Submitted:

03 January 2026

Posted:

05 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

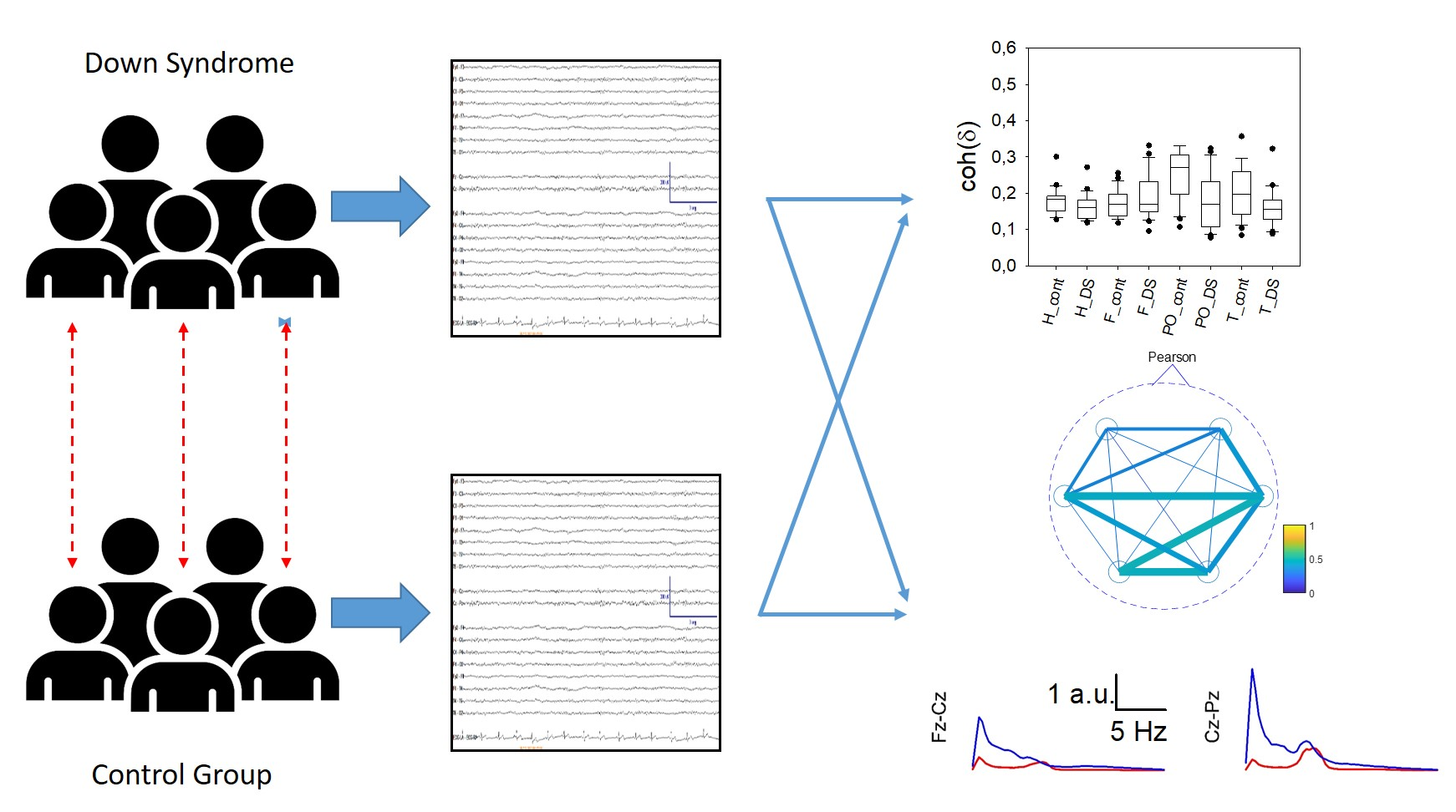

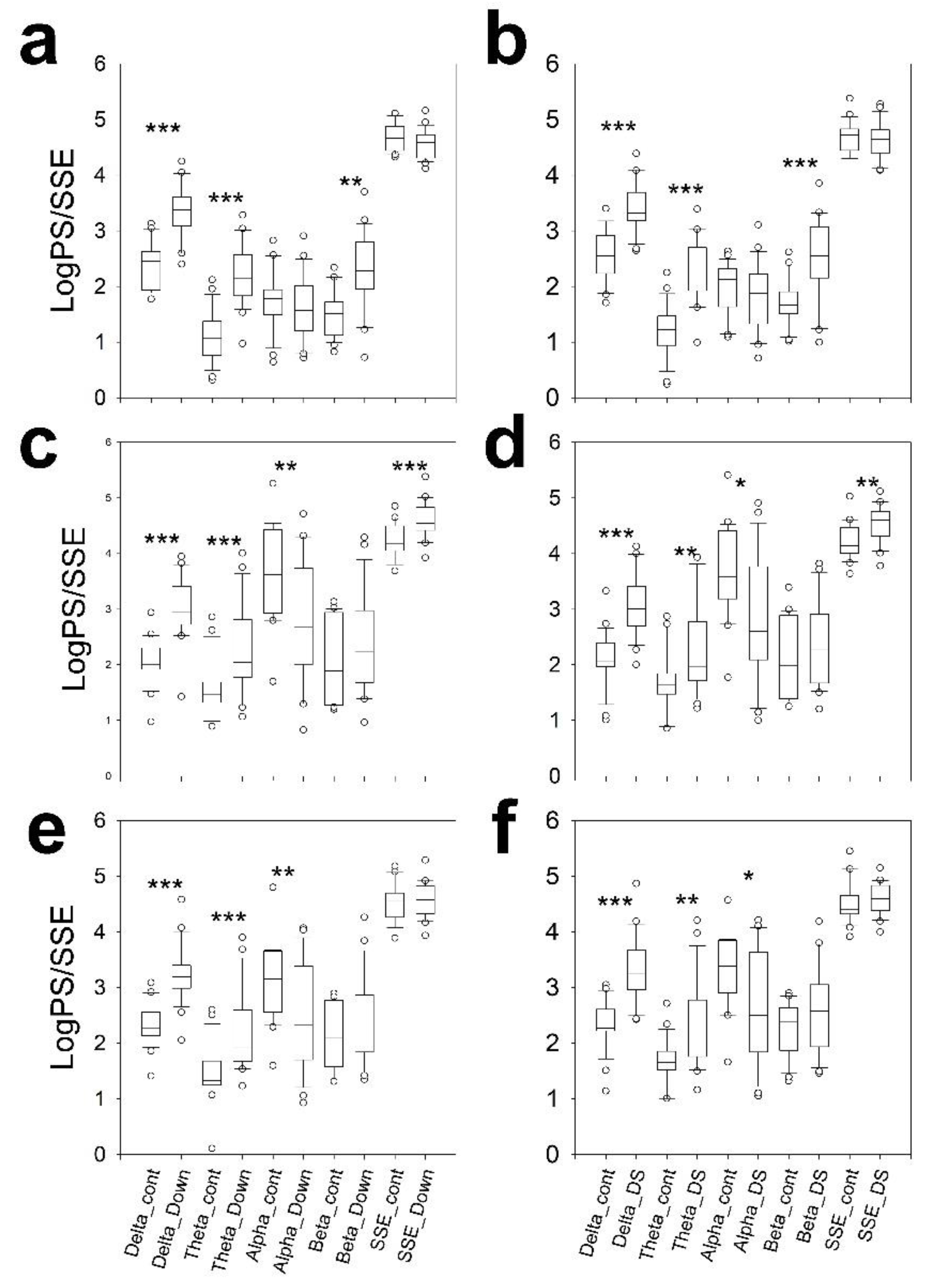

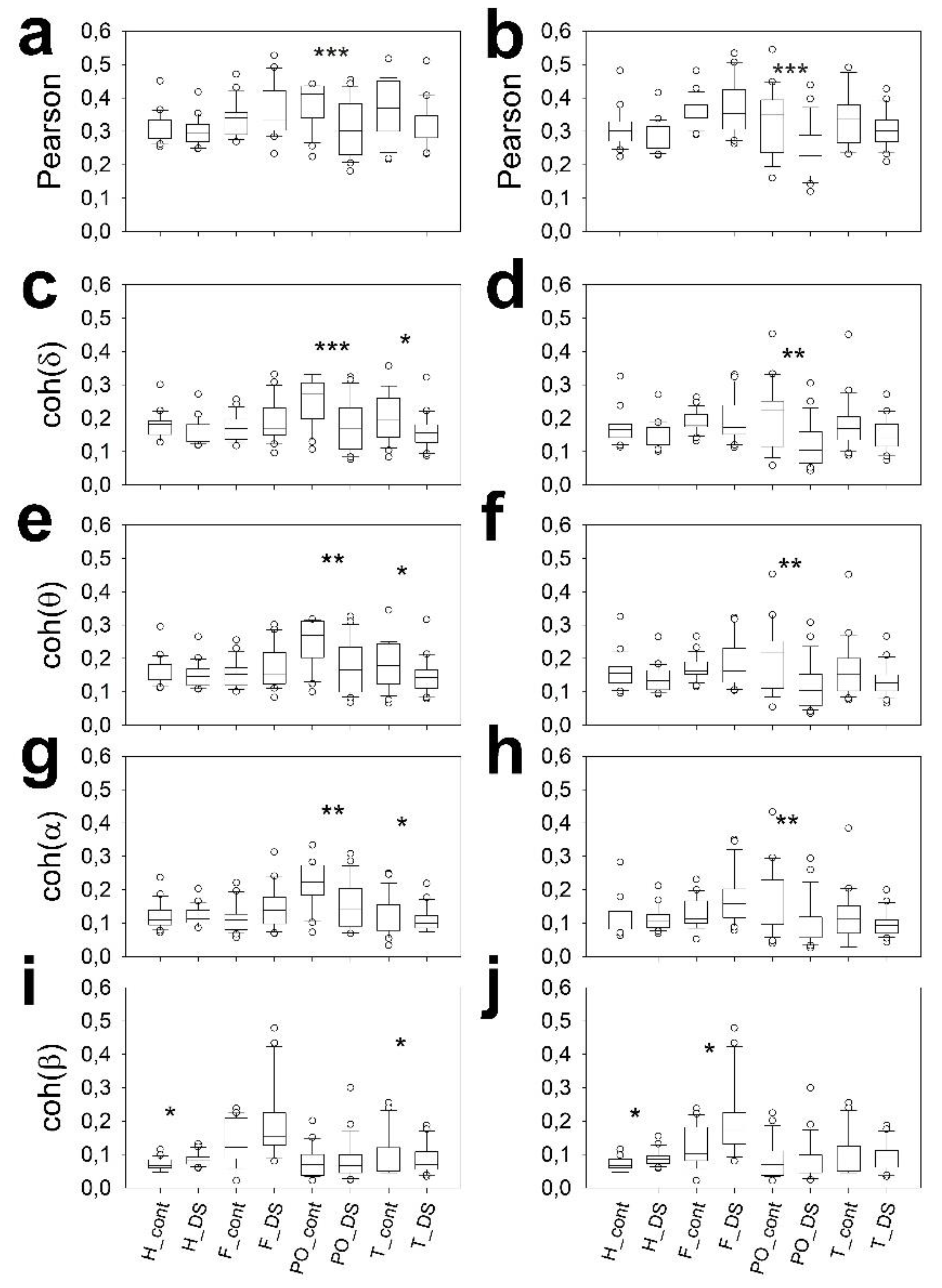

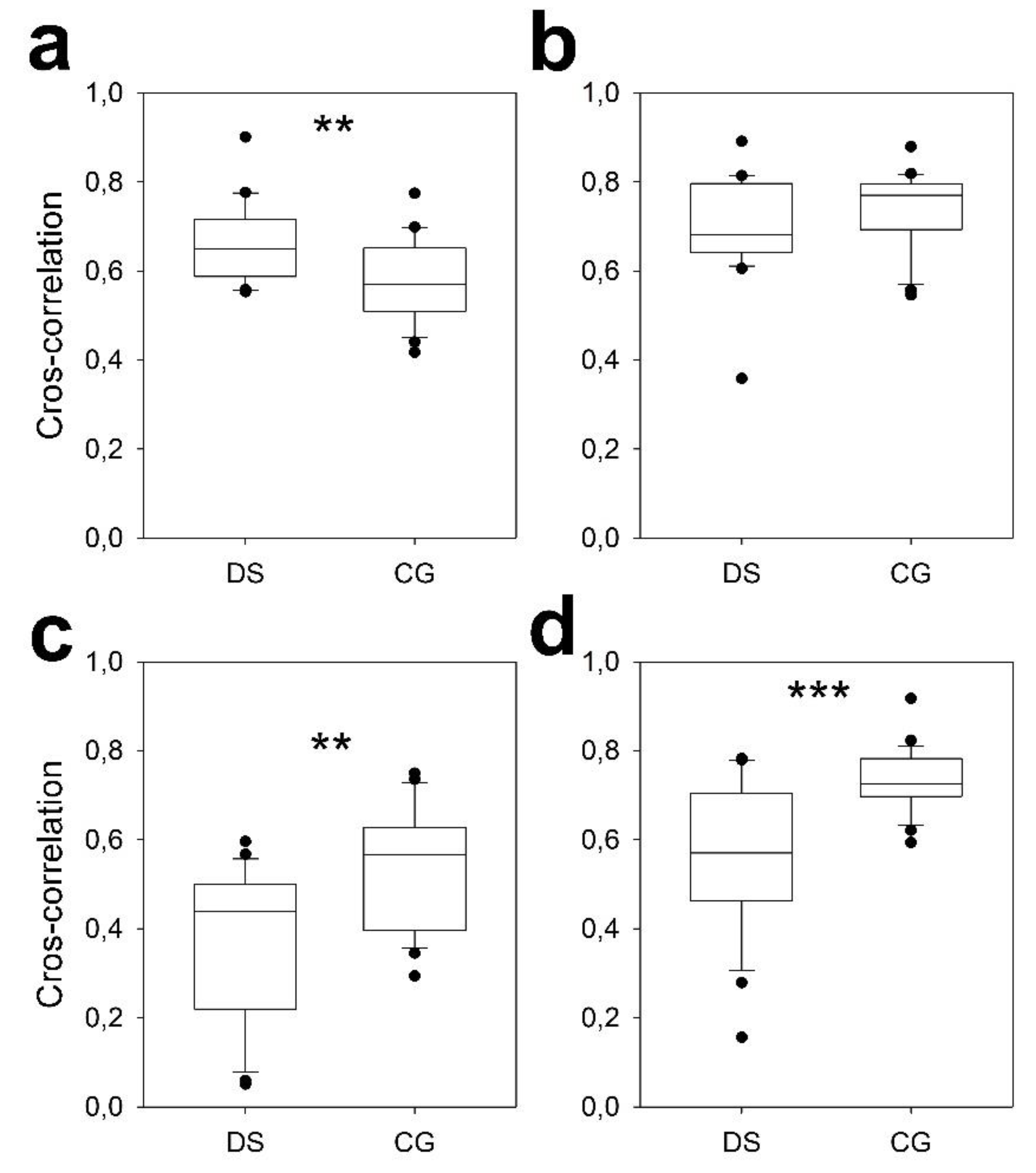

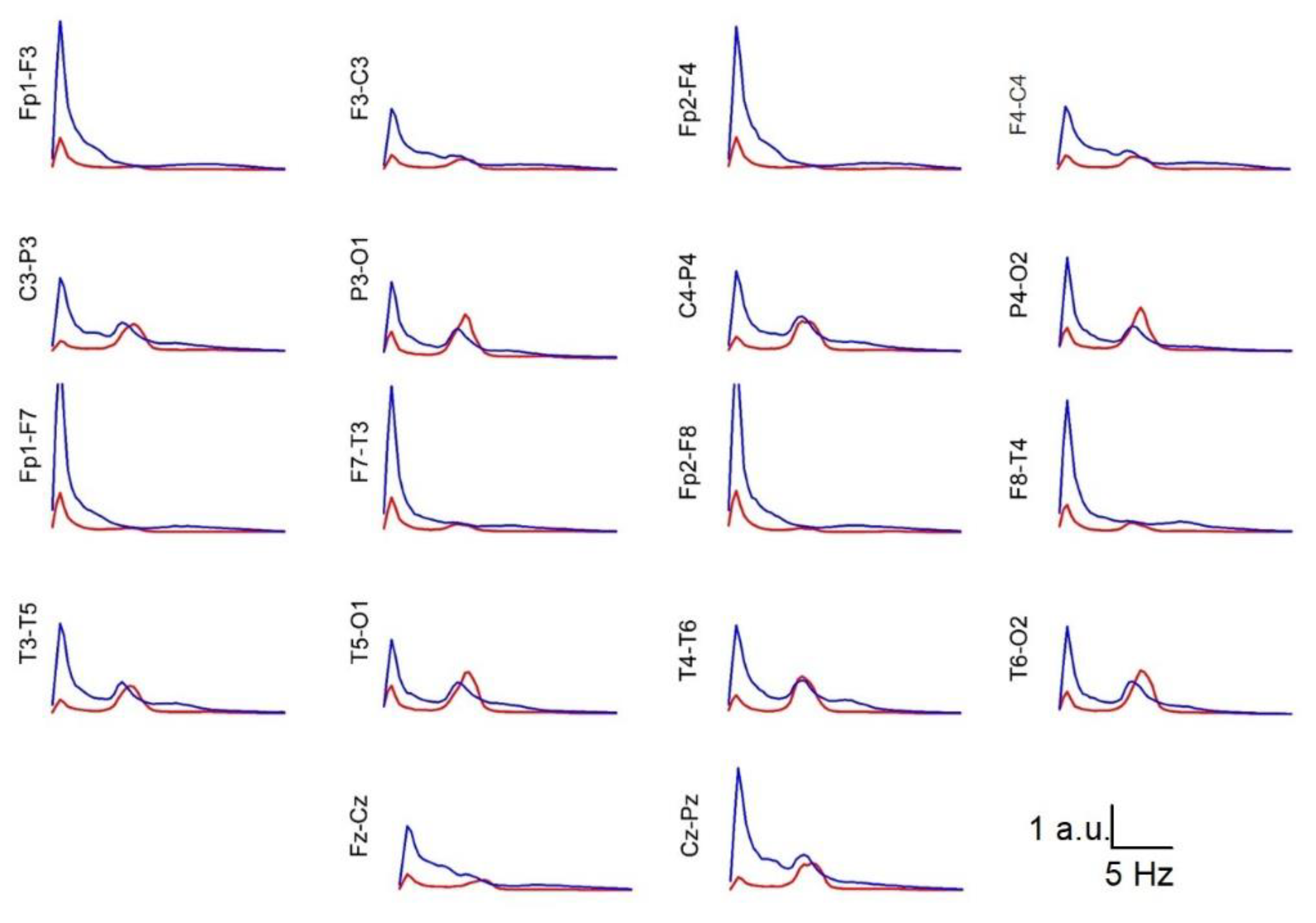

The qEEG findings of subjects with Down syndrome (DS) have not been described in the context of bipolar montage. Resting-state EEG (rsEEG) with a bipolar montage was performed in 22 young adults (26.0 ± 1.2 years) with DS but without psychiatric or neurological pathology and matched control subjects of the same sex and age, and the results were conventionally and numerically analysed. Channels were grouped into frontal, parieto-occipital, and temporal lobes. For every channel, the power spectrum was calculated and used to compute the area for the delta, theta, alpha and beta bands and was log-transformed. Shannon’s spectral entropy (SSE) and coherence by bands were computed. Finally, we also calculated the peak frequency distribution of the alpha band. qEEG revealed alterations in the rsEEG that were not detected visually. Subjects with DS showed a significant generalized increase in the power of the delta and theta bands, along with a decrease in the power of the alpha band in the posterior half of the scalp. This alpha activity also exhibited features corresponding to older euploid subjects, showing interhemispheric asynchrony in one-third of the individuals. The beta band power was significantly increased in the frontal lobes and adjacent regions, such as the parietal and mid-temporal regions. Individuals with DS showed a generalized decrease in parieto-occipital synchronization. Left temporal synchronization was also lower. The synchronization of specific channel pairs was greater in subjects with DS in the frontal lobe and much lower in the occipital and temporal regions. These results indicate that alterations in band structure and synchronization in subjects with DS are highly specific and can aid in the clinical evaluation of these individuals.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. EEG Recording and Analysis

