1. Introduction

Amidst the COVID-19 pandemic, staying informed became paramount, prompting heavy reliance on online networking sites for updates, with use being at an all time high (Statista, 2021). The phenomenon of “doomscrolling” emerged as individuals struggled to disengage from COVID-19-related news (Buchanan et al., 2021; Sharma et al., 2022), sparking concerns about its impact on the emotional wellness (Sandstrom et al., 2021). While initial scrutiny began exploring the apprehension (e.g., Bendau et al., 2021; Eden et al., 2020; Sewall et al., 2021), the impact of COVID-19-related online networking sites use on wellness remains largely unknown. The paper aims to assess the effects of different online networking sites usage patterns on individual wellness using a comprehensive longitudinal dataset spanning 34 waves, offering insights into individual causal relationships.

1.1. Comprehending Wellness and Social Networking

The paper explores howdifferent mediums of entertainment mediaimpact three key facets of subjective wellness: life satisfaction, positive affect, and negative affect. Building on Diener et al.’s (2018) typology of subjective wellness, which includes both cognitive evaluations and emotional experiences, the analysis distinguishes between different types of online networking sites use and the platforms employed.

online networking sites encompasses diverse subdimensions, including social networking sites (e.g., Facebook, Instagram), instant messaging apps (e.g., WhatsApp, Signal), and interactive video platforms (e.g., YouTube, TikTok) (Carr & Hayes, 2015). Research indicates that purposeful, active, and social uses of these platforms are generally linked to positive outcomes, while passive or non-purposeful usage correlates with negative effects (Frison & Eggermont, 2015; Verduyn et al., 2022). However, these generalizations have been recently debated (Valkenburg et al., 2022).

To better understand these effects, the paper distinguishes between three types of online networking sites use: posting (active use), reading (passive use), and liking/sharing (low-threshold active use) COVID-19-related content. It focuses on five popular platforms: Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, WhatsApp, and YouTube—among the most widely used in Austria at the time of the study.

Rather than relying on broad measures like total time spent online, the paper aims to offer a more refined analysis of how different online networking sites activities specifically affect wellness. While overly narrow measures might lack broader applicability, a balanced approach is needed to capture meaningful insights into the relationship between online networking sites use and subjective wellness.

1.2. Online Entertainment Platform Impact on Wellness

Research shows that more active online networking sites users tend to report slightly lower levels of wellness, including life satisfaction and feelings of loneliness (Meier & Reinecke, 2020). However, these effects are generally small and based mainly on correlational studies. A recent meta-analysis of experimental studies even failed to find significant causal links between active online networking sites use and lower wellness (Ferguson, 2024). These mixed findings can be explained by the differential susceptibility model (Valkenburg & Peter, 2013), which suggests that media effects vary widely among individuals. For instance, one study estimated that about 25% of consumers feel discomfort, 25% healthy impacts,and others neutral effects (Beyens et al., 2021). Despite claims of strong negative impacts (e.g., Twenge, 2017), two major media theories suggest otherwise:

Mood Management Theory (Zillmann, 1988): This theory argues that people subconsciously learn which types of media improve their moods based on personal needs. As a result, frequently used media are likely serving a positive regulatory function (Marciano et al., 2022).

Uses and Gratifications Theory (Katz et al., 1973): This theory takes a more conscious approach, asserting that individuals choose media based on expected benefits, such as mood improvement, information, or entertainment. Given the diverse benefits of social media, this helps explain its widespread appeal and use (Pelletier et al., 2020). Positive aspects may include social support, inspiration, and maintaining connections, while negative aspects could involve social comparison, misinformation, or emotional contagion (Clark et al., 2018; Hall & Liu, 2022; Vanden Abeele, 2021; Verduyn et al., 2022). Given these varied mechanisms, it’s unlikely that online networking sites has a uniformly strong impact—positive or negative—on wellness, making nuanced and moderate effects more probable.

In summary, while theories and empirical evidence show mixed effects of online networking sites on wellness, this variability underscores the complexity of how individuals experience and engage with these platforms.

1.3. Online Networking Sites During COVID-19

If I look at COVID-19 related use more specifically, how did the different mediums have an impact on wellness during the pandemic? Several uses and gratifications exist, which help explain why people used online networking sites frequently during the pandemic. Despite incorrect information, online networking sites provide a vast platform for disseminating accurate and timely information about COVID-19 (John Hopkins University, 2023). online networking platforms enable individuals get in touch with those in similar cases during the pandemic (Guazzini et al., 2022). Many mental health organizations and professionals utilize online networking sites to share tips, strategies, and resources for wellness at the time of the outspread virus. online networking sites campaigns and initiatives can promote positive COVID-19 behaviors, such as mask-wearing, physical distancing, hand hygiene, and vaccination (Hunt et al., 2022), which ultimately benefit wellness.

On the other hand, the effects might be negative, perhaps best explained by the following five mechanisms. online networking sites platforms can easily spread false or misleading information about COVID-19 (Li et al., 2020). Constant exposure to COVID-19-related content on online networking sites can lead to information overload and contribute to heightened anxiety levels (Fan & Smith, 2021). Discussions around COVID-19 are known for fostering negativity, with users sometimes engaging in cyberbullying and harassment. online networking sites often showcase the highlights and accomplishments of others, encouraging social comparison (Przybylski et al., 2013). Especially during a pandemic, seeing how others successfully cope with every-day challenges—for example, by baking banana bread, inventing creative games with kids, or exercising at home—might intensify feelings of inadequacy or FOMO, especially when individuals are unable to participate in similar activities due to restrictions or personal circumstances (Sharma et al., 2022).

