1. Introduction

With the increasing popularity of IoT devices, the amount of distributed data has skyrocketed. The total amount of global data will grow to 175 ZB by 2025[

1], and the increase in data volume has promoted the development of artificial intelligence in many fields such as smart medical, smart home, and traffic accident detection and artificial intelligence-driven by the big data environment has entered the third golden period of development. Traditional centralized learning requires all data collected on local devices to be stored centrally in a data center or cloud server. This requirement not only raises concerns about privacy risks and data breaches but also places high demands on the storage and computing power of servers, particularly in cases involving large amounts of data. Distributed data parallelism enables multiple machines to train a copy of a model in parallel, using different sets of data. While it may be a potential storage solution and compute power issues, it still requires access to the entire training data, segmenting it into evenly distributed fragments, which can pose security and privacy concerns for the data.

Federated learning aims to train a global model that can train on data distributed across different devices while protecting data privacy. In 2016, McMahan et al. first introduced the concept of federated learning based on data parallelism [

1] and proposed the federated averaging (FedAvg) algorithm. As a decentralized machine learning approach, FedAvg enables multiple devices to collaborate in training machine learning models while storing user data locally. FedAvg eliminates the need to upload sensitive user data to a central server, enabling edge devices to train shared models locally using their own local data. By aggregating updates of local models, FedAvg meets the basic requirements of privacy protection and data security.

While federated learning offers a promising approach to privacy protection, numerous challenges arise when applying it to the real world[

2]. The first is the problem of privacy. Studies in recent years have shown that gradient information during training can reveal privacy [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9], whether by third parties or central servers [

10,

11]. As shown in [

12,

13], even a slight gradient can reveal a significant amount of sensitive information about local data. By simply observing the gradient, a malicious attacker can steal training data within a few iterations [

6]. Although traditional privacy protection methods, such as encryption and secure multi-party computing, can protect private information from being leaked, they are not designed for edge environments. Excessive algorithm complexity leads to high latency and communication overhead in practical applications. To solve the above problems, this paper proposes an efficient federated learning method that combines differential privacy and outdated level methods. The main contributions of this paper are as follows:

This paper proposes a differential privacy method with adaptive parameters that dynamically adjusts privacy parameters during training. This method improves the accuracy of federated learning while maintaining the total privacy budget.

This paper proposes an asynchronous federated learning aggregation scheme that combines privacy budget and device aging. This scheme adjusts weights based on privacy budget, device aging, and dataset during aggregation to improve training accuracy.

This paper conducts extensive experimental testing and validates the effectiveness of the algorithm using real-world datasets under Gaussian and Laplace noise.

2. Related Work

Differential privacy is a new definition of privacy proposed in 2006 by Dwork cite dwork2006differential for addressing the problem of privacy leakage in databases. It is mainly through the use of random noise to ensure that the results of querying publicly visible information do not reveal the private information of the individual, that is, to provide a way to maximize the accuracy of the data query when querying from a statistical database, while minimizing the chance of identifying its records. Differential privacy enhances the ability to protect privacy by sacrificing some data accuracy. Determining how to balance privacy and efficiency in the actual use process is a problem worth studying.

In response to differential attacks, Robin C. et al. [

14] propose a federated optimization algorithm for client differential privacy protection. This algorithm dynamically adjusts the level of differential privacy during distributed training, aiming to hide customer contributions during training while balancing the trade-off between privacy loss and model performance. Xue J. et al.[

15] proposed an improved SignDS-FL framework, which shares the same dimension selection concept as FedSel but saves privacy costs during the value perturbation stage by assigning random sign values to the selected dimensions. Patil et al. [

16] introduced the concept of differential privacy into traditional random forests cite breiman2001random. The Random Forest algorithm was tested in three aspects. The experiments demonstrated that the traditional random forest algorithm and the random forest based on differential privacy achieved nearly identical classification accuracy. Badih Ghazi et al. [

17] improve the privacy guarantee of the FL model by combining the shuffling technique with DP and masking user data using an invisibility cloak algorithm. Cai et al.[

18]proposed the idea of differential private continuous release (DPCR) into FL and proposed a FL framework based on DPCR (FL-DPCR) to effectively reduce the overall error added to the parameter model and improve the accuracy of FL. Wang et al.[

19]propose a Loss Differential Strategy (LDS) for parameter replacement in FL. The key idea is to maintain the performance of the Private Model by preserving it through parameter replacement with multiuser participation while significantly reducing the efficiency of privacy attacks on the model. However, some solutions cite new1, new2, new3, new4, new5 introduce uncertainty into the upload parameters and may compromise the training performance. The current research schemes are all aimed at protecting the privacy of federated learning at the cost of accuracy. We aim to enhance the training accuracy of federated learning by optimizing the allocation of privacy budgets and the aggregation scheme while preserving privacy.

3. Problem Formulation

3.1. Model Definition

Neural networks update parameters through backpropagation. Similarly, in a federated learning framework based on gradient (weight) updates, gradient information is propagated between clients and servers. The gradient information transmitted by clients originates from local datasets. Attackers can use gradient information to reverse-engineer datasets, resulting in privacy leaks among participants in federated learning.

Definition 1 (Differential Privacy Problem Model)

. A trusted data regulator C has a set of data . The goal of the data regulator is to derive a random algorithm , where describes certain information about the data set , while ensuring the privacy of all data D.

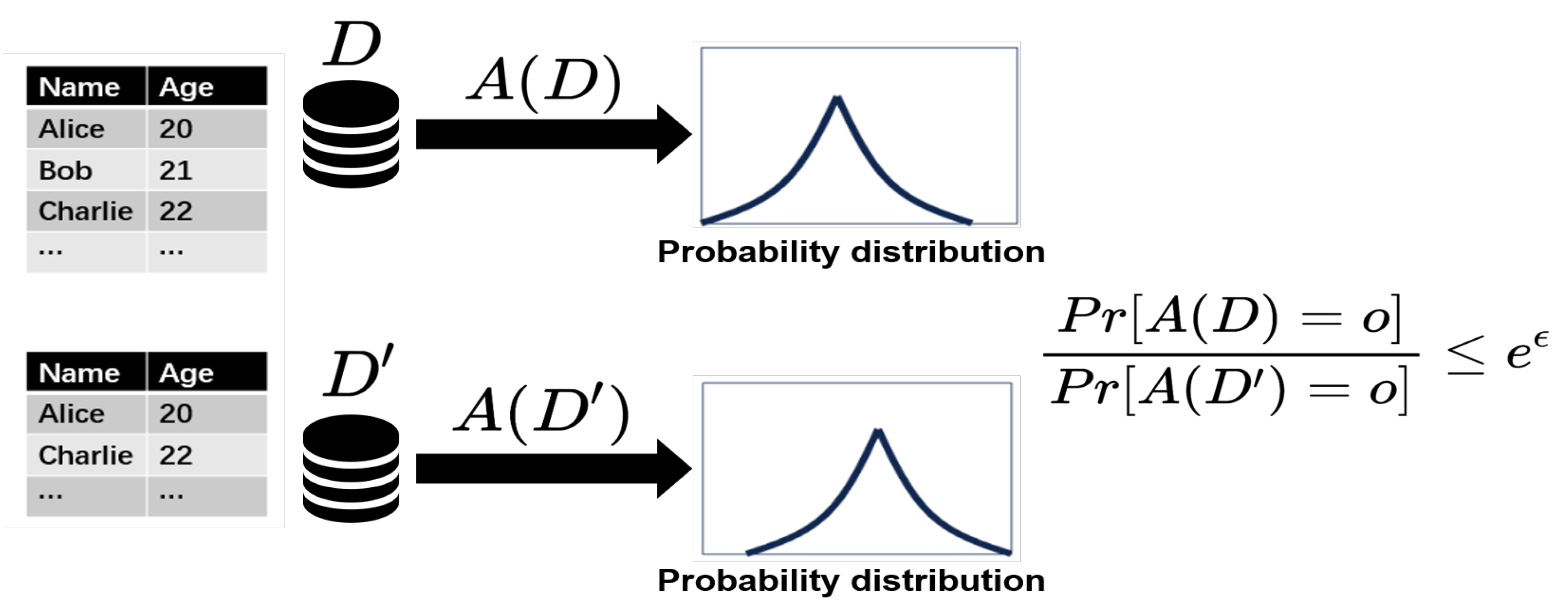

The schematic diagram of differential privacy is shown in

Figure 1. For example, for a query on the average age, the average age of all individuals in the query dataset

D is first calculated, followed by the average age of the adjacent dataset

, which lacks Bob’s age. This can be inferred from the results of the previous two queries, which constitute a differential attack. The figure illustrates the core idea of differential privacy technology, which involves processing query results to ensure that the query algorithm produces highly similar output probability distributions on adjacent datasets. Thus, for datasets with only one record difference, the query results are likely to be the same. Differential privacy applications can effectively prevent attackers from inferring information about datasets through gradient analysis. However, the added noise inevitably leads to reduced accuracy and slower convergence in federated learning and may even prevent convergence. Therefore, finding a method to minimize the impact of differential privacy on accuracy while ensuring privacy security has become an urgent research issue.

