Submitted:

26 December 2025

Posted:

02 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Sustainability of EV Traction Motors

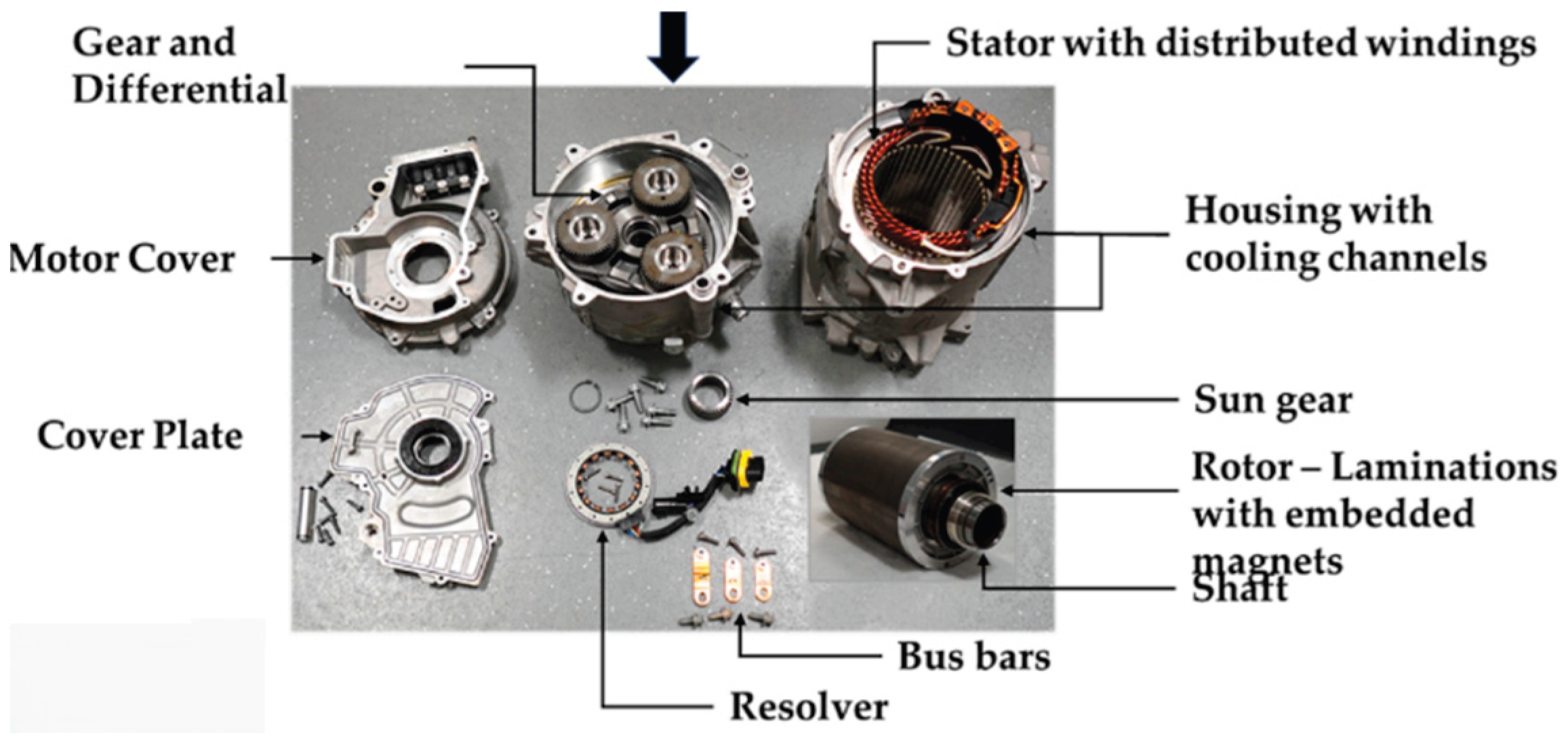

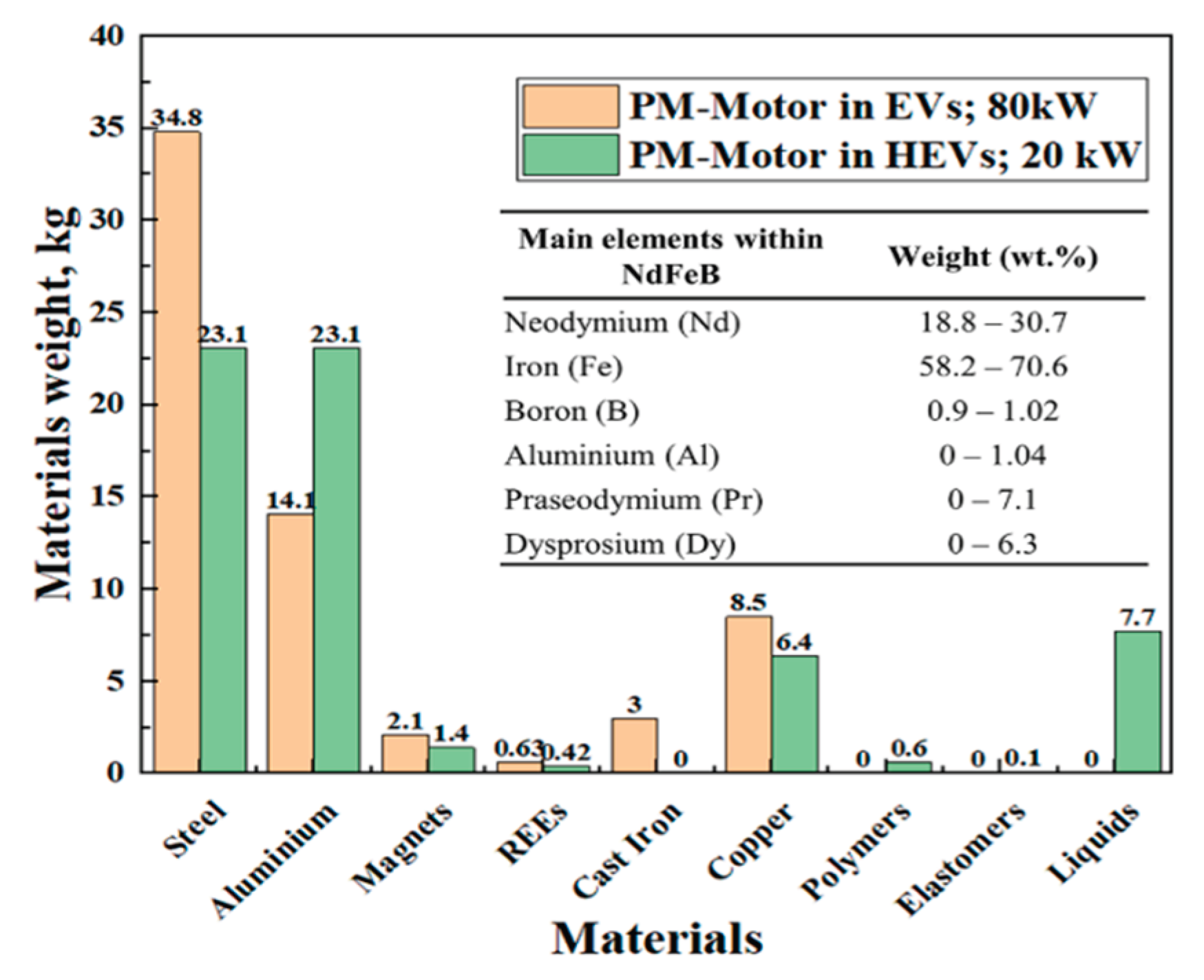

3.1. Production of Key Components for EV Traction Motors

