1. Introduction

Cell membranes are complex, dynamic structures composed of lipids, proteins, and carbohydrates that together form a selectively permeable barrier crucial for cellular integrity and function. Beyond serving as a passive boundary, membranes are active participants in virtually every aspect of cell physiology, including signal transduction, intracellular transport, energy conversion, and intercellular communication. A critical and often underappreciated property of these membranes is their curvature—defined as the local bending or deformation of the lipid bilayer. This curvature is not static but is dynamically regulated to accommodate processes such as vesicle budding, membrane fission and fusion, endocytosis, exocytosis, and the formation of specialized subcellular structures like filopodia and lamellipodia.

Membrane curvature is not merely a geometric characteristic; it is a biophysical signal that governs and responds to a wide range of cellular cues. Certain proteins—such as those containing Bin/Amphiphysin/Rvs (BAR) domains—and lipids with intrinsic curvature properties, act as curvature sensors and inducers, helping the membrane adapt to functional demands. Importantly, changes in curvature often coincide with biochemical signaling events, suggesting that cells interpret curvature as a spatial code that guides molecular localization and activity. For example, the distribution and activation of small GTPases, such as Ras, which require precise membrane anchoring to exert their oncogenic functions, are increasingly understood to be regulated by curvature-driven compartmentalization (1).

In the context of oncogenesis, these processes become dysregulated. Cancer cells often exhibit alterations in lipid metabolism, cytoskeletal dynamics, and expression of curvature-modulating proteins, all of which converge to distort membrane architecture. The distortions are not incidental, but are functionally significant, enabling cancer cells to internalize and recycle growth factor receptors, resist apoptosis, reorganize the cytoskeleton for migration, and secrete pro-tumorigenic factors via vesicles. Moreover, there are recent reports that membrane curvature can directly influence the localization and activation of oncogenic signaling pathways, including PI3K/AKT, MAPK, and notably Ras. For instance, epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT), a process critical for invasion and metastasis, has been shown to involve curvature-dependent recruitment of Ras to the plasma membrane in response to TGFβ stimulation (2, 3).

Despite the emerging importance, membrane curvature remains a relatively underexplored dimension of cancer biology. Most cancer-focused studies emphasize genetic and biochemical alterations, while overlooking the physical and mechanical properties of cells that are equally vital to disease progression. However, understanding how cancer cells sense, generate, and exploit membrane curvature may reveal new mechanisms of malignancy and open avenues for therapeutic intervention. This is particularly pertinent as technologies such as super-resolution microscopy, curvature-sensitive biosensors, and curvature-responsive drug delivery systems become more accessible and sophisticated.

This review aims to provide a comprehensive overview of membrane curvature in cancer. We begin by outlining the molecular mechanisms that generate and sense membrane curvature, followed by an examination of how curvature modulates key hallmarks of cancer hsuch as vesicle trafficking, receptor signaling, organelle morphology, and motility. We then explore how these processes are co-opted by oncogenic pathways—especially Ras—and conclude by discussing emerging therapeutic opportunities that exploit curvature-based vulnerabilities. By integrating biophysical principles with cancer signaling biology, we aim to establish membrane curvature as a central and actionable component of tumor development and treatment. (4)

2. Mechanisms of Membrane Curvature Generation

Disrupting membrane curvature—via hyposmotic shock or caveolae perturbation—releases Ras from the membrane, thereby blunting signaling. This finding demonstrates that membrane biophysics can directly regulate oncogenic signaling strength and duration.3

Mechanistically, this process is dependent on the lipid-modified C-terminal hypervariable region of Ras, which senses membrane architecture. Ras membrane localization is essential for GTP-loading and downstream activation. This reveals a novel feedback loop: TGFβ signaling induces curvature that enhances Ras activation, which in turn sustains TGFβ/SMAD signaling, driving EMT and metastatic progression(3).

Recent experimental findings by Damalas et al. (2022) have elucidated a compelling mechanism linking TGFβ-induced membrane curvature changes to Ras oncoprotein plasma membrane localization during EMT. In breast cancer cells, TGFβ-1 treatment significantly increases positive membrane curvature, which is detected by curvature-sensing proteins and coincides with the relocalization of H-ras and, to a lesser extent, K-ras to the plasma membrane(3, 5).

2.1. Lipid Composition and Asymmetry

Membrane curvature is the result of a combination of intrinsic biophysical forces and dynamic cellular machinery. Cells must constantly generate, sense, and modulate curvature to coordinate trafficking, morphogenesis, and signaling. This section describes the molecular and structural mechanisms through which curvature is established, with particular focus on their dysregulation in cancer(6).

2.2. Curvature-Sensing and -Generating Proteins

Proteins that sense or induce curvature are fundamental to membrane remodeling. Chief among these are the Bin/Amphiphysin/Rvs (BAR) domain proteins, which recognize and stabilize curved membrane regions. Proteins, such as amphiphysin, endophilin, FCHo, and CIP4, engage membranes through electrostatic and hydrophobic interactions. Membrane curvature can be generated through two principal mechanisms: (1) the insertion of amphipathic helices or hydrophobic protein motifs into one leaflet of the lipid bilayer, which creates local asymmetry and deforms the membrane, and (2) the introduction of structural scaffolding by proteins with intrinsically curved domains (such as BAR, F-BAR, or ENTH domains), which impose their shape onto the membrane surface to stabilize and propagate curvature (7, 8). The expression or activity of these proteins may be altered in cancer, with consequences for the curvature dynamics. However, their primary mechanistic role remains the physical modulation of membrane shape to facilitate processes like vesicle formation and cytoskeletal coordination(9).

The asymmetry of cellular membranes is maintained by lipid flippases, floppases, and scramblases, whose activities are often altered in cancer. Tumor cells typically exhibit dysregulated lipid metabolism, favoring the synthesis of curvature-inducing lipids that support vesicle trafficking and membrane flexibility. Furthermore, oncogenic signaling pathways such as PI3K/AKT and Ras influence phospholipid turnover, thereby linking lipid composition to both membrane shape and signaling competence(10).

Lipids are the primary structural components of membranes, and their shape strongly influences membrane curvature. Cone-shaped lipids such as phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) and cardiolipin promote negative curvature, while inverted cone-shaped lipids like lysophosphatidylcholine (LPC) favor positive curvature. Cylindrical lipids such as phosphatidylcholine (PC) stabilize flat bilayers. The asymmetric distribution of these lipids between the inner and outer membrane leaflets introduces spontaneous curvature (11).