Echoing the theoretical rationales outlines above, empirical studies have yielded mixed results. Some studies found negative effects, indicating that excessive online networking sites use for pandemic content led to compulsive behavior and increased stress levels, particularly due to upward social comparison (Stainback et al., 2020). Individuals who relied on online networking sites as their primary information source reported higher levels of anxiety and depression symptoms (Bendau et al., 2021). Doom-scrolling was associated with negative emotional experiences (Buchanan et al., 2021). On the other hand, some studies reported positive outcomes. Certain individuals experienced increased virtual community and social connectedness during the pandemic through social media, which contributed to their wellness (Guazzini et al., 2022). Additionally, identification with online networking sites networks was associated with reduced feelings of loneliness (Latikka et al., 2022). Several studies reported mostly neutral or dual effects of online networking sites use on wellness indicators (Eden et al., 2020; Sewall et al., 2021).

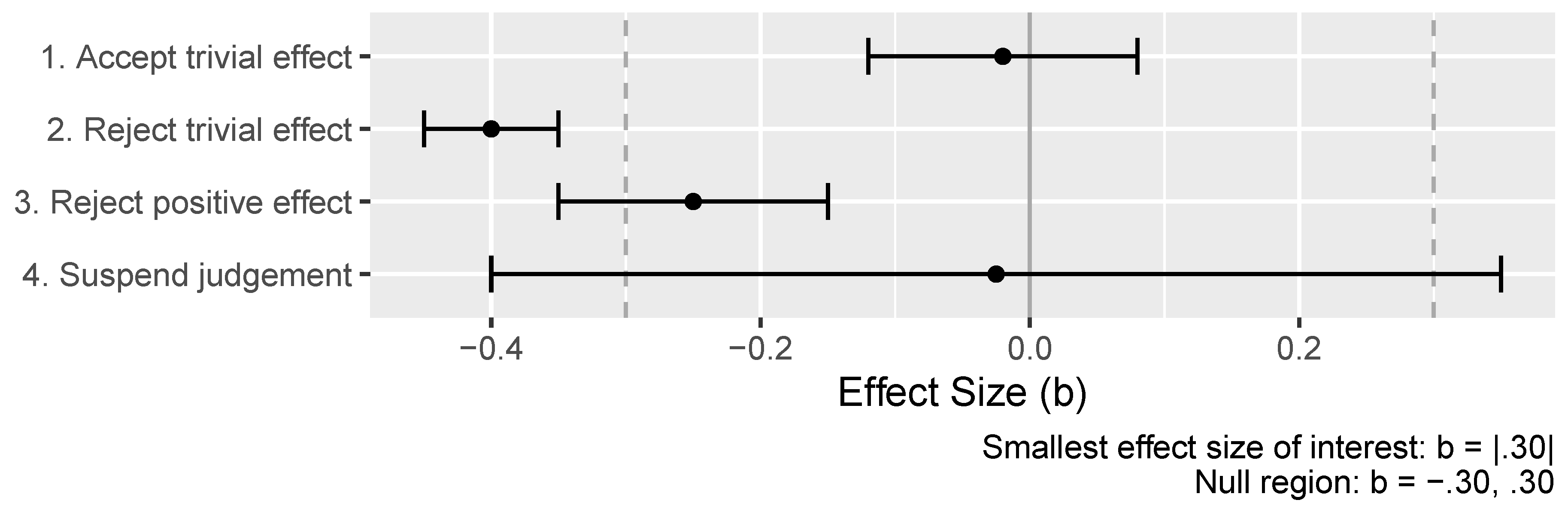

1.4. Littlest Impact Size of Interest

Exploring the preposition entails establishing the criteria for discerning a `trivial effect size.’ To achieve this, it is necessary to define the smallest effect size of interest (SESOI) (Anvari & Lakens, 2021). In this context, a trivial effect should fall below the threshold set by the SESOI (detailed below). Determining what constitutes a minimally intriguing, nontrivial effect is a matter with normative implications, making it challenging to arrive at a definitive, singular consensus. I propose the following SESOI as a suitable reference point for this study:

Norman et al. (2003) found that users can detect 7 forms of change in wellness. Therefore, on a scale of seven,four in media should correspond to least one pointer in wellness, which was measured on an eleven scale, and affect on a 5-point scale. Transposed to this scaling, the SESOI for life satisfaction is b = ±.30, and for positive and negative affect b = ±.15 (see online supplementary material).

2. Method

2.1. Data Analysis

2.1.1. Causality

Analyzing causal effects within non-experimental designs requires adopting an internal perspective. This entails evaluating how alterations in an individual’s media consumption directly impact changes in their own wellness. Consequently, this study exclusively investigates individual effects.

An essential strategy for isolating the genuine impact of variables is to control for confounding factors that influence both media use and wellness (Rohrer, 2018). In the context of individual analysis, this necessitates accounting for time-varying confounders (Rohrer & Murayama, 2023). However, a cautious balance must be maintained by not controlling for variables that mediate the relationship (Rohrer, 2018), as their inclusion could distort the evaluation of reaction. The paper, therefore, incorporated several control variables (see below), which have demonstrated connections with both usage of online networking platform and betterment and are likely not arbitrators. (Eger & Maridal, 2015).

