1. Introduction

The complement system is a conserved innate immune network[

1,

2] that detects pathogens, altered self-surfaces, and immune complexes, triggering opsonization, inflammation, and lytic activity[

3,

4,

5]. Beyond its classical role in peripheral immunity, complement components are now recognized as locally produced and regulated within the CNS[

6], where they participate in synaptic pruning, glial activation, neuroimmune communication, and maintenance of tissue homeostasis[

7,

8]. Dysregulated complement activity has been implicated in neurodegenerative, neuropsychiatric, and neuroinflammatory disorders[

9,

10,

11].

Nanotechnology has emerged as a transformative platform for drug delivery, vaccine development, and molecular imaging[

12]. Nanoparticles, including liposomes, polymeric nanoparticles, lipid nanoparticles, dendrimers, inorganic nanostructures, and hybrid materials commonly range from 1–200 nm and exhibit unique chemical and physical properties that dictate their interactions with immune components. Extensive preclinical and clinical evidence demonstrates that nanoparticles can activate complement through multiple pathways[

13], leading to complement activation-related pseudoallergy (CARPA)[

14], altered pharmacokinetics, and inflammatory reactions that can be consequential for CNS delivery, where immune activation at the BBB or within neural tissue can have disproportionate consequences.

Opioid use disorder (OUD)[

15] is increasingly conceptualized as a condition involving persistent neuroimmune alterations. Chronic opioid exposure activates microglia[

16,

17] and astrocytes[

18,

19,

20], modifies cytokine and chemokine signaling, and disrupts BBB integrity[

21]. Importantly, while cytokine-based neuroinflammation in OUD is well documented, direct measurements of complement activation in OUD remain limited. Existing evidence largely derives from transcriptomic changes, glial phenotypes, and indirect inflammatory markers.

Given these parallel developments, understanding how complement biology intersects with nanoparticle immune interactions and opioid-induced neuroimmune signaling is essential for advancing nanomedicine-based CNS therapeutics, particularly for addiction. This review integrates established and emerging evidence to clarify mechanistic convergence points and translational implications.

2. Complement Biology in Systemic and CNS Immunity

The complement system plays a significant role in the peripheral and central nervous system immunity function. The role of the complement system has been related to both neuroprotective and neuroinflammatory functions[

22,

23]. There has also been correlative studies into the relation between the complement system and the onset of various of neurological and psychiatric disorders.

2.1. Overview of Complement Activation Pathways and Regulators

Complement activation[

24] is initiated through three canonical pathways: Classical pathway is triggered by C1q binding to immunoglobulin (IgG or IgM) within immune complexes or other C1q-reactive molecular patterns. Lectin pathway is initiated by mannose-binding lectin (MBL) or ficolins recognizing specific carbohydrate motifs, leading to MASP-mediated cleavage of C4 and C2. The alternative pathway is continuously active, also called “tick over”. It is activated due to spontaneous C3 hydrolysis, generating C3(H₂O), which can bind factor B and form C3 convertase on permissive surfaces. All pathways converge at C3 cleavage, generating C3a (anaphylatoxin) and C3b (opsonin), followed by formation of C5 convertase and production of C5a and C5b-9 membrane attack complex (MAC). Host tissues express multiple regulators such as CR1, CD46 (MCP), CD55 (DAF), CD59 (MAC inhibitor), factor H,[

24] and C1 inhibitor located at different strategic points to prevent excessive complement activation. The spatial and cellular distribution of these regulators shapes local complement activity and susceptibility to inflammation.

2.2. Complement in the CNS

Most cells in brain including neurons, astrocytes, microglia, pericytes, and endothelial cells produce complement proteins[

25,

26,

27,

28]. Complement influences CNS physiology through different mechanisms. During synaptic pruning C1q and C3b tag synapses for microglial recognition via complement receptor 3 (CR3)[

29]. The anaphylatoxins, C3a and C5a modulate astrocytic cytokine production and microglial chemotaxis[

30]. They regulate endothelial permeability and leukocyte recruitment. While these processes are essential for normal CNS homeostasis, excessive or mislocalized complement activation contributes to neurodegeneration and maladaptive circuit remodeling and therefore implicated in Alzheimer’s disease, lupus, [

31,

32]schizophrenia, traumatic brain injury, and multiple sclerosis[

33,

34]. These diverse roles highlight the need for precise control of complement, especially in contexts where neuroimmune signals are already altered, such as chronic opioid exposure.