2.3. Statistics

3. Results

3.1. Comparison by Sex

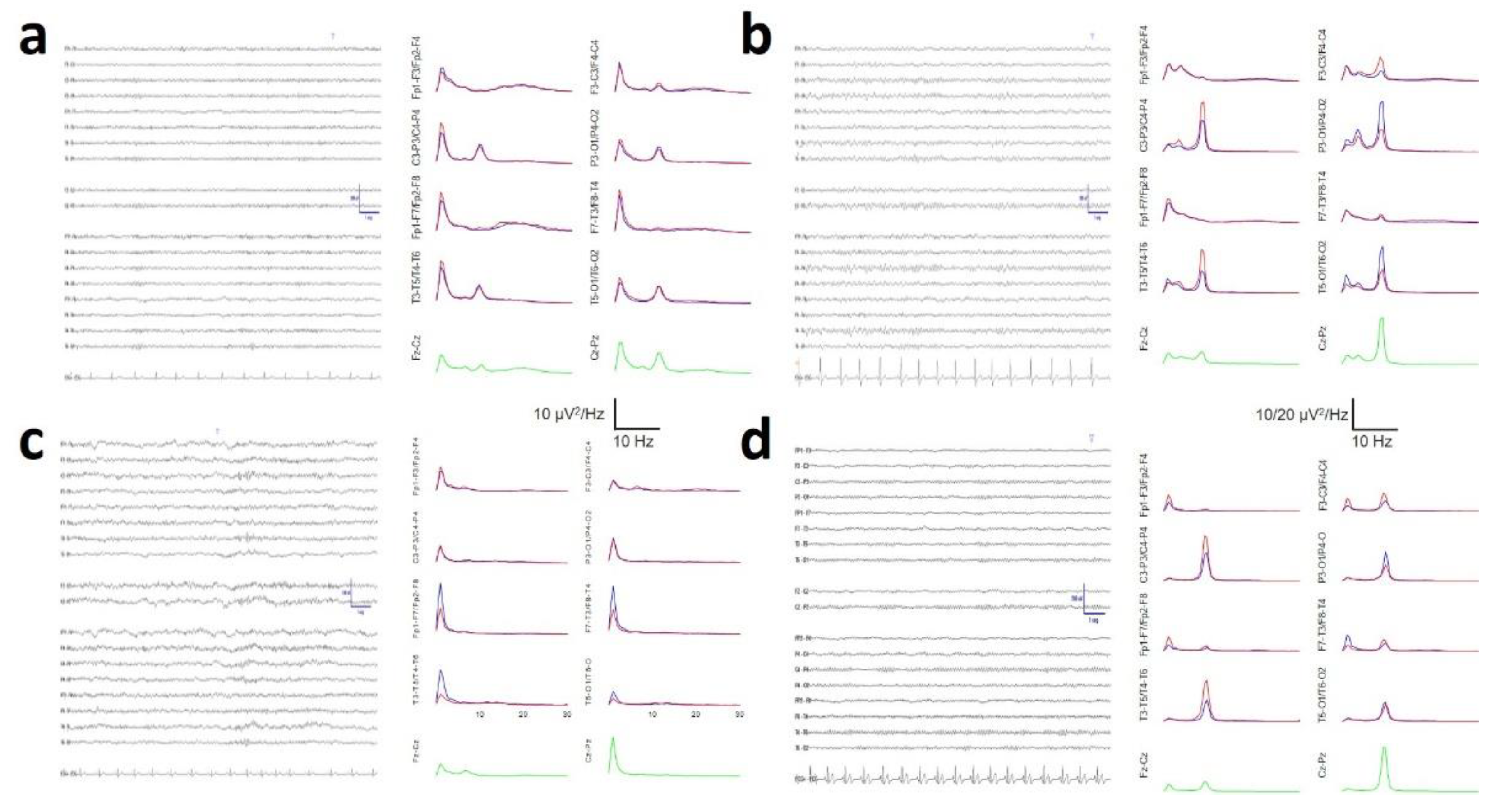

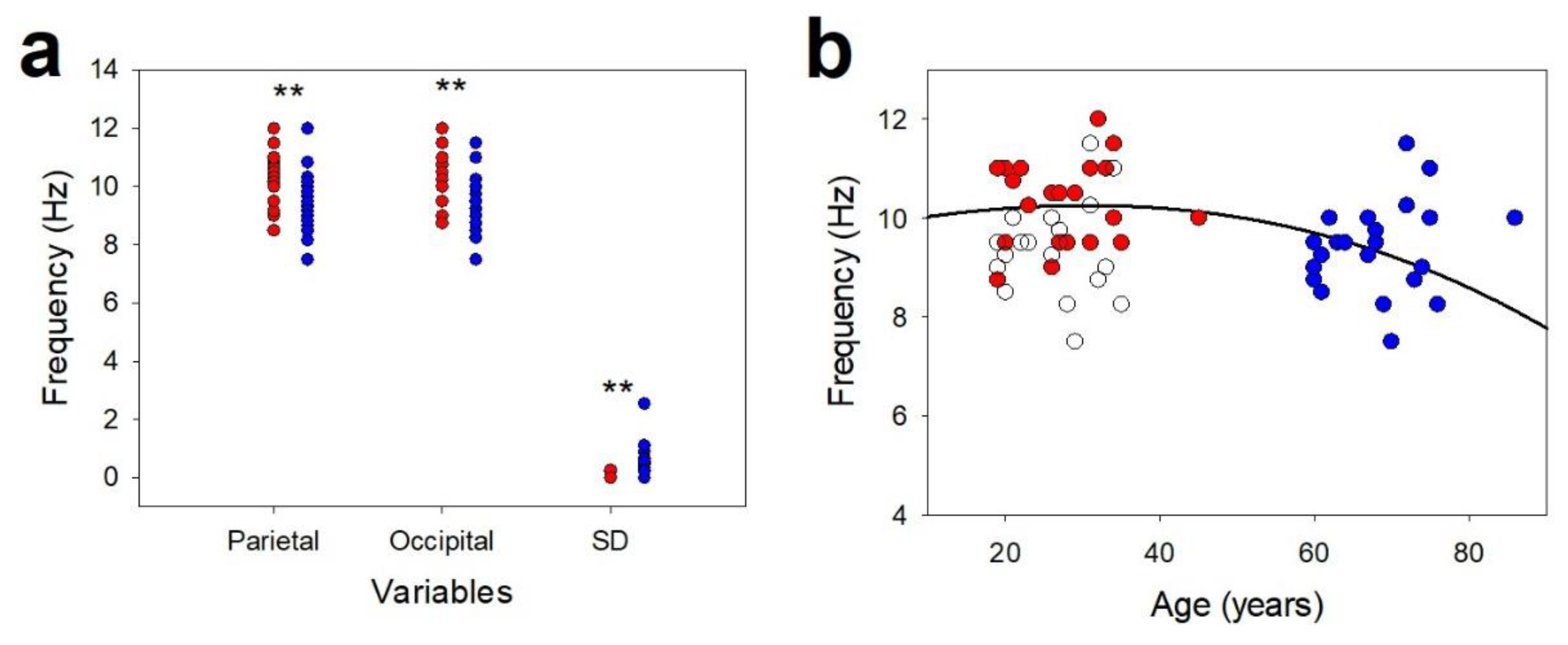

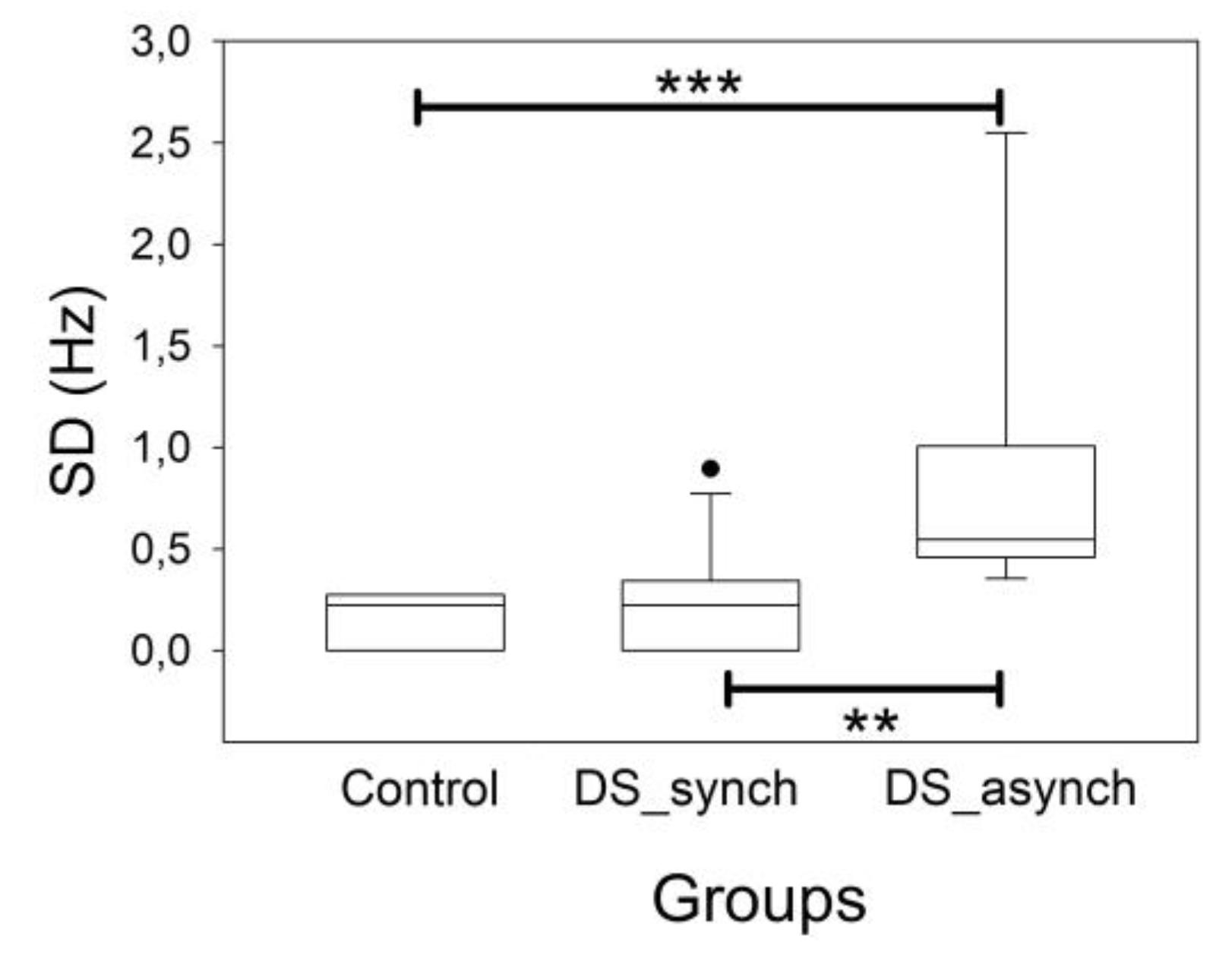

3.2. Posterior Dominant Rhythm and Alpha Band

3.3. Bands Structure

3.4. Scalp Synchronization

3.5. Average Spectra

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| alphao | Average alpha band at occipital lobe |