3.2. Algorithm Definition

This section introduces the relevant definitions and basic properties that will be applied in the composition of adaptive differential privacy algorithms. Differential privacy is defined as follows:

Definition 2 (Adjacent data sets)

. For data sets D and with the same data structure, if these two data sets differ only in a certain element x, then these two data sets are called adjacent data sets.

Definition 3 (Differential Privacy)[

20])

. A randomized algorithm with domain is -differentially private if for all Range() and for all such that :

where the probability space is over the coin flips of the mechanism . If , we say that is ϵ differentially private. satisfies differential privacy, then when δ = 0, satisfies differential privacy.

differential privacy guarantees that the absolute value of privacy loss for all adjacent databases is less than or equal to ϵ. differential privacy guarantees that the probability of privacy loss for all adjacent databases being less than or equal to ϵ is , meaning that a privacy algorithm failure with a probability of δ is acceptable. This is a relatively lenient differential privacy strategy.

Definition 4 (Local Sensitivity)

.

Local sensitivity of FL training is defined as follows:

Definition 5 (Global Sensitivity)

.

Global sensitivity of FL training is defined as follows:

Definition 6 (Laplace Mechanism)

.

For input dataset and function , if the algorithm Γ satisfy:

Theorem 1 (Gaussian Mechanism)[

20])

. For any , if algorithm Γ satisfies:

then algorithm Γ satisfies differential privacy. is a Gaussian distribution with center 0 and variance .

Theorem 2 (Composition Theorem)[

20])

. Let each provide -differentially private. The sequence of provides -differentially private.

The differential privacy method selected for this study is a differential privacy algorithm based on the Laplace noise mechanism and the Gaussian noise mechanism.

4. Adaptive Differential Privacy Mechanisms For Federated Learning

In this section, we will introduce the building blocks of our method and explain how to implement our algorithm. In

Section 4.1, we introduced adaptive differential privacy design. In

Section 4.2, we introduced security analysis and scheme design. In

Section 4.3, we provided a detailed explanation of the ADP-FL algorithm implementation.

4.1. Design of Adaptive Differential Privacy

Differential privacy technology was first proposed by Dwork in 2006[

20] to prevent differential attacks from obtaining sensitive information about a single record, thereby protecting the confidentiality of data. For example, for a query for average wages, select a set of 100 people, query the average wages of these 100 people, and then query the average wages of any 99 people in the set. The wages of the remaining one person can be analyzed by the results of the first two queries, which is a differential attack. The core idea of differential privacy technology is to process query results in a way that, for a dataset with only one record difference, the query result is likely to remain the same.

According to the composition theorem, when deploying differential privacy multiple times on the same input data, the requirements of differential privacy can still be met. However, it should be noted that there is a correlation between the outputs of each algorithm in serial composition, which leads to an increase in the overall privacy budget and failure probability , thereby reducing the effectiveness of privacy protection. In particular, when different differential privacy methods are applied multiple times on the same dataset, the level of privacy protection may be significantly weakened.

Therefore, allocating privacy budgets of different sizes according to the various stages of federated learning has greater advantages than the traditional method of evenly distributing privacy budgets.

In the early stages of federated learning, the gradient information contains less sensitive information, allowing for a more relaxed privacy budget to be adopted. As training progresses, the privacy information contained in the delayed gradient increases, and the privacy budget must be reduced to protect user information. Based on this idea, this paper employs an optimization algorithm that adjusts the client’s privacy budget in real time according to the model’s training progress and accuracy, ensuring that the overall privacy budget remains unchanged. By dynamically allocating the privacy budget, this paper achieves a more balanced approach between privacy protection and model performance during federated learning. This strategy of allocating privacy budgets of different sizes for various stages of federated learning enables the method proposed in this paper to flexibly address privacy protection requirements while fully utilizing the dataset’s information to enhance the model’s accuracy and performance.

Since our overall method gradually reduces the privacy budget

as training progresses, we use Newton’s cooling law formula to adjust

for each training round. The adaptive adjustment process of the privacy budget

can be formalized as:

Where t is current communication round, E is maximum communication round, is the adjustment coefficient that defaults to 0.1.

Algorithm 1 demonstrates the adaptive differential privacy process. When the client begins participating in federated learning, the cumulative privacy budget is set to 0. As training progresses, if the cumulative privacy budget exceeds the total privacy budget, continuing to participate in federated learning will result in privacy leakage risks, so the client exits federated learning. It is important to note that the decline curve of Newton’s cooling law is very rapid. To prevent the privacy budget from depleting too quickly, which could lead to excessive noise and negatively impact training, this paper introduces a detection callback mechanism. When the client detects that the model’s accuracy has decreased beyond a threshold—i.e., when noise is affecting model convergence—the privacy budget is adjusted accordingly. Through this mechanism, this paper achieves a balance between privacy and efficiency.

|

Algorithm 1 Adaptive Differential Privacy |

-

Input:

privacy budget , accumulated privacy budget , Coefficient , Maximum number of communication rounds E

-

Output:

- 1:

- 2:

while and do

- 3:

if then

- 4:

- 5:

else

- 6:

=

- 7:

end if

- 8:

- 9:

end while - 10:

return

|

4.2. Design of Weighted Aggregation

In federated learning, due to communication or device issues, some devices may not participate in training for extended periods and are referred to as outdated devices. These outdated devices can lead to a decline in model accuracy, a significant issue in practice. To address this issue, a common approach in the context of federated learning is to adjust the weight of the gradient based on the degree of model obsolescence, thereby reducing the impact of outdated gradient information on the model. This paper adjusts the weights of gradient information based on the number of training rounds the model has not participated in and uses an exponential function to implement this adjustment. Through this approach, this paper can more effectively address the impact of outdated devices that have not participated in training for an extended period, thereby improving the overall accuracy of the model. This dynamic weight adjustment strategy ensures that the contribution of outdated devices in model updates gradually decreases, allowing the updates from devices that participate on time to be more significant. Therefore, this paper can better balance the contributions of different devices, thereby enhancing the effectiveness of federated learning and the model’s performance. The obsolescence degree function we use is as follows:

Where is the current communication round, is the last communication round of the client, and is the adjustment coefficient. is the outdated coefficient. It is initially set to 1 and reset to 1 each time it participated in training.

According to the characteristics of the exponential function, the weights of clients who have not participated in training for multiple rounds will be tiny, effectively reducing the impact of outdated information.

During parameter aggregation, differential privacy noise impacts the model’s convergence. Clients with smaller privacy budgets have a higher probability of their uploaded gradient parameters deviating from the model convergence direction. Therefore, it is necessary to adjust the weights based on the amount of noise added by the client. Regarding how to assess the amount of noise added, the privacy budget and the amount of noise added are negatively correlated. The smaller the privacy budget, the more noise is added and the greater the deviation of gradient information. Naturally, this paper uses the privacy budget as a parameter to assess the degree of noise added and uses as one of the weight parameters for model aggregation.

