Submitted:

01 January 2026

Posted:

06 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

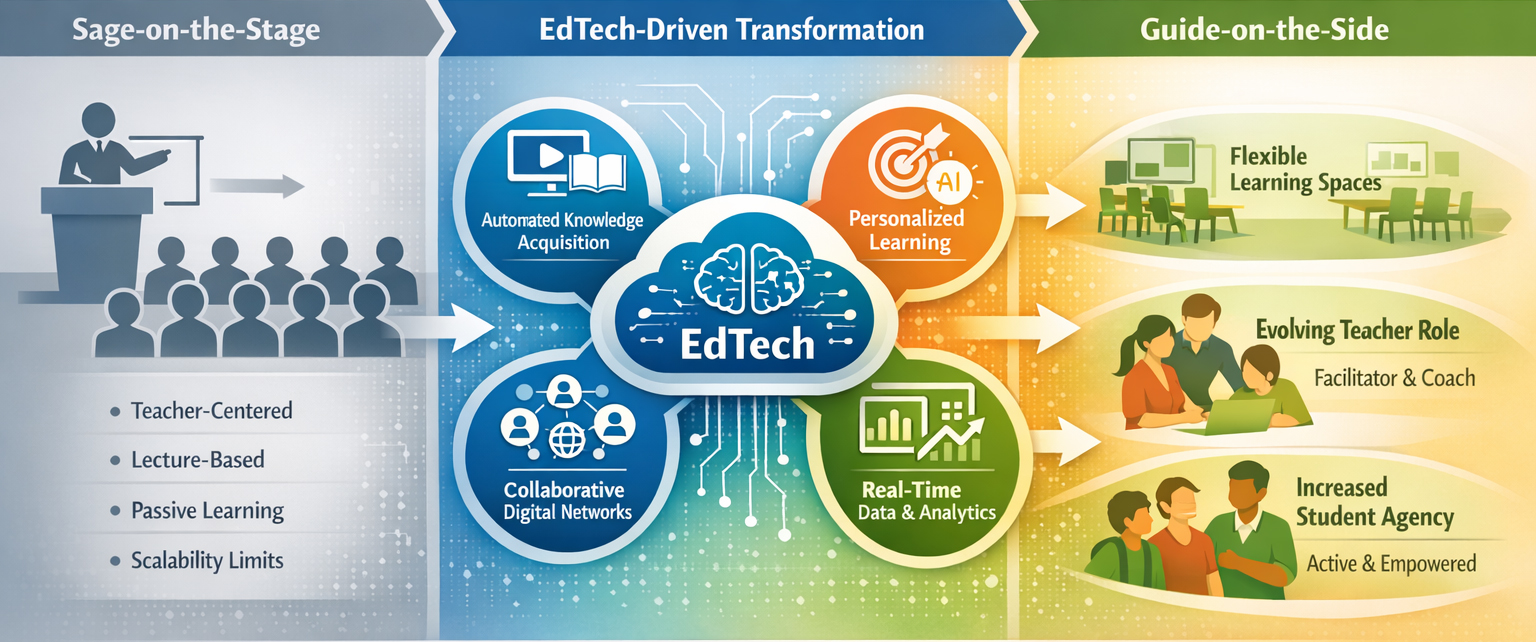

1.1. The Enduring Reign of the “Sage-on-the-Stage”: More Than Tradition

- Assessment Regimes: Standardized, high-stakes testing prioritizes the recall of discrete facts over critical thinking, creativity, or collaboration. Teachers are often pressured to “teach to the test,” a practice that inherently favors broad, teacher-directed content coverage over deep, student-driven inquiry.

- Policy and Curriculum Mandates: Rigid, content-heavy national curricula leave little room for the flexibility and time required for facilitative, project-based learning. Policy frameworks often measure educational success through easily quantifiable metrics aligned with the “sage” model’s outputs.

- Teacher Preparation Programs: Many pre-service training programs still emphasize content mastery and classroom management for delivery, rather than the skills of facilitation, learning design, and data-informed mentoring required for a “guide” role.

- Cultural and Parental Expectations: Societal perceptions of teaching and learning are often shaped by personal experience, leading to expectations that a “real” teacher is one who stands at the front, clearly transmitting knowledge. Deviations from this archetype can be met with skepticism.

1.2. The “Guide-on-the-Side” Imperative: A Response to 21st-Century Demands

1.3. EdTech as the Enabling Catalyst: A Solution to the Scalability Impasse

- Reallocating Teacher Time: Automating direct instruction (e.g., through flipped classroom tools) reclaims in-class hours for active, human-centric facilitation.