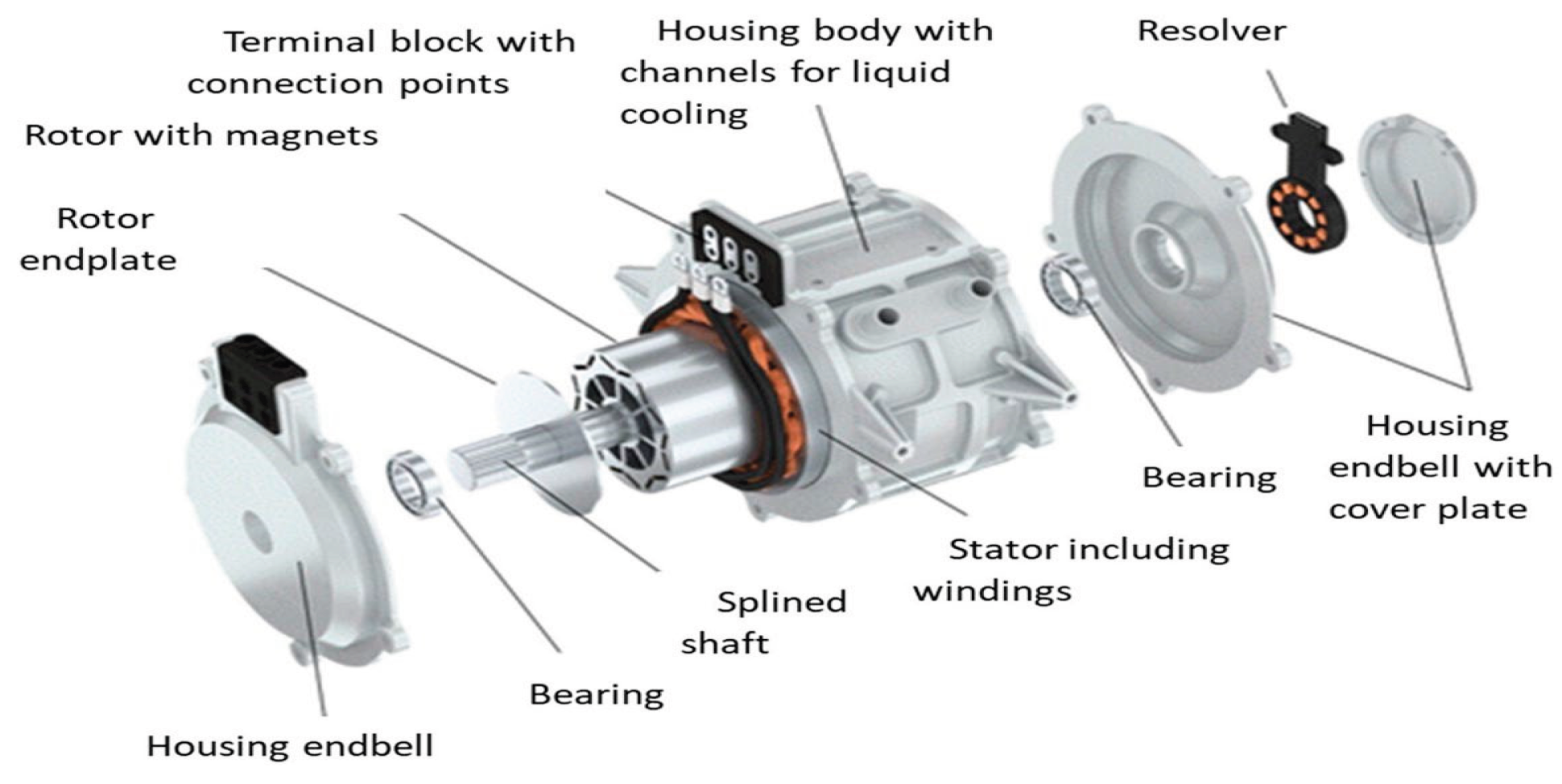

3.2. Types, Classification, Construction and Characteristics of Traction Motors

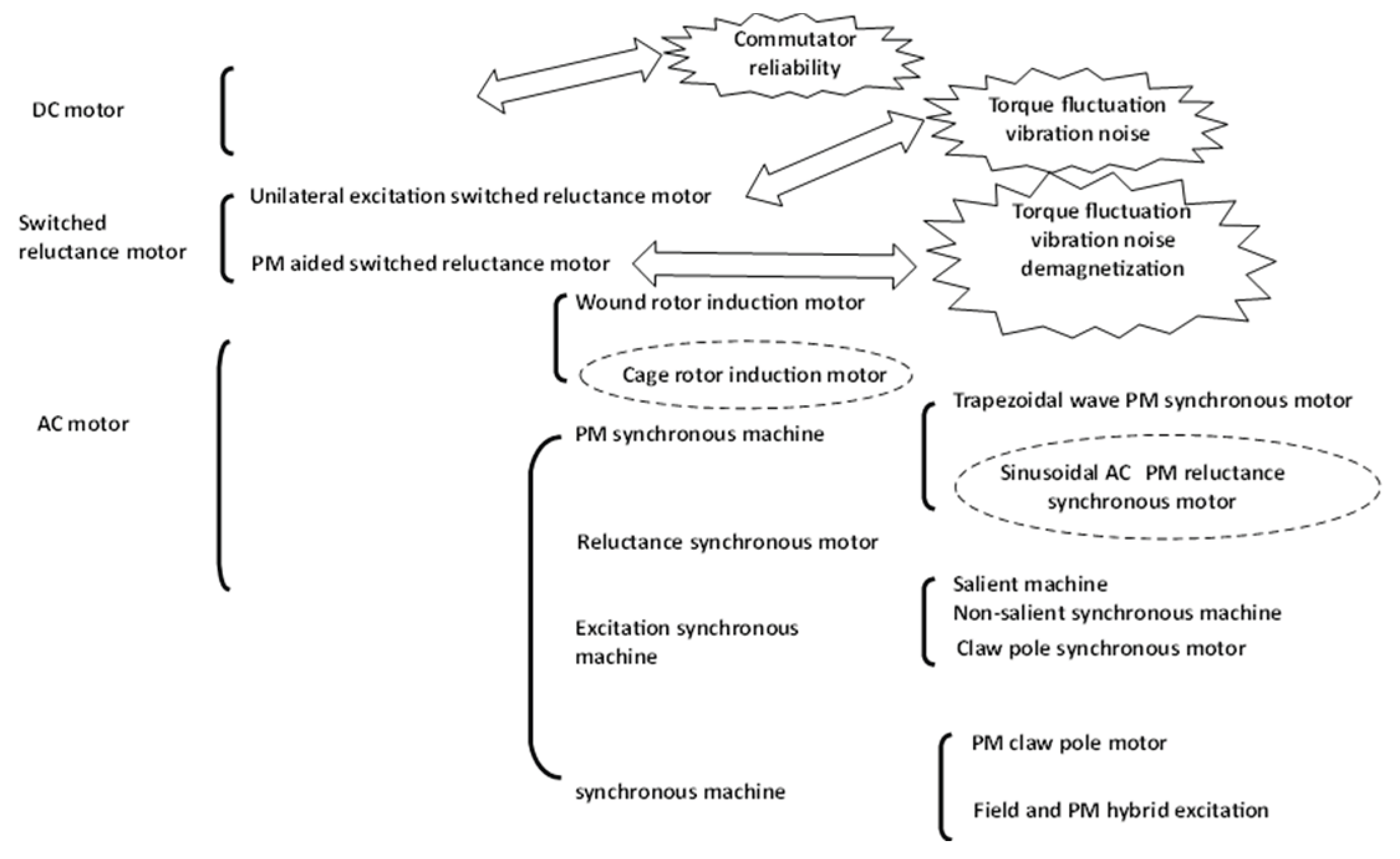

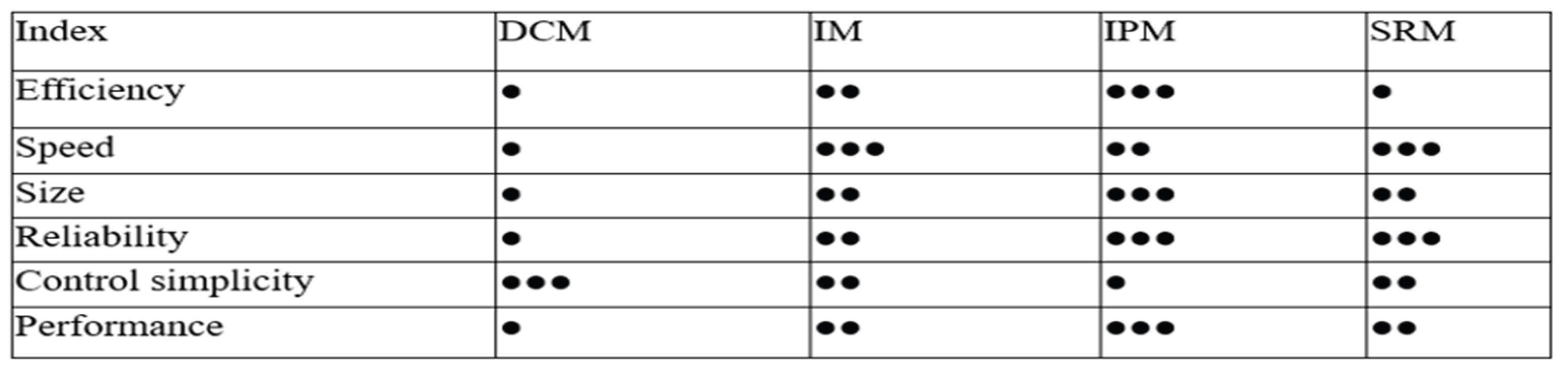

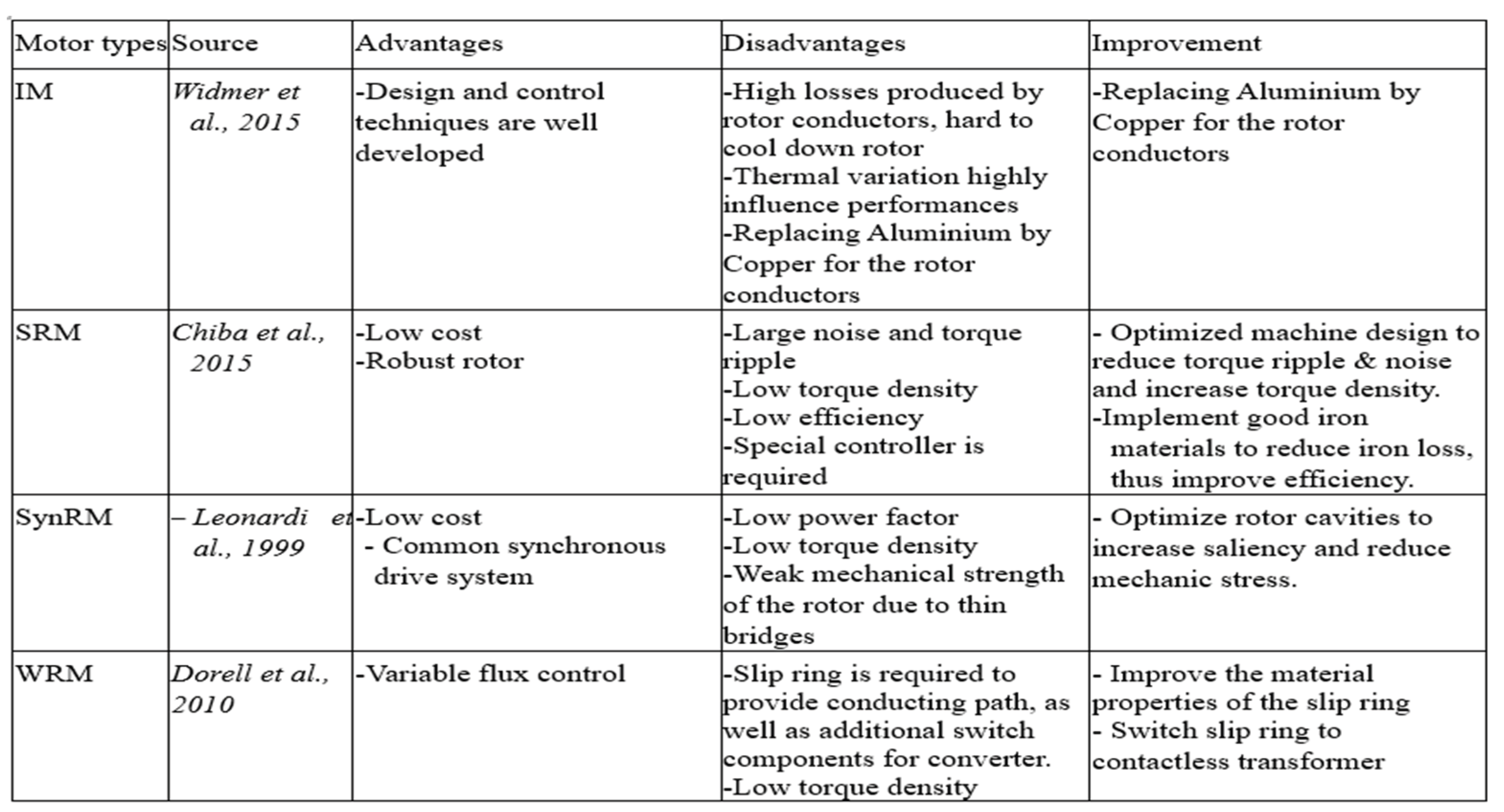

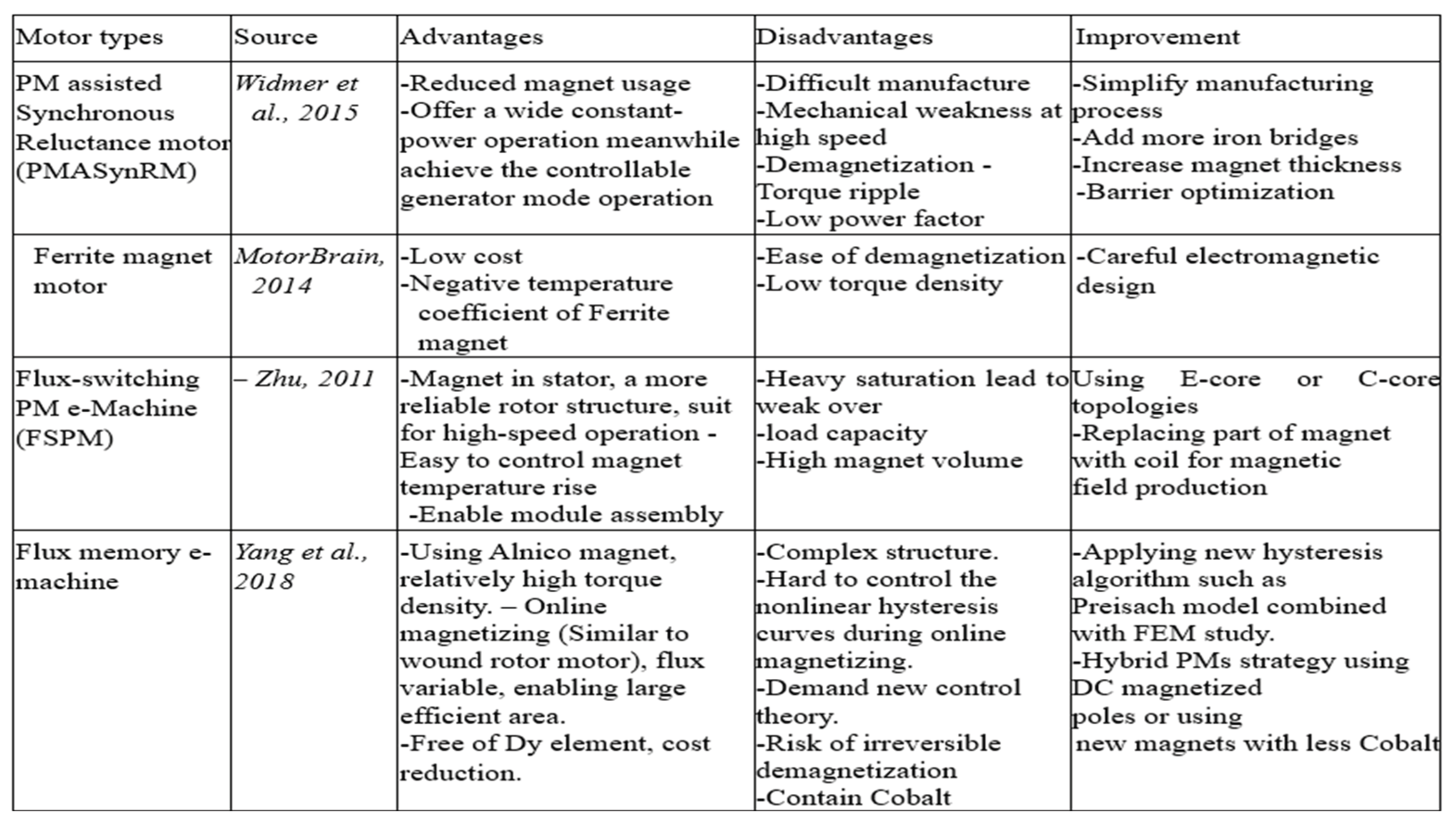

3.2.1. Types