2.3. Cytoskeletal Contributions to Curvature

The cytoskeleton, particularly actin filaments and their regulatory proteins, plays a key mechanical role in generating membrane curvature. Actin polymerization produces protrusive forces that deform the plasma membrane, forming structures such as lamellipodia and filopodia. This is initiated by nucleators like the Arp2/3 complex and formins, which define filament architecture. Actin-binding proteins such as myosin II generate contractile forces that further assist in membrane invagination, particularly during vesicle scission. These cytoskeletal processes are tightly coordinated with curvature-sensing proteins, ensuring that membrane remodeling events occur with spatial and temporal precision(12).

Such curvature-sensing proteins have been show toregulate the localization of signaling complexes, including Ras nanoclusters, which preferentially localize to curved, lipid raft-rich domains to enhance signaling amplitude(13) , thereby providing spatial precision to oncogenic signals(4).

There is also evidence that mechanical stress from the extracellular matrix (ECM) or neighboring cells can induce curvature changes that activate mechanotransductive pathways, including those involving YAP/TAZ and Ras (14).

BAR domain proteins function by two primary mechanisms: insertion of amphipathic helices into the bilayer, which creates local distortion, and scaffolding, where the curved structure of the protein molds the membrane. ENTH (epsin N-terminal homology) and F-BAR proteins act similarly. These proteins are often overexpressed or hyperactivated in cancer and have been linked to enhanced endocytosis, altered receptor trafficking, and metastasis (15).

Proteins that sense or induce curvature are key regulators of membrane remodeling. Among these, the Bin/Amphiphysin/Rvs (BAR) domain family stands out. These proteins—such as amphiphysin, endophilin, FCHo, and CIP4 bind to curved membranes via electrostatic and hydrophobic interactions and can both stabilize and amplify curvature(8, 16).

2.4. Membrane Tension and Mechanical Forces

Membrane tension, which is the in-plane force within the lipid bilayer, directly influences membrane flexibility. Lower tension allows for easier deformation, while high tension resists curvature. This parameter is dynamically modulated by cellular processes including cytoskeletal rearrangement, osmotic pressure changes, and membrane trafficking. Mechanotransduction pathways integrate these mechanical cues, allowing cells to modulate curvature in response to physical stimuli(17). At the mechanistic level, tension serves as a gatekeeper for curvature-generating events like endocytosis and filopodia formation (18, 19).

This machinery is hyperactivated in cancer. For instance, overexpression of Arp2/3 and formins correlates with invasive phenotypes, and curvature-sensitive complexes promote invadopodia formation during matrix degradation and invasion(20).

Myosin II and other actin-binding proteins generate contractile forces that contribute to membrane invagination and vesicle scission. These forces are integrated with curvature-sensing domains in endocytic proteins, enabling coordination between the cytoskeleton and membrane remodeling (21).

Similarly, actin polymerization at the membrane generates pushing forces, leading to protrusions such as lamellipodia and filopodia. Nucleators like the Arp2/3 complex and formins initiate and organize these filaments, while cofilin and gelsolin modulate filament turnover (22).

2.5. Protein Crowding and Phase Separation

In addition to lipid composition and cytoskeletal forces, membrane curvature is also influenced by protein crowding and phase separation. High local concentrations of membrane-bound proteins generate lateral pressure, which can promote local curvature. Similarly, the formation of liquid-like domains through protein phase separation can concentrate curvature-inducing factors, such as BAR domain proteins and lipid-modifying enzymes. These microdomains create specialized regions of the membrane with distinct curvature and functional properties, enabling compartmentalization of signaling and trafficking processes(23, 24).

2.6. Organelle-Specific Curvature Regulation

Organelles maintain a characteristic membrane curvature that is related to the function. This is achieved through the action of specialized proteins that stabilize or induce curvature. For example, the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) relies on reticulons and atlastins to maintain a tubular network, while mitochondrial fission is driven by the curvature-inducing protein DRP1. Increase in fission promotes the metabolic reprogramming toward glycolysis (Warburg effect). Fission also aids mitophagy and resistance to apoptosis (25). 36Similarly, dynamic changes in the curvature of the Golgi apparatus are mediated by lipid composition and cytoskeletal tension. These organelle-specific mechanisms demonstrate how curvature is tightly regulated across intracellular compartments in order to support diverse cellular functions(26).

3. Functional Roles of Membrane Curvature in Cancer

In addition to gene overexpression, epigenetic regulation and post-translational modifications (PTMs) also modulate the function of curvature-related proteins. PTMs, including palmitoylation and farnesylation, dictate the membrane localization of Ras and sensitivity to curvature. Such lipid modifications are regulated by enzymes such as farnesyltransferase (FTase) and acyl-protein thioesterases, which are themselves altered in certain cancers. Thus, curvature regulation is not only a product of genetic changes but may also be a consequence of dynamic post-translational and epigenetic programming(27).

Similarly, acetylation or phosphorylation of BAR domain proteins can alter membrane affinity and curvature-sensing capacity. Notably, histone modifications near genes encoding for curvature modulators like amphiphysin or EHD2 have been observed in breast and prostate cancer datasets, suggesting transcriptional deregulation via epigenetic means(28).

3.1. Endocytosis and Receptor Recycling

The flexibility of membranes is not merely a structural feature but also serves as a regulatory axis for nearly every aspect of cancer cell behavior. For example, membrane curvature affects intracellular trafficking, endocytosis, organelle dynamics, and signal transduction, all of which are hijacked in malignancy.Both clathrin-mediated and clathrin-independent endocytosis pathways are often upregulated in cancer cells in order to support recycling rather than degration of growth factor receptors such as EGFR, HER2, MET, and integrins(29, 30). These receptors are responsible for transmitting mitogenic and survival signals, and their sustained recycling promotes oncogenic signaling persistence(31). Curvature-inducing proteins, including clathrin, dynamin, and BAR domain family members, facilitate vesicle budding and scission. Internalized receptors continue to signal from endosomal compartments, where curvature helps define specialized signaling microdomains, amplifying pathways like MAPK and PI3K/AKT(32). In this context, dynamin is frequently upregulated in aggressive tumors and facilitates scission of endocytic vesicles, including those that internalize EGFR and other mitogenic receptors(33). Similarly, increased expression of F-BAR proteins like CIP4 enhances lamellipodia formation and is associated with poor prognosis in breast and lung cancers. Importantly, these proteins also form physical and functional interactions with small GTPases such as Ras, Rac1, and Cdc42, amplifying curvature-dependent motility and invasion(34, 35).