- Enabling Differentiation: Adaptive software can personalize practice and content pathways at a scale impossible for one teacher, making true differentiation operational.

- Facilitating New Interactions: Digital platforms expand opportunities for collaboration and creation beyond physical and temporal classroom limits.

- Informing Practice: Learning analytics provide real-time data, replacing intuition with insight and allowing for precise, timely intervention.

2. Methodology

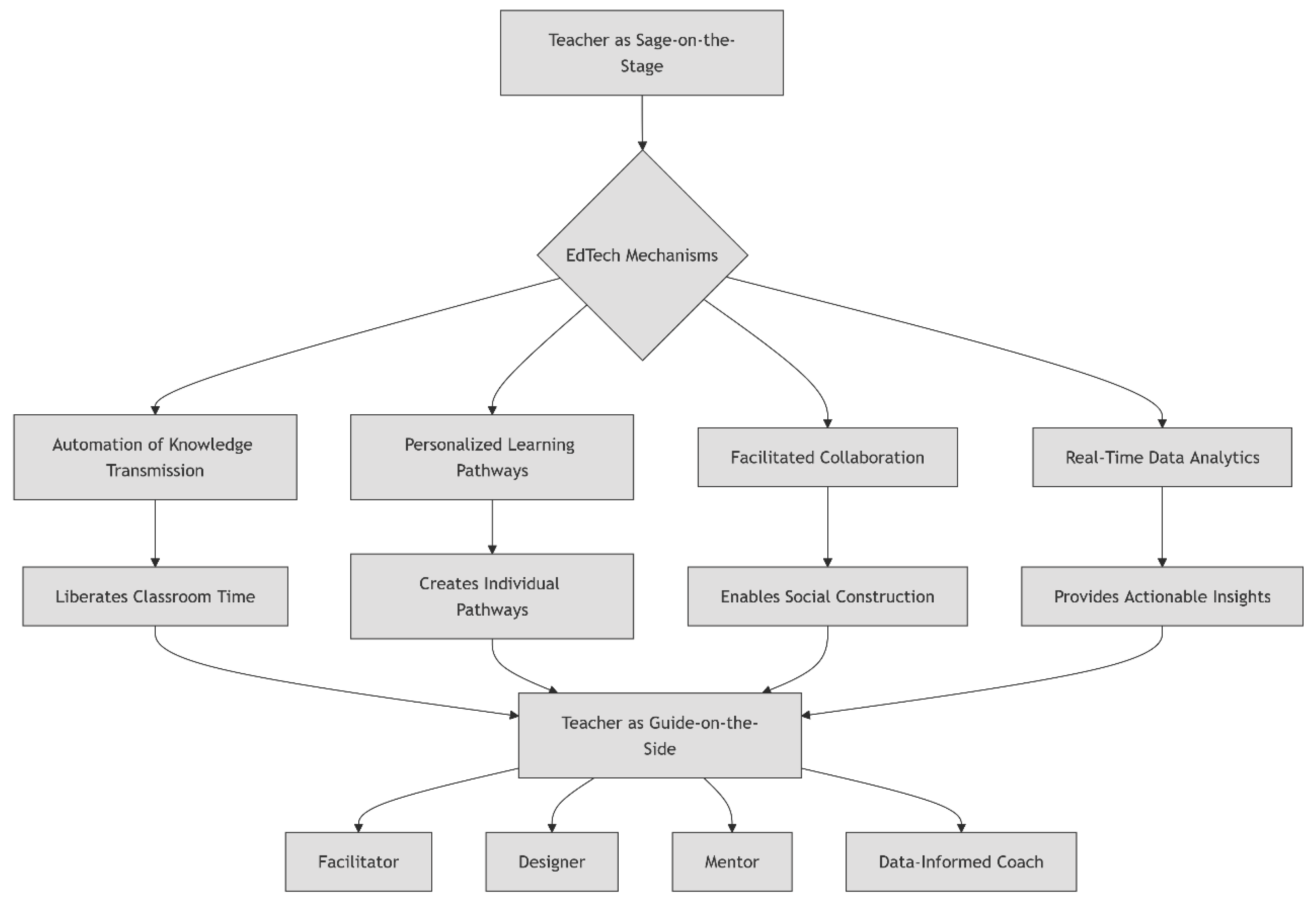

2.1. A Framework for Pedagogical Re-Engineering: Four Interlocking Mechanisms

2.2. The Four Mechanisms: Potential and Critical Limitations

- Risk of Depersonalization: A playlist of videos cannot replace the dynamic, responsive energy of a live explanation. Students may feel disconnected.