3. Complement Activation by Nanomaterials

Nanoparticles encounter complement components immediately upon contact with blood or interstitial fluid. Complement activation depends on particle size, charge, curvature, surface chemistry, protein corona composition, and material type. These nanoparticle dependent complement activation mechanisms[

13] primarily occur as mimicking the actions of other naturally occurring biological agents.

3.1. Protein Corona and Complement Initiation

Upon exposure to biological fluids, plasma proteins adsorb onto nanoparticle surfaces, forming a protein corona that dictates subsequent immune interactions[

35]. Studies demonstrate that complement proteins, immunoglobulins, pentraxins (e.g., CRP), and glycoproteins are common corona constituents. Particle properties such as hydrophobicity, surface charge, and pattern density influence the type and conformation of adsorbed proteins, shaping complement recognition. The corona composition determines which complement pathway, classical, lectin, or alternative pathway is preferentially activated.

3.2. Complement Pathway Activation Mechanisms

Nanoparticles activate the classical pathway via mechanisms that include - (a) natural IgM or IgG binding to exposed phospholipid head groups or hydrophobic domains[

36]; (b) CRP binding, which in turn recruits C1q; and direct C1q/surface interactions[

37], known to occur for certain polymeric or inorganic nanomaterials. Classical pathway activation generates C4b2a convertase, leading to robust C3 cleavage and downstream inflammation. MBL and ficolins bind to glycan structures on nanoparticle surfaces, and glycoproteins within the protein corona[

38]. Activated MASPs then initiate C4 and C2 cleavage. Some carbohydrate-decorated nanoparticles demonstrate preferential lectin pathway engagement.

The alternative pathway is especially relevant for nanomaterials because the spontaneously generated C3b can covalently attach to nucleophilic groups on nanoparticle surfaces, Factor B binding and factor D cleavage form the alternative C3 convertase (C3bBb), and properdin may stabilize this convertase, amplifying activity even on “stealth” surfaces. Many nanomaterials exhibit substantial alternative pathway amplification, making this pathway a key target for nanoparticle engineering.

4. Engineering Nanoparticles to Control Complement Activation

Due to the specificity of nanoparticle modulation in complement activation, numerous potential nanoparticle designs can aid in the process of complement activation control. Some of the suggested ways include PEGylation and polymer engineering, Zwitterionic and biomimetic coating, displaying numerous complement regulator on nanoparticles, control of physiochemical properties, and temporal or compartmental complement inhibition. A detailed account of how each one of these listed potential innovations is discussed below.

4.1. PEGylation and Polymer Engineering

Dense, brush-like polyethylene glycol (PEG) layers reduce protein adsorption and sterically hinder complement components[

39]. However, suboptimal PEG density or conformation can still allow C3b deposition. In addition, PEG architecture (chain length, grafting density, linear vs. branched) influences the shift between classical and lectin pathway activation. Optimizing PEG parameters remains central to minimizing complement activation.

4.2. Zwitterionic and Biomimetic Coatings

Zwitterionic materials (phosphorylcholine, sulfobetaine) mimic membrane headgroups and exhibit low-fouling behavior[

40]. Biomembrane-derived coatings (e.g., erythrocyte or platelet membranes) also reduce C1q and MBL recognition and can suppress alternative pathway activation.

4.3. Display of Complement Regulatory Proteins

Decorating nanoparticles with complement regulators such as CD46, CD55, or CD59 can help reduce/prevent complement activation by accelerating convertase decay, reducing C3b amplification, and blocking MAC assembly[

36,

38]. These strategies create a local complement-suppressive microenvironment without systemic immunosuppression.

4.4. Control of Physicochemical Properties

Particle features strongly influence complement activation. Nanoparticles ~40–250 nm often show stronger complement activation than very small or large particles. Cationic surfaces are more complement-activating than neutral or slightly anionic ones. Highly curved surfaces may expose reactive groups that promote C3b attachment. Rational design of these parameters reduces complement turnover on nanoparticle surfaces.

