1. Introduction

Airborne microplastics (AMPs) are widely distributed from urban regions to remote environments and exhibit clear long-range atmospheric transport, forming an atmospheric branch of the global plastic cycle [

1,

2]. During transport, AMPs undergo ultraviolet (UV) photo-oxidation, hydrolysis, and heterogeneous reactions with atmospheric constituents, leading to surface roughening, enhanced hydrophilicity, and the accumulation of water-soluble salts and organic matter [

3]. These physicochemical modifications can influence cloud microphysical processes, with recent studies reporting both suppression and enhancement of cloud condensation nuclei and ice-nucleating particle activities depending on polymer type and degradation state [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8]. UV-driven polymer degradation can also release greenhouse gases such as methane and carbon dioxide [

9], and aging-induced surface functionalization may intensify biological interactions; for example, photo-oxidized polyethylene terephthalate (PET) has been shown to trigger airway inflammation due to the sustained release of terephthalic acid [

10], while airborne microplastics have been detected in human lung tissue, demonstrating the potential for deep-lung deposition and persistence [

11,

12,

13]. These atmospheric and health implications highlight the need for quantitative indicators of AMPs’ chemical aging [

4].

Despite this growing recognition, source apportionment of AMPs has relied primarily on polymer type, morphology, and abundance, with limited integration of chemical-aging information [

3]. Incorporating UV-induced degradation as an additional dimension could help distinguish freshly emitted particles from atmospherically processed ones and provide insight into their transport pathways. However, evaluating UV-induced chemical aging in sub-10 µm AMPs remains technically challenging. Conventional infrared microscopy typically detects particles larger than ~30 µm and overlapping absorption bands—particularly in polymers contaivning intrinsic carbonyl groups—complicate quantitative oxidation assessments. Raman microspectroscopy offers submicron resolution [

14], but fluorescence interference and low throughput restrict its applicability to large environmental samples [

15,

16]. These limitations highlight the need for an analytical method capable of resolving subtle oxidation features in sub-10 µm AMPs

while processing large numbers of AMPs and samples at a practical speed suitable for environmental monitoring.

To address these challenges, we developed a micro–Fourier transform infrared attenuated total reflection (µFTIR-ATR) imaging approach [

8] that enables automated detection and chemical identification of particles smaller than 10 µm and quantifies subtle surface

subtle UV-driven oxidation. A key innovation of this method is a fourth-derivative oxidation index (1701/1716 cm⁻¹), which resolves overlapping ester and carboxylic acid carbonyl bands and therefore provides a sensitive aging metric even for polymers with strong intrinsic carbonyl signals such as PET. PET was selected as the target polymer because it is one of the most frequently detected AMPs in atmospheric environments [

3,

8], poses potential health risks due to the release of terephthalic acid during aging, and presents a rigorous analytical challenge. Finally, we apply this approach to ambient PET particles collected from Mt. Fuji, Tokyo, Osaka (Japan), and Siem Reap (Cambodia) to investigate regional differences in photo-oxidative aging and evaluate the usefulness of degradation-based indicators for interpreting atmospheric transformation processes and potential source attribution of AMPs.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Spectral Changes of Polymers Under UV Irradiation

The µFTIR (Spectrum 3/Spotlight 400, PerkinElmer, USA) employs a Cassegrain objective to focus IR radiation onto a high-refractive-index germanium ATR crystal (n ≈ 4.0). Total internal reflection generates an evanescent field that probes <1 µm into the sample surface, providing strong sensitivity to surface functional groups. A large-area Ge crystal (contact diameter 750 µm) enables efficient scanning, and a 16-element linear MCT array acquires 16 spectra per scan. The spatial sampling was 1.56 µm per pixel, sufficient to detect and map particles down to ~1.5–3 µm.

2.2. Sampling of Airborne Aerosols

Atmospheric aerosols were collected in August at four locations: the summit of Mt. Fuji, Japan (35.3636° N, 138.7264° E; 3776 m a.s.l.), Tokyo, Japan (35.6895° N, 139.6917° E), Osaka, Japan (34.6938° N, 135.5011° E), and Siem Reap, Cambodia (13.3618° N, 103.8606° E).At all sites, size-segregated aerosol samples were collected into >10 µm, 10–2.5 µm, and <2.5 µm aerodynamic diameter fractions. In Tokyo, Osaka, and Siem Reap, sampling was performed using a multi-nozzle cascade impactor (Tokyo Dylec Co., Ltd., Japan) operated at a constant volumetric flow rate of 20 L min⁻¹. Particles were collected onto PTFE-bonded glass fiber filters (TX40HI20-WW, Pallflex). At the summit of Mt. Fuji, aerosols were collected using a high-volume air sampler equipped with a size-segregating inlet, operated at a flow rate of 480 L min⁻¹, to obtain the same aerodynamic size fractions (>10 µm, 10–2.5 µm, and <2.5 µm).After sampling, all filters were sealed, stored in the dark at room temperature, and subjected to pretreatment prior to analysis.