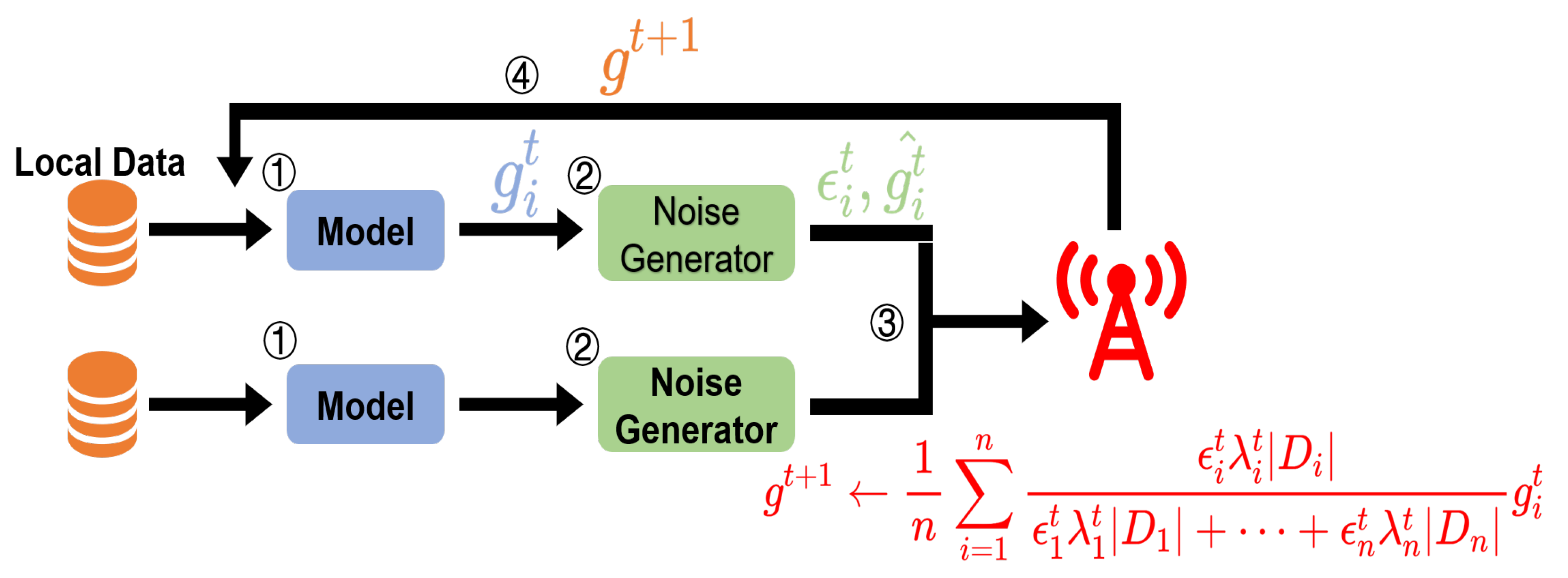

Combining the weight adjustment algorithm for outdated devices and the weight adjustment algorithm for noise, this paper proposes the following aggregation scheme:

Where is the gradient of client i in round t. is the size of the dataset for client i. In this formula, the more noise, the older the model, and the smaller the weight of the gradient provided by the client. When the client continuously participates in training and adjusts the privacy budget , the weight in the aggregation will increase.

Accordingly, the calculation method for the global model is:

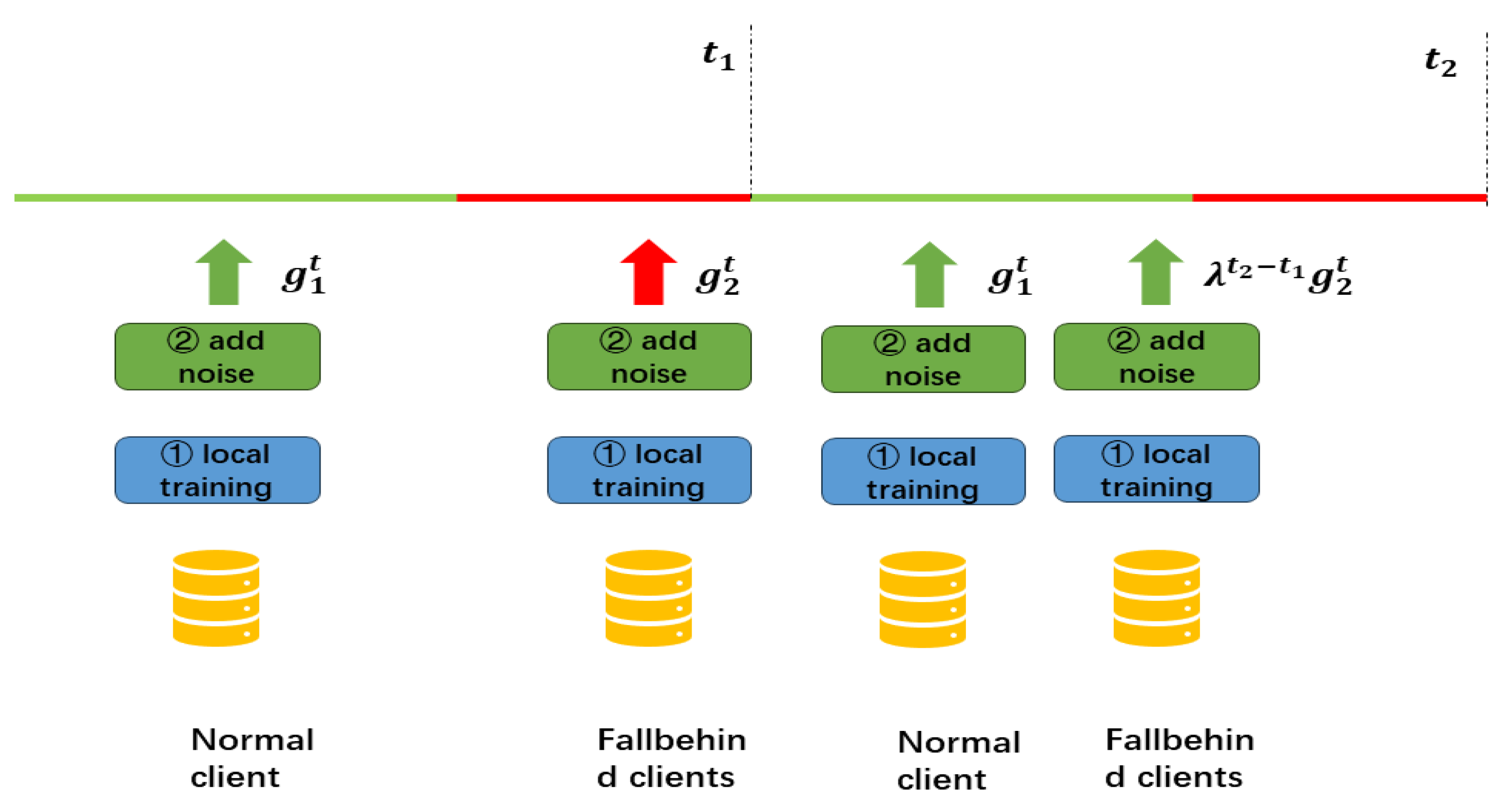

The flowchart of the aggregation scheme is shown in

Figure 2. As shown in the figure, in a training round, the green portion represents the time window during which the server receives gradients from clients. In contrast, the red portion represents the time window during which the server performs aggregation and updates the global model. Clients that upload gradients during the green time window are considered regular clients participating in aggregation. Clients who upload gradients during the red time window or do not upload gradients are marked as lagging clients. For users marked as lagging clients, their aggregation weights will decay exponentially over time, allowing them to participate in normal model aggregation again.

4.3. Adaptive Differential Privacy Federated Learning Algorithm

Based on the previously proposed method, we propose Adaptive Differential Privacy Federated Learning (ADP-FL).

Figure 3 is the overview of ADP-FL. Algorithm 2 shows the whole process of ADP-FL.

is the Adaptive Differential Privacy function. The specific details of the algorithm are as follows:

|

Algorithm 2 ADP-FL |

-

Input:

initial paramenters w, privacy budget , maximum communication round E, accumulated privacy budget , Current communication round t, outdated level . - 1:

Server does: - 2:

Send initial parameters w to all clients i

- 3:

while do

- 4:

- 5:

Return to each selected client i

- 6:

Set participating clients’ to 1, other clients’

- 7:

end while - 8:

Client does: - 9:

Recieve initial parameters w

- 10:

if client i selected and then

- 11:

receive from server - 12:

local train

- 13:

- 14:

add noise

- 15:

- 16:

return to server - 17:

end if |

(1) Steps 2 to 7 are performed by the server. In Step 2, the server initializes the model w and sends it to all clients. Before reaching the maximum communication round E, the server receives the gradient information sent by the clients, aggregates the gradients of each participating client according to the aggregation scheme proposed in this paper, and updates the global model , then is sent to participating clients to update their local models. After the update is complete, the server resets the obsolescence level of participating clients to 1 based on their participation in this update, and sets the obsolescence level of non-participating clients to , thereby implementing the algorithm.

