Submitted:

12 June 2025

Posted:

13 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Whole-Body Inhalation Exposure of Rats to Sham air, Naphthalene, or Carbon Black with Naphthalene

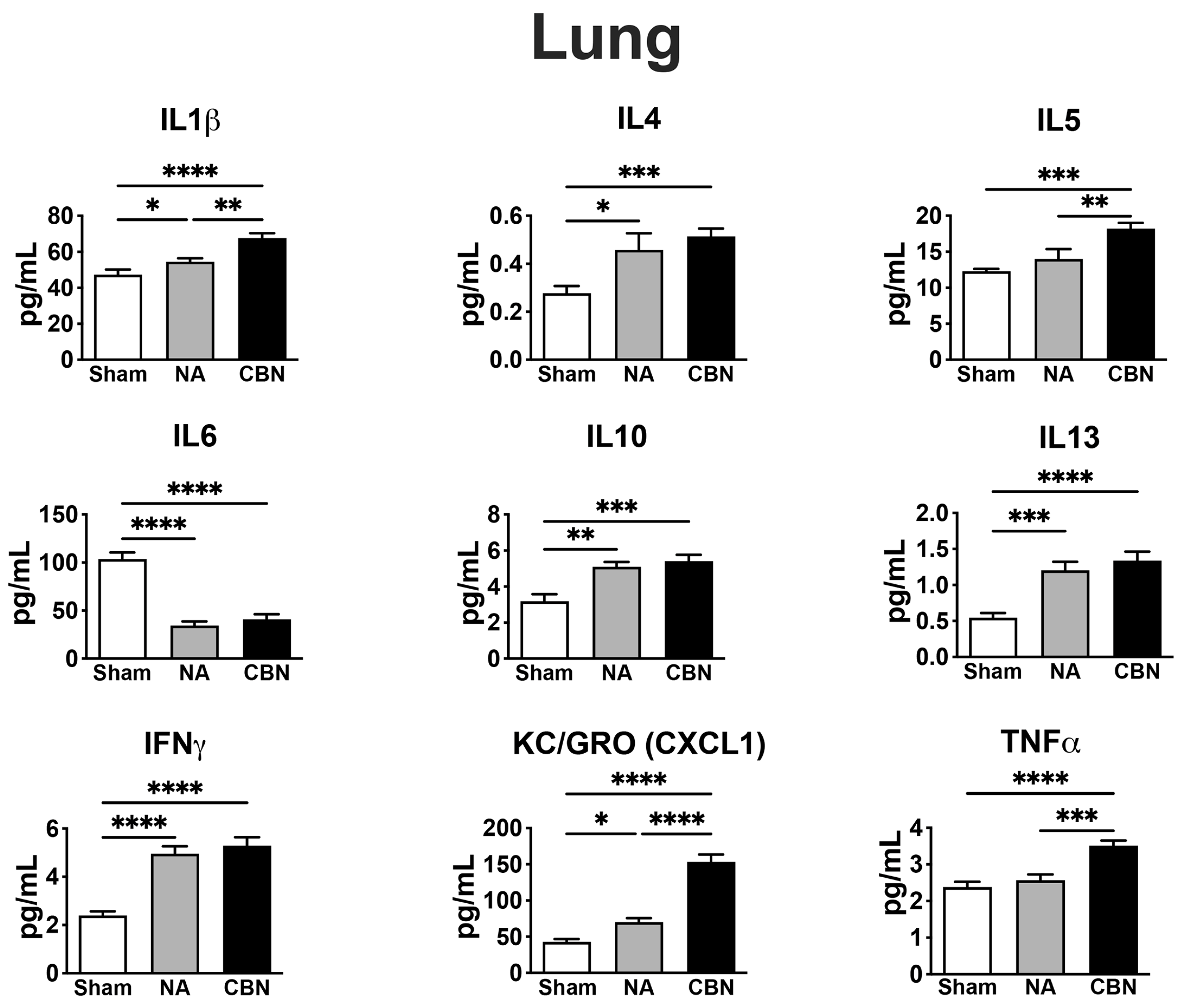

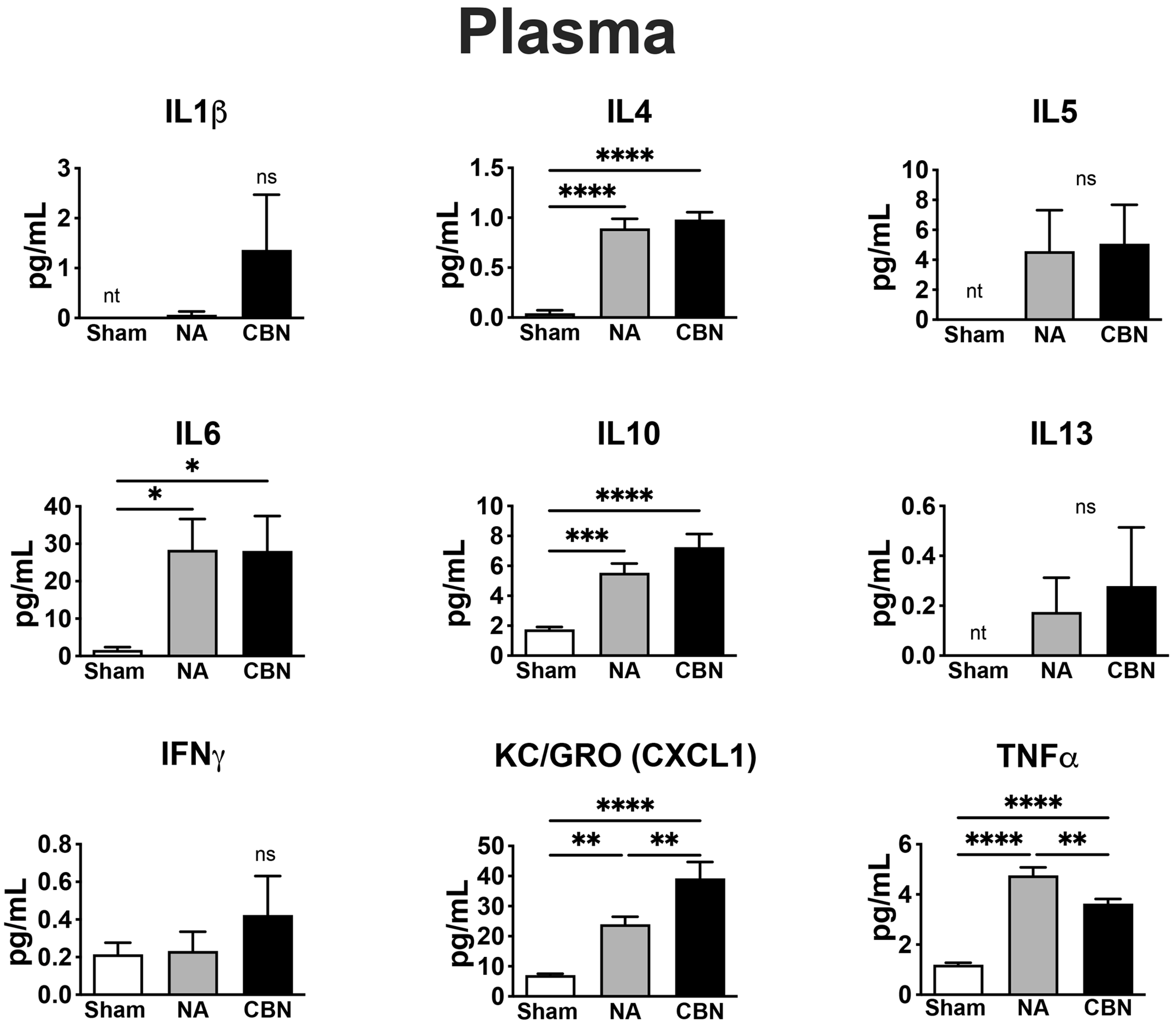

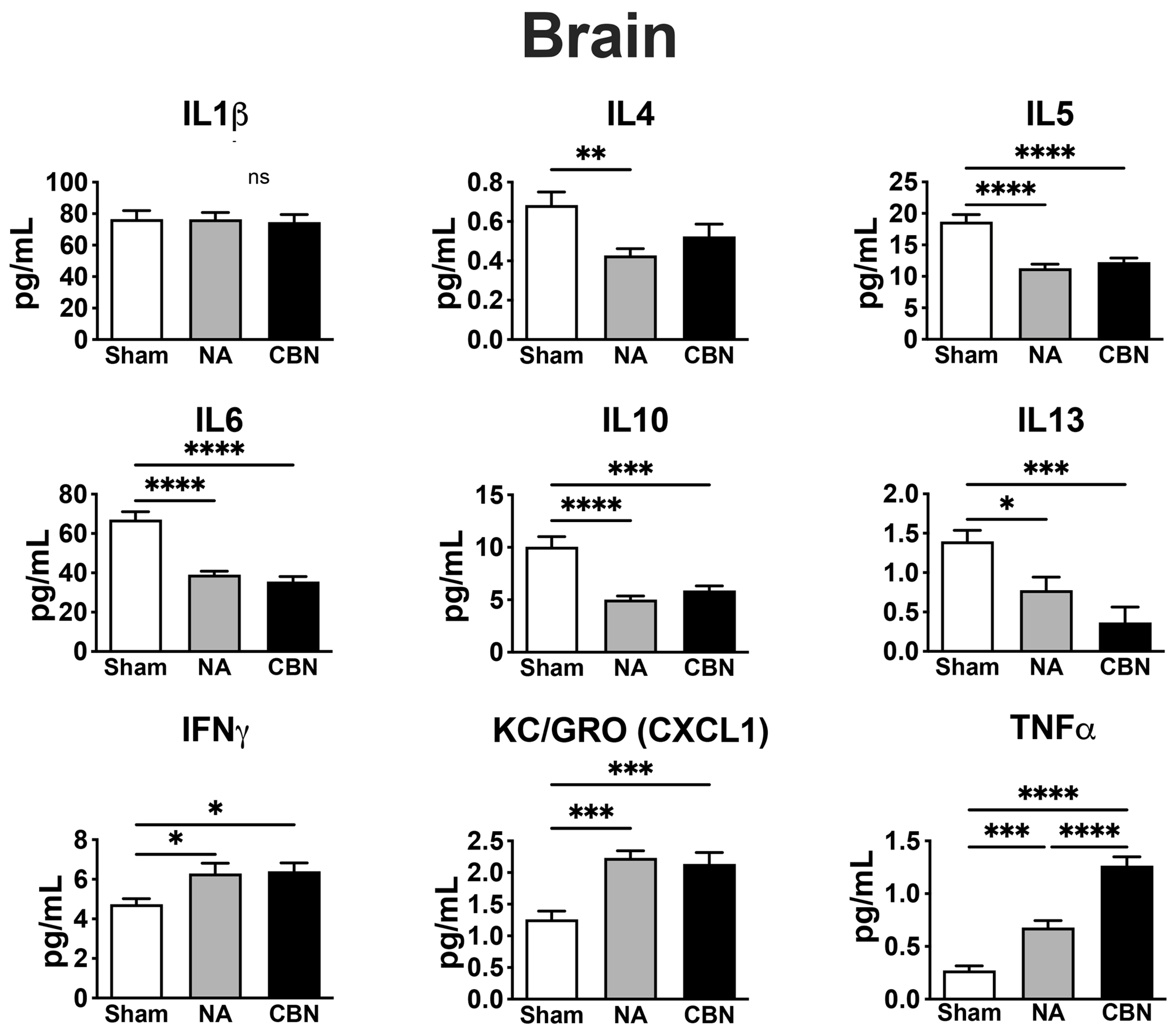

2.2. Biomarkers of Inflammation

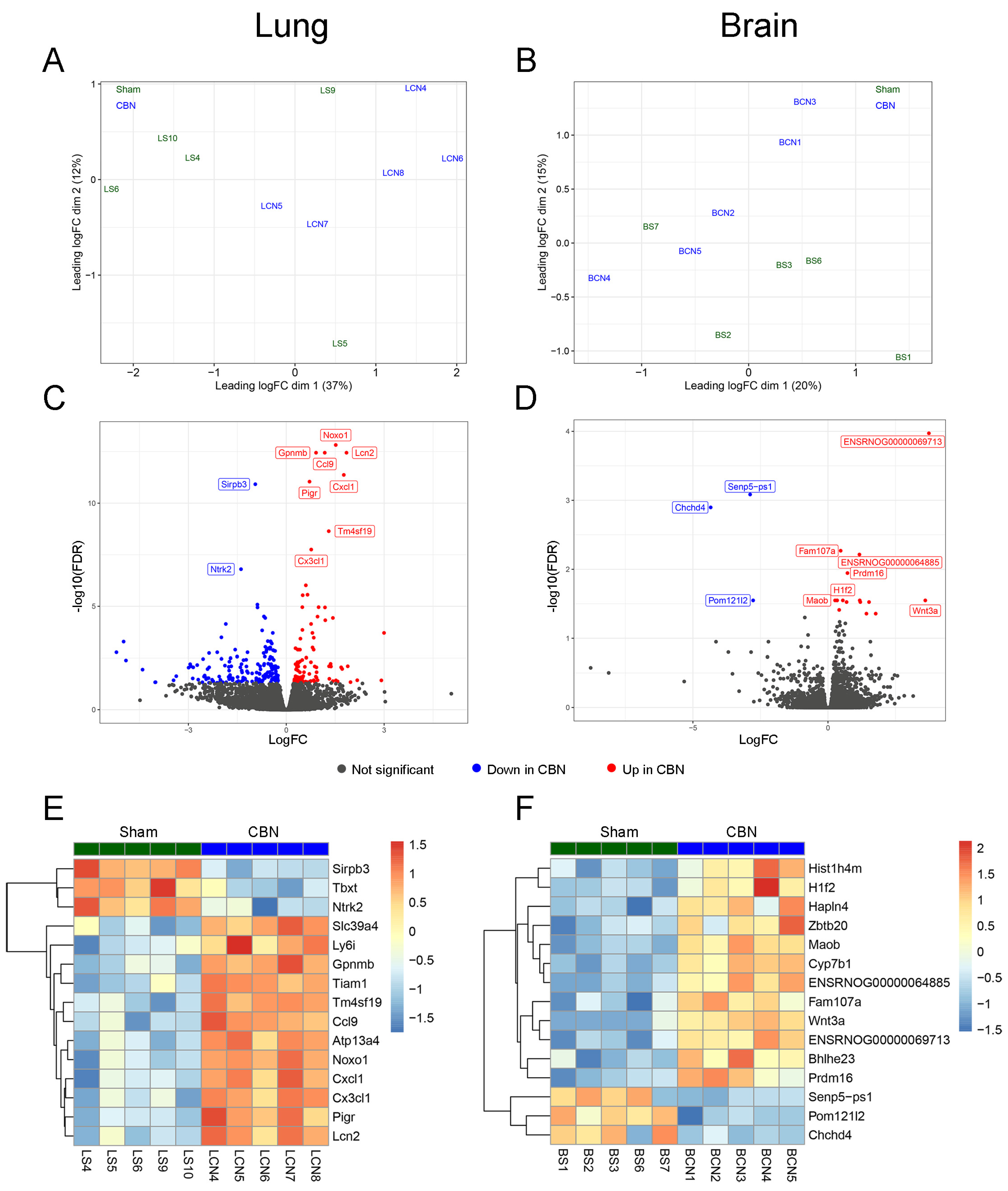

2.3. Sample Preparation and Next-Generation Sequencing

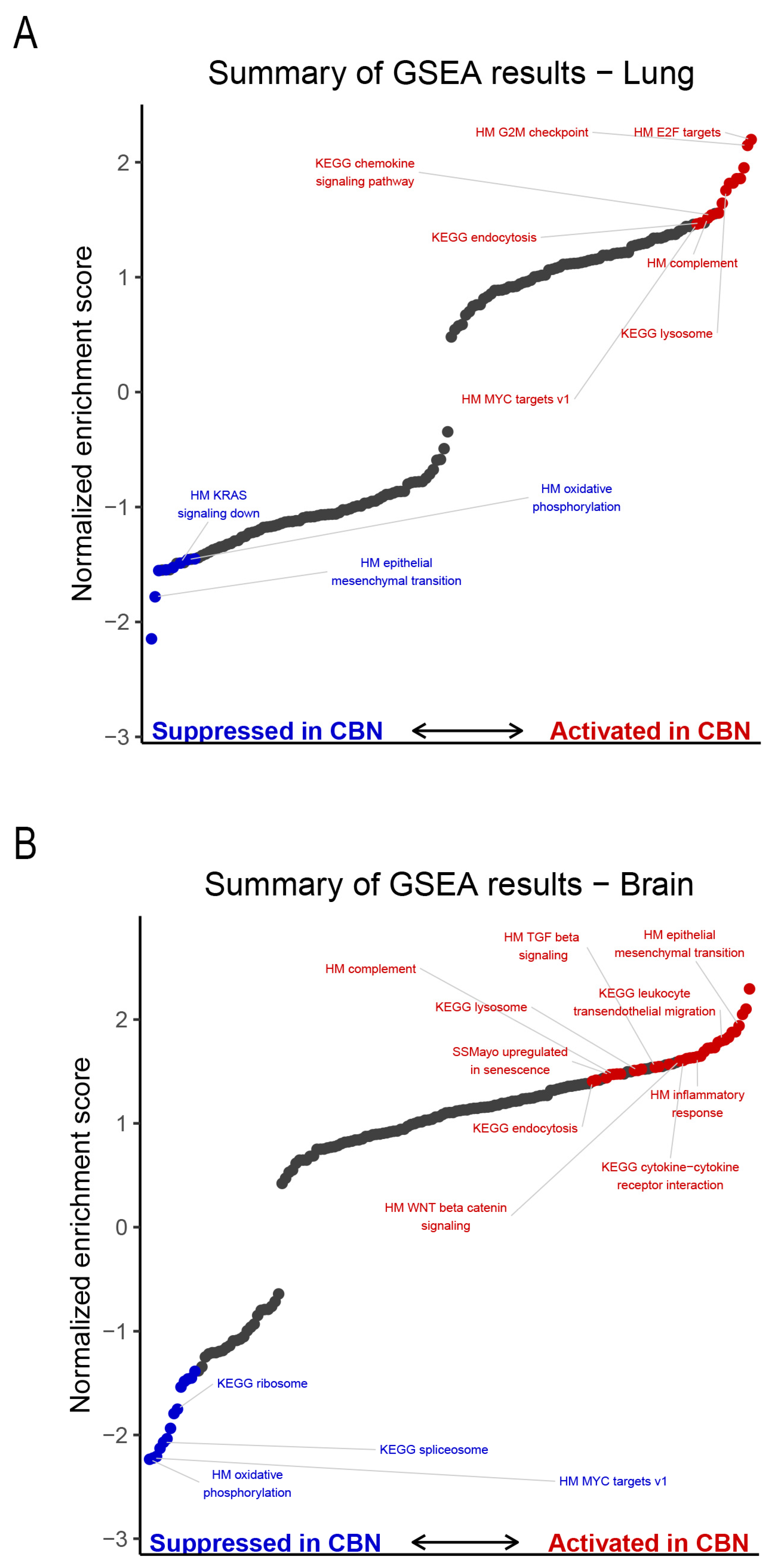

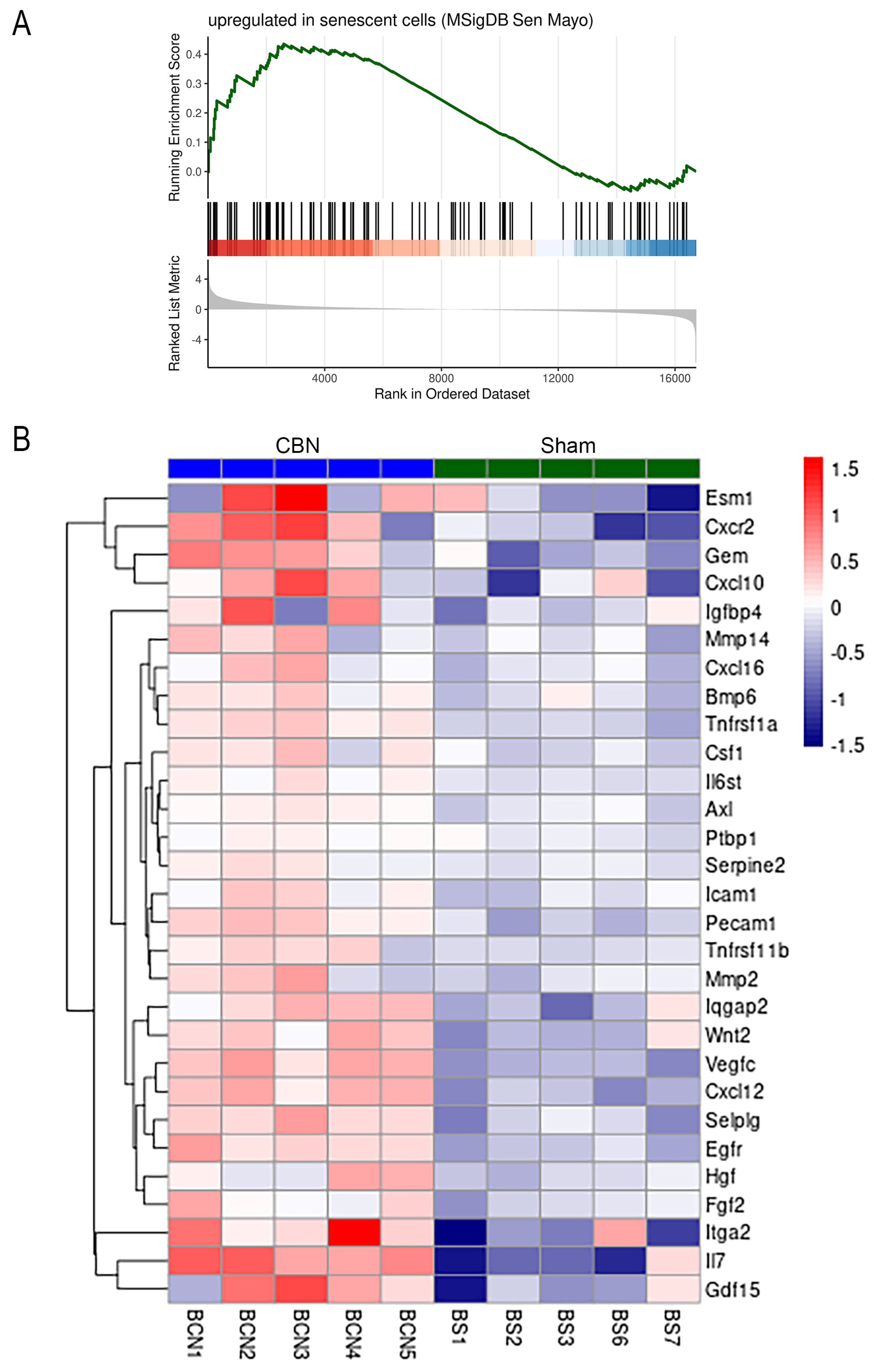

2.4. Gene Set Enrichment Analysis

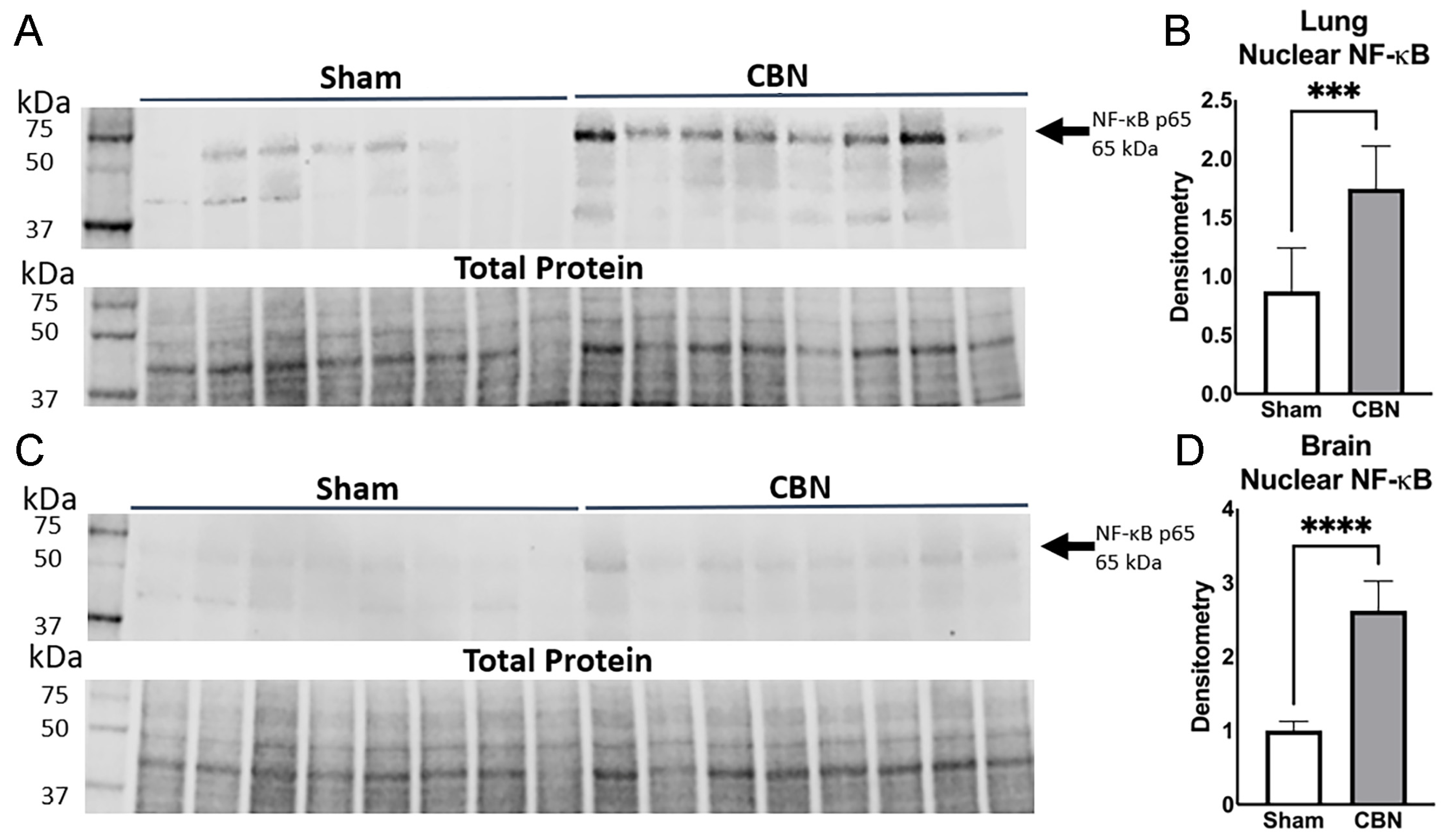

2.5. NF-κB Activation in Lung and Brain Following CBN Inhalation Exposure

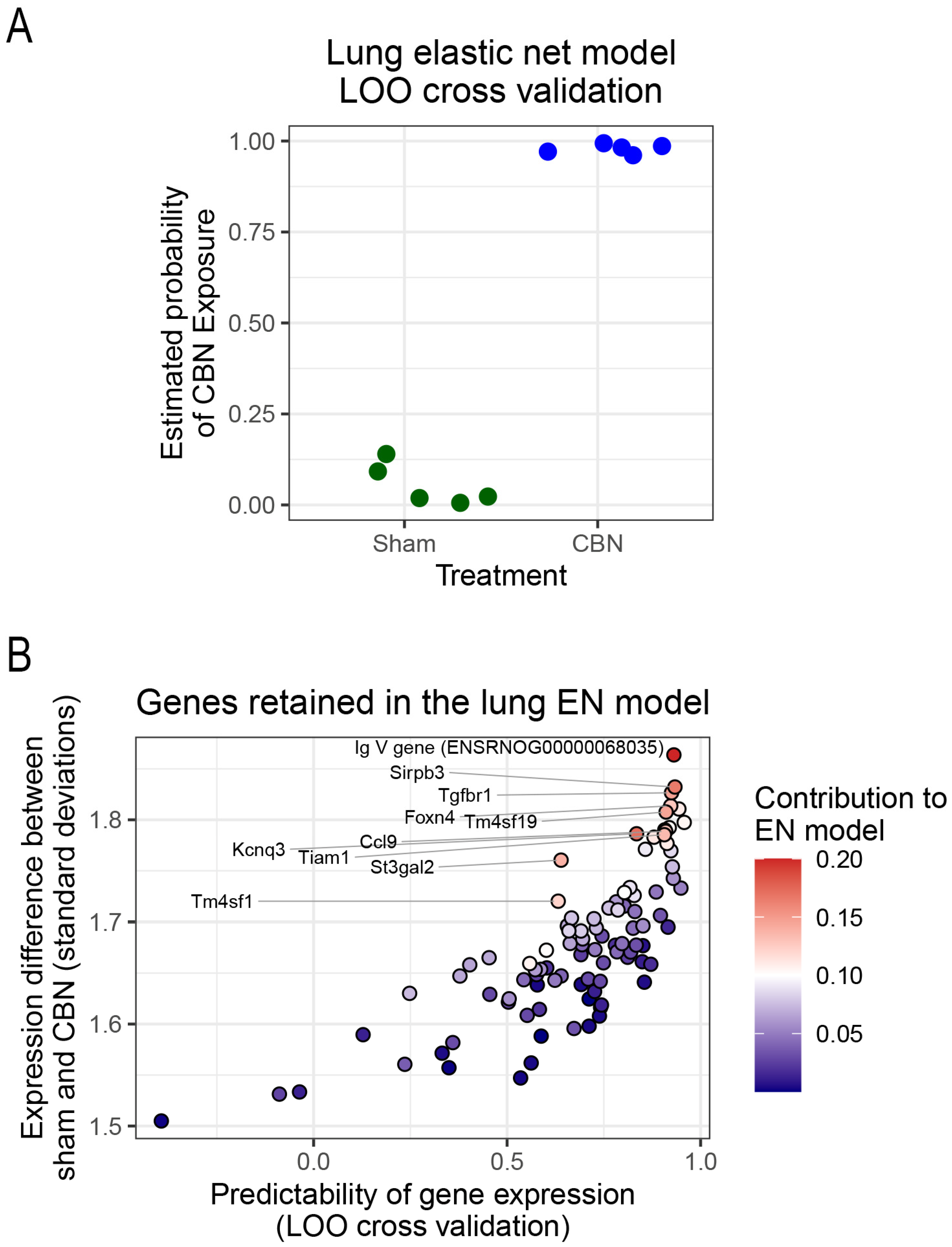

2.6. Predictive Modeling Using Elastic Net

3. Discussion

3.1. Limitations

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Experimental Animals

4.2. Ethics

4.3. Whole Body Inhalation Exposure

4.4. Preparation of Naphthalene Vapor and Carbon Black Aerosols

4.5. Tissue Collection and Processing

4.6. Inflammation Panel

4.7. Western Blot Analysis

4.8. Data Analysis

4.9. RNA Sequencing

4.10. Differential Gene Expression Analysis

4.11. Gene Set Enrichment Analysis

4.12. Predictive Modeling Using Elastic Net

4.13. Availability of Data and Materials

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AD | Alzheimer’s disease |

| BP GO | Biological process gene ontology |

| CB | Carbon black powder |

| CBN | Carbon black nanoparticles and naphthalene vapor |

| ConB | Constrictive bronchiolitis |

| DEGs | Differentially expressed genes |

| DRRD | Deployment-Related Respiratory Diseases |

| ELP | Electrical low-pressure impactor |

| EMT | Epithelial to mesenchymal transition |

| FDR | False discovery rate |

| GEO | Gene Expression Omnibus |

| GSEA | Gene Set Enrichment Analysis |

| HPAG | High-pressure acoustical generator |

| LOO | Leave-one-out |

| LR | Likelihood ratio |

| MFC | Mass flow controller |

| MSD | Meso Scale Discovery |

| MSI | Minnesota Supercomputing Institute |

| NIH | National Institutes of Health |

| PD | Parkinson’s disease |

| PM | Particulate matter |

| PM2.5 | Particulate matter < 2.5 microns |

| QLF | Quasi-likelihood F |

| RI | Research Informatics |

| RIN | RNA integrity number |

| RNA-seq | RNA sequencing |

| rRNA | Ribosomal RNA |

| VOCs | Volatile organic compounds |

References

- Hirzel, K.L.; Balmer, J. Airborne Hazards and Open Burn Pit Exposures. Workplace Health Saf 2023, 71, 352. [CrossRef]

- Trembley, J.H.; Barach, P.; Tomaska, J.M.; Poole, J.T.; Ginex, P.K.; Miller, R.F.; Lindheimer, J.B.; Szema, A.M.; Gandy, K.; Siddharthan, T.; et al. Current understanding of the impact of United States military airborne hazards and burn pit exposures on respiratory health. Part Fibre Toxicol 2024, 21, 43. [CrossRef]

- National Academies, S.; Engineering; Health; Medicine, D.; Board on Population, H.; Public Health, P.; Committee on the Respiratory Health Effects of Airborne Hazards Exposures in the Southwest Asia Theater of Military, O. Respiratory Health Effects of Airborne Hazards Exposures in the Southwest Asia Theater of Military Operations 2020. [CrossRef]