3.3. Methodology for Motor Selection for Electric Vehicle Application:

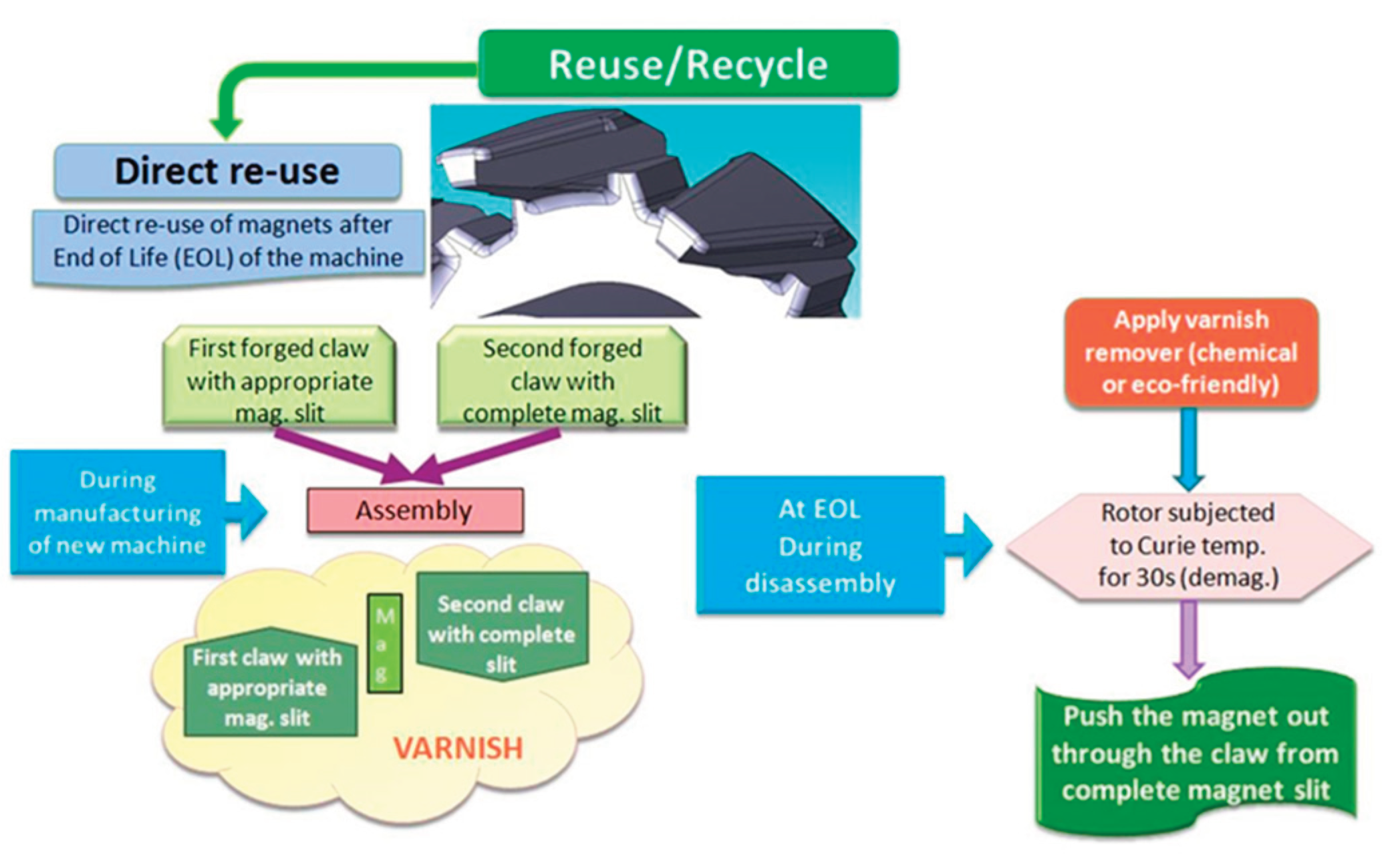

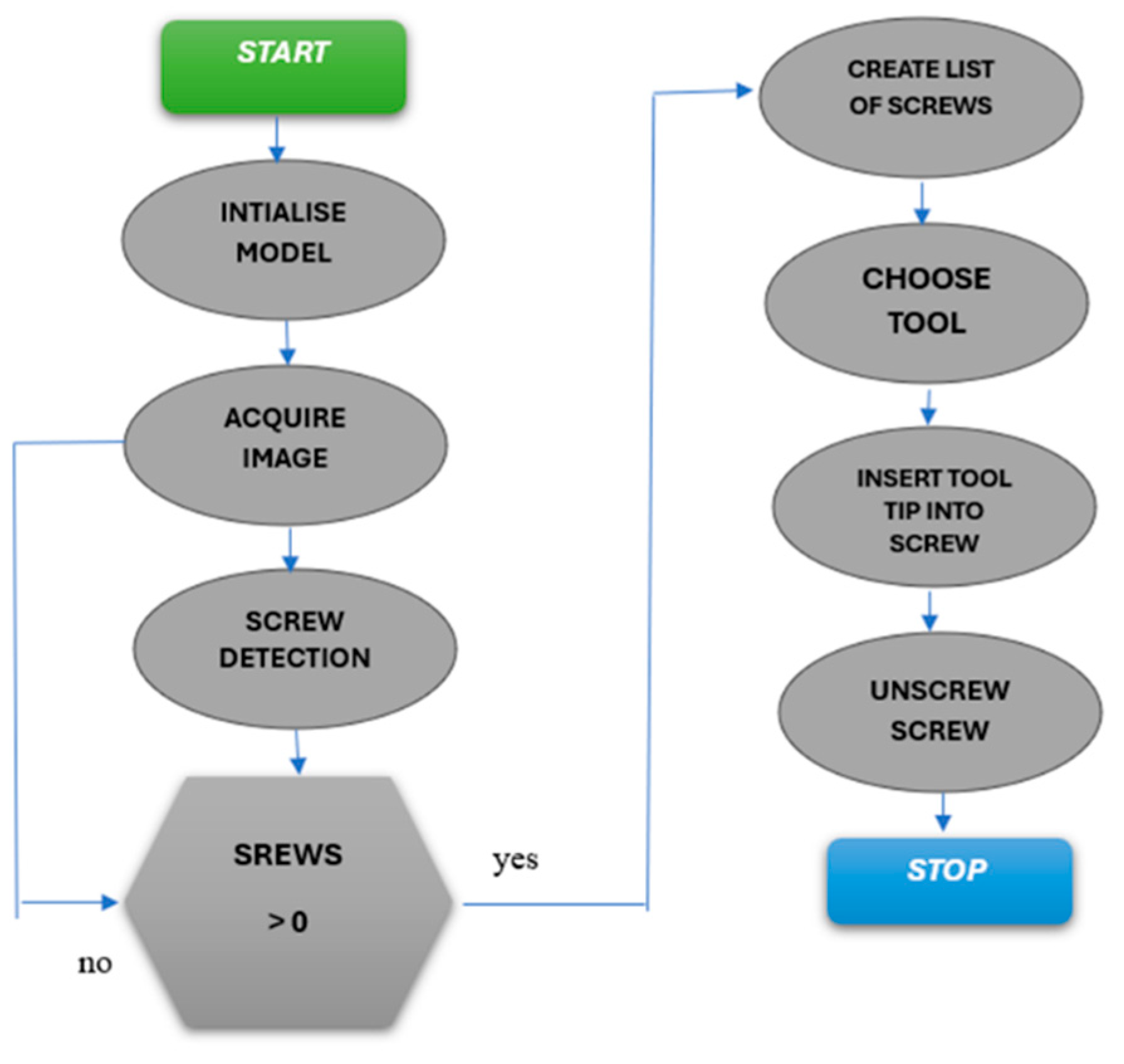

3.4. Disassembly of End of Life of Traction Motors:

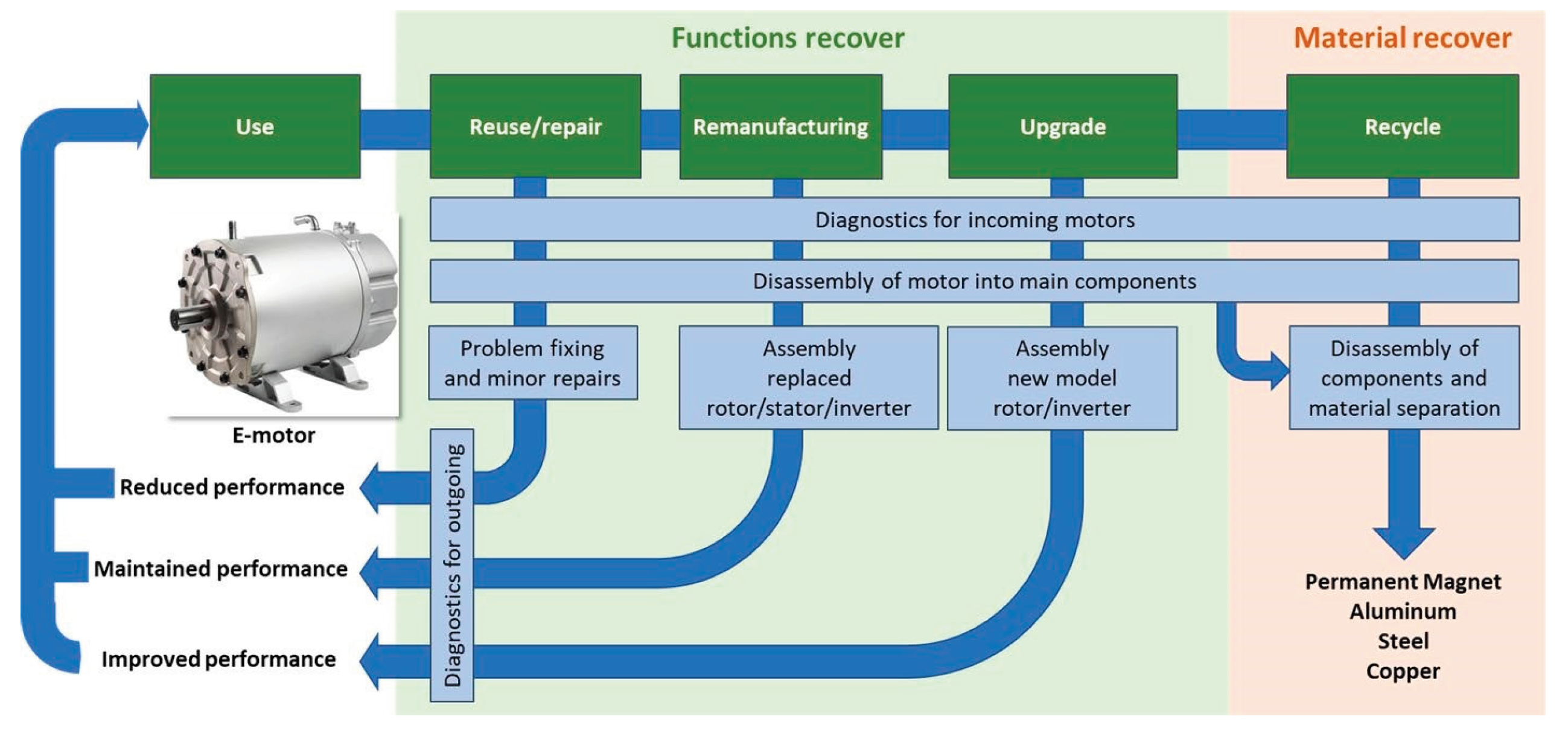

3.5. Reuse, Remanufacture and Recycle of Traction Motors:

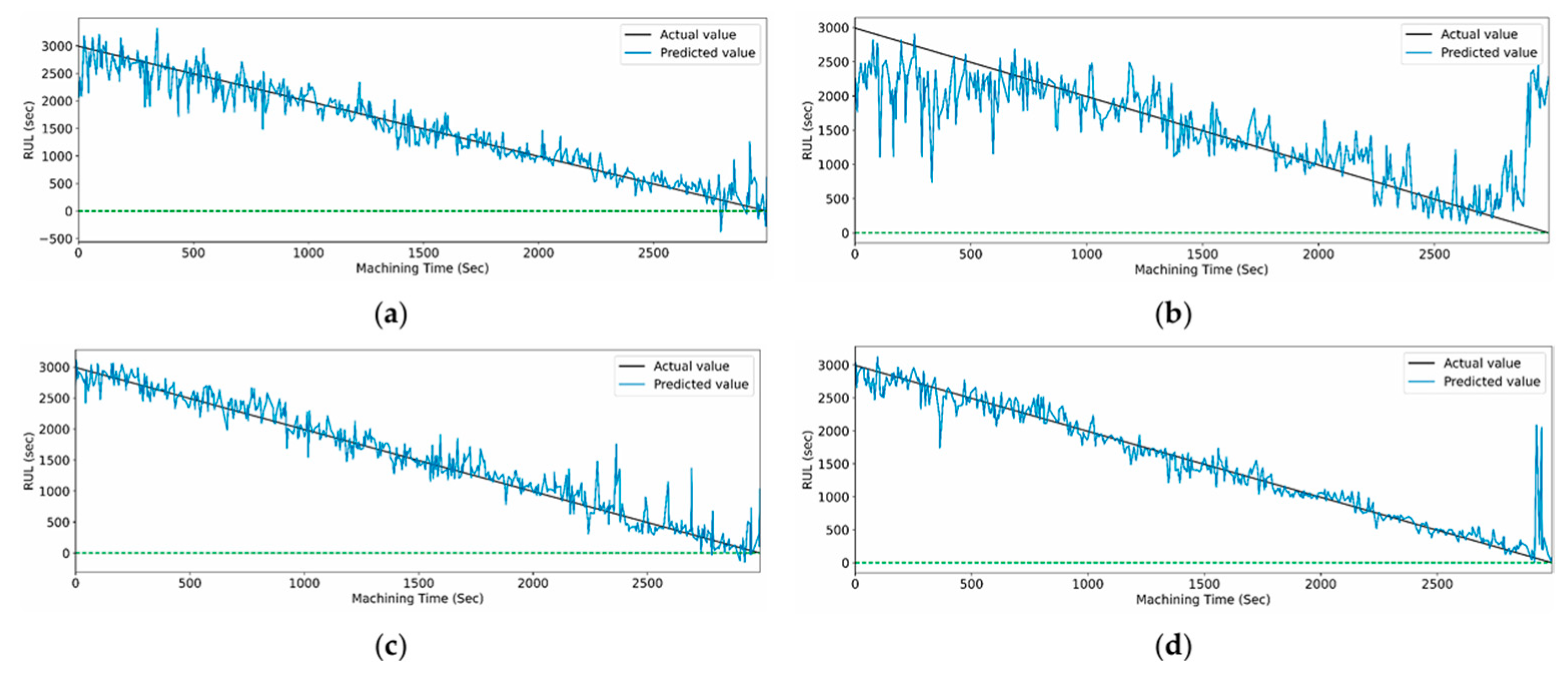

3.6. Outcomes and Insights from Machine Learning Models for RUL Prediction

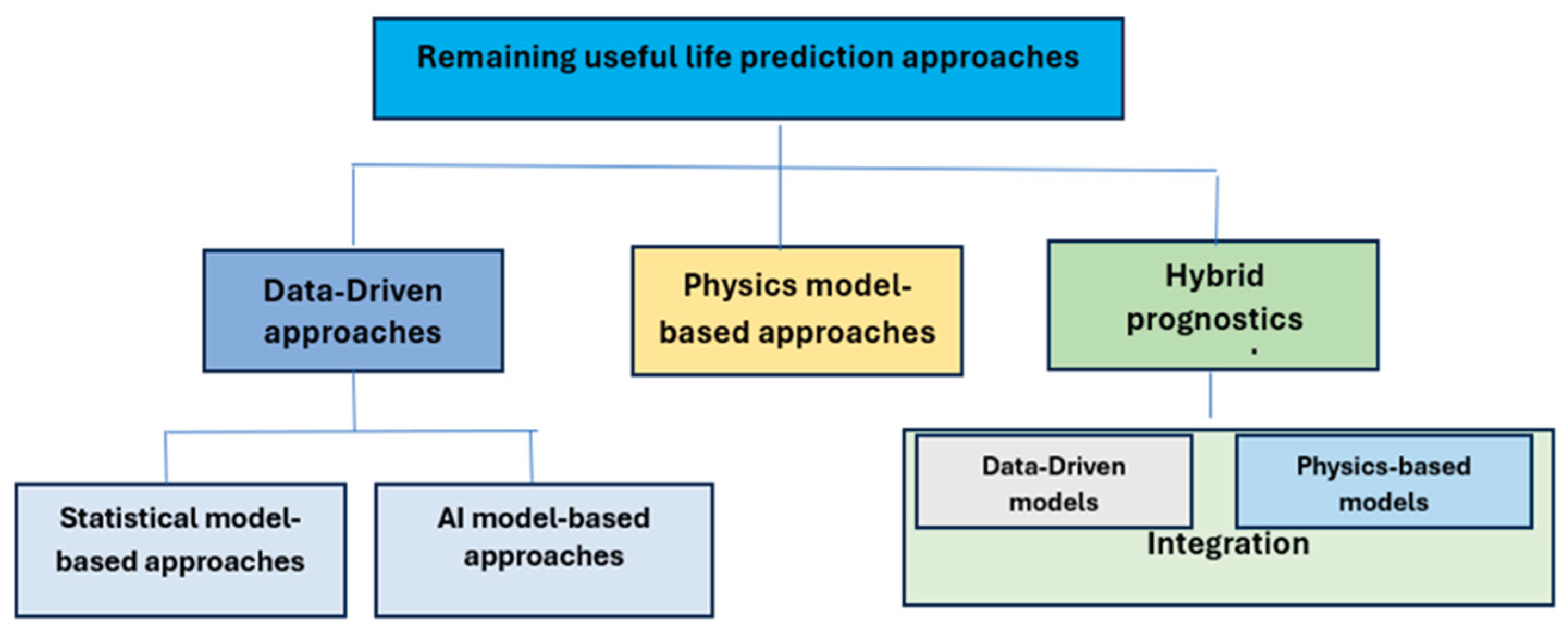

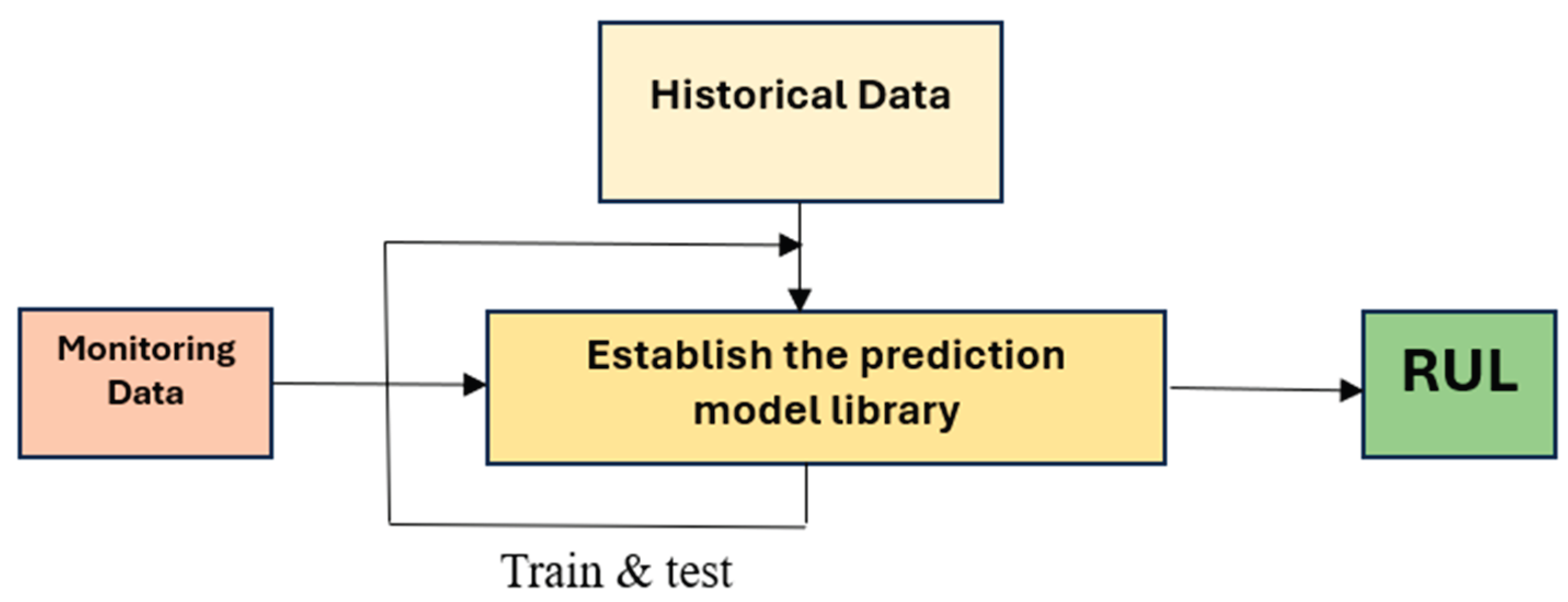

3.6.1. Classification of RULP Approaches

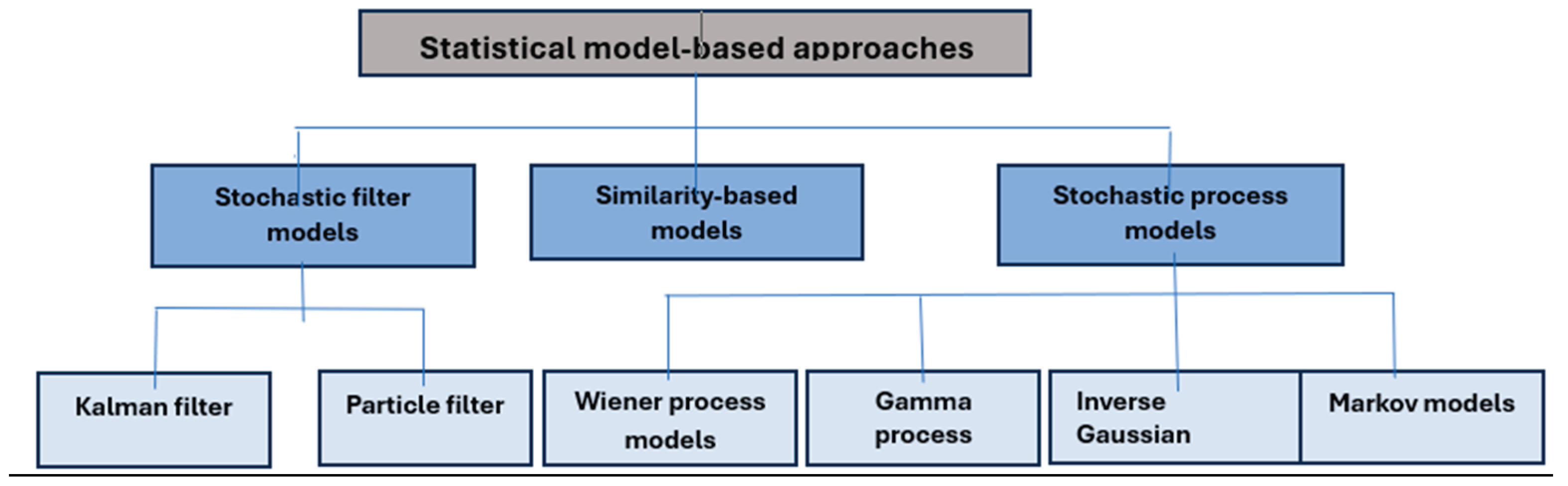