2.3. Sample Pretreatment

Pretreatment followed a water-based extraction and oxidative cleanup workflow with minor modifications. Filter sections were sonicated in ultrapure water; filtrates were passed through hydrophilic PTFE membranes to remove soluble inorganics. Residues were oxidized with 30% H₂O₂ for two days to reduce organic matrix. Density separation with NaI (1.5 g cm⁻³) enriched plastic particles, and supernatants were filtered onto alumina Anodisc membranes (0.2 µm pore, 4 mm active area, Whatman). Filters were dried in a desiccator before analysis [

8,

17,

18].

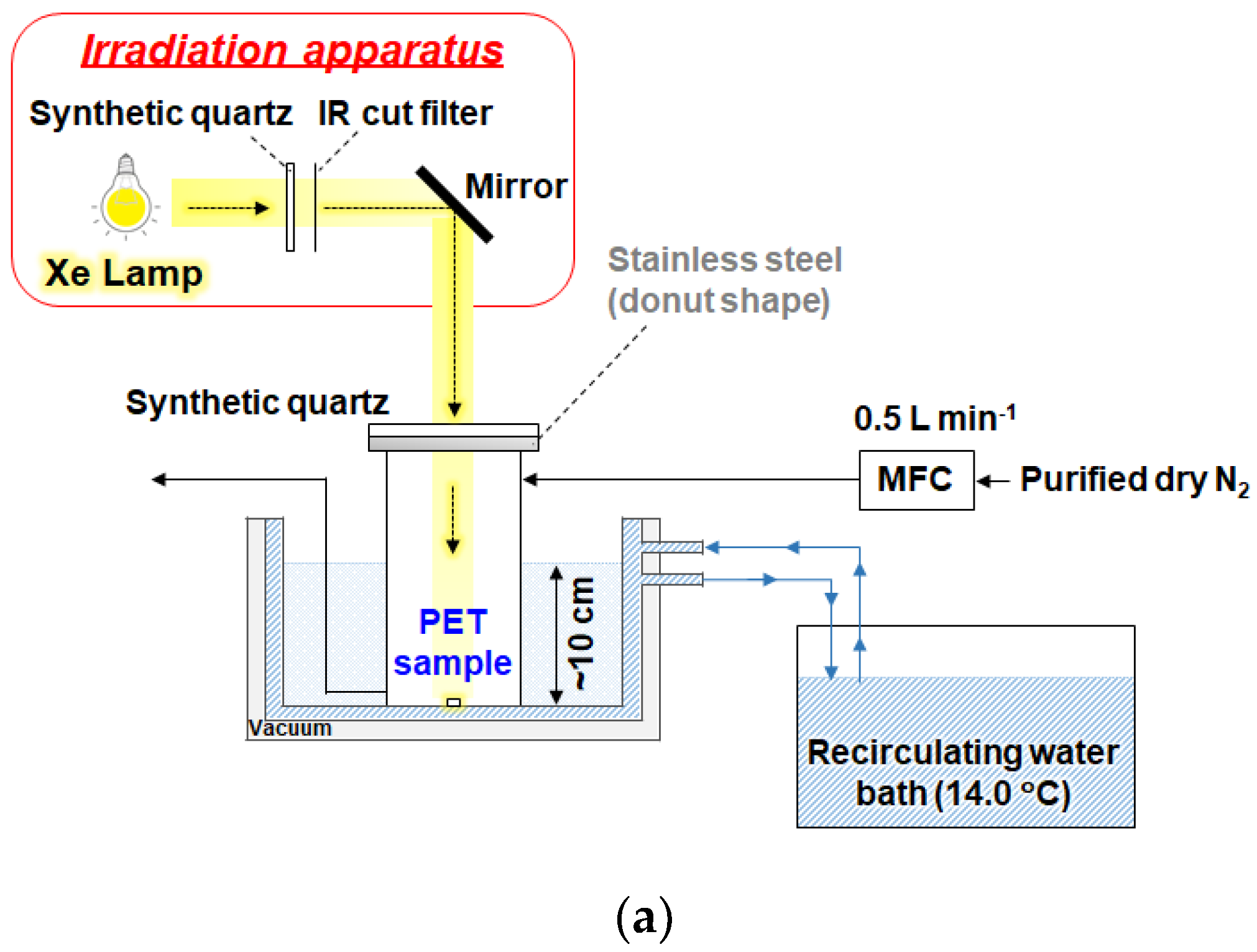

2.4. UV Irradiation Experiments

Figure 1 shows the schematic diagram of the UV irradiation experimental setup. Polymer test piece of PET (10 × 10 × 2 mm, Standard Test Pieces Co., Ltd.) was irradiated in a flow-type Pyrex chamber (Ø100 mm, height 200 mm, 0.157 L) sealed with a synthetic quartz window and silicone gasket. A xenon short-arc lamp (SX-UID 501 XAMQ, Ushio) with an IR-cut filter (SC1201, Asahi Spectra) provided UV-visible illumination while limiting thermal load. Dry N₂ (>99.99%) flowed at 0.5 L min⁻¹. To maintain the PET surface at 20 °C during UV irradiation, the cooling circulator (LTC-450A, AS ONE) was set to 14.0 °C, which compensated for the temperature increase caused by UV exposure in the sealed chamber. Irradiance at the sample surface was ~10 mW cm⁻² (ISA-3151, T&D). Irradiation was conducted for periods ranging from 1 day (24hours) to 7 days (168 hours). To correct for the spatial non-uniformity of irradiance on the sample surface, ATR imaging measurements were performed at the same positions where irradiance was measured on the polymer test pieces.

2.5. μFTIR ATR Imaging Measurement and Spectral Matching

ATR imaging surveyed five representative fields per alumina filter (covering ~22.4% of the filter area) at 1.56 µm pixel sampling over 750 × 750 µm fields. Spectra were acquired at room temperature. Identification used Spectrum 10 (PerkinElmer) with a curated library of ~140 in-house ATR spectra (virgin/UV-aged polymers, additives, inorganic/biogenic interferents) integrated with ~10,000 commercial references. Similarity scoring used Pearson correlation; high-scoring matches were accepted as tentative polymer IDs [

8,

17,

18]. For PET, fourth-order derivative spectra were computed to resolve overlapping carbonyl bands [

19], and the number of data points used for the derivative calculation was set to five to optimize the balance between noise suppression and wavenumber resolution.

