1. Introduction

The most frequently diagnosed malignant neoplasm in women is breast cancer, which also stands as the second leading cause of cancer deaths in females worldwide [

1,

2]. Detecting the disease at an early stage is vital for better therapeutic outcomes and improved survival rates. An array of imaging techniques, including mammography, MRI, and ultrasonography are fundamental to the detection of irregularities within breast tissue. Recent advancements have increasingly prioritized the application of medical imaging modalities for the early identification of breast neoplasms. [

3]. The advent of deep learning has significantly advanced medical imaging analysis, enabling precise and automated identification of breast malignancies. Convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and related deep learning frameworks excel in discerning high-dimensional feature representations in medical imaging, contributing to a reduction in diagnostic variability. The application of transfer learning, utilizing pre-trained deep neural networks such as VGG, ResNet, or Inception, empowers enhanced model performance by transferring complex feature extractors trained on vast, generic datasets to address the challenges of limited labeled medical imaging data. In our previous study [

4], a systematic review and meta-analysis investigated radiomics-driven deep learning and machine learning algorithms for breast cancer diagnosis, evidencing improved diagnostic precision and specificity, especially in mammographic and MRI-based imaging. Despite these advancements, significant limitations remain. Our previous study highlighted challenges such as heterogeneity in medical image features, limited availability of large annotated datasets, and limited model generalizability across heterogeneous imaging protocols and diverse patient cohorts poses a significant challenge.

Feature extraction is significant for addressing these issues because it allows the analysis, measurement, and identification of distinct attributes within images that indicate the existence or advancement of cancer [

5,

6]. On the other hand, because of the complex and critical nature of medical data, medical image feature extraction requires innovative approaches[

7]. Radiomics analysis is an effective feature engineering approach in medical image analysis and is crucial in improving patient outcomes. Recent studies [

8,

9,

10,

11] have conducted radiomic analysis and extracted radiomic features to advance medical image analysis. Radiomics techniques employ sophisticated algorithms to extract quantitative characteristics from medical images, such as the shape, texture, size, and intensity of tumors [

12], which can then be used to develop prediction models for various medical image classification problems. Radiomics feature extraction, which provides interpretable, clinically relevant features, complements deep feature extraction, where deep learning models automatically derive hierarchical and abstract representations from imaging data. This synergy enhances diagnostic accuracy by combining radiomic’s quantitative insights into tumor characteristics with deep feature’s ability to capture complex, non-linear patterns [

13].

Early identification of breast cancer faces significant challenges, primarily because of the shortage of manifold datasets necessary for effectively training predictive models. This limited representation can hinder the ability of models to generalize across different populations, resulting in inaccuracies. Additionally, class imbalances within the datasets can further exacerbate these issues, leading to biased predictions that may not accurately reflect the reality of all patient groups. As a result, these obstacles can compromise the effectiveness of early detection efforts for combating breast cancer. Integrating deep learning pretrained models with radiomics features addresses key challenges in breast cancer detection by leveraging their complementary strengths. Proper data augmentation and pre-trained models mitigate data limitations through transfer learning and extract complex, high-level features from images, whereas radiomics provides reproducible, standardized metrics to reduce subjectivity. This combination enhances the model accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity by integrating learned and handcrafted features into hybrid frameworks. Automating both approaches speeds up the analysis, minimizes time inefficiencies, and facilitates real-time application. This synergy enhances the reliability, consistency, and performance, advancing the precision and personalization of breast cancer detection.

Therefore, this research will lead to the following enhancements in performance and reliability:

We utilized advanced data augmentation techniques to tackle the issues of limited and imbalanced datasets, resulting in enhanced model robustness and generalization.

Perform feature engineering by integrating multimodal features (radiomics and deep features) from the augmented training dataset. Radiomics feature selection was conducted using RFE (with Random Forest and Logistic Regression), ANOVA F-test, LASSO, and mutual information, alongside embedded approaches leveraging XGBoost, LightGBM, and CatBoost with GPU acceleration. The most informative features were subsequently integrated with deep features to build a unified multimodal feature space for final model development.

Conducted a comprehensive analysis of 13 transfer learning models, highlighting their comparative performance and demonstrating significant improvements in the accuracy of breast cancer detection.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section II synthesizes the relevant literature and highlights critical gaps in current knowledge. Section III explicates the research methodology utilized. Section IV details the outcomes of the study concerning transfer learning models, comparing the findings with existing research while addressing the associated challenges and limitations. Finally, Section V summarizes the study and proposes future research pathways.

2. Literature Review

Khourdifi et al. [

14] designed an ensemble deep learning technique for the earlier identification of breast cancer, using radiomics and transfer learning techniques. Their method employed standardized preprocessing for mammographic images sourced from the CBIS-DDSM and INbreast datasets, enhancing both interpretability and robustness. The ensemble model achieved an impressive accuracy of 89.5% along with a remarkable specificity of 90.2% when tested on the CBIS-DDSM dataset.

Pham et al. [

15] introduced an architecture based on EfficientNet, incorporating image enhancement techniques to improve breast cancer prediction. They presented a fine-tuning procedure for pre-trained models, including ResNet-50, EfficientNet-B5, and Xception.The strategy incorporates a variety of preprocessing methods and leverages transfer learning to extract intrinsic markers, which positively contributes to improving model dependability and enhancing classification accuracy. The authors compared three ensemble methods—averaging, weighted averaging, and voting—achieving up to 91.36% accuracy for mass/calcification classification and 76.79% for benign/malignant classification.

Chugh et al. [

16] introduced TransNet, a model that combines classical machine learning techniques with transfer learning paradigms. Their study demonstrated that transfer learning significantly enhances model generalizability, allowing for the detection of subtle features in mammograms. For feature extraction and classification, deep learning methods utilize neural network classifiers such as MobileNet, VGG16, VGG19, ResNet50, ResNet152, and DenseNet169. Among the evaluated models, MobileNet, ResNet50, and DenseNet169 achieved superior performance, each reaching an accuracy of 97% (±2%) on both the training and test sets.

Subha et al. [

17] developed a depth-wise convolutional neural network (CNN) specifically designed for mammographic classification. Their study utilized pre-trained models, demonstrating enhanced efficiency in breast lesion classification. The proposed method achieved an accuracy of 95 percent. Gujar et al. [

18] employed radiomics-based convolutional neural network (CNN) models utilizing transfer learning for the classification of breast lesions. Their research demonstrated that the integration of radiomics features with deep learning significantly enhances both model sensitivity and specificity. Among the models tested, ResNet50 exhibited the highest performance, performing a classification test accuracy of 0.72 and an Area Under Curve (AUC) of 0.71 (95% CI: 0.66-0.75). In contrast, AlexNet attained a test accuracy of 0.64 and an AUC of 0.61.

Ahmed et al. [

19] focused on Explainable AI (XAI) models by integrating radiomics with convolutional neural network (CNN) architectures. By enhancing the visualization of mammographic features, they contributed to more transparent decision-making processes. Their evaluation yielded promising results, demonstrating model reliability and interpretability improvements. The Connected-SegNets model achieved a maximum Dice score of 96.34% on the INbreast dataset, 92.86% on the CBIS-DDSM dataset, and 92.25% on a private dataset.

2.1. Research Gap

Despite numerous studies in the field of breast cancer detection, there are still specific gaps that need to be addressed, particularly in the areas of data limitation and medical image feature engineering. Existing research has made significant strides in these areas; however, more refined techniques are necessary to enhance model robustness and generalizability further.

This study addresses these gaps by applying data augmentation techniques to balance the dataset and enhance model learning while combining radiomics and deep learning-based features in a unified framework.

