1. Introduction – Global Conveyor Belt Market

Belt conveyors are mechanical systems consisting of continuous belt loops used for transporting bulk or unit materials over short to long distances, including within buildings, storage yards, assembly lines, and supply chains—sometimes across hundreds of kilometers [

1,

2].

The transported material rests on the belt's top cover and is driven by pulling forces within the core. The system typically consists of at least two pulleys, one of which drives the loop. Due to the low belt-to-material mass ratio, conveyor belts are among the most cost-effective transportation systems [

3]. Their versatility makes them widely used in mining [

4], cement manufacturing [

5], power generation [

6,

7], recycling [

8], metal processing, chemicals [

9], oils, gases, food and beverage processing [

10], general manufacturing, supply chain, automated distribution, warehousing [

11], airports [

12], and other sectors. Increasing deployment of belt systems contributes to reducing production costs, supporting overall market growth.

This growth is further fueled by technological advances, rising demand for automation, and the need for condition monitoring, diagnostics, and environmental sustainability. Electric-powered conveyors are also considered more eco-friendly than fossil-fuel alternatives. Despite market expansion, challenges remain—especially for small and medium enterprises—due to high belt procurement, installation, and maintenance costs, exacerbated by rising electricity prices, particularly in the European Union. Solutions such as belt refurbishment [

13,

14,

15], energy-saving belts [

16,

17] and structures [

18,

19,

20] and intelligent management strategies [

21,

22] are gaining importance.

The market includes textile-reinforced belts, steel cord belts, and solid woven types [

23,

24]. Textile belts (EE and EP) are projected to remain dominant due to their cost-effectiveness. Steel cord belts are favored in mining for their superior impact resistance and strength [

25,

26,

27], though rising steel prices affect market value.

While growing demand is expected in developing countries, the shift away from coal-fired power in industrialized nations presents a challenge. Conveyor belts, especially heavy-duty ones, require large quantities of raw materials, which account for 70–75% of total production costs and strongly influence product quality [

28].