Establishing causality necessitates determining a plausible temporal interval (Rohrer & Murayama, 2023). For instance, fluctuations in positive and negative affect call for shorter intervals, while the more enduring nature of life satisfaction implies longer intervals (Dienlin & Johannes, 2020). In this study, I examine the linkage between changes in online networking sites use and changes in effect within the same week. Specifically, I investigate if heightened pandemic-related online networking sites use during a week corresponds with enhanced or diminished affect during that same week. I consider a longer interval for life satisfaction, examining whether increased online networking sites use over the course of a week influences one’s life satisfaction at the week’s end. Supplementary analyses extend this investigation to observe how media use might affect wellness one or four months later.

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Wellness

Life fulfillment was estimated with the thing, “In light of everything, how fulfilled are you with your life in general these days?” from the European Social Review, with reactions from 0 (very disappointed) to 10 (very fulfilled).

Good influence was surveyed by asking respondents how frequently they felt (a) without a care in the world, (b) cheerful, and (c) ready to go over the course of the last week (World Wellbeing Association, 1998). Reaction choices went from 1 (never) to 5 (day to day). The scale showed great factorial fit, (66) = 69.42, p = .363, CFI = 1.00, RMSEA < .01, 90% CI < .01, .02, SRMR = .01, with high dependability ( = .85).

Pessimistic influence was estimated by getting some information about sensations of (a) forlornness, (b) irritation, (c) profound sorrow, (d) anxiety, (e) uneasiness, and (f) trouble in the previous week (World Wellbeing Association, 1998). The reaction choices were equivalent to for positive effect. The scale showed great factorial fit, (471) = 4012.14, p < .001, CFI = .98, RMSEA = .07, 90% CI [.07, .08], SRMR = .03, with solid dependability ( = .91). Every one of the three factors were estimated in each wave.

Coronavirus related online entertainment use was assessed in two aspects: sorts of correspondence and channels.

Correspondence types were evaluated with three things adjusted from Wagner et al. (2018), asking respondents how frequently they participated in exercises like perusing and posting about the Covid. Reactions went from 1 (a few times each day) to 5 (never), with things upset for examination.

Channel use was estimated utilizing five factors from Wagner et al. (2018), asking how frequently respondents followed data connected with the Crown emergency on stages like Facebook and Instagram, with comparable reaction choices and reversal for investigation.

Information via online entertainment use were gathered during waves 1, 2, 8, 17, 23, and 28 (see

Figure 1). New respondents addressed all Coronavirus related questions, permitting consideration of their information in the examinations, which utilized information from every one of the 34 waves.

2.2.2. Control Variables

To control for the impacts of Coronavirus related virtual entertainment use, stable factors included orientation (female, male, different), age, training (ten choices), origination in Austria (yes/no), guardians’ origin (no parent, one parent, the two guardians), and family size.

Changing covariates controlled remembered five things for everyday environments (self-detailed wellbeing, Coronavirus compression, pay, telecommuting, complete work hours), nine things on the utilization of explicit media sources, five things on outside exercises, and two mental measures (locus of control and hazard attitude).