- Hoisington, A.J.; Stearns-Yoder, K.A.; Kovacs, E.J.; Postolache, T.T.; Brenner, L.A. Airborne Exposure to Pollutants and Mental Health: A Review with Implications for United States Veterans. Curr Environ Health Rep 2024, 11, 168-183. [CrossRef]

- Penuelas, V.L.; Lo, D.D. Burn pit exposure in military personnel and the potential resulting lung and neurological pathologies. Frontiers in Environmental Health 2024, 3. [CrossRef]

- Perveen, M.M.; Mayo-Malasky, H.E.; Lee-Wong, M.F.; Tomaska, J.M.; Forsyth, E.; Gravely, A.; Klein, M.A.; Trembley, J.H.; Butterick, T.A.; Promisloff, R.A.; et al. Gross Hematuria and Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms Associated With Military Burn Pits Exposures in US Veterans Deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan. J Occup Environ Med 2023, 65, 740-744. [CrossRef]

- Savitz, D.A.; Woskie, S.R.; Bello, A.; Gaither, R.; Gasper, J.; Jiang, L.; Rennix, C.; Wellenius, G.A.; Trivedi, A.N. Deployment to Military Bases With Open Burn Pits and Respiratory and Cardiovascular Disease. JAMA Netw Open 2024, 7, e247629. [CrossRef]

- Brooks, A.W.; Sandri, B.J.; Nixon, J.P.; Nurkiewicz, T.R.; Barach, P.; Trembley, J.H.; Butterick, T.A. Neuroinflammation and Brain Health Risks in Veterans Exposed to Burn Pit Toxins. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25, 9759. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Doherty, T.A.; James, C. Military burn pit exposure and airway disease: Implications for our Veteran population. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2023, 131, 720-725. [CrossRef]

- Masiol, M.; Mallon, C.T.; Haines, K.M., Jr.; Utell, M.J.; Hopke, P.K. Airborne Dioxins, Furans, and Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons Exposure to Military Personnel in Iraq. J Occup Environ Med 2016, 58, S22-30. [CrossRef]

- Woodall, B.D.; Yamamoto, D.P.; Gullett, B.K.; Touati, A. Emissions from small-scale burns of simulated deployed U.S. military waste. Environ Sci Technol 2012, 46, 10997-11003. [CrossRef]

- Aurell, J.; Gullett, B.K.; Yamamoto, D. Emissions from open burning of simulated military waste from forward operating bases. Environ Sci Technol 2012, 46, 11004-11012. [CrossRef]

- Blasch, K.W.; Kolivosky, J.E.; Heller, J.M. Environmental Air Sampling Near Burn Pit and Incinerator Operations at Bagram Airfield, Afghanistan. J Occup Environ Med 2016, 58, S38-43. [CrossRef]

- Engelbrecht, J.P.; McDonald, E.V.; Gillies, J.A.; Jayanty, R.K.; Casuccio, G.; Gertler, A.W. Characterizing mineral dusts and other aerosols from the Middle East--Part 2: grab samples and re-suspensions. Inhal Toxicol 2009, 21, 327-336. [CrossRef]

- Falvo, M.J.; Sotolongo, A.M.; Osterholzer, J.J.; Robertson, M.W.; Kazerooni, E.A.; Amorosa, J.K.; Garshick, E.; Jones, K.D.; Galvin, J.R.; Kreiss, K.; et al. Consensus Statements on Deployment-Related Respiratory Disease, Inclusive of Constrictive Bronchiolitis: A Modified Delphi Study. Chest 2023, 163, 599-609. [CrossRef]

