Introduction

Over the past decade, the human gut microbiome has become a central focus of probiotic, nutraceutical, and functional food research. Advances in high-throughput sequencing, metagenomics, and bioinformatics have enabled increasingly detailed characterization of microbial communities and their responses to dietary and microbial interventions. In parallel, commercial and clinical interest in probiotics and other microbiome-modulating products has expanded rapidly, driven by their proposed therapeutic and preventive potential across a wide range of conditions, including gastrointestinal disorders, metabolic disease, immune dysfunction, and systemic [

1,

2,

3].

This growth has been accompanied by a substantial increase in human clinical trials investigating probiotics, prebiotics, synbiotics, and related interventions. Many of these studies report statistically significant changes in gut microbiome composition, often interpreted as evidence of clinical benefit or improved gut health [

4,

5,

6]. However, despite this growing body of literature, relatively few microbiome-focused trials generate evidence that convincingly supports health claims, withstands regulatory scrutiny, or translates into reproducible clinical outcomes. Discrepancies between microbiome modulation and clinically meaningful benefit remain common, contributing to uncertainty among clinicians, regulators, and scientifically literate consumers regarding the true therapeutic value of many probiotic interventions [

7,

8,

9].

These limitations are frequently attributed to the inherent complexity and inter-individual variability of the gut microbiome. While biological heterogeneity is undeniably a challenge, it does not fully explain the recurring difficulty in validating probiotic and microbiome-targeted interventions. Increasingly, attention has turned to the design, execution, and interpretation of clinical trials themselves. Across diverse indications and intervention types, common methodological patterns emerge that limit interpretability and weaken the evidentiary basis for clinical claims, even when trials are well intentioned and technically competent [

10,

11,

12].

A particularly pervasive issue is the reliance on descriptive microbiome metrics—such as alpha diversity, relative taxonomic abundance, or shifts in selected genera—as primary or surrogate endpoints for health benefit. Although these measures provide valuable insight into microbial community structure, they do not inherently reflect microbial function, host–microbe interactions, or physiological relevance. As a result, statistically significant microbiome changes may occur without corresponding improvements in clinical outcomes, leading to ambiguity in interpretation and overextension of claims [

13,

14,

15]. Similar challenges arise when trial endpoints are poorly aligned with intended claims, when subjective symptom measures are not corroborated by objective biological markers, or when key confounding variables such as diet, antibiotic exposure, and baseline health status are insufficiently controlled.

At the same time, expectations for clinical validation are rising. Regulatory agencies, journal reviewers, and healthcare professionals increasingly demand biologically plausible mechanisms linking probiotic interventions to host benefit, along with transparent, reproducible evidence supporting claimed effects [

16,

17,

18]. In this context, trials that prioritize convenience, exploratory outcomes, or post hoc interpretation over prospectively defined, mechanism-driven hypotheses face growing skepticism, regardless of statistical significance.

In this Commentary, we argue that many of the shortcomings observed in probiotic and microbiome-focused clinical trials are not inevitable consequences of biological complexity but rather reflect modifiable choices in study design and interpretation. Drawing on patterns observed across the published literature and practical experience in clinical research, we examine several recurring design and analytical pitfalls that limit the translational relevance of microbiome studies. We further discuss how greater alignment between intended claims, biological mechanisms, endpoint selection, and statistical discipline can improve the quality and interpretability of clinical validation efforts.

By focusing on principles rather than specific products or indications, this Commentary aims to provide a practical framework for strengthening the design of probiotic and microbiome-targeted clinical trials. As the field continues to mature, greater methodological rigor will be essential to realizing the therapeutic and preventive potential of probiotics and to ensuring that clinical applications are supported by evidence that is both scientifically credible and clinically meaningful.

Descriptive Microbiome Metrics versus Functional Relevance

A defining feature of many microbiome-focused probiotic and nutraceutical trials is the reliance on descriptive microbial community metrics as primary or co-primary endpoints. Measures such as alpha diversity, relative taxonomic abundance, and shifts in selected genera or species are frequently reported and interpreted as indicators of improved gut health or therapeutic benefit. While these metrics offer valuable insight into microbial community structure, their relevance to clinical outcomes is often assumed rather than demonstrated.

Alpha diversity, in particular, has become a commonly cited outcome in probiotic trials, often framed as a surrogate marker of microbiome health or resilience. However, diversity metrics are inherently context-dependent and provide limited information regarding microbial function, metabolic output, or host–microbe interactions. Increases in diversity may occur without corresponding improvements in digestion, metabolic regulation, immune function, or clinical symptoms, and in some contexts, higher diversity is not necessarily associated with better health outcomes [

13,

14,

19]. As a result, statistically significant changes in alpha diversity may be biologically interesting yet clinically ambiguous.

Similar limitations apply to taxonomic abundance data. Changes in the relative abundance of specific taxa are frequently highlighted in trial reports, sometimes with post hoc functional interpretations based on known characteristics of related organisms. However, taxonomic resolution alone does not reliably predict functional activity, particularly in the presence of functional redundancy, strain-level variation, and context-dependent gene expression [

20,

21,

22]. Consequently, taxonomic shifts may not translate into measurable physiological effects, especially when not accompanied by direct functional or host-level readouts.

From a clinical validation perspective, the core limitation of descriptive microbiome metrics is that they do not establish a causal or mechanistic link between an intervention and a health outcome. Regulators, journal reviewers, and clinicians increasingly expect evidence that observed microbiome changes are biologically meaningful and plausibly connected to host benefit. Without such linkage, descriptive findings risk being interpreted as associative rather than explanatory, limiting their utility for substantiating therapeutic or preventive claims [

15,

23].

In contrast, functional microbiome measures provide a more direct bridge between microbial modulation and host physiology. These include analyses of microbial metabolic pathways, quantification of key microbial metabolites such as short-chain fatty acids, assessment of bile acid transformation, and evaluation of microbial contributions to inflammatory or immune-modulatory processes [

24,

25,

26]. When integrated with host biomarkers—such as markers of inflammation, metabolic function, barrier integrity, or immune activation—functional readouts can help establish biological plausibility and strengthen causal inference.

