1. Introduction

Maintaining a running catalog of space objects orbiting the Earth is essential for effective management of the near-Earth space environment. Ephemerides information is publicly accessible via the NORAD catalog, while other organizations, such as the European Space Agency (ESA), also provide data derived from their own observations. Sustaining these catalogs over time requires both comprehensive observational data and accurate predictions of object trajectories, which are achieved through orbit-propagation methods.

Orbit propagation refers to computer software that implements a solution to the dynamical systems governing the motion of Resident Space Objects (RSOs). Such software determines the state of an RSO at a specified time, given an initial condition. The accuracy and computational efficiency of an orbit propagator depend primarily on the force model used in the dynamical system and the integration technique employed to obtain the solution.

The primary force considered is the gravitational attraction of an ideally spherical Earth. However, other forces, such as Earth’s nonsphericity, atmospheric drag, gravitational perturbations from other celestial bodies, and solar radiation pressure, can significantly modify the RSO’s trajectory. An important characteristic of this dynamical system is that not all perturbations need to be included in every model; typically, only those most relevant to the specific orbiter, its orbital characteristics, and the mission’s scientific objectives are considered. Integration techniques further categorize orbit propagators into general perturbations, special perturbations, and semianalytic theories.

General perturbation, or analytical, theories [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5] are derived from direct analytic integration of the equations of motion and are primarily characterized by their ability to preserve the essential qualitative behavior of orbital motion. These approaches are based on truncated series expansions [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13]. The resulting solutions are valid for arbitrary initial conditions and are formulated as explicit functions of time, physical parameters, and integration constants. Once the RSO state is known at a given time, its future state can be determined through a single evaluation of the analytical solution. The accuracy of a general perturbation theory is directly proportional to the fidelity of its force model and the order of the truncated expansion employed.

On the other hand, special perturbation methods refer [

14,

15] to the direct numerical integration of the equations of motion, including any external forces. In these approaches, introducing a new force into the equations of motion is achieved by simply expressing the perturbation in terms of time and the object’s state. In addition, achieving high accuracy with these methods requires using small integration steps, which penalises their computational efficiency. Nevertheless, special perturbation theories are usually much slower than their analytical counterparts, though generally provide greater accuracy.

Finally, semianalytical techniques [

16,

17,

18,

19] were developed to leverage both general and special perturbation theories. These methods seek to combine the accuracy of numerical techniques and the speed advantages of analytical techniques. This approach achieves these results by separating long- and short-periodic terms, which limit the integration step size for numerical methods. Long-periodic terms correspond to cycles exceeding one orbital period, while short-periodic terms are related to cycles shorter than one orbital period. Step sizes of up to 1 day can be employed, maintaining accuracy comparable to special perturbation methods while substantially reducing computation time.

Currently, improving the accuracy or computational efficiency of the aforementioned techniques obviously requires actions such as enhancing the force model, implementing a more precise integration method, parallelising the code, or subtle refinements such as the selection of variables or reference systems. Each of these approaches constitutes an invasive procedure.

Reference [

20] introduces a fourth non-invasive alternative approach, termed hybrid perturbation theory, that integrates a numerical, analytical, or semi-analytical propagator with time-series forecasting techniques. The forecasting methods employed in [

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32] utilize both classical statistical approaches and artificial intelligence techniques.

The forecasting part of the method is used to increase the accuracy of the classical orbit propagator by modelling effects not accounted for by it. These effects can range from the problem’s own uncertainties to the force model considered or the accuracy of the integration method used in the orbit propagator. To enable subsequent increases in accuracy, the forecasting component needs additional information to recover for missing effects. Therefore, besides knowing the RSO state at an initial time, the forecaster must also know the same quantities accurately over a certain period of time. It is worth noting that the additional information can be obtained from observations or pseudo-observations generated by a highly accurate orbit propagator. These kinds of augmented orbit propagators have been named hybrid propagators. Basically, a hybrid propagator assumes that the current trajectory can be split into two parts of quite different nature: an approximate solution that accounts for the main dynamical effects, on the one hand, and a statistical error function that emulates the non-modeled dynamics, on the other.

However, given the large number of objects in the current space catalog, with over 40,000 RSOs requiring propagation, a balance between accuracy and computational efficiency is necessary. High-fidelity propagation models require step-by-step numerical integration, which is computationally intensive because small step sizes are required. In contrast, simplified models may allow for analytical solutions, thereby reducing computational burden. In either case, the orbit propagation program relies solely on the initial conditions, such as TLEs and the propagation model, such as SGP4 [

33,

34,

35], to make its predictions. On the other hand, the NORAD catalog’s collection of past TLEs can be used to improve orbit predictions by accounting for non-modeled effects.

SGP4 is founded on the analytical theories of artificial satellites developed by [

1,

3]. Initially, SGP4 modeled perturbations using only zonal gravitational terms up to J4 and atmospheric drag, as described by [

36]. With the increased prevalence of Molniya and geostationary orbits, deep space modeling, specifically Simplified Deep-space Perturbation-4 (SDP4), was incorporated into SGP4 [

34,

35]. This integration included lunisolar and tesseral-harmonic resonance effects, as developed by [

37,

38].

This paper presents a hybrid version of the well-known SGP4 orbit propagator, named HSGP4, based on an artificial neural networks and adapted for Galileo-type orbits. The HSGP4 propagator operates in conjunction with a Hybrid TLE (HTLE), an extension of the classical TLE that encapsulates both TLE information and model parameters.

Section 1 outlines the general methodology for developing hybrid orbit propagators.

Section 2 details the methodology used to develop the hybrid orbit propagator.

Section 3 describes the data preparation process.

Section 4 discusses the selection of optimal neural network architectures. Finally,

Section 5 summarizes the study and discusses potential future research directions.

3. Data Preprocessing

As discussed in

Section 2.1, the selection of a hybrid propagator depends on the number of variables included in the predictive module, and no universal solution exists. This section evaluates the best combination that improves the accuracy of the SGP4 propagator while maintaining computational efficiency. The hybrid propagator is specifically tailored to the orbital region of the Galileo constellation.

3.1. TLE Data

The first step in developing the hybrid version of SGP4 (HSGP4) is to understand its perturbation model and the integration method over a time interval. To assess this, we study the distance error obtained when comparing SGP4 with pseudo-observations generated by the high-accuracy numerical orbit propagator AIDA (Accurate Integrator for Debris Analysis) [

39]. The perturbation model used in AIDA includes Earth’s gravitational field (up to

), solar radiation pressure, and a third-body point-mass force model.

The analysis begins with a set of 313 TLEs from a Galileo satellite (NORA ID 40545). These TLEs provide an initial, comprehensive overview of the SGP4 behavior of this satellite over time. The data set was obtained from Space Track (

https://www.space-track.org) and covers the period from April 19, 2015, to December 28, 2016.

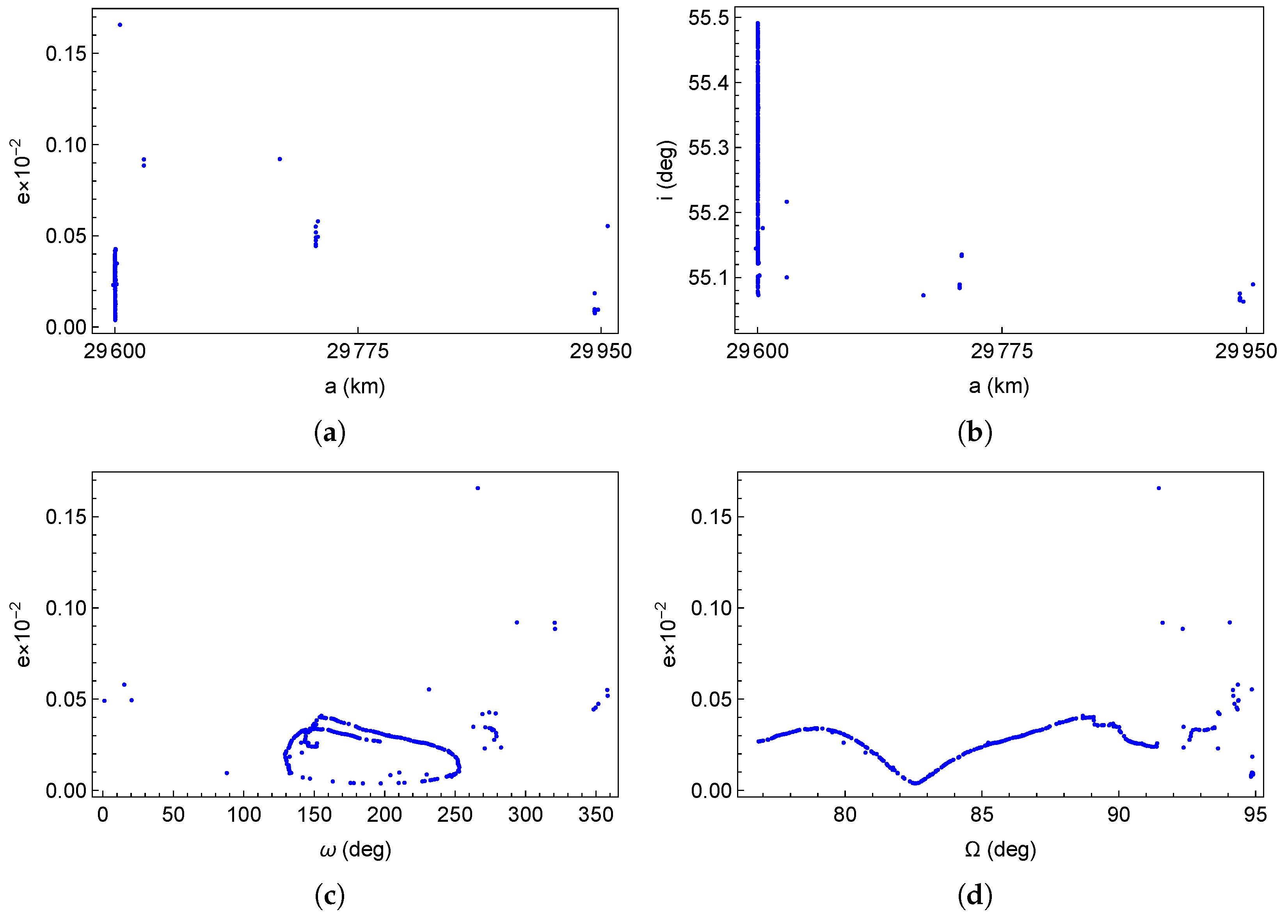

Figure 1 presents scatter diagrams for the considered TLEs in the two-dimensional parameter planes:

,

,

, and

. The semi-major axis values range from

to

km, with a peak near

km. Eccentricities span from

to

, and inclination values are approximately

. The argument of perigee ranges from

to

, showing a greater concentration above

and below

. The right ascension of the ascending node varies between

and

, while the mean anomaly ranges from

to

.

3.2. Exploratory Data Analysis

In this Subsection, we analyze the impact that correcting the error of a specific variable or a combination of them may have on the accuracy of the SGP4. The orbital variables are the first set to consider because they provide the geometric description of the differences between the numerical integrator and SGP4. The maximum, , median, , and the minimum SGP4 distance errors are approximately 52.01, 17.35, 10.73, 6.29, and 1.31 km, respectively.

Initially, each series is considered separately. For instance, the mean anomaly, , is replaced with , that is, is substituted for the best possible determination of the mean anomaly, which is , while the other time series for the rest of variables are left unchanged. Then, the distance error after 30 days of propagation is calculated to assess the variable’s effect on reducing it. Finally, we use the same process to check the distance error across the 64 possible combinations of variables. It is worth noting that the maximum error reduction is reached when all the variables are replaced, therefore leading to zero errors, which is the case for .

There are 16 parameter combinations that yield lower distance errors than SGP4 across all TLEs. These combinations are as follows:

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

and

. As can be seen, all combinations include the arguments of the perigee and the node.

