Submitted:

30 October 2024

Posted:

30 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- We present an innovative method for enhancing client model performance through data-free knowledge distillation.

- We modified GAN training procedure to generate pseudo data, effectively facilitating knowledge transfer between clients to tackle Non-IID challenges.

- We utilize dual decomposition optimization technique to protect clients’ private data against DRA.

- FedSGAN simultaneously enhances client model performance and preserves privacy.

2. Preliminaries

2.1. Dual Decomposition Optimization

- Clients randomly initialize .

- Clients initialise with zero value and with value and send them to the server.

- Client Calculates the loss value :

- Clients fine-tune its gradient of loss value as below:

- Clients update its weight with learning rate as below:

- Repeat steps 3 to 7 till the end of the training phase.

| Algorithm 1 Calculating the . |

|

Inputs: The client local model parameters , m is the size of , N is the total number of clients.

Output: Vector with size of

Case 1:

Case 2:

Case 3:

|

2.1.1. Assumption.1

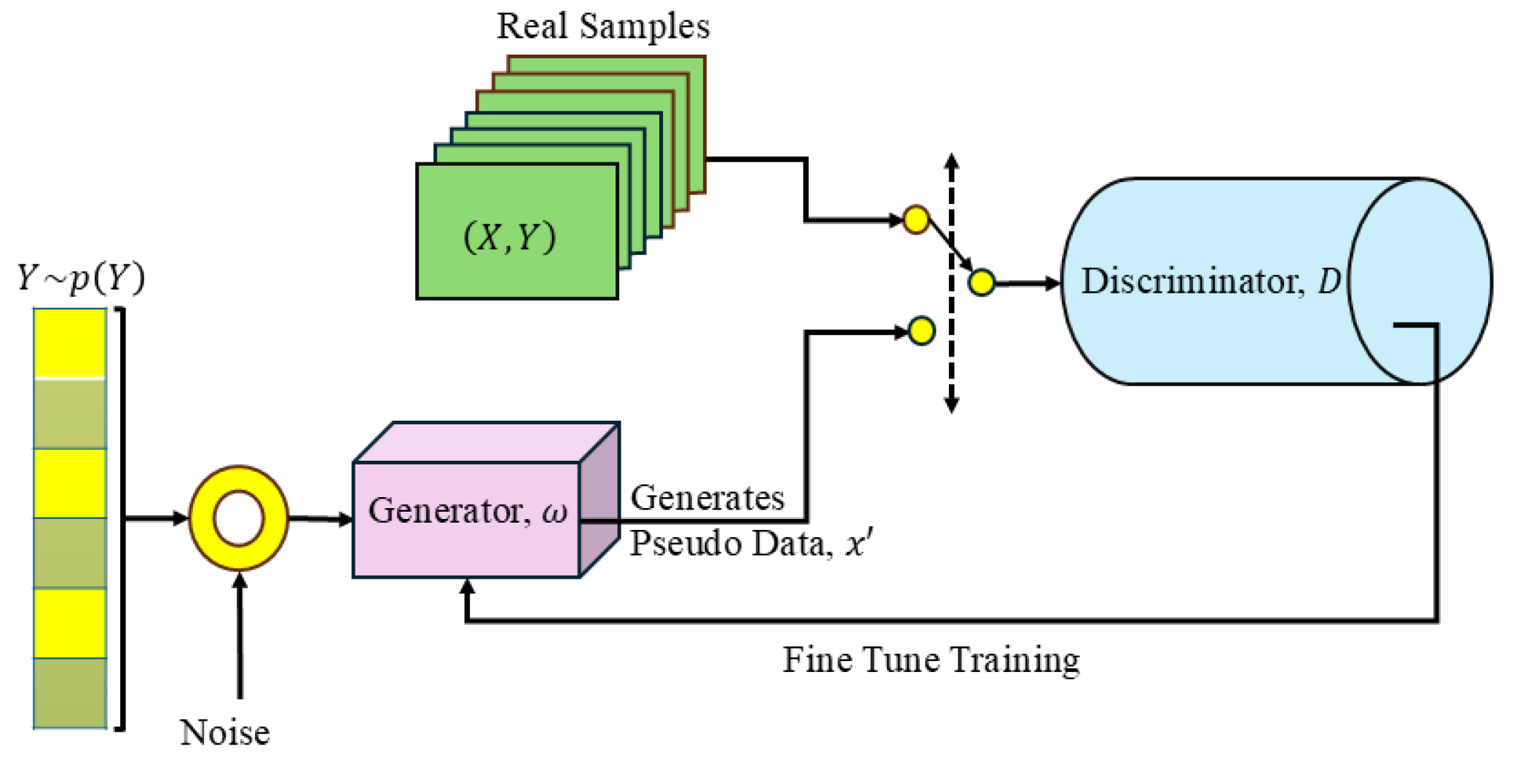

2.2. GAN

3. Methodology

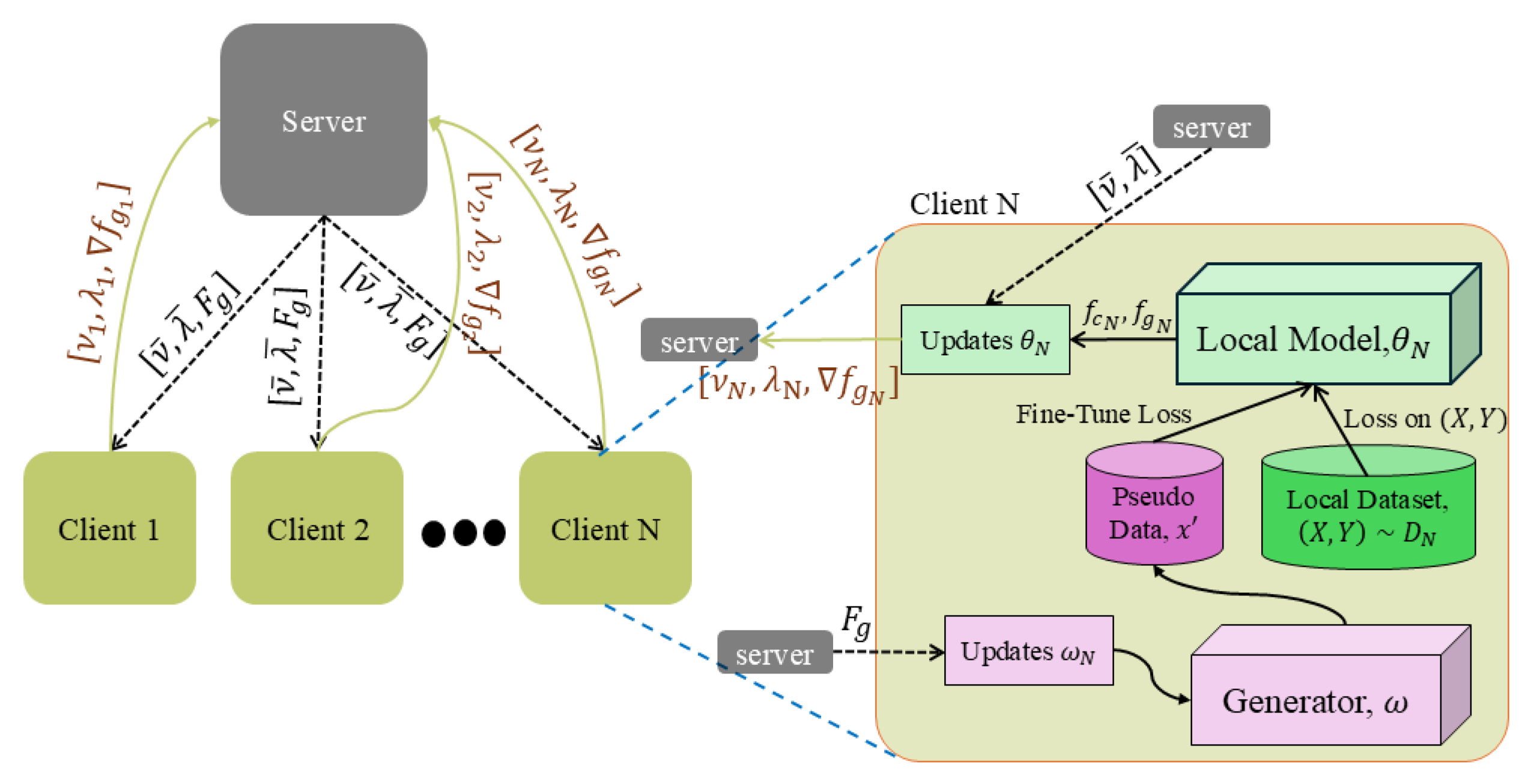

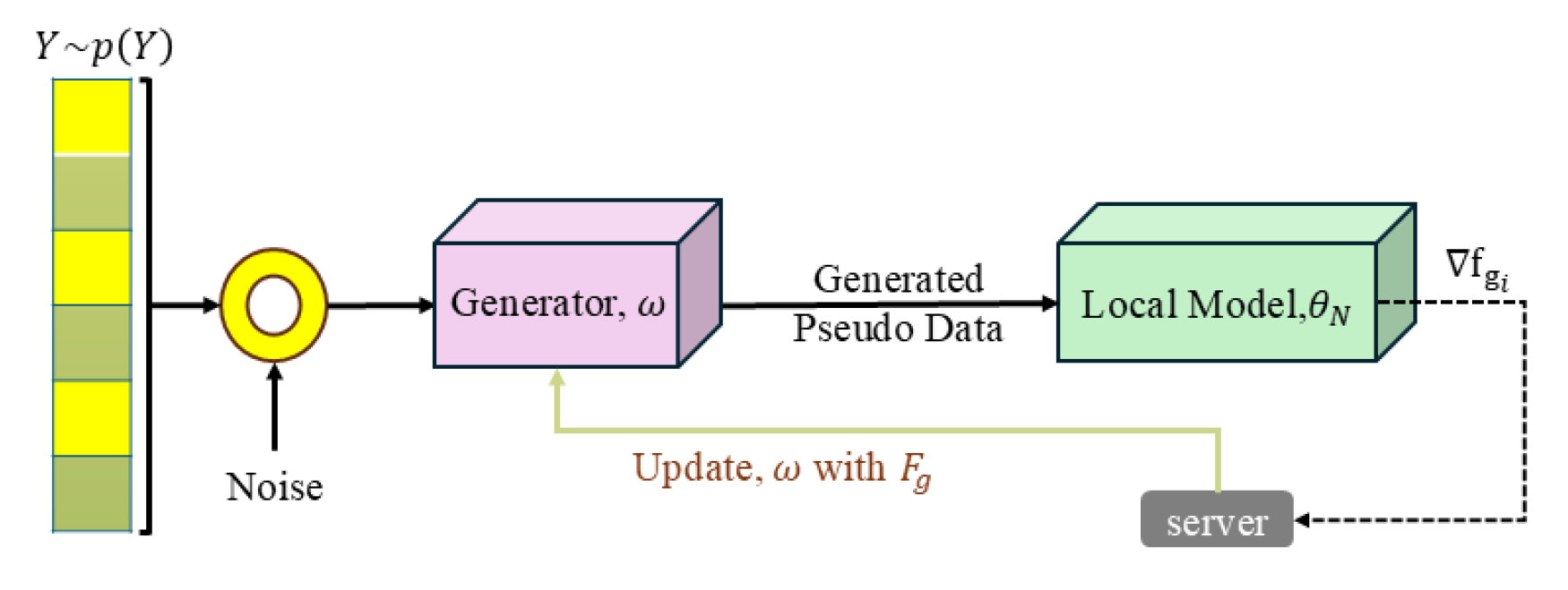

3.1. Client Side

| Algorithm 2 FedSGAN, Client side. |

|

Inputs: Average Lagrange multiplier vector: , Average Lagrange dual vector: ,Average gradient loss function of generator model: , Local model learning rate: , Generator model learning rate: , .

repeat

for all client i∈N in parallel do

Client receive , and from server.

from Equation (16).

).

from Equation (13).

from Equation (15).

from Equation (15).

from Equation (9)

from Equation (10).

from Equation (11).

client sends and to the server.

end for

until training stop

|

3.1.1. Remark.1

3.2. Server Side

| Algorithm 3 FedSGAN, Server side. |

|

Inputs: clients average Lagrange multiplier vector: , clients average Lagrange dual vector: and clients average gradient loss function of generator model:, Number of communication round: T.

for t=1,...,T do

Collect and from clients.

from Equation (4)

from Equation (5)

from Equation (17)

sends and to the clients.

