Submitted:

04 January 2026

Posted:

06 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

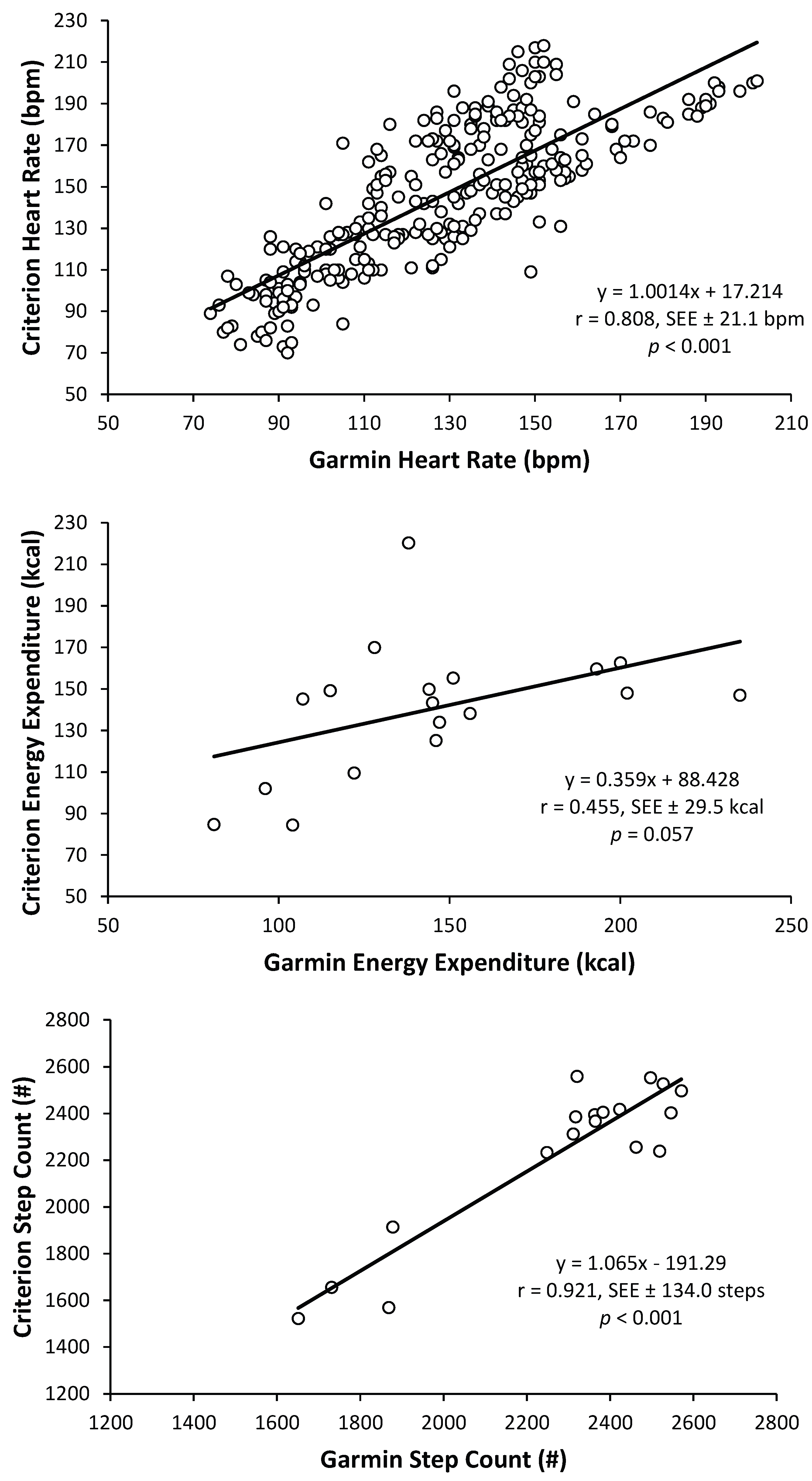

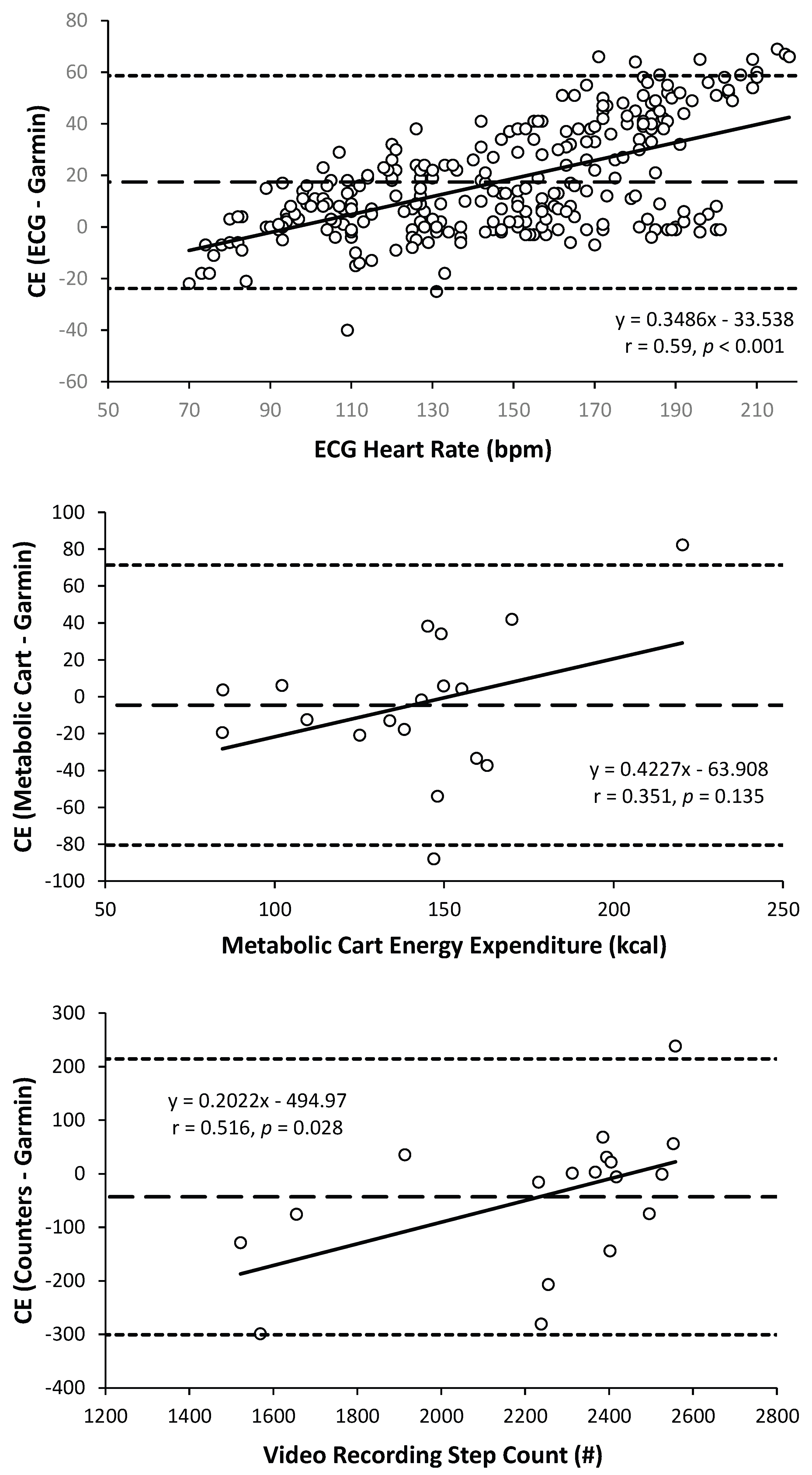

The purpose of this study was to examine the validity of a Garmin wrist-based device for estimating heart rate, energy expenditure, and step count during incremental treadmill exercise in college-aged individuals. Eighteen males and females (mean ± SD age = 23.2 ± 4.9 years) volunteered to complete an incremental treadmill test with the Garmin Vivoactive 4 device and criterion methods (electrocardiogram, indirect calorimetry, and video recording) measuring heart rate, energy expenditure, and step count. Mean absolute percent error (MAPE), simple linear regression, and Bland-Altman plots were used to assess accuracy. Acceptable accuracy was defined as MAPE < 5% for heart rate and < 10% for energy expenditure and step count. Statistical significance was set at α < 0.05. The MAPE (±SD) values were 13.0 (±10.1), 19.1 (±15.0), and 4.6 (±5.3)% for heart rate, energy expenditure, and step count, respectively. The Bland-Altman regression analyses illustrated proportional bias was present for estimations of heart rate (r = 0.591, p < 0.001) and step count (r = 0.516, p = 0.028), but not energy expenditure (r = 0.351, p = 0.153). These findings indicated that the Garmin Vivoactive 4 provided acceptable accuracy metrics for step count, but not heart rate or energy expenditure.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Subjects