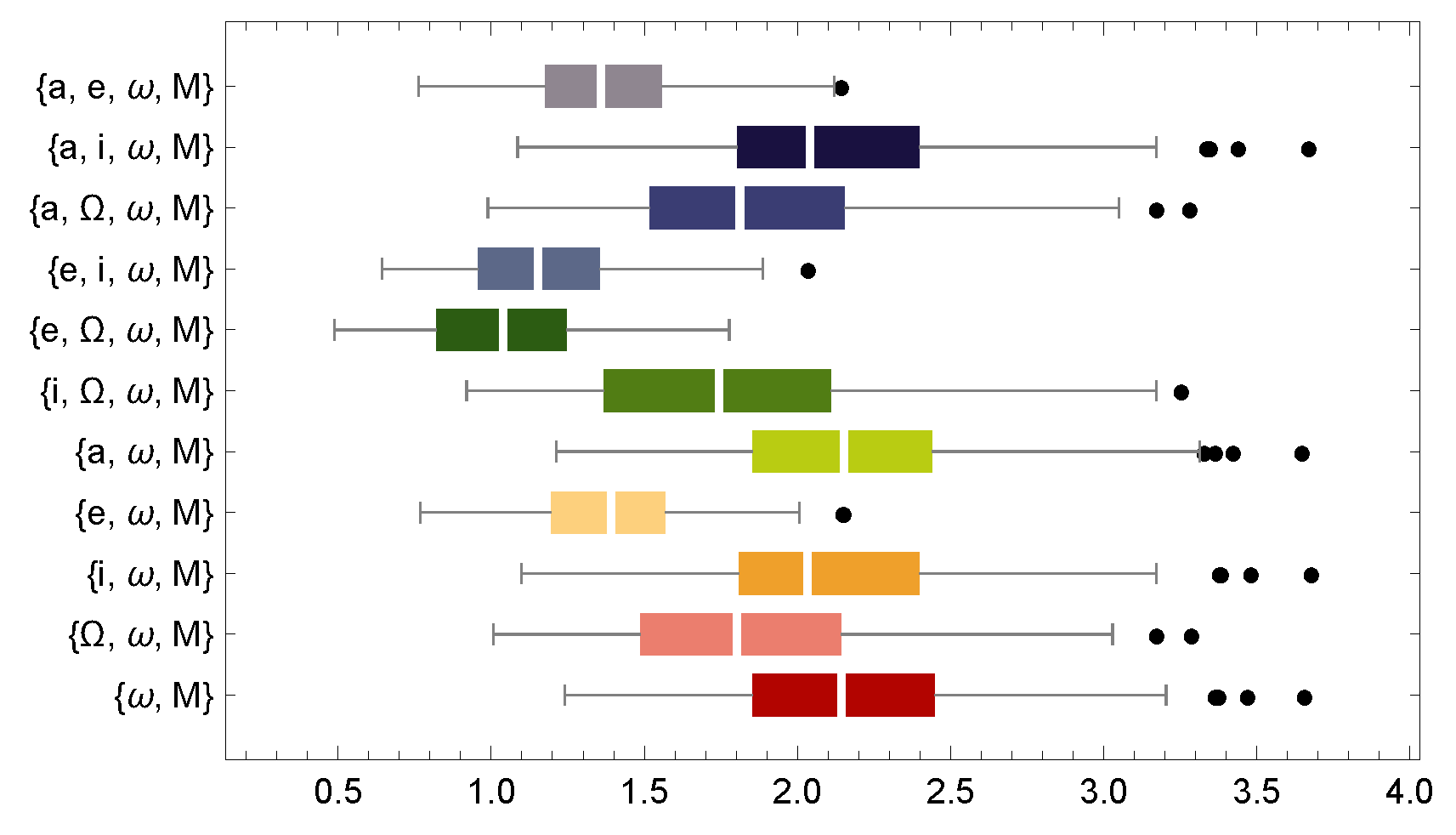

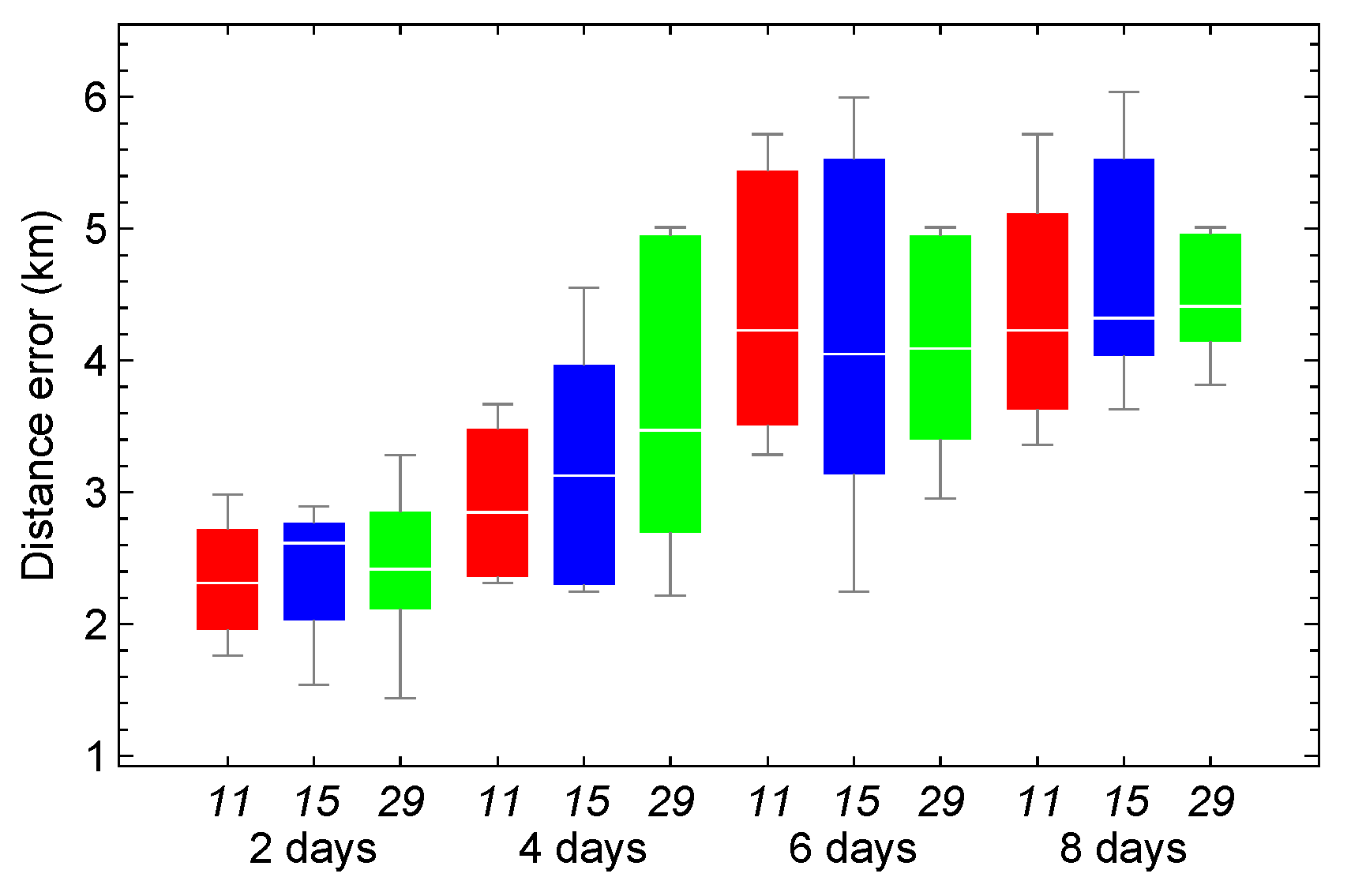

Figure 2 presents box-and-whisker plots for the best combinations of fewer than five variables that reduce distance errors between the numerical propagator and SGP4. For the combination

, the maximum,

, median,

, and minimum distance errors are approximately 3.6, 2.4, 2.1, 1.8, and 1.2 km, respectively. These values indicate the optimal performance achievable by this combination.

The analysis is subsequently extended to polar-nodal variables to develop parsimonious models, defined as the simplest models with minimal assumptions and variables while maximizing explanatory power. There are 32 combinations that improve distance error relative to SGP4 for all TLEs. These combinations include

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

, and

.

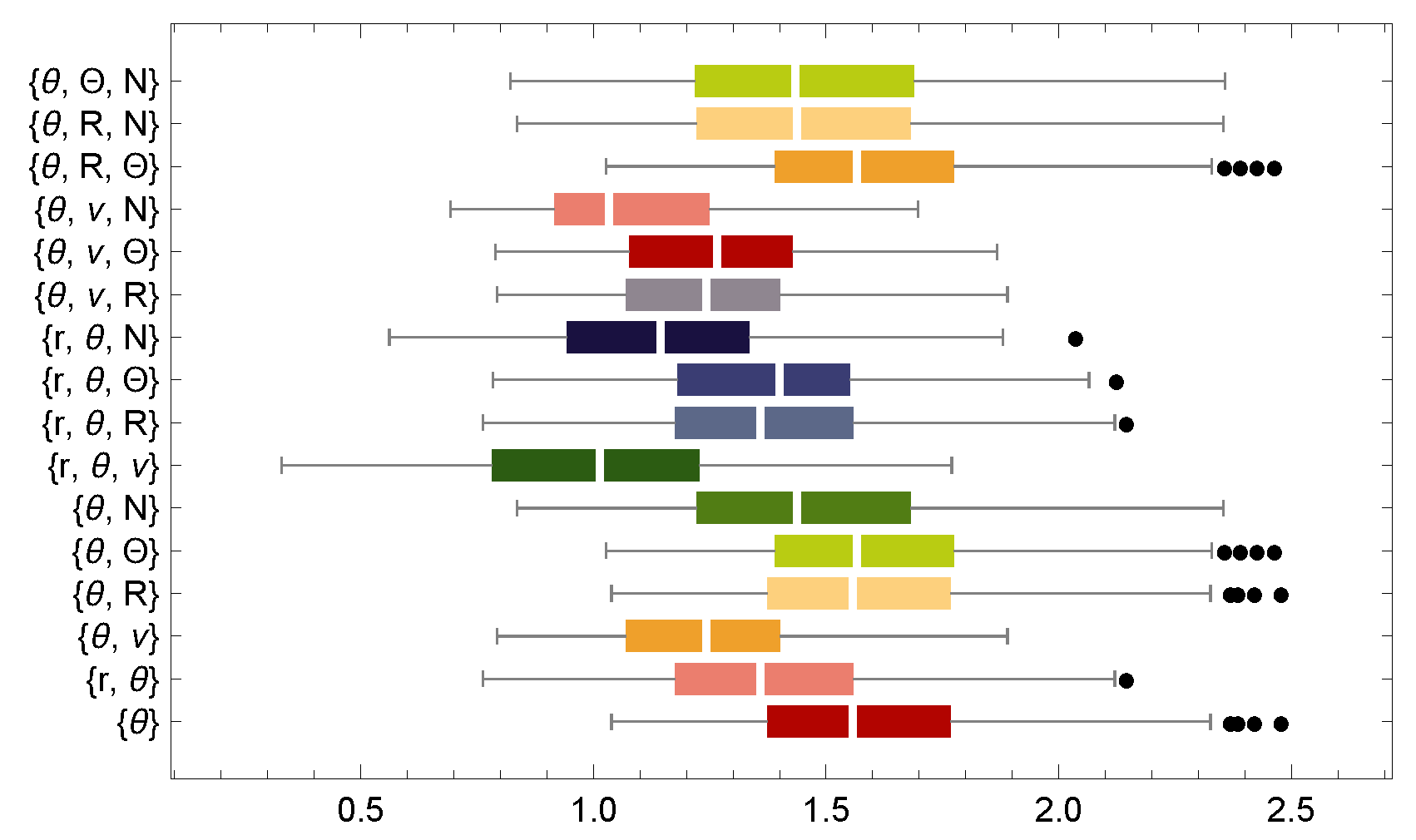

Figure 3 presents a box-and-whisker plot of the most effective variable combinations for reducing SGP4 distance errors. The plot considers only those combinations that reduce the maximum distance error between the numerical propagator and SGP4 to fewer than three variables. Notably, one of the most effective combinations consists solely of the variable

, although the optimal combination is

. For the combination

, the maximum,

, median,

, and minimum distance errors are approximately 2.4, 1.7, 1.5, 1.3, and 1 km, respectively. These results are slightly better than the combination obtained using the orbital elements

. Remember that the argument of latitude is defined as

, where

f denotes the true anomaly and is related to

M through the Kepler equation.

