Submitted:

04 January 2026

Posted:

06 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Materials and Methods

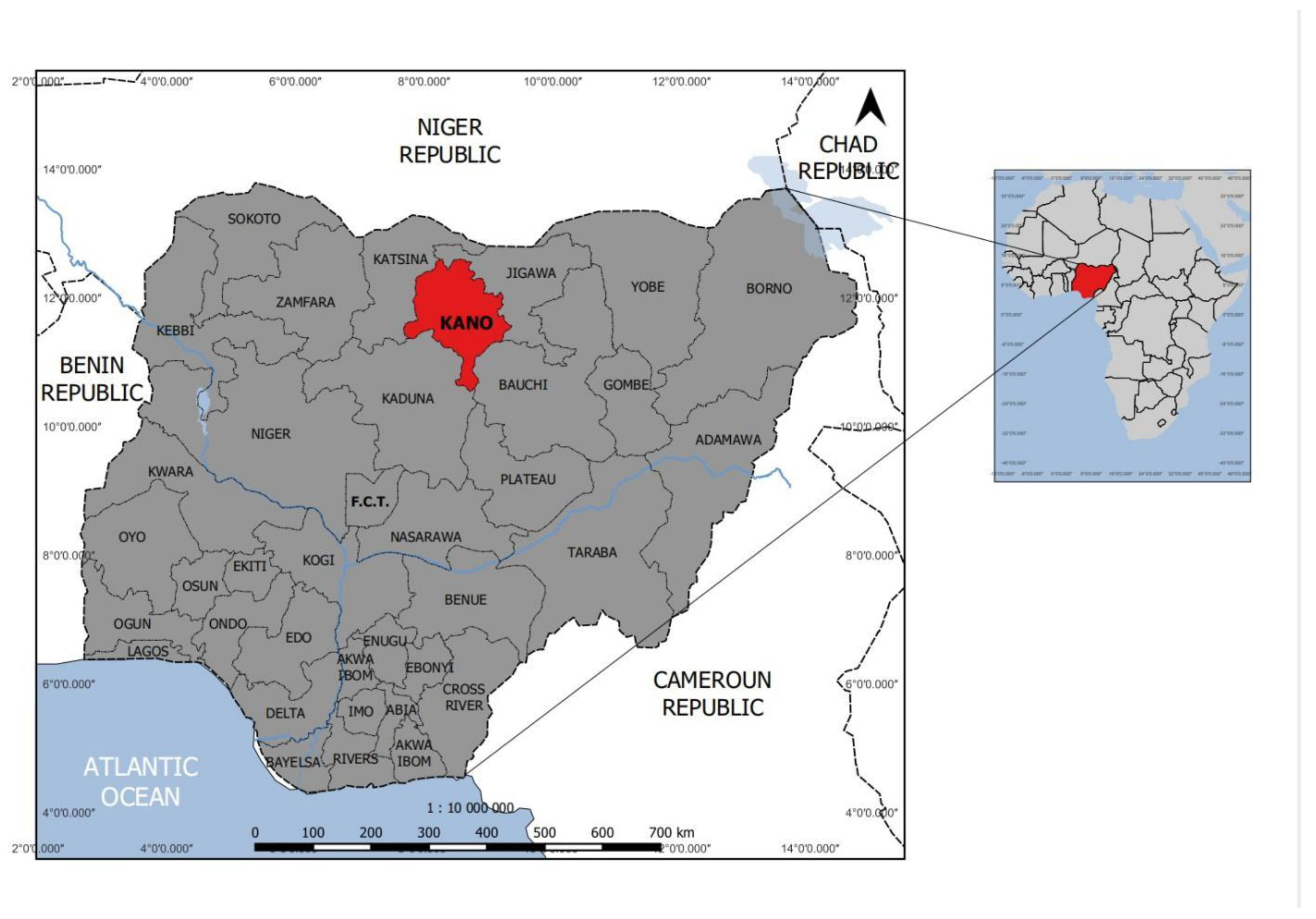

Study Area

Blood Sample Collection and Processing

Antibody Detection by Competitive Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (cELISA)