We employed 13 transfer learning models, incorporating deep and extracted radiomics features, to assess their performance in early breast cancer detection. By integrating these two complementary techniques, our methodology enhances the feature extraction process and optimizes the training of the transfer learning models. This combined approach allows the models to benefit from both traditional medical image processing techniques (radiomics) and the powerful pattern recognition capabilities of deep learning, ultimately improving the model’s performance and robustness.

3. Materials and Methods

Our proposed approach organizes the research process into several distinct phases. The methodology commenced with the acquisition and analysis of breast imaging data. Image data was collected from the CBIS-DDSM [

20] dataset and prepared through essential analysis steps. The data analysis phase included fixing image paths, determining the length of the dataset, mapping labels, counting the instances with respect to labels, and displaying image data. During the analysis, we identified an imbalanced dataset concerning labels (Benign, Malignant). Our next step involved applying image processing and data augmentation. In this step, we ensure that images were prepared to comply with the requirements of the pre-trained model and pyradiomics. We also carried out data augmentation to address the imbalanced dataset issue. After that, our augmented dataset was split into three subsets: training, validation, and testing, with a distribution ratio of 80% for training, 10% for validation, and 10% for testing. In the feature engineering phase, we employed a two approaches, radiomics features and deep learning features approach. We extracted features for both approaches from our training data. Radiomics features were derived using the PyRadiomics library. For deep learning features, we utilized pretrained models to extract high-level representations. To optimize the radiomics feature set, feature selection was performed using RFE (Random Forest, Logistic Regression), ANOVA F-test, LASSO, and mutual information criteria. In addition, embedded selection was explored with XGBoost, LightGBM, and CatBoost using GPU acceleration. The selected features were then combined with deep features to create a unified multimodal feature space for downstream model training. All features were standardized using z-score normalization after missing value imputation with a K-Nearest Neighbors Imputer (k=5). In the final phase, we implemented 13 transfer learning models for breast cancer early detection.We rigorously evaluated the model’s implementation using metrics such as accuracy, precision, recall, and F1 score, ensuring that it is accurate and reliable for early breast cancer detection. This structured approach, coupled with the rigorous assessment, enhances diagnostic precision and robustness, providing a solid foundation for accurate and actionable cancer predictions. Our proposed methodology has been implemented and can be accessed through the GitHub repository [

21].

3.1. Dataset

We initially collected data from the well-known dataset CBIS-DDSM [

20], which contained 2,620 mammography images. This collection comprises 2620 mammography studies, encompassing normal, benign, and malignant patients.

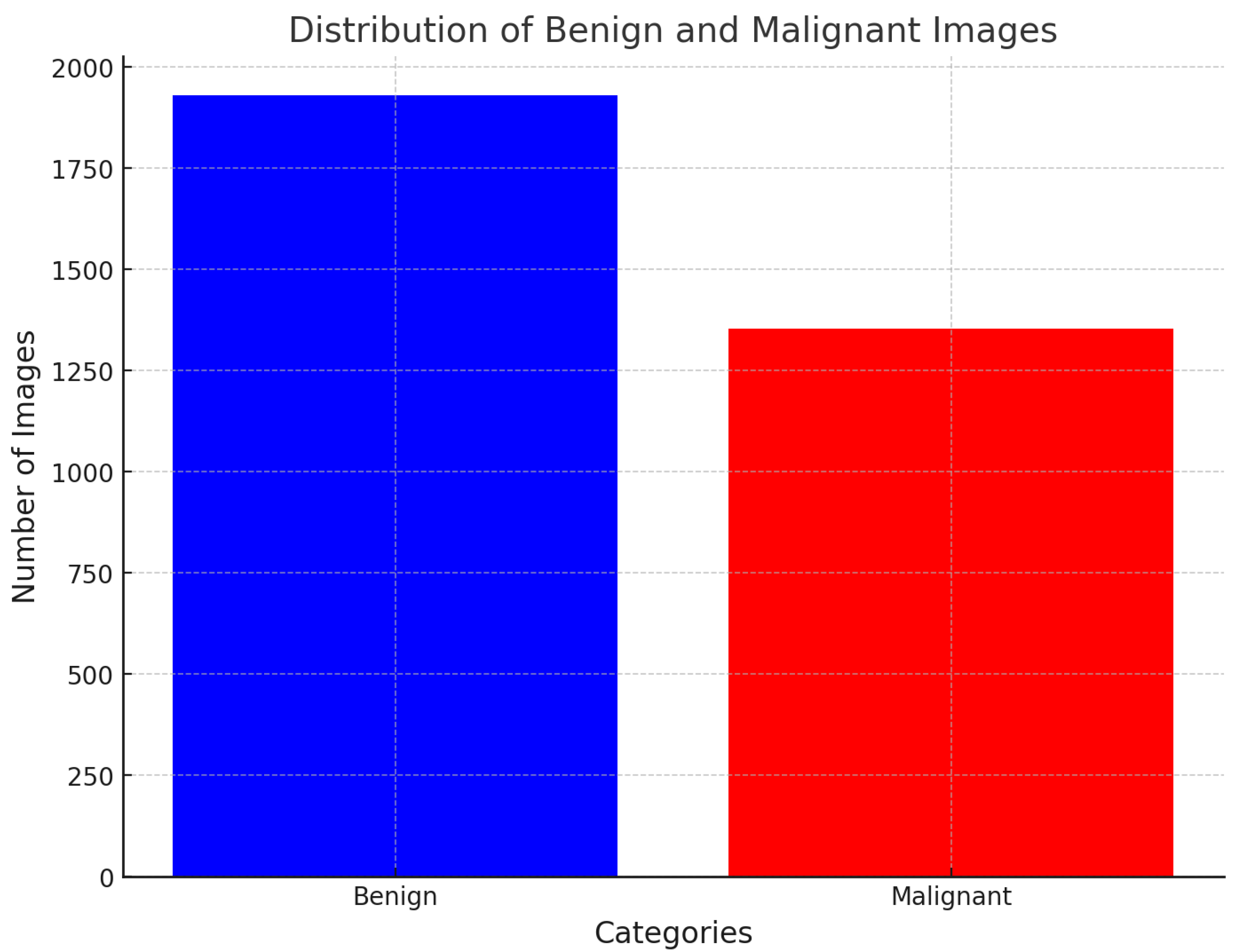

Figure 1 illustrates the data distribution throughout the dataset. The dataset comprises updated ROI segmentation and bounding boxes, along with the pathological assessment for the training data.