end for

|

4. Experiments

4.1. Implementation Details

4.1.1. Reference Methods

4.1.2. FedSGAN Networks Architecture

4.1.3. Datasets

4.1.4. Differential Privacy

4.1.5. Hyperparameters

4.2. Performance Comparison

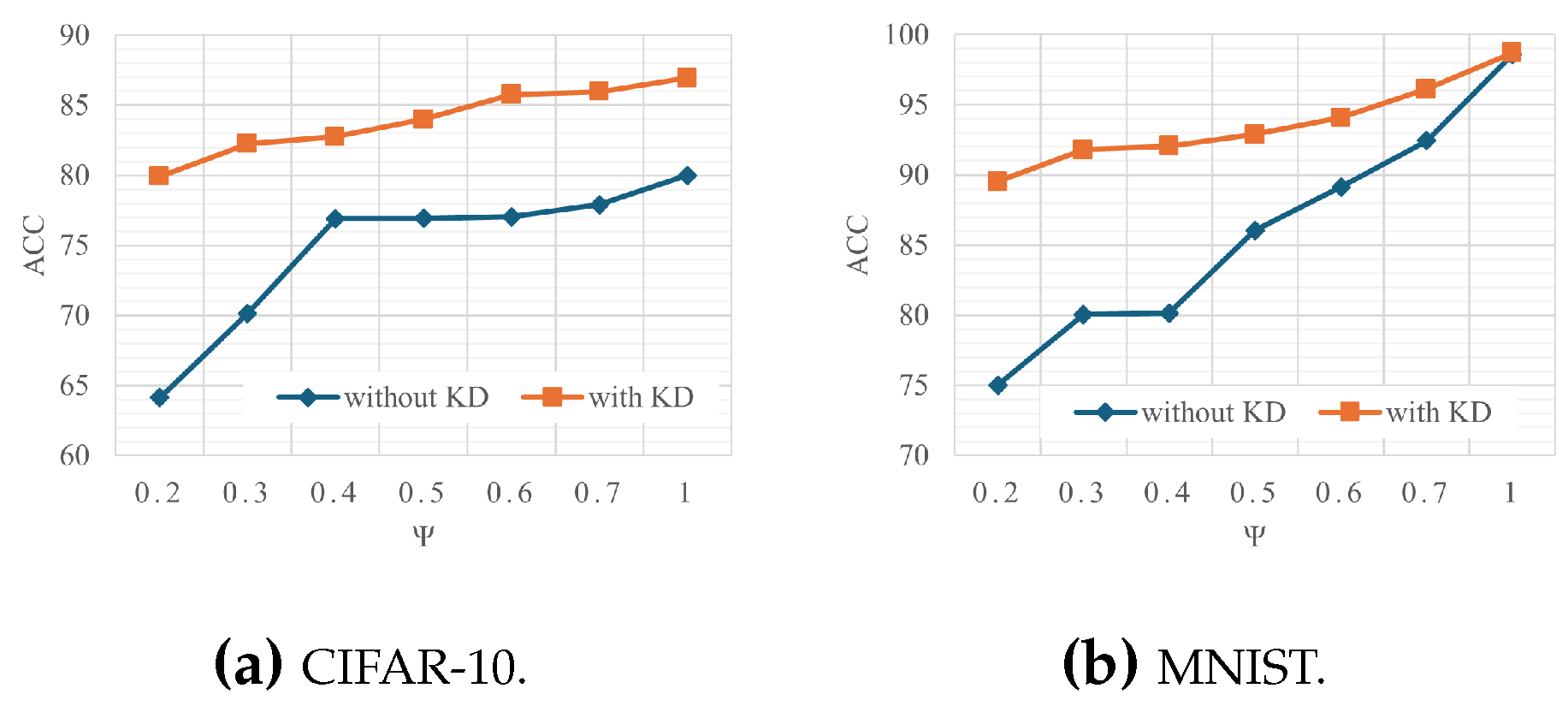

4.2.1. Comparison of FedSGAN Model Without Utilizing KD Method

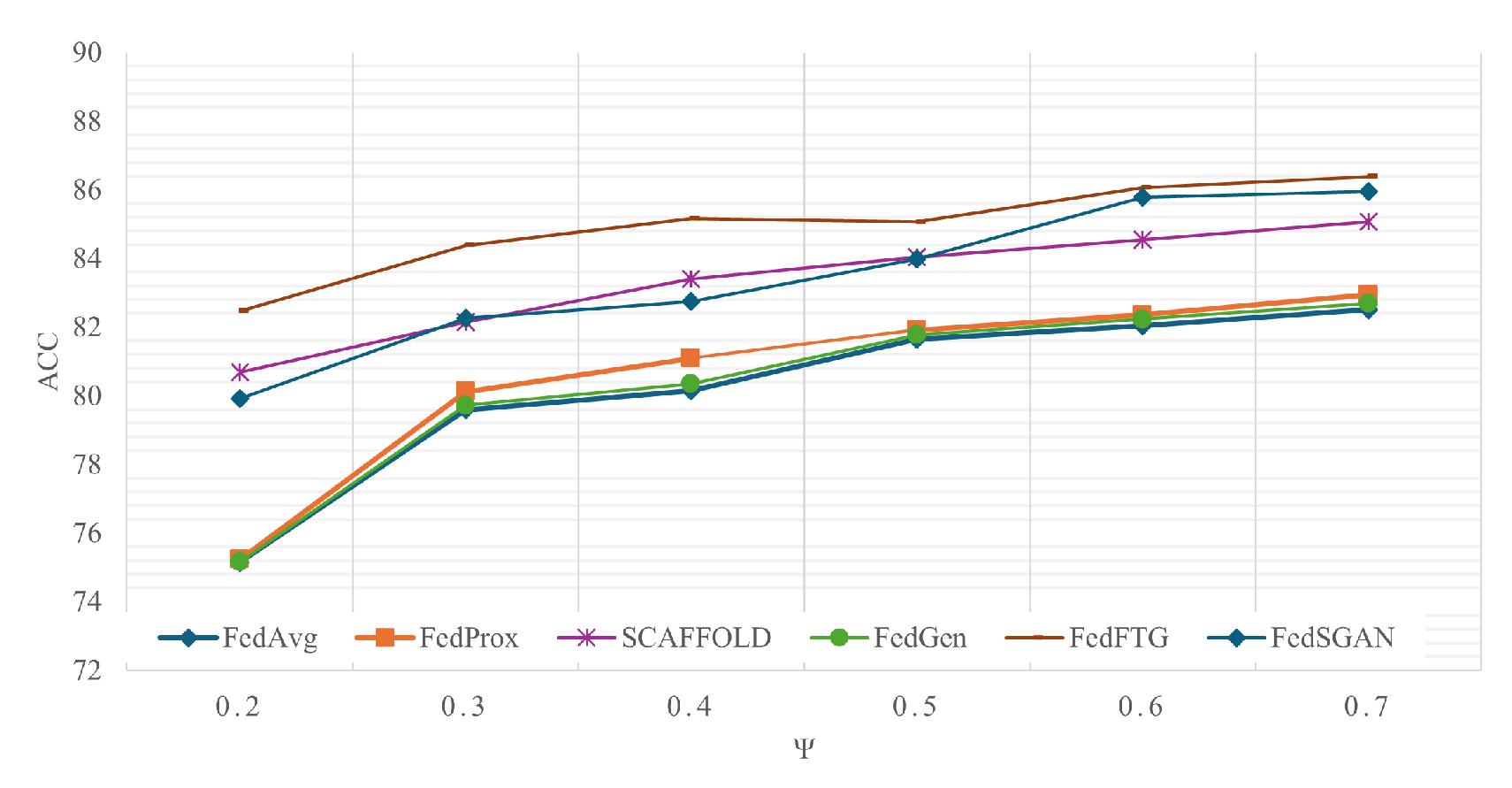

4.2.2. I.Performance Without Privacy Consideration

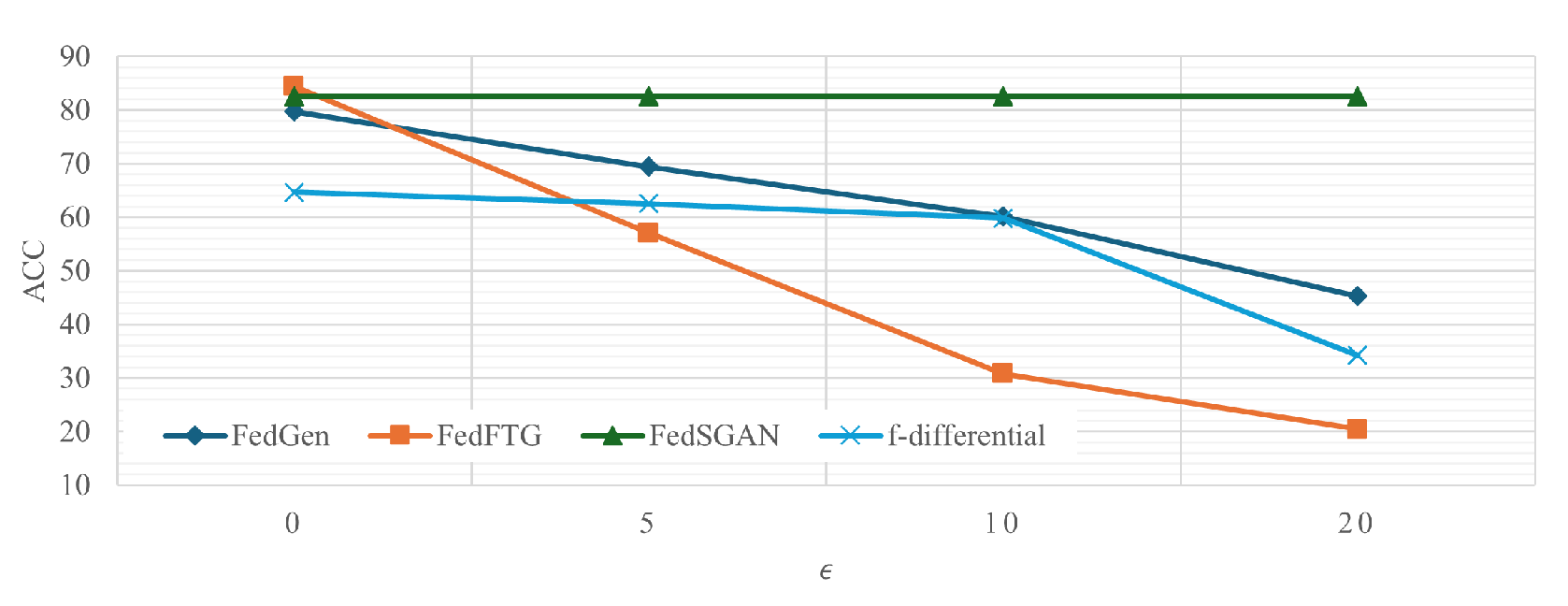

4.2.3. II.Performance with Privacy Consideration

4.2.4. III.Performance with Privacy Consideration and Non-IID Clients

5. Discussion

6. Conclusion

Appendix A. Appendix

Appendix A.1. Optimization Problem Formulation

Appendix A.2. Lagrangian Formulation

Appendix A.3. Gradient Descent Update

Appendix A.3.1. Theorem.1

Appendix A.3.2. Proof:

References