- Solution: Blend automated content with mandatory, low-stakes check-ins (e.g., quick polls, reflection posts) where teachers respond personally. Use class time explicitly for human connection and clarifying muddy points.

- Passive Consumption in New Format: Simply watching videos at home replicates passive learning outside school walls.

- Solution: Design interactive content with embedded questions (via Edpuzzle), and pair videos with guided notes or preparatory tasks that require active processing.

- Equity of Access: This model assumes all students have reliable devices and internet at home.

- Solution: Provide offline options (USB drives, printed transcripts), ensure school provides dedicated access time, and never penalize for lack of home connectivity.

- Algorithmic Bias & Opacity: Algorithms may perpetuate biases present in their training data and their logic can be a "black box," making it hard to understand why a student is routed a certain way.

- Solution: Teachers must maintain "pedagogical sovereignty" using algorithmic suggestions as one data point, not a prescription. Demand transparency from vendors on how algorithms work.

- Data Privacy & Commercialization: Extensive data collection on minors raises serious ethical questions about ownership, security, and potential commercial use.

- Solution: Schools must adopt strict data governance policies, prefer tools with strong privacy commitments (e.g., compliant with FERPA/COPPA), and educate students on digital footprints.

- The "Personalization Paradox": Hyper-individualized pathways can reduce valuable peer-to-peer learning and the shared common knowledge essential for classroom community.

- Solution: Deliberately design collaborative projects and whole-class discussions that integrate and build upon personalized learning experiences.

- Exacerbating the Digital Divide: Collaboration assumes all students have equal facility with the tools and space to participate online, which is often untrue.

- Solution: Scaffold digital literacy explicitly, use intuitive platforms, and ensure core collaborative work happens during supported school time.

- Superficial Collaboration: Without careful design, digital collaboration can devolve into divided work or dominated by a few voices.

- Solution: Use protocols, assign rotating roles (e.g., facilitator, synthesizer, checker), and assess both the final product and the collaborative process.

- Diminished Interpersonal Skills: Over-reliance on digital communication may hinder the development of nuanced face-to-face interaction skills.

- Solution: Purposefully balance screen-based collaboration with in-person, unmediated group work and discussion.

- Surveillance & Performance Culture: Constant tracking can create an atmosphere of surveillance, increasing student anxiety and reducing intellectual risk-taking.

- Solution: Be transparent with students about what data is collected and why. Use data primarily for formative support, not punitive control. Involve students in reviewing their own data for self-reflection.

- Data Overload & Misinterpretation: Teachers can be overwhelmed by data streams, leading to paralysis or drawing incorrect conclusions from metrics.

- Solution: Focus on a few key metrics aligned to learning goals. Provide professional development on data literacy how to interpret, question, and act on data.

- Reductionism: Data dashboards often quantify what is easily measurable (clicks, quiz scores), potentially overlooking crucial but hard-to-measure outcomes like creativity, perseverance, or curiosity.

- Solution: Insist on a balanced assessment ecosystem. Prioritize human observation, student portfolios, and qualitative feedback alongside quantitative analytics.

2.3. Cantering Teacher Agency: From Passive Adopter to Pedagogical Designer

- Choice & Customization: Teachers should have autonomy to select, adapt, and even opt-out of technologies based on their professional judgment and student needs.

- Design Leadership: Professional development must focus on learning design how to craft experiences using technology to achieve pedagogical goals not just button-clicking.

- Critical Evaluation: Teachers must be equipped to critically evaluate EdTech tools for pedagogical soundness, equity, and data ethics, becoming informed gatekeepers for their classrooms.

