Introduction

Only a small slice of people who live through something horrific—about 6–8%—ever meet full criteria for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), so built-in biology clearly matters [

1,

2]. Traditional explanations say that biology fails rather late in the game: the amygdala fires too hard, the prefrontal cortex can’t rein it in, and the hippocampus misreads context, all of which let fear run wild [

3]. In that view, risky gene variants in stress hubs such as FKBP5 and CRHR1 disturb glutamate signalling and throw the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis off balance [

4,

5,

6].

Yet more and more findings hint that the fuse is lit long before any trauma occurs. Identical twins who never saw combat still show the same small hippocampi as their PTSD-affected brothers [

7]. Harsh childhoods amplify later risk [

8], and PTSD now shows a hefty genetic overlap with neurodevelopmental disorders such as schizophrenia [

2]. The landmark study tying schizophrenia risk to structural changes in complement component 4 [

9] pushed immune-driven synaptic pruning—how the brain trims extra connections in adolescence—into the spotlight.

The newest, multi-ancestry GWAS of PTSD underscores that shift. It uncovered 95 risk loci—80 never seen before—and the strongest signals pointed not to classic fear genes but to those that steer synaptic pruning, axon guidance and immune control [

2]. Complement proteins, MHC class I molecules and axon-guidance cues were all enriched, mirroring patterns in schizophrenia and hinting at a shared problem: pruning that is simply too aggressive.

Pulled together, the evidence supports a developmental story. Over-zealous, immune-guided pruning quietly weakens key circuits; later trauma then cements the faulty fear and stress responses that define PTSD. By blending these genomic clues with what we know from epigenetics and brain imaging, we can sharpen our model of the disorder and sketch clear, testable targets for future studies and early-stage interventions.

Methods

MAGMA Analysis

We analysed summary statistics from a recent European-ancestry PTSD meta-GWAS [

2]. Gene-based testing relied on MAGMA version 1.10, which implements multiple-regression models that account for local linkage disequilibrium [

10]. Single-nucleotide polymorphisms were assigned to protein-coding genes according to NCBI build 37, with boundaries extended 35 kb upstream and 10 kb downstream to capture regulatory variation. Linkage disequilibrium patterns were estimated from the 1000 Genomes Phase 3 European reference.

Seven hypothesis-driven gene sets were evaluated in competitive mode. Two sets captured glutamatergic signalling—one small candidate list (23 genes) and a broader pathway panel (130 genes). Synaptic pruning was represented by a concise set (38 genes) and an expanded collection derived from guidance, complement and autophagy literature (262 genes). To benchmark specificity, we included monoaminergic genes (101 genes) and a housekeeping panel (182 genes). Because 37 genes overlapped the glutamatergic and pruning lists, we also created a pruning-specific subset (225 genes) by subtracting those overlaps.

For each gene, MAGMA converts the association p value to a normally distributed z statistic. Competitive enrichment was then tested with one-sided t tests that compare the mean z value of a set to the genome-wide distribution while adjusting for gene size, density and local sample size. Statistical significance for sets was judged against a Bonferroni threshold that corrects for the seven planned comparisons (α ≈ 0.0071); false-discovery-rate (FDR) values are additionally reported. At the gene level, Bonferroni correction across 18,012 genes yielded a significance boundary of 2.78 × 10−6.

Annotation Enrichment Analysis and Partitioned Heritability Analysis

We quantified whether post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) risk variants preferentially cluster near predefined biological pathways by implementing a partitioned heritability framework that contrasts average association statistics inside an annotation with those observed genome-wide. GWAS summary statistics were taken from a European-ancestry meta-analysis of PTSD that provided an effective sample of 638,463 individuals [

2]. Variants were converted to a uniform format, retaining single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) with INFO ≥ 0.90, minor-allele frequency ≥ 0.01 and valid two-sided P values.

Seven gene sets were examined. Four represented biological hypotheses: a small candidate list of glutamatergic receptor and plasticity genes (Set A, 23 genes); a broader glutamatergic pathway panel (Set B, 130 genes); a core synaptic pruning list (Set C, 38 genes); and an expanded pruning-related collection (Set D, 262 genes). Two negative-control sets comprised monoaminergic genes (Set E, 101 genes) and housekeeping genes (Set F, 182 genes). Because 37 genes overlapped the glutamatergic and pruning panels, we derived a pruning-specific subset (Set G, 225 genes) by removing those overlaps from Set D.

Gene coordinates (GRCh37/hg19) were extended 10 kb upstream and downstream. Using the 1000 Genomes European reference, SNPs were mapped to these intervals with BEDTools, generating annotation files that indicate membership in each set. Enrichment was estimated as the ratio of the mean chi-square statistic for annotated versus unannotated SNPs. Standard errors were obtained with a block jackknife, and one-tailed significance was evaluated with Mann–Whitney U tests. We controlled family-wise error across the seven hypotheses with a Bonferroni threshold of α ≈ 0.0071 and report false-discovery-rate (FDR) values as complementary evidence.

The analytic pipeline was repeated for every annotation. Stratified linkage-disequilibrium score regression (LDSC) was utilized to estimate the proportion of SNP-heritability (h2) explained, along with its standard error, based on the complete baseline model. Enrichment was characterized as the ratio of observed to anticipated h2. We used one-tailed Z-tests and Mann–Whitney U tests to compare the χ2 distribution of annotated SNPs to that of background SNPs to see if there was a difference. The family-wise error rate was kept in check by a Bonferroni threshold.

Transcriptome-Wide Association Study (TWAS)

To determine whether common-variant risk for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is conveyed through genetically regulated gene expression in brain, we carried out a summary-level transcriptome-wide association study (TWAS) with S-PrediXcan. The procedure follows exactly the framework described by Barbeira and colleagues [

11] and is mathematically equivalent to individual-level PrediXcan [

12], but requires only GWAS summary statistics.

The input GWAS was the European-ancestry meta-analysis reported in [

2]. For gene-expression prediction we used the GTEx v8 multi-tissue elastic-net models trained with MASHR shrinkage; weight matrices and SNP–SNP covariance files (Zenodo record 3518299) were available for six neuroanatomical regions that participate in fear processing and stress adaptation—frontal cortex (BA9), anterior cingulate cortex (BA24), hippocampus, amygdala, nucleus accumbens and caudate.