(2) Steps 8 to 15 are performed by the client. During the preparation phase of federated learning training, the client receives the initial model w. When the client is selected and the privacy budget has not been fully consumed, the client first receives the latest model parameters from the server. Based on the local dataset and the latest global model , local training is performed to obtain the local gradient . The privacy budget for this round of training is calculated as . Based on the privacy budget and the Laplace mechanism or Gaussian mechanism, perturbation noise is generated and added to the gradient information, yielding the perturbed gradient information , while the cumulative consumed privacy budget is updated as .

5. Experiment

5.1. Experimental Environment

The experimental environment of this paper is AMD Ryzen 7 5800H with Radeon Graphics @3.20 GHz processor and NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3060 Laptop GPU, and the operating system is Windows10.

The experiment simulated a server and 50 local client nodes. Non-IID data was constructed based on the MNIST, EMNIST and CIFAR10 datasets. In order to test the effect of the algorithm on highly non-independent and identically distributed data, each client was randomly assigned two kinds of labels, and the data of each client accounts for 10 percents of the data set. The neural network model are RNN, VGG9 and CNN models. Their detailed parameters are shown in

Table 1.

The baseline algorithm used in this paper is the FedAvg algorithm, which evenly distributes the privacy budget. It is also the most commonly used algorithm in current research on federated learning based on differential privacy. Let the total privacy budget for each client be

, the number of clients selected by the server each time be

n, the total number of clients be

N, and the total number of communication rounds in federated learning be

E. Then, for a single client

i, the differential privacy budget

for each upload is:

To test the algorithm’s impact on highly non-IID data, each client was randomly assigned two labels, with each client’s data accounting for 10% of the dataset. The learning rate of the gradient descent model used was 0.01, and the batch size was 16. The number of local training rounds was 3, and the optimizer was SGD. The loss function was CrossEntropyLoss. When testing the accuracy of the ADP-FL algorithm and the baseline algorithm, the privacy budget was set to 1, 5, and 10, with the differential privacy relaxation parameter of the Gaussian mechanism set to 0.00001. When testing the impact of different noise mechanisms, the privacy budget was set more loosely to 10, 20, 30, 40, and 50 to better observe the experimental results.