3. Results

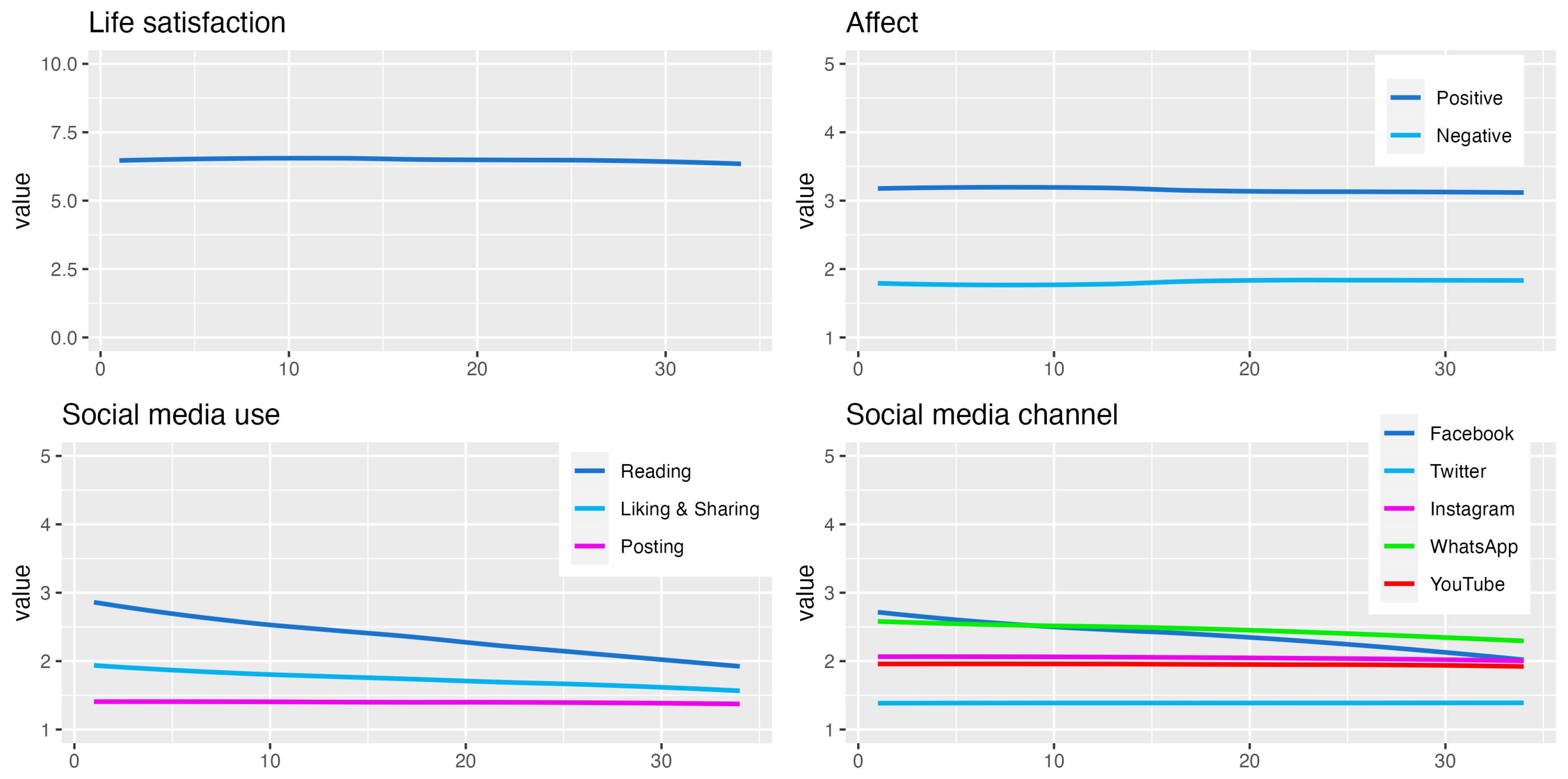

The wellness measures remained stable throughout data collection, while engagement with pandemic-related online networking sites content significantly decreased, particularly in reading, sharing, and liking. This decline likely occurred because data collection started at the end of March 2020, approximately three months after the pandemic began, suggesting that interest in COVID-19 content had already started to wane.

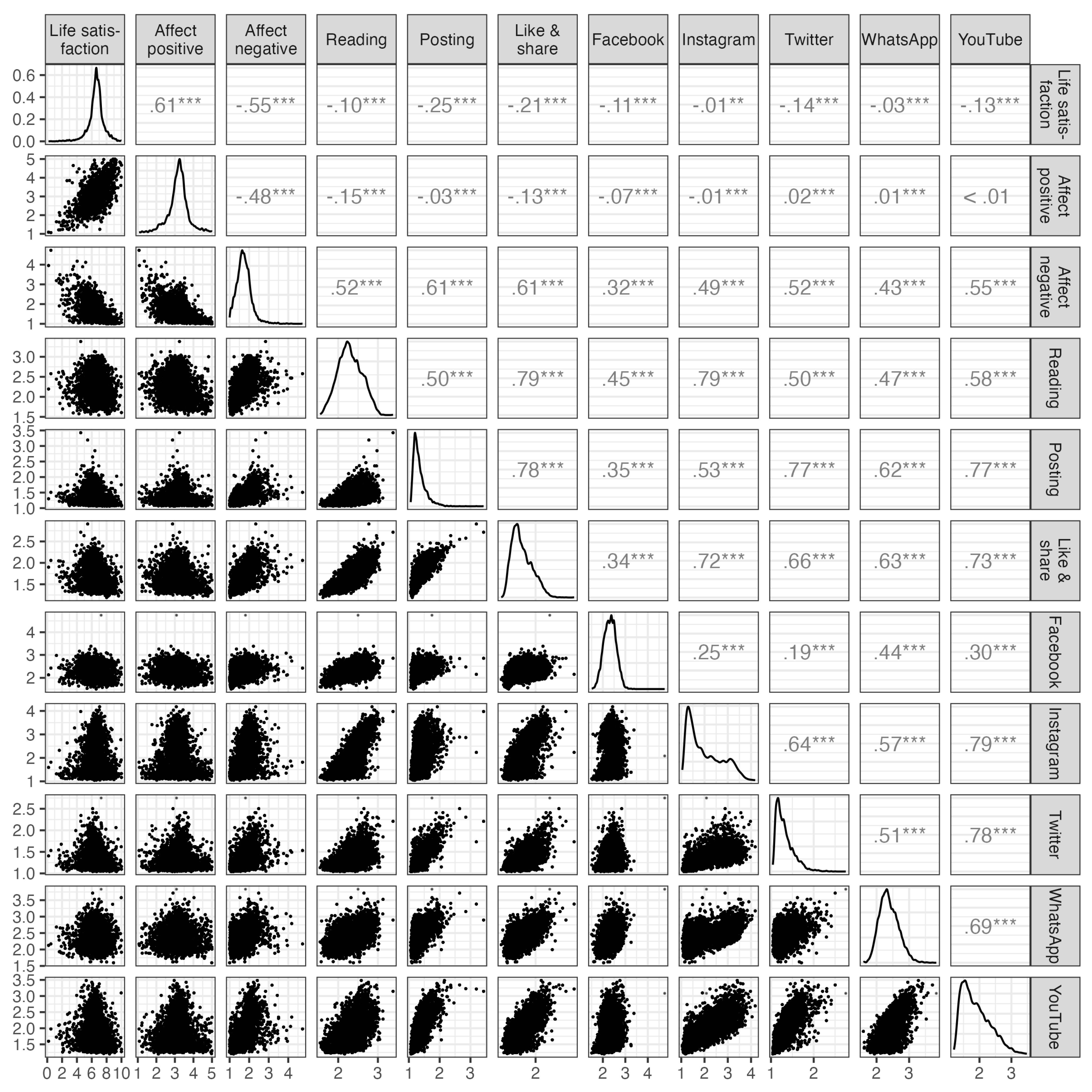

Using average traits across all waves to present a consistent overview, I examined the relationships in online networking sites and betterment (see Figure ??). Generally, individuals engaging more with COVID-19-related content reported lower wellness, with increased negative affect. Specifically, those who frequently read, liked, shared, or posted about COVID-19 experienced notably more unfruitful impact (r = .61). It’s important to note that these results reflect between-individual relationships rather than causal within-individual effects.

