1. Introduction

Childhood and adolescence constitute critical stages for the acquisition and consolidation of cognitive, socioemotional, and behavioral skills that shape human development (Noble et al. 2015; Olhaberry & Sieverson, 2022). During this period, multiple internal factors—such as personality, self-esteem, or resilience—and external factors of social, family or school origin (Barraca & Artola González, 2006; Förster & López, 2022) can influence developmental trajectories. These factors, individually or combined, may affect the development of Executive Functions (EF), a set of higher-order cognitive processes essential for self-regulation and adaptive adjustment (Diamond, 2013).

Executive Functions encompass skills that support self-control, decision-making, and adaptation to changing environments (Friedman & Robbins, 2022). The classical model proposed by Miyake et al. (2000) describes EF as three interrelated components: Inhibition, which regulates automatic responses; Working Memory, responsible for temporarily storing and updating relevant information; and Cognitive Flexibility, which enables adaptation to novelty or change. Diamond (2020) highlights their relevance for social competence and adjustment, noting that EF predicts scholastic, social, and psychological success even more strongly than intelligence or socioeconomic level. In line with this, recent studies show that better executive performance predicts higher social cognition skills (Schulte et al., 2022; Williams et al., 2023), even above emotional comprehension alone (Wang & Feng, 2024), while EF deficits are consistently associated with social behavior difficulties (Holl et al., 2021; Otsuka et al., 2021; Pineda-Alhucema et al., 2018; Yeh et al., 2017).

Evidence shows that early exposure to adverse experiences such as abandonment, violence, or parental neglect may compromise these executive processes, resulting in difficulties in behavioral regulation and increasing vulnerability to maladaptive outcomes (Erazo Santander, 2022; Johnson et al., 2021). Children and adolescents living in psychosocially vulnerable contexts tend to present a higher perception of maladjustment, expressed as difficulties in socialization, school performance, and personal functioning (Carrera et al., 2019; Wade et al., 2019). These situations frequently coexist with lower executive performance compared with peers in more normative environments (Aguilar-González et al., 2025; Camuñas et al., 2022; Johnson et al., 2021). A recent meta-analysis confirms that Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) are consistently associated with deficits in Working Memory, Inhibitory control, and Cognitive Flexibility (Rahapsari & Levita, 2024). Studies conducted in the last decade further indicate that exposure to adversity compromises skills necessary for academic success and social adaptation, including planning, self-control, and working memory, and can alter neurocognitive development and functioning in brain networks related to regulation (McLaughlin et al., 2019; McLaughlin, Sheridan & Lambert, 2014). The impact of adversity, however, is not uniform; children’s perception of stressful experiences modulates outcomes, and negative effects emerge mainly when events are interpreted as threatening (Smith & Pollak, 2021), although this does not apply equally across all adverse contexts (McLaughlin et al., 2021). Danese and Widom (2024) also suggest that executive functioning plays a moderating role, as children with significant cognitive deficits present more difficulties in processing adverse situations than those with preserved EF.

Given the strong link between EF, adaptation, and academic and social success, interventions aimed at strengthening EF have grown in relevance within educational and psychosocial fields (e.g., Vaíllo & Camuñas, 2015). EF interventions have encompassed a wide spectrum of methods such as digital and traditional cognitive training, neurofeedback, school-based programs, physical-activity interventions, mindfulness practices, and various other approaches (e.g., drama-based curricula or Experience Corps) (Diamond & Ling 2019). One of the largest systematic reviews of EF interventions shows that movement-based mindfulness practices and some school programs provide the strongest EF gains, outperforming both computerized and non-computerized cognitive training. Computerized programs such as Cogmed or BrainGame Brian aim to enhance executive functions by training specific components, but improvements largely remain confined to the practiced tasks, with minimal transfer to other skills or real-world contexts (Aksayli et al., 2019; Melby-Lervåg and Hulme, 2013; Shipstead et al., 2012; Takacs & Kassai, 2019). Meta-analytic evidence shows short-term gains in verbal and visuospatial working memory—especially for children with learning disorders—yet no effects on inhibition, limited long-term maintenance, and limited to task-specific learning (Takacs & Kassai, 2019). These explicit training programs based on repeated practice of executive-function tasks produced markedly smaller effects in atypically developing groups than in typically developing children. Conversely, interventions that teach children new self-regulation strategies appear to be more effective for nontypically developing groups than for their typically developing peers. A proposed explanation is that explicit practice requires a baseline level of executive functioning and sustained attention that these children may not yet possess, whereas strategy-based approaches offer more accessible and beneficial routes for improvement.