For every gene–tissue model, the association statistic was obtained. Two-sided P-values were derived from the standard normal distribution. False-discovery rate (FDR) adjustment was applied across all gene–tissue combinations, and Bonferroni correction was applied within each tissue.

To evaluate pathway-level signal we focused on the same seven a-priori gene sets used in the heritability analyses: three pruning pathways (C, D, G), two glutamatergic sets (A, B) and two negative controls (E, F). For each set we compared the absolute TWAS Z-scores of member genes with those of all other genes, computing enrichment as the ratio of means and assessing significance with one-tailed Mann–Whitney tests.

Results

MAGMA Analysis

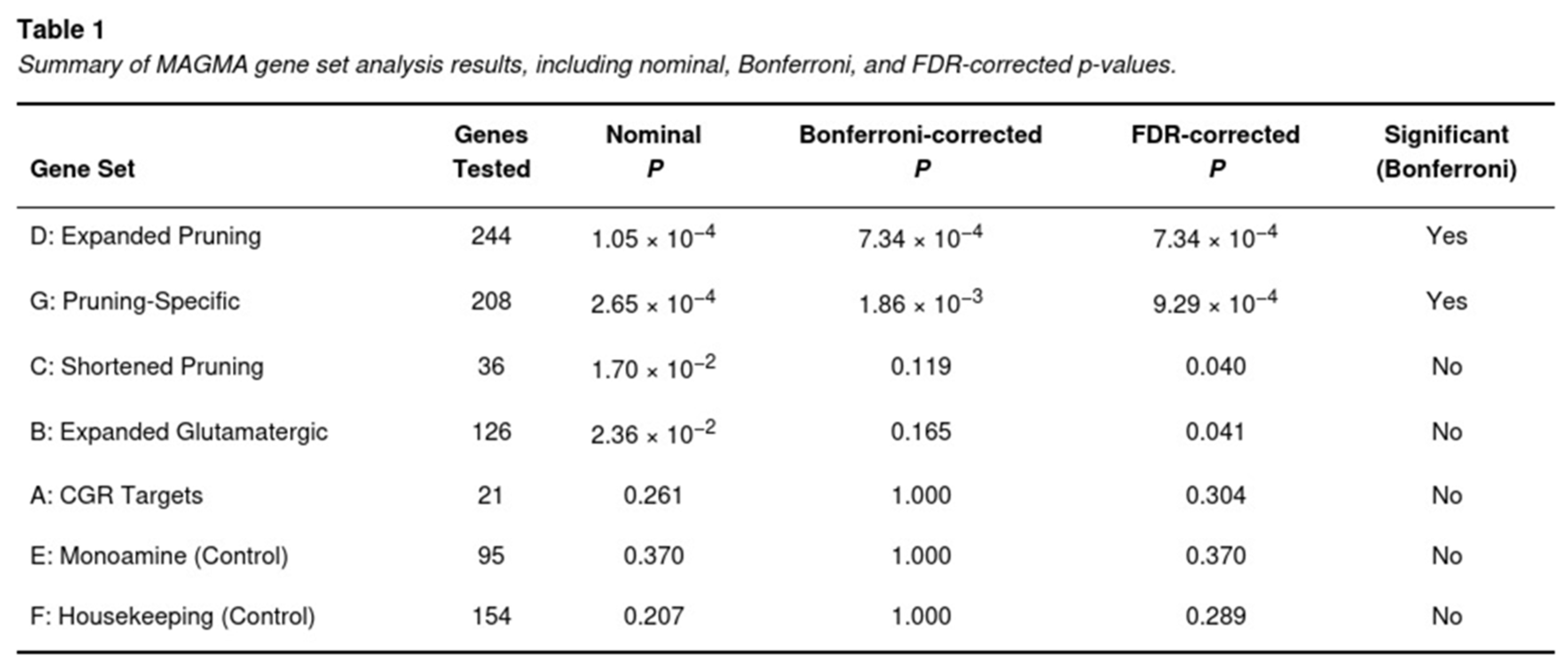

Across 18,012 loci, 235 met the stringent Bonferroni criterion. Top signals mapped to synaptic and immune functions: NCAM1 (Z = 6.61, p = 1.92 × 10−11), the class-I MHC gene HLA-B (Z = 6.23, p = 2.39 × 10−10), and axon-guidance ligands SEMA3F (Z = 5.79, p = 3.54 × 10−9) and EFNA5 (Z = 5.62, p = 9.66 × 10−9). Nominal evidence (uncorrected p < .05) was observed for 3,959 additional genes.

Two pruning-related sets surpassed the Bonferroni threshold (Table 1). The expanded pruning collection (244 genes after mapping) yielded p = 1.05 × 10−4 (Bonferroni-adjusted p = 7.34 × 10−4). Removing glutamatergic overlaps did not diminish the signal; the pruning-specific subset remained significant (p = 2.65 × 10−4; adjusted p = 1.86 × 10−3). The shorter pruning list and the broad glutamatergic panel reached FDR but not Bonferroni significance. Neither the small candidate glutamate genes nor the monoaminergic and housekeeping controls showed enrichment.

