Submitted:

03 January 2026

Posted:

05 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

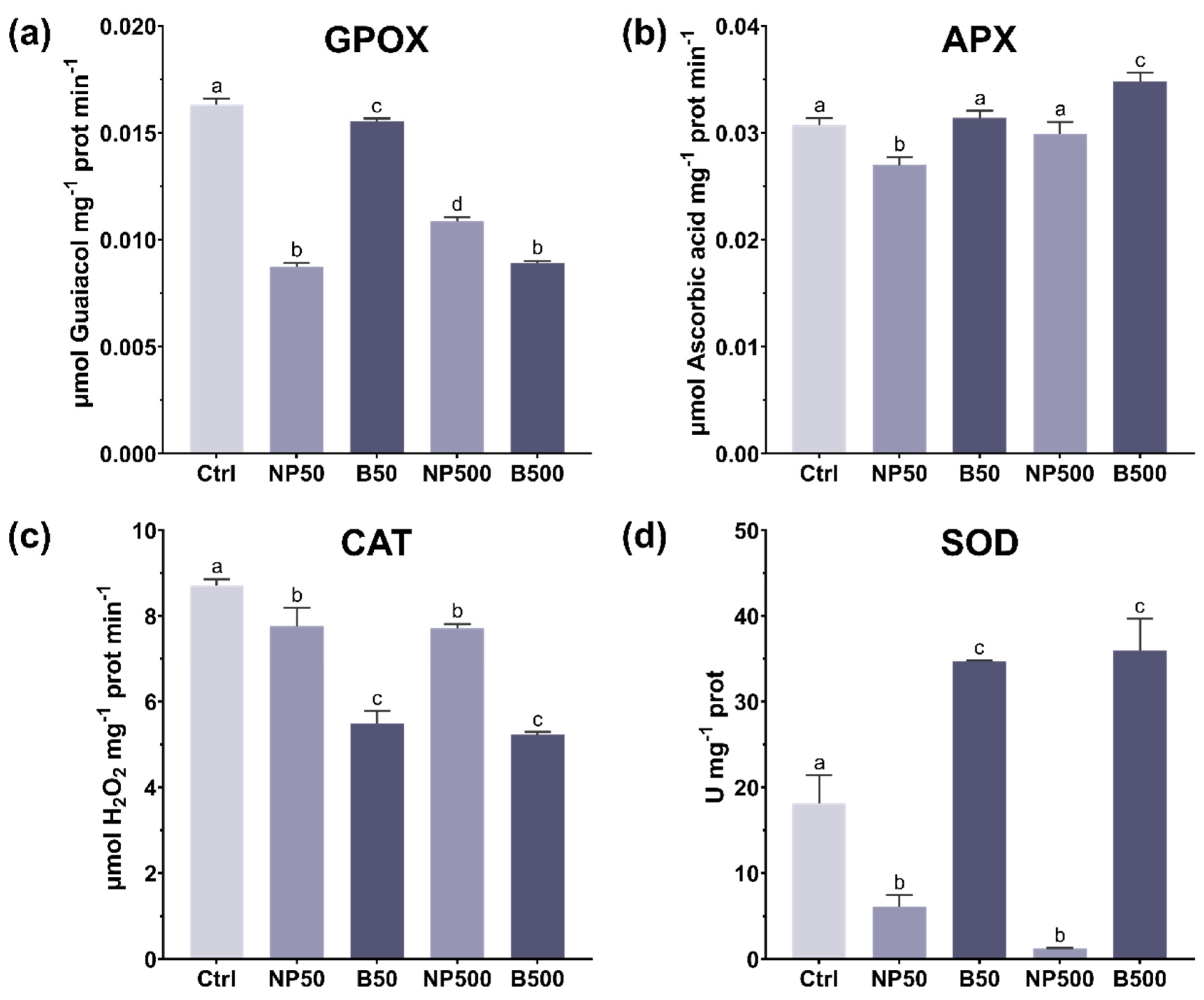

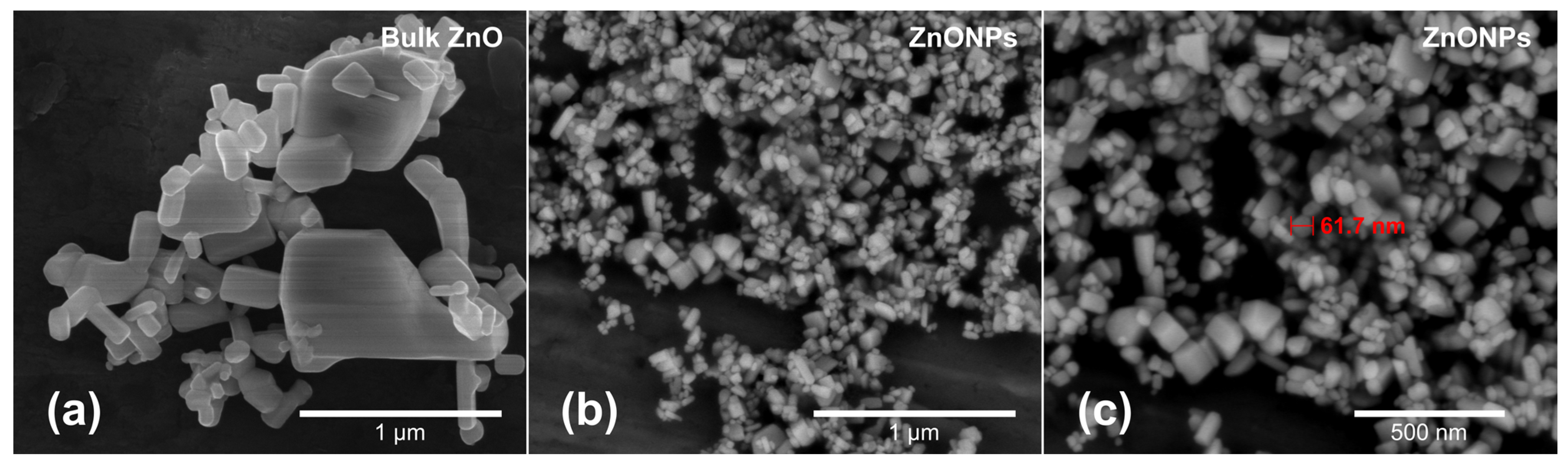

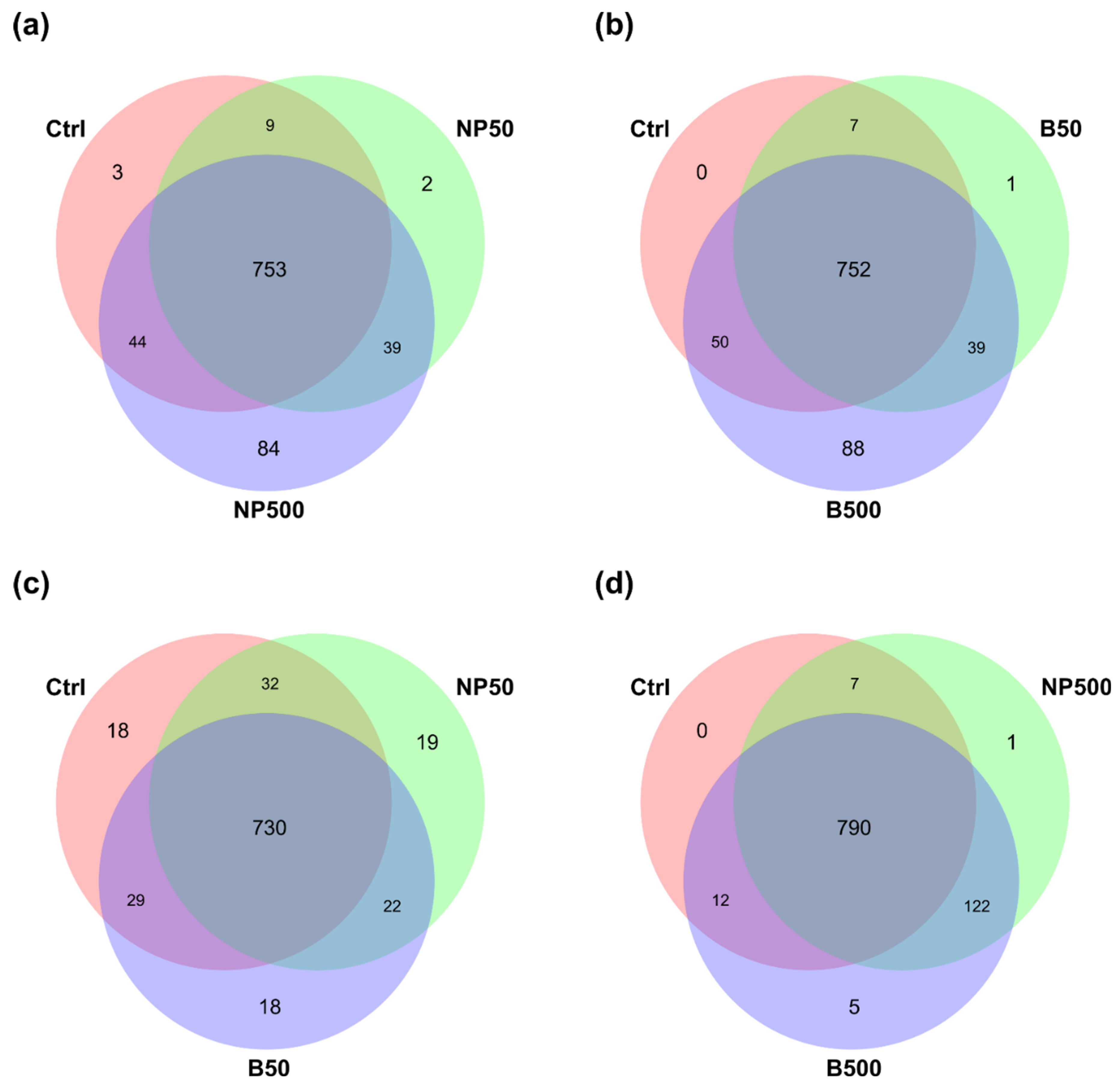

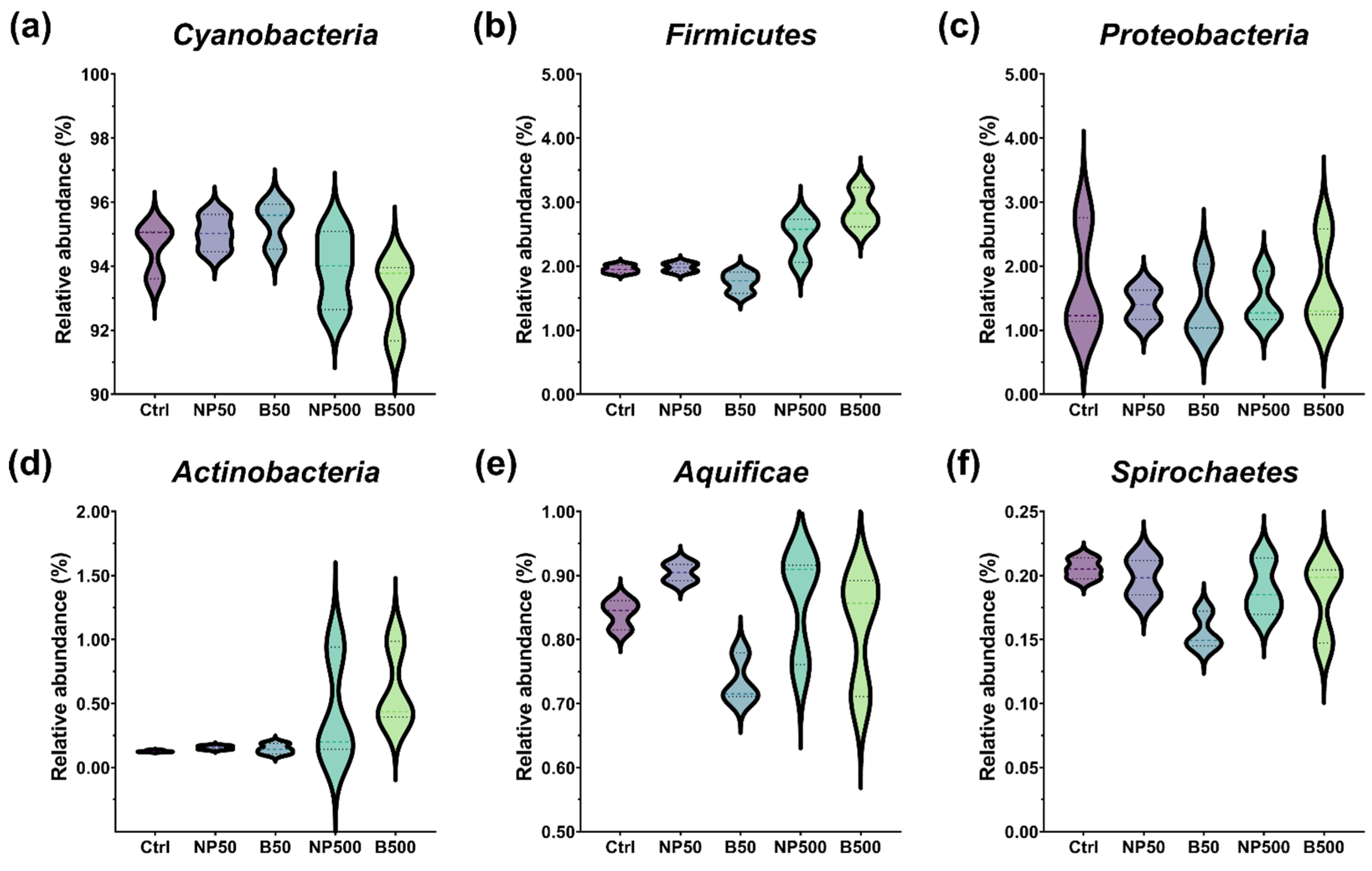

The use of zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnONPs) in agriculture has increased due to their biostimulant potential; however, their effects on plant chemical communication and associated microbial communities are still poorly understood. This study presents a multi-perspective analysis contrasting the effects of ZnONPs with those of conventional ZnO (Bulk) on Capsicum annuum seedlings grown in a substrate with concentrations of 50 and 500 mg kg⁻¹. The results reveal that, at high doses, the bulk material (B500) generated a higher foliar accumulation of zinc (128.7 mg kg⁻¹) than ZnONPs (NP500, 119.7 mg kg⁻¹), a phenomenon attributed to the agglomeration of nanoparticles in the soil matrix, which limits their root absorption. At the physiological level, a critical divergence was observed: while bulk ZnO stimulated the activity of the enzyme superoxide dismutase (SOD), ZnONPs caused severe inhibition of the same (93% reduction), compromising the enzymatic antioxidant machinery and forcing the plant to rely on non-enzymatic mechanisms, such as an increase in total phenols. The volatilomic profile revealed a specific metabolic disturbance induced by ZnONPs in the green leaf volatiles (GLV) pathway. A significant accumulation of hexanal and suppression of hexanol and hexyl acetate were detected, suggesting that the nanomaterial inhibited alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH). In addition, ZnONPs suppressed the emission of methyl salicylate (MeSA)—a key messenger in acquired systemic resistance—whereas the Bulk treatment increased its abundance to 41.7%. Finally, metagenomic analysis indicated that zinc stress restructured the phyllosphere microbiota, promoting the proliferation of Actinobacteria and eliminating sensitive taxa such as Spirochaetes. Taken together, these findings demonstrate that ZnONPs act as multifactorial stressors that not only alter internal metabolism but also silence chemical communication and remodel plant ecology.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Nanoparticle Characterization