3.3. Error in Argument of Latitude

This subsection examines the error associated with the argument of latitude and evaluates its significance for improving the accuracy of propagation models.

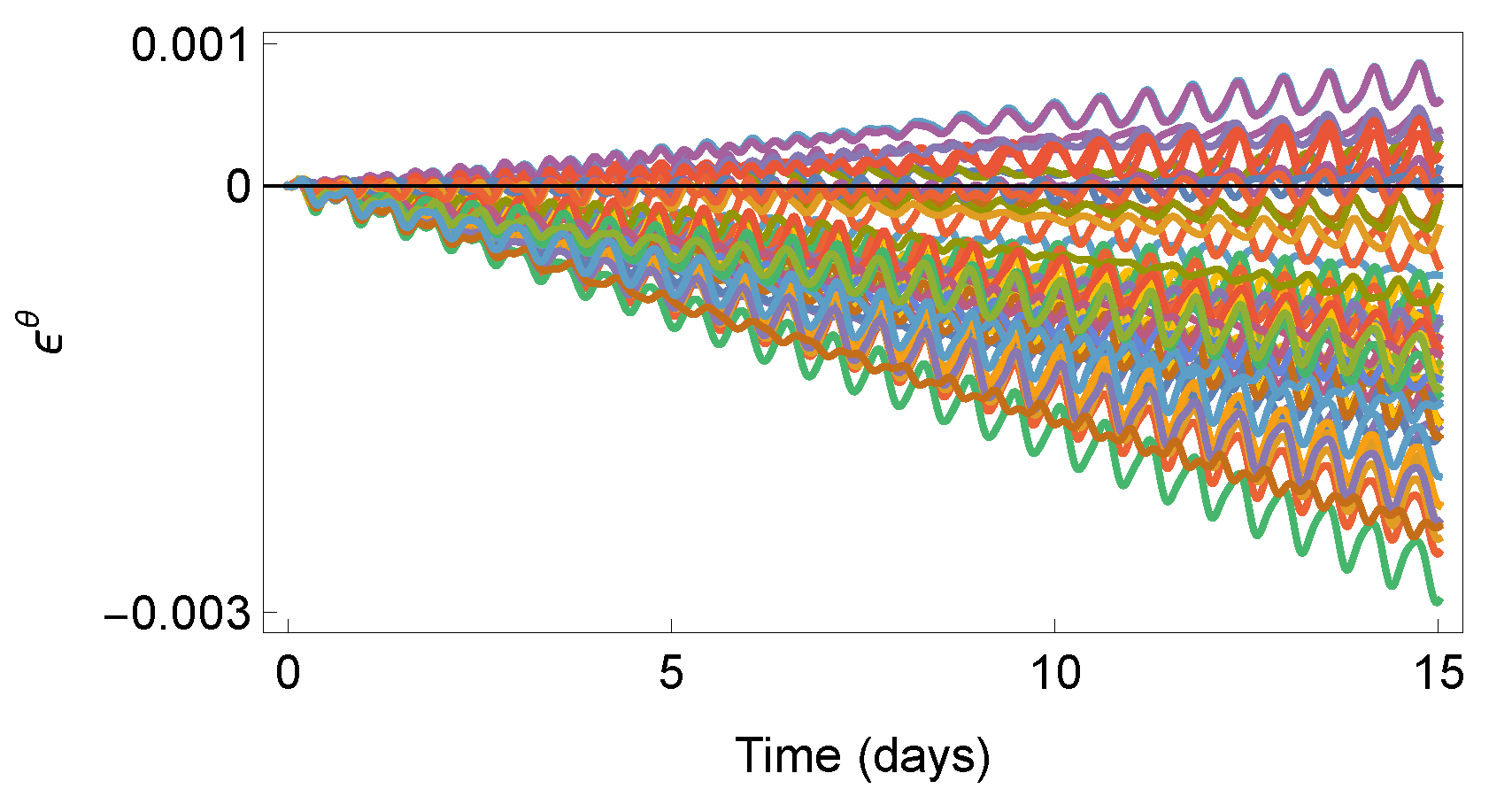

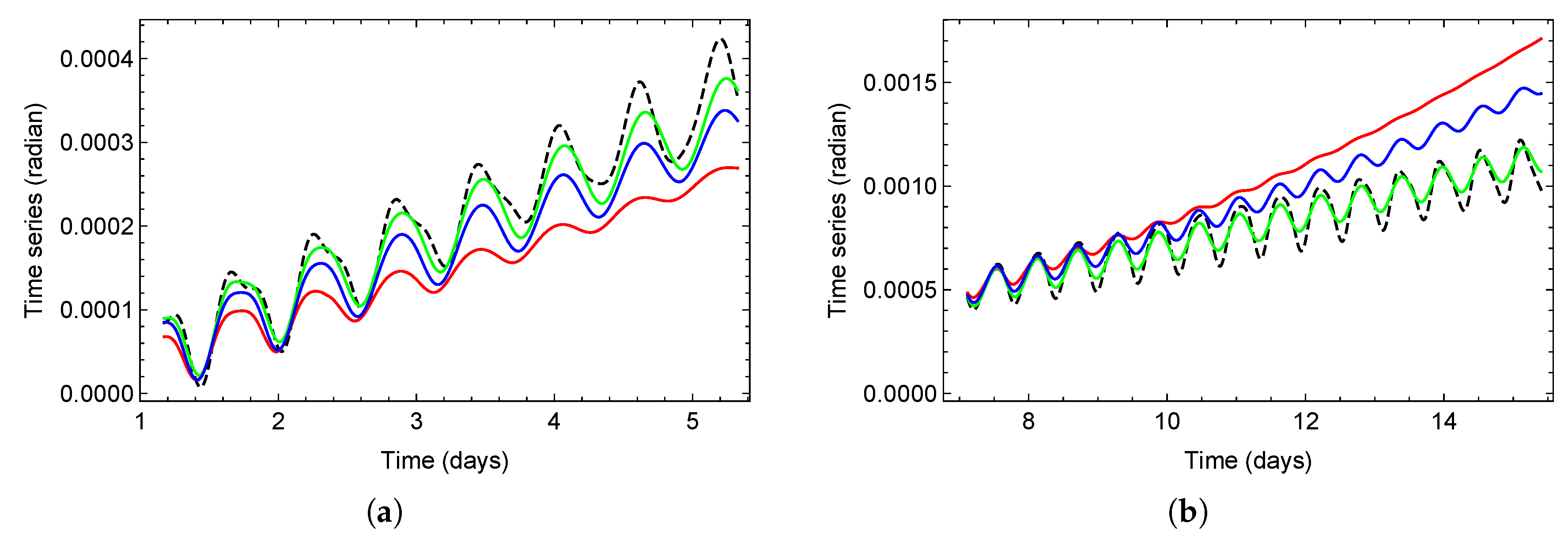

Figure 4 plots a representative sample of the time series of the error in the argument of latitude

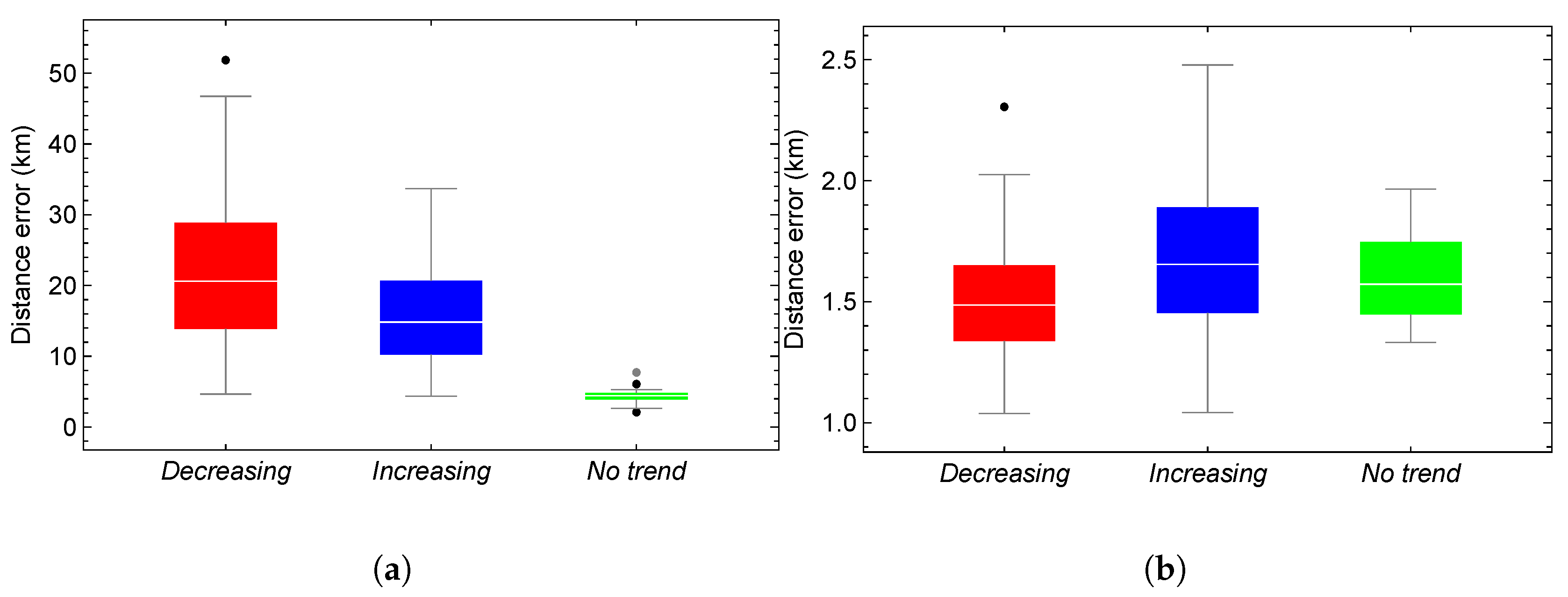

over a 15-day propagation span. These time series can be categorized into their trend into three groups based on their trend characteristics. The first two groups exhibit a trend component, which may increase or decrease over time, a seasonal component, and irregular data variance. In contrast, the third group lacks a discernible trend but displays pronounced seasonal components. The periods of the seasonal components, determined using autocorrelation functions (ACF) and periodograms, are approximately equal to the duration of a satellite revolution, about 14 hours. The number of time series with positive, negative, and no trends is 169, 118, and 26, respectively.

Figure 5 shows the box-and-whisker plots of the distance error between AIDA and SGP4 and between AIDA and the optimum HSGP4 based on modelling only the variable

. As shown, the greater the trend, the more significant the reduction in error provided by the hybrid model. On the other hand, for time series without trend, the potential for reducing error is lower, as SGP4’s initial error is small.

To summarize, this analysis shows that the argument of the latitude is an excellent candidate for modeling the evolution of their errors, thus constituting the best compromise between accuracy and simplicity.

3.4. Predictive Technique: Artificial Neural Network

Artificial neural networks (ANNs) are used as a predictive technique to hybridize SGP4. ANNs can model residual dynamics not captured by the analytical formulation of SGP4. By learning temporal patterns in propagation errors from TLEs, ANNs can approximate the unmodeled effects and uncertainties of SGP4. This data-driven correction enhances accuracy while maintaining the efficiency and interpretability of the analytical model.

