1. Introduction

Complex body wall anomalies represent a rare but diagnostically significant group of congenital malformations in veterinary medicine. Among these, Cantrell Syndrome (CS), Body Stalk Anomaly (BSA), and Amniotic Band Syndrome (ABS) stand out due to their severity, overlapping phenotypic features, and distinct embryological origins. Although extensively studied in human medicine, their occurrence in dogs remains poorly documented, often leading to diagnostic ambiguity and limited therapeutic options.

CS, also known as Pentalogy of Cantrell (PC), is characterized by five midline defects involving the diaphragm, abdominal wall, pericardium, heart, and lower sternum [

1]. In animals, CS presents as thoracoabdominoschisis (ThAb) without spinal or limb anomalies [

2]. A hallmark feature is

Ectopia cordis (EC), where the heart is located outside the thoracic cavity. EC is classified into five types—cervical, cervicothoracic, thoracic, thoracoabdominal, and abdominal—with thoracoabdominal EC most commonly associated with PC [

3]. Cases of EC have been reported in cattle [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9], cats [

10], sheep [

11], pigs [

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19], and dogs [

20,

21], though pure EC remains extremely rare and poorly understood. The pathogenesis is thought to involve defective cranial folding or impaired development of the ventral mesoderm during early gestation [

1], with multifactorial etiology still under investigation [

22]. EC cases may exhibit a variety of anatomical variations, including diaphragmatic disruptions, sternocostal defects, and abdominal wall anomalies such as omphalocele, abdominoschisis (Ab), and gastroschisis [

23]. The position and morphology of the umbilical cord (UC) can also vary considerably, ranging from normal insertion to complete absence or displacement. This diversity raises important questions about classification and syndromic associations. One of the aims of this study is to explore whether all of these anatomical presentations should be considered part of PC or if certain combinations, such as those involving gastroschisis or a reversed diaphragmatic hernia without sternal involvement, fall outside of its scope.

BSA is another severe congenital defect involving failure of ventral body wall closure, skeletal abnormalities, and an anomalous or absent UC. When accompanied by limb anomalies, it is classified as Limb Body Wall Complex (LBWC) [

24]. BSA is believed to result from early disruptions in embryonic folding and mesodermal fusion [

25]. Though well-characterized in humans, veterinary reports—particularly in dogs and cats—are limited [

26,

27]. The classification system originally developed in porcine models [

25] has since been successfully applied to canine and feline cases, offering a framework to distinguish between Ab and ThAb, and between structural and nonstructural skeletal anomalies [

28].

ABS differs from CS and BSA in its extrinsic origin. It arises from fibrous strands formed by rupture of the amnion, which entangle and constrict fetal structures, leading to a wide range of anomalies [

29]. These can include limb amputations, craniofacial defects, and body wall abnormalities, depending on the timing and location of entrapment [

30]. ABS is typically sporadic and not genetically inherited [

31]. In dogs, ABS has been associated with asymmetrical malformations and thoracoabdominal defects [

26]. The critical developmental window for amniotic band (AB) formation corresponds to days 10–20 of gestation in dogs and cats [

32,

33]. ABS is often diagnosed based on characteristic anomalies even in the absence of visible bands, and must be differentiated from amniotic sheets, which do not attach to fetal structures and are not associated with malformations [

29].

Terminological ambiguity persists in the literature, with various labels used to describe these anomalies, including ABS, AB sequence [

26,

27], AB disruption complex [

24], LBWC [

34,

35,

36], and ADAM sequence [

37]. ABS broadly refers to congenital anomalies caused by fibrous bands from a ruptured amnion, most commonly limb amputations and constriction rings [

38]. The term AB sequence, however, emphasizes the cascade of developmental disruptions initiated by amnion rupture [

39]. Both ABS and AB sequence fall under the umbrella of the Amniotic Disruption Complex (ADC), whose etiology remains debated. The extrinsic theory, proposed by Torpin (1965) [

40], suggests that early amnion rupture leads to oligohydramnios and fetal entanglement with the chorionic surface, resulting in disruption defects [

41]. These fibrous strands can immobilize or amputate fetal parts, with early insults affecting craniofacial and neural development, and later ones primarily impacting limbs [

34]. Alternatively, the intrinsic theory attributes ABS to vascular endothelial injury, which leads to the formation of constriction bands and secondary amputations [

42].

Together, CS, BSA, and ABS form a spectrum of complex body wall anomalies with distinct pathogenic mechanisms—mesodermal failure, embryonic folding disruption, and mechanical entrapment, respectively. This study aims to elucidate the similarities and differences among these three syndromes in dogs, focusing on their embryological origins, anatomical manifestations, and potential etiological factors. By comparing clinical cases and reviewing developmental pathways, we seek to improve recognition of these conditions in veterinary practice and contribute to a more precise classification of congenital malformations in canine species.

2. Materials and Methods

This study involved an anatomical and imaging-based examination of three canine cadavers exhibiting ventral body wall closure defects and enteroceles (EC). These cases were collected between 2020 and 2025. The characteristics of the specimens are summarized in

Table 1. They were obtained in accordance with European Union Directive 2010/63/EEC and Spanish legislation RD 53/2013. The research was conducted by the GIMCAD 971005-UCM group at the Universidad Complutense de Madrid, which is dedicated to investigating congenital malformations in domestic animals.

Each specimen underwent a detailed gross anatomical evaluation using standard dissection techniques, complemented by advanced imaging modalities, including computed tomography (CT), three-dimensional reconstructions and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), to further characterize the anomalies. Due to differences in the availability of equipment at the time of specimen collection, CT was performed using three distinct systems. One specimen (Case 1) was scanned using the MultiVET multimodality system, which is equipped with a 32 kW X-ray generator and a 100 µm high-resolution flat panel detector. This system was manufactured by SEDECAL (Spanish Society of Electromedicine and Quality, S.A.) in Algete, Madrid, Spain. Another dog (Case 2) was imaged using the Albira ARS II system (Bruker, Germany) at the Bioimagen Complutense (BIOMAC) Singular Scientific and Technical Facility (ICTS), with acquisition parameters of 600 mA and 45 kV to achieve a spatial resolution of 150 µm. The remaining specimen (Case 3) was scanned using a Toshiba Aquilion 64 multislice CT scanner with settings of 350 mA and 120 kV, a matrix of 512 × 512, and a field of view of 5.5 cm. Images from this system were acquired using a bone reconstruction algorithm (window level 550, window width 2550) with a slice thickness of 0.5 mm and a pitch of 0.4 mm. Despite the differences in equipment, all imaging procedures were standardized to ensure consistency in image quality and resolution across the dataset. The MRI study was performed at the ICTS BIOMAC. A 1-Tesla benchtop MRI scanner [Icon (1T-MRI); Bruker BioSpin GmbH, Ettlingen, Germany] was utilized. The system comprises a 1-Tesla permanent magnet with a gradient coil providing a gradient strength of 450 mT/m. A solenoidal radiofrequency (RF) coil was used for signal reception.

2.1. Case Classification Criteria for BSA

Following diagnostic criteria established by Martín-Alguacil and colleagues in porcine and human models [

24,

25,

43], the cases were classified under BSA. This classification system was originally developed for pigs and distinguishes eight types of BSA. Type I includes ThAb, an anomalous UC, anal atresia, urogenital anomalies and structural defects in the limbs and spine. Type II includes similar features, but with spinal anomalies only. Type III involves Ab with limb and spinal anomalies. Type IV includes Ab with spinal anomalies alone. Types V and VI involve ThAb with sternal and/or spinal anomalies. Types VII and VIII involve Ab with sternal and spinal anomalies, or spinal anomalies alone. Additionally, the study applied complementary classifications to describe the relationship between body wall defects and specific skeletal anomalies: These were: Spinal Body Wall Complex (SPBWC) for cases involving spinal anomalies; Spinal Limb Body Wall Complex (SPLBWC) for cases involving both spinal and limb anomalies; Sternal Body Wall Complex (STBWC) for cases with sternal anomalies; and Sternal Spinal Body Wall Complex (SSBWC) for cases involving both sternal and spinal structural anomalies [

43].

2.2. Case Classification Criteria for CS

CS is classified into three categories based on the presence and combination of five characteristic anomalies: a midline supraumbilical abdominal wall defect; a lower sternal defect; a deficiency of the anterior diaphragm; a defect in the diaphragmatic pericardium; and intracardiac anomalies [

3]. Class 1 (complete form) involves all five defects; Class 2 (probable form) involves four defects, specifically requiring both intracardiac and abdominal wall anomalies; and Class 3 (incomplete form) involves a variable combination of defects that do not meet the full criteria. Originally proposed by Toyama in 1972 [

44], this classification system remains the standard for the clinical and pathological diagnosis of the syndrome [

3].

Although congenital peritoneal-pericardial hernia is not one of the five classic anomalies defined in CS, it may be considered part of the Class 3 (Incomplete Form) spectrum when it occurs alongside other body wall defects. Class 3 includes variable combinations of the syndrome’s defining features, such as an abdominal wall defect, a lower sternal defect, an anterior diaphragmatic defect, a diaphragmatic pericardial defect and intracardiac anomalies, but does not require all five to be present. When a peritoneal-pericardial hernia occurs alongside partial sternal or diaphragmatic defects, or mild cardiac anomalies, this may indicate an atypical or incomplete manifestation of the syndrome. This interpretation aligns with Toyama’s classification framework, which allows for greater phenotypic variability in Class 3 presentations [

3].