| alphap | Average alpha band at parietal lobe |

| CC | Cross-correlation |

| CG | Control Group |

| coh | Coherence |

| DS | Down syndrome |

| F | Frontal lobe |

| FFT | Fast Fourier Transform |

| H | Hemisphere |

| ihDif | Interhemispheric difference |

| IQ | Intelligence quotient |

| logPS | Logarithm transform of PS |

| Difference between the Cz-Pz channel and P3-O1 | |

| Difference between the Cz-Pz channel and P4-O2 | |

| O | Occipital lobe |

| PDR | Posterior Dominant Rhythm of the DS/CG |

| pPS | Peak Frequency of power spectrum at alpha band |

| P | Parietal lobe |

| PO | Parieto-occipital lobe |

| PS | Power Spectrum |

| rsEEG | Resting state EEG |

| SD | Standard deviation for the parieto-occipital channels |

| SSE | Shannon’s spectral entropy |

| T | Temporal lobe |

References

- Sherman, S.L.; Allen, E.G.; Bean, L.H.; Freeman, S.B. Epidemiology of Down syndrome. Ment. Retard. Dev. Disabil. Res. Rev. 2007, 13, 221–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hart, SJ; Visootsak, J; Tamburri, P; Phuong, P; Baumer, N; Hernandez, MC; Skotko, BG; Ochoa-Lubinoff, C; Liogier D’Ardhuy, X; Kishnani, PS; Spiridigliozzi, GA. Pharmacological interventions to improve cognition and adaptive functioning in Down syndrome: Strides to date. Am J Med Genet A 2017, 173(11), 3029–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livingstone, N; Hanratty, J; McShane, R; Macdonald, G. Pharmacological interventions for cognitive decline in people with Down syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015, 2015(10), Cd011546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lott, I.T.; Dierssen, M. Cognitive deficits and associated neurological complications in individuals with Down’s syndrome. Lancet Neurol. 2010, 9, 623–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasina, Z.; Wang, N.; Wang, C.C. Developmental Neuropathology and Neurodegeneration of Down Syndrome: Current Knowledge in Humans. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 877711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastor, J; Vega-Zelaya, L; Martin-Abad, E. Necessity of quantitative EEG in daily clinical practice. In Electroencephalography; Nakano, Hideki, Ed.; InTech, 2021; ISBN 978-1-83968-289-6. [Google Scholar]

- Fingelkurts, AA; Fingelkurts, AA. Quantitative Electroencephalogram (qEEG) as a Natural and Non-Invasive Window into Living Brain and Mind in the Functional Continuum of Healthy and Pathological Conditions. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 9560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chmiel, J.; Rybakowski, F.; Leszek, J. EEG in Down Syndrome. A Review and Insights into Potential Neural Mechanisms. Brain Sci. 2024, 14, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortea, J.; Zaman, S.H.; Hartley, S.; Rafii, M.S.; Head, E.; Carmona-Iragui, M. Alzheimer’s disease associated with Down syndrome: genetic form of dementia. Lancet Neurol. 2021, 20, 930–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, E.R. The neurophysics of consciousness. Brain Res. Rev. 2002, 39, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastor, J. Introduction to Electroencephalography. In Quantitative EEG Practical Guide; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastor, J; Vega-Zelaya, L. Normative Structure of Resting-State EEG in Bipolar Derivations for Daily Clinical Practice: A Pilot Study. Brain Sci. 2023, 13, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastor, J. Measurements of Synchronization. In Quantitative EEG Practical Guide; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadlou, M; Gharib, M; Hemmati, S; Vameghi, R; Sajedi, F. Disrupted small-world brain network in children with Down Syndrome. Clin Neurophysiol 2013, 124(9), 1755–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmid, RG; Tirsch, WS; Rappelsberger, P; Weinmann, H-M; Poppl, SJ. Comparative coherence studies in healthy volunteers and Down’s syndrome patients from childhood to adult age. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol 1992, 83, 112–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babiloni, C; Albertini, G; Onorati, P; Vecchio, F; Buffo, P; Sarà, M; Condoluci, C; Pistoia, F; Carducci, F; Rossini, PM. Inter-hemispheric functional coupling of eyes-closed resting EEG rhythms in adolescents with Down syndrome. Clin Neurophysiol 2009, 120(9), 1619–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pastor, J; Vega-Zelaya, L; Martin, AE. Specific EEG encephalopathic pattern in SARS-CoV-2 patients. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 91, 545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastor, J. A Proposal for an Analytic System: CRANE. In Quantitative EEG Practical Guide; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 65–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smulders, F.T.Y.; Oever, S.T.; Donkers, F.C.L.; Quaedflieg, C.W.E.M.; van de Ven, V. Single-trial log transformation is optimal in frequency analysis of resting EEG alpha. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2018, 48, 2585–2598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, V; Chang, BS; Schomer, DL. Normal EEG in wakefulness and sleep: adults and elederly. In Niedermeyer’s Electroencephalography: basic principles, clinical applications and related fields, 7th ed.; Shomer, DL, Lopes da Silva, F, Eds.; Oxford University Press, 2018; ISBN 9780190228484. 49. [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch, LJ; Fong, MWK; Leitinger, M; LaRoche, SM; Beniczky, S; Abend, NS; Lee, JW; Wusthoff, CJ; Hahn, CD; Westover, MB; Gerard, EE; Herman, ST; Haider, HA; Osman, G; Rodriguez-Ruiz, A; Maciel, CB; Gilmore, EJ; Fernandez, A; Rosenthal, ES; Claassen, J; Husain, AM; Yoo, JY; So, EL; Kaplan, PW; Nuwer, MR; van Putten, M; Sutter, R; Drislane, FW; Trinka, E; Gaspard, N. American Clinical Neurophysiology Society’s Standardized Critical Care EEG Terminology: 2021 Version. J Clin Neurophysiol 2021, 38(1), 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Devinsky, O.; Sato, S.; Conwit, R.A.; Schapiro, M.B. Relation of EEG alpha background to cognitive function, brain atrophy, and cerebral metabolism in Down’s syndrome: Age-specific changes. Arch. Neurol. 1990, 47, 58–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partanen, J.; Soininen, H.; Könönen, M.; Kilpeläinen, R.; Helkala, E.L.; Sr, P.R. EEG reactivity correlates with neuropsychological test scores in down’s syndrome. Acta Neurol. Scand. 1996, 94, 242–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klimesch, W. Alpha-band oscillations, attention, and controlled access to stored information. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2012, 16, 606–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadaghiani, S; Kleinschmidt, A. Brain networks and α-oscillations: Structural and functional foundations of cognitive control. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2016, 20, 805–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velikova, S.; Magnani, G.; Arcari, C.; Falautano, M.; Franceschi, M.; Comi, G.; Leocani, L. Cognitive impairment and EEG background activity in adults with Down’s syndrome: A topographic study. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2011, 32, 716–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ono, Y.; Yoshida, H.; Momotani, Y.; Yoshimasu, F.; Higashi, Y. Age-related changes in occipital alpha rhythm of adults with Down syndrome. Jpn. J. Psychiatry Neurol. 1992, 46, 659–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hindriks, R.; van Putten, M.J. Thalamo-cortical mechanisms underlying changes in amplitude and frequency of human alpha oscillations. Neuroimage 2013, 70, 150–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eckart, C.; Wo’zniak-Kwa’sniewska, A.; Herweg, N.A.; Fuentemilla, L.; Bunzeck, N. Acetylcholine modulates human working memory and subsequent familiarity based recognition via alpha oscillations. Neuroimage 2016, 137, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lörincz, M.L.; Crunelli, V.; Hughes, S.W. Cellular dynamics of cholinergically induced α (8–13 Hz) rhythms in sensory thalamic nuclei In Vitro. J. Neurosci. 2008, 28, 660–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayan, S.; Kopell, N.J. Thalamic model of awake alpha oscillations and implications for stimulus processing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 18553–18558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fodale, V.; Mafrica, F.; Caminiti, V.; Grasso, G. The cholinergic system in Down’s syndrome. J. Intellect. Disabil. 2006, 10, 261–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murata, T.; Koshino, Y.; Omori, M.; Murata, I.; Nishio, M.; Horie, T.; Kiminor, I. Quantitative EEG study on premature aging in adult down’s syndrome. Biol. Psychiatry 1994, 35, 422–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamburg, S.; Bush, D.; Strydom, A.; Startin, C.M. Comparison of resting-state EEG between adults with Down syndrome and typically developing controls. J. Neurodev. Disord. 2021, 13, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salamy, A.; Alvarez, W.; Peeke, H.V. Neurometric evaluation in Down syndrome individuals: Possible implications for dual diagnosis. Brain Dysfunct. 1990, 3, 50–57. [Google Scholar]