The hybrid propagator increases its computational cost with the time required by the predictive part. In this case, the neural network’s predictions result from a sequence of matrix multiplications and nonlinear transformations. For a given input vector, each layer computes a weighted sum by multiplying the input by a weight matrix and adding a bias vector. The output is then processed by an activation function, which serves as the input for the subsequent layer. This procedure continues through each layer until the final output is produced, representing the model’s prediction. It is worth noting that the network weights, biases, and architectural configuration are embedded in the HTLE, enabling the predictive correction to be applied directly during propagation.

4. Artificial Neural Network Model Architectures

The performance of the ANN depends, among other factors, on its architecture, which is defined by a set of hyperparameters [

30,

40,

41]. Based on the results obtained, 7 hyperparameters were selected for tuning: the batch size (

), the number of hidden layers (

), the number of neurons in the first hidden layer (

), the activation function (

), the optimizer (

o), the loss function (

), and the learning rate (

).

Table 1 summarizes the range of values considered for each hyperparameter. From the second hidden layer onward, the number of neurons is fixed at half that of the preceding layer.

In the scenario considered in

Table 1, the total number of ANN architectures with one hidden layer is 1536, while 6144 and 24576 with two and three hidden layers, respectively. This results in a total of 32256 possible architectures. The input layer has 169 neurons, which corresponds to approximately two satellite revolutions. The datasets for training, testing, and validation span approximately 7, 3, and 14 satellite revolutions, respectively. These values were previously established in Reference [

41].

An experimental strategy was implemented to reduce the number of architectures under consideration. The approach began with selecting the loss function and the number of hidden layers. After these parameters were established, the optimal values for the remaining hyperparameters were identified. For all experiments, the number of epochs was fixed at 500, and early stopping with a patience parameter of 60 was applied. Each experiment was repeated 10 times for each architecture. The nonparametric k-sample test was employed to validate the selection process by determining whether performance differences among candidate architectures were statistically significant. The experiments utilized the Python packages TensorFlow, Matplotlib, Scikit-learn, Pandas, NumPy, Itertools, Statsmodels, Subprocess, Random, and Json. The high number of independent repetitions was facilitated by the University of La Rioja’s high-performance computing center (Beronia).

4.1. 7-D Hyperparameter Space

This section determines the most suitable loss function, the optimal number of hidden layers, and the learning rate, thereby reducing the hyperparameter space to four dimensions.

4.1.1. Loss Function

The initial experiment is designed to select a suitable loss function. The considered functions are the

mse,

mae,

mape, and

msle as shown in

Table 1. Once this parameter is set, the hyperparameter space is reduced to 6-D, and the total number of architectures to try with each loss function is 8,064. In this case, the number of architectures with 1, 2, and 3 hidden layers is 384, 1536, and 6144, respectively.

To reduce the number of executions, probabilistic random sampling stratified by the number of hidden layers was employed, with a 5% margin of error and a 95% confidence level. The obtained architectures are 366 (one hidden layer), 17 (two hidden layers), and 279 (three hidden layers). Next, the 366 architectures are trained and tested using six of the 313 available time series

, two with a positive trend, two with a negative trend, and two with no trend, generating a total of 2196 architectures for each of the four loss functions.

Figure 6 shows the six selected time series. Each model takes 2 satellite revolutions as input and is trained, validated, and tested using 7, 3, and 14 satellite revolutions, respectively. In contrast, its performance is measured by comparing the RSME error between the time series

and its prediction

.

For each time series, the model with the lowest RMSE during training and testing is selected.

Table 2 shows the number of models according to the loss function. As shown, the best-performing loss functions during training are

mse and

mape, with similar percentages. The loss functions

mse and

mape exhibit comparable performance during training, approximately 35% and 38%, respectively. In contrast,

mape achieves the highest performance during testing, reaching nearly 40%, whereas

mse decreases to 26%. The nonparametric k-sample test assesses whether improvements in RMSE are attributable to the choice of loss function.

To determine whether statistically significant differences exist among the evaluated loss functions (mae, mape, mse, and msle), and particularly between mape and mse, a chi-square test for proportions was conducted. This nonparametric test assesses whether the observed differences in the performance of the loss functions are attributable to chance or represent real differences, by testing the null hypothesis that all functions produce equivalent results against the alternative hypothesis that significant differences exist in their performance. The results indicate statistically significant differences (

for training,

for testing, both with

). Subsequently, the accuracy of these models when integrated into the hybrid propagator was evaluated.

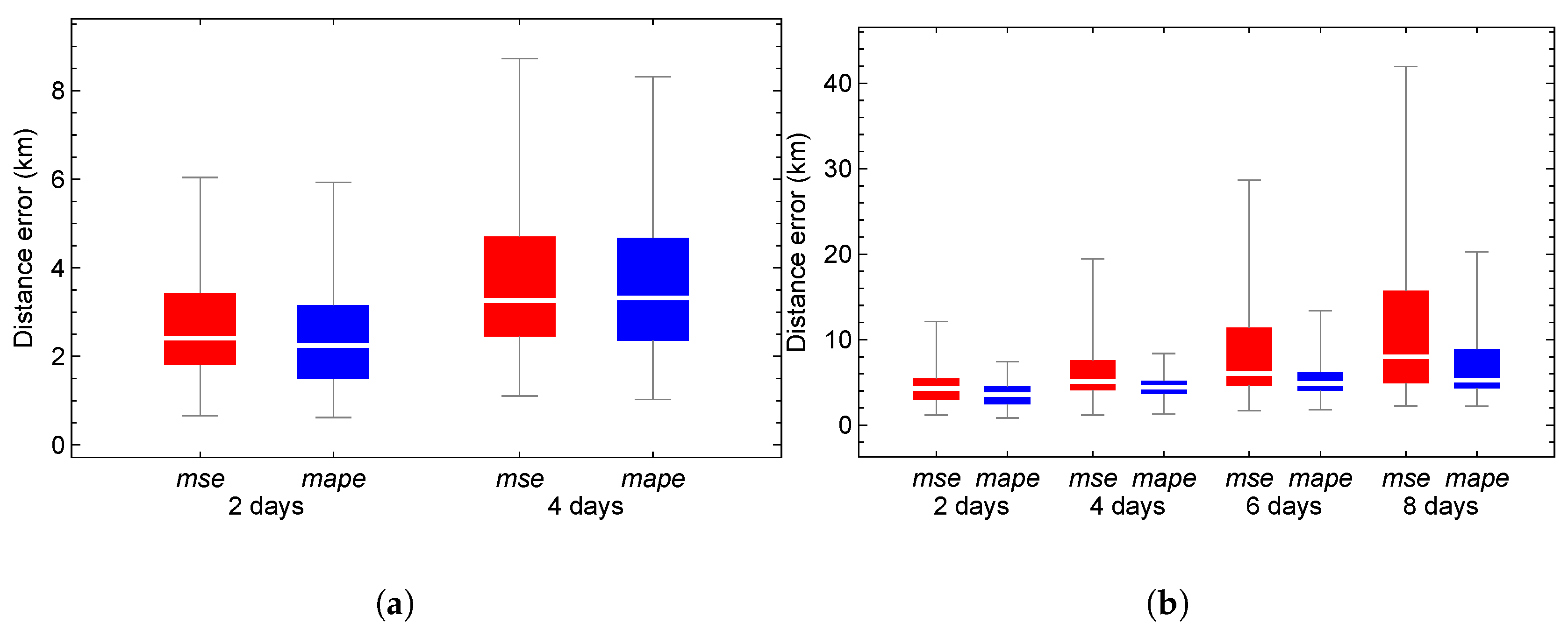

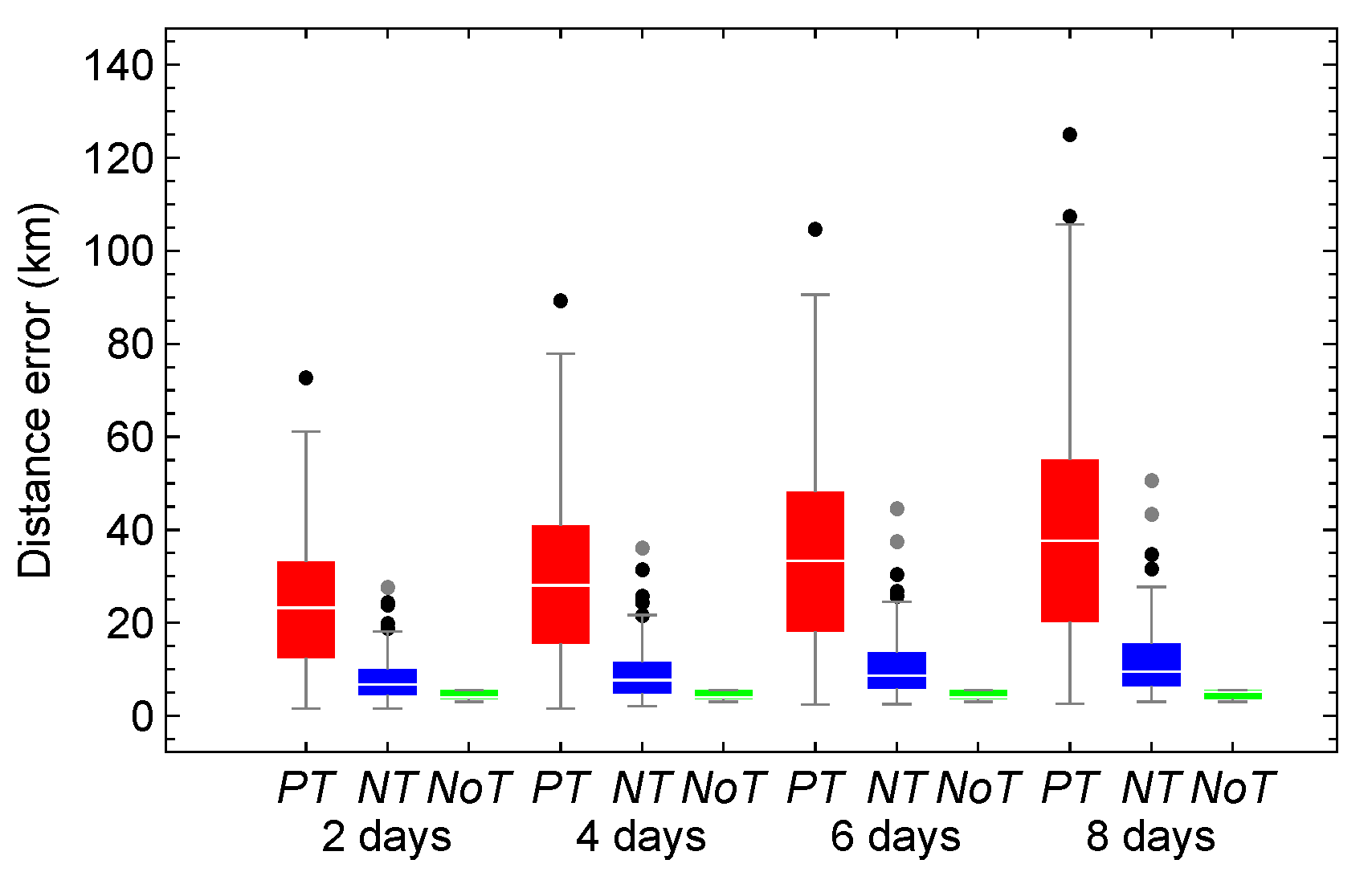

Figure 7 presents box-and-whisker plots of the distance error between the numerical propagator and the family of HSGP4 propagators that use forecasting models with

mse (red) and

mape (blue) loss functions. The analysis covers both the training and testing stages, with outliers removed.

Figure 7 (a) displays the training stage. The percentages of outliers for models with

mse and

mape at 2 and 4 days are 11.11% and 10.99%, respectively, and 9.10% and 9.49%, respectively. Although the error distributions are similar, the third quartile value for

mape is lower than that for

mse. Additionally, the percentage of outliers is lower for

mape, indicating reduced variability.