2.3. Body Wall Defects Classification

Body wall defects were classified according to their anatomical location, structural characteristics and associated anomalies. Omphalocele was defined as a supraumbilical midline abdominal wall defect with herniated viscera enclosed in a sac made up of amnion and peritoneum [

26]. The term Ab was described as a big abdominal mid wall defects characterized by the absence of a protective membranous sac covering the herniated abdominal contents. Gastroschisis or right lateral Ab is a defect located to the side of the umbilicus that is usually uncovered and associated with evisceration of the abdominal contents [

45]. ThAb was characterised by a continuous defect extending from the thoracic to the abdominal wall, which was often associated with EC and severe disruption of the ventral body wall [

26]. Each condition was evaluated in relation to its embryological origin and phenotypic overlap with complex syndromes, such as PC and BSA. Diagnostic classification was guided by published criteria and a comparative morphological analysis of both the cases studied and those reviewed in the literature.

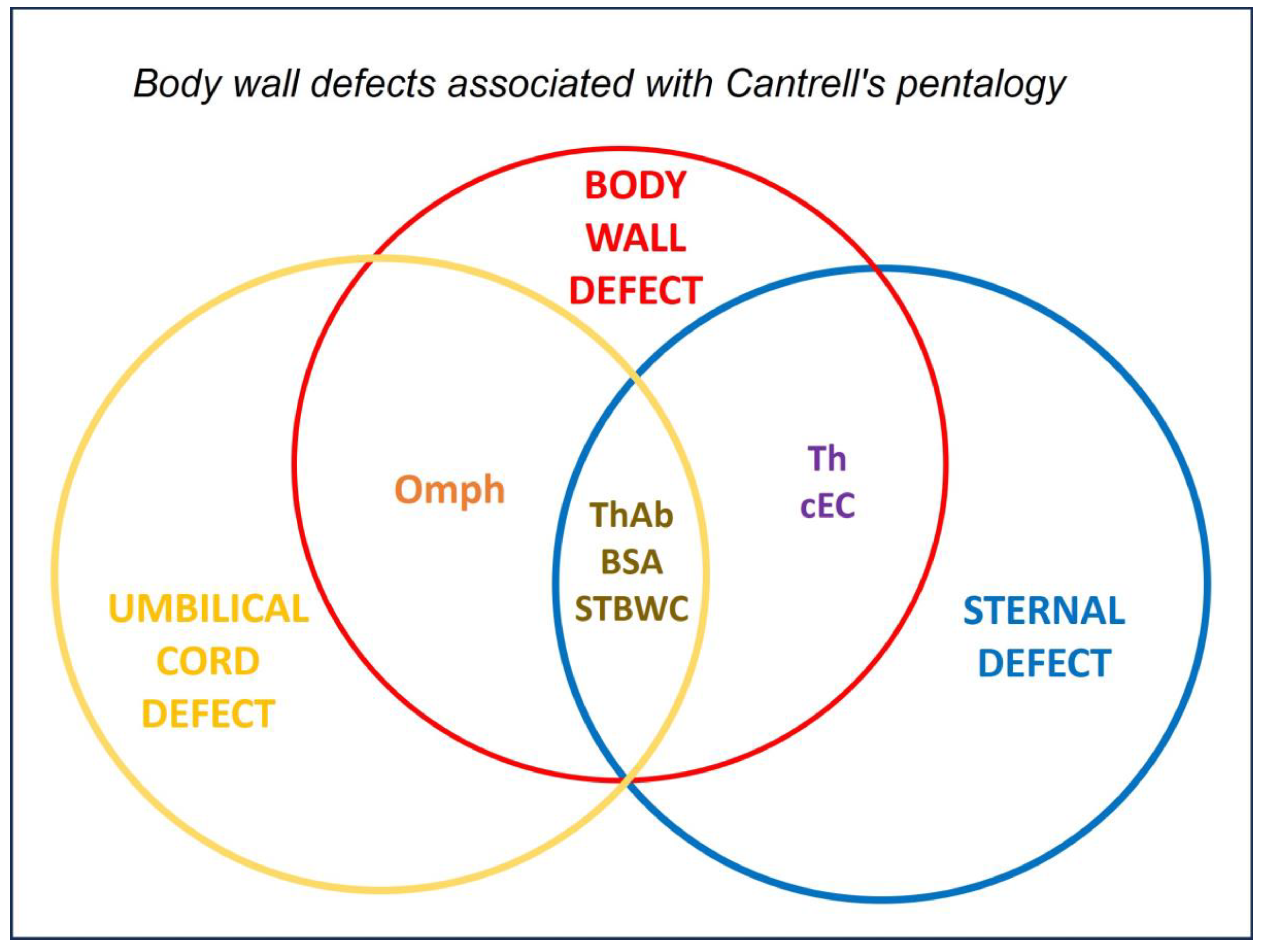

A Venn diagram was used to develop an anatomical classification framework that visualized the relationship between body wall defects and sternal defects. Representative conditions included omphalocele, Ab, ThAb and structural sternal defects. Thoracoschisis (Th) was positioned within both domains to reflect its dual involvement. Each dog case was mapped onto the diagram according to the location and extent of the defects. Embryological interpretation was guided by the known timeline of canine gestation, with a focus on the critical period of ventral body wall closure (gestational days 20–30). The anatomical findings were correlated with developmental timing in order to infer the origin and severity of each defect.

2.4. EC Classification

In this study, four distinct types of EC were considered based on their associated anatomical defects. Type 1 EC is characterized by a diaphragmatic defect accompanied by omphalocele or Ab and anomalous UC. Type 2 EC involves a sterno-costal defect, also known as Th, in conjunction with omphalocele or Ab and anomalous UC. Type 3 EC presents with a sterno-costal defect and supraumbilical Ab due to diastasis of the rectus abdominis muscles with normal UC. Type 4 EC is defined by a sterno-costal defect associated with gastroschisis with normal UC.

2.5. Bibliographic Review and Case Selection Criteria

A comprehensive bibliographic review was conducted to contextualize the observed anomalies and refine diagnostic classifications. Peer-reviewed veterinary pathology journals and online databases such as PubMed and Scopus were consulted. Keywords used included ‘Body Wall Defects’, ‘Body Stalk Anomaly’, ‘Ectopia Cordis’, ‘Pentalogy of Cantrell’, ‘Peritoneal Pericardial Diaphragmatic Hernia’ and ‘Amniotic Band Syndrome’. The search was further refined to target canine cases beyond the specified keywords. Relevant case reports and reviews were selected based on their descriptions of congenital malformations in canine specimens. A comparative analysis was performed between the published diagnoses and the anomalies observed in the present cases, enabling the proposal of refined diagnostic categories.

3. Results

3.1. Phenotypic and Classification Findings in Three Canine Cases of Thoracoabdominal Congenital Anomalies

Three cases of body wall defects in dogs were analyzed (

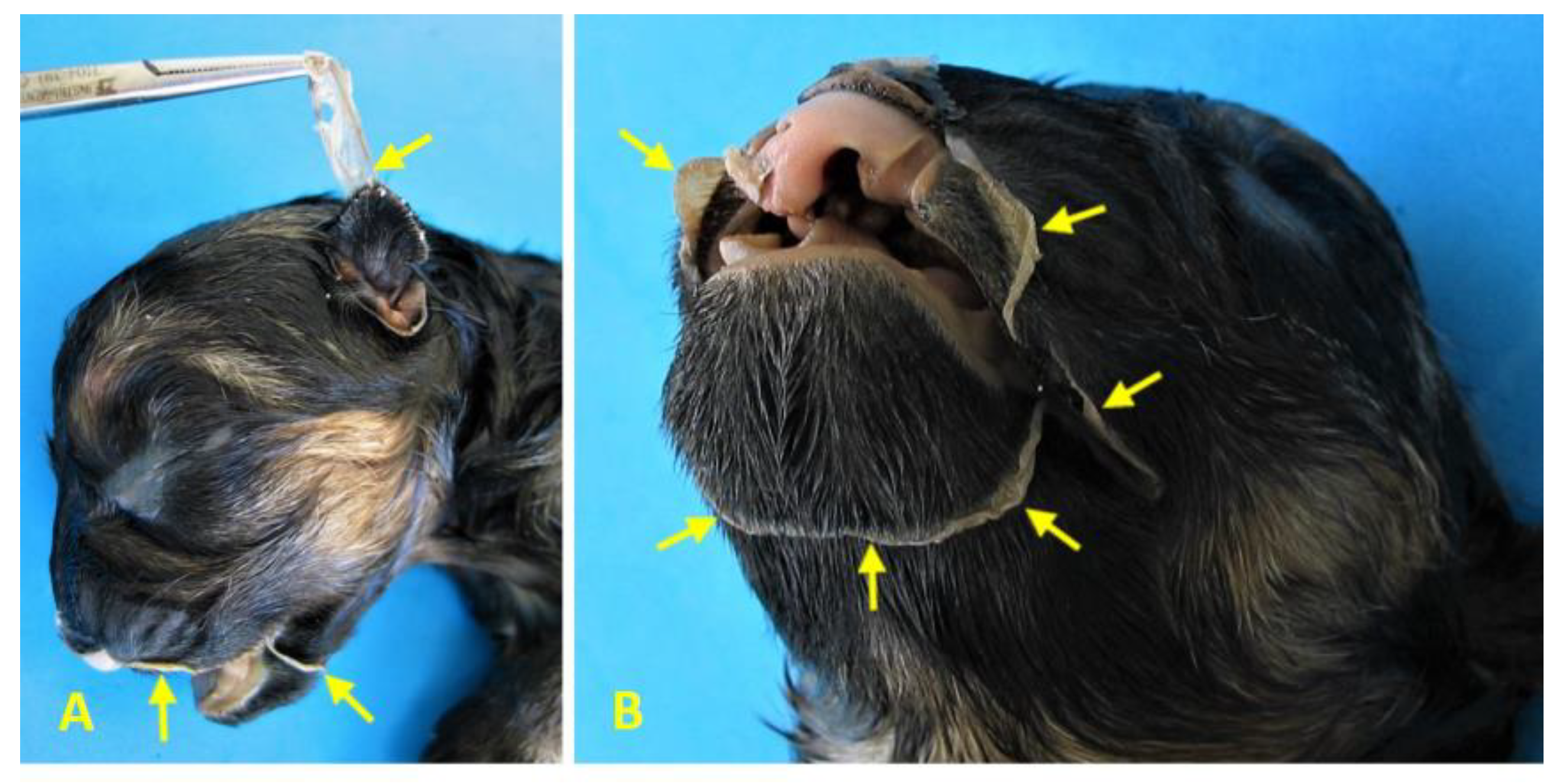

Figure 1), revealing distinct phenotypic and pathogenetic profiles.