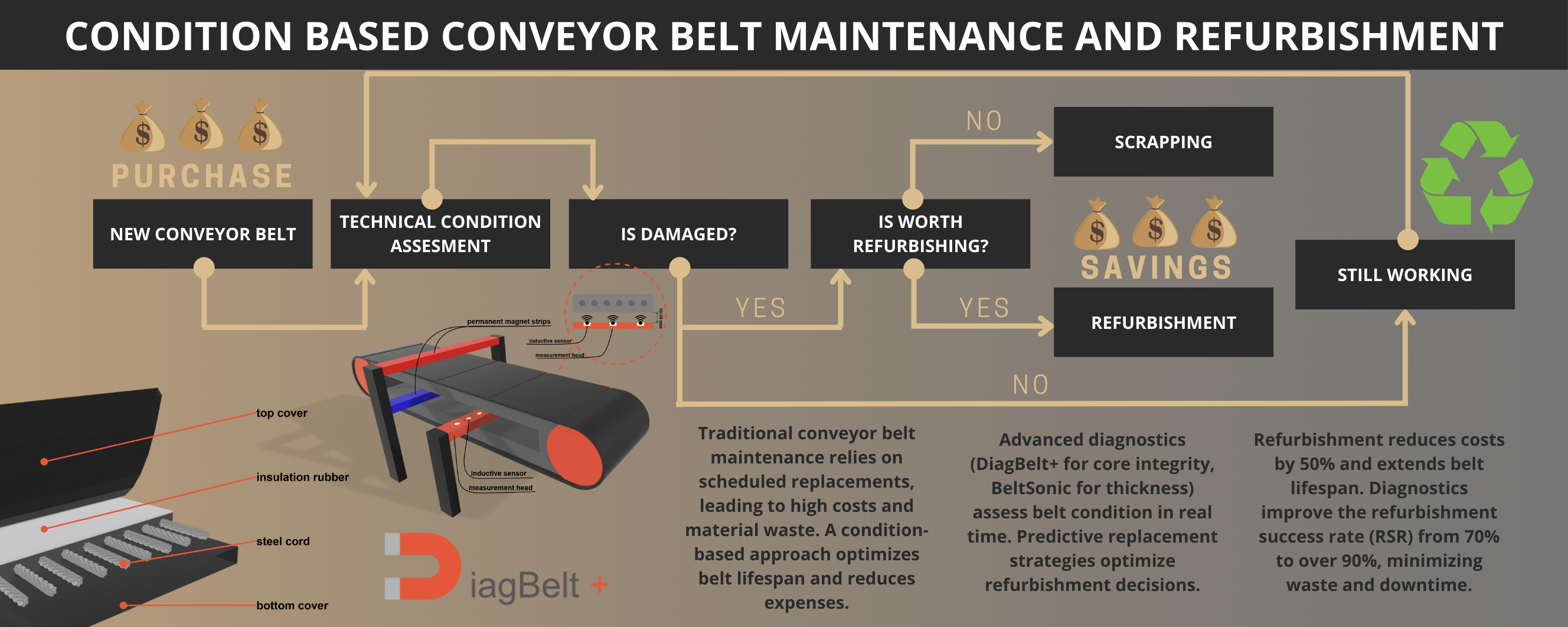

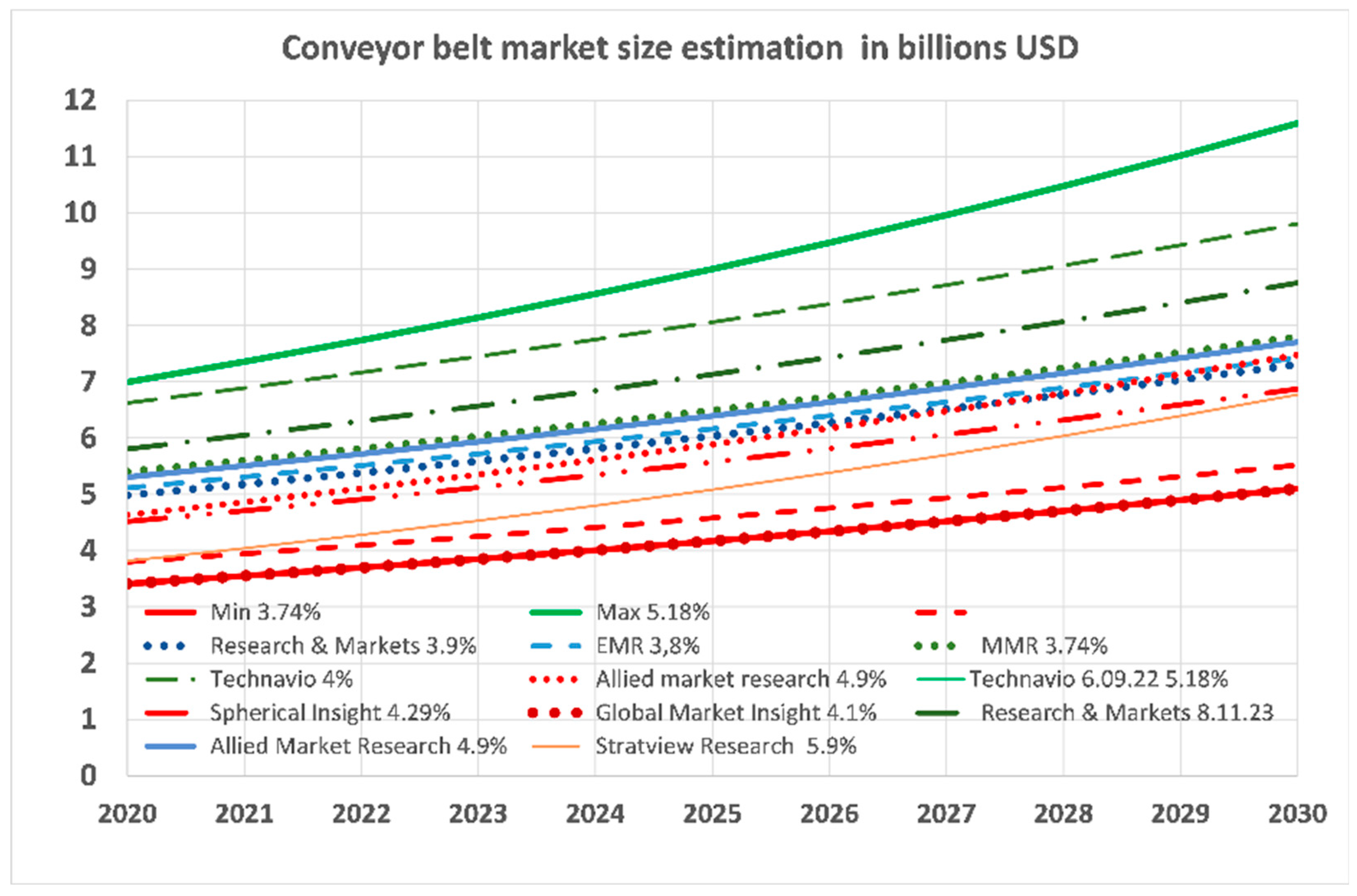

Market size estimates vary widely, ranging from over

$3 billion in 2020 to

$11.5 billion by 2030, with projected CAGR between 3.74% and 5.9%. These discrepancies stem from differing methodologies and segmentation criteria (e.g., belt types, construction materials, applications, and geography), as illustrated in

Figure 1.

As belts are the costliest component of conveyor systems, their condition must be closely monitored. Predictive diagnostics and preventive replacement strategies not only reduce downtime but also promote material reuse and sustainability.

This study investigates the economic effectiveness of preventive belt replacement within refurbishment processes. The approach has been successfully implemented in Polish lignite mines for over 50 years. The research hypothesis posits that such strategies improve economic efficiency and support sustainable raw material management.

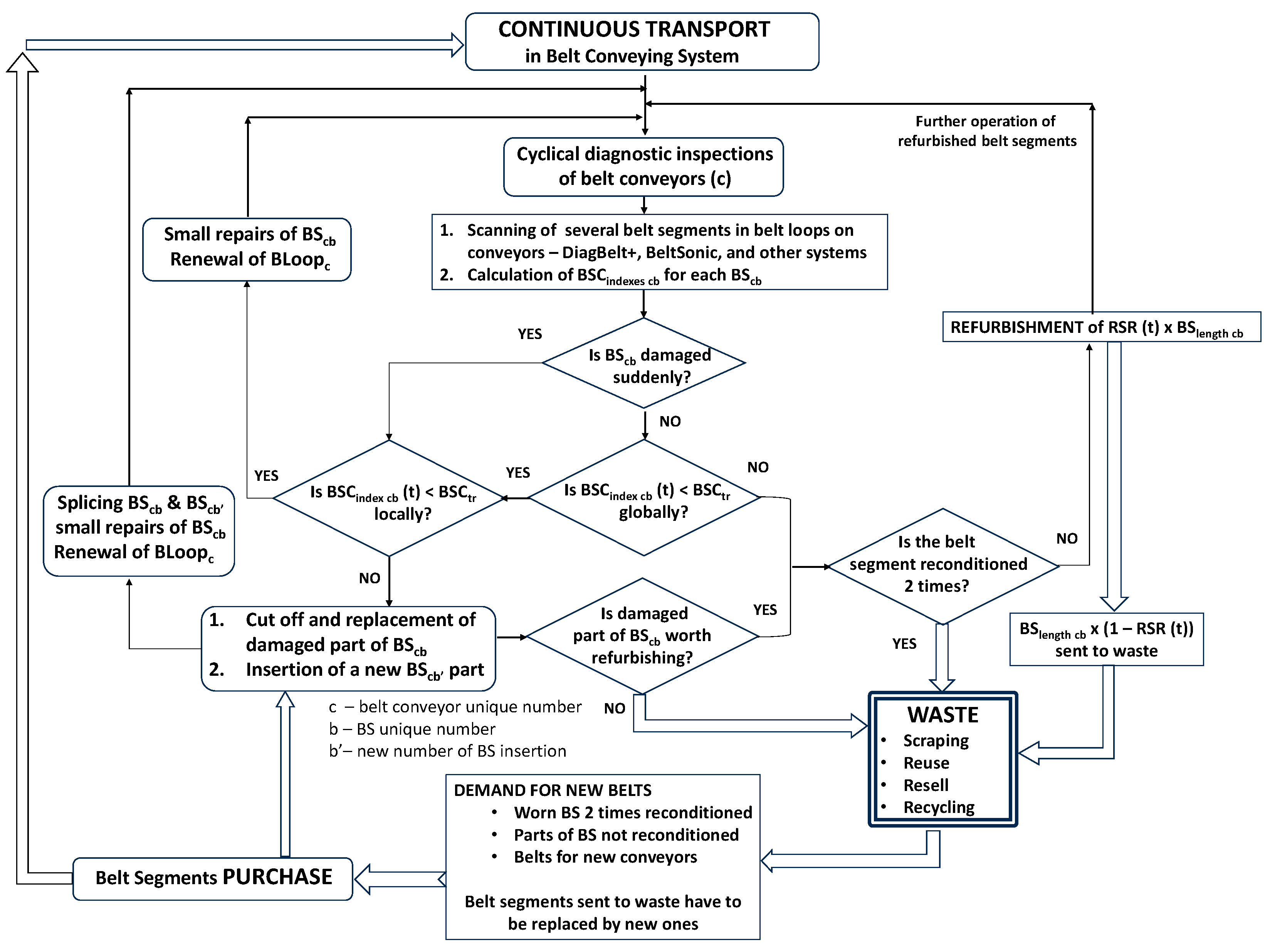

2. Strategy of Belt Replacements

The market value of conveyor belts includes both the installation of new belts on investment conveyors and the replacement of worn sections on existing ones. A belt loop on long conveyors consists of multiple spliced sections (vulcanized, adhesive, or mechanical). New loops are built from the longest possible sections to minimize the number of splices, which represent structural weak points. Belts are typically delivered on single (250–400 m) or double reels (up to 700+ m). During operation, damaged segments or joints are replaced, gradually shortening section lengths and increasing the number of splices over time [

29]. This process is referred to as belt renewal [

30,

31,

32], which may involve new, less worn, or refurbished belts.

Belt degradation is influenced by many factors: conveyor design, belt construction, material type, working conditions, and operational regime [

33,

34,

35,

36,

37]. Because these factors interact dynamically over time, belt lifetime is difficult to predict and should be treated as a random variable. Attempts to model belt durability based on operational statistics remain limited due to complexity, subjective replacement decisions, and inadequate metrics (e.g., calendar time instead of effective operational hours or transported mass) [

38,

39,

40,

41]. As a result, belt durability varies significantly, and its evaluation requires multicriteria analysis [

42,

43,

44,

45].

Furthermore, unit costs of belts with identical specifications may vary twofold. A lower price typically reflects lower material quality, but a high price doesn’t guarantee longer lifespan. Without predictive tools, durability cannot be reliably assessed in advance.

While data on the new belt market is available, the refurbished belt market remains poorly quantified. Refurbishment was once common and widely offered by major service providers. Today, only selected suppliers (e.g., Fenner, Contitech) and service firms (e.g., Bestgum in Poland) continue this service. Most users opt for new belts and consider refurbishment only after early-stage damage. Only a few, such as Polish lignite mines, apply refurbishment as a regular replacement strategy.

Failures caused by external stochastic events (e.g., punctures, cuts) may occur regardless of belt age or condition. The likelihood increases as belts wear, but accurate prediction would require extensive failure case data, which many operations do not collect or publish [

46,

47].