3. Results

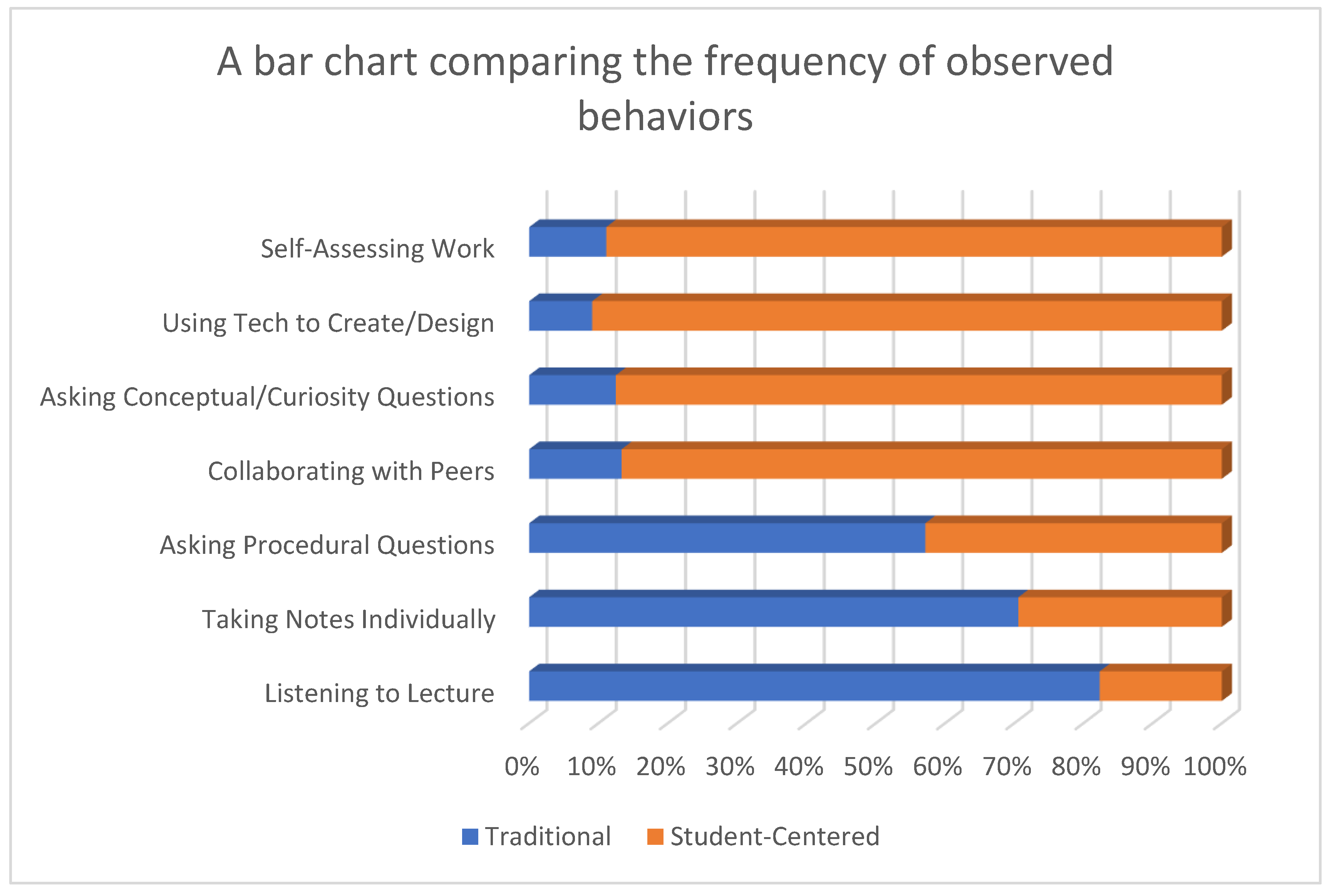

3.1. The Changing Classroom: Documented Shifts and Emerging Contradictions

3.1.1. Physical and Temporal Reconfiguration

- Increased Teacher Workload (Initial Phase): Studies by Trust & Whalen (2021) note that the transition to a flipped or tech-heavy model initially significantly increases teacher workload due to the creation and curation of digital resources, a factor often omitted from promotional literature. This "implementation dip" can lead to burnout if not supported.

- Screen Fatigue and Cognitive Overload: A growing body of research highlights digital eye strain, increased distractibility, and mental fatigue associated with prolonged screen-based learning. As one high school student shared in a 2023 study: "After a day of videos and online quizzes, my head aches. I miss just talking to a teacher and a whiteboard sometimes" (Chu & Xie, 2023).

- Erosion of Unstructured Interaction: The efficiency of digital collaboration tools can inadvertently reduce spontaneous, face-to-face peer dialogue and the nuanced, off-task social learning crucial for development.

| Context / Outcome | High-Income, Well-Resourced School | Low-Income, Under-Resourced School | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Access to Devices & Connectivity | 1:1 programs, high-speed school & home internet. | Shared devices, unreliable school bandwidth, limited/no home access. | The foundational prerequisite for any shift is inequitably distributed. |

| Teacher Capacity for Integration | Dedicated instructional tech coaches, regular paid PD time. | Limited, one-off PD; teacher-as-technician model prevails. | Support structures determine if teachers become designers or just operators. |

| Student Experience of "Personalization" | "It feels like it’s tailored for me. I can go ahead or get help without holding anyone back." – Student quote (Pane, 2024). | "The computer just gives me easier problems when I fail. It doesn’t explain why I’m wrong like a teacher could." – Student quote (RAND Equity Study, 2023). | Personalization without human mediation can feel isolating and mechanistic. |

| Measured Impact on Standardized Scores | Modest gains (5-8%) in math & science; significant gains in student engagement metrics. | No statistically significant gains; sometimes a decline due to focus on tech acclimation over core instruction. | Benefits often accrue where baseline resources are already strong, potentially widening gaps. |

| Primary Unintended Consequence | Tech dependence, reduced stamina for deep reading, social interaction mediated through screens. | Exacerbation of digital divide, instruction time lost to tech troubleshooting, increased frustration. | Context shapes the nature of the downsides. |