2.2. Experimental Design and Growth Conditions

2.3. Sample Processing and Preservation

2.4. Zinc Quantification in Plant Tissues

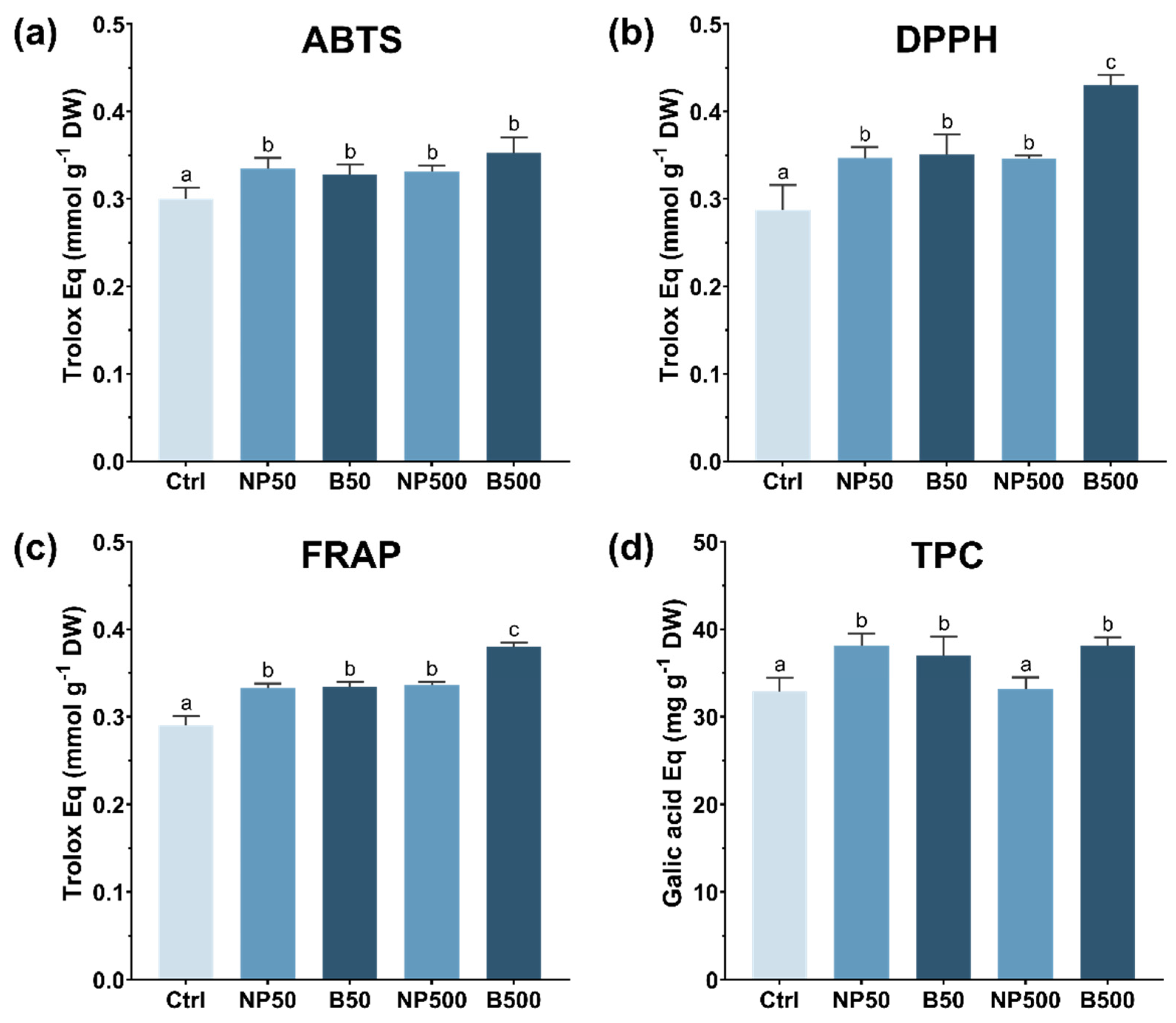

2.5. Non-Enzymatic Antioxidant Activity and Total Polyphenols

2.5.1. ABTS Assay

2.5.2. DPPH Assay

2.5.3. FRAP Assay

2.5.4. Total Polyphenol Content

2.6. Antioxidant Enzyme Activity

2.6.1. Protein Quantification

2.6.2. Guaiacol Peroxidase (GPOX)

2.6.3. Ascorbate Peroxidase (APX)

2.6.4. Catalase (CAT)

2.6.5. Superoxide Dismutase (SOD)

2.7. Volatile Organic Compound (VOC) Analysis

2.8. Phyllosphere Microbiome Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Material Characterization

3.2. Bioaccumulation

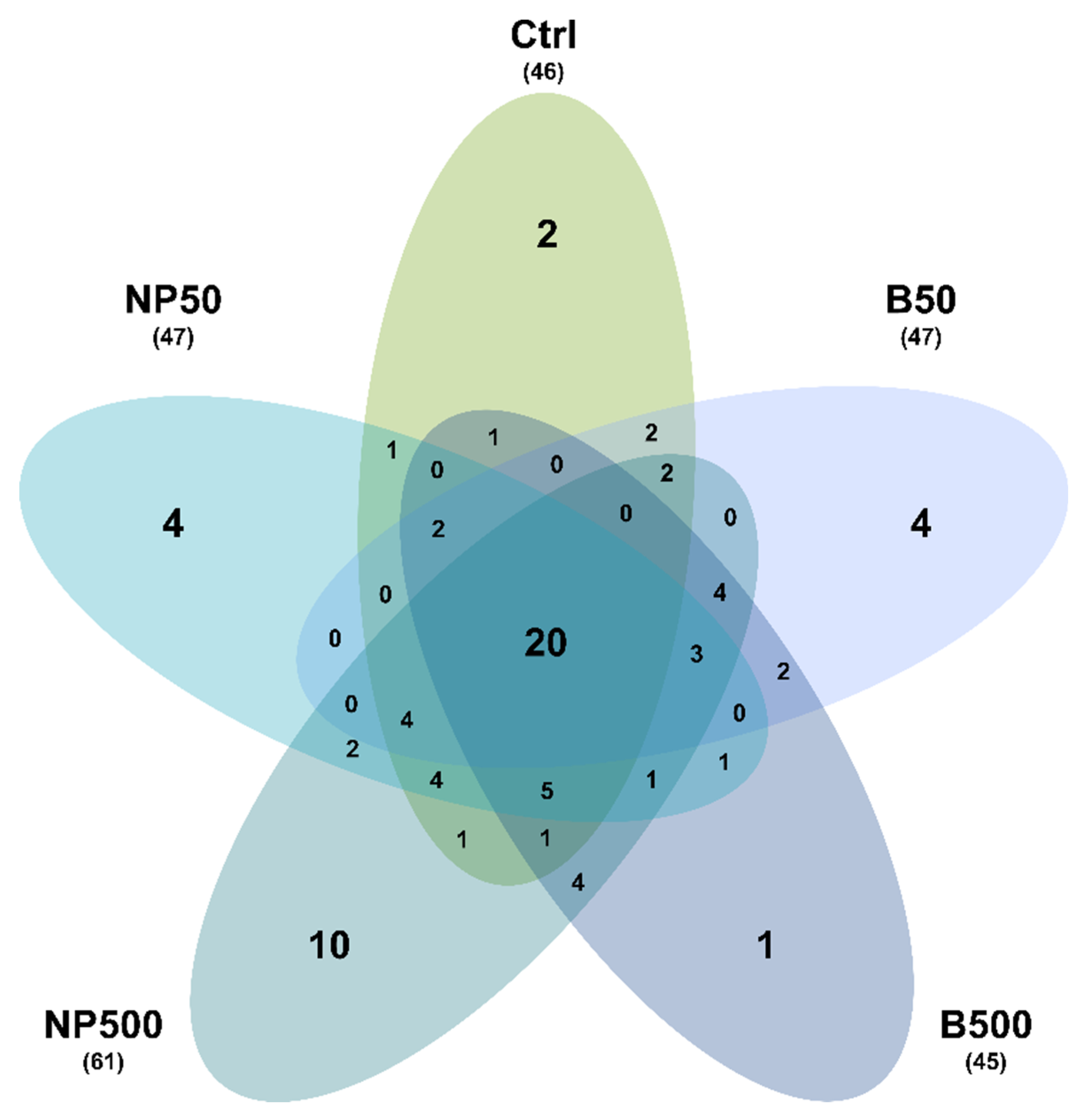

3.3. Bacterial Community of the Capsicum annuum Phyllosphere

3.4. Metabolic Activities

3.4.1. Antioxidants

3.4.2. Antioxidant Enzymes

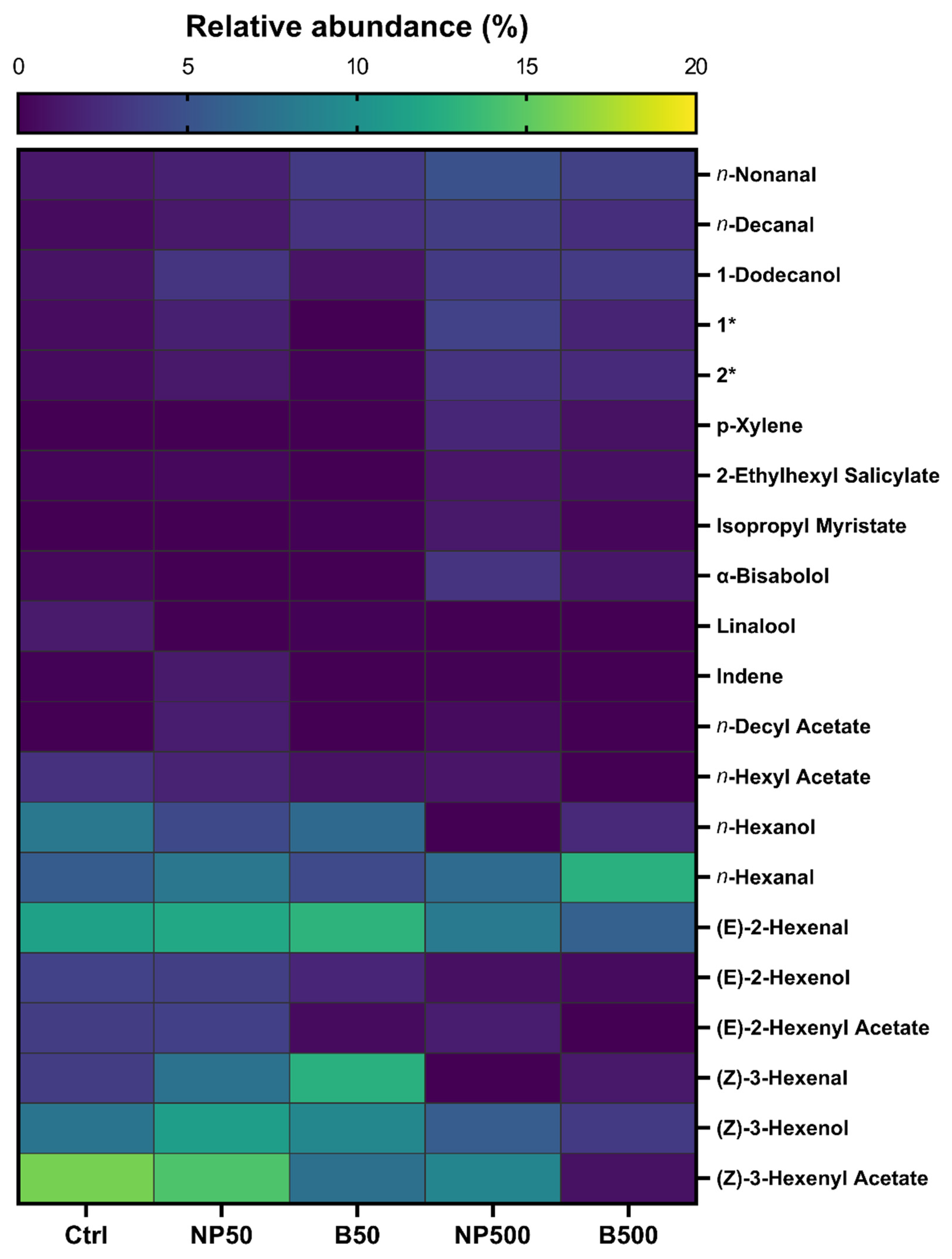

3.5. Volatiles Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Díaz-Parra, DG; García-Casillas, LA; Velasco-Ramírez, SF; Guevara-Martínez, SJ; Zamudio-Ojeda, A; Zuñiga-Mayo, VM; et al. Role of Metal-Based Nanoparticles in Capsicum spp. Plants. ACS Omega 2025, 10(11), 10756–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. FAOSTAT – Production: Crops and livestock products (Chillies and peppers) [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2025 Sept 10]. Available online: https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QCL.

