Submitted:

01 October 2025

Posted:

02 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Study Design and Setting

Study Population

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Data Collection

Statistical Analysis

Ethical Considerations

3. Results

4. Discussion

Demographic Characteristics

Types of Congenital Anomalies

Factors Associated with Survival and Mortality

Public Health and Preventive Effects

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

References

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2021). Primary health care approaches for prevention and control of congenital and genetic disorders : report of a WHO meeting, Cairo, Egypt, 6–8 December 1999. Retrieved November 21, 2021, from https:// apps. who.int/ iris/ handle/ 10665/ 66571.

- World Health Organization. Congenital anomalies [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; [cited 2025 Aug 6]. Available from: https://www.who.int/health-topics/congenital-anomalies#tab=tab_1.

- Bashir M., Javed J., Ameer R., Khan R., & Khan H. Frequency and pattern of git anomalies in neonates: a retrospective study at nicu mayo hospital lahore. PJMHS 2022;16(5):937-938. [CrossRef]

- Khoshnood B. , Greenlees R. , Loane M. , & Dolk H. Paper 2: eurocat public health indicators for congenital anomalies in europe. Birth Defects Research Part A: Clinical and Molecular Teratology 2011;91(S1). [CrossRef]

- Bhide P., Gund P., & Kar A. Prevalence of congenital anomalies in an indian maternal cohort: healthcare, prevention, and surveillance implications. Plos One 2016;11(11):e0166408. [CrossRef]

- Alahakoon A., Ratnayake C., Karunakaran K., & Tennakoon S. Do anomalous stillbirths have risk to be delivered preterm? a cross-sectional study conducted in kandy, sri lanka. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Kapurubandara S, Melov SJ, Shalou ER, Mukerji M, Yim S, Rao U, et al. A perinatal review of singleton stillbirths in an Australian metropolitan tertiary centre. PLoS One. 2017;12(2):e0171829. [CrossRef]

- Yudiasari P., Pramatirta A., & Gondodiputro S. Suspectable risk factors of congenital anomaly in dr. hasan sadikin general hospital bandung, indonesia. Althea Medical Journal 2017;4(2):257-260. [CrossRef]

- Self L., Dagenais L., & Shevell M. Congenital non-central nervous system malformations in cerebral palsy: a distinct subset?. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology 2012;54(8):748-752. [CrossRef]

- Boyle B., Addor M., Arriola L., Barišić I., Bianchi F., Csáky-Szunyogh M.et al. Estimating global burden of disease due to congenital anomaly: an analysis of european data. Archives of Disease in Childhood - Fetal and Neonatal Edition 2017;103(1):F22-F28. [CrossRef]

- Sheridan E. , Wright J. , Small N. , Corry P. , Oddie S. , Whibley C. et al. Risk factors for congenital anomaly in a multiethnic birth cohort: an analysis of the born in bradford study. The Lancet 2013;382(9901):1350-1359. [CrossRef]

- Sallout, B., Obedat, N., Shakeel, F., Mansoor, A., Walker, M., & Al-Badr, A. (2015). Prevalence of major congenital anomalies at king fahad medical city in saudi arabia: a tertiary care centre-based study. Annals of Saudi Medicine, 35(5), 343-351. [CrossRef]

- Dolk H, Loane M, Garne E. The prevalence of congenital anomalies in Europe. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2010;686:349–64. PMID: 20824455. [CrossRef]

- Goldsmith S. , McIntyre S. , Hansen M. , & Badawi N. Congenital anomalies in children with cerebral palsy: a systematic review. Journal of Child Neurology 2019;34(12):720-727. [CrossRef]

- Atkinson D., Amin F., Russell S., & D’Souza S. Fetal congenital anomalies diagnosed by ultrasound in asian and non-asian women. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 2008;28(7):678-682. [CrossRef]

- Anane-Fenin B, Opoku DA, Chauke L. Prevalence, pattern, and outcome of congenital anomalies admitted to a neonatal unit in a low-income country—a ten-year retrospective study. Matern Child Health J. 2023;27(6):837–849. [CrossRef]