In this sense, to overcome the limited transfer to other skills observed in traditional EF training, new approaches combine cognitive training and metacognitive strategies. The so-called strategy-based training has shown promising results both in typically developing children and in those living in vulnerable environments (Cáceres-González et al., 2025; Graziano & Hart, 2016; Jones et al., 2020; Kubota et al., 2023; Partanen et al., 2015; Pozuelos et al., 2018; Rossignoli-Palomeque et al., 2020). This method seeks to promote more generalizable learning by engaging children in monitoring and regulating their own cognitive processes. Evidence shows that metacognitive strategies enhance EF engagement and development, are particularly helpful for individuals with lower EF levels, and support self-regulated learning (Cáceres-González et al., 2025). Given these links, strategy-based training offers a promising route for achieving far transfer beyond the tasks directly practiced.

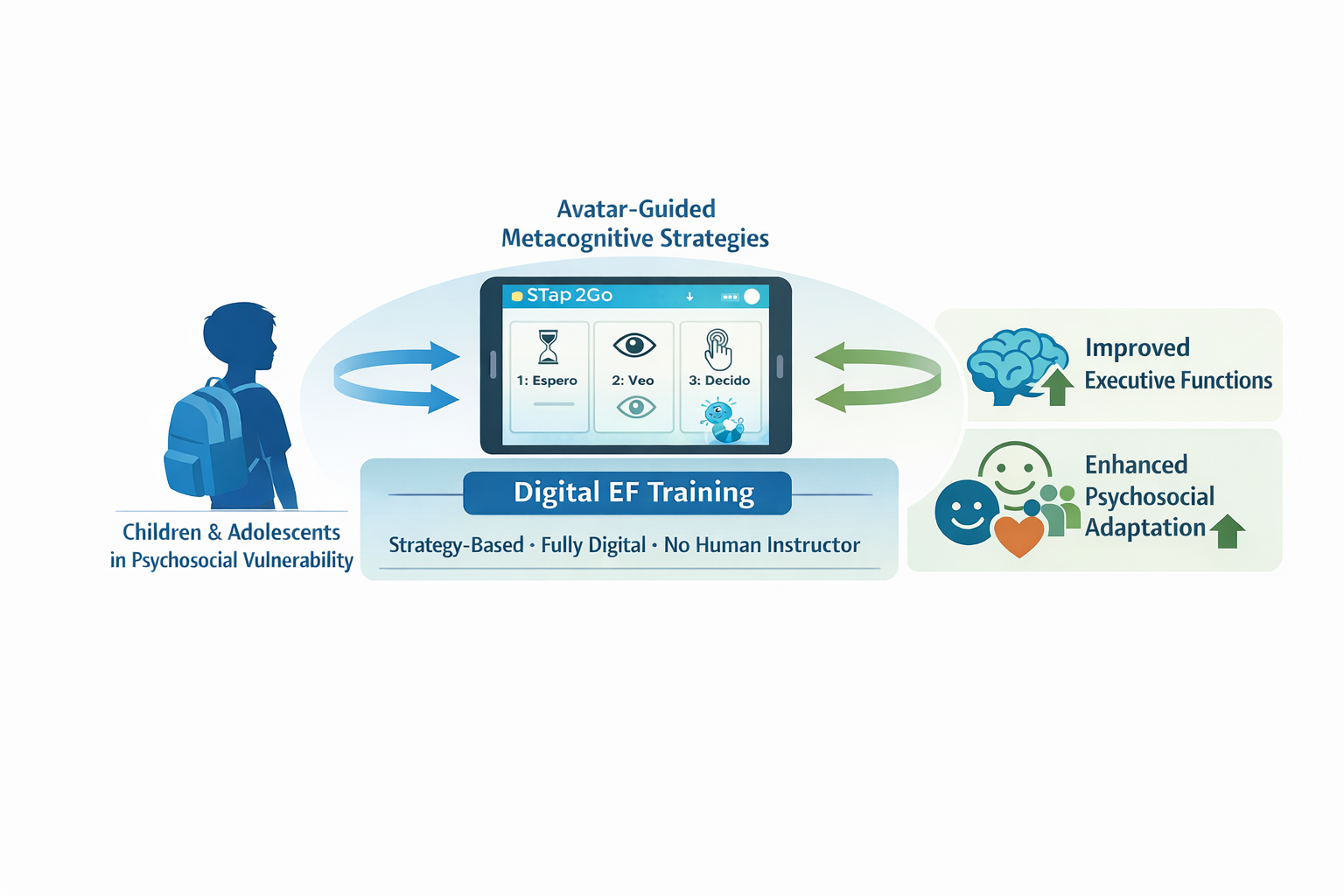

However, a limitation of strategy-based interventions is their reliance on trained instructors, as effective scaffolding requires specialized preparation and depends heavily on instructor expertise. Consequently, most of the existing implementations have not been fully digital: most studies involved adults guiding or supervising children’s use of metacognitive strategies, or supplementing computer activities with metacognitive workbooks (Graziano & Hart, 2016; Jones et al., 2020; Kubota et al., 2023; Partanen et al., 2015; Pozuelos et al., 2018). In this context, STap2Go is the first fully digital, strategy-based EF intervention that eliminates the need for a human instructor by embedding scaffolding into an automated decision tree (Cáceres-González et al., 2025). Its metacognitive prompts target planning, monitoring, and evaluating one’s performance. The first empirical results using this digital intervention are encouraging. The intervention not only improved EFs and processing speed, but also broader outcomes such as IQ, metacognition, academic achievement, and behavioral and emotional regulation. Importantly, children at psychosocial risk benefited the most from the program, suggesting that this intervention constitutes a valuable and affordable resource for supporting children in vulnerable environments and mitigating the impact of risk factors on academic and social adaptation (Cáceres-González et al., 2025).

In this context, the present study seeks to further examine the impact of a fully digital, strategy-based EF intervention in children and adolescents living in vulnerable contexts. Specifically, we were interested not only in EF outcomes but also in self-perceived maladjustment, which—while a relevant variable underlying difficulties in socialization, school performance, and personal functioning—has not been previously considered (Cáceres-González et al., 2025).

2. Method

2.1. Participants

Seventy-three children and adolescents with active cases in Welfare Services due to their situation of social exclusion participated in the study. These individuals were referred to a socio-educational program aimed at reducing risk factors for social exclusion. Sample selection followed a non-probabilistic purposive sampling strategy, as participants were required to meet specific inclusion criteria (having an active file in Social Services due to risk of social exclusion, attendance greater than 80%, provision of informed consent and assent) and exclusion criteria (selective mutism, low-functioning autism, a curricular gap greater than four years).