- Trembley, J.H.; So, S.W.; Nixon, J.P.; Bowdridge, E.C.; Garner, K.L.; Griffith, J.; Engles, K.J.; Batchelor, T.P.; Goldsmith, W.T.; Tomaska, J.M.; et al. Whole-body inhalation of nano-sized carbon black: a surrogate model of military burn pit exposure. BMC Res Notes 2022, 15, 275. [CrossRef]

- Block, M.L.; Calderon-Garciduenas, L. Air pollution: mechanisms of neuroinflammation and CNS disease. Trends Neurosci 2009, 32, 506-516. [CrossRef]

- Hoisington, L.; Lowry, C.A.; McDonald, L.T.; Krefft, S.D.; Rose, C.S.; Kovacs, E.J.; Brenner, L.A. First Annual PACT Act Research Symposium on Veterans Health: A Colorado PACT Act Collaboration (CoPAC) Initiative. Mil Med 2024, 189, 80-84. [CrossRef]

- Heusinkveld, H.J.; Wahle, T.; Campbell, A.; Westerink, R.H.S.; Tran, L.; Johnston, H.; Stone, V.; Cassee, F.R.; Schins, R.P.F. Neurodegenerative and neurological disorders by small inhaled particles. Neurotoxicology 2016, 56, 94-106. [CrossRef]

- Gutor, S.S.; Richmond, B.W.; Du, R.H.; Wu, P.; Lee, J.W.; Ware, L.B.; Shaver, C.M.; Novitskiy, S.V.; Johnson, J.E.; Newman, J.H.; et al. Characterization of Immunopathology and Small Airway Remodeling in Constrictive Bronchiolitis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2022, 206, 260-270. [CrossRef]

- Trageser, K.J.; Sebastian-Valverde, M.; Naughton, S.X.; Pasinetti, G.M. The Innate Immune System and Inflammatory Priming: Potential Mechanistic Factors in Mood Disorders and Gulf War Illness. Front Psychiatry 2020, 11, 704. [CrossRef]

- Garshick, E.; Abraham, J.H.; Baird, C.P.; Ciminera, P.; Downey, G.P.; Falvo, M.J.; Hart, J.E.; Jackson, D.A.; Jerrett, M.; Kuschner, W.; et al. Respiratory Health after Military Service in Southwest Asia and Afghanistan. An Official American Thoracic Society Workshop Report. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2019, 16, e1-e16. [CrossRef]

- Nurkiewicz, T.R.; Porter, D.W.; Hubbs, A.F.; Stone, S.; Chen, B.T.; Frazer, D.G.; Boegehold, M.A.; Castranova, V. Pulmonary nanoparticle exposure disrupts systemic microvascular nitric oxide signaling. Toxicol Sci 2009, 110, 191-203. [CrossRef]

- Command, U.S.A.P.H. Screening Health Risk Assessments, Joint Base Balad, Iraq, 11 May–19 June 2009; U.S. Army Center for Health Promotion and Preventive Medicine: Aberdeen Proving Ground, MD, July 2010.

- Buckpitt, A.; Boland, B.; Isbell, M.; Morin, D.; Shultz, M.; Baldwin, R.; Chan, K.; Karlsson, A.; Lin, C.; Taff, A.; et al. Naphthalene-induced respiratory tract toxicity: metabolic mechanisms of toxicity. Drug Metab Rev 2002, 34, 791-820. [CrossRef]

- Ganter, M.T.; Roux, J.; Miyazawa, B.; Howard, M.; Frank, J.A.; Su, G.; Sheppard, D.; Violette, S.M.; Weinreb, P.H.; Horan, G.S.; et al. Interleukin-1β Causes Acute Lung Injury via αvβ5 and αvβ6 Integrin–Dependent Mechanisms. Circulation Research 2008, 102, 804-812, doi:doi:10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.161067.

