Submitted:

01 January 2026

Posted:

04 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

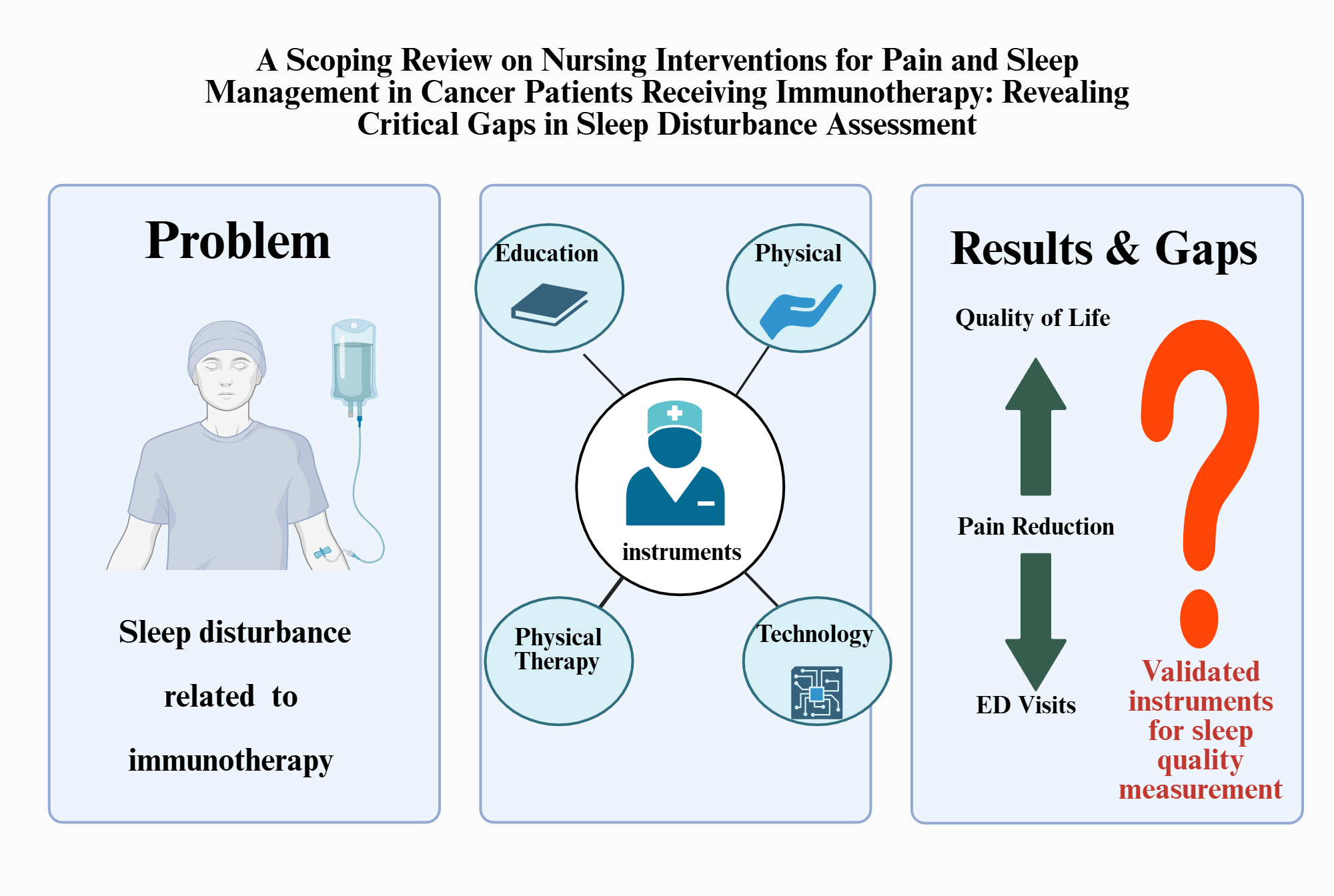

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