3. Results and Discussion

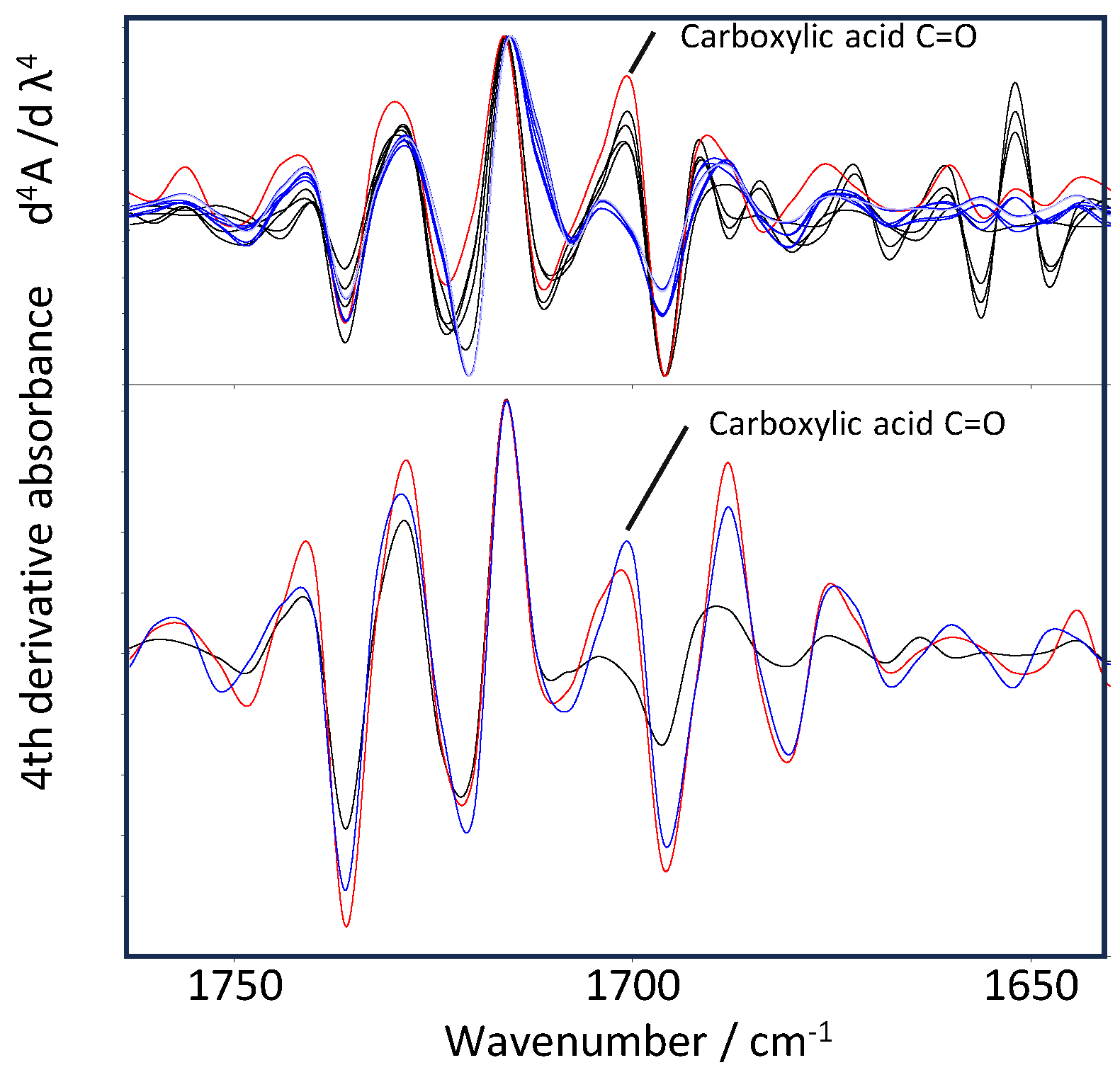

3.1. Derivative-Based Quantification of PET degradation

In this study, the term oxidation index refers to a carbonyl ratio (I₁₇₀₁/I₁₇₁₆) obtained from fourth-order derivative ATR-FTIR spectra. This metric separates newly formed carboxylic acid carbonyls from the intrinsic ester carbonyl band, enabling quantitative evaluation of UV-induced surface oxidation in PET. Fourth-order derivative spectra were calculated for both UV-irradiated PET standards and airborne PET particles collected from Mt. Fuji, Tokyo and Siem Reap (

Figure 2). This derivative processing clearly separated the acid carbonyl band at 1701 cm⁻¹ from the ester carbonyl band at 1716 cm⁻¹ [

20], enabling quantitative evaluation of surface oxidation. The oxidation index was defined as the fourth-derivative peak ratio (I₁₇₀₁/I₁₇₁₆). Laboratory UV experiments showed a systematic increase in this ratio from 1-day to 7-day irradiation, indicating progressive formation of carboxylic acid end groups.

In the fourth-derivative spectra of airborne PET particles (upper panel of

Figure 2), the blue line represents the non-irradiated PET standard used as a reference, the black line corresponds to a particle collected in Tokyo, and the red line corresponds to a particle collected in Siem Reap. In the laboratory PET standards (lower panel), the black line represents the non-irradiated polymer, the red line represents the 1-day irradiated sample, and the blue line represents the 7-day irradiated sample. These color assignments visualize the progressive enhancement of the 1701 cm⁻¹ band with increasing UV exposure in both environmental and laboratory samples. The spectral characteristics of PET particles collected in Tokyo closely resembled those of laboratory samples irradiated for approximately 7 days under controlled UV conditions, suggesting an equivalent photochemical aging corresponding to roughly two weeks of continuous summer sunlight. In contrast, PET particles from Siem Reap exhibited a markedly stronger 1701 cm⁻¹ acid carbonyl peak, indicating advanced photo-oxidation driven by intense tropical UV exposure.

These observations demonstrate that the degree of surface oxidation, quantified by the fourth-derivative carbonyl index, reflects local UV radiation environments and can serve as a quantitative indicator of atmospheric aging of airborne PET microplastics.