- Nguyen, D.C.; Ding, M.; Pathirana. 6G Internet of Things: A comprehensive survey. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2021, 9, 359–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodfellow, I.; Bengio, Y.; Courville, A. Deep learning; MIT press, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, R.; Shukla, A.; Tanwar, S. BATS: A blockchain and AI-empowered drone-assisted telesurgery system towards 6G. IEEE Transactions on Network Science and Engineering 2020, 8, 2958–2967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.C.; Deng, D.J.; Chih, Y.L.; Chiu, H.T. Smart manufacturing scheduling with edge computing using multiclass deep Q network. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics 2019, 15, 4276–4284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.K.; Jeong, Y.S.; Park, J.H. A deep learning-based IoT-oriented infrastructure for secure smart city. Sustainable Cities and Society 2020, 60, 102252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vimalajeewa, D.; Kulatunga. A service-based joint model used for distributed learning: Application for smart agriculture. IEEE Transactions on Emerging Topics in Computing 2021, 10, 838–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMahan, B. ; Moore. Communication-efficient learning of deep networks from decentralized data. Artificial intelligence and statistics. PMLR, 2017, pp. 1273–1282.

- Cover, T.M. Elements of information theory; John Wiley & Sons, 1999.

- Carlini, N.; Chien, S. ; Nasr. Membership inference attacks from first principles. 2022 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SP). IEEE, 2022, pp. 1897–1914.

- Choquette-Choo, C.A. Label-only membership inference attacks. International conference on machine learning. PMLR, 2021, pp. 1964–1974.

- Long, Y. ; Wang. A pragmatic approach to membership inferences on machine learning models. 2020 IEEE European Symposium on Security and Privacy (EuroS&P). IEEE, 2020, pp. 521–534.

