Submitted:

04 January 2026

Posted:

05 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

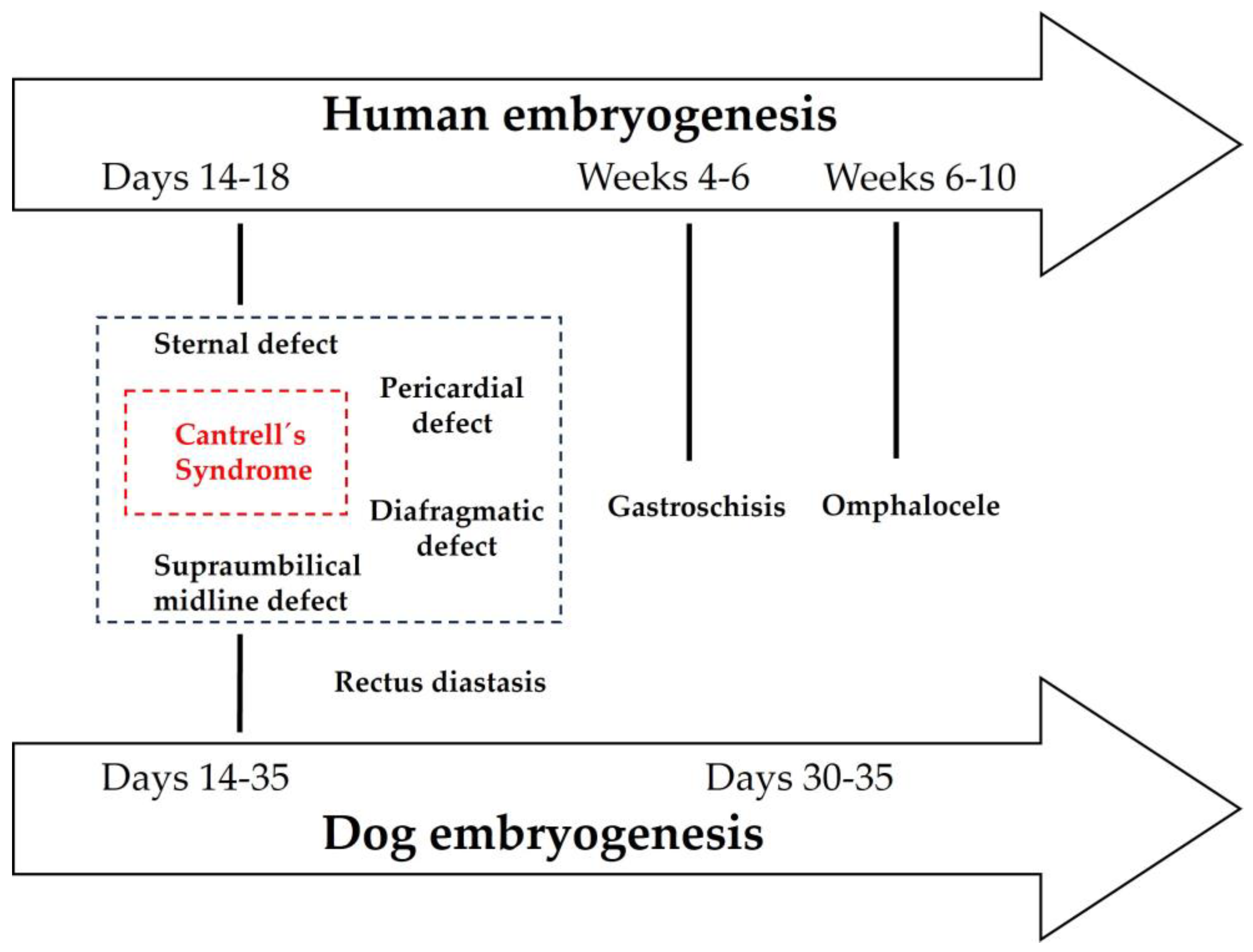

Keywords:

1. Introduction

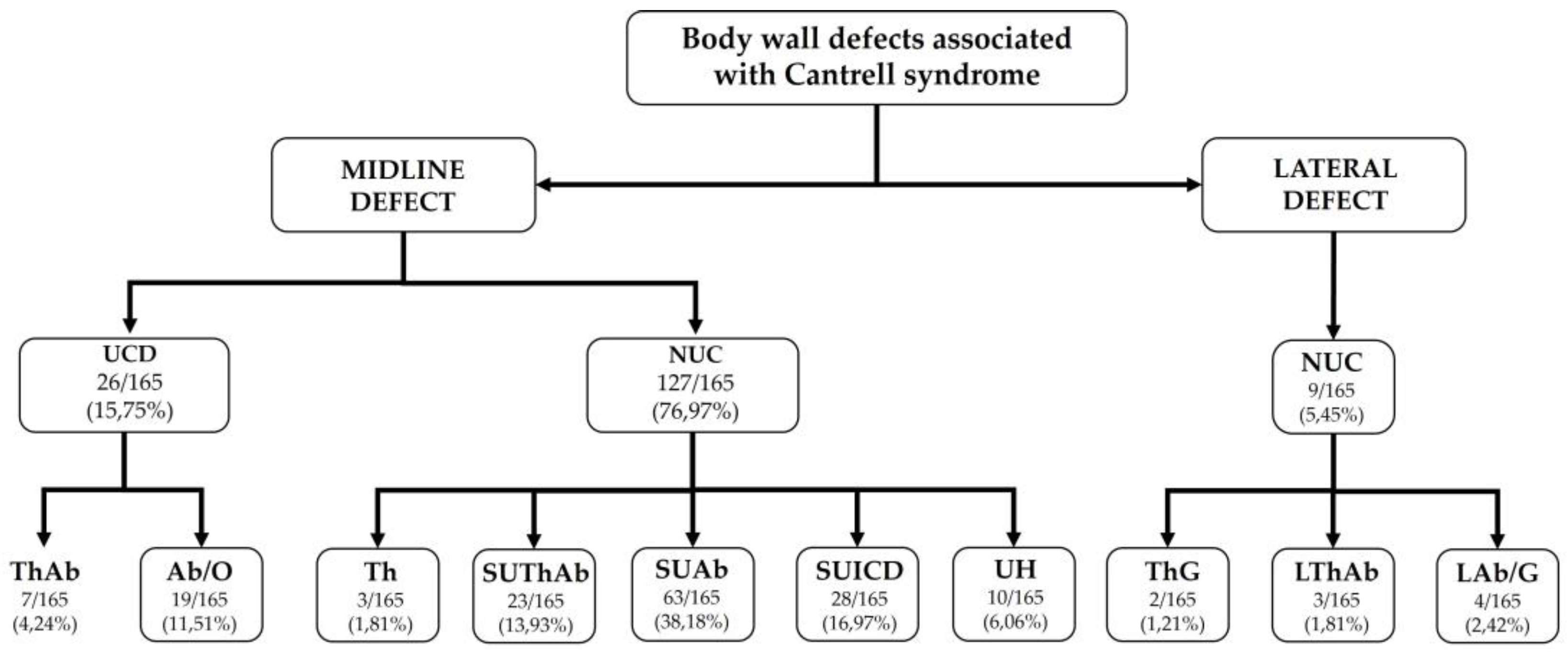

2. CS Classification

3. CS in Human Medicine

4. Veterinary Perspective: Ectopia Cordis and Cantrell’s Syndrome

5. Comparative Analysis: Applying Veterinary Classification to Human Cases

6. Embryological Insights and Pathogenetic Mechanisms

7. Discussion

8. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AA | Anal atresia |

| AAA | Aplasia of the aortic arch |

| AADT | Aortic arch dog type |

| AAH | Anterior abdominal hernia |

| Ab | Abdominoschisis |

| AbEC | Abdominal ectopia cordis |

| ABS | Amniotic band syndrome |

| ACP | Abnormal coiling pattern |

| AE | Adrenal ectopia |

| AH | Alobar holoprosencephaly |

| AMV | Atresia of the mitral valve |

| AN | Anencephaly |

| ASD | Atrial septal defect |

| AOP | Anophthalmia |

| APVR | Anomalous pulmonary venous return |

| AvC | Atrioventricular canal |

| AVS | Aortic valve stenosis |

| BAV | Bicuspid aortic valve |

| BCh | Bilateral cheiloschisis |

| BG | Bilobed gallbladder |

| BvD | Biventricular diverticulum |

| BvH | Biventricular hypertrophy |

| BWD | Body wall defect |

| CA | Cerebellar aplasia |

| CAWD | Cranioventral abdominal wall defect |

| Cch | Cranioschisis |

| CD | Cardiac defect |

| CDH | Congenital diaphragmatic hernia |

| Cf | Calf |

| CH | Cerebellar hypoplasia |

| CHD | Congenital heart disease |

| CHt | Cardiac heterotaxia |

| CL | Cleft lip |

| CM | Cardiomegaly |

| CoA | Coarctation of the aorta |

| CP | Cleft palate |

| Crch | Craniorachischisis |

| CrfD | Craniofacial dysmorphism |

| CS | Cantrell syndrome |

| CSq | Cantrell sequence |

| CSt | Colonic stenosis |

| Ct | Cat |

| CtD | Costal defect |

| CVCD | Cranial vena cava duplicated |

| CyH | Cystic hygroma |

| D | Dog |

| DA | Dextroposition of the aorta |

| DbA | Double apex |

| Dc | Dextrocardia |

| DD | Diaphragmatic defect |

| Di | Distorted at the umbilicus |

| DILV | Double-inlet left ventricle |

| DORV | Double-outlet right ventricle |

| DRM | Diastasis of the abdominal recti muscles |

| DTV | Dysplasia of the tricuspid valve |

| DUV | Dispersed umbilical vessels |

| EC | Ectopia cordis |

| Ecc | Encephalocele |

| EcC | Ectopic caecum |

| EcL | Ectopic liver |

| Ect | Ectrodactyly |

| Ee | Exencephaly |

| EH | Epigastric hernia |

| Ep | Epignathus |

| ExEC | External ectopia cordis |

| FK | Fibrotic kidneys |

| G | Gastrochisis |

| GA | Gallbladder agenesis |

| GEH | Grossly enlarged heart |

| GH | Globular heart |

| H | Hydrocephaly |

| HAs | Hypoplastic auricles |

| HCy | Hepatic cyst |

| HD | Hepatic defect |

| HF | Hepatic fibrosis |

| HHS | Hyperplastic and hard spleen |

| HLHS | Hypoplastic left heart syndrome |

| HLV | Hypoplasia of the left ventricle |

| HRVS | Hypoplastic right ventricle syndrome |

| HR | Hypoplastic ribs |

| HT | Hypertelorism |

| HUA | Hypoplastic umbilical artery |

| Hy | Hydramnios |

| ICD | Intracardiac defect |

| IDBK | Increased distance between the kidneys and the adrenal glands |

| IM | Intestinal malrotation |

| Lm | Lamb |

| L | Left |

| LAb | Lateral abdominoschisis |

| LAM | Liver amorphous mass without lobulation |

| LSVC to CS | Left superior vena cava draining to coronary sinus |

| L-SE | Low-set ears |

| LThAb | Lateral thoracoabdominoschisis |

| LVA | Left ventricular aneurysm |

| LVD | Left ventricular diverticulum |

| Mc | Mesocardia |

| MD | Musculoskeletical deformities |

| MOP | Microphthalmia |

| MVA | Mitral valve agenesis |

| MVS | Mitral valve stenosis |

| Myc | Myelomeningocele |

| NR | Non reported |

| NS | Non studied |

| NSt-GuD, | Non structural genitourinary defects |

| NSt-LD | Non structural limb defect |

| NSt-SpD | Non structural spinal defect |

| O | Omphalocele |

| OD | Other defects |

| OmT | Oromandiular tumor |

| ONTD | Open neural tube defect |

| P | Pig |

| PAA | Pulmonary artery atresia |

| PAH | Pulmonary artery hypoplasia |

| PCD | Pulmonary congenital defect |

| PD | Pericardial defect |

| PDA | Patent ductus arteriosus |

| PLSVC | Persistent left superior vena cava |

| PLCVC | Persistent left cranial vena cava |

| PP | Primary palatoschisis |

| PPDH | Peritoneo-pericardial diaphragmatic hernia |

| Ps | Polisplenia |

| PS | Pulmonary stenosis |

| PSDH | Pars sternalis diaphragmatic hernia |

| PTA | Persistent truncus arteriosus |

| R | Right |

| RAV | Right azygos vein |

| RD | Rectal diastasis |

| RVD | Right ventricular dilatation |

| RVH | Right ventricular hipertrofy |

| SA | Single atrium |

| Sc | Supercoiled |

| SCA | Single coronary artery |

| SIL | Situs inversus of the liver |

| SL | Split liver |

| SP | Secondary palatoschisis |

| SPV | Single pulmonary vein |

| SS | Situs solitus |

| St-GuD | Structural genitourinary defects |

| St-LD | Structural limb defect |

| St-SpD | Structural spinal defect |

| StD | Sternal defect |

| SUA | Single umbilical artery |

| SUAb | Supra-umbilical-abdominoschisis |

| SUICD | Supraumbilical incomplete central defect |

| SUThAb | Supra-umbilical-thoraco-abdominoschisis |

| SV | Single ventricle |

| TA | Tricuspid atresia |

| TF | Tetralogy of Fallot |

| TGA | Transposition of the great arteries |

| Th | Thoracoschisis |

| ThAb | Thoracoabdominoschisis |

| ThAbEC | Thoraco-abdominal ectopia cordis |

| ThG | Thoracogastroschisis |

| TRAPS | Twin reversed arterial perfusion sequence |

| TVD | Tricuspid valve dysplasia |

| U | Unilateral |

| Uc | Uncoiled |

| UCD | Umbilical cord defect |

| UH | Umbilical hernia |

| URC | Unroofed coronary sinus |

| VAD | Vena azygos duplicated |

| VD | Ventricular diverticulum |

| VEH | Ventral epigastric hernia |

| VH | Ventral hernia |

| VSD | Ventricular septal defect |

References

- Cantrell, J.R.; Haller, J.A.; Ravitch, M.M. A syndrome of congenital defects involving the abdominal wall, sternum, diaphragm, pericardium, and heart. Surg Gynecol Obstet 1958, 107, 602–614. [Google Scholar]

- Hori, A.; Roessmann, U.; Eubel, R.; Ulbrich, R.; Dietrich-Schott, B. Exencephaly in Cantrell-Haller-Ravitsch Syndrome. Acta Neuropathol (Berl) 1984, 65, 158–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zachariou, Z; Daum, R; Roth, H; Benz, G. Das Cantrellsche Syndrom [Cantrell’s syndrome]. Z Kinderchir 1987, 42, 255–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milne, L.W.; Morosin, A.M.; Campbell, J.R.; Harrison, M.W. Pars sternalis diaphragmatic hernia with omphalocele: a report of two cases. J Pediatr Surg 1990, 25, 726–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achiron, R.; Schimmel, M.; Farber, B.; Glaser, J. Prenatal sonographic diagnosis and perinatal management of ectopia cordis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 1991, 1, 431–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peer, D.; Moroder, W.; Delucca, A. Pränatale Diagnose einer Cantrellschen Pentalogie kombiniert mit Exenzephalie und Amnionbridensyndrom [Prenatal diagnosis of the pentalogy of Cantrell combined with exencephaly and amniotic band syndrome]. Ultraschall Med 1993, 14, 94–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdallah, H.I.; Marks, L.A.; Balsara, R.K.; Davis, D.A.; Russo, P.A. Staged repair of pentalogy of Cantrell with tetralogy of Fallot. Ann Thorac Surg 1993, 56, 979–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogers, A.J.; Hazebroek, F.W.; Hess, J. Left and right ventricular diverticula, ventricular septal defect and ectopia cordis in a patient with Cantrell’s syndrome. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 1993, 7, 334–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dembinski, J.; Heyl, W.; Steidel, K.; Hermanns, B.; Hörnchen, H.; Schröder, W. The Cantrell-sequence: a result of maternal exposure to aminopropionitriles? Am J Perinatol 1997, 14, 567–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, M.S.; López, A.; Vila, J.J.; Lluna, J.; Miranda, J. Cantrell’s pentalogy. Report of four cases and their management. Pediatr Surg Int 1997, 12, 428–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vazquez-Jimenez, J.F.; Muehler, E.G.; Daebritz, S.; Keutel, J.; Nishigaki, K.; Huegel, W.; Messmer, B.J. Cantrell’s syndrome: a challenge to the surgeon. Ann Thorac Surg 1998, 65, 1178–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsieh, Y.Y.; Lee, C.C.; Chang, C.C.; Tsai, H.D.; Hsu, T.Y.; Tsai, C.H. Prenatal sonographic diagnosis of Cantrell’s pentalogy with cystic hygroma in the first trimester. J Clin Ultrasound 1998, 26, 409–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katranci, A.O.; Semih Görk, A.; Rizalar, R.; Giinaydin, M.; Aritiirk, E.; Bernay, F.; Gürses, N. Pentalogy of Cantrell. Indian J Pediatr 1998, 65, 149–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laloyaux, P.; Veyckemans, F.; Van Dyck, M. Anaesthetic management of a prematurely born infant with Cantrell’s Pentalogy. Paediatric Anaesthesis 1998, 8, 163–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pivnick, E.K.; Kaufman, R.A.; Velagaleti, G.V.; Gunther, W.M.; Abramovici, D. Infant with midline thoracoabdominal schisis and limb defects. Teratology 1998, 58, 205–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, A.; McLeary, M.S. MR imaging of pentalogy of Cantrell variant with an intact diaphragm and pericardium. Pediatr Radiol 2000, 30, 638–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falcao, J.L.; Falcao, S.N.; Sawicki, W.C.; Liberatori, A.W.; Lopes, A.C. Cantrell syndrome. Case report of an adult. Arq Bras Cardiol 2000, 75, 323–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alayunt, A.; Yagdi, T.; Alat, I.; Posacioglu, H.; Büket, S. Left ventricular diverticulum associated with Cantrell’s syndrome and tetralogy of Fallot in an adult. Scand Cardiovasc J 2001, 35, 55–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halbertsma, F.J.; van Oort, A.; van der Staak, F. Cardiac diverticulum and omphalocele: Cantrell’s pentalogy or syndrome. Cardiol Young 2002, 12, 71–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- León, G.; Chedraui, P.; San Miguel, G. Prenatal diagnosis of Cantrell’s pentalogy with conventional and three-dimensional sonography. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2002, 12, 209–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, B.R.; Duran, M. The confused identity of Cantrell’s pentad: ectopia cordis is related either to thoracoschisis or to a diaphragmatic hernia with an omphalocele. Pediatr Pathol Mol Med 2003, 22, 383–390. [Google Scholar]