This section details how curvature contributes to hallmark cancer processes.

3.2. Exocytosis and Secretion

Curvature also plays a pivotal role in the exocytosis of vesicles, with the consequent release of signaling molecules and extracellular vesicles. Cancer cells exploit this mechanism to secrete matrix-degrading enzymes, cytokines, and pro-tumorigenic exosomes. Proteins such as SNAREs and Rab GTPases coordinate vesicle docking and fusion, processes that require tightly regulated membrane curvature. Elevated exosome release in Ras-driven cancers reflects the upregulation of curvature-sensitive trafficking pathways, which promote intercellular communication and metastatic niche formation(36).

Ras isoforms localize to distinct subcellular membranes during oncogenic activation. For example, recycling endosomes enriched in curvature and lipid rafts serve as hubs for KRAS nanocluster formation, enhancing MAPK and PI3K pathway activation(37).

3.3. Organelle Morphology and Function

As already mentioned, the shape and function of cellular organelles is closely related to membrane curvature. Morphological changes may support cancer cell proliferation, migration, and stress resistance(38). For example, increases in mitochondrial fission mediated by DRP1, impact the metabolism and increase the resistance to cell death. Similarly, the shape of the ER adapts to meet increased protein synthesis demands, while Golgi fragmentation, which is partly curvature-dependent, enhances secretory activity(39).

This increase depends on proteins like SNAREs, Rab GTPases, and curvature-modifying lipids, which coordinate vesicle docking and fusion. In Ras-driven cancers, the increase in exosome release involves vesicles loaded with oncogenic cargo, including mutant KRAS, which can be horizontally transferred to other cells, propagating malignant signaling(36).

Similarly, increases in exocytosis of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), cytokines, and extracellular vesicles (EVs), including exosomes and microvesicles promote matrix degradation, immune evasion, angiogenesis, and metastatic niche formation(40).

3.4. Cell Motility and Invasion

Cancer cell motility involves the formation of curved plasma membrane structures such as lamellipodia, filopodia, and invadopodia. These are generated through coordinated actin polymerization and the recruitment of curvature-generating proteins like BAR domain family members. Curvature enables directional cell movement and extracellular matrix degradation, facilitating invasion. Small GTPases like Rac1 and Cdc42 regulate these processes downstream of oncogenic Ras, integrating curvature dynamics with cytoskeletal remodeling and signaling activation(8).

3.5. TGFβ-Induced Membrane Curvature and Ras Activation

We have previously reported that TGFβ signaling induces membrane curvature changes that facilitate the relocalization of Ras to the plasma membrane during epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT)(3). This curvature-dependent Ras recruitment enhances downstream signaling, reinforcing TGFβ/SMAD activity and promoting metastatic progression. These findings reveal a feedback mechanism where extracellular cues modulate membrane shape to spatially organize oncogenic signals, with curvature serving as a physical determinant of Ras activation efficiency(3).

Small GTPases such as Rac1 and Cdc42—often downstream of Ras—activate actin nucleators like Arp2/3 to generate curvature-associated motile structures. Additionally, invadopodia formation is enhanced in cells undergoing epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT), where curvature-sensitive proteins concentrate at leading edges to promote directional invasion(41).

Membrane protrusions such as lamellipodia, filopodia, and invadopodia are hallmark features of invasive cancer cells. These structures require the coordinated action of actin polymerization and BAR domain proteins to generate and sustain membrane curvature. These protrusions not only allow cells to migrate but also facilitate degradation of the extracellular matrix (ECM).

4. Molecular Dysregulation of Curvature Mechanisms in Cancer

Advanced super-resolution techniques such as STED and PALM, when combined with curvature-specific probes based on BAR domains or lipid-binding motifs, provide a new dimension for patient stratification by enabling clinicians to monitor changes in membrane architecture following treatment.

These tools can detect markers that can be diagnostic for aggressive tumor phenotypes in live cells and tissues or serve as real-time reporters of therapeutic response (42).

4.1. Altered Lipid Metabolism and Membrane Composition

In addition to the changes in protein expression already discussed. cancer cells also exhibit widespread reprogramming of lipid metabolism, resulting in membrane compositions that favor high curvature. Oncogenic signaling induces enzymes like fatty acid synthase (FASN), acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC), and stearoyl-CoA desaturase (SCD1), which synthesize unsaturated and cone-shaped lipids. Cancer cells also upregulate phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) and phosphatidic acid (PA), which serve as docking platforms for curvature-sensing proteins and Ras signaling complexes. These lipid changes not only support vesicle formation and trafficking but also modulate membrane fluidity and stiffness. Moreover, the enrichment of lipid rafts with cholesterol and sphingolipids modifies membrane stiffness and fosters the formation of curved nanodomains that promote the clustering of Ras nanodomains and enhance signal transduction efficiency(43, 44).

4.2. Feedback with Oncogenic Pathways

Membrane curvature and oncogenic signaling are reciprocally regulated. Curved membrane regions support the spatial organization and clustering of signaling molecules such as Ras. The localization of H-ras, K-ras, and N-ras to membranes is governed by their lipid modifications and the curvature of the membrane environment. Recent findings demonstrate that positive membrane curvature facilitates the recruitment of Ras to the plasma membrane, especially during EMT triggered by TGFβ. Once localized, Ras activates a suite of downstream effectors—including RAF, PI3K/AKT, MAPK pathways, and RalGDS—that reinforce cellular transformation and metastasis. Thus, membrane curvature both influences and is influenced by oncogenic Ras signaling, forming a self-reinforcing loop that sustains malignancy(3, 4). For example, PI3K/AKT signaling enhances the production of curvature-prone lipids, while MAPK activation drives the expression of actin remodeling proteins that assist in membrane deformation(45, 46).

5. Therapeutic Targeting of Membrane Curvature in Cancer

Interdisciplinary collaboration between biophysicists, oncologists, nanotechnologists, and computational scientists will be essential to translate membrane curvature insights into patient benefit.

