Submitted:

03 January 2026

Posted:

04 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Connection Mechanisms in Social Media Use

2.2. Psychological Mechanisms Linking Social Comparison and Problematic Use

2.3. The Dual Intensification of Connection and Anxiety During COVID-19

2.4. Research Gaps

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Data Sources and Corpus Construction

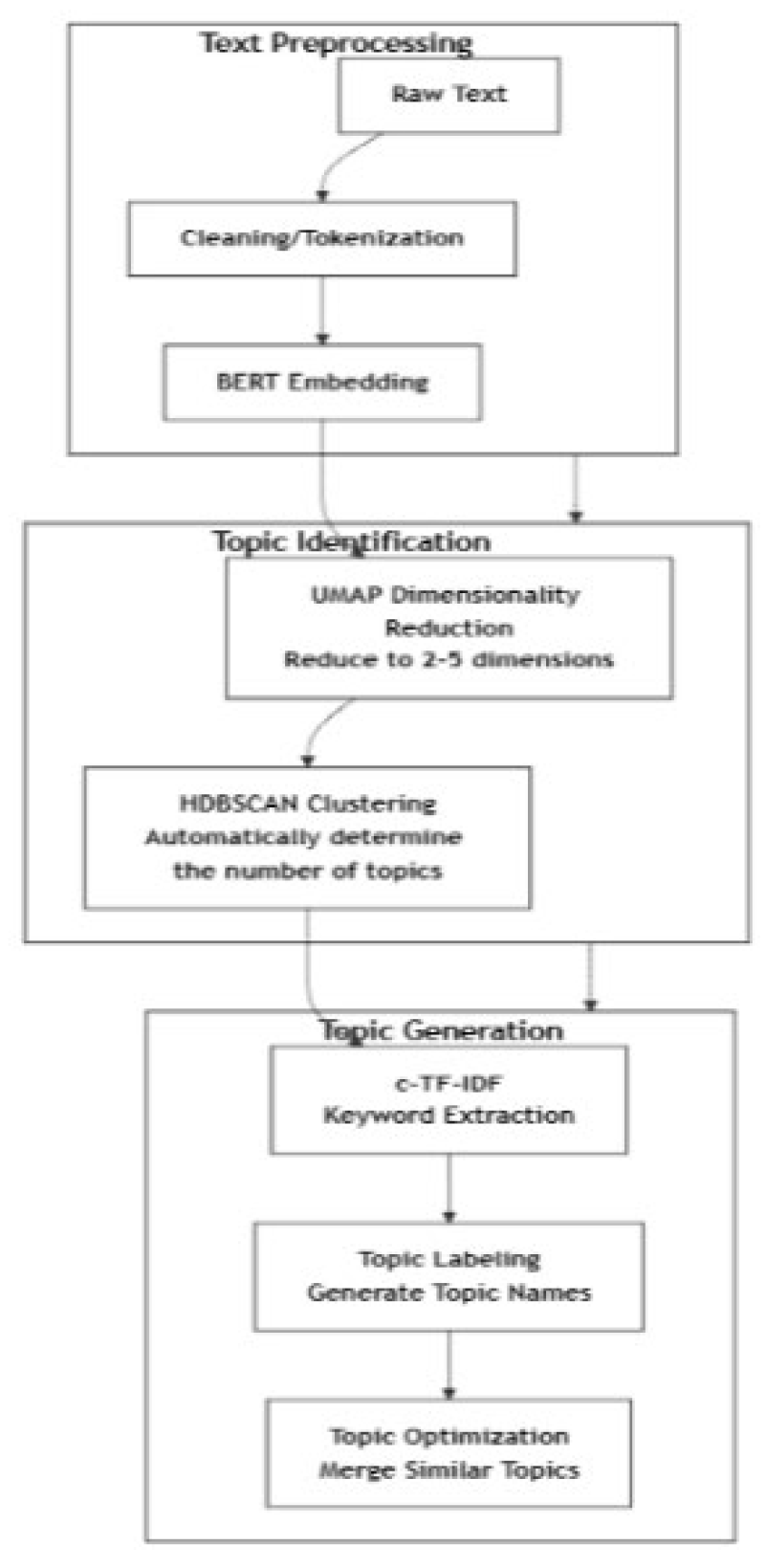

3.2. BERTopic Dynamic Topic Modelling

3.3. Dynamic Topic Trend Analysis

4. Result

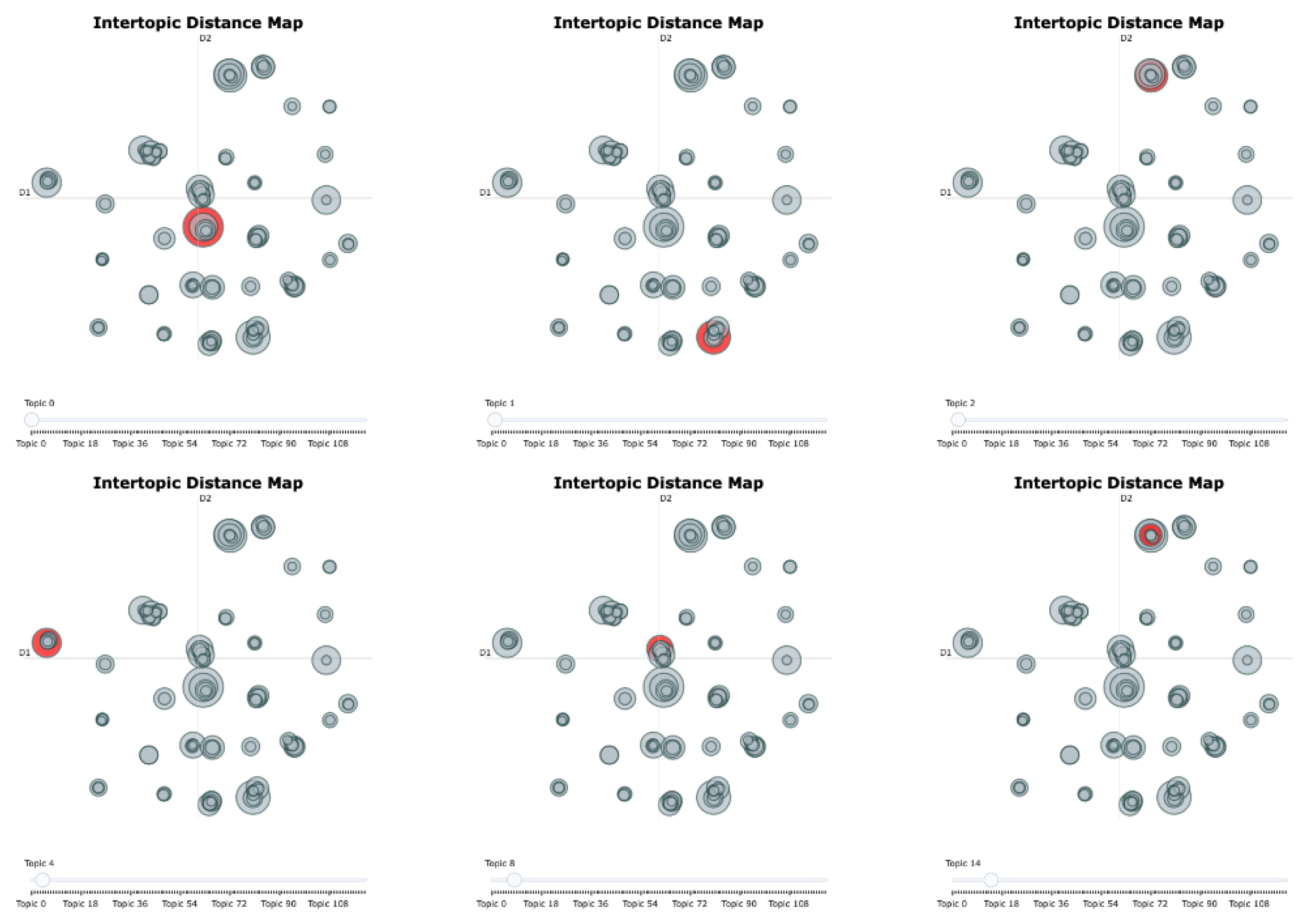

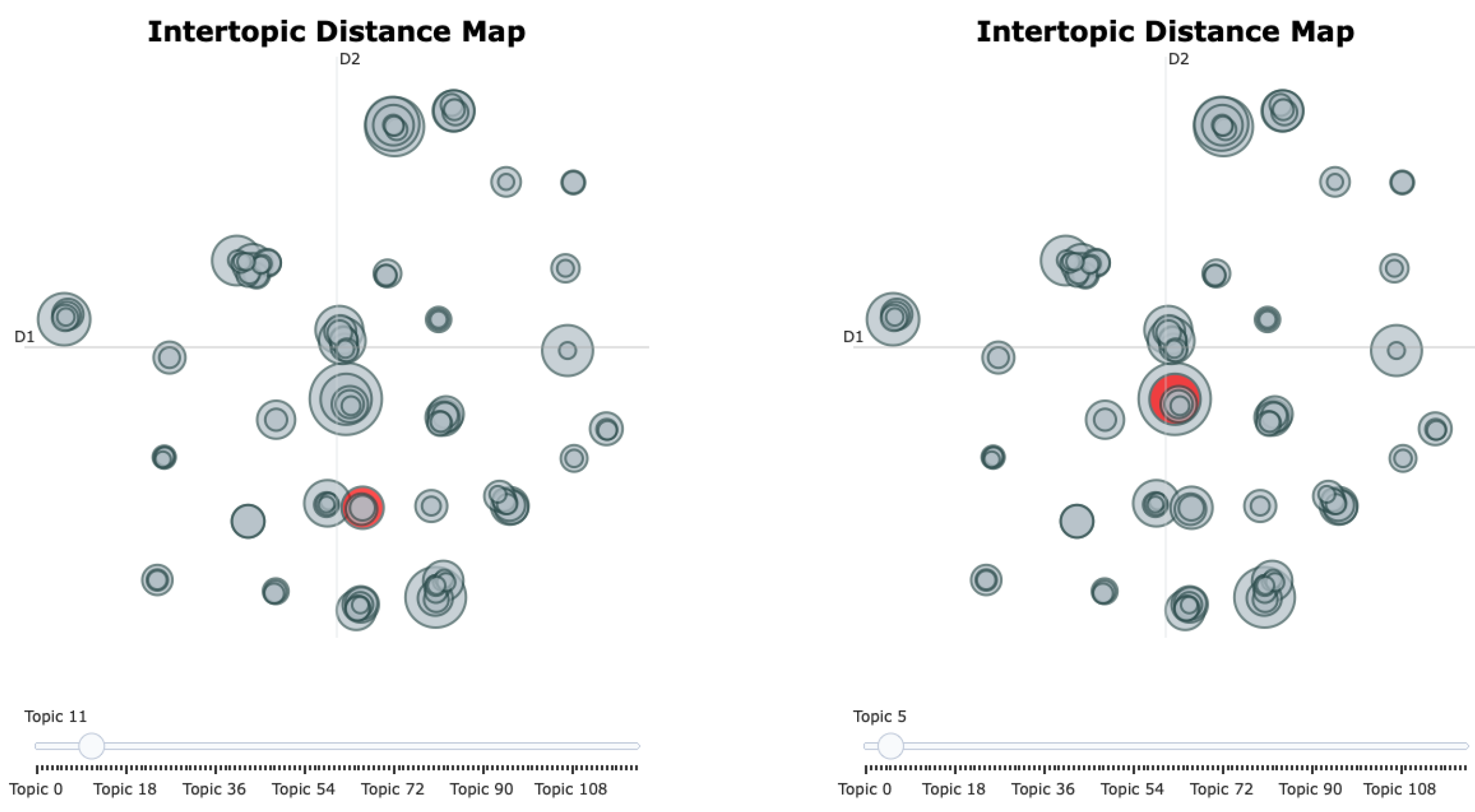