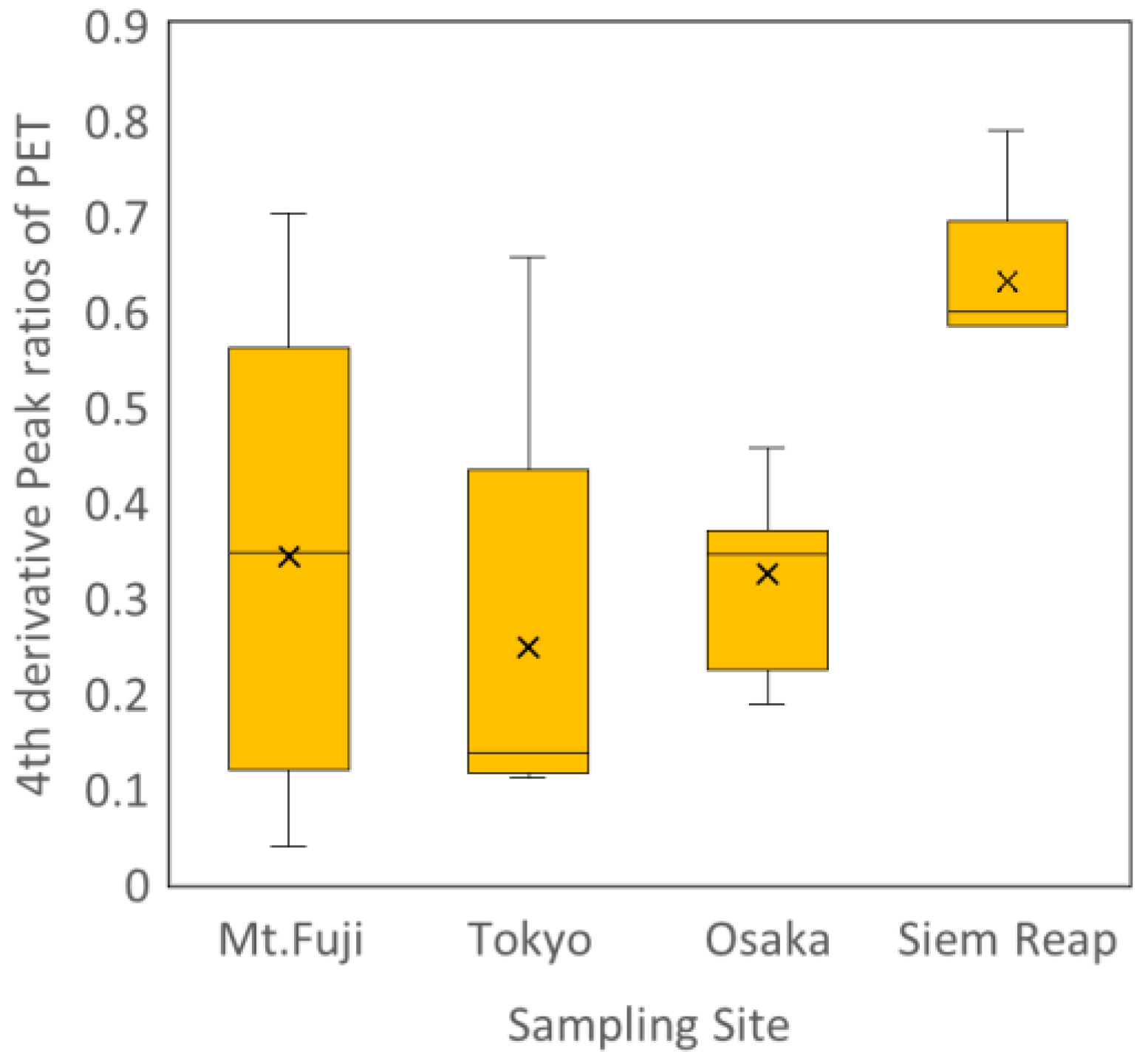

3.2. Comparison of Ambient PET Samples from Different Regions

Figure 3 compares the fourth-derivative oxidation index (I₁₇₀₁/I₁₇₁₆) of ambient PET particles collected from Mt. Fuji, Tokyo, Osaka, and Siem Reap. The oxidation index exhibited clear regional differences, reflecting the combined influence of local UV environments, meteorological conditions, and atmospheric residence times.

Mt. Fuji samples showed oxidation levels that were comparable to, and in some cases slightly higher than, those observed in Tokyo and Osaka. However, the Mt. Fuji dataset displayed a notably wide distribution, indicating substantial variability in atmospheric exposure histories. Although the high-altitude environment of Mt. Fuji may experience stronger incident UV irradiance than the urban lowland sites, the effective oxidation rate of PET is likely moderated by the lower ambient temperatures, which slow the kinetics of oxidative reactions [

21,

22]. These temperature-related effects may explain why the overall oxidation levels at Mt. Fuji do not markedly exceed those at urban sites despite the potential for higher UV flux.

Tokyo and Osaka exhibited intermediate oxidation levels, reflecting moderate UV exposure and typical atmospheric residence conditions for urban airborne particles. In contrast, PET particles from Siem Reap showed the highest oxidation indices, consistent with the intense tropical UV-A radiation and longer effective sunlight exposure characteristic of Southeast Asia.

Together, these results demonstrate that the fourth-derivative oxidation index provides a sensitive quantitative measure of regional atmospheric processing and captures environmentally relevant differences in the photo-oxidative aging of airborne PET microplastics.

3.3. Comparison with Previous Studies