5.2. Accuracy of Algorithm on Different Datasets

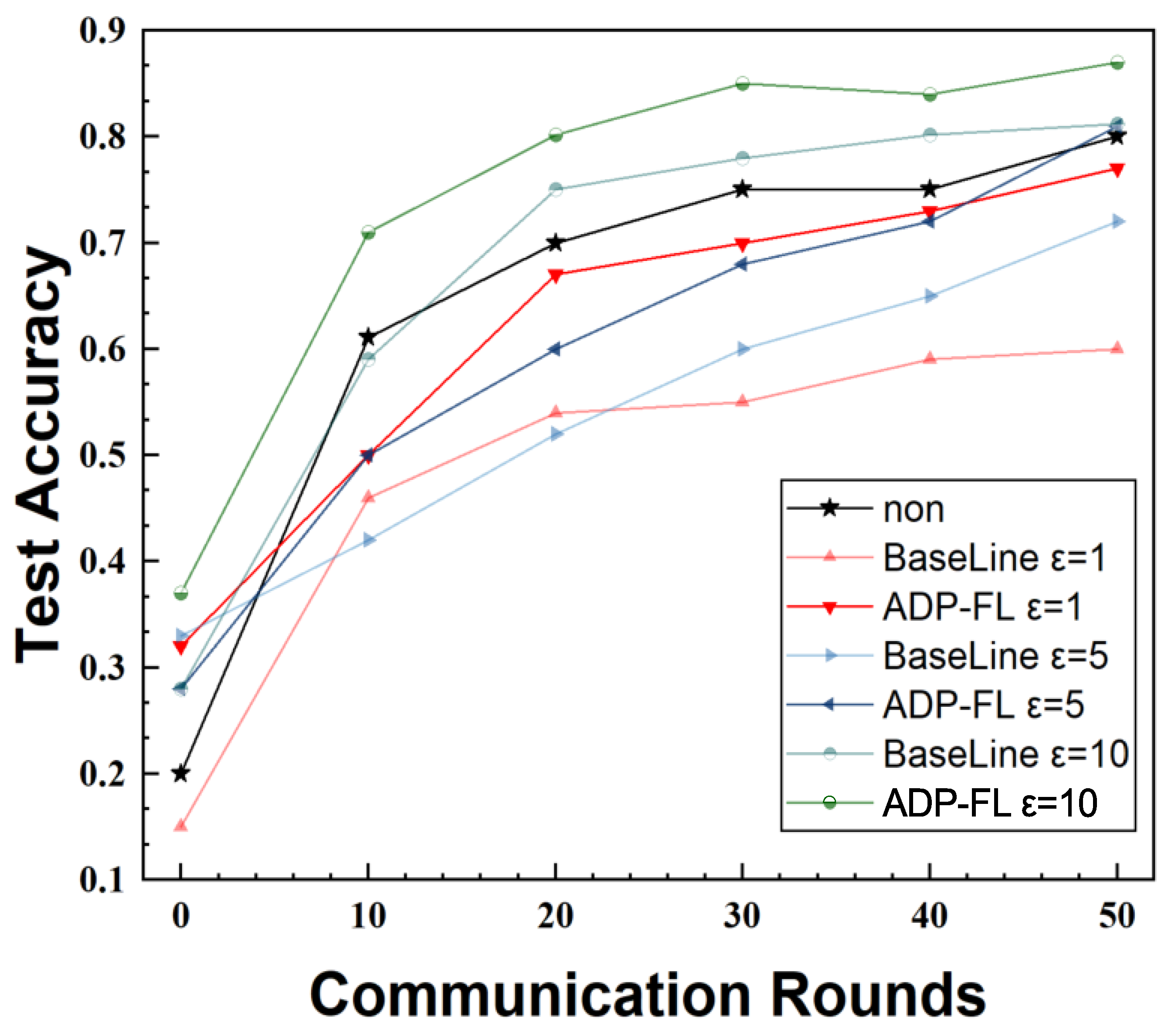

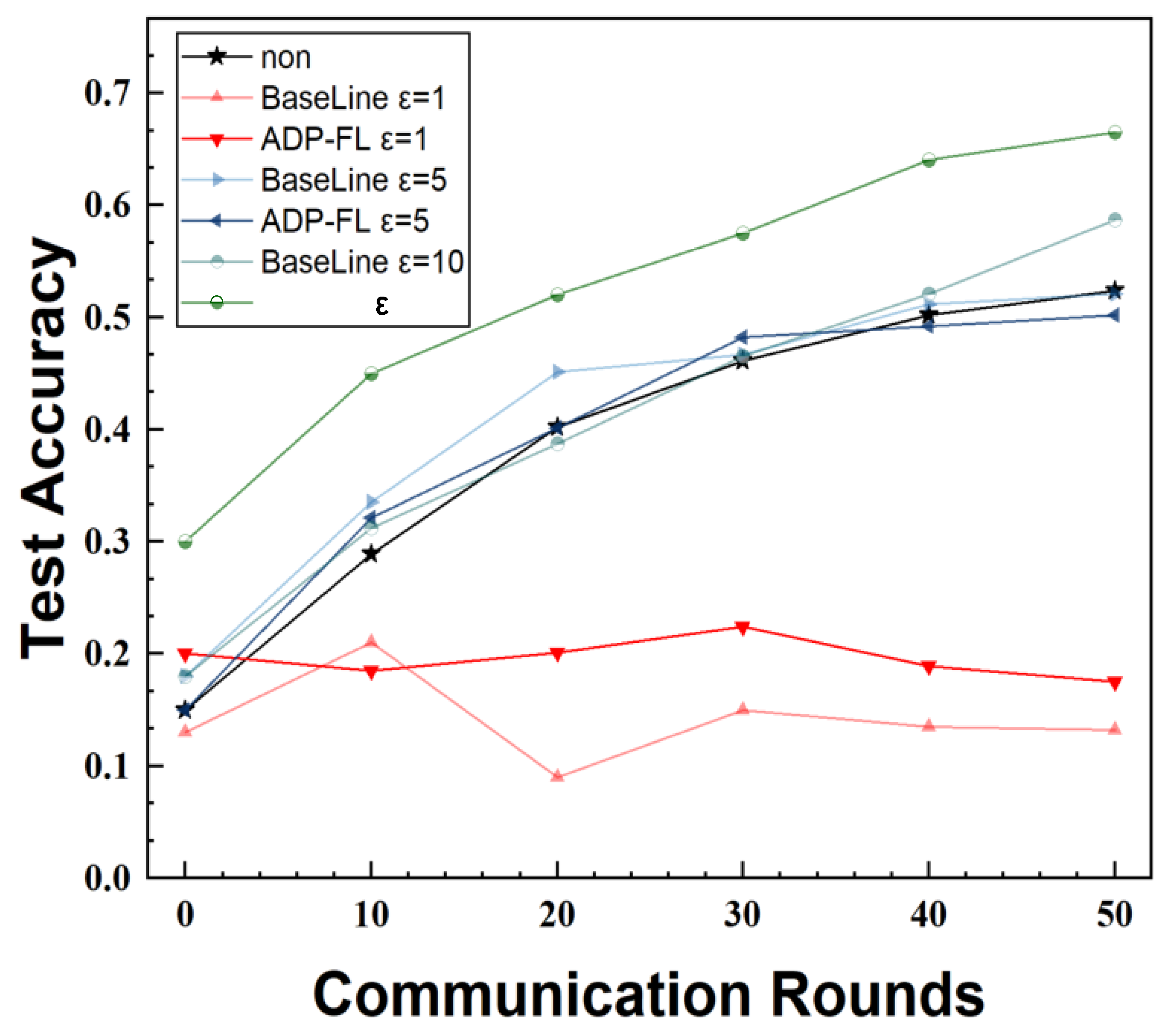

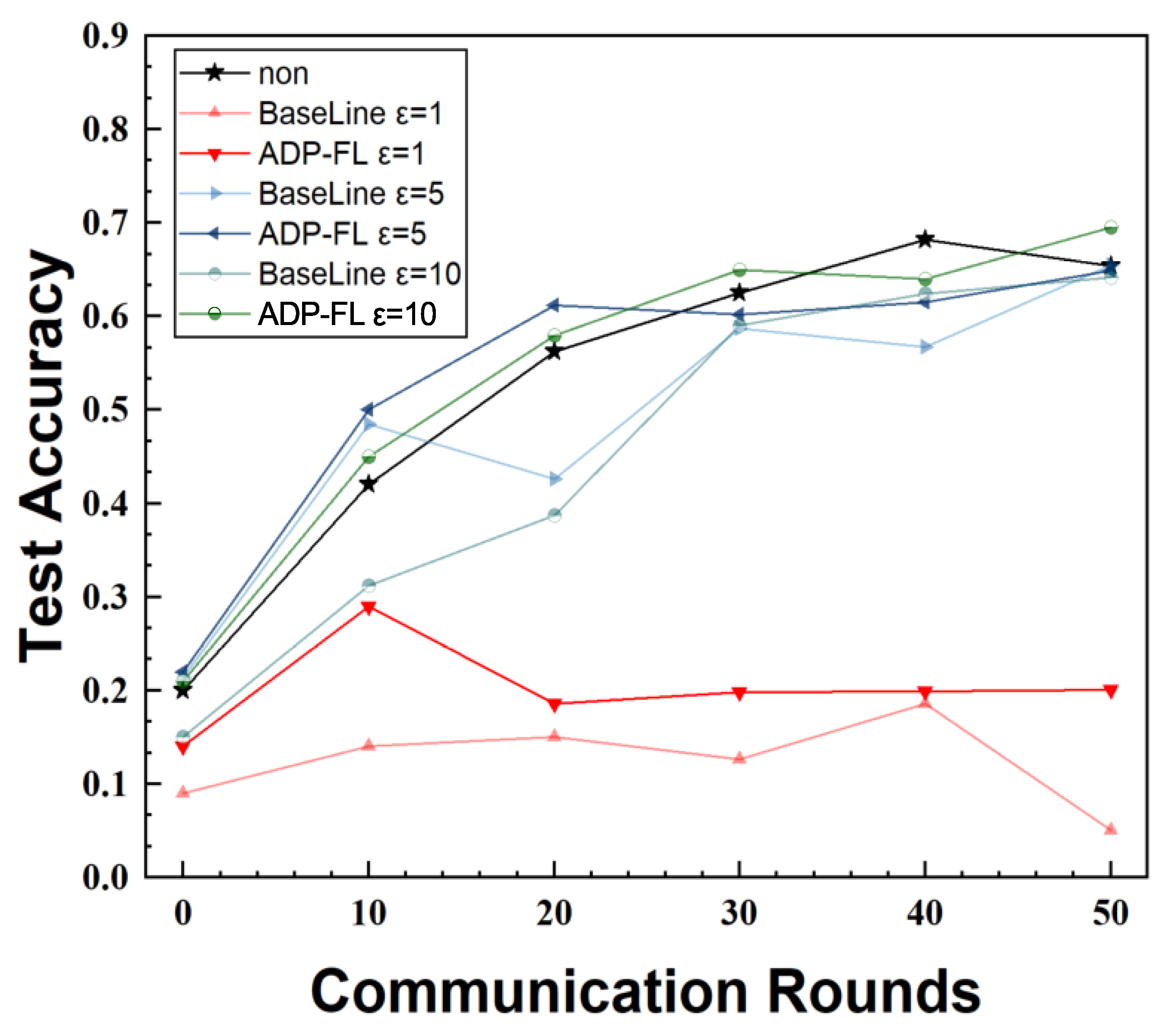

This paper tests the accuracy of the FedAvg algorithm without privacy protection, the FedAvg algorithm with evenly distributed privacy budgets (baseline algorithm), and the ADP-FL algorithm on three datasets under non-IID conditions. The total privacy budget is set to 1, 5, and 10, respectively.

Figure 4,

Figure 5, and

Figure 6 show the accuracy rates of the proposed method and the baseline algorithm on the MNIST, CIFAR10, and EMNIST datasets, with all final accuracy rates listed in

Table 2. Among these, “Non” denotes the FedAvg algorithm without privacy protection, and “Nan” denotes the algorithm failing to converge. Non-convergence occurred on the CIFAR10 and EMNIST datasets when

, as seen in the figure, where the accuracy rate remained at a low level. This paper speculates that this is due to the privacy budget being too small, resulting in excessive noise addition and making it difficult for complex models to converge. In contrast, under the same privacy budget, the algorithm successfully converged on the MNIST dataset with lower complexity.

Compared to the baseline algorithm, the method proposed in this paper achieves higher accuracy and faster convergence speed. When the privacy budget is relatively lenient, the accuracy rate is even higher than that of methods without differential privacy. When , compared to the baseline on MNIST, the proposed method improves accuracy by 15.35%. This is because the proposed aggregation method not only considers the impact of noise but also adjusts the weights of lagging clients. Compared to the baseline algorithm, ADP-FL can effectively address the impact of lagging clients. From the experimental results, it can be seen that in most cases, ADP-FL achieves higher accuracy compared to traditional local differential privacy algorithms.

5.3. Accuracy of Algorithm under Differential Privacy Mechanisms

In order to verify the accuracy of the adaptive differential privacy algorithm on different differential privacy mechanisms, this paper conducted comparative experiments on differential privacy algorithms based on Laplace and Gaussian mechanisms. The experimental results are shown in

Table 3 and

Table 4. Intuitive experimental results are shown in

Appendix A.