- Zedan A, El-Sayed H, Sanfaz SMF. Frequency of Congenital Malformation in Neonatal Intensive Care Unit in Benghazi–Libya. Zagazig Univ Med J. 2020;26(1):148–155. [CrossRef]

- Rizk F, Salameh P, Hamadé A. Congenital anomalies: prevalence and risk factors. Univ J Public Health. 2014;2(2):58–63. [CrossRef]

- Mashhadi Abdolahi H, Kargar Maher MH, Afsharnia F, Dastgiri S. Prevalence of congenital anomalies: a community-based study in the northwest of Iran. ISRN Pediatr. 2014;2014:920940. [CrossRef]

- Elghanmi A, Razine R, Jou M, Berrada R. Congenital malformations among newborns in Morocco: A retrospective study. Pediatr Rep. 2020;12(1):7405. [CrossRef]

- El Koumi MA, Al Banna EA, Lebda I. Pattern of congenital anomalies in newborn: a hospital-based study. Pediatr Rep. 2013;5(1):e5. [CrossRef]

- Luo P, Li Q, Yan B, Xiong Y, Li T, Ding X and Mei B (2024) Prevalence, characteristics and risk factors of birth defects in central China livebirths, 2015–2022. Front. Public Health 12:1341378.

- Rasmussen, S. A., Chu, S. Y., Kim, S. Y., Schmid, C. H., & Lau, J. (2008). Maternal obesity and risk of neural tube defects: a metaanalysis. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology, 198(6), 611-619.

- Davidoff MJ, Petrini J, Damus K, Russell RB, Mattison D. Neural tube defect-specific infant mortality in the United States. Teratology 2002;66(suppl):S17-22.

- Ouyang L, Grosse SD, Armour BS, Waitzman NJ. Health care expenditures of children and adults with spina bifida in a privately insured US population. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol 2007;79:552-8.

- Petterson B, Bourke J, Leonard H, Jacoby P, Bower C. Co-occurrence of birth defects and intellectual disability. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 2007;21:65-75.

- Oakeshott P, Hunt GM. Long-term outcome in open spina bifida. Br J Gen Pract 2003; 53:632-6.

- De La Vega A, Lopez-Cepero R. Seasonal variations in the incidence of some congenital anomalies in Puerto Rico based on the timing of conception. P R Health Sci J. 2009;28(2):121–6.

| n | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal age (n=956) | Under 25 years old | 379 | 39,6 |

| 25-35 years | 332 | 34,7 | |

| Over 35 years old | 245 | 25,6 | |

|

Pregnancy week (n=951) |

Under 24 weeks | 415 | 43,6 |

| 24-36 weeks | 239 | 25,1 | |

| 37-41 weeks | 293 | 30,8 | |

| 42 weeks and over | 4 | 0,4 | |

|

Maternal BMI (n=295) |

Underweight (<18.5 kg/m2) | 6 | 2,0 |

| Normal (18.5-24.9 kg/m2) | 81 | 27,5 | |

| Overweight (25-29.9 kg/m2) | 134 | 45,4 | |

| Obese (≥30 kg/m2) | 74 | 25,1 | |

|

Maternal comorbidities (n=557) |

None | 488 | 87,6 |

| Diabetes Mellitus | 8 | 1,4 | |

| Thyroid function disorders | 6 | 1,1 | |

| Anaemia | 13 | 2,3 | |

| Cardiac diseases | 5 | 0,9 | |

| Hypertension | 18 | 3,2 | |

| Other | 19 | 3,4 | |

| Mode of delivery (n=895) | Normal birth | 138 | 15,4 |

| Caesarean section | 433 | 43,4 | |

| Therapeutic abortion | 315 | 35,2 | |

| Hysterotomy | 9 | 1,0 | |

| Fetal sex (n=764) | Girl | 354 | 46,3 |

| Male | 398 | 52,1 | |

| Undetectable | 12 | 1,6 | |

| n | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| City | Diyarbakır | 298 | 31,5% |