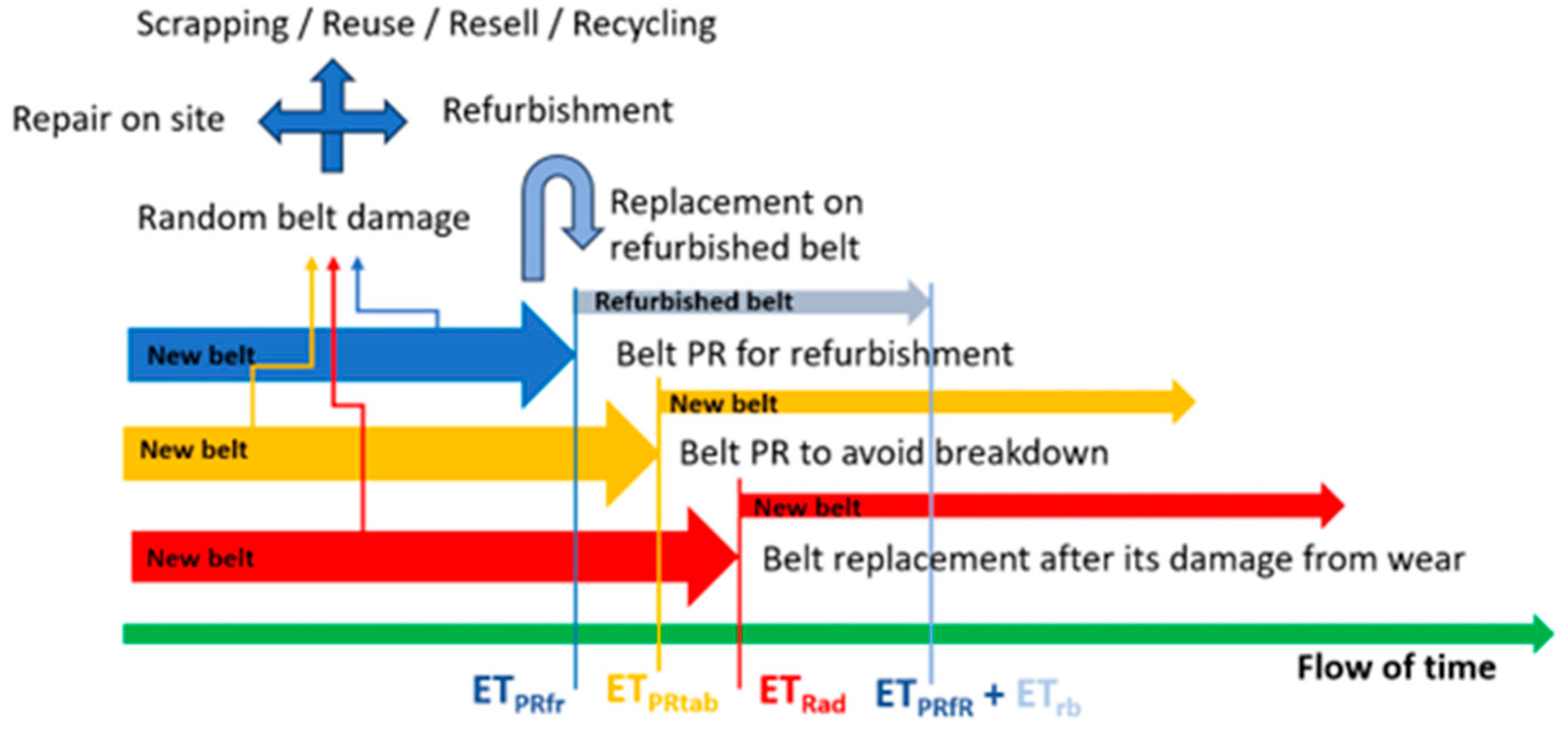

Ultimately, the decision to replace, repair, or refurbish depends on economic trade-offs. If repair downtime is shorter than replacement time, in-situ repairs are preferred. Otherwise, belts are dismantled and refurbished either on-site or in specialized plants.

Figure 2 shows the expected runtimes for different replacement policies. The earliest belts to be replaced are those replaced preventively for refurbishment. The point is to ensure that too long use of the belt does not cause damage to the belt core precludes the belt from being refurbished with success. Corrosion of the cables in the core in many places with numerous punctures will reduce the adhesion of the cables to the rubber, and the need to make many repairs may increase the costs and time of refurbishment. A reconditioned belt may not pass the tests allowing it to be used, or the refurbishment costs will be too high compared to purchasing new belts.

The belt segment can be damaged randomly at any age. In such cases, the maintenance supervisor has to decide what to do with failures. They can be repaired on site (at once, at the closest planned standstill, and later when more small failures occur). When failures require a long time to be repaired on-site and create a threat to continuous operation it is better to replace the belt fragment or the whole segment on a new one and send the belt for refurbishment. If the belt is not worth repairing it can be scrapped, or reused for another purpose (e.g. as seals, shock-absorbing linings, fenders, construction mats, marine dock bumpers, truck bed liners, grain pit covers, etc.). They can be resold to less demanding users or recycled. The last solution requires a special line for worn-out belt cover milling, cutting the core into smaller parts, scrubbing, separating etc. Such lines will be required to utilize a lot of old belts when coal mines are closed shortly.

Decisions regarding sending the belt for refurbishment must be economically justified. If the cost of refurbishment the belt is

, and the cost of purchasing a new belt is

, then the unit cost of using a new belt will be the quotient

, and for the refurbished belt, it will be

. Refurbishment is cost-effective if both conditions (1) and (2) are met.

If the cost of refurbishment is 50% of the price of a new belt, then even when their lifespan is shorter than that of new belts but exceeds 50%, the use of refurbishment is cost-effective. Because not all belts sent for refurbishment can be successfully reconditioned, the relationship should be modified by introducing a refurbishment success rate indicator, showing the percentage of belts sent for refurbishment that are successfully reconditioned ( - Refurbishment Success Rate). It can be assumed that this rate depends on the time of belt usage and changes from 1 to 0.

To determine the unit cost of using 1 meter of refurbished belts when

is less than 1, more belts need to be sent for refurbishment because some may not be successfully refurbished. The length of belts sent for reconditioning is obtained by dividing 1 by

. Over time, as

decreases, the length of belts sent for refurbishment will increase according to the function

(equations (3) and (4)).