- Liu, F; Zhao, J; Sun, H; Xiong, C; Sun, X; Wang, X; et al. Genomes of cultivated and wild Capsicum species provide insights into pepper domestication and population differentiation. Nature Communications 2023, 14(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carrizo García, C; Barfuss, MHJ; Sehr, EM; Barboza, GE; Samuel, R; Moscone, EA; et al. Phylogenetic relationships, diversification and expansion of chili peppers (Capsicum, Solanaceae). Annals of Botany 2016, 118(1), 35–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batiha, GE saber; Alqahtani, A; Ojo, OA; Shaheen, HM; Wasef, L; Elzeiny, M; et al. Biological Properties, Bioactive Constituents, and Pharmacokinetics of Some Capsicum spp. and Capsaicinoids. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2020, 21, 5179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Pérez, T; Gómez-García, M; del, R; Valverde, ME; Paredes-López, O. Capsicum annuum (hot pepper): An ancient Latin-American crop with outstanding bioactive compounds and nutraceutical potential. A review. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety 2020, 19(6), 2972–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zemanov, V; Pavl, D; Nov, M; Hniliˇ, F. The Dual Role of Zinc in Spinach Metabolism : Beneficial × Toxic. Plants 2024, 13, 3363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzel, A; Sertan, D; Oskay, Ç; Ersan, K; Ayşegül, T; Rıza, Y. Effects of green and chemically synthesized ZnO nanoparticles on Capsicum annuum under drought stress. Acta Physiologiae Plantarum 2025, 47(2), 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, AR; Xingming, A; Zaid, F; Abdul, U; Muhammad, S; Yihua, A. Efficacy of zinc - based nanoparticles in alleviating the abiotic stress in plants : current knowledge and future perspectives. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2023, 30, 110047–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravishankar, TN; Ananda, A; Shilpa, BM; Adarsh, J. Eco-friendly synthesis of NiO and Ag / NiO nanoparticles : applications in photocatalytic and antibacterial activities. Royal Society Open Science 2025, 12, 241733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-López, JI; Lira-saldivar, RH; Zavala, - F; Olivares-sáenz, E; Niño-medina, G; Ruiz, - NA; et al. Effects of zinc oxide nanoparticles on growth and antioxidant enzymes of Capsicum chinense. Toxicological & Environmental Chemistry [Internet] Available from. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-López, JI; Zavala-Garcia, F; Olivares-Saénz, E; Lira-Saldivar, RH; Barriga-Castro, ED; Ruiz-Torres, NA; et al. Zinc Oxide nanoparticles boosts phenolic compounds and antioxidant activity of capsicum annuum l. during germination. Agronomy 2018, 8(10), 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-López, JI; Niño-Medina, G; Olivares-Sáenz, E; Lira-Saldivar, RH; Barriga-Castro, ED; Vázquez-Alvarado, R; et al. Foliar Application of Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles and Zinc Sulfate Boosts the Content of Bioactive Compounds in Habanero Peppers. Plants 2019, Vol 8 8(8), 254. [Google Scholar]

- Dileep Kumar, G; Raja, K; Natarajan, N; Govindaraju, K; Subramanian, KS. Invigouration treatment of metal and metal oxide nanoparticles for improving the seed quality of aged chilli seeds (Capsicum annum L.). Materials Chemistry and Physics 2020, 242, 122492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younes, NA; Hassan, HS; Elkady, MF; Hamed, AM; Dawood, MFA. Impact of synthesized metal oxide nanomaterials on seedlings production of three Solanaceae crops. Heliyon 2020, 6, e03188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghareeb, RY; Belal, EB; El-Khateeb, NMM; Shreef, BA. Utilizing bio-synthesis of nanomaterials as biological agents for controlling soil-borne diseases in pepper plants: root-knot nematodes and root rot fungus. BMC Plant Biology 2024, 24, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, R; Pratap, S; Fedor, S; Aleksey, I; Maksimov, Y; Latsynnik, E. Trichoderma -Mediated Synthesis of ZnONPs : Trend Efficient for Repressing Two Seed- and Soil-Borne Phytopathogens Phomopsis vexans and Colletotrichum capsici. BioNanoScience 2024, 14, 5363–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivero-montejo, SDJ; Rivera-bustamante, RF; Saavedra-trejo, DL; Vargas-hernandez, M; Palos-barba, V; Macias-bobadilla, I; et al. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry Inhibition of pepper huasteco yellow veins virus by foliar application of ZnO nanoparticles in Capsicum annuu m L. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry 2023, 203, 108474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasouli, F; Asadi, M; Hassanpouraghdam, MB; Aazami, MA; Ebrahimzadeh, A; Kakaei, K; et al. Foliar Application of ZnO-NPs Influences Chlorophyll Fluorescence and Antioxidants Pool in Capsicum annum L. under Salinity. Horticulturae 2022, 8(10), 908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karmous, I; Gammoudi, N; Chaoui, A. Assessing the Potential Role of Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles for Mitigating Cadmium Toxicity in Capsicum annuum L. Under In Vitro Conditions. Journal of Plant Growth Regulation 2023, 42(2), 719–34. [Google Scholar]

- Irfan, SM; Bhatti, KH. Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles Mitigate Toxic Effects of Cadmium Heavy Metal in Chilli (Capsicum annuum L.). Proceedings of the Pakistan Academy of Sciences: Part B 2023, 60(3), 477–87. [Google Scholar]

- Matsui, K; Engelberth, J. Green Leaf Volatiles — The Forefront of Plant Responses Against Biotic Attack Special Issue – Review. Plant and Cell Physiology 2022, 63(10), 1378–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpraga, M; Takabayashi, J; Holopainen, JK. Language of plants : Where is the word? Journal of integrative plant biology 2016, 58(4), 343–9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Engelberth, J. Primed to grow : a new role for green leaf volatiles in plant stress responses. Plant Signaling & Behavior 2020, 15(1), e1701240. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y; Jiang, J; Wang, Y; Chen, J; Xi, J. Nanozymes as Enzyme Inhibitors. International journal of nanomedicine 2021, 16, 1143–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H; Song, Y; Wang, Y; Wang, H; Ding, Z; Fan, K. Zno nanoparticles : improving photosynthesis, shoot development, and phyllosphere microbiome composition in tea plants. Journal of Nanobiotechnology 2024, 238. [Google Scholar]

- Rangel, LI; Leveau, JHJ. Applied microbiology of the phyllosphere. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology 2024, 108, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirelkhatim, A; Mahmud, S; Seeni, A. Review on Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles : Antibacterial Activity and Toxicity Mechanism. Nano-Micro Letters 2015, 7(3), 219–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stratil, P; Klejdus, B; Kubáň, V. Determination of Total Content of Phenolic Compounds and Their Antioxidant Activity in Vegetables s Evaluation of Spectrophotometric Methods. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 2006, 54, 607–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand-Williams, W; Cuvelier, ME; Berset, C. Use of a Free Radical Method to Evaluate Antioxidant Activity. LWT - Food Science and Technology 1995, 28, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benzie, IFF; Strain, JJ. The Ferric Reducing Ability of Plasma ( FRAP ) as a Measure of ‘‘ Antioxidant Power ”: The FRAP Assay. Analytical Biochemistry 1996, 76, 70–6. [Google Scholar]

- Singleton, VL; Rossi, JA. Colorimetry of Total Phenolics with Phosphomolybdic-Phosphotungstic Acid Reagents. Am J Enol Vitic. 1965, 16(16), 144–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo, FJ; Penel, C; Greppin, H. Peroxidase Release Induced by Ozone in Sedum album Leaves. Plant Physiology 1984, 74, 846–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakano, Y; Asada, K. Hydrogen Peroxide is Scavenged by Ascorbate-specific Peroxidase in Spinach Chloroplasts. Plant and Cell Physiology 1981, 22(5), 867–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhindsa, RS; Plumb-dhindsa, P; Thorpe, TA. Leaf Senescence: Correlated with Increased Levels of Membrane Permeability and Lipid Peroxidation, and Decreased Levels of Superoxide Dismutase and Catalase. Journal of Experimental Botany 1981, 32(1), 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucero, M; Estell, R; Fredrickson, E. A Retention Index Calculator Simplifi es Identifi cation of Plant Volatile Organic Compounds. Phytochemical Analysis 2009, 20, 378–84. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhang, D; Hua, T; Xiao, F; Chen, C; Gersberg, RM; Liu, Y; et al. Phytotoxicity and bioaccumulation of ZnO nanoparticles in Schoenoplectus tabernaemontani. Chemosphere 2015, 120, 211–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, TNM; Savassa, SM; Montanha, GS; Ishida, JK; Almeida, ED; Tsai, SM; et al. A new glance on root-to-shoot in vivo zinc transport and time- dependent physiological effects of ZnSO 4 and ZnO nanoparticles on plants. Scientific Reports 2019, 9(May), 10416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoon, S; Bae, S; Woo, Y; Sik, Y. Effects of particle size on toxicity, bioaccumulation, and translocation of zinc oxide nanoparticles to bok choy ( Brassica chinensis L.) in garden soil. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety 2024, 280(May), 116519. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J; Luo, X; Wang, Y; Feng, Y. Evaluation of zinc oxide nanoparticles on lettuce (Lactuca sativa L.) growth and soil bacterial community. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2018, 25, 6026–35. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y; Li, Y; Pan, B; Zhang, X; Zhang, H; Steinberg, CEW; et al. Application of low dosage of copper oxide and zinc oxide nanoparticles boosts bacterial and fungal communities in soil. Science of the Total Environment 2020, 143807. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, X; Cao, P; Wang, G; Liu, Y; Song, J; Han, J. CuO, ZnO, and γ-Fe2O3 nanoparticles modified the underground biomass and rhizosphere microbial community of Salvia miltiorrhiza ( Bge.) after 165-day exposure. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety 2021, 217, 113222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-pérez, DM; Marszalek, JE; Meza-velázquez, JA; Lafuente-rincon, DF; Salazar-ramírez, MT; Márquez-guerrero, SY; et al. Enhancing Nutraceutical Quality and Antioxidant Activity in Chili Pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) Fruit by Foliar Application of Green-Synthesized ZnO Nanoparticles ( ZnONPs ). Nanomaterials 2025, 15, 1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uresti-porras, J; Fuente MC de la; Benavides-mendoza, A; Olivares-Sáenz, E; Cabrera, RI; Juárez-Maldonado, A. Effect of Graft and Nano ZnO on Nutraceutical and Mineral. Plants 2021, 10, 2793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iziy, E; Majd, A; Vaezi-kakhki, MR; Nejadsattari, T; Noureini, SK. Effects of zinc oxide nanoparticles on enzymatic and nonenzymatic antioxidant content, germination, and biochemical and ultrastructural cell characteristics of Portulaca oleracea L. Acta Societatis Botanicorum Poloniae 2019, 88(4), 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miliauskien, J; Brazaitytė, A; Sutulienė, R; Urbutis, M; Tučkutė, S. ZnO Nanoparticle Size-Dependent Effects on Swiss Chard Growth and Nutritional Quality. Agriculture 2022, 12, 1905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adnan, M; Mahmood, F; Zhao, Z; Khaliq, H. Effect of the foliar application of biogenic-ZnO nanoparticles on physio-chemical analysis of chilli (Capsicum annum L.) in a salt stress environment. Environmental Science: Advances 2025, (4), 306–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uresti-porras, JG; Fuente MC de la; Benavides-mendoza, A; Sandoval, - A; Zermeño-gonzalez, A; Cabrera, RI; et al. Foliar application of zinc oxide nanoparticles and grafting improves the bell pepper ( Capsicum annuum L.) productivity grown in NFT system. Notulae Botanicae Horti Agrobotanici Cluj-Napoca 2021, 49(2), 12327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirakhorli, T; Ardebili, ZO; Ladan-moghadam, A; Danaee, E. Bulk and nanoparticles of zinc oxide exerted their beneficial effects by conferring modifications in transcription factors, histone deacetylase, carbon and nitrogen assimilation, antioxidant biomarkers, and. PLOS ONE 2021, 16(9), 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srivastav, A; Ganjewala, D; Singhal, RK; Rajput, VD; Minkina, T; Voloshina, M; et al. Effect of ZnO Nanoparticles on Growth and Biochemical Responses of Wheat and Maize. Plants 2021, 10, 2556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piesik, D; Wenda-piesik, A; Łyczko, J; Lemańczyk, G; Bocianowski, J; Piesik, M. Synergistic use of iron nanofertilizers and biotic elicitors to induce defensive volatile organic compound emissions from Brassica napus. Journal of Plant Protection Research 2024, 64(4), 336–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute of Standards and Technology. NIST Chemistry WebBook [Internet]. Available online: https://webbook.nist.gov.

- Gondor, OK; Magda, P; Janda, T; Szalai, G. The role of methyl salicylate in plant growth under stress conditions. Journal of Plant Physiology 2022, 277, 153809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singewar, K; Fladung, M; Robischon, M. Methyl salicylate as a signaling compound that contributes to forest ecosystem stability. Trees 2021, 35, 1755–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B; Kaurilind, E; Jiang, Y; Niinemets, Ü. Methyl salicylate di ff erently a ff ects benzenoid and terpenoid volatile emissions in Betula pendula. Tree Physiology 2018, 00(July), 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, X; Qian, R; Wang, D; Liu, L; Sun, C; Lin, X. Lipid-Derived Aldehydes : New Key Mediators of Plant Growth and Stress Responses. Biology 2022, 11, 1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincenti, S; Mariani, M; Alberti J christophe; Jacopini, S; Cara VB bronzini, D; Berti, L; et al. Biocatalytic Synthesis of Natural Green Leaf Volatiles Using the Lipoxygenase Metabolic Pathway. Catalysts 2019, 9, 873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J; Zhai, Y; Liu, G; Bosker, T; Vijver, MG; Peijnenburg, WJGM. Dissolution Dynamics and Accumulation of Ag Nanoparticles in a Microcosm Consisting of a Soil − Lettuce − Rhizosphere Bacterial Community. ACS Sustainable Chemistry and Engineering 2021, 9, 16172–81. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, L; Liu, J; Jiang, G. Nanoparticle-speci fi c transformations dictate nanoparticle effects associated with plants and implications for nanotechnology use in agriculture. Nature Communications 2024, 15, 7389. [Google Scholar]

- Maccormack, TJ; Clark, RJ; Dang, MKM; Ma, G; Kelly, JA; Veinot, JGC; et al. Inhibition of enzyme activity by nanomaterials : Potential mechanisms and implications for nanotoxicity testing. Nanotoxicology 2012, 6(5), 514–25. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Northwick, A; Wang, Y; Tuga, B; Haynes, C; Hernandez, R; Carlson, E. Molecular-Level Characterization of Protein-Nanoparticle Interactions: Orientation, Deformation and Matrix Effects [Internet]. ChemRxiv. 2025. Available online: https://chemrxiv.org/engage/chemrxiv/article-details/67746bab81d2151a0284c25d.

- Matsui, K. Green leaf volatiles : hydroperoxide lyase pathway of oxylipin metabolism. Current Opinion in plant Biology 2006, 9, 274–80. [Google Scholar]

- Nel, AE; Mädler, L; Velegol, D; Xia, T; Hoek, EMV; Somasundaran, P; et al. Understanding biophysicochemical interactions at the nano–bio interface; Nature Publishing Group, 2009; Volume 8, 7, pp. 543–57. [Google Scholar]

- Dimkpa, CO; McLean, JE; Latta, DE; Britt, DW; Johnson, WP; Boyanov, MI; et al. CuO and ZnO nanoparticles : phytotoxicity, metal speciation, and induction of oxidative stress in sand-grown wheat. Journal of Nanoparticle Research 2012, 14, 1125. [Google Scholar]

- wook, Park S; Kaimoyo, E; Kumar, D; Mosher, S; Klessig, D. Methyl Salicylate Is a Critical Mobile Signal for Plant Systemic Acquired Resistance. Science 2007, 318(113). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rico, CM; Majumdar, S; Duarte-gardea, M; Peralta-videa, JR; Gardea-torresdey, JL. Interaction of Nanoparticles with Edible Plants and Their Possible Implications in the Food Chain. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 2011, 59, 3485–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, M; Jana, A; Sinha, S; Jothiramajayam, M; Nag, A; Chakraborty, A; et al. Effects of ZnO nanoparticles in plants : Cytotoxicity, genotoxicity, deregulation of antioxidant defenses, and cell-cycle arrest. Mutation Research - Genetic Toxicology and Environmental Mutagenesis 2016, 807, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corso, M; Garcia, V. tolerance and hyperaccumulation in plants; Metallomics, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Presentato, A; Piacenza, E; Turner, RJ; Zannoni, D; Cappelletti, M. Processing of Metals and Metalloids by Actinobacteria : Cell Resistance Mechanisms and Synthesis of Metal ( loid ) -Based Nanostructures. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 2027. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, A; Sineriz, M; Merten, D; Bu, G; Kothe, E. Heavy metal resistance mechanisms in actinobacteria for survival in AMD contaminated soils. Geochemistry 2005, 65, 131–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goulsbra, AM; Edwards, C; Gallagher, MP. Surface hygiene monitored using a reporter of fis in Escherichia coli. Journal of applied Microbiology 2001, 91, 104–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stubbendieck, RM; Vargas-bautista, C; Straight, PD; Romero, DF; Beauregard, P. Bacterial Communities : Interactions to Scale. Frontiers in Microbiology 2016, 7, 1234. [Google Scholar]

| Treatment | [Zn], mg kg-1 |

| Ctrl | 88.55 ± 3.47 a |

| NP50 | 96.60 ± 2.98 b |

| B50 | 95.92 ± 2.51 b |

| NP500 | 119.7 ± 4.00 c |

| B500 | 128.7 ± 3.15 d |

| Treatment | Shannon diversity index | Simpson's index | Berger-Parker index |

| Ctrl | 4.11 | 0.960 | 0.100 |

| NP50 | 4.16 | 0.960 | 0.100 |

| B50 | 4.05 | 0.960 | 0.110 |

| NP500 | 4.23 | 0.963 | 0.097 |

| B500 | 4.30 | 0.960 | 0.100 |

| % Area | |||||||||

| Name | FM(1) | MM(2) | Ctrl | NP50 | B50 | NP500 | B500 | IK(exp) (3) | IK(lit) (4) |

| (Z)-3-Hexenal | C6H10O | 98.1 | 3.5 | 7.5 | 12.7 | - | 1.2 | 792.7 | 799.5 |

| n-Hexanal | C6H12O | 100.2 | 5.7 | 7.9 | 4.4 | 6.9 | 12.7 | 794.3 | 793.0 |

| (E)- 2-Hexenal | C6H10O | 98.1 | 11.4 | 11.9 | 12.9 | 8.1 | 6.1 | 854.2 | 854.0 |

| (Z)-3-Hexenol | C6H12O | 100.2 | 7.7 | 11.1 | 9.2 | 5.7 | 3.3 | 858.6 | 858.0 |

| (E)-2-Hexenol | C6H12O | 100.2 | 3.9 | 3.6 | 2.0 | 0.8 | 0.5 | 869.3 | 869.0 |

| p-Xylene | C8H10 | 106.2 | - | - | - | 2.1 | 0.8 | 869.7 | 865.0 |

| n-Hexanol | C6H14O | 102.2 | 8.0 | 4.3 | 6.7 | - | 2.2 | 871.3 | 871.0 |

| (Z)-3-Hexenyl Acetate | C8H14O2 | 142.2 | 15.9 | 14.4 | 7.3 | 9.0 | 0.8 | 1005.2 | 1007.0 |

| n-Hexyl Acetate | C8H16O2 | 144.2 | 2.7 | 1.9 | 0.8 | 1.0 | - | 1012.4 | 1012.0 |

| 2-Hexenyl Acetate | C8H14O2 | 142.2 | 3.5 | 3.7 | 0.5 | 1.4 | - | 1015.4 | 1017.0 |

| Indene | C9H8 | 116.2 | 0.1 | 1.3 | - | 0.03 | - | 1046.5 | 1051.0 |

| Linalool | C10H18O | 154.2 | 1.4 | - | 0.05 | - | - | 1097.8 | 1098.0 |

| n-Nonanal | C9H18O | 142.2 | 1.1 | 1.7 | 3.4 | 4.9 | 3.8 | 1102.2 | 1102.0 |

| Methyl Salicylate | C8H8O3 | 152.1 | 24.4 | 12.0 | 0.2 | 16.6 | 41.7 | 1196.9 | 1196.0 |

| n-Decanal | C10H20O | 156.3 | 0.5 | 1.2 | 2.8 | 3.5 | 2.6 | 1204.0 | 1204.0 |

| 2-Ethyl-3-hydroxyhexyl-2-methylpropanoate | C12H24O3 | 216.3 | 0.5 | 1.3 | 0.1 | 2.8 | 2.3 | 1377.3 | 1373.0 |

| n-Decyl Acetate | C12H24O2 | 200.3 | - | 1.4 | - | 0.5 | - | 1406.2 | 1408.0 |

| β-Farnesene | C15H24 | 204.4 | - | - | 17.0 | - | 1.3 | 1457.1 | 1457.0 |

| 1-Dodecanol | C12H26O | 186.3 | 0.9 | 3.0 | 1.0 | 3.4 | 3.4 | 1472.3 | 1472.0 |

| 2,2,4-Trimethyl-1,3-pentanediol diisobutyrate | C16H30O4 | 286.4 | 0.6 | 1.7 | - | 3.9 | 1.9 | 1597.4 | 1587.5 |

| α-Bisabolol | C15H26O | 222.4 | 0.3 | - | - | 2.9 | 1.1 | 1675.8 | 1685.0 |

| 2-Ethylhexyl salicylate | C15H22O3 | 250.3 | 0.2 | 0.4 | - | 1.0 | 0.8 | 1810.9 | 1812.0 |

| Isopropyl myristate | C17H34O2 | 270.5 | - | - | 0.1 | 1.2 | 0.3 | 1821.4 | 1823.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).