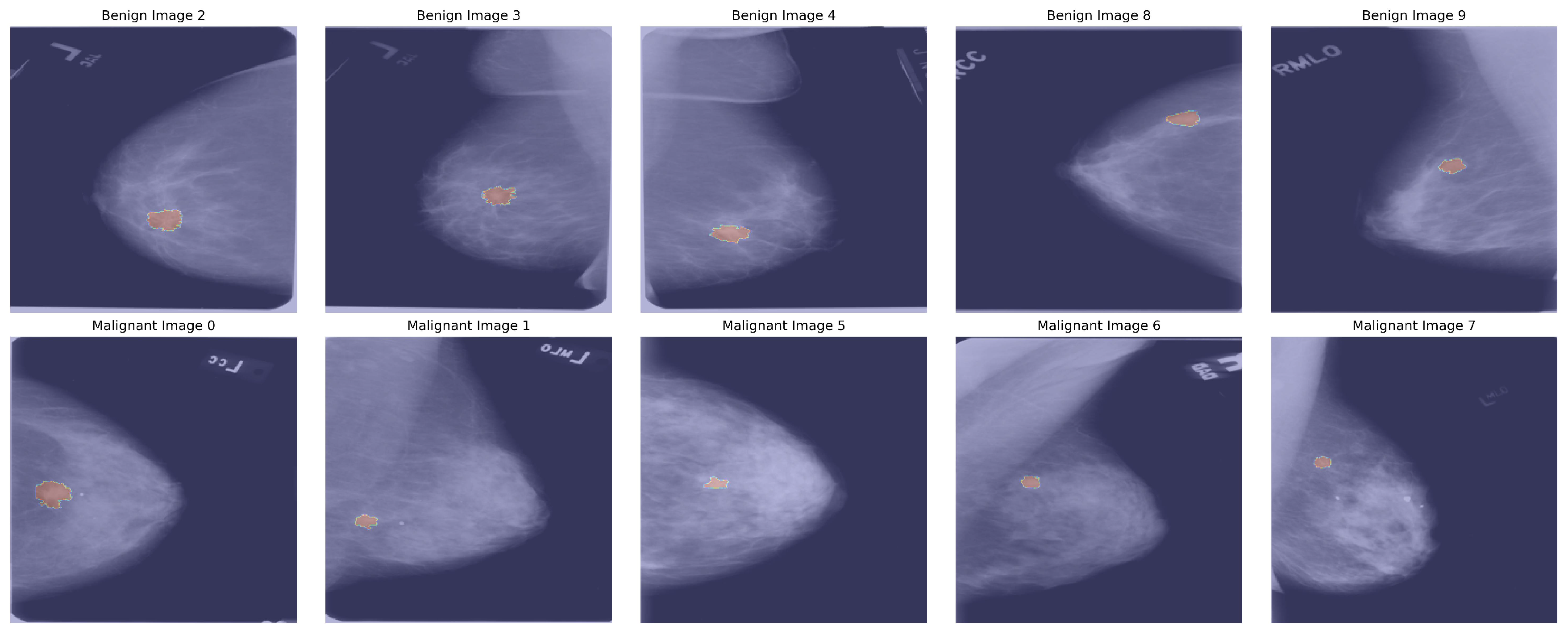

Figure 2 describes mamographic images with segmented ROI.

3.2. Image Pre-Processing and Data Augmentation

After collecting data from the dataset, we applied several image processing techniques to ensure consistency and quality across the images. First, we rescaled each image to a standardized resolution, ensuring uniformity and compatibility in subsequent feature extraction and model training stages. We then performed normalization, standardizing pixel intensity values to reduce variations caused by lighting or contrast differences, allowing the model to focus on essential features rather than inconsistencies. To enhance clarity, we applied noise reduction using Gaussian, minimizing background noise and artifacts that could interfere with accurate feature extraction. Finally, we used anatomical alignment to orient the images to a common reference point, ensuring that comparable regions are captured across images. Together, these processing steps refined the dataset, enabling reliable, high-quality input for analysis.

We employed data augmentation techniques to mitigate the imbalance in the original dataset.

Table 1 provides an overview of the CBIS-DDSM dataset, detailing the distribution of images across various labels. Each label includes a specific number of both original and augmented images. The augmentation pipeline 1 includes several transformations: random horizontal and vertical flips to simulate different orientations, random adjustments in brightness, contrast, saturation, and hue to mimic lighting and color variations. In addition, although in the image processing stage, we applied a Gaussian filter to reduce background noise and artifacts to improve image clarity. Subsequently, during this phase, a Gaussian filter is applied with a random standard deviation to introduce blur effects to simulate real-world imaging variations, while random cropping followed by resizing simulates zoom-level variations. These strategies aim to mitigate the imbalance and enhance the model’s generalization capabilities. After augmentation, a count of 8498 images per label was generated. The dataset is split into three subsets: training, validation, and testing, with a distribution ratio of 80% for training, 10% for validation, and 10% for testing. Due to mini-batches with a batch size of 32, the allocation of samples to each subset slightly deviated from the intended split. As a result, the size of the final datasets was as follows: training: 13600 images(425 batches of 32 samples each), validation: 1700 images(53 batches of 32 samples each), testing: 1700 images (53 batches of 32 samples each). The dataset was shuffled prior to splitting to ensure fairness and consistency, and the same random seed was utilized in each run. Furthermore, samples that could not form complete batches were excluded, minimizing potential bias in the dataset.

|

Algorithm 1:Image augmentation pipeline |

-

Require:

Image I

-

Ensure:

Augmented Image

- 1:

- 2:

- 3:

- 4:

- 5:

- 6:

- 7:

- 8:

- 9:

- 10:

- 11:

- 12:

- 13:

- 14:

return Augmented Image

|

3.3. Feature Engineering

3.3.1. Radiomics Features

In this phase, we conducted feature engineering, meticulously dividing it into feature extraction with radiomics feature selection and combination to create a robust feature set. During feature extraction, we gathered a comprehensive range of radiomic features from segmented Regions of Interest (ROIs). Algorithm 2 describe the radiomics extraction process. These features included included first-order statistics (e.g., percentiles, energy, entropy), shape-based descriptors (e.g., elongation, major axis length, perimeter), and higher-order texture features derived from standard radiomics matrices such as the gray-level run length matrix (GLRLM), gray-level size zone matrix (GLSZM), Gray-Level Dependence Matrix(GLDM),gray-level co-occurrence matrix (GLCM), and neighborhood gray-tone difference matrix (NGTDM). To ensure precision and consistency, we utilized the pyradiomics library [

22], which is specifically designed for extracting diverse radiomic features critical in medical imaging analysis. By combining radiomic features extracted through these methods, our approach ensures the integration of diverse quantitative descriptors, thereby creating a comprehensive feature set for analysis.

|

Algorithm 2:Radiomics Feature Extraction |

-

Require:

Dataframe with columns: patient_id, image_file_path, ROI_mask_file_path, labels -

Ensure:

Radiomics features DataFrame

- 1:

- 2:

- 3:

- 4:

for each row in do

- 5:

- 6:

- 7:

- 8:

if then

- 9:

- 10:

- 11:

- 12:

- 13:

- 14:

- 15:

- 16:

- 17:

return

|

3.3.2. Radiomics Feature Selection

Feature selection is critical for radiomics features due to the high-dimensional nature of radiomics data. This high dimensionality can lead to overfitting, where models perform well on training data but fail to generalize to new data, especially given the often limited sample sizes in medical studies. Feature selection mitigates the curse of dimensionality by reducing the feature space, improving model performance, robustness, and generalizability. In our study, we systematically compared a broad range of supervised feature selection techniques with varying subset sizes, Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) was applied using Random Forest and Logistic Regression base classifiers, selecting 10, 20, 50, and 100 features. In addition, RFECV automatically determined the optimal number of features, resulting in 74 features for Random Forest and 647 for Logistic Regression. Univariate Feature Selection based on the ANOVA F-statistic was performed via SelectKBest with 10, 20, 50, and 100 features. LASSO (LassoCV) was applied, yielding 90 and 157 selected features on five-fold cross-validation configuration. Mutual Information feature ranking was also evaluated, retaining the top 50, 100, and 200 features. Embedded methods using tree-based models with GPU acceleration were explored through XGBoost, LightGBM, and CatBoost, with feature subset sizes of 50, 100, and 200. The methods and their corresponding number of selected features are summarized in

Table 2.

These diverse feature selection pipelines aimed to identify the most discriminative and robust subsets, which were subsequently integrated with deep features to build a unified multimodal feature space for final model development.

3.3.3. Deep Learning Features

In addition to radiomics features, we utilized GlobalAveragePooling2D for deep learning feature extraction. GlobalAveragePooling2D is an efficient method for transitioning from convolutional layers to fully connected layers, enabling effective feature extraction while reducing the risk of overfitting. This operation condenses the spatial dimensions of the feature maps by computing the average of all spatial positions for each feature map channel. Mathematically, for a feature map

with dimensions

, where

J = height,

E = width, and

X = number of channels, the global average pooling operation computes the output for the

c-th channel as:

Here:

= activation value at position in the c-th feature map.