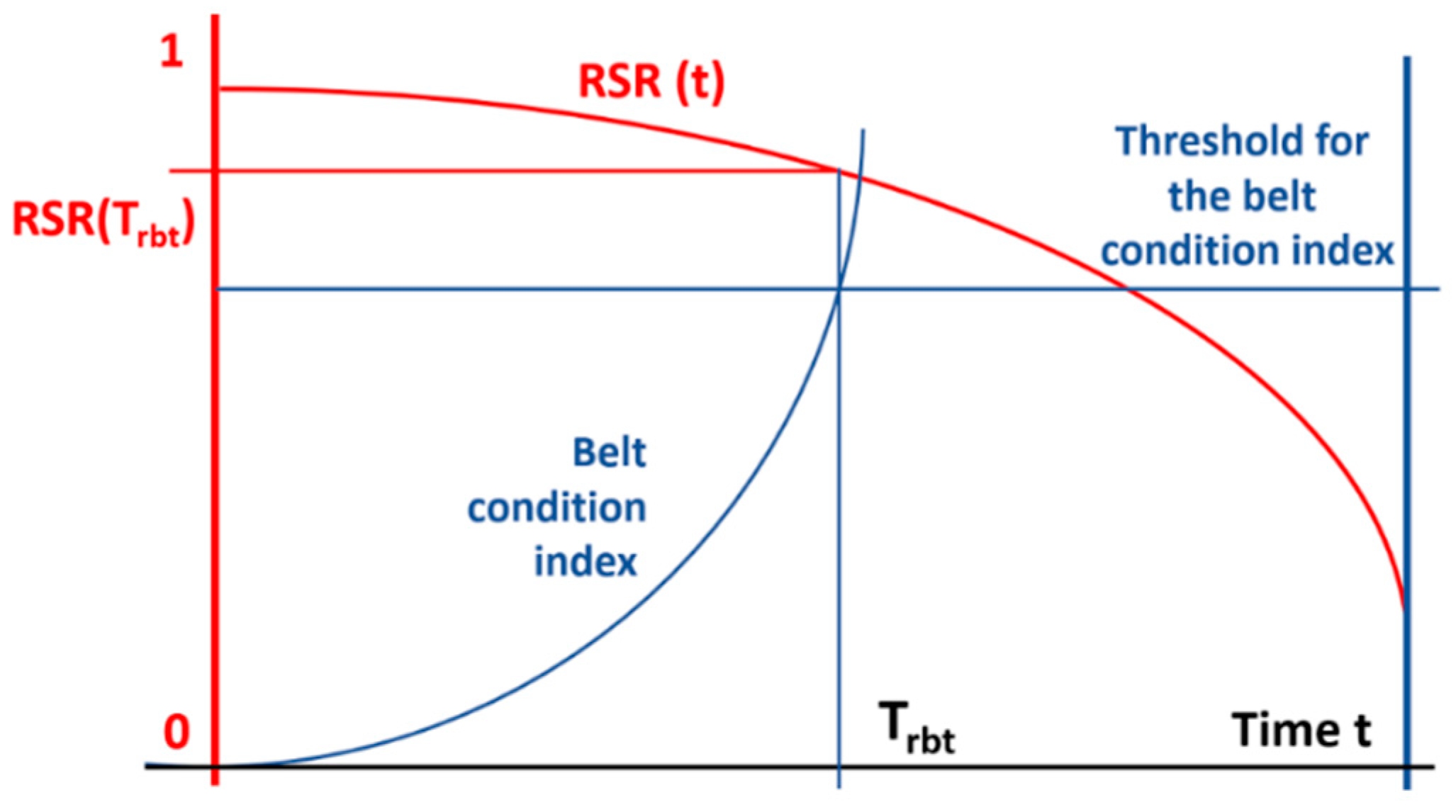

If the

indicator at the time of replacement is 0.7, and the ratio of the durability of refurbishment and new belts is, for example, 80%, the inequality will be true since 50% of

and

. Knowing the course of the

function, you can determine the critical time,

, from equations (5) and (6).

If all belts could be successfully refurbished and incorporated into production,

would be equal to 1 (at least up to

), and then (7).

If, thanks to the diagnostics of the belt's condition, it were possible to determine the belt wear index

and its changes over time, as well as the critical state

, after reaching which the belt should be dismantled and sent for refurbishment, then the replacement moment would be chosen not based on time, which is not a good measure of belt wear, but based on its condition determined by reliable and objective methods. For this time,

can be calculated and checked to see if it ensures cost-effective refurbishment (

Figure 3).

In essence, should be determined not for time but for the condition of the belt.

3. The Beginning of Conveyor Belt Refurbishment in Poland [48]

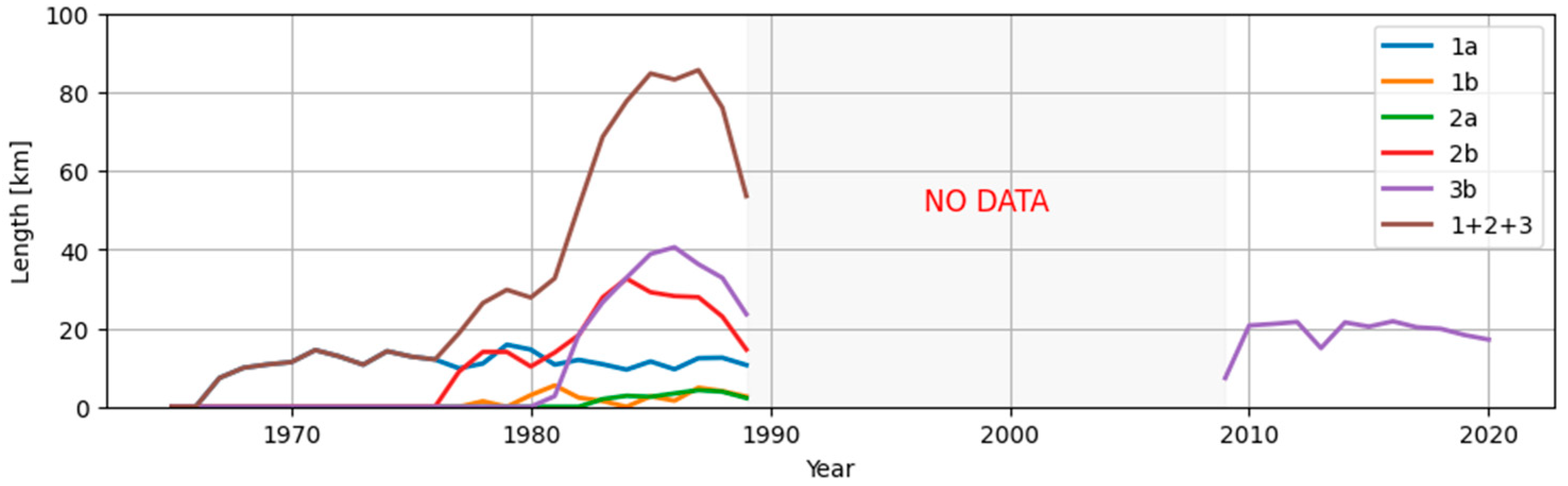

Since mid 60-ties conveyor belts have been reconditioned in lignite mines in Poland. The first reconditioning department was set up in the Turow lignite surface mine (1a, 1b,

Figure 4) The next was started up in 1977 at the Konin mine (2a, 2b,

Figure 4) and in 1981 reconditioning began at the biggest and most modern lignite mine Bełchatów (3b,

Figure 4).