Figure 7 (b) illustrates the testing stage. The percentages of outliers for

mse and

mape at 2, 4, 6, and 8 days are 14.97%, 17.73%, 19.10%, and 20.14%, and 7.39%, 13.75%, 10.68%, and 11.02%, respectively. In this experiment, errors obtained using the

mape loss function are lower, exhibit less variability, and have an extreme value rate nearly 50% lower compared to errors from the

mse loss function. Based on these results,

mape is selected as the preferred loss function.

4.1.2. Optimum Number of Hidden Layers

After fixing the loss function, 2196 models trained with mape are analyzed to identify the optimal number of hidden layers. This study looks to identify the optimum number of hidden layers. Distance error serves as the primary metric for this selection, after 8 days in the test set. The experiment shows that in 1405 of the 2196 cases, about 63.98% of the time, the error in HSGP4 is lower than that in SGP4.

Table 3 presents the number of cases and the average computational time for training models where the distance error in HSGP4 is lower than that in SGP4. As the number of hidden layers increases, the proportion of models that improve also increases. In particular, the percentage of improved models increases by 23.52% from one to two hidden layers and by 8.22% from two to three hidden layers. A chi-square test indicates that these differences are statistically significant (

,

,

), thereby rejecting the hypothesis that improvement proportions are equal across all hidden layer configurations and demonstrating that model performance is influenced by the number of hidden layers. The average computation time per model also increases proportionally with the number of hidden layers.

This result confirms that increasing the number of hidden layers enhances model performance but also increases complexity and computational demand. Based on this result, two hidden layers are selected as the optimal configuration.

4.1.3. Optimal Learning Rate Value

At this point, mape has been established as the optimal value of the loss function, and two hidden layers have been identified as optimal, reducing the number of possible architectures to 1536. However, among the hyperparameters that define such architectures, the optimizer is relevant and depends on another hyperparameter, the learning rate, a continuous parameter that complicates the search for an optimal value. In this analysis, three learning rate values are considered: the default value 1e-4, a higher value 1e-3, and a lower value 1e-5. Training a model for each of the 1536 architectures with all three learning rates is computationally intensive. Therefore, a stratified random sampling with uniform allocation is employed, of architectures is drawn, with sub-samples of size for each optimizer, where . These randomly selected architectures are then trained, validated, and evaluated on six time series, resulting in models. Each of these 1848 models is trained with the three learning rates, and the model with the smallest distance error among the three rates is selected for both the training set (to assess reproducibility) and the test set (to evaluate forecasting performance).

Table 4 presents the proportion of instances in which each learning rate produced the smallest error in distance at 4 days in the training set and at 8 days in the test set.

The results demonstrate that, within the training set, higher learning rates are associated with lower performance. In contrast, in the test set, the two highest learning rates yield similar and superior performance. The chi-square test produces a statistic of , which exceeds the critical value (with 3 degrees of freedom and ), thereby confirming that the association between the learning rate (lr) and the proportion of models with lower error is statistically significant. Since lr=1e-4 achieves the highest performance in the test set (42.97%) and demonstrates consistency across both sets, it is identified as the optimal learning rate.

4.2. 4-D Hyper-Parameter Space

The

mape is set as the loss function, two hidden layers are selected as optimal, and the learning rate is set to 1e-4. This choice reduces the hyperparameter space to four dimensions and limits the number of possible architectures to 1536, although a substantial number of configurations remain. This section aims to identify the architectures with the best performance among the six time series described in

Figure 6, followed by an analysis of their behavior across the remaining 313 time series. Two satellite revolutions are again used as input, whereas 7, 3, and 14 samples are allocated to the training, validation, and test sets, respectively. The input layer comprises 169 neurons, and training is conducted for a maximum of 500 epochs with a patience parameter of 60. Each architecture is trained ten times and incorporates the predicted values of

within the hybrid module of HSGP4. The selected model is the one that minimizes the average distance error between the numerical propagator and HSGP4 at 3 and 7 satellite revolutions, corresponding to approximately 2 and 4 propagation days, respectively.

4.2.1. First Reduction of Architectures

After training 1536 architectures on the six time series, their test set predictions are incorporated into HSGP4. The distance error between the numerical propagator and HSGP4 is then calculated at 2, 4, 6, and 8 days. The top five models for each time series are subsequently selected and ranked by increasing distance error after eight days of propagation.

Table 5 presents these results. The first column indicates the ranking, while columns two through six specify the batch size, the number of neurons in the first hidden layer, the optimizer, and the activation functions for the first and second hidden layers for each architecture. The final column shows the frequency with which each architecture appears.

The most frequently observed parameter combination consists of a batch size of 256, 16 neurons in the first layer, 8 and 4 neurons in the second and third layers, respectively, the Adam optimizer, and (tanh, elu) as activation functions for the first and second hidden layers. This configuration is closely followed by the (relu, elu) and (linear, linear) combinations. Notably, only architecture 1 yielded two time series whose models, when trained with this configuration, were among the best-performing. The remaining architectures were included among the top five in only one of the six trained time series.

Figure 8 presents box-and-whisker plots of the distance error between the numerical propagator and HSGP4, which were used to select the architectures in

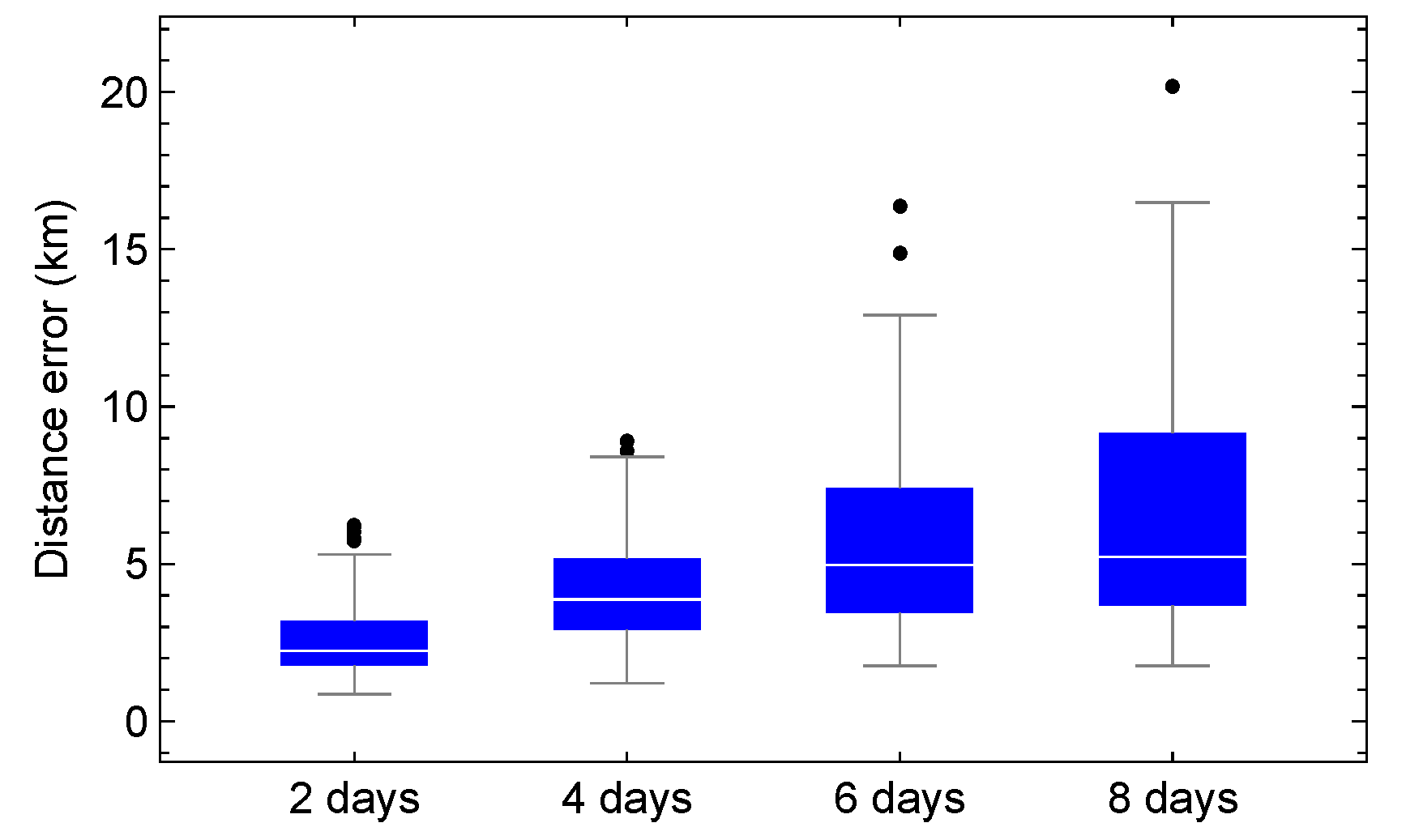

Table 5. These results also show improvements in the distance error between the numerical propagator and SGP4 after 2, 4, 6, and 8 days in the test set. Of 313 cases, 174 show improved SGP4 distance errors at each propagation interval. There are 58 time series with positive, negative, or no trend.

Table 6 presents the number of modes that improve SGP4 error, categorized by time series trend. Without considering the trend, the improvement after 8 days reaches 81%. For architectures applied to series without a trend, this value decreases, with only approximately 76% of SGP4 errors improving when using the hybrid model. In contrast, series exhibiting a positive trend demonstrate an improvement of about 88% at 8 days, and consistent improvement is observed at shorter time horizons (2 and 4 days).

4.2.2. Select the Best Three Architectures

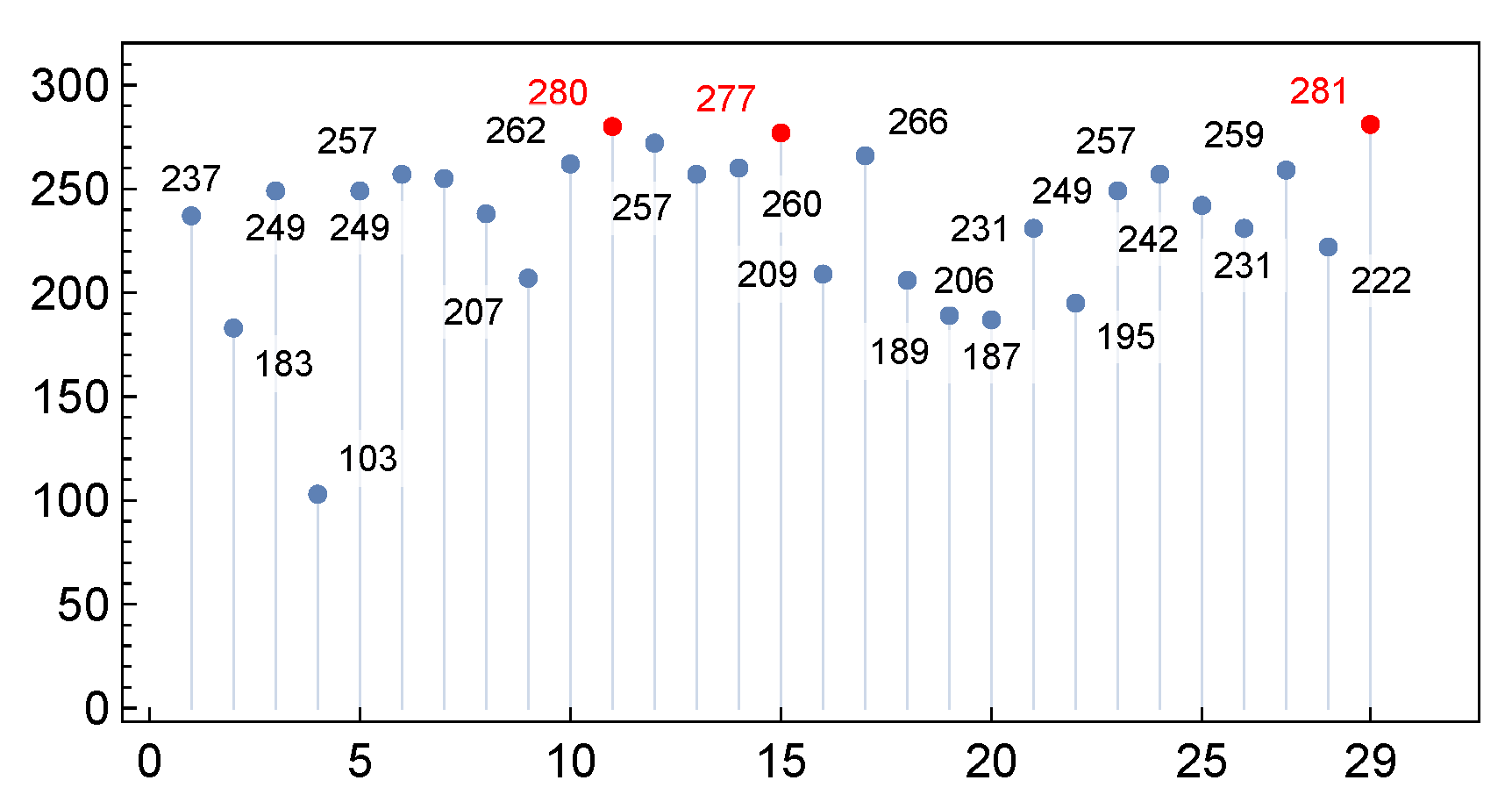

The process of reducing architectures is ongoing. Each of the 29 architectures is trained on the 313 time series in this study, yielding a total of 9077 models.

