1. Introduction

Mammographic breast density refers to the visual appearance of the breast on an x-ray mammogram and relates to the relative amount of fibroglandular versus adipose tissue [

1]. Breast tissue with high relative abundance of fibroglandular tissue shows up white on mammograms, while breast tissue with high relative abundance of adipose tissue appears dark. Breast tissue that appears mostly white on a mammogram is considered extremely dense, and breast tissue that appears mostly dark is considered non-dense or mostly fatty. Mammographic breast density is a strong independent risk factor for breast cancer; compared with females with mostly fatty breasts, females who have extremely dense breasts have a 4- to 6-fold elevated risk of breast cancer when body mass index and age are matched [

2,

3]. Understanding the biological mechanisms that regulate mammographic breast density and breast cancer risk has the potential to provide new therapeutic opportunities for breast cancer prevention [

4].

Mammographic breast density is a radiological finding extracted from a 2-dimensional mammogram image. It refers to the overall whiteness of the image, however there can be significant heterogeneity in mammographic density within an individual breast. Research on the underlying biology is hampered by the difficulty in defining the breast density of small tissue samples which may not be representative of the mammographic density of the whole breast. To overcome this limitation, fibroglandular breast density has been used for research purposes as a surrogate measure for mammographic breast density [

5]. Fibroglandular breast density can be defined through analysis of the cellular composition of the breast in thin hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained FFPE tissue sections, and image-guided biopsies of high and low mammographic density have shown good correlation with this histological measure [

6]. There are some established automatic methods for classifying mammographic breast density in mammograms based on the integration of texture and gray-level information [

7]. However, to the best of our knowledge, no machine learning model has been developed yet for classifying fibroglandular breast density in H&E stained sections [

8]. Convolutional neural networks (CNNs) have become the leading tools for classification tasks in computer-aided diagnostic systems for medical applications [

9]. Particularly, CNN-based approaches have been successfully employed for extracting characteristic features from histopathology images of breast parenchymal tissue [

10]. Previously, CNN-based models have been used to classify H&E-stained breast tissue samples based on tumor type [

8]. The samples were classified into 4 categories from benign to invasive carcinoma. The network was successfully trained on all relative features, resulting in high sensitivity, demonstrating the potential of CNNs in classifying breast tissue samples [

11]. MobileNet-v2, a specific CNN architecture, has demonstrated promising outcomes in medical image classification [

12]. MobileNet-v2 is pre-trained on millions of images from the ImageNet dataset, enabling it to perform effectively even with limited data. It also requires minimal computational resources, possessing time and storage space, compared to other currently available CNN architectures [

13]. In contrast, vision transformers (ViTs) are a modern edition of neural networks that utilize a self-attention mechanism originally developed for natural language processing tasks but, later showed its potential capability for image classification [

14]. ViTs work by dividing an image into small, fixed-size patches, which are linearly embedded and fed into a number of transformer encoders to extract image features [

15]. ViT models have been implemented in breast ultrasound and mammography imaging to classify malignant, benign, and normal tissue [

16]. In histopathology, ViTs are proving to be a valuable tool for a broad range of tasks including classification, object detection, and image segmentation [

17].

In this paper, deep learning algorithms have been developed for the classification of fibroglandular breast density in H&E-stained FFPE sections of human breast tissue using a transferred and modified version of MobileNet-v2, and a ViT model. Four different architectures were designed for both ViT and MobileNet-v2. The accuracy and sensitivity of the MobileNet-v2 and ViT models on test data were 93% and 94%, respectively. These results were validated by evaluating model performance on unseen H&E-stained sections prepared in another laboratory. Both MobileNet-v2 and ViT models demonstrated robustness in classifying fibroglandular breast density. The deep learning algorithms developed in this study would be useful in the rapid and accurate classification of H&E-stained images based on fibroglandular breast density, although further research is needed to improve accuracy.

2. Materials and Methods

This study received ethics approval from the Central Adelaide Local Health Network Human Ethics Research Committee (TQEH Ethics Approval #2011120), and the University of Adelaide Human Ethics Committee (#H-2014-175).

2.1. Tissue Processing

Women aged between 18 and 75 attending The Queen Elizabeth Hospital (TQEH) for prophylactic mastectomy or reduction mammoplasty were consented to the study. The tissue was confirmed as healthy non-neoplastic by the TQEH pathology department. The validation sample set was collected following informed consent from women undergoing breast reduction surgery at the Flinders Medical Centre, Adelaide, SA. Breast tissue was dissected into small pieces using surgical scalpel blades. Breast tissue then was fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (Sigma-Aldrich; Cat# P6148), for 7 days at 4°C, washed twice in PBS (1X), and transferred to 70% ethanol until further processing. Tissue was processed using Excelsior tissue processor (Thermo Fisher Scientific) followed by dehydration, clearing and embedding protocol: incubating in 70%, 80%, 90% ethanol for an hour each, proceeded with incubating in 100% ethanol with 3 changes, 1 hour each, xylene with 3 changes, 1 hour each. Finally, tissue was filtrated in paraffin wax with 3 changes, 1 hour each.The resulting formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue blocks were stored at room temperature before sectioning.

2.2. Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) Staining

Five-micrometer sections were cut from FFPE blocks using a microtome (Leica Biosystems, Australia). These sections were then floated onto a warm (42°C) water bath and transferred to super adhesive glass slides (Trajan Series 3 Adhesive microscope slides, Ringwood, Victoria, Cat#473042491). The slides were incubated at 37°C overnight until fully dry. Sections were dewaxed through three changes of xylene (Merck Millipore, Darmstadt, Germany; Cat# 108298) and rehydrated through a gradient of 100%, 95%, 70%, and 50% ethanol, followed by distilled water. Tissue sections were stained with hematoxylin (Sigma Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA; Cat#HHS16) for 30 seconds and eosin (Sigma Aldrich, St Louis USA; Cat#318906) for 5 seconds. Slides were then dehydrated with 100% and 95%, ethanol and cleared with two changes of xylene. The tissue slides were then mounted using mounting medium (Proscitech, Australia; Cat#IM022). Finally, the stained slides were scanned using a digital Nanozoomer 2.0-HT slide scanner with a 40X objective lens, generating high-resolution (0.23 µm) images for computer-based analysis.

2.3. Fibroglandular Breast Density Score Classification

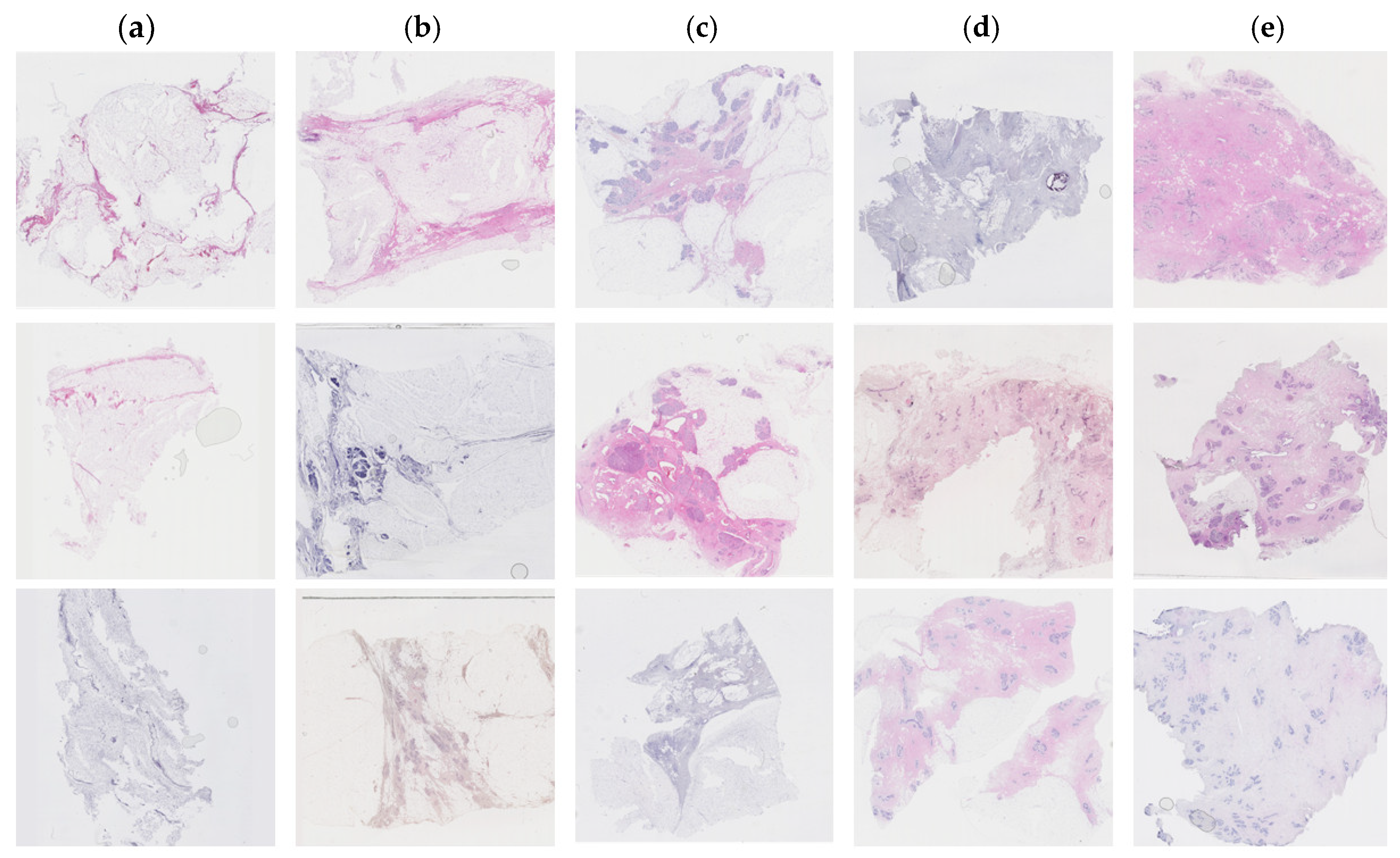

Tissue staining was performed by multiple laboratory specialists over several years, which may result in variations in staining intensity across the images (

Figure 1). The staining protocol and reagents used remained consistent throughout this study. These images were used to set up the training and test database.

A validation study was performed using H&E-stained human breast tissue independently collected from a different laboratory that was not part of the training and test dataset. These de-identified H&E-stained breast tissue sections are described in the validation section of the Results.

Each patient had an average of 10 tissue blocks. One tissue section was assessed in each FFPE tissue block. In total 965 images were collected from 93 patients. A panel of scientists (HH, LH, WI) classified each image semi-quantitatively. The panel reached a consensus on density through discussion. Higher density scores were assigned to sections containing a greater percentage of stroma and epithelium and a smaller amount of adipose tissue. The fibroglandular density classification scale was defined by Archer [

5] and has demonstrated a correlation with mammographic breast density in tissue samples obtained by x-ray image-guided biopsy [

6]. The classification scale assigned each tissue sample to a number between 1 to 5, where 1 represented 0-10%, 2 represented 10-25%, 3 represented 25-50%, 4 represented 50-75%, and 5 represented >75% of fibroglandular tissue (

Figure 1).

2.4. Image Pre-Processing

A total of 965 high-resolution original images were generated from the human breast tissues. All H&E-stained images were resized to 224x224 pixels. Then, for processing and manipulation, the images were converted into an array format and stored in a data frame. Libraries including scikit-learn 0.23.2, Pandas 1.5.3, and Numpy 1.23.5 were used for pre-processing the images. Diverse data augmentation techniques were applied to improve model generalisation and expand the training dataset [

18]. These techniques included horizontal flipping, vertical flipping, and rotating each image by 0, 90, 180, and 270 degrees. As this work focuses on the breast density classification of tissue sections and not on the density classification of the whole breast, the choice of rotation angles for data augmentation is not restricted and can be extended beyond small magnitudes. However, for mammography density classification of mammograms, it is recommended to limit the rotation angle to 0-15 degrees as higher rotations might alter the biological relevance and spatial relationships between the fundamental tissue structures. It should be noted that cropping an H&E-stained image changes its breast density score, and thus if cropping is used as an augmentation method, it requires a fibroglandular breast density re-assessment.

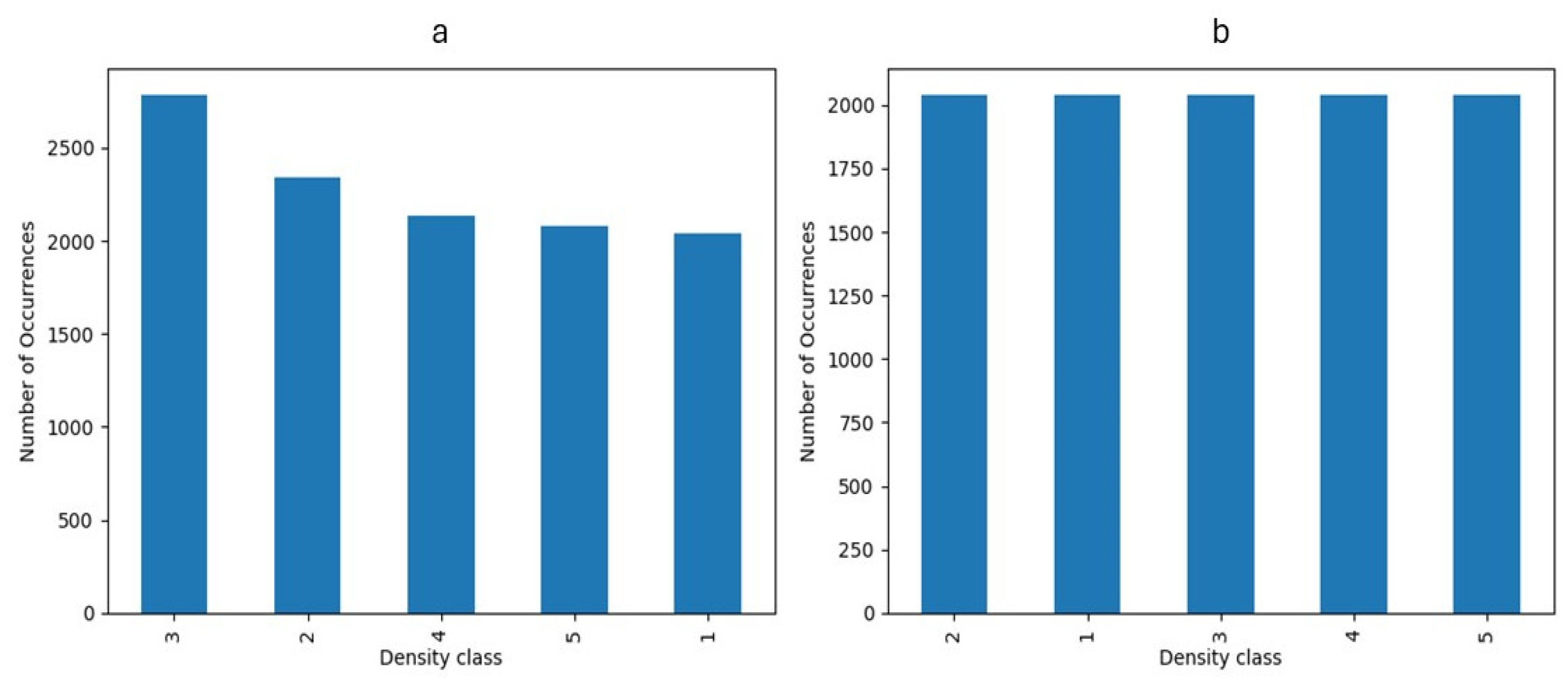

Medical images from many individuals comes with intrinsic imbalance, where some classes of fibroglandular density will be represented in the sample set more than others. To ensure each class represents itself properly, images in each class were evened out by implementing an undersampling strategy to reach an equal data distribution (

Figure 2) [

19]. Before implementation of the balancing technique, the number of samples in class 3 was maximum while density classes 1 and 5 were the minority classes. However, the number of samples in each class was around 2000 after undersampling balancing, preventing potential bias towards a specific class.