Previous studies using ATR-FTIR or µFTIR imaging have primarily focused on polymer identification and qualitative assessment of environmental weathering rather than quantitative evaluation of photochemical degradation [

16]. Large-area ATR systems and germanium-crystal imaging have demonstrated the capability to detect sub–10 µm particles, but these approaches were generally limited to particle detection performance and did not establish reliable metrics for quantifying oxidation processes.

The conventional carbonyl index (CI) [

23], which is widely applied to assess oxidation in polymers such as polyethylene or polypropylene [

24,

25], is not suitable for PET because its intrinsic ester carbonyl band overlaps strongly with newly formed carboxylic acid carbonyls during photo-oxidation. As a result, the CI underestimates oxidation in PET and cannot resolve early-stage degradation.

In contrast, the fourth-derivative spectral ratio (I₁₇₀₁/I₁₇₁₆) introduced in the present study effectively separates the adjacent ester and acid carbonyl bands and provides a sensitive quantitative indicator of surface oxidation. Combined with µFTIR-ATR imaging, this method enables simultaneous detection, chemical identification, and degradation quantification of airborne microplastics smaller than 10 µm. To our knowledge, this is the first study to demonstrate a clear positive relationship between the degree of PET photo-oxidation in real atmospheric samples and regional UV-A radiation intensity across multiple Asian locations.

These findings highlight the importance of derivative-based approaches for polymers with intrinsic carbonyl functionalities and position the fourth-derivative PET oxidation index as a promising tool for quantitative assessment of photo-oxidative aging in airborne microplastics.