- Nanda, S.; Nanda, S.; Agarwal, U.; Sen, J.; Sangwan, K. Cantrell’s syndrome - report of two cases with one atypical variant. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2003, 268, 331–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bittmann, S.; Ulus, H.; Springer, A. Combined pentalogy of Cantrell with tetralogy of Fallot, gallbladder agenesis, and polysplenia: a case report. J Pediatr Surg 2004, 39, 107–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uygur, D.; Kiş, S.; Sener, E.; Günçe, S.; Semerci, N. An infant with pentalogy of Cantrell and limb defects diagnosed prenatally. Clin Dysmorphol 2004, 13, 57–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Bernardo, S.; Sekarski, N.; Meijboom, E. Left ventricular diverticulum in a neonate with Cantrell syndrome. Heart 2004, 90, 1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polat, I.; Gül, A.; Aslan, H.; Cebeci, A.; Ozseker, B.; Caglar, B.; Ceylan, Y. Prenatal diagnosis of pentalogy of Cantrell in three cases, two with craniorachischisis. J Clin Ultrasound 2005, 33, 308–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staboulidou, I.; Wüstemann, M.; Schmidt, P.; Günter, H.H.; Scharf, A. Erhöhte fetale Nackentransparenz als Prädiktor für eine Cantrellsche,Pentalogie – eine Kasuistik. Z Geburtsh Neonatol 2005, 209–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araujo Júnior, E.; Zanforlin Filho, S.M.; Guimarães Filho, H.A.; Pires, C.R.; Nardozza, L.M.; Moron, A.F. Diagnosis of Pentalogy of Cantrell by three-dimensional ultrasound in third trimester of pregnancy. A case report. Fetal Diagn Ther 2006, 21, 544–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- St Louis, J.D. Pentalogy of Cantrell associated with hypoplastic left heart syndrome and herniation of the ventricular mass into the abdominal cavity. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2006, 5, 200–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knirsch, W.; Dodge-Khatami, A.; Bolz, D.; Valsangiacomo Büchel, E. Cantrell’s Syndrome forme fruste in a newborn diagnosed by transthoracic echocardiography and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging. Pediatr Cardiol 2006, 27, 652–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marijon, E.; Hausse-Mocumbi, A.O.; Ferreira, B. Cantrell’s syndrome. Cardiol Young 2006, 16, 95–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grethel, E.J.; Hornberger, L.K.; Farmer, D.L. Prenatal and postnatal management of a patient with pentalogy of Cantrell and left ventricular aneurysm. A case report and literature review. Fetal Diagn Ther 2007, 22, 269–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wheeler, D.S.; St Louis, J.D. Pentalogy of Cantrell associated with hypoplastic left heart syndrome. Pediatr Cardiol 2007, 28, 311–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loureiro, T.; Oliveira, C.; Aroso, J.; Ferreira, M.J.; Vieira, J. Prenatal sonographic diagnosis of a rare Cantrell’s pentalogy variant with associated open neural tube defect - a case report. Fetal Diagn Ther 2007, 22, 172–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korver, A.M.; Haas, F.; Freund, M.W.; Strengers, J.L. Pentalogy of Cantrell: successful early correction. Pediatr Cardiol 2008, 29, 146–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chelli, D.; Dimassi, K.; Jallouli-Bouzguenda, S.; Ebdellah, E.; Hermi, F.; Zouaoui, B.; Sfar, E.; Kitova, T.; Chelli, H.; Channoufi, M.B.; Gaigi, S. Prenatal diagnosis of ectopia cordis: case report. Tunis Med 2008, 86, 171–173. [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto, Y.; Harada, Y.; Uchita, S. Fontan operation through a right lateral thoracotomy to treat Cantrell syndrome with severe ectopia cordis. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2008, 7, 278–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcì, M.; Ajovalasit, P.; Calvaruso, D.; Cipriani, A.; Lucente, M.; Petrucelli, D.; Marcelletti, C.F. Double-outlet right ventricle in a neonate with Cantrell’s syndrome. J Cardiovasc Med (Hagerstown) 2008, 9, 506–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.J.; Chen, F.L.; Ng, Y.Y.; Hu, J.M.; Chen, S.J.; Chen, J.Y.; Su, P.H. Trisomy 18 syndrome with incomplete Cantrell syndrome. Pediatr Neonatol 2008, 49, 84–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turbendian, H.K.; Carroll, S.J.; Chen, J.M. Repair of left ventricular diverticulum in setting of Cantrell’s syndrome. Cardiol Young 2008, 18, 532–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zidere, V.; Allan, L.D. Changing findings in pentalogy of Cantrell in fetal life. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2008, 32, 835–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.P.; Tzen, C.Y.; Chen, C.Y.; Tsai, F.J.; Wang, W. Concomitant exencephaly and limb defects associated with pentalogy of Cantrell. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol 2008, 47, 476–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Duan, Q.J.; Zhang, Z.W.; Ying, L.Y.; Ma, L.L. Images in cardiovascular medicine: Pentalogy of Cantrell associated with thoracoabdominal ectopia cordis. Circulation 2009, 119, e483-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitsukawa, N.; Yasunaga, H.; Tananari, Y. Chest wall reconstruction in a patient with Cantrell syndrome. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg 2009, 62, 814–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meeker, T.M. Pentalogy of Cantrell: reviewing the syndrome with a case report and nursing implications. J Perinat Neonatal Nurs 2009, 23, 186–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suehiro, K.; Okutani, R.; Ogawa, S.; Nakada, K.; Shimaoka, H.; Ueda, M.; Shigemoto, T. Perioperative management of a neonate with Cantrell syndrome. J Anesth 2009, 23, 572–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sowande, O.A.; Anyanwu, L.J.; Talabi, A.O.; Babalola, O.R.; Adejuyigbe, O. Pentalogy of cantrell: a report of three cases. J Surg Tech Case Rep 2010, 2, 20–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herman, T.E.; Siegel, M.J. Cantrell syndrome. J Perinatol 2010, 30, 298–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.; Bera, M.L.; Sachdev, M.S.; Aggarwal, N.; Joshi, R.; Kohli, V. Pentalogy of Cantrell with left ventricular diverticulum: a case report and review of literature. Congenit Heart Dis 2010, 5, 454–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quandt, D.; Dave, H.; Valsangiacomo Buechel, E. Heart with a trunk: form fruste of Cantrell’s Syndrome. Eur Heart J 2011, 32, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angoulvant, D.; Sanchez, I.; Boussel, L. Late diagnosis of incomplete Cantrell’s syndrome on CT scan. Arch Cardiovasc Dis 2011, 104, 208–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balderrábano-Saucedo, N.; Vizcaíno-Alarcón, A.; Sandoval-Serrano, E.; Segura-Stanford, B.; Arévalo-Salas, L.A.; de la Cruz, L.R.; Espinosa-Islas, G.; Puga-Muñuzuri, F.J. Pentalogy of Cantrell: Forty-two Years of Experience in the Hospital Infantil de Mexico Federico Gomez. World J Pediatr Congenit Heart Surg 2011, 2, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smigiel, R.; Jakubiak, A.; Lombardi, M.P.; Jaworski, W.; Slezak, R.; Patkowski, D.; Hennekam, R.C. Co-occurrence of severe Goltz-Gorlin syndrome and pentalogy of Cantrell - Case report and review of the literature. Am J Med Genet A 2011, 155A, 1102–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, L.; Jun-lin, L.; Jia, H.; Dong, Z.; Li-guang, Z.; Shu-hua, D.; Wei-jin, L.; Yun-hua, G. Cantrell syndrome with complex cardiac malformations: a case report. J Pediatr Surg 2011, 46, 1455–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brochut, A.C.; Baumann, M.U.; Kuhn, A.; Di; Naro, E; Tutschek, B.; Surbek, D.; Raio, L. Pentalogy or hexalogy of Cantrell? Pediatr Dev Pathol 2011, 14, 396–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranganath, P.; Pradhan, M. Complete Pentalogy of Cantrell with craniorachischisis: a case report. J Prenat Med 2012, 6, 10–12. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sakasai, Y.; Thang, B.Q.; Kanemoto, S.; Takahashi-Igari, M.; Togashi, S.; Kato, H.; Hiramatsu, Y. Staged repair of pentalogy of Cantrell with ectopia cordis and ventricular septal defect. J Card Surg 2012, 27, 390–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ergenoğlu, M.A.; Yeniel, A.Ö.; Peker, N.; Kazandı, M.; Akercan, F.; Sağol, S. Prenatal diagnosis of Cantrell pentalogy in first trimester screening: case report and review of literature. J Turk Ger Gynecol Assoc 2012, 13, 145–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinoshita, M.; Park, S.; Shiraishi, T.; Ueno, S. Thoracoabdominoplasty with umbilicoplasty for Cantrell’s syndrome. J Plast Surg Hand Surg 2012, 46, 367–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Kouache, M.; Labib, S.; El Madi, A.; Babakhoya, A.; Atmani, S.; Abouabdilah, Y.; Harandou, M. Left Ventricle Diverticulum with Partial Cantrell’s Syndrome. Case Rep Cardiol 2012, 2012, 309576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandran, S.; Ari, D. Pentalogy of Cantrell: an extremely rare congenital anomaly. J Clin Neonatol 2013, 2, 95–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.P.; Huang, M.C.; Chern, S.R.; Wu, P.S.; Su, J.W.; Wang, W. Discordant anencephaly and Cantrell syndrome in monozygotic twins conceived by ICSI and IVF-ET. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol 2013, 52, 297–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magadum, S.; Shivaprasad, H.; Dinesh, K.; Vijay, K. Incomplete Cantrell’s Pentalogy-A Case Report. Indian J Surg 2013, 75 Suppl 1, 350–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kachare, M.B.; Patki, V.K.; Saboo, S.S.; Saboo, S.H.; Ahlawat, K.; Saboo, S.S. Pentalogy of Cantrell associated with exencephaly and spinal dysraphism: antenatal ultrasonographic diagnosis. Case report. Med Ultrason 2013, 15, 237–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, H.; Ota, N.; Murata, M.; Sakamoto, K. Fontan operation for the Cantrell syndrome using a clamshell incision. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2013, 17, 754–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puvabanditsin, S.; Di Stefano, V.; Garrow, E.; Wong, R.; Eng, J.; Balbin, J. Case Report Ectopia cordis, Hong Kong. Med J 2013, 19, 447–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaouthar, H.; Jihen, A.; Faten, J.; Hela, M.; Fatma, O.; Lilia, C.; Rafik, B. Cardiac anomalies in Cantrell’s pentalogy: From ventricular diverticulum to complete thoracic ectopia cordis. Cardiol Tunis 2013, 9, 94–97. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cakiroglu, Y.; Doger, E.; Yildirim Kopuk, S.; Babaoglu, K.; Caliskan, E.; Yucesoy, G. Prenatal Diagnosis of Cantrell’s Pentalogy Associated with Agenesis of Left Limb in a Twin Pregnancy. Case Rep Obstet Gynecol 2014, 2014, 314284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kheir, A.E.M.; Bakhiet, E.A.; Elhag Karrar, M.Z. Pentalogy of Cantrell: case report and review of the literature. Sudan J Paediatr 2014, 14, 85–88. [Google Scholar]