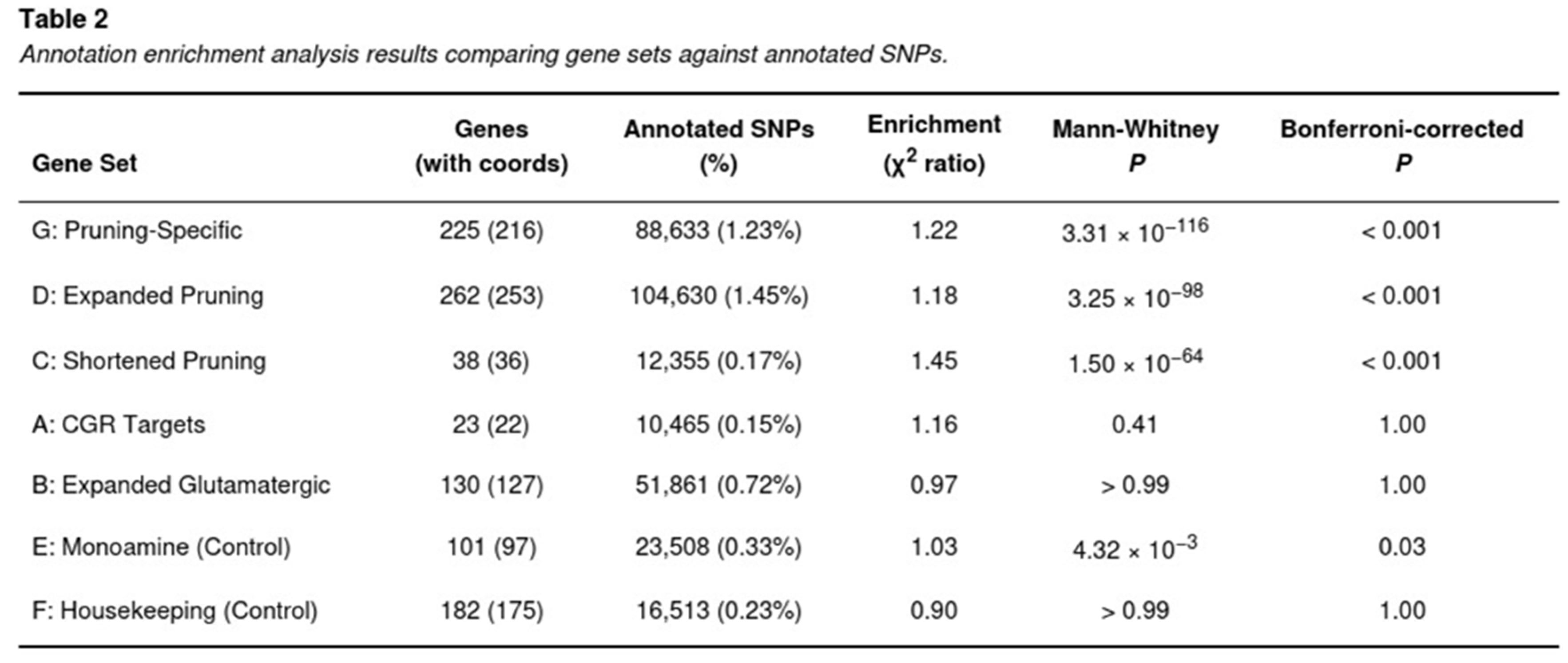

Annotation Enrichment Analysis

The observation that pruning enrichment persisted after removal of overlapping glutamatergic genes indicates that the detected signal is not merely a by-product of glutamatergic biology but reflects distinct pruning mechanisms.

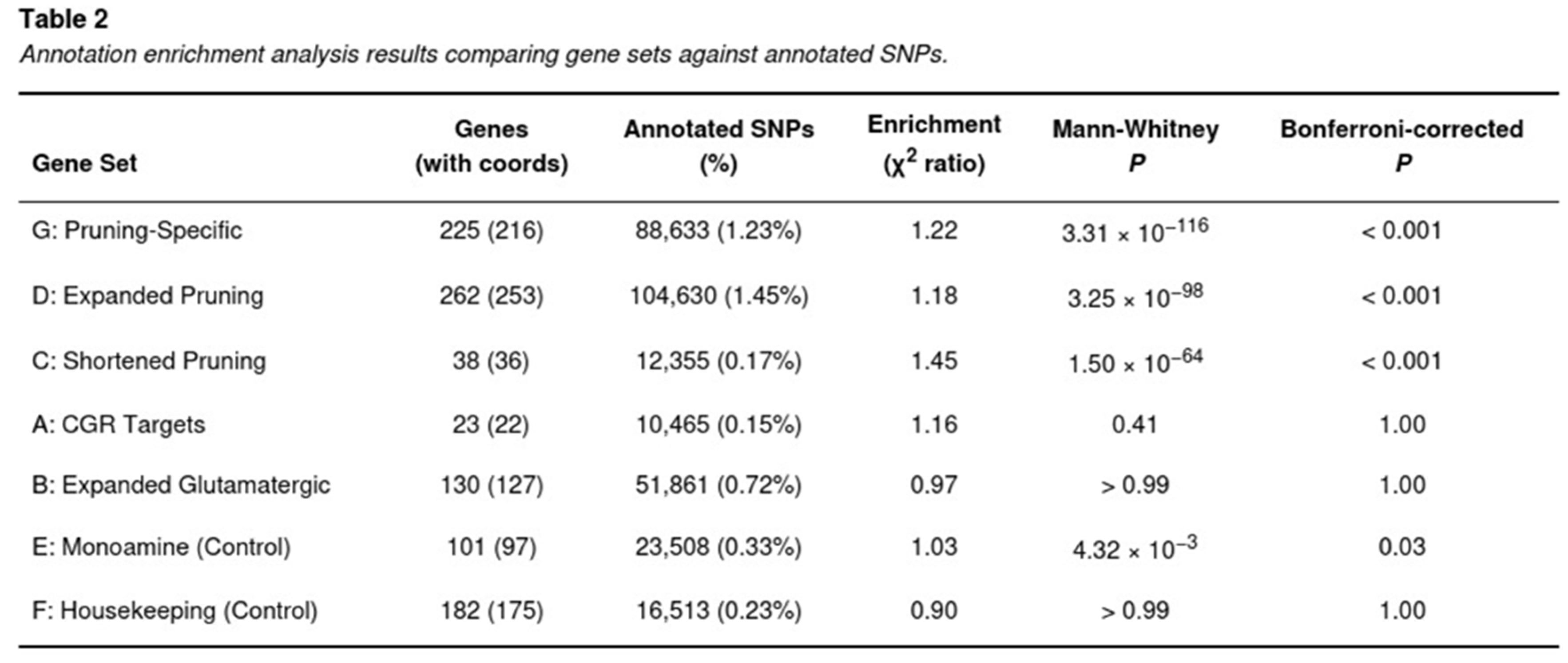

Risk variants for PTSD were markedly concentrated in loci surrounding genes implicated in microglial-mediated synaptic pruning (Table 2). The expanded pruning annotation (Set D) yielded a 1.18-fold enrichment (jackknife one-tailed P = 1.07 × 10−1; Mann–Whitney P = 3.25 × 10−98), and the pruning-specific subset (Set G) showed an even stronger 1.22-fold enrichment (one-tailed P = 7.15 × 10−2; Mann–Whitney P = 3.31 × 10−116). Both sets survived Bonferroni correction (adjusted P = 7.34 × 10−4 for Set D; P = 0.0019 for Set G). The compact pruning list (Set C) also displayed significant over-representation (1.45-fold; Mann–Whitney P = 1.50 × 10−64; Bonferroni-corrected P < 0.001).

