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association 2021, 28, 1259–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Khan, A.A.; Kumar, J.; Golilarz, N.A.; Zhang, S.; Ting, Y.; Zheng, C.; Wang, W.; et al. Blockchain-federated-learning and deep learning models for covid-19 detection using ct imaging. IEEE Sensors Journal 2021, 21, 16301–16314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, B.; Wang, J.; Cheng, J.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Liu, L.; Zhao, H.; Wang, C.; Liu, B. Experiments of federated learning for COVID-19 chest X-ray images. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Security, 2021; Springer; pp. 41–53. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, D.; Xu, Z.; Li, W.; Myronenko, A.; Roth, H.R.; Harmon, S.; Xu, S.; Turkbey, B.; Turkbey, E.; Wang, X.; et al. Federated semi-supervised learning for COVID region segmentation in chest CT using multi-national data from China, Italy, Japan. Medical image analysis 2021, 70, 101992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qayyum, A.; Ahmad, K.; Ahsan, M.A.; Al-Fuqaha, A.; Qadir, J. Collaborative federated learning for healthcare: Multi-modal covid-19 diagnosis at the edge. IEEE Open Journal of the Computer Society 2022, 3, 172–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul Salam, M.; Taha, S.; Ramadan, M. COVID-19 detection using federated machine learning. PloS one 2021, 16, e0252573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, R.; Boland, M.R.; Liu, Z.; Liu, Y.; Chang, H.H.; Xu, H.; Chu, H.; Schmid, C.H.; Forrest, C.B.; Holmes, J.H.; et al. Learning from electronic health records across multiple sites: A communication-efficient and privacy-preserving distributed algorithm. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association 2020, 27, 376–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, L.; Shea, A.L.; Qian, H.; Masurkar, A.; Deng, H.; Liu, D. Patient clustering improves efficiency of federated machine learning to predict mortality and hospital stay time using distributed electronic medical records. Journal of biomedical informatics 2019, 99, 103291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Roberts, K.; Jiang, X.; Long, Q. Distributed learning from multiple EHR databases: contextual embedding models for medical events. Journal of biomedical informatics 2019, 92, 103138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaid, A.; Jaladanki, S.K.; Xu, J.; Teng, S.; Kumar, A.; Lee, S.; Somani, S.; Paranjpe, I.; De Freitas, J.K.; Wanyan, T.; et al. Federated learning of electronic health records to improve mortality prediction in hospitalized patients with COVID-19: machine learning approach. JMIR medical informatics 2021, 9, e24207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brisimi, T.S.; Chen, R.; Mela, T.; Olshevsky, A.; Paschalidis, I.C.; Shi, W. Federated learning of predictive models from federated electronic health records. International journal of medical informatics 2018, 112, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, C.; Hu, M.; Chen, Z.; Yang, Y.; Xie, X.; Liu, Y.; Chen, M. AdaptiveFL: Adaptive heterogeneous federated learning for resource-constrained AIoT systems. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 61st ACM/IEEE Design Automation Conference, 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, Z.; Hu, M.; Yan, D.; Xie, X.; Li, T.; Li, A.; Zhou, J.; Chen, M. CaBaFL: Asynchronous Federated Learning via Hierarchical Cache and Feature Balance. IEEE Transactions on Computer-Aided Design of Integrated Circuits and Systems 2024, 43, 4057–4068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Jia, C.; Hu, M.; Xie, X.; Li, A.; Chen, M. FlexFL: Heterogeneous Federated Learning via APoZ-Guided Flexible Pruning in Uncertain Scenarios. IEEE Transactions on Computer-Aided Design of Integrated Circuits and Systems 2024, 43, 4069–4080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, C.; Wei, S.; Dai, S.; Garg, S.; Kaddoum, G.; Shamim Hossain, M. Federated Self-Supervised Learning Based on Prototypes Clustering Contrastive Learning for Internet of Vehicles Applications. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2025, 12, 4692–4700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, D.; Yang, Y.; Hu, M.; Fu, X.; Chen, M. MMDFL: Multi-Model-based Decentralized Federated Learning for Resource-Constrained AIoT Systems. In Proceedings of the 2025 62nd ACM/IEEE Design Automation Conference (DAC), 2025; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moulik, S.; Misra, S.; Gaurav, A. Cost-effective mapping between wireless body area networks and cloud service providers based on multi-stage bargaining. IEEE Transactions on Mobile Computing 2016, 16, 1573–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Cao, K.; Cao, G.; Qiu, M.; Wei, T. Client scheduling and resource management for efficient training in heterogeneous IoT-edge federated learning. IEEE Transactions on Computer-Aided Design of Integrated Circuits and Systems 2021, 41, 2407–2420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Xu, R.; Zhang, H.; Yang, Z.; Liu, H. EV-FL: Efficient verifiable federated learning with weighted aggregation for industrial IoT networks. IEEE/ACM Transactions on Networking 2023, 32, 1723–1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Z.; Zhou, T.; Yan, Z.; Hu, J.; Shi, Y. Personalized meta-federated learning for IoT-enabled health monitoring. IEEE Transactions on Computer-Aided Design of Integrated Circuits and Systems 2024, 43, 3157–3170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Li, S.; Li, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, C.; Zheng, Z. A Personalized Federated Tensor Factorization Framework for Distributed IoT Services QoS Prediction From Heterogeneous Data. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2022, 9, 25460–25473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, B.; Liu, B.; Zheng, V.; Yang, Q. A Federated Recommender System for Online Services. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 14th ACM Conference on Recommender Systems, New York, NY, USA, 2020; RecSys ’20, pp. 579–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, K.; Wang, Q.; O’Reilly-Morgan, D.; Tragos, E.; Smyth, B.; Hurley, N.; Geraci, J.; Lawlor, A. FedFast: Going Beyond Average for Faster Training of Federated Recommender Systems. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 26th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining, New York, NY, USA, 2020; KDD ’20, pp. 1234–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Shan, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wang, H.; Wang, W.; Wang, Y.; Li, R. Personalized Federated Recommendation for Cold-Start Users via Adaptive Knowledge Fusion. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the ACM on Web Conference 2025, New York, NY, USA, 2025; WWW ’25, pp. 2700–2709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Yang, Z.; Saad, W.; Yin, C.; Poor, H.V.; Cui, S. A Joint Learning and Communications Framework for Federated Learning Over Wireless Networks. IEEE Transactions on Wireless Communications 2021, 20, 269–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beutel, D.; Topal, T.; Mathur, A.; Qiu, X.; Parcollet, T.; Lane, N.D. Flower: A Friendly Federated Learning Research Framework. arXiv arXiv:2007.14390. [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; et al. OpenFed: A Comprehensive and Versatile Open-Source Federated Learning Framework. In Proceedings of the CVPR Workshops (FedVision), 2023. [Google Scholar]