- Restrepo, M.S.; Cerqua, A.; Turek, J.W. Pentalogy of Cantrell with ectopia cordis totalis, total anomalous pulmonary venous connection, and tetralogy of Fallot: a case report and review of the literature. Congenit Heart Dis 2014, 9, E129-34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Xing, Q.; Sun, J.; Hou, X.; Kuang, M.; Zhang, G. Surgical treatment and outcomes of pentalogy of Cantrell in eight patients. J Pediatr Surg 2014, 49, 1335–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pirasteh, A.; Carcano, C.; Kirsch, J.; Mohammed, T.L. Pentalogy of Cantrell with Ectopia Cordis: CT Findings. J Radiol Case Rep 2014, 8, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naburi, H.; Assenga, E.; Patel, S.; Massawe, A.; Manji, K. Class II pentalogy of Cantrell. BMC Res Notes 2015, 8, 318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Timur, H.; Tokmak, A.; Bayram, H.; Şükran Çakar, E.; Danışman, N. Coincidence of Incomplete Pentalogy of Cantrell and Meningomyelocele in a Dizygotic Twin Pregnancy. Case Rep Obstet Gynecol 2015, 2015, 629561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Türkçapar, A.F.; Sargın Oruc, A.; Öksüzoglu, A.; Danışman, N. Diagnosis of pentalogy of cantrell in the first trimester using transvaginal sonography and color Doppler. Case Rep Obstet Gynecol 2015, 2015, 179298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madžarac, V.; Matijević, R.; Škrtić, A.; Duić, Ž.; Fistonić, N.; Partlm, J.Z. Pentalogy of Cantrell with Unilateral Kidney Evisceration: A Case Report and Review of Literature. Fetal Pediatr Pathol 2016, 35, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Jiang, Z.; Ding, F. One-stage surgical treatment for Cantrell syndrome without repairing the left ventricular diverticulum: a case report. Cardiol Young 2016, 26, 191–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meena, R.; Meena, V. Pentalogy of Cantrell with single umbilical artery: a rare fetal anomaly. Int J Contemp Pediatr 2016, 4, 280–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zani-Ruttenstock, E.; Zani, A.; Honjo, O.; Chiu, P. Pentalogy of Cantrell: Is Echocardiography Sufficient in the Neonatal Period? European J Pediatr Surg Rep 2017, 5, e9–e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pius, S.; Abubakar Ibrahim, H.; Bello, M.; Bashir Tahir, M. Complete Ectopia Cordis: A Case Report and Literature Review. Case Rep Pediatr 2017, 2017, 1858621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salinas-Torres, V.M.; De La O-Espinoza, E.A.; Salinas-Torres, R.A. Severe Intrauterine Amputations in One Dichorionic Twin With Pentalogy of Cantrell: Further Evidence and Consideration for Mechanical Teratogenesis. Pediatr Dev Pathol 2017, 20, 440–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swarray-Deen, A.; Seffah, J.D.; Antwi-Agyei, D.A. Two cases of Pentalogy of Cantrell diagnosed antenatally at Korle Bu Teaching Hospital, Accra. Ghana Med J 2017, 51, 191–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mărginean, C.; Mărginean, C.O.; Gozar, L.; Meliţ, L.E.; Suciu, H.; Gozar, H.; Crişan, A.; Cucerea, M. Cantrell Syndrome-A Rare Complex Congenital Anomaly: A Case Report and Literature Review. Front Pediatr 2018, 6, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grigore, M.; Furnica, C.; Esanu, I.; Gafitanu, D. Pentalogy of Cantrell associated with unilateral anophthalmia: Case report and literature review. Medicine (Baltimore) 2018, 97(31), e11511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubbard, R.; Hayes, S.; Gillis, H.; Lindsey, S.; Malhotra, P.; Wani, T.; Tobias, J.D.; Beltran, R. Management challenges in an infant with Pentalogy of Cantrell, giant anterior encephalocele, and craniofacial anomalies: A Case Report. A A Pract 2018, 11, 238–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madi, J.M.; Festugatto, J.R.; Rizzon, M.; Agostini, A.P.; Araújo, B.F.; Garcia, R.M.R. Ectopia Cordis Associated with Pentalogy of Cantrell-A Case Report. Rev Bras Ginecol Obstet 2019, 41, 352–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delgado, A. L.; Matongo, K. M.; Dumo, B.; Mzayiya, N.; Mrara, B. Pentalogy of Cantrell with Total Ectopia Cordis and a Major Omphalocele—A Case Report. J Pharm Pharmacol 2019, 7, 621–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kylat, R.I. Complete and Incomplete Pentalogy of Cantrell. Children (Basel) 2019, 6(10), 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz-Serani, R.; Sepulveda, W. Trisomy 18 in a First-Trimester Fetus with Thoraco-Abdominal Ectopia Cordis. Fetal Pediatr Pathol 2020, 39, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zvizdic, Z.; Sefic-Pasic, I.; Mesic, A.; Terzic, S.; Vranic, S. The complete spectrum of pentalogy of Cantrell in one of a set of dizygotic twins: A case report of a rare congenital anomaly. Medicine (Baltimore). 2021, 100, e25470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desikan, S.; Coumary, A. S.; Habeebullah, S. Pentalogy of Cantrell with encephalocele – A case report with review of literature. Indian J Obstet Gynecol Res 2021, 8, 275–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, N. A Baby Born with Ectopia Cordis, Omphalocele, Cleft Lips and Palate: A Case Report. JNMA J Nepal Med Assoc 2022, 60, 183–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulistyowati, R.; Sensusiati, A.D. Radiological findings of partial expression pentalogy of Cantrell and other multiple congenital anomalies: A rare case report. Radiol Case Rep 2022, 17, 3172–3178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazea, M.; Alhameli, M.; Ahmed, F.; Askarpour, M.R; Murshed, W.; Jarwsh, A.; Alkbous, A. Pentalogy of Cantrell Associated with Ectopia Cordis: A Case Report. Pediatric Health Med Ther 2022, 13, 283–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, D.; Zheng, B.; Zhai, B.; Mo, J.; Yang, K.; Huo, Y. Clinical and ultrasound findings of pentalogy of Cantrell in a newborn: A case report. Front Pediatr 2022, 10, 998495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, J.; Huang, H.; Li, X. Surgical treatment of neonatal Cantrell pentalogy: a case report and literature review. AME Case Rep 2023, 7, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mraihi, F.; Basly, J.; Mezni, A.; Ghali, Z.; Hafsi, M.; Chelli, D. The pentalogy of Cantrell: A rare and challenging prenatal diagnosis. Int J Surg Case Rep 2023, 112, 108941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faisal, N.; Jeyakumar, P.; Pandey, N.N.; Choudhary, S.K.; Reddy, P.R.; Ramakrishnan, S. Pulsating abdominal mass in a newborn - Pentalogy of Cantrell with left ventricular diverticulum. Ann Pediatr Cardiol 2023, 16, 475–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabijan, A.; Korabiewska-Pluta, S.; Puzio, T.; Polis, B.; Moszura, T. Images of Extremely Rare Cantrell Phenomenon. Diagnostics (Basel). 2024, 14, 1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garofalo, S.; Guanà, R.; Suteu, L.; Alhellani, H.; Cortese, M.G.; Lonati, L.; Gennari, F. Epignathus and thoracoabdominal ectopia cordis in a neonate. Pediatr Neonatol 2024, 65, 410–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dusuri, E.; Asante, C.G.; Gyamfi, B.A.; Nartey, E.T.; Amaning, O.A.; Arkorful, J. Complete pentalogy of Cantrell associated with ectopia cordis and multiple anomalies: A case report from a low-resource setting. Radiol Case Rep 2025, 20, 1948–1952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maheshwari, V.; Sahoo, M. Anesthesia for Pentalogy of Cantrell with Surgical Repair of Tetralogy of Fallot Along with Absent Diaphragm: A Case Study. Ann Card Anaesth 2025, 28, 181–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martadiansyah, A.; Bernolian, N.; Mirani, P.; Lestari, P.M.; Nugraha, A.; Stevanny, B. Complex management of ectopia cordis complicated by pentalogy of cantrell: Report of two cases and review of current evidence. Int J Surg Case Rep 2025, 131, 111353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cozar, J.M.; Avedillo, L.; Martín-Alguacil, N. Embryonic Disruption Syndromes in Dogs: Exploring the Overlap and Divergence of Cantrell Syndrome, Amniotic Bands, and Body Stalk Anomalies. Preprint.org 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Alguacil, N.; Avedillo, L. Cantrell Syndrome (Thoracoabdominal Ectopia Cordis; Anomalous Umbilical Cord; Diaphragmatic, Pericardial and Intracardiac Defects) in the Pig (Sus scrofa domesticus). J Comp Pathol 2020, 174, 99–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pechriggl, E.; Blumer, M.; Tubbs, R.S.; Olewnik, Ł.; Konschake, M.; Fortélny, R.; Stofferin, H.; Honis, H.R.; Quinones, S.; Maranillo, E.; Sanudo, J. Embryology of the Abdominal Wall and Associated Malformations-A Review. Front Surg 2022, 9, 891–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solerte, M.L.; Cosmi, E. Abdominal Wall Defects in Prenatal Medicine. Ann Hematol Oncol 2022, 9(2), 1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- So, W.; Donahoe, S.L.; Podadera, J.M.; Mazrier, H. Pentalogy of Cantrell in Two Neonate Littermate Puppies: A Spontaneous Animal Model Suggesting Familial Inheritance. Animals (Basel) 2023, 13, 2091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuaire Noack, L. New clues to understand gastroschisis. Embryology, pathogenesis and epidemiology. Colomb Med (Cali) 2021, 52(3), e4004227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lammer, E.J.; Iovannisci, D.M.; Tom, L.; Schultz, K.; Shaw, G.M. Gastroschisis: a gene-environment model involving the VEGF-NOS3 pathway. Am J Med Genet C 2008, 148c(3), 213–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubinsky, M. A vascular and thrombotic model of gastroschisis. Am J Med Genet A 2014, 164A(4), 915–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoyme, H.E.; Jones, M.C.; Jones, K.L. Gastroschisis: abdominal wall disruption secondary to early gestational interruption of the omphalomesenteric artery. Semin Perinatol 1983, 7(4), 294–8. [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson, R.E.; Rogers, R.C.; Chandler, J.C.; Gauderer, M.W.; Hunter, A.G. Escape of the yolk sac: a hypothesis to explain the embryogenesis of gastroschisis. Clin Genet 2009, 75(4), 326–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Alguacil, N.; Avedillo, L. Body Wall Defects: Gastroschisis and Omphalocoele in Pigs (Sus scrofa domesticus). J Comp Pathol 2020, 175, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martín-Alguacil, N.; Avedillo, L. Body wall defects and amniotic band syndrome in pig (Sus scrofa domesticus). Anat Histol Embryol 2020, 49, 144–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Issa, R.; Kirby, M. Heart field: from mesoderm to heart tube. Ann Rev Cell Devel Biol 2007, 23, 45–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Adelstein, R.S. A point mutation in Myh10 causes major defects in heart development and body wall closure. Circ Cardiovasc Genet 2014, 7(3), 257–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeuchi, K.; Fujita, I.; Nakajima, K.; Kitagaki, S.; Koketsu, I. Body stalk anomaly: prenatal diagnosis. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 1995, 51, 49–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, M.L.; Couto, E.; Furlan, E.; Zaccaria, R.; Andrade, K.; Barini, R.; Nomura, M.L. Body stalk anomaly: adverse maternal outcomes in a series of 21 cases. Prenat Diagn 2012, 32, 264–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocherla, K.; Kumari, V.; Kocherla, P. Prenatal diagnosis of body stalk complex: A rare entity and review of literature. Indian J Radiol Imaging 2015, 25, 67–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gică, N.; Apostol, L.M.; Huluță, I.; Panaitescu, A.M.; Vayna, A.M.; Peltecu, G.; Gana, N. Body Stalk Anomaly. Diagnostics (Basel). 2024, 14(5), 518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Alguacil, N.; Avedillo, L. Body stalk anomalies in pig-Definition and classification. Mol Genet Genomic Med 2020, 8(6), e1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Alguacil, N. Anatomy-based diagnostic criteria for complex body wall anomalies (CBWA). Mol Genet Genomic Med 2020, 8(10), e1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martín-Alguacil, N.; Cozar, J.M.; Avedillo, L. Complex Body Wall Closure Defects in Seven Dog Fetuses: An Anatomic and CT Scan Study. Animals (Basel) 2025, 15(14), 2030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martín-Alguacil, N.; Cozar, J.M.; Avedillo, L. Body stalk anomalies and their relationship to amniotic band disruption complex in six cats. J Feline Med Surg 2025, 27(6), 1098612X251341068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Alguacil, N.; Cozar, J.M.; Avedillo, L.J. Body Stalk Anomalies in Pigs: Current Trends and Future Directions in Classification. Animals (Basel) 2025, 15(3), 460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, H. C. Repair of Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia and Umbilical Hernia in a Dog. JAVMA 1960, 136, 559–560. [Google Scholar]

- Bellah, J.R.; Spencer, C.P.; Brown, D.J.; Whitton, D.L. Congenital cranioventral abdominal wall, caudal sternal, diaphragmatic, pericardial, and intracardiac defects in Cocker Spaniel littermates. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1989, 194, 1741–1746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benlloch-Gonzalez, M.; Poncet, C. Sternal Cleft Associated with Cantrell’s Pentalogy in a German Shepherd Dog. J Am Anim Hosp Asso 2015, 51, 279–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Sajik, D.; Calvo, I.; Philips, A. Novel peritoneopericardial diaphragmatic hernia in a dog. Vet Rec Case Rep 2019, 7(3), e000896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, P.; Booth, M.; Rossanese, M. Incomplete pentalogy of Cantrell in a Border terrier puppy. Vet Rec Case Rep 2020, 8, e001188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennink, I.; Düver, P.; Rytz, U.; Meneses, F.; Moioli, M.; Adamik, K.N.; Kovacevic, A. Case Report: Unusual Peritoneopericardial Diaphragmatic Hernia in an 8-Month-Old German Shepherd Dog, Associated With a Pericardial Pseudocyst and Coexisting Severe Pericardial Effusion Resulting in Right-Sided Heart Failure. Front Vet Sci 2021, 8, 673543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozdemir-Salci, E. S.; Yildirim, K. Thoracic ectopia cordis, sternal agenesis, partial ectopia hepatica and fissure abdominalis in a German Shepherd puppy with milder incomplete pentalogy of Cantrell. Clinical case. Revista Científica, FCV-LUZ 2024, XXXIV, rcfcv–e34306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, M.M.; Kuzma, A.B.; Margiocco, M.L.; Cheng, T.; Enberg, T.B.; Head, L. Cardiac malposition (ectopia cordis) in a cat. J Vet Emerg Crit Care (San Antonio) 2015, 25, 783–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eiger, S.N.; Mison, M.B.; Aronson, L.R. Congenital sternal defect repair in an adult cat with incomplete pentalogy of Cantrell. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2019, 254, 1099–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokkinos, P.; Pratschke, K. Combined pentalogy of Cantrell with ectrodactyly and surgical implant-free repair of a sternal cleft and supraumbilical hernia in an adult cat. Vet Rec Case Reports 2022, 10, e364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiraga, T.; Abe, M.; Iwasa, K.; Takehana, K.; Tanigaki, A. Cervico-pectoral ectopia cordis in two Holstein calves. Vet Pathol 1993, 30, 529–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Windberger, U.; Forstenpointner, G.; Grabenwöger, F.; Kopp, E.; Künzel, W.; Mayr, B.; Pernthaner, A.; Simon, P.; Losert, U. Cardiac function, morphology and chromosomal aberrations in a calf with ectopia cordis cervicalis. Zentralbl Veterinarmed A 1992, 39, 759–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eröksüz, H.; Metin, N.; Eröksüz, Y. Total pectoral ectopia cordis and other congenital malformations in a calf. Vet Rec 1998, 142, (16):437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Floeck, M.; Weissengruber, G.E.; Froehlich, W.; Forstenpointner, G.; Shibly, S.; Hassan, J.; Franz, S.; Polsterer, E. First report of pentalogy of Cantrell in a calf: a case report. Vet Med - Czech 2008, 53, 676–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onda, K.; Sugiyama, M.; Niho, K.; Sato, R.; Arai, S.; Kaneko, K.; Ito, S.; Muto, M.; Suganuma, T.; Wakao, Y.; Wada, Y. Long-term survival of a cow with cervical ectopia cordis. Can Vet J 2011, 52, 667–669. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cerqueira, L.A.; Mâcedo, I.L; Sousa, D.E.R.; Amorim, H.A.L.; Borges, J.R.J.; Ximenes, F.H.B.; Câmara, A.C.L.; Castro, M.B. Complete Thoracic Ectopia Cordis in Two Lambs. Animals (Basel) 2024, 14(15), 2213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scaal, M. Development of the amniote ventrolateral body wall. Dev Dynam 2020, 250, 39–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmona, R.; Cañete, A.; Cano, E.; Ariza, L.; Rojas, A.; Muñoz-Chápuli, R. Conditional deletion of WT1 in the septum transversum mesenchyme causes congenital diaphragmatic hernia in mice. eLife 2016, 5, e16009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clugston, R.; Greer, J. Diaphragm development and congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Semin Pediatr Surg 2007, 16, 94–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadler, T. The embryologic origin of ventral body wall defects. Semin Pediatr Surg 2010, 19, 209–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Formstone, C.; Aldeiri, B.; Davenport, M.; Francis-West, P. Ventral body wall closure: Mechanistic insights from mouse models and translation to human pathology. Dev Dynam 2024, 254, 102–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, G.; Arias, M.; Sutherland, A. The primitive streak and cellular principles of building an amniote body through gastrulation. Science 2021, 374(6572), abg1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holst, P.; Phemister, R. The prenatal development of the dog: preimplantation events. BOR 1971, 5, 194–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pretzer, S. Canine embryonic and fetal development: a review. Theriogenology 2008, 70, 300–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueda, Y.; Yamada, S.; Uwabe, C.; Kose, K.; Takakuwa, T. Intestinal Rotation and Physiological Umbilical Herniation During the Embryonic Period. Anat Rec 2016, 299, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginzel, M.; Martynov, I.; Haak, R.; Lacher, M.; Kluth, D. Midgut development in rat embryos using microcomputed tomography. Commun Biol 2021, 4(1), 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldeiri, B.; Roostalu, U.; Albertini, A.; Behnsen, J.; Wong, J.; Morabito, A.; Cossu, G. Abrogation of TGF-beta signalling in TAGLN expressing cells recapitulates Pentalogy of Cantrell in the mouse. Sci Rep 2018, 8(1), 3658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goetzinger, K. Pentalogy of Cantrell. Obstetric Imaging: Fetal Diagnosis and Care (Second Edition); Copel, JA, Dálton, ME, Tutschek, B., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, Netherlands, 2018; pp. pp 567–569.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palacios, M.; Idrobo, B.; Mosquera, L.; Soler, J. Pentalogy of Cantrell. A stillbirth case report. Case reports 2022, 253357363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmi, R.; Boughman, J.A. Pentalogy of Cantrell and associated midline anomalies: a possible ventral midline developmental field. Am J Med Genet 1992, 42, 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duhamel, B. Embryology of exomphalos and allied malformations. Arch Dis Child 1963, 38, 142–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arraf, A.; Yelin, R.; Reshef, I.; Kispert, A.; Schultheiss, T. Establishment of the visceral embryonic midline is a dynamic process that requires bilaterally symmetric BMP signalling. Dev Cell 2016, 37, 571–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arraf, A.; Yelin, R.; Reshef, I.; Jadon, J.; Abboud, M.; Zaher, M.; Schneider, J.; Vladimirov, F.; Schultheiss, T. Hedgehog signalling regulates epithelial morphogenesis to position the ventral embryonic midline. Developmental Cell 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Type | Definition | Umbilical Cord | Associated defects |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Midline Defects | UThAb | Umbilical thoracoabdominoschisis | Abnormal (omphalocele) | |

