Submitted:

28 February 2025

Posted:

04 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

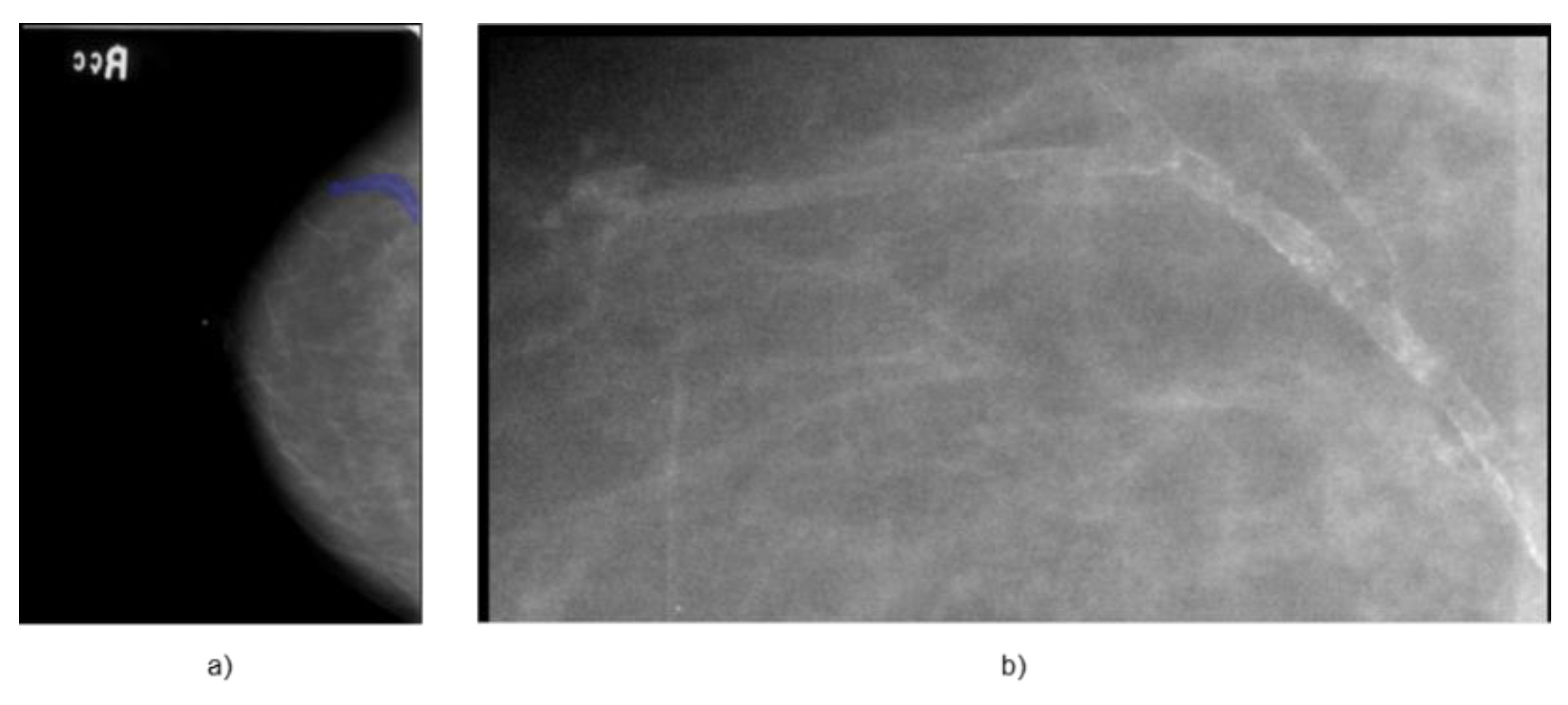

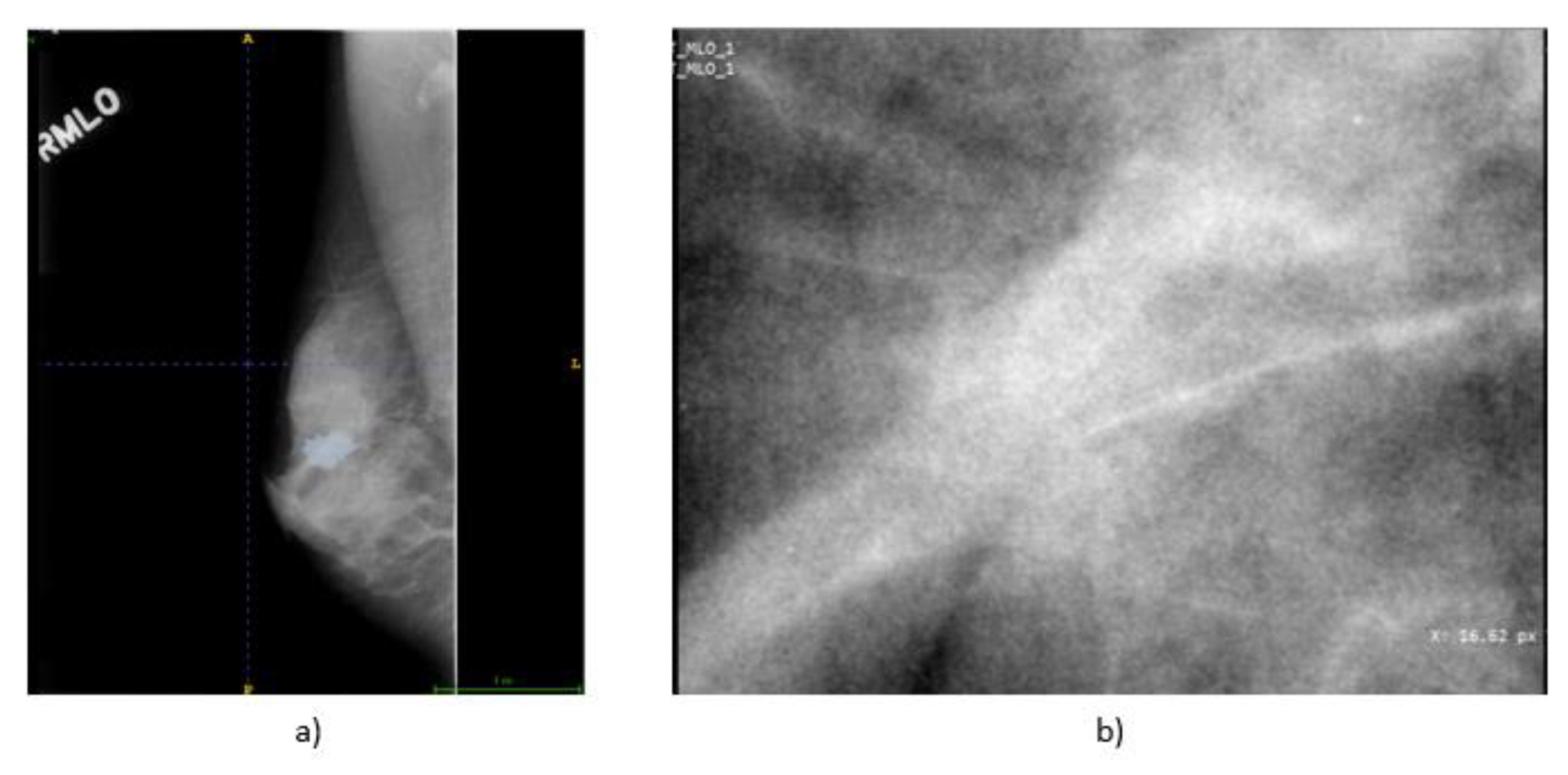

2.1. Datasets

2.1.1. Dataset for Internal Validation

2.1.2. Dataset for External Validation

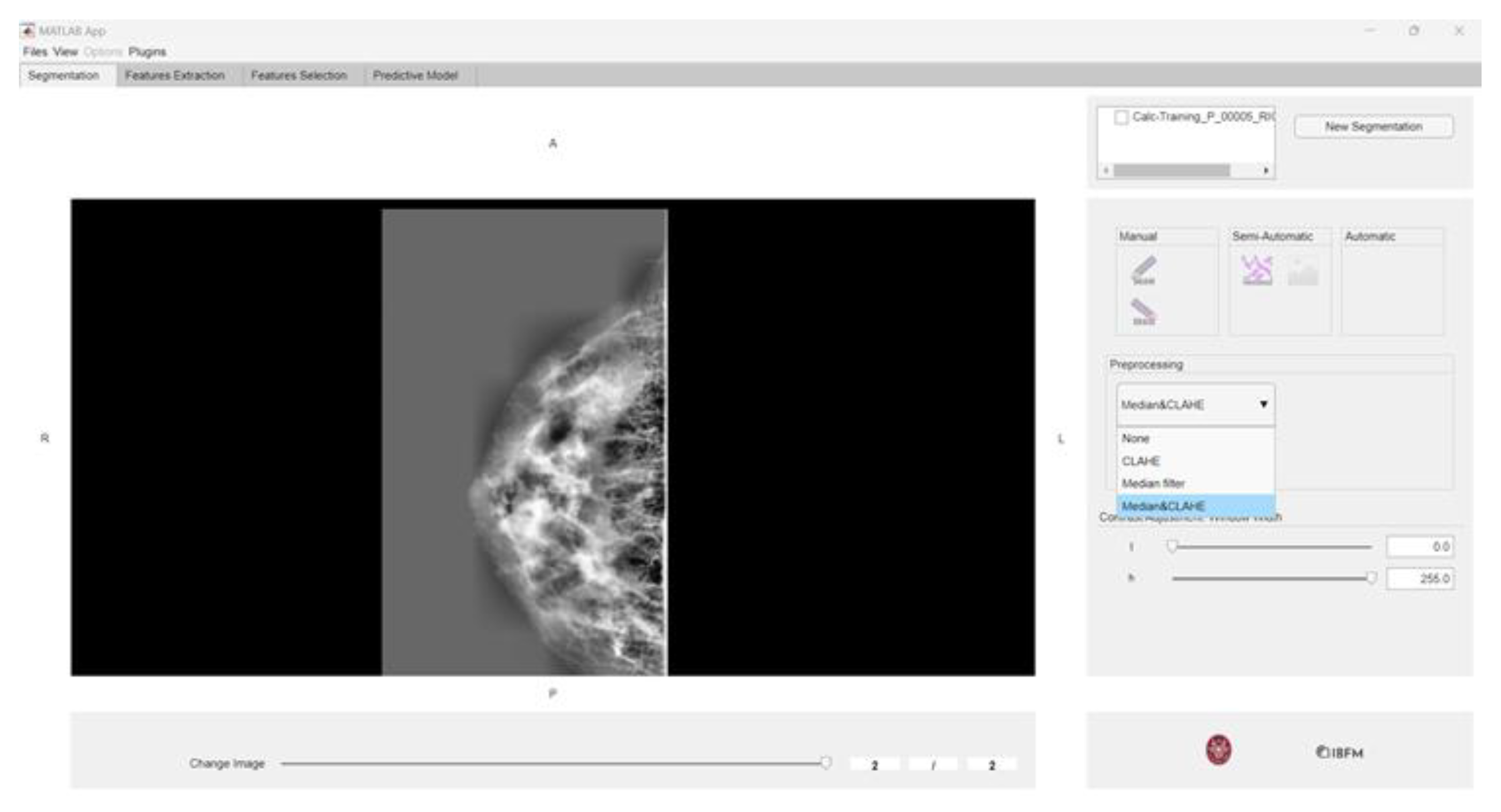

2.2. Toolbox for Radiomics Analysis: matRadiomics

2.3. Preprocessing

- Histogram calculation for each tile:

- 2.

- Clip limit application:

- 3.

- Local equalization:

2.4. Radiomics Features

- First-order features describe the intensity distribution within the region of interest (ROI), including metrics such as mean, standard deviation, skewness, and kurtosis.

- Second-order features analyze texture by assessing the spatial relationships between voxel intensities, capturing patterns that reflect tissue heterogeneity.

- Shape features define the geometry and morphology of the ROI, including volume, surface area, and sphericity. These are particularly useful for distinguishing lesions, as benign ones tend to be more regular, while malignant ones often exhibit irregular shapes.

2.4.1. Feature Extraction

2.4.2. Feature Selection

2.5. Machine Learning Predictive Models

2.5.1. Linear Discriminant Analysis

- Within-class scatter matrix (Sw): measures the variance within each class and should be minimized for optimal classification.

- Between-class scatter matrix (Sb): measures the variance between class means and should be maximized.

2.5.2. Support Vector Machine

2.6. Performance Metrics

- True Positives (TP): Positive examples correctly classified as positive.

- True Negatives (TN): Negative examples correctly classified as negative.

- False Positives (FP): Negative examples incorrectly classified as positive.

- False Negatives (FN): Positive examples incorrectly classified as negative.

- An AUC of 1 indicates perfect classification, where the model distinguishes all positive from negative instances.

- An AUC of 0 suggests a completely inverted classifier.

- An AUC of 0.5 indicates random guessing, with no predictive power.

2.7. Deep Radiomics

2.7.1. Implementation of EfficientnetB6

2.7.2. Dataset Preparation for the Neural Network

- Horizontal and vertical flips.

- Random translations and rotations (±20°).

- Brightness and contrast adjustments.

- Gaussian filtering and elastic deformations.

2.7.3. Model Training Configuration

3. Results

3.1. CBIS-DDSM Database

3.2. Preprocessing

3.3. Machine Learning-Based Radiomics

- -

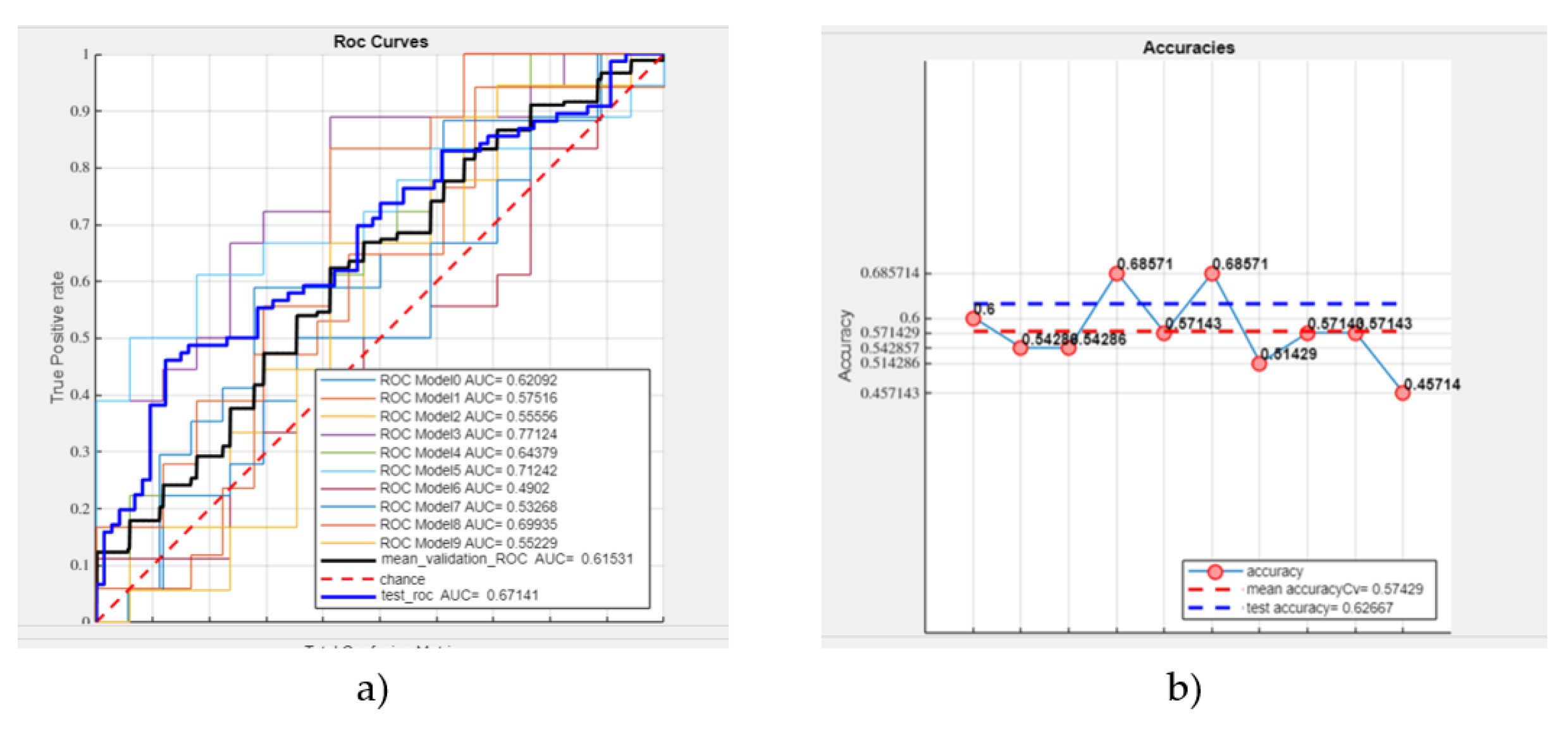

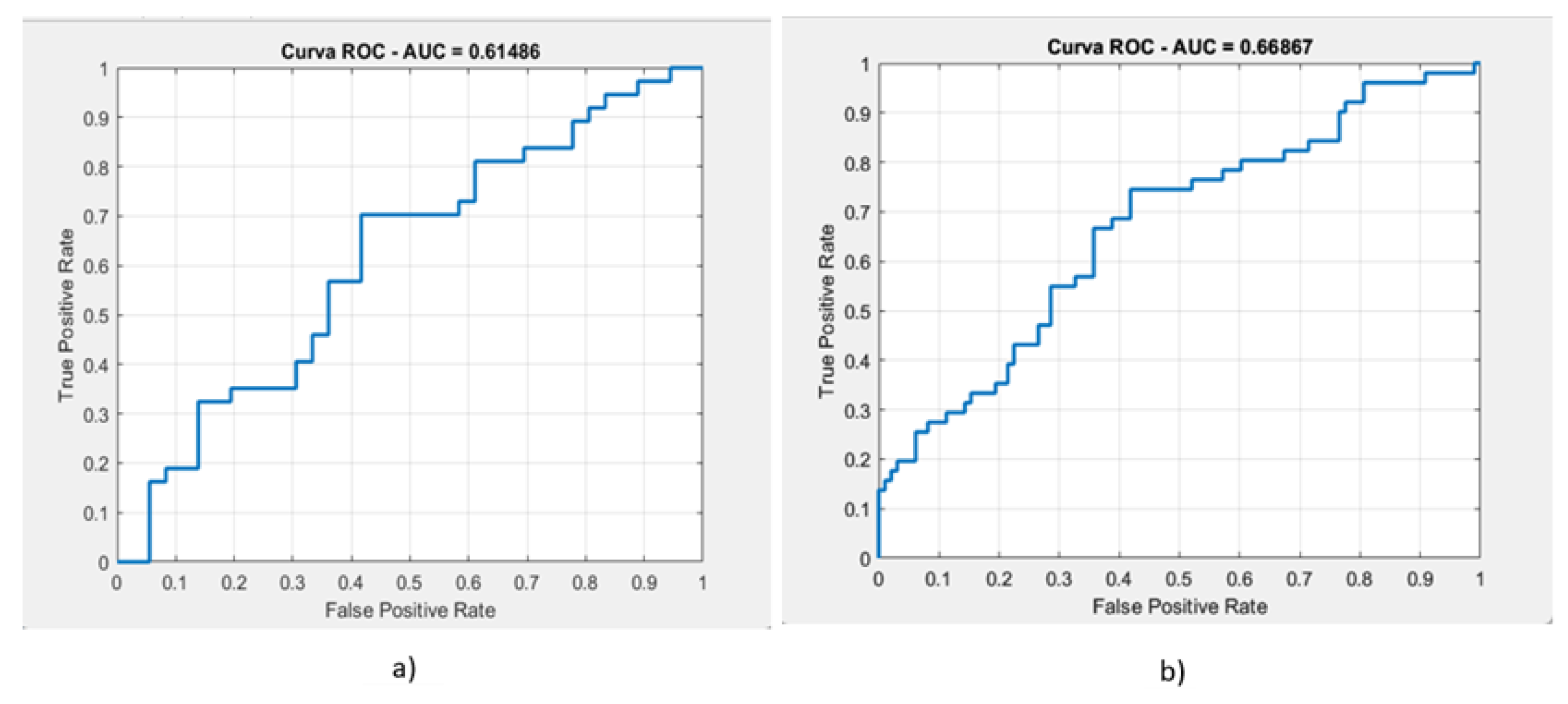

- A mean validation ROC AUC of 61.53%,

- -

- A test ROC AUC of 67.14%,

- -

- A mean accuracy of 57.43%,

- -

- A test accuracy of 62.67% (see Figure 5).

- -

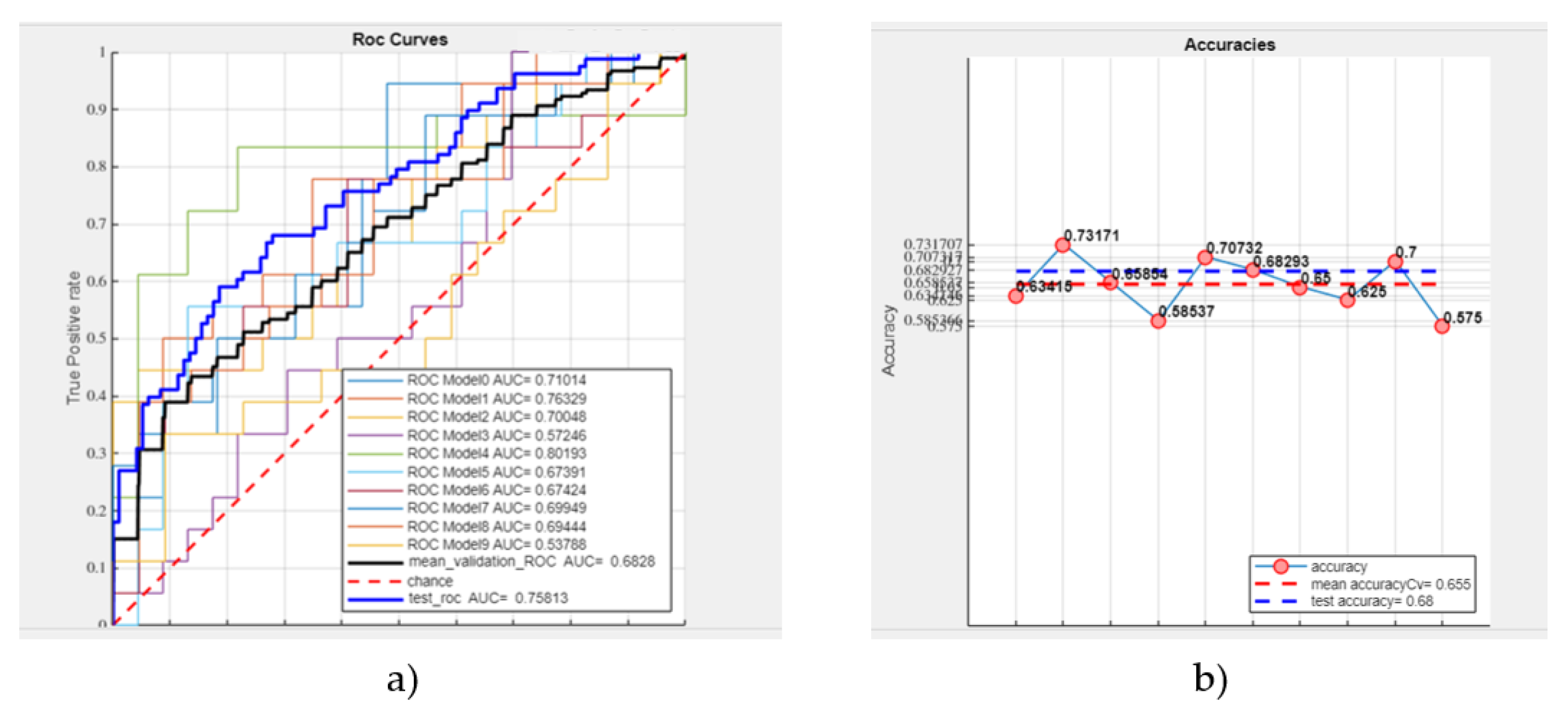

- Mean validation ROC AUC: 68.28%,

- -

- Test ROC AUC: 75.81%,

- -

- Mean accuracy: 65.50%,

- -

- Test accuracy: 68% (see Figure 6).

- -

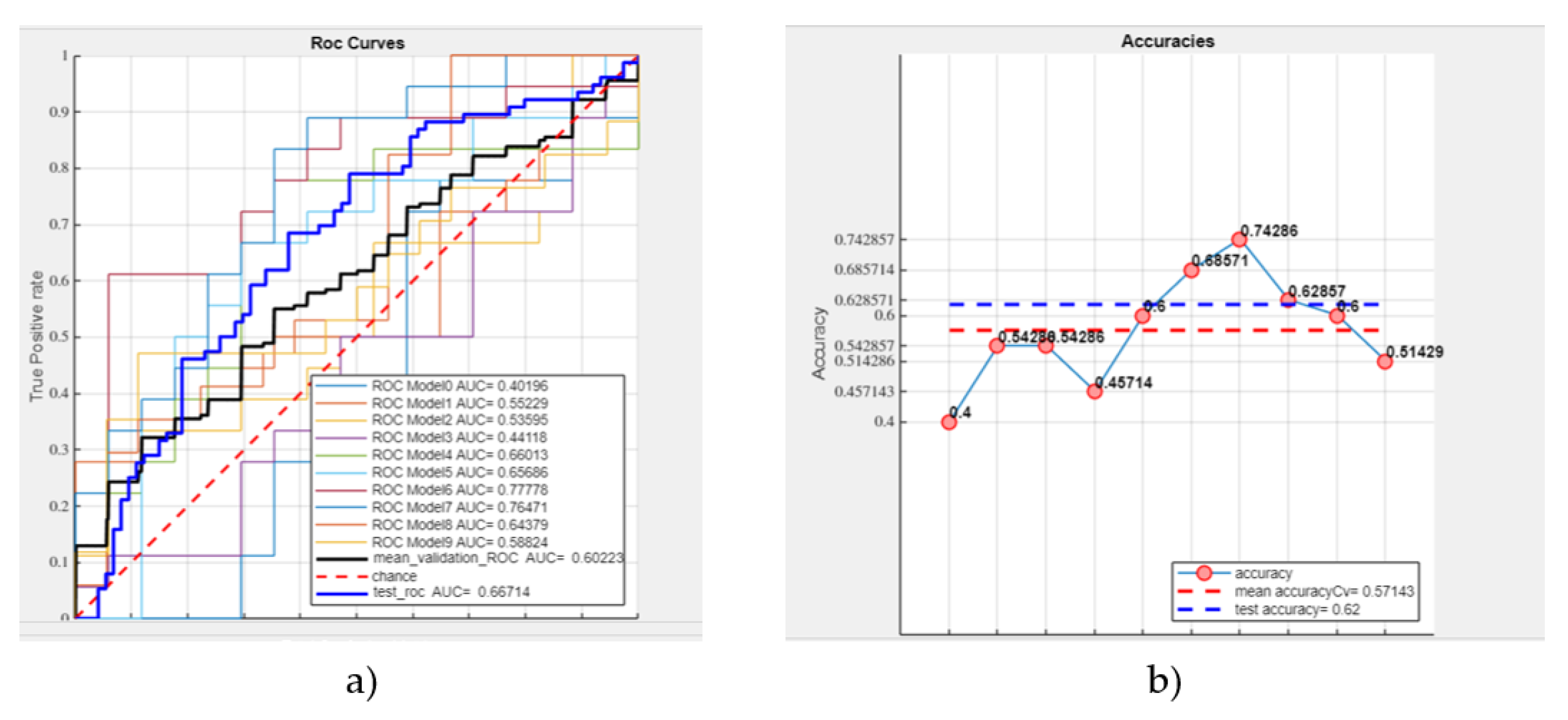

- Mean validation ROC AUC: 60.22%

- -

- Test ROC AUC: 66.7%

- -

- Mean accuracy: 57.14%

- -

- Test accuracy: 62% (see Figure 7).

- -

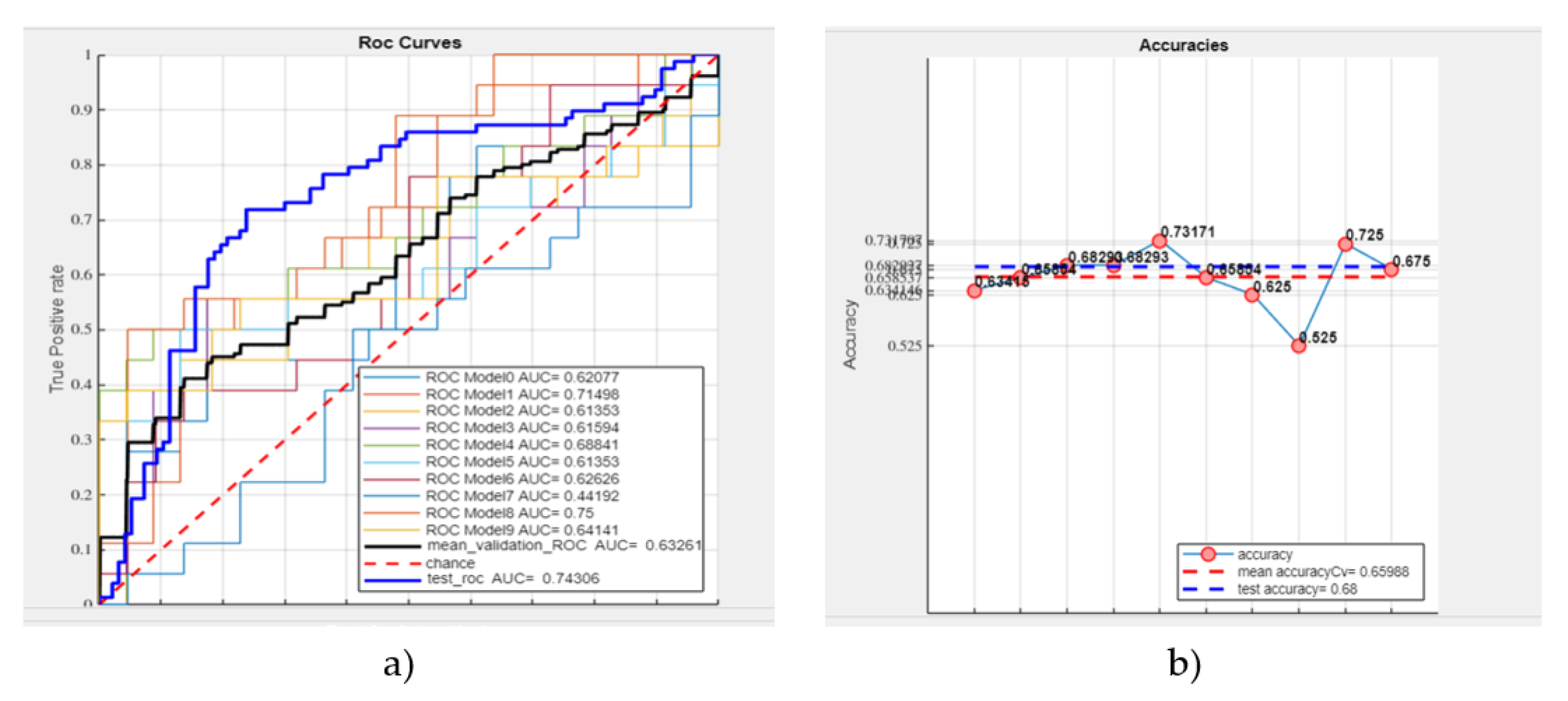

- Mean validation ROC AUC: 63.26%

- -

- Test ROC AUC: 74.31%

- -

- Mean accuracy: 65.99%

- -

- Test accuracy: 68% (see Figure 8).

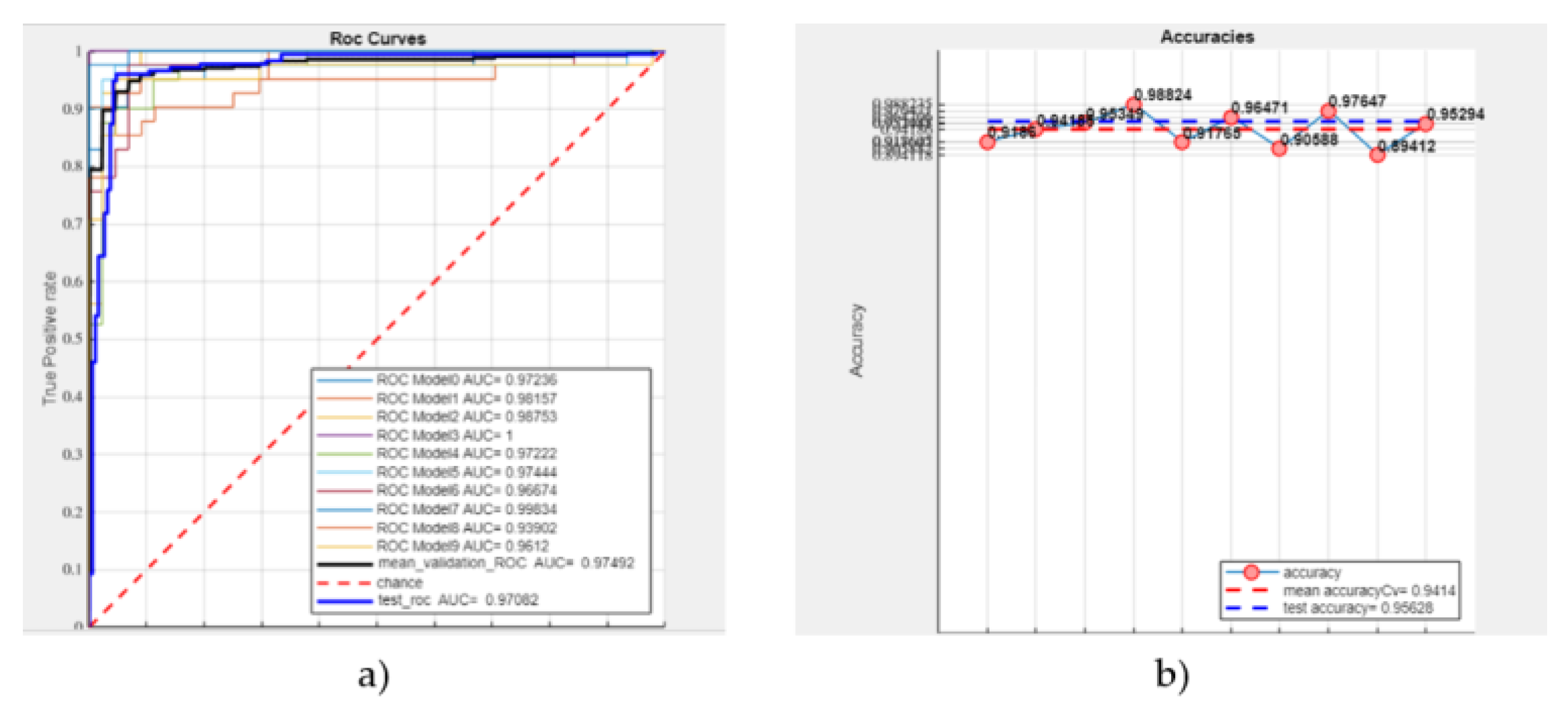

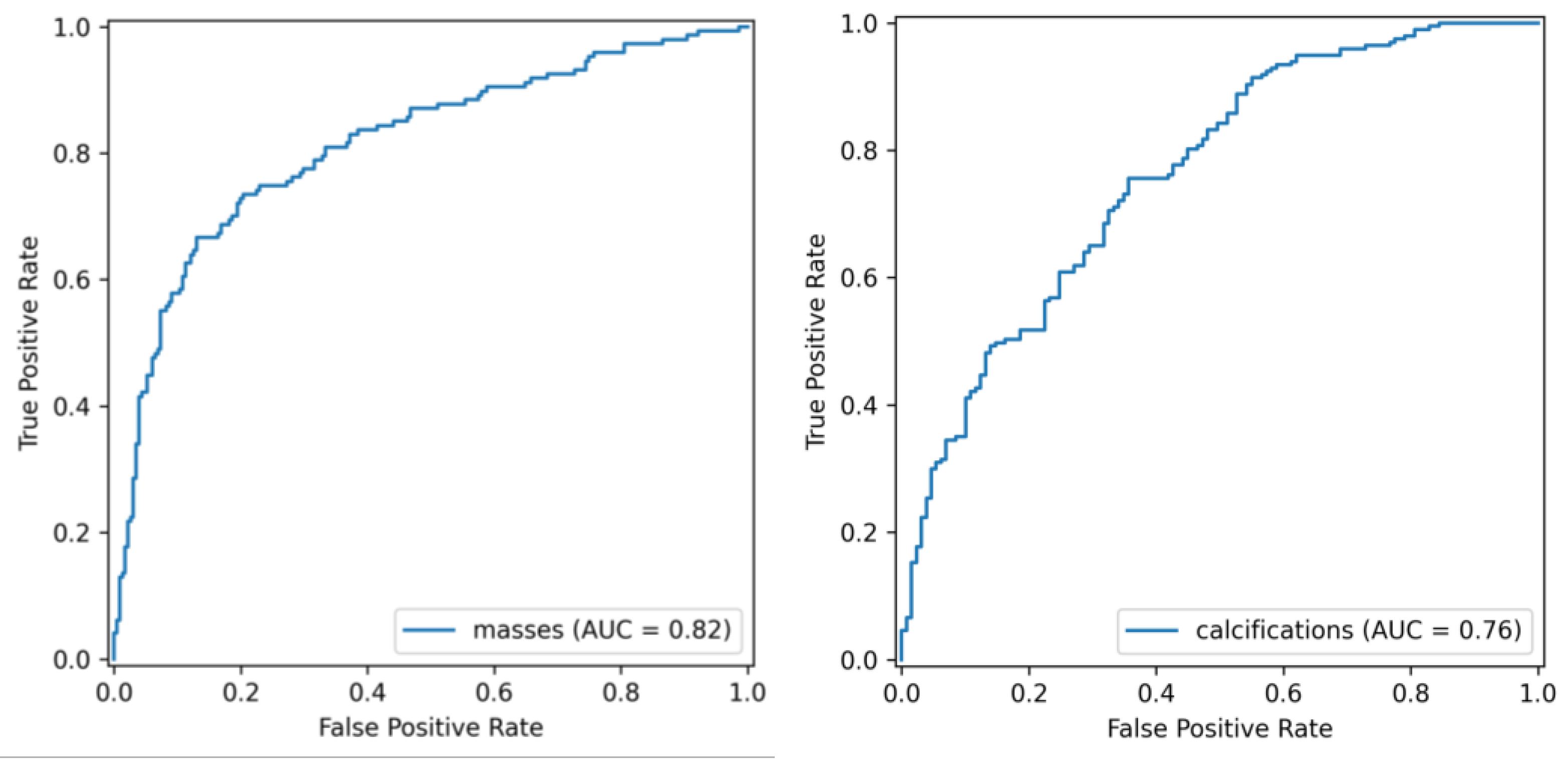

3.4. Deep Learning

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Benson, J.R.; Jatoi, I.; Keisch, M.; Esteva, F.J.; Makris, A.; Jordan, V.C. Early Breast Cancer. The Lancet 2009, 373, 1463–1479. [CrossRef]

- Carlson, R.W.; Allred, D.C.; Anderson, B.O.; Burstein, H.J.; Carter, W.B.; Edge, S.B.; Erban, J.K.; Farrar, W.B.; Forero, A.; Giordano, S.H.; et al. Invasive Breast Cancer. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network 2011, 9, 136–222. [CrossRef]

- Tan, P.H.; Ellis, I.; Allison, K.; Brogi, E.; Fox, S.B.; Lakhani, S.; Lazar, A.J.; Morris, E.A.; Sahin, A.; Salgado, R.; et al. The 2019 World Health Organization Classification of Tumours of the Breast. Histopathology 2020, 77, 181–185. [CrossRef]

- Muller, K.; Jorns, J.M.; Tozbikian, G. What’s New in Breast Pathology 2022: WHO 5th Edition and Biomarker Updates. J Pathol Transl Med 2022, 56, 170–171. [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Tran, T.X.M.; Song, H.; Park, B. Microcalcifications, Mammographic Breast Density, and Risk of Breast Cancer: A Cohort Study. Breast Cancer Research 2022, 24, 96. [CrossRef]

- Calisto, F.M.; Nunes, N.; Nascimento, J.C. BreastScreening. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the International Conference on Advanced Visual Interfaces; ACM: New York, NY, USA, September 28 2020; pp. 1–5.

- Sternlicht, M.D. Key Stages in Mammary Gland Development: The Cues That Regulate Ductal Branching Morphogenesis. Breast Cancer Research 2005, 8, 201. [CrossRef]

- Biswas, S.K.; Banerjee, S.; Baker, G.W.; Kuo, C.-Y.; Chowdhury, I. The Mammary Gland: Basic Structure and Molecular Signaling during Development. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23, 3883. [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Moy, L.; Heller, S.L. Digital Breast Tomosynthesis: Update on Technology, Evidence, and Clinical Practice. RadioGraphics 2021, 41, 321–337. [CrossRef]

- Richman, I.B.; Long, J.B.; Hoag, J.R.; Upneja, A.; Hooley, R.; Xu, X.; Kunst, N.; Aminawung, J.A.; Kyanko, K.A.; Busch, S.H.; et al. Comparative Effectiveness of Digital Breast Tomosynthesis for Breast Cancer Screening Among Women 40-64 Years Old. JNCI: Journal of the National Cancer Institute 2021, 113, 1515–1522. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Song, Y.; Chen, C.; Wang, Z.; Li, L.; Liu, M.; Liu, G.; Xu, Y.; Zhou, Y.; et al. Comparison of Ultrasound and Mammography for Early Diagnosis of Breast Cancer among Chinese Women with Suspected Breast Lesions: A Prospective Trial. Thorac Cancer 2022, 13, 3145–3151. [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.E.; Yoon, J.H.; Son, N.-H.; Han, K.; Moon, H.J. Screening in Patients With Dense Breasts: Comparison of Mammography, Artificial Intelligence, and Supplementary Ultrasound. American Journal of Roentgenology 2024, 222. [CrossRef]

- Chang, A.Y.; Joe, B.N. Breast MRI Finds More Invasive Cancers than Digital Breast Tomosynthesis in Women with Dense Breasts Undergoing Screening. Radiol Imaging Cancer 2020, 2, e204023. [CrossRef]

- Bancroft, A.; Santa Cruz, J.; Levett, K.; Nguyen, Q.D. Incidental Breast Hemangioma on Breast MRI: A Case Report. Cureus 2024. [CrossRef]

- Magny, S.J.; S.R.; K.A.L. Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System. National Library of Medicine 2023.

- Esposito, D.; Paternò, G.; Ricciardi, R.; Sarno, A.; Russo, P.; Mettivier, G. A Pre-Processing Tool to Increase Performance of Deep Learning-Based CAD in Digital Breast Tomosynthesis. Health Technol (Berl) 2024, 14, 81–91. [CrossRef]

- Balma, M.; Liberini, V.; Buschiazzo, A.; Racca, M.; Rizzo, A.; Nicolotti, D.G.; Laudicella, R.; Quartuccio, N.; Longo, M.; Perlo, G.; et al. The Role of Theragnostics in Breast Cancer: A Systematic Review of the Last 12 Years. Current Medical Imaging Formerly Current Medical Imaging Reviews 2023, 19, 817–831. [CrossRef]

- Laudicella, R.; Comelli, A.; Spataro, A.; Stefano, A.; Vento, A.; Liberini, V.; Popescu, C.; Arico, D.; Ippolito, M.; Burger, I.A. Response Prediction to PRRT in Progressing and Metastatic GEP-NET Undergoing Restaging 68Ga-DOTA PETICT: A Preliminary Multicenter Radiomics Study. In Proceedings of the JOURNAL OF NEUROENDOCRINOLOGY; WILEY 111 RIVER ST, HOBOKEN 07030-5774, NJ USA, 2021; Vol. 33, p. 189.

- Perniciano, A.; Loddo, A.; Di Ruberto, C.; Pes, B. Insights into Radiomics: Impact of Feature Selection and Classification. Multimed Tools Appl 2024, 1–27. [CrossRef]

- Marinov, S.; Buliev, I.; Cockmartin, L.; Bosmans, H.; Bliznakov, Z.; Mettivier, G.; Russo, P.; Bliznakova, K. Radiomics Software for Breast Imaging Optimization and Simulation Studies. Physica Medica 2021, 89, 114–128. [CrossRef]

- Najjar, R. Redefining Radiology: A Review of Artificial Intelligence Integration in Medical Imaging. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 2760. [CrossRef]

- Jha, A.K.; Mithun, S.; Sherkhane, U.B.; Dwivedi, P.; Puts, S.; Osong, B.; Traverso, A.; Purandare, N.; Wee, L.; Rangarajan, V.; et al. Emerging Role of Quantitative Imaging (Radiomics) and Artificial Intelligence in Precision Oncology. Explor Target Antitumor Ther 2023, 569–582. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Guo, Y.; Jin, Q. Radiomics and Its Feature Selection: A Review. Symmetry (Basel) 2023, 15, 1834. [CrossRef]

- Vial, A.; Stirling, D.; Field, M.; Ros, M.; Ritz, C.; Carolan, M.; Holloway, L.; Miller, A.A. The Role of Deep Learning and Radiomic Feature Extraction in Cancer-Specific Predictive Modelling: A Review. Transl Cancer Res 2018, 7, 803–816. [CrossRef]

- Carriero, A.; Groenhoff, L.; Vologina, E.; Basile, P.; Albera, M. Deep Learning in Breast Cancer Imaging: State of the Art and Recent Advancements in Early 2024. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 848. [CrossRef]

- Ferro, A.; Bottosso, M.; Dieci, M.V.; Scagliori, E.; Miglietta, F.; Aldegheri, V.; Bonanno, L.; Caumo, F.; Guarneri, V.; Griguolo, G.; et al. Clinical Applications of Radiomics and Deep Learning in Breast and Lung Cancer: A Narrative Literature Review on Current Evidence and Future Perspectives. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2024, 203, 104479. [CrossRef]

- Pasini, G.; Bini, F.; Russo, G.; Marinozzi, F.; Stefano, A. MatRadiomics: From Biomedical Image Visualization to Predictive Model Implementation; 2022; Vol. 13373 LNCS; ISBN 9783031133206.

- Bini, F.; Missori, E.; Pucci, G.; Pasini, G.; Marinozzi, F.; Forte, G.I.; Russo, G.; Stefano, A. Preclinical Implementation of MatRadiomics: A Case Study for Early Malformation Prediction in Zebrafish Model. J Imaging 2024, 10, 290. [CrossRef]

- Stefano, A. Challenges and Limitations in Applying Radiomics to PET Imaging: Possible Opportunities and Avenues for Research. Comput Biol Med 2024, 179, 108827. [CrossRef]

- Sawyer-Lee, R., G.F., H.A., & R.D. Curated Breast Imaging Subset of Digital Database for Screening Mammography (CBIS-DDSM). DataCite Commons 2016.

- Pasini, G.; Bini, F.; Russo, G.; Comelli, A.; Marinozzi, F.; Stefano, A. MatRadiomics: A Novel and Complete Radiomics Framework, from Image Visualization to Predictive Model. J Imaging 2022, 8. [CrossRef]

- Pyradiomics Documentation Release v3.0.Post5+gf06ac1d Pyradiomics Community. 2020.

- Horng, H.; Singh, A.; Yousefi, B.; Cohen, E.A.; Haghighi, B.; Katz, S.; Noël, P.B.; Shinohara, R.T.; Kontos, D. Generalized ComBat Harmonization Methods for Radiomic Features with Multi-Modal Distributions and Multiple Batch Effects. Sci Rep 2022, 12, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Bauckneht, M.; Pasini, G.; Di Raimondo, T.; Russo, G.; Raffa, S.; Donegani, M.I.; Dubois, D.; Peñuela, L.; Sofia, L.; Celesti, G.; et al. [18F]PSMA-1007 PET/CT-Based Radiomics May Help Enhance the Interpretation of Bone Focal Uptakes in Hormone-Sensitive Prostate Cancer Patients. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2025, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Stefano, A.; Mantarro, C.; Richiusa, S.; Pasini, G.; Sabini, G.; Cosentino, S.; Ippolito, M.-S. Prediction of High Pathological Grade in Prostate Cancer Patients Undergoing [ 18 F]-PSMA PET/CT: A Preliminary Radiomics Study;

- Pasini, G.; Russo, G.; Mantarro, C.; Bini, F.; Richiusa, S.; Morgante, L.; Comelli, A.; Russo, G.I.; Sabini, M.G.; Cosentino, S.; et al. A Critical Analysis of the Robustness of Radiomics to Variations in Segmentation Methods in 18F-PSMA-1007 PET Images of Patients Affected by Prostate Cancer. Diagnostics 2023, 13. [CrossRef]

- Pasini, G.; Stefano, A.; Russo, G.; Comelli, A.; Marinozzi, F.; Bini, F. Phenotyping the Histopathological Subtypes of Non-Small-Cell Lung Carcinoma: How Beneficial Is Radiomics? Diagnostics 2023, 13. [CrossRef]

- Vernuccio, F.; Arnone, F.; Cannella, R.; Verro, B.; Comelli, A.; Agnello, F.; Stefano, A.; Gargano, R.; Rodolico, V.; Salvaggio, G.; et al. Diagnostic Performance of Qualitative and Radiomics Approach to Parotid Gland Tumors: Which Is the Added Benefit of Texture Analysis? British Journal of Radiology 2021, 94. [CrossRef]

- Sukassini, M.P.; V.T. Noise Removal Using Morphology and Median Filter Methods in Mammogram Images. In Proceedings of the The 3rd International Conference on Small & Medium Business; 2016.

- Nguyen, H.T.P.; C.Z.; N.K.; K.S.; S.N.; P.M. Pre-Processing Image Using Brightening, CLAHE and RETINEX. Electrical Engineering and Systems Science > Image and Video Processing 2020.

- Erwin Improving Retinal Image Quality Using the Contrast Stretching, Histogram Equalization, and CLAHE Methods with Median Filters. International Journal of Image, Graphics and Signal Processing 2020, 12, 30–41. [CrossRef]

- Pisano, E.D.; Zong, S.; Hemminger, B.M.; DeLuca, M.; Johnston, R.E.; Muller, K.; Braeuning, M.P.; Pizer, S.M. Contrast Limited Adaptive Histogram Equalization Image Processing to Improve the Detection of Simulated Spiculations in Dense Mammograms. J Digit Imaging 1998, 11, 193–200. [CrossRef]

- Sanagavarapu, S.; Sridhar, S.; Gopal, T.V. COVID-19 Identification in CLAHE Enhanced CT Scans with Class Imbalance Using Ensembled ResNets. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International IOT, Electronics and Mechatronics Conference (IEMTRONICS); IEEE, April 21 2021; pp. 1–7.

- Gonzalez, R.C.; W.R.E. Digital Image Processing; 2009;

- Teng, X.; Wang, Y.; Nicol, A.J.; Ching, J.C.F.; Wong, E.K.Y.; Lam, K.T.C.; Zhang, J.; Lee, S.W.-Y.; Cai, J. Enhancing the Clinical Utility of Radiomics: Addressing the Challenges of Repeatability and Reproducibility in CT and MRI. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 1835. [CrossRef]

- Mayerhoefer, M.E.; Materka, A.; Langs, G.; Häggström, I.; Szczypiński, P.; Gibbs, P.; Cook, G. Introduction to Radiomics. Journal of Nuclear Medicine 2020, 61, 488–495. [CrossRef]

- van Griethuysen, J.J.M.; Fedorov, A.; Parmar, C.; Hosny, A.; Aucoin, N.; Narayan, V.; Beets-Tan, R.G.H.; Fillion-Robin, J.-C.; Pieper, S.; Aerts, H.J.W.L. Computational Radiomics System to Decode the Radiographic Phenotype. Cancer Res 2017, 77, e104–e107. [CrossRef]

- Rajpoot, C.S.; Sharma, G.; Gupta, P.; Dadheech, P.; Yahya, U.; Aneja, N. Feature Selection-Based Machine Learning Comparative Analysis for Predicting Breast Cancer. Applied Artificial Intelligence 2024, 38. [CrossRef]

- Antunes, A.R.; Matos, M.A.; Costa, L.A.; Rocha, A.M.A.C.; Braga, A.C. Feature Selection Optimization for Breast Cancer Diagnosis. In; 2021; pp. 492–506.

- Matharaarachchi, S.; Domaratzki, M.; Muthukumarana, S. Assessing Feature Selection Method Performance with Class Imbalance Data. Machine Learning with Applications 2021, 6, 100170. [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.; Hong, S.; Oh, E.; Lee, W.J.; Jeong, W.K.; Kim, K. Development of a Flexible Feature Selection Framework in Radiomics-Based Prediction Modeling: Assessment with Four Real-World Datasets. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 29297. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Mansmann, U.; Du, S.; Hornung, R. Benchmark Study of Feature Selection Strategies for Multi-Omics Data. BMC Bioinformatics 2022, 23, 412. [CrossRef]

- Saeys, Y.; Inza, I.; Larrañaga, P. A Review of Feature Selection Techniques in Bioinformatics. Bioinformatics 2007, 23, 2507–2517. [CrossRef]

- Molina, L.C.; Belanche, L.; Nebot, A. Feature Selection Algorithms: A Survey and Experimental Evaluation. In Proceedings of the 2002 IEEE International Conference on Data Mining, 2002. Proceedings.; IEEE Comput. Soc; pp. 306–313.

- Barone, S.; Cannella, R.; Comelli, A.; Pellegrino, A.; Salvaggio, G.; Stefano, A.; Vernuccio, F. Hybrid Descriptive-inferential Method for Key Feature Selection in Prostate Cancer Radiomics. Appl Stoch Models Bus Ind 2021, 37, 961–972. [CrossRef]

- Guyon, I.; E.A. An Introduction of Variable and Feature Selection. CrossRef Listing of Deleted DOIs 2000, 1. [CrossRef]

- Comelli, A.; Stefano, A.; Bignardi, S.; Russo, G.; Sabini, M.G.; Ippolito, M.; Barone, S.; Yezzi, A. Active Contour Algorithm with Discriminant Analysis for Delineating Tumors in Positron Emission Tomography. Artif Intell Med 2019, 94, 67–78. [CrossRef]

- Adebiyi, M.O.; Arowolo, M.O.; Mshelia, M.D.; Olugbara, O.O. A Linear Discriminant Analysis and Classification Model for Breast Cancer Diagnosis. Applied Sciences 2022, 12, 11455. [CrossRef]

- Egwom, O.J.; Hassan, M.; Tanimu, J.J.; Hamada, M.; Ogar, O.M. An LDA–SVM Machine Learning Model for Breast Cancer Classification. BioMedInformatics 2022, 2, 345–358. [CrossRef]

- Carrington, A.M.; Manuel, D.G.; Fieguth, P.W.; Ramsay, T.; Osmani, V.; Wernly, B.; Bennett, C.; Hawken, S.; Magwood, O.; Sheikh, Y.; et al. Deep ROC Analysis and AUC as Balanced Average Accuracy, for Improved Classifier Selection, Audit and Explanation. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell 2023, 45, 329–341. [CrossRef]

- Fawcett, T. An Introduction to ROC Analysis. Pattern Recognit Lett 2006, 27, 861–874. [CrossRef]

- Hajian-Tilaki, K. Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) Curve Analysis for Medical Diagnostic Test Evaluation. Caspian J Intern Med 2013, 4, 627–635.

- Tan, M.; L.Q.V. EfficientNet: Rethinking Model Scaling for Convolutional Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 36th International Conference on Machine Learning, PMLR; 2019; pp. 6105–6114.

- Ding, Y. The Impact of Learning Rate Decay and Periodical Learning Rate Restart on Artificial Neural Network. In Proceedings of the 2021 2nd International Conference on Artificial Intelligence in Electronics Engineering; ACM: New York, NY, USA, January 15 2021; pp. 6–14.

- Mahmoud Smaida, M.; Y.S.; S.A.Y.B. Learning Rate Optimization in CNN for Accurate Ophthalmic Classification. International Journal of Innovative Technology and Exploring Engineering (IJITEE) 2021, 10.

- Zadeh, S.G.; Schmid, M. Bias in Cross-Entropy-Based Training of Deep Survival Networks. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell 2021, 43, 3126–3137. [CrossRef]

- Elahi, R.; N.M. An Updated Overview of Radiomics-Based Artificial Intelligence (AI) Methods in Breast Cancer Screening and Diagnosis. Electrical Engineering and Systems Science > Image and Video Processing 2024.

- Sierra-Franco, C.A.; Hurtado, J.; de A. Thomaz, V.; da Cruz, L.C.; Silva, S. V.; Silva-Calpa, G.F.M.; Raposo, A. Towards Automated Semantic Segmentation in Mammography Images for Enhanced Clinical Applications. Journal of Imaging Informatics in Medicine 2024. [CrossRef]

- Fusco, R.; Piccirillo, A.; Sansone, M.; Granata, V.; Rubulotta, M.R.; Petrosino, T.; Barretta, M.L.; Vallone, P.; Di Giacomo, R.; Esposito, E.; et al. Radiomics and Artificial Intelligence Analysis with Textural Metrics Extracted by Contrast-Enhanced Mammography in the Breast Lesions Classification. Diagnostics 2021, 11, 815. [CrossRef]

- Gerbasi, A.; Clementi, G.; Corsi, F.; Albasini, S.; Malovini, A.; Quaglini, S.; Bellazzi, R. DeepMiCa: Automatic Segmentation and Classification of Breast MIcroCAlcifications from Mammograms. Comput Methods Programs Biomed 2023, 235, 107483. [CrossRef]

- Thirumalaisamy, S.; Thangavilou, K.; Rajadurai, H.; Saidani, O.; Alturki, N.; Mathivanan, S. kumar; Jayagopal, P.; Gochhait, S. Breast Cancer Classification Using Synthesized Deep Learning Model with Metaheuristic Optimization Algorithm. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 2925. [CrossRef]

- Salama, W.M.; Elbagoury, A.M.; Aly, M.H. Novel Breast Cancer Classification Framework Based on Deep Learning. IET Image Process 2020, 14, 3254–3259. [CrossRef]

| ROC AUC | Test ROC AUC | Accuracy | Test Accuracy |

| 97.42% | 97.08% | 94.14% | 95.63% |

| Classification type | AUC | Accuracy | Recall | Precision | F1-Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| masses | 61.48% | 56.73% | 56% | 59.36% | 57.4% |

| calcifications | 66.86% | 63.1% | 71.4% | 72.2% | 71.8% |

| Classification type | AUC | Accuracy | Recall | Precision | F1-Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| masses | 81.52% | 78% | 66.70% | 74.24% | 70.25% |

| calcifications | 76.24% | 71.1% | 85.78% | 81.96% | 78.24% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).