4.1. The Coexistence of Connection- and Anxiety-Oriented Research Landscapes

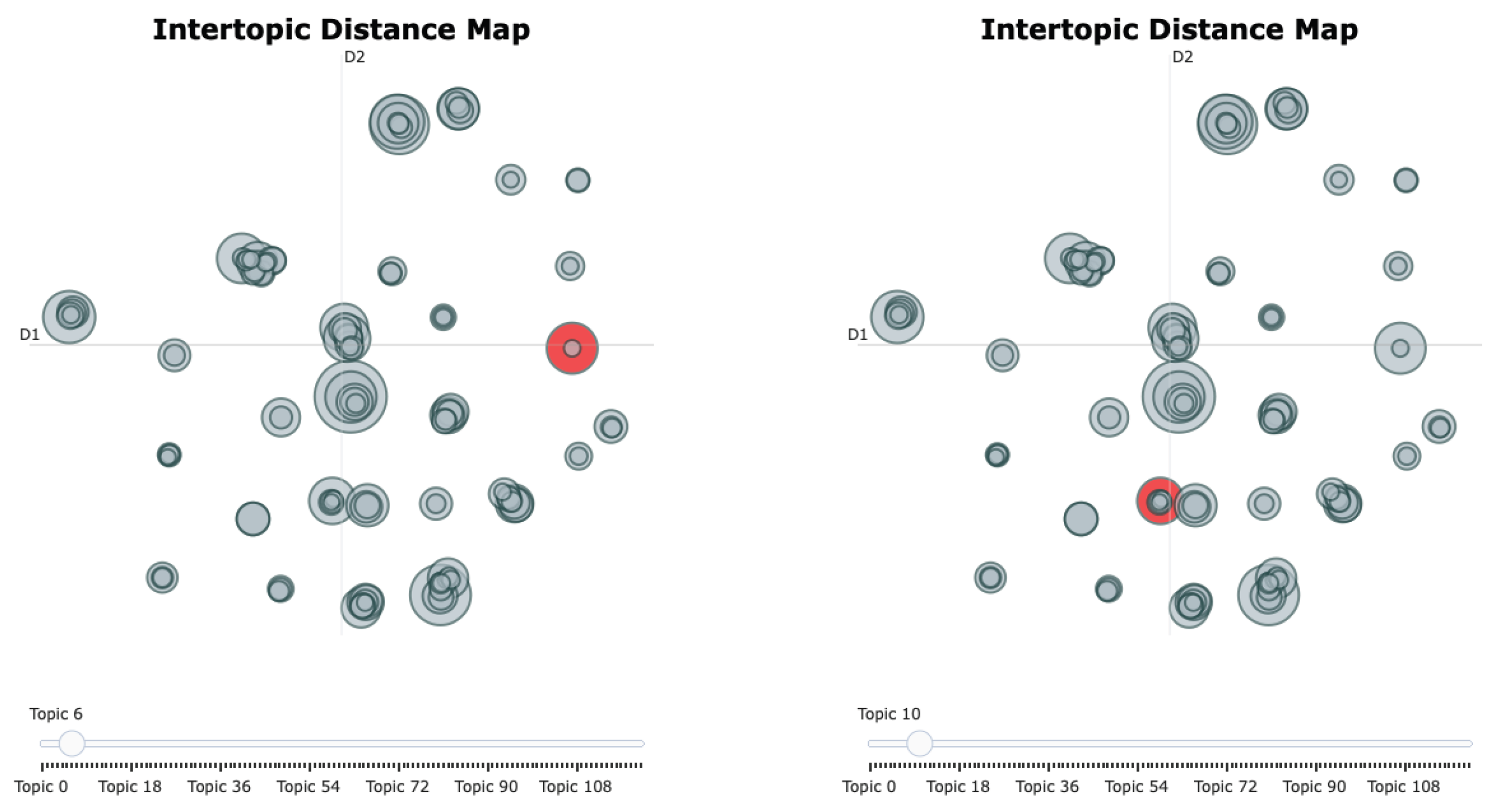

4.2. Semantic Relationships Among Topics

4.3. Dynamic Evolution of Knowledge Focus

5. Conclusion and Future Directions

5.1. Main Finding

5.2. Implications

5.3. Future Research Directions

References

- Abbas, J., D. Wang, Z. Su, and A. Ziapour. 2021. The role of social media in the advent of COVID-19 pandemic: Crisis management, mental health challenges and implications. Risk Management and Healthcare Policy 14: 1917–1932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Appel, H., A. L. Gerlach, and J. Crusius. 2016. The interplay between Facebook use, social comparison, envy, and depression. Current Opinion in Psychology 9: 44–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumeister, R. F., and M. R. Leary. 1995. The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin 117, 3: 497–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beyens, I., E. Frison, and S. Eggermont. 2016. “I don’t want to miss a thing”: Adolescents’ fear of missing out and its relationship to adolescents’ social needs, Facebook use, and Facebook related stress. Computers in Human Behavior 64: 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackwell, D., C. Leaman, R. Tramposch, C. Osborne, and M. Liss. 2017. Extraversion, neuroticism, attachment style and fear of missing out as predictors of social media use and addiction. Personality and Individual Differences 116: 69–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braghieri, L., R. Levy, and A. Makarin. 2022. Social media and mental health. American Economic Review 112, 11: 3660–3693. Available online: https://www.google.com/search?q=https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20211218. [CrossRef]