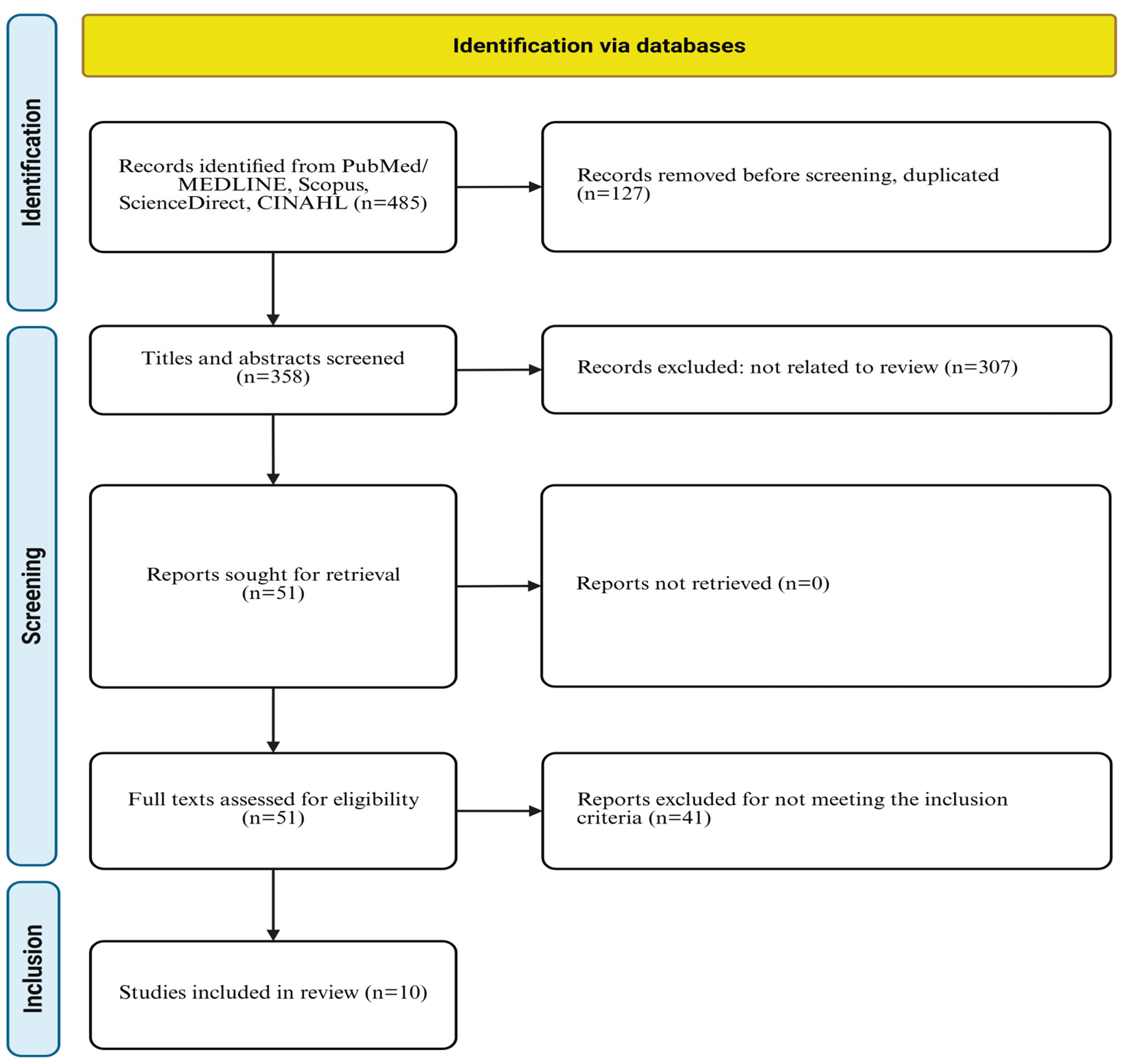

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Inclusion Criteria and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Risk of Bias Assessment Tool