- Carlini, N. ; Tramer. Extracting training data from large language models. 30th USENIX Security Symposium (USENIX Security 21), 2021, pp. 2633–2650.

- Chen, J.; Zhao, Y.; Li, Q.; Feng, X.; Xu, K. FedDef: defense against gradient leakage in federated learning-based network intrusion detection systems. IEEE Transactions on Information Forensics and Security 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haim, N.; Vardi, G.; Yehudai, G.; Shamir, O.; Irani, M. Reconstructing training data from trained neural networks. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2022, 35, 22911–22924. [Google Scholar]

- Hitaj, B.; Ateniese, G.; Perez-Cruz, F. Deep models under the GAN: information leakage from collaborative deep learning. Proceedings of the 2017 ACM SIGSAC conference on computer and communications security, 2017, pp. 603–618.

- Zhu, L.; Liu, Z.; Han, S. Deep leakage from gradients. Advances in neural information processing systems 2019, 32. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Y.; Zhang, L.; Wang, L.; Choo, K.K.R.; Zhang, R. Privacy-preserving and reliable decentralized federated learning. IEEE Transactions on Services Computing 2023, 16, 2879–2891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Shi, M.; Li, P.; Li, R.; Xiong, N.N. An adaptive federated learning scheme with differential privacy preserving. Future Generation Computer Systems 2022, 127, 362–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, A.; Dhakal, S. ; Akdeniz. Differentially private coded federated linear regression. 2021 IEEE Data Science and Learning Workshop (DSLW). IEEE, 2021, pp. 1–6.

- Wei, K.; Li, J.; Ding. Federated learning with differential privacy: Algorithms and performance analysis. IEEE transactions on information forensics and security 2020, 15, 3454–3469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMahan, B. ; Moore. Communication-Efficient Learning of Deep Networks from Decentralized Data. Proceedings of the 20th International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Statistics; Singh, A.; Zhu, J., Eds. PMLR, 2017, Vol. 54, Proceedings of Machine Learning Research, pp. 1273–1282.

- Hsu, T.M.H.; Qi, H.; Brown, M. Measuring the Effects of Non-Identical Data Distribution for Federated Visual Classification, 2019. arXiv:cs.LG/1909.06335].

- Khaled, A.; Mishchenko, K.; Richtarik, P. Tighter Theory for Local SGD on Identical and Heterogeneous Data. Proceedings of the Twenty Third International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Statistics; Chiappa, S.; Calandra, R., Eds. PMLR, 2020, Vol. 108, Proceedings of Machine Learning Research, pp. 4519–4529.

- Hinton, G.; Vinyals, O.; Dean, J. Distilling the Knowledge in a Neural Network, 2015. arXiv:stat.ML/1503.02531].

- Lin, T.; Kong, L.; Stich, S.U.; Jaggi, M. Ensemble Distillation for Robust Model Fusion in Federated Learning. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; Larochelle, H.; Ranzato, M.; Hadsell, R.; Balcan, M.; Lin, H., Eds. Curran Associates, Inc., 2020, Vol. 33, pp. 2351–2363.

- Sattler, F.; Korjakow, T.; Rischke, R.; Samek, W. FedAUX: Leveraging Unlabeled Auxiliary Data in Federated Learning. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems 2023, 34, 5531–5543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.Y.; Chao, W.L. FedBE: Making Bayesian Model Ensemble Applicable to Federated Learning, 2021. arXiv:cs.LG/2009.01974].

- Zhang, L.; Shen, L.; Ding, L.; Tao, D.; Duan, L.Y. Fine-tuning global model via data-free knowledge distillation for non-iid federated learning. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2022, pp. 10174–10183.

- Zhu, Z.; Hong, J.; Zhou, J. Data-Free Knowledge Distillation for Heterogeneous Federated Learning. Proceedings of the 38th International Conference on Machine Learning; Meila, M.; Zhang, T., Eds. PMLR, 2021, Vol. 139, Proceedings of Machine Learning Research, pp. 12878–12889.

- Tjell, K.; Wisniewski, R. Privacy preservation in distributed optimization via dual decomposition and ADMM. 2019 IEEE 58th Conference on Decision and Control (CDC). IEEE, 2019, pp. 7203–7208.