3.4. Advantages of µFTIR ATR Imaging for Microplastic Analysis

µFTIR-ATR imaging offers several advantages for the analysis of airborne microplastics, particularly those in the sub–10 µm size range. Compared with conventional transmission or reflection FTIR microscopy, the ATR configuration provides enhanced spatial resolution and high sensitivity to surface chemical changes due to the shallow penetration depth of the evanescent field (<1 µm) [

26]. This makes the technique especially well suited for detecting early-stage oxidation, which predominantly develops on particle surfaces and is often subtle in fine airborne particles.

The combination of a high-refractive-index germanium ATR crystal and a linear MCT detector enables high-throughput spectral imaging while maintaining strong signal-to-noise performance across thousands of pixels. This capability allows quantitative evaluation of numerous fine particles within a single measurement, an essential requirement for atmospheric microplastic research where particles are often scarce and distributed heterogeneously on filter substrates.

While Raman microspectroscopy can achieve submicron spatial resolution; however, its applicability to atmospheric samples is frequently hindered by fluorescence interference, long acquisition times, and low throughput. By contrast, µFTIR-ATR imaging provides rapid, not susceptible to fluorescence interference with robust spectral reproducibility. When combined with the fourth-derivative oxidation index developed in this study, µFTIR-ATR imaging provides a powerful means of simultaneously detecting, identifying, and quantifying photo-oxidative degradation in airborne PET microplastics.

These advantages position µFTIR-ATR imaging as a practical and highly sensitive method for characterizing chemical aging in fine atmospheric microplastics.

3.5. Interpretation of Photochemical Degradation Signatures

The observed increases in the acid carbonyl band at 1701 cm⁻¹ and the broadening of the carbonyl and hydroxyl regions in both laboratory-irradiated and ambient PET particles reflect characteristic pathways of UV-induced polymer degradation. PET photodegradation typically proceeds through photoexcitation of the ester chromophore, followed by chain scission, formation of peroxy radicals, and subsequent generation of oxygen-containing functional groups such as carboxylic acids and hydroxyl moieties. These transformations are consistent with established photochemical mechanisms reported for PET [

27].

The fourth-derivative oxidation index (I₁₇₀₁/I₁₇₁₆) introduced in this study provides a sensitive quantitative measure of these processes by resolving the newly formed acid carbonyls from the intrinsic ester carbonyl band. Because the derivative processing minimizes baseline variations and enhances subtle spectral features, it enables the detection of early-stage oxidation that would otherwise be obscured in raw ATR-FTIR spectra. This capability is particularly important for airborne PET microplastics, which often exhibit only modest degrees of surface oxidation due to their small size and relatively short atmospheric residence times.

The strong correspondence between the oxidation index values of ambient PET particles and laboratory irradiation equivalents, as well as the systematic regional differences observed across Mt. Fuji, Tokyo, Osaka, and Siem Reap, further supports the interpretation that UV-driven photo-oxidation is a dominant atmospheric aging pathway for PET. Since the rate and extent of oxidation depend on both incident UV intensity and the duration of atmospheric exposure, the fourth-derivative carbonyl index can serve as a semi-quantitative proxy for the photochemical age of airborne PET particles.

3.6. Implications for Source Identification and Atmospheric Transport

The substantial regional variability in the oxidation index of airborne PET particles provides insights into both their atmospheric transformation and their potential sources. PET particles with low oxidation levels, such as those observed in some samples from Tokyo and Osaka, may represent freshly emitted materials originating from local urban activities or recent mechanical fragmentation of larger plastic items. These particles likely experienced limited photochemical processing before being captured.

In contrast, highly oxidized PET particles—particularly those collected in Siem Reap—suggest exposure to intense tropical UV radiation and potentially longer atmospheric residence times. Such particles may originate from regional or transboundary sources and undergo extended photochemical aging during atmospheric transport. The high oxidation values observed in Mt. Fuji samples, alongside their wide variability, further indicate that particles reaching high-altitude environments may follow diverse transport pathways, including uplift from boundary-layer pollution, cloud-processing cycles, or mixing within the free troposphere.

Integrating the fourth-derivative oxidation index with polymer-type distributions and particle-size information enhances the capacity to distinguish between local, regional, and remotely transported airborne microplastics. Because oxidation reflects a combination of both UV exposure intensity and atmospheric lifetime, it offers a complementary dimension to traditional source identification approaches that rely solely on polymer identity or morphology. This degradation-based framework may therefore improve our understanding of cross-boundary transport, vertical redistribution, and transformation processes of airborne microplastics in the troposphere.

3.7. Limitations and Future Perspectives

Although µFTIR-ATR imaging provides high sensitivity to surface chemical changes in sub–10 µm airborne microplastics, several limitations should be considered when interpreting the oxidation index derived in this study. First, ATR-FTIR measurements probe only the outermost few hundred nanometers of a particle. The oxidation index therefore reflects surface aging, whereas internal structural modifications or bulk oxidation—particularly in thicker or aggregated particles—cannot be directly assessed. Consequently, the index should be interpreted as a surface-sensitive indicator rather than a comprehensive measure of total polymer degradation.