4.5. Temporal or Compartmental Complement Inhibition

Complement inhibitors (e.g., C3 inhibitors, C5 blockers, C5aR1 antagonists) can be co-administered to reduce acute complement activation during nanoparticle infusion[

41]. Emerging strategies include: local release of inhibitors from nanoparticles, nanobody-based inhibitors targeted to specific tissues, and transient suppression of complement at the BBB or inflamed CNS regions

5. Complement Signaling in Opioid Use Disorder

Past research has suggested evidence supporting various mechanisms of complement signaling involved with opioid use disorder. Human and animal model research has suggested opioid use modulated complement response in neural glia cells as well as neuroimmune networks.

5.1. Evidence for Complement Modulation in OUD

Human studies and animal models suggest that opioid exposure alters components of the innate immune system, including complement. Although fewer studies have directly quantified complement proteins than cytokines or chemokines, available evidence indicates altered expression of complement-related genes (e.g., C1q, C3) in brains of opioid-exposed rodents, changes in peripheral inflammatory markers in individuals with OUD[

42,

43], and elevated glial activation in opioid-associated neuroinflammation, consistent with complement involvement.

5.2. Opioids and Neuroimmune Signaling Networks

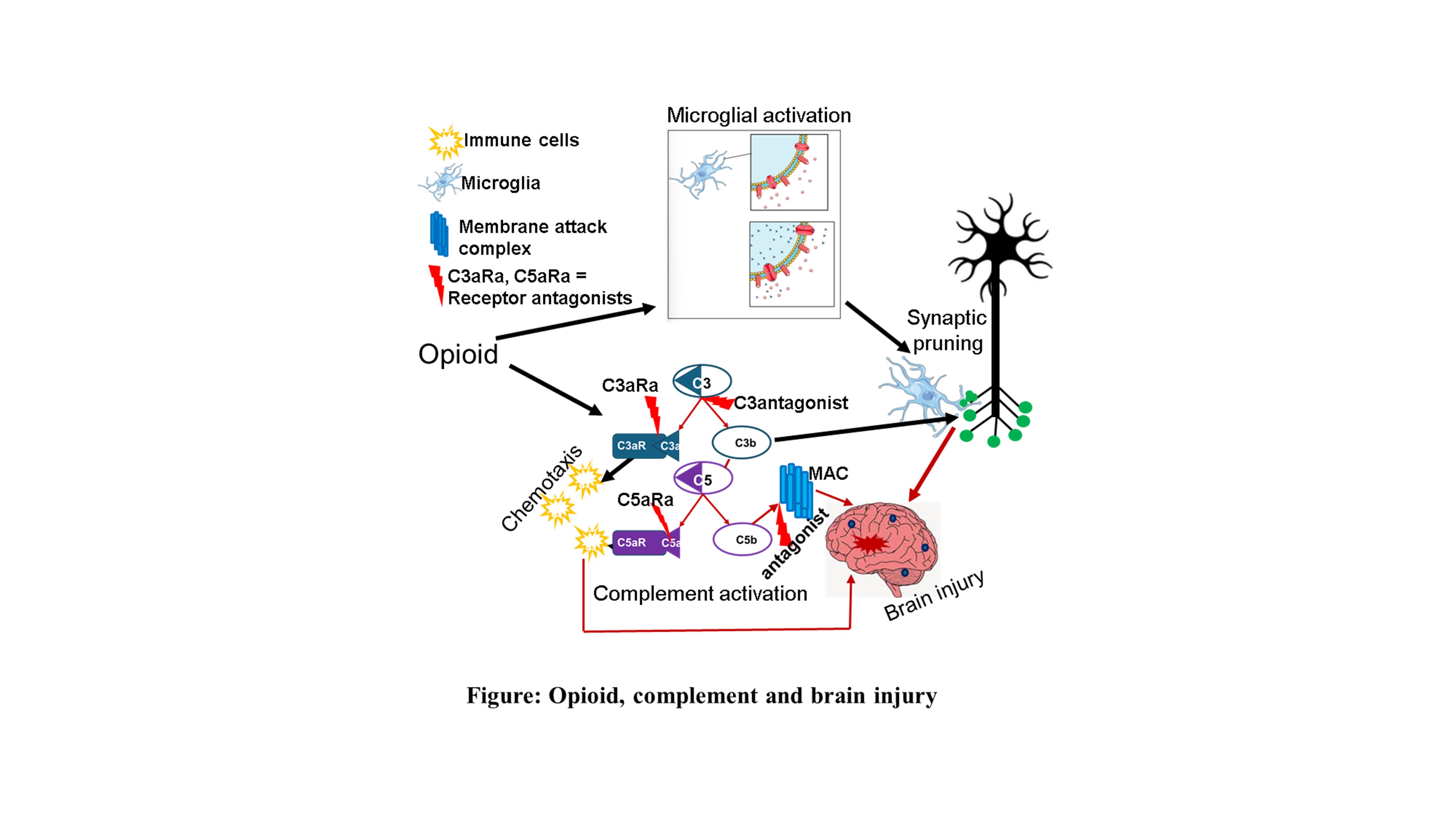

Chronic opioids activate microglia[

16] and astrocytes[

44], increase proinflammatory cytokine release, alter Toll-like receptor and purinergic signaling, and disrupt neuronal/glial communication. Complement components[