From the experimental results, it can be seen that in the vast majority of cases, the ADP algorithm has higher accuracy compared to traditional privacy budget allocation algorithms. Especially under the premise of the same privacy budget, the adaptive differential privacy algorithm proposed in this article performs better in accuracy than traditional differential privacy algorithms with average privacy budget allocation in most cases, whether it is the Laplacian mechanism or the Gaussian mechanism. Especially on the CIFAR10 dataset, the accuracy of the ADP algorithm is generally higher than that of the baseline algorithm. This article speculates that this is because on more complex datasets, the noise added by differential privacy significantly increases, and the superiority of ADP algorithm in reasonable allocation of privacy budget can be better reflected. On the MNIST dataset, the accuracy of the ADP algorithm can exceed that of the baseline algorithm in most cases. The performance is not significant on the EMNIST dataset, because the accuracy of the EMNIST dataset is relatively high, and there is limited room for improvement. A large number of experiments have shown that the ADP algorithm has a certain improvement in accuracy compared to the baseline algorithm.

5.4. Time Complexity of Algorithm Under Differential Privacy Mechanisms

Table 5 shows the computational time costs of the baseline algorithm and ADP-FL algorithm across different datasets. Since federated learning focuses more on client performance, and servers typically have powerful computational resources, this paper selected the average time consumption of the client when calculating time consumption, primarily including local training, noise addition, and gradient transmission processes, and did not test the time consumption of the server. The results clearly show that the ADP-FL algorithm proposed in this paper has less time consumption and is more advantageous in terms of aggregation efficiency.

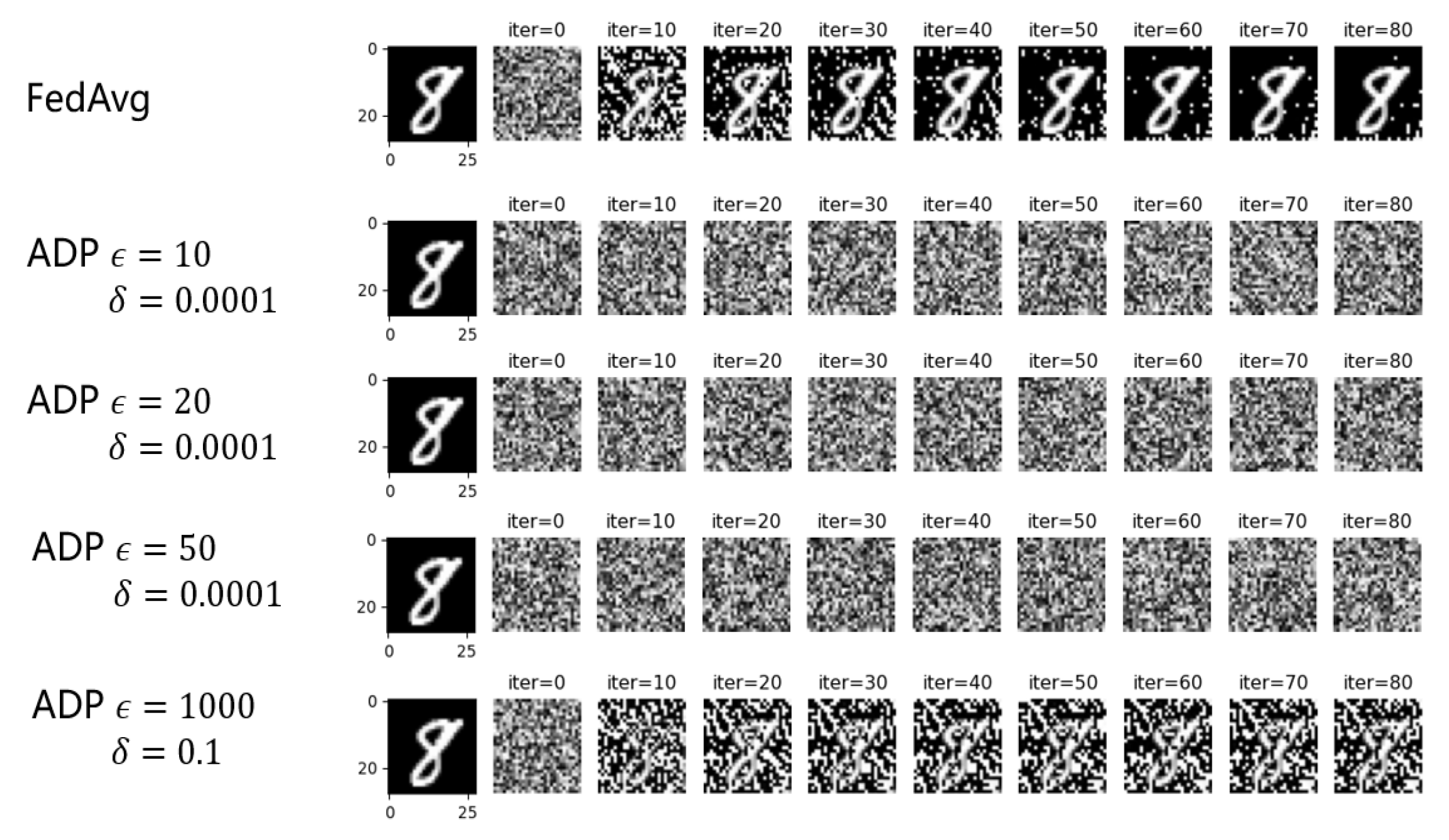

5.5. Gradient Leakage Attack

Figure 7 shows the performance of the ADP-FL algorithm in the face of gradient leakage attacks. From the experimental results, it can be concluded that under the premise of privacy budget

and relaxation term

within the conventional value range, the ADP-FL algorithm in this paper has a significant effect on gradient leakage attacks.

After multiple tests, we found that the ADP-FL algorithm failed when the privacy budget and the slack term . At this point, the privacy budget and relaxation term settings have far exceeded the parameter range in general situations. It can be concluded that the ADP-FL algorithm proposed in this paper can resist gradient leakage attack.

6. Conclusion

In the paper, We proposes ADP-FL, a federated learning method based on adaptive differential privacy. First, based on Newton’s cooling law, ADP-FL dynamically adjusts the privacy budget according to the training progress and accuracy changes. Additionally, this paper optimizes the federated learning aggregation scheme by changing the aggregation weights based on the privacy budget and model obsolescence. Based on MNIST, CIFAR10, and EMNIST, this paper constructs corresponding Non-IID datasets and validates them using RNN, VGG9, and CNN networks. Extensive experiments are conducted on differential privacy algorithms based on Gaussian mechanisms and Laplace mechanisms. The experimental results show that, under the same privacy budget, ADP-FL achieves higher accuracy and lower communication overhead compared to baseline algorithms.

In future work, we will explore the method of introducing cluster[

21] into ADP-FL algorithm, while better compressing the parameters of the model, improving communication efficiency[

22] while improving the security of federated learning.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.W. and G.X.; methodology, J.W.; investigation, H.H. and C.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, J.W. and Y.Z.; writing—review and editing, H.L.; visualization, J.W. and H.L.; supervision, G.X.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

Dataset available upon request from the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