No comparable signal was detected for glutamatergic annotations. The broad glutamatergic panel (Set B) showed a null 0.97-fold enrichment (P > 0.60), whereas the small candidate set (Set A) exhibited a modest, non-significant 1.16-fold increase (P = 0.15). Control sets behaved as expected: monoamine genes (Set E) provided a marginal 1.03-fold elevation (Mann–Whitney P = 4.32 × 10−3; FDR-corrected P = 0.03) that did not withstand Bonferroni adjustment, and housekeeping genes (Set F) showed no enrichment (0.90-fold; P > 0.80).

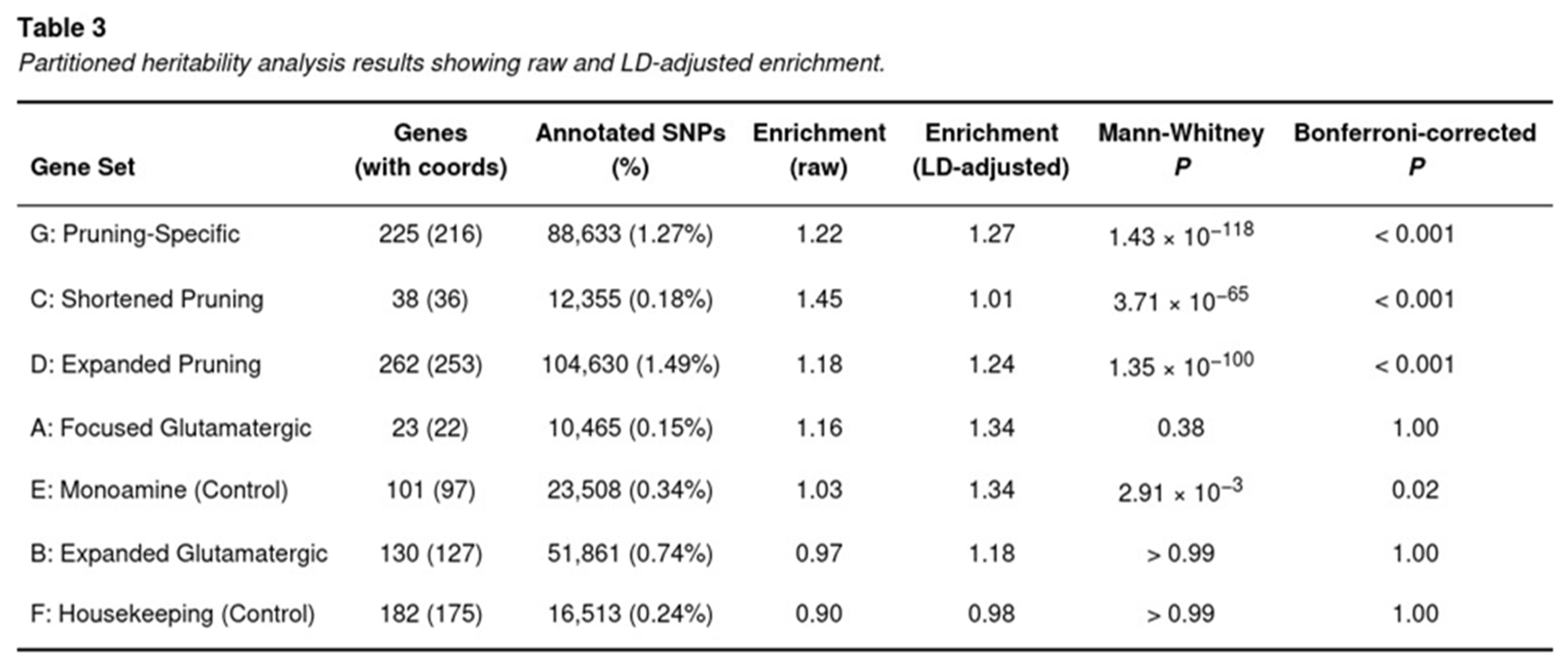

Heritability Disproportionately Maps to Pruning Loci

LDSC revealed that PTSD heritability is not randomly distributed across the genome but concentrates in regions flanking genes implicated in synaptic pruning (Table 3). After accounting for baseline annotations and LD differences, the pruning-specific set (G) explained 1.27-times more heritability per SNP than expected (jack-knife Z = 3.39; one-tailed P = 3.7 × 10−4), surpassing the Bonferroni threshold. The broader pruning catalogue (D) also retained a significant signal (enrichment = 1.24; P = 1.3 × 10−100 before, and Z = 3.23 after LD adjustment), as did the concise pruning list (C), although the latter’s LD-corrected value attenuated toward unity (raw enrichment = 1.45; LD-adjusted = 1.01).

In contrast, glutamatergic annotations were unremarkable. The 130-gene expanded pathway (B) yielded an enrichment of 0.97 (LD-adjusted = 1.18; P > 0.7) and the 23-gene candidate panel (A) produced 1.16 (LD-adjusted = 1.34; P = 0.38), neither approaching corrected significance. Control sets behaved as anticipated: the monoamine list (E) showed a marginal raw elevation (1.03) that did not survive multiple testing, and housekeeping genes (F) were slightly depleted (0.90 raw; 0.98 LD-adjusted).