Importantly, the limitations of descriptive metrics do not imply that such measures lack value. On the contrary, taxonomic and diversity data can play a critical role in hypothesis generation, contextualization of functional findings, and identification of responder subgroups. However, when used as primary indicators of clinical benefit, these metrics are frequently overinterpreted. Trials that prioritize descriptive endpoints without complementary functional and host-level measures risk generating results that are statistically robust but translationally weak.

For probiotic and nutraceutical interventions intended to support clinical applications, the selection of microbiome endpoints must therefore be guided by the intended claim and underlying biological mechanism. Descriptive metrics are most informative when embedded within a broader analytical framework that includes functional microbial activity and host response. Such integration enhances interpretability, improves reproducibility, and increases the likelihood that observed effects will support meaningful clinical validation rather than remain confined to descriptive microbiome change.

Misalignment Between Trial Endpoints and Intended Claims

A recurrent limitation in probiotic and microbiome-focused clinical trials is misalignment between the endpoints selected for measurement and the health claims the intervention is ultimately intended to support. In many cases, claims are formulated or refined only after data collection is complete, based on which outcomes show statistically significant change. While this retrospective approach may be tempting, it substantially weakens the evidentiary basis for clinical validation.

This pattern is evident across multiple application areas. Trials designed primarily to assess changes in gut microbiome composition are frequently interpreted post hoc in support of metabolic, immune, or systemic health claims, despite the absence of endpoints directly measuring those outcomes. Similarly, studies that collect stool-based microbiome data may imply effects on immune resilience or inflammation without incorporating immune biomarkers or clinical endpoints capable of substantiating such claims. When claims are inferred rather than prospectively tested, even positive findings are difficult to interpret and defend.

From a clinical validation standpoint, claims must be supported by endpoints that are not only statistically significant but also directly relevant to the asserted benefit. Endpoints chosen for analytical convenience, exploratory interest, or platform familiarity may generate publishable observations, yet remain poorly suited to substantiate therapeutic or preventive effects. This disconnect is particularly problematic in probiotic research, where mechanisms of action are often multifactorial and context dependent, requiring careful alignment between hypothesis, measurement, and interpretation.

Prospective alignment of claims and endpoints is therefore essential. At the design stage, investigators must clearly define the intended claim and identify the biological mechanisms through which the intervention is hypothesized to act. Endpoints should then be selected to capture both the mechanistic process and the clinically meaningful outcome. This hierarchy—claim, mechanism, endpoint—provides a coherent framework for trial design and reduces reliance on post hoc narrative construction [

27,

28,

29].

Failure to establish this alignment also complicates statistical interpretation. When multiple endpoints are collected without a clear prioritization tied to the intended claim, studies risk becoming underpowered for their most important outcomes while simultaneously increasing the likelihood of false-positive findings. In such cases, statistically significant results may reflect exploratory associations rather than robust evidence of clinical benefit. Regulatory agencies and journal reviewers increasingly scrutinize these practices, particularly when claims extend beyond the scope of the original study design [

30,

31].

Importantly, the issue is not whether exploratory endpoints should be included, but how they are positioned and interpreted. Exploratory microbiome or biomarker data can be highly informative, particularly in early-stage research. However, when exploratory findings are elevated to primary evidence for clinical claims, the resulting conclusions often exceed what the data can reasonably support. Clear distinction between hypothesis-generating and claim-supporting endpoints is therefore critical for maintaining scientific and clinical credibility.

For probiotic interventions intended for therapeutic or preventive application, trial design must begin with a disciplined articulation of the claim and its biological basis. Endpoints should be selected prospectively to test that claim directly, with supporting mechanistic measures incorporated to strengthen plausibility and interpretability. Trials designed in this manner are better positioned to generate evidence that is clinically meaningful, reproducible, and suitable for validation across diverse medical contexts

Symptom-Based Outcomes, Placebo Effects, and Responsible Interpretation

Patient-reported outcomes (PROs) are a central component of many probiotic and microbiome-focused clinical trials, particularly in areas such as digestive health, functional gastrointestinal disorders, and subjective well-being. Symptoms often represent the primary reason individuals seek probiotic interventions, and changes in symptom burden are therefore clinically meaningful. However, reliance on symptom-based outcomes alone presents important challenges for clinical validation, particularly in the context of placebo responsiveness.

Symptom improvement in placebo groups is a common and well-documented phenomenon in nutraceutical and microbiome trials. Such improvements may arise from expectancy effects, regression to the mean, increased symptom awareness, behavioral changes associated with trial participation, or heightened engagement with diet and lifestyle during the study period [

32,

33,

34]. In probiotic studies, placebo responsiveness may be especially pronounced, as participants frequently enroll with strong beliefs regarding gut health and anticipated benefit [

5]. As a result, symptom improvement in both active and placebo arms should be viewed as an expected design reality rather than an anomaly.

Importantly, placebo-associated improvement does not invalidate a trial or negate the potential biological activity of an intervention. Rather, it underscores the limitations of using symptom change alone to establish clinical relevance. When symptom-based outcomes improve across study arms, differentiation between specific intervention effects and nonspecific responses becomes difficult in the absence of objective biological corroboration. This challenge is compounded by the inherent variability of symptom scales, differences in questionnaire sensitivity, and limited reproducibility across studies and populations [

35].

From a scientific and regulatory perspective, symptom-only outcomes are therefore considered weak unless supported by additional evidence. Without objective markers, it is difficult to determine whether observed symptom improvements reflect modulation of disease-relevant pathways, transient perceptual changes, or contextual effects unrelated to the intervention itself. This ambiguity often limits interpretability, even when symptom changes reach statistical significance [ [

36].