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Selected Studies

3.2. Nursing Intervention Types and Components

3.2.1. Educational Interventions

- ▪ Pain mechanisms

- ▪ Expected postoperative pain trajectory

- ▪ Analgesic options

- ▪ Non-pharmacological pain strategies

- ▪ Self-management steps

3.2.2. Physical Interventions

3.2.3. Cognitive-Behavioral and Integrated Interventions

3.2.4. Technology Based Approaches

3.3. Outcomes and Effectiveness (Table 3)

3.3.1. Pain Outcomes

3.3.2. Sleep Quality Outcomes

3.3.3. Quality of Life and Patient Satisfaction

3.3.4. Health Services Utilization

3.4. Implementation Factors and Future Research

4. Discussion

4.1. The Current Situation

- The timely dedicated care can be offered by a nurse practitioner, member of the palliative care team (nurse or physician), family doctor, oncologist in the Canadian healthcare system. This highlights the importance of early palliative care referral, which should have been arranged by his rural family doctor at the same time of referral to the oncology service.

- How can we work smarter and save healthcare dollars at the same time?

4.2. What Nurse-Led Interventions May Achieve

4.3. How New Technologies May Transform the Canadian Healthcare

4.4. Limitations of This Report

4.5. Clinical Implications

- Implement routine sleep screening: Given 51.9% prevalence and survival implications, systematically assess sleep disturbances in all ICI-treated patients [19].

- Address digital equity: Develop alternative monitoring strategies for patients with limited digital literacy or access [12].

- Design longitudinal interventions: Incorporate extended follow-up (minimum 6 months, ideally 12+ months) and maintenance strategies aligned with chronic immunotherapy duration rather than time-limited programs. Include booster sessions and ongoing support mechanisms to sustain intervention effects throughout the ICI treatment continuum [9,15].

- Target symptom clusters: Address pain, sleep, and fatigue as interconnected symptoms sharing inflammatory mechanisms [19].

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Abbreviations | Full Form |

| BPI | Brief pain inventory |

| CAPAMOS | cancer pain monitoring system |

| CBT-I | Cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia |

| CI | Confidence interval |

| CINHAL | Cumulated Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature |

| CRC | Colorectal cancer |

| CTLA-4 | Cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 |

| ECOG | Eastern cooperative oncology group |

| ED | Emergency department |

| eHealth | Electronic health |

| EORTC QLQ-C30 | European organization for research and treatment of cancer quality of life questionnaire-Core 30 |

| EORTC-QLG-H&N35 | European organization for research and treatment of cancer quality of life questionnaire-head and neck 35 |

| ePRO | Electronic patients reported outcome |

| EQ-5D | Euro-QoL 5-dimension questionnaire, |

| FKSI-DRS | Functional assessment of cancer therapy -kidney symptom index-disease related symptoms |

| GU | genitourinary |

| HADS | Hospital anxiety and depression scale |

| HCC | Hepatocellular carcinoma |

| H&N | Head and neck journal |

| HR | Hazard ratio |

| HRQoL | Health-related quality of life, |

| ICI | Immune checkpoint inhibitor |

| int | Intervention group |

| irAE | Immune related adverse event |

| LCSS | Lung cancer symptom scale |

| N | Sample size |

| NRS | Numeric rating scale |

| PD-1 | Programmed cell death protein 1 |

| PD-L1 | Programmed death-ligand 1 |

| PRISMA-ScR | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews |

| PRO | Patients reported outcome |

| PRO-CTCAE | Patient reported outcomes version of the common terminology criteria for adverse events |