45], especially C1q, C3a, C3b, and C5a, intersect with these pathways, suggesting potential synergistic or additive effects.

5.3. Complement-Related Glial Phenotypes in Opioid Exposure

Animal studies show upregulation of complement proteins in microglia within reward-relevant regions[

46], increased astrocytic reactivity associated with inflammatory signaling, microglial engagement of complement-dependent synaptic pruning pathways. These findings support a model in which complement contributes to opioid-related changes in neuroimmune states and neural circuit function.

6. Intersection of Opioids, Complement, and Neuroimmune Circuits

The strongly suggested correlation of the complement system to the OUD has led to a complicated interaction between the complement and neuro systems[

47,

48]. Due to the complement responses in neuro circuits, there have been significant effects observed in microglial, astrocyte, and synapses.

6.1. Microglial Function and Complement-Opioid Interactions

Microglia express complement receptors (CR3, C3aR, C5aR1)[

49] and respond robustly to C3a and C5a. Complement enhances chemotaxis, synaptic engulfment, and reactive cytokine profiles. Opioids potentiate microglial activation, suggesting that complement signaling may amplify opioid-induced synaptic and inflammatory changes.

6.2. Astrocyte Responses

Astrocytes respond to complement[

50] with increased GFAP expression, modulation of cytokines and chemokines, and altered neurotransmitter regulation (e.g., glutamate uptake). Opioids also modify astrocyte[

51] calcium dynamics and receptor expression, raising the possibility of convergent pathways that affect synaptic homeostasis.

6.3. Synaptic Effects

Complement-mediated synaptic tagging and elimination are established in development and disease[

52]. In addiction-relevant circuits, nucleus accumbens, prefrontal cortex, opioids and complement both influence dopamine signaling, excitatory/inhibitory balance and structural synaptic plasticity. Although direct mechanistic linkage remains under investigation, the available evidence points toward complement’s involvement in opioid-induced circuit remodeling.

7. Blood–Brain Barrier Mechanisms

Complement[

53] and opioids[

21] both regulate BBB function. The complement modulation on the BBB causes an upregulation on immune trafficking and therefore can be correlated to both thereaputic and harmful effects.

7.1. Complement and Opioid Effects on the BBB

C5a and MAC influence BBB integrity[

54] by modulating endothelial tight junctions, inducing inflammatory signaling, promoting leukocyte recruitment. Chronic opioids alter tight junction protein expression[

21], modify endothelial transporters, and increase immune cell trafficking.

7.2. Implications for Nanomedicine

Coexisting complement activation (e.g., nanoparticle-induced) and opioid-altered barrier properties may increase nanoparticle penetration into CNS tissues, an effect that could be harmful or therapeutically exploitable depending on context and timing. Some of the harmful effects due to the upregulation of BBB activity may be related to Alongside that some of the therapeutic effects of this upregulation may be

8. Complement-Targeted and Nanotechnology-Enabled Therapeutics

Potential Nanotechnology and complement targeted therapeutics for OUD have been hypothesized. The primary purpose of these therapeutics would be to control the cascade of complement related to OUD.

8.1. Complement Inhibitors

C3 inhibitors (e.g., compstatin analogs)[

55] block the central complement node, reducing C3a/C3b and downstream C5a/MAC. C5aR1 antagonists (e.g., PMX53, avacopan)[

56] reduce inflammatory leukocyte recruitment and astroglial activation. MAC inhibitors protect cells from sublytic stress. Although not yet tested specifically in OUD, their mechanisms align with pathways implicated in opioid-induced neuroinflammation.

8.2. Nanobodies as Complement Modulators

Nanobodies targeting C1q, C3b, or C5a provide high specificity[

57], can be engineered for BBB transcytosis, and achieve localized complement modulation with minimal systemic impact. Preclinical evidence in other inflammatory models supports their potential utility.