3.6.1.1. Statistical Model-Based

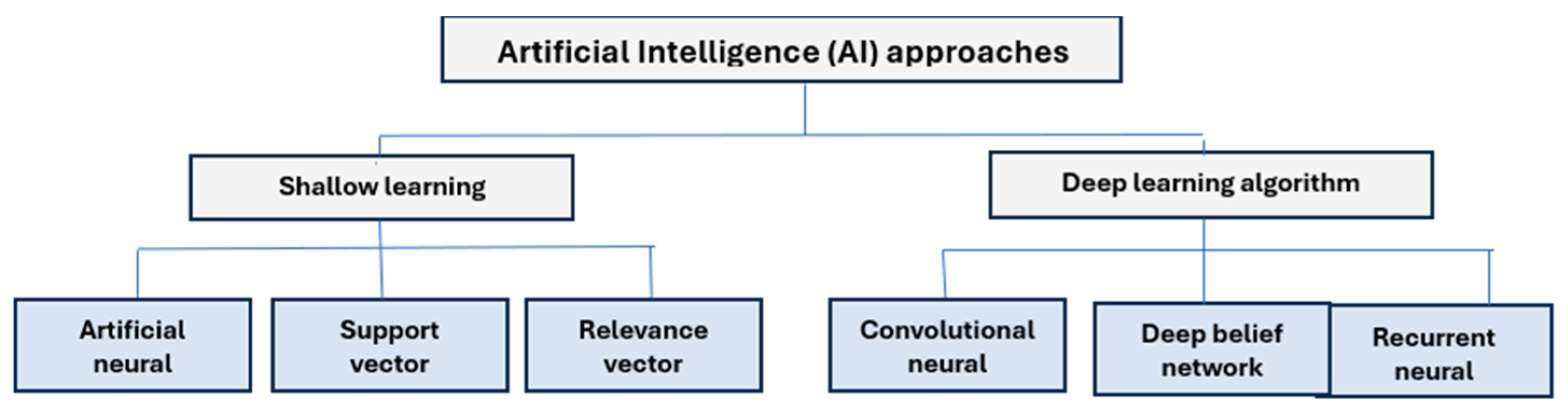

3.6.1.2. Artificial Intelligence

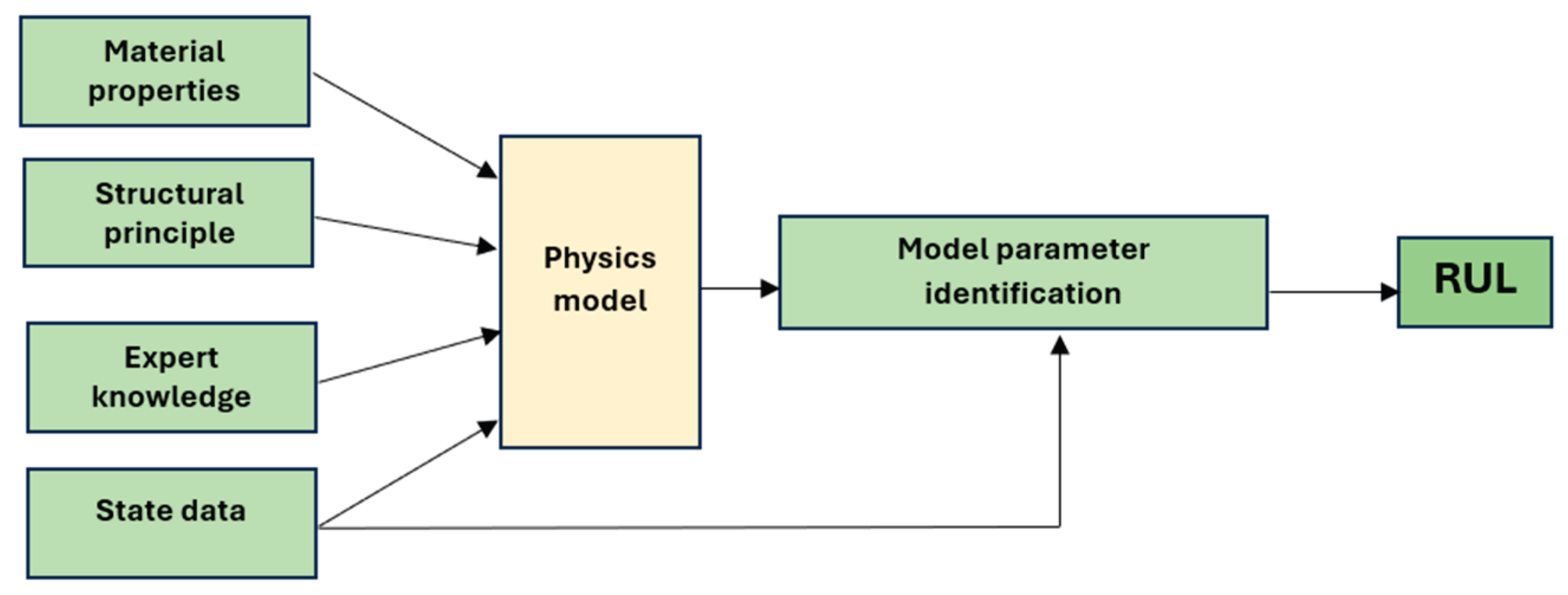

3.6.1.3. Physics Model-Based

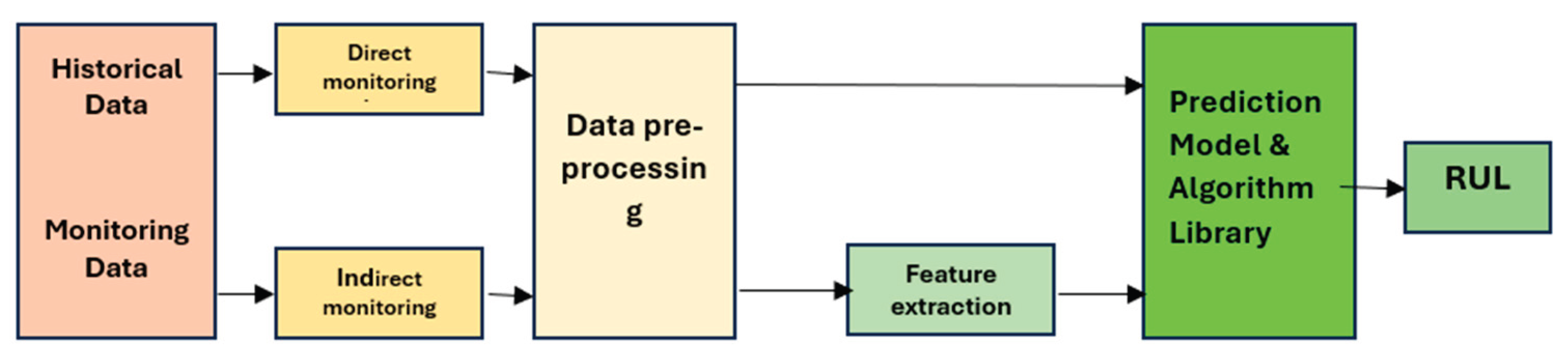

3.6.2. Model Development and Training Procedure

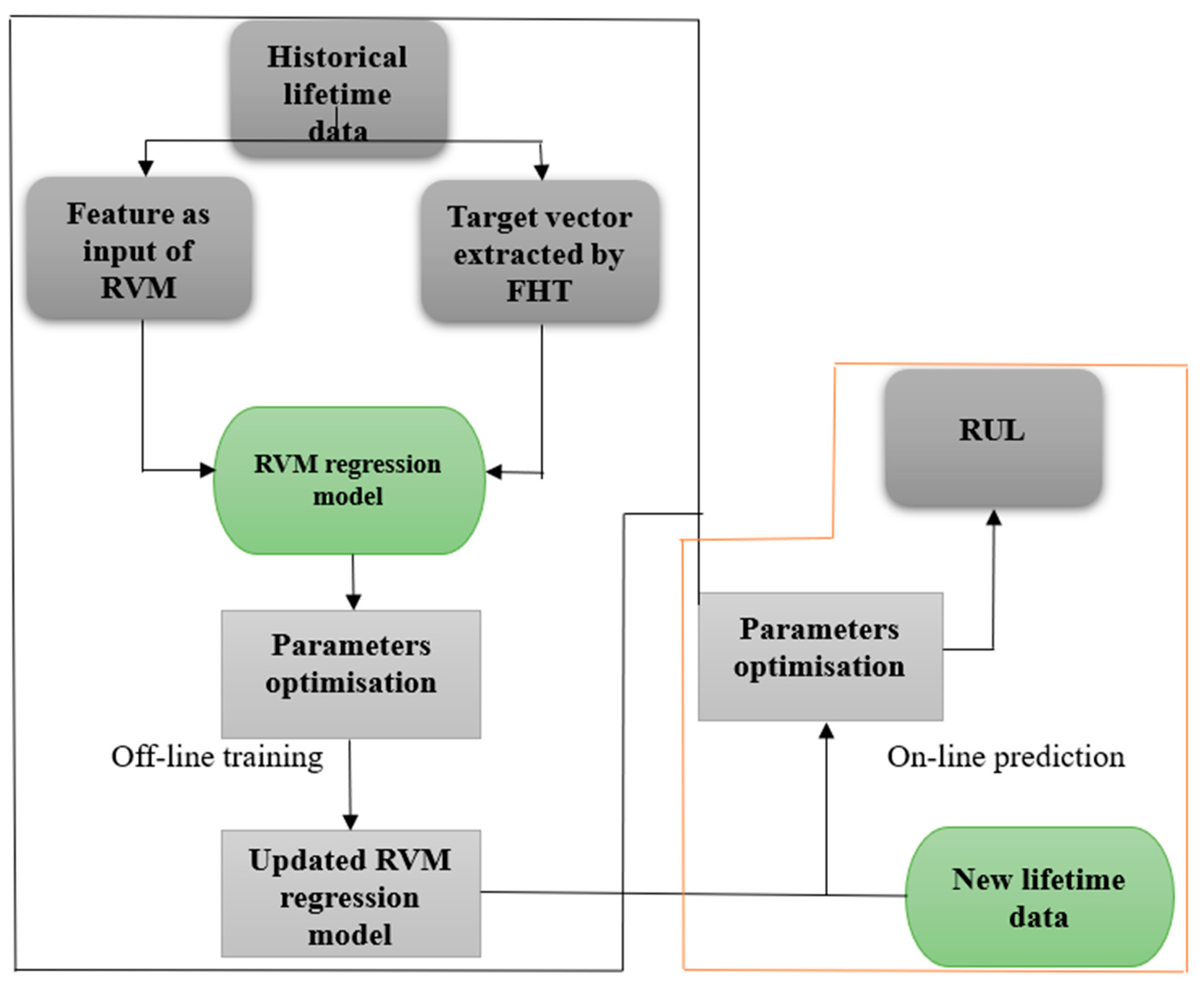