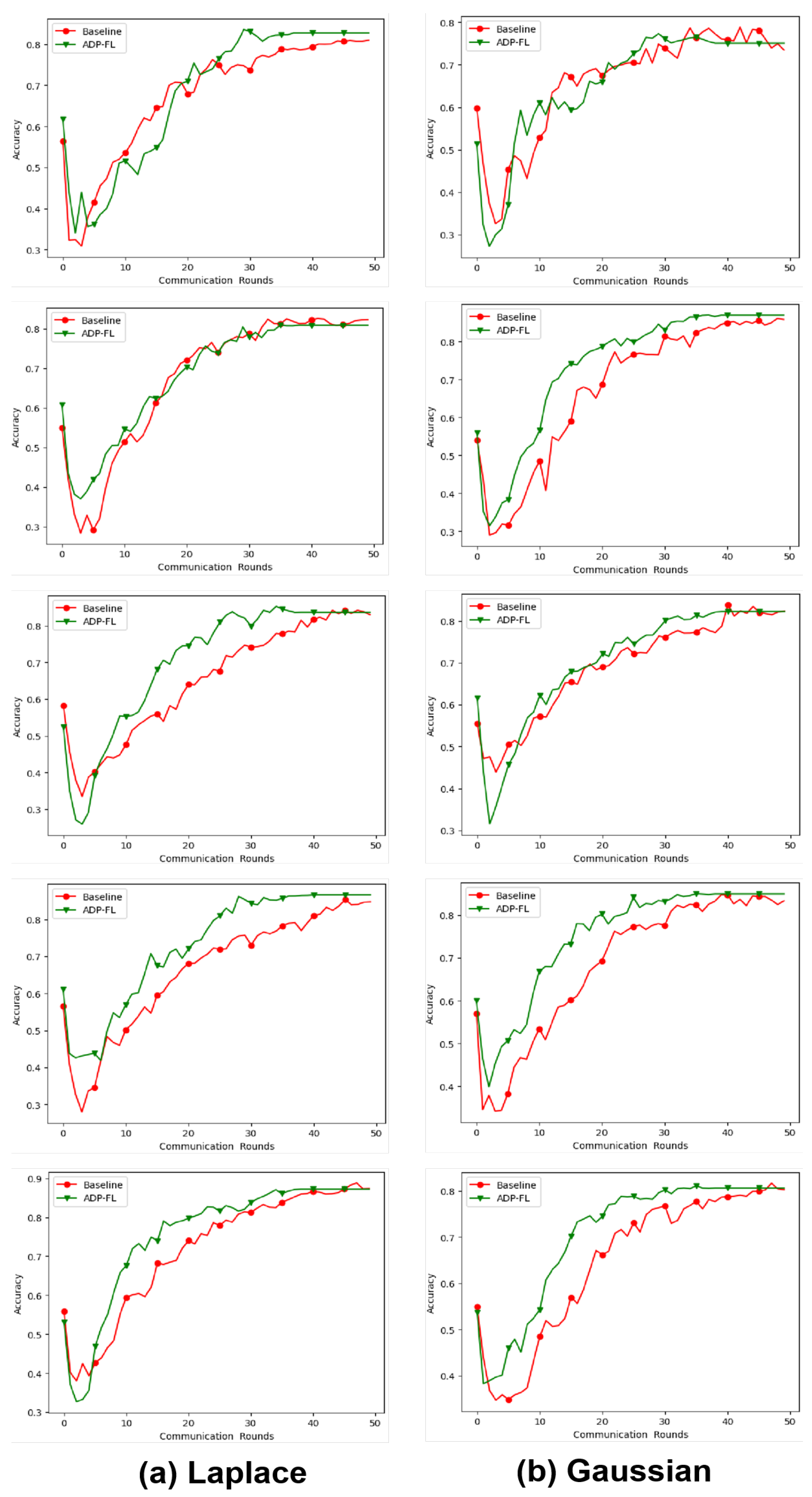

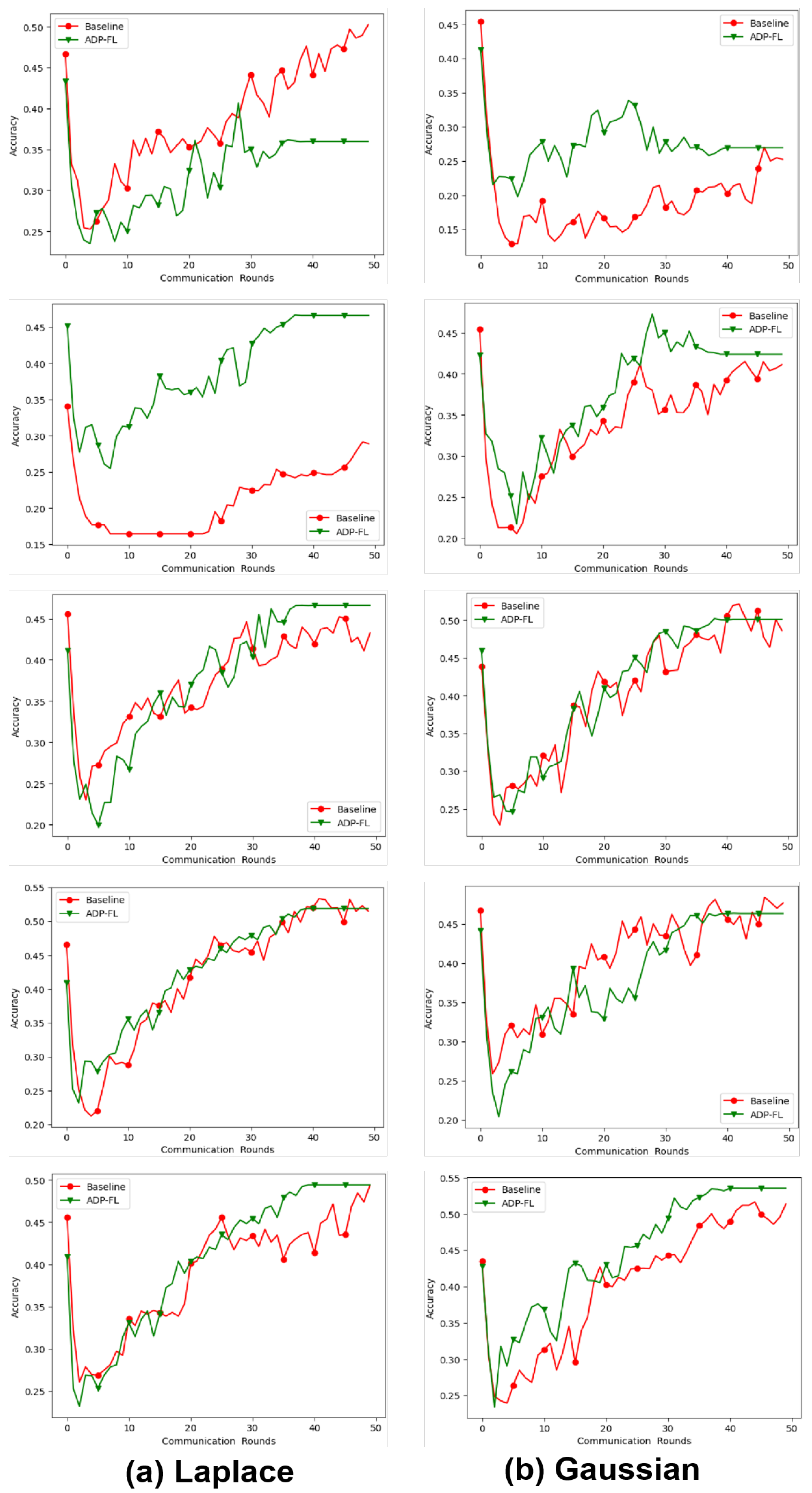

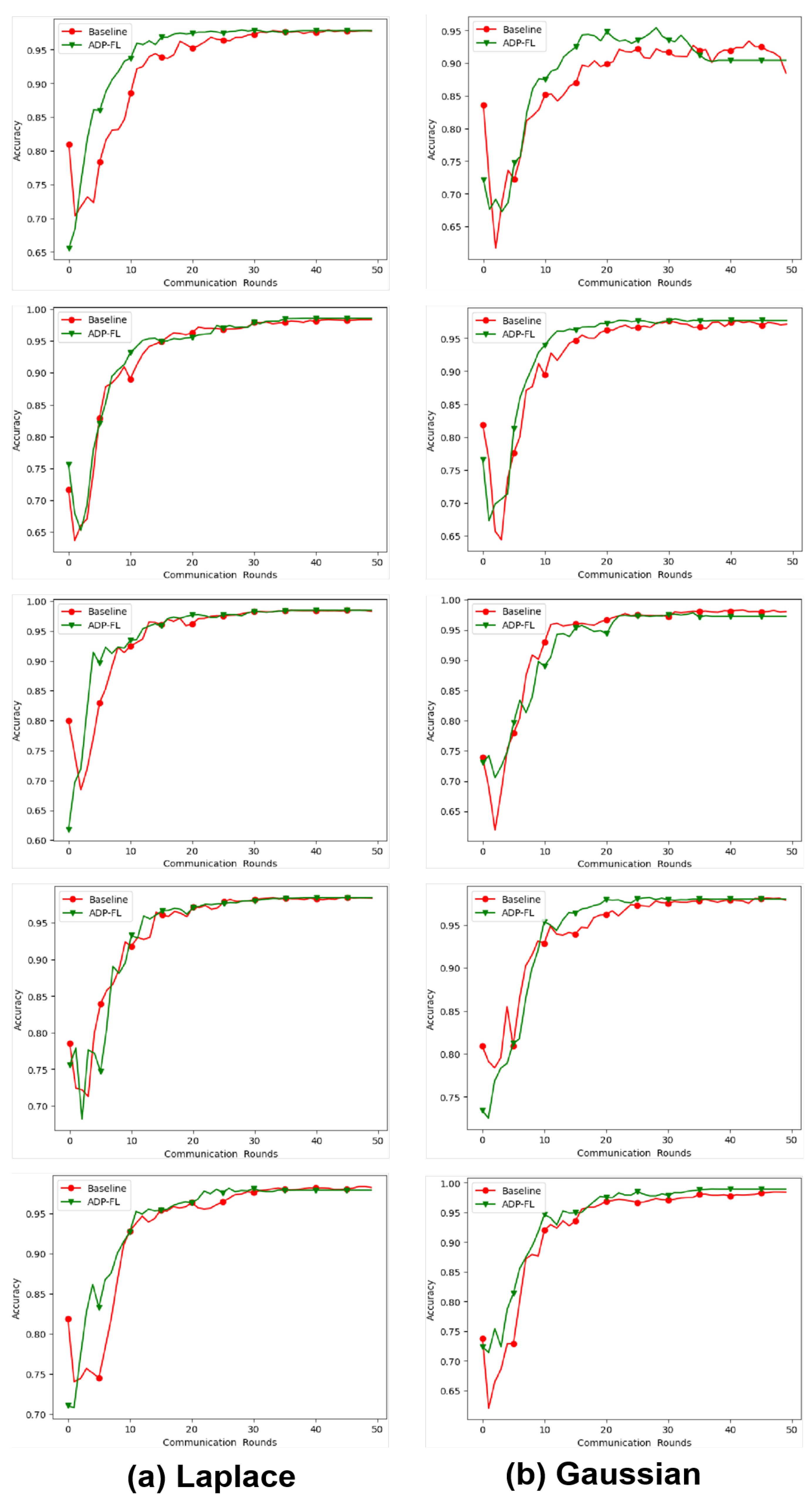

Appendix A

Intuitive experimental results are shown in

Figure A1,

Figure A2, and

Figure A3. The red line represents the accuracy of the baseline algorithm, and the green line represents the accuracy of the ADP-FL algorithm.

Figure A1.

On the MNIST dataset, adaptive differential privacy algorithms based on Laplace and Gaussian mechanisms were tested against the baseline algorithm, with privacy budgets set to 10, 20, 30, 40, and 40 from top to bottom.

Figure A1.

On the MNIST dataset, adaptive differential privacy algorithms based on Laplace and Gaussian mechanisms were tested against the baseline algorithm, with privacy budgets set to 10, 20, 30, 40, and 40 from top to bottom.

Figure A2.

On the CIFAR10 dataset, adaptive differential privacy algorithms based on Laplace and Gaussian mechanisms were tested against the baseline algorithm, with privacy budgets set to 10, 20, 30, 40, and 40 from top to bottom.

Figure A2.

On the CIFAR10 dataset, adaptive differential privacy algorithms based on Laplace and Gaussian mechanisms were tested against the baseline algorithm, with privacy budgets set to 10, 20, 30, 40, and 40 from top to bottom.

Figure A3.

On the EMNIST dataset, adaptive differential privacy algorithms based on Laplace and Gaussian mechanisms were tested against the baseline algorithm, with privacy budgets set to 10, 20, 30, 40, and 40 from top to bottom.

Figure A3.

On the EMNIST dataset, adaptive differential privacy algorithms based on Laplace and Gaussian mechanisms were tested against the baseline algorithm, with privacy budgets set to 10, 20, 30, 40, and 40 from top to bottom.

References

- Xia, G.; Chen, J.; Yu, C.; Ma, J. Poisoning Attacks in Federated Learning: A Survey. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 10708–10722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Liu, Y.; Chen, T.; Tong, Y. Federated machine learning: Concept and applications. ACM Transactions on Intelligent Systems and Technology (TIST) 2019, 10, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, G.; Chen, J.; Huang, X.; Yu, C.; Zhang, Z. FL-PTD: A Privacy Preserving Defense Strategy Against Poisoning Attacks in Federated Learning. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 47th Annual Computers Software, and Applications Conference (COMPSAC); 2023; pp. 735–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhowmick, A.; Duchi, J.; Freudiger, J.; Kapoor, G.; Rogers, R. Protection against reconstruction and its applications in private federated learning. arXiv preprint 2018, arXiv:1812.00984. [Google Scholar]

- Melis, L.; Song, C.; De Cristofaro, E.; Shmatikov, V. Exploiting unintended feature leakage in collaborative learning. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE symposium on security and privacy (SP); IEEE, 2019; pp. 691–706. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, L.; Liu, Z.; Han, S. Deep leakage from gradients. Advances in neural information processing systems 2019, 32. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Z.; Kairouz, P.; Suresh, A.T.; McMahan, H.B. Can you really backdoor federated learning? arXiv preprint 2019, arXiv:1911.07963. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, J.; Ma, H.; Wang, Z.; et al. Survey of privacy-preserving aggregation mechanisms in federated learning. Application Research of Computers 2025, 42, 1601–1610. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.; Zhou, Z.; Wang, Y.; Tong, Y. DM-PFL: Hitchhiking Generic Federated Learning for Efficient Shift-Robust Personalization. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 29th ACM SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, New York, NY, USA, 2023; KDD ’23,; pp. 3396–3408.