2.2. Familiarization Session

2.3. Exercise Protocol

2.4. Garmin Watch

2.5. Criterion Measurements

2.5.1. Heart Rate

2.5.2. Energy Expenditure

2.5.3. Step Count

2.6. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Heart Rate

3.2. Energy Expenditure

3.3. Step Count

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PPG | Photoplethysmography |

| MAPE | Mean absolute percent error |

| ECG | Electrocardiogram |

| SEE | Standard error of estimate |

| CE | Constant error |

References

- McAvoy, C.; Batrakoulis, A.; Camhi, S.; Sansone, J.; Stanfield, J.; Reed, R. 2026 ACSM Worldwide Fitness Trends: Future Directions of the Health and Fitness Industry. ACSMʼs Health Fit. J. 2025, 29, 16–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, M.S.S.; Moore, K.; McGavigan, A.; Clark, R.A.; Ganesan, A.N. Effectiveness of Wearable Trackers on Physical Activity in Healthy Adults: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. JMIR MHealth UHealth 2020, 8, e15576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagappan, A.; Krasniansky, A.; Knowles, M. Patterns of Ownership and Usage of Wearable Devices in the United States, 2020-2022: Survey Study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2024, 26, e56504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wearable Technology Market Size | Industry Report, 2030. Available online: https://www.grandviewresearch.com/industry-analysis/wearable-technology-market (accessed on 27 December 2025).

- Navalta, J.W.; Montes, J.; Bodell, N.G.; Salatto, R.W.; Manning, J.W.; DeBeliso, M. Concurrent Heart Rate Validity of Wearable Technology Devices during Trail Running. PLOS ONE 2020, 15, e0238569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wearable Technology Market Size & Share 2035. Available online: https://www.businessresearchinsights.com/market-reports/wearable-technology-market-119131 (accessed on 27 December 2025).