3.2. The Evolution of Teacher Responsibilities: Upskilling and Strain

- The Data Deluge: While data can inform practice, teachers report feeling overwhelmed by the constant stream of metrics from multiple platforms. A middle school teacher noted in an interview: "I have a dashboard for reading, another for math, alerts from the LMS... It’s paralyzing. I spend more time interpreting coloured graphs than looking at my students' faces" (Educator Voice Project, 2024).

- Role Ambiguity and Stress: The shift from content expert to facilitator/designer/data analyst creates role ambiguity. A 2023 study by the National Education Association found that teachers in schools undergoing rapid tech integration reported higher levels of job-related stress correlated with constantly changing expectations and the pressure to master new tools while maintaining old accountability measures.

- The Risk of De-Skilling: In some implementations, teachers are reduced to "monitors" while algorithms drive instruction. This contradicts the vision of the teacher as a pedagogical expert and can lead to professional dissatisfaction.

| Variable | Negative Evidence | Positive Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Student Engagement | Screen Fatigue, Distraction | Gamification, Choice, Agency |

| Academic Outcomes | No Sig. Gain (Mixed Studies) | Modest Gains in Specific Contexts |

| Teacher Workload | Initial Major Increase | Long-term Reallocation (If Supported) |

| Equity | Widens Existing Gaps | Can Personalize Support (If Access Universal) |

| 21st-Century Skills | Superficial Collaboration | Authentic Creation & Digital Literacy |

3.3. Student Agency and Empowerment: A Nuanced Picture

- Illusion of Choice: Personalization algorithms can create a "choice within a cage," where students follow a pre-determined digital pathway, mistaking menu navigation for genuine intellectual autonomy.

- Performance Tracking Anxiety: The constant feedback loop of digital platforms can turn learning into a performance metric, increasing anxiety for some students. As one researcher cautions, "When every click is tracked, learning can become a act of compliance, not curiosity" (Holstein et al., 2023).

- Dependence on the Tool: Over-reliance on adaptive software for foundational skill practice can weaken students' metacognitive skills and perseverance. They may learn to guess for the right algorithmically accepted answer rather than develop deep conceptual understanding.

4. Discussion

4.1. Synthesis: The Double-Edged Sword of the EdTech Revolution

4.2. Re-Framing the Core Challenge: Equity as the Imperative, Not an Add-On

- Equity of Experience: Access to a device does not equal access to high-quality, teacher-facilitated, tech-enabled learning. Students in under-resourced schools often encounter technology used for rote drill and test prep ("substitution" on the SAMR model), while their affluent peers use it for creation, collaboration, and research ("redefinition").

- Algorithmic Equity: Personalized learning tools must be scrutinized for bias. Do they recognize diverse linguistic patterns and cultural contexts, or do they penalize them? Who defines the "correct" learning pathway?

4.3. A Framework for Responsible Implementation: The Ethical EdTech Integration Checklist

- 5.

- PEDAGOGICAL PURPOSE FIRST: Why this tool? The primary question must be: "What learning problem does this solve that is difficult or impossible without it?" Use frameworks like TPACK (Koehler & Mishra, 2024) to integrate Technology, Pedagogy, and Content Knowledge.

- 6.

- EQUITY & ACCESS ENSURED: For whom? Have we audited for device/internet access, digital literacy, and language support? Does use of this tool during class time ensure all can participate fully, regardless of home resources?

- 7.

- TEACHER AGENCY & TRAINING PROVIDED: With whose expertise? Is professional development ongoing, job-embedded, and focused on learning design rather than button-pushing? Do teachers have the autonomy to adapt or reject tools that don't serve their students?

- 8.

- STUDENT DATA PROTECTED: At what cost? What data is collected, who owns it, and how is it secured? Are privacy policies transparent and compliant? Is student data ever sold or used for commercial profiling?

- 9.

- BALANCED SCREEN TIME & HUMAN CONNECTION: Toward what balance? Does the tool foster meaningful interaction (student-student, student-teacher), or isolation? Are there clear protocols for "unplugged" time, face-to-face discussion, and hands-on activity?