- Hill, W.; Lim, E.L.; Weeden, C.E.; Lee, C.; Augustine, M.; Chen, K.; Kuan, F.C.; Marongiu, F.; Evans, E.J., Jr.; Moore, D.A.; et al. Lung adenocarcinoma promotion by air pollutants. Nature 2023, 616, 159-167. [CrossRef]

- Piao, C.H.; Fan, Y.; Nguyen, T.V.; Song, C.H.; Kim, H.T.; Chai, O.H. PM2.5 exposure regulates Th1/Th2/Th17 cytokine production through NF-κB signaling in combined allergic rhinitis and asthma syndrome. Int Immunopharmacol 2023, 119, 110254. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, Y.; Liang, Z.; Jia, S.; Liu, Y.; Li, J.; Liu, J.; Shi, J.; Yuan, P.; Zhu, J.; et al. Plasma IL4 Levels Linked to Pulmonary Hypertension Severity and Outcome. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 2025, 52, e70040. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Tumes, D.J.; Hercus, T.R.; Yip, K.H.; Aloe, C.; Vlahos, R.; Lopez, A.F.; Wilson, N.; Owczarek, C.M.; Bozinovski, S. Blocking the human common beta subunit of the GM-CSF, IL-5 and IL-3 receptors markedly reduces hyperinflammation in ARDS models. Cell Death Dis 2022, 13, 137. [CrossRef]

- Liva, S.M.; de Vellis, J. IL-5 induces proliferation and activation of microglia via an unknown receptor. Neurochem Res 2001, 26, 629-637. [CrossRef]

- Voiriot, G.; Razazi, K.; Amsellem, V.; Tran Van Nhieu, J.; Abid, S.; Adnot, S.; Mekontso Dessap, A.; Maitre, B. Interleukin-6 displays lung anti-inflammatory properties and exerts protective hemodynamic effects in a double-hit murine acute lung injury. Respiratory Research 2017, 18, 64. [CrossRef]

- Kopf, M.; Baumann, H.; Freer, G.; Freudenberg, M.; Lamers, M.; Kishimoto, T.; Zinkernagel, R.; Bluethmann, H.; Köhler, G. Impaired immune and acute-phase responses in interleukin-6-deficient mice. Nature 1994, 368, 339-342. [CrossRef]

- Duque Ede, A.; Munhoz, C.D. The Pro-inflammatory Effects of Glucocorticoids in the Brain. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2016, 7, 78. [CrossRef]

- Frieler, R.A.; Meng, H.; Duan, S.Z.; Berger, S.; Schütz, G.; He, Y.; Xi, G.; Wang, M.M.; Mortensen, R.M. Myeloid-specific deletion of the mineralocorticoid receptor reduces infarct volume and alters inflammation during cerebral ischemia. Stroke 2011, 42, 179-185. [CrossRef]

- Ware, L.B.; Matthay, M.A. The acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med 2000, 342, 1334-1349. [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Qian, X.; Xing, J.; Wang, J.; Sun, Y.; Wang, Q.g.; Li, H. Particulate Matter Triggers Depressive-Like Response Associated With Modulation of Inflammatory Cytokine Homeostasis and Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor Signaling Pathway in Mice. Toxicological Sciences 2018, 164, 278-288. [CrossRef]

- Brombacher, T.M.; Nono, J.K.; De Gouveia, K.S.; Makena, N.; Darby, M.; Womersley, J.; Tamgue, O.; Brombacher, F. IL-13-Mediated Regulation of Learning and Memory. J Immunol 2017, 198, 2681-2688. [CrossRef]

- Hershey, G.K.K. IL-13 receptors and signaling pathways: An evolving web. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 2003, 111, 677-690. [CrossRef]

- Allouche, J.; Cremoni, M.; Brglez, V.; Graça, D.; Benzaken, S.; Zorzi, K.; Fernandez, C.; Esnault, V.; Levraut, M.; Oppo, S.; et al. Air pollution exposure induces a decrease in type II interferon response: A paired cohort study. EBioMedicine 2022, 85, 104291. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Lin, B.; Hao, D.; Du, Z.; Wang, Q.; Song, Z.; Li, X.; Li, K.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Q.; et al. Short-term PM(2.5) exposure induces transient lung injury and repair. J Hazard Mater 2023, 459, 132227. [CrossRef]

- Kayalar, Ö.; Rajabi, H.; Konyalilar, N.; Mortazavi, D.; Aksoy, G.T.; Wang, J.; Bayram, H. Impact of particulate air pollution on airway injury and epithelial plasticity; underlying mechanisms. Front Immunol 2024, 15, 1324552. [CrossRef]

- Erickson, M.A.; Jude, J.; Zhao, H.; Rhea, E.M.; Salameh, T.S.; Jester, W.; Pu, S.; Harrowitz, J.; Nguyen, N.; Banks, W.A.; et al. Serum amyloid A: an ozone-induced circulating factor with potentially important functions in the lung-brain axis. Faseb j 2017, 31, 3950-3965. [CrossRef]

- McCarrick, S.; Malmborg, V.; Gren, L.; Danielsen, P.H.; Tunér, M.; Palmberg, L.; Broberg, K.; Pagels, J.; Vogel, U.; Gliga, A.R. Pulmonary exposure to renewable diesel exhaust particles alters protein expression and toxicity profiles in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid and plasma of mice. Arch Toxicol 2025, 99, 797-814. [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, A.; Payton, A.; Gallant, S.C.; Rogers, K.L., Jr.; Mascenik, T.; Hickman, E.; Love, C.A.; Schichlein, K.D.; Smyth, T.R.; Kim, Y.H.; et al. Burn Pit Smoke Condensate-Mediated Toxicity in Human Airway Epithelial Cells. Chem Res Toxicol 2024, 37, 791-803. [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.H.; Warren, S.H.; Kooter, I.; Williams, W.C.; George, I.J.; Vance, S.A.; Hays, M.D.; Higuchi, M.A.; Gavett, S.H.; DeMarini, D.M.; et al. Chemistry, lung toxicity and mutagenicity of burn pit smoke-related particulate matter. Part Fibre Toxicol 2021, 18, 45. [CrossRef]

- Block, M.L.; Zecca, L.; Hong, J.S. Microglia-mediated neurotoxicity: uncovering the molecular mechanisms. Nat Rev Neurosci 2007, 8, 57-69. [CrossRef]

- Marín-Palma, D.; Fernandez, G.J.; Ruiz-Saenz, J.; Taborda, N.A.; Rugeles, M.T.; Hernandez, J.C. Particulate matter impairs immune system function by up-regulating inflammatory pathways and decreasing pathogen response gene expression. Scientific Reports 2023, 13, 12773. [CrossRef]

- Shukla, A.; Timblin, C.; BeruBe, K.; Gordon, T.; McKinney, W.; Driscoll, K.; Vacek, P.; Mossman, B.T. Inhaled particulate matter causes expression of nuclear factor (NF)-kappaB-related genes and oxidant-dependent NF-kappaB activation in vitro. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2000, 23, 182-187. [CrossRef]

- Debarba, L.K.; Jayarathne, H.S.M.; Stilgenbauer, L.; dos Santos, A.L.T.; Koshko, L.; Scofield, S.; Sullivan, R.; Mandal, A.; Klueh, U.; Sadagurski, M. Microglia Mediate Metabolic Dysfunction From Common Air Pollutants Through NF-κB Signaling. Diabetes 2024, 73, 2065-2077. [CrossRef]

- van Beek, E.M.; Cochrane, F.; Barclay, A.N.; van den Berg, T.K. Signal Regulatory Proteins in the Immune System. The Journal of Immunology 2005, 175, 7781-7787. [CrossRef]

- Roselli, M.; Fernando, R.I.; Guadagni, F.; Spila, A.; Alessandroni, J.; Palmirotta, R.; Costarelli, L.; Litzinger, M.; Hamilton, D.; Huang, B.; et al. Brachyury, a driver of the epithelial-mesenchymal transition, is overexpressed in human lung tumors: an opportunity for novel interventions against lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2012, 18, 3868-3879. [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Lu, Y.; Xing, F.; Hsu, W. FGFR1/MAPK-directed brachyury activation drives PD-L1-mediated immune evasion to promote lung cancer progression. Cancer Lett 2022, 547, 215867. [CrossRef]

- Park, K.H.; Choi, Y.J.; Min, W.K.; Lee, S.H.; Kim, J.; Jeong, S.H.; Lee, J.H.; Choi, B.M.; Kim, S. Particulate matter induces arrhythmia-like cardiotoxicity in zebrafish embryos by altering the expression levels of cardiac development- and ion channel-related genes. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf 2023, 263, 115201. [CrossRef]

- Liang, C.; Ding, R.; Sun, Q.; Liu, S.; Sun, Z.; Duan, J. An Overview of Adverse Outcome Pathway Links between PM2.5 Exposure and Cardiac Developmental Toxicity. Environment & Health 2024, 2, 105-113. [CrossRef]

- Sinkevicius, K.W.; Kriegel, C.; Bellaria, K.J.; Lee, J.; Lau, A.N.; Leeman, K.T.; Zhou, P.; Beede, A.M.; Fillmore, C.M.; Caswell, D.; et al. Neurotrophin receptor TrkB promotes lung adenocarcinoma metastasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2014, 111, 10299-10304. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.-y.; Hui, L.-p.; Li, C.-y.; Gao, J.; Cui, Z.-s.; Qiu, X.-s. More expression of BDNF associates with lung squamous cell carcinoma and is critical to the proliferation and invasion of lung cancer cells. BMC Cancer 2016, 16, 171. [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.-m.; Liu, T.; Deng, S.-h.; Han, R.; Xu, Y. SLC39A4 expression is associated with enhanced cell migration, cisplatin resistance, and poor survival in non-small cell lung cancer. Scientific Reports 2017, 7, 7211. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Zhan, H.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, J.; Liu, M.; Xu, C.; Fan, X.; Zhang, J.; Zhou, Z.; Shi, X.; et al. ZIP4 promotes non-small cell lung cancer metastasis by activating snail-N-cadherin signaling axis. Cancer Lett 2021, 521, 71-81. [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Hu, Q.; Ansari, M.; Riemondy, K.; Pineda, R.; Sembrat, J.; Leme, A.S.; Ngo, K.; Morgenthaler, O.; Ha, K.; et al. Airway-derived emphysema-specific alveolar type II cells exhibit impaired regenerative potential in COPD. Eur Respir J 2024, 64. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, X.; Long, M.; Yuan, M.; Yin, J.; Luo, W.; Wang, S.; Cai, Y.; Jiang, W.; Chao, J. Macrophage-derived GPNMB trapped by fibrotic extracellular matrix promotes pulmonary fibrosis. Commun Biol 2023, 6, 136. [CrossRef]

- Taya, M.; Hammes, S.R. Glycoprotein Non-Metastatic Melanoma Protein B (GPNMB) and Cancer: A Novel Potential Therapeutic Target. Steroids 2018, 133, 102-107. [CrossRef]

- Payapilly, A.; Guilbert, R.; Descamps, T.; White, G.; Magee, P.; Zhou, C.; Kerr, A.; Simpson, K.L.; Blackhall, F.; Dive, C.; et al. TIAM1-RAC1 promote small-cell lung cancer cell survival through antagonizing Nur77-induced BCL2 conformational change. Cell Rep 2021, 37, 109979. [CrossRef]

- Carrera Silva, E.A.; Chan, P.Y.; Joannas, L.; Errasti, A.E.; Gagliani, N.; Bosurgi, L.; Jabbour, M.; Perry, A.; Smith-Chakmakova, F.; Mucida, D.; et al. T cell-derived protein S engages TAM receptor signaling in dendritic cells to control the magnitude of the immune response. Immunity 2013, 39, 160-170. [CrossRef]

- Shin, E.; Kwon, Y.; Jung, E.; Kim, Y.J.; Kim, C.; Hong, S.; Kim, J. TM4SF19 controls GABP-dependent YAP transcription in head and neck cancer under oxidative stress conditions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2024, 121, e2314346121. [CrossRef]

- Fu, F.; Yang, X.; Zheng, M.; Zhao, Q.; Zhang, K.; Li, Z.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, S. Role of Transmembrane 4 L Six Family 1 in the Development and Progression of Cancer. Front Mol Biosci 2020, 7, 202. [CrossRef]

- Rose, C.E., Jr.; Lannigan, J.A.; Kim, P.; Lee, J.J.; Fu, S.M.; Sung, S.S. Murine lung eosinophil activation and chemokine production in allergic airway inflammation. Cell Mol Immunol 2010, 7, 361-374. [CrossRef]

- Russo, R.C.; Ryffel, B. The Chemokine System as a Key Regulator of Pulmonary Fibrosis: Converging Pathways in Human Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis (IPF) and the Bleomycin-Induced Lung Fibrosis Model in Mice. Cells 2024, 13. [CrossRef]

- Russo, R.C.; Ryffel, B. The Chemokine System as a Key Regulator of Pulmonary Fibrosis: Converging Pathways in Human Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis (IPF) and the Bleomycin-Induced Lung Fibrosis Model in Mice. Cells 2024, 13, 2058.