During the intervention, attrition occurred for five participants in the experimental group and two in the control group. In all cases, withdrawal was due to family-related difficulties that prevented continued participation in both the training and the broader socio-educational program.

From the total remaining sample of 68 children (38 males), simple randomization was used to allocate 36 participants (52.94%) to the Intervention group and 32 (47.06%) to the Control group, ensuring equal probability of assignment. Participants in the training group ranged in age from 8 to 15 years (M = 12.03, SD = 1.90), while those in the control group ranged from 8 to 17 years (M = 12.56, SD = 2.34). Written consent was provided in all cases, in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

2.2. Assessment

EF and self-perceived adjustment were assessed before and after the intervention using the following instruments:

General Maladjustment: The Multifactorial Self-Evaluative Test for Child Adaptation (TAMAI; Hernández-Guanir, 2015) is a questionnaire composed of 170 dichotomous items (true/false) that assesses a global dimension (General Maladjustment) and several subdimensions. Personal Maladjustment (PM) evaluates self-esteem, insecurity, and emotional functioning. Social Maladjustment (SM) captures perceived difficulties in peer relationships and adherence to social norms. Scholastic Maladjustment (ScM) reflects perceptions of motivation, diligence, and attitudes toward authority and school. Family Maladjustment (FM) assesses perceptions of parental educational styles, including perfectionism and emotional communication. The Discrepancy (DIS) scale indicates the degree of consistency between parental educational styles. Two control indices are included: Pro-Image (social desirability) and Contradictions (response consistency). On the maladjustment scales, higher scores indicate better adaptation. The instrument demonstrates very high reliability (Cronbach’s α = .92) (Hernández-Guanir, 2015).

Executive Functions: The Neuropsychological Assessment Battery of Executive Functions (BANFE-3; Flores et al., 2020) comprises fifteen performance-based tests grouped into four domains. The Orbitofrontal (OF) index assesses emotion regulation, behavioral control, inhibitory control, rule-following, and risk–benefit evaluation. The Dorsolateral (DL) index measures verbal fluency, cognitive flexibility, planning, sequencing, and working memory (visual, verbal, visuospatial). The Anterior Prefrontal (AP) index evaluates metamemory, figurative-language comprehension, and abstract reasoning. A Global Executive Function score is also provided. Higher scores indicate better performance. Reliability is high (Cronbach’s α = .80) (Flores et al., 2020).

2.3. Intervention

The experimental group received the STap2Go intervention approximately over 12 weeks (STap2Go, 2022), completing three 15-minute sessions per week. The training was performed in a tablet with Android operating system on which the application was installed. Training was carried out in the early afternoon, during the first 15 minutes of activity, three times per week, on alternate days.