| Mardin | 204 | 21,6% | |

| Şırnak | 177 | 18,7% | |

| Batman | 76 | 8,0% | |

| Siirt | 36 | 3,8% | |

| Urfa | 30 | 3,2% | |

| Bitlis | 24 | 2,5% | |

| Bingöl | 20 | 2,1% | |

| Muş | 18 | 1,9% | |

| Syrian refugee | 32 | 3,4% | |

| Others | 31 | 3,3% | |

| n | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Anomalous types (n=951) | CNS anomalies | 423 | 44,2 |

| Facial anomalies | 4 | 0,4 | |

| Musculoskeletal anomalies | 30 | 3,1 | |

| Cardiac anomalies | 90 | 9,4 | |

| Abdominal wall anomalies | 23 | 2,4 | |

| Thoracic anomalies | 27 | 2,8 | |

| Urinary anomalies | 83 | 8,7 | |

| Genital anomalies | 1 | 0,1 | |

| Gastrointestinal system anomalies | 46 | 4,8 | |

| Suspected chromosomal abnormalities | 41 | 4,3 | |

| Multiple anomalies | 85 | 8,9 | |

| Cystic hygroma | 98 | 10,3 | |

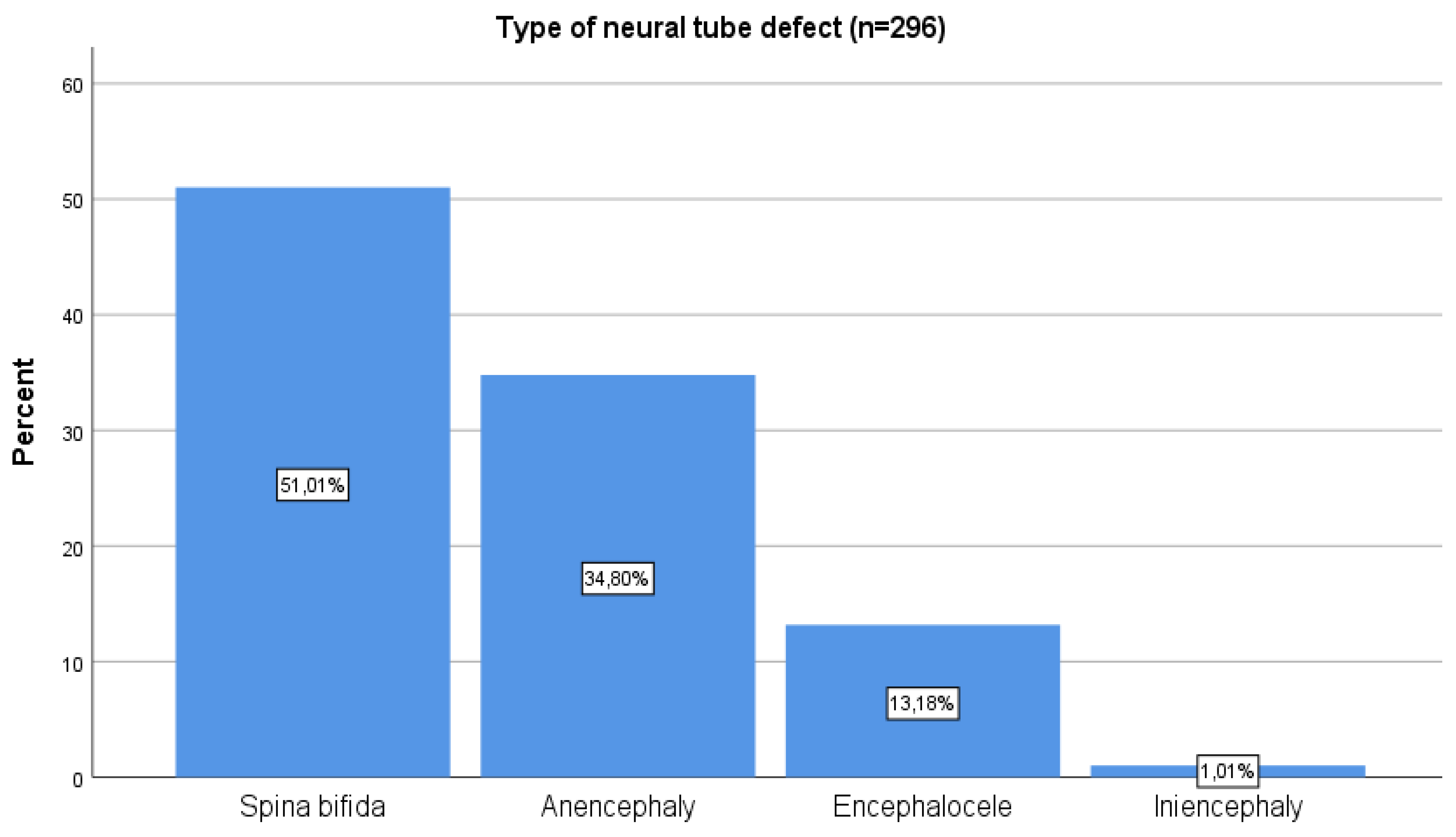

| Neural tube defect (n=939) | Yes | 299 | 31,8 |

| No | 640 | 68,2 | |

| Anomalous types | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CNS | Cardiac | Urinary | Multiple | Cystic hygroma | Neural tube defect | |||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Diyarbakır | 91 | 23,4 | 40 | 44,4 | 30 | 35,7 | 33 | 40,2 | 39 | 33,6 | 63 | 21,1 |

| Mardin | 86 | 22,1 | 19 | 21,1 | 18 | 21,4 | 16 | 19,5 | 30 | 25,9 | 62 | 20,7 |