From a clinical perspective, membrane curvature offers a largely untapped area that can be utilized for diagnosis, prognosis, and therapy. Biomarkers based on curvature-sensing proteins or curvature-altered vesicle profiles may enable early detection and stratification of aggressive tumors. Furthermore, as curvature-targeting drugs and nanoparticles advance, clinical trials could usefully monitor curvature status using non-invasive imaging or circulating vesicle profiles as a measure of efficacy(27, 47).

5.1. Inhibitors of Curvature-Modulating Proteins

This section outlines current and emerging strategies for targeting curvature in cancer therapy.

Given its central role in regulating membrane dynamics, signaling compartmentalization, and cell motility, membrane curvature represents a promising but underexploited therapeutic frontier in oncology. Aberrant curvature machinery in cancer cells offers multiple intervention points—including curvature-generating proteins, lipid biosynthesis pathways, and curvature-dependent trafficking systems.

With regard to proteins, dynamin inhibitors, such as dynasore and Dyngo-4a, impair clathrin-mediated endocytosis by blocking vesicle scission. This reduces internalization of oncogenic receptors like EGFR, inhibiting downstream signaling through Ras/MAPK pathways. BAR domain proteins, which are overexpressed in many cancers, are also emerging targets. Small molecules and peptides that inhibit BAR domain dimerization or membrane association can disrupt invadopodia formation and metastasis. Dual-targeting strategies combining curvature-protein inhibitors with downstream pathway blockers (e.g., Rac1, Cdc42) may act synergistically to enhance therapeutic efficacy. Notably, targeting CIP4 and FBP17 suppresses metastatic behavior in breast and colon cancer models(48, 49).

5.2. Lipid Metabolism Modulators

Altering membrane lipid composition can modulate curvature and disrupt oncogenic signaling domains. Pharmacologic agents targeting lipid biosynthesis - such as FASN inhibitors (e.g., TVB-2640) and SCD1 inhibitors - reduce the abundance of unsaturated and cone-shaped lipids that support curvature formation. Statins interfere with cholesterol metabolism and lipid raft integrity, and impair Ras membrane anchoring. Farnesyltransferase inhibitors (FTIs) prevent Ras prenylation, thereby disrupting curvature-dependent signaling compartments(50, 51). These approaches offer indirect but potent opportunities to target membrane architecture in cancer.

5.3. Nanotechnology and Curvature-Responsive Drug Delivery

Nanotechnology provides a novel means of exploiting cancer-specific membrane curvature for targeted therapy. Because tumor cells exhibit elevated endocytic activity and altered lipid composition, they preferentially internalize nanoscale drug carriers such as liposomes, micelles, and dendrimers.

Curvature-responsive nanocarriers, including liposomes, micelles, and dendrimers, are preferentially internalized by tumor cells due to their elevated endocytic activity and unique lipid composition. Some nanoparticles are engineered to disassemble or release their drug cargo only in the presence of specific curvature or lipid environments. For instance, pH-sensitive liposomes coated with amphipathic peptides preferentially bind to curved tumor membranes and release drugs in acidic microenvironments(52).

Curvature-sensing peptides derived from BAR domains such as modified amphiphysin helices can also be used to guide therapeutic payloads directly to tumor-associated membrane structures such as invadopodia. Furthermore, CRISPR/Cas9-loaded nanoparticles, engineered to selectively disrupt genes encoding curvature-regulating proteins (e.g., CIP4, FCHo2), offer a functional genomics approach to suppress metastasis(53).

Emerging approaches also include sphingolipid analogs and PIP2 modulators, which alter membrane charge and curvature to disrupt oncogenic signaling hubs.

Pharmacologic agents that alter membrane lipid composition can indirectly affect curvature and vesicle behavior. Inhibitors of fatty acid synthase (FASN), such as TVB-2640, reduce the production of curvature-promoting unsaturated fatty acids and are currently in clinical trials for several solid tumors. Stearoyl-CoA desaturase (SCD) inhibitors have similar effects and may synergize with PI3K or Ras inhibitors to suppress signaling compartmentalization.

Similarly, statins, originally developed as cholesterol-lowering agents, have been shown to disrupt lipid raft integrity and impair Ras membrane association. Farnesyltransferase inhibitors (FTIs), which block Ras prenylation, further reduce its curvature-dependent membrane anchoring and are undergoing clinical reevaluation, particularly in combination with immunotherapies or MEK inhibitors(54, 55),

5.4. Diagnostic and Imaging Tools Targeting Curvature

Curvature-targeting diagnostics represent a new dimension in cancer imaging and therapy monitoring. Fluorescent biosensors based on BAR domains or lipid-binding motifs can visualize areas of high membrane curvature in live cells and tissues. These tools provide real-time readouts of membrane architecture and may help identify aggressive tumor phenotypes. Super-resolution microscopy techniques, such as STED and PALM, combined with curvature-specific probes, allow for subcellular resolution of membrane dynamics. These technologies could serve as both diagnostics and tools for evaluating therapeutic efficacy in clinical settings(56).

6. Challenges and Future Perspectives

6.1. Mechanistic Complexity and Redundancy

One major challenge is that the regulation of membrane curvature in cancer involves highly redundant and overlapping mechanisms. Multiple curvature-inducing proteins, such as BAR domain family members and dynamin-related proteins, can compensate for one another. Additionally, curvature is influenced by dynamic interplay between biochemical signals and mechanical forces, including those from the cytoskeleton and extracellular matrix, which further adds to its context-dependence. Similarly, lipids with distinct shapes can collectively maintain curvature dynamics even when specific lipid species are depleted. This redundancy obviously complicates therapeutic targeting(57).

6.2. Real-Time Measurement of Curvature in Living Systems

Accurately measuring membrane curvature in living systems remains another major challenge. Although super-resolution microscopy techniques like STED, PALM, and cryo-electron tomography have advanced our ability to visualize nanometer-scale curvature, their application in live or in vivo systems is still limited. Developing genetically encoded curvature biosensors and integrating them into advanced imaging platforms could allow real-time, high-resolution mapping of curvature changes in tumor environments(58, 59).

6.3. Application of Artificial Intelligence and Systems Biology

Machine learning and systems biology approaches are proving increasingly valuable for studying membrane curvature. AI-based image analysis can automatically quantify curvature features from high-resolution microscopy data, correlating them with cancer phenotypes or therapy responses. Integrating multi-omics datasets - such as lipidomics, proteomics, and transcriptomics - can uncover hidden regulatory networks that control curvature-related processes, revealing new targets for intervention(60).