4.4. The Path to Sustainable Implementation: Moving Beyond the Pilot

- Funding Models: Move beyond one-time hardware grants. Sustainable models budget for refresh cycles for devices (every 3-5 years), ongoing software licenses, dedicated technical support staff, and most critically, permanent funding for instructional coaching roles. Consider public-private partnerships carefully, ensuring they do not cede curricular control or student data.

-

Ongoing Support, Not One-Off Training: Professional learning must be continuous and collaborative. This includes:

- ○

- Peer Learning Communities: Where teachers co-design lessons and troubleshoot challenges.

- ○

- Micro-Credentialing: Recognizing mastery in specific competencies like "Data-Informed Facilitation."

- ○

- Protected Planning Time: For teachers to design tech-integrated experiences.

- Community Engagement: Parents and guardians are key partners. Schools must proactively communicate the why behind the shift, offering workshops on new tools and platforms, and ensuring two-way dialogue about concerns related to screen time, data privacy, and homework expectations in a flipped model.

4.5. Reclaiming the "Guide": The Teacher as Learning Architect

- Designer: Curating digital and physical resources to construct rich, inquiry-based learning landscapes.

- Data Ethnographer: Interpreting analytics with a critical, contextual eye to understand the story behind the numbers.

- Facilitator of Culture: Nurturing a classroom community of trust, intellectual risk-taking, and collaborative problem-solving.

- Ethical Guardian: Safeguarding student well-being, privacy, and equity in the digital environment.

5. A Roadmap for Responsible Implementation

5.1. Phase 1: Readiness Assessment – Building on Solid Ground

-

Infrastructure Audit:

- ○

- Connectivity: Is school-wide broadband robust, reliable, and capable of supporting simultaneous use by all students and staff? What is the upload/download speeds?

- ○

- Hardware: What is the current state and age of devices? Is there a sustainable plan for 1:1 access, including take-home capabilities? Are there adequate charging and storage solutions?

- ○

- Technical Support: Is there sufficient on-site or rapidly available technical support to address daily issues without significant instructional downtime?

-

Human Capital & Readiness:

- ○

- Teacher Readiness: Conduct anonymous surveys and focus groups to gauge current digital proficiency, pedagogical beliefs, and readiness for change. Identify early adopters, cautious middle adopters, and resistors to tailor support.

- ○

- Leadership Alignment: Do administrators and department heads share a common vision for why this shift is necessary? Are they prepared to support teachers through the inevitable challenges of implementation?

- ○

- Student & Family Access: Survey families to understand home access to devices and reliable internet. This is not to penalize, but to plan for equitable participation (e.g., providing hotspots, offline materials, extended school access hours).

- Outcome: A clear, data-informed readiness report that identifies strengths, gaps, and non-negotiable prerequisites before moving forward. This phase may result in a necessary delay to secure foundational resources.

5.2. Phase 2: Pilot & Iterate – Learning Through Focused Action

-

Design the Pilot:

- ○

- Select a Volunteer Cohort: Recruit a small group of willing teachers from different subjects or grade levels. Include both tech-enthusiasts and respected skeptics.

- ○

- Define a Clear Scope: Pilot one specific pedagogical model (e.g., the flipped classroom) or a focused set of tools (e.g., a collaboration suite) aligned to a clear learning goal.

- ○

- Establish a Feedback Framework: Create structured mechanisms for continuous feedback: weekly teacher check-ins, student surveys, classroom observations focused on engagement and challenge points.

-

Embrace Iteration:

- ○

- Fail Fast, Learn Faster: Encourage pilot teachers to share what isn’t working openly and without blame. The pilot is a laboratory.

- ○

- Adapt Protocols: Based on feedback, adjust guidelines, workflows, and support structures in real-time. For example, you may find students need explicit training on how to watch an instructional video effectively before the flipped model can succeed.

- ○

- Document the Journey: Capture not just successes, but problems and solutions. This creates a valuable knowledge base and realistic expectations for scaling.

- Outcome: A refined, context-specific model of implementation, a group of teacher-leaders with practical experience, and evidence-based protocols ready for broader use.

5.3. Phase 3: Scale with Support – Growing the Ecosystem

-

Invest in Differentiated Professional Development:

- ○

- Move beyond one-size-fits-all workshops. Offer tiered support: foundational skills for beginners, advanced design studios for early adopters, and just-in-time coaching for all.

- ○

- Leverage pilot teachers as peer coaches and mentors, creating an internal community of practice.

- ○

- Focus PD on pedagogical design with technology, not just tool functionality.

-

Engage the Wider Community:

- ○

- Parents & Guardians: Host informational sessions to explain the why behind new learning models. Offer tutorials on new platforms and create clear channels for questions and concerns.