| SUThAb | Supraumbilical thoracoabdominoschisis | Normal | ||

| Th | Thoracoschisis | Normal | Sternal defect | |

| SUStAb | Supraumbilical sternal abdominoschisis | Normal | ||

| UAb+DD | Umbilical abdominoschisis | Abnormal (omphalocele) | Diaphragmatic defect | |

| SUAb+DD | Supraumbilical abdominoschisis | Normal | Diaphragmatic hernia | |

| SUICD | Supraumbilical incomplete central defect | Normal | Sternal defect | |

| UH+DD | Umbilical hernia | Normal | Diaphragmatic defect | |

| Lateral Defects | LTHAb |

Lateral thoracoabdominoschisis | Normal | |

| LTh | Lateral toracho | Normal | ||

| LAb | Lateral abdominoschisis | Normal (gastroschisis) |

| AUTHOR(S) | Case / Gender | BWD | UCD | StD | DD | PD | CD | ExEC | OD | AUTHOR’S DIAGNOSIS | PROPOSED DIAGNOSIS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hori et al., 1984 [2] |

Case 1 ♀ |

ThAb | NR (+) |

NR | + | + | AAA | Type 1 | Ee, AE, Cch, CA, St-SpD | Ee in Cantrell-Haller-Ravitsch Syndrome | PC Class 2 BSA Type VI SPBWC III |

| Peer et al., 1993 [6] |

Case 17 ♂ |

ThAb | + SUA |

+ | + | NR | PDA, MVA, ASD | Type 1 | Ee, CL, CP, ABS | PC with Ee and ABS | PC Class 2 BSA Type VI STBWC III ABS |

| Kachare et al., 2013 [64] |

Case 113 NS |

O (ThAb) |

NR (+) |

+ | + | NR | VSD | Type 3 | Ee, St-SpD | PC with Ee and SpDs | PC Class 2 BSA Type V SSBWC III |

| Cakiroglu et al., 2014 [68] |

Case 119 ♀ |

(ThAb) | NR (+) |

+ | NR | NR | NR | Type 2 | HR, St-LD, St-SpD | PC associated with LD | BSA Type V SPLBWC III |

| Kheir et al., 2014 [69] |

Case 120 AG |

SUAb (ThAb) |

NR (+) |

+ | + | NR | NR | Type 1 | AA, St-GuD, NSt-LD | PC | BSA Type II STBWC I |

| Diaz-Serani and Sepulveda, 2020 [89] |

Case 146 ♂ |

ThAb | + SUA Cyst |

NR | NR | NR | NR | + | CL, CP, St-LD | ThAbEC | EC |

| Mraihi et al., 2023 [97] |

Case 158 C1, ♀ |

ThAb | + | + | + | NR | NR | Type 1 | NR | PC | BSA Type VI STBWC III |

| AUTHOR(S) | Case / Gender | BWD | UCD | StD | DD | PD | CD | ExEC | OD | AUTHOR’S DIAGNOSIS | PROPOSED DIAGNOSIS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Davies and Duran, 2003 [21] |

Case 37 C4, NS |

Th | - | + | NR | + | NR | Type 3 | NR | PC | PC Class 3 |

| Pius et al., 2017 [80] |

Case 137 ♀ |

Th | - | + | NR | + | NR | Type 3 | NR | EC | EC |

| Sulistyowati and Sensusiati, 2022 [90] |

Case 154 ♀ |

Th | - | + | + | ASD, VSD | Type 3 | BCL, CP, CrfD, ABS | PC | PC Class 2 |

| AUTHOR(S) | Case / Gender | BWD | UCD | StD | DD | PD | CD | ExEC | OD | AUTHOR’S DIAGNOSIS | PROPOSED DIAGNOSIS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zachariou et al., 1987 [3] |

Case 3 S.D., ♂ |

O (Ab) |

+ | NR | + | + | TF | Type 1 | NR | PC | PC Class 2 |

| Case 4 F.M., ♀ |

O (Ab) |

+ | NR | + | NR | Dc, VSD | - | PCD, CtD, NSt-LD | PC | PC Class 3 | |

| Abdallah, et al., 1993 [7] |

Case 15 ♂ |

O (Ab) |

NR (-) |

+ | + | + | TF, PDA | Type 1 | H, PCD | PC with TF | PC Class 1 |

| Fernández et al., 1997 [10] |

Case 21 C3, ♀ |

O (Ab) |

NR (+) |

+ | + | + | TF, RVD | Type 1 | CrfD | PC | PC Class 1 |

| Halbertsma et al., 2002 [19] |

Case 32 ♂ |

O (Ab) |

+ | NR | + | + | ASD, VSD, LVD | Type 1 | NR | PC with LVD and O | PC Class 2 |

| León et al., 2002 [20] |

Case 33 NR |

O (Ab) |

NR (+) |

NR | + | + | CHD | Type 1 | NR | PC | PC Class 2 |

| Davies and Duran, 2003 [21] |

Case 34 C1, NR |

O (Ab) |

+ | NR | + | NR | NR | Type 1 | AN, CP, NSt-LD | EC and O | PC Class 3 |

| Polat et al., 2005 [26] |

Case 45 C3, ♂ |

O (Ab) |

NR (+) |

+ | NR | NR | - | Type 2 | NR | PC | PC Class 3 BSA Type VIII STBWC IV |

| Marijon et al., 2006 [31] |

Case 51 ♂ |

O (Ab) |

NR (+) |

NR | + | NR | VSD, LVD | Type 1 | NR | PC | PC Class 3 |

| Meeker, 2009 [45] |

Case 65 ♂ |

Ab | NR (+) |

+ | + | + | Dc, PS, BAV | - | NR | PC | PC Class 1 BSA Type VIII STBWC IV |

| Suehiro et al., 2009 [46] |

Case 67 ♂ |

Ab | (+) | + | NR | NR | VSD, LVD, PDA | Type 2 | NR | PC | PC Class 3 BSA Type VIII STBWC IV |

| Brochut et al., 2011 [55] |

Case 97 ♂ |

O (Ab) |

Sc Short |

NR | NR | NR | VSD, TA | + | NR | PC | PC Class 3 |

| Case 98 ♀ |

Ab | Uc Short |

NR | NR | NR | NR | + | TRAPS | PC | EC | |

| Case 99 ♂ |

O (Ab) |

Uc Short SUA |

NR | NR | NR | NR | + | AA, IM | PC | EC | |

| Ranganath et al., 2012 [56] |

Case 108 ♀ |

O (Ab) |

NR (+) |

+ | + | + | TGA | Type 1 | Ee, ABS, St-SpD, NSt-LD | PC with Crch | PC Class 1 BSA Type VII SSBWC IV |

| Ito et al., 2013 [65] |

Case 112 ♂ |

O (Ab) |

NR (+) |

NR | + | NR | TGA, VSD, HRV | Type 1 | NR | PC | PC Class 3 |

| Meena and Meena, 2017 [78] |

Case 136 ♀ |

O (Ab) |

+ SUA |

+ | + | NR | NR | Type 1 | NR | PC with SUA | PC Class 3 |

| Madi et al., 2019 [86] |

Case 149 ♀ |

(Ab) | + Cyst |

+ | + | + | ASD, VSD | Type 1 | NR | EC associated with PC | PC Class 1 BSA Type VIII STBWC IV |

| Faisal et al., 2024 [98] |

Case 156 NR |

O (Ab) |

+ | NR | + | + | Mc, LVD, VSD | Type 1 | NR | PC with LVD | PC Class 2 |

| AUTHOR(S) | Case / Gender | BWD | UCD | StD | DD | PD | CD | ExEC | OD | AUTHOR’S DIAGNOSIS | PROPOSED DIAGNOSIS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Achiron, et al., 1991 [5] |

Case 14 ♀ |

SUThAb | NR (-) |

+ | NR | NR | VSD, TGA | Type 3 | NR | EC | PC Class 3 |

| Dembinski et al., 1997 [9] |

Case 18 ♀ |

SUThAb | - | + | + | + | ASD, PDA | Type 3 | CrfD, CH, St-SpD, St-LD, St-GuD | CSq | PC Class 1 |

| Fernández et al., 1997 [10] |

Case 19 C1, ♂ |

SUThAb | NR (-) |

+ | + | + | VSD, ASD, DORV | Type 3 | NSt-GuD | PC | PC Class 1 |

| Case 20 C2, ♀ |

SUThAb | NR | + | + | NR | DORV, ASD, VSD | - | L-SE, HT, GA, AA, St-GuD, NSt-SpD | PC | PC Class 2 | |

| Hsieh et al., 1998 [12] |

Case 23 C1, ♂ |

SUThAb | NR (-) |

+ | + | + | NS | Type 1 | CyH | PC with CyH | PC Class 3 |

| Pivnick et al., 1998 [15] |

Case 27 ♀ |

SUThAb | - | + | + | NR | NR | Type 3 | AOP(R), MOP(L), BCL, PCD, St-GuD, St-LD | Midline ThAb and LD | PC Class 3 |

| Nanda et al., 2003 [22] |

Case 39 NS |

O (SUThAb) |

NR (-) |

+ | NR | NR | VSD | Type 3 | NR | PC | PC Class 3 |

| Uygur et al., 2004 [24] |

Case 42 ♂ |

SUThAb | NR (-) |

+ | + | NR | ASD, PDA | Type 3 | GA, St-LD | PC and LD | PC Class 2 |

| Chen et al., 2008 [42] |

Case 55 ♀ |

SUThAb | - | + | + | + | VSD | Type 3 | Ee | PC with Ee and LD | PC Class 1 |

| Smigiel et al., 2011 [53] |

Case 101 ♀ |

O + DRM (SUThAb) |

NR (-) |

+ | + | - | - | Type 3 | AA, CrfD, NSt-LD, NSt-GuD | Goltz–Gorlin Syndrome and PC | PC Class 3 |