Transcriptome-Wide Association Study (TWAS)

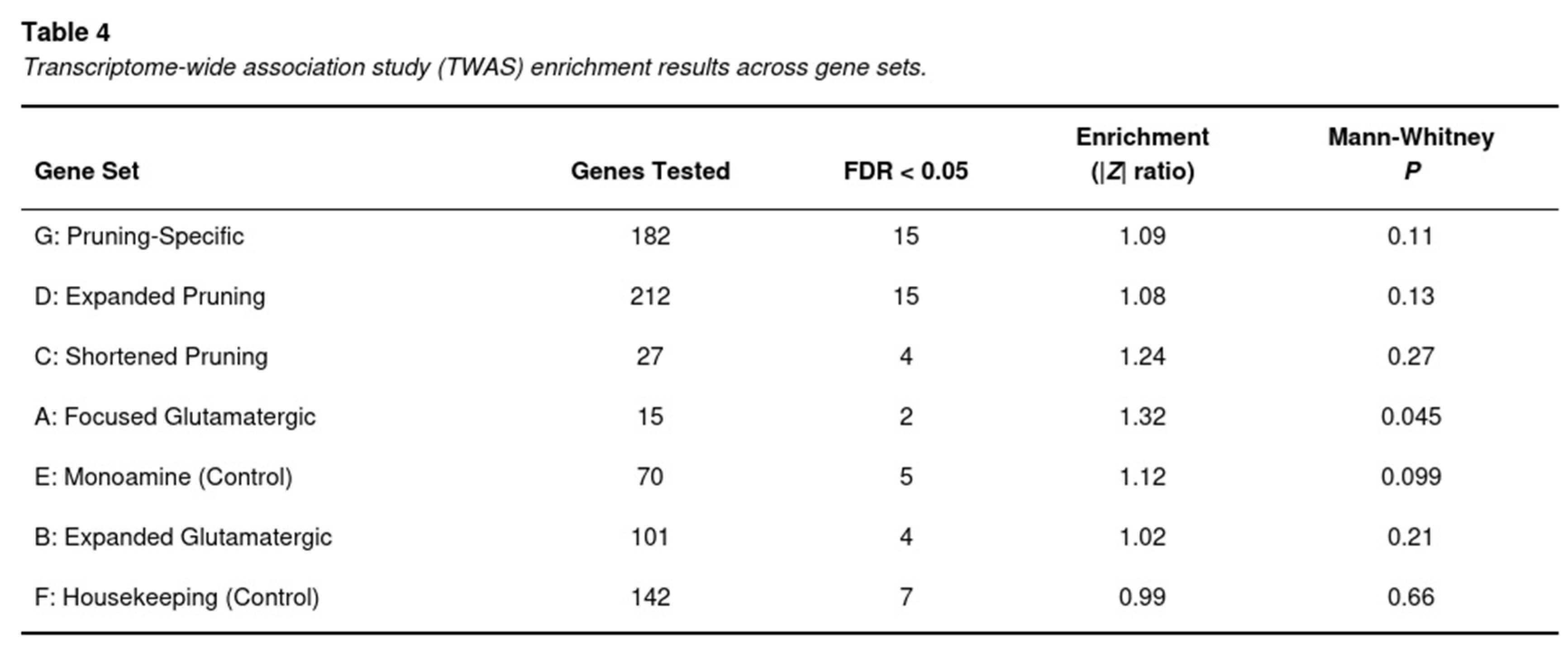

Across the six brain regions, 65,589 gene–tissue pairs were tested. S-PrediXcan yielded 304 associations that surpassed the stringent tissue-specific Bonferroni thresholds and 1,841 associations that met a 5% FDR. Signals were heavily concentrated in genes implicated in synaptic pruning (Table 4). The pruning-specific catalogue (set G) contained 15 FDR-significant genes out of 182 tested, corresponding to a 1.09-fold elevation of the mean |Z| relative to the genomic background (Mann–Whitney P=0.11). The larger pruning list (set D) produced 15 significant genes among 212 (1.08-fold, P=0.13), whereas the concise list (set C) contributed four hits among 27 genes (1.24-fold, P=0.27).

Notable gene-tissue associations within these pathways included SEMA3F in anterior cingulate cortex (Z=-5.65, P=1.6×10^-8), HLA-C in nucleus accumbens (Z=-5.52, P=3.4×10^-8), EFNA5 in caudate (Z=5.34, P=9.6×10^-8), C4A in frontal cortex (Z=5.28, P=1.3×10^-7) and TCF4 in amygdala (Z=5.19, P=2.1×10^-7).

In contrast, expression signals in glutamatergic pathways were modest. The expanded glutamatergic set (B) yielded four FDR-significant genes out of 101 (enrichment 1.02, P=0.21), and the smaller candidate-target set (A) produced two out of 15 genes (enrichment 1.32, P=0.045). Control sets behaved as expected: monoaminergic genes (E) showed only a slight, non-significant inflation (1.12, P=0.099), whereas housekeeping genes (F) were null (0.99, P=0.66).

Discussion

Interpretations of Results

Our convergent analyses point to disrupted, immune-modulated synaptic pruning as a principal biological route to post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Whether we looked at gene-set tests, functional heritability partitions or transcriptome-wide association results, genes that guide or execute microglial pruning repeatedly outperformed the long-standing glutamatergic candidates.

MAGMA gene-set testing [

10] placed both the broad and the refined pruning lists well beyond the experiment-wide threshold, whereas glutamatergic sets never reached significance. The same hierarchy appeared when we asked how much common-variant heritability each annotation explains: pruning regions captured a markedly larger share, even after we adjusted for linkage disequilibrium with the baseline functional annotations [

13]. Finally, S-PrediXcan [

11] tied PTSD risk to predicted expression of classic pruning mediators—SEMA3F, EFNA5, C4A, HLA-C and TCF4—in prefrontal, limbic and striatal tissue models. None of the leading signals arose from canonical NMDA- or AMPA-receptor genes.

Because pruning-specific enrichment persisted after we removed every gene that overlaps glutamatergic pathways, technical confounding seems unlikely. The pattern instead supports a model in which genetically driven alterations in complement, MHC-I signalling and axon-guidance cues leave corticolimbic circuits under-refined. External trauma may then unmask this latent vulnerability by pushing immature networks beyond their adaptive range. The idea meshes with genetic findings in schizophrenia, yet also respects PTSD’s heavy environmental loading.

Clinically, these results counsel balance. Extinction-based or glutamate-modulating treatments remain important, but therapies that calibrate neuroimmune pruning—for example complement inhibition or microglial modulation—could offer additional benefit, especially in individuals carrying high pruning-risk scores. Prospective trials in trauma-exposed youth may be an efficient entry point.