Advanced live-cell imaging, optogenetics, and inducible protein-lipid relocalization tools will be essential for dissecting these relationships. Furthermore, computational modeling of curvature-associated signaling nodes may help predict how changes in membrane architecture affect cell fate decisions.

6.4. Organoid and Microfluidic Models for Drug Testing

Traditional 2D culture systems fail to replicate the curvature complexity of tumors in vivo. Organoids and microfluidic “tumor-on-a-chip” systems recreate more realistic curvature dynamics, matrix stiffness gradients, and fluidic conditions. These platforms are ideal for testing drugs that target curvature-modulating pathways or nanoparticles designed to exploit curvature-specific uptake (61).

Multi-omics integration—combining lipidomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and imaging data—could also reveal hidden networks that control curvature in cancer cells. These datasets can be analyzed using network inference algorithms to discover new drug targets or resistance mechanisms(62).

6.5. Translational Potential and Clinical Integration

Integrating curvature-focused diagnostics and therapeutics into clinical practice requires robust validation. Imaging tools and circulating vesicle biomarkers that reflect curvature changes could complement existing diagnostic modalities. Moreover, curvature-targeting nanomedicines should be evaluated in patient-derived xenografts and organoid models to ensure efficacy and specificity before clinical translation (63).

7. Cancer Types Most Influenced by Membrane Curvature

The role of membrane curvature is particularly pronounced in cancers with high invasive and metastatic potential. In breast cancer, the formation of invadopodia and the epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) are strongly curvature-dependent, involving BAR domain proteins⁵ and actin remodeling. TGFβ signaling—shown to induce curvature and Ras relocalization—is a key driver of EMT and metastasis in breast tumors (3). Glioblastoma displays aggressive infiltration supported by upregulation of curvature-sensitive proteins, facilitating enhanced migration through brain tissue. Pancreatic cancer, dominated by KRAS mutations, relies on curvature-mediated Ras localization and activation, making membrane dynamics central to its oncogenic signaling. Colorectal cancer features altered lipid metabolism and dysregulated Wnt signaling, both of which are closely tied to curvature mechanisms. In prostate cancer, curvature is linked to increased exosome secretion and metastatic niche formation. These cancers exemplify how biophysical membrane properties integrate with oncogenic pathways to drive progression, invasion, and therapy resistance (64, 65).

In conclusion, curvature is more than geometry—it is biology in motion. Embracing its complexity may open new doors in the quest to understand and overcome cancer. However, in order to exploit the opportunities in this area, future research must integrate emerging tools in lipidomics, AI-assisted image analysis, organoid modeling, and CRISPR-based functional screening to build a holistic, real-time map of curvature dynamics in cancer. As interdisciplinary collaboration accelerates, membrane curvature is poised to become a cornerstone of next-generation cancer diagnostics and therapeutics.

8. Emerging Tools and Technologies for Studying Membrane Curvature

Advancements in imaging and biophysical technologies have transformed the study of membrane curvature in cancer. Super-resolution microscopy techniques such as STED and PALM enable nanometer-scale visualization of curved membrane domains in live cells. Cryo-electron tomography provides three-dimensional ultrastructural insights into organelle morphology and membrane deformation. Genetically encoded biosensors that detect curvature in real time are being developed and deployed in both in vitro and in vivo systems. These tools are increasingly integrated with omics technologies—including lipidomics, transcriptomics, and proteomics—to build comprehensive models of curvature regulation. Furthermore, organoid models and microfluidic systems provide physiologically relevant platforms for testing how drugs and genetic interventions influence membrane curvature. Together, these technologies offer unprecedented insight into the spatiotemporal dynamics of curvature and their implications in cancer biology.

Recent advancements in biophysical and imaging technologies have enabled more precise investigation into the role of membrane curvature in cancer. Super-resolution microscopy, including techniques like STED and PALM, has made it possible to visualize nanometer-scale membrane changes in live cells. Cryo-electron tomography provides three-dimensional views of organelle morphology at near-native states, crucial for understanding how curvature affects intracellular organization. Furthermore, the development of curvature-sensitive probes and biosensors allows researchers to monitor curvature dynamics in real time within complex tissue environments. Integrating these tools with omics technologies—such as lipidomics and proteomics—offers a systems-level view of curvature regulation. Organoid models and microfluidic systems also provide physiologically relevant platforms for testing curvature-modulating drugs. These tools are poised to revolutionize our understanding of membrane curvature and open new avenues for diagnostics and therapeutics (66, 67).