| Şırnak | 102 | 26,2 | 6 | 6,7 | 10 | 11,9 | 10 | 12,2 | 18 | 15,5 | 91 | 30,4 |

| Batman | 25 | 6,4 | 8 | 8,9 | 7 | 8,3 | 10 | 12,2 | 9 | 7,8 | 16 | 5,4 |

| Siirt | 16 | 4,1 | 3 | 3,3 | 6 | 7,1 | 2 | 2,4 | 3 | 2,6 | 13 | 4,3 |

| Bingöl | 11 | 2,8 | 3 | 3,3 | 1 | 1,2 | 2 | 2,4 | 2 | 1,7 | 7 | 2,3 |

| Urfa | 13 | 3,3 | 6 | 6,7 | 2 | 2,4 | 0 | 0,0 | 2 | 1,7 | 10 | 3,3 |

| Bitlis | 11 | 2,8 | 2 | 2,2 | 4 | 4,8 | 0 | 0,0 | 2 | 1,7 | 10 | 3,3 |

| Muş | 7 | 1,8 | 0 | 0,0 | 3 | 3,6 | 5 | 6,1 | 1 | 0,9 | 4 | 1,3 |

| Syrian refugee | 18 | 4,6 | 1 | 1,1 | 0 | 0,0 | 1 | 1,2 | 6 | 5,2 | 15 | 5,0 |

| Others | 9 | 2,3 | 2 | 2,2 | 3 | 3,6 | 3 | 3,7 | 4 | 3,4 | 8 | 2,7 |

| Mean | Standard deviation | Median | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age of mother (years) | 28.37 | 6.68 | 28.00 |

| Number of gravida | 3.62 | 2.59 | 3.00 |

| Number of parities | 2.03 | 2.10 | 2.00 |

| Number of abortions | 0.61 | 1.06 | 0.00 |

| Number of live births | 1.87 | 1.97 | 1.00 |

| Pregnancy week | 27.65 | 9.66 | 29.75 |

| Fetal weight (grams) | 1841.83 | 1305.15 | 2100.00 |

| Maternal BMI (kg/m2) | 27,48 | 4,42 | 27.20 |

| Length of hospital stay (days) | 2.60 | 1.23 | 2.00 |

| Survival | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Live birth (%) | Stillbirth (%) | |||