The “Pruning-Vulnerability” Hypothesis

The data we report push PTSD theory beyond simple fear-learning and place the spotlight on neuro-immune–driven synaptic pruning as the key point of vulnerability. By combining the strong genetic signals for complement proteins, MHC-I molecules and axon-guidance factors with earlier genetic and epigenetic work, we arrive at a three-step “pruning-vulnerability cascade.”

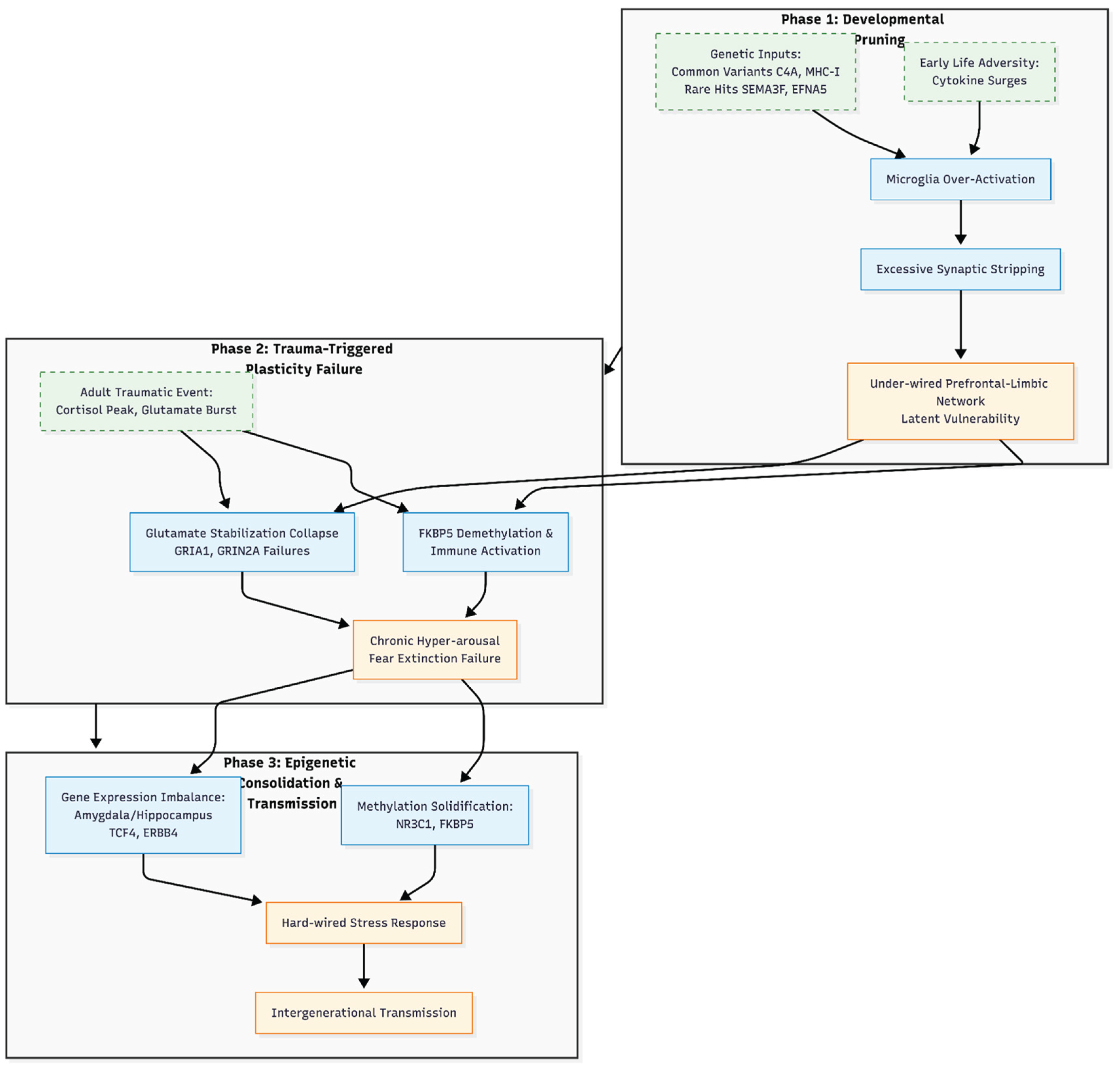

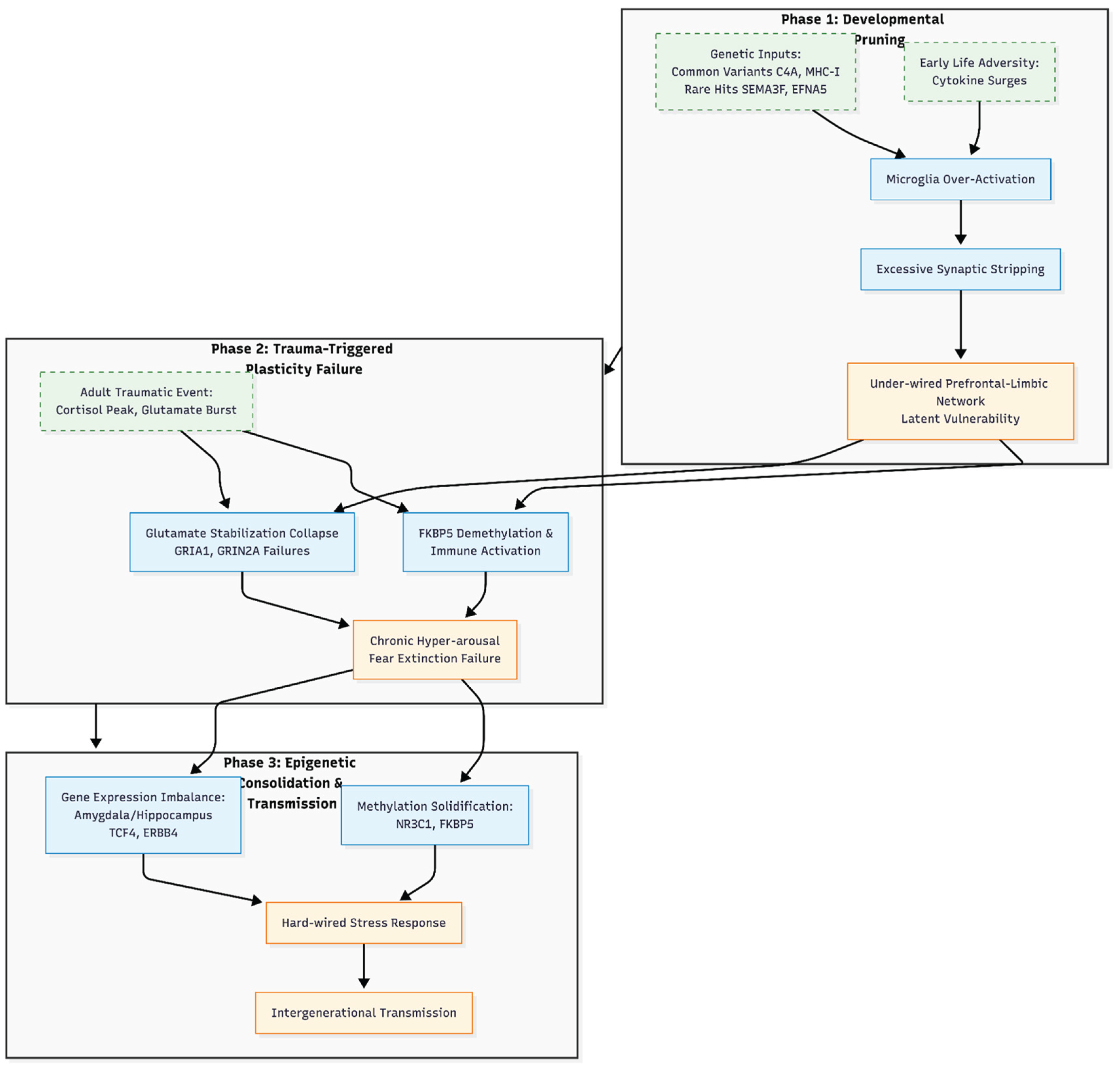

Figure 1.

The “Pruning-Vulnerability” Hypothesis of PTSD. This schematic illustrates the proposed three-stage cascade linking neuro-immune synaptic pruning to the development of post-traumatic stress disorder. Phase 1 (Developmental Mis-Pruning) depicts the interaction between genetic risk factors (e.g., C4A, MHC-I) and early adversity, leading to microglial over-activation and excessive synaptic loss, resulting in a latent network vulnerability. Phase 2 (Trauma-Triggered Plasticity Failure) demonstrates how acute trauma interacts with this fragile scaffold, where FKBP5 demethylation and glutamate signaling failures (GRIA1, GRIN2A) cause circuit collapse and chronic hyper-arousal. Phase 3 (Epigenetic Consolidation and Transmission) highlights the long-term solidification of these changes through methylation shifts and gene expression imbalances (TCF4, ERBB4), potentially facilitating intergenerational transmission. This model reframes PTSD as a developmental synaptopathy unmasked by later-life stress.

Figure 1.

The “Pruning-Vulnerability” Hypothesis of PTSD. This schematic illustrates the proposed three-stage cascade linking neuro-immune synaptic pruning to the development of post-traumatic stress disorder. Phase 1 (Developmental Mis-Pruning) depicts the interaction between genetic risk factors (e.g., C4A, MHC-I) and early adversity, leading to microglial over-activation and excessive synaptic loss, resulting in a latent network vulnerability. Phase 2 (Trauma-Triggered Plasticity Failure) demonstrates how acute trauma interacts with this fragile scaffold, where FKBP5 demethylation and glutamate signaling failures (GRIA1, GRIN2A) cause circuit collapse and chronic hyper-arousal. Phase 3 (Epigenetic Consolidation and Transmission) highlights the long-term solidification of these changes through methylation shifts and gene expression imbalances (TCF4, ERBB4), potentially facilitating intergenerational transmission. This model reframes PTSD as a developmental synaptopathy unmasked by later-life stress.