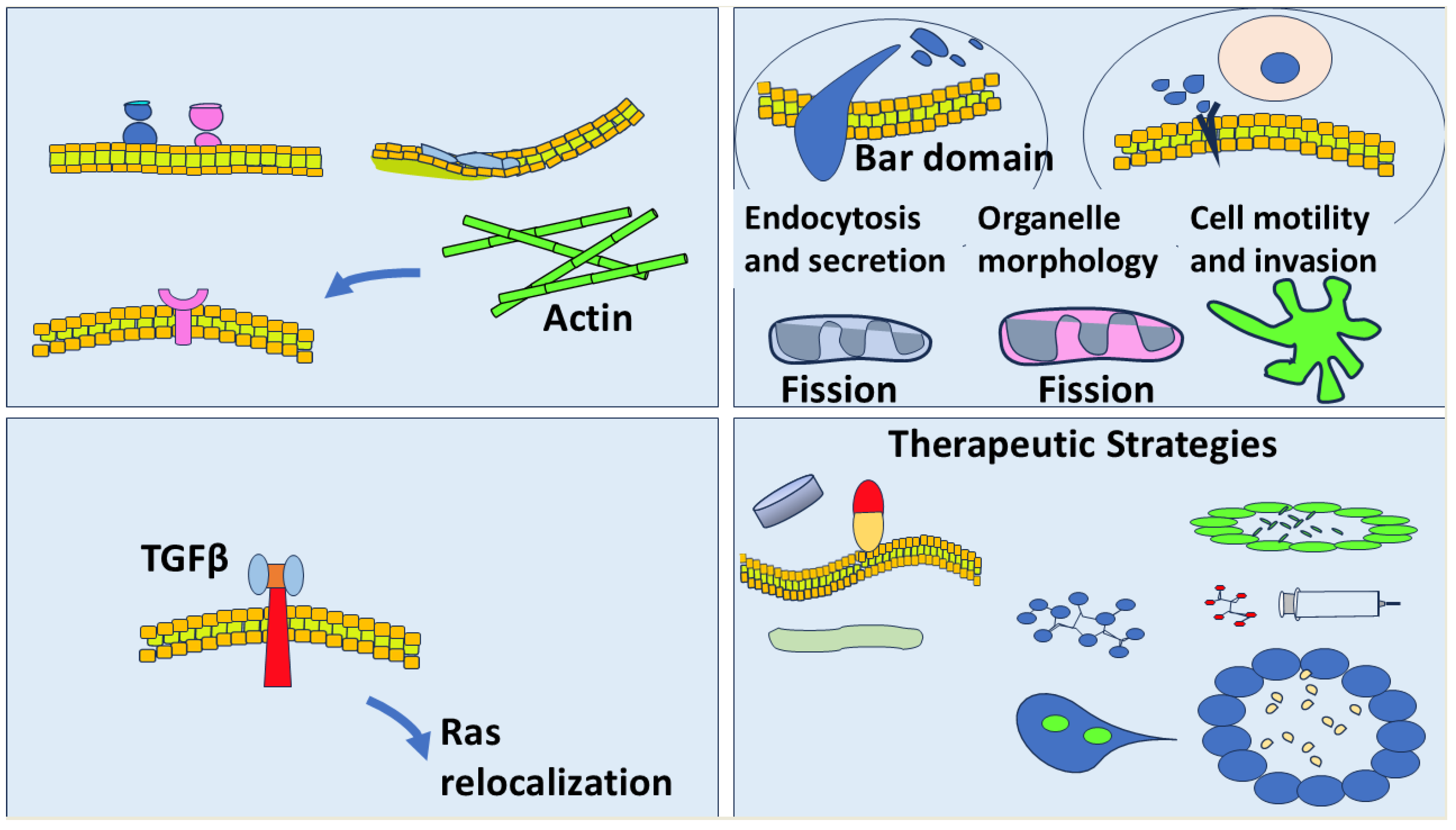

Figure 1.

Membrane Curvature and Cancer: Mechanisms, Implications, and Therapeutic Perspectives. This schematic illustrates the relationship between membrane curvature and cancer biology. Top left: Membrane curvature can be generated through alterations in lipid composition and asymmetry, curvature-sensing and -generating proteins, and cytoskeletal contributions such as actin dynamics. Top right: In cancer cells, membrane curvature influences critical functions including endocytosis, secretion, organelle morphology, mitochondrial and endosomal fission, and cell motility and invasion. Bottom left: TGFβ signaling induces membrane curvature and Ras relocalization, linking extracellular cues to intracellular oncogenic pathways. Bottom right: Therapeutic strategies include targeting curvature-inducing proteins, modulating lipid metabolism, and utilizing nanoparticle-based drug delivery systems to exploit membrane curvature for improved cancer treatment.

Figure 1.

Membrane Curvature and Cancer: Mechanisms, Implications, and Therapeutic Perspectives. This schematic illustrates the relationship between membrane curvature and cancer biology. Top left: Membrane curvature can be generated through alterations in lipid composition and asymmetry, curvature-sensing and -generating proteins, and cytoskeletal contributions such as actin dynamics. Top right: In cancer cells, membrane curvature influences critical functions including endocytosis, secretion, organelle morphology, mitochondrial and endosomal fission, and cell motility and invasion. Bottom left: TGFβ signaling induces membrane curvature and Ras relocalization, linking extracellular cues to intracellular oncogenic pathways. Bottom right: Therapeutic strategies include targeting curvature-inducing proteins, modulating lipid metabolism, and utilizing nanoparticle-based drug delivery systems to exploit membrane curvature for improved cancer treatment.

9. Conclusion

The integration of membrane curvature into the framework of cancer biology represents a paradigm shift in how we understand cellular transformation, invasion, and therapy resistance. By connecting mechanical properties of the membrane to molecular signaling networks, researchers can uncover new layers of oncogenic regulation that have previously gone unnoticed. As our tools for probing and manipulating membrane curvature become more sophisticated, the field is likely to uncover novel biomarkers, drug targets, and therapeutic strategies. Importantly, membrane curvature intersects with key biological systems beyond cancer, including neurodegeneration and immune signaling, indicating broad relevance. Interdisciplinary collaboration across cell biology, physics, engineering, and clinical oncology will be essential to realize the full therapeutic potential of targeting membrane curvature.

Author Contributions

Alexandros Damalas conceptualized the review and wrote the original manuscript draft. Varvara Trachana critically reviewed and edited the manuscript and served as the corresponding author. Ioannis D. Kyriazis critically reviewed the manuscript for important intellectual content. Charalampos Angelidis prepared the figures and critically reviewed the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the final version for submission.

References

- Simunovic, M; Evergren, E; Callan-Jones, A; Bassereau, P. Curving Cells Inside and Out: Roles of BAR Domain Proteins in Membrane Shaping and Its Cellular Implications. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2019, 35, 111–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuburich, NA; Sabapathy, T; Demestichas, BR; Maddela, JJ; den Hollander, P; Mani, SA. Proactive and reactive roles of TGF-beta in cancer. Semin Cancer Biol. 2023, 95, 120–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Damalas, A; Vonkova, I; Tutkus, M; Stamou, D. TGFbeta-induced changes in membrane curvature influence Ras oncoprotein membrane localization. Scientific reports 2022, 12, 13486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, H; Mu, H; Jean-Francois, F; Lakshman, B; Sarkar-Banerjee, S; Zhuang, Y; et al. Membrane curvature sensing of the lipid-anchored K-Ras small GTPase. Life Sci Alliance 2019, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y; Hancock, JF. RAS nanoclusters are cell surface transducers that convert extracellular stimuli to intracellular signalling. FEBS Lett. 2023, 597, 892–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klausner, RD; Donaldson, JG; Lippincott-Schwartz, J. Brefeldin A: insights into the control of membrane traffic and organelle structure. J Cell Biol. 1992, 116, 1071–1080. [Google Scholar]

- Campelo, F; McMahon, HT; Kozlov, MM. The hydrophobic insertion mechanism of membrane curvature generation by proteins. Biophys J. 2008, 95, 2325–2339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mim, C; Unger, VM. Membrane curvature and its generation by BAR proteins. Trends Biochem Sci. 2012, 37, 526–533. [Google Scholar]