= resultant scalar for the c-th channel after applying the global average pooling.

This operation ensures that each channel contributes a single value to the final feature vector, significantly reducing the dimensionality while retaining global spatial information. By summarizing the feature maps into compact vectors, GlobalAveragePooling2D enhances the model’s generalization ability and reduces the risk of overfitting. The extracted deep features are combined with radiomics features to form a comprehensive input representation, enabling the model to achieve high classification accuracy.

3.4. Multimodal Feature Preparation

After independently processing both radiomics and deep features, we applied several data harmonization steps to prepare them for fusion and downstream machine learning. First, missing values in the radiomics features are addressed using a KNN imputer with k = 5, which leverages neighboring samples to estimate missing entries. The same KNN imputer is also applied to the deep features to handle potential missing activations that could occur if, for instance, specific images failed to process fully. Algorithm 3 describe the multimodal feature preparation. Once imputed, both radiomics and deep features undergo standard normalization using a StandardScaler (z-score standardization) to ensure comparable scales across heterogeneous features. This is crucial because radiomics features (often with units such as pixel intensity) and deep features (unitless activation patterns) can have substantially different distributions otherwise.

|

Algorithm 3:Multimodal Feature Preparation |

-

Require:

Radiomics feature matrix R, deep feature matrix D, target labels y

-

Ensure:

Preprocessed and fused feature matrix F

- 1:

Apply KNN imputation with to R, producing

- 2:

Apply KNN imputation with to D, producing

- 3:

Standardize with zero mean and unit variance, yielding

- 4:

Standardize with zero mean and unit variance, yielding

- 5:

Rename columns of as deep_feature_i for traceability - 6:

Concatenate and horizontally to form F

- 7:

Align F rows to patient IDs from y

- 8:

returnF

|

3.5. Transfer Learning Models

In our study, we used 13 transfer learning models, such as ResNet(50, 101, 152, 50V2, 101V2, and 152V2), DenseNet (121, 169, 201), VGG (16 and 19), MobileNet, and InceptionV3. We achieved the highest accuracy for the ResNet152 model. We utilized the ResNet152 architecture with custom layers to integrate radiomics features for improved performance in medical image classification.

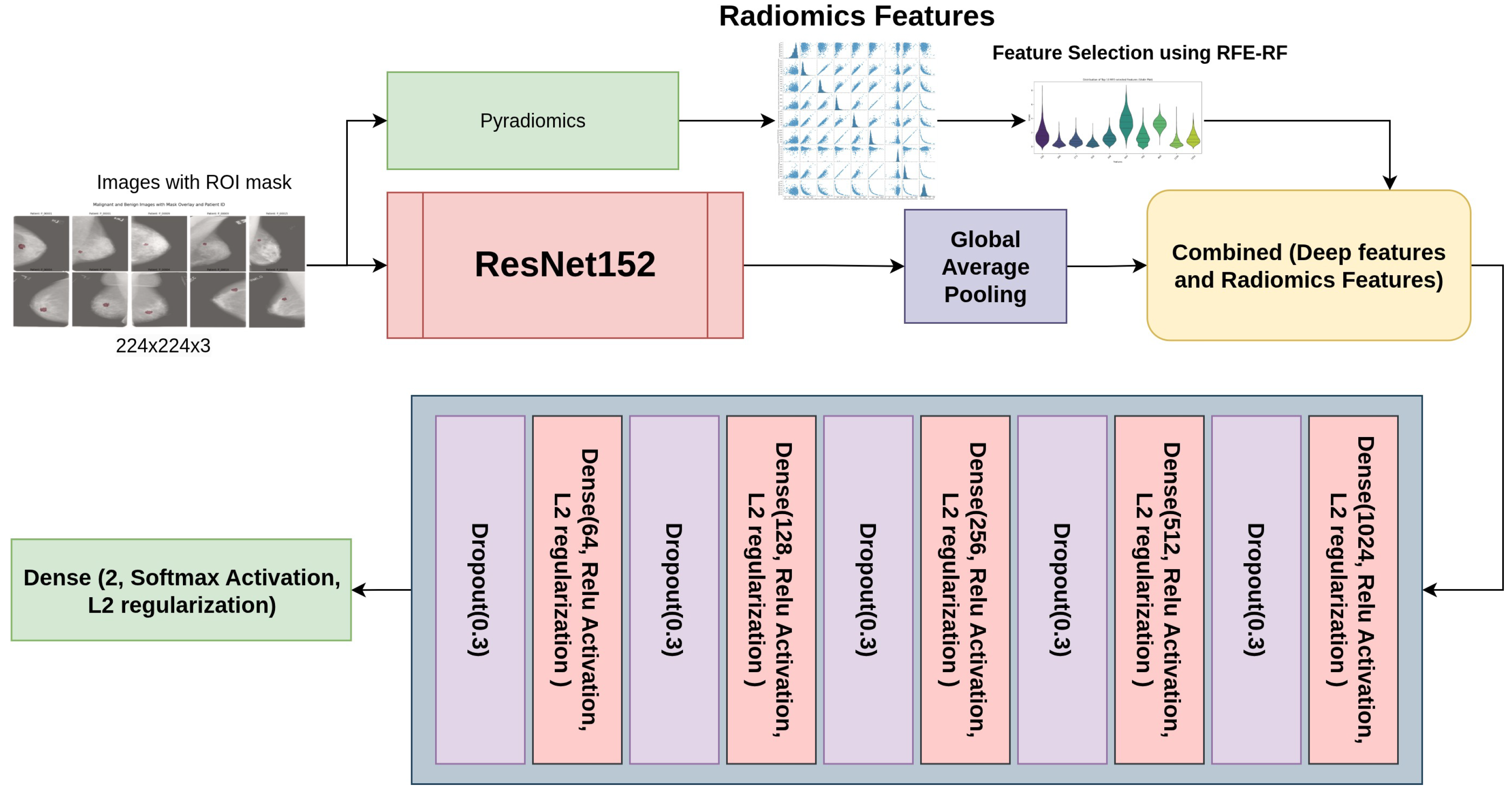

Figure 3 outlines the structure of the ResNet152 model combined with custom layers. The base model, ResNet152, is a deep convolutional neural network that begins with an initial convolutional layer using a 7x7 kernel, 64 filters, and a stride of 2, followed by max-pooling and several residual blocks. The residual blocks are structured with multiple convolutional layers featuring progressively increasing filter sizes of 128, 256, 512, and 1024. This architecture enhances the network’s capability to capture features at both low and high levels accurately, thus alleviating the vanishing gradient issue and strengthening the model’s capacity to recognize intricate patterns. After the residual blocks, Global Average Pooling effectively compresses the feature maps into a 1D vector. To further enhance the model, custom layers integrate radiomics features into the network. The deep features from ResNet152 and the radiomics features are concatenated, followed by several fully connected layers with ReLU activation, L2 regularization, and Dropout for regularization and to prevent overfitting. For binary classification in the final output layer, we utilized a Softmax activation function, such as distinguishing between benign and malignant conditions. This combined architecture effectively integrates deep learning features and radiomics information, improving the model’s overall classification performance.

3.6. Model Evaluation

We established an internal validation procedure with an 80%, 10%, and 10% division for training, validation, and testing. This method assured that class distributions were maintained throughout all subsets. We evaluated the model’s effectiveness using metrics including accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score.