- Burke, M., and R. E. Kraut. 2016. The relationship between Facebook use and well-being depends on communication type and tie strength. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 21, 4: 265–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Hesselle, L. C., and C. Montag. 2024. Effects of a 14-day social media abstinence on mental health and well-being: Results from an experimental study. BMC Psychology 12, 1: 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhir, A., Y. Yossatorn, P. Kaur, and S. Chen. 2018. Online social media fatigue and psychological wellbeing-A study of compulsive use, fear of missing out, fatigue, anxiety and depression. International Journal of Information Management 40: 141–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellison, N. B., C. Steinfield, and C. Lampe. 2007. The benefits of Facebook “friends:“ Social capital and college students’ use of online social network sites. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 12, 4: 1143–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Festinger, L. 1954. A theory of social comparison processes. Human Relations 7, 2: 117–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J., P. Zheng, Y. Jia, H. Chen, Y. Mao, S. Chen, Y. Wang, H. Fu, and J. Dai. 2020. Mental health problems and social media exposure during COVID-19 outbreak. PLoS ONE 15, 4: e0231924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geirdal, A. Ø., M. Ruffolo, J. Leung, H. Thygesen, D. Price, T. Bonsaksen, and M. Schoultz. 2021. Mental health, quality of life, wellbeing, loneliness and use of social media in a time of social distancing during the COVID-19 outbreak. A cross-country comparative study. Journal of Mental Health 30, 2: 148–155. Available online: https://www.google.com/search?q=https://doi.org/10.1080/09638237.2021.1875413. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gori, A., E. Topino, and M. D. Griffiths. 2023. The associations between attachment, self-esteem, fear of missing out, daily time expenditure, and problematic social media use: A path analysis model. Addictive Behaviors 141: 107633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grootendorst, M. 2022. BERTopic: Neural topic modeling with a class-based TF-IDF procedure. arXiv arXiv:2203.05794. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, C. 2020. A meta-analysis of the problematic social media use and mental health. International Journal of Social Psychiatry 68, 1: 12–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunt, M. G., R. Marx, C. Lipson, and J. Young. 2018. No more FOMO: Limiting social media decreases loneliness and depression. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology 37, 10: 751–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keles, B., N. McCrae, and A. Grealish. 2020. A systematic review: The influence of social media on depression, anxiety and psychological distress in adolescents. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth 25, 1: 79–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kross, E., P. Verduyn, E. Demiralp, J. Park, D. S. Lee, N. Lin, H. Shablack, J. Jonides, and O. Ybarra. 2013. Facebook use predicts declines in subjective well-being in young adults. PLoS ONE 8, 8: e69841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, L. Y., J. E. Sidani, A. Shensa, A. Radovic, E. Miller, J. B. Colditz, B. L. Hoffman, L. M. Giles, and B. A. Primack. 2016. Association between social media use and depression among U.S. young adults. Depression and Anxiety 33, 4: 323–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naslund, J. A., K. A. Aschbrenner, L. A. Marsch, and S. J. Bartels. 2016. The future of mental health care: Peer-to-peer support and social media. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences 25, 2: 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, M. Y., L. Yang, C. M. C. Leung, N. Li, X. I. Yao, Y. Wang, G. M. Leung, B. J. Cowling, and Q. Liao. 2020. Mental health, risk factors, and social media use during the COVID-19 epidemic and Cordon Sanitaire among the community and health professionals in Wuhan, China: Cross-sectional survey. JMIR Mental Health 7, 5: e19009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pittman, M., and B. Reich. 2016. Social media and loneliness: Why an Instagram picture may be worth more than a thousand Twitter words. Computers in Human Behavior 62: 155–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Primack, B. A., A. Shensa, C. G. Escobar-Viera, E. L. Barrett, J. E. Sidani, J. B. Colditz, and A. E. James. 2017. Use of multiple social media platforms and symptoms of depression and anxiety: A nationally-representative study among U.S. young adults. Computers in Human Behavior 69: 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Przybylski, A. K., K. Murayama, C. R. DeHaan, and V. Gladwell. 2013. Motivational, emotional, and behavioral correlates of fear of missing out. Computers in Human Behavior 29, 4: 1841–1848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnam, R. D. 2000. Bowling alone: The collapse and revival of American community. Simon & Schuster. [Google Scholar]