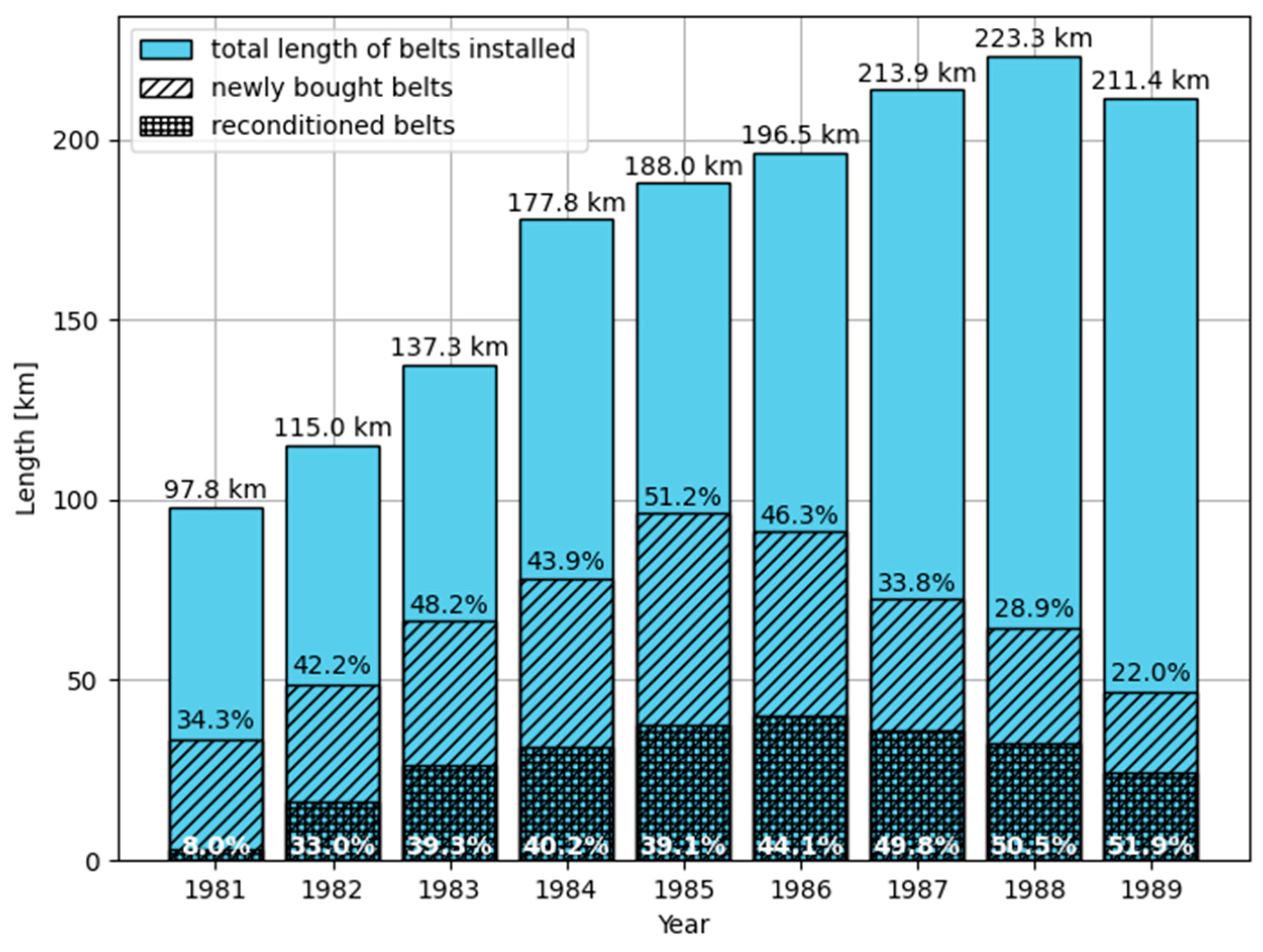

In

Figure 4 we can see that the maximal total length of reconditioned belts was close to 85 km in mid 80-ties, which gives about 14.8% of the total length (573 km) of installed belts. The lifespan of naturally worn-out belts is 49 months (4.1 years). Refurbished belts attain 85.7% of it (42,9 months=3.6 years). With the refurbishment costs lower than 50% of a new belt price. We have profitable refurbishment, due to 85.7% is greater than 50%. Even for all belts removed the durability of refurbished belts was greater than 50% (min. 54.3%; max. 62.9%). The quality of refurbished belts has increased since the mid-80-ties. One of the reasons is that this time the belt management computer system “Tasma” has been applied in the Belchatow mine which helped in rational belt management and maintenance decisions. The success rate of belt recondition can be as low as 58.34% due to 50%=87,5%

58.34%. This gives a good margin for wrong decisions about belt replacements. Data published in the paper [

48] allows for the estimation of the proportion of new and reconditioned belts to all belts supplied the mine between 1981 and 1989 is 58.65% and 41.35% respectively.

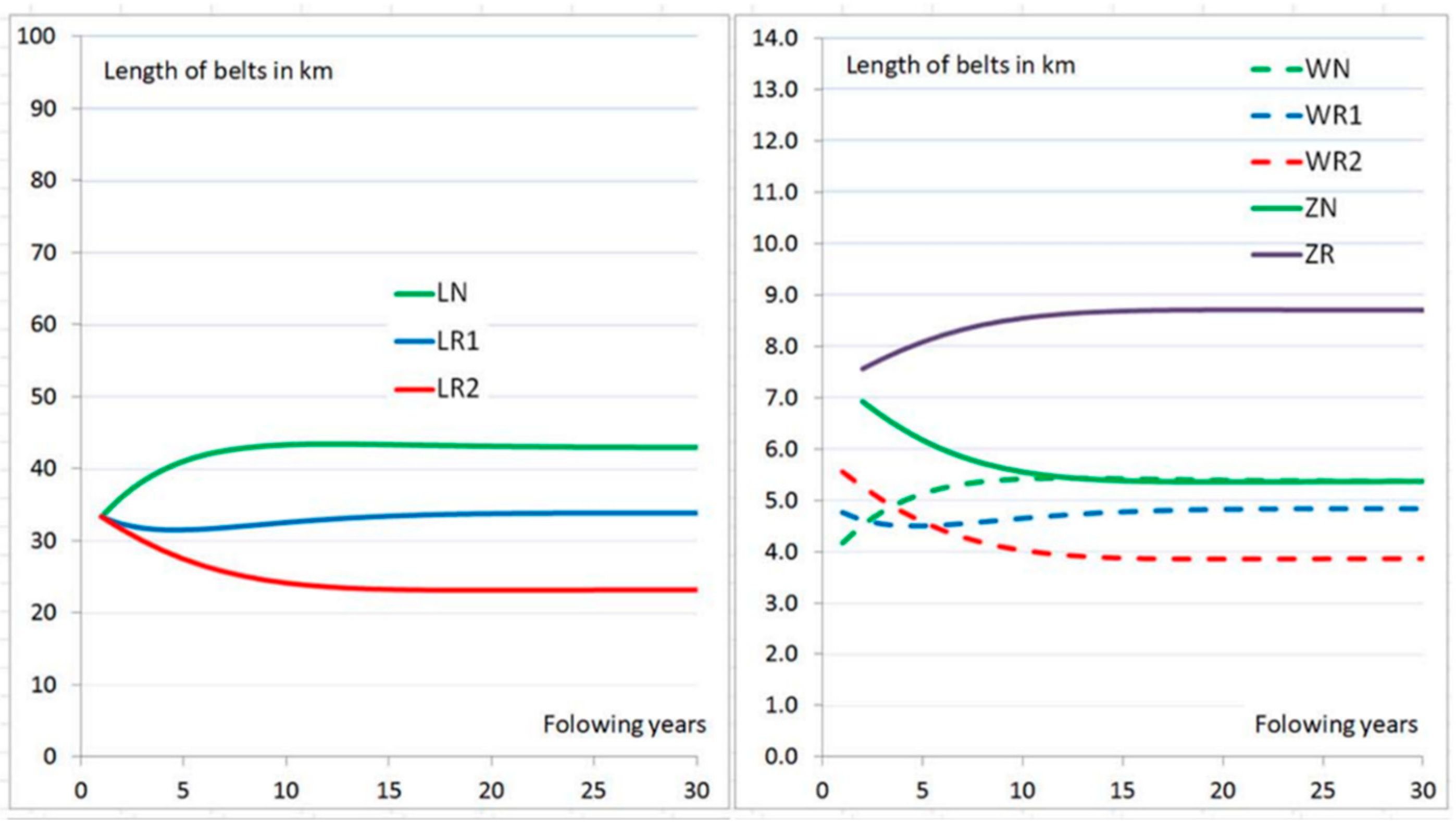

A similar proportion of new belts, belts after 1

st recondition and after the 2

nd recondition estimated for conditions of one of our lignite surface mines are a bit different. For a hypothetical mine having 100 km belts installed proportion stabilizes as is shown in the

Figure 5.

The initial state for iterative calculations of belt replacements including high refurbishment success rate

and

(in reality it is about 0.7). All types of belts new (LN), after the 1

st recondition (LR1) and after the 2

nd recondition (LR2) have the same length of 33.(3) km. After several years of belt replacements as is seen new belts had 43 km lengths and refurbished belts 57 km. Among replaced belts refurbished consisted 58.65% and new ones 41.35%. Real data in the past were the opposite. New belts supplied to the mine during 10 years consisted 58.65% and refurbished 41.35% (

Figure 6). The differences came from the fact demand for belts was not so stable due to changes in the length of conveyors' routs (mainly their increase from 50 km up to 112 km due to pit development - the length of belts is twice as much). The durability of reconditioned belts was much lower than that of new belts (slightly over 60% for the whole period and 85.7% in 1989) and unknown RSR which was much lower than the current value, especially after the application of diagnostics to select the best moment of belt dismantling for recondition.