Figure 2.

Wellness and media usage.

Figure 2.

Wellness and media usage.

Figure 3.

Descriptive statistics and correlations.

Figure 3.

Descriptive statistics and correlations.

3.1. Preregistered Analyses

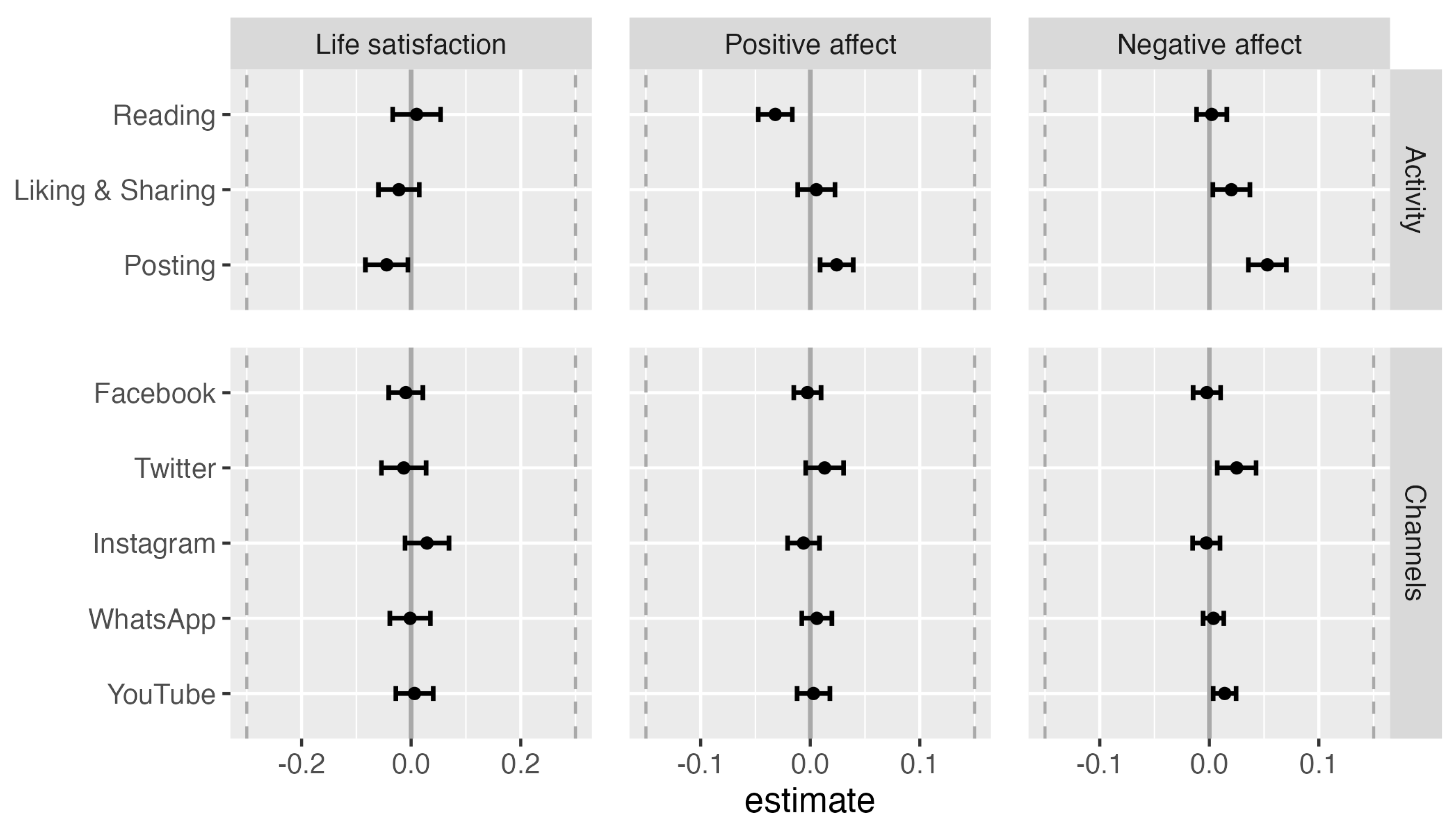

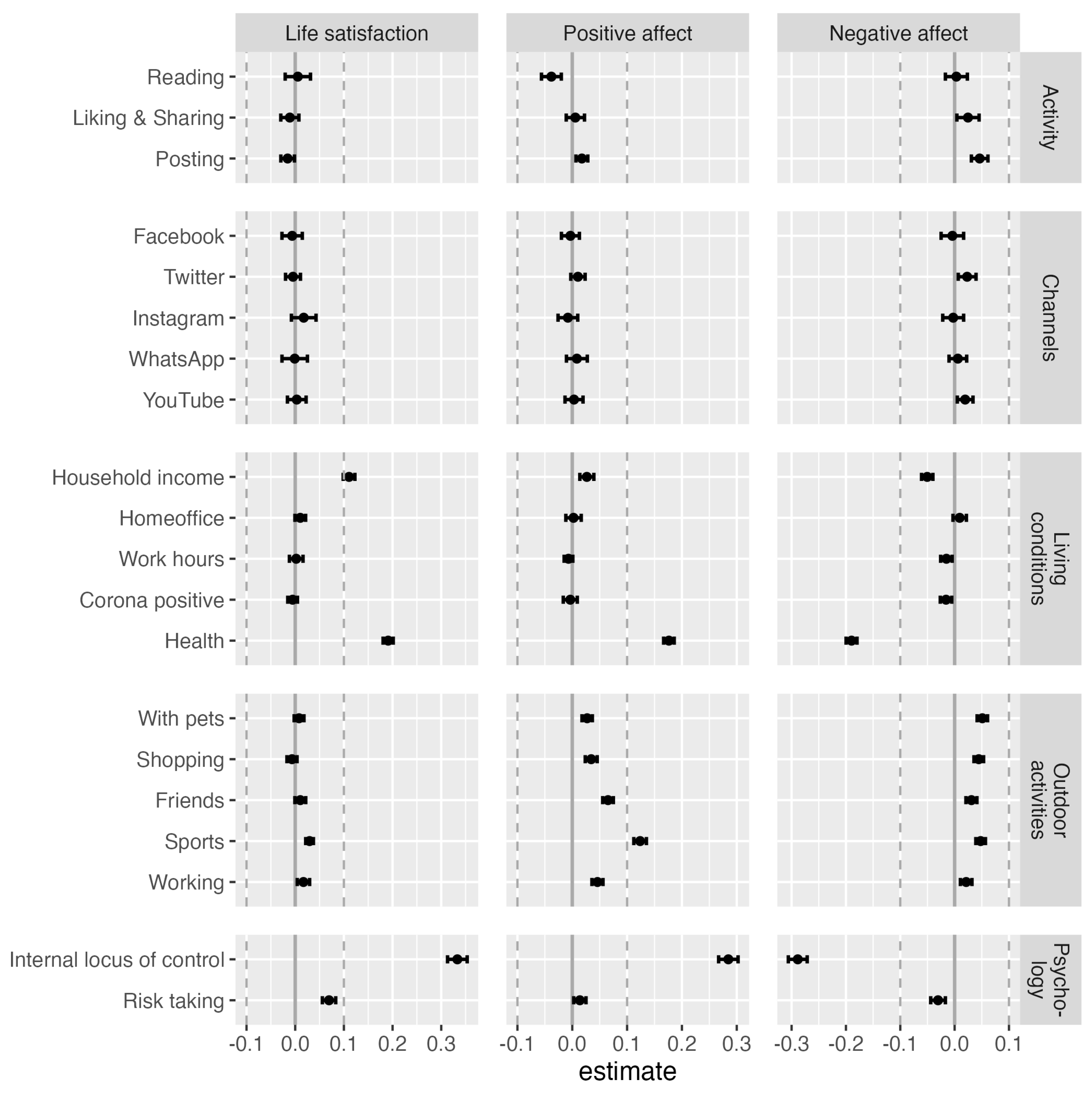

The analysis of COVID-19-related communication types (reading, sharing, posting) found most effects within the null region, indicating trivial impacts on life satisfaction ( [95% CI -0.06, 0.01]).

Notably, reading more COVID-19 content slightly decreased positive affect ( [95% CI -0.05, -0.02]), while liking and sharing increased negative affect ( [95% CI 0.04, 0.07]). Posting decreased life satisfaction ( [95% CI -0.08, -0.01]) and increased negative affect ( [95% CI 0.04, 0.07]), but also led to slightly higher positive affect ( [95% CI 0.01, 0.04]).

For online networking sites channels, increased Facebook use had no significant impact on life satisfaction ( [95% CI -0.04, 0.02]). However, Twitter and YouTube use was linked to higher negative affect ( [95% CI 0.01, 0.04] and [95% CI <0.01, 0.02]), remaining within the null region.

For an overview of all individual effects, see

Figure 4.

3.2. Exploratory Analyses

To better understand the results, I examined the effect sizes of the covariates using standardized scales for comparability across different variables. Following Cohen’s convention, a small effect size is defined as .