Second, the quantitative relationship between the oxidation index and absolute UV dose or atmospheric exposure time is likely influenced by environmental conditions, including temperature, relative humidity, and the presence of reactive oxidants such as ozone or hydroxyl radicals. These factors may accelerate or suppress oxidation in ways not captured by the controlled UV irradiation experiments. Additional calibration studies incorporating variable environmental conditions are needed to more precisely constrain the dose–response behavior of airborne PET.

Third, while the fourth-derivative oxidation index effectively resolves overlapping carbonyl bands in PET, extending this approach to other polymers—especially those lacking distinct oxidation products—may require alternative spectral metrics or higher-order derivative schemes. Furthermore, integrating µFTIR-ATR with complementary methods such as Raman microspectroscopy, mass spectrometry, or thermal analysis could provide a more complete understanding of microplastic aging and transformation processes.

Future research should aim to expand derivative-based oxidation metrics to a broader range of polymer types and investigate atmospheric aging under more realistic conditions, including fluctuating UV intensities, diurnal temperature cycles, and interactions with cloud or fog droplets. This integrated framework will help clarify the environmental behavior, climatic relevance, and health implications of airborne microplastics.

4. Conclusions

This study established a derivative-based approach for quantifying the photo-oxidative degradation of airborne polyethylene terephthalate (PET) microplastics using µFTIR-ATR imaging. The fourth-derivative oxidation index (I₁₇₀₁/I₁₇₁₆) effectively separated newly formed acid carbonyls from the intrinsic ester carbonyl band, enabling sensitive and reproducible evaluation of surface oxidation in sub–10 µm particles. Laboratory UV irradiation experiments confirmed that the index increases systematically with irradiation dose, demonstrating its capability to detect early-stage oxidation.

Application of the method to ambient PET particles collected from Mt. Fuji, Tokyo, Osaka, and Siem Reap revealed clear regional differences in oxidation levels that reflect local UV radiation environments and atmospheric exposure conditions. PET in Siem Reap exhibited the highest degree of oxidation, whereas samples from Mt. Fuji, Tokyo, and Osaka showed intermediate but variable oxidation signatures. These results highlight that the fourth-derivative oxidation index can serve as a quantitative indicator of the photochemical aging of airborne microplastics and may provide additional constraints for interpreting transport pathways and identifying emission sources.

Overall, the derivative-based µFTIR-ATR framework presented here offers a practical and sensitive tool for assessing the atmospheric transformation of airborne microplastics. Future work extending this approach to other polymer types and more complex atmospheric conditions will further advance our understanding of the environmental behavior and potential health implications of airborne microplastics.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.N. and Y.F.; methodology, Y.N.; software, Y.N.; validation, Y.N., Y.F., and N.T.; formal analysis, Y.N.; investigation, Y.N. and Y.F.; resources, Y.F. and N.T.; data curation, Y.N.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.N.; writing—review and editing, Y.F. and N.T.; visualization, Y.N. and Y.F.; supervision, N.T.; project administration, Y.F.; funding acquisition, N.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding. The Article Processing Charge (APC) was funded by PerkinElmer Japan G.K.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors are deeply grateful to Professor Hiroshi Okochi (Waseda University, Japan) for providing atmospheric aerosol samples and valuable discussions. During the preparation of this manuscript/study, the author used ChatGPT 5 for the purposes of generating text. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AMPs |