- Goodfellow, I.; Pouget-Abadie, J. Generative adversarial nets. Advances in neural information processing systems 2014, 27. [Google Scholar]

- Li, T.; Sahu, A.K.; Zaheer, M.; Sanjabia. Federated optimization in heterogeneous networks. Proceedings of Machine learning and systems 2020, 2, 429–450. [Google Scholar]

- Karimireddy, S.P.; Kale, S. ; Mohri. Scaffold: Stochastic controlled averaging for federated learning. International conference on machine learning. PMLR, 2020, pp. 5132–5143.

- Zhu, Z.; Hong, J.; Zhou, J. Data-free knowledge distillation for heterogeneous federated learning. International conference on machine learning. PMLR, 2021, pp. 12878–12889.

- Varun, M.; Feng, S.; Wang, H.; Sural, S.; Hong, Y. Towards Accurate and Stronger Local Differential Privacy for Federated Learning with Staircase Randomized Response. Proceedings of the Fourteenth ACM Conference on Data and Application Security and Privacy, 2024, pp. 307–318.

- Gad, G.; Gad, E.; Fadlullah, Z.M.; Fouda, M.M.; Kato, N. Communication-Efficient and Privacy-Preserving Federated Learning Via Joint Knowledge Distillation and Differential Privacy in Bandwidth-Constrained Networks. IEEE Transactions on Vehicular Technology 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Q.; Chen, S.; Long, Q.; Su, W. Federated f-differential privacy. International conference on artificial intelligence and statistics. PMLR, 2021, pp. 2251–2259.

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2016, pp. 770–778.

- Fang, G.; Song, J.; Shen, C.; Wang, X.; Chen, D.; Song, M. Data-free adversarial distillation. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1912.11006 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Krizhevsky, A.; Hinton, G.; others. Learning multiple layers of features from tiny images 2009.

- MNIST handwritten digit database, Yann LeCun, Corinna Cortes and Chris Burges — yann.lecun.com. https://yann.lecun.com/exdb/mnist/, 2010. [Accessed 14-08-2024].

- Acar, D.A.E.; Zhao. Federated learning based on dynamic regularization. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2111.04263 2021. [Google Scholar]

- He, C.; Li, S.; So. Fedml: A research library and benchmark for federated machine learning. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2007.13518 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Yurochkin, M. ; Agarwal. Bayesian nonparametric federated learning of neural networks. International conference on machine learning. PMLR, 2019, pp. 7252–7261.

- Talaei, M.; Izadi, I. Adaptive Differential Privacy in Federated Learning: A Priority-Based Approach. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2401.02453 2024. [Google Scholar]

| Model Name | Local Model | KD | Generator | Privacy against DRA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FedAvg | CNN | × | - | × |

| FedProx | CNN | × | - | × |

| SCAFFOLD | CNN | × | - | × |

| FedGen | ResNet18 | Autoencoder | × | |

| FedFTG | ResNet18 | GAN | × | |

| FedRand | CNN | × | - | |

| FedKD | MLP | No generator | ||

| f-differential | CNN | × | - | |

| FedSGAN | ResNet18 | GAN |

| Model Name | CIFAR-10 | MNIST | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FedAvg | 82.04 | 79.59 | 93.84 | 90.16 | ||

| FedProx | 82.36 | 80.12 | 93.83 | 90.10 | ||

| SCAFFOLD | 84.55 | 82.14 | 97.14 | 95.94 | ||

| FedGen | 82.23 | 79.72 | 95.52 | 93.03 | ||

| FedSGAN | 85.78 | 82.254 | 94.07 | 91.81 | ||

| FedFTG | 86.06 | 84.38 | 98.91 | 97.01 | ||

| FedRand | f-differential | FedAvg | FedAKD | FedSGAN | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 97.1 | 98.74 | 78.12 | 60.15 | 98.71 |

| 5 | 96.2 | 98.72 | 78.16 | 60.14 | 98.71 |

| 10 | 94.3 | 98.55 | 70.15 | 60.16 | 98.71 |

| 20 | 34.5 | 90.11 | 46.15 | 20.48 | 98.71 |

| FedRand | f-differential | FedSGAN | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 64.20 | 64.72 | 86.06 |

| 5 | 60.00 | 62.55 | 86.06 |

| 10 | 42.20 | 59.61 | 86.06 |

| 20 | 22.40 | 34.12 | 86.06 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).