- McMahan, H.B.; Ramage, D.; Talwar, K.; Zhang, L. Learning differentially private recurrent language models. arXiv preprint 2017, arXiv:1710.06963. [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal, N.; Suresh, A.T.; Yu, F.X.X.; Kumar, S.; McMahan, B. cpSGD: Communication-efficient and differentially-private distributed SGD. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2018, 31. [Google Scholar]

- Aono, Y.; Hayashi, T.; Wang, L.; Moriai, S.; et al. Privacy-preserving deep learning via additively homomorphic encryption. IEEE transactions on information forensics and security 2017, 13, 1333–1345. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, X.; Wang, W.; Chen, Z.; Wang, B.; Li, C.; Duan, L.; Han, Z.; Han, Y. Finding the PISTE: Towards Understanding Privacy Leaks in Vertical Federated Learning Systems. IEEE Transactions on Dependable and Secure Computing 2025, 22, 1537–1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geyer, R.C.; Klein, T.; Nabi, M. Differentially private federated learning: A client level perspective. arXiv preprint 2017, arXiv:1712.07557. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, X.; Zhou, X.; Grossklags, J. Signds-FL: Local differentially private federated learning with sign-based dimension selection. ACM Transactions on Intelligent Systems and Technology (TIST) 2022, 13, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, A.; Singh, S. Differential private random forest. In Proceedings of the 2014 International Conference on Advances in Computing, Communications and Informatics (ICACCI); IEEE, 2014; pp. 2623–2630. [Google Scholar]

- Ghazi, B.; Pagh, R.; Velingker, A. Scalable and differentially private distributed aggregation in the shuffled model. arXiv preprint 2019, arXiv:1906.08320. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, J.; Liu, X.; Ye, Q.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Y. A Federated Learning Framework Based on Differentially Private Continuous Data Release. IEEE Transactions on Dependable and Secure Computing 2024, 21, 4879–4894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Yang, Q.; Zhu, K.; Wang, J.; Su, C.; Sato, K. LDS-FL: Loss Differential Strategy Based Federated Learning for Privacy Preserving. IEEE Transactions on Information Forensics and Security 2024, 19, 1015–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwork, C. Differential privacy. In Proceedings of the International colloquium on automata, languages, and programming. Springer; 2006; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Arisdakessian, S.; Wahab, O.A.; Mourad, A.; Otrok, H. Towards Instant Clustering Approach for Federated Learning Client Selection. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Computing, Networking and Communications (ICNC); IEEE, 2023; pp. 409–413. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, R.; Cao, Y.; Yoshikawa, M.; Chen, H. Fedsel: Federated sgd under local differential privacy with top-k dimension selection. In Proceedings of the Database Systems for Advanced Applications: 25th International Conference, DASFAA 2020, Jeju, South Korea, September 24–27, 2020; Proceedings, Part I 25. Springer, 2020; pp. 485–501. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).