Submitted:

03 January 2026

Posted:

05 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Objectives

- Extract radiomics data describing breast lesions and lymphatic nodes in mammograms; compute the descriptive statistics for the masses and nodes in benign and malignant cases.

- Explore associations between radiomics of masses and lymph nodes in patients with benign breast tumours and cancer.

- Build diagnostic models distinguishing benign and malignant cases; assess the predictive value of radiomics data retrieved from masses and lymph modes.

- Construct models predicting the molecular subtypes of BC.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Cohort

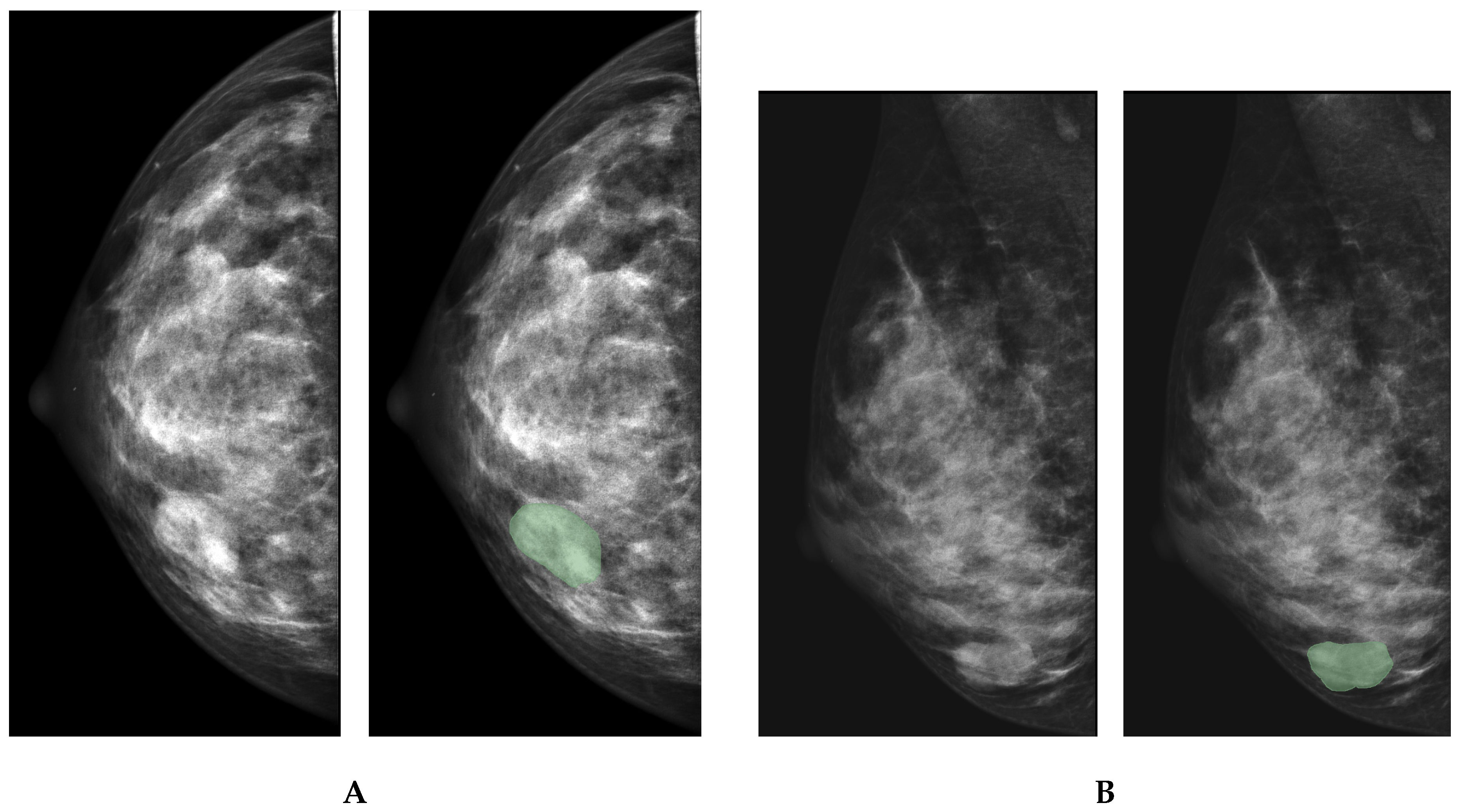

3.2. Data Preprocessing

3.3. Study Methodology

4. Results

4.1. Quantitative Characteristics of Mammogram Images

4.2. Performance of Binary Classification Models

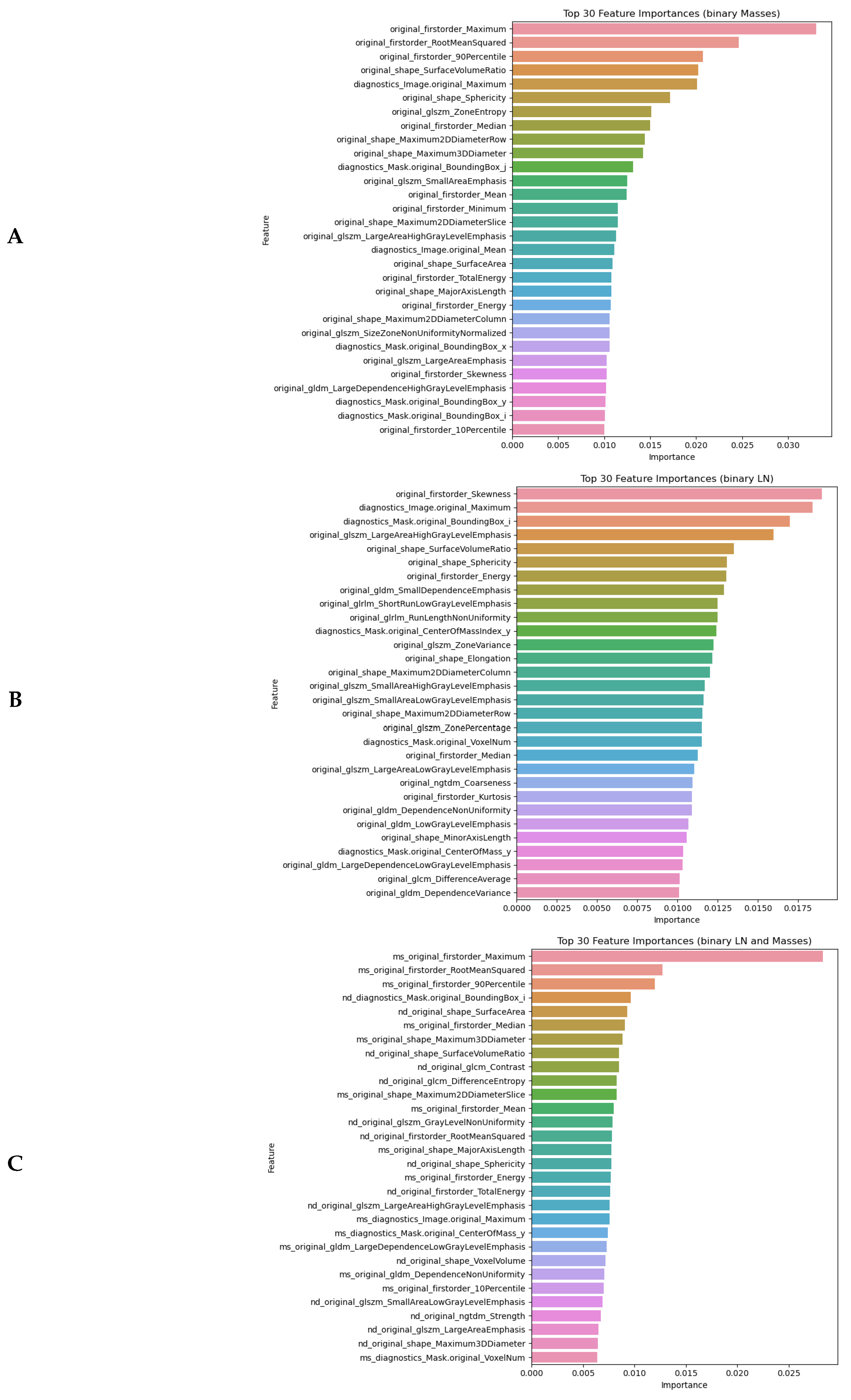

4.2.1. Feature Importance in Detecting Malignancy

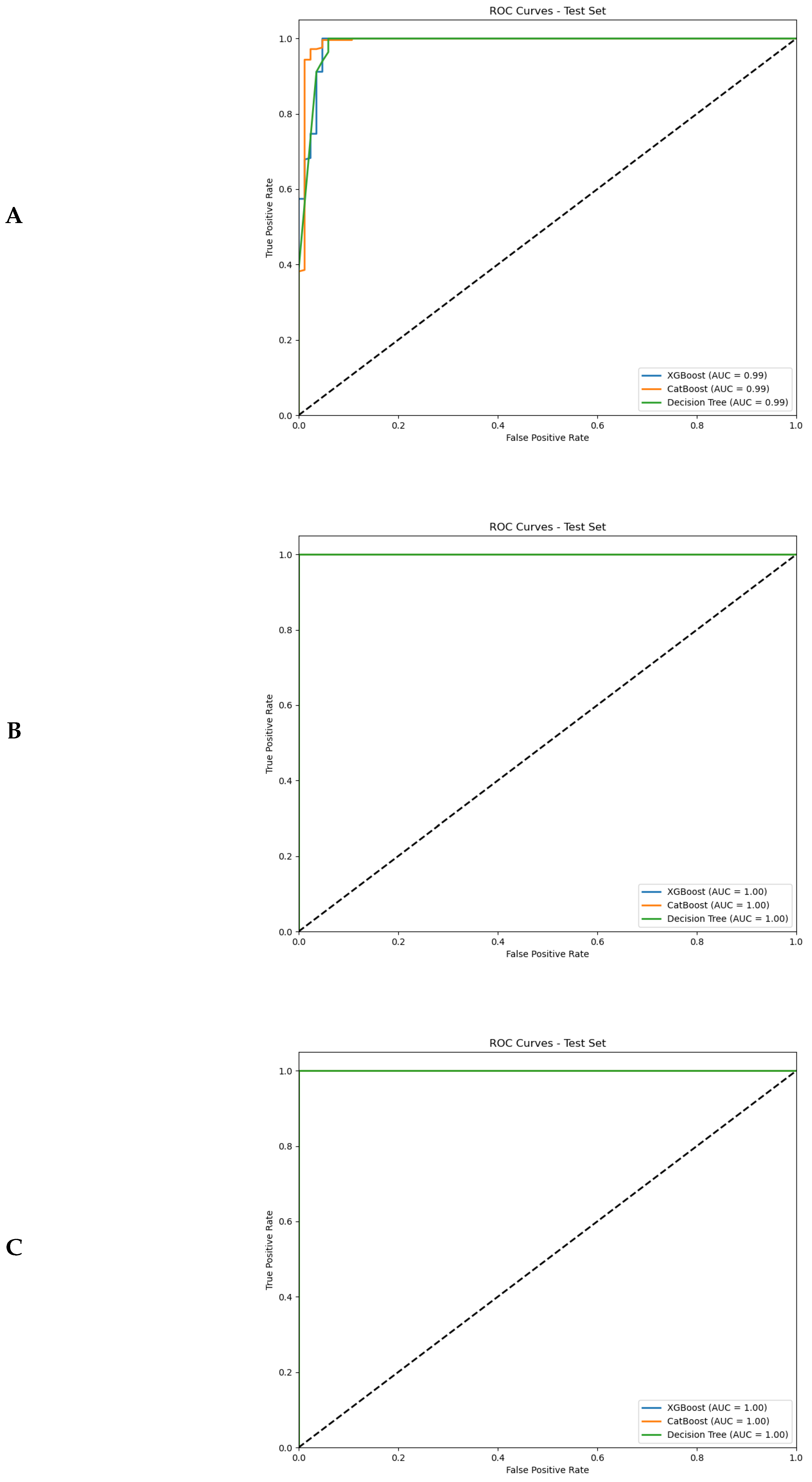

4.2.2. Prediction of Cancerous Tumours and Metastases from Radiomics Features

4.3. Identification of Molecular Subtypes from Radiomics Features

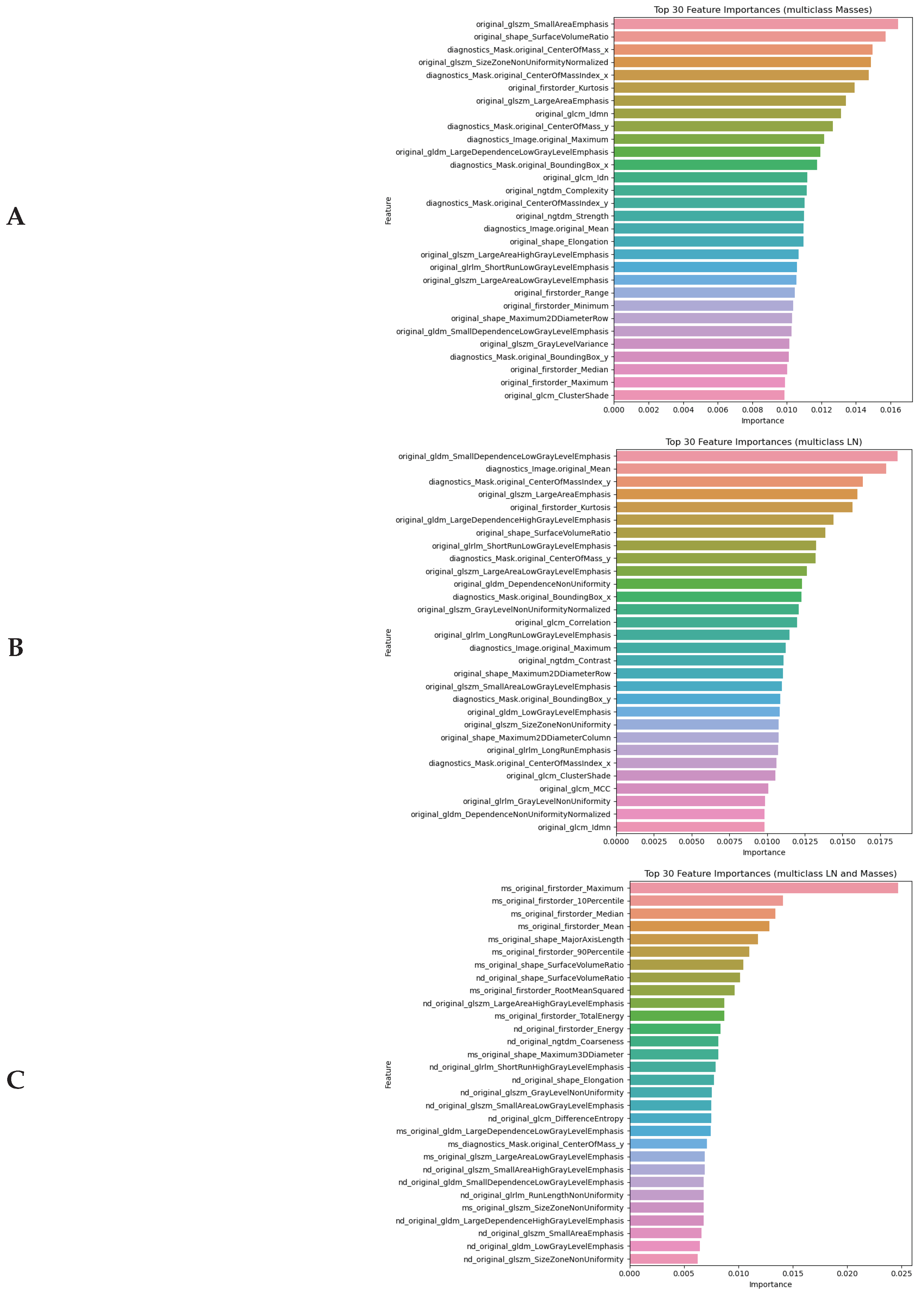

4.3.1. Top Informative Features in Distinguishing Between Molecular Subtypes

4.3.2. Performance of ML Models in Identification of Molecular Subtype of BC

5. Discussion

5.1. Radimoic Approach to Distinguishing Between Malignant and Benign Lesions

5.2. Classification Accuracy of Models Distinguishing Between Benign and Malignant Cases

5.2.1. Detection of Malignant Breast Masses

5.2.2. Identification of Lymph Node Metastases

5.3. Application of Radiomics for Detecting Molecular Subtypes of Cancer

Strength and Limitations

- The application of radiomics provides a comprehensive phenotypic profile of breast lesions through quantitative characterization of shape, intensity, texture, and wavelength features. This approach aligns with the principles of personalized medicine by enabling non-invasive tumor characterization.

- Integration of radiomic features from both breast masses and LNs yielded superior classification accuracy (AUC-ROC up to 0.99) compared to single-region analyses. The biological interpretability of these features bridges the gap between imaging findings and clinical decision-making.

- The integration of both breast mass and lymph node features yielded superior classification performance compared to single-region analyses, with binary classification models achieving exceptional discriminative ability (AUC-ROC up to 0.99).

- TModel robustness was ensured through stratified sampling, Bayesian hyperparameter optimization, and comparative evaluation of multiple classifier architectures (XGBoost, CatBoost, Random Forest). This systematic approach identified optimal algorithms for distinct diagnostic tasks.

- The study objective extended beyond conventional benign/malignant classification by demonstrating radiomics’ ability to infer molecular subtypes non-invasively. This could reduce unnecessary biopsies and associated complications (e.g., pain, bleeding, infection [15] and rare but clinically significant neoplastic seeding[77]).

- A notable limitation is that pixel value in MAMs reflects the summary density of the mammary gland and varies with regard to acquisition parameters. Hence, the imaging data should be collected with the same mammography. Alternatively, a new dataset should be collected for another device, and the machine learning models should be retrained with the radiomical predictors extracted from new MAMs. When it is not feasible, bioengineers should harmonise the data to ensure model generalisability.

- Manual segmentation of ROIs is operator-dependent, and it may introduce intra- and inter-observer bias. To minimise the impact of the bias on study findings, our research team comprised two radiologists who delineated ROIs independently. The third radiologist compared segmentation masks and selected the best one for extracting radiomical features within the mask borders. In the future, semi- or fully automatic segmentation with deep learning networks can help us overcome this limitation.

- Inbreast dataset does not contain information on the histological verification of metastatic growth inside the lymph nodes that can be detected on the mammograms. Some of the nodes visible at MAM can still be free from metastasis; however, the chance for this occasion is low, and it should not strongly impact the final statistics.

- The open-source dataset does not describe the specific location of biopsies. Most likely, they were taken from the masses and nodes detected with MAMs. The limitation is common to all studies conducted with these data.

- Limited sample size for rare subtypes (e.g., TNBC: n=42) can affect model generalizability.

- The observed performance disparities across molecular subtypes suggest that current feature sets may not fully capture relevant biological heterogeneity. The moderate AUC-ROC values for HER2+ (0.72) and TNBC (0.77) classification leave room for improvement in subtype discrimination.

Conclusion

- Radiomics features extracted from MAM effectively differentiated between benign and malignant breast lesions and LNa. Significant differences across nearly all feature groups support the utility of radiomics in characterizing tumour morphology and intensity distribution.

- LN images exhibited a greater number of discriminative radiomic features compared to breast parenchyma scans. Supposedly, the analysis of nodal structures provides additional diagnostic insights beyond lesion characterization alone.

- The integration of radiomic data from both breast masses and LNs enhanced the interpretability of disease phenotype, providing a more holistic image-based biomarker signature for malignancy.

- ML classifiers demonstrated high accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity in distinguishing benign from malignant lesions using radiomics features. The combination of breast mass and lymph node features yielded the highest overall performance: accuracy exceeded 97% in validation datasets.

- Shape and first-order statistical features had the highest predictive power in malignancy detection. This highlights the diagnostic value of tumour morphology and internal texture intensity in AI-based classification models.

- The Random Forest model achieved accuracy above 0.868 and sensitivity greater than 0.91 in classifying breast cancer molecular subtypes from radiomic features. Although the model struggled to identify TNBC in the training dataset, the performance improved substantially in validation.

Author Contributions

Funding

Abbreviations

| AI | artificial intelligence |

| ANL | axillary lymph nodes |

| BC | breast cancer |

| CC | craniocaudal |

| HER2+ | Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor-2 overexpressing |

| MAM | mammography |

| MBM | molecular biomarker |

| MLO | mediolateral oblique |

| NSLN | non-sentinel lymph node |

| ROI | region of interests |

| SLN | sentinel lymph node |

| LABC | Luminal A |

| LBBC | Luminal B |

| TNBC | Triple Negative |

References

- World health organization: Breast cancer Kernel Description. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/breast-cancer (accessed on 18 November 2024).

- Hanna, T.P.; King, W.D.; Thibodeau, S.; Jalink, M.; Paulin, G.A.; Harvey-Jones, E.; O’Sullivan, D.E.; Booth, C.M.; Sullivan, R.; Aggarwal, A. Mortality due to cancer treatment delay: systematic review and meta-analysis. bmj 2020, 371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Survival for breast cancer. Available online: https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/breast-cancer/survival (accessed on 18 November 2024).

- Zielonke, N.; Gini, A.; Jansen, E.E.; Anttila, A.; Segnan, N.; Ponti, A.; Veerus, P.; de Koning, H.J.; van Ravesteyn, N.T.; Heijnsdijk, E.A.; et al. Evidence for reducing cancer-specific mortality due to screening for breast cancer in Europe: A systematic review. European journal of cancer 2020, 127, 191–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes, J.D.B.; Morgan, E.; de Luna Aguilar, A.; Mafra, A.; Shah, R.; Giusti, F.; Vignat, J.; Znaor, A.; Musetti, C.; Yip, C.H.; et al. Global stage distribution of breast cancer at diagnosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA oncology 2024, 10, 71–78. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L. Early diagnosis of breast cancer. Sensors 2017, 17, 1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhargava, D.; Rattanadecho, P.; Jiamjiroch, K. Microwave imaging for breast Cancer detection-A Comprehensive review. Engineered Science 2024, 30, 1116. [Google Scholar]

- Brożek-Płuska, B.; Placek, I.; Kurczewski, K.; Morawiec, Z.; Tazbir, M.; Abramczyk, H. Breast cancer diagnostics by Raman spectroscopy. Journal of Molecular Liquids 2008, 141, 145–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arriaga-Canon, C.; Contreras-Espinosa, L.; Aguilar-Villanueva, S.; Bargalló-Rocha, E.; García-Gordillo, J.A.; Cabrera-Galeana, P.; Castro-Hernández, C.; Jiménez-Trejo, F.; Herrera, L. The clinical utility of lncRNAs and their application as molecular biomarkers in breast cancer. International journal of molecular sciences 2023, 24, 7426. [Google Scholar]

- Alam, M.S.; Sultana, A.; Reza, M.S.; Amanullah, M.; Kabir, S.R.; Mollah, M.N.H. Integrated bioinformatics and statistical approaches to explore molecular biomarkers for breast cancer diagnosis, prognosis and therapies. PloS one 2022, 17, e0268967. [Google Scholar]

- Lang, J.E.; Wecsler, J.S.; Press, M.F.; Tripathy, D. Molecular markers for breast cancer diagnosis, prognosis and targeted therapy. Journal of surgical oncology 2015, 111, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ren, W.; Chen, M.; Qiao, Y.; Zhao, F. Global guidelines for breast cancer screening: a systematic review. The Breast 2022, 64, 85–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zielonke, N.; Kregting, L.M.; Heijnsdijk, E.A.; Veerus, P.; Heinävaara, S.; McKee, M.; de Kok, I.M.; de Koning, H.J.; van Ravesteyn, N.T.; collaborators, E.T. The potential of breast cancer screening in Europe. International journal of cancer 2021, 148, 406–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Chen, W.; Li, N.; Shen, H.; Li, J.; Wang, Y.; Tian, J.; Zhou, B.; et al. China guideline for the screening and early detection of female breast cancer (2021, Beijing). Zhonghua Zhong liu za zhi [Chinese Journal of Oncology] 2021, 43, 357–382. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pesapane, F.; De Marco, P.; Rapino, A.; Lombardo, E.; Nicosia, L.; Tantrige, P.; Rotili, A.; Bozzini, A.C.; Penco, S.; Dominelli, V.; et al. How radiomics can improve breast cancer diagnosis and treatment. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2023, 12, 1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicosia, L.; Pesapane, F.; Bozzini, A.C.; Latronico, A.; Rotili, A.; Ferrari, F.; Signorelli, G.; Raimondi, S.; Vignati, S.; Gaeta, A.; et al. Prediction of the malignancy of a breast lesion detected on breast ultrasound: radiomics applied to clinical practice. Cancers 2023, 15, 964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statsenko, Y.; Al Zahmi, F.; Habuza, T.; Neidl-Van Gorkom, K.; Zaki, N. Prediction of COVID-19 severity using laboratory findings on admission: informative values, thresholds, ML model performance. BMJ open 2021, 11, e044500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leibig, C.; Brehmer, M.; Bunk, S.; Byng, D.; Pinker, K.; Umutlu, L. Combining the strengths of radiologists and AI for breast cancer screening: a retrospective analysis. The Lancet Digital Health 2022, 4, e507–e519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freeman, K.; Geppert, J.; Stinton, C.; Todkill, D.; Johnson, S.; Clarke, A.; Taylor-Phillips, S. Use of artificial intelligence for image analysis in breast cancer screening programmes: systematic review of test accuracy. bmj 2021, 374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barba, D.; León-Sosa, A.; Lugo, P.; Suquillo, D.; Torres, F.; Surre, F.; Trojman, L.; Caicedo, A. Breast cancer, screening and diagnostic tools: All you need to know. Critical reviews in oncology/hematology 2021, 157, 103174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarighati, E.; Keivan, H.; Mahani, H. A review of prognostic and predictive biomarkers in breast cancer. Clinical and experimental medicine 2023, 23, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orrantia-Borunda, E.; Anchondo-Nuñez, P.; Acuña-Aguilar, L.E.; Gómez-Valles, F.O.; Ramírez-Valdespino, C.A. Subtypes of breast cancer. Breast Cancer [Internet] 2022. [Google Scholar]

- (NIH), N.C.I. Cancer Stat Facts: Female Breast Cancer Subtypes; c2019-2022. Available online: https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/breast-subtypes.html (accessed on 20 November 2024).

- Moreira, I.C.; Amaral, I.; Domingues, I.; Cardoso, A.; Cardoso, M.J.; Cardoso, J.S. Inbreast: toward a full-field digital mammographic database. Academic radiology 2012, 19, 236–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welcome to pyradiomics documentation! Available online: https://pyradiomics.readthedocs.io/en/latest/ (accessed on 18 November 2024).

- Wu, A.; Wu, C.; Zeng, Q.; Cao, Y.; Shu, X.; Luo, L.; Feng, Z.; Tu, Y.; Jie, Z.; Zhu, Y.; et al. Development and validation of a CT radiomics and clinical feature model to predict omental metastases for locally advanced gastric cancer. Scientific Reports 2023, 13, 8442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardakani, A.A.; Bureau, N.J.; Ciaccio, E.J.; Acharya, U.R. Interpretation of radiomics features–a pictorial review. Computer methods and programs in biomedicine 2022, 215, 106609. [Google Scholar]

- Castro-Tapia, S.; Castaneda-Miranda, C.L.; Olvera-Olvera, C.A.; Guerrero-Osuna, H.A.; Ortiz-Rodriguez, J.M.; Martinez-Blanco, M.d.R.; Diaz-Florez, G.; Mendiola-Santibanez, J.D.; Solis-Sanchez, L.O. Classification of breast cancer in mammograms with deep learning adding a fifth class. Applied Sciences 2021, 11, 11398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, M.; Rim, B.; Lee, H.; Jang, H.; Oh, J.; Choi, S. Multi-class classification of lung diseases using CNN models. Applied Sciences 2021, 11, 9289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Fan, M.; Zhang, J.; Li, L. Discriminating between benign and malignant breast tumors using 3D convolutional neural network in dynamic contrast enhanced-MR images. Proceedings of the Medical Imaging 2017: Imaging Informatics for Healthcare, Research, and Applications. SPIE 2017, Vol. 10138, 44–51. [Google Scholar]

- Litvin, A.; Burkin, D.; Kropinov, A.; Paramzin, F. Radiomics and digital image texture analysis in oncology. Sovremennye tehnologii v medicine 2021, 13, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Guo, Y.; Jin, Q. Radiomics and its feature selection: A review. Symmetry 2023, 15, 1834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, M.T.; Liu, X.; Gao, Y.; Shi, R.; Jiang, L.; Yao, J. Radiomics-based quantitative contrast-enhanced CT analysis of abdominal lymphadenopathy to differentiate tuberculosis from lymphoma. Precision Clinical Medicine 2024, 7, pbae002. [Google Scholar]

- Su, T.H.; Kao, J.H. Artificial Intelligence, Machine Learning, and Deep Learning in Precision Medicine in Liver Diseases: Concept, Technology, Application and Perspectives; Elsevier, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Rizzo, S.; Botta, F.; Raimondi, S.; Origgi, D.; Fanciullo, C.; Morganti, A.G.; Bellomi, M. Radiomics: the facts and the challenges of image analysis. European radiology experimental 2018, 2, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Limkin, E.J.; Reuzé, S.; Carré, A.; Sun, R.; Schernberg, A.; Alexis, A.; Deutsch, E.; Ferté, C.; Robert, C. The complexity of tumor shape, spiculatedness, correlates with tumor radiomic shape features. Scientific reports 2019, 9, 4329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Zhu, L.; Zhou, G.; He, J.; Jiang, Y.; Chen, Y. Predicting the pathological status of mammographic microcalcifications through a radiomics approach. Intelligent Medicine 2021, 1, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Shi, D.; Guo, Q.; Zhang, H.; Wang, S.; Ren, K. Radiomics based on digital mammography helps to identify mammographic masses suspicious for cancer. Frontiers in oncology 2022, 12, 843436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, L.; Ehmke, R.C.; Schwartz, L.H.; Zhao, B. Assessing agreement between radiomic features computed for multiple CT imaging settings. PloS one 2016, 11, e0166550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Corso, G.; Germanese, D.; Caudai, C.; Anastasi, G.; Belli, P.; Formica, A.; Nicolucci, A.; Palma, S.; Pascali, M.A.; Pieroni, S.; et al. Adaptive Machine Learning Approach for Importance Evaluation of Multimodal Breast Cancer Radiomic Features. Journal of Imaging Informatics in Medicine 2024, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chitalia, R.D.; Kontos, D. Role of texture analysis in breast MRI as a cancer biomarker: A review. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging 2019, 49, 927–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z.; Tan, L.K.; Ng, B.; Rahmat, K.; Ramli, M.; Ninomiya, K.; Wong, J. A radiomics study of textural features using magnetic resonance imaging for classification of breast cancer subtypes. In Proceedings of the Journal of Physics: Conference Series; IOP Publishing, 2020; Vol. 1497, p. 012015. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Kato, F.; Oyama-Manabe, N.; Li, R.; Cui, Y.; Tha, K.K.; Yamashita, H.; Kudo, K.; Shirato, H. Identifying triple-negative breast cancer using background parenchymal enhancement heterogeneity on dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI: a pilot radiomics study. PloS one 2015, 10, e0143308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braman, N.M.; Etesami, M.; Prasanna, P.; Dubchuk, C.; Gilmore, H.; Tiwari, P.; Plecha, D.; Madabhushi, A. Intratumoral and peritumoral radiomics for the pretreatment prediction of pathological complete response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy based on breast DCE-MRI. Breast Cancer Research 2017, 19, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Mahdavi, H.; Kaveh, V.; Karami, F.; Rahimi, M.A. Association between Radiological and First-Order Statistical Features of the Mammogram, and the Tumor Phenotype in Breast Cancer Patients: Statistical features of mammogram and breast cancer. Archives of Breast Cancer 2024, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parekh, V.S.; Jacobs, M.A. Multiparametric radiomics methods for breast cancer tissue characterization using radiological imaging. Breast cancer research and treatment 2020, 180, 407–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panico, A.; Gatta, G.; Salvia, A.; Grezia, G.D.; Fico, N.; Cuccurullo, V. Radiomics in Breast Imaging: Future Development. Journal of personalized medicine 2023, 13, 862. [Google Scholar]

- Tsougos, I.; Vamvakas, A.; Kappas, C.; Fezoulidis, I.; Vassiou, K. Application of radiomics and decision support systems for breast MR differential diagnosis. Computational and mathematical methods in medicine 2018, 2018, 7417126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelardi, F.; Cavinato, L.; De Sanctis, R.; Ninatti, G.; Tiberio, P.; Rodari, M.; Zambelli, A.; Santoro, A.; Fernandes, B.; Chiti, A.; et al. The Predictive Role of Radiomics in Breast Cancer Patients Imaged by [18F] FDG PET: Preliminary Results from a Prospective Cohort. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 2312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karthik, R.; Menaka, R.; Kathiresan, G.; Anirudh, M.; Nagharjun, M. Gaussian dropout based stacked ensemble CNN for classification of breast tumor in ultrasound images. Irbm 2022, 43, 715–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, W.K.; Chen, I.L.; Chang, J.M.; Shin, S.U.; Lo, C.M.; Chang, R.F. The adaptive computer-aided diagnosis system based on tumor sizes for the classification of breast tumors detected at screening ultrasound. Ultrasonics 2017, 76, 70–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, M.D.; Saleem, A.; Elahi, H.; Khan, M.A.; Khan, M.I.; Yaqoob, M.M.; Farooq Khattak, U.; Al-Rasheed, A. Breast cancer classification through meta-learning ensemble technique using convolution neural networks. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 2242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, Y.; Huang, Q.; Li, X. Segmentation information with attention integration for classification of breast tumor in ultrasound image. Pattern Recognition 2022, 124, 108427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parekh, V.S.; Jacobs, M.A. Integrated radiomic framework for breast cancer and tumor biology using advanced machine learning and multiparametric MRI. NPJ breast cancer 2017, 3, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhuang, S.; Li, D.a.; Zhao, J.; Ma, Y. Benign and malignant classification of mammogram images based on deep learning. Biomedical Signal Processing and Control 2019, 51, 347–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaidehi, K.; Subashini, T. Automatic characterization of benign and malignant masses in mammography. Procedia Computer Science 2015, 46, 1762–1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avcı, H.; Karakaya, J. A novel medical image enhancement algorithm for breast cancer detection on mammography images using machine learning. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Dhabyani, W.; Gomaa, M.; Khaled, H.; Fahmy, A. Dataset of breast ultrasound images. Data in brief 2020, 28, 104863. [Google Scholar]

- Suckling, J.; Parker, J.; Dance, D.; Astley, S.; Hutt, I.; Boggis, C.; Ricketts, I.; Stamatakis, E.; Cerneaz, N.; Kok, S.; et al. Mammographic image analysis society (mias) database v1. 21. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Song, B.I. A machine learning-based radiomics model for the prediction of axillary lymph-node metastasis in breast cancer. Breast Cancer 2021, 28, 664–671. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Y.W.; Huang, C.S.; Shih, C.C.; Chang, R.F. Axillary lymph node metastasis status prediction of early-stage breast cancer using convolutional neural networks. Computers in Biology and Medicine 2021, 130, 104206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Wu, L.; Ye, W.; Zhao, K.; Wang, Y.; Liu, W.; Li, J.; Li, H.; Liu, Z.; Liang, C. Deep learning signature based on staging CT for preoperative prediction of sentinel lymph node metastasis in breast cancer. Academic Radiology 2020, 27, 1226–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Kong, C.; Lin, G.; Chen, W.; Guo, X.; Chen, Y.; Cheng, X.; Chen, M.; Shi, C.; Xu, M.; et al. Development and validation of convolutional neural network-based model to predict the risk of sentinel or non-sentinel lymph node metastasis in patients with breast cancer: a machine learning study. EClinicalMedicine 2023, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Ni, S.; Yang, C.; Sun, W.; Huang, D.; Su, H.; Shu, J.; Qin, N. Axillary lymph node metastasis prediction by contrast-enhanced computed tomography images for breast cancer patients based on deep learning. Computers in Biology and Medicine 2021, 136, 104715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; He, Z.; Ouyang, J.; Tan, Y.; Chen, Y.; Gu, Y.; Mao, L.; Ren, W.; Wang, J.; Lin, L.; et al. Magnetic resonance imaging radiomics predicts preoperative axillary lymph node metastasis to support surgical decisions and is associated with tumor microenvironment in invasive breast cancer: A machine learning, multicenter study. EBioMedicine 2021, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Liu, Z.; Sun, C.; Zhang, L.; Wang, Y.; Li, Z.; Shi, J.; Wu, T.; Cui, H.; Zhang, J.; et al. Deep learning radiomics of ultrasonography: Identifying the risk of axillary non-sentinel lymph node involvement in primary breast cancer. EBioMedicine 2020, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Ren, C.; Liu, G.; Shui, R.; Zhang, Y.; Li, J.; Shao, Z. Development of high-resolution dedicated PET-based radiomics machine learning model to predict axillary lymph node status in early-stage breast cancer. Cancers 2022, 14, 950. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, L.Q.; Wu, X.L.; Huang, S.Y.; Wu, G.G.; Ye, H.R.; Wei, Q.; Bao, L.Y.; Deng, Y.B.; Li, X.R.; Cui, X.W.; et al. Lymph node metastasis prediction from primary breast cancer US images using deep learning. Radiology 2020, 294, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Mutasa, S.; Liu, M.Z.; Nemer, J.; Sun, M.; Siddique, M.; Desperito, E.; Jambawalikar, S.; Ha, R.S. Deep learning prediction of axillary lymph node status using ultrasound images. Computers in Biology and Medicine 2022, 143, 105250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, J.; Lee, S.E.; Kim, E.K.; Kim, S. Prediction of breast cancer molecular subtypes using radiomics signatures of synthetic mammography from digital breast tomosynthesis. Scientific reports 2020, 10, 21566. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhu, S.; Wang, S.; Guo, S.; Wu, R.; Zhang, J.; Kong, M.; Pan, L.; Gu, Y.; Yu, S. Contrast-enhanced mammography radiomics analysis for preoperative prediction of breast cancer molecular subtypes. Academic Radiology 2024, 31, 2228–2238. [Google Scholar]

- Ge, S.; Yixing, Y.; Jia, D.; Ling, Y. Application of mammography-based radiomics signature for preoperative prediction of triple-negative breast cancer. BMC Medical Imaging 2022, 22, 166. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Bian, H.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, Y.; Yin, G.; Wang, Z.; Li, X.; Ma, W.; Xu, W. Molecular subtype classification of breast cancer using established radiomic signature models based on 18F-FDG PET/CT images. Frontiers in Bioscience-Landmark 2021, 26, 475–484. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, J.; Tan, H.; Bai, Y.; Li, J.; Lu, Q.; Chen, R.; Zhang, M.; Feng, Q.; Wang, M. Evaluating the HER-2 status of breast cancer using mammography radiomics features. European journal of radiology 2019, 121, 108718. [Google Scholar]

- Ansari, B.; Morton, M.J.; Adamczyk, D.L.; Jones, K.N.; Brodt, J.K.; Degnim, A.C.; Jakub, J.W.; Lohse, C.M.; Boughey, J.C. Distance of breast cancer from the skin and nipple impacts axillary nodal metastases. Annals of surgical oncology 2011, 18, 3174–3180. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kong, Y.C.; Bhoo-Pathy, N.; O’Rorke, M.; Subramaniam, S.; Bhoo-Pathy, N.T.; See, M.H.; Jamaris, S.; Teoh, K.H.; Bustam, A.Z.; Looi, L.M.; et al. The association between methods of biopsy and survival following breast cancer: A hospital registry based cohort study. Medicine 2020, 99, e19093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bick, U.; Trimboli, R.M.; Athanasiou, A.; Balleyguier, C.; Baltzer, P.A.; Bernathova, M.; Borbély, K.; Brkljacic, B.; Carbonaro, L.A.; Clauser, P.; et al. Image-guided breast biopsy and localisation: recommendations for information to women and referring physicians by the European Society of Breast Imaging. Insights into imaging 2020, 11, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Models | Binary classification | Multi-class classification | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Radiomical data | Benign | Malignant | Luminal A | Luminal B | HER2-enriched | Triple negative | |

| Breast masses | 418 | 1243 | 81 | 196 | 70 | 42 | |

| Lymph nodes | 88 | 308 | 18 | 54 | 19 | 8 | |

| Masses & nodes | 156 | 561 | 35 | 99 | 37 | 15 | |

| BREAST MASSES | LYMPH NODES | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| benign | malignant | p1−2 | benign | malignant | p3−4 | p1−3 | p2−4 | |

| n1=418 | n2=1243 | n3=88 | n4=308 | |||||

| DIAGNOSTICS IMAGE-ORIGINAL | ||||||||

| Maximum | 228.28±17.49 | 238.4±14.20 | <0.01 | 229.91±16.18 | 236.28±15.57 | <0.01 | 0.45 | 0.02 |

| Mean | 15.73±5.90 | 17.04±7.21 | 0.01 | 19.52±6.23 | 20.94±6.85 | 0.07 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| DIAGNOSTICS MASK-ORIGINAL | ||||||||

| 237.97±147.04 | 241.92±109.33 | <0.01 | 166.41±112.13 | 188.56±134.34 | 0.42 | <0.01 | <0.01 | |

| 281.46±221.80 | 277.20±156.42 | <0.01 | 216.42±147.49 | 267.74±215.36 | 0.12 | 0.01 | <0.01 | |

| 843.78±618.02 | 788.08±647.76 | 0.09 | 892.35±839.39 | 786.91±817.25 | 0.28 | 0.58 | 0.09 | |

| 1020.6±345.84 | 993.35±345.20 | 0.23 | 69.66±127.35 | 91.22±188.47 | 0.45 | <0.01 | <0.01 | |

| 90.68±58.57 | 85.53±60.80 | 0.11 | 91.94±78.36 | 82.80±76.75 | 0.46 | 0.62 | 0.11 | |

| 109.11±30.80 | 106.43±31.33 | 0.16 | 16.48±12.95 | 20.88±18.54 | 0.03 | <0.01 | <0.01 | |

| 963.74±622.44 | 909.04±646.17 | 0.11 | 977.10±832.76 | 879.96±815.65 | 0.46 | 0.62 | 0.11 | |

| 1159.61±327.31 | 1131.13±332.93 | 0.16 | 175.13±137.64 | 221.93±197.03 | 0.03 | <0.01 | <0.01 | |

| VolumeNum | 1.13±0.84 | 2.52±5.10 | <0.01 | 2.15±1.44 | 2.40±2.42 | 0.79 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| VoxelNum | 6.4e05±1.0e06 | 4.8e05±6.0e05 | 0.04 | 1.0e05±6.9e04 | 1.9e05±2.4e05 | 0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| ORIGINAL FIRST ORDER | ||||||||

| 10Percentile | 83.41±35.41 | 105.11±39.87 | <0.01 | 72.36±37.54 | 87.76±42.58 | 0.002 | 0.003 | <0.01 |

| 90Percentile | 156.96±37.13 | 181.16±39.13 | <0.01 | 120.98±45.53 | 143.40±48.74 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Energy | 9.0e10±1.4e10 | 1.0e10±1.1e10 | <0.01 | 1.2e09±1.4e09 | 3.4e09±7.2e09 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Entropy | 2.45±0.39 | 2.49±0.40 | 0.03 | 1.94±0.41 | 2.08±0.47 | 0.003 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Interquartile Range | 40.09±13.42 | 41.88±13.37 | 0.01 | 25.97±9.22 | 30.21±13.33 | 0.004 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Kurtosis | 2.85±0.87 | 2.86±1.22 | 0.26 | 3.09±0.76 | 3.17±1.79 | 0.07 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Maximum | 204.73±30.12 | 224.70±27.58 | <0.01 | 165.69±45.80 | 186.59±43.78 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Mean | 120.61±36.03 | 144.32±39.52 | <0.01 | 96.21±41.50 | 115.34±45.66 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Mean Absolute Deviation | 22.92±6.59 | 23.78±6.83 | 0.01 | 15.16±5.02 | 17.50±6.56 | 0.002 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Median | 121.20±38.07 | 145.76±41.81 | <0.01 | 95.43±42.37 | 114.99±47.24 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Minimum | 36.45±24.02 | 50.93±32.45 | <0.01 | 42.38±26.45 | 49.90±31.47 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.72 |

| Range | 168.28±30.61 | 173.77±33.03 | <0.01 | 123.32±31.51 | 136.69±35.74 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Robust Mean Absolute Deviation | 15.61±7.27 | 15.86±7.05 | 0.30 | 8.45±3.56 | 17.06±125.90 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Root Mean Squared | 114.22±47.51 | 137.05±55.11 | <0.01 | 126.67±61.75 | 318.86±2896.58 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Skewness | -0.07±0.49 | -0.16±0.52 | <0.01 | 0.27±0.40 | 0.13±0.61 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Total Energy | 7.4e06±12.1e06 | 7.7e07±9.2e07 | <0.01 | 2.03±0.83 | 2.25±0.80 | <0.01 | 0.002 | <0.01 |

| Uniformity | 0.28±0.24 | 0.28±0.23 | 0.57 | 2.78±1.10 | 3.06±1.00 | <0.01 | 0.002 | <0.01 |

| Variance | 847.11±450.33 | 909.01±487.52 | 0.01 | 390.73±259.20 | 527.15±383.76 | 0.001 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| ORIGINAL GREY LEVEL CO-OCCURRENCE MATRIX | ||||||||

| Autocorrelation | 30.57±12.92 | 35.96±15.14 | <0.01 | 15.37±8.32 | 21.02±12.88 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Cluster Prominence | 217.25±244.25 | 255.03±303.92 | 0.01 | 49.61±75.21 | 105.46±227.63 | 0.001 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Cluster Shade | -2.09±16.92 | -5.46±19.86 | <0.01 | 1.14±4.88 | 0.99±14.87 | 0.05 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Cluster Tendency | 8.04±4.46 | 8.63±4.82 | 0.02 | 3.51±2.48 | 4.82±3.77 | 0.001 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Contrast | 0.65±0.17 | 0.64±0.16 | 0.34 | 0.67±0.26 | 0.66±0.21 | 0.72 | 0.88 | 0.01 |

| Correlation | 0.81±0.10 | 0.82±0.10 | 0.02 | 0.62±0.15 | 0.67±0.16 | 0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Difference Average | 0.53±0.12 | 0.53±0.11 | 0.34 | 0.53±0.15 | 0.54±0.13 | 0.72 | 0.97 | 0.03 |

| Difference Entropy | 1.21±0.16 | 1.21±0.15 | 0.30 | 1.21±0.19 | 1.21±0.20 | 0.65 | 0.94 | 0.04 |

| Difference Variance | 0.35±0.07 | 0.35±0.06 | 0.31 | 0.36±0.11 | 0.36±0.09 | 0.63 | 0.83 | 0.01 |

| Id | 0.75±0.05 | 0.75±0.05 | 0.33 | 0.75±0.06 | 0.75±0.06 | 0.73 | 0.98 | 0.05 |

| Idm | 0.74±0.05 | 0.75±0.05 | 0.33 | 0.75±0.06 | 0.74±0.06 | 0.73 | 0.99 | 0.05 |

| Idmn | 0.99±0.003 | 0.99±0.003 | 0.01 | 0.99±0.01 | 0.99±0.01 | 0.003 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Idn | 0.95±0.01 | 0.95±0.01 | 0.01 | 0.94±0.01 | 0.94±0.02 | 0.07 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Imc1 | -0.34±0.11 | -0.35±0.10 | 0.07 | -0.21±0.10 | -0.25±0.13 | 0.02 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Imc2 | 0.88±0.09 | 0.89±0.09 | 0.03 | 0.71±0.14 | 0.75±0.15 | 0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Inverse Variance | 0.44±0.08 | 0.44±0.07 | 0.26 | 0.44±0.08 | 0.44±0.08 | 0.67 | 0.86 | 0.05 |

| Joint Energy | 0.09±0.08 | 0.09±0.07 | 0.15 | 0.14±0.08 | 0.13±0.12 | 0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Joint Entropy | 4.03±0.58 | 4.08±0.58 | 0.05 | 3.44±0.66 | 3.60±0.73 | 0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Maximum Probability | 0.17±0.10 | 0.17±0.10 | 0.31 | 0.25±0.12 | 0.23±0.14 | 0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| MCC | 0.83±0.10 | 0.84±0.10 | 0.26 | 0.64±0.15 | 0.69±0.16 | 0.004 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Sum Average | 10.44±2.45 | 11.36±2.62 | <0.01 | 7.38±2.05 | 8.56±2.58 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Sum Entropy | 3.32±0.47 | 3.37±0.47 | 0.02 | 2.74±0.48 | 2.88±0.58 | 0.003 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Sum Squares | 2.17±1.12 | 2.32±1.21 | 0.02 | 1.04±0.64 | 1.37±0.95 | 0.002 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| ORIGINAL GREY LEVEL DEPENDENCE MATRIX | ||||||||

| Dependence Entropy | 5.28±0.55 | 5.34±0.52 | 0.02 | 4.75±0.45 | 4.86±0.68 | 0.004 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Dependence Non-Uniformity | 9.4e041.6e05 | 7.0e04±1.1e05 | 0.11 | 1.5e04±1.0e04 | 3.0e04±5.0e04 | 0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Dependence Non-Uniformity Normalized | 0.15±0.06 | 0.15±0.05 | 0.02 | 0.15±0.01 | 0.16±0.08 | 0.45 | 0.06 | <0.01 |

| Dependence Variance | 3.87±0.58 | 3.91±0.56 | 0.20 | 3.83±0.57 | 3.76±0.59 | 0.45 | 0.50 | <0.01 |

| Grey Level Non-Uniformity | 1.2e05±2.0e05 | 9.5e04±1.2e05 | 0.07 | 3.2e04±2.e04 | 4.9e04±6.9e04 | 0.07 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Grey Level Variance | 2.19±1.12 | 2.35±1.22 | 0.01 | 1.06±0.65 | 1.40±0.96 | 0.001 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| High Grey Level Emphasis | 30.76±12.90 | 36.07±15.10 | <0.01 | 15.61±8.33 | 21.22±12.85 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Large Dependence Emphasis | 30.50±8.78 | 30.36±7.82 | 0.60 | 30.38±9.21 | 29.98±9.68 | 0.78 | 0.46 | 0.002 |

| Large Dependence High Grey Level Emphasis | 873.08±478.04 | 1.1e04±614.43 | <0.01 | 410.34±183.74 | 600.31±519.30 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Large Dependence Low Grey Level Emphasis | 3.27±7.41 | 2.18±5.21 | <0.01 | 4.51±5.23 | 4.06±9.19 | 0.02 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Low Grey Level Emphasis | 0.08±0.10 | 0.06±0.07 | <0.01 | 0.13±0.10 | 0.11±0.13 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Small Dependence Emphasis | 0.10±0.02 | 0.10±0.02 | 0.30 | 0.11±0.03 | 0.11±0.03 | 0.86 | 0.47 | <0.01 |

| Small Dependence High Grey Level Emphasis | 3.39±1.36 | 3.69±1.46 | <0.01 | 1.92±1.21 | 2.41±1.33 | 0.002 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Small Dependence Low Grey Level Emphasis | 0.01±0.004 | 0.01±0.004 | <0.01 | 0.01±0.01 | 0.01±0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Grey Level Non Uniformity | 5.5e04±8.3e04 | 4.1e04±4.2e04 | 0.07 | 1.3e04±827.18 | 2.0e04±2.1e04 | 0.05 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Long Run High Grey Level Emphasis | 272.04±425.63 | 397.21±1.2e04 | <0.01 | 106.65±54.98 | 444.08±4.6e04 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| ORIGINAL GREY LEVEL RUN LENGTH MATRIX | ||||||||

| grey Level Non Uniformity | 5.5e04±8.2e04 | 4.1e04±4.2e04 | 0.07 | 1.3e04±827.18 | 2.0e04±2.1e04 | 0.05 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Grey Level Non Uniformity Normalized | 0.21±0.05 | 0.20±0.06 | <0.01 | 0.28±0.07 | 0.25±0.07 | 0.001 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Grey Level Variance | 2.19±0.93 | 2.39±1.06 | <0.01 | 1.21±0.62 | 1.58±1.08 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| High Grey Level Run Emphasis | 31.51±12.06 | 35.41±13.87 | <0.01 | 16.04±8.09 | 21.50±11.83 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Long Run Emphasis | 36.06±282.73 | 31.10±345.22 | 0.74 | 9.69±8.68 | 39.45±256.91 | 0.84 | 0.27 | <0.01 |

| Long Run High Grey Level Emphasis | 272.04±425.63 | 397.21±1258.60 | <0.01 | 106.65±54.98 | 444.08±4.6e04 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Long Run Low Grey Level Emphasis | 26.82±279.81 | 16.69±271.07 | <0.01 | 1.87±4.10 | 29.23±252.66 | 0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Low Grey Level Run Emphasis | 0.07±0.07 | 0.06±0.05 | <0.01 | 0.13±0.10 | 0.11±0.10 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Run Entropy | 4.52±0.39 | 4.56±0.37 | 0.01 | 4.07±0.32 | 4.19±0.44 | 0.03 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Run Length Non Uniformity | 1.0e05±1.4e05 | 8.0e04±7.6e04 | 0.08 | 1.8e04±1.4e04 | 3.3e04±3.8e04 | 0.003 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Run Length Non Uniformity Normalized | 0.36±0.05 | 0.36±0.05 | 0.29 | 0.36±0.07 | 0.36±0.07 | 0.74 | 0.79 | 0.01 |

| Run Percentage | 0.49±0.09 | 0.49±0.08 | 0.60 | 0.49±0.10 | 0.49±0.10 | 0.79 | 0.48 | 0.002 |

| Run Variance | 26.34±229.73 | 17.50±193.11 | 0.79 | 4.64±5.54 | 25.75±188.11 | 0.86 | 0.22 | <0.01 |

| Short Run Emphasis | 0.62±0.05 | 0.62±0.05 | 0.26 | 0.61±0.07 | 0.62±0.07 | 0.75 | 0.81 | 0.01 |

| Short Run High Grey Level Emphasis | 19.79±7.39 | 21.75±8.28 | <0.01 | 10.37±5.66 | 13.62±7.33 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Short Run Low Grey Level Emphasis | 0.04±0.03 | 0.03±0.03 | <0.01 | 0.08±0.05 | 0.06±0.05 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| GREY LEVEL SIZE ZONE MATRIX | ||||||||

| Grey Level Non Uniformity | 795.79±1201.62 | 585.19±669.72 | 0.09 | 180.04±117.67 | 272.46±283.88 | 0.03 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Grey Level Non Uniformity Normalized | 0.17±0.05 | 0.17±0.05 | <0.01 | 0.23±0.08 | 0.21±0.07 | 0.001 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Grey Level Variance | 2.92±0.87 | 3.16±1.00 | <0.01 | 2.02±0.71 | 2.37±0.94 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| High Grey Level Zone Emphasis | 32.50±11.76 | 35.23±13.35 | <0.01 | 17.16±7.70 | 22.20±11.14 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Large Area Emphasis | 1.9e06±1.4e07 | 1.8e06±2.2e07 | 0.17 | 2.0e05±3.1e05 | 8.6e05±5.4e06 | 0.59 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Large Area High Grey Level Emphasis | 2.8e07±9.4e07 | 2.5e07±8.9e07 | 0.07 | 1.8e06±1.6e06 | 1.7e07±.20e08 | 0.001 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Large Area Low Grey Level Emphasis | 1.2e06±1.3e07 | 1.0e06±2.0e07 | <0.01 | 4.8e04±2.1e05 | 5.4e05±5.1e06 | 0.27 | 0.34 | 0.58 |

| Low Grey Level Zone Emphasis | 0.08±0.08 | 0.07±0.06 | 0.01 | 0.16±0.10 | 0.13±0.11 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Size Zone Non Uniformity | 1.7e04±2.4e04 | 1.3e04±1.3e04 | 0.11 | 300.70±230.42 | 525.89±609.14 | 0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Size Zone Non Uniformity Normalized | 0.36±0.03 | 0.35±0.03 | <0.01 | 0.34±0.03 | 0.34±0.04 | 0.70 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Small Area Emphasis | 0.62±0.02 | 0.61±0.02 | <0.01 | 0.60±0.03 | 0.60±0.05 | 0.76 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Small Area High Grey Level Emphasis | 20.27±7.39 | 21.78±8.29 | 0.002 | 10.47±4.60 | 13.51±6.94 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Small Area Low Grey Level Emphasis | 0.05±0.04 | 0.04±0.04 | 0.003 | 0.10±0.06 | 0.08±0.07 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Zone Entropy | 5.05±0.34 | 5.17±0.39 | <0.01 | 4.72±0.40 | 4.85±0.47 | 0.004 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Zone Percentage | 0.08±0.02 | 0.08±0.02 | 0.40 | 0.09±0.03 | 0.09±0.03 | 0.89 | 0.16 | <0.01 |

| Zone Variance | 1.9e06±1.4e07 | 1.7e06±2.0e07 | 0.17 | 2.0e05±3.1e05 | 8.1e05±5.2e06 | 0.59 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| ORIGINAL NEIGHBOURING GREY TONE DIFFERENCE MATRIX | ||||||||

| Busyness | 89.95±124.85 | 65.62±74.74 | 0.53 | 58.52±136.42 | 47.20±45.30 | 0.86 | 0.002 | <0.01 |

| Coarseness | 0.001±0.001 | 0.001±0.002 | 0.07 | 0.001±0.001 | 0.002±0.01 | 0.05 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Complexity | 17.62±6.14 | 18.87±6.97 | <0.01 | 11.01±5.84 | 12.91±6.18 | 0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Contrast | 0.02±0.01 | 0.02±0.01 | 0.55 | 0.02±0.01 | 0.02±0.01 | 0.40 | 0.002 | <0.01 |

| Strength | 0.02±0.02 | 0.02±0.02 | 0.85 | 0.03±0.02 | 0.03±0.07 | 0.54 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| ORIGINAL SHAPE | ||||||||

| Elongation | 0.71±0.17 | 0.70±0.17 | 0.09 | 0.45±0.21 | 0.48±0.22 | 0.18 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Major AxisLength | 29.43±23.74 | 28.41±17.51 | 0.01 | 28.68±19.45 | 32.47±26.12 | 0.57 | 0.98 | 0.86 |

| Maximum 2D Diameter Column | 21.33±13.40 | 21.17±9.64 | 0.01 | 12.54±8.65 | 14.94±11.24 | 0.19 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Maximum 2D Diameter Row | 24.79±19.16 | 24.30±13.49 | <0.01 | 16.71±11.58 | 21.50±17.36 | 0.05 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Maximum2D Diameter Slice | 29.27±21.33 | 29.11±15.32 | <0.01 | 24.51±14.66 | 29.09±21.14 | 0.20 | 0.11 | 0.01 |

| Maximum 3D Diameter | 29.27±21.33 | 29.11±15.32 | <0.01 | 24.51±14.66 | 29.09±21.14 | 0.20 | 0.11 | 0.01 |

| Mesh Volume | 561.78±916.62 | 419.69±527.64 | 0.05 | 91.54±60.56 | 166.03±209.15 | 0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Minor Axis Length | 19.46±13.31 | 18.41±8.79 | 0.05 | 10.79±7.01 | 13.36±11.04 | 0.18 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Sphericity | 0.35±0.11 | 0.32±0.07 | <0.01 | 0.43±0.08 | 0.41±0.11 | 0.03 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Surface Area | 1.2e04±1.9e04 | 945.31±1.1e04 | 0.01 | 242.55±151.84 | 406.97±459.46 | 0.02 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Surface Volume Ratio | 2.30±0.21 | 2.38±0.28 | <0.01 | 2.75±0.26 | 2.68±0.36 | 0.002 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Voxel Volume | 563.50±917.69 | 421.96±528.31 | 0.04 | 92.83±61.20 | 167.65±210.00 | 0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Predictors | Mass radiomics | Lymph node radiomics | Mass & lymph node radiomics | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classifiers | Sn | Sp | Acc | Sn | Sp | Acc | Sn | Sp | Acc | |

| TRAINING DATASET | ||||||||||

| CatBoost Classifier | 0.951 | 0.962 | 0.954 | 0.941 | 0.965 | 0.946 | 0.973 | 0.951 | 0.960 | |

| XGBoost Classifier | 0.956 | 1.000 | 0.968 | 0.986 | 0.860 | 0.960 | 0.970 | 1.000 | 0.977 | |

| Decision Tree | 1.000 | 0.865 | 0.940 | 1.000 | 0.860 | 0.971 | 1.000 | 0.885 | 0.972 | |

| Mean±SD | 0.969±0.022 | 0.942±0.057 | 0.954±0.011 | 0.976±0.025 | 0.895±0.049 | 0.959±0.010 | 0.981±0.013 | 0.945±0.047 | 0.970±0.007 | |

| VALIDATION DATASET | ||||||||||

| CatBoost Classifier | 0.974 | 0.901 | 0.956 | 0.955 | 0.968 | 0.958 | 0.975 | 0.990 | 0.978 | |

| XGBoost Classifier | 0.990 | 0.961 | 0.991 | 1.000 | 0.930 | 0.992 | 0.975 | 1.000 | 0.980 | |

| Decision Tree | 0.999 | 0.859 | 0.965 | 1.000 | 0.960 | 0.992 | 0.997 | 0.962 | 0.990 | |

| Mean±SD | 0.988±0.010 | 0.907±0.042 | 0.971±0.015 | 0.985±0.021 | 0.953±0.016 | 0.981±0.016 | 0.982±0.010 | 0.984±0.016 | 0.983±0.005 | |

| Classification | Sensitivity | Specificity | Accucary |

|---|---|---|---|

| TRAINING DATASET | |||

| LABC vs others | 0.908 | 0.433 | 0.818 |

| LBBC vs others | 0.850 | 0.487 | 0.783 |

| TNBC vs others | 0.577 | 0.672 | 0.628 |

| HER2 vs others | 0.948 | 0.267 | 0.891 |

| VALIDATION DATASET | |||

| LABC vs others | 0.967 | 1.000 | 0.974 |

| LBBC vs others | 0.935 | 0.571 | 0.868 |

| TNBC vs others | 0.944 | 0.800 | 0.868 |

| HER2 vs others | 0.914 | 1.000 | 0.921 |

| Cite | Year | Database | Sample size | Classification | Imaging modality |

Classifier | Metrics, % | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | Sensitivity | Specificity | |||||||

| DETECTION OF MALIGNANT BREAST MASSES | |||||||||

| [50] | 2022 | Baheya Hospital for Early Detection & Treatment of Women’s Cancer [58] |

487 : 357 : 212 | benign vs malignant tumours vs normal breast tissue |

Ultrasound | CNN | 87.76 | 87.62 | – |

| [51] | 2017 | Seoul National University Hospital |

78 : 78 | benign vs malignant tumour |

Ultrasound | Logistic regression |

81.41 | 83.33 | 79.49 |

| [52] | 2023 | Baheya Hospital for Early Detection & Treatment of Women’s Cancer [58] |

5000 : 5000 | benign vs malignant tumour |

Ultrasound | Inception V3 ResNet50 DenseNet121 Ensemble |

83.00 88.00 84.00 90.00 |

74.00 82.00 79.00 84.00 |

– – – – |

| [53] | 2021 | Cancer Center of Sun Yat-sen University |

946 : 1048 | benign vs malignant tumour |

Ultrasound | DCNN | 90.78 | 91.18 | 90.44 |

| [54] | 2017 | The Johns Hopkins School of Medicine Hospital |

26 : 98 | benign vs malignant tumour |

DCE-MRI | IsoSVM RBFSVM Linear SVM Quadratic SVM Cubic SVM |

– – – – – |

93.00 80.00 85.00 85.00 93.00 |

85.00 77.00 62.00 54.00 55.00 |

| [55] | 2019 | First Hospital of Shanxi Medical University |

1011 : 1031 | benign vs malignant tumour |

Mammo- graphy |

AlexNet VGGNet GooLeNet DenseNet DenseNet-II |

92.70 92.78 93.54 93.87 94.55 |

93.60 93.58 93.90 94.59 95.60 |

91.78 92.42 93.17 93.90 95.36 |

| [56] | 2015 | MIAS [59] | 32 : 16 | benign vs malignant tumour |

Mammo- graphy |

Adaboost BPNN SRC |

81.25 77.08 93.75 |

78.12 75.00 90.62 |

87.50 81.25 99.99 |

| [57] | 2023 | MIAS [59] | 322 cases | benign vs malignant tumour |

Mammo- graphy |

SVM RF ANN k-NN NB DT |

94.10 97.00 93.50 82.30 70.60 94.10 |

93.70 100.00 92.90 100.00 100.00 100.00 |

97.30 94.70 92.00 66.70 54.50 88.80 |

| IDENTIFICATION OF LYMPH NODE METASTASES | |||||||||

| [60] | 2021 | Keimyung University Dongsan Hospital |

43 : 57 | benign vs malignant lymphadenopathy in ALN |

PET/CT | XGBoost | 77.00 | 55.80 | 93.00 |

| [61] | 2021 | National Taiwan University Hospital |

59 : 94 | benign vs malignant lymphadenopathy in ALN |

Ultrasound | Logistic regression SVM XGBoost DenseNet-121 |

71.90 66.01 69.93 81.05 |

54.24 52.54 50.84 81.36 |

82.98 74.47 80.85 80.85 |

| [62] | 2020 | Guangdong Provincial People’s Hospital |

134 : 214 | benign vs malignant lymphadenopathy in SLN |

CT | CNN-Fast | 67.70 | 82.50 | 58.40 |

| [63] | 2023 | Three hospitals in Zhejiang | 234 : 754 | benign vs malignant lymphadenopathy in SLN |

DCE-MRI | CNN - raw images Radiomics models |

89.20 82.60 |

75.50 60.00 |

88.30 54.40 |

| [64] | 2023 | Luzhou Medical College Affiliated Hospital |

400 : 400 | benign vs malignant lymphadenopathy in ALN |

CE-CT | DA-VGG19 | 90.88 | 95.00 | 86.75 |

| [65] | 2021 | Sun Yat-sen Hospital & Cancer Center |

328 : 475 | benign vs malignant lymphadenopathy in ALN |

DCE-MRI | SVM | 78.00 | 86.00 | 69.00 |

| [66] | 2020 | Two Affiliated Hospitals of Harbin Medical University |

821 : 263 | benign vs malignant lymphadenopathy in SLN and NSLN |

Ultrasound | DenseNet | 67.30 80.20 |

89.70 98.40 |

47.60 39.30 |

| [67] | 2022 | Two Affiliated Hospitals of Harbin Medical University |

94 : 109 | pN0 vs pN1 stage | PET | LASSO | 59.78 | 84.21 | 40.82 |

|

Acronyms: - artificial neural network; - Back Propogation Neural Network;

- contrast-enhanced CT;

- convolutional neural network; - deformable attention VGG19; - dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI; - deep convolutional neural network; - Dense Convolutional Network; - decision tree; - hybrid isomap and support vector machine; - k-Nearest Neighbour; - least absolute shrinkage and selection operator; - machine learning; - naive Bayes; - Radial basis function SVM - random forest; - sparse representation based classifier; - support vector machine; | |||||||||

| Cite | Year | Database | Sample size | Classification | Imaging modality |

Classifier | Metrics, % | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | Sensitivity | Specificity | |||||||

| DETECTION OF MALIGNANT BREAST MASSES | |||||||||

| [28] | 2021 | MIAS [59] INbreast database [24] |

322 : 208 | benign vs malignant tumour |

Mammo- graphy |

AlexNet GoogLeNet Resnet50 Vgg19 |

88.66 91.97 87.12 91.16 |

83.40 87.83 80.52 91.16 |

96.52 97.60 95.63 97.66 |

| [30] | 2017 | Zhejiang Cancer Hospital |

66 : 77 | benign vs malignant tumour |

DCE-MRI | 2D CNN 3D CNN |

64.40 70.50 |

70.10 80.50 |

58.00 61.80 |

| IDENTIFICATION OF LYMPH NODE METASTASES | |||||||||

| [68] | 2020 | Tongji Hospital Hubei Cancer Hospital |

347 : 337 | benign vs malignant lymphadenopathy in ALN |

Ultrasound | Inception V3 InceptionResNetV2 V2 ResNet-101 |

80.00 82.00 78.00 |

82.00 80.00 78.00 |

79.00 85.00 79.00 |

| [69] | 2022 | Breast Imaging Section Columbia University Medical Center |

105 : 64 | benign vs malignant lymphadenopathy in ALN |

Ultrasound | CNN | 72.60 | 65.50 | 78.90 |

|

Acronyms: - axillary lymph node;

- convolutional neural network;

- dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI; - Mammographic Image Analysis Society | |||||||||

| Cite | Year | Database | Sample size | Classification | Imaging modality |

Classifier | Metrics, % | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | Sensitivity | Specificity | |||||||

| [70] | 2020 | Severance Hospital | TN: 62 HER2: 59 luminal: 100 |

TN vs. non-TN HER2 vs. non-HER2 luminal vs. non-luminal |

DBT | N/A | 80.30 70.4 50.70 |

83.30 11.10 44.00 |

79.70 79.00 66.70 |

| [71] | 2024 | Third Affiliated Hospital of Soochow University Fudan University Shanghai Cancer Center |

TN: 55 HER2: 55 luminal: 276 |

TN vs. non-TN HER2 vs. non-HER2 luminal vs. non-luminal |

contrast-enhanced mammography |

SVM | 75.00 83.00 72.00 |

50.00 38.00 75.00 |

78.00 98.00 67.00 |

| [72] | 2022 | First Affiliated Hospital of Soochow University Suzhou Municipal Hospital |

TN: 65 : 254 | TN vs. non-TN | mammography | Binary logistic backward stepwise regression |

80.60 | 72.00 | 80.70 |

| [73] | 2021 | Tianjin Medical University Cancer Institute and Hospital |

TN: 41 HER2: 45 LABC: 20 LBBC(HER2-): 106 LBBC(HER2+): 61 |

TN vs. Non-TN HER2 + vs. HER2 - Luminal vs. Non-Luminal |

18 F-FDG PET/CT | N/A | 89.30 84.70 86.40 |

93.30 90.80 80.10 |

83.90 76.40 90.50 |

| [74] | 2019 | Henan Provincial People’s Hospital |

HER2+: 227 HER2-:79 |

HER2 + vs. HER2 - | mammography | SVM logistic regression |

73.00 77.00 |

60.86 73.91 |

68.75 68.75 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).