| Maternal age | Under 25 years old | 33,1 | 19,6 |

0.144 |

| 25-35 years | 51,8 | 62,7 | ||

| Over 35 years old | 15,1 | 17,6 | ||

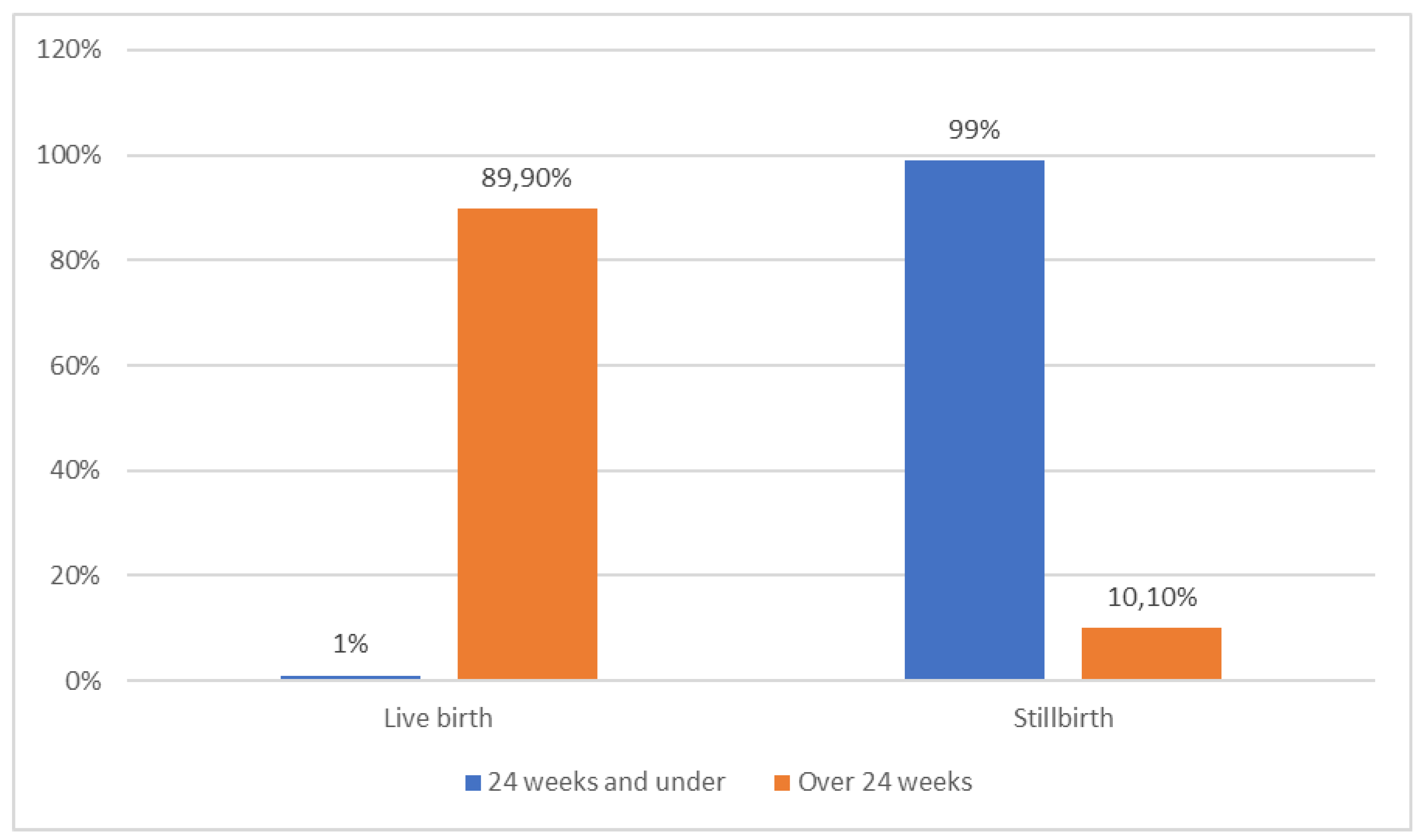

| Mode of delivery | Normal birth | 13,4 | 49,0 |

<0.001 |

| Caesarean section | 86,6 | 49,0 | ||

| Therapeutic abortion | 0,0 | 2,0 | ||

| Pregnancy week | 24-36 weeks | 36,6 | 94,1 |

<0.001 |

| 37-41 weeks | 62,5 | 5,9 | ||

| 42 weeks and over | 0,9 | 0,0 | ||

|