8.3. Complement-Aware Nanocarriers for CNS Drug Delivery

Nanoparticles can be engineered to evade complement[

13], deliver complement inhibitors to specific CNS regions, co-deliver opioids or OUD medications with immune modulators, and target inflamed endothelium or glia through ligand presentation. Such platforms could augment current OUD treatments by modulating neuroimmune drivers of tolerance, withdrawal, and relapse.

9. Future Directions

Key priorities include longitudinal human studies measuring complement proteins and function across OUD stages, development of human-derived organoid models to study complement/opioid/nanoparticle interactions, systematic characterization of protein coronas under conditions relevant to OUD, evaluation of complement inhibitors and nanobody-based therapies in OUD-relevant preclinical models, improved standardization of nanoparticle complement assays for regulatory and translational work.

10. Conclusions

Complement sits at a critical intersection of innate immunity, neuroinflammation, nanomedicine, and addiction neuroscience. Nanoparticles can activate multiple complement pathways, affecting safety and biodistribution. Chronic opioid exposure alters neuroimmune states and may modify complement activity in ways that influence BBB function, glial responses, and synaptic remodeling. Emerging strategies, including complement inhibitors, nanobody-based agents, and complement-conscious nanoparticle design offer promising avenues for improving CNS drug delivery and mitigating neuroinflammation in OUD. Continued integration of immunology, nanotechnology, and addiction biology is essential to advance these approaches toward clinical translation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization - Alexander and Mahajan, Original draft preparation- Mahajan, Das, Aalinkeel Writing - Singh, Jacob, Pullakad, and Alexander Figure - Singh and Alexander Review and editing – Alexander, Mahajan, Jacob.

Funding

No external funding was received for this work.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Merle, N.S.; Church, S.E.; Fremeaux-Bacchi, V.; Roumenina, L.T. Complement System Part I - Molecular Mechanisms of Activation and Regulation. Front Immunol 2015, 6, 262.

- Merle, N.S.; Noe, R.; Halbwachs-Mecarelli, L.; Fremeaux-Bacchi, V.; Roumenina, L.T. Complement System Part II: Role in Immunity. Front. Immunol. 2015, 6, 257. [CrossRef]

- Amarilyo, G.; Verbovetski, I.; Atallah, M.; Grau, A.; Wiser, G.; Gil, O.; Ben-Neriah, Y.; Mevorach, D. iC3b-opsonized apoptotic cells mediate a distinct anti-inflammatory response and transcriptional NF-kappaB-dependent blockade. Eur J Immunol 2010, 40, 699–709.

- Chen, J.Y.; Cortes, C.; Ferreira, V.P. Properdin: A multifaceted molecule involved in inflammation and diseases. Mol. Immunol. 2018, 102, 58–72. [CrossRef]

- King, B.C.; Kulak, K.; Colineau, L.; Blom, A.M. Outside in: Roles of complement in autophagy. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2020, 178, 2786–2801. [CrossRef]

- Alexander, J.J.; Anderson, A.J.; Barnum, S.R.; Stevens, B.; Tenner, A.J. The complement cascade: Yin-Yang in neuroinflammation--neuro-protection and -degeneration. J Neurochem 2008, 107, 1169–1187.

- Ayyubova, G.; Fazal, N. Beneficial versus Detrimental Effects of Complement–Microglial Interactions in Alzheimer’s Disease. Brain Sci. 2024, 14, 434. [CrossRef]

- Choudhury, M.E.; Miyanishi, K.; Takeda, H.; Islam, A.; Matsuoka, N.; Kubo, M.; Matsumoto, S.; Kunieda, T.; Nomoto, M.; Yano, H.; et al. Phagocytic elimination of synapses by microglia during sleep. Glia 2020, 68, 44–59. [CrossRef]

- Alawieh, A.; Elvington, A.; Tomlinson, S. Complement in the Homeostatic and Ischemic Brain. Front. Immunol. 2015, 6, 417. [CrossRef]

- van der Vlis, T.A.M.B.; Kros, J.M.; Mustafa, D.A.M.; van Wijck, R.T.A.; Ackermans, L.; van Hagen, P.M.; van der Spek, P.J. The complement system in glioblastoma multiforme. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2018, 6, 91. [CrossRef]