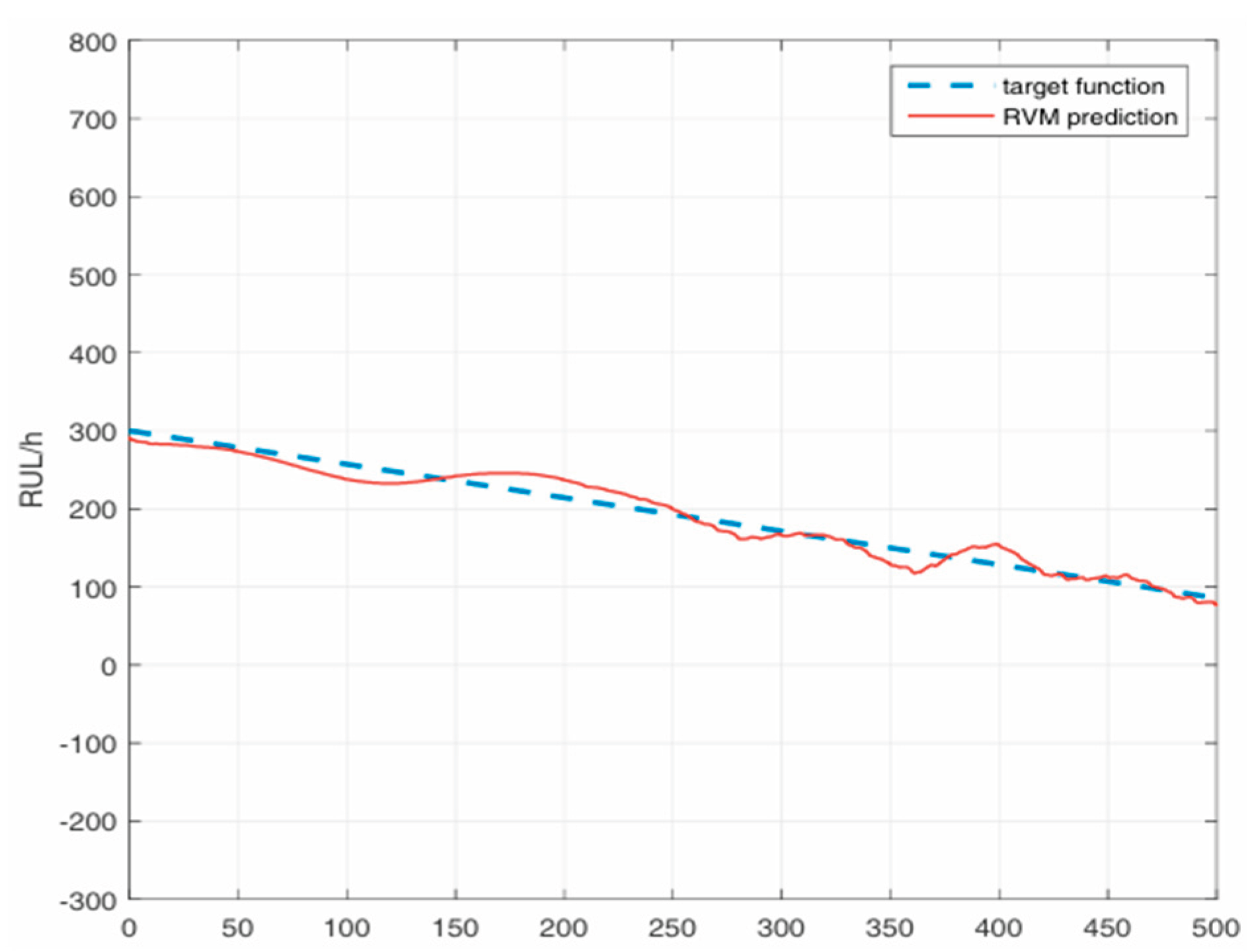

3.6.2.1. RVM-Based RUL Prediction Method

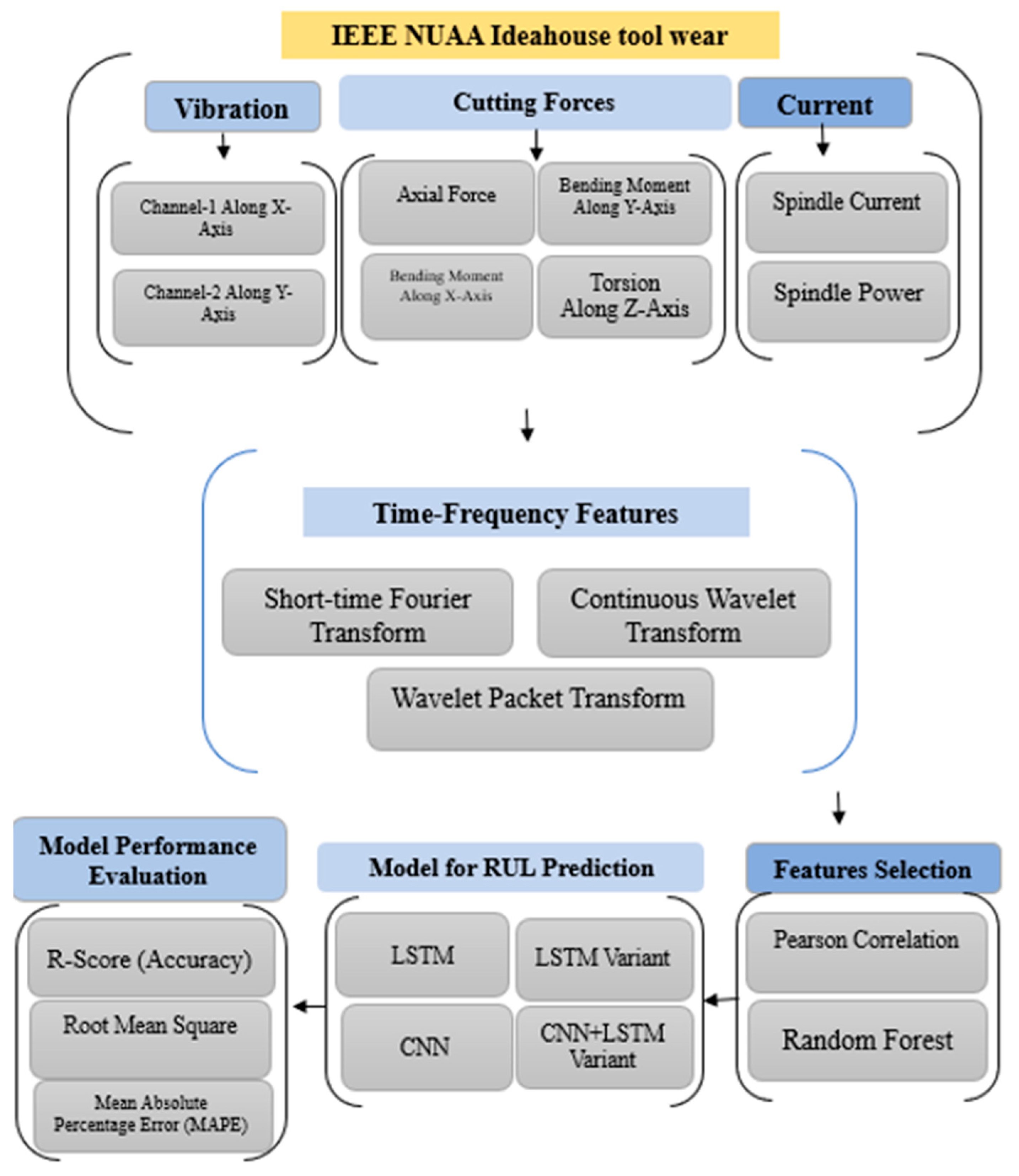

3.6.2.2. Stage Data-Driven Pipeline for Milling Tool RUL Prediction

3.6.2.3. Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) Evidence from Literature