- Mayor, S; Pagano, RE. Pathways of clathrin-independent endocytosis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007, 8, 603–612. [Google Scholar]

- McMahon, HT; Gallop, JL. Membrane curvature and mechanisms of dynamic cell membrane remodelling. Nature 2005, 438, 590–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parton, RG; Simons, K. The multiple faces of caveolae. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007, 8, 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, CR; Schulze, A. Lipid metabolism in cancer. FEBS J. 2012, 279, 2610–2623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y; Wong, CO; Cho, KJ; van der Hoeven, D; Liang, H; Thakur, DP; et al. SIGNAL TRANSDUCTION. Membrane potential modulates plasma membrane phospholipid dynamics and K-Ras signaling. Science 2015, 349, 873–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dasgupta, I; McCollum, D. Control of cellular responses to mechanical cues through YAP/TAZ regulation. The Journal of biological chemistry 2019, 294, 17693–17706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sundborger, AC; Hinshaw, JE. Dynamins and BAR Proteins-Safeguards against Cancer. Crit Rev Oncog. 2015, 20, 475–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mim, C; Cui, H; Gawronski-Salerno, JA; Frost, A; Lyman, E; Voth, GA; et al. Structural basis of membrane bending by the N-BAR protein endophilin. Cell. 2012, 149, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dharan, R; Barnoy, A; Tsaturyan, AK; Grossman, A; Goren, S; Yosibash, I; et al. Intracellular pressure controls the propagation of tension in crumpled cell membranes. Nat Commun. 2025, 16, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akamatsu, M; Vasan, R; Serwas, D; Ferrin, MA; Rangamani, P; Drubin, DG. Principles of self-organization and load adaptation by the actin cytoskeleton during clathrin-mediated endocytosis. Elife 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djakbarova, U; Madraki, Y; Chan, ET; Kural, C. Dynamic interplay between cell membrane tension and clathrin-mediated endocytosis. Biol Cell. 2021, 113, 344–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C; Chen, Y; Chen, S; Hu, L; Wang, J; Wang, Y. Pan-cancer analysis of Arp2/3 complex subunits: focusing on ARPC1A’s role and validating the ARPC1A/c-Myc axis in non-small cell lung cancer. Front Immunol. 2024, 15, 1491910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kar, J; Kar, S; Gupta, A; Jana, SS. Assembly and disassembly dynamics of nonmuscle myosin II control endosomal fission. Cell reports 2023, 42, 112108. [Google Scholar]

- Goode, BL; Eskin, J; Shekhar, S. Mechanisms of actin disassembly and turnover. J Cell Biol. 2023, 222. [Google Scholar]

- Liese, S; Carlson, A. Membrane shape remodeling by protein crowding. Biophys J. 2021, 120, 2482–2489. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mondal, S; Baumgart, T. Membrane reshaping by protein condensates. Biochim Biophys Acta Biomembr. 2023, 1865, 184121. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sun, X; Yegambaram, M; Lu, Q; Garcia Flores, AE; Pokharel, MD; Soto, J; et al. Mitochondrial fission produces a Warburg effect via the oxidative inhibition of prolyl hydroxylase domain-2. Redox Biol. 2025, 81, 103529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doyle, CP; Timple, L; Hammond, GRV. OSBP is a Major Determinant of Golgi Phosphatidylinositol 4-Phosphate Homeostasis. Contact (Thousand Oaks) 2024, 7, 25152564241232196. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, P; Zhang, H; Qin, Y; Xiong, H; Shi, C; Zhou, Z. Membrane Proteins and Membrane Curvature: Mutual Interactions and a Perspective on Disease Treatments. Biomolecules 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okada, AK; Teranishi, K; Ambroso, MR; Isas, JM; Vazquez-Sarandeses, E; Lee, JY; et al. Lysine acetylation regulates the interaction between proteins and membranes. Nat Commun. 2021, 12, 6466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapmaz, A; Erson-Bensan, AE. EGFR endocytosis: more than meets the eye. Oncotarget 2023, 14, 297–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imbastari, F; Dahlmann, M; Sporbert, A; Mattioli, CC; Mari, T; Scholz, F; et al. MACC1 regulates clathrin-mediated endocytosis and receptor recycling of transferrin receptor and EGFR in colorectal cancer. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2021, 78, 3525–3542. [Google Scholar]

- O’Sullivan, MJ; Lindsay, AJ. The Endosomal Recycling Pathway-At the Crossroads of the Cell. Int J Mol Sci. 2020, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sugiyama, MG; Fairn, GD; Antonescu, CN. Akt-ing Up Just About Everywhere: Compartment-Specific Akt Activation and Function in Receptor Tyrosine Kinase Signaling. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2019, 7, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, J. Distinct functions of dynamin isoforms in tumorigenesis and their potential as therapeutic targets in cancer. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 41701–41716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Truesdell, P; Ahn, J; Chander, H; Meens, J; Watt, K; Yang, X; et al. CIP4 promotes lung adenocarcinoma metastasis and is associated with poor prognosis. Oncogene 2015, 34, 3527–3535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J; Mukhopadhyay, A; Truesdell, P; Chander, H; Mukhopadhyay, UK; Mak, AS; et al. Cdc42-interacting protein 4 is a Src substrate that regulates invadopodia and invasiveness of breast tumors by promoting MT1-MMP endocytosis. J Cell Sci. 2011, 124, 1739–1751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurung, S; Perocheau, D; Touramanidou, L; Baruteau, J. The exosome journey: from biogenesis to uptake and intracellular signalling. Cell Commun Signal. 2021, 19, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y; Gorfe, AA; Hancock, JF. RAS Nanoclusters Selectively Sort Distinct Lipid Headgroups and Acyl Chains. Front Mol Biosci. 2021, 8, 686338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patat, J; Schauer, K; Lachuer, H. Trafficking in cancer: from gene deregulation to altered organelles and emerging biophysical properties. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2024, 12, 1491304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, NV; Desjardins, A; Leclerc, N. Tau secretion is correlated to an increase of Golgi dynamics. PLoS One 2017, 12, e0178288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephens, DC; Harris, DA. Organizing ‘Elements’: Facilitating Exocytosis and Promoting Metastasis. Trends Cancer 2020, 6, 273–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsujita, K; Satow, R; Asada, S; Nakamura, Y; Arnes, L; Sako, K; et al. Homeostatic membrane tension constrains cancer cell dissemination by counteracting BAR protein assembly. Nat Commun. 2021, 12, 5930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matthaeus, C; Sochacki, KA; Dickey, AM; Puchkov, D; Haucke, V; Lehmann, M; et al. The molecular organization of differentially curved caveolae indicates bendable structural units at the plasma membrane. Nat Commun. 2022, 13, 7234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beloribi-Djefaflia, S; Vasseur, S; Guillaumond, F. Lipid metabolic reprogramming in cancer cells. Oncogenesis 2016, 5, e189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chavan, TS; Muratcioglu, S; Marszalek, R; Jang, H; Keskin, O; Gursoy, A; et al. Plasma membrane regulates Ras signaling networks. Cell Logist. 2015, 5, e1136374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campa, CC; Martini, M; De Santis, MC; Hirsch, E. How PI3K-derived lipids control cell division. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2015, 3, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogucka-Janczi, K; Harms, G; Coissieux, MM; Bentires-Alj, M; Thiede, B; Rajalingam, K. ERK3/MAPK6 dictates CDC42/RAC1 activity and ARP2/3-dependent actin polymerization. Elife 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francia, V; Reker-Smit, C; Salvati, A. Mechanisms of Uptake and Membrane Curvature Generation for the Internalization of Silica Nanoparticles by Cells. Nano Lett. 2022, 22, 3118–3124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garvalov, BK; Foss, F; Henze, AT; Bethani, I; Graf-Hochst, S; Singh, D; et al. PHD3 regulates EGFR internalization and signalling in tumours. Nat Commun. 2014, 5, 5577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suman, P; Mishra, S; Chander, H. High expression of FBP17 in invasive breast cancer cells promotes invadopodia formation. Med Oncol. 2018, 35, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsushita, Y; Nakagawa, H; Koike, K. Lipid Metabolism in Oncology: Why It Matters, How to Research, and How to Treat. In Cancers (Basel); 2021; Volume 13. [Google Scholar]

- Vona, R; Iessi, E; Matarrese, P. Role of Cholesterol and Lipid Rafts in Cancer Signaling: A Promising Therapeutic Opportunity? Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021, 9, 622908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, MB; Bhatia, VK; Jao, CC; Rasmussen, JE; Pedersen, SL; Jensen, KJ; et al. Membrane curvature sensing by amphipathic helices: a single liposome study using alpha-synuclein and annexin B12. The Journal of biological chemistry 2011, 286, 42603–42614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masarwy, R; Breier, D; Stotsky-Oterin, L; Ad-El, N; Qassem, S; Naidu, GS; et al. Targeted CRISPR/Cas9 Lipid Nanoparticles Elicits Therapeutic Genome Editing in Head and Neck Cancer. Adv Sci (Weinh) 2025, 12, e2411032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falchook, G; Infante, J; Arkenau, HT; Patel, MR; Dean, E; Borazanci, E; et al. First-in-human study of the safety, pharmacokinetics, and pharmacodynamics of first-in-class fatty acid synthase inhibitor TVB-2640 alone and with a taxane in advanced tumors. EClinicalMedicine 2021, 34, 100797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karthikeyan, S; Somasundaram, P; Karimi, I; Lagunas-Rangel, FA; Alsehli, AM; Fredriksson, R; et al. Statin drugs and lipid modulation: Mechanistic basis considering lipid rafts, kinase signaling, myopathy, and cancer. Pharmacol Res. 2025, 220, 107912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maib, H; Adarska, P; Hunton, R; Vines, JH; Strutt, D; Bottanelli, F; et al. Recombinant biosensors for multiplex and super-resolution imaging of phosphoinositides. J Cell Biol. 2024, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatraman, K; Lee, CT; Budin, I. Setting the curve: the biophysical properties of lipids in mitochondrial form and function. J Lipid Res. 2024, 65, 100643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komikawa, T; Okochi, M; Tanaka, M. Exploration and analytical techniques for membrane curvature-sensing proteins in bacteria. J Bacteriol. 2025, 207, e0048224. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, JH; Herlo, R; Rombach, J; Larsen, AH; Stoklund, M; Perslev, M; et al. Membrane curvature association of amphipathic helix 8 drives constitutive endocytosis of GPCRs. Sci Adv. 2025, 11, eadv1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboy-Pardal, MCM; Jimenez-Carretero, D; Terres-Dominguez, S; Pavon, DM; Sotodosos-Alonso, L; Jimenez-Jimenez, V; et al. A deep learning-based tool for the automated detection and analysis of caveolae in transmission electron microscopy images. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 2023, 21, 224–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, MR; Barata, D; Teixeira, LM; Giselbrecht, S; Reis, RL; Oliveira, JM; et al. Colorectal tumor-on-a-chip system: A 3D tool for precision onco-nanomedicine. Sci Adv. 2019, 5, eaaw1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denti, V; Capitoli, G; Piga, I; Clerici, F; Pagani, L; Criscuolo, L; et al. Spatial Multiomics of Lipids, N-Glycans, and Tryptic Peptides on a Single FFPE Tissue Section. J Proteome Res. 2022, 21, 2798–2809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spitzberg, JD; Ferguson, S; Yang, KS; Peterson, HM; Carlson, JCT; Weissleder, R. Multiplexed analysis of EV reveals specific biomarker composition with diagnostic impact. Nat Commun. 2023, 14, 1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelson, CO; Tessmann, JW; Geisen, ME; He, D; Wang, C; Gao, T; et al. Upregulation of Fatty Acid Synthase Increases Activity of beta-Catenin and Expression of NOTUM to Enhance Stem-like Properties of Colorectal Cancer Cells. Cells 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelson, CO; Zaytseva, YY. Altered lipid metabolism in APC-driven colorectal cancer: the potential for therapeutic intervention. Front Oncol. 2024, 14, 1343061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, WW; Michalak, DJ; Sochacki, KA; Kunamaneni, P; Alfonzo-Mendez, MA; Arnold, AM; et al. Cryo-electron tomography pipeline for plasma membranes. Nat Commun. 2025, 16, 855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zulueta Diaz, YLM; Arnspang, EC. Super-resolution microscopy to study membrane nanodomains and transport mechanisms in the plasma membrane. Front Mol Biosci. 2024, 11, 1455153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).