Responsible trial design addresses these challenges through integration rather than exclusion. PROs are most informative when combined with objective host biomarkers that reflect relevant physiological processes, such as markers of inflammation, gut barrier function, metabolic regulation, or immune activity. When symptom improvements align with biologically plausible changes in host markers—and, where appropriate, with mechanistically consistent microbiome functional shifts—confidence in causal inference is substantially strengthened [

37,

38].

This integrative approach also facilitates more nuanced interpretation of placebo effects. For example, improvements observed in placebo groups may illuminate the sensitivity of symptom measures or the influence of contextual factors, while divergence in biomarker or mechanistic endpoints can help distinguish specific intervention effects. Rather than viewing placebo responsiveness as a confounding nuisance, trials that incorporate biological anchoring can leverage it as an interpretive signal, clarifying which outcomes reflect true physiological modulation [

39].

In the context of probiotic interventions intended for therapeutic or preventive application, addressing placebo effects responsibly is therefore not a matter of eliminating subjective outcomes, but of contextualizing them appropriately. Trials that combine symptom-based measures with objective, mechanism-aligned biomarkers are better positioned to generate evidence that is interpretable, reproducible, and suitable for robust clinical validation.

Confounding Variables and Trial Discipline in Microbiome Research

A fundamental challenge in probiotic and microbiome-focused clinical trials is the sensitivity of the gut microbiome to a wide range of external and host-related variables. Diet, recent antibiotic exposure, concomitant medications, baseline health status, and lifestyle factors can all exert substantial influence on microbial composition and function. When these variables are insufficiently controlled or characterized, they introduce noise that can obscure true intervention effects and undermine interpretability.

Dietary intake represents one of the most significant confounders in microbiome research. Short-term changes in macronutrient composition, fiber intake, and food diversity can rapidly alter microbial community structure and metabolic output, sometimes to a greater extent than the intervention under study [

40,

41,

42]. Trials that do not monitor or standardize diet risk attributing microbiome changes to the probiotic intervention when they may instead reflect dietary variability. While full dietary control is often impractical, failure to assess or account for dietary patterns limits the strength of causal inference.

Recent and concurrent antibiotic exposure poses an additional challenge. Antibiotics can induce profound and sometimes prolonged disruptions of the gut microbiome, affecting both taxonomic composition and functional capacity [

43,

44]. Inclusion of participants with heterogeneous antibiotic histories without appropriate stratification or exclusion criteria can introduce substantial inter-individual variability, reducing statistical power and complicating interpretation. Similar concerns apply to commonly used medications such as proton pump inhibitors, metformin, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, all of which have been shown to influence the gut microbiome independently of probiotic supplementation [

45,

46,

47].

Baseline health status and microbiome composition further contribute to heterogeneity. Individuals may differ markedly in microbial diversity, functional potential, immune tone, and metabolic state at study entry, influencing both responsiveness to probiotic interventions and the direction of observed effects. Without careful baseline characterization and consideration of responder versus non-responder patterns, aggregate analyses may mask meaningful subgroup effects or generate misleading null results [

48,

49].

Beyond participant characteristics, trial discipline itself plays a critical role in data quality. Inadequate protocol adherence, inconsistent sample collection, variable timing of assessments, and incomplete follow-up can all erode signal and reduce confidence in study outcomes. Microbiome analyses are particularly sensitive to such inconsistencies, as sample handling, storage conditions, and sequencing workflows can introduce technical variability that compounds biological noise [

50,

51,

52].

Addressing these challenges requires treating potential confounders as design parameters rather than statistical afterthoughts. This includes the use of clear inclusion and exclusion criteria, pre-specified handling of recent antibiotic use, dietary assessment or standardization strategies, and rigorous protocol adherence monitoring. While no trial can eliminate all sources of variability, transparent documentation and proactive management of confounding factors substantially enhance interpretability and reproducibility.

For probiotic interventions intended to support clinical applications, failure to adequately control or account for confounding variables represents a major barrier to validation. Trials that incorporate disciplined design practices—combined with thoughtful baseline characterization and high-quality execution—are more likely to detect true biological effects and generate evidence that is credible, reproducible, and clinically meaningful

Statistical Power, Microbiome Variability, and Hypothesis Discipline

High inter-individual variability is a defining characteristic of the human gut microbiome and presents a substantial statistical challenge for probiotic and nutraceutical clinical trials. Microbial community composition, functional capacity, and host–microbe interactions vary widely across individuals, even within ostensibly homogeneous populations. When this variability is not adequately accounted for in study design and analysis, trials may be underpowered to detect biologically meaningful effects or may generate results that are difficult to reproduce.

Many microbiome-focused trials enroll sample sizes that are sufficient for detecting large effect sizes in conventional clinical biomarkers but inadequate for capturing more subtle or heterogeneous microbiome-mediated effects. This limitation is often compounded by the inclusion of numerous exploratory endpoints without clear prioritization. As the number of measured outcomes increases, statistical power for any single endpoint decreases, while the risk of false-positive findings rises. In such settings, statistically significant results may reflect chance associations rather than robust intervention effects [

30,

52,

53].

Endpoint overload also complicates interpretation. Trials that attempt to measure a broad array of microbiome, biomarker, and symptom outcomes without a clearly defined primary hypothesis can produce complex datasets that are difficult to analyze coherently. Without pre-specified endpoint hierarchies and statistical plans, investigators may be tempted to emphasize outcomes that reach nominal significance while downplaying null findings. This practice, while often unintentional, undermines confidence in reported effects and contributes to inconsistency across studies.

Hypothesis discipline is therefore critical. Well-designed trials begin with a limited number of clearly articulated primary hypotheses tied directly to the intended claim and underlying biological mechanism. Sample size calculations should be based on realistic effect size assumptions for these primary outcomes, informed by prior data where available. Secondary and exploratory endpoints can provide valuable context and support mechanistic interpretation, but they should be explicitly designated as such and interpreted cautiously [

54,

55].

Pilot-to-pivotal development pathways offer a pragmatic strategy for addressing uncertainty in effect size and variability. Early-stage pilot studies can be used to assess feasibility, refine endpoints, and generate preliminary estimates of variability, which in turn inform the design of larger, confirmatory trials. Attempting to combine exploratory discovery and definitive validation within a single, underpowered study often leads to ambiguous results that satisfy neither objective.

From a clinical validation perspective, statistical rigor is not merely a technical consideration but a determinant of credibility. Regulators, journal reviewers, and clinicians increasingly scrutinize whether studies are appropriately powered for their stated objectives and whether conclusions are supported by pre-specified analyses. Trials that demonstrate hypothesis discipline and transparent statistical planning are more likely to generate evidence that is reproducible, interpretable, and suitable for substantiating therapeutic or preventive claims.

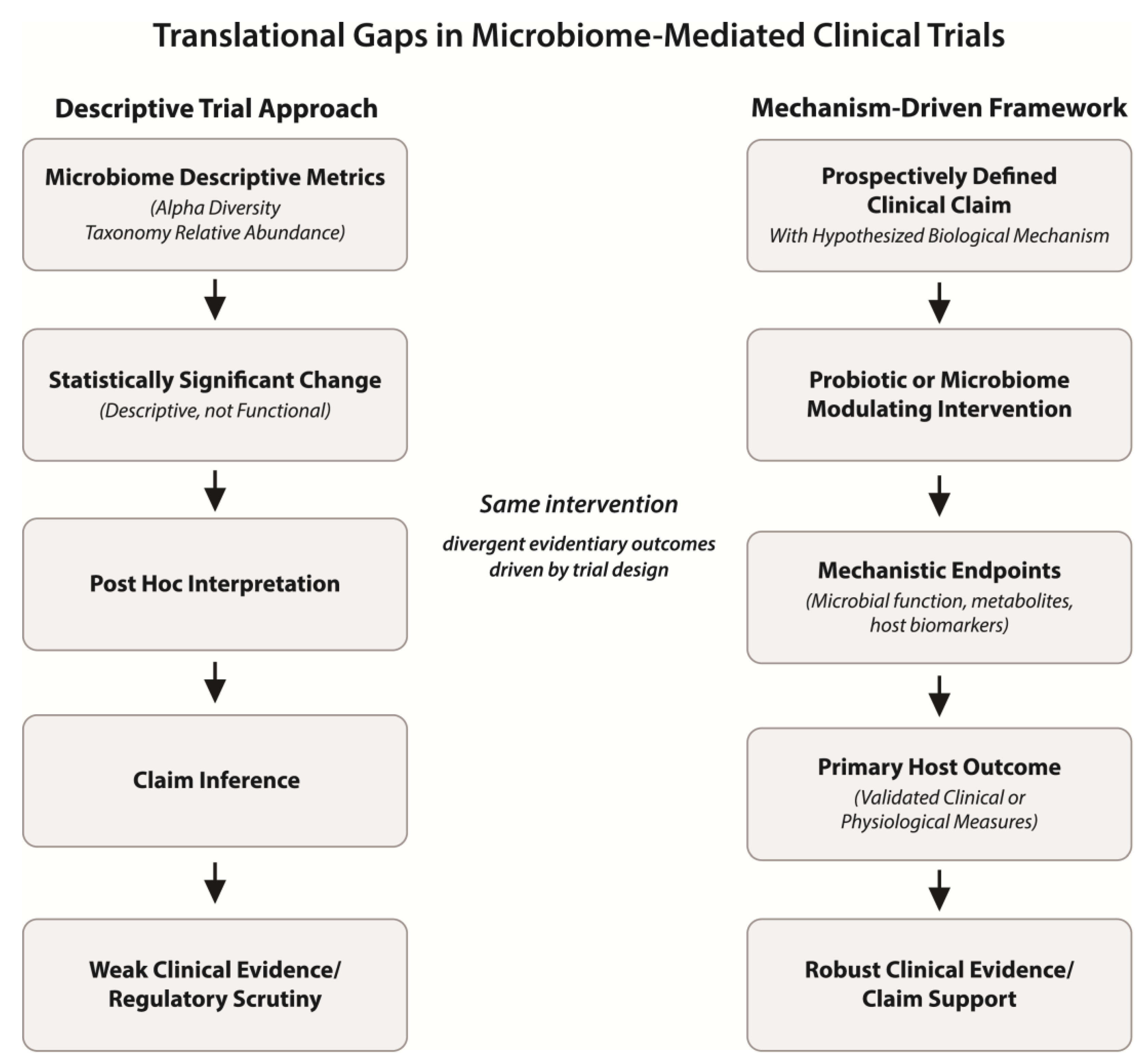

In the context of probiotic and microbiome-targeted interventions, acknowledging and accommodating microbiome variability through disciplined hypothesis selection, realistic power calculations, and staged development approaches can substantially improve the reliability of clinical validation efforts. Such practices help ensure that observed effects reflect true biological signals rather than statistical artifacts and that conclusions drawn from complex datasets are proportionate to the strength of the evidence. These contrasting design logics—and their implications for interpretability and clinical validation—are summarized schematically in

Figure 1.

Reframing the Microbiome as a Mechanistic Mediator

A recurring source of confusion in probiotic and microbiome-focused clinical research is the treatment of the microbiome itself as a primary outcome of interest. While changes in microbial composition or diversity are often highlighted as indicators of efficacy, health claims are ultimately made about host benefit rather than microbial state. This disconnect contributes to overinterpretation of microbiome data and weakens the translational relevance of many trials.

In most clinical contexts, the gut microbiome functions not as an endpoint, but as a mechanistic intermediary between an intervention and a host outcome. Probiotic or nutraceutical interventions may alter microbial composition or function, which in turn influences host physiology through effects on metabolism, immune signaling, barrier integrity, or inflammatory tone. The clinical relevance of microbiome modulation therefore depends on whether these downstream host effects are demonstrated, not merely whether microbial change occurs.