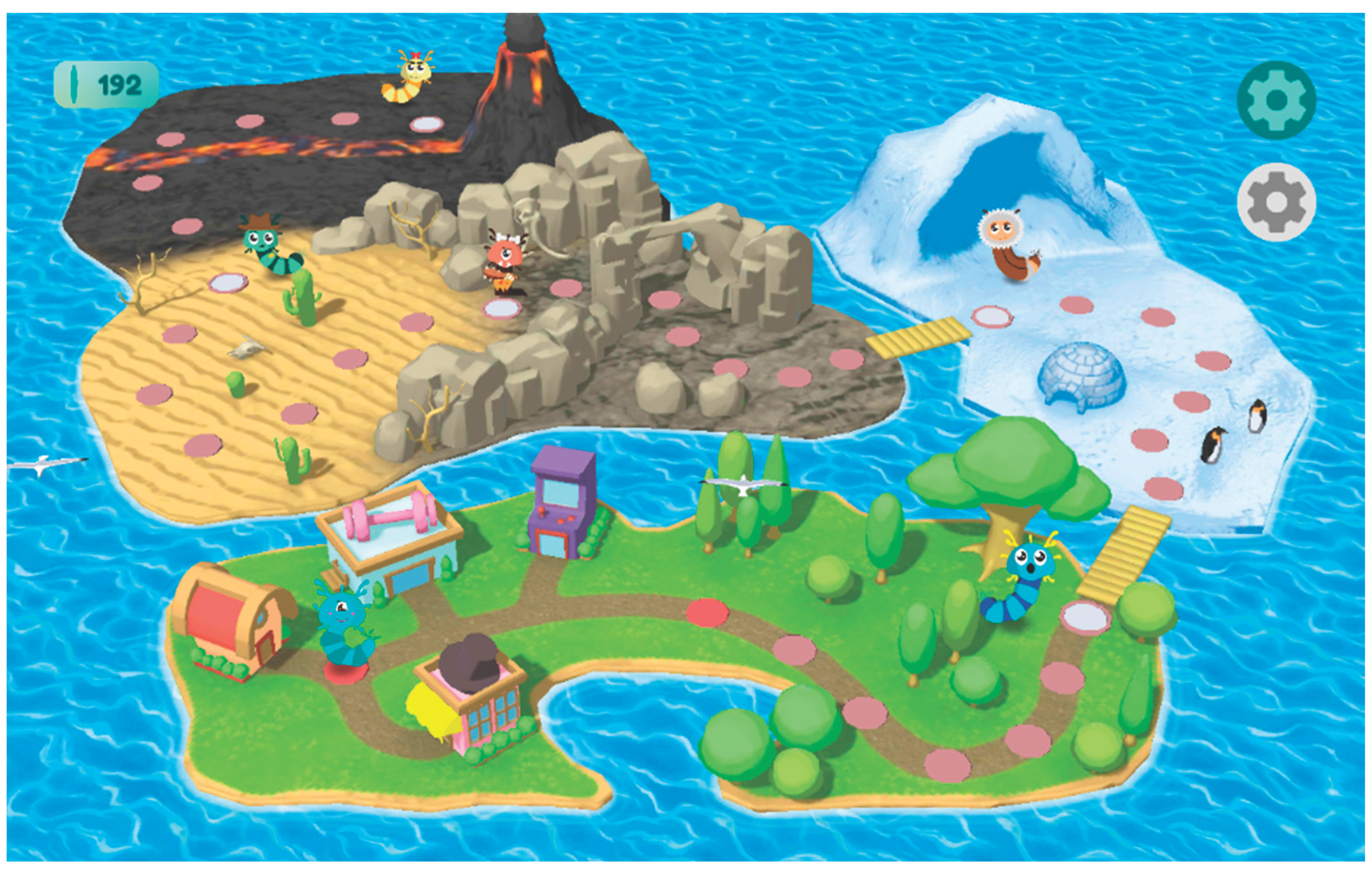

STap2Go is structured as a gamified digital environment in which participants progress through a sequence of fixed sessions represented as nodes on a map (

Figure 1). Each session consisted of three exercises (two repetitions each), drawn from go/no-go, stop-signal, N-back, and task-switching paradigms. A total of 100 exercises were completed across the intervention. Task difficulty increased progressively through adjustments in parameters such as distractors, N-back load, and switching frequency. Participants received immediate feedback on each trial, and task stimuli were displayed for 1,000–1,500 ms with a 500-ms response window. Crucially, the program integrates automated metacognitive scaffolding through a pre-designed decision tree. Before, during, and after each task, the system prompts users to clarify instructions, apply self-instructions, regulate their performance, and reflect on errors—strategies grounded in Efklides’s (2009) framework and validated in previous work (Rossignoli-Palomeque et al., 2019). The system also adapts error-specific prompts to guide self-correction. Performance yields points that can be used for avatar customization, although ancillary game features were disabled in this study.

2.4. Procedure

Prior to obtaining authorization from the Socio-Educational Center, families were informed about the purpose of the training. Informed consent was then obtained, outlining the aims of the assessment (pretest–posttest), the nature and potential benefits of the training, and the principle of non-maleficence, along with a commitment to provide families with feedback on each participant’s results. Before the intervention, standardized assessments of EF (BANFE-3) and self-perceived maladjustment (TAMAI) were administered. The training group then completed 34 training sessions of 15 minutes each, scheduled on alternating training and rest days and supervised by the educational team, over an approximate period of three months. After completing the intervention, the training group was reassessed using the same instruments and procedures. The control group did not receive training; instead, they underwent a second assessment after a three-month interval matching the duration of the intervention and continued to receive the usual services provided by the Socio-Educational Center. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Nebrija University, and participant confidentiality was ensured throughout the process.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

A quasi-experimental longitudinal design with repeated measures was employed, consisting of an experimental group and an equivalent control group. Group effects and within-group changes over Time were examined using mixed 2×2 ANOVAs on the global scores derived from the TAMAI subscales and the BANFE-3 indices. All statistical analyses were conducted using jamovi (The jamovi project, 2025; version 2.7.6.0).

3. Results

Descriptive results are shown in

Table 1.

Executive Functions: Statistical analyses showed a significative effect of the factor Time (F(1,66) = 12.27, p < 0.001, = 0.16), indicating a general change in the pretest and posttest variable regardless of the group. The main effect of Group was not significant (F(1,66) = 0.12, p = 0.726, = 0.00), indicating that the groups did not differ in their level of Executive Functions. Crucially, the interaction between Time and Group was significant (F(1,66) = 4.33, p = 0.041, = .06). Post-hoc analyses revealed that Executive Functions only improved in the Intervention group (t(66) = -4.07; p<0.01 Bonferroni corrected), while the change was not significant in the Control Group (t(66) = -0.97, p > 0.05 Bonferroni corrected).

General Maladjustment: The factors Time and Group were not significant (F(1, 66) = .05, p = 0.823, = 0.00) and F(1,66) = 0.07, p = 0.795, = 0.00). Importantly, the interaction between Time and Group was significant (F(1,66) = 14.00, p < 0.001, = 0.18). Post-hoc analyses revealed that General Maladjustment only improved after the intervention in the Intervention group (t(66) = 2.89; p < 0.05 Bonferroni corrected), while the change was not significant in the Control Group (t(66) = -2.41, p > 0.05 Bonferroni corrected).

4. Discussion

The present findings provide further support for the potential of strategy-based, fully digital EF interventions to promote cognitive and psychosocial improvements in children and adolescents living in vulnerable contexts. Consistent with prior evidence showing that metacognitive scaffolding enhances the effectiveness of EF training (Cáceres-González et al., 2025; Graziano & Hart, 2016; Jones et al., 2020; Kubota et al., 2023; Partanen et al., 2015; Pozuelos et al., 2018; Rossignoli-Palomeque et al., 2020)—particularly among individuals with lower baseline executive skills—participants who received the STap2Go intervention showed improvements not only in EF performance but also in self-perceived maladjustment. This pattern aligns with previous studies reporting gains for children exposed to psychosocial adversity (e.g., Cáceres-González et al., 2025), suggesting that digital, automated scaffolding may offer an accessible alternative to instructor-dependent interventions. Importantly, the present study extends existing literature by demonstrating that EF training influences not only cognitive abilities but also children’s subjective sense of adjustment—an aspect closely tied to socialization, school functioning, and emotional well-being, yet rarely included in EF intervention research.

A key contribution of this study is that, unlike traditional computerized EF programs—which typically yield gains limited to the trained tasks and show little evidence of generalization—STap2Go produced both near and far transfer effects. Whereas process-based interventions usually improve only task-specific performance and rarely influence broader executive or adaptive skills (Melby-Lervåg & Hulme, 2013; Sala & Gobet, 2019; Simons et al., 2016), our results showed improvements in standardized EF measures and, notably, in self-perceived maladjustment. This broader transfer is consistent with evidence that metacognitive, strategy-focused approaches are more likely to affect children’s functioning beyond the training context (Cáceres-González et al., 2025; Jones et al., 2020; Pozuelos et al., 2018). The reduction in maladjustment suggest that participants were able to generalize self-regulation strategies to everyday social, personal, and academic situations, supporting the idea that metacognitive scaffolding facilitates the application of EF skills across domains (Efklides, 2009; Roebers, 2017).

Another important aspect concerns the delivery format of strategy-based interventions. Most existing programs rely on a trained adult—such as a teacher, therapist, or parent—to provide metacognitive scaffolding, guide reflection, and model self-regulation strategies (Graziano & Hart, 2016; Kubota et al., 2023; Partanen et al., 2015). Although effective, this format poses substantial challenges in vulnerable contexts, where adult availability, training, and consistency may be limited, and where caregiver practices can vary widely. The use of an automated avatar in STap2Go addresses these constraints by standardizing the provision of strategies and ensuring that every child receives high-quality, consistent scaffolding regardless of their environment. For children in psychosocially adverse situations, the neutrality and predictability of the avatar may also reduce pressure, minimize evaluative concerns, and provide a stable model of regulation, thereby enhancing engagement and facilitating the internalization of strategies that might otherwise be inconsistently available in their daily contexts.

The study by Cáceres-González et al. (2025) was the first to demonstrate that a fully digital, avatar-based instructor can produce both near and far transfer effects in children living in psychosocially vulnerable contexts. Their findings showed that metacognitive scaffolding delivered by an automated agent—rather than a human instructor—was sufficient to generate meaningful cognitive and behavioral gains. The present study reinforces and extends those results by replicating the benefits of avatar-guided strategy-based training in a different geographical area and with a distinct sample of at-risk children. Crucially, we also document far-transfer effects in an outcome not previously examined: children’s perceived adjustment. This supports the robustness and generalizability of avatar-based scaffolding and suggests that such digital interventions can positively influence domains of functioning beyond cognition, including children’s self-perceived socioemotional adaptation.

The effect on General Maladjustment is particularly noteworthy and aligns with extensive evidence linking executive functioning to social competence and adaptive behavior (Diamond, 2020; Holl et al., 2021; Otsuka et al., 2021; Schulte et al., 2022; Williams et al., 2023). Executive processes play a central role in how individuals navigate everyday environments, and dimensional models of adversity emphasize that children’s interpretations of stressful experiences are critical in shaping developmental outcomes (Smith & Pollak, 2021). Strengthening EF may therefore exert indirect benefits by enhancing self-regulation, coping strategies, and reflective processes. Consistent with this view, children in the intervention not only improved their EF performance but also reported better perceptions of their own adjustment—suggesting greater self-understanding and a heightened sense of agency in social and academic contexts (Bandura, 2001). These results indicate that EF-focused interventions may help buffer the negative developmental trajectories often associated with psychosocial risk (Danese & Widom, 2024; McLaughlin et al., 2019).

Taken together, the positive changes observed in the training group, compared to the stability observed in the control group, indicate that the STap2Go intervention had a measurable impact on the executive and psychosocial domains assessed. Overall, the program demonstrated efficacy in improving overall EF and perceived adjustment, highlighting its potential as a cost-effective and scalable tool for supporting children in vulnerable environments.

Author Contributions

AAG: Conceptualization, Investigation, Formal Analysis, Writing; MVR: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing; CP: Investigation, Formal Analysis; NC: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing, Project Administration.

Funding

This work was funded by the Ministerio de Ciencia, Innovación y Universidades under grant PID2022-143111NB-I00.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding upon request.

Conflicts of interest/Competing interests

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Ethics approval

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Universidad Nebrija.

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

References

- Aguilar-González, A., Vaíllo Rodríguez, M., & Camuñas, N. (2025). Perceived adaptation and executive functioning in social risk minors. Revista Internacional de Educación para la Justicia Social, 14(2). [CrossRef]

- Aksayli, N. D., Sala, G., and Gobet, F. (2019). The cognitive and academic benefits of Cogmed: a meta-analysis. Educational Research Review, 27, 229–243. [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. (2001). Social cognitive theory: An agentic perspective. Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 1–26. [CrossRef]

- Barraca, J., & Artola González, T. (2006). La inadaptación social desde un modelo operativo. Edupsykhé. Revista de Psicología y Educación, 5(1). [CrossRef]

- Cáceres-González, D., Rossignoli-Palomeque, T., & Rodríguez, M. V. (2025). The first digital strategy-based method for training of executive functions: Impact on cognition and behavioral and emotional regulation, and academic success in children with and without psychosocial risk. Behavioral Sciences, 15(5), 633. [CrossRef]

- Camuñas, N., Mavrou, I., Vaíllo, M., & Martínez, R. M. (2022). An executive function training programme to promote behavioural and emotional control of children and adolescents in foster care in Spain. Trends in Neuroscience and Education, 27, 100175. [CrossRef]

- Carrera, P., Jiménez-Morago, J.M., Román, M., & León, E. (2019). Caregiver ratings of executive functions among foster children in middle childhood: Associations with early adversity and school adjustment. Children and Youth Services Review, 106, 104495. [CrossRef]

- Danese, A., & Widom, C. S. (2024). Objective and subjective experiences of childhood maltreatment and their relationships with cognitive deficits: a cohort study in the USA. The Lancet Psychiatry, 11(9), 720–730. [CrossRef]

- Diamond, A. (2013). Executive functions. Annual Review of Psychology, 64, 135–168. [CrossRef]

- Diamond, A. (2020). Executive functions. In Handbook of Clinical Neurology (Vol. 173, pp. 225–240). Elsevier. [CrossRef]

- Diamond, A., & Ling, D. S. (2019). Review of the Evidence on, and Fundamental Questions About, Efforts to Improve Executive Functions, Including Working Memory. In J. M. Novick, M. F. Bunting, M. R. Dougherty, & R. W. Engle (Eds.), Cognitive and Working Memory Training: Perspectives from Psychology, Neuroscience, and Human Development (pp. 145-389). Oxford University Press.

- Efklides, A. (2009). The role of metacognitive experiences in the learning process. Psicothema, 21(1), 76–82. https://reunido.uniovi.es/index.php/PST/article/view/8799.

- Erazo Santander, O. A. (2022). Programas para el mejoramiento de las funciones ejecutivas, en la niñez de contextos vulnerables. Revista Criminalidad, 64(2), 161–181. [CrossRef]

- Flores, J., Ostrosky, F., & Lozano, A. (2020). BANFE-3. Batería Neuropsicológica de Funciones Ejecutivas y Lóbulos Frontales. Manual Moderno.

- Förster, J., & López, I. (2022). Neurodesarrollo humano: un proceso de cambio continuo de un sistema abierto y sensible al contexto. Revista Médica Clínica Las Condes, 33(4), 338–346. [CrossRef]

- Friedman, N. P., & Robbins, T. W. (2022). The role of prefrontal cortex in cognitive control and executive function. Neuropsychopharmacology, 47(1), 72–89. [CrossRef]

- Graziano, P. A., & Hart, K. (2016). Beyond behavior modification: Benefits of social–emotional/self-regulation training for preschoolers with behavior problems. Journal of school psychology, 58, 91-111. [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Guanir, P. (2015). TAMAI. Test Autoevaluativo Multifactorial de Adaptación Infantil. TEA.

- Holl, A. K., Vetter, N. C., & Elsner, B. (2021). Disentangling the relations of theory of mind, executive function and conduct problems. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 72, 101233. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, D., Policelli, J., Li, M., Dharamsi, A., Hu, Q., Sheridan, M. A., McLaughlin, K. A., & Wade, M. (2021). Associations of Early-Life Threat and Deprivation With Executive Functioning in Childhood and Adolescence: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA pediatrics, 175(11), e212511. [CrossRef]

- Jones, J. S., Milton, F., Mostazir, M., & Adlam, A. R. (2020). The academic outcomes of working memory and metacognitive strategy training in children: A double-blind randomized controlled trial. Developmental science, 23(4), e12870. [CrossRef]

- Kubota, M., Hadley, L. V., Schaeffner, S., Könen, T., Meaney, J. A., Morey, C. C., Auyeung, B., Moriguchi, Y., Karbach, J., & Chevalier, N. (2023). The effect of metacognitive executive function training on children’s executive function, proactive control, and academic skills. Developmental Psychology, 59(11), 2002-2020. [CrossRef]

- McLaughlin, K. A., Sheridan, M. A., & Lambert, H. K. (2014). Childhood adversity and neural development: Deprivation and threat as distinct dimensions of early experience. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 47, 578–591. [CrossRef]

- McLaughlin, K. A., Sheridan, M. A., Humphreys, K. L., Belsky, J., & Ellis, B. J. (2021). The value of dimensional models of early experience: Thinking clearly about concepts and categories. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 16(6), 1463–1472. [CrossRef]

- McLaughlin, K. A., Weissman, D., & Bitrán, D. (2019). Childhood adversity and neural development: A systematic review. Annual Review of Developmental Psychology, 1(1), 277–312. [CrossRef]

- Melby-Lervåg, M., & Hulme, C. (2013). Is working memory training effective? A meta-analytic review. Developmental psychology, 49(2), 270. [CrossRef]

- Miyake, A., Friedman, N. P., Emerson, M. J., Witzki, A. H., Howerter, A., & Wager, T. D. (2000). The unity and diversity of executive functions and their contributions to complex “Frontal Lobe” tasks: A latent variable analysis. Cognitive Psychology, 41(1), 49–100. [CrossRef]

- Noble, K. G., Houston, S. M., Brito, N. H., Bartsch, H., Kan, E., Kuperman, J. M., ... & Sowell, E. R. (2015). Family income, parental education and brain structure in children and adolescents. Nature neuroscience, 18(5), 773-778. [CrossRef]

- Olhaberry, M., & Sieverson, C. (2022). Desarrollo socio-emocional temprano y regulación emocional. Revista Médica Clínica Las Condes, 33(4), 358–366. [CrossRef]

- Otsuka, Y., Shizawa, M., Sato, A., & Itakura, S. (2021). The role of executive functions in older adults’ affective theory of mind. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 97, 104513. [CrossRef]

- Partanen, P., Jansson, B., Lisspers, J., & Sundin, Ö. (2015). Metacognitive strategy training adds to the effects of working memory training in children with special educational needs. International Journal of Psychological Studies, 7(3), 130-140. https://doi.org/ 10.5539/ijps.v7n3p130. [CrossRef]

- Pineda-Alhucema, W., Aristizabal, E., Escudero-Cabarcas, J., Acosta-López, J. E., & Vélez, J. I. (2018). Executive function and theory of mind in children with ADHD: A systematic review. Neuropsychology Review, 28(3), 341–358. [CrossRef]

- Pozuelos, J. P., Combita, L. M., Abundis, A., Paz-Alonso, P. M., Conejero, Á., Guerra, S., & Rueda, M. R. (2019). Metacognitive scaffolding boosts cognitive and neural benefits following executive attention training in children. Developmental Science, 22(2), e12756. [CrossRef]

- Rahapsari, S., & Levita, L. (2024). The impact of adverse childhood experiences on cognitive control across the lifespan: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 0(0), 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Roebers, C. M. (2017). Executive function and metacognition: Towards a unifying framework of cognitive self-regulation. Developmental review, 45, 31-51. [CrossRef]

- Rossignoli-Palomeque, T., Quiros-Godoy, M., Perez-Hernandez, E., & González-Marqués, J., (2019). Schoolchildren’s Compensatory Strategies and Skills in Relation to Attention and Executive Function App Training. Frontiers in Psychology, 10: 2332. [CrossRef]

- Rossignoli-Palomeque, T., Perez-Hernandez, E., & González-Marqués, J. (2020). Training effects of attention and EF strategy-based training “Nexxo” in school-age students. Acta Psychologica, 210, 103174. [CrossRef]

- Sala, G., & Gobet, F. (2019). Cognitive training does not enhance general cognition. Trends in cognitive sciences, 23(1), 9-20. [CrossRef]

- Schulte, M., Trujillo, N., Rodríguez-Villagra, O. A., Salas, N., Ibañez, A., Carriedo, N., & Huepe, D. (2022). The role of executive functions, social cognition and intelligence in predicting social adaptation of vulnerable populations. Scientific Reports, 12(1). [CrossRef]

- Shipstead, Z., Hicks, K. L., & Engle, R. W. (2012). Cogmed working memory training: Does the evidence support the claims? Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition, 1(3), 185–193. [CrossRef]

- Simons, D. J., Boot, W. R., Charness, N., Gathercole, S. E., Chabris, C. F., Hambrick, D. Z., & Stine-Morrow, E. A. (2016). Do “brain-training” programs work? Psychological science in the public interest, 17(3), 103-186. [CrossRef]

- Smith, K. E., & Pollak, S. D. (2021). Rethinking concepts and categories for understanding the neurodevelopmental effects of childhood adversity. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 16(1), 67–93. [CrossRef]

- STap2Go S.L. (2022). STap2Go. (1.3.0) [App]. Available online: https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=com.GeneticAI.STap2Go&hl=es_419&gl=US (accessed on 14 November 2022).

- Takacs, Z. K., & Kassai, R. (2019). The efficacy of different interventions to foster children’s executive function skills: A series of meta-analyses.Psychological Bulletin, 145(7), 653–697. [CrossRef]

- 45. The jamovi project (2025). jamovi (Version 2.7.6.0.) [Computer software]. Retrieved from https://www.jamovi.org.

- Vaíllo, M., & Camuñas, N. (2015). Procesos y programas para desarrollar las funciones ejecutivas. In Procesos y programas de neuropsicología educativa (pp. 139–149). Ministerio de Educación, Cultura y Deporte: Subdirección General de Documentación y Publicaciones. https://portalinvestigacion.nebrija.com/documentos/6626a6c6b70f9877bf769c06.

- Wade, M., Fox, N.A., Zeanah, C.H., & Nelson, C.A. (2019). Long-term effects of institutional rearing, foster care, and brain activity on memory and executive functioning. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A., 116 (5), 1808–1813. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X., & Feng, T. (2024). Does executive function affect children’s peer relationships more than emotion understanding? A longitudinal study based on latent growth model. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 66, 211–223. [CrossRef]

- Williams, R., Andreassi, S., Moselli, M., Fantini, F., Tanzilli, A., Lingiardi, V., & Laghi, F. (2023). Relationship between executive functions, social cognition, and attachment state of mind in adolescence: An explorative study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(4), 2836. [CrossRef]

- Yeh, Z.-T., Tsai, M.-C., Tsai, M.-D., Lo, C.-Y., & Wang, K.-C. (2017). The relationship between theory of mind and the executive functions: Evidence from patients with frontal lobe damage. Applied Neuropsychology: Adult, 24(4), 342–349. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).