The findings revealed several effects that crossed or fell outside the small effect size threshold, indicating their significance. Notably, a decrease in physical health significantly impacted wellness: life satisfaction ( [95% CI .18, .20]), positive affect ( [95% CI .17, .19]), and negative affect ( [95% CI -.20, -.18]). Additionally, increased outdoor exercise meaningfully enhanced positive affect ( [95% CI .11, .14]).

The most influential factor was the internal locus of control. Greater feelings of control correlated with increased life satisfaction ( [95% CI .31, .35]) and positive affect ( [95% CI .27, .30]), while reducing negative affect ( [95% CI -.31, -.27]).

Because life satisfaction is more stable than affect, the effects of communication might materialize some time later. I hence also tested the effects across the longer intervals of one month and four months. Results showed that all effects disappeared. No effect remained significant, implying that at least in this case in this case effects take place on a shorter interval.

Finally, as suggested by the differential susceptibility of media effects model, media effects can depend on dispositional factors, developmental stages, or cultural norms (Valkenburg & Peter, 2013), such as gender and age (Orben et al., 2022). I hence reran the analyses, differentiating effects for boys and girls and for age cohorts. The results showed that effects did not differ across genders. The effects also did not depend on age. However, one effect stood out and was significant. Compared to the middle age category Generation X, results showed that if users from Generation Z posted more COVID-19 content than usual this lead to significantly more negative affect ( = .04 [95% CI .01, .06]).