When microbiome measures are treated as endpoints rather than mechanisms, trials risk conflating

change with

benefit. For example, a statistically significant shift in microbial taxa may be biologically interesting, yet clinically inconsequential if it does not lead to measurable improvement in relevant host outcomes. Conversely, meaningful host benefits may occur with minimal or transient changes in microbial composition, particularly when functional activity rather than taxonomic structure is the primary driver of effect [

24,

56,

57].

Viewing the microbiome as a mechanistic mediator has important implications for trial design and interpretation. First, it clarifies the role of microbiome data within the evidentiary hierarchy. Microbiome analyses are most powerful when used to explain how an intervention exerts its effects, rather than to define whether it is effective. Second, this framing encourages integration of microbial data with host-level biomarkers and clinical endpoints, strengthening biological plausibility and causal inference.

This perspective also helps reconcile inconsistencies across studies. Variability in microbiome composition, sequencing methods, or analytical pipelines may lead to divergent descriptive findings, even when interventions produce similar host-level effects. By prioritizing host outcomes and mechanistic integration over descriptive microbiome change, researchers can better assess the clinical significance of probiotic interventions across diverse populations and study designs [

58,

59].

Importantly, reframing the microbiome as a mediator does not diminish its scientific importance. On the contrary, it elevates microbiome research by situating microbial data within a coherent biological narrative that links intervention, mechanism, and outcome. Trials designed with this perspective are more likely to generate interpretable, reproducible evidence and to support claims that are credible to clinicians, regulators, and patients.

As the field moves toward more clinically oriented applications of probiotics, adoption of this mechanistic framing will be increasingly important. Recognizing the microbiome as a mediator rather than an endpoint provides a conceptual foundation for more disciplined trial design and sets the stage for developing robust frameworks for clinical validation.

Toward More Robust Frameworks for Clinical Validation of Probiotics

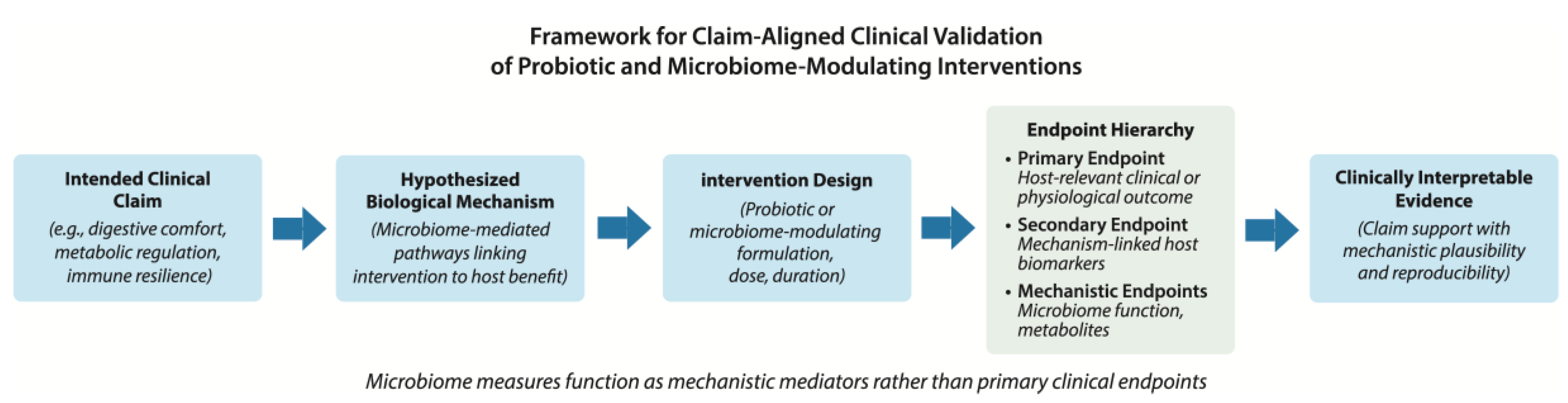

The recurring limitations discussed above point to a central conclusion: many probiotic and microbiome-focused clinical trials fail to support defensible claims not because interventions lack biological activity, but because study designs do not adequately align claims, mechanisms, endpoints, and interpretation. Addressing this gap requires a more disciplined and integrated approach to clinical validation—one that treats trial design as a translational exercise rather than a purely exploratory endeavor. A structured framework for claim-aligned clinical validation of probiotic and microbiome-modulating interventions is illustrated in

Figure 2.

A useful starting point is explicit articulation of the intended clinical claim. Whether an intervention is proposed to support digestive comfort, metabolic regulation, immune resilience, or disease risk reduction, the claim should be defined prospectively and framed in terms of a measurable host benefit. This definition provides the foundation for all subsequent design decisions and helps prevent post hoc reinterpretation of outcomes. Claims that are vague or overly broad are difficult to validate and often lead to diffuse endpoint selection and ambiguous conclusions.

Once the claim is defined, investigators should identify the biological mechanisms through which the probiotic intervention is hypothesized to exert its effect. In most cases, this involves specifying how modulation of the gut microbiome is expected to influence host physiology—for example, through changes in microbial metabolism, immune signaling, barrier function, or inflammatory pathways. Clarifying this mechanistic rationale enables selection of endpoints that are both biologically relevant and interpretable in a clinical context.

Endpoint selection should then follow a clear hierarchy. Primary endpoints should directly assess the host outcome associated with the intended claim, using validated clinical or biomarker measures where possible. Secondary endpoints may capture supporting biological processes, such as host biomarkers that reflect mechanistic engagement. Microbiome measures are most appropriately positioned as mechanistic or contextual endpoints, used to explain observed host effects rather than to define efficacy on their own. This hierarchy helps ensure that statistical power is concentrated on outcomes that matter most for validation.