- Brass, D.M.; Yang, I.V.; Kennedy, M.P.; Whitehead, G.S.; Rutledge, H.; Burch, L.H.; Schwartz, D.A. Fibroproliferation in LPS-induced airway remodeling and bleomycin-induced fibrosis share common patterns of gene expression. Immunogenetics 2008, 60, 353-369. [CrossRef]

- Azfar, M.; van Veen, S.; Houdou, M.; Hamouda, N.N.; Eggermont, J.; Vangheluwe, P. P5B-ATPases in the mammalian polyamine transport system and their role in disease. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Cell Research 2022, 1869, 119354. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Xu, B.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, J.; Zheng, X.; Liu, Y.; Deng, H.; Liu, M.; Ren, X.; Xia, J.; et al. Identification of Key Genes With Differential Correlations in Lung Adenocarcinoma. Front Cell Dev Biol 2021, 9, 675438. [CrossRef]

- Carnesecchi, S.; Deffert, C.; Pagano, A.; Garrido-Urbani, S.; Métrailler-Ruchonnet, I.; Schäppi, M.; Donati, Y.; Matthay, M.A.; Krause, K.H.; Barazzone Argiroffo, C. NADPH oxidase-1 plays a crucial role in hyperoxia-induced acute lung injury in mice. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2009, 180, 972-981. [CrossRef]

- Seimetz, M.; Sommer, N.; Bednorz, M.; Pak, O.; Veith, C.; Hadzic, S.; Gredic, M.; Parajuli, N.; Kojonazarov, B.; Kraut, S.; et al. NADPH oxidase subunit NOXO1 is a target for emphysema treatment in COPD. Nat Metab 2020, 2, 532-546. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Gao, Y.; Ding, P.; Wu, T.; Ji, G. The role of CXCL family members in different diseases. Cell Death Discovery 2023, 9, 212. [CrossRef]

- Liang, M.; Jiang, Z.; Huang, Q.; Liu, L.; Xue, Y.; Zhu, X.; Yu, Y.; Wan, W.; Yang, H.; Zou, H. Clinical Association of Chemokine (C-X-C motif) Ligand 1 (CXCL1) with Interstitial Pneumonia with Autoimmune Features (IPAF). Scientific Reports 2016, 6, 38949. [CrossRef]

- Mionnet, C.; Buatois, V.; Kanda, A.; Milcent, V.; Fleury, S.; Lair, D.; Langelot, M.; Lacoeuille, Y.; Hessel, E.; Coffman, R.; et al. CX3CR1 is required for airway inflammation by promoting T helper cell survival and maintenance in inflamed lung. Nature Medicine 2010, 16, 1305-1312. [CrossRef]

- Bain, C.C.; MacDonald, A.S. The impact of the lung environment on macrophage development, activation and function: diversity in the face of adversity. Mucosal Immunology 2022, 15, 223-234. [CrossRef]

- Pilette, C.; Ouadrhiri, Y.; Godding, V.; Vaerman, J.P.; Sibille, Y. Lung mucosal immunity: immunoglobulin-A revisited. Eur Respir J 2001, 18, 571-588. [CrossRef]

- Chae, J.; Choi, J.; Chung, J. Polymeric immunoglobulin receptor (pIgR) in cancer. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2023, 149, 17683-17690. [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, K.; Suzukawa, M.; Watanabe, K.; Arakawa, S.; Igarashi, S.; Asari, I.; Hebisawa, A.; Matsui, H.; Nagai, H.; Nagase, T.; et al. Secretory IgA accumulated in the airspaces of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and promoted VEGF, TGF-β and IL-8 production by A549 cells. Clin Exp Immunol 2020, 199, 326-336. [CrossRef]

- Guardado, S.; Ojeda-Juárez, D.; Kaul, M.; Nordgren, T.M. Comprehensive review of lipocalin 2-mediated effects in lung inflammation. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2021, 321, L726-l733. [CrossRef]

- Tanahashi, H.; Iwamoto, H.; Yamaguchi, K.; Sakamoto, S.; Horimasu, Y.; Masuda, T.; Nakashima, T.; Ohshimo, S.; Fujitaka, K.; Hamada, H.; et al. Lipocalin-2 as a prognostic marker in patients with acute exacerbation of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Respiratory Research 2024, 25, 195. [CrossRef]

- Treekitkarnmongkol, W.; Hassane, M.; Sinjab, A.; Chang, K.; Hara, K.; Rahal, Z.; Zhang, J.; Lu, W.; Sivakumar, S.; McDowell, T.L.; et al. Augmented Lipocalin-2 Is Associated with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease and Counteracts Lung Adenocarcinoma Development. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine 2021, 203, 90-101. [CrossRef]

- Cavallaro, D.; Guerrieri, M.; Cattelan, S.; Fabbri, G.; Croce, S.; Armati, M.; Bennett, D.; Fossi, A.; Voltolini, L.; Luzzi, L.; et al. Markers of Bronchiolitis Obliterans Syndrome after Lung Transplant: Between Old Knowledge and Future Perspective. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 3277.

- Vitorakis, N.; Piperi, C. Insights into the Role of Histone Methylation in Brain Aging and Potential Therapeutic Interventions. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [CrossRef]

- Taylor, B.C.; Young, N.L. Histone H4 proteoforms and post-translational modifications in the Mus musculus brain with quantitative comparison of ages and brain regions. Anal Bioanal Chem 2023, 415, 1627-1639. [CrossRef]

- Calderón-Garcidueñas, L.; Herrera-Soto, A.; Jury, N.; Maher, B.A.; González-Maciel, A.; Reynoso-Robles, R.; Ruiz-Rudolph, P.; van Zundert, B.; Varela-Nallar, L. Reduced repressive epigenetic marks, increased DNA damage and Alzheimer's disease hallmarks in the brain of humans and mice exposed to particulate urban air pollution. Environ Res 2020, 183, 109226. [CrossRef]

- Jakovcevski, M.; Akbarian, S. Epigenetic mechanisms in neurological disease. Nature Medicine 2012, 18, 1194-1204. [CrossRef]

- Edamatsu, M.; Miyano, R.; Fujikawa, A.; Fujii, F.; Hori, T.; Sakaba, T.; Oohashi, T. Hapln4/Bral2 is a selective regulator for formation and transmission of GABAergic synapses between Purkinje and deep cerebellar nuclei neurons. J Neurochem 2018, 147, 748-763. [CrossRef]

- Pintér, P.; Alpár, A. The Role of Extracellular Matrix in Human Neurodegenerative Diseases. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2022, 23, 11085.

- Back, S.A.; Tuohy, T.M.F.; Chen, H.; Wallingford, N.; Craig, A.; Struve, J.; Luo, N.L.; Banine, F.; Liu, Y.; Chang, A.; et al. Hyaluronan accumulates in demyelinated lesions and inhibits oligodendrocyte progenitor maturation. Nature Medicine 2005, 11, 966-972. [CrossRef]

- Doeppner, T.R.; Herz, J.; Bähr, M.; Tonchev, A.B.; Stoykova, A. Zbtb20 Regulates Developmental Neurogenesis in the Olfactory Bulb and Gliogenesis After Adult Brain Injury. Mol Neurobiol 2019, 56, 567-582. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Gai, C.; Yu, S.; Song, Y.; Gu, B.; Luo, Q.; Wang, X.; Hu, Q.; Liu, W.; Liu, D.; et al. Liposomes-Loaded miR-9-5p Alleviated Hypoxia-Ischemia-Induced Mitochondrial Oxidative Stress by Targeting ZBTB20 to Inhibiting Nrf2/Keap1 Interaction in Neonatal Mice. Antioxid Redox Signal 2025, 42, 512-528. [CrossRef]

- Solleiro-Villavicencio, H.; Rivas-Arancibia, S. Effect of Chronic Oxidative Stress on Neuroinflammatory Response Mediated by CD4+T Cells in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience 2018, Volume 12 - 2018. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Cai, M.; Lou, Y.; Zhang, S.; Liu, X. ZBTB20-AS1 promoted Alzheimer's disease progression through ZBTB20/GSK-3β/Tau pathway. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 2023, 640, 88-96. [CrossRef]

- Shih, J.C.; Chen, K.; Ridd, M.J. Monoamine oxidase: from genes to behavior. Annu Rev Neurosci 1999, 22, 197-217. [CrossRef]

- Singh, C.; Bortolato, M.; Bali, N.; Godar, S.C.; Scott, A.L.; Chen, K.; Thompson, R.F.; Shih, J.C. Cognitive abnormalities and hippocampal alterations in monoamine oxidase A and B knockout mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2013, 110, 12816-12821. [CrossRef]

- Beucher, L.; Gabillard-Lefort, C.; Baris, O.R.; Mialet-Perez, J. Monoamine oxidases: A missing link between mitochondria and inflammation in chronic diseases ? Redox Biology 2024, 77, 103393. [CrossRef]

- Zou, X.; Gao, S.; Li, J.; Li, C.; Wu, C.; Cao, X.; Xia, S.; Shao, P.; Bao, X.; Yang, H.; et al. A monoamine oxidase B inhibitor ethyl ferulate suppresses microglia-mediated neuroinflammation and alleviates ischemic brain injury. Front Pharmacol 2022, 13, 1004215. [CrossRef]

- Hughes, T.M.; Rosano, C.; Evans, R.W.; Kuller, L.H. Brain cholesterol metabolism, oxysterols, and dementia. J Alzheimers Dis 2013, 33, 891-911. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Lv, C.; An, Y.; Liu, Q.; Rong, H.; Tao, L.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Xiao, R. Increased Levels of 27-Hydroxycholesterol Induced by Dietary Cholesterol in Brain Contribute to Learning and Memory Impairment in Rats. Mol Nutr Food Res 2018, 62. [CrossRef]

- Dunk, M.M.; Rapp, S.R.; Hayden, K.M.; Espeland, M.A.; Casanova, R.; Manson, J.E.; Shadyab, A.H.; Wild, R.; Driscoll, I. Plasma oxysterols are associated with serum lipids and dementia risk in older women. Alzheimers Dement 2024, 20, 3696-3704. [CrossRef]

- Björkhem, I.; Leoni, V.; Meaney, S. Genetic connections between neurological disorders and cholesterol metabolism. Journal of Lipid Research 2010, 51, 2489-2503. [CrossRef]

- Rat Genome Database, R. ENSRNOG00000064885: Predicted Ensembl rat gene. Available online: https://rgd.mcw.edu/ (accessed on 04/25/2025).

- Martin, I.; Kim, J.W.; Lee, B.D.; Kang, H.C.; Xu, J.C.; Jia, H.; Stankowski, J.; Kim, M.S.; Zhong, J.; Kumar, M.; et al. Ribosomal protein s15 phosphorylation mediates LRRK2 neurodegeneration in Parkinson's disease. Cell 2014, 157, 472-485. [CrossRef]

- Asano, Y.; Kishida, S.; Mu, P.; Sakamoto, K.; Murohara, T.; Kadomatsu, K. DRR1 is expressed in the developing nervous system and downregulated during neuroblastoma carcinogenesis. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 2010, 394, 829-835. [CrossRef]

- van Olst, L.; Simonton, B.; Edwards, A.J.; Forsyth, A.V.; Boles, J.; Jamshidi, P.; Watson, T.; Shepard, N.; Krainc, T.; Argue, B.M.R.; et al. Microglial mechanisms drive amyloid-β clearance in immunized patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Nature Medicine 2025. [CrossRef]

- Xue, C.; Chu, Q.; Shi, Q.; Zeng, Y.; Lu, J.; Li, L. Wnt signaling pathways in biology and disease: mechanisms and therapeutic advances. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy 2025, 10, 106. [CrossRef]

- Halleskog, C.; Mulder, J.; Dahlström, J.; Mackie, K.; Hortobágyi, T.; Tanila, H.; Kumar Puli, L.; Färber, K.; Harkany, T.; Schulte, G. WNT signaling in activated microglia is proinflammatory. Glia 2011, 59, 119-131. [CrossRef]

- Ensembl. Gene: ENSRNOG00000069713 – Rattus norvegicus. Available online: https://useast.ensembl.org/Rattus_norvegicus/Gene/Splice?db=core;g=ENSRNOG00000069713;r=X:15395785-15398610;t=ENSRNOT00000101970 (accessed on 04/25/2025).

- Qureshi, I.A.; Mehler, M.F. Emerging roles of non-coding RNAs in brain evolution, development, plasticity and disease. Nature Reviews Neuroscience 2012, 13, 528-541. [CrossRef]

- Zeng, H.-X.; Qin, S.-J.; Andersson, J.; Li, S.-P.; Zeng, Q.-G.; Li, J.-H.; Wu, Q.-Z.; Meng, W.-J.; Oudin, A.; Kanninen, K.M.; et al. The emerging roles of particulate matter-changed non-coding RNAs in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer's disease: A comprehensive in silico analysis and review. Environmental Pollution 2025, 366, 125440. [CrossRef]

- Hirano, A.; Hsu, P.K.; Zhang, L.; Xing, L.; McMahon, T.; Yamazaki, M.; Ptáček, L.J.; Fu, Y.H. DEC2 modulates orexin expression and regulates sleep. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2018, 115, 3434-3439. [CrossRef]

- Lane, J.M.; Qian, J.; Mignot, E.; Redline, S.; Scheer, F.; Saxena, R. Genetics of circadian rhythms and sleep in human health and disease. Nat Rev Genet 2023, 24, 4-20. [CrossRef]

- van den Ameele, J.; Krautz, R.; Cheetham, S.W.; Donovan, A.P.A.; Llorà-Batlle, O.; Yakob, R.; Brand, A.H. Reduced chromatin accessibility correlates with resistance to Notch activation. Nature Communications 2022, 13, 2210. [CrossRef]

- Chuikov, S.; Levi, B.P.; Smith, M.L.; Morrison, S.J. Prdm16 promotes stem cell maintenance in multiple tissues, partly by regulating oxidative stress. Nat Cell Biol 2010, 12, 999-1006. [CrossRef]

- Schröder, S.; Fuchs, U.; Gisa, V.; Pena, T.; Krüger, D.M.; Hempel, N.; Burkhardt, S.; Salinas, G.; Schütz, A.L.; Delalle, I.; et al. PRDM16-DT is a novel lncRNA that regulates astrocyte function in Alzheimer's disease. Acta Neuropathol 2024, 148, 32. [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Liu, C.; Xu, Z.; Tzan, K.; Zhong, M.; Wang, A.; Lippmann, M.; Chen, L.C.; Rajagopalan, S.; Sun, Q. Long-term exposure to ambient fine particulate pollution induces insulin resistance and mitochondrial alteration in adipose tissue. Toxicol Sci 2011, 124, 88-98. [CrossRef]

- Ensembl. Senp5-ps1 (Small ubiquitin-like modifier (SUMO) protease 5 pseudogene) [ENSRNOG00000068362.1]. Available online: https://useast.ensembl.org/Rattus_norvegicus/Gene/Summary?db=core;g=ENSRNOG00000068362;r=2:95501188-95504509;t=ENSRNOT00000094190 (accessed on 27 April).