4. The use of Diagnostics for Choosing the Optimal Moment for the Refurbishment of Belts

To accurately assess the technical condition of conveyor belts and make informed decisions regarding refurbishment at the right time, it is necessary to have information about both the condition of the belt's core and the thickness of its covers [

14]. The DiagBelt+ system, developed at the Wrocław University of Science and Technology, utilizes a magnetic method to assess the technical condition of the core with steel cords, while the BeltSonic system uses a differential measurement method to determine the thickness of the measured object. Both of these systems are installed around the moving conveyor belt, as shown in

Figure 6. The conveyor belt core diagnostic system (DiagBelt+ [

50]) requires the installation of permanent magnet strips, which are intended to magnetize the core links of the belt. It also includes a measuring head equipped with magnetic coils that record changes in the magnetic field at the location of discontinuities in the links. On the other hand, the thickness measurement system (BeltSonic [

51]) has two measuring heads installed parallel on both sides of the conveyor belt. Ultrasonic sensors installed in them measure the distance to the supporting and running covers of the belt, and knowing the distance between the sensors allows for a precise determination of the thickness of the belt at a given location.

Figure 7.

Schematic diagram of the measurement system installation on the conveyor belt. (a) DiagBelt+ system (b) BeltSonic system.

Figure 7.

Schematic diagram of the measurement system installation on the conveyor belt. (a) DiagBelt+ system (b) BeltSonic system.

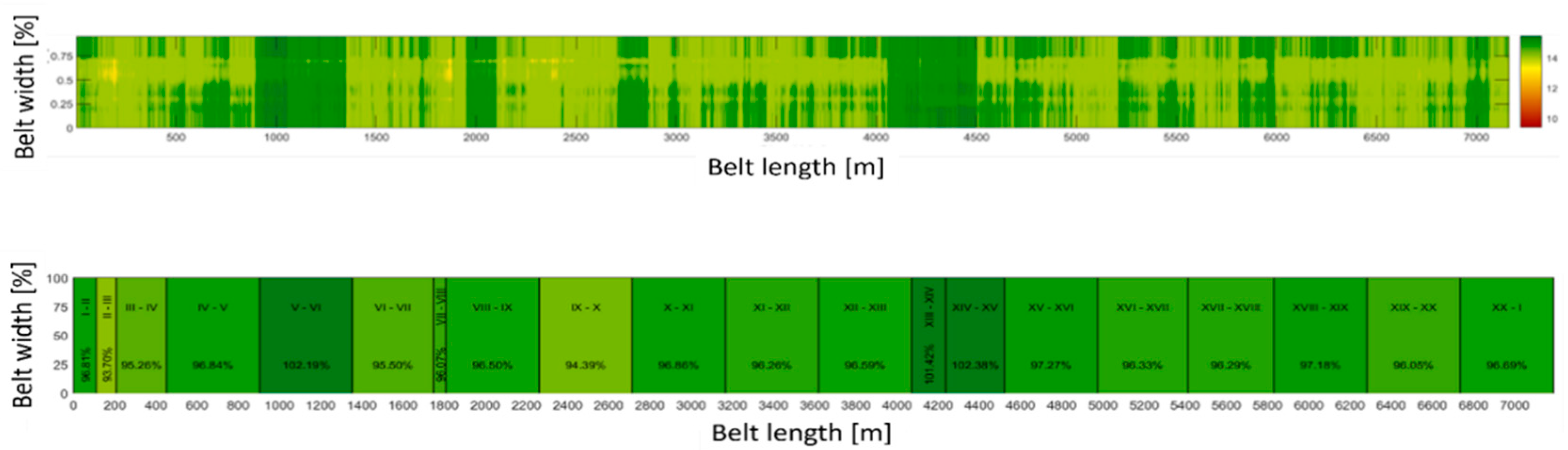

The BeltSonic system is designed for measuring the thickness and assessing changes in the transverse and longitudinal profiles of various types of conveyor belts. The operating principle of this system is based on a differential measurement. Measurement heads, placed above and below the examined object, have ultrasonic sensors that measure the distance from the sensor to the obstacle, i.e., the cover of the conveyor belt. By knowing the distance between the measurement heads and readings from both sensors (located above and below the belt), the thickness of the examined object can be determined unambiguously. The operation of the system and its design parameters have been detailed in works [

52,

53].

Measurements using the BeltSonic system enable the determination of the average and minimum thickness of the examined belt section, as well as the calculation of the percentage loss of its surface. Conducting measurements at specified time intervals allows monitoring the rate of belt wear [

34,

41]. Analyzing the results of measurements for individual sections (or shorter fragments of the conveyor belt) and comparing the measured thickness with the nominal thickness of the conveyor belt provides an image of the wear of individual sections of the examined object. An exemplary contour map of a performed measurement and a wear measure map (average percentage loss of the original cover thickness calculated for the entire surface of the section between connections) are presented in

Figure 8 for an extended loop of a belt consisting of twenty sections.

The DiagBelt+ system is designed to detect and record changes in the magnetic field that occur at the belt splice or in areas of core damage. The most common failures include corrosion of the links, cuts in the links, or their absence on a specific section of the belt (e.g., a few centimeters long). It consists of a measurement head, which is equipped with coils to read changes in the magnetic field, two strips of permanent magnets to magnetize the core, a tachometer, and a data acquisition module. A detailed description of the system's operation can be found in works [

14,

54,

55,

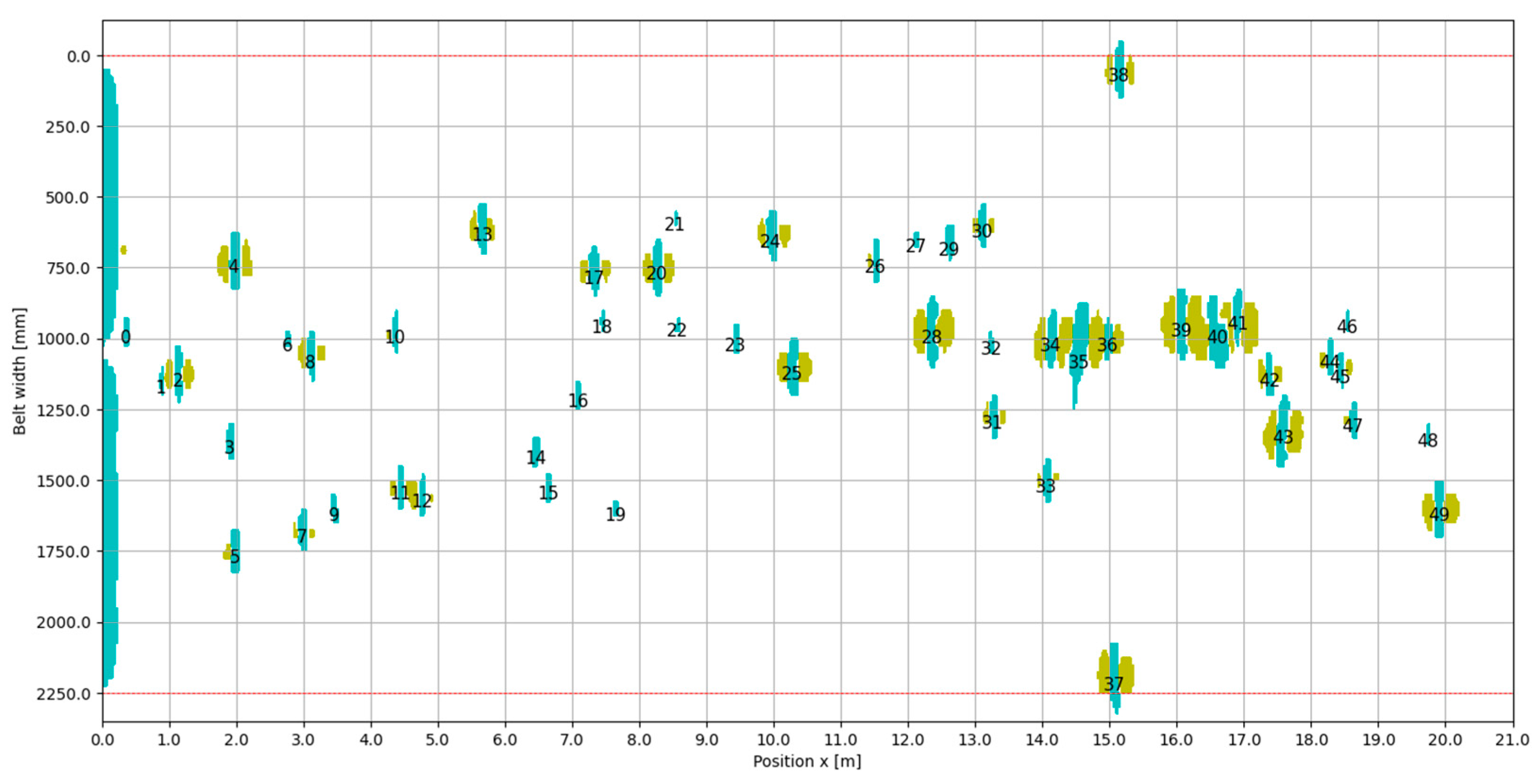

56].

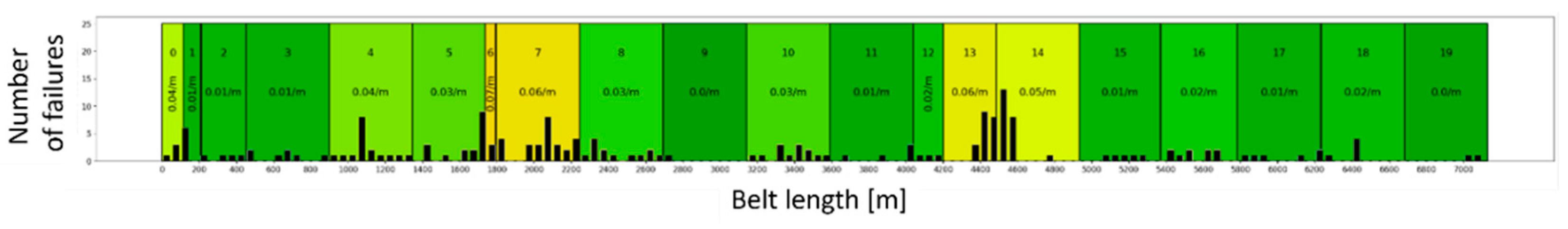

Thanks to measurements taken by the DiagBelt+ system, it is possible to obtain an image of failures, which, in turn, allows assessing the degree of damage to the belt's core and verifying the correctness of the joint's execution and its technical condition. By analyzing the number of failures, their density on a given belt section, and the characteristics of failures (their shape and belonging to specific categories), it is possible to determine which section of the belt requires repair.

Figure 9 shows signals recorded by the DiagBelt+ system, which are then used for damage analysis.

The diagnostic system also includes software that, based on measurement data, generates an assessment report of the technical condition of the examined object. This program takes into account various parameters and drawings, such as the number of failures, the quantity of splices, and the length of the belt. After analyzing the data, the system generates a map of the technical condition of the examined conveyor belt, covering all sections of the belt loop. On this map, by setting thresholds beforehand, it is possible to visually assess the condition of a particular section, as the failures represented on the map corresponds to the density of failures. An example of such a map is presented in

Figure 10.

Analysis of the distribution of registered failures on histograms, visible in the report, allows determining which part of the belt is most susceptible to failures.

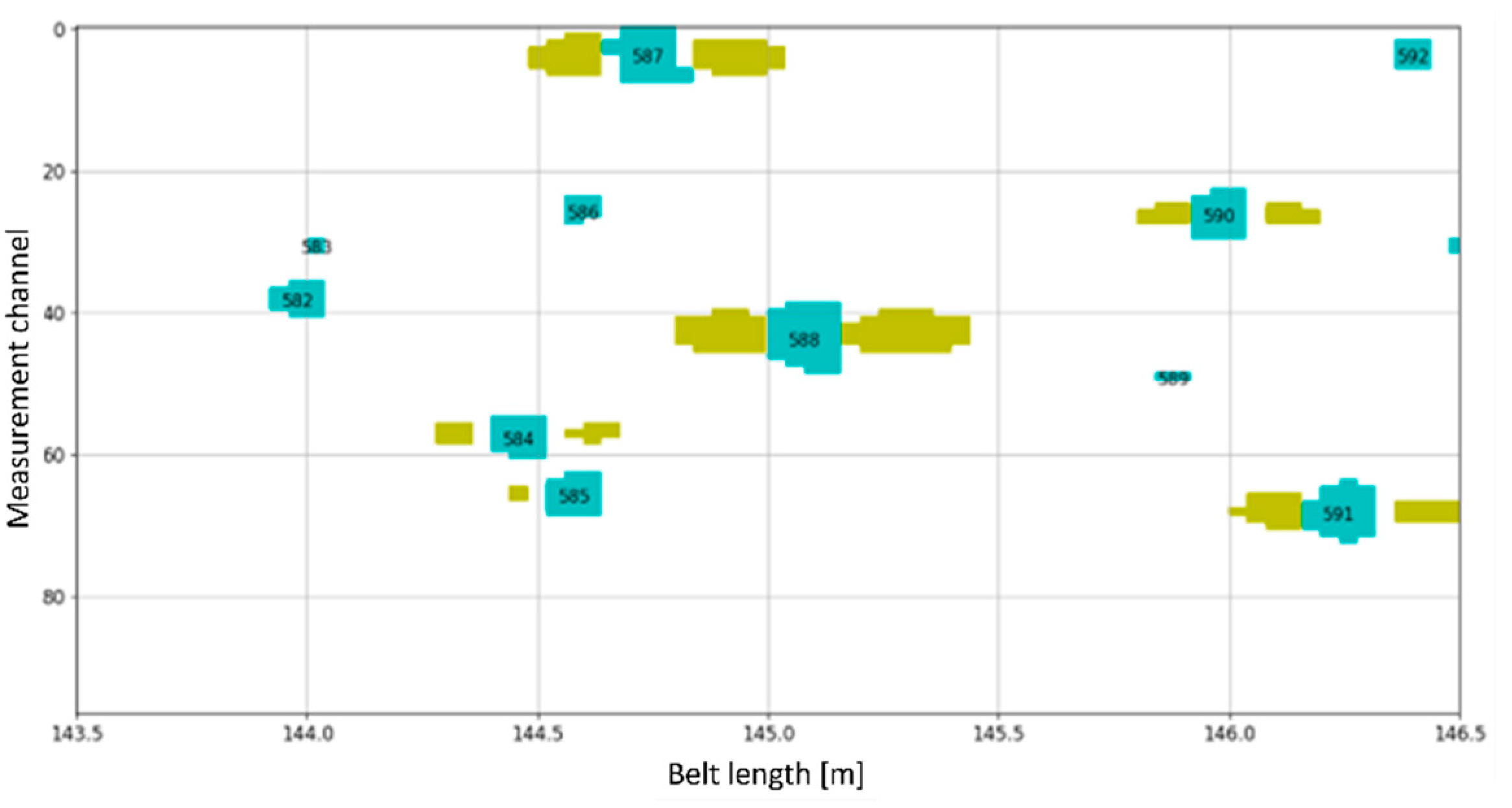

As part of the implementation of the NCBR POIR.01.01.01-00-1194/19-00 project, a series of belts operating in a brown coal mine in Poland were examined. The belts, directed for refurbishment during this project, were first scanned using the DiagBelt+ diagnostic system, and then redirected to the refurbishment process. On the refurbishment station, milling of the supporting and running cover of the belt was carried out (2 mm above the breaker). Visible failures on the belt were located in the form of a signal.