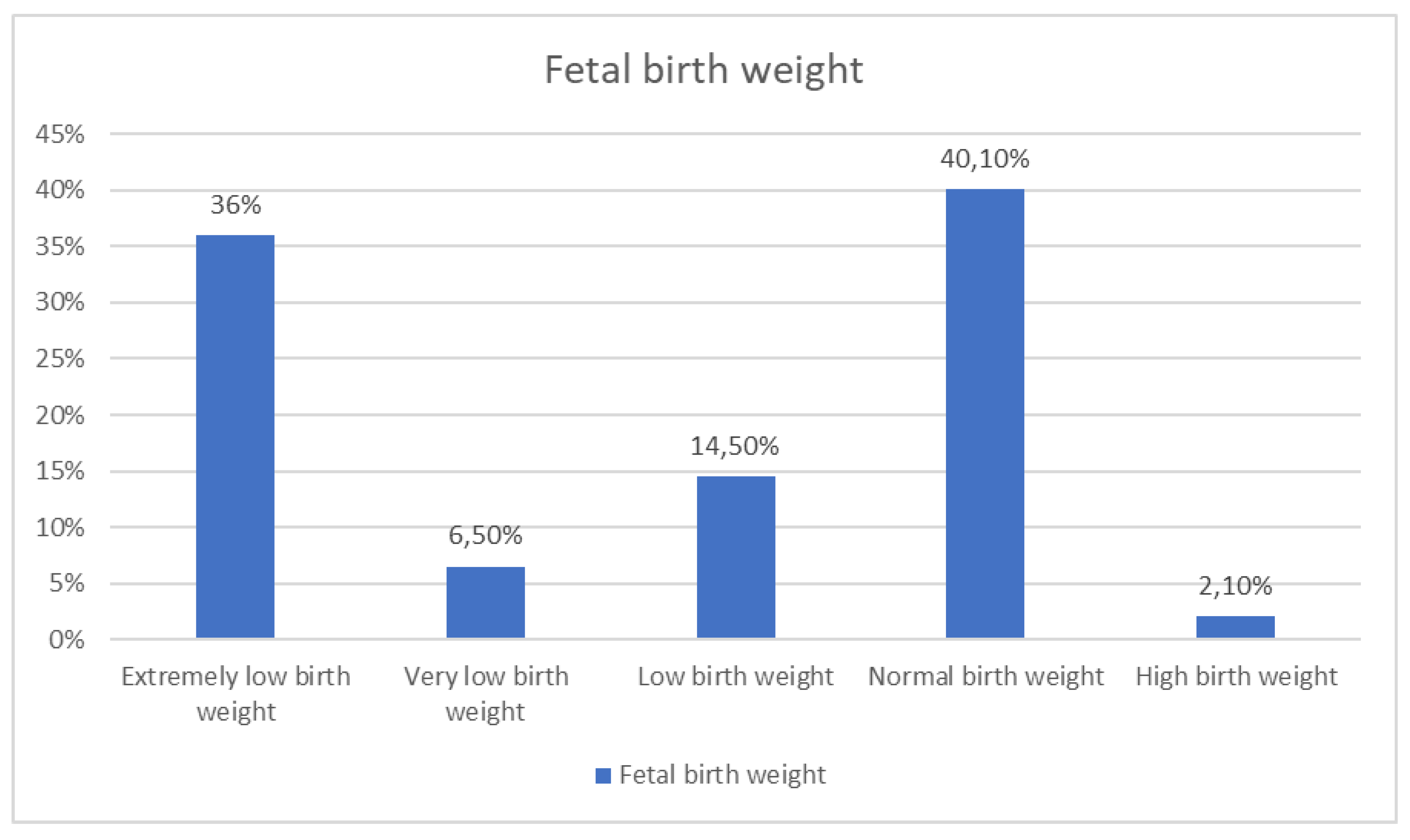

Fetal birth weight |

Extremely low birth weight | 1,3 | 36,0 |

<0.001 |

| Very low birth weight | 6,4 | 34,0 | ||

| Low birth weight | 21,9 | 14,0 | ||

| Normal birth weight | 67,8 | 10,0 | ||

| Excess birth weight | 2,6 | 6,0 | ||

| Fetal sex | Girl | 48,9 | 62,7 | 0.061 |

| Boy | 51,1 | 37,3 | ||

| Survival | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Live birth (%) | Stillbirth (%) | |||