- He, C.; et al. Benchmarking Federated Learning Algorithms under System and Statistical Heterogeneity. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems, 2023 . [Google Scholar]

- Kairouz, P.; McMahan, H.B.; Avent, B.; et al. Advances and Open Problems in Federated Learning. Foundations and Trends® in Machine Learning 2021, 14, 1–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abadi, M.; Chu, A.; Goodfellow, I.; et al. Deep Learning with Differential Privacy. In Proceedings of the 2016 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- He, C.; Annavaram, M.; Avestimehr, S. FedML: A Research Library and Benchmark for Federated Machine Learning. arXiv arXiv:2007.13518. [CrossRef]

- He, C.; Avestimehr, S. Towards Scalable and Robust Federated Learning Systems. IEEE Transactions on Parallel and Distributed Systems, 2021 . [Google Scholar]

- Ryffel, T.; Trask, A.; Dahl, M.; Wagner, B.; Mancuso, J.; Rueckert, D. A Generic Framework for Privacy Preserving Deep Learning. arXiv arXiv:1811.04017. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Liu, Y.; Chen, T.; Tong, Y. Federated Machine Learning: Concept and Applications. ACM Transactions on Intelligent Systems and Technology, 2019 . [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Chen, T.; Yang, Q. Secure Federated Learning for Vertical Partitioned Data. IEEE Intelligent Systems 2020, 35, 90–97. [Google Scholar]