- de Vries, H.J.; Kooiman, T.J.M.; van Ittersum, M.W.; van Brussel, M.; de Groot, M. Do Activity Monitors Increase Physical Activity in Adults with Overweight or Obesity? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Obesity 2016, 24, 2078–2091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, R.Z.U.; Chatterjee, M.; Manyakov, N.V.; Daans, M.; Jackson, A.; O’Brisky, A.; Telesky, T.; Smets, S.; Berghmans, P.-J.; Yang, D.; et al. Assessment of Physiological Signals from Photoplethysmography Sensors Compared to an Electrocardiogram Sensor: A Validation Study in Daily Life. Sensors 2024, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hibbing, P.R.; Pilla, M.; Birmingham, L.; Byrd, A.; Ndagijimana, T.; Sadeghi, S.; Seigfreid, N.; Farr, D.; Al-Shawwa, B.; Ingram, D.G.; et al. Evaluation of the Garmin Vivofit 4 for Assessing Sleep in Youth Experiencing Sleep Disturbances. Digit. Health 2024, 10, 20552076241277150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altini, M.; Penders, J.; Vullers, R.; Amft, O. Personalizing Energy Expenditure Estimation Using Physiological Signals Normalization during Activities of Daily Living. Physiol. Meas. 2014, 35, 1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Etiwy, M.; Akhrass, Z.; Gillinov, L.; Alashi, A.; Wang, R.; Blackburn, G.; Gillinov, S.M.; Phelan, D.; Gillinov, A.M.; Houghtaling, P.L.; et al. Accuracy of Wearable Heart Rate Monitors in Cardiac Rehabilitation. Cardiovasc. Diagn. Ther. 2019, 9, 26271–26271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakeri, I.; Adolph, A.L.; Puyau, M.R.; Vohra, F.A.; Butte, N.F. Application of Cross-Sectional Time Series Modeling for the Prediction of Energy Expenditure from Heart Rate and Accelerometry. J. Appl. Physiol. 2008, 104, 1665–1673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ainslie, P.N.; Reilly, T.; Westerterp, K.R. Estimating Human Energy Expenditure. Sports Med. 2003, 33, 683–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crouter, S.E.; Clowers, K.G.; Bassett, D.R. A Novel Method for Using Accelerometer Data to Predict Energy Expenditure. J. Appl. Physiol. 2006, 100, 1324–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, M.; Po, L.; Fu, H. Cuffless Blood Pressure Estimation Based on Photoplethysmography Signal and Its Second Derivative. Int. J. Comput. Theory Eng. 2017, 9, 202–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fine, I.; Kaminsky, A. Scattering-Driven PPG Signal Model. Biomed. Opt. Express 2022, 13, 2286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hettiarachchi, I.T.; Hanoun, S.; Nahavandi, D.; Nahavandi, S. Validation of Polar OH1 Optical Heart Rate Sensor for Moderate and High Intensity Physical Activities. PLOS ONE 2019, 14, e0217288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudreaux, B.D.; Hebert, E.P.; Hollander, D.B.; Williams, B.M.; Cormier, C.L.; Naquin, M.R.; Gillan, W.W.; Gusew, E.E.; Kraemer, R.R. Validity of Wearable Activity Monitors during Cycling and Resistance Exercise. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2018, 50, 624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Støve, M.P.; Haucke, E.; Nymann, M.L.; Sigurdsson, T.; Larsen, B.T. Accuracy of the Wearable Activity Tracker Garmin Forerunner 235 for the Assessment of Heart Rate during Rest and Activity. J. Sports Sci. 2019, 37, 895–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, S.; Wang, X.; Zhang, T.; Lei, S.M.; Cheng, S.; Yao, W.; Schumann, M. Validity of Three Smartwatches in Estimating Energy Expenditure during Outdoor Walking and Running. Front. Physiol. 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamieson, A.; Jones, S.; Chaturvedi, N.; Hughes, A.D.; Orini, M. Accuracy of Smartwatches for the Remote Assessment of Exercise Capacity. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 22994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Oost, C.N.; Masci, F.; Malisse, A.; Schyvens, A.-M.; Peters, B.; Dirix, H.; Ross, V.; Wets, G.; Neven, A.; Verbraecken, J.; et al. Accuracy of Heart Rate Measurement Under Transient States: A Validation Study of Wearables for Real-Life Monitoring. Sensors 2025, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahl, Y.; Düking, P.; Droszez, A.; Wahl, P.; Mester, J. Criterion-Validity of Commercially Available Physical Activity Tracker to Estimate Step Count, Covered Distance and Energy Expenditure during Sports Conditions. Front. Physiol. 2017, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunn, J.; Navalta, J.; Fountaine, C.; Reece, J. Current State of Commercial Wearable Technology in Physical Activity Monitoring 2015-2017. Int. J. Exerc. Sci. 2018, 11, 503–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doherty, C.; Baldwin, M.; Keogh, A.; Caulfield, B.; Argent, R. Keeping Pace with Wearables: A Living Umbrella Review of Systematic Reviews Evaluating the Accuracy of Consumer Wearable Technologies in Health Measurement. Sports Med. 2024, 54, 2907–2926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, L.; Konoval, T.; Bruce, L. An Examination of How and Why Triathlon Coaches Use a Suite of Technologies in Their Practice. Int. J. Sports Sci. Coach. 2023, 18, 687–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garber, C.E.; Blissmer, B.; Deschenes, M.R.; Franklin, B.A.; Lamonte, M.J.; Lee, I.-M.; Nieman, D.C.; Swain, D.P. Quantity and Quality of Exercise for Developing and Maintaining Cardiorespiratory, Musculoskeletal, and Neuromotor Fitness in Apparently Healthy Adults: Guidance for Prescribing Exercise. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2011, 43, 1334–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagim, A.R.; Koch-Gallup, N.; Camic, C.L.; Kroening, L.; Nolte, C.; Schroeder, C.; Gran, L.; Erickson, J.L. The Accuracy of Fitness Watches for the Measurement of Heart Rate and Energy Expenditure during Moderate Intensity Exercise. J. Sports Med. Phys. Fitness 2021, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora-Gonzalez, J.; Gould, Z.R.; Moore, C.C.; Aguiar, E.J.; Ducharme, S.W.; Schuna, J.M.; Barreira, T.V.; Staudenmayer, J.; McAvoy, C.R.; Boikova, M.; et al. A Catalog of Validity Indices for Step Counting Wearable Technologies during Treadmill Walking: The CADENCE-Adults Study. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2022, 19, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mühlen, J.M.; Stang, J.; Lykke Skovgaard, E.; Judice, P.B.; Molina-Garcia, P.; Johnston, W.; Sardinha, L.B.; Ortega, F.B.; Caulfield, B.; Bloch, W.; et al. Recommendations for Determining the Validity of Consumer Wearable Heart Rate Devices: Expert Statement and Checklist of the INTERLIVE Network. Br. J. Sports Med. 2021, 55, 767–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, E.; Lewis, K.; Directo, D.; Kim, M.J.; Dolezal, B.A. Validation of Biofeedback Wearables for Photoplethysmographic Heart Rate Tracking. J. Sports Sci. Med. 2016, 15, 540–547. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Navalta, J.W.; Davis, D.W.; Malek, E.M.; Carrier, B.; Bodell, N.G.; Manning, J.W.; Cowley, J.; Funk, M.; Lawrence, M.M.; DeBeliso, M. Heart Rate Processing Algorithms and Exercise Duration on Reliability and Validity Decisions in Biceps-Worn Polar Verity Sense and OH1 Wearables. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 11736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schweizer, T.; Gilgen-Ammann, R. Wrist-Worn and Arm-Worn Wearables for Monitoring Heart Rate During Sedentary and Light-to-Vigorous Physical Activities: Device Validation Study. JMIR Cardio 2025, 9, e67110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neudorfer, M.; Kumar, D.; Smeddinck, J.D.; Kulnik, S.T.; Niebauer, J.; Treff, G.; Sareban, M. Validity of Four Consumer-Grade Optical Heart Rate Sensors for Assessing Volume and Intensity Distribution of Physical Activity. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2024, 34, e14756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Y.; Ma, X.-K.; Zhu, Z.; Cao, Z.-B. Validity of Wrist-Wearable Activity Devices for Estimating Physical Activity in Adolescents: Comparative Study. JMIR MHealth UHealth 2021, 9, e18320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, C.C.; McCullough, A.K.; Aguiar, E.J.; Ducharme, S.W.; Tudor-Locke, C. Toward Harmonized Treadmill-Based Validation of Step-Counting Wearable Technologies: A Scoping Review. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falter, M.; Budts, W.; Goetschalckx, K.; Cornelissen, V.; Buys, R. Accuracy of Apple Watch Measurements for Heart Rate and Energy Expenditure in Patients With Cardiovascular Disease: Cross-Sectional Study. JMIR MHealth UHealth 2019, 7, e11889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Escudero, P.; Cabanas, A.M.; Dotor-Castilla, M.L.; Galindo-Canales, M.; Miguel-Tobal, F.; Fernández-Pérez, C.; Fuentes-Ferrer, M.; Giannetti, R.; Martín-Escudero, P.; Cabanas, A.M.; et al. Are Activity Wrist-Worn Devices Accurate for Determining Heart Rate during Intense Exercise? Bioengineering 2023, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merrigan, J.J.; Stovall, J.H.; Stone, J.D.; Stephenson, M.; Finomore, V.S.; Hagen, J.A. Validation of Garmin and Polar Devices for Continuous Heart Rate Monitoring During Common Training Movements in Tactical Populations. Meas. Phys. Educ. Exerc. Sci. 2023, 27, 234–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navalta, J.W.; Carrier, B.; Blank, M.; Zarei, S.; Davis, D.W.; Craig, M.; Perez, O.R.; Baca, J.; Sweder, T.S.; Carballo, T.; et al. Validity and Reliability of Wearable Technology Devices during Simulated Pickleball Game Play. Sports 2024, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chowdhury, E.A.; Western, M.J.; Nightingale, T.E.; Peacock, O.J.; Thompson, D. Assessment of Laboratory and Daily Energy Expenditure Estimates from Consumer Multi-Sensor Physical Activity Monitors. PLOS ONE 2017, 12, e0171720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajj-Boutros, G.; Landry-Duval, M.-A.; Comtois, A.S.; Gouspillou, G.; Karelis, A.D. Wrist-Worn Devices for the Measurement of Heart Rate and Energy Expenditure: A Validation Study for the Apple Watch 6, Polar Vantage V and Fitbit Sense. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2023, 23, 165–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, D.; Tyo, B.; Bassett, D.R. Comparison of Four ActiGraph Accelerometers during Walking and Running. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2010, 42, 368–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, M.D.; Kuo, C.C.; Pellegrini, C.A.; Hsu, M.J. Accuracy of Wristband Activity Monitors during Ambulation and Activities. Med. Sci. Sports Ererc 2016, 48, 1942–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cabanas, A.M.; Fuentes-Guajardo, M.; Latorre, K.; León, D.; Martín-Escudero, P. Skin Pigmentation Influence on Pulse Oximetry Accuracy: A Systematic Review and Bibliometric Analysis. Sensors 2022, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).