3.6.2.4. Strengths

3.6.2.5. Limits

3.6.3. Other Models Include

3.7. Challenges and Solutions in CE for EMs Using Industry 4.0 Technologies.

3.8. Challenges Associated with Traction Motors

3.9. Future Trends, Existing Gaps, and Research Guidelines

3.10. SWOT matrix of the recycling PM motors [2].

References

- Alex, G., Navdeep, J., & Abdel-rahman, M. (2013). 2013 IEEE Workshop on Automatic Speech Recognition and Understanding.

- Al-Refaie, A., Al-atrash, M., & Lepkova, N. (2025). Prediction of the remaining useful life of a milling machine using machine learning. MethodsX, 14. [CrossRef]

- APRA. (2012, April 3). Remanufacturing Terminology. Https://Www.Apraeurope.Org/Remanufacturing.

- Ballo, F., Gobbi, M., Mastinu, G., & Palazzetti, R. (2023). Noise and Vibration of Permanent Magnet Synchronous Electric Motors: A Simplified Analytical Model. IEEE Transactions on Transportation Electrification, 9(2), 2486–2496. [CrossRef]

- Bdiwi, M., Rashid, A., & Putz, M. (2016). Autonomous disassembly of electric vehicle motors based on robot cognition. 2016 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA).

- Cai, W., Wu, X., Zhou, M., Liang, Y., & Wang, Y. (2021a). Review and Development of Electric Motor Systems and Electric Powertrains for New Energy Vehicles. Automotive Innovation, 4(1), 3–22. [CrossRef]

- Cai, W., Wu, X., Zhou, M., Liang, Y., & Wang, Y. (2021b). Review and Development of Electric Motor Systems and Electric Powertrains for New Energy Vehicles. Automotive Innovation, 4(1), 3–22. [CrossRef]

- Casper, R., & Sundin, E. (2021). Electrification in the automotive industry: effects in remanufacturing. Journal of Remanufacturing, 11(2), 121–136. [CrossRef]

- Chang, M. M. L., Ong, S. K., & Nee, A. Y. C. (2017). Approaches and Challenges in Product Disassembly Planning for Sustainability. Procedia CIRP, 60, 506–511. [CrossRef]

- De Almeida, A. T., Ferreira, F. J. T. E., & Baoming, G. (2014). Beyond induction motors - technology trends to move up efficiency. IEEE Trans Ind Appl 50(3):2103–2114. . Https:// Doi. Org/ 10. 1109/ TIA. 2013. 22884 25.

- De Fazio, F., Bakker, C., Flipsen, B., & Balkenende, R. (2021). The disassembly map: a new method to enhance design for product repairability. J Clean Prod 320:128552. https:// doi. org/ 10. 1016/j. jclep ro. 2021. 128552.

- Deng, Y., Liu, Y., Zhang, D., & Cao, Z. (2025). A hybrid gradient boosting model for predicting longitudinal dispersion coefficient in natural rivers. Water Resources Management, 1–21.

- Dholu, N., Nagel, J. R., Cohrs, D., & Rajamani, R. K. (2017). Eddy Current Separation of Nonferrous Metals Using a Variable-Frequency Electromagnet. KONA Powder and Particle Journal, 34(0), 2017012. [CrossRef]

- Di Gerlando, A., Gobbi, M., Magnanini, M. C., Mastinu, G., Palazzetti, R., Sattar, A., & Tolio, T. (2024a). Circularity potential of electric motors in e - mobility : methods , technologies , challenges. In Journal of Remanufacturing (Issue 0123456789). Springer Netherlands. [CrossRef]

- Di Gerlando, A., Gobbi, M., Magnanini, M. C., Mastinu, G., Palazzetti, R., Sattar, A., & Tolio, T. (2024b). Circularity potential of electric motors in e-mobility: methods, technologies, challenges. In Journal of Remanufacturing (Vol. 14, Issue 2, pp. 315–357). Springer Science and Business Media B.V. [CrossRef]

- Ehsani, M., Gao, Y., & Emadi, A. (2017). Modern Electric, Hybrid Electric, and Fuel Cell Vehicles (M. Ehsani, Y. Gao, & A. Emadi, Eds.). CRC Press. [CrossRef]

- Elwert, T., Goldmann, D., Römer, F., Buchert, M., Merz, C., Schueler, D., & Sutter, J. (2016). Current developments and challenges in the recycling of key components of (Hybrid) electric vehicles. In Recycling (Vol. 1, Issue 1, pp. 25–60). MDPI AG. [CrossRef]

- Elwert, T., Goldmann, D., Romer, F., Buchert, M., Merz, C., Schueler, D., & Sutter, J. (2016). Current developments and challenges in the recycling of key components of (hybrid) electric vehicles. .

- Errington, M., & Childe, S. J. (2013). A business process model of inspection in remanufacturing. Journal of Remanufacturing, 3(1). [CrossRef]

- European-Commision. (2020). Communication from the commission to the European parliament, the council, the European economic and social committee and the committee of the regions. Critical Raw Materials Resilience: Charting a Path towards greater Security and Sustainability.

- Features in Histogram Gradient Boosting Trees Preparing the data. (n.d.).

- Fiagbe, Y. (2014). Potential of remanufacturing industry in ghana. Research Gate, June, 15.

- Ford Motor Company. (2017). Ford Sustainability Report. Https://Corporate.Ford.Com/Content/Dam/Corporate/En/Company/2014-15-SustainabilityReport.Pdf.

- Guo, Y., Ba, X., Liu, L., Lu, H., Lei, G., Yin, W., & Zhu, J. (2023). A Review of Electric Motors with Soft Magnetic Composite Cores for Electric Drives. Energies, 16(4). [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Millán, R., & Pacheco-Pimentel, J. R. (2017a). Recycling rotating electrical machines. Revista Facultad de Ingenieria, 2017(83), 50–56. [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Millán, R., & Pacheco-Pimentel, J. R. (2017b). Recycling rotating electrical machines. Revista Facultad de Ingenieria, 2017(83), 50–56. [CrossRef]

- Hogberg, S., Pedersen, T. S., Jensen, B. B., Mijatovic, N., & Holboll, J. (2016). Direct Reuse of Rare Earth Permanent Magnets. . Wind Turbine Generator Case Study, ICEM.

- Jha, A. K., Garbuio, L., Kedous-Lebouc, A., Yonnet, J. P., & Dubus, J. M. (2017). Design and comparison of outer rotor bonded magnets Halbach motor with different topologies. . In Electrical Machines, Drives and Power Systems” ELMA, 15th International Conference on (Pp. 6-10). IEEE.

- Jin, H., Afiuny, P., McIntyre, T., Yih, Y., & Sutherland, J. W. (2016). Comparative Life Cycle Assessment of NdFeB Magnets: Virgin Production versus Magnet-to-Magnet Recycling. Procedia CIRP, 48, 45–50. [CrossRef]

- Katona, M., Bányai, D. G., Németh, Z., Kuczmann, M., & Orosz, T. (2024). Remanufacturing a Synchronous Reluctance Machine with Aluminum Winding: An Open Benchmark Problem for FEM Analysis. Electronics (Switzerland), 13(4). [CrossRef]

- Klier, T., Risch, F., & Franke, J. (2013). Disassembly strategies for recovering valuable magnet material of electric drives. 2013 3rd International Electric Drives Production Conference (EDPC), 1–3. [CrossRef]

- Krishnamoorthy, S., & Panikkar, P. P. K. (2024). A comprehensive review of different electric motors for electric vehicles application. International Journal of Power Electronics and Drive Systems, 15(1), 74–90. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R., Gupta, M., & Singh, U. (2023). Precision Agriculture Crop Recommendation System Using KNN Algorithm. 2023 International Conference on IoT, Communication and Automation Technology, ICICAT 2023. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V., Sezersan, I., Garza-Reyes, J. A., Gonzalez, E. D., & Moh’d Anwer, A. S. (2019). Circular economy in the manufacturing sector: Benefits, Opportunities and Barriers. Manag. Decis. 57, 1067–1084.

- Li, B., Li, R., Sun, T., Gong, A., Tian, F., Khan, M. Y. A., & Ni, G. (2023). Improving LSTM hydrological modeling with spatiotemporal deep learning and multi-task learning: A case study of three mountainous areas on the Tibetan Plateau. Journal of Hydrology, 620. [CrossRef]

- Li, C., Xu, D., & Wang, G. (2017). High efficiency remanufacturing of induction motors with interior permanent-magnet rotors and synchronous-reluctance rotors. 2017 IEEE Transportation Electrification Conference and Expo, Asia-Pacific, ITEC Asia-Pacific 2017, 4–9. [CrossRef]

- Li, Z., Hamidi, A. S., Yan, Z., Sattar, A., Hazra, S., Soulard, J., Guest, C., Ahmed, S. H., & Tailor, F. (2024a). A circular economy approach for recycling Electric Motors in the end-of-life Vehicles: A literature review. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 205(June), 1–41. [CrossRef]

- Li, Z., Hamidi, A. S., Yan, Z., Sattar, A., Hazra, S., Soulard, J., Guest, C., Ahmed, S. H., & Tailor, F. (2024b). A circular economy approach for recycling Electric Motors in the end-of-life Vehicles: A literature review. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 205(February), 107582. [CrossRef]

- Lindkvist, Haziri, L., & Sundin, E. (2020). Supporting design for remanufacturing. A framework for implementing information feedback from remanufacturing to product design. Journal of Remanufacturing 10(1):57–76. Https:// Doi. Org/ 10. 1007/ S13243- 019- 00074-7.