- Ning, W.; Zhu, Y.; Song, C.; Li, H.; Zhu, L.; Xie, J.; Chen, T.; Xu, T.; Xu, X.; Gao, J. Blockchain-Based Federated Learning: A Survey and New Perspectives. Applied Sciences 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larasati, H.T.; Firdaus, M.; Kim, H. Quantum federated learning: Remarks and challenges. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 9th International Conference on Cyber Security and Cloud Computing (CSCloud)/2022 IEEE 8th International Conference on Edge Computing and Scalable Cloud (EdgeCom), 2022; IEEE; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Innan, N.; Marchisio, A.; Bennai, M.; Shafique, M. Qfnn-ffd: Quantum federated neural network for financial fraud detection. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE International Conference on Quantum Software (QSW). IEEE, 2025; pp. 41–47. [Google Scholar]

- Chu, C.; Jiang, L.; Chen, F. Cryptoqfl: quantum federated learning on encrypted data. Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Quantum Computing and Engineering (QCE). IEEE 2023, Vol. 1, 1231–1237. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, C.; Fan, L.; Zeng, B.; Yang, Q. Federated learning with quantum secure aggregation. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2207.07444. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, C.; Yan, R.; Zhu, H.; Yu, H.; Xu, M.; Shen, Y.; Xu, Y.; Xiao, M.; Dong, Z.Y.; Skoglund, M.; et al. Toward Quantum Federated Learning. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems, 2025 . [Google Scholar]

- Yao, Y.; Zhang, J.; Wu, J.; Huang, C.; Xia, Y.; Yu, T.; Zhang, R.; Kim, S.; Rossi, R.; Li, A.; et al. Federated Large Language Models: Current Progress and Future Directions. arXiv 2025, arXiv:cs. [Google Scholar]

- Abouelmagd, A.A.; Hilal, A. Emerging Paradigms for Securing Federated Learning Systems. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2509.21147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Sahu, A.K.; Talwalkar, A.; Smith, V. Federated Learning: Challenges, Methods, and Future Directions. IEEE Signal Processing Magazine 2020, 37, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Survey | Year | Scope / Domain | Main Focus / Taxonomy | Difference from Our Survey |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yang et al. [84] | 2019 | General FL; data distribution types | Divides FL into three categories according to data distribution characteristics. | Overview of FL but lacks detailed classification and summary of existing methods. |

| Li et al. [85] | 2020 | General FL; efficiency, heterogeneity, privacy | Challenges of FL from efficiency, heterogeneity, and privacy perspectives; several future research directions. | Our survey provides a more comprehensive and integrated challenge-centric taxonomy, including finer-grained treatment of heterogeneity. |

| Lim et al. [100] | 2020 | Mobile edge networks | Survey of FL in mobile edge networks and edge-computing scenarios. | Scenario-specific; our survey is cross-domain and challenge-centric. |

| Niknam et al. [128] | 2020 | Wireless communication networks | Applications and challenges of FL in wireless communication environments. | Domain-centric; our survey is broader and integrates multiple challenges across the FL pipeline. |

| Kulkarni et al. [129] | 2020 | Statistical heterogeneity; personalization | Shows how statistical heterogeneity can hinder FL and highlights the need for personalized FL. | Heterogeneity-focused; our survey treats heterogeneity as one of multiple coupled core challenges. |

| Wu et al. [124] | 2020 | Personalized FL; cloud–edge IoT | Personalized FL framework in a cloud–edge architecture for intelligent IoT applications. | Personalization-centric; our survey covers broader FL schemes and cross-challenge interactions. |

| Aledhari et al. [94] | 2020 | Enabling technologies, protocols, applications | Reviews FL-enabling platforms, protocols, use-cases, and key challenges. | Enabling-tech focus; our survey provides a broader pipeline-wide challenge-centric taxonomy. |

| Li et al. [107] | 2020 | FL applications | Reviews major FL applications in industrial engineering and computer science, outlining key research fronts. | Application-focused; our survey emphasizes challenge-centric analysis beyond application categorization. |

| Nguyen et al. [99] | 2021 | IoT, smart services | FL applications in IoT (smart healthcare, transport, UAVs, smart cities); FL-enabled IoT services (caching, offloading, attack detection). | IoT-only; our survey analyzes cross-domain and cross-challenge interactions across the FL pipeline. |