- Locatelli, T.; Fornara, C.; Medaglini, S.; Alberoni, M.; Franceschi, M.; Rinaldi, L.; Comola, M.; Leocani, L.; Canal, N.; Comi, G. Quantified electroencephalogram in adult patients with Down’s syndrome. Dev. Brain Dysfunct. 1996, 9, 215–223. [Google Scholar]

- Medaglini, S.; Locatelli, T.; Fornara, C.; Alberoni, M.; Comola, M.; Franceschi, M.; Comi, G. P300 and EEG mapping in Down’s syndrome. J. Psychophysiol. 1997, 11, 48–58. [Google Scholar]

- Uygun, D.S.; Basheer, R. Circuits and components of delta wave regulation. Brain Res. Bull. 2022, 188, 223–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mesbah-Oskui, R.L.; Orser, B.A.; Horner, R.L. Thalamic δ-subunit containing GABAA receptors promote electrocortical signatures of deep non-REM sleep but do not mediate the effects of etomidate at the thalamus in vivo. J. Neurosci. 2014, 34, 12253–12266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartesaghi, R. Brain circuit pathology in Down syndrome: From neurons to neural networks. Rev. Neurosci. 2022, 34, 365–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contestabile, A.; Magara, S.; Cancedda, L. The GABAergic Hypothesis for Cognitive Disabilities in Down Syndrome. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2017, 11, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, J.A.; Haydar, T.F. Neurodevelopment in Down syndrome: Concordance in humans and models. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 941855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuñez, A.; Buño, W. The Theta Rhythm of the Hippocampus: From Neuronal and Circuit Mechanisms to Behavior. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 649262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalczyk, T.; Bocian, R.; Konopacki, J. The generation of theta rhythm in hippocampal formation maintained in vitro. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2013, 37, 679–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalczyk, T.; Caban, B.; Bocian, R. Theta rhythm recorded in the hippocampal formation in vitro. Postepy Hig. Med. Dosw 2013, 15, 617–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klimesch, W. EEG alpha and theta oscillations reflect cognitive and memory performance: A review and analysis. Brain Res. Rev. 1999, 29, 169–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grieco, J.; Pulsifer, M.; Seligsohn, K.; Skotko, B.; Schwartz, A. Down syndrome: Cognitive and behavioral functioning across the lifespan. Am. J. Med. Genet. C Semin. Med. Genet. 2015, 169, 135–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babiloni, C.; Albertini, G.; Onorati, P.; Muratori, C.; Buffo, P.; Condoluci, C.; Sarà, M.; Pistoia, F.; Vecchio, F.; Rossini, P.M. Cortical sources of EEG rhythms are abnormal in down syndrome. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2010, 121, 1205–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soininen, H.; Partanen, J.; Jousma, V.; Helkala, E.L.; Vanhanen, M.; Majuri, S.; Kaski, M.; Hartikainen, P.; Riekkinen, P., Sr. Age related cognitive decline and electroencephalogram slowing in down’s syndrome as a model of Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroscience 1993, 53, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, R.G.; Sadowsky, K.; Weinmann, H.M.; Tirsch, W.S.; Poppl, S.J. Z-transformed EEG power spectra of children with down syndrome vs a control group. Neuropediatrics 1985, 16, 218–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X; Li, M; Xie, J; Chen, D; Geng, X; Sun, S; Liu, B; Wang, M. Beta band modulation by dopamine D2 receptors in the primary motor cortex and pedunculopontine nucleus in a rat model of Parkinson’s disease. Brain Res Bull.;Epub 2022, 181, 121–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, R.; Herrojo Ruiz, M.; Kilavik, B.E.; Lundqvist, M.; Starr, P.A.; Aron, A.R. Beta Oscillations inWorking Memory, Executive Control of Movement and Thought, and Sensorimotor Function. J. Neurosci. 2019, 39, 8231–8238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attar, E.T. Review of electroencephalography signals approaches for mental stress assessment. Neurosciences 2022, 27, 209–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azabou, E.; Navarro, V.; Kubis, N.; Gavaret, M.; Heming, N.; Cariou, A. Value and mechanisms of EEG reactivity in the prognosis of patients with impaired consciousness: A systematic review. Crit. Care 2018, 22, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ropohl, A; Sperling, W; Elstner, S; Tomandl, B; Reulbach, U; Kaltenhäuser, M; Kornhuber, J; Maihöfner, C. Cortical activity associated with auditory hallucinations. Neuroreport 2004, 15(3), 523–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, R; Roth, RW; Chang, AJ; Sinha, N; Parashos, A; Davis, KA; Kuzniecky, R; Bonilha, L; Gleichgerrcht, E. EEG ictal power dynamics, function-structure associations, and epilepsy surgical outcomes. Neurology;Epub 2024, 102(12), e209451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Politoff, A.L.; Stadter, R.P.; Monson, N.; Hass, P. Cognition-related EEG abnormalities in nondemented Down syndrome subjects. Dementia 1996, 7, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabbiani, F; Cox, SJ. Power and Cross Spectra. In Mathematics for Neuroscientist; Academic Press: London, 2010; ISBN 978-0-12-374882-9. [Google Scholar]