2.5. Deep Learning Model

2.5.1. MobileNet-v2

This study implemented a convolutional neural network (CNN), backend Tensorflow (version 2.12.0), using the sequential Keras library, with MobileNet-v2 architecture. MobileNet-v2 is a pre-trained CNN with 53 different layers in depth [

13] and has been trained on over a million images from the ImageNet database [

20]. The model was developed and trained using TensorFlow 2.15.0. Using MobileNet-v2 enables us to improve accuracy and perform high computational performance while minimizing the number of operations and memory required compared to other pre-trained CCN models. Reducing the complexity and fast training of MobileNet-v2 are the mode

l’s key architectural features, making it a well-suited choice for mobile and embedded applications [

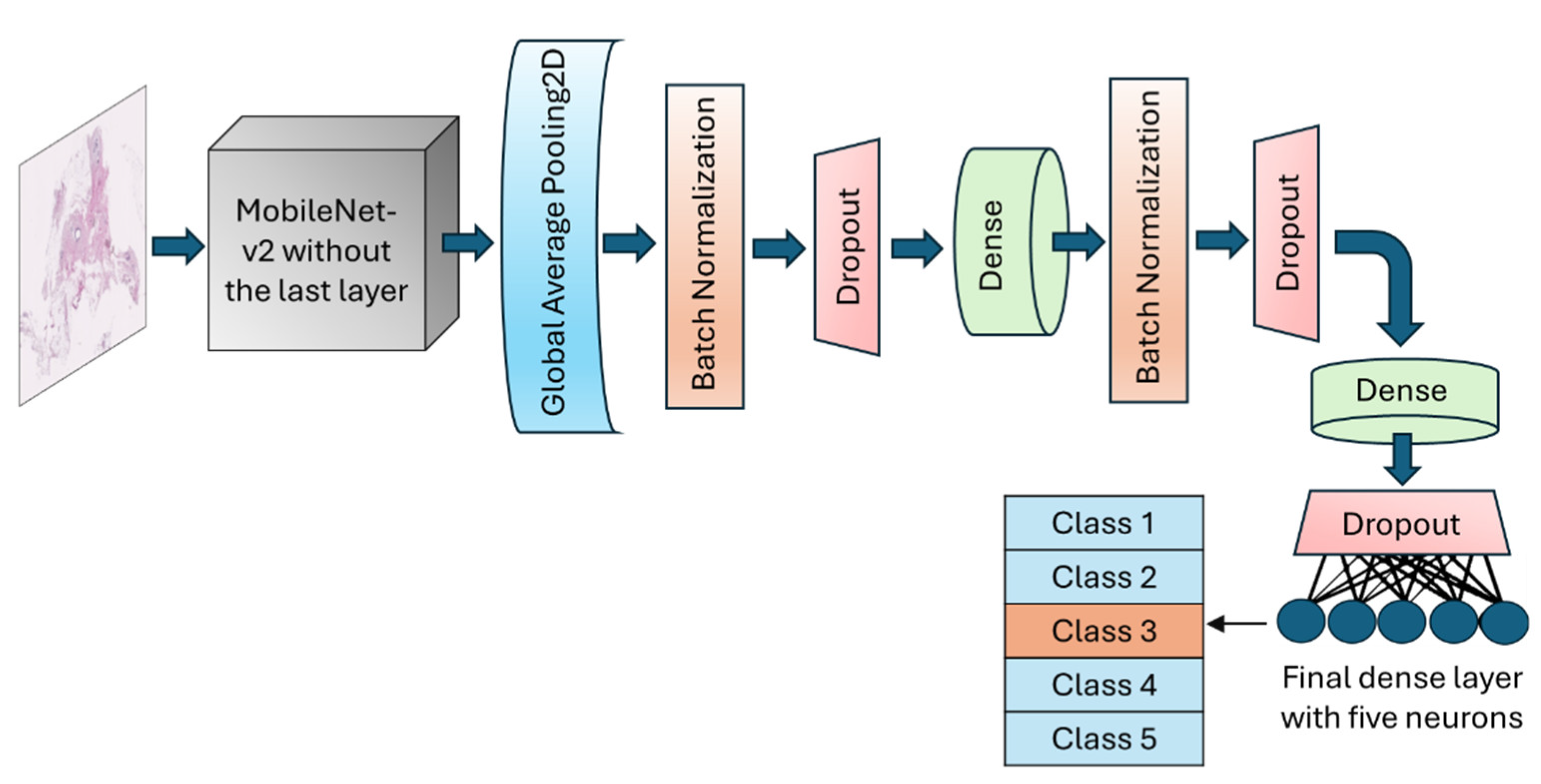

13]. In this application, the final fully connected layer of the MobileNet-v2 was excluded, allowing for adjustments based on the specific needs of our target application (breast density classification). Meanwhile, the initial layers of the model were fixed during training by freezing their parameters. The GlobalAveragePooling2D layer was called to reduce the dimensionality and number of parameters by computing the average from each feature map to a single value. BatchNormalization layer and dropout layers with a rate of 30%, were added after global average pooling layer to normalise batches and prevent potential overfitting, respectively. An intermediate dense layer with 64 neurons and ReLU activation was added to account for nonlinearity and handle complex patterns. The final dense layer had 5 neurons with softmax activation to conduct the muti-class classification and calculate the probability of each fibroglandular breast density class (

Figure 3). The learning rate was designed to change based on an exponential decay, beginning with an initial value of 0.001 and followed by a decay rate of 0.9. To optimise model weights, the model uses Adam optimizer with loss function setting to categorical cross-entropy. An early stopping callback was used to terminate the training process when validation losses do not decrease for 10 epochs in a row. However, the training can continue for a maximum of 200 consecutive epochs if necessary.

2.5.2. Vision Transformer

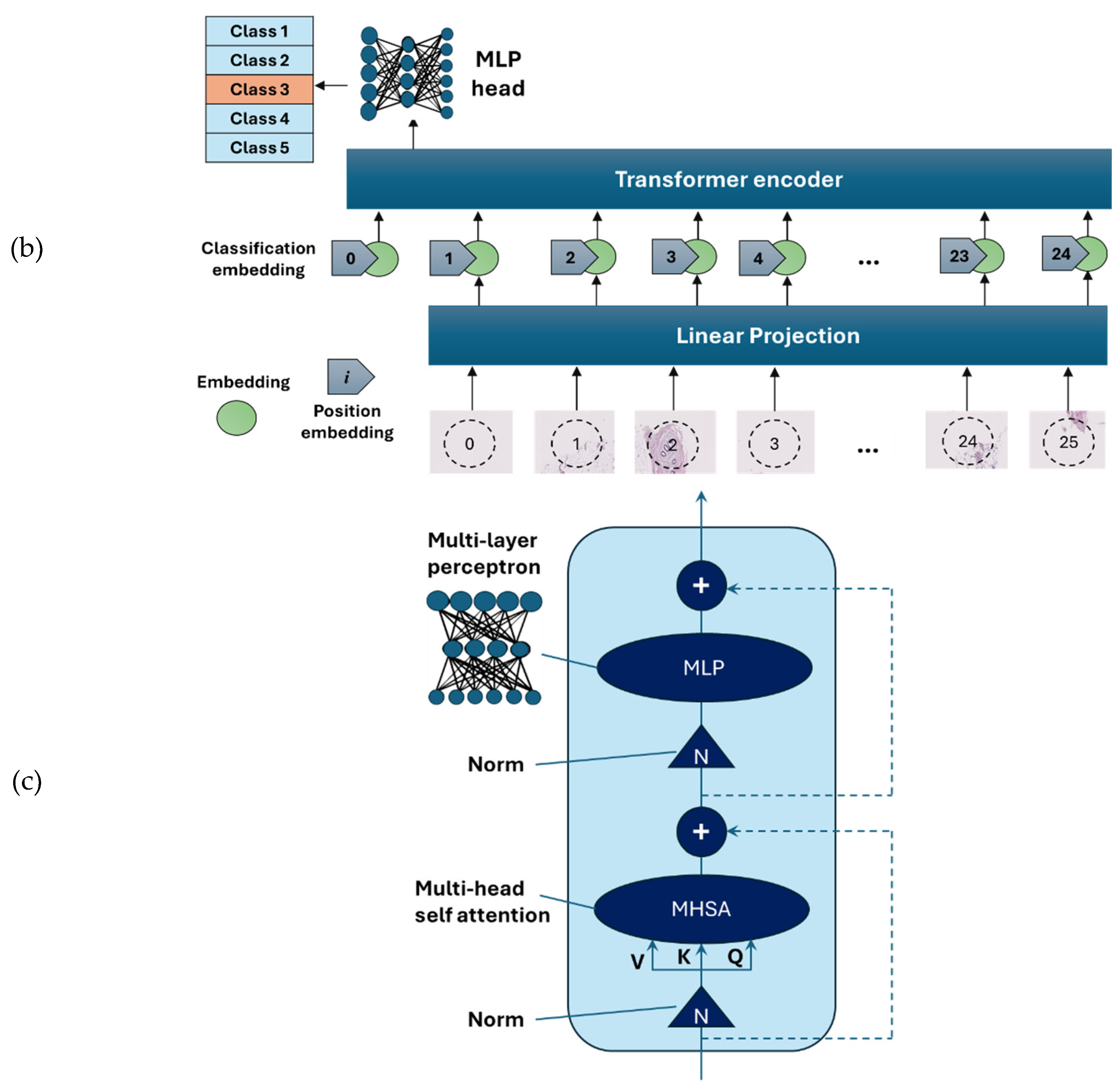

Vision Transformer (ViT) is an emerging type of deep neural network model based on transformer encoders with a self-attention mechanism [

15]. ViT showed stronger capabilities compared to the previous model using sequences of image patches to classify the full image [

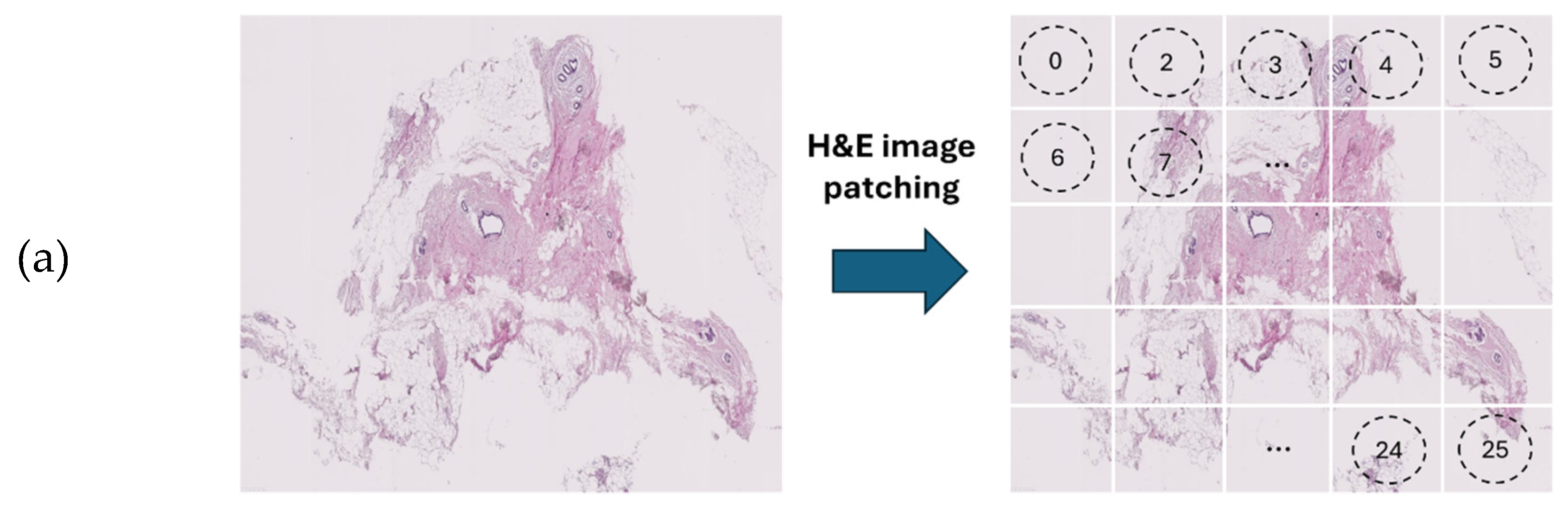

14]. As an alternative to the MobileNet-v2 model, a ViT model was developed using PyTorch version 2.3.1 and CUDA version cu118 to allow for the use of graphics processing unit (GPU) to accelerate the training process. As ViT models demand large training data, we applied larger image augmentation in our database including small adjustments to brightness, contrast, and saturation on images plus random erasing. Random erasing removed a small portion of an image with a possibility of 50%, ranging between 1% to 7% of the image, and an aspect ratio of 0.3 to 3.3, to resemble human technical errors In this study, we set the patch size to 16, model depth to 12, and attention head to 8. Patch and position embedding were implemented with an internal feature dimension of 64. The multi-layer perceptron (MLP) part had a hidden layer size of 64 pixels, and a dropout rate of 0.1 was applied to both the overall and embedding dropouts. An overview of the ViT model used for the classification of H&E-stained images of human breast tissue is shown in

Figure 4. For the loss function, we applied the cross-entropy and to optimize the model, an Adam optimizer with the learning rate 0.001 was applied. Moreover, we applied a learning rate scheduler, using the PyTorch StepLR scheduler, decaying the learning rate by a factor of gamma equal to 0.7. In this model, patience was considered 15, which stops the training process when validation losses do not decrease after 15 epochs.