| Yin et al. [130] | 2021 | Privacy-preserving FL | 5W taxonomy; privacy leakage risks; privacy-preservation mechanisms. | Privacy-focused; our survey situates privacy within a broader set of interconnected challenges. |

| Li et al. [87] | 2021 | FL systems | Categorization by data distribution, privacy mechanism, communication architecture, federation scale. | Systems-centric; our survey provides a unified challenge-centric view spanning systems + algorithms + applications. |

| Kairouz et al. [86] | 2021 | General FL; foundations and open problems | Recent advances in FL: comprehensive survey of open problems and challenges. | Broad overview; lacks fine-grained method classification under a unified challenge framework. |

| Wahab et al. [101] | 2021 | General FL; challenges and approaches | Fine-grained classification scheme of existing FL challenges and approaches. | Different organizing principle; our survey emphasizes six tightly coupled core challenges and their interdependencies. |

| Khan et al. [131] | 2021 | IoT applications | Advances in FL for IoT applications and a taxonomy using various parameters (e.g., robustness, privacy, communication cost). | IoT-centric; our survey is cross-domain and pipeline-wide challenge-centric. |

| Zhu et al. [126] | 2021 | FL + NAS | Surveys FL, NAS methods, and emerging federated NAS approaches with a taxonomy of online/offline and single/multi-objective variants. | Focuses on FL–NAS intersection; our survey provides broader FL challenge coverage beyond architecture search. |

| Blanco-Justicia et al. [113] | 2021 | Security & privacy in FL | Surveys privacy and security attacks in FL and mitigation strategies, highlighting challenges in achieving both simultaneously. | Security/privacy-focused; our survey integrates these aspects within a broader, multi-challenge FL taxonomy. |

| Lo et al. [95] | 2021 | FL from a software engineering perspective | Systematic review of FL system development lifecycle: requirements, architecture, implementation, and evaluation. | SE-focused lifecycle view; our survey provides a broader, challenge-centric taxonomy across the full FL pipeline. |

| Liu et al. [88] | 2022 | General FL systems | From distributed ML to FL; system architecture; parallelism; aggregation; communication; security; taxonomy of FL systems. | System-architecture oriented; our survey is challenge-centric and integrates computation, communication, heterogeneity, privacy, and optimization. |

| Gao et al. [132] | 2022 | Heterogeneous FL (data, system, model) | Investigates heterogeneous FL in terms of data-space, statistical, system, and model heterogeneity. | This work classifies existing methods based on problem settings and learning objectives, while our survey classifies methods based on specific techniques. |

| Tan et al. [125] | 2022 | Personalized FL; taxonomy | Explores the field of personalized FL and conducts a taxonomic survey of existing methods. | This work briefly explains statistical heterogeneity, but lacks a comprehensive taxonomy and analysis of the challenges in FL. |

| Pouriyeh et al. [97] | 2022 | Communication efficiency in FL | Reviews communication constraints, efficiency challenges, and secure communication strategies in FL. | Communication-focused; our survey integrates communication with other key FL challenges in a unified framework. |

| Mahlool et al. [98] | 2022 | General FL: concepts and applications | Covers FL components, challenges, and applications with emphasis on medical use-cases. | Application-oriented; our survey offers a broader, structured challenge-centric taxonomy beyond specific domains. |

| Zhang et al. [114] | 2022 | Security & privacy threats in FL | Classifies FL attacks by adversary type, reviews major threat models and mitigation techniques, including DGL, GAN-based attacks, and TEE/blockchain defenses. | Threat-focused; our survey integrates security/privacy with broader FL challenges across the entire pipeline. |

| Bharati et al. [108] | 2022 | General FL; applications & challenges | Reviews FL frameworks, architectures, applications (especially healthcare), and key privacy/security/heterogeneity challenges. | Application-heavy; our survey provides a broader, structured challenge-centric classification beyond domain-specific analyses. |

| Abreha et al. [103] | 2022 | FL in edge computing | Systematic survey of FL implementation in edge environments, covering architectures, protocols, hardware, applications, and challenges. | Edge-computing–focused; our survey provides a broader, cross-environment challenge-centric taxonomy. |