Statistical planning and hypothesis discipline are integral to this framework. Sample size calculations should be based on realistic effect size assumptions for primary endpoints, informed by prior evidence and pilot data where available. Secondary and exploratory analyses should be pre-specified and interpreted with appropriate caution. Adoption of staged development strategies—beginning with pilot studies to refine endpoints and assess variability, followed by adequately powered confirmatory trials—can further strengthen the evidentiary foundation for clinical claims.

Equally important is proactive management of confounding variables and trial execution quality. Dietary intake, medication use, baseline health status, and other sources of variability should be treated as design considerations rather than analytical nuisances. Rigorous protocol adherence, standardized sample handling, and transparent reporting of methodological details enhance reproducibility and facilitate meaningful comparison across studies.

Finally, interpretation of results should remain proportionate to the strength and scope of the evidence generated. Demonstration of microbiome modulation alone should not be conflated with proof of clinical benefit. Conversely, when host-level outcomes improve in parallel with mechanistically consistent microbiome changes, confidence in causal inference is strengthened. Clear distinction between exploratory findings and claim-supportive evidence preserves scientific credibility and supports responsible translation into clinical and commercial contexts.

Together, these principles define a framework for more robust clinical validation of probiotic and microbiome-targeted interventions. By aligning claims with mechanisms, prioritizing clinically meaningful endpoints, integrating microbiome data mechanistically, and maintaining statistical and methodological discipline, future trials can better fulfill the promise of probiotics as therapeutic and preventive tools across diverse medical conditions.

Conclusions and Future Directions

The growing clinical and commercial interest in probiotics and other microbiome-modulating interventions reflects genuine promise for therapeutic and preventive applications across diverse conditions. However, the persistent gap between reported microbiome changes and defensible health claims indicates that the central barrier to validation is often methodological rather than biological. As argued in this Commentary, many trials are undermined by modifiable design and interpretive choices that reduce clinical relevance, weaken causal inference, and limit reproducibility.

Across the current literature, recurring pitfalls include overreliance on descriptive microbiome metrics as surrogate indicators of benefit, misalignment between prespecified endpoints and the claims ultimately advanced, and excessive dependence on symptom-only outcomes in settings characterized by substantial placebo responsiveness. These challenges are compounded by inadequate control of confounding variables—particularly diet, antibiotic exposure, and concomitant medications—as well as by endpoint overload, underpowered designs, and insufficient statistical discipline. Collectively, these issues can produce datasets that are statistically interesting yet clinically ambiguous, limiting their value for rigorous validation.

A unifying corrective principle is to treat the microbiome primarily as a mechanistic mediator rather than the endpoint of interest. Clinical claims should be anchored in host-relevant outcomes and supported by prospectively defined endpoints that are aligned with explicit biological mechanisms. Microbiome measures are most informative when integrated to explain how an intervention engages its proposed mechanism and when interpreted alongside objective host biomarkers that anchor symptom changes in physiology.

Future progress will depend on adopting more disciplined validation pathways. Early-stage studies should be used to refine mechanistic hypotheses, identify appropriate biomarkers, and estimate variability, thereby informing adequately powered confirmatory trials. Trial designs should incorporate transparent strategies for managing confounders, emphasizing baseline characterization, protocol adherence, and standardized sampling workflows. Equally important, interpretation should remain proportional to evidentiary strength, clearly distinguishing exploratory observations from claim-supportive outcomes.

As the field matures, greater rigor should not be viewed as a constraint on innovation, but as a prerequisite for meaningful translation. By aligning claims, mechanisms, and endpoint hierarchies—and by integrating microbiome measures with host biomarkers and clinically meaningful outcomes—microbiome-mediated trials can move beyond descriptive change toward reproducible clinical validation. This shift is essential for realizing the therapeutic and preventive potential of probiotics and related interventions, and for ensuring that clinical applications are supported by evidence that is credible to clinicians, regulators, and scientific peers.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.D.J.C.; writing—original draft preparation, R.D.J.C.; writing—review and editing, R.D.J.C. and G.G.M.; supervision, R.D.J.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not Applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not Applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not Applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge colleagues and collaborators for insightful discussions and critical feedback that helped shape the ideas presented in this Commentary.

References

- Huttenhower, C.; Gevers, D.; Knight, R.; et al. Structure, function and diversity of the healthy human microbiome. nature 2012, 486, 207–214. [Google Scholar]

- Marchesi, J.R.; Adams, D.H.; Fava, F.; Hermes, G.D.; Hirschfield, G.M.; Hold, G.; Quraishi, M.N.; Kinross, J.; Smidt, H.; Tuohy, K.M. The gut microbiota and host health: a new clinical frontier. Gut 2016, 65, 330–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salminen, S.; Collado, M.C.; Endo, A.; Hill, C.; Lebeer, S.; Quigley, E.M.M.; Sanders, M.E.; Shamir, R.; Swann, J.R.; Szajewska, H.; et al. The International Scientific Association of Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP) consensus statement on the definition and scope of postbiotics. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2021, 18, 649–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derrien, M.; van Hylckama Vlieg, J.E. Fate, activity, and impact of ingested bacteria within the human gut microbiota. Trends in microbiology 2015, 23, 354–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFarland, L.V. Use of probiotics to correct dysbiosis of normal microbiota following disease or disruptive events: a systematic review. BMJ open 2014, 4, e005047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, M.E.; Merenstein, D.J.; Reid, G.; Gibson, G.R.; Rastall, R.A. Probiotics and prebiotics in intestinal health and disease: from biology to the clinic. Nature reviews Gastroenterology & hepatology 2019, 16, 605–616. [Google Scholar]

- Reid, G. Probiotics: definition, scope and mechanisms of action. Best practice & research Clinical gastroenterology 2016, 30, 17–25. [Google Scholar]

- Cani, P.D. Human gut microbiome: hopes, threats and promises. Gut 2018, 67, 1716–1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncanson, K.; Williams, G.; Hoedt, E.C.; Collins, C.E.; Keely, S.; Talley, N.J. Diet-microbiota associations in gastrointestinal research: a systematic review. Gut Microbes 2024, 16, 2350785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansour, S.; Alkhaaldi, S.M.; Sammanasunathan, A.F.; Ibrahim, S.; Farhat, J.; Al-Omari, B. Precision nutrition unveiled: gene–nutrient interactions, microbiota dynamics, and lifestyle factors in obesity management. Nutrients 2024, 16, 581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kok, C.R.; Rose, D.; Hutkins, R. Predicting personalized responses to dietary fiber interventions: opportunities for modulation of the gut microbiome to improve health. Annual Review of Food Science and Technology 2023, 14, 157–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, A.J.; Vangay, P.; Al-Ghalith, G.A.; Hillmann, B.M.; Ward, T.L.; Shields-Cutler, R.R.; Kim, A.D.; Shmagel, A.K.; Syed, A.N.; Walter, J. Daily sampling reveals personalized diet-microbiome associations in humans. Cell host & microbe 2019, 25, 789–802. e785. [Google Scholar]

- Shade, A. Diversity is the question, not the answer. The ISME journal 2017, 11, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willis, A.D. Rarefaction, alpha diversity, and statistics. Frontiers in microbiology 2019, 10, 2407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, S.V.; Pedersen, O. The human intestinal microbiome in health and disease. New England journal of medicine 2016, 375, 2369–2379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EFSA Panel on Dietetic Products, N.; Allergies. Guidance on the scientific requirements for health claims related to the immune system, the gastrointestinal tract and defence against pathogenic microorganisms. EFSA Journal 2016, 14, 4369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, R.L. Current regulatory guidelines and resources to support research of dietary supplements in the United States. Critical reviews in food science and nutrition 2020, 60, 298–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioannidis, J.P. Why most published research findings are false. Chance 2019, 32, 4–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falony, G.; Joossens, M.; Vieira-Silva, S.; Wang, J.; Darzi, Y.; Faust, K.; Kurilshikov, A.; Bonder, M.J.; Valles-Colomer, M.; Vandeputte, D. Population-level analysis of gut microbiome variation. Science 2016, 352, 560–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Che, L.; Yang, S.; Zhang, X.; Lin, Y.; Shi, Y.; Zou, N.; Wang, S.; Zhang, Y. GutMetaNet: an integrated database for exploring horizontal gene transfer and functional redundancy in the human gut microbiome. Nucleic acids research 2025, 53, D772–D782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peralta, J.P. Functional characterisation of human microbiomes using metatranscriptomics; University of Toronto (Canada), 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Truong, D.T.; Franzosa, E.A.; Tickle, T.L.; Scholz, M.; Weingart, G.; Pasolli, E.; Tett, A.; Huttenhower, C.; Segata, N. MetaPhlAn2 for enhanced metagenomic taxonomic profiling. Nat Methods 2015, 12, 902–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abeltino, A.; Hatem, D.; Serantoni, C.; Riente, A.; De Giulio, M.M.; De Spirito, M.; De Maio, F.; Maulucci, G. Unraveling the gut microbiota: Implications for precision nutrition and personalized medicine. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, A.; De Vadder, F.; Kovatcheva-Datchary, P.; Bäckhed, F. From dietary fiber to host physiology: short-chain fatty acids as key bacterial metabolites. Cell 2016, 165, 1332–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, C.; Chon, H.; Ku, W.; Eom, S.; Seok, M.; Kim, S.; Lee, J.; Kim, D.; Lee, S.; Koo, H. Bile acids: major regulator of the gut microbiome. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agus, A.; Clément, K.; Sokol, H. Gut microbiota-derived metabolites as central regulators in metabolic disorders. Gut 2021, 70, 1174–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, T.R.; Powers, J.H. Biomarkers and surrogate endpoints in clinical trials. Statistics in medicine 2012, 31, 2973–2984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyvisch, P. Surrogate marker evaluation in clinical trials using methods of causal inference; KU Leuven, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- McFarland, L.V.; Evans, C.T.; Goldstein, E.J. Strain-specificity and disease-specificity of probiotic efficacy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in medicine 2018, 5, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioannidis, J.P. Why most published research findings are false. PLoS medicine 2005, 2, e124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food, U.; Administration, D. Clinical trial endpoints for the approval of cancer drugs and biologics. Guidance for industry, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Enck, P.; Bingel, U.; Schedlowski, M.; Rief, W. The placebo response in medicine: minimize, maximize or personalize? Nature reviews Drug discovery 2013, 12, 191–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaptchuk, T.J.; Miller, F.G. Placebo effects in medicine. New England Journal of Medicine 2015, 373, 8–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Enck, P.; Klosterhalfen, S. The placebo response in functional bowel disorders: perspectives and putative mechanisms. Neurogastroenterology & Motility 2005, 17, 325–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiegel, B.; Bolus, R.; Harris, L.; Lucak, S.; Naliboff, B.; Esrailian, E.; Chey, W.; Lembo, A.; Karsan, H.; Tillisch, K. Measuring irritable bowel syndrome patient-reported outcomes with an abdominal pain numeric rating scale. Alimentary pharmacology & therapeutics 2009, 30, 1159–1170. [Google Scholar]

- Black, C.J.; Ford, A.C. Global burden of irritable bowel syndrome: trends, predictions and risk factors. Nature reviews Gastroenterology & hepatology 2020, 17, 473–486. [Google Scholar]