- ○

- Students: Involve student tech teams or ambassadors to provide peer support and feedback on tool usability and learning experience.

-

Align Policy and Practice:

- ○

- Revise school schedules to allow for collaborative teacher planning time.

- ○

- Adjust assessment and evaluation policies to value facilitation, student agency, and project-based outcomes alongside traditional measures.

- ○

- Ensure sustainable budget lines for ongoing software licenses, device refresh, and coaching positions not just initial hardware costs.

- Outcome: A growing percentage of classrooms effectively integrating technology, supported by a culture of collaboration, clear policies, and an engaged community.

5.4. Phase 4: Evaluate & Evolve – Fostering a Culture of Continuous Improvement

-

Multi-Dimensional Evaluation:

- ○

- Student Learning: Look beyond standardized test scores to metrics of engagement, self-efficacy, collaboration, and the quality of student work (portfolios, projects).

- ○

- Teacher Practice: Use walk-throughs and self-assessments aligned to the "Guide-on-the-Side" competencies (e.g., questioning, facilitation, data use).

- ○

- System Health: Monitor equity metrics are all student groups benefiting equally? Track teacher well-being and retention in pilot vs. non-pilot groups.

-

Use Data Responsibly:

- ○

- Analyse learning analytics and feedback data not for accountability judgments, but as a diagnostic tool for collective problem-solving.

- ○

- Hold regular "data reflection" meetings where teachers and leaders review trends and co-design interventions.

-

Plan for Evolution:

- ○

- Technology and pedagogy will continue to evolve. Establish a standing innovation committee tasked with periodically reviewing new tools and research and recommending the next small-scale pilots.

- ○

- Celebrate and share stories of impact not just quantitative gains, but qualitative narratives of student empowerment and teacher growth.

- Outcome: A resilient, adaptive learning organization that views the EdTech-enabled shift not as a finite initiative, but as a core dimension of its commitment to continuous growth and equitable, powerful learning for all.

6. Conclusion

6.1. The Silent Revolution: A Reality in Flux

6.2. The Path Forward: A Call to Action

- Start Small, Think Big: Begin with one tool aligned to a clear pedagogical goal perhaps using a platform like Flip to spark student voice through video reflection and master its integration. Do not attempt to overhaul everything at once.

- Join and Build Networks: Seek out professional learning networks (PLNs), both online (e.g., #EdTechChat) and in-person, to share resources, troubleshoot challenges, and co-design with peers.

- Assert Pedagogical Sovereignty: Remember that you are the expert in your classroom. Critically evaluate every tool. If an EdTech product does not serve your students' learning or well-being, you have the professional right and duty to adapt or reject it.

- Invest in People, Not Just Products: Allocate budgets to ongoing, job-embedded professional development and instructional coaching at parity with hardware expenditures. A device without a trained, supported teacher is a paperweight.

- Prioritize Equity Infrastructure: Ensure universal, reliable access by investing in robust school-wide broadband and sustainable 1:1 device programs with take-home guarantees. Make digital equity a key performance indicator.

- Reward Innovation, Not Just Compliance: Revise teacher evaluation frameworks to value facilitation, questioning, and the design of collaborative learning experiences as highly as classroom management and test score gains.

- Fund with Purpose: Direct public funding toward equity-focused EdTech initiatives that prioritize closing the digital divide in underserved communities. Support not just procurement, but the long-term costs of connectivity, support, and training.

- Modernize Assessment: Revise high-stakes assessment systems that currently reinforce the "sage" model. Develop and pilot new metrics that value critical thinking, collaboration, creativity, and student portfolios the very outcomes the "Guide-on-the-Side" model cultivates.

- Enact Strong Data Privacy Guards: Pass and enforce stringent regulations to protect student data from commercial exploitation, ensuring that learning analytics are used solely for educational benefit.

6.3. A New Vision: From Guide to Architect and Co-Learner

- The Learning Architect designs vibrant ecosystems of learning, blending digital and physical resources to construct experiences that provoke curiosity, challenge assumptions, and connect to the real world. This architect builds scaffolds, not cages; they create pathways with multiple entry points to honor diverse learners.

- The Co-Learner acknowledges that in a rapidly changing world, no one is the sole repository of knowledge. This teacher models curiosity, investigates alongside students, and leverages technology not just to teach, but to learn with and from their students about new tools, perspectives, and problems.