| Sakasai et al., 2012 [57] |

Case 109 ♂ |

O (SUThAb) |

NR (-) |

+ | + | + | VSD, PDA | Type 3 | NR | PC with EC and VSD | PC Class 1 |

| Chen et al., 2013 [62] |

Case 111 ♂ |

(SUThAb) | NR (-) |

+ | + | NR | NR | Type 3 | AN | CS with AN | EC |

| Kaouthar, et al., 2013 [67] |

Case 115 C2, ♀ |

SUThAb | NR (-) |

+ | NR | + | DORV, TGA | Type 3 | NR | PC | PC Class 2 |

| Puvabanditsin et al., 2013 [66] |

Case 117 ♂ |

(SUThAb) | NR (-) |

+ | + | + | DORV, TGA, PS, VSD | Type 3 | NR | EC | PC Class 1 |

| Restrepo et al., 2013 [70] |

Case 118 NS |

O (SUThAb) |

NR (-) |

+ | NR | + | ASD, TF, APVR | Type 3 | PCD, ABS | PC with EC, APVR and TF | PC Class 2 |

| Araujo et al., 2006 [28] |

Case 135 ♀ |

O (SUThAb) |

NR (-) |

+ | + | + | VSD | Type 3 | Hy | PC | PC Class 1 |

| Swarray-Deen et al., 2017 [82] |

Case 140 C2, ♀ |

(SUThAb) | NR (-) |

+ | + | + | NR | Type 3 | NR | PC | PC Class 3 |

| Delgado et al., 2019 [87] |

Case 145 NS |

O (SUThAb) |

NR (-) |

+ | + | + | PDA, LSVC to CS | Type 3 | NR | PC with total EC and a major O | PC Class 1 |

| Desikan et al., 2021 [91] |

Case 150 NS |

SUThAb | NR (-) |

+ | NR | NR | VSD | Type 3 | NR | Ec, NSt-LD | PC Class 3 |

| Shrestha, 2022 [92] |

Case 153 ♀ |

SUThAb | NR (-) |

+ | NR | + | NS | Type 3 | BCL, CP | EC, O, BCL and CP | PC Class 3 |

| Fabijan et al., 2024 [99] |

Case 160 ♀ |

O (SUThAb) |

NR (-) |

+ | NR | + | TF, APVR, LSVC to CS | Type 3 | HR | PC and EC | PC Class 2 |

| Garofalo et al., 2024 [100] |

Case 161 ♀ |

SUThAb | NR (-) |

NR | NR | NR | TGA, ASD, VSD, PS | + | Ep, OmT | Ep and ThAbEC | EC |

| Martadiansyah et at., 2025 [103] |

Case 164 C1, ♀ |

SUThAb | - | + | + | + | ASD, PDA | Type 3 | NR | EC complicated by PC | PC Class 1 |

| AUTHOR(S) | Case / Gender | BWD | UCD | StD | DD | PD | CD | ExEC | OD | AUTHOR’S DIAGNOSIS | PROPOSED DIAGNOSIS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zachariou et al., 1987 [3] |

Case 2 L.A., ♂ |

SUAb | - | NR | + | NR | VSD | - | PCD | PC | PC Class 3 |

| Milne et al., 1990 [4] |

Case 5 J.L.C., ♀ |

O (SUAb) |

NR (-) |

- | + | + | - | - | NR | PSDH with O | PC Class 3 |

| Case 6 N.K., ♀ |

O (SUAb) |

NR (-) |

- | + | + | Dc | - | NR | PSDH with O | PC Class 3 | |

| Case 7 A.J.T., NS |

O (SUAb) |

NR (-) |

+ | + | + | VSD | - | IM | PSDH with O | PC Class 1 | |

| Case 8 M.A, NS |

O (SUAb) |

NR (-) |

+ | + | + | BvD | - | NR | PSDH with O | PC Class 1 | |

| Case 9 B.G.H, NS |

O (SUAb) |

NR (-) |

+ | + | + | VSD, PS, DORV | - | NR | PSDH with O | PC Class 1 | |

| Case 10 H.E.P, NS |

O (SUAb) |

NR (-) |

+ | + | + | VSD, PTA type IV |

- | PCD | PSDH with O | PC Class 1 | |

| Case 11 A.M.S, NS |

O (SUAb) |

NR (-) |

+ | + | + | VSD, ASD, PAA | - | IM | PSDH with O | PC Class 1 | |

| Case 12 B.G.H, NS |

O (SUAb) |

NR (-) |

- | + | + | HLV, APVR | - | PCD, MD, CtD, St-GuD | PSDH with O | PC Class 2 | |

| Case 13 R.M., NS |

O (SUAb) |

NR (-) |

+ | + | + | - | Type 1 | PCD, IM, St-LD | PSDH with O | PC Class 3 | |

| Bogers et al., 1993 [8] |

Case 16 ♀ |

O + DRM (SUAb) |

NR (-) |

+ | + | + | VSD, BvD | Type 1 | CtD, SS | CS with BvD, VSD and EC | PC Class 1 |

| Katranci et al., 1998 [13] |

Case 24 C1, ♀ |

O (SUAb) |

NR (-) |

+ | + | + | TF | - | HCy | PC | PC Class 1 |

| Case 25 C2, ♂ |

O (SUAb) |

NR (-) |

+ | + | + | CHD | - | NSt-GuD | PC | PC Class 1 | |

| Vazquez-Jimenez et al., 1998 [11] |

Case 28 ♂ |

SUAb | NR (-) |

+ | + | NR | Dc, VSD, ASD, LVD, RVH |

- | NR | Partial PC | PC Class 2 |

| Falcao et al., 2000 [17] |

Case 29 ♂ |

SUAb | NR (-) |

+ | + | + | Mc, TF, VD, SCA | - | NR | PC | PC Class 1 |

| Song and McLeary, 2000 [16] |

Case 30 ♂ |

O (SUAb) |

NR (-) |

+ | - | - | Dc, CM, SV, PAA, TA | - | NR | PC with an intact diaphragm and pericardium | PC Class 3 |

| Alayunt et al., 2001 [18] |

Case 31 ♀ |

DRM, SUAb | NR (-) |

+ | + | + | Dc, VSD, LVD, TF, ASD | - | NR | LVD with PC and TF | PC Class 1 |

| Bittmann, et al., 2004 [23] |

Case 40 ♂ |

O (SUAb) |

NR (-) |

+ | + | + | HRV, VSD, ASD, PS | - | PCD, GA, Ps | PC with TF, GA and PS | PC Class 1 |

| Di Bernardo et al., 2004 [25] |

Case 41 NS |

SUAb | - | + | + | + | LVD, LSCV to CS | Type 3 | NR | PC with LVD | PC Class 1 |

| St. Louis, 2005 [29] |

Case 46 ♀ |

O (SUAb) |

NR (-) |

+ | + | + | HLHS | Type 3 | NR | PC with HLHS | PC Class 1 |

| Staboulidou et al., 2005 [27] |

Case 47 ♀ |

SUAb | NR (-) |

+ | + | + | NR | Type 3 | NR | PC | PC Class 2 |

| Araujo et al., 2006 [28] |

Case 48 NS |

O (SUAb) |

NR (-) |

+ | + | + | VSD | Type 3 | Hy | PC | PC Class 1 |

| Grethel et al., 2007 [32] |

Case 49 ♂ |

SUAb | - | + | + | + | Dc, LVA, ASD | - | NSt-GuD | PC and LVA | PC Class 1 |

| Loureiro et al., 2007 [34] |

Case 52 NS |

SUAb | NR (-) |

+ | + | NR | PTA, VSD | Type 3 | Ecc, Myc, H | PC with ONTD, St-SpD, NSt-LD |

PC Class 2 |

| Wheeler, & St. Louis, 2007 [33] |

Case 53 ♀ |

SUAb | NR (-) |

+ | + | + | HLHS | Type 3 | NR | PC with HLHS | PC Class 1 |

| Hou et al., 2008 [39] |

Case 56 ♂ |

SUAb | NR (-) |

+ | + | NR | Dc, PDA, AVC, VSD, BvH, RVD | Type 3 | CrfD, L-SE, CH, St-SpD, NSt-LD, NSt-GuD | Incomplete PC |

PC Class 2 |

| Korver et al., 2008 [35] |

Case 57 ♂ |

SUAb | - | + | + | NR | Dc, VSD, LVD | Type 3 | NR | PC | PC Class 2 |

| Okamoto et al., 2008 [37] |

Case 59 ♀ |

SUAb | NR (-) |

+ | NR | NR | TA | Type 3 | H | PC with severe EC | PC Class 3 |

| Turbendian et al., 2008 [40] |

Case 60 ♀ |

O (SUAb) |

NR (-) |

- | + | + | LVD | + | NR | PC | PC Class 2 |

| Zidere and Allan, 2008 [41] |

Case 61 C1, NS |

O (SUAb) |

NR (-) |

+ | + | + | DORV | - | IM, NSt-GuD |

PC | PC Class 1 |

| Case 62 C2, NS |

O (SUAb) |

NR (-) |

+ | + | + | ASD | - | PCD | PC | PC Class 1 | |

| Case 63 C3, NS |

O (SUAb) |

NR (-) |

+ | + | + | VSD, ASD | - | PCD | PC | PC Class 1 | |

| Balderrábano-Saucedo et al., 2011 [52] |

Case 70 C3, NS |

O (SUAb) |

NR (-) |

+ | + | + | LVD, VSD | Type 3 | NR | PC with EC | PC Class 1 |

| Case 71 C4, NS |

O (SUAb) |

NR (-) |

+ | + | + | DORV, PTA, PS, PDA, SCA | Type 3 | NR | PC with EC | PC Class 1 | |

| Case 73 C6, NS |

O (SUAb) |

NR (-) |

+ | + | + | SA, SV, AVC, TGA, PS, PDA | Type 3 | NR | PC with EC | PC Class 1 | |

| Case 76 C9, NS |

O (SUAb) |

NR (-) |

+ | + | + | DORV, PS | Type 3 | NR | PC with EC | PC Class 1 | |

| Case 78 C11, NS |

O (SUAb) |

NR (-) |

+ | + | + | SV, PTA | Type 3 | NR | PC with EC | PC Class 1 | |

| Case 80 C13, NS |

O (SUAb) |

NR (-) |

+ | + | + | DORV | Type 3 | NR | PC with EC | PC Class 1 | |

| Case 81 C14, NS |

O (SUAb) |

NR (-) |

+ | + | + | BVD, TF | - | NR | PC without EC | PC Class 1 | |

| Case 84 C16, NS |

O (SUAb) |

NR (-) |

+ | + | + | DILV, PS | - | NR | PC without EC | PC Class 1 | |

| Case 85 C17, NS |

O (SUAb) |

NR (-) |

+ | + | + | DILV, ASD, PS, PDA | - | NR | PC without EC | PC Class 1 | |

| Case 86 C18, NS |

O (SUAb) |

NR (-) |

+ | + | + | VSD, ASD, PDA | - | NR | PC without EC | PC Class 1 | |

| Case 87 C20, NS |

O (SUAb) |

NR (-) |

+ | + | + | LVD, DORV, PS | - | NR | PC without EC | PC Class 1 | |

| Case 88 C21, NS |

O (SUAb) |

NR (-) |

+ | + | + | VSD | - | NR | PC without EC | PC Class 1 | |

| Herman and Siegel, 2010 [48] |

Case 90 ♀ |

O (SUAb) |

NR (-) |

NR | + | + | ASD, VSD, PDA | - | NR | PC | PC Class 2 |

| Brochut et al., 2011 [55] |

Case 100 ♂ |

O (SUAb) |

- | + | + | + | Dc, APVR | Type 3 | NR | PC | PC Class 1 |

| Wen et al., 2011 [54] |

Case 102 ♂ |

O (SUAb) |

NR (-) |

+ | + | AVC, ASD, VSD, TGA, PS | Type 3 | NR | PC with complex cardiac malformations | PC Class 2 | |