Airborne Microplastics |

| PET |

Polyethylene Terephthalate |

| µFTIR |

Micro-Fourier Transform Infrared spectroscopy |

| ATR |

Attenuated Total Reflection |

| LAATR |

Large-Area Attenuated Total Reflection |

| PFA |

Focal Plane Array |

| CI |

Carbonyl Index |

References

- Zhang, Y.; Kang, S.; Allen, S.; Allen, D.; Gao, T.; Sillanpää, M. Atmospheric microplastics: A review on current status and perspectives. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2020, 203, 103118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, S.; Allen, D.; Phoenix, V.R.; Le Roux, G.; Durántez Jiménez, P.; Simonneau, A.; Binet, S.; Galop, D. Atmospheric transport and deposition of microplastics in a remote mountain catchment. Nat. Geosci. 2019, 12, 339–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, D.; Allen, S.; Abbasi, S.; Baker, A.; Bergmann, M.; Brahney, J.; Butler, T.; Duce, R.A.; Evangeliou, N.; Jickells, T.; et al. Microplastics and nanoplastics in the marine–atmosphere environment. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2022, 3, 393–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aeschlimann, M.; Li, G.H.; Kanji, Z.A.; Ladino, L.A.; et al. Potential impacts of atmospheric microplastics and nanoplastics on cloud formation processes. Nat. Geosci. 2022, 15, 967–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seifried, T.M.; Jia, H.; Kanji, Z.A.; Grönquist, P.; Bünzli, C.; et al. Microplastic particles contain ice nucleation sites that can be inhibited by atmospheric aging. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 58, 15711–15721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monger, B.C.; Brahney, J.; Allen, D.; et al. Weathering influences the ice nucleation activity of microplastics. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Schmidt, M.U.; Knopf, D.A.; et al. Snowballing impact of spontaneously degrading microplastics on atmospheric ice nucleation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2025, 147, 36376–36382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Okochi, H.; Tani, Y.; Hayami, H.; Minami, Y.; Katsumi, N.; Takeuchi, M.; Sorimachi, A.; Fujii, Y.; Kajino, M.; et al. Airborne hydrophilic microplastics in cloud water at high altitudes and their role in cloud formation. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2023, 21, 3055–3062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Royer, S.-J.; Ferrón, S.; Wilson, S.T.; Karl, D.M. Production of methane and ethylene from plastic in the environment. Nat. Clim. Change 2018, 8, 679–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishihara, Y.; Terasaki, M.; Tamura, K.; Niimi, N.; Takeda, K.; et al. Impact of artificial sunlight aging on the respiratory effects of polyethylene terephthalate microplastics through degradation-mediated terephthalic acid release in male mice. Toxicol. Sci. 2025, 203, 242–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, S.; Huang, X.; Bi, R.; Guo, Q.; Yu, X.; Zeng, Q.; et al. Detection and analysis of microplastics in human sputum. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 2476–2486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amato-Lourenço, L.F.; Carvalho-Oliveira, R.; Júnior, G.R.; dos Santos Galvão, L.; Ando, R.A.; Mauad, T. Presence of airborne microplastics in human lung tissue. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 416, 126124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenner, L.C.; Rotchell, J.M.; Bennett, R.T.; Cowen, M.; Tentzeris, V.; Sadofsky, L.R. Detection of microplastics in human lung tissue using μFTIR spectroscopy. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 831, 154907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araujo, C.F.; Nolasco, M.M.; Ribeiro, A.M.P.; Ribeiro-Claro, P.J.A. Identification of microplastics using Raman spectroscopy: Latest developments and future prospects. Water Res. 2018, 142, 426–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Primpke, S.; Lorenz, C.; Rascher-Friesenhausen, R.; Gerdts, G. An automated approach for microplastics identification using focal plane array-based reflectance μFTIR imaging. Anal. Methods 2017, 9, 1499–1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Lüttjohann, S.; Vianello, A.; Lorenz, C.; Liu, F.; Vollertsen, J. Detecting small microplastics down to 1.3 µm using large area ATR-FTIR. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2024, 198, 115795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokunaga, Y.; Okochi, H.; Tani, Y.; Niida, Y.; Tachibana, T.; Saigawa, K.; Katayama, K.; Moriguchi, S.; Kato, T.; Hayama, S. Airborne microplastics detected in the lungs of wild birds in Japan. Chemosphere 2023, 321, 138032–138041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunaga, N.; Okochi, H.; Niida, Y.; Miyazaki, A. Alkaline extraction yields a higher number of microplastics in forest canopy leaves: implication for microplastic storage. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2024, 22, 1599–1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savitzky, A.; Golay, M.J.E. Smoothing and Differentiation of Data by Simplified Least Squares Procedures. Anal. Chem. 1964, 36, 1627–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colthup, N.B.; Daly, L.H.; Wiberley, S.E. Introduction to Infrared and Raman Spectroscopy, 3rd ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1990; pp. 301–314. [Google Scholar]

- Borzęcka, J.; Kowalonek, J.; Olewnik-Kruszkowska, E.; Moraczewski, K. Changes in the Chemical Composition of Polyethylene Terephthalate under UV Radiation, Humidity, and Temperature Conditions. Polymers 2024, 16, 2249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sang, T.; Wallis, C.J.; Hill, G.; Britovsek, G.J.P. Polyethylene terephthalate degradation under natural and accelerated weathering conditions. Eur. Polym. J. 2020, 136, 109873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellor, D.C.; Chapman, A.V.; Dumbleton, J.H. Infrared spectroscopic studies of the photo-oxidation of polymers. Eur. Polym. J. 1973, 9, 219–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlsson, D.J.; Bazan, G.; Chmela, S.; Wiles, D.M.; Russell, K.E. Oxidation of solid polyethylene films: Effects of backbone branching. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 1987, 17, 213–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlsson, D.J.; Wiles, D.M. The photooxidation of polypropylene. Macromolecules 1976, 9, 859–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, P.R.; De Haseth, J.A.; Winefordner, J.D. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectrometry, 2nd ed.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2007; pp. 325.

- Fujimoto, E.; Fujimaki, T. Effects of pendant methyl groups and lengths of methylene segments in main-chains on photodegradation of aliphatic polyesters. Polym. J. 1999, 31, 645–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).