6.4. The Ultimate Goal: Rehumanizing Education

References

- Baker, R. S. (2024). Big data and education: 8th edition. Routledge. [CrossRef]

- Chen, B., & Zhang, L. (2023). From passive recipients to active creators: A post-pandemic review of student-centered learning. Journal of Educational Technology Research, 51(2), 145–162. [CrossRef]

- Chen, B., Wang, Y., & Wang, L. (2022). The effects of flipped classroom on learning achievement and learning motivation: A meta-analysis. Educational Technology Research and Development, 70(4), 1357–1384. [CrossRef]

- Chu, H. C., & Xie, H. (2023). Student well-being in digital learning environments: A mixed-methods study of screen fatigue and engagement. Computers in Human Behavior, 148, 107902. [CrossRef]

- Darling-Hammond, L. (2023). The flat world and education: How America's commitment to equity will determine our future (2nd ed.). Teachers College Press.

- Darling-Hammond, L., Flook, L., Schachner, A., & Wojcikiewicz, S. (2024). Educating for the future: The changing landscape of pedagogy and technology. Learning Policy Institute. https://learningpolicyinstitute.org/product/educating-future-report.

- Educator Voice Project. (2024). Annual report on teacher well-being and technology integration. National Board for Professional Teaching Standards.

- Ertmer, P. A., & Ottenbreit-Leftwich, A. T. (2024). Removing obstacles to the pedagogical changes required by Jonassen's vision of authentic technology-enabled learning. Educational Technology Research and Development, 72(1), 1–26. [CrossRef]

- Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the oppressed. Herder and Herder.

- Hodges, C., Moore, S., Lockee, B., Trust, T., & Bond, A. (2022). The difference between emergency remote teaching and online learning. Educause Review. https://er.educause.edu/articles/2022/3/the-difference-between-emergency-remote-teaching-and-online-learning.

- Holstein, K., McLaren, B. M., & Aleven, V. (2023). Student and teacher perspectives on learning analytics dashboards: A critical data literacy approach. Journal of Learning Analytics, 10(1), 1–26. [CrossRef]

- Ifenthaler, D., & Gibson, D. (2023). Adoption of learning analytics. In Adoption of data analytics in higher education learning and teaching (pp. 3–20). Springer. [CrossRef]

- International Society for Technology in Education. (2023). ISTE standards: For educators. https://www.iste.org/standards/iste-standards-for-teachers.

- Kessler, A., Meeter, M., & van der Schoot, M. (2023). The digital transformation of education: A systematic review of the literature. Computers & Education, 190, 104606. [CrossRef]

- King, A. (1993). From sage on the stage to guide on the side. College Teaching, 41(1), 30–35. [CrossRef]

- Koehler, M. J., & Mishra, P. (2024). What is technological pedagogical content knowledge (TPACK)? Contemporary Issues in Technology and Teacher Education, 24(1), 1–12. https://citejournal.org/volume-24/issue-1-24/general/what-is-technological-pedagogical-content-knowledge.

- National Education Association. (2023). Educator stress and technology integration: A national survey. NEA Research.

- Pane, J. F. (2024). The continued evolution of personalized learning: Evidence from a multi-year study. RAND Corporation. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA2794-1.html.

- Pew Research Center. (2021, August 19). Digital divide persists even as Americans with lower incomes make gains in tech adoption. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2021/08/19/digital-divide-persists-even-as-americans-with-lower-incomes-make-gains-in-tech-adoption/.

- RAND Corporation. (2023). Equity in adaptive learning: Student and teacher experiences in low-income schools (Research Brief RB-10221). https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_briefs/RB10221.html.

- Steelcase Education. (2022). Active learning spaces: The impact of classroom design on student engagement and performance. https://www.steelcase.com/research/articles/topics/active-learning/active-learning-spaces-impact-classroom-design/.

- Thomas, D., & Brown, J. S. (2021). A new culture of learning: Cultivating the imagination for a world of constant change. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform.

- Trust, T., & Whalen, J. (2021). Should teachers be trained in emergency remote teaching? Lessons learned from the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Technology and Teacher Education, 29(2), 189–217. https://www.learntechlib.org/primary/p/218722/.

- Trust, T., Carpenter, J. P., & Krutka, D. G. (2022). The remote learning paradox: How a crisis created a catalyst for educational technology integration. British Journal of Educational Technology, 53(5), 1125–1143. [CrossRef]

- Tucker, C. R. (2023). The complete guide to blended learning: Activating agency, differentiation, community, and inquiry for students. ISTE.

- Xie, H., Chu, H. C., Hwang, G. J., & Wang, C. C. (2023). Trends and development in technology-enhanced adaptive/personalized learning: A systematic review of journal publications from 2007 to 2022. Computers & Education, 201, 104835. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L., Niu, J., Long, M., & Fan, Y. (2024). The role of teacher support in technology-enhanced flipped classrooms: A mixed-methods study. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 62(1), 267–293. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).