| PSQI | Pittsburgh sleep quality index |

| QoL | Quality of life |

| RCT | Randomized controlled trial |

| SAS | Self-rating anxiety scale |

| SDS | Self-rating depression scale |

| SMD | Standardized mean difference |

| SMS | Short message service |

| STAI | state-trait anxiety inventory |

| USA | USA: united states of America |

| VAS | Visual analog scale |

| Vs | Versus |

References

- Morikawa, M; Kajiwara, K; Kobayashi, M; Kanno, Y; Nakano, K; Matsuda, Y; et al. Nursing support for pain in patients with cancer: a scoping review. Cureus 2023, 15(11), e38161938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dine, J; Gordon, R; Shames, Y; Kasler, MK; Barton-Burke, M; Burke, S; Lee, J; Patel, H; Wong, A; Chen, L; et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitors: an innovation in immunotherapy for the treatment and management of patients with cancer. Asia Pac J Oncol Nurs. 2017, 4(2), 127-135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aktepe, B. Sleep Quality and Its Determinants Among Patients with Metastatic Cancer Treated with Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors: A Two-Center Cross-Sectional Study. Medicina 2025, 61(12), 2131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colomer-Lahiguera, S; Bryant-Lukosius, D; Rietkoetter, S; Martelli, L; Ribi, K; Fitzpatrick-Lewis, D; Sherifali, D; Orcurto, A; Juergens, R; Eicher, M. Patient-reported outcome instruments used in immune-checkpoint inhibitor clinical trials in oncology: a systematic review. J Patient Rep Outcomes 2020, 4(1), 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y; Zhang, Z; Gong, Q; Yang, G; Wu, Z; Yang, Z; Zhao, X. Analysis of primary nursing intervention for elderly patients with cancer pain on the improvement of potential risk and pain degree. Am J Transl Res. 2021, 13(10), 11890-11898. [Google Scholar]

- Miao, J; Wang, Y; Li, X; Zhang, L; Chen, H; Liu, Q. Effectiveness of comfort nursing combined with continuous nursing on patients with colorectal cancer chemotherapy. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2022, 2022, 9647325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfaro-Díaz, C; García-Sánchez, R; López-Montesinos, MJ; Martínez-Galiano, JM; Fernández-Alcántara, M; Cabañero-Martínez, MJ; Cabrero-García, J; Richart-Martínez, M; Andreu-Periz, L; Cabañero-Martínez, A; et al. Effectiveness of nursing interventions for patients with cancer and their family members: a systematic review. J Fam Nurs. 2022, 28(2), 95-114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, S; Sato, F; Tagami, K; Takahashi, S. Clinical Trial Protocol: Randomized Controlled Trial of Cancer Pain Monitoring System (CAPAMOS) in Patients with Advanced Cancer. Open J Nurs. 2022, 12(2), 113-124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzadeh, P; Pituskin, E; Au, I; Sneath, S; Buick, CJ. Cancer Immunotherapy: The Role of Nursing in Patient Education, Assessment, Monitoring, and Support. Curr Oncol. 2025, 32(7), 392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, AC; Lillie, E; Zarin, W; O’Brien, KK; Colquhoun, H; Levac, D; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018, 169(7), 467-473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S; Zhang, Y; Wang, L; Chen, J; Liu, H; Zhao, Q. The effect of pain-education nursing based on a mind map on postoperative pain score and quality of life in patients with colorectal cancer. Medicine (Baltimore) 2023, 102(19), e33562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L; Shah, N; Li, J; Patel, S; Wang, Y; Chen, X; Brown, S; Lee, H; Gupta, R; Thompson, J; et al. Efficiency of electronic health record assessment of patient-reported outcomes after cancer immunotherapy: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2022, 5(3), e224427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, ET; Singhal, S; Dickerson, J; Gabster, B; Wong, HN; Aslakson, RA; Schapira, L; AAHPM Research Committee Writing Group. Patient-reported outcomes for cancer patients receiving checkpoint inhibitors: opportunities for palliative care—a systematic review. J Pain Symptom Manage 2019, 58(1), 137-156.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwok, C; Lee, CF; Choi, KC; Chan, CW; Chair, SY; So, WK; Leung, DY; Ho, SS; Cheng, KK; Yates, P; et al. Nurse-led telehealth interventions for symptom management in patients with cancer receiving systemic or radiation therapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Support Care Cancer 2022, 30(9), 7119-7132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, YJ; Lee, MK. Effects of nurse-led nonpharmacological pain interventions for patients with cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2022, 54(4), 422-433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, S; Liu, H; Wang, Y; Chen, L; Zhao, Q; Li, X; Zhang, M; Zhou, Y; Huang, J; Wu, P; et al. Assessment of non-pharmacological nursing strategies for pain management in tumor patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Pain Res. 2025, 6, 1447075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Guo, H. Impact of personalized nursing on the quality of life in lung cancer patients. Front Oncol. 2025, 15, 650066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolstrup, LK; Pappot, H; Bastholt, L; Zwisler, AD; Dieperink, KB; Johansen, C; Nielsen, DL; Andersen, MH; Schmidt, H; Larsen, MB; et al. Patient-reported outcomes during immunotherapy for metastatic melanoma: mixed methods study of patients’ and clinicians’ experiences. J Med Internet Res. 2020, 22(4), e14896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, L; Zhang, H; Chen, Y; Wang, X; Liu, Q; Zhao, M; Li, S; Huang, Y; Zhou, J; Fang, L; et al. A longitudinal study on symptom distress and management of transhepatic arterial interventional chemotherapy combined with targeted therapy and immunotherapy based on patient self-reported outcomes. Holist Integr Oncol. 2025, 4(1), 1-9. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Ghabeesh, SH; Bashayreh, IH; Saifan, AR; Rayan, A; Alshraifeen, AA. Barriers to Effective Pain Management in Cancer Patients From the Perspective of Patients and Family Caregivers: A Qualitative Study. Pain Manag Nurs. 2020, 21(3), 238–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saifan, AR; Bashayreh, IH; Al-Ghabeesh, SH; Batiha, A; Alrimawi, I; Al-Saraireh, M; Al-Momani, MM. Exploring factors among healthcare professionals that inhibit effective pain management in cancer patients. Central European Journal of Nursing and Midwifery 2019, 10(1), 967–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Omari, D; Alhabahbeh, A; Subih, M; Aljabery, A. Pain management in the older adult: The relationship between nurses' knowledge, attitudes and nurses' practice in Ireland and Jordan. Appl Nurs Res. 2021, 57, 151388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, Y; Zeng, K; Qin, L; Luo, J; Liu, S; Miao, J; et al. Differential characteristics of fatigue–pain–sleep disturbance–depression symptom cluster and influencing factors of patients with advanced cancer during treatment: a latent class analysis. Cancer Nurs. 2025, 48(5), 352–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheikh-Wu, SF; Downs, CA; Anglade, D. Interventions for managing a symptom cluster of pain, fatigue, and sleep disturbances during cancer survivorship: a systematic review. Oncol Nurs Forum 2020, 47(4), E107-E119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, L; Shi, Y; Zhou, S; Gong, L; Zhang, L; Tian, J. Intervention model under the Omaha system framework can effectively improve the sleep quality and negative emotion of patients with mid to late-stage lung cancer and is a protective factor for quality of life. Am J Cancer Res. 2024, 14(3), 1278–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Miaskowski, C; Cooper, BA; Dhruva, A; Dunn, LB; Langford, DJ; Cataldo, JK; et al. Evidence of associations between cytokine genes and subjective reports of sleep disturbance in oncology patients and their family caregivers. PLoS One 2012, 7(7), e40560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balachandran, DD; Ganjoo, K; Patel, S; Chai, PR; Sullivan, M; Wang, K; et al. The impact of immunotherapy on sleep and circadian rhythms in patients with cancer. Front Oncol. 2023, 13, 1295267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarogoulidis, P; Petridis, D; Kosmidis, C; Sapalidis, K; Nena, L; Matthaios, D; Papadopoulos, V; Perdikouri, EI; Porpodis, K; Kakavelas, P; et al. Non-small-cell lung cancer immunotherapy and sleep characteristics: the crossroad for optimal survival. Diseases 2023, 11(1), 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbour, C; Hjeij, D; Bilodeau, K.; 2024 — Nursing Sleep Education (Includes Pain-Related Sleep Disruption) Arbour. Managing sleep disruptions during cancer: practical tips for patient education. Can Oncol Nurs J 2024, 34(4). [Google Scholar]

- Brink. Nursing Management of Symptom Clusters (Pain + Sleep) Brink A. Understanding and managing symptom clusters: insights for oncology nurses. Oncol Nurs News 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Miladinia, M; Jahangiri, M; Kennedy, AB; Fagerström, C; Tuvesson, H; Safavi, SS; et al. Determining massage dose-response to improve cancer-related symptom cluster of pain, fatigue, and sleep disturbance: a 7-arm randomized trial in palliative cancer care. Palliat Med. 2023, 37(1), 108-119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munir, S; Connolly, M; Davies, AN. Non-pharmacological interventions for sleep disturbance (“insomnia”) in patients with advanced cancer: a scoping review. Support Care Cancer 2025, 33, 486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nissen, ER; Neumann, H; Knutzen, SM; Henriksen, EN; Amidi, A; Johansen, C; von Heymann, A; Christiansen, P; Zachariae, R. Interventions for insomnia in cancer patients and survivors—a comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis. JNCI Cancer Spectr. 2024, 8(3), pkae041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calvo-Schimmel, A; Kober, KM; Paul, SM; Cooper, BA; Harris, C; Shin, J; Hammer, MJ; Conley, YP; Dokiparthi, V; Olshen, A; et al. Sleep disturbance is associated with perturbations in immune-inflammatory pathways in oncology outpatients undergoing chemotherapy. Sleep Med. 2023, 101, 305-315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z; Yang, Y; Sun, J; Dong, Y; Zhu, M; Wang, T; Teng, L. Heterogeneity of pain-fatigue-sleep disturbance symptom clusters in lung cancer patients after chemotherapy: a latent profile analysis. Support Care Cancer 2024, 32(12), 821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, Y; Duan, Y; Zhou, Y; Yi, S; Dai, C; Luo, X; Kang, Y; Wan, Z; Qin, N; Zhou, X; Liu, X; Xie, J; Cheng, ASK. The Level of Psychological Distress Is Associated With Circadian Rhythm, Sleep Quality, and Inflammatory Markers in Adolescent and Young Adults With Gynecological Cancer. Cancer Nurs;Epub 2025, 48(5), E289–E295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tai, P; Alqaisi, O; Al-Ghabeesh, S; et al. Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors in Merkel Cell Carcinoma of the Skin: A 2025 Comprehensive Review. Cancers (Basel) Published. 2025, 17(19), 3272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, L; Su, Z; He, Y; Pang, Y; Zhou, Y; Wang, Y; Lu, Y; Jiang, Y; Han, X; Song, L; Wang, L; Li, Z; Lv, X; Wang, Y; Yao, J; Liu, X; Zhou, X; He, S; Zhang, Y; Li, J; Wang, B; Tang, L. Association between anxiety, depression, and symptom burden in patients with advanced colorectal cancer: A multicenter cross-sectional study Top of Form. Cancer Med. 2024, 13(11), e7330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Liu, Y; Yan, Q; Zhou, J; Yao, X; Ye, X; Chen, W; Cai, J; Jiang, H; Li, H. Identification of distinct symptom profiles in prostate cancer patients with cancer-related cognitive impairment undergoing androgen deprivation therapy: A latent class analysis. Asia Pac J Oncol Nurs 2024, 11(6), 100497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Dennis, K; Harris, G; Kamel, R; Barnes, T; Balboni, T; Fenton, P; Rembielak, A. Rapid Access Palliative Radiotherapy Programmes. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2020, 32(11), 704–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O'Reilly, E; Golshan, M; Chng, N; Bartha, LR; Drummond, L; Hoegler, D; Becker, N; Mou, B. Effect of Same-Day Volumetric Modulated Arc Therapy on Resource Utilization in Rapid Access Palliative Radiotherapy Clinics Using a Radiation Oncologist-Initiated Automated Planning Script. Cureus 2025, 17(10), e95165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wei, M; Yusuf, A; Hsien, CCM; Marzuki, MA. Effects of behavioural activation on psychological distress among people with cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Nurs Stud;Epub 2025, 164, 104983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, SR; Ma, L; Xu, XY; Zhou, S; Xie, HM; Xie, CS. Effects of Aromatherapy on Physical and Mental Health of Cancer Patients Undergoing Radiotherapy and/or Chemotherapy: A Meta-Analysis. Chin J Integr Med 2024, 30(5), 449–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Authors/ years | Country | Study design | Settings | Cancer type | Sample size | Age (years) | ICIs used |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tolstrup [18] | Denmark | Mixed methods RCT | University hospital | Metastatic melanoma | N= 70 (57 surveyed) | Median 65 | Immunotherapy |

| Hall [13] | USA/multi country | Systematic review | Multi center trails | Melanoma, lung, GU, H&N | 15 RCTs | 44.1-67.3 | Nivolumab, pembrolizumab |

| Zhang [12] | China | RCT | 28 Tertiary hospitals | Gastric, esophageal, lung | N=278 (141 int.) | 58.8 ±12.7 | Multiple ICIs |

| Mirzadeh [9] | Canada | Perspective | Clinical practices | All ICI candidates | Review | Not specific | PD-1/PD-L/CTLA-4 |

| Yan [16] | China | Systematic review | Multiple databases | Various cancer types | 1,070 (17 RCTs) | Not specific | Various (review) |

| Kwok [14] | Multiple countries | Systematic review | Multiple settings | Various cancer types | 2,315 (10 studies) | Variable means | Various (review) |

| Liu [17] | China | Retrospective cohort | Hubei cancer hospital | Lung cancer (stage II-IV) | N = 291 (137 int.) | 65.1±7.9 vs 65.5±8.4 | Chemo, targeted, immune |

| Bu [19] | China | Longitudinal study | Tertiary hospital | Hepatocellular carcinoma | N = 130 | 46-69 (66.2%) | Immune+ targeted+ interventions |

| Li [11] |

China | Retrospective observational | 2 tertiary hospitals | Colorectal cancer | N = 100 (50 int.) | Not specified | Adjuvant / Chemotherapy |

| Park [15] | South Korea | Systematic review | Multiple databases | Various cancer type | 22 RCTs | 44.1-67.3 | Music, physical, psycho-educational |

| Study | Cancer stage | Intervention type | Key components | Duration | Delivery methods |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tolstrup [18] | Metastatic | eHealth PRO weekly | Weekly PRO-CTCAE symptoms reporting via tablet from home | Weekly during treatment | eHealth platform (home-based) |

| Hall [13] | Unresectable/metastatic (n=13), adjuvant (n=2) | PRO measurement | Systemic review of 15 ICI trials with PRO data | Various | Various clinical trial questionnaires |

| Zhang [12] | Mixed cancer types | ePRO follow up model with alerts | Questionnaire + image recognition for irAE grading; automated advice for grades 1-2; alert for grades 3-4 | 6 months or until treatment ends | Mobile app/ web-based + image recognition |

| Mirzadeh [9] | Various stages | Nursing education, assessment, monitoring | Patient education (multiple formats), symptoms assessment, nurse-led clinics, support services | Ongoing throughout treatment | In-person, telephone, video, written materials |

| Yan [16] | Various (systematic review) | Non-pharmacological pain management |

Reflexology, aromatherapy, acupressure, massage therapy, acupuncture. | Varied (1990-2023) | In-person therapy sessions |

| Kwok [14] | Various | Nurse-led telehealth | Telephone calls, video consultations, web-based systems, SMS, mobile apps (reactive/scheduled) | ≥ 4 weeks minimum | Telephone, video, web SMS, mobile applications |

| Liu [17] | Stage II-IV (72.3% stages III-IV) | Personalized nursing care |

20-30 minutes baseline consultation + telephone/video follow-ups on days 4 & 10 of each cycle | 8 weeks post-treatment initiation | Telephone & video consultations |

| Bu [19] | Advanced stage | Symptom self-report questionnaires | Symptoms assessment at weeks 1,2,3 using standardized scales | 3 weeks post intervention | Paper-based questionnaires (in-person) |

| Li [11] | Various | Pain education nursing with mind mapping | Nurses used mind map to guide pain education and perioperative care planning | Perioperative and postoperative | Repeated in-person education sessions |

| Park [15] | Various (systematic review) |

Nurse-led Non pharmacological interventions | Music interventions, physical exercises, psycho-educational programs | Various timeframes | Various (nursing delivered) |

| Study | Instruments used | Primary outcomes | Future recommendations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tolstrup [18] | Patients feedback form (13 items), interviews, focus group | Patient/clinician satisfaction, symptom awareness, patient involvement | Standardize PRO measurement; improve clinician-patients communication tracking; multicenter validation |

| Hall [13] | EORTC QLQ-C30 (80%), EQ-5D (67%), FKSI-DRS, LCSS, EORTC QLQ -H&N35 | HRQoL with ICIs vs other therapies | Develop ICI-specific PRO instruments; harmonize outcomes measurement; long-term HRQoL tracking |

| Zhang [12] | PRO-based QoL questionnaire, EORTC QLQ-C30 | Serious irAEs (Grades 3-4), ED visits, QoL, treatment discontinuation | Large-scale RCTs in diverse populations; cost effectiveness studies; digital literacy interventions |

| Mirzadeh [9] | Risk assessment tools, educational frameworks | Early detection of irAEs, patients’ educations effectiveness | Multi-setting evaluation of nursing roles; systematic protocols for early detection; international collaboration |

| Yan [16] | BPI, NRS, VAS | Cancer-related pain reduction | Standardized intervention protocols; dose-response studies; combination therapy trails; 6–12-month outcomes |

| Kwok [14] | EORTC QLQ-C30, EQ-5D, various symptom scales | Health services use, QoL, symptom severity | More nurse-led telehealth RCTs; consistent outcomes measurement; reactive vs scheduled comparison; cost-effectiveness |

| Liu [17] | EORTC QLQ-C30, HADS, STAI | Overall QoL improvement at 8 weeks | Multicenter RCTs with extended follow-up; diverse populations; cost-benefit analysis; mechanistic studies |

| Bu [19] | Symptom assessment scale (Likert 0-6) | Dynamic symptom changes over 3 weeks | Extended longitudinal studies; larger sample sizes; earlier intervention (pre-treatment); trajectory modeling |

| Li [11] | VAS (pain), SAS/SDS (anxiety/depression), EORTC QLQ-C30 | Postoperative pain, QoL, emotional distress, comfort | Multicenter trials; long-term follow-up; blinded design; economic evaluation; adaptability to different settings |

| Park [15] | Various pain measure, HRQoL instruments | Pain reduction, knowledge of pain management, pain coping | Standardized intervention protocols; optimal dosing guidelines; mechanism studies; patient-centered outcomes |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).