All three dogs presented with ThAb, which is characterised by a continuous defect involving both the thoracic and abdominal walls. Of these cases, two exhibited central Ab and one showed gastroschisis. The first two cases also demonstrated abnormal UC development, with the cord either shortened or with umbilical vessels dispersed. This is consistent with features commonly seen in BSA. In contrast, the third case had a normally developed UC positioned next to the lateral abdominal defect (

Figure 2). These variations in defect location and UC morphology emphasize the phenotypic diversity of thoracoabdominal wall anomalies, supporting the classification of these cases as falling within a spectrum that includes both PC and BSA.

Case 1

A female German Shepherd, presented with ThAb and an abnormal UC (

Figure 1a). Skeletal anomalies included a short, cleft sternum (

Figure 3a). Agenesis of the ventral portion of the diaphragm was also present (

Figure 4). Pericardial agenesis was also present. The dog also had multiple cardiac anomalies, including ectopia cordis, mitral valve stenosis, tricuspid valve dysplasia, hypoplasia of the left ventricle (Figures 5a and 5b) and an atrial septal anomaly (

Figure 5c). She also had craniofacial defects, including bilateral cheiloschisis (

Figure 6a and Figure 6b), as well as cranial amniotic adhesions (

Figure 7a and Figure 7b), but no limb malformations. The diagnosis is consistent with BSA Type VI, ABS, and STBWC III, as well as PC Class 1.

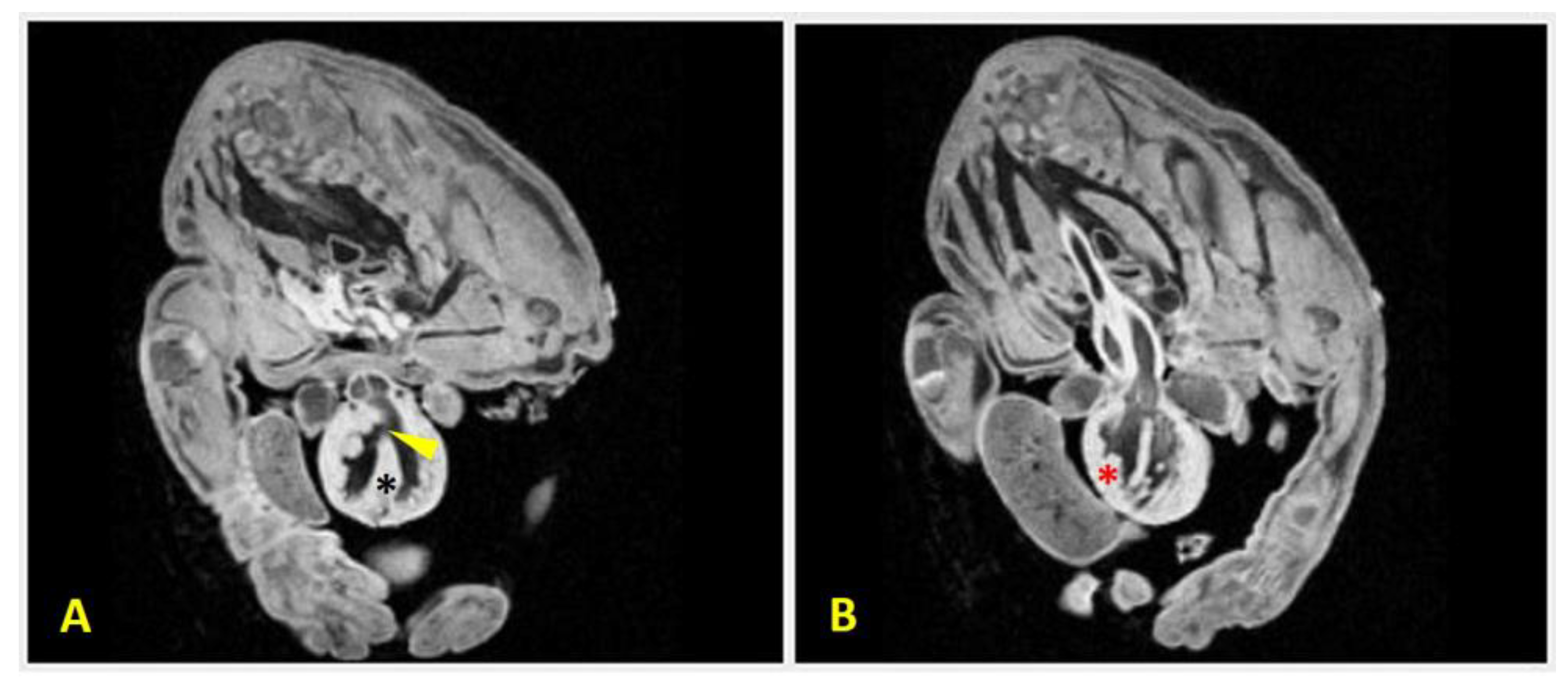

Case 2

A male Chihuahua presented with a thoracoabdominal disruption and an anomalous UC (

Figure 1b). There was also a structural spinal anomaly and sternum agenesis (

Figure 3b). Agenesia of the ventral portion of the diaphragm was also present. He also had an absent pericardium, EC, a globular heart, a ventricular septal defect, and right ventricular hypertrophy (

Figure 8a and Figure 8b), and secondary palatoschisis, but no limb malformations. Non-structural urogenital defects were also present. The diagnosis was classified as BSA Type V, STBWC Type III and PC Class 1.

Case 3

A male Chihuahua exhibiting lateral ThAb, a normal UC (

Figure 2), non-structural spinal defects, sternum agenesis (

Figure 3c), EC and right ventricular hypertrophy. However, it lacked craniofacial and limb anomalies. Non-structural urogenital defects were present. This aligns with pathogenetic classification class 2.

These cases emphasize the variability of the structural and cardiac manifestations of body wall complex anomalies and demonstrate the importance of an integrated morphological and pathogenetic classification system.

The Venn diagram (

Figure 9) shows how congenital anomalies affecting the body wall and sternum are distributed and overlap. Conditions such as omphalocele, Th and coelomic EC, ThAb and structural sternal defects were categorized as BWD. Notably, Th falls within both the BWD and sternal defect categories, reflecting its involvement in defects of both the thoracic wall and the sternum. BSA and ThAb occupied the intersection, indicating syndromic presentations with combined thoracic and abdominal wall failure. This framework enables the classification of the three dog cases, each of which presented with Th, within the overlapping region. Cases 1 and 2, which present with central Ab and UC involvement, align with Cantrell-like phenotypes. In contrast, Case 3 features gastroschisis and a normal UC, representing a variant form with asymmetric body wall disruption. Thus, the diagram provides a developmental and anatomical context for interpreting complex thoracoabdominal malformations.

3.2. Comparative Analysis of the Cases Studied and Bibliographically Reviewed Cases of CS, ABS, and BSA

A summary of the 20 cases including the original cases and those found in the bibliography research is shown in

Table 2, along with the diagnoses made by the authors and our proposed diagnoses and classifications.

Complex overlapping features were observed among PC, BSA and ABS across the three studied canine cases. Case 1 was classified as BSA Type VI with STBWC type III and PC Class 1, displaying features consistent with ABS. Case 2 was diagnosed as BSA Type V with SSBWC (sternal-spinal body wall complex) type III and PC Class 1. Case 3, which presented with lateral Ab, was classified as PC Class 2. The bibliographic review included 17 additional cases, most of which were classified as PC Class 1, reflecting complete or near-complete manifestations of the syndrome. These included cases with intracardiac defects (cases 5–8), a sternal cleft (case 9), and a congenital peritoneal–pericardial hernia (cases 10–13). Cases 14, 16 and 20 were categorized as PC Class 2, demonstrating partial expression of the syndrome, which often involves peritoneopericardial diaphragmatic hernias. Case 15 was diagnosed as incomplete PC, while Case 4 presented with a constellation of defects, including cranioventral, abdominal wall, caudal, sternal, diaphragmatic, pericardial and intracardiac anomalies, supporting a PC Class 1 classification. Three cases (17, 19 and 1) were classified as BSA with varying STBWC types and concurrent PC features, highlighting the frequent overlap between these syndromes. Case 18 was diagnosed as omphalocele and was interpreted by the authors as being part of the PC spectrum. These findings emphasize the diagnostic complexity and phenotypic continuum among PC, BSA and ABS, and reinforce the need for integrative classification frameworks that can accommodate overlapping morphologies.