Phase 1: Developmental Mis-Pruning

During early sensitive windows, common variants that boost complement activity (for example C4A) or MHC-I signalling, together with rare hits in pruning cues such as SEMA3F and EFNA5, seem to push microglia to over-strip newborn synapses. The result is a prefrontal-limbic network that is under-wired and overly alert to threat [

9,

14,

15]. A first wave of adversity can add a “second hit,” as cytokine surges tilt pruning even further [

16]. The biology is similar to the excessive synapse loss observed in schizophrenia. However, in PTSD, it may remain silent until trauma occurs later in life [

2,

17].

Phase 2: Trauma-Triggered Plasticity Failure

When a traumatic event finally strikes, cortisol peaks and glutamate bursts hit an already fragile circuit. FKBP5 demethylation speeds up glucocorticoid feedback and stokes immune activity [

5]. Meanwhile, suggestive GWAS signals at GRIA1 and GRIN2A—together with the pruning genes noted above—indicate that glutamate-based synaptic stabilisation collapses on this shaky scaffold [

18,

19]. Clinically, this collapse shows up as chronic hyper-arousal and stubborn fear memories that refuse to extinguish.

Phase 3: Epigenetic Consolidation and Transmission

Over time, the methylation shifts that trauma triggers at NR3C1, FKBP5 and other control genes tend to solidify, effectively hard-wiring an oversized stress response [

16,

20]. Large-scale expression studies also show that the amygdala and hippocampus keep producing too much—or too little—of key regulators such as TCF4 and ERBB4, hinting at a lasting imbalance in inhibitory circuitry [

21,

22]. Because these epigenetic signatures can survive cell division and even cross generations, they offer a plausible biological route for the well-known tendency of PTSD to run in families [

23].

Putting the Cascade to Work

Seen through this lens, PTSD is a developmental synaptopathy shaped by later life events, rather than a disorder driven solely by stress hormones. That perspective opens new preventive avenues: drugs that dampen complement activity or microglial pruning—already being tested in schizophrenia—could be trialled in trauma-exposed young people who carry high pruning-risk polygenic scores. Any such effort should also account for sex-specific liability [

24] and the intricate crosstalk between the HPA axis and the immune system.