4. Discussion

This study, drawn from a representative panel spanning 34 phases within the Austrian population, investigated the impact of pandemic related online site usage on wellness.

To explore if these effects translated into impacting within aperson, it was examined whether individual changes in media consumption corresponded with individual changes in wellness. As expected and aligned with the literature, increased consumption of COVID-19 content did not significantly decrease wellness at a meaningful level. While several statistically significant effects emerged, their magnitudes were notably small.

Posting more COVID-19 content reduced life satisfaction slightly while elevating both positive and negative effects. The effects, although statistically significant, fell within a predefined range that was considered insignificant.

That said, there is no consensus among scholars as to when effects become practically relevant and meaningful. If I adopt a more liberal and cautious perspective, the study indicates a tendency for COVID-19-related online networking sites usage to impact wellness negatively more frequently than positively. Notably, several statistically significant negative effects were observed, contrasting with a single positive effect. Hence, although impacts were overall very small, the trend was for effects to be negative.

These results align with prior research highlighting that online networking sites usage is rather associated with elevated negative affect but not reduced life satisfaction (Meier & Reinecke, 2020). The study suggests that varying communication types and channels warrant separate analyses. Reading COVID-19-related content slightly reduced positive effects, while liking, sharing, and posting increased negative effects slightly. Posting COVID-19-related comments slightly increased both negative and positive affects, while it reduced life satisfaction. Posting COVID-19 content was more negative for Generation Z, potentially reflecting the broader negative effects of online networking sites on this generation. Together, this finding is aligned with recent work challenging the assumption that active use is inherently beneficial and passive use detrimental (Valkenburg et al., 2022). Notably, communication channels exhibited differences. Twitter and YouTube appeared more negative, whereas Instagram, WhatsApp, and Facebook were neutral.

Several limitations exist. While the study’s focus on individual effects enhances the reaction, challenges exist related to additional relevant confounding exogenous variables not included here (Rohrer, 2018), the correct definition of the SESOI (Anvari & Lakens, 2021), and the exact measurement of media use (Scharkow, 2016). As noted above, different operationalizations of COVID-19 related online networking sites use might lead to different results. For example, the measures of online networking sites use did not include interpersonal communication about COVID-19-related content, which might result in more positive outcomes (Frison & Eggermont, 2015). While this study did not find meaningful individual effects of online networking sites use on wellness, between person analyses revealed strong negative correlations. Alternative causal processes not explored in this paper might explain these correlations. The study’s results are applicable primarily to Western societies and may not hold true in different cultural contexts.

The study’s findings conclude that COVID-19-related online networking sites activity minimally affects wellness, with other factors such as health and physical activity playing more substantial roles. In light of these minimal effects, concerns over COVID-19-related online networking sites engagement on wellness could not be substantiated.

References

- Anvari, F., & Lakens, D. (2021). Using anchor-based methods to determine the smallest effect size of interest. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 96, 104159. [CrossRef]

- Bell, A., Fairbrother, M., & Jones, K. (2019). Fixed and random effects models: Making an informed choice. Quality & Quantity, 53(2), 1051–1074. [CrossRef]

- Bendau, A., Petzold, M. B., Pyrkosch, L., Mascarell Maricic, L., Betzler, F., Rogoll, J., Große, J., Ströhle, A., & Plag, J. (2021). Associations between COVID-19 related media consumption and symptoms of anxiety, depression and COVID-19 related fear in the general population in Germany. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, 271(2), 283–291. [CrossRef]

- Beyens, I., Pouwels, J. L., van Driel, I. I., Keijsers, L., & Valkenburg, P. M. (2021). online networking sites use and adolescents’ wellness: Developing a typology of person-specific effect patterns. Communication Research. [CrossRef]

- Buchanan, K., Aknin, L. B., Lotun, S., & Sandstrom, G. M. (2021). Brief exposure to online networking sites during the COVID-19 pandemic: Doom-scrolling has negative emotional consequences, but kindness-scrolling does not. PLOS ONE, 16(10), e0257728. [CrossRef]

- Carr, C. T., & Hayes, R. A. (2015). Social Media: Defining, Developing, and Divining. Atlantic Journal of Communication, 23(1), 46–65. [CrossRef]

- Clark, J. L., Algoe, S. B., & Green, M. C. (2018). Social Network Sites and wellness: The Role of Social Connection. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 27(1), 32–37. [CrossRef]

- Diener, E., Lucas, R. E., & Oishi, S. (2018). Advances and open questions in the science of subjective wellness. Collabra: Psychology, 4(1), 15. [CrossRef]

- Dienes, Z. (2014). Using Bayes to get the most out of non-significant results. Frontiers in Psychology, 5. [CrossRef]

- Dienlin, T., & Johannes, N. (2020). The impact of digital technology use on adolescent wellness. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 22(2), 135–142. [CrossRef]

- Eden, A. L., Johnson, B. K., Reinecke, L., & Grady, S. M. (2020). Media for coping during COVID-19 social distancing: Stress, anxiety, and psychological wellness. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 577639. [CrossRef]

- Eger, R. J., & Maridal, J. H. (2015). A statistical meta-analysis of the wellbeing literature. International Journal of Wellbeing, 5(2), 45–74. [CrossRef]

- Enders, C. K. (2022). Applied missing data analysis (Second Edition). The Guilford Press.