| Anomalous types | CNS anomalies | 37,3 | 39,2 | <0.001 |

| Facial anomalies | 0,9 | 0,0 | ||

| Musculoskeletal anomalies | 3,9 | 3,9 | ||

| Cardiac anomalies | 16,4 | 5,9 | ||

| Abdominal wall anomalies | 4,6 | 3,9 | ||

| Thoracic anomalies | 5,0 | 0,0 | ||

| Urinary anomalies | 62.0 | 38.0 | ||

| Genital anomalies | 10,5 | 7,8 | ||

| GIS anomalies | 5,9 | 0,0 | ||

| Suspected chromosomal abnormalities | 4,2 | 2,0 | ||

| Multiple anomalies | 4,8 | 19,6 | ||

| Cystic hygroma | 6,4 | 17,6 | ||

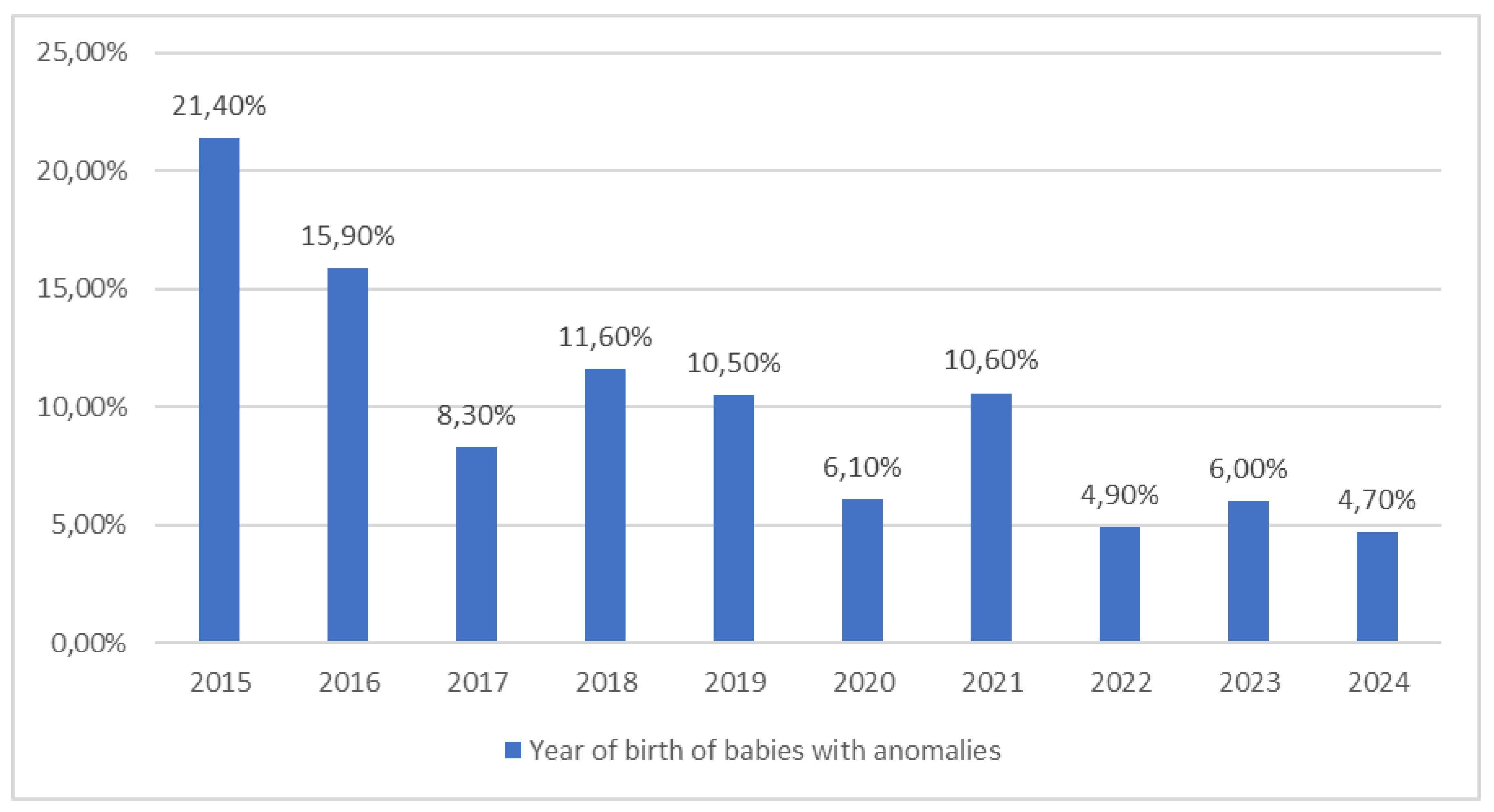

| Year of birth | 2015 | 25,2 | 19,6 | 0,002 |

| 2016 | 19,7 | 13,7 | ||

| 2017 | 11,0 | 15,7 | ||

| 2018 | 10,5 | 13,7 | ||

| 2019 | 6,8 | 5,9 | ||

| 2020 | 3,5 | 17,6 | ||

| 2021 | 7,7 | 3,9 | ||

| 2022 | 3,7 | 5,9 | ||

| 2023 | 5,7 | 3,9 | ||

| 2024 | 6,1 | 0,0 | ||

| Number of abortions | ||

|---|---|---|

| Maternal age | r | 0,271 |

| p | <0,001 | |

| Gravida | r | 0,627 |

| p | <0,001 | |

| Parities | r | 0,284 |

| p | <0,001 | |

| Survival regression analysis | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||||||||

| B | p |

Exp (B) |