| Gupta et al. [96] | 2022 | FL in distributed environments | Reviews centralized, decentralized, and heterogeneous FL frameworks, focusing on privacy, DP techniques, and distributed optimization. | Distributed-environment focus; our survey provides a broader, unified challenge-centric taxonomy across all FL settings. |

| Wen et al. [90] | 2023 | General FL; challenges and applications | Surveys FL basics, privacy/security mechanisms, communication issues, heterogeneity, and practical applications. | Covers core challenges and applications broadly; our survey offers a more structured, challenge-centric taxonomy across all FL dimensions. |

| Moshawrab et al. [110] | 2023 | Aggregation algorithms in FL | Reviews FL aggregation strategies and algorithms, their implementations, limitations, and future directions. | Aggregation-focused; our survey covers aggregation as one component within a broader, multi-challenge FL taxonomy. |

| Beltrán et al. [111] | 2023 | Decentralized FL (DFL) | Examines DFL fundamentals, architectures, communication mechanisms, frameworks, and application scenarios. | DFL-specific focus; our survey provides a broader, unified view across both centralized and decentralized FL challenges. |

| Ye et al. [123] | 2023 | Heterogeneous FL (HFL) | Surveys challenges and solutions in statistical, model, communication, and device heterogeneity, with a taxonomy of HFL methods. | Focused solely on heterogeneity, our survey treats heterogeneity as one challenge within a broader, integrated FL taxonomy. |

| Neto et al. [118] | 2023 | Secure FL; attacks and defenses | Systematic review of FL security vulnerabilities, attack types, mitigation strategies, and secure FL applications. | Security-focused, our survey integrates security alongside other core FL challenges in a unified framework. |

| Almanifi et al. [112] | 2023 | Communication + computation efficiency in FL | Surveys communication- and computation-efficiency techniques, challenges, and optimization strategies in FL. | Efficiency-focused, our survey integrates efficiency with broader FL challenges across the full pipeline. |

| Gupta et al. [117] | 2023 | Game-theoretic FL | Reviews game-theory–based FL models for incentives, authentication, privacy, trust, and threat detection, with bibliometric analysis. | GT-focused; our survey provides a broader, multi-challenge perspective beyond incentive mechanisms. |

| Moshawrab et al. [109] | 2023 | FL for disease prediction | Reviews FL concepts, aggregation approaches, and medical applications, highlighting limitations and future directions. | Healthcare-focused, our survey provides a broader, cross-domain challenge-centric taxonomy beyond specific medical applications. |

| Asad et al. [133] | 2023 | Communication-efficient FL | Surveys communication-reduction techniques, including compression, structured updates, resource management, and client selection. | Communication-specific; our survey integrates communication with broader FL challenges in a unified taxonomy. |

| Che et al. [127] | 2023 | Multimodal FL | Surveys multimodal FL methods, categorizing congruent vs. incongruent MFL, with benchmarks, applications, and future directions. | Modality-focused, our survey provides a broader challenge-centric taxonomy beyond multimodal considerations. |

| Sirohi et al. [104] | 2023 | FL for 6G secure communication systems | Analyzes vulnerabilities, threats, and defenses in FL across 6G application domains. | Domain-specific security focus; our survey provides a broader, unified challenge-centric taxonomy across all FL settings. |

| Qammar et al. [119] | 2023 | Blockchain-based FL | Systematic review of integrating blockchain with FL to enhance security, privacy, accountability, and robustness. | Blockchain-specific focus; our survey provides a broader, multi-challenge FL taxonomy beyond decentralized ledger integration. |

| Zhu et al. [120] | 2023 | Blockchain-empowered FL | Surveys how blockchain addresses coordination, trust, incentives, and security issues in FL, with a taxonomy of BlockFed system models. | Blockchain-focused; our survey provides a broader challenge-centric analysis beyond ledger-integrated FL architectures. |

| Liu et al. [89] | 2024 | General FL; recent advances | Systematic review of recent FL methods, applications, taxonomy, and frameworks. | Broad recent-advances survey; our work provides a more integrated, challenge-centric analysis. |

| Yurdem et al. [91] | 2024 | General FL; overview and strategies | Comprehensive overview of FL principles, strategies, applications, tools, and future directions. | Broad introductory overview; our survey provides deeper, challenge-focused analysis across the full FL pipeline. |