3. Results

3.1. MobileNet-v2 Evaluation

The MobileNet-v2 model was transferred without the top layer. The input shape was set to (224, 224, 3). The weights of the transferred model were taken as those of the pre-trained model [

20]. One two-dimensional global average pooling layer, batch normalisation layer and a dropout layer (rate=0.3) were added, followed by a fully-connected layer (ReLU activation, neurons=128,). Batch normalisation and dropout layer of 0.4 were used after the dense layer to avoid overfitting. Another dense layer with 64 units and ReLU activation, followed by a dropout layer of 0.3 rate were implemented. The output layer was a fully-connected layer with 5 neurons (the number of breast density classes). As multi-class classification was conducted, the softmax activation was used in the last layer. The base layers of the transferred MobileNet-v2 model were frozen, keeping its parameters untrainable.

Table 1 shows the summary of hyperparameters applied for the MobileNetV2. Batch size was set to 32. The learning rate adjusted 0.001, with a step size of 1 reduced by a decay rate of 0.9. The patience was designed to 10. Training would have continued to a maximum of 200 epochs, however it could stop after 10 epochs if the validation loss was not improved. The categorical cross-entropy loss function, exponential scheduler

and Adam optimizer were used in the training process.

We evaluated the architectures of four different transferred MobileNet-v2 models (MobileNet-Arc 1, 2, 3 and 4;

Table 2). The top layer of the MobileNet-v2 was removed, and a number of various layers were added, allowing for the transferred model to learn from the training H&E dataset. One GlobalAveragePooling2D layer was added for all architecture models of MobileNet-V2. MobileNet-Arc 2 and 3 were almost similar in the number of used layers, but MobileNet-Arc 3 was the only architectural model using Cov2D and MaxPooling2D layers. MobileNet-Arc 4 had a higher number of added dense layers and dropout layers compared to others. MobileNet-Arc 3 with more than 3,000,000 total parameters was the most complex model with many internal configurations. Other architectural models held around 2,300,000 to 2,400,000 total parameters. MobileNet-Arc 1 with three added dense and dropout layers in addition to 2 BatchNorm layers contains more total layers compared to MobileNet-Arc 2 and 3 and less than MobileNet-Arc 4, using medium number of trainable parameters. MobileNet-Arc 2 had the smallest number of trainable parameters which came from having fewer layers (

Table 2).

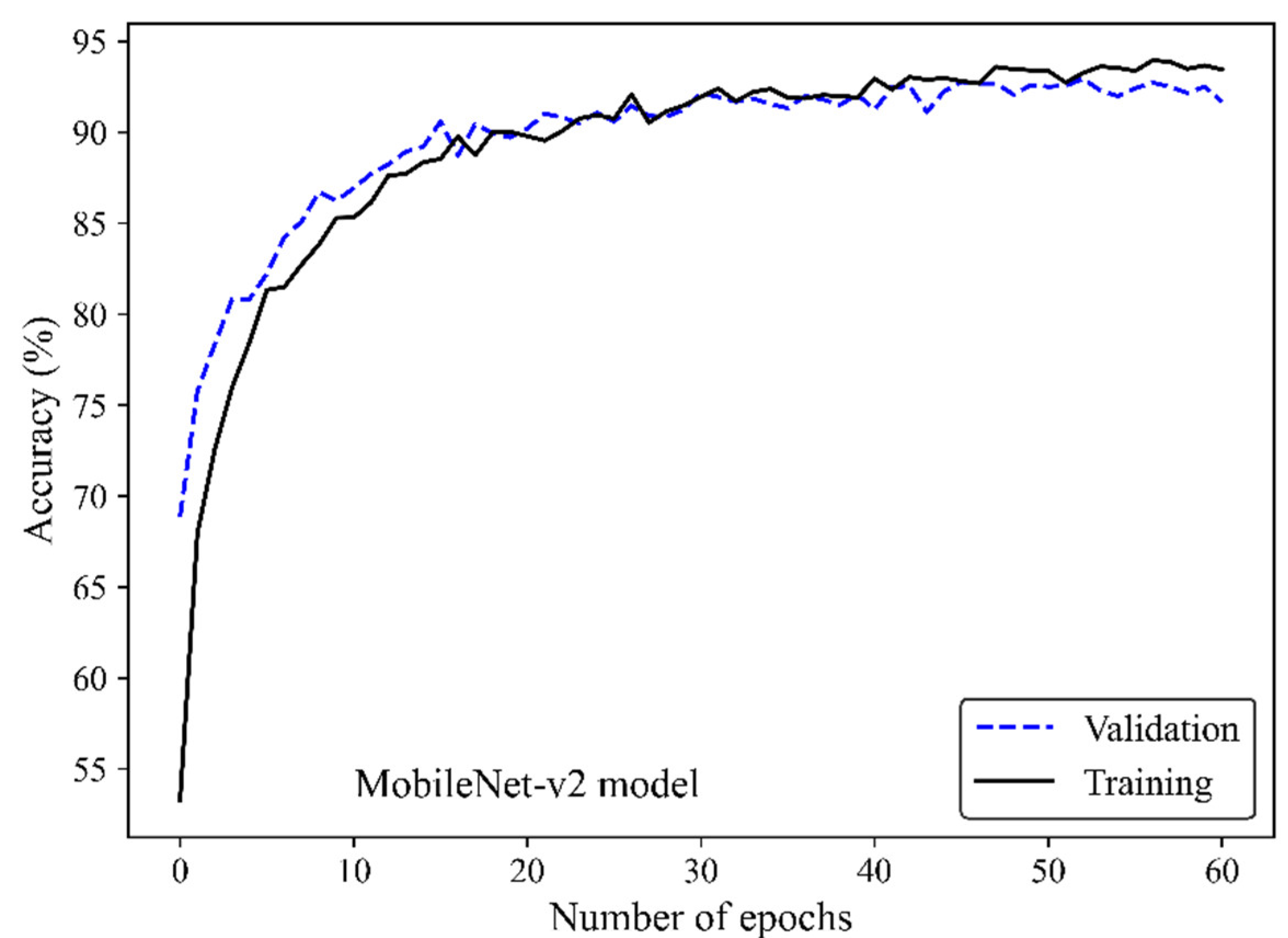

Different metrics were used to monitor and measure the performance of a model during training and testing. These parameters helped us to describe how well the model generalizes. The most important metrics for the performance analysis of classification tasks were accuracy and loss. Accuracy is defined as the ratio of all correct predictions to all predictions. Loss indicates the quantification of errors between the model’s results and true positive (TP). The training dynamics was monitored by tracking the accuracy and loss metrics throughout the training process.

Figure 5 shows the accuracy curve of the MobileNet-v2 model. In early epochs, the validation accuracy was greater than the training accuracy. As the number of epochs increased, the training and validation accuracies improved. The difference between the validation and training accuracy decreased by training the model on a higher number of epochs. The small gap between the validation and training accuracies indicated that the model effectively prevented overfitting.

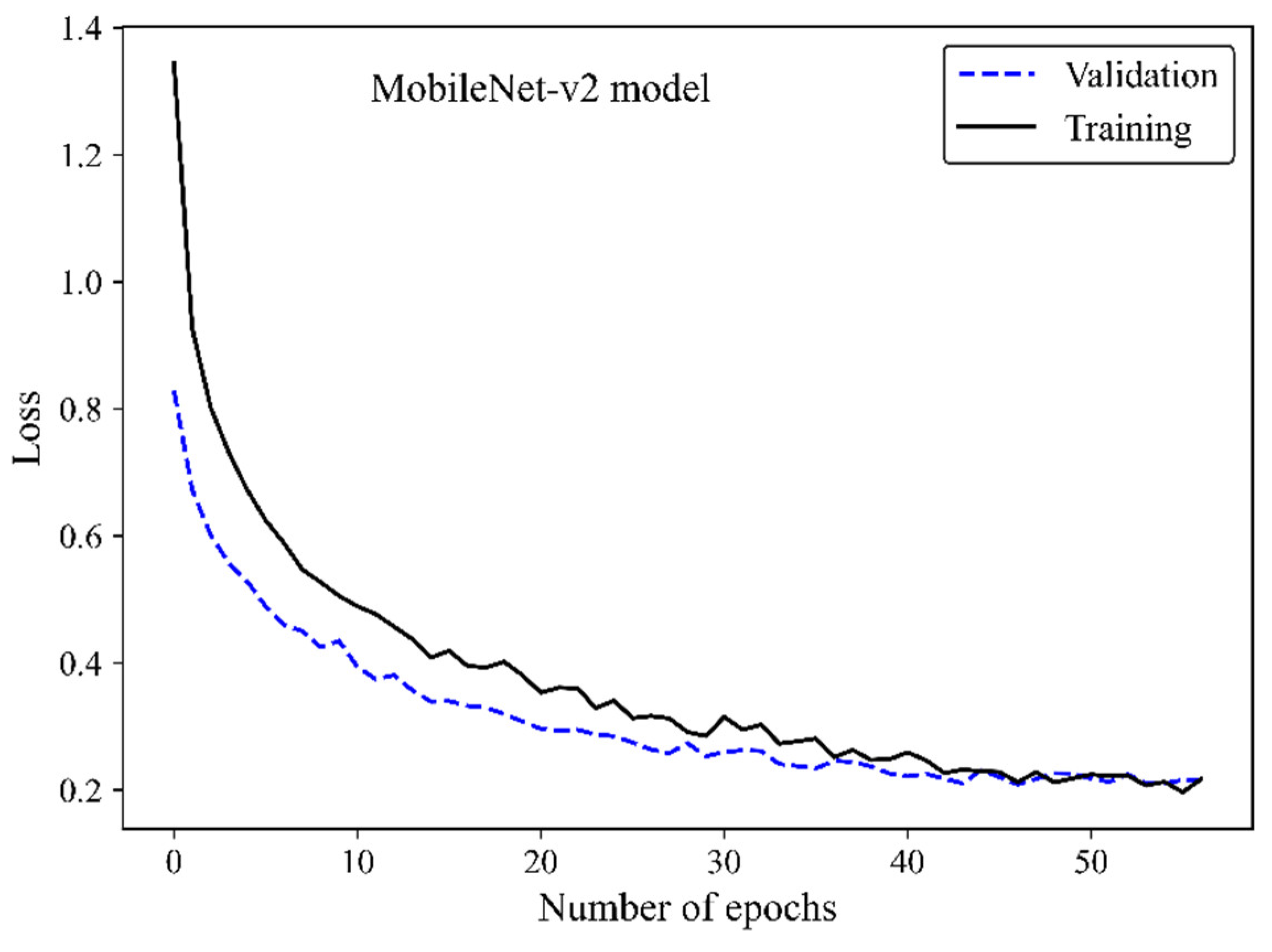

The loss curve (

Figure 6) demonstrates the MobileNet-v2 model’s learning process by increasing the number of epochs. The x-axis represents the number of epochs, whereas the y-axis is the loss. The model is gradually learning from the training H&E-stained image dataset as evidenced by the reduction of the training loss with increasing epochs. The validation loss is an indicator of the model’s performance on unseen H&E-stained breast images. It is found that both the training and validation loss decreased by training the modified transferred model using a greater number of epochs. No sign of overfitting was observed. Validation loss decreased along with training loss, indicating the generalization capability of the model. The simultaneous reduction of the validation and training loss shows that the model performs well not only on the training images but also on new unseen H&E-stained images. This implies that the machine learning model does not just memorize the training data but has learned the essential patterns and features required for reliable generalization and accurate breast density classification of new images.

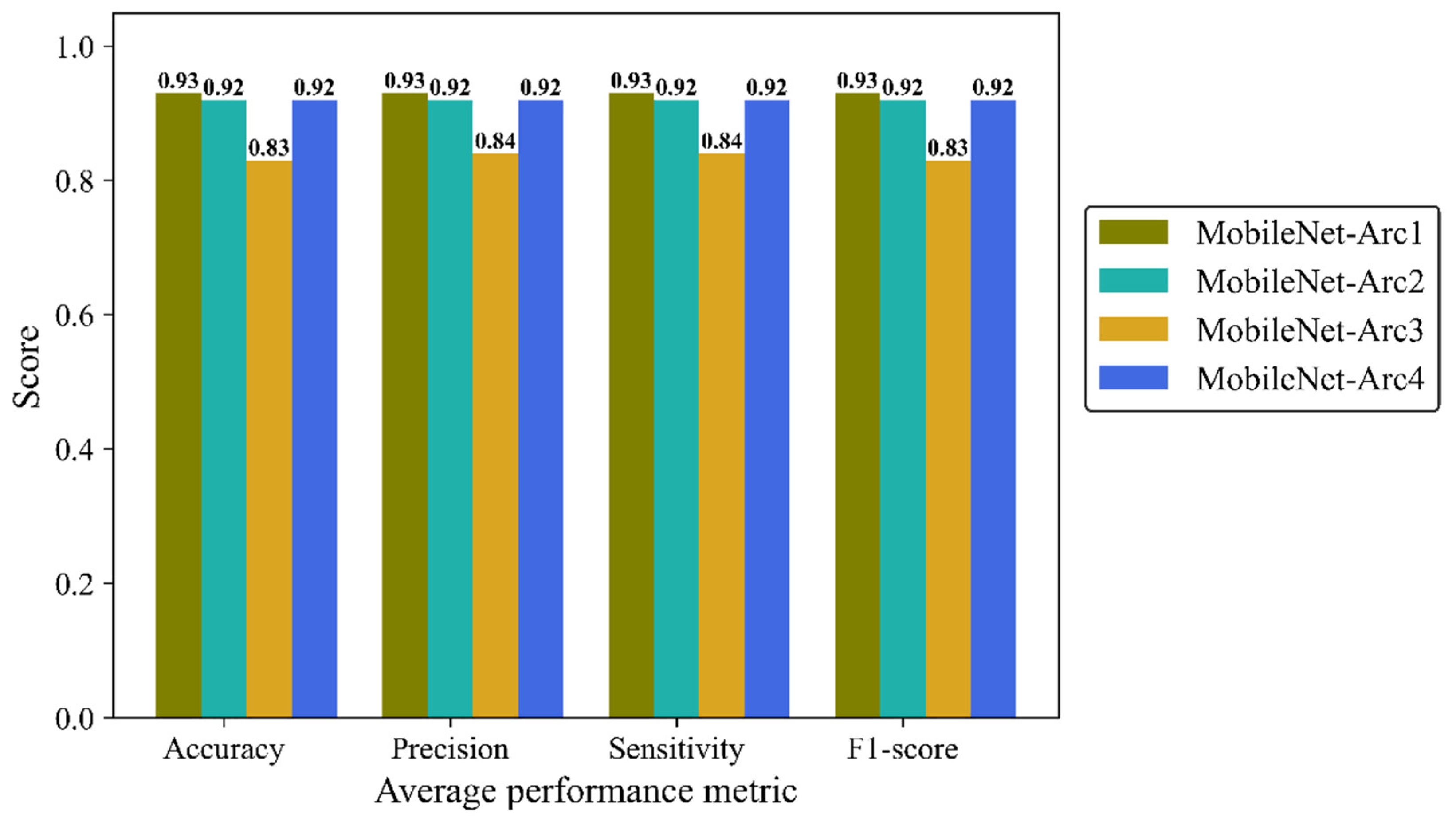

Precision, Sensitivity (recall) and F1-score were reported to give more details of the model performance. Precision is defined as a ratio of true positives to the total positive predictions including true (TP) and false positives (FP). Sensitivity (recall) is defined as the number of TP predictions divided by the total number of TP and false negative (FN) classifications. F1-score is the combination of precision and recall provide us with an overall overview of the model performance. We analyzed average metrics to make a comparison between different architectural configurations of the MobileNetV2 model. MobileNet-Arc 1 displayed the strongest overall classification performance, while MobileNet-Arc 3 showed the weakest. MobileNet-Arc 1 achieved an F1-score of 0.93 suggesting the model performs well on both precision and recall for positive cases. MobileNet-Arc 1 predicted the correct incidence for 93% of H&E-stained human breast images, introducing it as a reliable option for breast density classification. MobileNet-Arc 2 and 4 also represented a high-performing model with F1-score of 0.92, however, MobileNet-Arc 3 with a score of 0.83, suggests that it may not be a very strong model (

Figure 7).

We then evaluated the performance of each architectural model in classifying mammographic breast density into five classes using human breast histopathology samples (

Table 3). All architectural models performed best in classifying class 1 and 5 fibroglandular breast density. In contrast, performance was lowest for class 3 across all models. MobileNet-Arc1 emerged as the top performer, achieving a F1-score of 0.96 for class 5 samples. MobileNet-Arc2 and 4 also produced satisfactory results, whereas MobileNet-Arc3 was found to have an unreliable architecture. MobileNet-Arc3 achieved the precision and sensitivity of 0.73 for class 3 and 4 samples, respectively. In MobileNet-Arc3, the F1-score for all categories recorded less than 0.90, and class 3 had the lowest F1-score (0.78) among all classes in all architectures (

Table 3).

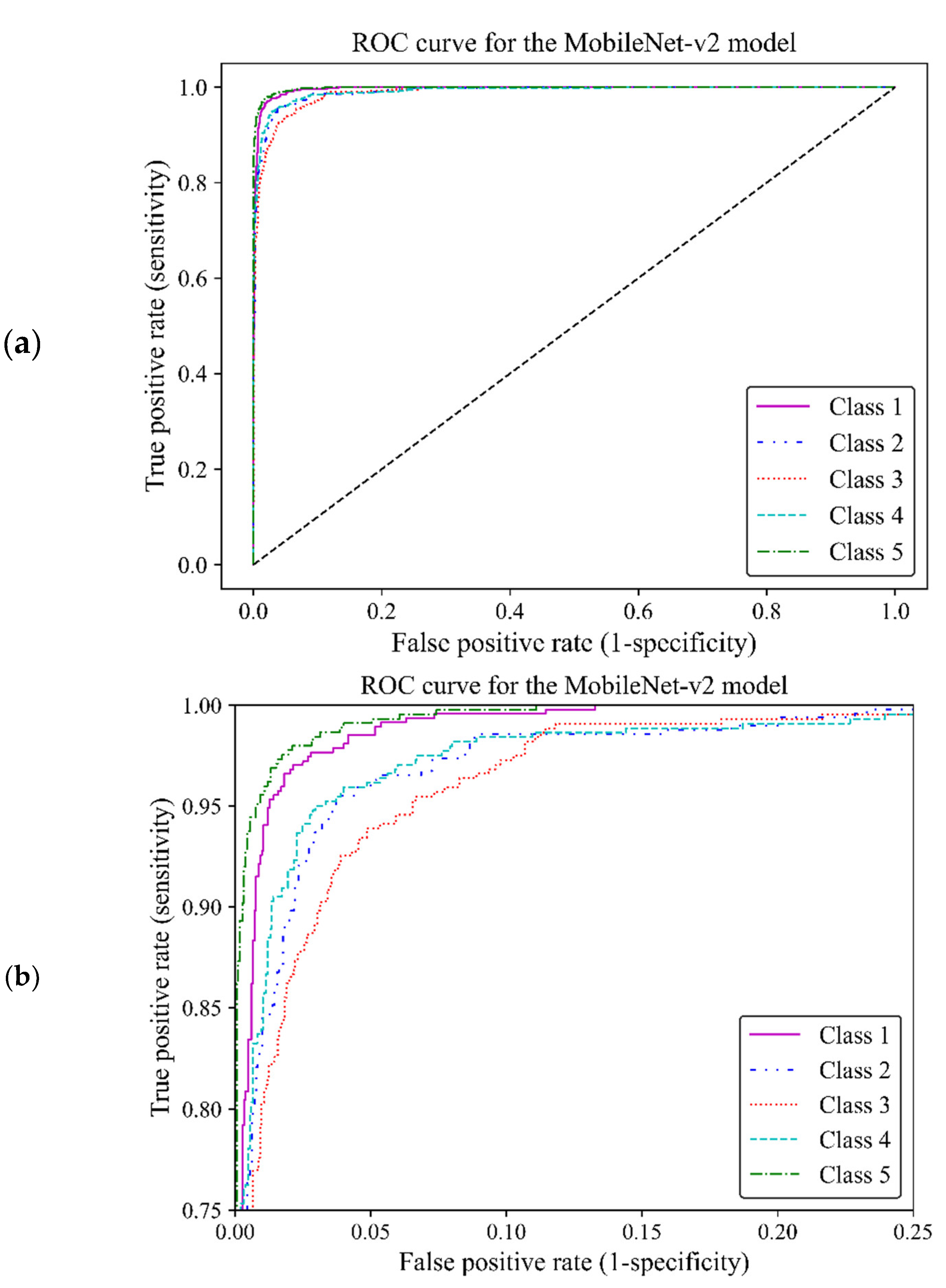

When classifying medical data, it is vital to understand the number of true positive predictions for each class as the cost of false positives. Here, the receiver operating characteristic [

21] curve [

21] and confusion matrix were used to evaluate the effectiveness of the model to distinguish between the breast density classes by showing actual true predictions and errors in each class. The ROC curve illustrates the trade-off between true positive rates (TPR) and false positive rates (FPR) for various thresholds. TPR indicates a ratio of actual positive predictions that are correctly identified by the model as positive, and FPR represents the ratio of actual negative predictions that are incorrectly identified by the model as positives. TPR and FPR range from 0 to 1. The area under the curve (AUC) of classes 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 were estimated as 0.996, 0.989, 0.990, 0.989 and 0.997, respectively, all of which were close to one. This demonstrated that the MobileNet-Arc1 model performed well in effectively distinguishing between breast density classes. The ROC curves of all classes achieved a high TPR and a low FPR as shown in

Figure 8a, indicating that the transferred MobileNet-v2 Arc 1 model was capable of classifying H&E-stained histopathology human breast sample into the five different breast density classes. The model preformed best on class 5 samples, closely followed by class 1. The model showed the weakest performance on class three but it is still considered a well-designed classifier (

Figure 8b).

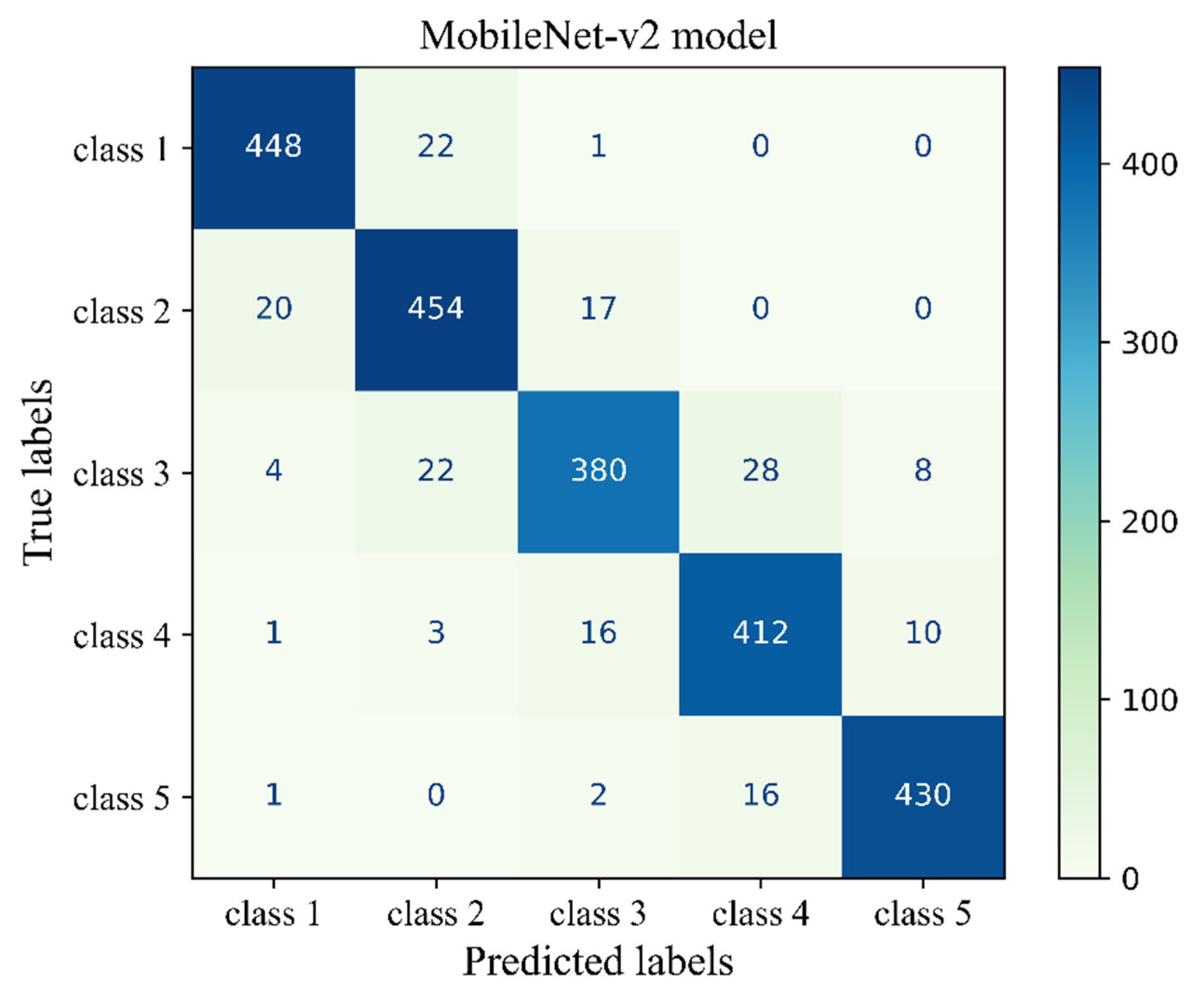

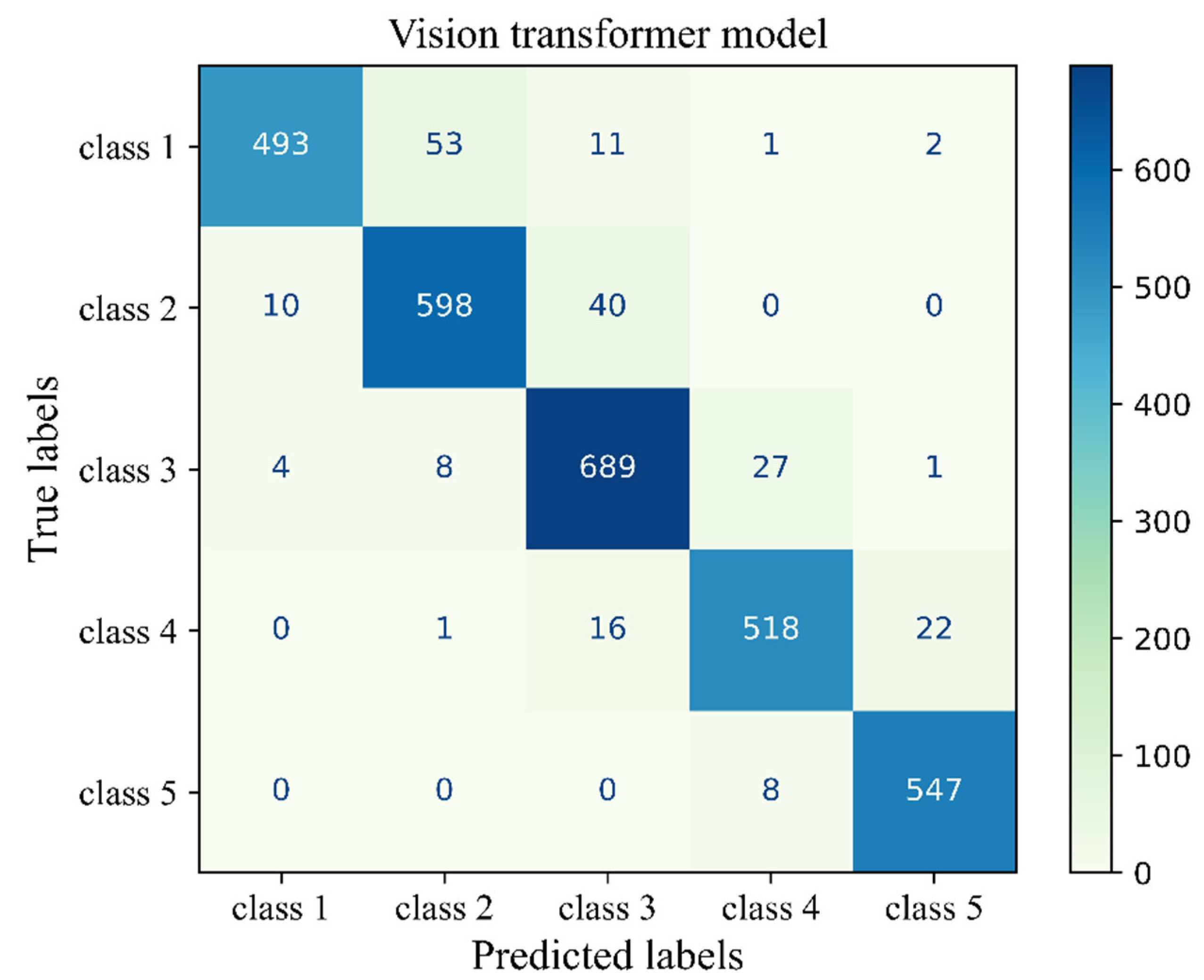

Figure 9 shows the confusion matrix of the transferred CNN model on the unseen H&E-stained images (test dataset). This heatmap provides details about the performance of the deep learning model across different mammographic density classes. The sum of each row indicates the number of true labels for a given density class, while the total number of predicted labels is the sum along the column direction. Each cell indicates the number of H&E-stained images with their true (row name) and predicted (column name) labels. Diagonal cells are the number of histopathology images that were accurately predicted by the MobileNet-v2 model for each density class while an off-diagonal cell indicates the number of H&E-stained images that were incorrectly classified by the trained model. Generally, the breast density class for the majority of H&E-stained images was correctly predicted by the model. This was well evidenced by the high values along the diagonal cells and low values across the off-diagonal cells within the confusion matrix. The most correct prediction belongs to class 1 with 448 incidences out of 471 incidences. Among the misclassified slides, 22 were incorrectly identified as class 2, and 1 was misclassified as class 3. No slides were misclassified as classes 4 or 5. The weakest performance related to class 3 where the model correctly classified 380 incidence from the total 439 incidence and misclassified 52 incidence which most of them misclassified as classes 2 and 4.

3.2. Vision Transformer (ViT) Evaluation

Here we presented a comparative analysis of the performance of Vision Transformer (ViT) models across four different structural configurations on the five density classes.

An initial learning rate of 0.001 was used that gradually reduced over time with a decay factor of 0.7 and updated weights at every step (step size=1). Training was limited to a maximum of 75 epochs, and it could be terminated if no progress is observed for 15 consecutive epochs. Cross Entropy Loss, Adam optimizer and, StepLR learning rate scheduler were employed for this ViT model (

Table 4).

Four different ViT models were designed for this study. All models except model 2 were set to a patch size of 16 and embedding dimension of 64. For the ViT model 2, both patch size and embedding dimension were set to 32. The ViT model 4 minimized the number of trainable parameters by using depth of 3, attention heads of 2, and an MLP dimension of 16 in the transformer encoder. The ViT model 1 had the largest trainable parameters and a complexity level of 64 within its ML The overall dropout and embedding dropout rates were set to 0.1 for the ViT models 1 and 2, and 0.05 and 0.02 for the ViT models 3 and 4, respectively (

Table 5).

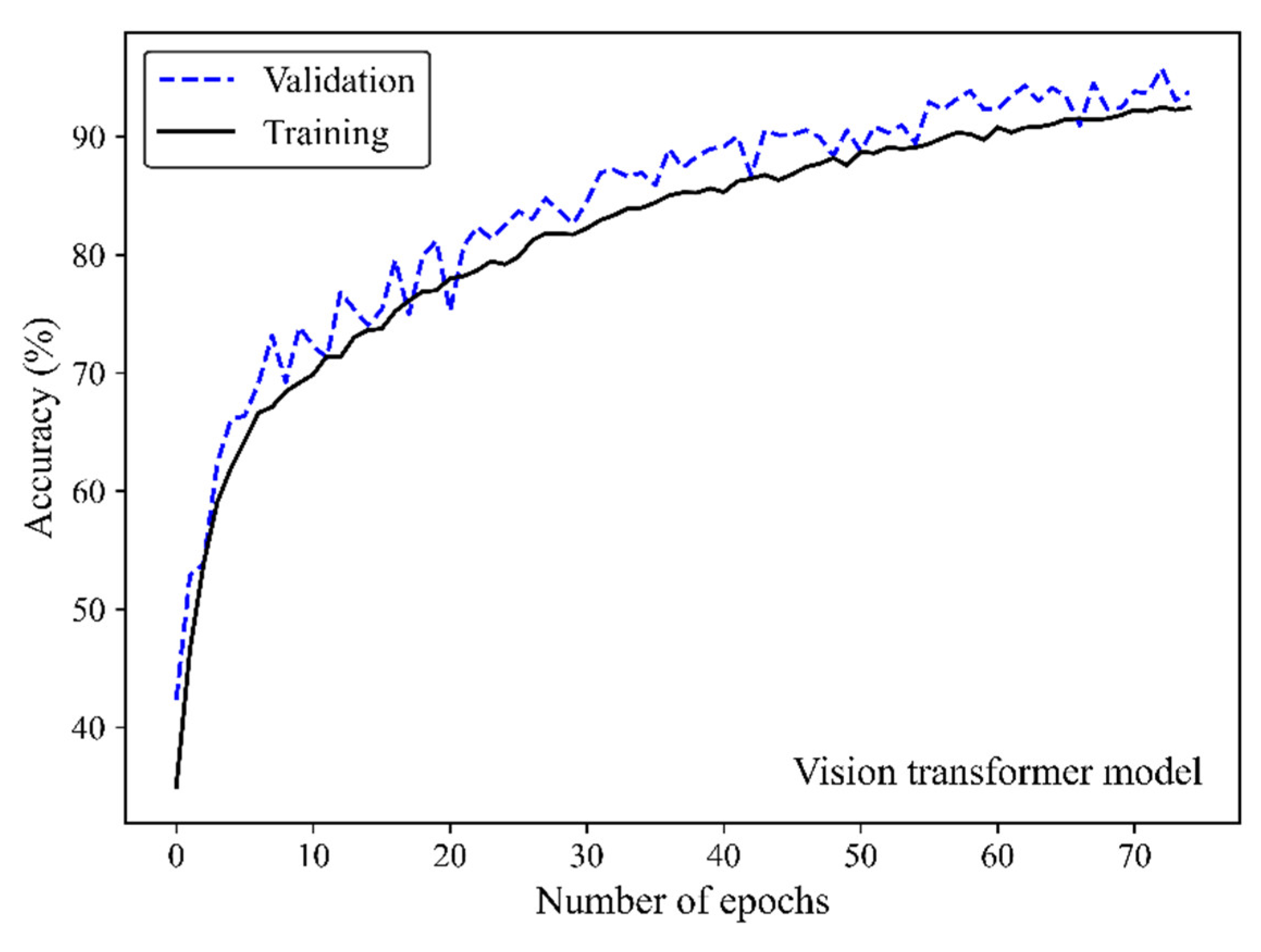

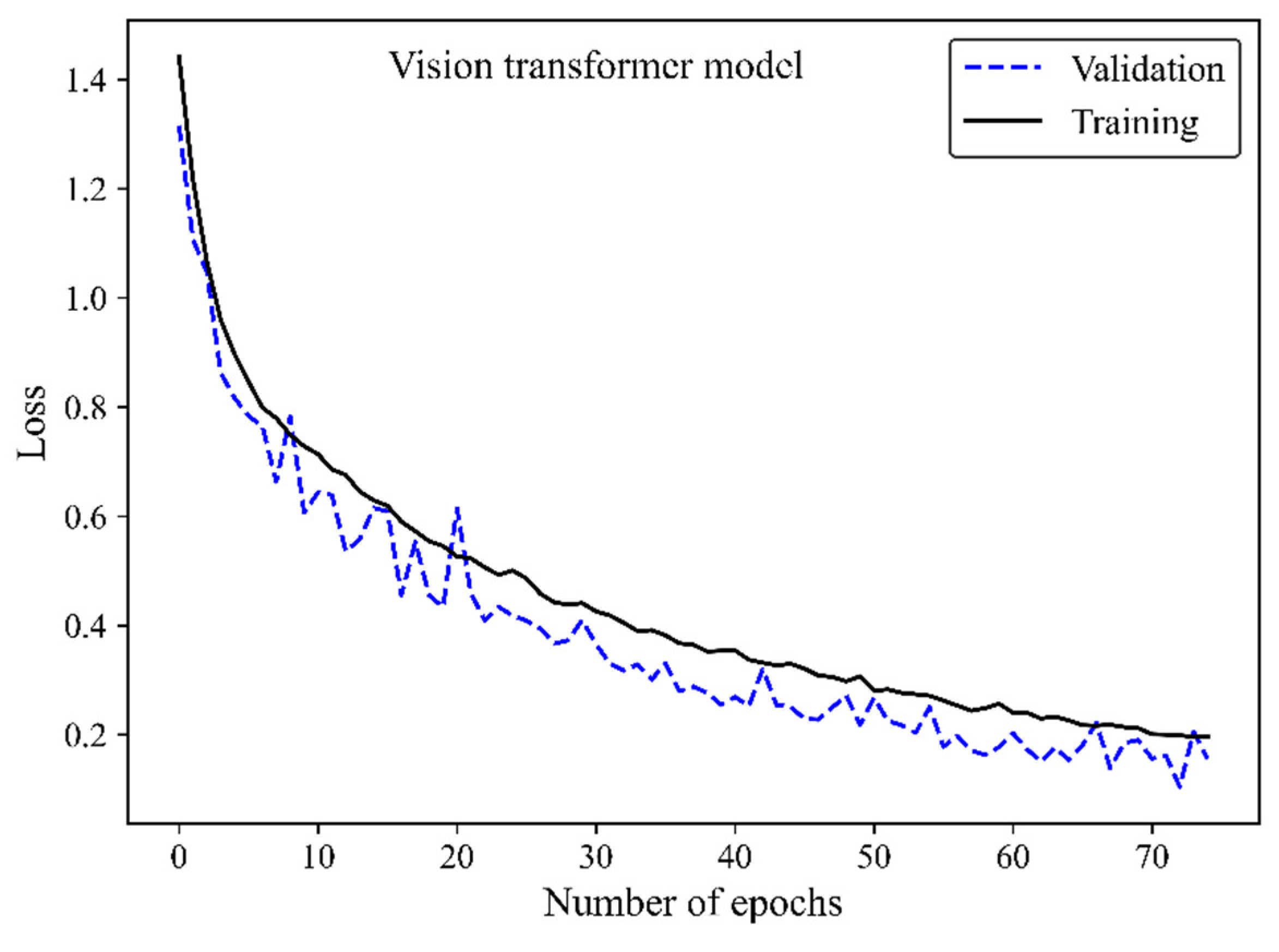

Accuracy and loss were monitored to see how the ViT model learns and adapts over time. Along with increasing the number of epochs, the number of accurate predictions improved (

Figure 10) whereas the model’s loss decreased (

Figure 11), highlighting the efficiency of the learning process.

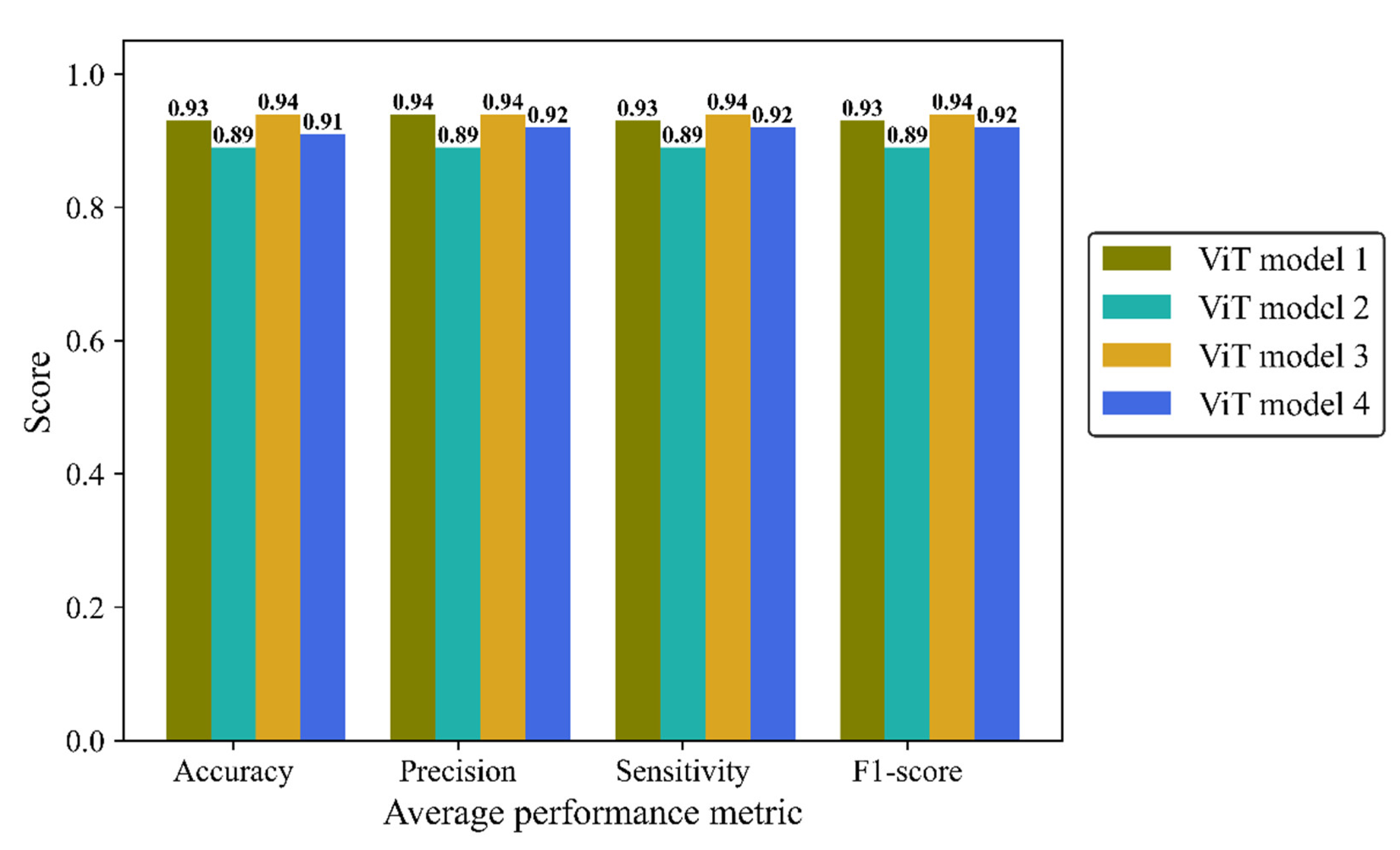

Accuracy, average precision, sensitivity (recall), and F1-score were monitored separately in the four architectures of the ViT model (

Figure 12). ViT model 3 is the most effective architecture, achieving a score of 0.94 in all mentioned metrics followed closely by the ViT model 1and ViT model 4 with average scores of 0.93 and 0.92, respectively. ViT model 2 didn’t yield the desired result, with a score of 0.89 in all metrics.

Table 6 shows the precision, sensitivity, and F1-score for each of the breast density classes, for all ViT models. All models had their best performance in class 5. Model 1 stood out with a remarkable sensitivity of 0.99 in class 5 while the ViT models 2 and 3 had the lowest sensitivity in class 5 (0.91). The F1-score ranged from 0.87 to 0.97. The lowest F1-score was related to class 2 in all models. Align with other results, model ViT 2 achieved three F1-scores below 0.90 linked to classes 2, 3, and 4, exhibiting the least satisfactory performance among different ViT architectures.

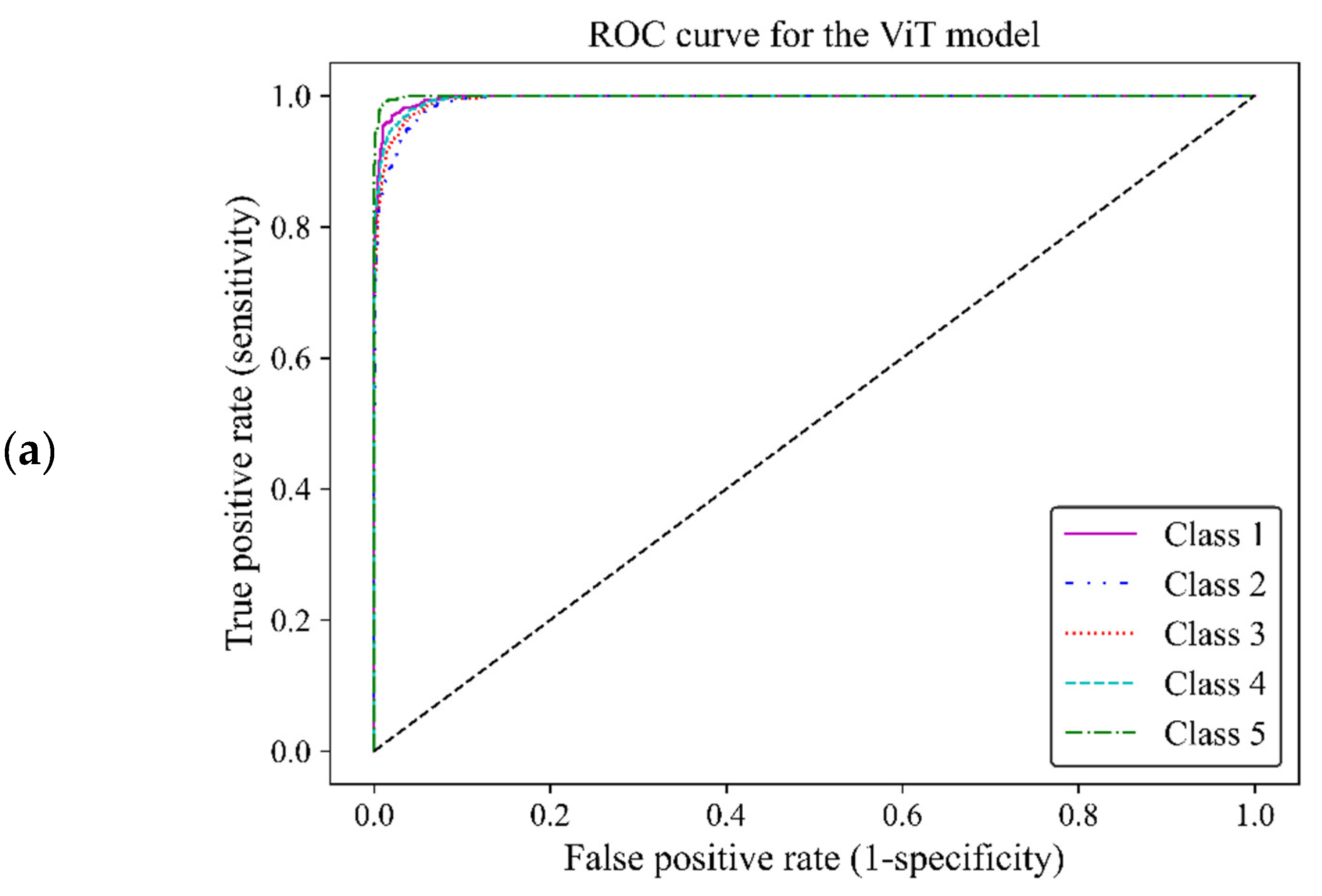

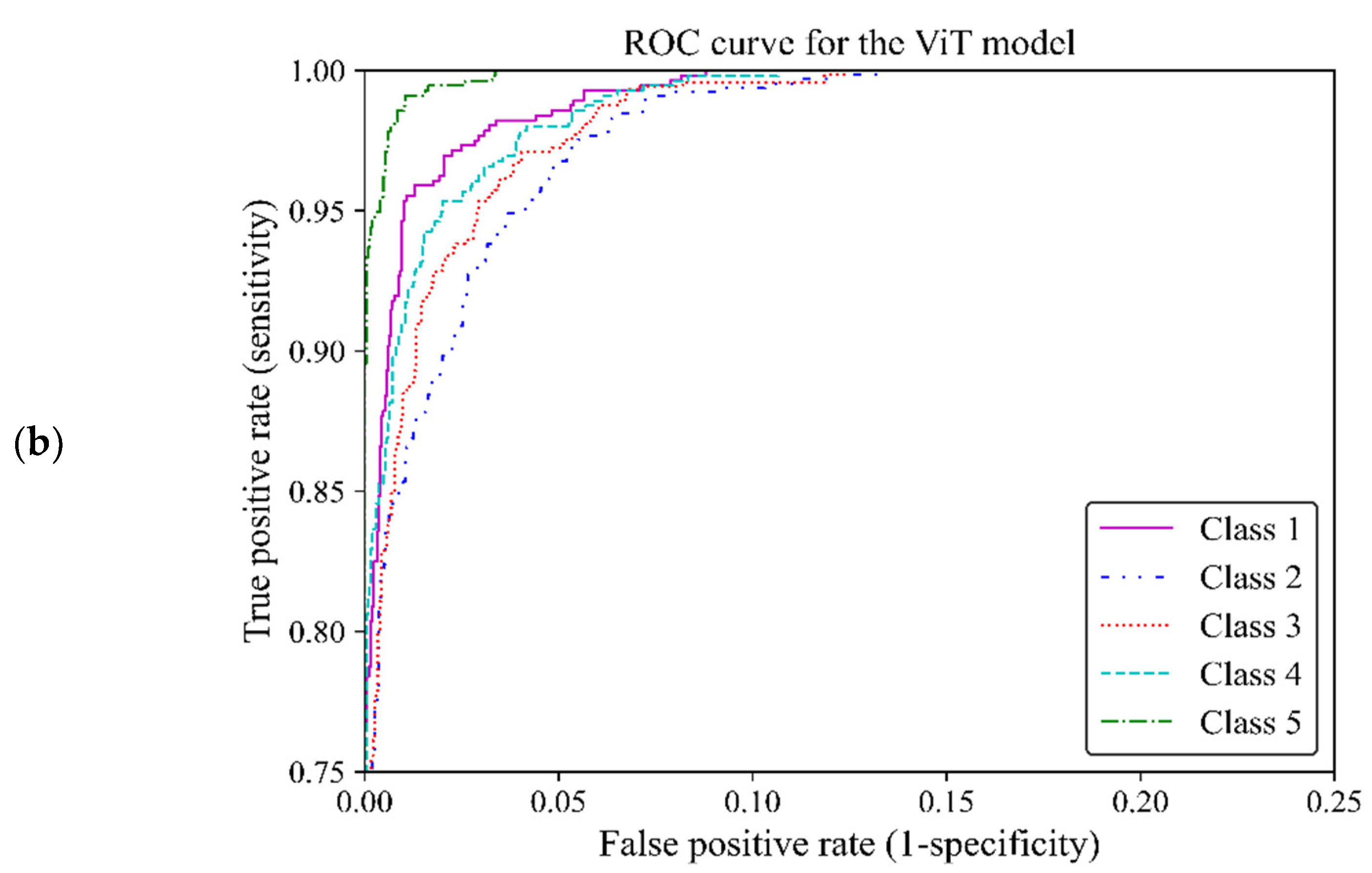

The ViT model was designed for a multi-class classification. The average metrics do not represent each class’s performance. To evaluate how well this model distinguishes the level of density between different classes, we depicted the confusion matrix and ROC curve.

Based on ROC classification all classes achieved desirable results (Figure12 a). In the zoom-in figure, we can observe model classified cases with the lowest false positive and highest true positive predictions in class 5, which makes the model performance in this class almost perfect. The curve for class 1 displayed the nearest match to the class 5 curve, followed by curves of classes 4 and 3 exhibiting high similarity. Class 2 illustrated the least separation from a random classifier compared to other classes however, it remained above chance levels for acceptable classification (Figure12 b). The area under the curve (AUC) of classes 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5 were 0.997, 0.989, 0.992, 0.993 and 0.998, respectively. All of these AUCs were close to one, indicating that the ViT model 3 was of great capability to distinguish between different breast density classes.

The number of true and false predictions in each class is presented (

Figure 13). Model performance for class 5 is the strongest among all classes, it classified 547 cases of class 5 correctly and had just 8 wrong predictions which belonged to class 4 and were misinterpreted in class 5. Class 1, 2, 3, and 4 had, 493. 593 689 and 518 true positive predictions, respectively. All classes had the most false positive predictions with their neighboring class. For instance, the model had 40 wrong predictions belonging to class 3 but taken as class 4. The model had the weakest performance in class 1 with 67 wrong predictions, which majority of which truly belonged to class 2 (

Figure 13).

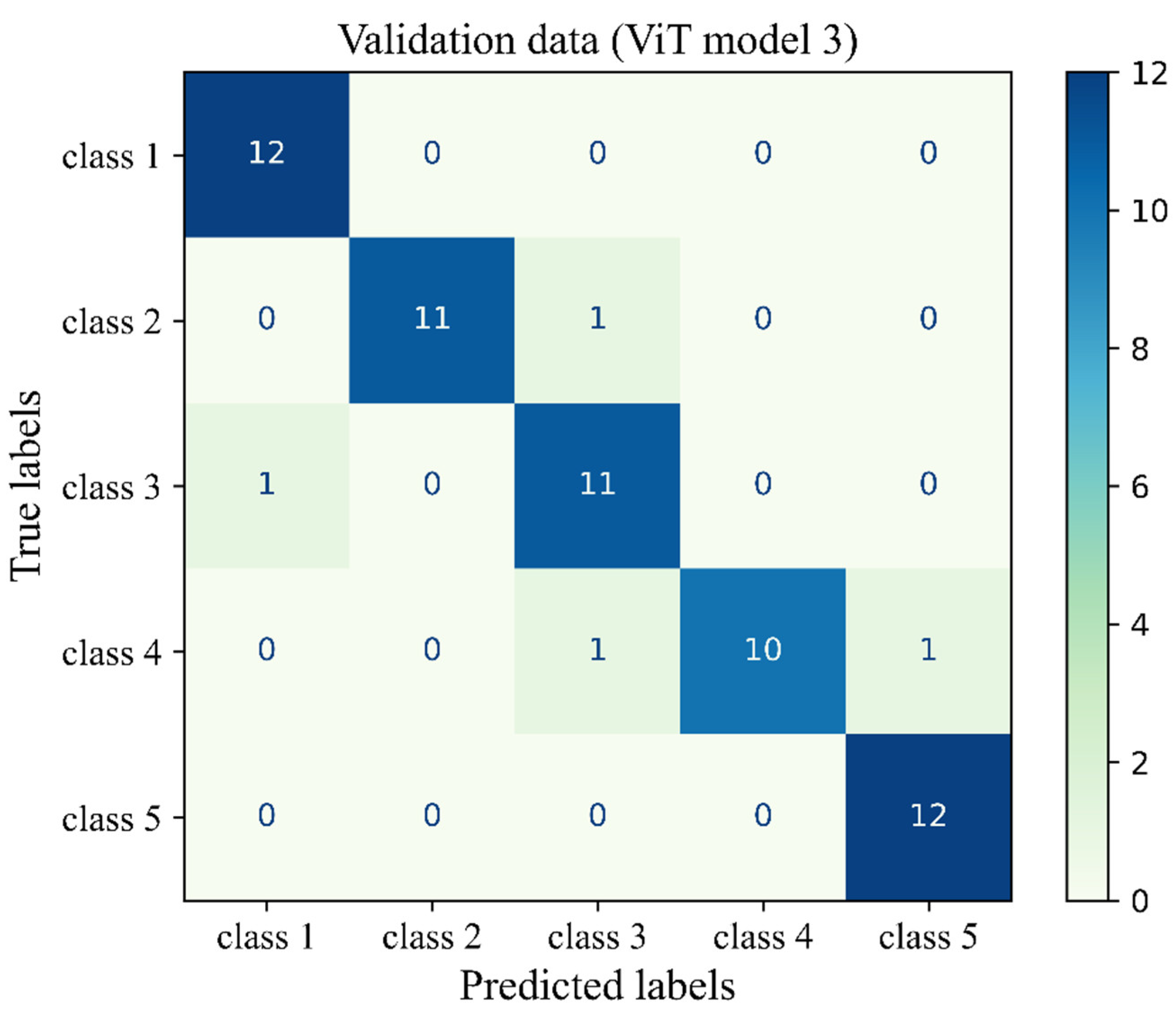

3.3. Validation Study

To verify the results of the present deep learning model, a validation study was performed using H&E-stained images from another laboratory. It is crucial to test the capability of the model and its performance on external data sources generated by different personnel and using different equipment. This minimises the risk of potential bias towards a specific imaging protocol or sectioning and staining methods. The validation set consisted of tissue sections which had been prepared and H&E stained using the same protocol, but using different reagents, processing and sectioning equipment, and conducted by different researchers. Sixty different images were used in the validation study. Fibroglandular density of the H&E-stained images were classified as described in

Section 2.3, and were uniformly distributed across all breast density classes (12 images in each class), allowing for a reasonable assessment of the model performance on each separate class.

The accuracy score, mean precision, average sensitivity and F1-score were calculated and presented in

Table 7. In addition, the precision, sensitivity and F1-score of the ViT model on each density class were measured.

Figure 14 gives more details about the classification by visualising the confusion matrix of the ViT model 3 for the unseen validation H&E-stained images of human breast tissue. To minimise the ViT model’s bias on our experimental system and to allow for domain adaptation, stain normalisation was conducted using a Reinhard normaliser. This was conducted using one target image from the H&E-stained validation sample set, which showed clear staining of blue nulcei and pink cytoplasm and extracellular matrix. The architectural configuration of the deep learning model was set the same as that of the ViT model 3, which had the best overall performance metrics on the original dataset of H&E-stained images. The accuracy of the deep learning model on unseen validation data was 93%. The mean precision, sensitivity and F1-score were 94%, 93% and 93%, respectively. These findings supported the capability of the model on the fibroglandular breast density classification of unseen H&E-stained images from another independent source and it demonstrates the flexibility of the model for domain adaptation. However, the model’s precision and F1-score on the target image distribution are, respectively, 9% and 6% lower than those of the original data distribution for class 3, highlighting the need for more domain adaptation processes to improve model performance on unseen data from different sources.

4. Discussion

Breast cancer is the most commonly diagnosed cancer in women and the incidence is rising across all age groups [

22,

23]. Current research that aims to reduce breast cancer risk and improve early detection is increasingly using data intensive approaches, which rely on computational methods for analysis. Although this brings invaluable information, the generation of large amounts of data can make it difficult to analyze information. Deep learning, using artificial neural networks that simulate the human brain, has emerged as a breakthrough approach to support medical research including single-cell transcriptomics, DNA sequencing, protein interactions, drug development, and disease diagnosis [

24,

25,

26].

Early models of deep learning used extracted features and fed them into the model. More recently, deep learning models have used pre-trained databases through a technique known as transfer learning [

27]. Models that use transfer learning benefit from a wide range of features learned from massive datasets. This makes them ideal for applications with limited data, such as medical image analysis [

28]. Medical image analysis for breast cancer research can benefit from this advancement in deep learning, which is preparing the way for using image analysis algorithms to detect and diagnose breast cancer. Of significance, deep learning approaches can reduce radiologist screening time by triaging the digital mammogram images most likely to require recall and further assessment [

29], and identify those women most at risk of a future breast cancer diagnosis [

30,

31]. Promising results from histopathological classification of breast biopsies suggest deep learning could also be employed for quality control in breast cancer detection [

32,

33].

Deep learning was successfully applied to the classification of histopathological images in various types of malignancies. Specifically using the hyperparameter optimization, color normalization, and segmentation methods in diagnosing cancer showed promising results [

34,

35]. The application of deep learning in medical image analysis is not limited to breast cancer detection. Mammographic breast density classification reached radiologist-level accuracy through this advancement. Research on this area has been transformed through use of computational methods to classify mammogram images. The most commonly used method for mammographic breast density assessment has been the Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System (BIRADS) which is 4 category of subjective classification by the radiologist [

36]. Despite using standardized protocols and advanced digital imaging methods, operator miscalculation, variation in the operator’s perception, and a heavy workload can still lead to inaccuracies in mammographic density assessment [

23]. To minimize these errors, new automated methods of mammographic density measurement have been developed that use a computerized analysis algorithm that improves the consistency of results [

21,

37,

38]. Here, we use deep learning to develop an automated histology image analysis tool to classify fibroglandular breast density in H&E-stained FFPE tissue sections. Whilst this tool is relatively simplistic in comparison to other medical research applications of deep learning, it has the potential to provide a foundation for future applications in research image analysis.

Convolutional neural networks (CNNs) are mature enough to continue to be the most popular deep learning approach in medical vision classification tasks. However, the search is always on to find better models for critical vision classification tasks. Influenced by the success of the transformer structure in language processing tasks, the vision transformer was developed [

15]. Current available models that employ deep learning for breast cancer research have largely used CNNs, and may further benefit from application of the newer ViT models. This study investigated CNN with four different architectures of MobileNet-v2 and different models of ViTs to classify fibroglandular breast density in H&E-stained human breast tissue samples. Both models achieved a high level of accuracy in classifying fibroglandular breast density (ViT model 3: 0.94 and MobileNet Arc 1: 0.93). However, their performance was not identical. MobileNet-v2 using convolutional layers achieved success across each of the evaluated architectural configurations, except MobileNet-Arc 3. The use of depthwise separable convolutions and residual linear bottlenecks substantially reduces the number of parameters and training time [

39]. Additionally, it enables the model to learn effectively from smaller datasets and operate with lower computational resources leading to deployment on mobile and embedded devices [

39]. ViTs, using multi-head self-attention, can learn more characteristic features and deliver a high accuracy score. Four different models of ViT were evaluated, and almost all of them delivered a satisfactory result. The ViT approach for analyzing images is not just understanding individual image patches, but also the relationship between images without considering their distance within an image [

40,

41]. This allows ViT to generalize advanced models in image-analyzing tasks.

In agreement with other studies [

42], we found ViT excels in classifying medical images. Rather than improved general performance, ViT illustrates fewer incorrect predictions in classifying fibroglandular breast density in each class. However, ViT comes with some limitations. It required a larger dataset and a longer timing process. As a result, ViT has a high computational cost for training caused by the intensive use of GPUs (Graphics Processing Units). Both models almost perfectly classified fibroglandular breast tissue samples in classes 1 and 5, while the most challenging classes are class 3 followed by classes 2 and 4. The challenge arises because sometimes there is a narrow distinction between classes. Most errors arise when models classify data points that are close to the boundaries between neighboring classes. For instance, some images that truly belonged to class 3 were incorrectly classified as class 2 or 4, leading to increased prediction errors and diminished sensitivity for this class, which probably could be resolved by increasing the inputted data. Although ViTs achieved better overall performance and potentially is a strong model, it didn’t show a significant improvement over MobileNet-v2 due to the limitation of the database. To enhance the robustness and distinguishing abilities, the models require using larger datasets from different laboratories.

5. Conclusions

This research has developed deep learning models for classification of fibroglandular breast density, implementing MobileNet-v2 and vision transformers. The MobileNet-Acr 1 and model ViT 3 with the accuracy of 0.93 and 0.94, respectively, were identified as the best architectural models. The accuracy and F1-score of the deep learning models (both the ViT and MobileNet) slightly decreased from class 1 and 5 to intermediate classes such as class 3. This would highlight the inherent challenge in the precise definition of class 3, which might include a mix of overlapping characteristics. After performing a comprehensive analysis, we have found ViT offers a slight performance improvement, however it requires higher computational cost to achieve a high accuracy, uses a larger number of parameters, and has a longer processing time. For large datasets where a high accuracy is important, it is recommended to use ViT models to generalize better outcomes while minimising overfitting. However, when limited data are available, a MobileNet-v2, which already has a considerable number of pre-trained parameters that allow for effective learning from a small number of H&E-stained images, is preferred.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.V.I., M.D. and A.F.; methodology, H.H., L.J.H., T.E.H., and W.D.T; software, H.H., A.F. and L.J.H.; validation T.E.H., W.D.T., H.H. and A.F.; formal analysis, H.H., W.V.I., E.S., M.D. and A.F.; investigation, H.H., E.S., W.V.I. and A.F.; resources, W.V.I., H.H. and A.F.; data curation, H.H., L.J.H., T.E.H. and W.D.T; writing—original draft preparation, H.H.; writing—review and editing, W.V.I., E.S., A.F., H.H., T.E.H., W.D.T, L.J.H. and M.D.; visualization, H.H. and A.F.; supervision, W.V.I., E.S. and A.F.; project administration, W.V.I., E.S. and A.F.; funding acquisition, W.V.I., H.H. and A.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by The Hospital Research Foundation, Australia, fellowship awarded to W.V.I., and National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (WDT, TEH; ID 1084416, ID 1130077; ID 2021041). This research is also supported by the Research Training Program (RTP) Scholarship awarded to H.H., and the Robinson Research Institute’s Innovation Seed Funding and the Faculty of Health and Medical Sciences (Adelaide Medical School) Building Research Leaders Award given to A.F.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was approved by the Human Ethics Committee at the University of Adelaide and The Queen Elizabeth Hospital (TQEH Ethics Approval #2011120), and the University of Adelaide (UofA ethics approval #H-2015-175).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data available upon request.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Marie Pickering for technical assistance.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Boyd, N.F. , et al., Breast tissue composition and susceptibility to breast cancer. Journal of the National Cancer Institute 2010, 102, 1224–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yaffe, M.J. , Mammographic density. Measurement of mammographic density. Breast Cancer Research 2008, 10, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyd, N.F. , Mammographic density and risk of breast cancer. American Society of Clinical Oncology Educational Book 2013, 33, e57–e62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Archer, M. , et al., Biological mechanisms and therapeutic opportunities in mammographic density and breast cancer risk. Cancers 2021, 13, 5391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archer, M. , et al., Immune regulation of mammary fibroblasts and the impact of mammographic density. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2022, 11, 799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, C.W. , et al., High mammographic density is associated with an increase in stromal collagen and immune cells within the mammary epithelium. Breast Cancer Research 2015, 17, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliver, A., J. Freixenet, and R. Zwiggelaar. Automatic classification of breast density. in IEEE International Conference on Image Processing 2005. 2005. IEEE.

- Dabeer, S., M. M. Khan, and S. Islam, Cancer diagnosis in histopathological image: CNN based approach. Informatics in Medicine Unlocked 2019, 16, 100231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H. , et al., Deep learning in breast cancer risk assessment: evaluation of convolutional neural networks on a clinical dataset of full-field digital mammograms. Journal of medical imaging 2017, 4, 041304–041304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van der Laak, J., G. Litjens, and F. Ciompi, Deep learning in histopathology: the path to the clinic. Nature medicine 2021, 27, 775–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, T. , et al., Classification of breast cancer histology images using convolutional neural networks. PloS one 2017, 12, e0177544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indraswari, R., R. Rokhana, and W. Herulambang, Melanoma image classification based on MobileNetV2 network. Procedia computer science 2022, 197, 198–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandler, M., et al. Mobilenetv2: Inverted residuals and linear bottlenecks. in Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition. 2018.

- Han, K. , et al., A survey on vision transformer. IEEE transactions on pattern analysis and machine intelligence 2022, 45, 87–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dosovitskiy, A. , et al., An image is worth 16x16 words: Transformers for image recognition at scale. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2010.11929. [Google Scholar]

- Ayana, G. , et al., Vision-transformer-based transfer learning for mammogram classification. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H. , et al., Vision transformers for computational histopathology. IEEE Reviews in Biomedical Engineering 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, S.C. , et al. Understanding data augmentation for classification: when to warp? in 2016 international conference on digital image computing: techniques and applications (DICTA). 2016. IEEE.

- Johnson, J.M. and T.M. Khoshgoftaar, Survey on deep learning with class imbalance. Journal of Big Data 2019, 6, 1–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J. , et al. Imagenet: A large-scale hierarchical image database. in 2009 IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition. 2009. Ieee.

- Rigaud, B. , et al., Deep learning models for automated assessment of breast density using multiple mammographic image types. Cancers 2022, 14, 5003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, R.L. N. Giaquinto, and A. Jemal, Cancer statistics 2024. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians 2024, 74. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y. , et al., Global trends and forecasts of breast cancer incidence and deaths. Scientific Data 2023, 10, 334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCulloch, W.S. and W. Pitts, A logical calculus of the ideas immanent in nervous activity. The bulletin of mathematical biophysics 1943, 5, 115–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ching, T. , et al., Opportunities and obstacles for deep learning in biology and medicine. Journal of the royal society interface 2018, 15, 20170387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakator, M. and D. Radosav, Deep learning and medical diagnosis: A review of literature. Multimodal Technologies and Interaction 2018, 2, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yari, Y., T. V. Nguyen, and H.T. Nguyen, Deep learning applied for histological diagnosis of breast cancer. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 162432–162448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.E. , et al., Transfer learning for medical image classification: a literature review. BMC medical imaging 2022, 22, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lång, K. , et al., Artificial intelligence-supported screen reading versus standard double reading in the Mammography Screening with Artificial Intelligence trial (MASAI): a clinical safety analysis of a randomised, controlled, non-inferiority, single-blinded, screening accuracy study. The Lancet Oncology 2023, 24, 936–944. [Google Scholar]

- Ingman, W.V. , et al., Artificial intelligence improves mammography-based breast cancer risk prediction. Trends in Cancer.

- Salim, M. , et al., AI-based selection of individuals for supplemental MRI in population-based breast cancer screening: the randomized ScreenTrustMRI trial. Nature Medicine 2024, 30, 2623–2630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shmatko, A. , et al., Artificial intelligence in histopathology: enhancing cancer research and clinical oncology. Nature cancer 2022, 3, 1026–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandbank, J. , et al., Validation and real-world clinical application of an artificial intelligence algorithm for breast cancer detection in biopsies. NPJ Breast Cancer 2022, 8, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandomkar, Z., C. Brennan, and C. Mello-Thoms, Computer-based image analysis in breast pathology. Journal of pathology informatics 2016, 7, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hekler, A. , et al., Pathologist-level classification of histopathological melanoma images with deep neural networks. European Journal of Cancer 2019, 115, 79–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberman, L. and J. H. Menell, Breast imaging reporting and data system (BI-RADS). Radiologic Clinics 2002, 40, 409–430. [Google Scholar]

- Mohamed, A.A. , et al., A deep learning method for classifying mammographic breast density categories. Medical physics 2018, 45, 314–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lehman, C.D. , et al., Mammographic breast density assessment using deep learning: clinical implementation. Radiology 2019, 290, 52–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiang, Q. et al. Fruit image classification based on Mobilenetv2 with transfer learning technique. in Proceedings of the 3rd international conference on computer science and application engineering. 2019.

- Sriwastawa, A. and J.A. Arul Jothi, Vision transformer and its variants for image classification in digital breast cancer histopathology: A comparative study. Multimedia Tools and Applications 2024, 83, 39731–39753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S. , et al., Transformers in vision: A survey. ACM computing surveys (CSUR) 2022, 54, 1–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamshad, F. , et al., Transformers in medical imaging: A survey. Medical Image Analysis 2023, 88, 102802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Examples of Haematoxylin and Eosin-stained breast tissue specimens across five density classes. a) Breast tissue with 0-10% fibroglandular tissue, representing class 1. b) Breast tissue with 11-25% fibroglandular tissue, representing class 2. c) Breast tissue with 26-50% fibroglandular tissue, representing class 3. d) Breast tissue with 51-75% fibroglandular tissue, representing class 4. e) Breast tissue with 76-100% fibroglandular tissue representing class 5.

Figure 1.

Examples of Haematoxylin and Eosin-stained breast tissue specimens across five density classes. a) Breast tissue with 0-10% fibroglandular tissue, representing class 1. b) Breast tissue with 11-25% fibroglandular tissue, representing class 2. c) Breast tissue with 26-50% fibroglandular tissue, representing class 3. d) Breast tissue with 51-75% fibroglandular tissue, representing class 4. e) Breast tissue with 76-100% fibroglandular tissue representing class 5.

Figure 2.

Breast density distribution a) before and b) after undersampling balancing.

Figure 2.

Breast density distribution a) before and b) after undersampling balancing.

Figure 3.

Schematic of the architecture of the MobileNet-v2 model. The top layer of the transferred model was removed, and a number of various layers were added to allow for the trainability on the H&E-stained breast tissue sample.

Figure 3.

Schematic of the architecture of the MobileNet-v2 model. The top layer of the transferred model was removed, and a number of various layers were added to allow for the trainability on the H&E-stained breast tissue sample.

Figure 4.

Overview of the architecture of the vision transformer model: (a) H&E-stained image patching, (b) linear projection, embedding, and position embedding, followed by processing within the transformer encoder and MLP head, (c) schematic of a transformer encoder consisting of normalisation layer, multi-head self-attention (MHSA), and ML

Figure 4.

Overview of the architecture of the vision transformer model: (a) H&E-stained image patching, (b) linear projection, embedding, and position embedding, followed by processing within the transformer encoder and MLP head, (c) schematic of a transformer encoder consisting of normalisation layer, multi-head self-attention (MHSA), and ML

Figure 5.

Accuracy score versus epoch for the training and validation data using MobileNet-Arc 1 configuration.

Figure 5.

Accuracy score versus epoch for the training and validation data using MobileNet-Arc 1 configuration.

Figure 6.

Loss versus epochs for the training and validation data using the MobileNet-Arc 1 configuration.

Figure 6.

Loss versus epochs for the training and validation data using the MobileNet-Arc 1 configuration.

Figure 7.

Accuracy, average precision, mean sensitivity (recall) and average F-1 score of the MobileNet-v2 model with four different architectures on the test H&E-stained images.

Figure 7.

Accuracy, average precision, mean sensitivity (recall) and average F-1 score of the MobileNet-v2 model with four different architectures on the test H&E-stained images.

Figure 8.

Receiver operating characteristic curve of the transferred and modified MobileNet-Arc 1 model for the five different breast density classes. (a) (b) A zoomed-in overview of the ROC curve, focusing on the TPR ranging from 0.75 to 1.

Figure 8.

Receiver operating characteristic curve of the transferred and modified MobileNet-Arc 1 model for the five different breast density classes. (a) (b) A zoomed-in overview of the ROC curve, focusing on the TPR ranging from 0.75 to 1.

Figure 9.

Confusion matrix of the MobileNet-v2 model (MobileNet-Arc 1) on the test dataset.

Figure 9.

Confusion matrix of the MobileNet-v2 model (MobileNet-Arc 1) on the test dataset.

Figure 10.

Accuracy score versus epoch for the training and validation data using the ViT model 3.

Figure 10.

Accuracy score versus epoch for the training and validation data using the ViT model 3.

Figure 11.

Loss versus epoch for the training and validation H&E-stained images using the ViT model 3.

Figure 11.

Loss versus epoch for the training and validation H&E-stained images using the ViT model 3.

Figure 12.

Accuracy, average precision, mean sensitivity (recall) and average F-1 score of the vision transformer model with four different architectures on the test H&E-stained images.

Figure 12.

Accuracy, average precision, mean sensitivity (recall) and average F-1 score of the vision transformer model with four different architectures on the test H&E-stained images.

Figure 12.

ROC curve of the vision transformer model for the five different fibroglandular breast density classes. (a) The ROC curve indicates the TPR within the range of 0 and 1 versus the FPR. (b) A zoomed-in overview of the ROC curve, focusing on the TPR ranging from 0.75 to 1. This chart provides more details on the performance of the ViT model 3 at higher TPRs.

Figure 12.

ROC curve of the vision transformer model for the five different fibroglandular breast density classes. (a) The ROC curve indicates the TPR within the range of 0 and 1 versus the FPR. (b) A zoomed-in overview of the ROC curve, focusing on the TPR ranging from 0.75 to 1. This chart provides more details on the performance of the ViT model 3 at higher TPRs.

Figure 13.

Confusion matrix of the Vit model 3 for the unseen test H&E-stained images of human breast tissue.

Figure 13.

Confusion matrix of the Vit model 3 for the unseen test H&E-stained images of human breast tissue.

Figure 14.

Confusion matrix of the ViT model 3 for the unseen validation H&E-stained images of human breast tissue.

Figure 14.

Confusion matrix of the ViT model 3 for the unseen validation H&E-stained images of human breast tissue.

Table 1.

Hyperparameters of the MobileNet-v2 model used for the fibroglandular breast density classification of H&E-stained images.

Table 1.

Hyperparameters of the MobileNet-v2 model used for the fibroglandular breast density classification of H&E-stained images.

| Hyperparameter |

Value |

| Batch size |

32 |

| Maximum allowable number of epochs |

200 |

| Patience |

10 |

| Learning rate |

0.001 |

| Learning rate scheduler |

Exponential |

| Step size of the learning rate scheduler |

1 |

| Learning rate decay rate |

0.9 |

| Loss function |

Categorical cross entropy |

| Optimiser |

Adam |

Table 2.

Details of layers and the number of trainable and all parameters for each architectural model of MobileNet-v2.

Table 2.

Details of layers and the number of trainable and all parameters for each architectural model of MobileNet-v2.

|

MobileNet architecture

|

Added GAvgP-2D layers

|

Added dense layers

|

Added dropout layers

|

Added BatchNorm layers

|

Added Conv2D layers

|

Added MaxP2D layers

|

|

MobileNet-Arc 1

|

1 |

3 |

3 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

|

Number of trainable parameters: 175,365

|

|

|

|

|

Number of total parameters: 2,436,165

|

|

|

|

|

|

MobileNet-Arc 2

|

1 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

|

Number of trainable parameters: 84,869

|

|

|

|

|

|

Number of total parameters: 2,345,413

|

|

|

|

|

|

MobileNet-Arc 3

|

1 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

|

Number of trainable parameters: 741,957

|

|

|

|

|

|

Number of total parameters: 3,000,069

|

|

|

|

|

|

MobileNet-Arc 4

|

1 |

5 |

5 |

3 |

0 |

0 |

|

Number of trainable parameters: 177,861

|

|

|

|

|

|

Number of total parameters: 2,438,789

|

|

|

|

|

Table 3.

Precision, sensitivity, and F1-score of the transferred MobileNet-v2 model with four different architectures of the added layers.

Table 3.

Precision, sensitivity, and F1-score of the transferred MobileNet-v2 model with four different architectures of the added layers.

|

Model architecture

|

Breast density score (class)

|

Precision

|

Recall (sensitivity)

|

F1-score

|

|

MobileNet-Arc 1

|

1 |

0.95 |

0.95 |

0.95 |

| |

2 |

0.91 |

0.92 |

0.92 |

| |

3 |

0.91 |

0.86 |

0.89 |

| |

4 |

0.90 |

0.93 |

0.92 |

| |

5 |

0.96 |

0.96 |

0.96 |

|

MobileNet-Arc 2

|

1 |

0.96 |

0.93 |

0.95 |

| |

2 |

0.89 |

0.92 |

0.90 |

| |

3 |

0.88 |

0.88 |

0.88 |

| |

4 |

0.92 |

0.88 |

0.90 |

| |

5 |

0.94 |

0.96 |

0.95 |

|

MobileNet-Arc 3

|

1 |

0.88 |

0.91 |

0.89 |

| |

2 |

0.82 |

0.80 |

0.81 |

| |

3 |

0.73 |

0.84 |

0.78 |

| |

4 |

0.89 |

0.73 |

0.80 |

| |

5 |

0.88 |

0.90 |

0.89 |

|

MobileNet-Arc 4

|

1 |

0.95 |

0.95 |

0.95 |

| |

2 |

0.89 |

0.92 |

0.91 |

| |

3 |

0.91 |

0.87 |

0.89 |

| |

4 |

0.89 |

0.92 |

0.91 |

| |

5 |

0.95 |

0.94 |

0.95 |

Table 4.

Hyperparameters of the ViT model used for the breast density classification of H&E-stained images of human breast.

Table 4.

Hyperparameters of the ViT model used for the breast density classification of H&E-stained images of human breast.

|

Hyperparameter

|

Value

|

|

Batch size

|

64 |

|

Maximum number of epochs

|

75 |

|

Patience

|

15 |

|

Learning rate

|

0.001 |

|

Learning rate scheduler

|

StepLR |

|

Step size of the learning rate scheduler

|

1 |

|

learning rate decay factor (gamma)

|

0.7 |

|

Loss function

|

Cross Entropy Loss |

|

Optimiser

|

Adam |

Table 5.

The details of the architecture of the four different ViT models. The total number of trainable parameters was given for each model architecture.

Table 5.

The details of the architecture of the four different ViT models. The total number of trainable parameters was given for each model architecture.

|

Model

|

Patch size

|

Embedding dimension

|

Depth

|

Heads

|

MLP dimension

|

Dropout

|

Embedding dropout

|

|

ViT model 1

|

16 |

64 |

12 |

8 |

64 |

0.1 |

0.1 |

|

Number of trainable parameters: 1740549

|

|

|

|

|

|

ViT model 2

|

32 |

32 |

12 |

8 |

64 |

0.1 |

0.1 |

|

Number of trainable parameters: 945061

|

|

|

|

|

|

ViT model 3

|

16 |

64 |

6 |

4 |

32 |

0.05 |

0.05 |

|

Number of trainable parameters: 484293

|

|

|

|

|

|

ViT model 4

|

16 |

64 |

3 |

2 |

16 |

0.02 |

0.02 |

|

Number of trainable parameters: 169653

|

|

|

|

|

Table 6.

Precision, sensitivity, and F1-score of the ViT model with four different architectures.

Table 6.

Precision, sensitivity, and F1-score of the ViT model with four different architectures.

|

Model

|

Breast density class

|

Precision

|

Recall (sensitivity)

|

F1-score

|

|

ViT model 1

|

1 |

0.97 |

0.88 |

0.92 |

| |

2 |

0.91 |

0.92 |

0.91 |

| |

3 |

0.91 |

0.95 |

0.93 |

| |

4 |

0.94 |

0.93 |

0.93 |

| |

5 |

0.96 |

0.99 |

0.97 |

|

ViT model 2

|

1 |

0.86 |

0.95 |

0.91 |

| |

2 |

0.85 |

0.88 |

0.86 |

| |

3 |

0.92 |

0.84 |

0.87 |

| |

4 |

0.88 |

0.90 |

0.89 |

| |

5 |

0.96 |

0.91 |

0.93 |

|

ViT model 3

|

1 |

0.90 |

0.98 |

0.94 |

| |

2 |

0.94 |

0.91 |

0.92 |

| |

3 |

0.96 |

0.95 |

0.95 |

| |

4 |

0.90 |

0.94 |

0.92 |

| |

5 |

0.98 |

0.91 |

0.95 |

|

ViT model 4

|

1 |

0.93 |

0.95 |

0.94 |

| |

2 |

0.85 |

0.94 |

0.90 |

| |

3 |

0.96 |

0.84 |

0.90 |

| |

4 |

0.89 |

0.91 |

0.90 |

| |

5 |

0.96 |

0.94 |

0.95 |

Table 7.

Validation study: precision, sensitivity, and F1-score of the ViT model tested on H&E images generated in a different laboratory.

Table 7.

Validation study: precision, sensitivity, and F1-score of the ViT model tested on H&E images generated in a different laboratory.

Performance

metrics* |

Breast density class

|

Precision

|

Recall (sensitivity)

|

F1-score

|

| |

1 |

0.92 |

1.0 |

0.96 |

| |

2 |

1.0 |

0.92 |

0.96 |

| |

3 |

0.85 |

0.92 |

0.88 |

| |

4 |

1.0 |

0.83 |

0.91 |

| |

5 |

0.92 |

1.0 |

0.96 |

|

Micro-average

|

|

0.94 |

0.93 |

0.93 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).