- Liu, H., Xiao, Q., Jin, Y., Mu, Y., Meng, J., Zhang, T., Jia, H., & Teodorescu, R. (2022). Improved LightGBM-Based Framework for Electric Vehicle Lithium-Ion Battery Remaining Useful Life Prediction Using Multi Health Indicators. Symmetry, 14(8). [CrossRef]

- Liu, L., Wang, L., & Yu, Z. (2021). Remaining Useful Life Estimation of Aircraft Engines Based on Deep Convolution Neural Network and LightGBM Combination Model. International Journal of Computational Intelligence Systems, 14(1). [CrossRef]

- Lucchini, F., Torchio, R., & Bianchi, N. (2024). A Survey on the Sustainability of Traditional and Emerging Materials for Next-Generation EV Motors. Energies, 17(23), 1–19. [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, P., Ramakrishnan, A., Anand, G., Vig, L., Agarwal, P., & Shroff, G. (2016). LSTM-based Encoder-Decoder for Multi-sensor Anomaly Detection. http://arxiv.org/abs/1607.00148.

- Mangold, S., Steiner, C., Friedmann, M., & Fleischer, J. (2022). Vision-Based Screw Head Detection for Automated Disassembly for Remanufacturing. Procedia CIRP, 105, 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Mayer, D., Hausmann, L., Maul N., Reinschmidt, L., Hofmann, J., & Fleischer, J. (2019). Systematic investigation of the grooving process and its influence on slot insulation of stators with hairpin technology. 9th International Electric Drives Production Conference (EDPC). IEEE. Https:// Doi. Org/ 10. 1109/ EDPC4 8408. 2019. 90119 35, 1–7.

- Meng, X., Cai, C., Wang, Y., Wang, Q., & Tan, L. (2022). Remaining useful life prediction of lithium-ion batteries using CEEMDAN and WOA-SVR model. Frontiers in Energy Research, 10. [CrossRef]

- Mulcahy, K. R., Kilpatrick, A. F. R., Harper, G. D. J., Walton, A., & Abbott, A. P. (2022). Debondable adhesives and their use in recycling. Green Chemistry, 24(1), 36–61. [CrossRef]

- Nachrichten. (2023). idw-Informationsdienst Wissenschaft idw-Informationsdienst Wissenschaft Press release Fraunhofer-Institut für Produktionstechnik und Automatisierung IPA Dr. Karin Röhricht New technologies for the disassembly of electric vehicle batteries and motors. http://idw-online.de/en/news814619.

- Ngu, H. J., Lee, M. D., & Bin Osman, M. S. (2020). Review on current challenges and future opportunities in Malaysia sustainable manufacturing: Remanufacturing industries. In Journal of Cleaner Production (Vol. 273). Elsevier Ltd. [CrossRef]

- Önal, M. A. R. (2017). Recycling of NdFeB magnets for rare earth elements (REE) recovery. KU Leuven, Leuven. Https://Www.Mtm.Kuleuven.Be/Onderzoek/Semper/Hitemp/Publications/Doctoraltheses/Recaional.

- Pell, R., Wall, F., Yan, X., Li, J., & Zeng, X. (2019). Temporally explicit life cycle assessment as an environmental performance decision making tool in rare earth project development. Minerals Engineering, 135, 64–73. [CrossRef]

- Pérez, M., Lieder, M., Jeong, Y., & Asif, F. M. A. (2025). A simulation-based decision support tool for circular manufacturing systems in the automotive industry using electric machines as a remanufacturing case study. International Journal of Production Research. [CrossRef]

- Redlinger, M., Eggert, R., & Woodhouse, M. (2015). Evaluating the availability of gallium, indium, and tellurium from recycled photovoltaic modules. Solar Energy Materials and Solar Cells, 138, 58–71. [CrossRef]

- Saiz, F. A., Alfaro, G., & Barandiaran, I. (2021). An inspection and classification system for automotive component remanufacturing industry based on ensemble learning. Information (Switzerland), 12(12). [CrossRef]

- Sayyad, S., Kumar, S., Bongale, A., Kotecha, K., & Abraham, A. (2023). Remaining Useful-Life Prediction of the Milling Cutting Tool Using Time–Frequency-Based Features and Deep Learning Models. Sensors, 23(12). [CrossRef]

- Sekhar, J. N. C., Domathoti, B., & Santibanez Gonzalez, E. D. R. (2023). Prediction of Battery Remaining Useful Life Using Machine Learning Algorithms. Sustainability (Switzerland), 15(21). [CrossRef]

- Soh, S., Ong, S. K., & Nee, A. Y. C. (2016). Design for assembly and disassembly for remanufacturing. . 12–24. [CrossRef]

- Taheri, F., Sauve, G., & Van Acker, K. (2024). Circular economy strategies for permanent magnet motors in electric vehicles: Application of SWOT. In Procedia CIRP (Vol. 122). Elsevier B.V. [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, D., Miscandlon, J., Tiwari, A., & Jewell, G. W. (2021a). A review of circular economy research for electric motors and the role of industry 4.0 technologies. Sustainability (Switzerland), 13(17). [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, D., Miscandlon, J., Tiwari, A., & Jewell, G. W. (2021b). A review of circular economy research for electric motors and the role of industry 4.0 technologies. Sustainability (Switzerland), 13(17), 1–19. [CrossRef]

- Tolio, T., Bernard, A., Colledani, M., Kara, S., Seliger, G., & Duflou, J. (2017). Design, management and control of demanufacturing and remanufacturing systems. CIRP Ann 66(2):585–609. . Https:// Doi. Org/ 10. 1016/j. Cirp. 2017. 05. 001.

- Toyota Motors Corporation. Vehicle Recycling. . (2014). Retrieved from Toyota City, Japan: Http://Www.Toyota-Global.Com/Sustainability/Report/Vehicle_recycling/Pdf/Vr_all.Pdf.

- Trading Economics. (2023, December 15). Lithium Carbonate. . URL: Htt Ps://Tradingeconomics.Com/Commodity/Lithium.

- Upadhayay, P., Awais, M., Lebouc, A. K., Garbuio, L., Degri, M., Walton, A., Mipo, J. C., & Dubus, J. M. (2018). Applicability of Direct Reuse and Recycled Rare Earth Magnets in Electro-mobility. 7th International IEEE Conference on Renewable Energy Research and Applications, ICRERA 2018, 5, 846–852. [CrossRef]

- Van Loon, P., Diener, D., & Harris, S. (2021). Circular products and business models and environmental impact reductions: current knowledge and knowledge gaps. . J Clean Prod 288:125627. Https:// Doi. Org/ 10. 1016/j. Jclep Ro. 2020. 125627.

- Vimala, M., Toby, T., Vikram, S., B Maheswara, R., & M Goutham, K. (2017). Prediction of Remaining Useful Lifetime (RUL) of Turbofan Engine using Machine Learning.

- Wang, X., Jiang, B., Lu, N., & Cocquempot, V. (2018). Accurate Prediction of RUL under Uncertainty Conditions: Application to the Traction System of a High-speed Train. 51(24), 401–406. [CrossRef]

- Wei, W., Li, X., Liu, J., Zhou, Y., Li, L., & Zhou, J. (2021). Performance evaluation of hybrid woa-svr and hho-svr models with various kernels to predict factor of safety for circular failure slope. Applied Sciences (Switzerland), 11(4), 1–22. [CrossRef]

- Wen, X., & Li, W. (2023). Time Series Prediction Based on LSTM-Attention-LSTM Model. IEEE Access, 11, 48322–48331. [CrossRef]

- Weng, Z. H., Jowitt, S. M., Mudd, G. M., & Haque, N. (2013). Assessing rare earth element mineral deposit types and links to environmental impacts. Applied Earth Science, 122(2), 83–96. [CrossRef]

- Werker, J., Wulf, C., Zapp, P., Schreiber, A., & Marx, J. (2019). Social LCA for rare earth NdFeB permanent magnets. Sustainable Production and Consumption, 19, 257–269. [CrossRef]

- Widmer, J. D., Martin, R., & Kimiabeigi, M. (2015a). Electric vehicle traction motors without rare earth magnets. Sustainable Materials and Technologies, 3, 7–13. [CrossRef]

- Widmer, J. D., Martin, R., & Kimiabeigi, M. (2015b). Electric vehicle traction motors without rare earth magnets. Sustainable Materials and Technologies, 3, 7–13. [CrossRef]

- Wu, M., Goh, K. W., Chaw, K. H., Koh, Y. S., Dares, M., Yeong, C. F., Su, E. L. M., William, H., & Zhang, Y. (2024). An intelligent predictive maintenance system based on random forest for addressing industrial conveyor belt challenges. Frontiers in Mechanical Engineering, 10. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y., Tan, L., & Liu, J. (2025). Application of Machine Learning Model in Fraud Identification: A Comparative Study of CatBoost, XGBoost and LightGBM. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y., Shang, X., Chen, Z., Mei, K., Wang, Z., Dahlgren, R. A., Zhang, M., & Ji, X. (2021). A support vector regression model to predict nitrate-nitrogen isotopic composition using hydro-chemical variables. Journal of Environmental Management, 290. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y., Walton, A., Sheridan, R., Güth, K., Gauß, R., Gutfleisch, O., Buchert, M., Steenari, B. M., Van Gerven, T., Jones, P. T., & Binnemans, K. (2017). REE Recovery from End-of-Life NdFeB Permanent Magnet Scrap: A Critical Review. Journal of Sustainable Metallurgy, 3(1), 122–149. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M., Yin, J., & Chen, W. (2023). SOH estimation and RUL prediction of lithium batteries based on multidomain feature fusion and CatBoost model. Energy Science and Engineering, 11(9), 3082–3101. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q., Yang, W., Zhao, A., Wang, X., Wang, Z., & Zhang, L. (2024). Short-term forecasting of vegetable prices based on LSTM model—Evidence from Beijing’s vegetable data. PLoS ONE, 19(7 July). [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R., Zeng, Z., Li, Y., Liu, J., & Wang, Z. (2022). Research on Remaining Useful Life Prediction Method of Rolling Bearing Based on Digital Twin. Entropy, 24(11), 1578. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y., Fang, L., Qi, Z., & Deng, H. (2023). A Review of Remaining Useful Life Prediction Approaches for Mechanical Equipment. IEEE Sensors Journal, 23(24), 29991–30006. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J., Huang, F., Lv, J., Duan, Y., Qin, Z., Li, G., & Tian, G. (2020). Do RNN and LSTM have Long Memory?

- Zhao, Q., Qin, X., Zhao, H., & Feng, W. (2018). A novel prediction method based on the support vector regression for the remaining useful life of lithium-ion batteries. Microelectronics Reliability, 85, 99–108. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z., Chen, W., Wu, X., Chen, P. C. Y., & Liu, J. (2017). LSTM network: A deep learning approach for Short-term traffic forecast. IET Intelligent Transport Systems, 11(2), 68–75. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y., Huang, M., & Pecht, M. (2020). Remaining useful life estimation of lithium-ion cells based on k-nearest neighbor regression with differential evolution optimization. Journal of Cleaner Production, 249, 119409. [CrossRef]

- Zohra, B., & Akar, M. (2019, October 1). Design Trends for Line Start Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motors. 3rd International Symposium on Multidisciplinary Studies and Innovative Technologies, ISMSIT 2019 - Proceedings. [CrossRef]

|

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).