- Fan, J., & Smith, A. P. (2021). Information overload, wellbeing and COVID-19: A survey in China. Behavioral Sciences, 11(5), 62. [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, C. J. (2024). Do online networking sites experiments prove a link with mental health: A methodological and meta-analytic review. Psychology of Popular Media. [CrossRef]

- Frison, E., & Eggermont, S. (2015). Exploring the relationships between different types of Facebook use, perceived online social support, and adolescents’ depressed mood. Social Science Computer Review, 1–19. [CrossRef]

- Guazzini, A., Pesce, A., Marotta, L., & Duradoni, M. (2022). Through the second wave: Analysis of the psychological and perceptive changes in the Italian population during the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(3), 1635. [CrossRef]

- Haidt, J. (2024). The anxious generation: How the great rewiring of childhood is causing an epidemic of mental illness. Penguin Press.

- Hall, J. A., & Liu, D. (2022). online networking sites use, social displacement, and wellness. Current Opinion in Psychology, 46, 101339. [CrossRef]

- Hamaker, E. L. (2014). Why researchers should think “individual”: A paradigmatic rationale. In M. R. Mehl, T. S. Conner, & M. Csikszentmihalyi (Eds.), Handbook of research methods for studying daily life (Paperback ed.). Guilford.

- Hunt, I. de V., Dunn, T., Mahoney, M., Chen, M., Nava, V., & Linos, E. (2022). A social media-based public health campaign encouraging COVID-19 vaccination across the United States. American Journal of Public Health, 112(9), 1253–1256. [CrossRef]

- John Hopkins University. (2023). COVID-19 Map. In Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center. https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html.

- Katz, E., Blumler, J. G., & Gurevitch, M. (1973). Uses and Gratifications Research. Public Opinion Quarterly, 37(4), 509–523.

- Kaye, D. B. V., Caballero, C., Greifeneder, R., Muri, J., & Derfler-Rozin, R. (2023). Resisting crisis: How a construal shift can improve collective pandemic behaviors. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 179, 104082.

- Keles, B., McCrae, N., & Grealish, A. (2020). A systematic review: The influence of online networking sites on depression, anxiety, and psychological distress in adolescents. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth, 25(1), 79–93. [CrossRef]

- Kross, E., Verduyn, P., Demiralp, E., Park, J., Lee, D. S., Lin, N., Shablack, H., Jonides, J., & Ybarra, O. (2013). Facebook use predicts declines in subjective wellness in young adults. PLOS ONE, 8(8), e69841. [CrossRef]

- LaRose, R., Mastro, D., & Eastin, M. S. (2001). Understanding internet usage: A social-cognitive approach to uses and gratifications. Social Science Computer Review, 19(4), 395–413. [CrossRef]

- Leiner, D. J., Hartmann, S., & Nutz, L. (2023). Too much inspiration: The effects of self-improvement content on Instagram and TikTok on psychological wellness. New Media & Society.

- Lucas, R. E. (2007). Adaptation and the hedonic treadmill. In D. Kahneman, E. Diener, & N. Schwarz (Eds.), wellness: The foundations of hedonic psychology (Paperback ed.). Russell Sage Foundation.

- McCrae, N., & Grealish, A. (2021). Widespread unhappiness and lack of self-confidence among adolescents. Journal of Adolescence, 87, 50–58.

- Meier, A., & Reinecke, L. (2016). The Covariation Between Social Networking Site Use and wellness: A Meta-Analysis. Communications, 41(2), 65–88. [CrossRef]

- Neumann, P., Ehlers, E., Gossner, L., Banse, H., Brailovskaia, J., Hummel, K., Teismann, T., Wolter, C., Spitzner, A., Schecke, H., Margraf, J., & Schneider, S. (2021). Adolescents’ relations with family, peers, and teachers in the first COVID-19-related school closures: The role of socioeconomic status. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(9), 4829. [CrossRef]

- Puukko, K., Hietajärvi, L., Maksniemi, E., Alho, K., & Salmela-Aro, K. (2020). online networking sites use and depressive symptoms: A longitudinal study from early to late adolescence. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(16), 5921. [CrossRef]

- Reid, M. E., Davis, C. F., Berryman, M. B., Carlson, E., LeGreve, R. M., Banks, C. J., & Thomas, K. J. (2022). Perceived social support and coping among older adults during COVID-19: Associations with anxiety, depression, and worry. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 41(1), 44–54.

- Romer, D., & Jamieson, K. H. (2021). The psychological impact of COVID-19 on America: Perceptions, media exposure, and public health behaviors. Social Science & Medicine, 276, 113828. [CrossRef]

- Verduyn, P., Ybarra, O., Résibois, M., Jonides, J., & Kross, E. (2020). Do social network sites enhance or undermine subjective wellness? A critical review. Social Issues and Policy Review, 14(1), 274–302. [CrossRef]

- Veronese, G., Castiglioni, M., Barola, G., Said, M., & Pereira, L. (2021). Together with COVID-19, social and mental suffering is another virus: Results from a cross-sectional study on adolescents. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 15(1), 18.

- Weinstein, E., & Némorin, S. (2021). Positive and negative implications of digital media for adolescent development and wellness. Computers in Human Behavior Reports, 3, 100086. [CrossRef]

- Yang, J. Z., Chu, H., & Shen, F. (2020). Exposure to antagonistic content on online networking sites and cross-cutting discussion: Unpacking the process in the context of the 2016 U.S. election. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 64(3), 399–420.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).