3.7. Experiment Setup

Every model was set up with weights that were pre-trained on ImageNet, and the dimensions of the input image were specified as (224, 224, 3).To fine-tune the models, the top 30% of layers were unfrozen while keeping the remaining layers frozen. Regularization techniques included L2 weight decay with and dropout layers with a 30% probability of reducing overfitting. The categorical cross-entropy loss function was used, with the Adam optimizer configured at a learning rate of .Early stopping with a patience value of 5 epochs was implemented, and the best model for each architecture was saved in .h5 formats. The models’ performance was analyzed using accuracy/loss curves, confusion matrices, and classification reports to assess their effectiveness in classification tasks.

4. Results

4.1. Radiomics Analysis

In our radiomics analysis model, we extracted seven types of radiomic features using pyradiomics

Table 3 describe the radiomics features by categories. A total of 1,040 radiomic features were extracted from the imaging dataset. Among these, first-order statistical features accounted for 198 features, capturing voxel intensity distributions within the region of interest. Texture features were highly represented, including 264 features from the gray-level co-occurrence matrix (GLCM), 176 from the gray-level run length matrix (GLRLM), 176 from the gray-level size zone matrix (GLSZM), 154 from the gray-level dependence matrix (GLDM), and 55 from the neighborhood gray-tone difference matrix (NGTDM). Additionally, nine shape-based features were included to characterize lesion geometry, along with five diagnostic metadata features.

Radiomics Feature selection

Our study evaluates feature selection methods across five categories (RFE, SelectKBest, LASSO, Tree-based, and Information-based) with different number of features.

Table 4 describe the comprehensive comparison of radiomics feature selection methods. In our study, we are using metrics such as Accuracy, F1 score, Precision, Recall and stability. Our analysis reveals that Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) with Random Forest (n=100) achieves the highest Accuracy(83.7%), F1 score (83%), Precision (86.2%), Recall (80.0%) and moderate stability (0.485). SelectKBest (ANOVA, n=20) offers the highest stability (0.897). No significant performance differences were found across method categories (ANOVA p=0.699). Methods achieving high performance (F1

) with fewer features (

) suggest significant feature redundancy in radiomics data.

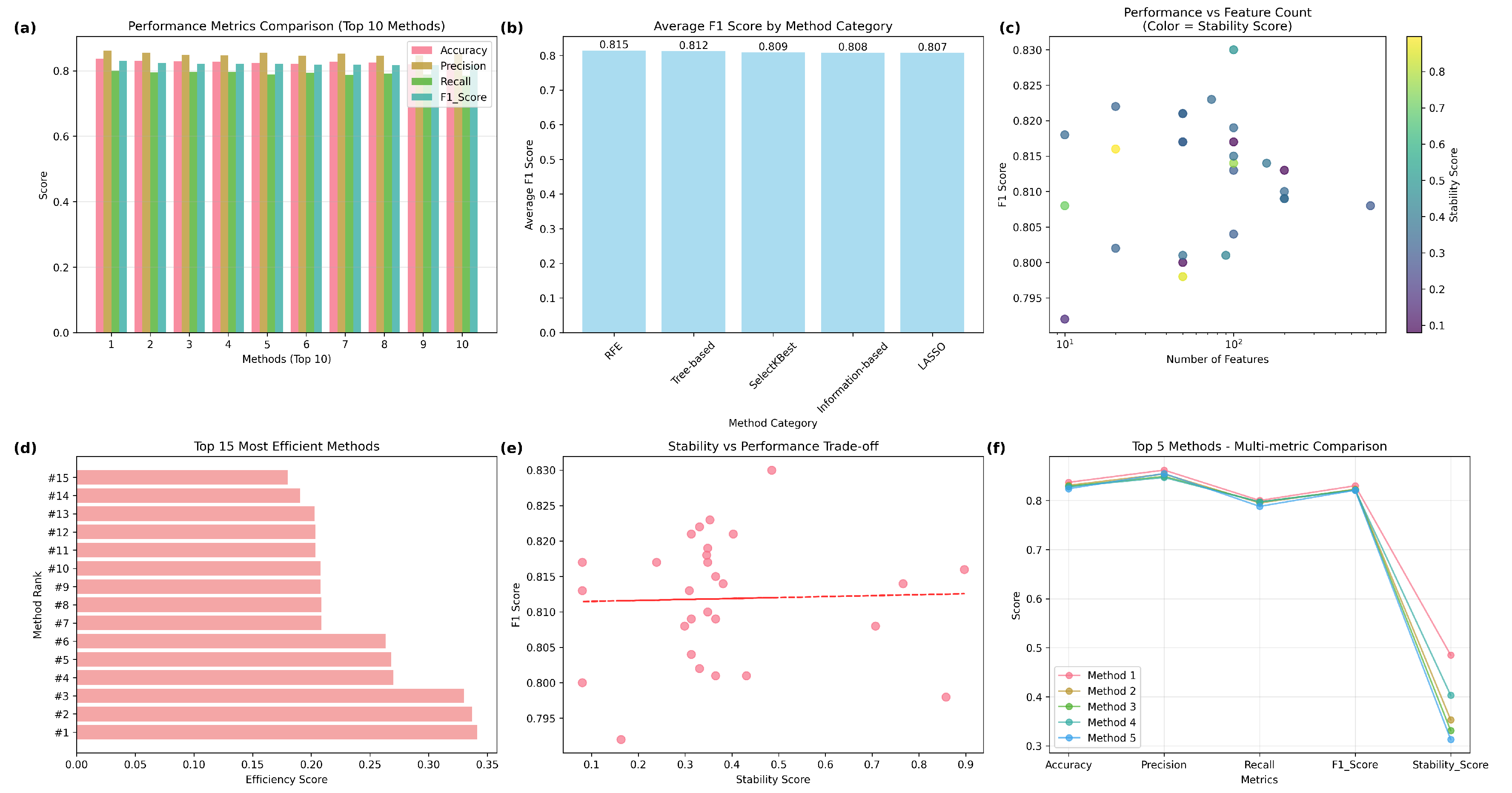

Figure 4 summarize the comparative analysis.

Figure 4(a) comparing accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score across the top 10 performing methods. The best overall feature selection method was RFE with Random Forest using 100 features, achieving an F1-score of 0.830 and a stability score of 0.485, striking a balance between predictive performance and feature stability. In contrast, the SelectKBest method with ANOVA (n=20) attained the highest stability (0.897) with a competitive F1-score (0.816), highlighting its suitability for reproducible feature selection in clinical applications.

Figure 4(b) shows average F1-score by method category, showing RFE with the highest mean F1-score (0.815), followed closely by tree-based, SelectKBest, information-based, and LASSO methods, suggesting minimal differences in overall category-level performance.From scatterplot,

Figure 4(c) depicting the relationship between the number of selected features (log scale) and F1-score, with marker color indicating stability scores. This reveals that high F1-scores can be obtained with a broad range of feature counts, while stability is more variable, highlighting the trade-offs among model complexity, performance, and robustness. Horizontal bar chart

Figure 4(d) ranking the top 15 most efficient methods based on efficiency score (F1-score per feature count). This emphasizes the advantage of RFE and SelectKBest methods for achieving competitive performance with relatively few features. A scatterplot

Figure 4(e) illustrating the F1-score in relation to the stability score, along by a trend line that reveals a near-zero correlation (Pearson r = 0.03), suggests that stability and performance are predominantly independent, warranting the reporting of both in radiomics pipelines.

Figure 4(f) shows the Line plot comparing the top five methods across multiple metrics, demonstrating consistently high accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score, but more variation in stability scores, highlighting differences in robustness among the top-performing methods.