- Bischoff, S.C.; Barbara, G.; Buurman, W.; Ockhuizen, T.; Schulzke, J.-D.; Serino, M.; Tilg, H.; Watson, A.; Wells, J.M. Intestinal permeability–a new target for disease prevention and therapy. BMC gastroenterology 2014, 14, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasriya, V.L.; Samtiya, M.; Ranveer, S.; Dhillon, H.S.; Devi, N.; Sharma, V.; Nikam, P.; Puniya, M.; Chaudhary, P.; Chaudhary, V. Modulation of gut-microbiota through probiotics and dietary interventions to improve host health. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture 2024, 104(11), 6359–6375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gotzsche, P.; Hrobjartsson, A. Placebo interventions for all clinical conditions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev Published. 2010, 2010(1), CD003974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, L.A.; Maurice, C.F.; Carmody, R.N.; Gootenberg, D.B.; Button, J.E.; Wolfe, B.E.; Ling, A.V.; Devlin, A.S.; Varma, Y.; Fischbach, M.A. Diet rapidly and reproducibly alters the human gut microbiome. Nature 2014, 505, 559–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonnenburg, E.D.; Sonnenburg, J.L. Starving our microbial self: the deleterious consequences of a diet deficient in microbiota-accessible carbohydrates. Cell Metab 2014, 20, 779–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.D.; Chen, J.; Hoffmann, C.; Bittinger, K.; Chen, Y.-Y.; Keilbaugh, S.A.; Bewtra, M.; Knights, D.; Walters, W.A.; Knight, R. Linking long-term dietary patterns with gut microbial enterotypes. Science 2011, 334, 105–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szajewska, H.; Scott, K.P.; de Meij, T.; Forslund-Startceva, S.K.; Knight, R.; Koren, O.; Little, P.; Johnston, B.C.; Łukasik, J.; Suez, J. Antibiotic-perturbed microbiota and the role of probiotics. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology 2025, 22, 155–172. [Google Scholar]

- Cusumano, G.; Flores, G.A.; Venanzoni, R.; Angelini, P. The Impact of Antibiotic Therapy on Intestinal Microbiota: Dysbiosis, Antibiotic Resistance, and Restoration Strategies. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, X.; Zhang, X.; Wang, J.; Liu, Y.; Yan, H.; Xing, X.; Yang, J. Proton pump inhibitors alter gut microbiota by promoting oral microbiota translocation: a prospective interventional study. Gut 2024, 73, 1098–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forslund, K.; Hildebrand, F.; Nielsen, T.; Falony, G.; Le Chatelier, E.; Sunagawa, S.; Prifti, E.; Vieira-Silva, S.; Gudmundsdottir, V.; Krogh Pedersen, H. Disentangling type 2 diabetes and metformin treatment signatures in the human gut microbiota. Nature 2015, 528, 262–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le Bastard, Q.; Berthelot, L.; Soulillou, J.-P.; Montassier, E. Impact of non-antibiotic drugs on the human intestinal microbiome. Expert Review of Molecular Diagnostics 2021, 21, 911–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeevi, D.; Korem, T.; Zmora, N.; Israeli, D.; Rothschild, D.; Weinberger, A.; Ben-Yacov, O.; Lador, D.; Avnit-Sagi, T.; Lotan-Pompan, M. Personalized nutrition by prediction of glycemic responses. Cell 2015, 163, 1079–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suez, J.; Korem, T.; Zeevi, D.; Zilberman-Schapira, G.; Thaiss, C.A.; Maza, O.; Israeli, D.; Zmora, N.; Gilad, S.; Weinberger, A. Artificial sweeteners induce glucose intolerance by altering the gut microbiota. Nature 2014, 514, 181–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodland, B.; Farrell, L.A.; Brockbals, L.; Rezcallah, M.; Brennan, A.; Sunnucks, E.J.; Gould, S.T.; Stanczak, A.M.; O’Rourke, M.B.; Padula, M.P. Sample Preparation for Multi-Omics Analysis: Considerations and Guidance for Identifying the Ideal Workflow. Proteomics 2025, 25(21-22), 76–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, T.; Niu, G.; Chen, T.; Shen, Q.; Yuan, J.; Liu, Y.-X. The best practice for microbiome analysis using R. Protein & cell 2023, 14, 713–725. [Google Scholar]

- Knight, R.; Vrbanac, A.; Taylor, B.C.; Aksenov, A.; Callewaert, C.; Debelius, J.; Gonzalez, A.; Kosciolek, T.; McCall, L.-I.; McDonald, D. Best practices for analysing microbiomes. Nature Reviews Microbiology 2018, 16, 410–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinha, R.; Abu-Ali, G.; Vogtmann, E.; Fodor, A.A.; Ren, B.; Amir, A.; Schwager, E.; Crabtree, J.; Ma, S.; Abnet, C.C.; et al. Assessment of variation in microbial community amplicon sequencing by the Microbiome Quality Control (MBQC) project consortium. Nat Biotechnol 2017, 35, 1077–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Button, K.S.; Ioannidis, J.P.; Mokrysz, C.; Nosek, B.A.; Flint, J.; Robinson, E.S.; Munafò, M.R. Power failure: why small sample size undermines the reliability of neuroscience. Nature reviews neuroscience 2013, 14, 365–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasserstein, R.L.; Lazar, N.A. The ASA statement on p-values: context, process, and purpose. 2016, 70, 129–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turnbaugh, P.J.; Ley, R.E.; Hamady, M.; Fraser-Liggett, C.M.; Knight, R.; Gordon, J.I. The Human Microbiome Project. Nature 2007, 449, 804–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonnenburg, J.L.; Bäckhed, F. Diet–microbiota interactions as moderators of human metabolism. Nature 2016, 535, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd-Price, J.; Mahurkar, A.; Rahnavard, G.; Crabtree, J.; Orvis, J.; Hall, A.B.; Brady, A.; Creasy, H.H.; McCracken, C.; Giglio, M.G. Strains, functions and dynamics in the expanded Human Microbiome Project. Nature 2017, 550, 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franzosa, E.A.; McIver, L.J.; Rahnavard, G.; Thompson, L.R.; Schirmer, M.; Weingart, G.; Lipson, K.S.; Knight, R.; Caporaso, J.G.; Segata, N. Species-level functional profiling of metagenomes and metatranscriptomes. Nature methods 2018, 15, 962–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).