- Batista, A.F.; Khan, K.A.; Papavergi, M.-T.; Lemere, C.A. The Importance of Complement-Mediated Immune Signaling in Alzheimer’s Disease Pathogenesis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 817. [CrossRef]

- Wong, I.Y.; Bhatia, S.N.; Toner, M. Nanotechnology: emerging tools for biology and medicine. Genes Dev. 2013, 27, 2397–2408. [CrossRef]

- Haroon, H.B.; Dhillon, E.; Farhangrazi, Z.S.; Trohopoulos, P.N.; Simberg, D.; Moghimi, S.M. Activation of the complement system by nanoparticles and strategies for complement inhibition. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2023, 193, 227–240. [CrossRef]

- Fülöp, T.; Nemes, R.; Mészáros, T.; Urbanics, R.; Kok, R.J.; Jackman, J.A.; Cho, N.-J.; Storm, G.; Szebeni, J. Complement activation in vitro and reactogenicity of low-molecular weight dextran-coated SPIONs in the pig CARPA model: Correlation with physicochemical features and clinical information. J. Control. Release 2018, 270, 268–274. [CrossRef]

- Kosten, T.; George, T. The Neurobiology of Opioid Dependence: Implications for Treatment. Sci. Pr. Perspect. 2002, 1, 13–20. [CrossRef]

- Green, J.M.; Sundman, M.H.; Chou, Y.-H. Opioid-induced microglia reactivity modulates opioid reward, analgesia, and behavior. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2022, 135, 104544–104544. [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Chen, R.; Zhi, F.; Sheng, S.; Khiati, L.; Yang, Y.; Peng, Y.; Xia, Y. delta-opioid Receptor, Microglia and Neuroinflammation. Aging Dis 2023, 14, 778–793.

- Kruyer, A.; Scofield, M.D.; Wood, D.; Reissner, K.J.; Kalivas, P.W. Heroin Cue–Evoked Astrocytic Structural Plasticity at Nucleus Accumbens Synapses Inhibits Heroin Seeking. Biol. Psychiatry 2019, 86, 811–819. [CrossRef]

- Mahajan, S.D.; Schwartz, S.A.; Shanahan, T.C.; Chawda, R.P.; Nair, M.P. Morphine regulates gene expression of alpha- and beta-chemokines and their receptors on astroglial cells via the opioid mu receptor. J Immunol 2002, 169, 3589–3599.

- Stiene-Martin, A.; Mattson, M.P.; Hauser, K.F. Opiates selectively increase intracellular calcium in developing type-1 astrocytes: role of calcium in morphine-induced morphologic differentiation. Dev. Brain Res. 1993, 76, 189–196. [CrossRef]

- Chaves, C.; Remiao, F.; Cisternino, S.; Decleves, X. Opioids and the Blood-Brain Barrier: A Dynamic Interaction with Consequences on Drug Disposition in Brain. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2017, 15, 1156–1173. [CrossRef]

- Rus, H.; Cudrici, C.; Niculescu, F. C5b-9 complement complex in autoimmune demyelination and multiple sclerosis: Dual role in neuroinflammation and neuroprotection. Ann. Med. 2005, 37, 97–104. [CrossRef]

- Veerhuis, R.; Nielsen, H.M.; Tenner, A.J. Complement in the brain. Mol. Immunol. 2011, 48, 1592–1603. [CrossRef]

- Zipfel, P.F.; Skerka, C. Complement regulators and inhibitory proteins. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2009, 9, 729–740. [CrossRef]

- Jacob, A.; Alexander, J.J. Complement and blood–brain barrier integrity. Mol. Immunol. 2014, 61, 149–152. [CrossRef]

- Mahajan, S.; Jacob, A.; Kelkar, A.; Chang, A.; Mcskimming, D.; Neelamegham, S.; Quigg, R.J.; Alexander, J.J. Local complement factor H protects kidney endothelial cell structure and function. Kidney Int. 2021, 100, 824–836. [CrossRef]