The RFE-RF approach utilising 100 features attained the highest overall F1-score of 0.830 among all assessed methods, signifying exceptional classification performance. This approach utilises the advantages of Random Forest, an ensemble technique known for its ability to capture intricate nonlinear correlations in radiomics data, while systematically removing less useful elements. By selecting 100 features, it attains an effective balance between model complexity and overfitting mitigation, preserving generalizability on novel data. Furthermore, its moderate stability score (0.485) indicates that the chosen features exhibited reasonable consistency across cross-validation folds, instilling trust in their reproducibility while maintaining a focus on high prediction accuracy. In comparison to techniques exhibiting greater stability yet inferior F1-scores, RFE-RF (n=100) provides an ideal balance between efficacy and resilience.

4.2. Models Performance

Table 5 provides a comprehensive comparison of 13 transfer learning models, including DenseNet, InceptionV3, MobileNet, ResNet, and VGG, with a focus on key performance metrics: Precision (Pre), Recall (Rec), F1-score (F1s), Accuracy (Ac), and the number of epochs (Ep) used for training. ResNet152 is the highest-performing model, achieving the best values across all metrics: a precision of 0.97, recall of 0.98, F1-score of 0.97, and accuracy of 0.97. This makes ResNet152 particularly suitable for tasks that require a strong balance between minimizing false positives and accurately detecting true positives. VGG19 follows closely behind, with a precision, recall, F1-score, and accuracy of 0.96, confirming its high reliability in both precision and recall. Other models, such as DenseNet121, DenseNet169, and DenseNet201, exhibit solid performance but fall slightly short compared to ResNet152 and VGG19. These models show precision and recall values ranging from 0.93 to 0.95, F1-scores of approximately 0.94, and accuracy between 0.93 and 0.94, making them practical for general use but less optimal than the top performers. InceptionV3 and MobileNet are relatively weaker performers in precision and recall, with InceptionV3 achieving an accuracy of 0.89 and MobileNet reaching 0.88. These results suggest that these models are less reliable at correctly identifying positive instances. While InceptionV3 performs better than MobileNet, both models still lag behind the other architectures in precision and recall metrics. The ResNet50 and ResNet50V2 models exhibit consistent performance, with precision and recall values of approximately 0.94, F1-scores of 0.94, and accuracy of 0.94, positioning them as solid but not top-tier options. Models from the ResNet101 family, specifically ResNet101 and ResNet101V2, perform at a high level, with precision, recall, and F1-scores of 0.96, along with an accuracy of 0.96, indicating their robustness for tasks requiring strong model performance across all metrics. Notably, the ResNet152 model requires fewer epochs (40 epochs) than other models, such as ResNet101 and ResNet50, which were trained for 50 epochs, highlighting its more efficient convergence. These results demonstrate that while ResNet152 and VGG19 dominate overall performance, models like DenseNet and ResNet101 provide strong alternatives. Some offer faster convergence with minimal sacrifice in accuracy.

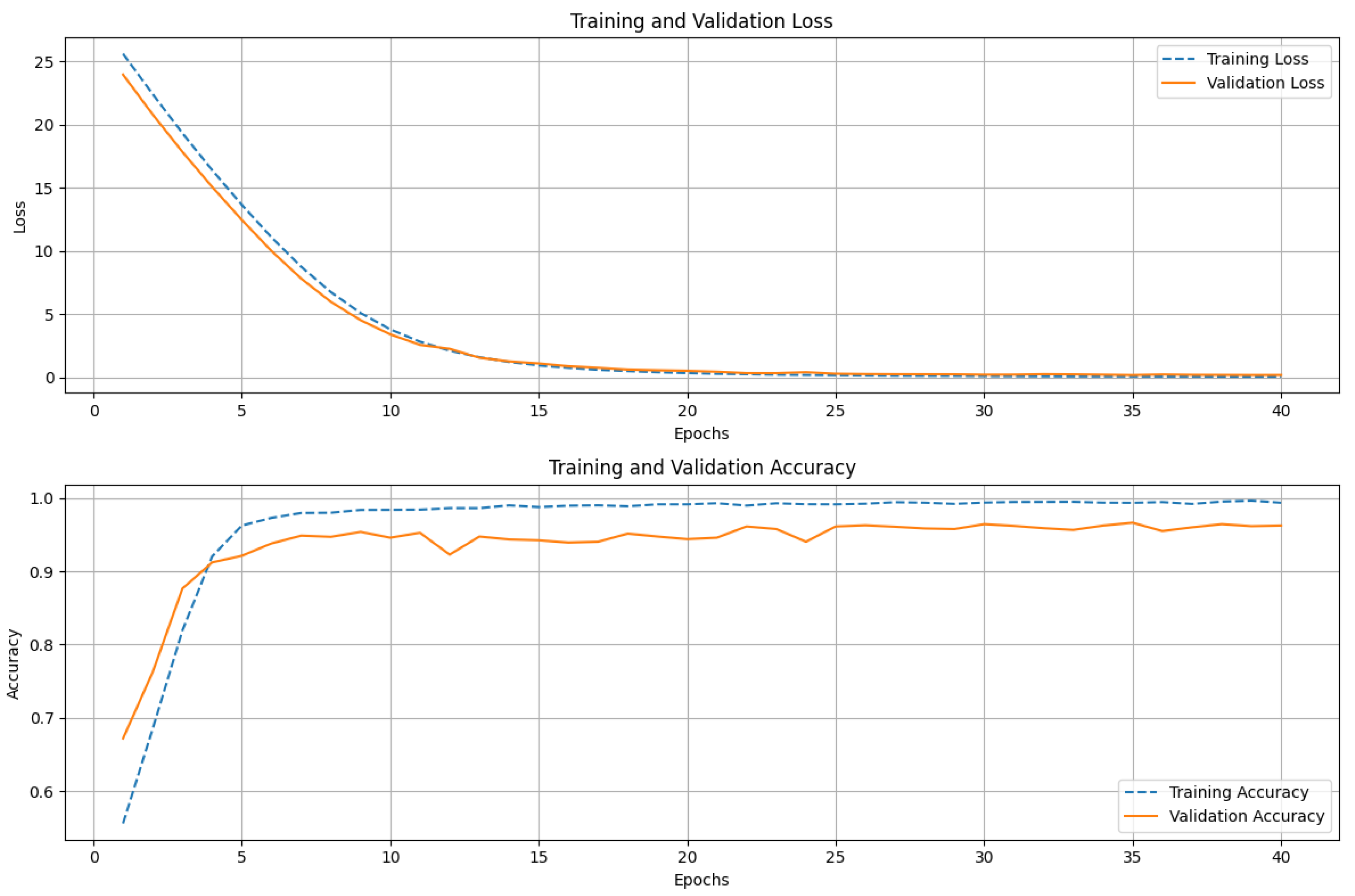

Figure 5 shows the training and validation performance of the ResNet152 model over 40 epochs. The upper graph displays both the training and validation loss. The training loss decreases sharply in the initial epochs, indicating that the model is quickly learning to minimize errors. The loss gradually converges as training progresses, reflecting stability in the learning process. The validation loss follows a similar trend, steadily decreasing before leveling off, suggesting that the model generalizes well to unseen data. The lower graph illustrates the accuracy of training and validation. During the early epochs, we see a rapid increase in training accuracy, approaching near-perfect classification. The validation accuracy also trends upward but displays minor fluctuations, which is typical due to variations in the validation dataset. The consistent gap between training and validation accuracy remains small, indicating that the model does not suffer from significant overfitting. The ResNet152 model achieves high accuracy with stable convergence, demonstrating its strong learning capacity and generalization performance.

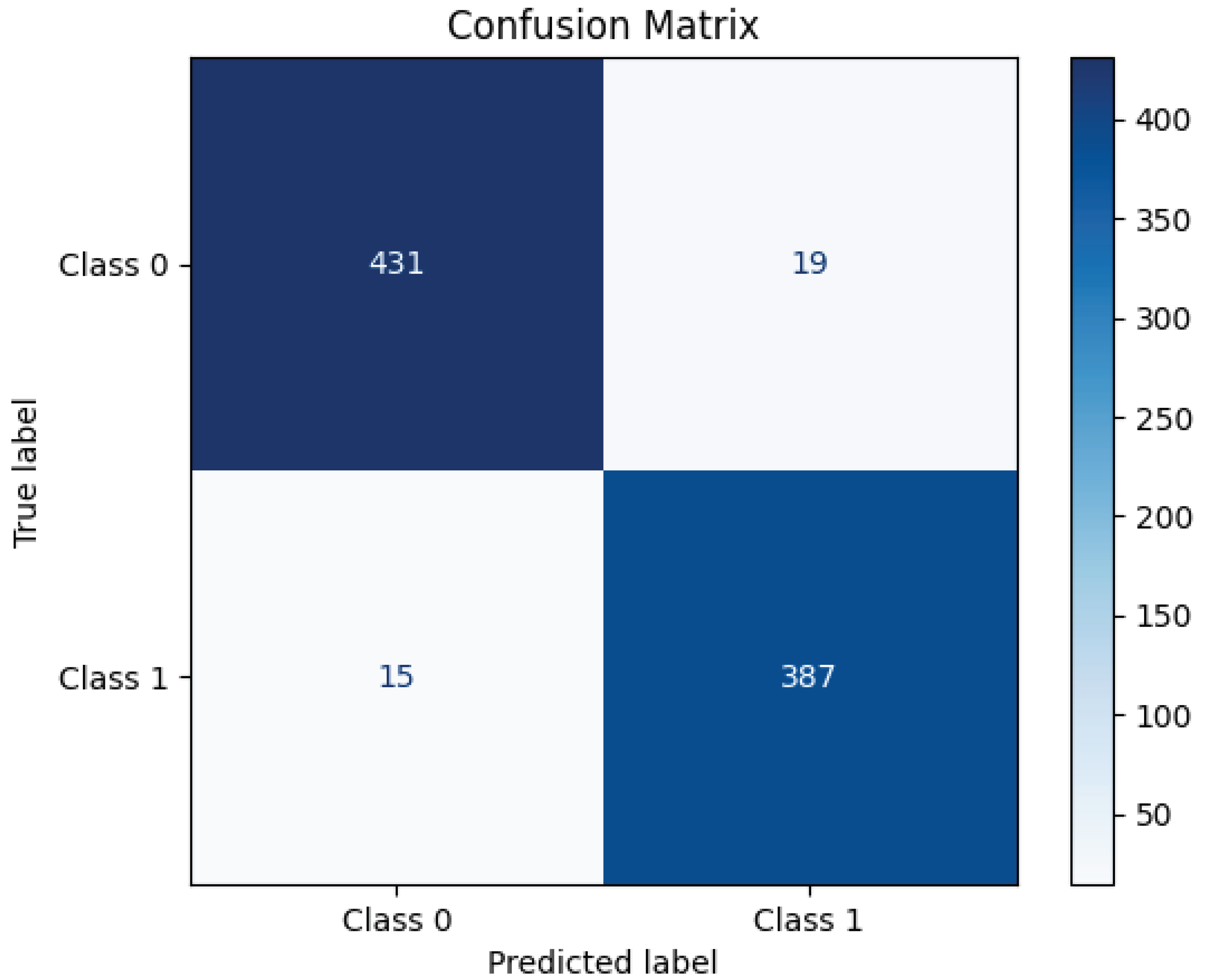

Figure 6 presents the confusion matrix for the ResNet152 model, illustrating its classification performance. The model correctly classified 431 instances of Class 0 (TN) and 387 instances of Class 1 (TP), demonstrating high accuracy. However, 19 samples of Class 0 were misclassified as Class 1 (FP), and 15 samples of Class 1 were incorrectly predicted as Class 0 (FN). These misclassifications indicate a small prediction error, though the model maintains strong classification performance overall. The high concentration of values along the diagonal of the matrix suggests that ResNet152 effectively distinguishes between the two classes, achieving a robust balance between precision and recall.

5. Discussion

In our study, after comprehensive data augmentation and feature engineering, we implemented 13 transfer learning models for breast cancer early detection, where ResNet152 achieved an impressive accuracy of 97%. We also observed strong results with other models in the ResNet family: ResNet50 reached 94%, ResNet50V2 achieved 93%, ResNet101 and ResNet101V2 both attained 96%, and ResNet152V2 achieved 94%. In our evaluation using this methodology we also achieve 96% accuracy using VGG19. We compare our results with those of recent studies published between 2023 and 2025. All of these studies utilized radiomics features and transfer learning models for evaluation.

Table 6 presents a comparison of our research performance with these recent studies. Our study demonstrates superior performance across multiple deep-learning architectures compared to the majority of the referenced studies. Notably, our implementation of ResNet-152 achieves the highest accuracy of 97%, surpassing all other models in the comparison. This is followed closely by our ResNet101 and ResNet101V2 models, both of which achieve 96% accuracy, as well as our VGG19 model, which also achieves 96%. These results indicate a significant improvement over earlier studies, such as Yu et al. [

23], where the best-performing model (ResNet50) achieved 82% accuracy, and Wei et al [

25], where VGG19 reached 83%. Among the compared studies, Sharmin et al. [

26] reported a competitive accuracy of 95% using ResNet50V2, which is closely matched by our ResNet50V2 (93%) and exceeded by our deeper architectures (ResNet101, ResNet101V2, and ResNet152). The performance of our ResNet50 (94%) also significantly outperforms the ResNet50 implementations by Yu et al. [

23] (82%) and Wei et al [

25] (72%), highlighting the effectiveness of our transfer learning and optimization strategies. For VGG-based models, our VGG16 and VGG19 implementations achieve 94% and 96% accuracy, respectively, compared to 71% (VGG16, Yu et al. [

23]) and 83% (VGG19, Wei et al. [

25]). This substantial improvement underscores the robustness of our preprocessing and training methodologies. Similarly, our Inception_v3 model (89%) outperforms the Inception_v3 implementation by Wei et al. [

25] (72%), although it is the least competitive among our models. Compared to Gao et al. [

24] and Yang et al. [

27], whose ResNet and 3DResNet models achieved 82% and 74% accuracy, respectively, our models consistently demonstrate higher performance across all tested architectures. The superior performance of our study can be attributed to advanced data augmentation, feature engineering and optimized hyperparameter tuning. This suggests that our methodology, which optimally prepares and augments the dataset, enhances the performance of not only ResNet152 but also other transfer learning models in the breast cancer detection task. The consistent performance improvement across multiple models indicates the versatility and effectiveness of our approach in boosting the diagnostic precision of various deep learning architectures. Therefore, our methodology delivers outstanding results with ResNet152 and enhances the capabilities of other models, reinforcing its utility in medical image analysis.

6. Conclusion

In this study, we proposed an integrated methodology for the early detection of breast cancer by combining data augmentation, multimodal feature selection, and the evaluation of deep learning models. Our results demonstrate the effectiveness of ResNet152, which achieved an accuracy of 97%. The robustness of our methodology was further validated by consistent performance improvements across various transfer learning models, including ResNet101, ResNet50, and VGG19, all of which achieved high accuracies. This highlights the versatility and strength of our approach to enhancing breast cancer detection across different deep-learning architectures. Our methodology effectively combines radiomics with deep learning, providing a solid foundation for future research in medical image analysis and demonstrating the potential for improving early detection systems. While the results of this study are promising, there are several avenues for further research and improvement. A potential avenue for future research includes the use of Vision Transformers (ViTs), which have shown considerable success in computer vision tasks by employing self-attention mechanisms to identify long-range dependencies in images. Unlike traditional CNN-based models, ViTs treat image patches as sequences and can learn spatial hierarchies more effectively. By incorporating ViTs into our framework, we can explore their ability to enhance feature extraction, particularly in complex medical images like those used in breast cancer detection.

References

- Arnold, M.; Morgan, E.; Rumgay, H.; Mafra, A.; Singh, D.; Laversanne, M.; Vignat, J.; Gralow, J.R.; Cardoso, F.; Siesling, S.; et al. Current and future burden of breast cancer: Global statistics for 2020 and 2040. Breast (Edinburgh, Scotland) 2022, 66, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhagat, J.; Lobo, R.; Kumar, N.; Mathew, J.E.; Pai, A. Cytotoxic potential of Anisochilus carnosus (L.f.) wall and estimation of luteolin content by HPLC 2014.

- Balkenende, L.; Teuwen, J.; Mann, R.M. Application of Deep Learning in Breast Cancer Imaging. Seminars in Nuclear Medicine 2022, 52, 584–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maruf, N.A.; Basuhail, A. Breast cancer diagnosis using radiomics-guided DL/ML model-systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in Computer Science 2025, 7, 1446270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, D.; He, X.; Jing, J. Overview of Artificial Intelligence in Breast Cancer Medical Imaging. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karthiga, R.; Narasimhan, K. Medical imaging technique using curvelet transform and machine learning for the automated diagnosis of breast cancer from thermal image. Pattern Analysis and Applications 2021, 24, 981–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kora, P.; Ooi, C.P.; Faust, O.; Raghavendra, U.; Gudigar, A.; Chan, W.Y.; Meenakshi, K.; Swaraja, K.; Plawiak, P.; Rajendra Acharya, U. Transfer learning techniques for medical image analysis: A review. Biocybernetics and Biomedical Engineering 2022, 42, 79–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oladimeji, O.O.; Ayaz, H.; McLoughlin, I.; Unnikrishnan, S. Mutual information-based radiomic feature selection with SHAP explainability for breast cancer diagnosis. Results in Engineering 2024, 24, 103071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamal, A.; Sharafeldeen, A.; Alnaghy, E.; Alghandour, R.; Saleh Alghamdi, N.; Ali, K.M.; Shamaa, S.; Aboueleneen, A.; Elsaid Tolba, A.; Elmougy, S.; et al. A Novel Machine Learning Approach for Predicting Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy Response in Breast Cancer: Integration of Multimodal Radiomics With Clinical and Molecular Subtype Markers. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 104983–105003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Zeng, Y.; Zuo, Z.; Yang, X.; Liu, H.; Zhou, Y.; Fan, X. Leveraging multimodal MRI-based radiomics analysis with diverse machine learning models to evaluate lymphovascular invasion in clinically node-negative breast cancer. Heliyon 2024, 10, e23916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Del Corso, G.; Germanese, D.; Caudai, C.; Anastasi, G.; Belli, P.; Formica, A.; Nicolucci, A.; Palma, S.; Pascali, M.A.; Pieroni, S.; et al. Adaptive Machine Learning Approach for Importance Evaluation of Multimodal Breast Cancer Radiomic Features. Journal of Imaging Informatics in Medicine 2024, 37, 1642–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibrahim, A.; Primakov, S.; Beuque, M.; Woodruff, H.C.; Halilaj, I.; Wu, G.; Refaee, T.; Granzier, R.; Widaatalla, Y.; Hustinx, R.; et al. Radiomics for precision medicine: Current challenges, future prospects, and the proposal of a new framework. Methods 2021, 188, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haghshomar, M.; Rodrigues, D.; Kalyan, A.; Velichko, Y.; Borhani, A. Leveraging radiomics and AI for precision diagnosis and prognostication of liver malignancies. Frontiers in Oncology 2024, Volume 14 - 2024. [CrossRef]

- Khourdifi, Y.; Alami, A.E.; Zaydi, M.; Maleh, Y. Early Breast Cancer Detection Based on Deep Learning: An Ensemble Approach Applied to Mammograms. MDPI 2024.

- Luong, H.H.; Vo, M.D.; Phan, H.P.; Dinh, T.A. Improving Breast Cancer Prediction via Progressive Ensemble and Image Enhancement. Multimedia Tools and Applications 2024.

- Chugh, G.; Kumar, S.; Singh, N. TransNet: A Comparative Study on Breast Carcinoma Diagnosis with Classical Machine Learning and Transfer Learning Paradigm. Multimedia Tools and Applications 2024.

- Subha, T.D.; Charan, G.S.; Reddy, C.C. An Efficient Image-Based Mammogram Classification Framework Using Depth-Wise Convolutional Neural Network. IEEE Conference on Artificial Intelligence 2023.

- Gujar, S.A.; Lei, X.; Cen, S.Y.; Hwang, D.H. Breast Lesion Classification using Radiomics-derived Regions of Interest on Mammograms. IEEE Symposium on Image Processing 2023.

- Alkhaleefah, M.; Tan, T.H.; Chang, C.H.; Wang, T.C.; Ma, S.C. Connected-segNets: A Deep Learning Model for Breast Tumor Segmentation from X-ray Images. Cancers 2022.

- Lee, R.S.; Gimenez, F.; Hoogi, A.; Miyake, K.K.; Gorovoy, M.; Rubin, D.L. A curated mammography data set for use in computer-aided detection and diagnosis research. Scientific Data 2017 4:1 2017, 4, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marufaiub. CBIS-DDSM-Radiomics-And-13-Transfer-Learning-Models, 2024. Accessed: 2025-02-02.

- Van Griethuysen, J.J.; Fedorov, A.; Parmar, C.; Hosny, A.; Aucoin, N.; Narayan, V.; Beets-Tan, R.G.; Fillion-Robin, J.C.; Pieper, S.; Aerts, H.J. Computational radiomics system to decode the radiographic phenotype. Cancer Research 2017, 77, e104–e107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, F.H.; Miao, S.M.; Li, C.Y.; Hang, J.; Deng, J.; Ye, X.H.; Liu, Y. Pretreatment ultrasound-based deep learning radiomics model for the early prediction of pathologic response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer. European Radiology 2023, 33, 5634–5644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, J.; Zhong, X.; Li, W.; Li, Q.; Shao, H.; Wang, Z.; Dai, Y.; Ma, H.; Shi, Y.; Zhang, H.; et al. Attention-based Deep Learning for the Preoperative Differentiation of Axillary Lymph Node Metastasis in Breast Cancer on DCE-MRI. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging 2023, 57, 1842–1853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, W.; Ma, Q.; Feng, H.; Wei, T.; Jiang, F.; Fan, L.; Zhang, W.; Xu, J.; Zhang, X. Deep learning radiomics for prediction of axillary lymph node metastasis in patients with clinical stage T1–2 breast cancer. Quantitative Imaging in Medicine and Surgery 2023, 13, 4995–5011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharmin, S.; Ahammad, T.; Talukder, M.A.; Ghose, P. A Hybrid Dependable Deep Feature Extraction and Ensemble-Based Machine Learning Approach for Breast Cancer Detection. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 87694–87708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Fan, X.; Lin, S.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, H.; Wang, X.; Zuo, Z.; Zeng, Y. Assessment of Lymphovascular Invasion in Breast Cancer Using a Combined <scp>MRI</scp> Morphological Features, Radiomics, and Deep Learning Approach Based on Dynamic Contrast-Enhanced <scp>MRI</scp>. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).