- Fein, G.; Raz, J.; Brown, F.F.; Merrin, E.L. Common reference coherence data are confounded by power and phase effects. Electroencephalogr. Clin. Neurophysiol. 1988, 69, 581–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertrand, O.; Perrin, F.; Pernier, J. A theoretical justification of the average reference in topographic evoked potential studies. Electroencephalogr. Clin. Neurophysiol. 1985, 62, 462–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Xin, X.; Zhu, H.; Li, F.; Xiong, H.; Zhang, T.; Lai, Y. A Comparative Study on the Dynamic EEG Center of Mass with Different References. Front. Neurosci. 2017, 11, 509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Title 1 | Men (n = 14) | Women (n = 8) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Left hemisphere | |||

| Frontal | |||

| Delta | 3.237 ± 0.124 | 3.543 ± 0.154 | 0.144 |

| Theta | 2.115 ± 0.166 | 2.374 ± 0.137 | 0.300 |

| Alpha | 1.570 ± 0.168 | 1.706 ± 0.171 | 0.577 |

| Beta | 2.244 ± 0.207 | 2.337 ± 0.183 | 0.740 |

| SSE | 4.559 ± 0.0797 | 4.551 ± 0.0624 | 0.939 |

| Parieto-occipital | |||

| Delta | 2.849 ± 0.146 | 3.337 ± 0.140 | 0.039* |

| Theta | 2.118 ± 0.232 | 2.555 ± 0.211 | 0.223 |

| Alpha | 2.488 ± 0.241 | 3.303 ± 0.443 | 0.134 |

| Beta | 2.212 ± 0.226 | 2.739 ± 0.293 | 0.174 |

| SSE | 4.608 ± 0.0976 | 4.562 ± 0.104 | 0.753 |

| Temporal | |||

| Delta | 3.122 ± 0.123 | 3.446 ± 0.199 | 0.159 |

| Theta | 2.126 ± 0.214 | 2.364 ± 0.188 | 0.172 |

| Alpha | 2.321 ± 0.233 | 2.770 ± 0.361 | 0.315 |

| Beta | 2.348 ± 0.212 | 2.622 ± 0.234 | 0.398 |

| SSE | 4.590 ± 0.0882 | 4.568 ± 0.0971 | 0.868 |

| Rigth hemisphere | |||

| Frontal | |||

| Delta | 3.293 ± 0.109 | 3.697 ± 0.147 | 0.038* |

| Theta | 2.196 ± 0.168 | 2.495 ± 0.108 | 0.225 |

| Alpha | 1.734 ± 0.170 | 1.965 ± 0.179 | 0.361 |

| Beta | 2.348 ± 0.212 | 2.622 ± 0.234 | 0.384 |

| SSE | 4.617 ± 0.0936 | 4.624 ± 0.0994 | 0.963 |

| Parieto-occipital | |||

| Delta | 2.932 ± 0.156 | 3.381 ± 0.138 | 0.068 |

| Theta | 2.114 ± 0.228 | 2.536 ± 0.242 | 0.101 |

| Alpha | 2.570 ± 0.241 | 3.318 ± 0.473 | 0.187 |

| Beta | 2.228 ± 0.201 | 2.702 ± 0.259 | 0.169 |

| SSE | 4.547 ± 0.100 | 4.527 ± 0.0859 | 0.885 |

| Temporal | |||

| Delta | 3.211 ± 0.134 | 3.533 ± 0.231 | 0.209 |

| Theta | 2.210 ± 0.238 | 2.491 ± 0.219 | 0.219 |

| Alpha | 2.465 ± 0.231 | 3.046 ± 0.411 | 0.242 |

| Beta | 2.428 ± 0.208 | 2.838 ± 0.243 | 0.219 |

| SSE | 4.564 ± 0.0776 | 4.617 ± 0.113 | 0.701 |

| Variable | Control | DS | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Count | Range | Count | Range | |

| ihDif | 3 | -0.5, 0.5 | 8 | -2.5, 1.5 |

| 10 | -0.5, 0.5 | 10 | -1.0, 1.0 | |

| 13 | -0.5, 0.5 | 10 | -2.5, 1.5 | |

| Lobe | Synchronous (n = 14) |

Asynchronous (n = 8) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Left hemisphere | |||

| Frontal | |||

| Delta | 3.401 ± 0.138 | 3.254 ± 0.137 | 0.492 |

| Theta | 2.235 ± 0.149 | 2.164 ± 0.204 | 0.778 |

| Alpha | 1.802 ± 0.161 | 1.301 ± 0.125 | 0.0449* |

| Beta | 2.333 ± 0.172 | 2.181 ± 0.275 | 0.626 |

| SSE | 4.548± 0.0792 | 4.5751 ± 0.0624 | 0.841 |

| Parieto-occipital | |||

| Delta | 3.079 ± 0.175 | 2.935 ± 0.0941 | 0.563 |

| Theta | 2.351 ± 0.222 | 2.148 ± 0.269 | 0.576 |

| Alpha | 3.112 ± 0.321 | 2.210 ± 0.193 | 0.060 |

| Beta | 2.515 ± 0.263 | 2.209 ± 0.210 | 0.436 |

| SSE | 4.546 ± 0.102 | 4.671 ± 0.0809 | 0.352 |

| Temporal | |||

| Delta | 3.291 ± 0.167 | 3.151 ± 0.0803 | 0.554 |

| Theta | 2.272 ± 0.193 | 2.110 ± 0.255 | 0.413 |

| Alpha | 2.772 ± 0.273 | 1.982 ± 0.163 | 0.022 |

| Beta | 2.538 ± 0.221 | 2.289 ± 0.210 | 0.424 |

| SSE | 4.551 ± 0.0965 | 4.636 ± 0.0623 | 0.470 |

| Rigth hemisphere | |||

| Frontal | |||

| Delta | 3.503 ± 0.125 | 3.329 ± 0.147 | 0.380 |

| Theta | 2.344 ± 0.149 | 2.236 ± 0.197 | 0.667 |

| Alpha | 2.007 ± 0.168 | 1.488 ± 0.122 | 0.044* |

| Beta | 2.587 ± 0.186 | 2.391 ± 0.307 | 0.901 |

| SSE | 4.613 ± 0.0993 | 4.631 ± 0.0792 | 0.963 |

| Parieto-occipital | |||

| Delta | 3.169 ± 0.162 | 2.967 ± 0.168 | 0.400 |

| Theta | 2.359 ± 0.216 | 2.108 ± 0.293 | 0.453 |

| Alpha | 3.131 ± 0.326 | 2.335 ± 0.246 | 0.388 |

| Beta | 2.510 ± 0.220 | 2.208 ± 0.233 | 0.169 |

| SSE | 4.517 ± 0.0852 | 4.581 ± 0.127 | 0.682 |

| Temporal | |||

| Delta | 3.389 ± 0.175 | 3.223 ± 0.139 | 0.523 |

| Theta | 2.367 ± 0.207 | 2.216 ± 0.312 | 0.539 |

| Alpha | 2.928 ± 0.291 | 2.235 ± 0.233 | 0.119 |

| Beta | 2.648 ± 0.206 | 2.454 ± 0.272 | 0.576 |

| SSE | 4.567 ± 0.0868 | 4.612 ± 0.0891 | 0.601 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).