Statistical Analysis

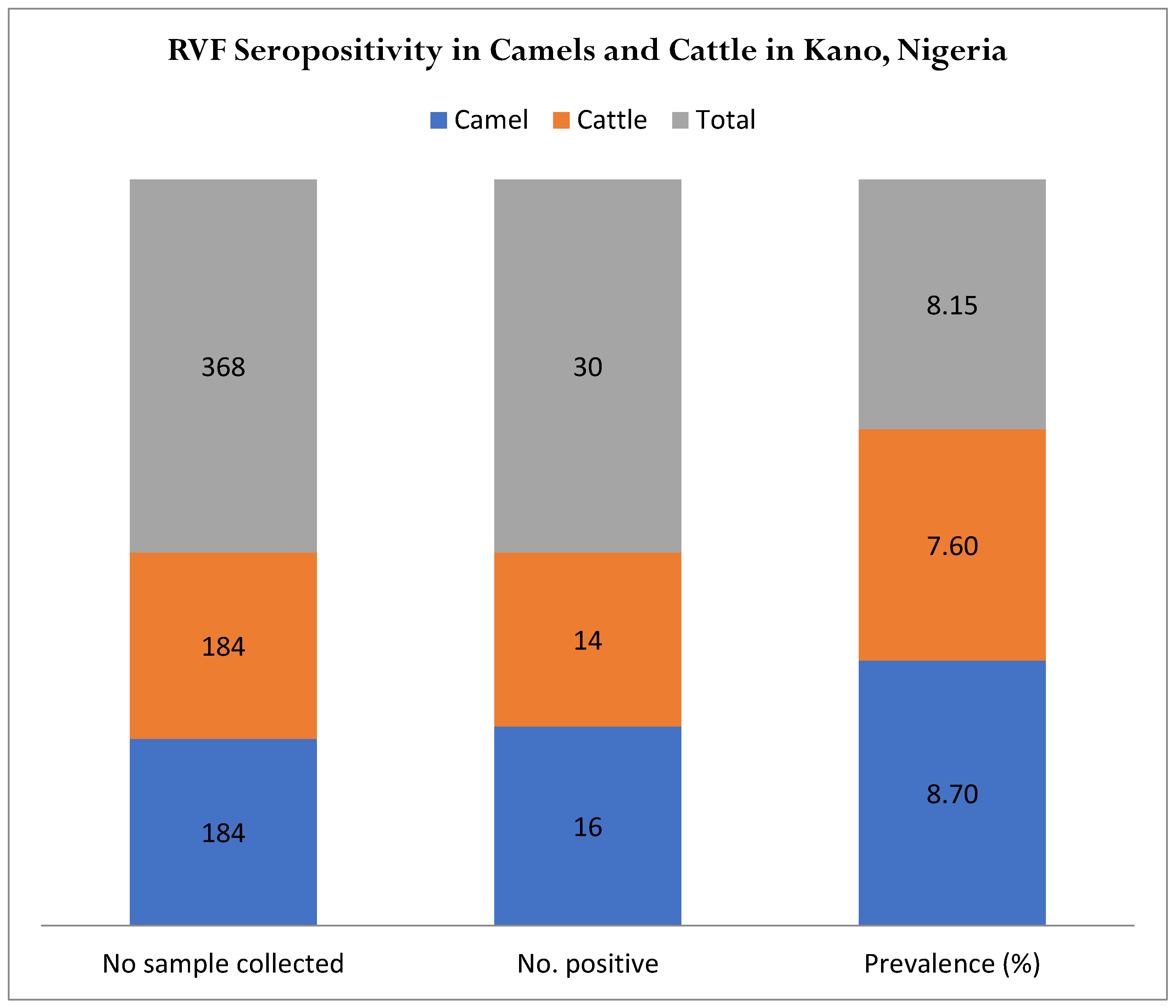

Results

Discussion

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abdallah, M.M.; Adam, I.A.; Abdalla, T.M.; Abdelaziz, S.A.; Ahmed, M.E.; Aradaib, I.E. A survey of rift valley fever and associated risk factors among the one-humped camel (Camelus dromedaries) in Sudan. Ir Vet J 2016, 69, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamu, A.M; Allam, L.; Sackey, A.K.B.; Nma, A.B.; Mshelbwala, P.P.; Machunga-Mambula, S.; Idoko, S.I; Adikwu, A.A.; Nafarnda, W.D.; Garba, B.S.; Owolodun, O.A.; Dzikwi, A.A.; Balogun, E.O; Simon, A.Y. Risk factors for Rift Valley fever virus seropositivity in one-humped camels (Camelus dromedarius) and pastoralist knowledge and practices in Northern Nigeria. One Health 2021, 13, 100340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam,s M.J.; E.J.; Lefkowitz, A.M.; King, B.; Harrach, R.L.; Harrison, N.J.; Knowles, A. M.; Kropinski, M.; Krupovic, J.H.; Kuhn, A.R.; Mushegian, M. Nibert et al., Changes to taxonomy and the International Code of Virus Classification and Nomenclature ratified by the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (2017), Arch. Virol. 2017. 162 (8) 2505–2538 [CrossRef]

- Al Zahrani, A; Alfakeeh, A; Alghareeb, W; Bakhribah, H; Basulaiman, B; Alsuhail, A; et al. Use of camel urine is of no benefit to cancer patients: observational study and literature review. East Mediterr Health J 2023, 29(8), 657–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akpa, GN; Abbaya, HY; Saley, ME. Comparative evaluation of the influence of species, age and sex on carcass characteristics of camels, cattle, sheep and goats in Sahel environment. Anim Res Int. 2017, 14, 2588. [Google Scholar]

- Alhaji, NB; Babalobi, OO; Wungak, Y; Ularamu, HG. Participatory survey of Rift Valley fever in nomadic pastoral communities of North-central Nigeria: The associated risk pathways and factors. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2018, 12(10), e0006858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anejo-Okopi, J.; Oragwa, A.O.; Okojokwu, O.J.; Joseph, S.; Chibueze, G.; Adetunji, J.; Okwori, J.A.; Amanyi, D.O.; Ujah, O.I.; Audu, O. Seroprevalence of Rift Valley fever virus infection among slaughtered ruminants in Jos, north-central, Nigeria. Hosts and viruses 2020, 7, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anyangu, AS; Gould, LH; Sharif, SK; Nguku, PM; Omolo, JO; Mutonga, D; Rao, CY; Lederman, ER; Schnabel, D; Paweska, JT; Katz, M; Hightower, A; Njenga, MK; Feikin, DR; Breiman, RF. Risk factors for severe Rift Valley fever infection in Kenya, 2007. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2010, 83(2 Suppl), 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolajoko, M.B.; Babalobi, O.O. Evaluation of the effectiveness of animal diseases reporting system in Oyo State, Nigeria (1995-2005). Journal of Commonwealth Veterinary Association 2011, 27, 264–267. [Google Scholar]

- Bronsvoort; Bagninbom, JM; Ndip, L; Kelly, RF; Handel, I; Tanya, VN; Morgan, KL; Ngu Ngwa, V; Mazeri, S; Nfon, C. Comparison of Two Rift Valley Fever Serological Tests in Cameroonian Cattle Populations Using a Bayesian Latent Class Approach. Front Vet Sci 2019, 6, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cêtre-Sossah, C.; Pédarrieu, A.; Guis, H.; Defernez, C.; Bouloy, M.; Favre, J.; Girard, S.; Cardinale, E.; Albina, E. Prevalence of Rift Valley fever among ruminants, Mayotte. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2012, 18(6), 972–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambaro, HM; Hirose, K; Sasaki, M; Libanda, B; Sinkala, Y; Fandamu, P; et al. An unusually long Rift valleyfever inter-epizootic period in Zambia: Evidence for enzootic virus circulation and risk for diseaseoutbreak. PLoS Negl Trop Dis [Internet] cited. 2022, 16(6). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Mamy, AB; Baba, MO; Barry, Y; Isselmou, K; Dia, ML; El Kory, MO; Diop, M; Lo, MM; Thiongane, Y; Bengoumi, M; Puech, L; Plee, L; Claes, F; de La Rocque, S; Doumbia, B. Unexpected Rift Valley fever outbreak, northern Mauritania. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011, 17(10), 1894–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ezeifeka, G.O.; Umoh, J.U.; Belino, E.D.; Ezeokoli, C.D. A serological survey for Rift Valley fever antibodies in food animals in Kaduna and Sokoto States of Nigeria. Int. J. Zoonoses. 1982, 9, 147–151. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Falzon, L.C.; Ogola, J.G.; Odinga, C.O.; Naboyshchikov, L.; Fevre, E.M.; Berezowski, J. Electronic data collection to enhance disease surveillance at the slaughterhouse in a smallholder production system. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 19447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faburay, B.; Labeaud, A.D.; Mcvey, D.S.; Wilson, W.C.; Richt, J.A. Current status of Rift Valley fever vaccine development. Vaccines 2017, 5(3), 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fawzy, M.; Helmy, Y.A. The one health approach is necessary for the control of Rift Valley fever infections in Egypt: a comprehensive review. Viruses 2019, 11(2), 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FAO. FOOSTAT; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, 2018; Available online: http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QA (accessed on 08 March 2025).

- Food, J. M. Immunity and charismatic camel. Lab Anim. 2013, 42, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerken, K.N.; Ndenga, B.A.; Owuor, K.O.; Winter, C.A.; Seetah, K.; LaBeaud, A.D. Leveraging livestock movements to urban slaughterhouses for wide-spread Rift Valley fever virus surveillance in Western Kenya. One Health 2022, 15, 100457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gür, S; Kale, M; Erol, N; Yapici, O; Mamak, N; Yavru, S. The first serological evidence for Rift Valley fever infection in the camel, goitered gazelle and Anatolian water buffaloes in Turkey. Trop Anim Health Prod 2017, 49(7), 1531–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hama, M. A.; Ibrahim, A. I.; Alassane, A.; Gagara, H.; Alambedji, R. B. Séroprévalence de la fièvre de la vallée du Rift chez les ruminants domestiques dans la région de Tahoua/Niger. International Journal of Biological and Chemical Sciences 2019, 13(7), Article 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrak, MEB. Faye, M. Bengoum, Main pathologies of camels, breeding of camels, constraints, benefits and perspectives, in: Conf. OIE, 2011, pp. 1–6.

- Hassine, T.B.; Amdouni, J.; Monaco, F.; Savini, G.; Sghaier, S.; Selimen, I.B.; Chandoul, W.; Hamida, K.B; Hammami, S. Emerging vector-borne diseases in dromedaries in Tunisia: West Nile, bluetongue, epizootic haemorrhagic disease and Rift Valley fever. Onderstepoort. J Vet Res. 2017, 84(1), e1–e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hestianah, EP; Khairullah, AR; Effendi, MH; Budiastuti, B; Tyasningsih, W; Budiarto, B; Permatasari, DA; Moses, IB; Ahmad, RZ; Wardhani, BWK; Kusala, MKJ; Kurniasih, DAA; Fauziah, I; Wibowo, S; Ugbo, EN; Fauzia, KA. Rift Valley fever: A zoonotic disease with global potential. Open Vet J 2025, 15(6), 2312–2328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICTV (International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses). ICTV 2023 Master Species List (MSL#39). 2024. Available online: https://ictv.global/.

- Ishema, L; Colombe, S; Ndayisenga, F; Uwibambe, E; Van Damme, E; Meudec, M; Rwagasore, E; Mugwaneza, D; Van Bortel, W; Shyaka, A. One Health investigation and response to a nationwide outbreak of Rift Valley fever in Rwanda - March to December 2022. One Health 2024, 19, 100854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen van Vuren, P; Kgaladi, J.; Patharoo, V.; Ohaebosim, P.; Msimang, V.; Nyokong, B.; Paweska, J.T. Human cases of Rift Valley fever in South Africa, 2018. Vector Borne Zoonot. Dis. 2018, 18(12), 713–715x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kadim, IT; Mahgoub, O; Purchas, RW. A review of the growth, and of the carcass and meat quality characteristics of the one-humped camel (Camelus dromedaries). Meat Sci. 2018, 80, 555–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kadja Mireille Catherine , Karimou Hamidou Ibrahim, Edmond Onidje, Souahibou Sourokou Sabi, Amadou Yahaya Mahamane, Haladou Gagara , Benjamin Obukowho Emikpe, Rianatou Bada Alambedji (2025). Seroprevalence of Rift Valley Fever Viruses Antibodies in Domestic Livestock in the Tahoua Region of Niger Veterinaria Italiana, Vol. 61 No. 3. [CrossRef]

- Kalthoum Sana, Elena Arsevska, Kaouther Guesmi, Aymen Mamlouk, Jamel Cherni, Monia lachtar, Raja Gharbi, Bassem Bel Haj Mohamed, Wiem Khalfaoui, Anissa Dhaouadi, Mohamed Naceur Baccar, Haikel Hajlaoui, Samia Mzoughi, Chedia Seghaier, Lilia Messadi d , Malek Zrelli e , Soufien Sghaierf , Catherine C^etre-Sossah c,g , Pascal Hendrikx, Cecile Squarzoni-Diaw (2012) Risk-based serological survey of Rift Valley fever in Tunisia (2017–2018). [CrossRef]

- Kandeel, M.; Al-Mubarak, A.I.A. Camel viral diseases: Current diagnostic, therapeutic, and preventive strategies. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 915475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalafalla, AI. Zoonotic diseases transmitted from the camels. Front Vet Sci. 2023, 10, 1244833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.J.; Park, J.Y.; Jeoung, H.Y.; Yeh, J.Y.; Cho, Y.S.; Choi, J.S.; Lee, J.Y.; Cho, I.S.; Yoo, H.S. Serological surveillance studies confirm the Rift Valley fever virus free status in South Korea. Trop Anim Health Prod. 2015, 7, 1427–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kortekaas, J. One Health approach to Rift Valley fever vaccine development. Antiviral Res 2014, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lapa, D; Pauciullo, S; Ricci, I; Garbuglia, AR; Maggi, F; Scicluna, MT; Tofani, S. Rift Valley Fever Virus: An Overview of the Current Status of Diagnostics. Biomedicines 2024, 12(3), 540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansfield, K.L.; Banyard, A.C.; McElhinney, L.; Johnson, N.; Horton, D.L.; Hernández-Triana, L.M.; Fooks, A.R. Rift Valley fever virus: a review of diagnosis and vaccination, and implications for emergence in Europe. Vaccine 2015, 33(42), 5520–5531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariner, JC; Morrill, J; Ksiazek, TG. Antibodies to hemorrhagic fever viruses indomestic livestock in Niger: Rift Valley fever and Crimean-Congo hemorrhagicfever. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1995, 53, 217–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mroz, C.; Gwida, M.; El-Ashker, M.; et al. Seroprevalence of Rift Valley fever virus in livestock during inter-epidemic period in Egypt, 2014/15. BMC Vet Res 2017, 13, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olaleye, O. D.; Tomori, O.; Schmitz, H. Rift Valley fever in Nigeria: infections in domestic animals. Revue scientifique ettechnique (International Office of Epizootics) 1996a, 15(3), 937–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olaleye, O. D.; Tomori, O.; Ladipo, M. A.; Schmitz, H. Rift Valley fever in Nigeria: infections in humans. Revue scientifique et technique (International Office of Epizootics) 1996b, 15(3), 923–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opayele, AV; Ndiana, LA; Odaibo, GN; Olaleye, DO. Serological evidence of Rift Valley fever virus infection in slaughtered ruminants in Nigeria. J Immunoassay Immunochem. 2019, 40(4), 367–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedarrieu, A; El Mellouli, F; Khallouki, H; Zro, K; Sebbar, G; Sghaier, S; Madani, H; Bouayed, N; Lo, MM; Diop, M; Ould El Mamy, AB; Barry, Y; Dakouo, M; Traore, A; Gagara, H; Souley, MM; Acha, S; Mapaco, L; Chang'a, J; Nyakilinga, D; Lubisi, BA; Tshabalala, T; Filippone, C; Heraud, JM; Chamassy, SB; Achiraffi, A; Keck, N; Grard, G; Mohammed, KAA; Alrizqi, AM; Cetre-Sossah, C. External quality assessment of Rift Valley fever diagnosis in countries at risk of the disease: African, Indian Ocean and Middle-East regions. PLoS One 2021, 16(5), e0251263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrova, V.; Kristiansen, P.; Norheim, G.; Yimer, A.S. Rift Valley fever: Diagnostic challenges and investment needs for vaccine development. BMJ Glob. Health 2020, 5, e002694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Ramírez, E; Cano-Gómez, C.; Llorente; Adzic, F; Al Ameer, B; Djadjovski, M; El Hage, I; El Mellouli, J; Goletic, F; Hovsepyan, T; Karayel-Hacioglu, H; Maksimovic Zoric, I; Mejri, J; Sadaoui, S; Salem, H; Sherifi, SH; Toklikishvili, K; Vodica, N; Monaco, A; Brun, F; Jiménez-Clavero, A; Fernández-Pinero, MÁ.J. External quality assessment of Rift Valley fever diagnosis in 17 veterinary laboratories of the Mediterranean and Black Sea regions. PLoS One 2020, 15(9), e0239478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rissmann, M; Eiden, M; El Mamy, BO; Isselmou, K; Doumbia, B; Ziegler, U; Homeier-Bachmann, T; Yahya, B; Groschup, MH. Serological and genomic evidence of Rift Valley fever virus during inter-epidemic periods in Mauritania. Epidemiol Infect 2017, 145(5), 1058–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selmi, R; Mamlouk, A; Ben; Said, M.; Ben, Yahia, H; Abdelaali, H; Ben Chehida, F. Daaloul-Jedidi M, Gritli A, Messadi L. First serological evidence of the Rift Valley fever Phlebovirus in Tunisian camels. Acta Trop. 2020 Jul;207:105462. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2020.105462. Socha, W.; Kwasnik, M.; Larska, M.; Rola, J.; Rozek, W.; 2022. Vector-borne viral diseases as a current threat for human and animal health-one health perspective. J. Clin. Med. 11(11), 3026 [CrossRef]

- Sumaye, R. D.; Geubbels, E.; Mbeyela, E.; Berkvens, D. Inter-epidemic Transmission of Rift Valley Fever in Livestock in the Kilombero River Valley, Tanzania: A Cross-Sectional Survey. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases 2013, 7(8), 2356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tigoi, C.; Sang, R.; Chepkorir, E.; Orindi, B.; Arum, S.O.; Mulwa, F.; et al. High risk for human exposure to Rift Valley fever virus in communities living along livestock movementroutes: A cross-sectional survey in Kenya. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2020, 14(2), e0007979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinto, B.; Quellec, J.; Cêtre-Sossah, C.; Dicko, A.; Salinas, S.; Simonin, Y. 2023. Rift Valley fever in West Africa: a zoonotic disease with multiple socio-economic consequences. One Health 17(1), 100583.Tomori, O. and Oluwayelu, D.O. 2023. Domestic animals as potential reservoirs of zoonotic viral diseases. Annu. Rev. Anim. Biosci. 11(1), 33–55. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organisation. Pathogens prioritization: a scientific framework for epidemic and pandemic research preparedness. Available online: https://www.who.int/teams/blueprint/who-r-and-d-blueprint-for-epidemics (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- World Animal Health Organization, Chapter 3.1.18 Rift Valley Fever, (n.d.). https ://www.woah.org/fileadmin/Home/eng/Health_standards/tahm/3.01.18_RVF.pdf (Accessed November 24, 2025).

| Sex | No. Sample Tested | No. Positive | % | Confidence Interval |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 114 | 9 | 7.89 | 3.19-13.99 |

| Female | 254 | 21 | 8.27 | 5.33-12.15 |

| Total | 368 | 30 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).