- Pink, R.C.; Wicks, K.; Caley, D.P.; Punch, E.K.; Jacobs, L.; Carter, D.R. Pseudogenes: pseudo-functional or key regulators in health and disease? Rna 2011, 17, 792-798. [CrossRef]

- Henley, J.M.; Craig, T.J.; Wilkinson, K.A. Neuronal SUMOylation: mechanisms, physiology, and roles in neuronal dysfunction. Physiol Rev 2014, 94, 1249-1285. [CrossRef]

- NCBI, G. POM121 transmembrane nucleoporin-like 2 (POM121L2), Rattus norvegicus (Rat). Gene ID: 94026. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gene/94026 (accessed on 26 April 2025).

- Coyne, A.N.; Rothstein, J.D. Nuclear pore complexes — a doorway to neural injury in neurodegeneration. Nature Reviews Neurology 2022, 18, 348-362. [CrossRef]

- Coyne, A.N.; Rothstein, J.D. The ESCRT-III protein VPS4, but not CHMP4B or CHMP2B, is pathologically increased in familial and sporadic ALS neuronal nuclei. Acta Neuropathol Commun 2021, 9, 127. [CrossRef]

- Komiyama, K.; Iijima, K.; Kawabata-Iwakawa, R.; Fujihara, K.; Kakizaki, T.; Yanagawa, Y.; Yoshimoto, Y.; Miyata, S. Glioma facilitates the epileptic and tumor-suppressive gene expressions in the surrounding region. Sci Rep 2022, 12, 6805. [CrossRef]

- Meyer, K.; Buettner, S.; Ghezzi, D.; Zeviani, M.; Bano, D.; Nicotera, P. Loss of apoptosis-inducing factor critically affects MIA40 function. Cell Death & Disease 2015, 6, e1814-e1814. [CrossRef]

- Modjtahedi, N.; Tokatlidis, K.; Dessen, P.; Kroemer, G. Mitochondrial Proteins Containing Coiled-Coil-Helix-Coiled-Coil-Helix (CHCH) Domains in Health and Disease. Trends Biochem Sci 2016, 41, 245-260. [CrossRef]

- Guerreiro, R.; Gibbons, E.; Tábuas-Pereira, M.; Kun-Rodrigues, C.; Santo, G.C.; Bras, J. Genetic architecture of common non-Alzheimer's disease dementias. Neurobiol Dis 2020, 142, 104946. [CrossRef]

- Bogorodskiy, A.; Okhrimenko, I.; Burkatovskii, D.; Jakobs, P.; Maslov, I.; Gordeliy, V.; Dencher, N.A.; Gensch, T.; Voos, W.; Altschmied, J.; et al. Role of Mitochondrial Protein Import in Age-Related Neurodegenerative and Cardiovascular Diseases. Cells 2021, 10. [CrossRef]

- Subramanian, A.; Tamayo, P.; Mootha, V.K.; Mukherjee, S.; Ebert, B.L.; Gillette, M.A.; Paulovich, A.; Pomeroy, S.L.; Golub, T.R.; Lander, E.S.; et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: A knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2005, 102, 15545-15550, doi:doi:10.1073/pnas.0506580102.

- Kanehisa, M.; Furumichi, M.; Sato, Y.; Kawashima, M.; Ishiguro-Watanabe, M. KEGG for taxonomy-based analysis of pathways and genomes. Nucleic Acids Research 2022, 51, D587-D592. [CrossRef]

- Kanehisa, M.; Goto, S. KEGG: Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes. Nucleic Acids Research 2000, 28, 27-30. [CrossRef]

- Saul, D.; Kosinsky, R.L.; Atkinson, E.J.; Doolittle, M.L.; Zhang, X.; LeBrasseur, N.K.; Pignolo, R.J.; Robbins, P.D.; Niedernhofer, L.J.; Ikeno, Y.; et al. A new gene set identifies senescent cells and predicts senescence-associated pathways across tissues. Nature Communications 2022, 13, 4827. [CrossRef]

- Cao, M.; Liu, J.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Y.; Hou, Y.; Song, Q.; Cui, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, P. IL-17A promotes the progression of Alzheimer’s disease in APP/PS1 mice. Immunity & Ageing 2023, 20, 74. [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Happonen, K.E.; Burrola, P.G.; O'Connor, C.; Hah, N.; Huang, L.; Nimmerjahn, A.; Lemke, G. Microglia use TAM receptors to detect and engulf amyloid β plaques. Nat Immunol 2021, 22, 586-594. [CrossRef]

- Pfau, S.J.; Langen, U.H.; Fisher, T.M.; Prakash, I.; Nagpurwala, F.; Lozoya, R.A.; Lee, W.-C.A.; Wu, Z.; Gu, C. Characteristics of blood–brain barrier heterogeneity between brain regions revealed by profiling vascular and perivascular cells. Nature Neuroscience 2024, 27, 1892-1903. [CrossRef]

- Choi, A.M.K.; Ryter, S.W.; Levine, B. Autophagy in human health and disease. The New England Journal of Medicine 2013, 368, 651-662. [CrossRef]

- Nixon, R.A. The role of autophagy in neurodegenerative disease. Nature Medicine 2013, 19, 983-997. [CrossRef]

- Park, M.; Pei, R. Endocytosis and its roles in lung diseases. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2020, 21, 6021. [CrossRef]

- Saheki, Y.; De Camilli, P. Synaptic vesicle endocytosis. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology 2012, 4, a005645. [CrossRef]

- Cloonan, S.M.; Choi, A.M.K. Mitochondria in lung disease. Journal of Clinical Investigation 2016, 126, 809-820. [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.-T.; Beal, M.F. Mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress in neurodegenerative diseases. Nature 2006, 443, 787-795. [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on.

- Hathaway, Q.A.; Majumder, N.; Goldsmith, W.T.; Kunovac, A.; Pinti, M.V.; Harkema, J.R.; Castranova, V.; Hollander, J.M.; Hussain, S. Transcriptomics of single dose and repeated carbon black and ozone inhalation co-exposure highlight progressive pulmonary mitochondrial dysfunction. Part Fibre Toxicol 2021, 18, 44. [CrossRef]

- Gao, E.; Shao, W.; Zhang, C.; Yu, M.; Dai, H.; Fan, T.; Zhu, Z.; Xu, W.; Huang, J.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Lung Epithelial Cells Can Produce Antibodies Participating In Adaptive Humoral Immune Responses. bioRxiv 2021, 2021.2005.2013.443498. [CrossRef]

- Kato, A.; Hulse, K.E.; Tan, B.K.; Schleimer, R.P. B-lymphocyte lineage cells and the respiratory system. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 2013, 131, 933-957. [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Lin, A.H.; Ru, F.; Patil, M.J.; Meeker, S.; Lee, L.Y.; Undem, B.J. KCNQ/M-channels regulate mouse vagal bronchopulmonary C-fiber excitability and cough sensitivity. JCI Insight 2019, 4. [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, A.; Ohnishi, H.; Okazawa, H.; Nakazawa, S.; Ikeda, H.; Motegi, S.; Aoki, N.; Kimura, S.; Mikuni, M.; Matozaki, T. Positive regulation of phagocytosis by SIRPbeta and its signaling mechanism in macrophages. J Biol Chem 2004, 279, 29450-29460. [CrossRef]

- National Center for Biotechnology, I. SIRPB3P signal regulatory protein beta 3, pseudogene [Homo sapiens (human)]. NCBI Gene 2025.

- Shen, Q.; Zhao, L.; Pan, L.; Li, D.; Chen, G.; Chen, Z.; Jiang, Z. Soluble SIRP-Alpha Promotes Murine Acute Lung Injury Through Suppressing Macrophage Phagocytosis. Front Immunol 2022, 13, 865579. [CrossRef]

- Deng, Z.; Fan, T.; Xiao, C.; Tian, H.; Zheng, Y.; Li, C.; He, J. TGF-β signaling in health, disease and therapeutics. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy 2024, 9, 61. [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Wang, Z.; Shi, X.; Zan, D.; Chen, H.; Yang, S.; Ding, F.; Yang, L.; Tan, P.; Ma, R.Z.; et al. TGFβ1-RCN3-TGFBR1 loop facilitates pulmonary fibrosis by orchestrating fibroblast activation. Respiratory Research 2023, 24, 222. [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.-H.; Yeh, C.-F.; Lee, Y.-T.; Shih, Y.-C.; Chen, Y.-T.; Hung, C.-T.; You, M.-Y.; Wu, P.-C.; Shentu, T.-P.; Huang, R.-T.; et al. Fibroblast-enriched endoplasmic reticulum protein TXNDC5 promotes pulmonary fibrosis by augmenting TGFβ signaling through TGFBR1 stabilization. Nature Communications 2020, 11, 4254. [CrossRef]

- Aschner, Y.; Downey, G.P. Transforming Growth Factor-β: Master Regulator of the Respiratory System in Health and Disease. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2016, 54, 647-655. [CrossRef]

- Choi, C.; Jeong, Y.L.; Park, K.-M.; Kim, M.; Kim, S.; Jo, H.; Lee, S.; Kim, H.; Choi, G.; Choi, Y.H.; et al. TM4SF19-mediated control of lysosomal activity in macrophages contributes to obesity-induced inflammation and metabolic dysfunction. Nature Communications 2024, 15, 2779. [CrossRef]

- Chung, C.-T.; Yeh, K.-C.; Lee, C.-H.; Chen, Y.-Y.; Ho, P.-J.; Chang, K.-Y.; Chen, C.-H.; Lai, Y.-K.; Chen, C.-T. Molecular profiling of afatinib-resistant non-small cell lung cancer cells in vivo derived from mice. Pharmacological Research 2020, 161, 105183. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Yue, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Q. Bioinformatics analysis of PLA2G7 as an immune-related biomarker in COPD by promoting expansion and suppressive functions of MDSCs. Int Immunopharmacol 2023, 120, 110399. [CrossRef]

- Karhadkar, T.R.; Pilling, D.; Cox, N.; Gomer, R.H. Sialidase inhibitors attenuate pulmonary fibrosis in a mouse model. Scientific Reports 2017, 7, 15069. [CrossRef]

- Krick, S.; Helton, E.S.; Easter, M.; Bollenbecker, S.; Denson, R.; Zaharias, R.; Cochran, P.; Vang, S.; Harris, E.; Wells, J.M.; et al. ST6GAL1 and α2-6 Sialylation Regulates IL-6 Expression and Secretion in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Front Immunol 2021, 12, 693149. [CrossRef]

- Fulkerson, P.C.; Zimmermann, N.; Hassman, L.M.; Finkelman, F.D.; Rothenberg, M.E. Pulmonary Chemokine Expression Is Coordinately Regulated by STAT1, STAT6, and IFN-γ. The Journal of Immunology 2004, 173, 7565-7574. [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.H.; Jiang, J.; Pang, Y.; Achyut, B.R.; Lizardo, M.; Liang, X.; Hunter, K.; Khanna, C.; Hollander, C.; Yang, L. CCL9 Induced by TGFβ Signaling in Myeloid Cells Enhances Tumor Cell Survival in the Premetastatic Organ. Cancer Res 2015, 75, 5283-5298. [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Zhang, T.; Qi, L.; Liu, R.; Liu, G.; Li, J.; Sun, C. Identification of Four Genes as Prognosis Signatures in Lung Adenocarcinoma Microenvironment. Pharmgenomics Pers Med 2021, 14, 15-26. [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Xiang, M. Foxn4 influences alveologenesis during lung development. Dev Dyn 2011, 240, 1512-1517. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Huang, X.; Zhang, X.; Lai, L.; Zhu, B.; Lin, P.; Kang, Z.; Yin, D.; Tian, D.; Chen, Z.; et al. The miR-941/FOXN4/TGF-β feedback loop induces N2 polarization of neutrophils and enhances tumor progression of lung adenocarcinoma. Frontiers in Immunology 2025, Volume 16 - 2025. [CrossRef]

- Aros, C.J.; Pantoja, C.J.; Gomperts, B.N. Wnt signaling in lung development, regeneration, and disease progression. Communications Biology 2021, 4, 601. [CrossRef]

- Vance, S.A.; Kim, Y.H.; George, I.J.; Dye, J.A.; Williams, W.C.; Schladweiler, M.J.; Gilmour, M.I.; Jaspers, I.; Gavett, S.H. Contributions of particulate and gas phases of simulated burn pit smoke exposures to impairment of respiratory function. Inhal Toxicol 2023, 35, 129-138. [CrossRef]

- Gutor, S.S.; Miller, R.F.; Blackwell, T.S.; Polosukhin, V.V. Environmental and occupational bronchiolitis obliterans: new reality. EBioMedicine 2023, 95, 104760. [CrossRef]

- Gutor, S.S.; Salinas, R.I.; Nichols, D.S.; Bazzano, J.M.R.; Han, W.; Gokey, J.J.; Vasiukov, G.; West, J.D.; Newcomb, D.C.; Dikalova, A.E.; et al. Repetitive sulfur dioxide exposure in mice models post-deployment respiratory syndrome. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2024, 326, L539-L550. [CrossRef]

- Sibener, L.; Zaganjor, I.; Snyder, H.M.; Bain, L.J.; Egge, R.; Carrillo, M.C. Alzheimer's Disease prevalence, costs, and prevention for military personnel and veterans. Alzheimers Dement 2014, 10, S105-110. [CrossRef]

- Tanner, C.M.; Goldman, S.M.; Ross, G.W.; Grate, S.J. The disease intersection of susceptibility and exposure: chemical exposures and neurodegenerative disease risk. Alzheimers Dement 2014, 10, S213-225. [CrossRef]

- Klein, S.L.; Flanagan, K.L. Sex differences in immune responses. Nature Reviews Immunology 2016, 16, 626-638. [CrossRef]

- So, S.W.; Nixon, J.P.; Bernlohr, D.A.; Butterick, T.A. RNAseq Analysis of FABP4 Knockout Mouse Hippocampal Transcriptome Suggests a Role for WNT/beta-Catenin in Preventing Obesity-Induced Cognitive Impairment. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [CrossRef]

- Breheny P, H.J. Coordinate descent algorithms for nonconvex penalized regression, with applications to biological feature selection. Annals of Applied Statistics 2011, 5, 232-253.