- Davoust, N.; Nataf, S.; Holers, V.M.; Barnum, S.R. Expression of the murine complement regulatory protein Crry by glial cells and neurons. Glia 1999, 27, 162–170. [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, M.I.; Chu, S.-H.; Hernandez, M.X.; Fang, M.J.; Modarresi, L.; Selvan, P.; MacGregor, G.R.; Tenner, A.J. Cell-specific deletion of C1qa identifies microglia as the dominant source of C1q in mouse brain. J. Neuroinflammation 2017, 14, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Stevens, B.; Allen, N.J.; Vazquez, L.E.; Howell, G.R.; Christopherson, K.S.; Nouri, N.; Micheva, K.D.; Mehalow, A.K.; Huberman, A.D.; Stafford, B.; et al. The Classical Complement Cascade Mediates CNS Synapse Elimination. Cell 2007, 131, 1164–1178. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Ding, L.; Chen, H.; Zhang, M.; Ma, R.; Zheng, S.; Gong, J.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, H.; Xu, P.; et al. Cntnap4 partial deficiency exacerbates α-synuclein pathology through astrocyte–microglia C3-C3aR pathway. Cell Death Dis. 2023, 14, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Negro-Demontel, L.; Maleki, A.F.; Reich, D.S.; Kemper, C. The complement system in neurodegenerative and inflammatory diseases of the central nervous system. Front. Neurol. 2024, 15, 1396520. [CrossRef]

- Orsini, F.; De Blasio, D.; Zangari, R.; Zanier, E.R.; De Simoni, M.-G. Versatility of the complement system in neuroinflammation, neurodegeneration and brain homeostasis. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2014, 8, 380–380. [CrossRef]

- Farkas, I.; Takahashi, M.; Fukuda, A.; Yamamoto, N.; Akatsu, H.; Baranyi, L.; Tateyama, H.; Yamamoto, T.; Okada, N.; Okada, H. Complement C5a Receptor-Mediated Signaling May Be Involved in Neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Immunol. 2003, 170, 5764–5771. [CrossRef]

- Mahajan, S.D.; Tutino, V.M.; Redae, Y.; Meng, H.; Siddiqui, A.; Woodruff, T.M.; Jarvis, J.N.; Hennon, T.; Schwartz, S.; Quigg, R.J.; et al. C5a induces caspase-dependent apoptosis in brain vascular endothelial cells in experimental lupus. Immunology 2016, 148, 407–419. [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Wang, G.; Griffin, J.I.; Brenneman, B.; Banda, N.K.; Holers, V.M.; Backos, D.S.; Wu, L.; Moghimi, S.M.; Simberg, D. Complement proteins bind to nanoparticle protein corona and undergo dynamic exchange in vivo. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2016, 12, 387–393. [CrossRef]

- La-Beck, N.M.; Islam, R.; Markiewski, M.M. Nanoparticle-Induced Complement Activation: Implications for Cancer Nanomedicine. Front. Immunol. 2021, 11. [CrossRef]

- Tavano, R.; Gabrielli, L.; Lubian, E.; Fedeli, C.; Visentin, S.; De Laureto, P.P.; Arrigoni, G.; Geffner-Smith, A.; Chen, F.; Simberg, D.; et al. C1q-Mediated Complement Activation and C3 Opsonization Trigger Recognition of Stealth Poly(2-methyl-2-oxazoline)-Coated Silica Nanoparticles by Human Phagocytes. ACS Nano 2018, 12, 5834–5847. [CrossRef]

- Moghimi, S.M.; Hamad, I. Liposome-Mediated Triggering of Complement Cascade. J. Liposome Res. 2008, 18, 195–209. [CrossRef]

- Yang, A.; Liu, W.; Li, Z.; Jiang, L.; Xu, H.; Yang, X. Influence of Polyethyleneglycol Modification on Phagocytic Uptake of Polymeric Nanoparticles Mediated by Immunoglobulin G and Complement Activation. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2010, 10, 622–628. [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.-Y.; Hai, X.; Wang, Y.-T.; Shu, Y.; Chen, X.-W.; Wang, J.-H. Core–Corona Magnetic Nanospheres Functionalized with Zwitterionic Polymer Ionic Liquid for Highly Selective Isolation of Glycoprotein. Biomacromolecules 2017, 19, 53–61. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Hood, E.D.; Nong, J.; Ding, J.; Marcos-Contreras, O.A.; Glassman, P.M.; Rubey, K.M.; Zaleski, M.; Espy, C.L.; Gullipali, D.; et al. Combating Complement's Deleterious Effects on Nanomedicine by Conjugating Complement Regulatory Proteins to Nanoparticles. Adv. Mater. 2022, 34, 2107070–e2107070. [CrossRef]