After 8 days of propagation, 6810 models exhibit lower distance errors between the numerical propagator and HSGP4 than between the numerical propagator and SGP4. This accounts for 75.02% of the total models generated.

Figure 9 presents the number of models in which the HSGP4 error is lower than the SGP4 error for each architecture. Notably, 15 out of 29 architectures surpass the 75% improvement threshold. The architectures highlighted in red (11, 15, and 29) demonstrate the highest proportion of series with reduced distance error when the hybrid model is applied.

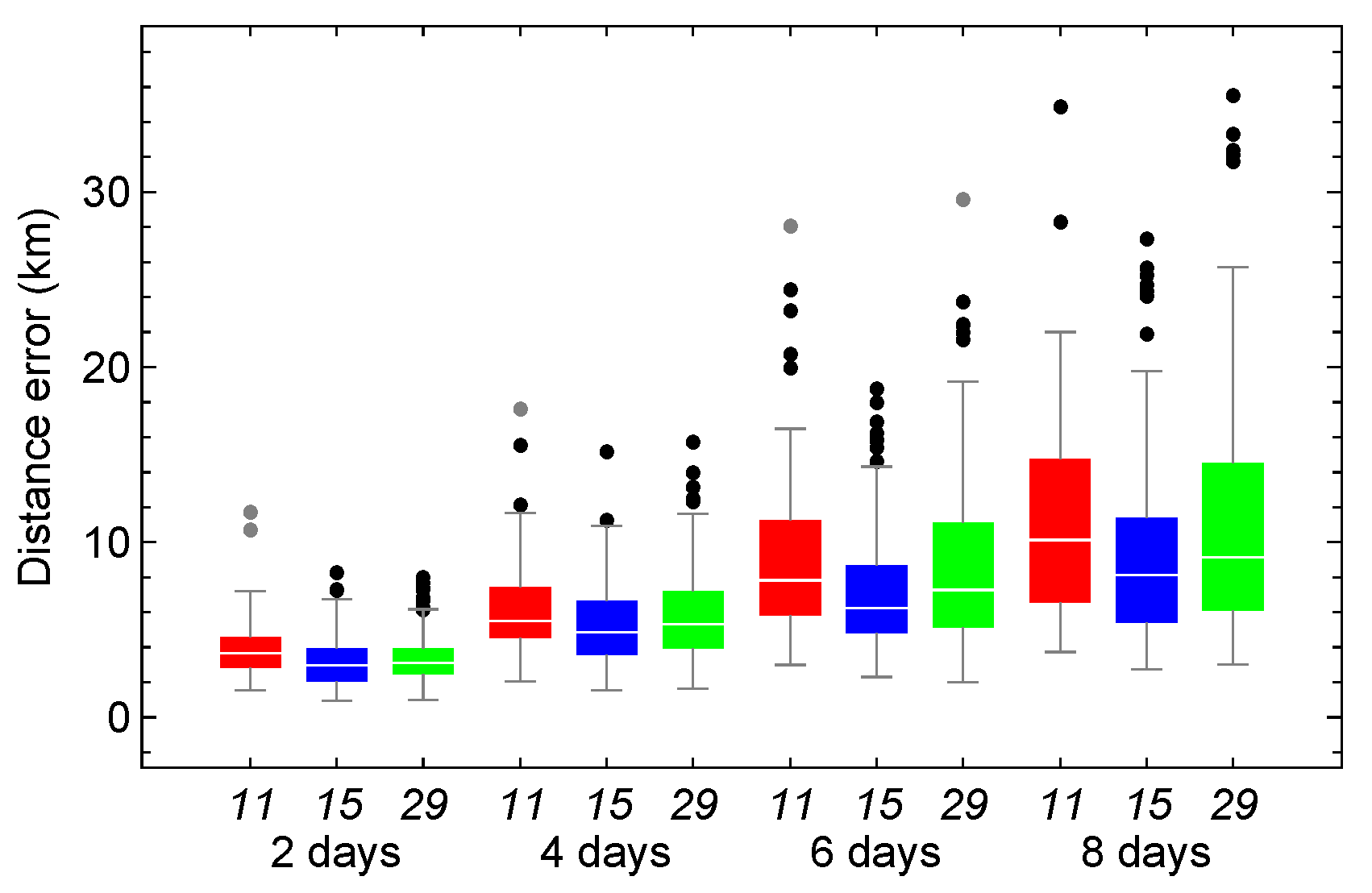

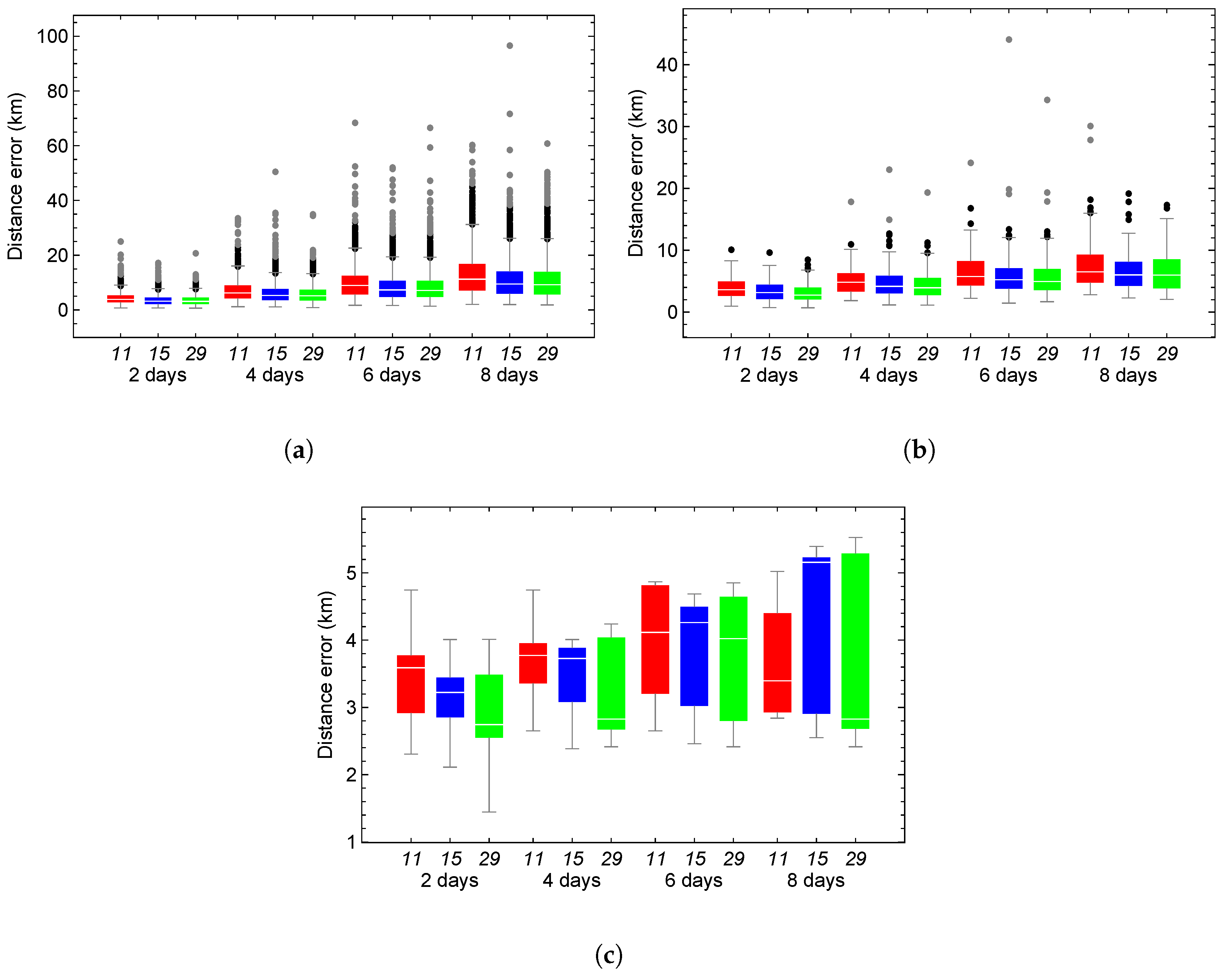

Figure 11,

Figure 12 and

Figure 13 show box-and-whisker plots of the distance error between the numerical and HSGP4 propagators. These plots utilize models trained with architectures 11 (red), 15 (blue), and 29 (green), whose hyperparameters are detailed in

Table 5. The models also demonstrate improved distance error between the numerical propagator and SGP4 after 2, 4, 6, and 8 days in the test set. The three plots are categorized as positive, negative, and non-trend. The time series counts for positive, negative, and non-trend categories are 169, 118, and 26, respectively.

Table 7 summarizes the number of cases, grouped by trend category and network architecture, in which the error produced by HSGP4 exceeds that of SGP4 for different propagation horizons. For time series exhibiting a positive trend, architectures 11 and 29 show a clear increase in the number of cases where HSGP4 performs worse as the propagation time increases, particularly at 8 days. Architecture 15, while initially showing fewer cases, also shows a gradual increase with longer predictive horizons.

In the negative trend category, architecture 11 consistently presents the highest number of cases across all time intervals, indicating a pronounced degradation of HSGP4 performance relative to SGP4 for this trend type. Architectures 15 and 29 display lower overall counts but still show a noticeable increase in error dominance as the propagation interval increases. For non-trend time series, the number of cases remains relatively stable across all architectures and propagation times. This suggests that, in the absence of a clear trend, the relative performance of HSGP4 compared to SGP4 is less sensitive to the predictive horizon.

Overall, the results indicate that the likelihood of HSGP4 exhibiting larger errors than SGP4 increases with propagation time, particularly for time series with pronounced positive or negative trends. This behavior is architecture-dependent, with certain configurations being more sensitive to trend characteristics than others.

Figure 10 shows how distance errors between the numerical propagator and SGP4 evolve over 2, 4, 6, and 8 days for the test set, grouped by positive, negative, and nontrend trends. A systematic increase in both median distance error and dispersion is observed across all categories. Time series with positive or negative trends exhibit larger errors and greater variability than non-trending cases. In contrast, the nontrend group maintains consistently low and stable errors, indicating greater robustness.

Figure 11 presents the results for the time series exhibiting a positive trend. Training the time series with architecture 15 reduces the distance error of the HSGP4 in 138 cases, corresponding to approximately 82%. Architectures 11 and 29 achieve reductions in 133 cases, or about 79%, for a combined total of 169. The errors associated with the three selected architectures are comparable during the initial four days of propagation. Over the subsequent four days, the error for architecture 15 increases at a slower rate than that for architectures 11 and 29. The 75th percentile error for architecture 15 is approximately 10.29 km, while architectures 11 and 29 yield errors of 14.30 km and 13.11 km, respectively. In the worst-case scenario, at eight days, the maximum error for architecture 15 is 27.41 km, compared to 34.97 km and 35.62 km for architectures 11 and 29, respectively.

Figure 12 shows the results for the time series with a negative trend. Architecture 11 performed best, with 88 out of 118 cases, or approximately 75%. Error rates for the three selected architectures remained similar throughout all propagation days. The 75th percentile errors for architectures 11, 15, and 29 were approximately 11.82, 12.33, and 11.43 km, respectively. At 8 days, the maximum error was 20.57 km for architecture 15, 23.02 km for architecture 11, and 28.36 km for architecture 29.

Figure 13 presents the results for the time series without trend. This scenario demonstrates the lowest performance among the three architectures, as only approximately 24% of models improve the distance error of SGP4 in the best case and 17% in the worst case at 8 propagation days.

The time series exhibiting the smallest distance error among the models generated with the three selected architectures is chosen, and the

forecasts are graphically displayed alongside their corresponding real values.

Figure 14 presents the time series in black, while the series predicted by models parameterized with architectures 11, 15, and 29 are shown in blue, green, and red, respectively. The inputs used for forecasting in both the training and test sets are omitted; these inputs correspond to two satellite revolutions.

The model trained with architecture 15 (green) generates predictions closer to the true data than the other two architectures, in both the training and test sets. In contrast, the predictions made with the models using architectures 11 and 29, represented in blue and red, respectively, show that, capture the overall trend but fail to accurately reflect the variations.

The HSGP4 configuration with architecture 15 produces a distance error of approximately 2.75 km, which is close to the optimal error of 2.13 km. This architecture provides a significant improvement over the SGP4 error of 22.04 km and the HSGP4 propagators with architectures 11 and 29, which exhibit errors of 19.41 km and 12.51 km, respectively. Therefore, architecture 15 can be considered a near-optimal solution for minimizing distance error relative to the numerical propagator within this time series.

The characteristics of the three selected architectures are presented in

Table 8.

5. Analysis of the HSGP4 Based on the Architectures 11, 15, and 29

The three architectures will be evaluated using a dataset of 1683 Two-Line Elements (TLEs) from a new Galileo satellite (NORA ID 38857). The TLEs span from October 12, 2012, to March 13, 2021. The semi-major axis values range from to km, with a concentration near km. Eccentricities vary from to , and inclination values are approximately . The argument of perigee ranges from to , while the right ascension of the ascending node varies between and .

Time series

are generated from the TLEs and classified into positive, negative, and non-trend categories, with respective counts of 1447, 227, and 9.

Table 9 summarizes, by trend category and network architecture, the number of cases in which the error produced by HSGP4 exceeds that of SGP4 for propagation horizons ranging from 2 to 8 days.

The results are consistent with those reported in

Table 7, showing a systematic increase in the number of such cases as the propagation horizon increases across all architectures and trend categories. In the first dataset, positive-trend series account for the majority of cases (169 out of 313 total). This behaviour becomes more pronounced in the second dataset, where positive-trend series account for the largest share and exhibit a nearly monotonic increase with propagation time across all architectures.

Negative-trend series display a similar but less pronounced growth pattern, with counts remaining consistently lower than those in positive-trend series in both experiments. In contrast, non-trend series yield the fewest cases, with near-zero counts in the second dataset even at the longest predictive horizon. Overall, architectural effects are secondary and less consistent than the influence of propagation time and trend classification.

Figure 15 shows the distance error between the numerical propagator and SGP4 over predictive horizons of 2, 4, 6, and 8 days for the test set, categorized as positive, negative, and nontrend cases. In all categories, the median distance error and its dispersion systematically increase, with errors exceeding 100 km at longer horizons.

Figure 10 presents a comparable pattern; however, in this instance, the distance error remains below 50 km for all predictive horizons.

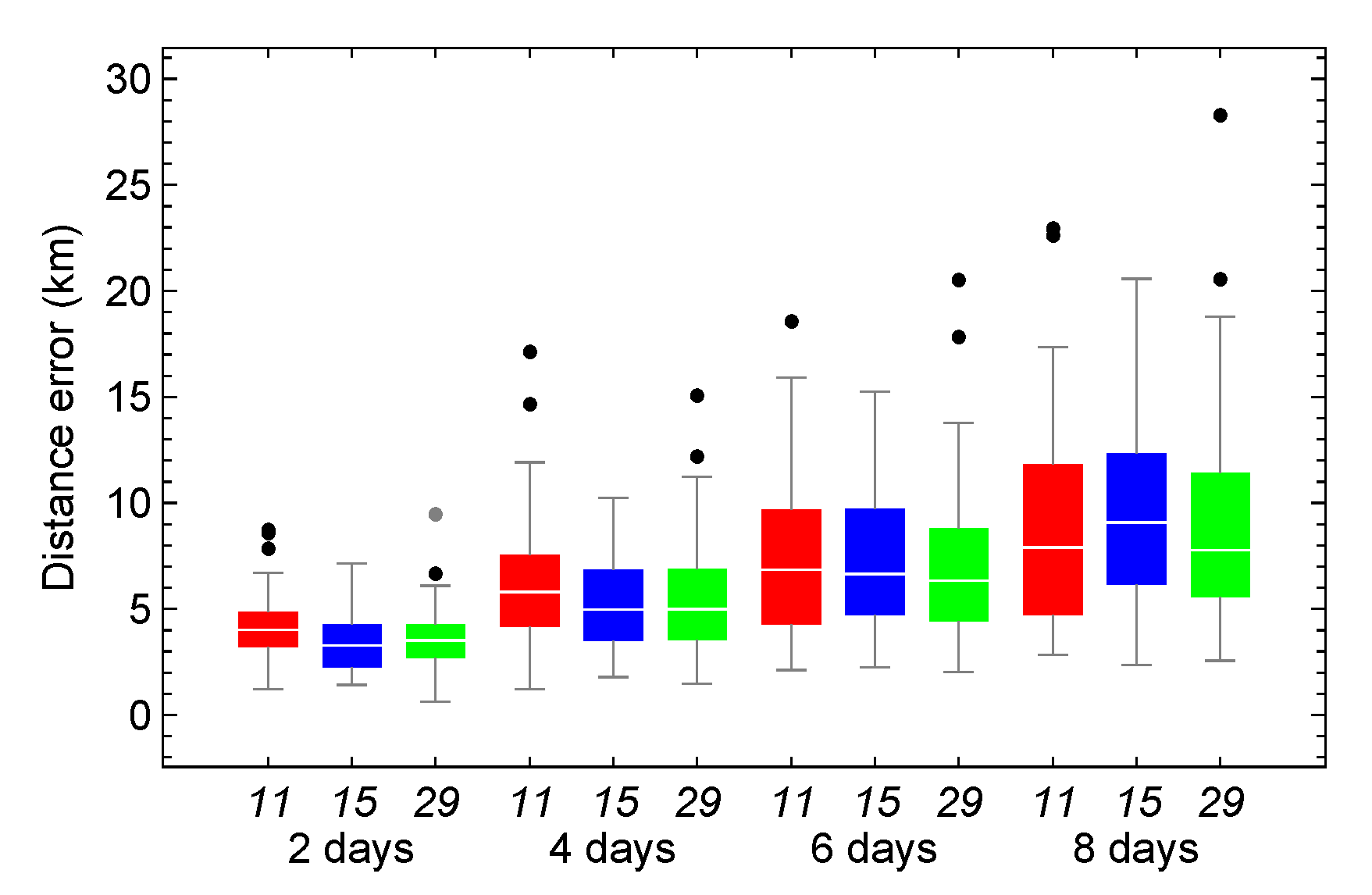

Figure 16 presents box-and-whisker plots of the distance error between the numerical and HSGP4 propagators. The plots use models trained with architectures 11 (red), 15 (blue), and 29 (green), with hyperparameters listed in

Table 8. These models show improved distance error between the numerical propagator and SGP4 after 2, 4, 6, and 8 days in the test set. Firstly, it can be observed that the distance errors produced by the three hybrid models show highly similar distributions, characterized by notable symmetry and closely aligned statistics (

, median,

, and upper whisker).

After eight days of propagation, the series with an increasing trend exhibited maximum distance errors approximately 77 km lower than those of SGP4 and 30 km higher than those of the optimal hybrid propagator. For series with decreasing trends, the maximum errors improved by about 10 km compared to SGP4, but were 17 km higher than the optimum. In series without a trend, the maximum errors of the three hybrid propagators did not improve; instead, they increased relative to SGP4 by approximately 7 km.

The errors suggest that the three architectures exhibit similar behavior across both increasing and decreasing trends, as illustrated in

Figure 11 and

Figure 12 for the Galileo NORA ID 40545. In contrast,

Figure 16 (a) and (b) reveal a substantially greater number of outliers, especially for positive trends. Despite this, the overall distribution shape is maintained and the statistical values remain comparable. On the contrary, in the absence of a trend, the series loses its shape, and the statistical values are no longer comparable.

Figure 1.

Scatter diagrams for the Galileo TLEs in the two-dimensional parameter planes: (a) Galileo TLEs in the -Plane. (b) Galileo TLEs in the -Plane. (c) Galileo TLEs in the -Plane. (d) Galileo TLEs in the -Plane.

Figure 1.

Scatter diagrams for the Galileo TLEs in the two-dimensional parameter planes: (a) Galileo TLEs in the -Plane. (b) Galileo TLEs in the -Plane. (c) Galileo TLEs in the -Plane. (d) Galileo TLEs in the -Plane.

Figure 2.

Box-and-whisker plots showing the distance errors (km) of the best combinations of orbital variables for a time span of 30 days.

Figure 2.

Box-and-whisker plots showing the distance errors (km) of the best combinations of orbital variables for a time span of 30 days.

Figure 3.

Box-and-whisker plots showing the distance errors (km) of the best combinations of Hill variables for a time span of 30 days.

Figure 3.

Box-and-whisker plots showing the distance errors (km) of the best combinations of Hill variables for a time span of 30 days.

Figure 4.

Plot 50 of the 313 time series .

Figure 4.

Plot 50 of the 313 time series .

Figure 5.

Box-and-whisker plots showing distance errors (km) over a 30-day period. The ephemeris of the HSGP4 is simulated by replacing the argument of the latitude of SGP4 with the argument of the latitude of AIDA. (a) SGP4. (b) HSGP4 based on .

Figure 5.

Box-and-whisker plots showing distance errors (km) over a 30-day period. The ephemeris of the HSGP4 is simulated by replacing the argument of the latitude of SGP4 with the argument of the latitude of AIDA. (a) SGP4. (b) HSGP4 based on .

Figure 6.

Six time series. The orange dots represent the input vector; in red, the training set; in green, the validation set; and in blue, the test set.

Figure 6.

Six time series. The orange dots represent the input vector; in red, the training set; in green, the validation set; and in blue, the test set.

Figure 7.

Box-and-whisker plots of the distance error for the models using the mse (red) and mape (blue) loss functions at 2 and 4 days in the training stage and at 2, 4, 6, and 8 days in the testing stage.

Figure 7.

Box-and-whisker plots of the distance error for the models using the mse (red) and mape (blue) loss functions at 2 and 4 days in the training stage and at 2, 4, 6, and 8 days in the testing stage.

Figure 8.

Box-and-whisker plots of the distance error between the numerical propagator and HSGP4 were used to select the architectures presented in

Table 5 and to reduce the distance error between the numerical propagator and SGP4.

Figure 8.

Box-and-whisker plots of the distance error between the numerical propagator and HSGP4 were used to select the architectures presented in

Table 5 and to reduce the distance error between the numerical propagator and SGP4.

Figure 9.

Number of models for which the HSGP4 distance error is lower than the SGP4 distance error after 8 days of propagation.

Figure 9.

Number of models for which the HSGP4 distance error is lower than the SGP4 distance error after 8 days of propagation.

Figure 10.

Box-and-whisker plots of the distance error between the numerical and SGP4 propagators for the time series positive (PT, red), negative (NT, blue), or non-trend (NoT, green).

Figure 10.

Box-and-whisker plots of the distance error between the numerical and SGP4 propagators for the time series positive (PT, red), negative (NT, blue), or non-trend (NoT, green).

Figure 11.

Box-and-whisker plots of the distance error between the numerical and HSGP4 propagators, using models trained with architectures 11 (red), 15 (blue), and 29 (green) under a positive trend.

Figure 11.

Box-and-whisker plots of the distance error between the numerical and HSGP4 propagators, using models trained with architectures 11 (red), 15 (blue), and 29 (green) under a positive trend.

Figure 12.

Box-and-whisker plots of the distance error between the numerical and HSGP4 propagators, using models trained with architectures 11 (red), 15 (blue), and 29 (green) under a negative trend.

Figure 12.

Box-and-whisker plots of the distance error between the numerical and HSGP4 propagators, using models trained with architectures 11 (red), 15 (blue), and 29 (green) under a negative trend.

Figure 13.

Box-and-whisker plots of the distance error between the numerical and HSGP4 propagators, using models trained with architectures 11 (red), 15 (blue), and 29 (green) under a positive non-trend.

Figure 13.

Box-and-whisker plots of the distance error between the numerical and HSGP4 propagators, using models trained with architectures 11 (red), 15 (blue), and 29 (green) under a positive non-trend.

Figure 14.

The real values are shown in black. Predicted values are generated by models using architectures 11 (blue), 15 (green), and 29 (red).

Figure 14.

The real values are shown in black. Predicted values are generated by models using architectures 11 (blue), 15 (green), and 29 (red).

Figure 15.

Box-and-whisker plots of the distance error between the numerical and SGP4 propagators for the time series positive (PT, red), negative (NT, blue), or non-trend (NoT, green).

Figure 15.

Box-and-whisker plots of the distance error between the numerical and SGP4 propagators for the time series positive (PT, red), negative (NT, blue), or non-trend (NoT, green).

Figure 16.

Box-and-whisker plots of the distance error between the numerical and HSGP4 propagators, using models trained with architectures 11 (red), 15 (blue), and 29 (green). (a) Positive trend. (b) Negative trend. (c) Non-trend.

Figure 16.

Box-and-whisker plots of the distance error between the numerical and HSGP4 propagators, using models trained with architectures 11 (red), 15 (blue), and 29 (green). (a) Positive trend. (b) Negative trend. (c) Non-trend.

Table 1.

7-D hyper-parameter space () with their considered values. The activation functions considered are Linear, hyperbolic tangent (tanh), Rectified Linear Unit (relu), and Exponential Linear Unit (elu). The optimizers considered are Root Mean Square Prop (rmsprop), Adaptive Delta (adadelta), Adaptive Moment Estimation (adam), and Nesterov-accelerated Adaptive Moment Estimation (nadam). The loss functions considered are the mean squared error (mse), mean absolute error (mae), mean absolute percentage error (mape) and mean square logarithmic error (msle).

Table 1.

7-D hyper-parameter space () with their considered values. The activation functions considered are Linear, hyperbolic tangent (tanh), Rectified Linear Unit (relu), and Exponential Linear Unit (elu). The optimizers considered are Root Mean Square Prop (rmsprop), Adaptive Delta (adadelta), Adaptive Moment Estimation (adam), and Nesterov-accelerated Adaptive Moment Estimation (nadam). The loss functions considered are the mean squared error (mse), mean absolute error (mae), mean absolute percentage error (mape) and mean square logarithmic error (msle).

| Hyperparameters |

Range of values |

| Batch size |

64, 128, 256, 512 |

| Hidden layers |

1, 2, 3 |

| Number of neurons in the first hidden layer |

8, 16, 32, 64, 128, 256 |

| Activation Functions |

linear, tanh, elu, relu

|

| Optimizers |

rmsprop, adadelta, adam, nadam

|

| Loss function |

mse, mae, mape, msle

|

| Learning rate |

0.001, 0.0001, 0.00001 |

Table 2.

Number of models with the lowest RMSE during training and testing.

Table 2.

Number of models with the lowest RMSE during training and testing.

| Architectures |

Training |

Testing |

| mae |

403 (18.35%) |

510 (23.22%) |

| mape |

780 (35.52%) |

880 (40.07%) |

| mse |

837 (38.12%) |

581 (26.46%) |

| msle |

176 3(8.01%) |

225 (10.25%) |

Table 3.

Number of models where the distance error of HSGP4 is less than the SGP4 error after 8 days in the testing set, and the average computational time of the training of the model. Of the 2,196 models, 102 have 1 hidden layer, 420 have 2 hidden layers, and 1,674 have 3 hidden layers.

Table 3.

Number of models where the distance error of HSGP4 is less than the SGP4 error after 8 days in the testing set, and the average computational time of the training of the model. Of the 2,196 models, 102 have 1 hidden layer, 420 have 2 hidden layers, and 1,674 have 3 hidden layers.

| Hidden layers |

Test |

Time (min) |

| 1 |

36 (35.29%) |

2.83 |

| 2 |

247 (58.81%) |

3.18 |

| 3 |

1122 (67.03%) |

3.60 |

Table 4.

Distribution of models chosen by the smallest error in distance, discriminated by learning rate value and by forecast set. The final column shows the median modeling time for each learning rate.

Table 4.

Distribution of models chosen by the smallest error in distance, discriminated by learning rate value and by forecast set. The final column shows the median modeling time for each learning rate.

| LR |

Train |

Test |

Median modelling time (sec) |

| 1e-05 |

817 (44.21%) |

290(15.69%) |

295.61 |

| 1e-04 |

647 (35.01%) |

794 (42.97%) |

267.92 |

| 1e-03 |

384 (20.78%) |

764 (41.34%) |

266.42 |

Table 5.

Best architectures that minimize the distance error after 8 propagation days.

Table 5.

Best architectures that minimize the distance error after 8 propagation days.

| Id |

BatchSize |

Neu First HL |

Optimizer |

ActFun1 |

AtFun2 |

Freq |

| 1 |

512 |

8 |

Nadam |

tanh |

elu |

2 |

| 2 |

256 |

8 |

Adam |

tanh |

elu |

1 |

| 3 |

64 |

256 |

Adam |

tanh |

tanh |

1 |

| 4 |

64 |

16 |

Adadelta |

relu |

elu |

1 |

| 5 |

128 |

256 |

Nadam |

relu |

elu |

1 |

| 6 |

256 |

64 |

Adam |

tanh |

tanh |

1 |

| 7 |

128 |

32 |

Nadam |

tanh |

elu |

1 |

| 8 |

128 |

16 |

Adam |

linear |

linear |

1 |

| 9 |

512 |

128 |

Nadam |

linear |

relu |

1 |

| 10 |

128 |

64 |

Adam |

elu |

tanh |

1 |

| 11 |

64 |

16 |

Rmsprop |

tanh |

elu |

1 |

| 12 |

256 |

128 |

Adam |

linear |

linear |

1 |

| 13 |

128 |

128 |

Adam |

tanh |

tanh |

1 |

| 14 |

256 |

128 |

Nadam |

linear |

elu |

1 |

| 15 |

256 |

64 |

Nadam |

linear |

tanh |

1 |

| 16 |

256 |

16 |

Adam |

elu |

elu |

1 |

| 17 |

512 |

128 |

Adam |

elu |

elu |

1 |

| 18 |

256 |

16 |

Adam |

linear |

linear |

1 |

| 19 |

512 |

16 |

Adam |

relu |

elu |

1 |

| 20 |

256 |

16 |

Adam |

tanh |

elu |

1 |

| 21 |

64 |

128 |

Nadam |

relu |

elu |

1 |

| 22 |

256 |

16 |

Nadam |

relu |

tanh |

1 |

| 23 |

64 |

16 |

Nadam |

linear |

elu |

1 |

| 24 |

256 |

256 |

Nadam |

linear |

linear |

1 |

| 25 |

64 |

256 |

Adam |

relu |

linear |

1 |

| 26 |

256 |

32 |

Adam |

elu |

elu |

1 |

| 27 |

64 |

64 |

Adam |

linear |

tanh |

1 |

| 28 |

256 |

32 |

Adam |

tanh |

linear |

1 |

| 29 |

256 |

32 |

Nadam |

linear |

tanh |

1 |

Table 6.

Number of methods reducing SGP4 error, grouped by time series trend.

Table 6.

Number of methods reducing SGP4 error, grouped by time series trend.

| Trend |

2 days |

4 days |

6 days |

8 days |

| Positive |

58 |

58 |

54 |

51 |

| Negative |

54 |

54 |

53 |

46 |

| Non-trend |

56 |

51 |

50 |

44 |

Table 7.

Number of cases for each architecture where the error associated with HSGP4 is greater than that of SGP4 for the Galileo satellite (NORA ID 40545). The number of positive, negative, and non-trend time series are 169, 118, and 26, respectively.

Table 7.

Number of cases for each architecture where the error associated with HSGP4 is greater than that of SGP4 for the Galileo satellite (NORA ID 40545). The number of positive, negative, and non-trend time series are 169, 118, and 26, respectively.

| Trend |

Architecture |

2 days |

4 days |

6 days |

8 days |

| Positive |

11 |

33 |

33 |

33 |

36 |

| |

15 |

20 |

24 |

30 |

31 |

| |

29 |

19 |

24 |

28 |

36 |

| Negative |

11 |

45 |

40 |

46 |

51 |

| |

15 |

20 |

22 |

27 |

30 |

| |

29 |

28 |

28 |

33 |

37 |

| Non-trend |

11 |

22 |

22 |

21 |

19 |

| |

15 |

17 |

20 |

19 |

19 |

| |

29 |

19 |

20 |

20 |

21 |

Table 8.

Each selected architecture contains two hidden layers, a learning rate of 1e-4, a linear activation function in the output layer, and uses the mape as the loss function.

Table 8.

Each selected architecture contains two hidden layers, a learning rate of 1e-4, a linear activation function in the output layer, and uses the mape as the loss function.

| Id |

BatchSize |

Nº Neu 1º HL |

Optimizer |

ActFun1 |

AtFun2 |

| 11 |

64 |

16 |

Rmsprop |

tanh |

elu |

| 15 |

256 |

64 |

Nadam |

linear |

tanh |

| 29 |

256 |

32 |

Nadam |

linear |

tanh |

Table 9.

Number of cases for each architecture where the error associated with HSGP4 is greater than that of SGP4 for the Galileo satellite (NORA ID 38857). The number of positive, negative, and non-trend time series are 1447, 227, and 9, respectively.

Table 9.

Number of cases for each architecture where the error associated with HSGP4 is greater than that of SGP4 for the Galileo satellite (NORA ID 38857). The number of positive, negative, and non-trend time series are 1447, 227, and 9, respectively.

| Trend |

Architecture |

2 days |

4 days |

6 days |

8 days |

| Positive |

11 |

15 |

40 |

60 |

90 |

| |

15 |

11 |

32 |

79 |

129 |

| |

29 |

14 |

32 |

68 |

138 |

| Negative |

11 |

19 |

27 |

34 |

41 |

| |

15 |

12 |

38 |

51 |

64 |

| |

29 |

16 |

38 |

53 |

65 |

| Non-trend |

11 |

0 |

1 |

2 |

5 |

| |

15 |

0 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

| |

29 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

4 |