- Fan, J.; Li, R. Variable selection via nonconcave penalized likelihood and its oracle properties. Journal of the American Statistical Association 2001, 96, 1348-1360.

- Friedman, J.; Hastie, T.; Tibshirani, R. Regularization Paths for Generalized Linear Models via Coordinate Descent. J Stat Softw 2010, 33, 1-22.

- Chen, F.; Zhang, W.; Mfarrej, M.F.B.; Saleem, M.H.; Khan, K.A.; Ma, J.; Raposo, A.; Han, H. Breathing in danger: Understanding the multifaceted impact of air pollution on health impacts. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety 2024, 280, 116532. [CrossRef]

- Trembley, J.H.; Barach, P.; Tomáška, J.M.; Poole, J.T.; Ginex, P.K.; Miller, R.F.; Sandri, B.J.; Szema, A.M.; Gandy, K.; Siddharthan, T.; et al. Veterans Affairs Military Toxic Exposure Research Conference: Veteran-centric Approach and Community of Practice. Mil Med 2024. [CrossRef]

- Ginex, P.K.; Barach, P.; Boffetta, P.; Poole, J.T.; Trembley, J.H.; Tomấška, J.; Klein, M.A.; Butterick, T.A. Exposure-Informed Care Following Toxic Environmental Exposures: A Lifestyle Medicine Approach. Am J Lifestyle Med 2025, 15598276251327106. [CrossRef]

- Tay, J.K.; Narasimhan, B.; Hastie, T. Elastic Net Regularization Paths for All Generalized Linear Models. Journal of Statistical Software 2023, 106, 1-31.

- Tibshirani, R. Regression shrinkage and selection via the lasso. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series B: Statistical Methodology 1996, 58, 267-288.

- Breheny, P.; Huang, J. Coordinate descent algorithms for nonconvex penalized regression, with applications to biological feature selection. Annals of Applied Statistics 2011, 5, 232-253.

- Zou, H.; Hastie, T. Regression shrinkage and selection via the elastic net, with applications to microarrays. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series B 2003, 67, 301-320.

- Cheng, H.; Garrick, D.J.; Fernando, R.L. Efficient strategies for leave-one-out cross validation for genomic best linear unbiased prediction. Journal of Animal Science and Biotechnology 2017, 8, 1-5.

| Biomarker | Tissue | NA | CBN | Biological Role / Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IL1β | Lung | ↑ | ↑ | IL1β is a proinflammatory cytokine involved in acute lung inflammation with key roles in local and systemic inflammation and is commonly elevated following particulate matter exposure [16,26,27]. |

| IL4 | Lung Plasma Brain |

↑ ↑ ↓ |

↑ ↑ ↓ |

IL4 is a Th2 cytokine that plays a role in allergic airway inflammation, pulmonary hypertension and in regulating neuroimmune signaling [16,28,29]. |

| IL5 | Lung Brain |

↑ ↓ |

↑ ↓ |

IL5 promotes eosinophil activity; upregulated in lung but suppressed in brain, suggesting compartmentalized immune activation [16,30,31]. |

| IL6 | Lung Brain Plasma |

↓ ↓ ↑ |

↓ ↓ ↑ |

IL6 is a pleiotropic cytokine; suppressed in lung and brain, but elevated in plasma during systemic inflammation from inhaled toxicants[32,33,34,35]. IL6 deficiency in acute lung injury is associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) [32,36] |

| IL10 | Lung Plasma Brain |

↑ ↑ ↓ |

↑ ↑ ↓ |

IL10 is an anti-inflammatory cytokine; increased in plasma and lung but decreased in brain, suggesting differential regulation under toxic stress [16,37]. |

| IL13 | Lung Brain |

↑ ↓ |

↑ ↓ |

IL13 mediates mucus production and drives fibrosis and remodeling in lung and has context-dependent pro- or anti-inflammatory effects in the brain [28,38,39]. Decreased IL13 in the CNS is linked to increased neurodegeneration, highlighting how toxicant exposures differentially regulate lung and brain immune responses [39]. |

| IFNγ | Lung Brain |

↑ ↑ |

↑ ↑ |

IFNγ, a Th1 cytokine, plays a dual role in lung and brain toxicity. In lung, it promotes macrophage activation and inflammation, contributing to tissue injury after toxicant exposure and supporting neuroprotective immune regulation [9,16,40]. In brain, IFN-γ both exacerbates neuroinflammation and supports neuroprotective immune regulation [9,16,40]. |

| KC/GRO (CXCL1) | Lung Plasma Brain |

↑ ↑ ↑ |

↑ ↑ ↑ |

KC/GRO (CXCL1) recruits neutrophils, is expressed by macrophages, and is markedly elevated in lung, plasma, and brain after exposures, a hallmark of lung and brain injury [8,41,42,43,44,45,46]. |

| TNFα | Lung Plasma Brain |

↑ | ↑↑ | TNFα is a key proinflammatory mediator that drives lung injury through macrophage activation and neutrophil recruitment and promotes microglial activation and neurodegeneration in the brain following toxic exposures [8,9,16,47,48]. |

| NF-κB (Western Blot) | Lung Brain |

N/A N/A |

↑ ↑ |

NF-κB is a transcription factor activated by oxidative and inflammatory stress, driving lung and brain injury [16,49]. PM exposures upregulate NF-κB in lung, promoting inflammation and epithelial damage [49]. In brain, NF-κB activation contributes to neuroinflammation, metabolic dysfunction, and neurodegeneration [47,50]. |

| LUNG | ||

|

Gene Symbol Decreased or Increased |

Full Gene Name | Biological Function and Disease Relevance |

| Sirpb3 | Signal-regulatory protein beta-3 | Sirpb3 is a non-coding pseudogene in the signal regulatory protein (SIRP) family, which includes receptors expressed on myeloid cells. Although it does not encode a protein, Sirpb3 may influence immune signaling through RNA-based mechanisms, similar to SIRPB1, which promotes myeloid activation and inflammation[51]. Persistent activation of SIRP-related pathways can amplify myeloid signaling, driving chronic inflammation, impaired epithelial repair, tissue damage, and fibrosis. In contrast, reduced expression may impair phagocytic clearance and antigen resolution, increasing susceptibility to infection and promoting maladaptive lung remodeling. [51]. |

| Tbxt | T-box transcription factor T; alias, brachyury | Fundamentally important for lung development, reactivation in adult tissue is associated with lung injury responses, fibrosis via TGF-β, Wnt signaling, and cancer, influencing tissue remodeling and repair outcomes [52,53]. Downregulation of Tbxt in the lung may impair epithelial regeneration and repair of injured airways, leading to persistent epithelial damage. It also disrupts necessary matrix remodeling, which can result small airway injury and contribute to chronic inflammation and may increase the risk of diseases like bronchiolitis obliterans and early-stage COPD [54,55]. |

| Ntrk2 | Neurotrophic receptor tyrosine kinase 2 | Encodes for neurotrophic receptor tyrosine kinase 2 (TrkB). Reduced expression of Ntrk2 (TrkB) may impair neurotrophic signaling and epithelial repair, potentially hindering recovery from lung injury. In contrast, increased Ntrk2 expression is associated with aggressive tumor behavior, enhanced metastasis, and poor survival in lung adenocarcinoma [56,57]. |

| Slc39a4 | Solute carrier family 39 (zinc transporter), member 4; alias, Zrt like protein-4 (Zip4) | Encodes for zinc transporter-4 (Zip-4) that is overexpressed in non-small cell lung cancer, where it promotes metastasis by activating epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT)-related pathways [58]. ZIP4 promotes NSCLC progression and metastasis by upregulating the snail-N-cadherin signaling axis, thereby facilitating EMT and enhancing cell migration and invasion[59]. |

| Ly6i | Lymphocyte antigen 6 complex, locus I | Surface marker selectively expressed in a dysfunctional subpopulation of alveolar type II cells in emphysematous lungs. Ly6i+ cells exhibit impaired regenerative capacity, increased senescence, and inflammation, contributing to progressive tissue damage in COPD [60]. Its presence may lead to long-term respiratory decline and increased risk of chronic lung failure [60]. |

| Gpnmb | Glycoprotein non-metastatic melanoma protein B | Transmembrane protein expressed in injured lung epithelial and immune cells, where it regulates cell adhesion, immune response, and tissue repair. In lung injury and cancer, it promotes tumor growth and invasion through membrane signaling and its shed ectodomain, activating integrins and MMPs. Up-regulation of Gpnmb in lung leads to its accumulation in fibrotic ECM. Enhances fibroblast proliferation, migration, and fibrotic protein production, contributing to progressive tissue remodeling [61,62]. |

| Tiam1 | T-cell lymphoma invasion and metastasis 1 | Regulates cell migration and cytoskeletal remodeling through Rac1 signaling. Tiam1 may also influence fibroblast activation and endothelial barrier function during lung injury[63,64]. Long-term dysregulation of Tiam1 affects lung health in a disease-dependent manner. Overexpression promotes tumor invasion and metastasis in both small cell and non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), while reduced expression may impair tissue repair and endothelial barrier integrity [63,64]. |

| Tm4sf19 | Transmembrane 4 L six family member 19; alias, transmembrane 4L | Transmembrane protein expressed in lung epithelial cells, where it participates in signal transduction, transcriptional regulation, and response to oxidative stress. It influences GABP-mediated YAP signaling pathways in maintaining epithelial integrity [65]. May also regulate immune cell interactions, contributing to immune surveillance and inflammation in the lung tissue[66]. Altered Tm4sf19 expression is linked to NSCLC tumor progression and may also contribute to inflammation or epithelial dysfunction in COPD and lung fibrosis. Its effects depend on cellular stress and immune signaling, potentially protecting or worsening disease based on context [65,66]. |

| Ccl9 | Chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 9; alias, macrophage inflammatory protein-1 gamma (MIP-1γ) | Chemokine expressed in lung tissue that recruits monocytes, macrophages, and dendritic cells via the CCR1 receptor[67] to support innate immune responses during lung injury or infection [68]. Long-term dysregulation of Ccl9 in the lung contributes to chronic inflammation and immune-driven tissue remodeling. Its persistent upregulation is associated with fibrosis and may worsen outcomes in diseases like asthma, COPD, and pulmonary fibrosis. Ccl9 may also amplify lung responses to environmental exposures, promoting progressive damage over time [69,70]. |

| Atp13a4 | ATPase 13A4 | P-type ATPase that transports polyamines and cations using ATP hydrolysis; helps maintain ion balance and may support epithelial integrity, stress responses, and signaling [71]. Its regulation of calcium and polyamines suggests a role in oxidative stress and tissue remodeling [72]. Atp13a4 amplification has been linked to lung cancer prognosis [72]. Dysregulation of polyamine or ion transport via ATP13A4 could also contribute to epithelial dysfunction [72]. |

| Noxo1 | NADPH oxidase organizer 1 | Regulates ROS generation in lungs; elevated in response to air pollution and oxidative injury [73]. Oxidative stress regulator implicated in fibrosis and progressive lung disease such as COPD [74] |

| Cxcl1 | C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 1; alias, KC/GRO | Chemokine that recruits neutrophils to inflamed lung tissue; key in early lung immune response to toxins[75,76]. |

| Cx3cl1 | C-X3-C motif chemokine ligand 1; alias, fractalkine | Chemokine expressed by lung epithelial, endothelial, and smooth muscle cells in both membrane-bound and soluble forms. It regulates monocyte and macrophage recruitment through the receptor Cx3cr1, supporting immune cell adhesion, cytokine release, and tissue remodeling [77,78]. In chronic lung diseases like COPD, asthma, and IPF, dysregulated CX3CL1 expression drives persistent macrophage-mediated inflammation and fibrosis, contributing to progressive tissue damage [77,78]. Elevated protein expression in lung tissue demonstrated in preclincal burn pit models [16]. |

| Pigr | Polymeric immunoglobulin receptor | Immunoglobulin receptor (PIGR) transports IgA and IgM across lung epithelial cells to generate secretory IgA at the mucosal surface, where it neutralizes inhaled pathogens and toxins. PIGR expression is regulated by inflammatory cytokines, enabling immune defense and limiting immune response [79,80,81]. Loss of PIGR regulation may increase susceptibility to infection and chronic respiratory illness. Overexpression in the lung often reflects epithelial stress or immune activation, as observed in COPD, asthma, IPF, and lung cancer. While initially protective, sustained PIGR elevation can drive epithelial remodeling, disrupt immune tolerance, and promote chronic inflammation, contributing to airway hyperreactivity and fibrosis [80,81] |

| Lcn2 | Lipocalin-2 | Iron-binding glycoprotein produced by lung epithelial and immune cells, playing key roles in inflammation, innate immunity, and iron regulation. While it helps protect against bacterial infection by sequestering iron, excessive LCN2 expression contributes to chronic inflammation, oxidative stress, and lung tissue damage [82,83]. Upregulated in both COPD and constrictive bronchiolitis, contributing to inflammation, immune dysregulation, and airway structural damage. Elevation can lead to iron imbalance and oxidative stress, chronic tissue injury and impaired repair. Can promote airway remodeling, fibrosis, and lung function decline, increasing the risk of lung cancer [82,84,85]. |

| BRAIN | ||

| Gene Symbol (Accession) | Full Gene Name | Biological Function and Disease Relevance |

| Hist1h4m | Histone cluster 1 H4 family member | Histone protein linked to epigenetic modulation under stress; altered in neurotoxic exposure models [86,87,88]. H4-mediated epigenetic alteration may contribute to memory deficits and aging-related brain dysfunction [86,87,88]. |

| H1f2 | H1 histone family member 2 | Histone protein involved in chromatin structure; dysregulation linked to neurodegenerative changes [86,88,89]. Altered expression found in neuroinflammatory and cognitive impairment models [86,88,89]. |

| Hapln4 | Hyaluronan and proteoglycan link protein 4; alias, brain link protein 2 (Bral2) | Encodes an extracellular matrix protein that links hyaluronic acid to proteoglycans, supporting synaptic architecture and stability [90]. Enriched at GABAergic synapses, Hapln4 plays critical roles in nervous system development, synaptic maturation, and maintaining extracellular homeostasis [90]. Elevated Hapln4 expression can impair synaptic transmission, restrict neuroplasticity, and promote neuroinflammation following injury or toxicant exposure, increasing vulnerability to cognitive dysfunction and neurodegenerative diseases [91,92]. |

| Zbtb20 | Zinc finger and BTB domain containing 20 | Transcription factor essential for brain development, regulating neuronal differentiation, synaptic plasticity, and memory formation [93]. It also modulates oxidative stress and inflammatory responses, positively regulating pro-inflammatory cytokines during neuroinflammation and injury [94]. Linked to Alzheimer’s pathology and cognitive decline after toxic exposures [95,96]. |

| Maob | Monoamine oxidase B | Encodes monoamine oxidase B, a mitochondrial enzyme that degrades neurotransmitters like dopamine and serotonin, regulating neurotransmitter balance and producing hydrogen peroxide[97,98,99]. Its activity, enriched in astrocytes and neurons, links it to oxidative stress in the brain [100]. Dysregulated MAOB activity leads to elevated oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, and neuronal damage [100]. Upregulation of Maob has been implicated in neurodegenerative diseases such as PD and AD, contributing to cognitive decline, neuroinflammation, and progressive dopaminergic neuron loss [100]. |

| Cyp7b1 | Cytochrome P450 family 7 subfamily B member 1; alias, oxysterol 7-alpha-hydroxylase brain | Encodes a cytochrome P450 enzyme that plays a crucial role in the metabolism of neurosteroids and cholesterol-derived molecules within the brain[101]. It helps regulate the synthesis of specific oxysterols and neuroactive steroids, impacting neuronal protection, signaling, and inflammation. Dysregulation of Cyp7b1 can increase vulnerability to neurodegeneration, inflammation, and lipid imbalances seen in conditions like Alzheimer’s disease [101,102,103,104]. |

|

ENSRNOG00000064885 (only Ensembl ID available) |

Predicted Ensembl rat gene | Predicted to encode a ribosomal protein that maintains ribosome integrity, facilitates translation, and participates in ribonucleoprotein complexes essential for protein synthesis [105]. Ribosomal dysfunction may impair neuronal protein synthesis and plasticity, increasing susceptibility to oxidative stress, inflammation, and neurodegeneration after toxicant exposure [106]. |

| Fam107a | Family with sequence similarity 107 member A; alias, Down-Regulated in Renal Cell Carcinoma 1 (Drr1) | Stress-inducible, actin-binding protein that regulates cytoskeletal dynamics, supporting synaptic function, neural cell survival, and adaptation to stress [107]. Fam107a also modulates microglial activation, linking neural stress responses to neuroinflammation [108]. Sustained upregulation supports neural protection and reduced inflammation, but chronic dysregulation may cause maladaptive inflammation or synaptic dysfunction. Balanced Fam107a expression is crucial for long-term brain health [108]. |

| Wnt3a | Wingless/Intergrated (Wnt) family member3A |

Protein coding gene for Wnt3A glycoprotein involved in Wnt signaling. Plays a vital role in brain development and function by promoting neurogenesis, supporting neuronal differentiation and synaptic plasticity, protecting against oxidative stress, and maintaining neural stem cell niches [109]. Wnt3a acts as a double-edged sword in the adult brain, supporting repair, neurogenesis, and immune regulation under balanced activation, but potentially exacerbating neuroinflammation and degeneration when overactivated, particularly in chronic disease or toxic exposures [110]. |

|

ENSRNOG00000069713 (only Ensembl ID available) |

Predicted Ensembl rat gene | Predicted to function as a long noncoding RNA (lncRNA), Unknown experimentally, but typical lncRNAs regulate gene expression, chromatin remodeling, RNA stability, and may affect ribosome-related processes indirectly [111]. Dysregulation of lncRNAs may impact gene expression to impair memory, plasticity, and promote neurodegeneration after toxicant exposures [112,113]. |

| Bhlhe23 | Basic helix-loop-helix family member e23; alias Dec2 | Transcription factor crucial for neuronal differentiation and retinal development and may also influence circadian rhythm regulation in the brain. Its activity helps shape the development and specialization of certain neuron types [114,115]. Upregulation of Bhlhe23 may increase orexin neuron activity, reducing sleep duration and extending wakefulness. This can lead to impaired cognition, mood disturbances, and increased risk of neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration over time [114]. |

| Prdm16 | PR/SET domain 16 | Transcriptional regulator involved in neurogenesis and the maintenance of neural stem cells [116]. It promotes neuronal differentiation and protects against oxidative stress, supporting normal brain development and function[117]. Dysregulation of Prdm16 in the brain may compromise neurogenesis, increase oxidative stress susceptibility, and negatively affect cognition and long-term brain health, especially under stress or environmental challenge [17,118,119]. |

| Senp5-ps1 | Small ubiquitin-like modifier (SUMO) protease 5 pseudogene | Pseudogene variant of Senp5; non-functional transcript, may regulate their corresponding genes by acting as molecular decoys for microRNAs or generating noncoding RNAs that influence gene expression [120]. Pseudogenes of SUMO proteases may influence neurodegeneration and neuroinflammation by modulating gene expression linked to neuronal survival and cellular stress responses [121]. Changes in their activity could alter susceptibility to neurodegenerative and neuroinflammatory diseases [122]. |

| Pom121L2 | POM121 transmembrane nucleoporin-like 2 | Predicted to encode a nucleoporin-like protein that binds nuclear localization sequences and acts as a structural constituent of the nuclear pore complex. It likely facilitates RNA export and protein import between the nucleus and cytoplasm [123]. Disruption of nuclear pore complex proteins impairs nucleocytoplasmic transport, leading to blood-brain barrier dysfunction, oxidative stress, and chronic neuroinflammation, which collectively increase the risk of neurodegeneration. [124,125]. In a glioma model, Pom121L2 was found to be downregulated in the peritumoral brain region characterized by neuroinflammation and epileptogenic activity [126]. |

| Chchd4 | Coiled-coil-helix-coiled-coil-helix domain containing 4; alias, Mitochondrial intermembrane space import and assembly protein 40 (Mia40) | Essential for mitochondrial protein import; mitochondrial respiration and redox regulation[127], lipid metabolism[128], downregulation suggests energy metabolism deficits in brain [129]. Linked to impaired neuronal energy supply and mitochondrial dysfunction in brain disease[130] |

| Gene Symbol |

Full Gene Name | Biological Function and Disease Relevance |

|---|---|---|

| IgV gene | Immunoglobulin variable region | Predicted transcript, IgV gene expression in lung injury reflects the activation of the adaptive immune system, particularly B cell recruitment and antibody production [146,147]. While activation of IgV may be protective, sustained IgV upregulation is associated with chronic inflammation, tissue remodeling, and fibrosis, as observed in lung diseases such as COPD and interstitial lung disease (ILD) [146,147]. |

| Kcnq3 | Potassium voltage-gated channel subfamily Q member 3 | Potassium channel subunit that regulates membrane potential and sensory neuron excitability in the lung, influencing neuropeptide release, inflammation, and lung injury severity[148].Kcnq3 dysregulation can lead to chronic sensory neuron hyperexcitability, promoting airway hypersensitivity, inflammation, and persistent cough. Long-term, this may contribute to airway remodeling and worsening of chronic lung diseases such as asthma or COPD [148]. |

| Sirpb3 | Signal-regulatory protein beta-3 | Sirpb3 is a pseudogene in the signal regulatory protein (SIRP) family, which includes transmembrane receptors involved in myeloid cell signaling [149]. Though non-coding, Sirpb3 may regulate innate immune responses through RNA-based mechanisms [150]. Based on its similarity to Sirpb1 which promotes myeloid activation and inflammation Sirpb3 may influence immune signaling and contribute to lung inflammatory states [149,150,151]. |

| Tgfrb1 | Transforming growth factor-beta receptor type 1 | Receptor for TGF-β signaling involved in immune regulation and fibrosis; controls lung cell differentiation and matrix production, activation promoting inflammation [152,153].Persistent Tgfbr1 activation promotes chronic inflammation, subepithelial fibrosis, smooth muscle thickening, and airway remodeling; impairs epithelial repair and regeneration, leading to fixed airflow obstruction associated with ConB and progressive disease in IPF, COPD, and asthma [154,155]. |

| Tm4sf19 | Transmembrane 4 L six family member 19 | Tetraspanin-like membrane protein that alters lysosomal degradation in macrophages, oxidative stress, and intracellular lipid content and cellular adhesion and immune signaling lysosomal activity in macrophages [156,157]. Dysregulation of Tm4sf19 may impair macrophage lysosomal function and promote oxidative stress, contributing to chronic inflammation, defective lipid clearance, and persistent immune activation processes that underlie airway remodeling and progression of chronic lung diseases such as COPD [156,158]. |

| St3Gal2 | ST3 beta-galactoside alpha-2,3-sialyltransferase 2 | Functions as a sialyltransferase enzyme that catalyzes the addition of sialic acid to glycoproteins and glycolipids, specifically in an α2,3 linkage to galactose residues [159]. This sialylation regulates protein stability, cell signaling, and immune cell interactions. Elevated ST3GAL2 in fibrotic lungs coincides with reduced sialylation, disrupting glycoprotein function and promoting fibrosis [160]. |

| Tiam1 | T-cell lymphoma invasion and metastasis-inducing protein 1 | Cell migration, cytoskeletal remodeling, Rac1 signaling, [64], promotes small cell lung cancer[63]. In the lung, elevated Tiam1 expression has been linked to enhanced invasiveness and metastasis in small cell lung cancer (SCLC). Its dysregulation may also contribute to abnormal epithelial remodeling in chronic lung disease [63]. |

| Ccl9 | Chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 9 | Functions in the lung as a chemokine primarily produced by myeloid cells such as macrophages and dendritic cells. It promotes the recruitment of immune cells through its receptor CCR1, contributing to inflammatory responses and shaping the immune microenvironment [161,162] . It promotes recruitment of dendritic cells and other leukocytes, amplifying inflammatory responses in diseases like asthma [161]. In cancer, especially lung metastasis models, CCL9 induced by TGF-β signaling in myeloid cells enhances tumor cell survival and creates a pro-metastatic lung microenvironment by recruiting immunosuppressive cells [162]. |

| Foxn4 | Forkhead box N4 | Transcription factor expressed in proximal airway epithelial cells during lung development; its loss impairs alveologenesis, leading to enlarged alveoli, thin walls, and poor septation[163,164]. Foxn4 is critical for normal lung development, with its loss leading to impaired alveolar structure and maturation. In lung adenocarcinoma, Foxn4 acts as a tumor suppressor by inhibiting TGF-β signaling and epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Its downregulation promotes tumor progression and inflammation via neutrophil polarization [165]. |

| Tm4sf1 | Transmembrane 4 L six family member 1 |

Tetraspanin-like membrane protein that serves as a marker of Wnt-responsive alveolar epithelial progenitor (AEP) cells, contributing to alveolar repair and regeneration after lung injury [66,166]. Supports lung repair by marking Wnt-responsive alveolar progenitor cells involved in regenerating alveolar epithelium after injury [166]. However, in lung cancer particularly NSCLC its overexpression promotes tumor growth, invasion, and epithelial-mesenchymal transition via PI3K/AKT and JAK/STAT signaling. This dual role makes TM4SF1 both a regenerative marker and a potential oncogenic driver [66]. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).