- Welters, I.; Menzebach, A.; Goumon, Y.; Langefeld, T.; Teschemacher, H.; Hempelmann, G.; Stefano, G. Morphine suppresses complement receptor expression, phagocytosis, and respiratory burst in neutrophils by a nitric oxide and μ3 opiate receptor-dependent mechanism. J. Neuroimmunol. 2000, 111, 139–145. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, K.B.; Light, A.R.; Odell, D.W.; Stuart, A.R.; Radtke, J.; Light, K.C. Observation of Complement Protein Gene Expression Before and After Surgery in Opioid-Consuming and Opioid-Naive Patients. Anesthesia Analg. 2018, 132, e1–e5. [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.-J.; Ji, R.-R. Targeting Astrocyte Signaling for Chronic Pain. Neurotherapeutics 2010, 7, 482–493. [CrossRef]

- Lian, H.; Litvinchuk, A.; Chiang, A.C.-A.; Aithmitti, N.; Jankowsky, J.L.; Zheng, H. Astrocyte-Microglia Cross Talk through Complement Activation Modulates Amyloid Pathology in Mouse Models of Alzheimer's Disease. J. Neurosci. 2016, 36, 577–589. [CrossRef]

- Tillmon, H.; Soteros, B.M.; Shen, L.; Cong, Q.; Wollet, M.; General, J.; Chin, H.; Lee, J.B.; Carreno, F.R.; Morilak, D.A.; et al. Complement and microglia activation mediate stress-induced synapse loss in layer 2/3 of the medial prefrontal cortex in male mice. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 1–17. [CrossRef]

- Vygonskaya, M.; Wu, Y.; Price, T.J.; Chen, Z.; Smith, M.T.; Klyne, D.M.; Han, F.Y. The role and treatment potential of the complement pathway in chronic pain. J. Pain 2024, 27, 104689. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.-H.; Jin, H.; Xu, J.-S.; Guo, G.-Q.; Chen, D.-L.; Bo, Y. Complement factor C5a and C5a receptor contribute to morphine tolerance and withdrawal-induced hyperalgesia in rats. Exp. Ther. Med. 2012, 4, 723–727. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Chu, J.M.T.; Chang, R.C.C.; Wong, G.T.C. The Complement System in the Central Nervous System: From Neurodevelopment to Neurodegeneration. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 337. [CrossRef]

- Pekna, M.; Pekny, M. The Complement System: A Powerful Modulator and Effector of Astrocyte Function in the Healthy and Diseased Central Nervous System. Cells 2021, 10, 1812. [CrossRef]

- Hauser, K.F.; Harris-White, M.E.; Jackson, J.A.; Opanashuk, L.A.; Carney, J.M. Opioids Disrupt Ca2+Homeostasis and Induce Carbonyl Oxyradical Production in Mouse Astrocytesin Vitro:Transient Increases and Adaptation to Sustained Exposure. Exp. Neurol. 1998, 151, 70–76. [CrossRef]

- Stevens, B.; Johnson, M.B. The complement cascade repurposed in the brain. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2021, 21, 624–625. [CrossRef]

- Jacob, A.; Hack, B.; Chen, P.; Quigg, R.J.; Alexander, J.J. C5a/CD88 signaling alters blood-brain barrier integrity in lupus through nuclear factor-kappaB. J Neurochem 2011, 119, 1041–1051.

- A Flierl, M.; Stahel, P.F.; Rittirsch, D.; Huber-Lang, M.; Niederbichler, A.D.; Hoesel, L.M.; Touban, B.M.; Morgan, S.J.; Smith, W.R.; A Ward, P.; et al. Inhibition of complement C5a prevents breakdown of the blood-brain barrier and pituitary dysfunction in experimental sepsis. Crit. Care 2009, 13, R12–R12. [CrossRef]

- Ricklin, D.; Lambris, J.D. Compstatin: a complement inhibitor on its way to clinical application. Adv Exp Med Biol 2008, 632, 273–292.

- Ennis, D.; Yeung, R.S.; Pagnoux, C. Long-term use and remission of granulomatosis with polyangiitis with the oral C5a receptor inhibitor avacopan. BMJ Case Rep. 2020, 13, e236236. [CrossRef]

- Zarantonello, A.; Pedersen, H.; Laursen, N.S.; Andersen, G.R. Nanobodies Provide Insight into the Molecular Mechanisms of the Complement Cascade and Offer New Therapeutic Strategies. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 298. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |