Submitted:

03 August 2025

Posted:

04 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical Approval

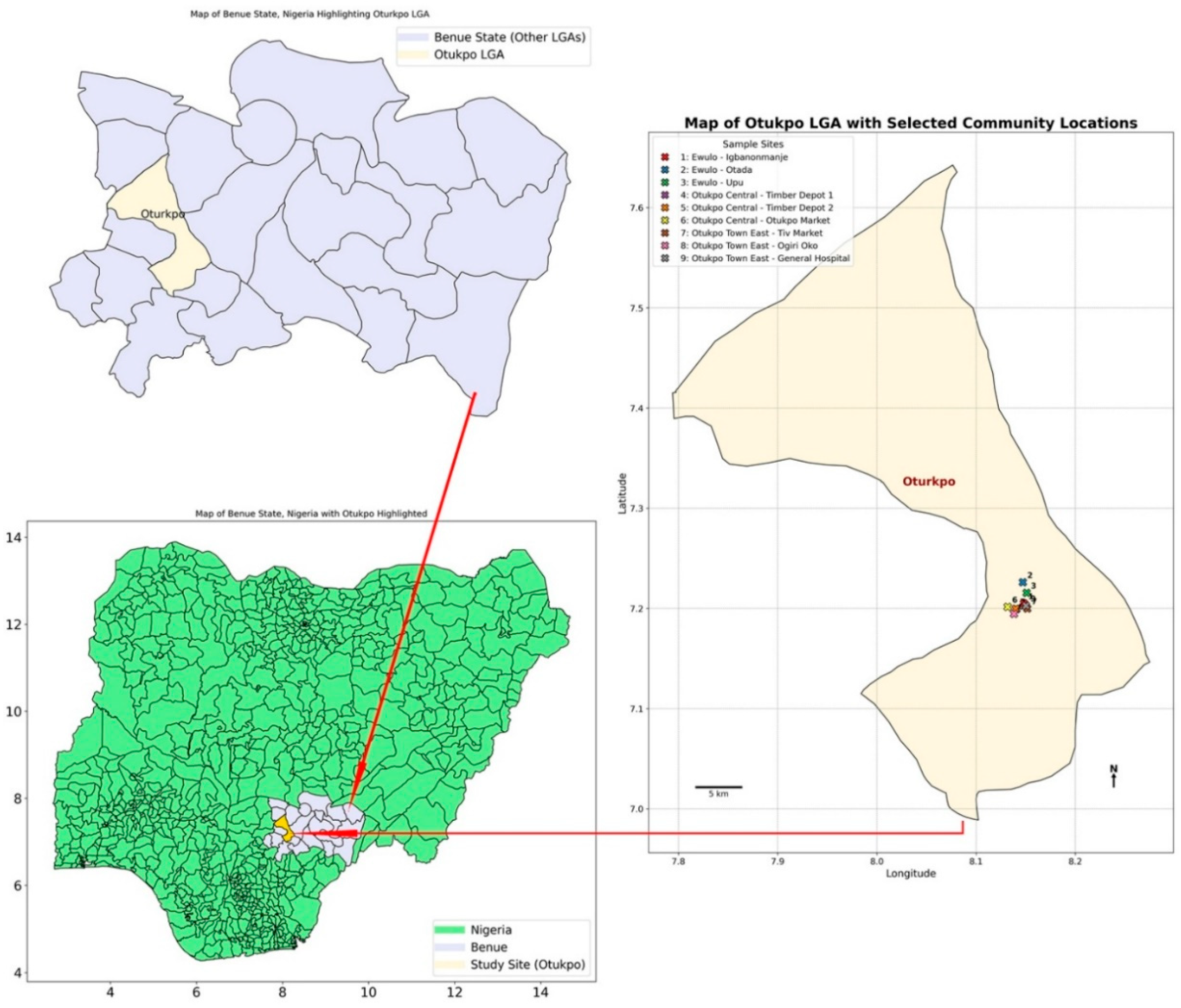

2.2. Study Sites

2.3. Traps Fabrication

2.4. Trapping of Small Mammals

2.5. Identification, Dissection, and Sample Collection of Small Mammals

2.6. Serological Testing of the Blood Samples for Lassa Fever Virus (LFV) Antibodies

2.7. Extraction of RNA and Reverse Transcription PCR (RT-PCR)

2.8. Data and Statistical Analyses

3. Results

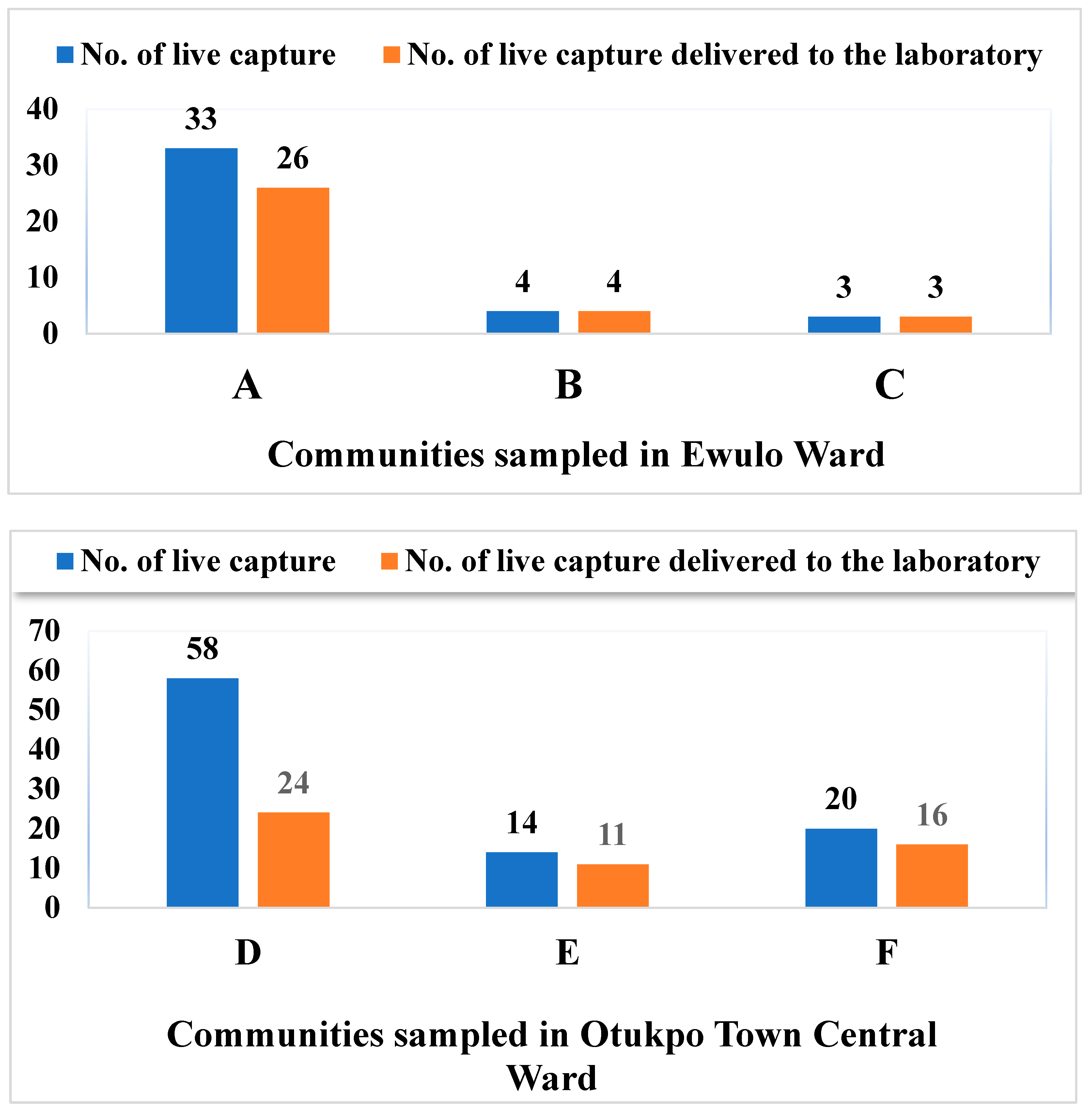

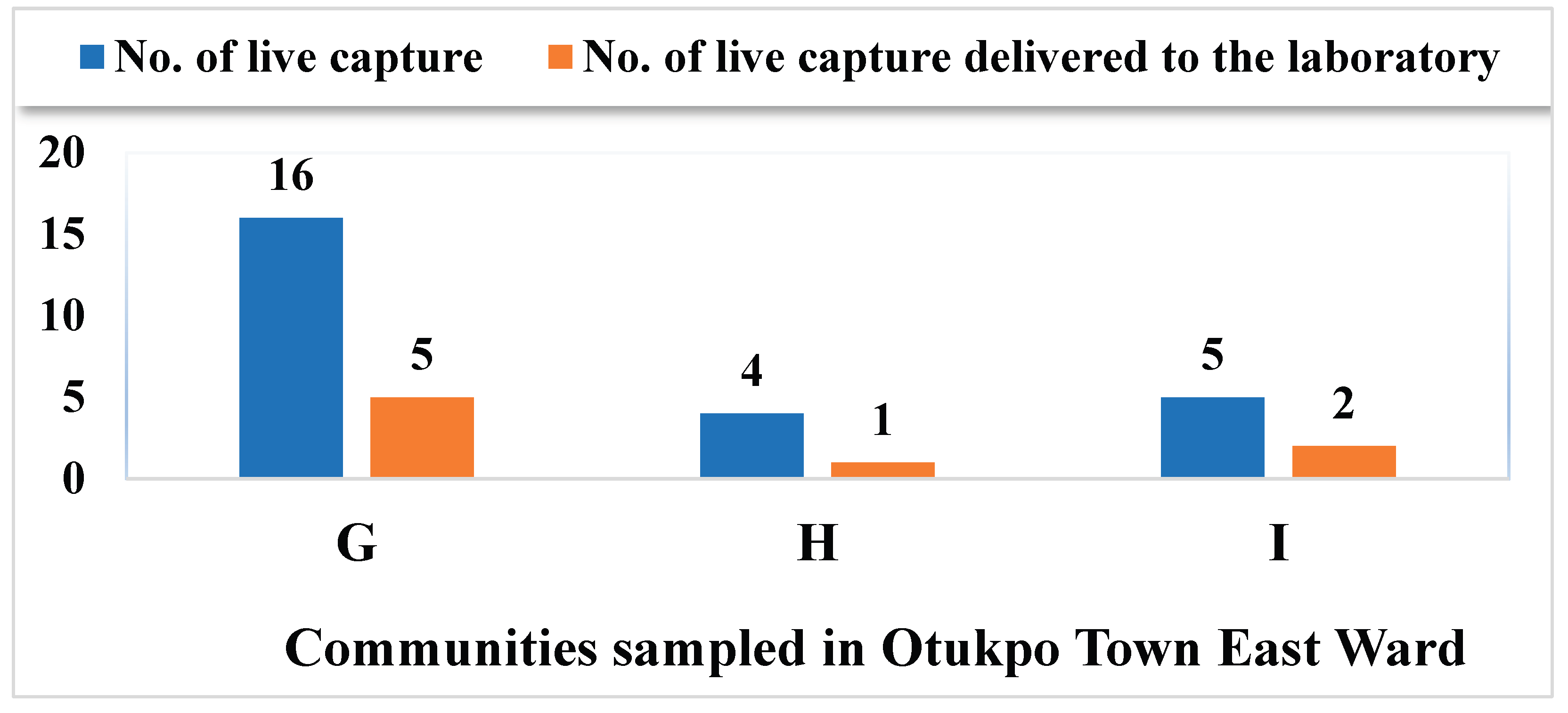

3.1. Live Capture Rate vs Survival Rate of Rodents and Rats in Otukpo LGA, North-Central Nigeria

3.2. Overview of the Capture Success of Rodents and Rats in the Nine Communities Sampled in Otukpo LGA, Benue State, North-Central Nigeria

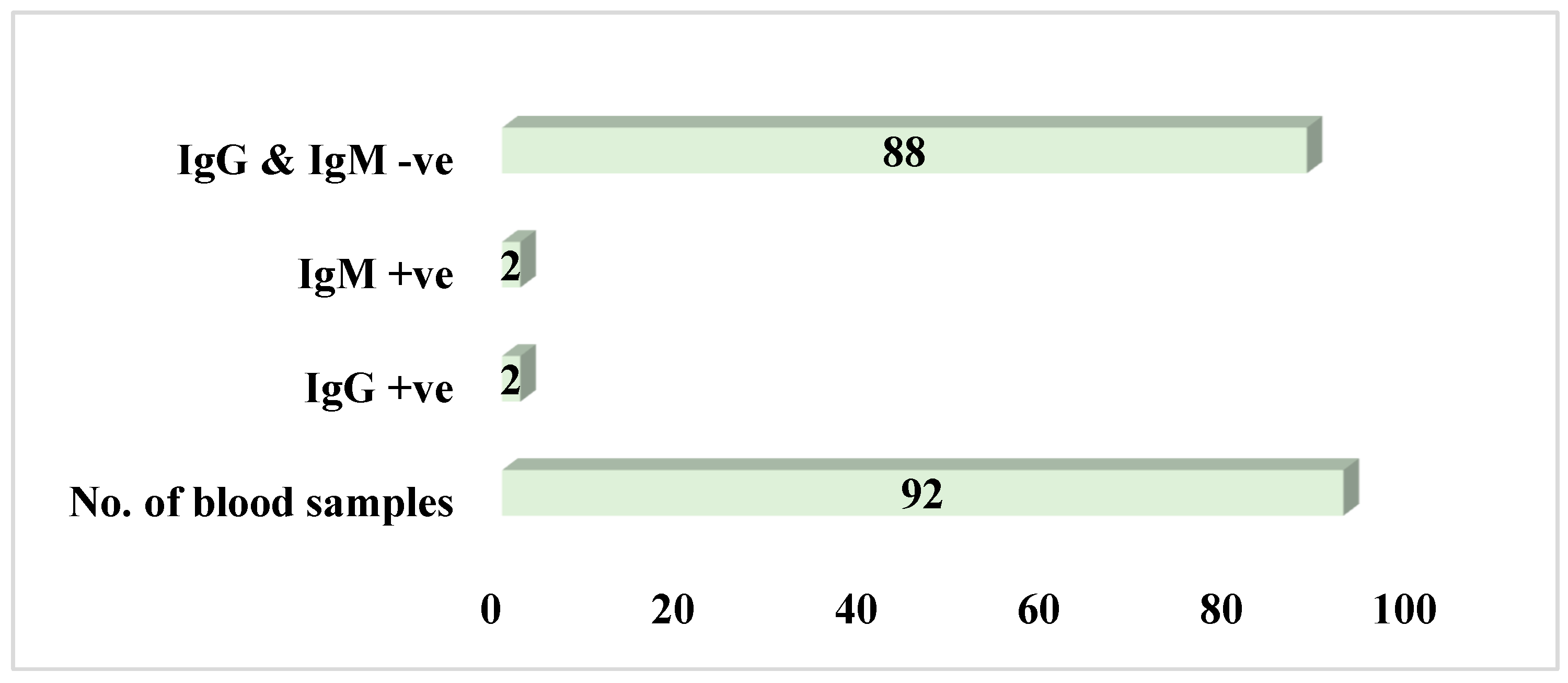

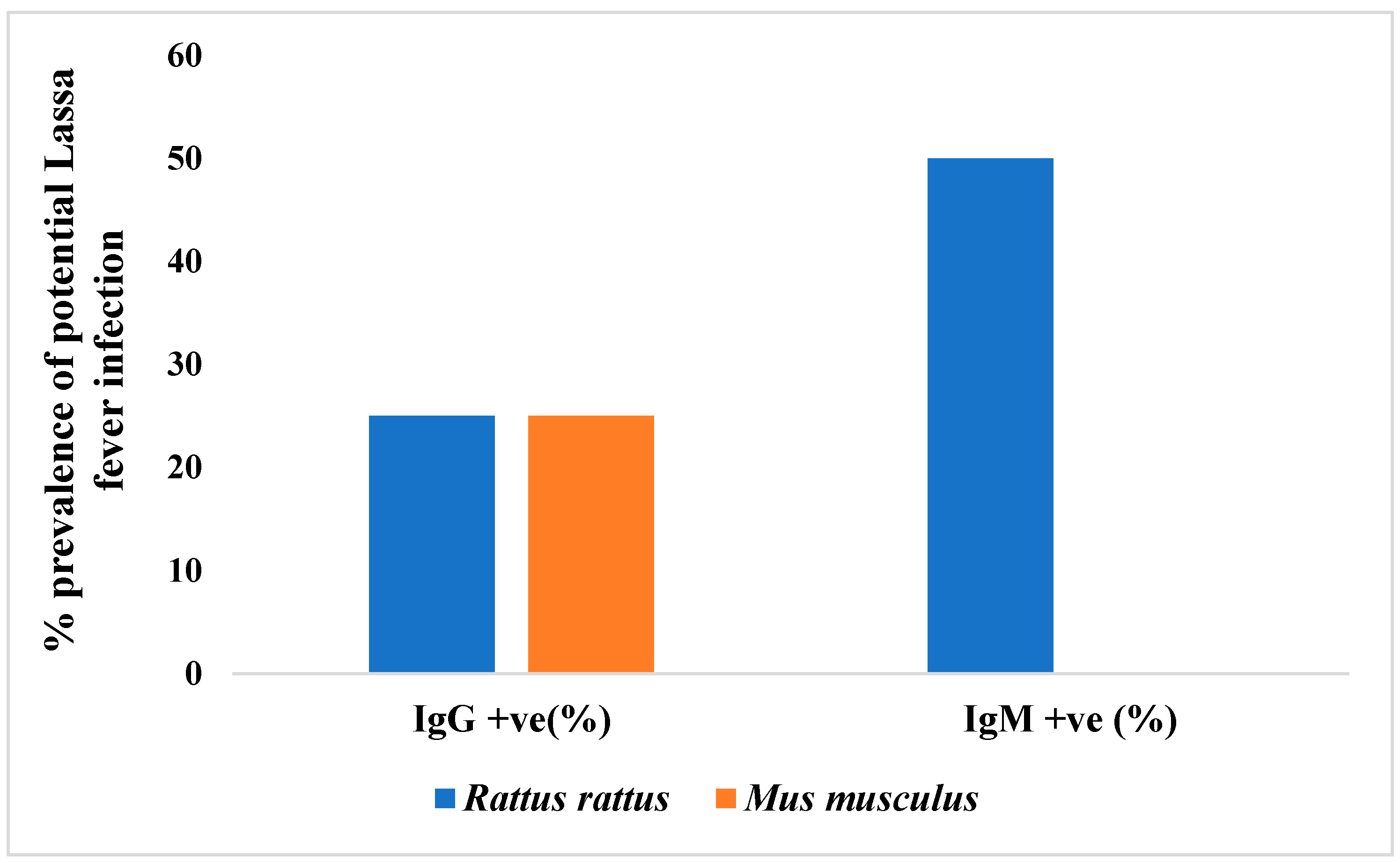

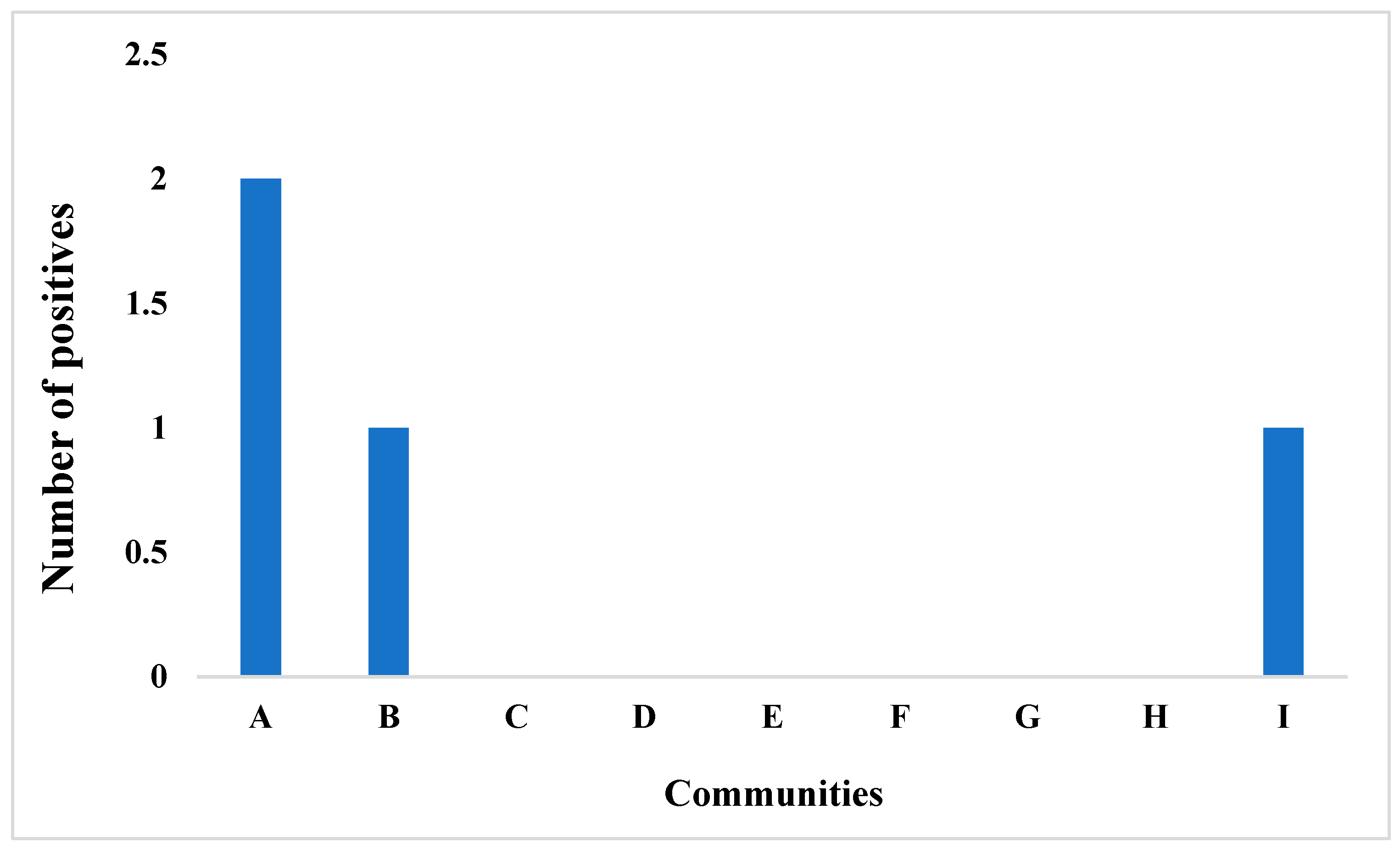

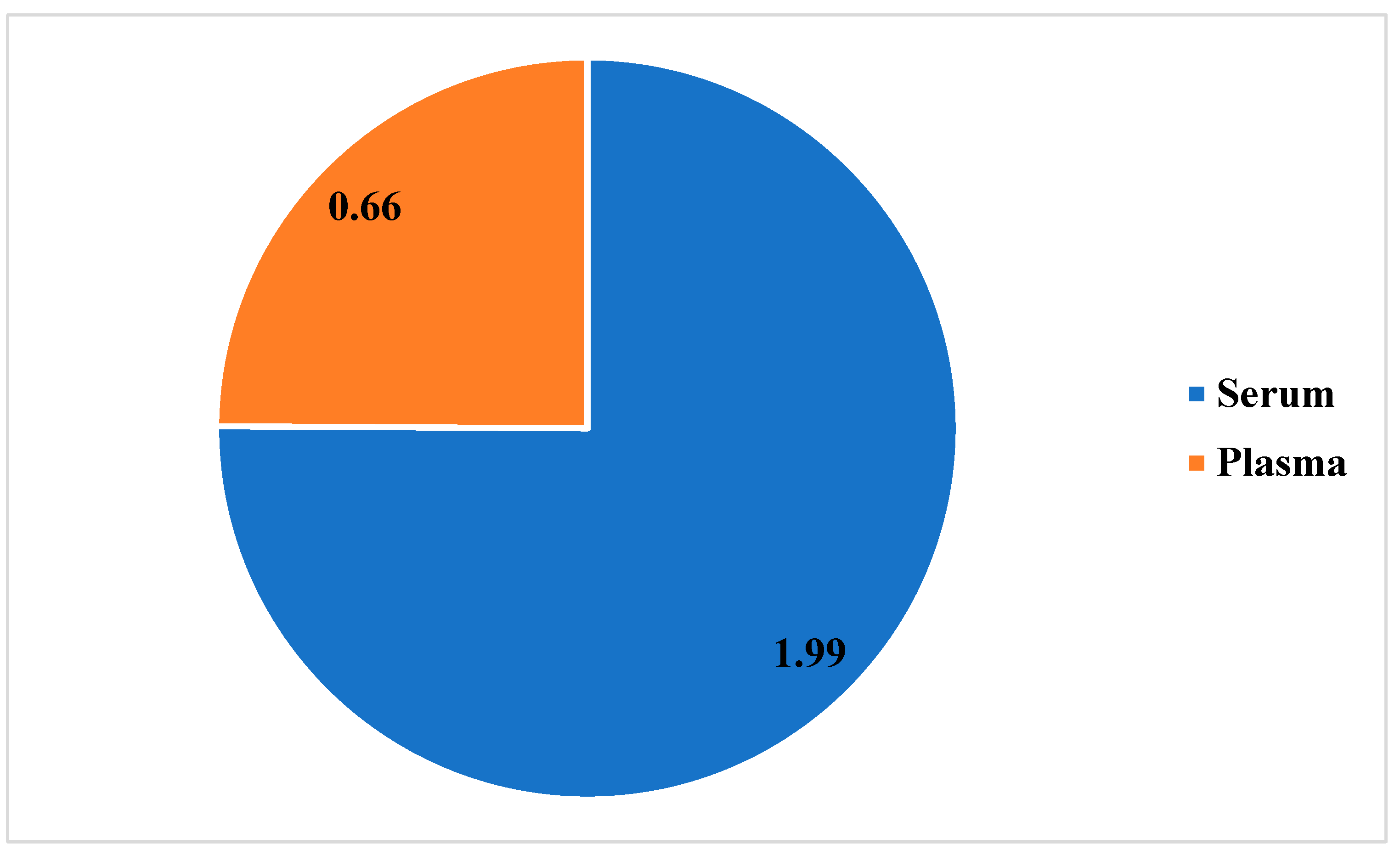

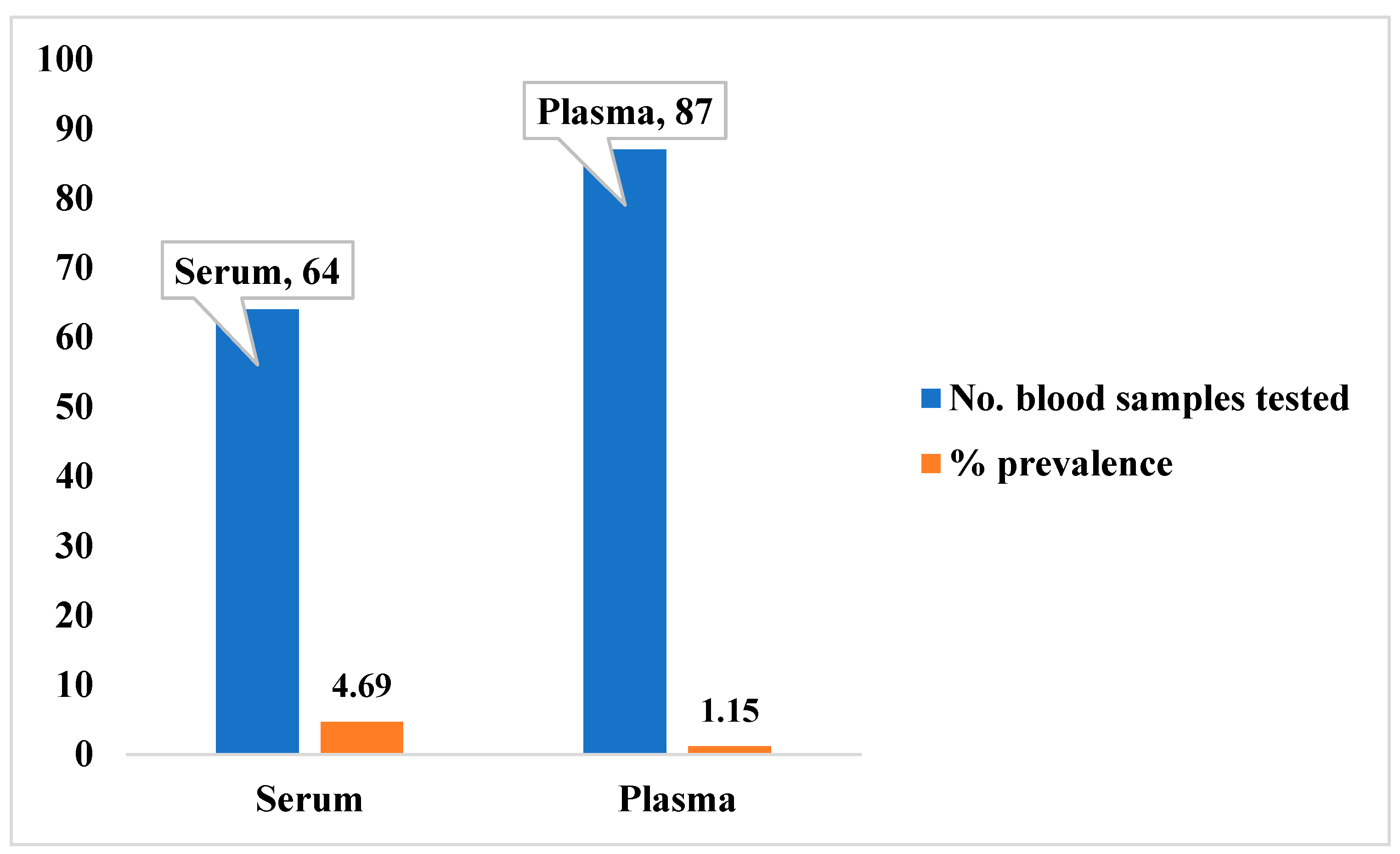

3.3. Potential Prevalence of Lassa Fever Infection Among Small Mammals in Otukpo LGA Based on Serological and Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) Screening

4. Discussion

4.1. Logistical Challenges and Sampling Limitations

4.2. Small Mammal Community Composition

4.3. Evidence of Seropositivity of LASV in the Small Mammals’ Blood Samples Types- IgG and IgM

4.4. Implications and Study Constraints

5. Conclusions and Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Richmond, J.K.; Baglole, D.J. Lassa fever: epidemiology, clinical features, and social consequences. BMJ. 2003, 327, 1271–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogbu, O.; Ajuluchukwu, E.; Uneke, C.J. Lassa fever in West African sub-region: an overview. J. Vector Borne Dis. 2007, 44, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Trovato, M.; Sartorius, R.; D’Apice, L.; Manco, R.; De Berardinis, P. Viral emerging diseases: challenges in developing vaccination strategies. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 2130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frame, J.D.; Baldwin, J.J.; Gocke, D.J.; Troup, J.M. Lassa fever, a new virus disease of man from West Africa. I. Clinical description and pathological findings. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1970, 19, 670–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCormick, J.B.; Fisher-Hoch, S.P. Lassa fever. Arenaviruses I: Epidemiol. Mol. Cell Biol. Arenaviruses 2002, 1, 75–109. [Google Scholar]

- Ogoina, D. Fever, fever patterns and diseases called ‘fever’–a review. J. Infect. Public Health 2011, 4, 108–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bausch, D.G.; Mills, J.N. Arenaviruses: Lassa fever, Lujo hemorrhagic fever, lymphocytic choriomeningitis, and the South American hemorrhagic fevers. Viral Infect. Hum. 2014, 5, 147–171. [Google Scholar]

- Grubaugh, N.D.; Ladner, J.T.; Lemey, P.; Pybus, O.G.; Rambaut, A.; Holmes, E.C.; Andersen, K.G. Tracking virus outbreaks in the twenty-first century. Nat. Microbiol. 2019, 4, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fichet-Calvet, E.; Rogers, D.J. Risk maps of Lassa fever in West Africa. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2009, 3, e388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olayemi, A.; Cadar, D.; Magassouba, N.; Obadare, A.; Kourouma, F.; Oyeyiola, A.; Fasogbon, S.; Igbokwe, J.; Rieger, T.; Bockholt, S.; Günther, S.; Fichet-Calvet, E. New hosts of the Lassa virus. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 25280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echchakery, M.; Boussaa, S.; Kahime, K.; Boumezzough, A. Epidemiological role of a rodent in Morocco: case of cutaneous leishmaniasis. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Dis. 2015, 5, 589–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, K.G.; Shylakhter, I.; Tabrizi, S.; Grossman, S.R.; Happi, C.T.; Sabeti, P.C. Genome-wide scans provide evidence for positive selection of genes implicated in Lassa fever. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2012, 367, 868–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitmer, S.L.; Strecker, T.; Cadar, D.; Dienes, H.P.; Faber, K.; Patel, K.; Günther, S. New lineage of Lassa virus, Togo, 2016. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2018, 24, 599–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Li, W.; Wang, Z.; Yang, W.; Li, E.; Xia, X.; Chiu, S. Emerging and reemerging infectious diseases: global trends and new strategies for their prevention and control. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salazar-Bravo, J.; Dragoo, J.W.; Bowen, M.D.; Peters, C.J.; Ksiazek, T.G.; Yates, T.L. Natural nidality in Bolivian hemorrhagic fever and the systematics of the reservoir species. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2002, 1, 191–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meerburg, B.G.; Singleton, G.R.; Kijlstra, A. Rodent-borne diseases and their risks for public health. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 2009, 35, 221–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCormick, J.B. Epidemiology and control of Lassa fever. In Arenaviruses: Biol. Immunother. 1987, 69–78.

- Lecompte, E.; Fichet-Calvet, E.; Daffis, S.; Koulémou, K.; Sylla, O.; Kourouma, F.; ter Meulen, J. Mastomys natalensis and Lassa fever, West Africa. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2006, 12, 1971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demby, A.H.; Inapogui, A.; Kargbo, K.; Koninga, J.; Kourouma, K.; Kanu, J.; Coulibaly, M.; Wagoner, K.D.; Ksiazek, T.G.; Peters, C.J.; Rollin, P.E.; Bausch, D.G. Lassa fever in Guinea: II. Distribution and prevalence of Lassa virus infection in small mammals. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2001, 1, 283–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, D.H.; McCormick, J.B.; Johnson, K.M.; Webb, P.A.; Komba-Kono, G.; Elliott, L.H.; Gardner, J.J. Pathologic and virologic study of fatal Lassa fever in man. Am. J. Pathol. 1982, 107, 349. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, K.M.; McCormick, J.B.; Webb, P.A.; Smith, E.S.; Elliott, L.H.; King, I.J. Clinical virology of Lassa fever in hospitalized patients. J. Infect. Dis. 1987, 155, 456–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demartini, J.C.; Green, D.E.; Monath, T.P. Lassa virus infection in Mastomys natalensis in Sierra Leone: Gross and microscopic findings in infected and uninfected animals. Bull. World Health Organ. 1975, 52, 651. [Google Scholar]

- Carey, D.E.; Kemp, G.E.; White, H.A.; Pinneo, L.; Addy, R.F.; Fom, A.L.M.D.; Henderson, B.E. Lassa fever: epidemiological aspects of the 1970 epidemic, Jos, Nigeria. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1972, 66, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Webb, P.A.; McCormick, J.B.; King, I.J.; Bosman, I.; Johnson, K.M.; Elliott, L.H.; O’Sullivan, R. Lassa fever in children in Sierra Leone, West Africa. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1986, 80, 577–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ter Meulen, J. Lassa fever: implications of T-cell immunity for vaccine development. J. Biotechnol. 1999, 73, 207–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sogoba, N.; Feldmann, H.; Safronetz, D. Lassa fever in West Africa: evidence for an expanded region of endemicity. Zoonoses Public Health 2012, 59, 43–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbaave, T.P.; Ogbu, O.; Echekwube, P.O.; Swende, T.Z.; Igbah, I.T. Lassa Fever: Patients Profile and Treatment Outcomes at Benue State University Teaching Hospital Makurdi, North-Central Nigeria. Adv. Infect. Dis. 2023, 13, 722–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monath, T.P. Lassa fever: review of epidemiology and epizootiology. Bull. World Health Organ. 1975, 52, 577. [Google Scholar]

- Capul, A.A.; de la Torre, J.C.; Buchmeier, M.J. Conserved residues in Lassa fever virus Z protein modulate viral infectivity at the level of the ribonucleoprotein. J. Virol. 2011, 85, 3172–3178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, N.E.; Walker, D.H. Pathogenesis of Lassa fever. Viruses 2012, 4, 2031–2048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grard, G.; Fair, J.N.; Lee, D.; Slikas, E.; Steffen, I.; Muyembe, J.J.; Leroy, E.M. A novel rhabdovirus associated with acute hemorrhagic fever in central Africa. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2012, 6, e100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delahoy, M.J.; Wodnik, B.; McAliley, L.; Penakalapati, G.; Swarthout, J.; Freeman, M.C.; Levy, K. Pathogens transmitted in animal feces in low-and middle-income countries. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2018, 221, 661–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frame, J.D.; Casals, J.; Dennis, E.A. Lassa virus antibodies in hospital personnel in western Liberia. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1979, 73, 219–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ter Meulen, J.; Lukashevich, I.; Sidibe, K.; Inapogui, A.; Marx, M.; Dorlemann, A.; et al. Hunting of peridomestic rodents and consumption of their meat as possible risk factors for rodent-to-human transmission of Lassa virus in the Republic of Guinea. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1996, 55, 661–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Günther, S.; Emmerich, P.; Laue, T.; Kühle, O.; Asper, M.; Jung, A.; Schmitz, H. Imported Lassa fever in Germany: molecular characterization of a new Lassa virus strain. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2000, 6, 466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georges, A.J.; Gonzalez, J.P.; Abdul Wahid, S.; Saluzzo, J.F.; Meunier, D.M.; McCormick, J.B. Antibodies to Lassa and Lassa-like viruses in man and mammals in the Central African Republic. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1985, 79, 78–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukashevich, I.S.; Maryankova, R.; Vladyko, A.S.; Nashkevich, N.; Koleda, S.; Djavani, M.; et al. Lassa and Mopeia virus replication in human monocytes/macrophages and in endothelial cells: different effects on IL-8 and TNF-alpha gene expression. J. Med. Virol. 1999, 59, 552–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macher, A.M.; Wolfe, M.S. Historical Lassa fever reports and 30-year clinical update. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2006, 12, 835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safronetz, D.; Mire, C.; Rosenke, K.; Feldmann, F.; Haddock, E.; Geisbert, T.; Feldmann, H. A recombinant vesicular stomatitis virus-based Lassa fever vaccine protects guinea pigs and macaques against challenge with geographically and genetically distinct Lassa viruses. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2015, 9, e0003736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garry, R.F. Lassa fever—the road ahead. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2023, 21, 87–96. [Google Scholar]

- Ehichioya, D.U.; Asogun, D.A.; Ehimuan, J.; Okokhere, P.O.; Pahlmann, M.; Ölschläger, S.; Omilabu, S.A. Hospital-based surveillance for Lassa fever in Edo State, Nigeria, 2005–2008. Trop. Med. Int. Health 2012, 17, 1001–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Happi, A.N.; Olumade, T.J.; Ogunsanya, O.A.; Sijuwola, A.E.; Ogunleye, S.C.; Oguzie, J.U.; Nwofoke, C.; Ugwu, C.A.; Okoro, S.J.; Otuh, P.I.; Ngele, L.N.; et al. Increased Prevalence of Lassa Fever Virus-Positive Rodents and Diversity of Infected Species Found during Human Lassa Fever Epidemics in Nigeria. Microbiol. Spectr. 2022, 10, e00366-22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateer, E.J.; Huang, C.; Shehu, N.Y.; Paessler, S. Lassa fever–induced sensorineural hearing loss: A neglected public health and social burden. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2018, 12, e0006187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asogun, D.A.; Günther, S.; Akpede, G.O.; Ihekweazu, C.; Zumla, A. Lassa fever: Epidemiology, clinical features, diagnosis, management and prevention. Infect. Dis. Clin. 2019, 33, 933–951. [Google Scholar]

- Olayemi, A.; Obadare, A.; Oyeyiola, A.; Fasogbon, S.; Igbokwe, J.; Igbahenah, F.; Fichet-Calvet, E. Small mammal diversity and dynamics within Nigeria, with emphasis on reservoirs of the Lassa virus. Syst. Biodivers. 2018, 16, 118–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klitting, R.; Kafetzopoulou, L.E.; Thiery, W.; Dudas, G.; Gryseels, S.; Kotamarthi, A.; Dellicour, S. Predicting the evolution of the Lassa virus endemic area and population at risk over the next decades. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 5596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Redding, D.W.; Gibb, R.; Dan-Nwafor, C.C.; Ilori, E.A.; Yashe, R.U.; Oladele, S.H.; Ihekweazu, C. Geographical drivers and climate-linked dynamics of Lassa fever in Nigeria. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 5759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edegbene, A.O.; Yandev, D.; Omotehinwa, T.O.; Zakari, H.; Andy, B.O. Water quality assessment in Benue South, Nigeria: An investigation of physico-chemical and microbial characteristics. Water Sci. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fichet-Calvet, E.; Lecompte, E.; Koivogui, L.; Soropogui, B.; Doré, A.; Kourouma, F.; Günther, S. Fluctuation of abundance and Lassa virus prevalence in Mastomys natalensis in Guinea, West Africa. Vector-Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2007, 7, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moses, L.M.; et al. Serological evidence of arenavirus circulation among rodents in endemic regions. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2022, 28, 561–570. [Google Scholar]

- Bowen, M.D.; Rollin, P.E.; Ksiazek, T.G.; Hustad, H.L.; Bausch, D.G.; Demby, A.H.; Bajani, M.D.; Peters, C.J.; Nichol, S.T. Genetic diversity among Lassa virus strains. J. Virol. 2000, 74, 6992–7004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, J.N.; Childs, J.E. Rodent-borne hemorrhagic fever viruses. Infect. Dis. Wild Mamm. 2001, 254–270. [Google Scholar]

- Mariën, J.; Kourouma, F.; Magassouba, N.F.; Leirs, H.; Fichet-Calvet, E. Movement patterns of small rodents in Lassa fever-endemic villages in Guinea. EcoHealth 2018, 15, 348–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, N.A.; Kenyon, M.A.; Ghersi, B.M.; Sparks, J.L.D.; Gass, J.D. Assessing the environmental drivers of Lassa fever in West Africa: A systematic review. Viruses 2025, 17, 504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aplin, K.P.; Chesser, T.; Have, J.T. Evolutionary biology of the genus Rattus: Profile of an archetypal rodent pest. ACIAR Monogr. Ser. 2003, 96, 487–498. [Google Scholar]

- Gratz, N. The burden of rodent-borne diseases in Africa south of the Sahara. Belg. J. Zool. 1997, 127, 71–84. [Google Scholar]

- Kennis, J.; Sluydts, V.; Leirs, H.; van Hooft, W.P. Polyandry and polygyny in an African rodent pest species, Mastomys natalensis. Mammalia 2008, 72, 226–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madueme, P.G.U.; Chirove, F. A systematic review of mathematical models of Lassa fever. Math. Biosci. 2024, 374, 109227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, K.G.; Shapiro, B.J.; Matranga, C.B.; Sealfon, R.; Lin, A.E.; Moses, L.M.; Sabeti, P.C. Clinical sequencing uncovers origins and evolution of Lassa virus. Cell 2015, 162, 738–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bausch, D.G.; Demby, A.H.; Coulibaly, M.; Kanu, J.; Goba, A.; Bah, A.; Rollin, P.E. Lassa fever in Guinea: I. Epidemiology of human disease and clinical observations. Vector-Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2001, 1, 269–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilori, E.A.; Furuse, Y.; Ipadeola, O.B.; Dan-Nwafor, C.C.; Abubakar, A.; Womi-Eteng, O.E.; Team, N.L.F.N.R. Epidemiologic and clinical features of Lassa fever outbreak in Nigeria, January 1–May 6, 2018. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2019, 25, 1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Günther, S.; Lenz, O. Lassa virus. Crit. Rev. Clin. Lab. Sci. 2004, 41, 339–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monath, T.P. Lassa fever and Marburg virus disease. WHO Chron. 1974, 28, 212–219. [Google Scholar]

- Cross, R.W.; Heinrich, M.L.; Fenton, K.A.; Borisevich, V.; Agans, K.N.; Prasad, A.N.; Geisbert, T.W. A human monoclonal antibody combination rescues nonhuman primates from advanced disease caused by the major lineages of Lassa virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2023, 120, e2304876120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Musa, S.S.; Zhao, S.; Gao, D.; Lin, Q.; Chowell, G.; He, D. Mechanistic modelling of the large-scale Lassa fever epidemics in Nigeria from 2016 to 2019. J. Theor. Biol. 2020, 493, 110209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isaäcson, M. The ecology of Praomys (Mastomys) natalensis in southern Africa. Bull. World Health Organ. 1975, 52, 629. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Eskew, E.A.; Bird, B.H.; Ghersi, B.M.; Bangura, J.; Basinski, A.J.; Amara, E.; Nuismer, S.L. Reservoir displacement by an invasive rodent reduces Lassa virus zoonotic spillover risk. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 3589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allan, R.; Mardell, S.; Ladbury, R.; Pearce, E.; et al. The progression from endemic to epidemic Lassa fever in war-torn West Africa. In Emergence and Control of Rodent-Borne Viral Diseases; Saluzzo, J.F., Dodet, B., Eds.; Elsevier: Annecy, France, 1998; pp. 97–105. [Google Scholar]

- ter Meulen, J.; Lenz, O.; Koivogui, L.; Magassouba, N.; et al. Short communication: Lassa fever in Sierra Leone: UN peacekeepers are at risk. Trop. Med. Int. Health 2001, 6, 83–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Capture rate (%) for: | |||||||||

| Communities in Ewulo Ward | Communities in Otukpo Central Ward | Communities in Otukpo Town East Ward | |||||||

| Rodents and rats’ taxa | A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I |

| Mus musculus | (9) 47.37% | (3) 12.50% | (1) 5.0% | (9) 45.0% | (7) 14.0% | (0) 0.00% | (0) 0.00% | (0) 0.00% | (0) 0.00% |

| Rattus rattus | (12) 63.16% | (1) 4.17% | (2) 10.0% | (15) 27.0% | (4) 80% | (15) 37.5% | (5) 66.67% | (1)5.6% | (2) 18.5% |

| Rattus norvegicus | (0) 0.00% | (0) 0.00% | (0) 0.00% | (0) 0.00% | (0) 0.00% | (1) 18.8% | (0) 0.00% | (0) 0.00% | (0) 0.00% |

| Tatera spp. | (4) 10.50% | (0) 0.00% | (0) 0.00% | (0) 0.00% | (0) 0.00% | (0) 0.00% | (0) 0.00% | (0) 0.00% | (0) 0.00% |

| Pallasiomys spp. | (1) 5.26% | (0) 0.00% | (0) 0.00% | (0) 0.00% | (0) 0.00% | (0) 0.00% | (0) 0.00% | (0) 0.00% | (0) 0.00% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).