| Ergenoğlu et al., 2012 [58] |

Case 103 ♂ |

O (SUAb) |

- | NR | NR | NR | NR | + | St-SpD, St-LD | PC | EC |

| Kinoshita, et al., 2012 [59] |

Case 107 C3, ♂ |

O (SUAb) |

NR (-) |

+ | + | + | ASD | - | NR | PC | PC Class 1 |

| Pirasteh et al., 2014 [72] |

Case 121 ♀ |

O (SUAb) |

NR (-) |

NR | + | + | LVD, DORV, VSD, PAH, TGA, HRV | + | NR | PC with EC | PC Class 2 |

| Naburi et al., 2015 [73] |

Case 130 ♀ |

SUAb | NR (-) |

+ | + | NR | VSD, ASD | Type 3 | NR | PC Class 2 | PC Class 2 |

| Türkçapar et al., 2015 [75] |

Case 132 NS |

O (SUAb) |

NR (-) |

NR | + | NR | NR | + | CyH, St-SpD | PC | EC |

| Madžarac et al, 2016 [76] |

Case 133 ♂ |

SUAb | NR (-) |

+ | + | + | VSD | Type 3 | HD, NSt-GuD | PC with unilateral kidney evisceration | PC Class 1 |

| Yang et al., 2016 [77] |

Case 134 ♀ |

O (SUAb) |

NR (-) |

+ | + | + | VSD, ASD, LVD | Type 3 | NR | PC | PC Class 1 |

| Swarray-Deen et al., 2017 [82] |

Case 139 C1, ♀ |

O (SUAb) |

NR (-) |

NR | + | + | VSD, TF | Type 3 | NSt-LD | PC | PC Class 2 |

| Zani-Ruttenstock, et al., 2017 [79] |

Case 141 ♀ |

O + DRM (SUAb) |

NR (-) |

+ | + | NR | VSD, ASD, APVR, PDA, LVD | Type 3 | NR | PC | PC Class 2 |

| Grigore et al., 2018 [84] |

Case 142 NS |

SUAb | NR (-) |

NR | + | + | NS | + | UAOP, CrfD | PC with UAOP | PC Class 3 |

| Kylat, 2019 [88] |

Case 147 C1, ♀ |

O (SUAb) |

- | + | + | + | VSD, PDA, PS | Type 3 | NR | PC | PC Class 1 |

| Zvizdic et al., 2021 [90] |

Case 151 ♂ |

O (SUAb) |

NR (-) |

+ | + | + | ASD, VSD | Type 3 | NR | PC | PC Class 1 |

| Fazea et al., 2022 [94] |

Case 152 ♂ |

O (SUAb) |

NR (-) |

+ | + | NR | CHD | Type 3 | SpD | PC with EC | PC Class 2 |

| Mraihi et al., 2023 [97] |

Case 159 C2, NS |

O (SUAb) |

NR (-) |

NR | + | NR | NR | + | NR | PC | EC |

| Dusuri et al., 2025 [101] |

Case 162 ♂ |

O (SUAb) |

NR (-) |

+ | + | NR | NS | Type 3 | AH, St-SpD, NSt-LD |

Complete PC with EC and multiple anomalies |

PC Class 3 |

| Maheshwari & Sahoo, 2025 [102] |

Case 163 ♂ |

O + DRM (SUAb) |

NR (-) |

+ | + | NR | TF | Type 3 | NR | PC with TF and Absent Diaphragm | PC Class 2 |

| AUTHOR(S) | Case / Gender | BWD | UCD | StD | DD | PD | CD | ExEC | OD | AUTHOR’S DIAGNOSIS | PROPOSED DIAGNOSIS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fernández et al., 1997 [10] |

Case 22 C4, ♀ |

VEH (SUICD) |

- | + | NR | + | VSD, ASD, AVS, PDA | - | Hy, L-SE, CP, St-GuD, NSt-SpD |

PC | PC Class 2 |

| Knirsch et al., 2006 [30] |

Case 50 NS |

(SUICD) | - | + | NR | NR | VSD, ASD, URC, LVD | Type 3 | NR | PC | PC Class 3 |

| Gao et al., 2009 [43] |

Case 64 ♀ |

(SUICD) | NR (-) |

+ | + | + | PTA, VSD, ASD, PDA | Type 3 | NR | PC with ThAbEC | PC Class 1 |

| Mitsukawa et al., 2009 [44] |

Case 66 ♀ |

(SUICD) | - | NR | + | + | VSD, ASD | + | NR | PC | PC Class 2 |

| Balderrábano-Saucedo et al., 2011 [52] |

Case 72 C5, NS |

RD (SUICD) |

NR (-) |

+ | + | + | CoA, VSD | Type 3 | NR | PC with EC | PC Class 1 |

| Case 74 C7, NS |

RD (SUICD) |

NR (-) |

+ | + | + | SV, LSVC to CS |

Type 3 | NR | PC with EC | PC Class 1 | |

| Case 75 C8, NS |

RD (SUICD) |

NR (-) |

+ | + | + | LVD, ASD | Type 3 | NR | PC with EC | PC Class 1 | |

| Case 77 C10, NS |

RD (SUICD) |

NR (-) |

+ | + | + | DORV, SCA | Type 3 | NR | PC with EC | PC Class 1 | |

| Case 79 C12, NS |

RD (SUICD) |

NR (-) |

+ | + | + | LVD, VSD | Type 3 | NR | PC with EC | PC Class 1 | |

| Case 83 C15, NS |

RD (SUICD) |

NR (-) |

+ | + | + | HRVS, PTA, VSD, LSVC to CS | - | NR | PC without EC | PC Class 1 | |

| Singh et al., 2010 [49] |

Case 92 ♀ |

RD (SUICD) |

NR (-) |

+ | + | + | Mc, DORV, VSD, LVD |

Type 3 | NR | PC | PC Class 1 |

| Sowande et al., 2010 [47] |

Case 93 C1, ♀ |

(SUICD) | - | + | NR | NR | NS | Type 3 | NR | PC | PC Class 3 |

| Case 94 C2, ♀ |

(SUICD) | - | + | NR | NR | Mc, GH | Type 3 | NR | PC | PC Class 3 | |

| Case 95 C3, ♂ |

(SUICD) | - | + | NR | NR | Mc, GH | Type 3 | NR | PC | PC Class 3 | |

| Kinoshita, et al., 2012 [59] |

Case 106 C2, ♀ |

RD (SUICD) |

NR (-) |

+ | + | DORV, PAA, VSD, PDA | Type 3 | NR | PC Class 2 | ||

| Magadum et al., 2013 [63] |

Case 116 ♂ |

(SUICD) | + | + | + | NR | Type 3 | HD | Incomplete PC | PC Class 3 | |

| Zhang et al., 2014 [71] |

Case 122 C1, ♀ |

(SUICD) | NR (-) |

+ | + | NR | DORV, VSD, LSVC | Type 3 | NR | PC | PC Class 2 |

| Case 123 C2, ♂ |

(SUICD) | NR (-) |

+ | + | NR | VSD, LSVC | Type 3 | CL | PC | PC Class 2 | |

| Case 124 C3, ♀ |

(SUICD) | NR (-) |

+ | + | NR | ASD | - | NR | PC | PC Class 2 | |

| Case 125 C4, ♂ |

(SUICD) | NR (-) |

+ | + | NR | VSD | Type 3 | NR | PC | PC Class 2 | |

| Case 126 C5, ♂ |

(SUICD) | NR (-) |

+ | + | NR | DORV, VSD, ASD, PS, LSVC | Type 3 | NR | PC | PC Class 2 | |

| Case 127 C6, ♂ |

(SUICD) | NR (-) |

+ | + | NR | VSD, ASD, LSVC | - | PCD | PC | PC Class 2 | |

| Case 128 C7, ♂ |

(SUICD) | NR (-) |

+ | + | NR | VSD, ASD, LSVC | - | NR | PC | PC Class 2 | |

| Case 129 C8, ♂ |

(SUICD) | NR (-) |

+ | + | NR | VSD, ASD, LVD, LSVC | Type 3 | CL | PC | PC Class 2 | |

| Salinas-Torres et al., 2017 [81] |

Case 138 ♂ |

(SUICD) | - | + | + | + | HLV | Type 3 | CrfD, ABS | PC with severe amputations | PC Class 1 |

| Màrginean et al., 2018 [83] |

Case 144 ♂ |

RD (SUICD) |

NR (-) |

NR | NR | NR | TA, VDS, PAH | + | NR | PC | EC |

| Wang et al., 2022 [95] |

Case 155 ♂ |

RD (SUICD) |

NR (-) |

+ | + | + | LVD, ASD, VSD, PDA | + | NR | PC | PC Class 1 |

| Liao et al., 2023 [96] |

Case 157 ♂ |

RD (SUICD) |

- | + | - | + | VSD, ASD, CoA, PDA, PLSVC | Type 3 | NR | PC | PC Class 2 |

| AUTHOR(S) | Case / Gender | BWD | UCD | StD | DD | PD | CD | ExEC | OD | AUTHOR’S DIAGNOSIS | PROPOSED DIAGNOSIS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Laloyaux et al., 1998 [14] |

Case 26 ♂ |

UH, RD | NR (-) |

+ | + | + | VSD, ASD, TA, PS | Type 3 | NR | PC | PC Class 1 |

| Marcí et al., 2008 [38] |

Case 58 ♂ |

UH | NR (-) |

NR | + | NR | LVD, DORV | + | NR | PC with DORV | PC Class 3 |

| Balderrábano-Saucedo et al., 2011 [52] |

Case 68 C1, NS |

UH | NR (-) |

+ | + | + | SA, SV, AvC, PS | Type 3 | NR | PC with EC | PC Class 1 |

| Case 69 C2, NS |

UH | NR (-) |

+ | + | + | LVD, VSD, PDA, SCA | Type 3 | NR | PC with EC | PC Class 1 | |

| Case 82 NS |

UH | NR (-) |

+ | + | + | LVD, DORV | - | NR | PC without EC | PC Class 1 | |

| Case 89 C22, NS |

UH | NR (-) |

+ | + | + | LVD, DORV | - | NR | PC without EC | PC Class 1 | |

| Quandt et al., 2010 [50] |

Case 91 ♀ |

UH RD |

NR (-) |

NR | NR | NR | SS, ASD, LVD | + | NR | PC | PC Class 3 |

| El Kouache et al., 2012 [60] |

Case 104 ♀ |

UH | NR (-) |

+ | + | + | Dc, LVD, triatrial SS VSD, ASD, PDA | Type 3 | NR | LVD with partial PC | PC Class 1 |

| Kaouthar, et al., 2013 [67] |

Case 114 C1, ♀ |

UH, RD | NR (-) |

+ | + | NR | Dc, DORV, TGA, LSVC to CS | Type 3 | SS | PC | PC Class 2 |

| Kylat, 2019 [88] |

Case 148 C2, ♂ |

UH | - | + | NR | NR | ASD, LSVC to CS | Type 3 | NR | Incomplete PC | PC Class 3 |

| AUTHOR(S) | Case / Gender | BWD | UCD | StD | DD | PD | CD | ExEC | OD | AUTHOR’S DIAGNOSIS | PROPOSED DIAGNOSIS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Davies and Duran, 2003 [21] |