The bibliographic review revealed a wide range of body wall defects in the reported cases, reflecting the phenotypic variability of congenital thoracoabdominal anomalies. Cranioventral abdominal wall defects were the most frequently described, appearing in five cases, and were often associated with complex, syndromic presentations. Umbilical hernias were noted in three cases, while supraumbilical cutaneous atrophy was documented in one case, suggesting localized developmental disruption. One case presented a subxiphoid or ventral hernia, likely containing hepatic parenchyma, based on historical imaging and clinical description. Another case presented with a midline abdominal wall defect characterised by a large supraumbilical diastasis rectus. More severe disruptions included Ab in one case and ThAb in two cases, both of which are indicative of an extensive failure of ventral body wall closure. These findings highlight the diagnostic complexity and overlapping features of body wall anomalies, especially when classifying cases within the PC or BSA frameworks.

3.3. Comparative Patterns and Distinguishing Features of CS, BSA and ABS

Table 3 summarizes the key patterns identified across the three syndromes studied, highlighting their distinguishing features and underlying causes observed during the analysis.

To highlight the distinguishing characteristics and underlying mechanisms of the analyzed syndromes, we compiled a comparative summary of their clinical features (

Table 2). This table reflects the patterns identified during the study, facilitating a clearer understanding of the conditions shared and unique traits. Features overlapping between PC and BSA were observed in four of the twenty canine cases analyzed, complicating their classification. All four dogs presented with thoracoabdominal wall defects and EC, as well as an anomalous — shortened or absent — UC, which are defining features of PC. However, two of the cases also exhibited structural limb (Case 17) and spinal (Case 2) anomalies, traits that are more typical of BSA. These findings suggest a phenotypic continuum between PC and BSA, particularly in incomplete forms, where the boundaries between the two conditions become less distinct. One case exhibited craniofacial and limb constriction anomalies that were reminiscent of amniotic band syndrome (ABS); however, the overall presentation was more consistent with BSA. This comparative analysis emphasizes the necessity of flexible diagnostic criteria when evaluating congenital anomalies with overlapping morphologies, particularly in veterinary pathology.

A comparison of revised cases in the bibliography reveals consistent differences in diagnosis due to the complexity of the conditions, their uncommon presentation in veterinary medicine, and the presence of overlapping elements that make a correct diagnosis challenging. This may inform future diagnostic or therapeutic approaches. We have organized the data in this format to provide a concise visual reference that supports the interpretation of our findings and highlights the importance of syndrome-specific profiles in veterinary clinical practice.

4. Discussion

BWD. Emmanuel et al. [

55] classify abdominal wall defects as occurring either along the midline or laterally. The latter is represented by gastroschisis [

45]. Midline defects can be categorized further based on their location: (1) at the site of UC insertion (omphalocele); (2) above the umbilicus (often resulting from separation of the rectus abdominis muscles, which may or may not be covered by skin); and (3) below the umbilicus (commonly associated with bladder or cloacal exstrophy). Our study revealed a wide spectrum of body wall defects, highlighting the phenotypic variability and diagnostic complexity of congenital thoracoabdominal anomalies. All three canine cases presented with ThAb, a severe defect involving the complete disruption of the thoracic and abdominal walls. Two of the cases presented with central Ab and anomalous UCs (either shortened or displaced), while the third case exhibited gastroschisis and a normally developed UC positioned adjacent to the defect. These findings suggest a developmental continuum between PC and BSA, particularly in cases involving extensive ventral wall disruption and UC abnormalities. The bibliographic review further expanded the range of observed defects. Cranioventral abdominal wall defects were the most frequently reported (five cases) [

46] and were often associated with complex syndromic presentations. Umbilical hernias (three cases) [

48,

51,

53] and supraumbilical cutaneous atrophy (one case) [

47] reflected milder forms of abdominal wall disruption. A subxiphoid or ventral hernia containing hepatic tissue and a midline abdominal wall defect with a large supraumbilical diastasis recti were each observed in one case [

49]

, indicating partial midline fusion failure. More severe anomalies included Ab (one case) [

50] and ThAb (two cases) [

21,

52], which are consistent with the findings in the canine cohort. Collectively, these defects illustrate a spectrum ranging from isolated abdominal wall anomalies to extensive thoracoabdominal disruptions, which are often accompanied by UC malformations and visceral herniation. Classifying them as PC, BSA or overlapping phenotypes requires careful anatomical and embryological assessment, especially when multiple defects coexist. This diversity highlights the need for flexible diagnostic frameworks and comparative analysis across species and literature sources.

The Embryological Basis of Abdominal Wall Defects in Three Studied Canine Cases. The three original canine cases in this study illustrate a spectrum of abdominal wall defects that can be traced back to disruptions during the early stages of embryonic development, specifically between days 20 and 35 of gestation in dogs — a critical period for the folding and closure of the lateral body wall [

26]. Case 1 was diagnosed as BSA Type VI with STBWC III and PC Class 1, as well as exhibiting features of ABS. This case presented with central ThAb and a short, malformed UC. This combination of anomalies indicates a significant failure in the closure of the ventral body wall, likely resulting from an early deficiency in the mesoderm and the persistence of the extraembryonic coelom, which prevented the amniotic sac from enclosing the embryo properly. The presence of ABS-like features may indicate mechanical disruption from ABs, which would compound the primary developmental defect [

27,

29]. Case 2, classified as BSA Type V with SSBWC III and PC Class 1, exhibited central ThAb alongside additional spinal anomalies and a displaced UC. These findings suggest a broader disruption to midline mesodermal development, affecting not only the ventral body wall, but also axial structures [

29]. The combination of sternal, spinal and abdominal defects is consistent with a more extensive embryological insult during the folding and segmentation stages. Case 3 was diagnosed as PC Class 2 and presented with gastroschisis and a normally developed UC. This pattern is more consistent with gastroschisis, which is believed to be caused by vascular disruption, particularly involving the right omphalomesenteric artery or umbilical vein [

55]. This leads to localized ischemia and failure of wall closure. The absence of a covering sac and the isolated nature of the defect also support this theory. Together, these cases exemplify the embryological continuum of abdominal wall defects in dogs, ranging from localized vascular disruptions (gastroschisis) to global folding failures (as seen in BSA and PC). Classifying them in this way highlights the importance of considering anatomical, embryological and morphological features when diagnosing and understanding these rare congenital anomalies.

The Venn diagram offers a developmental framework for interpreting thoracoabdominal wall defects, especially those affecting both the body wall and sternal structures. Th, which is included in both circles, reflects the dual anatomical involvement of this defect and serves as a bridging defect. All three of the dogs presented with Th, which places them within the overlapping region. Cases 1 and 2, which present with central Ab and UC anomalies, are similar to Cantrell-like syndromes, indicating an early disruption to midline fusion. Case 3 combines Th with gastroschisis and a normal UC, indicating a more localized defect that arose later in development. These variations likely reflect differences in regional timing or localized vascular events. Thus, the diagram supports a more nuanced classification of congenital anomalies, integrating anatomical location with embryological trajectory in order to distinguish between syndromic and non-syndromic phenotypes.

EC. Classifying the EC cases in this study revealed distinct anatomical patterns across the subtypes. Type 2 EC, identified in cases 1, 2, 17 and 19, was consistently characterised by a sterno-costal defect accompanied by omphalocele or Ab, as well as an anomalous UC. Type 3 EC, observed in cases 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 and 15, was characterised by a sternocostal defect and supraumbilical Ab due to diastasis of the rectus abdominis muscles, with a normal UC. Case 3 represented Type 4 EC and exhibited a sterno-costal defect associated with gastroschisis and a normal UC. As shown in the Venn diagram, there is some overlap in the occurrence of sterno-costal defects between types 2, 3 and 4. However, the morphology of the UC and the type of abdominal wall defect are key distinguishing features. This distribution supports the anatomical classification framework and highlights phenotypic variability within EC, which may have implications for prenatal diagnosis and surgical planning [

21].

CS, ABS and BSA syndromes. CS, ABS and BSA are rare congenital disorders that have some features in common but have different causes and clinical presentations. All three conditions can present with defects of the ventral body wall, including omphalocele and other abdominal wall abnormalities [

2,

25,

26,

27,

29,

43]. Limb and craniofacial defects are common in ABS and BSA and can also be seen in CS when associated with other anomalies (2, 27, 29). There is evidence that BSA, ABS and LBWC may represent a spectrum of early embryonic disruption [

25]. Cases have been reported that fit the diagnostic criteria for all three conditions, suggesting that they are part of a continuum rather than being strictly separate entities [

24]. ABS and BSA are usually sporadic and not associated with genetic factors or an increased risk of recurrence [

27].

Diagnostic overlap and syndromic continuum among CS, BSA, and ABS. Analysis of 20 canine cases — three original cases and 17 obtained through bibliographic review — revealed a complex spectrum of congenital thoracoabdominal anomalies. This highlighted significant diagnostic overlap between PC, BSA and ABS. The original cases (cases 1–3) showed extensive body wall defects; all three presented with ThAb. Cases 1 and 2 were classified as BSA Types VI and V, respectively, with both exhibiting STBWC III variants and PC Class 1; Case 1 also exhibited features consistent with ABS. Case 3 showed gastroschisis and a normally developed UC and was classified as PC Class 2, reflecting less complete expression of the syndrome. Of the 17 bibliographic cases (cases 4–20) [

21,

46,

47,

48,

49,

50,

51,

52,

53], the majority (13 cases) were classified as PC class 1 and often presented with intracardiac, diaphragmatic, pericardial and sternal defects. Four cases (cases 14, 16, 18 and 20) were classified as PC class 2 or 3 [

21,

49,

51,

52], indicating partial or atypical manifestations. Three of these cases (Cases 17, 18, and 19) [

21,

51] were also classified as BSA. Each case exhibited distinct STBWC subtypes and concurrent PC features. This finding reinforces the developmental and phenotypic overlap between these syndromes. The frequent co-occurrence of UC anomalies, ventral wall disruptions, and visceral herniation across the cases studied and reviewed supports the idea of a syndromic continuum rather than distinct entities. These findings emphasize the importance of integrative classification frameworks that accommodate variable morphologies and shared embryological origins, particularly when evaluating complex congenital anomalies in the context of veterinary and comparative pathology.