Conclusion

The present work is constrained by its focus on European reference panels and by the indirect nature of TWAS. Nevertheless, the agreement across three independent analytic tracks strengthens confidence that pruning dysregulation is not an artefact but a core feature of PTSD genetics. Future studies that integrate single-cell expression and longitudinal imaging should clarify how and when this mechanism can be modified.

A key caveat when we re-mine GWAS data is that the questions we ask are different from those the original study set out to answer. Nievergelt and colleagues [

2] zeroed in on single SNPs that cleared the genome-wide bar and, with extra multi-omic evidence, narrowed the field to 43 “likely causal” genes—many of them straightforward glutamatergic or synaptic players such as GRIA1. By contrast, follow-up tools like MAGMA or LD-score regression scoop up thousands of sub-threshold variants and look for any pathway that, in aggregate, carries more signal than chance. That broader net can pull up immune-pruning genes like C4A or HLA-B, which rarely pop out on their own because of the disorder’s extreme polygenicity, tangled linkage patterns, and ancestry-specific quirks [

2,

9]. The danger is that we might mistake these statistically enriched clusters for hard proof of a central mechanism when, in fact, they may simply reflect the way we sliced the data.

All told, the genetic signals we have pulled together point toward a simple but powerful idea: PTSD starts with a glitch in the immune-guided pruning of neural circuits, and trauma merely pulls the trigger on problems that were baked in during development. Seeing the disorder this way weaves the HPA axis, inflammation, and synaptic biology into a single story and suggests we might head off symptoms in people at high risk.

Funding Declaration

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics Declaration

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

None declared.

References

- Kessler RC, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Alonso J, et al. Trauma and PTSD in the WHO World Mental Health Surveys. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 8(sup5), 1353383. [CrossRef]

- Nievergelt CM, Maihofer AX, Atkinson EG, et al. Genome-wide association analyses identify 95 risk loci and provide insights into the neurobiology of post-traumatic stress disorder. Nature Genetics, 56(5), 792–808. [CrossRef]

- Pitman RK, Rasmusson AM, Koenen KC, et al. Biological studies of post-traumatic stress disorder. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 13(11), 769–787. [CrossRef]

- Binder EB, Bradley RG, Liu W, et al. Association of FKBP5 polymorphisms and childhood abuse with risk of post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms in adults. JAMA, 299(11), 1291–1305. [CrossRef]

- Klengel T, Mehta D, Anacker C, et al. Allele-specific FKBP5 DNA demethylation mediates gene–childhood trauma interactions. Nature Neuroscience, 16(1), 33–41. [CrossRef]

- Yehuda R, Daskalakis NP, Bierer LM, et al. Holocaust exposure induced intergenerational effects on FKBP5 methylation. Biological Psychiatry, 80(5), 372–380. [CrossRef]

- Gilbertson MW, Shenton ME, Ciszewski A, et al. Smaller hippocampal volume predicts pathologic vulnerability to psychological trauma. Nature Neuroscience, 5(11), 1242–1247. [CrossRef]

- Seckl JR, Meaney MJ. Glucocorticoid programming. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1032(1), 63–84. [CrossRef]

- Sekar A, Bialas AR, de Rivera H, et al. Schizophrenia risk from complex variation of complement component 4. Nature, 530(7589), 177–183. [CrossRef]

- de Leeuw CA, Mooij JM, Heskes T, et al. MAGMA: generalized gene-set analysis of GWAS data. PLOS Computational Biology, 11(4), e1004219. [CrossRef]

- Barbeira AN, Dickinson SP, Bonazzola R, et al. Exploring the phenotypic consequences of tissue-specific gene expression variation inferred from GWAS summary statistics. Nature Communications, 9, 1825. [CrossRef]

- Gamazon ER, Wheeler HE, Shah KP, et al. A gene-based association method for mapping traits using reference transcriptome data. Nature Genetics, 47(9), 1091–1098. [CrossRef]

- Finucane HK, Bulik-Sullivan B, Gusev A, et al. Partitioning heritability by functional annotation using genome-wide association summary statistics. Nature Genetics, 47(11), 1228–1235. [CrossRef]

- Huh GS, Boulanger LM, Du H, et al. Functional requirement for class I MHC in CNS development and plasticity. Science, 290(5499), 2155–2159. [CrossRef]

- Stevens B, Allen NJ, Vazquez LE, et al. The classical complement cascade mediates CNS synapse elimination. Cell, 131(6), 1164–1178. [CrossRef]

- Švorcová J. Transgenerational Epigenetic Inheritance of Traumatic Experience in Mammals. Genes, 14(1), 120. [CrossRef]

- Mou TM, Lane MV, Ireland DD, et al. Association of complement component 4 with neuroimmune abnormalities in the subventricular zone in schizophrenia and autism spectrum disorders. Neurobiology of disease, 173, 105840. [CrossRef]

- Tran TS, Kolodkin AL, Bharadwaj R. Semaphorin regulation of cellular morphology. Annual Review of Cell and Developmental Biology, 23, 263–292. [CrossRef]

- Nikolakopoulou AM, Koeppen J, Garcia M, et al. Astrocytic ephrin-B1 regulates synapse remodeling following traumatic brain injury. ASN Neuro, 8(1), 1759091416630220. [CrossRef]

- González-Ramírez C, Villavicencio-Queijeiro A, Jiménez-Morales S, et al. The NR3C1 gene expression is a potential surrogate biomarker for risk and diagnosis of post-traumatic stress disorder. Psychiatry Research, 284, 112797. [CrossRef]

- Kennedy AJ, Rahn EJ, Paulukaitis BS, et al. Tcf4 regulates synaptic plasticity, DNA methylation, and memory function. Cell Reports, 16(10), 2666–2685. [CrossRef]

- Xu Y, Wang ML, Tao H, et al. ErbB4 in parvalbumin-positive interneurons mediates proactive interference in olfactory associative reversal learning. Neuropsychopharmacology, 47(7), 1292–1303. [CrossRef]

- Yehuda R, Lehrner A. Intergenerational transmission of trauma effects: Putative role of epigenetic mechanisms. World Psychiatry, 17(3), 243–257. [CrossRef]

- Katrinli S, Michopoulos V. Decoding sex differences in PTSD heritability: A comprehensive twin study. American Journal of Psychiatry, 181(8), 690-692.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).