95.0% Confidence Interval for B |

B |

p |

Exp (B) |

95.0% Confidence Interval for B | |||

| Lower Bound | Upper Bound | Lower Bound | Upper Bound | |||||||

| Age of mother | 0,035 | 0,122 | 1,035 | 0,991 | 1,082 | |||||

| Number of gravida | 0,045 | 0,395 | 1,046 | 0,942 | 1,162 | |||||

| Number of parities | 0,045 | 0,501 | 1,046 | 0,917 | 1,194 | |||||

| Number of abortions | 0,094 | 0,435 | 1,098 | 0,868 | 1,391 | |||||

| Pregnancy week | -0,411 | <0,001 | 0,663 | 0,606 | 0,726 | -0,296 | 0,048 | 0,744 | 0,555 | 0,997 |

| Fetal birth weight | -0,002 | <0,001 | 0,998 | 0,998 | 0,999 | -0,001 | 0,085 | 0,999 | 0,997 | 1,000 |

| Maternal BMI | 0,170 | 0,034 | 0,844 | 0,721 | 0,987 | 0,113 | 0,323 | 0,893 | 0,714 | 1,118 |

| Length of hospital stay | 0,033 | 0,783 | 1,034 | 0,817 | 1,308 | |||||

| Fetal sex (girl) | -0,565 | 0,063 | 0,568 | 0,313 | 1,032 | |||||

| Fetal birth weight (low) | 2,580 | <0,001 | 13,193 | 6,040 | 28,819 | -0,310 | 0,857 | 0,734 | 0,026 | 21,101 |

| Neural tube defect (present) | -0,574 | 0,068 | 0,563 | 0,304 | 1,043 | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).