Clinical features and diagnostic criteria. CS is characterised by a pentalogy consisting of a midline abdominal wall defect (often an omphalocele), a lower sternal defect, an anterior diaphragmatic defect, a pericardial defect and congenital heart anomalies [

2]. ABS can present with a variety of anomalies ranging from constriction rings to complex limb amputations, craniofacial clefts and body wall defects. ABS is usually sporadic and non-genetic [

29]. BSA involves severe body wall defects, structural skeletal anomalies, a short or absent UC and a persistent extraembryonic coelom. The diagnostic criteria require UC defect, ThAb, limb, sternal and/or spinal structural defects [

25,

26,

27,

43]. Recent research highlights both the clinical and embryological overlap—such as shared ventral wall defects and structural skeletal anomalies —and the divergence in etiology, severity, and recurrence risk. In this study some cases demonstrate features of more than one syndrome, suggesting a possible continuum or spectrum of early embryonic disruption [

27].

Overlap and Spectrum. Both ABS and BSA exhibit similar characteristics, such as limb and body wall defects, and can present with ABs or adhesions [

27]. Some cases (C1) meet the criteria for both conditions, which supports the hypothesis of a spectrum [

27,

29]. There have been rare reports of cases with features of both CS and ABS or BSA, suggesting possible pathogenetic links or coincidental occurrence. In this study, four cases showed features of CS and BSA, and one case showed features of CS, BSA, and ABS. Studies in cats and pigs demonstrate comparable patterns of overlap, which supports the notion that mechanical and developmental disruption is relevant across species [

27,

43]. The literature demonstrates significant clinical and pathogenetic overlaps between CS, ABS and BSA, particularly in cases with severe or atypical presentations. The spectrum hypothesis is supported by cases that meet the criteria for more than one syndrome, as well as by animal models that show similar patterns of disruption (27, 29). However, important distinctions remain: CS is a defined pentalogy with possible genetic contributions, whereas ABS and BSA are usually sporadic and non-genetic, being associated with mechanical or vascular disruption [

25,

29,

43]. Recognizing these syndromes as distinct yet overlapping entities is crucial for accurate diagnosis and prognosis [

26,

27].

Pathogenesis and Etiology. CS is believed to arise from abnormal development of the ventral midline during early embryogenesis, possibly with genetic or environmental contributions [

2,

45]. Some authors have proposed that UC anomalies are part of the CS spectrum [

2,

56]. They suggest that these anomalies are the result of developmental disturbances that occur during blastogenesis and result in a polytopic field defect affecting the UC [

2,

56]. This interpretation corroborates the observed distinction in our cases, whereby individuals presenting with anomalous UCs appear to align with syndromic forms of PC, whereas those with normally inserted UCs tend to fall outside the syndromic spectrum. This suggests a potential developmental and diagnostic divide with origins in early blastogenic disruption. ABS most commonly attributed to early amnion rupture, leading to fibrous bands that entrap and disrupt developing fetal parts. Vascular disruption and mechanical compression are also implicated [

29]. BSA is thought to result from faulty embryonic folding, vascular disruption, or early amniotic rupture. The presence of amniotic bands in some cases supports pathogenetic overlap with ABS [

25,

26,

27,

43]. The quality of evidence is moderate to high for the clinical overlap and spectrum hypothesis, but lower for definitive pathogenetic mechanisms, especially regarding CS. The rarity of these conditions and variability in diagnostic criteria limit the strength of some conclusions.

5. Conclusions

This study highlights the diagnostic complexity and phenotypic variability of congenital thoracoabdominal anomalies in dogs, particularly within the spectrum of PC, BSA, and ABS. Among the 20 cases analyzed—three original and 17 bibliographically reviewed—most exhibited overlapping features that challenge rigid classification. The presence of ThAb, UC anomalies, and associated visceral and cardiac defects across multiple cases supports the concept of a syndromic continuum rather than distinct entities. These findings underscore the importance of integrative diagnostic frameworks that consider embryological origin, anatomical presentation, and cross-species comparisons to improve classification accuracy and deepen understanding of these rare but significant malformations. The inclusion of Th within both body wall and sternal defect categories highlights its role as a bridging anomaly in the spectrum of thoracoabdominal malformations. All three dog cases presented Th, supporting their classification within the overlapping region of the Venn diagram. Cases 1 and 2, with central Ab and UC anomalies, suggest an early embryological disruption consistent with syndromic patterns such as PC. Case 3, featuring gastroschisis and a normal UC, reflects a more localized defect likely arising later in development. These findings underscore the importance of integrating anatomical distribution with embryological timing to better classify and understand congenital anomalies. The diagram serves not only as a categorical tool but also as a developmental map for distinguishing syndromic and non-syndromic phenotypes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.M.A., and L.J.A.; methodology, N.M.A. L.J.A., and J.M.C.; validation, N.M.A. L.J.A., and J.M.C.; formal analysis, N.M.A. L.J.A., and J.M.C.; investigation, N.M.A. L.J.A., and J.M.C.; data curation, N.M.A. L.J.A., and J.M.C.; writing—original draft preparation, N.M.A.; writing—review and editing, N.M.A., and L.J.A.; supervision, NMA.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study did not require ethical approval.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Pedro Plaza Serrano for his help with the 3D reconstruction of the diagnostic scans taken at DB Diagnóstico por Imagen in Alcorcón, Madrid; the Singular Scientific-Technical Facility (ICTS) Bioimagen Complutense (BIOMAC); and SEDECAL MOLECULAR IMAGING S.L.U.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

A Absent

AB Amniotic band

Ab Abdominoschisis

ABS Amniotic band syndrome

ADC Amniotic disruption complex

Ag Agenesis

AgVP Agenesis of the ventral portion

Ao Aorta

ASD Atrial septal defect

BCh Bilateral cheiloschisis

BIOMAC Biomagen Complutense

BSA Body stalk anomaly

BT Birth type

BrT Brachiocephalic trunk

BWD Body wall defect

cdVC Caudal vena cava

cEC Coelomic Ectopia cordis

ChS Chorionic sac

CM Conception method

CrfD Craniofacial defect

CrvAWD Cranioventral abdominal wall defect

CrVC Cranial vena cava

CS Cantrell Syndrome

CT Computed Tomography

D Diaphragmatic

DD Diaphragmatic defect

EC Ectopia cordis

F Foreskin

GA Gallbladder agenesis

GH Globular heart

GT Gestation time

GuD Genitourinary defect

H Heart

HLV Hypoplasia of the left ventricle

Hp Hypoplasia

HR Hypoplastic ribs

ICTS Singular Scientific and Technical Facility

IL Intestinal loops

LBWC Limb body wall complex

L Liver

lSA Left subclavian artery

L-ThAb Lateral thoracoabdominoschisis

lV Left ventricle

LV-C Length of vertex cauda

MRI Magnetic resonance imaging

MVS Mitral valve stenosis

NS-B Breed not specified by authors

NS-G Gender not specified by authors

NSt Non-structural

OAAD Occipito-atlanto-axial defect

OD Other defects

Omph Omphalocele

P Pancreas

PC Pentalogy of Cantrell

PD Pericardial defect

PDA Patent ductus arteriosus

PLCVC Persistent left cranial vena cava

PP Primary palatoschisis

PPDH Peritoneopericardial diaphragmatic hernia

PS Pulmonary stenosis

rA Right auricle

rAt Right atrium

rV Right ventricle

RVH Right ventricular hypertrophy

S Spleen

SaS subaortic stenosis

Sc scoliosis

SCA Supraumbilical cutaneous atrophy

ScThEC Subcutaneous thoracic ectopia cordis

SP Secondary palatoschisis

SPBWC Spinal body wall complex

SPLBWC Spinal limb body wall complex

SSBWC Sternal spinal body wall complex

St Stomach

STBWC Sternal body wall complex

SpD Spinal defect

St Structural

StD Sternal defect

SUA Single umbilical artery

SUAWD Supraumbilical abdominal wall defect

SV Single ventricle

SXH Subxiphoid hernia

ThAb Thoracoabdominoschisis

TVD Tricuspid valve dysplasia

Ua Umbilical artery

UBCS Underdeveloped bifurcated caudal sternebra

UCD Umbilical cord defect

ud Undescribed

UH Umbilical hernia

Uv Umbilical vein

VSD Ventricular septal defect

References

- Cantrell, J.R.; Haller, J.A.; Ravitch, M.M. A syndrome of congenital defects involving the abdominal wall, sternum, diaphragm, pericardium, and heart. Surg Gynecol Obstet 1958, 107, 602–614. [Google Scholar]