- Tandon, A., A. Dhir, S. Talwar, P. Kaur, and M. Mäntymäki. 2022. Social media induced fear of missing out (FoMO) and phubbing: Behavioural, relational and psychological outcomes. Technological Forecasting & Social Change 174: 121149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tandoc, E. C., P. Ferrucci, and M. Duffy. 2015. Facebook use, envy, and depression among college students: Is Facebooking depressing? Computers in Human Behavior 43: 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twenge, J. M. 2017. iGen: Why today’s super-connected kids are growing up less rebellious, more tolerant, less happy--and completely unprepared for adulthood--and what that means for the rest of us. Simon and Schuster. [Google Scholar]

- Valkenburg, P. M. 2022. Social media use and well-being: A review and synthesis. Annual Review of Psychology 73: 219–242. Available online: https://www.google.com/search?q=https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-020821-112328. [CrossRef]

- Vogel, E. A., and J. P. Rose. 2016. Self-comparison and the idealized images of Facebook. In The Psychology of Social Networking. De Gruyter: Vol. 1, pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Vogel, E. A., J. P. Rose, B. M. Okdie, K. Eckles, and B. Franz. 2015. Who compares and despairs? The effect of social comparison orientation on social media use and its outcomes. Personality and Individual Differences 86: 249–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, J. L., and J. M. Swank. 2021. An examination of college students’ social media use, fear of missing out, and mindful attention. Journal of College Counseling 24, 2: 132–145. Available online: https://www.google.com/search?q=https://doi.org/10.1002/jocc.12181. [CrossRef]

- Zupic, I., and T. Čater. 2015. Bibliometric methods in management and organization. Organizational Research Methods 18, 3: 429–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Topic | Topic Label | Representative Keywords | Cluster |

| Topic 0 | Social Comparison and Envy on Facebook | Facebook, self, comparison, envy, disclosure | Anxiety-oriented |

| Topic 1 | Body Image and Appearance-Related Anxiety | body, appearance, image, eating, dissatisfaction | Anxiety-oriented |

| Topic 2 | Fear of Missing Out (FoMO) and Problematic Use | fomo, missing, fear, phubbing, psmu | Anxiety-oriented |

| Topic 4 | Adolescent Problematic Use and Psychological Symptoms | adolescents, symptoms, use, smu, problematic | Anxiety-oriented |

| Topic 8 | Social Media Use and Sleep Quality | sleep, quality, anxiety, use, psmu | Anxiety-oriented |

| Topic 14 | Cyberbullying and Aggressive Online Behaviours | cyberbullying, bullying, aggression, victimization | Anxiety-oriented |

| Topic 5 | Perceived Online Social Support | support, social, perceived, online, capital | Connection-oriented |

| Topic 11 | Online Communities and Sense of Belonging | community, online, belonging, identity, support | Connection-oriented |

| Topic 3 | Social Media Discourse During the COVID-19 Pandemic | covid, 19, pandemic, tweets, public | Contextual and methodological |

| Topic 6 | AI-Based Depression Detection | depression, detection, learning, model, instagram | Contextual and methodological |

| Topic 7 | Online Discourse on Mental Health Stigma | stigma, mental, health, twitter, tweets | Contextual and methodological |

| Topic 9 | Student Learning and Educational Applications | students, learning, education, academic, teachers | Contextual and methodological |

| Topic 10 | Personality Traits and Motivations for Use | self, esteem, personality, use, narcissism | Contextual and methodological |

| Topic 12 | Political Participation and Information Diffusion | political, news, information, participation, fake | Contextual and methodological |

| Topic 13 | Branding, Marketing, and Consumer Behaviour | brand, consumer, purchase, intention, instagram | Contextual and methodological |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.