Case 35 C2, NS |

ThG | - | + | NR | NR | NR | Type 4 | NR | EC and ThG | PC Class 3 |

| Case 36 C3, NS |

ThG | - | + | NR | NR | NR | Type 4 | NR | EC and ThG | PC Class 3 | |

| Nanda et al., 2003 [22] |

Case 38 C1, ♀ |

LThAb | (-) | + | + | + | VSD | Type 1 | St-SpD, NSt-LD | PC | PC Class 1 |

| Polat et al., 2005 [26] |

Case 43 C1, ♀ |

O (LThAb) |

NR (-) |

+ | NR | NR | - | Type 3 | Ee, Hy, St-SpD, NSt-LD | PC | PC Class 3 |

| Case 44 C2, ♀ |

O (LAb/G) |

NR (-) |

NR | NR | NR | - | + | Ee, Hy, St-SpD, NSt-LD | PC | EC | |

| Chelli et al., 2008 [36] |

Case 54 ♀ |

ThAb (LAb/G) |

- | NR | NR | NR | NR | + | Ht, CrfD, NSt-LD | EC | EC |

| Kinoshita, et al., 2012 [59] |

Case 105 C1, ♂ |

O + RD (LAb/G) |

NR (-) |

+ | + | + | NR | Type 4 | NR | PC | PC Class 3 |

| Chandran and Ari, 2013 [61] |

Case 110 ♂ |

O (LThAb) |

(-) | + | + | + | ASD, VSD, PDA | Type 1 | BCL | PC | PC Class 1 |

| Timur et al., 2015 [74] |

Case 131 ♂ |

O (LAb/G) |

NR (-) |

+ | + | NR | VSD | - | NR | PC | PC Class 2 |

| AUTHOR(S) | Case / Gender | BWD | UCD | StD | DD | PD | CD | ExEC | OD | AUTHOR’S DIAGNOSIS | PROPOSED DIAGNOSIS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Angoulvant et al., 2011 [51] |

Case 96 ♂ |

- | - | NR | + | + | ASD, APVR | - | NR | Incomplete PC | CHD |

| Hubbard et al., 2018 [85] |

Case 143 ♀ |

- | - | + | NR | NR | VSD, SCA, ASD | + | Ecc, CrfD, CP | PC | EC |

| Martadiansyah et at., 2025 [103] |

Case 165 C2, ♀ |

UICD | + | + | + | + | ASD, TF, PDA | Type 2 | NR | EC complicated by PC | PC Class 1 BSA Type VIII STBWC IV |

| AUTHOR(S) | Case / Species/ Gender |

BWD | UCD | StD | DD | PD | CD | ExEC | OD | AUTHOR’S DIAGNOSIS | PROPOSED DIAGNOSIS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Butler, 1960 [127] |

Case 1 D, ♂ |

UH | NR (-) |

NR | + | NR | NR | + | NR | CDH an UH | PC Class 3 |

| Bellah et al., 1989 [128] |

Case 2 D, C1, ♀ |

(SUICD) | NR (-) |

+ | + | + | VSD | Type 3 | NR | CAWD, StD, DD, PD and CD | PC Class1 |

| Case 3 D, C2, ♀ |

(SUICD) | NR (-) |

+ | + | + | VSD | Type 3 | NR | CAWD, StD, DD, PD and CD | PC Class1 | |

| Case 4 D, C3, ♂ |

(SUICD) | NR (-) |

+ | + | + | VSD | Type 3 | NR | CAWD, StD, DD, PD and CD | PC Class1 | |

| Case 5 D, C4, ♂ |

(SUICD) | NR (-) |

+ | + | + | - | Type 3 | NR | CAWD, StD, DD and PD | PC Class 3 | |

| Case 6 D, C5, ♂ |

(SUICD) | NR (-) |

+ | + | + | - | Type 3 | NR | CAWD, StD, DD and PD | PC Class 3 | |

| Benllock-González and Poncet, 2015 [129] |

Case 7 D, ♂ |

UH | NR (-) |

+ | + | + | PDA, PLCVC | Type 3 | NR | Sternal cleft associated with PC | PC Class1 |

| Khan et al., 2019 [130] |

Case 8 D, ♂ |

UH | NR (-) |

+ | + | + | NR | - | NR | PPDH | PC Class 3 |

| Williams et al., 2020 [131] |

Case 9 D, ♂ |

DRM (SUICD) |

NR (-) |

+ | + | + | NR | Type 3 | NR | Incomplete PC | PC Class 3 |

| Hennink et al., 2021 [132] |

Case 10 D, ♂ |

UH | NR (-) |

+ | + | + | NR | - | Pericardial pseudocyst | Unusual PPDH associated with a pericardial pseudocyst | PC Class 3 |

| So et al., 2023 [108] |

Case 11 D, C1, ♂ |

ThAb | NR (+) |

+ | + | + | NS | Type 1 | St-LD, | PC | PC Class 3 BSA TYPE V STLBWC III |

| Case 12 D, C2, ♂ |

Ab | NR (+) |

+ | + | NR | NS | - | NR | PC | PC Class 3 BSA TYPE VIII STBWC IV |

|

| Ozdemir-Salci and Yildirim 2024 [133] |

Case 13 D, ♂ |

ThAb | NR (+) |

+ | - | - | - | Type 2 | NR | Thoracic EC, sternal agenesis, partial ectopia hepática and fissure abdominalis | BSA TYPE VI STBWC III |

| Cózar et al., 2025 [104] |

Case 14 D, ♀ |

ThAb | + | + | + | + | MVS, ASD, HLV, TVD | Type 1 | BCh, PP, ABS | PC Class 1 BSA TYPE VI STBWC III ABS |

PC Class 1 BSA TYPE VI STBWC III |

| Case 15 D, ♂ |

ThAb | + | + | + | + | GH, VSD, RVH | Type 1 | SP, St-SpD, NSt-GuD |

BSA TYPE V SSBWC III PC Class 1 |

PC Class 1 BSA TYPE V SSBWC III |

|

| Case 16 D, ♂ |

LThAb | - | + | + | - | RVH | Type 4 | NSt-SpD, NSt-GuD | PC Class 2 | PC Class 2 | |

| López et al., 2015 [134] |

Case 17 Ct, ♂ |

- | NR (-) |

NR | + | + | Dc | + | HF | Cardiac malposition (EC) | EC |

| Eiger et al., 2019 [135] |

Case 18 Ct, ♀ |

UH | NR (-) |

+ | + | + | NR | Type 3 | NR | StD with PC | PC Class 3 |

| Kokkinos and Pratschke, 2022 [136] |

Case 19 Ct, ♀ |

(SUICD) | NR (-) |

+ | + | + | AVS, BAV, DA | Type 3 | Ect, SL, BG, IDBK | PC with Ect | PC Class 1 |

| AUTHOR(S) | Case / Species/ Gender |

BWD | UCD | StD | DD | PD | CD | ExEC | OD | AUTHOR’S DIAGNOSIS | PROPOSED DIAGNOSIS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Martín-Alguacil and Avedillo, 2020 [105] |

Case 20 C1, ♂ |

(ThAb) | + Short ACP DUV HUA |

+ | + | + | ASD | Type 1 | EcC | Cantrell Syndrome | PC Class 1 BSA Type VI STBWC III |

| Case 21 C2, ♀ |

(ThAb) | + Short ACP DUV |

+ | + | + | VSD, GH | Type 1 | EcL | Cantrell Syndrome | PC Class 1 BSA Type VI STBWC III |

|

| Case 22 C3, ♂ |

(ThAb) | + Short ACP DUV HUA |

+ | + | + | VSD, GH | Type 1 | NR | Cantrell Syndrome | PC Class 1 BSA Type VI STBWC III |

|

| Case 23 C4, ♂ |

(ThAb) | + Short ACP DUV SUA |

+ | + | + | ASD, AMV, SCA | Type 1 | LAM | Cantrell Syndrome | PC Class 1 BSA Type VI STBWC III |

|

| Case 24 C5, ♀ |

(ThAb) | + Short ACP DUV |

+ | + | + | HAs, TGA, VSD | Type 1 | NR | Cantrell Syndrome | PC Class 1 BSA Type VI STBWC III |

|

| Case 25 C6, ♀ |

(ThAb) | + Short ACP DUV |

+ | + | + | ASD | Type 1 | NR | Cantrell Syndrome | PC Class 1 BSA Type VI STBWC III |

| AUTHOR(S) | Case / Species/ Gender |

BWD | UCD | StD | DD | PD | CD | ExEC | OD | AUTHOR’S DIAGNOSIS | PROPOSED DIAGNOSIS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hiraga and Abe, 1986 [137] |

Case 26 Cf, C1, ♀ |

- | NR (-) |

+ | NR | (+) | DbA, CVCD | + | AADT, NSt-SpD | Cervical EC | EC |

| Case 27 Cf, C2, ♀ |

- | NR (-) |

+ | NR | (+) | DbA, CVCD | + | AADT, CP | Cervical EC | EC | |

| Case 28 Cf, C3, ♂ |

- | NR (-) |

+ | NR | (+) | DbA, CVCD, VAD | + | AADT, NSt-SpD | Cervical EC | EC | |

| Case 29 Cf, C4, ♂ |

- | NR (-) |

+ | NR | (+) | DbA, CVCD, PDA | + | AADT | Cervical EC | EC | |

| Case 30 Cf, C5, ♀ |

- | NR (-) |

+ | NR | (+) | DbA, VAD, SCA | + | AADT, NSt-SpD | Cervical EC | EC | |

| Case 31 Cf, C6, ♀ |

- | NR (-) |

+ | + | (+) | DbA, CVCD, SCA | + | AADT, NSt-SpD, CP | Cervical EC | EC | |

| Case 32 Cf, C7, ♂ |

- | NR (-) |

+ | NR | (+) | DbA, CVCD, VAD | + | AADT, NSt-SpD, CSt | Cervical EC | EC | |

| Case 33 Cf, C8, ♂ |

- | NR (-) |

+ | NR | (+) | DbA, CVCD | + | AADT, NSt-SpD | Cervical EC | EC | |

| Windberger et al., 1992 [138] |

Case 34 Cf, ♂ |

- | NR (-) |

+ | NR | NR | CVCD, SPV | + | Chromosomal aberrations | Cervical EC | EC |

| Hiraga et al., 1993 [137] |

Case 35 Cf, C1, ♂ |

- | NR (-) |

+ | NR | + | GH, DbA, CVCD, VAD, SPV | + | St-SpD, NSt-GuD, CP | Cervico-pectoral EC | EC |

| Case 36 Cf, C2, ♀ |

- | NR (-) |

+ | NR | + | GEH, SPV, RAV | + | NSt-SpD, NSt-GuD, CP | Cervico-pectoral EC | EC | |

| Erösüz et al., 1998 [139] |

Case 37 Cf, ♀ |

- | NR (-) |

+ | NR | + | APVR | + | HF, LAM, FK, HHS | Total pectoral EC and and other congenital malformations |

EC |

| Floeck et al. 2008 [140] |

Case 38 Cf, ♀ |

UH | NR (-) |

NR | + | + | ASD, VSD, DORV, PDA | + | SIL | PC with Taussig-Bing syndrome and SIL | PC Class 2 |

| Onda et al., 2011 [141] |

Case 39 Cf, ♀ |

- | NR (-) |

+ | NR | NR | CHt, DTV | + | NR | Cervical EC | EC |

| Cerqueira et al., 2024 [142] |

Case 40 Lm, C1, ♂ |

- | NR (-) |

+ | NR | + | NR | + | NR | Complete Thoracic EC | EC |

| Case 41 Lm, C2, ♂ |

- | NR (-) |

+ | NR | + | NR | + | CtD | Complete Thoracic EC | EC |

| Defect | Embryologic Origin | Timing (Human) | Timing (Dog) | Characteristic features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Omphalocele | Failure of midgut return after physiologic herniation | Weeks 6-10 | ~ Days 30-35 | Sac-covered herniation at umbilicus |

| Supraumbilical defect | Failure of lateral plate mesoderm fusion at ventral midline | Days 14-18 | Days 14-35 | Multisystem anomalies (sternum, diaphragm, pericardium, abdominal wall) |

| Sternal defect | Incomplete fusion of paired sternal bars (somatic mesoderm) | Days 14-18 | Days 14-35 | Sternal cleft or agenesis |

| Diaphragmatic defect | Abnormal septum transversum and pleuroperitoneal membrane incorporation | Days 14-18 | Days 14-35 | Ventral diaphragmatic gaps, often with Cantrell’ spectrum |

| Gastroschisis | Localized disruption of lateral body wall folding | Weeks 4-6 | ~ Days 30-35 | Paraumbilical opening, no sac, isolated defect |

| Rectus diastasis | Incomplete fusion of linea alba (lateral plate mesoderm) | Days 14-18 | Days 14-35 | Separation of rectus muscles, no true wall defect |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).