- Martín-Alguacil, N.; Avedillo, L. Cantrell Syndrome (Thoracoabdominal Ectopia Cordis; Anomalous Umbilical Cord; Diaphragmatic, Pericardial and Intracardiac Defects) in the Pig (Sus scrofa domesticus). J Comp Pathol 2020, 174, 99–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Q.J.; Gao, Z.; Zhang, Z.W.; Li, J.H.; Ma, L.L.; Ying, L.Y. Correct definition of pentalogy of Cantrell. J Perinat Med 2009, 37, 426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, J.M.; Adrian, R.W. Ectopia cordis in cattle. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1962, 141, 1162–1167. [Google Scholar]

- Kurtz, H.J.; Ellery, J.C. Ectopia cordis in a bovine fetus. Am J Vet Res 1969, 30, 471–473. [Google Scholar]

- West, H.J.; Payne-Johnson, C.E. Ectopia cordis in two calves. Vet Rec 1987, 121, 108–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hiraga, T.; Abe, M.; Iwasa, K.; Takehana, K.; Tanigaki, A. Cervico-pectoral ectopia cordis in two Holstein calves. Vet Pathol 1993, 30, 529–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eröksüz, H.; Metin, N.; Eröksüz, Y. Total pectoral ectopia cordis and other congenital malformations in a calf. Vet Rec 1998, 142, 437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onda, K.; Sugiyama, M.; Niho, K.; Sato, R.; Arai, S.; Kaneko, K.; Ito, S.; Muto, M.; Suganuma, T.; Wakao, Y.; Wada, Y. Long-term survival of a cow with cervical ectopia cordis. Can Vet J 2011, 52, 667–669. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lopez, M.M.; Kuzma, A.B.; Margiocco, M.L.; Cheng, T.; Enberg, T.B.; Head, L. Cardiac malposition (ectopia cordis) in a cat. J Vet Emerg Crit Care (San Antonio) 2015, 25, 783–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cerqueira, L.A.; Mâcedo, I.L.; Sousa, D.E.R.; Amorim, H.A.L.; Borges, J.R.J.; Ximenes, F.H.B.; Câmara, A.C.L.; Castro, M.B. Complete Thoracic Ectopia Cordis in Two Lambs. Animals 2024, 14, 2213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joest, E. Spezielle Pathologische Anatomic der Haustiere. R. Schoetz: Berlin, Germany, 1925; pp 342-360.

- Notter, C. Scistosomen beim Schweine. Virchows Arch Pathol Anat 1927, 264, 280–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofliger, H. Über Organdystopien bei Haustieren mit besonderer Berücksichtigung der Ectopie cordis und der sog. Zwerchfellbrüche. Virchows Arch Pathol Anat 1936, 297, 627–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selby, L.A.; Hopps, H.C.; Edmonds, L.D. Comparative aspects of congenital malformations in man and swine. J Am Vet Med Ass 1971, 159, 1485–1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bille, N.; Nielsen, N.C. Congenital malformations in pigs in a post mortem material. Nord Vet Med 1977, 29, 128–136. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gruys, E.; Jansingh, J.; vd Linde-Sipman, J.S. [Umbilical hernia and ectopia cordis in a piglet (author’s transl)]. Tijdschrift voor diergeneeskunde 1978, 103, 498–500. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Huston, R.; Saperstein, G.; Schoneweis, D.; Leipold, H.W. Congenital defects in pigs. Vet Bull 1978, 48, 645–675. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, L.E.; McGovern, P.T. Ectopia cordis thoracoabdominalis in a piglet. Vet Rec 1984, 115, 431–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanagasuntheram, R.; Perumal Pillai, C. Ectopia Cordis and Other Anomalies in a Dog Embryo. Res Vet Sci 1960, 1, 172–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozdemir-Salci, E. S.; Yildirim, K. Thoracic ectopia cordis, sternal agenesis, partial ectopia hepatica and fissure abdominalis in a German Shepherd puppy with milder incomplete pentalogy of Cantrell. Clinical case. Revista Científica, FCV-LUZ, 2024, XXXIV, rcfcv-e34306. [CrossRef]

- Mărginean, C.; Mărginean, C.O.; Gozar, L.; Melit, L.E; Suciu, H.; Gozar, H.; Crisan, A.; Cucerea, M. Cantrell Syndrome-A Rare Complex Congenital Anomaly: A Case Report and Literature Review. Front Pediatr 2018, 6, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, B. R. , Duran, M. The confused identity of Cantrell’s pentad: Ectopia cordis is related either to thoracoschisis or to a diaphragmatic hernia with an omphalocele. Pediat Pathol Mol Med 2003, 22, 383–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Alguacil, N. Anatomy-based diagnostic criteria for complex body wall anomalies (CBWA). Mol Genet Genomic Med 2020, 8, e1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Alguacil, N.; Avedillo, L. Body stalk anomalies in pig-Definition and classification. Mol Genet Genomic Med 2020, 8, e1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martín-Alguacil, N.; Cozar, J.M.; Avedillo, L. Complex Body Wall Closure Defects in Seven Dog Fetuses: An Anatomic and CT Scan Study. Animals 2025, 15, 2030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martín-Alguacil, N.; Cozar, J.M.; Avedillo, L. Body stalk anomalies and their relationship to amniotic band disruption complex in six cats. J Feline Med Surg 2025, 27, 1098612X251341068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rittler, M.; Campaña, H.; Poletta, F. A.; Santos, M. R.; Gili, J. A.; Pawluk, M. S.; Consentino, V.R.; Gimenez, L.; Lopez-Camelo, J. S. Limb body wall complex: Its delineation and relationship with amniotic bands using clustering methods. Birth Defects Res 2019, 111, 222–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Alguacil, N.; Avedillo, L. Body wall defects and amniotic band syndrome in pig (Sus scrofa domesticus). Anat Histol Embryol 2020, 49, 144–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halder, A. Amniotic band syndrome and/or limb body wall complex: split or lump. Appl Clin Genet 2010, 3, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishi, T.; Nakano, R. Amniotic band syndrome: Serial ultrasonographic observations in the first trimester. J Clin Ultrasound. 1994, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clancy, B.; Darlington, R.B.; Finlay, B.L. Translating developmental time across mammalian species. Neuroscience. 2001, 105, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zambelli, D.; Caneppele, B.; Bassi, S.; Paladini, C. Ultrasound Aspects of Fetal and Extrafetal Structures in Pregnant Cats. JFMS. 2002, 4, 106–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, K.; Venkatesan, B.; Chandra, T.; Rajeswari, K.; Devi, T. K. Amniotic band syndrome with sacral agenesis and umbilical cord entrapment: A case report emphasizing the value of evaluation of umbilical cord. J Radiol Case Report 2015, 9, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seeds, J.W.; Cefalo, R.C.; Herbert, W.N. Amniotic band syndrome. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1982, 144, 243–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.P.; Gorla, S.R. Amniotic Band Syndrome. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih. 5452. [Google Scholar]

- Agerholm, J.S.; Garoussi, M.T. Intrauterine idiopathic amputation of the head of a porcine foetus. Reprod Domest Anim. 2013, 48, e38–e40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seeds, J.W.; Cefalo, R.C.; Herbert, WN. Amniotic band syndrome. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1982, 144, 243–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callaghan, M.B.; Hadden, R.; King, J.S. , Lachlan, K.; van Dijk, F.S.; Turnpenny, P.D. Amniotic band sequence in paternal half-siblings with vascular Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. Am J Med Genet A 2020, 182, 553–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torpin, R. Amniochorionic mesoblastic fibrous strings and amniotic bands: associated constricting fetal malformations or fetal death. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1965, 91, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinker, B.; Vasconez, H.C. Constriction band syndrome occurring in the setting of in vitro fertilization and advanced maternal age. Can J Plast Surg 2006, 14, 41–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lockwood, C.; Ghidini, A.; Romero, R.; Hobbins, J.C. Amniotic band syndrome: reevaluation of its pathogenesis. Am J Obst Gynecol 1989, 160, 1030–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Alguacil, N.; Cozar, J.M.; Avedillo, L.J. Body Stalk Anomalies in Pigs: Current Trends and Future Directions in Classification. Animals 2025, 15, 460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toyama, W.M. Combined congenital defects of the anterior abdominal wall, sternum, diaphragm, pericardium and heart. Pediatrics 1972, 50, 778–792. [Google Scholar]

- Martín-Alguacil, N. , Avedillo, L. Body Wall Defects: Gastroschisis and Omphalocoele in Pigs (Sus scrofa domesticus). J Comp Pathol 2020, 175, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellah, J.R.; Spencer, C.P.; Brown, D.J.; Whitton, D.L. Congenital cranioventral abdominal wall, caudal sternal, diaphragmatic, pericardial, and intracardiac defects in Cocker Spaniel littermates. J Am Vet Med Assoc, 1741. [Google Scholar]

- Benlloch-Gonzalez, M.; Poncet, C. Sternal Cleft Associated with Cantrell’s Pentalogy in a German Shepherd Dog. J Am Anim Hosp Asso. [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, J.L.; Gunther-Harrington, C.T.; Sutton, J.S.; Stern, J.A. Multiple midline defects identified in a litter of golden retrievers following gestational administration of prednisone and doxycycline: a case series. BMC Vet Res. [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Sajik, D.; Calvo, I.; Philips, A. Novel peritoneopericardial diaphragmatic hernia in a dog. Vet Rec Case Rep 2019, 7, e000896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, P.; Booth, M.; Rossanese, M. Incomplete pentalogy of Cantrell in a Border terrier puppy. Vet Rec Case Rep 2020, 8, e001188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennink, I.; Düver, P.; Rytz, U.; Meneses, F.; Moioli, M.; Adamik, K.N.; Kovacevic, A. Case Report: Unusual Peritoneopericardial Diaphragmatic Hernia in an 8-Month-Old German Shepherd Dog, Associated With a Pericardial Pseudocyst and Coexisting Severe Pericardial Effusion Resulting in Right-Sided Heart Failure. Front Vet Sci 2021, 8, 673543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- So, W.; Donahoe, S.L.; Podadera, J.M.; Mazrier, H. Pentalogy of Cantrell in Two Neonate Littermate Puppies: A Spontaneous Animal Model Suggesting Familial Inheritance. Animals 2023, 13, 2091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campanile, D.; Cafaro, M.; Paci, S.; Panarese, M.; Sparapano, G.; Masi, M.; De Simone, A. Evidence of pneumopericardium after elective ovariectomy in a peritoneopericardial diaphragmatic hernia-affected dog: A case report. Animals 2024, 14, 633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eldessouky, S.; Abdella, R.; Gaafar, H.; Fouad, M.; Sobh, S.; Eid, M.; Abdalla, E.; Ebrashy, A.; Zolfokar, D. Prenatal Diagnosis of Fetal Ventral Wall Defects: Associated Anomalies and Chromosomal Aberrations. Evidence Based Women’s Health Journal. 2023, 13, 395–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmanuel, P.G.; Garcia, G.I. ; AngtuacoTL Prenatal detection of anterior abdominal wall defects with US. Radiographics 1995, 15, 517–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brochut, A.C.; Baumann, M.U.; Kuhn, A.; Di Naro, E.; Tutschek, B.; Surbek, D.; Raio, L. Pentalogy or hexalogy of Cantrell? Pediatr Dev Pathol 2011, 14, 396–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Congenital body wall defects in three canine cases. (A) Left lateral view of Case 1 (female German Shepherd) showing ThAb with externalized viscera. (B) Ventral view of Case 2 (male Chihuahua) also exhibiting ThAb. (C) Ventral view of Case 3 (male Chihuahua) displaying lateral ThAb. In all cases, note the exposure of the heart (H), liver (L), stomach (St), spleen (S) and intestinal loops (arrows heads) through the body wall defect into the extraembryonic coelomic cavity. Case 3 retains an intact UC. ChS, chorionic sac; Ua, umbilical artery; Uv, umbilical vein. Scale bar: 5 cm.

Figure 1.

Congenital body wall defects in three canine cases. (A) Left lateral view of Case 1 (female German Shepherd) showing ThAb with externalized viscera. (B) Ventral view of Case 2 (male Chihuahua) also exhibiting ThAb. (C) Ventral view of Case 3 (male Chihuahua) displaying lateral ThAb. In all cases, note the exposure of the heart (H), liver (L), stomach (St), spleen (S) and intestinal loops (arrows heads) through the body wall defect into the extraembryonic coelomic cavity. Case 3 retains an intact UC. ChS, chorionic sac; Ua, umbilical artery; Uv, umbilical vein. Scale bar: 5 cm.

Figure 2.

Ventral view of case 3 (a male Chihuahua) with normal umbilical cord (arrows heads) implantation. The defect in the body wall can also be seen to correspond to a lateral location, rather than compromising the midline of the body. F, foreskin; H, heart; IL, intestinal loops; L, liver; S, spleen. Scale bar: 1 cm.

Figure 2.

Ventral view of case 3 (a male Chihuahua) with normal umbilical cord (arrows heads) implantation. The defect in the body wall can also be seen to correspond to a lateral location, rather than compromising the midline of the body. F, foreskin; H, heart; IL, intestinal loops; L, liver; S, spleen. Scale bar: 1 cm.

Figure 3.

Computed tomography views of thoracic and cervical malformations in three canine cases. (A) Right dorsolateral view of case 1 (female German Shepherd) showing a bifid sternum; the yellow arrows mark the three left sternites and the red arrows mark the four right sternites. (B) Left lateral view of case 2 (male Chihuahua) showing the complete sternal agenesis (asterisk), as well as the fusion (arrow head) of the bodies of the second (c2), third, fourth and fifth (c5) cervical vertebrae and the existing atlanto-axial-occipital malformation. (C) Ventral view of case 3 (male Chihuahua) showing complete sternal agenesis (asterisk), right scoliosis and hypoplasia of the left ribs corresponding to hypoplasia of the left thoracic wall.

Figure 3.

Computed tomography views of thoracic and cervical malformations in three canine cases. (A) Right dorsolateral view of case 1 (female German Shepherd) showing a bifid sternum; the yellow arrows mark the three left sternites and the red arrows mark the four right sternites. (B) Left lateral view of case 2 (male Chihuahua) showing the complete sternal agenesis (asterisk), as well as the fusion (arrow head) of the bodies of the second (c2), third, fourth and fifth (c5) cervical vertebrae and the existing atlanto-axial-occipital malformation. (C) Ventral view of case 3 (male Chihuahua) showing complete sternal agenesis (asterisk), right scoliosis and hypoplasia of the left ribs corresponding to hypoplasia of the left thoracic wall.

Figure 4.

Ventral view of Case 1 (female German Shepherd) showing the body wall defect. A prominent ventral diaphragmatic defect (arrows) is visible, allowing the heart (H) to protrude externally without being covered by the parietal pericardium. This is consistent with cardiac ectopia. The diaphragm (D), intestinal loops (IL), liver (L), pancreas (P) and stomach (St) are also visible, exposed through the thoracoabdominal defect. Scale bar: 3 cm.

Figure 4.

Ventral view of Case 1 (female German Shepherd) showing the body wall defect. A prominent ventral diaphragmatic defect (arrows) is visible, allowing the heart (H) to protrude externally without being covered by the parietal pericardium. This is consistent with cardiac ectopia. The diaphragm (D), intestinal loops (IL), liver (L), pancreas (P) and stomach (St) are also visible, exposed through the thoracoabdominal defect. Scale bar: 3 cm.

Figure 5.

Cardiac morphology in case 1 (female German Shepherd). (A) Left side of the heart highlighting the enlarged right auricle (rA) and hypoplasia of the left ventricle (lV). (B) Right-side view showing marked dilatation of the right atrium (rAt) and hypoplasia of the left ventricle (lV). (C) An internal view of the right atrium (rAt) reveals a prominent interatrial defect (asterisk), which creates direct communication between the right and left atria. Ao, aorta; BrT, brachiocephalic trunk; cdVC, caudal vena cava; crVC, cranial vena cava; LSa, left subclavian artery; rV, right ventricle.

Figure 5.

Cardiac morphology in case 1 (female German Shepherd). (A) Left side of the heart highlighting the enlarged right auricle (rA) and hypoplasia of the left ventricle (lV). (B) Right-side view showing marked dilatation of the right atrium (rAt) and hypoplasia of the left ventricle (lV). (C) An internal view of the right atrium (rAt) reveals a prominent interatrial defect (asterisk), which creates direct communication between the right and left atria. Ao, aorta; BrT, brachiocephalic trunk; cdVC, caudal vena cava; crVC, cranial vena cava; LSa, left subclavian artery; rV, right ventricle.

Figure 6.

Craniofacial anomalies in case 1 (female German shepherd). (A) Rostral view of the face showing bilateral cheiloschisis (arrows), characterised by clefts affecting both sides of the upper lip. (B) A ventrorostral view of the roof of the oral cavity reveals primary palatoschisis (arrowhead), which is a midline cleft of the primary palate. These findings are consistent with craniofacial anomalies that are commonly associated with body wall complex malformations.

Figure 6.

Craniofacial anomalies in case 1 (female German shepherd). (A) Rostral view of the face showing bilateral cheiloschisis (arrows), characterised by clefts affecting both sides of the upper lip. (B) A ventrorostral view of the roof of the oral cavity reveals primary palatoschisis (arrowhead), which is a midline cleft of the primary palate. These findings are consistent with craniofacial anomalies that are commonly associated with body wall complex malformations.

Figure 7.

Cranial amniotic adhesions in Case 1 (female German Shepherd). (A) Left lateral view and (B) left ventrolateral view of the head reveal adhesions of the amniotic membrane (arrows) to the left auricular pavilion and along a circumferential line encasing the oronasal region, including the mentonian area. These findings are consistent with ABS and suggest early disruption of embryonic development affecting craniofacial structures.

Figure 7.

Cranial amniotic adhesions in Case 1 (female German Shepherd). (A) Left lateral view and (B) left ventrolateral view of the head reveal adhesions of the amniotic membrane (arrows) to the left auricular pavilion and along a circumferential line encasing the oronasal region, including the mentonian area. These findings are consistent with ABS and suggest early disruption of embryonic development affecting craniofacial structures.

Figure 8.

MRI scans of Case 2 (male Chihuahua) demonstrating congenital cardiac anomalies. Two transversal sections of the MRI scan reveal:(A) a ventricular septal defect (arrowhead), which is visible as a discontinuity in the interventricular septum (black asterisk), allowing communication between the ventricles; and (B) right ventricular hypertrophy which is evidenced by thickening of the right ventricular wall (red asterisk). These findings support the diagnosis of complex structural heart malformations associated with body wall defects.

Figure 8.

MRI scans of Case 2 (male Chihuahua) demonstrating congenital cardiac anomalies. Two transversal sections of the MRI scan reveal:(A) a ventricular septal defect (arrowhead), which is visible as a discontinuity in the interventricular septum (black asterisk), allowing communication between the ventricles; and (B) right ventricular hypertrophy which is evidenced by thickening of the right ventricular wall (red asterisk). These findings support the diagnosis of complex structural heart malformations associated with body wall defects.

Figure 9.

Anatomical relationship between body wall and sternal defects. Venn diagram illustrating the anatomical and developmental overlap between body wall defects (red circle) and sternal defects (blue circle). Th is positioned within both domains, reflecting its dual involvement. BSA and STBWC occupy the intersection, representing syndromic conditions with combined thoracic and abdominal wall failure. This framework supports the classification of the three dog cases, all presenting Th, within the overlapping region, with variations in abdominal defect location and UC involvement. BSA, Body Stalk Anomaly; cEC, celomic Ectopia cordis; Omph, omphalocele; STBWC, Sternal Body Wall Complex; Th, Thoracoschisis; ThAb, Thoracoabdominoschisis.

Figure 9.

Anatomical relationship between body wall and sternal defects. Venn diagram illustrating the anatomical and developmental overlap between body wall defects (red circle) and sternal defects (blue circle). Th is positioned within both domains, reflecting its dual involvement. BSA and STBWC occupy the intersection, representing syndromic conditions with combined thoracic and abdominal wall failure. This framework supports the classification of the three dog cases, all presenting Th, within the overlapping region, with variations in abdominal defect location and UC involvement. BSA, Body Stalk Anomaly; cEC, celomic Ectopia cordis; Omph, omphalocele; STBWC, Sternal Body Wall Complex; Th, Thoracoschisis; ThAb, Thoracoabdominoschisis.

Table 1.

Characteristics of dogs included in the study (experimental group).

Table 1.

Characteristics of dogs included in the study (experimental group).

| Case |

Sex |

Weight

(gr) |

LV-C (cm) |

BWD (cm) |

BIRTH INFORMATION |

Breed |

| BT |

Dam’s age

(years) |

Litter size |

GT

(days) |

CM |

| C1 |

F |

665 |

19.3 |

7.3 x 3.1 |

C-section |

4 |

2 |

65 |

IA |

German Shepherd |

| C2 |

M |

55 |

7.8 |

1.2 x 0.7 |

C-section |

1,5 |

3 |

61 |

IA |

Chihuahua |

| C3 |

F |

110 |

10.9 |

3.5 x 1.2 |

C-section |

3 |

3 |

62 |

NM |

Chihuahua |

Table 2.

Summary of congenital defects identified in each canine case, including original diagnoses by cited authors and proposed diagnostic classifications based on integrated morphological and pathogenetic analysis.

Table 2.

Summary of congenital defects identified in each canine case, including original diagnoses by cited authors and proposed diagnostic classifications based on integrated morphological and pathogenetic analysis.

| Reference / Case |

BWD |

SpD |

UCD |

LD |

SD |

DD |

PD |

CD |

CrfD |

UGD |

ABS |

Author’s Diagnosis |

Proposed diagnosis |

| C1 |

Case 1 ♀

German shepherd |

ThAb |

- |

+ |

- |

Short and cleft |

AgVP |

Ag |

cEC, MVS, ASD, HLV, TVD |

EC

Type 2 |

BCh, PP

|

- |

+ |

BSA TYPE VI

STBWC III

PC Class 1

ABS

|

| C2 |

Case 2 ♂

Chihuahua |

ThAb |

VF,

OAAD |

+ |

- |

Ag |

AgVP |

A |

cEC, GH, VSD, RVH |

EC

Type 2 |

SP |

NSt |

- |

BSA TYPE V

SSBWC III

PC Class 1

|

| C3 |

Case 3 ♂

Chihuahua |

L-ThAb |

Sc |

- |

- |

Ag |

AgVP |

A |

cEC, RVH |

EC

Type 4 |

- |

NSt |

- |

PC Class 2 |

Bellah et al., 1989

[46] |

Case 4

NS-G

Cocker spaniel |

CrvAWD |

- |

- |

- |

Short and cleft |

V-shaped |

Caudo-ventral |

ScThEC, VSD |

EC

Type 3 |

- |

- |

- |

Congenital cranioventral abdominal wall, caudal sternal, diaphragmatic, pericardial, and intracardiac defects |

PC Class 1 |

Case 5

NS-G

Cocker spaniel |

CrvAWD |

- |

- |

- |

Short and cleft |

V-shaped |

Caudo-ventral |

ScThEC, VSD |

EC

Type 3 |

- |

- |

- |

Congenital cranioventral abdominal wall, caudal sternal, diaphragmatic, pericardial, and intracardiac defects |

PC Class 1 |

Case 6

NS-G

Cocker spaniel |

CrvAWD |

- |

- |

- |

Short and cleft |

V-shaped |

Caudo-ventral |

ScThEC, VSD |

EC

Type 3 |

- |

- |

- |

Congenital cranioventral abdominal wall, caudal sternal, diaphragmatic, pericardial, and intracardiac defects |

PC Class 1 |

Case 7

NS-G

Cocker spaniel |

CrvAWD |

- |

- |

- |

Short and cleft |

V-shaped |

Caudo-ventral |

ScThEC |

EC

Type 3 |

- |

- |

- |

Congenital cranioventral abdominal wall, caudal sternal, diaphragmatic, and pericardial defects |

PC Class 1 |

Case 8

NS-G

Cocker spaniel |

CrvAWD |

- |

- |

- |

Short and cleft |

V-shaped |

Caudo-ventral |

ScThEC |

EC

Type 3 |

- |

- |

- |

Congenital cranioventral abdominal wall, caudal sternal, diaphragmatic, and pericardial defects |

PC Class 1 |

Benllock-González and

Poncet, 2015

[47] |

Case 9 ♂

German shepherd |

SCA |

- |

- |

- |

Caudal cleft |

Large

V-shaped |

Caudo-ventral |

PDA, PLCVC |

- |

- |

- |

- |

Sternal Cleft Associated with Cantrell’s Pentalogy |

PC Class 1 |

Kaplan et al., 2018

[48] |

Case 10 NS-G

NS-B |

- |

- |

- |

- |

UBCS |

PPDH |

PPDH |

VSD, SaS |

- |

- |

- |

- |

PPDH |

PC Class 1 |

Case 11 NS-G

NS-B |

UH |

- |

- |

- |

UBCS |

PPDH |

PPDH |

VSD, SaS |

- |

- |

- |

- |

PPDH |

PC Class 1 |

Case 12 NS-G

NS-B |

- |

- |

- |

- |

UBCS |

PPDH |

PPDH |

VSD, SaS |

- |

- |

- |

- |

PPDH |

PC Class 1 |

| Case 13 NS |

- |

- |

- |

- |

UBCS |

PPDH |

PPDH |

VSD, SaS |

- |

- |

- |

- |

PPDH |

PC Class 1 |

Khan et al., 2019

[49] |

Case 14 ♂

German shepherd |

SXH |

- |

- |

- |

Short |

PPDH |

Cranial |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

PPDH |

PC Class 2 |

Williams et al., 2020

[50] |

Case 15 ♂

Border terrier |

SUAWD |

- |

- |

- |

Short and cleft |

Central |

D |

ScThEC |

EC

Type 3 |

- |

- |

- |

Incomplete pentalogy of Cantrell |

PC Class 1 |

Hennink et al., 2021

[51] |

Case 16 ♂

German shepherd |

UH |

- |

- |

- |

Short and cleft |

PPDH |

D |

- |

- |

- |

-- |

|

Unusual peritoneopericardial diaphragmatic hernia associated with a pericardial pseudocyst |

PC Class 2 |

So et al., 2023

[52] |

Case 17 ♂

Epagneul papillón |

ThAb |

- |

ud |

PM |

Ag |

Hp |

Ag |

cEC, ud |

EC

Type 2 |

- |

NSt |

- |

Pentalogy of Cantrell |

BSA TYPE V

STLBWC III

PC Class 1

|

Case 18 ♂

Epagneul papillón |

Ab |

- |

ud |

- |

- |

Hp |

- |

ud |

- |

- |

- |

- |

Pentalogy of Cantrell |

Omphalocele |

Ozdemir-Salci and Yildirim

2024

[21] |

Case 19 ♂

German shepherd |

ThAb |

- |

ud |

- |

Ag |

- |

- |

cEC |

EC

Type 2 |

- |

- |

- |

Thoracic ectopia cordis, sternal agenesis, partial ectopia hepática and fissure abdominalis |

BSA TYPE VI

STBWC III

PC Class 3

|

Campanile et al., 2024

[53] |

Case 20 ♀

Mixed

breed |

UH |

- |

- |

- |

Cleft |

Central |

PPDH |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

PPDH |

PC Class 2 |

Table 3.

Comparative features and underlying causes of the three syndromes studied, including bibliographically reviewed and the three cases studied.

Table 3.

Comparative features and underlying causes of the three syndromes studied, including bibliographically reviewed and the three cases studied.

| Syndrome |

Key Patterns |

Etiology/Pathogenesis |

REF |

Cases |

CS |

Anomalous UC, midline-umbilical abdominal defect, cleft sternum, incomplete diaphragm and pericardium, EC and intracardiac anomalies |

Abnormal cephalic folding, possible chromosomal involvement |

[2,52,54] |

C1, C2, C3, C4, C5, C6, C7, C8, C9, C10, C11, C12, C13, C14, C15, C16, C17, C19, C20 |

ABS |

Constriction rings, limb amputations, craniofacial and BWD |

Amniotic membrane rupture, fibrous band entrapment, resulting in deformation, malformation or disruption |

[29,36] |

C1 |

BSA |

Body wall defects, structural skeletal anomalies, anomalous UC, persistent extraembryonic coelom |

Faulty folding in all three embryonic axes |

[26,27,43] |

C1, C2, C17, C19 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).