Figure 11 and

Figure 12 show a fragment of the belt where the occurrence of damage is visible on the remaining, unmilled cover, as well as in the read measurement signal. Failures in

Figure 11 are marked with numbering according to the DiagBelt+ system

Figure 12. It should be noted that not all failures visible on the remaining cover are core defects, and these were not marked or registered in the magnetic signal.

With a relatively shallow milling of the carrying cover (with preserving the breaker), only very large failures were visible on the milled surface of the belt. On the most damaged sections of both belts, they were identified. The DiagBelt+ system identified a greater number of failures, but some of them may have remained undiscovered during milling when they were not related to piercing the cover to the core with the links. This could include cracked wires and crushed links.

Figure 12 depicts the flowchart of the belt replacement strategy utilizing a diagnostic system.

Figure 12.

A flow chart of condition-based preventive belt replacement strategy for belt reconditions with the calculation of for each belt segment (BS) in a belt loop (BL) on each belt conveyor (BC) in the belt conveying system (BCS).

Figure 12.

A flow chart of condition-based preventive belt replacement strategy for belt reconditions with the calculation of for each belt segment (BS) in a belt loop (BL) on each belt conveyor (BC) in the belt conveying system (BCS).

The main difference between condition-based replacement using visual inspection and inspections with diagnostic tools is that the subjective and incomplete (based on the external view) assessment of the belt condition is replaced by the reliable assessment of the belt core condition by the magnetic system. Calendar time (the degree of filling the belt service life), which is sensitive to many factors, including a change in the conveyor load, is replaced by an objective measure of the belt condition (e.g. the density of damage per 1 meter of belt segment). After crossing the threshold by measured the belt segment will be sent to the refurbishment plant. The threshold (), identical to all conveyors (regardless of their operating condition, length, belt speed, load etc.), will be optimally selected taking into account the changes in the recondition success rate (), costs of refurbishment and belt segment durability after recondition. is not known a priori but can be calculated a posteriori after sending several belt segments to refurbishment with known and attained during refurbishment.

For 50 years, a preventive belt replacement strategy to refurbishment was used in the Bełchatów mine based on the belt condition. The belt condition was determined during the visual inspection taking into account their age in comparison to selected service life for a given conveyors (expected time of their operation) working in specific conditions. The use of a subjective visual assessment and operating time, which is a very inaccurate measure of belt condition, led to frequent recondition failures. The belts were pulled of the conveyors too late, because although the belt did not look worn from the outside, but the core condition was poor. Numerous cables and corrosion intersections, invisible from the outside, prevented reconditioning from success. The indicator was about 70%. The solution was to implement the magnetic diagnostics of the core condition using the Diagbelt+ system. Determining the core condition became possible on the conveyor, which not only reduced the costs, but above all enabled an objective assessment of the invisible core and better determination of the moment of dismantling. Currently, the mine is in the phase of intensive scanning of belts directed for refurbishment so that it will be possible optimal selection of to minimize the costs of using belts in the mine. Savings generated by avoiding too early dismantling of belts turned out to be a big positive surprise. Many belts working on less loaded conveyors have a little used belt core, although they have long filled the temporary Resurs. They would normally be directed to refurbishment and it would probably be successful. However, greater savings give it further use for the next months and years, because the belt loop can work, and the costs of refurbishment are not incurred. The success of refurbishment depends more on the core condition and less on the condition of the covers and the edges. The use of magnetic diagnostics NDT core condition makes this task easier. This will increase even to a level of 90%, extend the time of use of belts, reduce purchases of new ones, which will affect. The cost of reconditioning at Bestgum plants is estimated at 50% of the purchase price of new belt. Leading belt manufacturers estimate at 60-65% of purchase costs.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

The work aims to demonstrate the profitability of preventive replacements for belt regeneration. Lignite mines in Poland have successfully employed this strategy for over 50 years. The current market size exceeds $4 billion and is growing at a rate of 3 to almost 6%. Various estimates indicate that the production and delivery of belts consume significant resources, with approximately 75% of production costs attributed to raw materials. The remaining costs include energy, which is subject to price increases, and labor. Belt production is automated, potentially leading to plant relocations outside Europe due to rising energy prices and weaker environmental regulations.

Many cheaper components are not approved for use in Europe but can be used outside the EU. The pandemic has highlighted extended supply chain timelines and geographical reach (due to carbon leakage), increasing the risk of deadline and quality failures and leading to price hikes, sometimes doubling. Refurbishment has once again become an attractive method to meet growing demand and enhance the security of supply and transport system continuity.

In Poland, belts are refurbished on-site, a practice that originated due to the lack of foreign exchange for imports and continues today due to extended delivery times and related uncertainties. Heavy-weight belts, being the most expensive, undergo refurbishment to maximize their utility. It is considered environmentally wasteful to discard them after a single use. Therefore, in Poland, heavy-weight belts are reconditioned, often twice (with the core being used three times), and in the past, even three times. Textile belts were also reconditioned in the past [

57], a practice now rare due to the lower price of belts and the less valuable and durable core. Water ingress into the core causes delamination of the interlayers, excluding the belt from refurbishment.

Correct refurbishment is possible when the core is not excessively damaged. The use of core diagnostics and assessment of its condition on conveyors significantly reduces errors in decision-making during refurbishment. With the implementation of diagnostics using the DiagBelt+ system and the ability to test belt abrasion with the BeltSonic system, the probability of errors decreases, leading to an improved refurbishment success rate () and increased economic efficiency in the reconditioning process.

In the 1980s, the proportions of new and remanufactured belts on conveyors were 60% new and 40% remanufactured. Current simulations suggest a reversal of these proportions, with 60% remanufactured and 40% new. The Bełchatów mine, following the closure of one of its workings, practically abandoned the purchase of new belts. Instead, it effectively assesses the condition of dismantled belts and makes informed decisions on whether to reuse, refurbish, or discard them. To ensure the environmental effectiveness of the full belt use cycle, efforts are made to resell used belts, use them for other purposes (reuse), or recycle them to recover all components [

58,

59]. The refurbishment plant already recovers milled rubber from the reconditioning process to produce mats, carpets, and paving stones for parking lots. As used belts become more available, recycling rates will likely need to increase. Rubber from conveyor belts can be recycled in a similar way to rubber from tires [

60].

The use of both measurement systems, DiagBelt+ for assessing the technical condition of the core and BeltSonic for evaluating the cover thickness, provides a comprehensive understanding of the technical state of the examined conveyor belt. This approach allows for the continuous monitoring of changes in its condition over time through periodic measurements. This enables the implementation of predictive belt replacement, based on the diagnosed condition, following any preventive replacement strategy [

61]. This strategy allows choosing for refurbishment only those belts that actually show a significant number of failures but still qualify for refurbishment. Utilizing the refurbishment capabilities of dismantled belt fragments that have reached a level of wear qualifying them for refurbishment increases the working time of full sections, minimizing the risk of emergency replacement and production losses associated with downtime and waiting for the delivery of new belts.

Traditional methods of assessing the condition of belts, such as visual inspection combined with the calendar age of the belt's operation, proved to be ineffective from the mine's perspective. As a result of the project implementation and the use of the system, the mine reports significant benefits, avoiding the need to send belts for refurbishment that, despite exceeding the calendar age of operation, still maintain a good technical condition.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.J. and R.B.; methodology, L.J.; software, L.J and A.R..; validation, R.B.; formal analysis, L.J. and A.R.; investigation, R.B.; resources, R.B.; data curation, R.B. and A.R.; writing—original draft preparation, L.J. and A.R.; writing—review and editing, L.J. and R.B. and A.R.; visualization, L.J. and A.R.; supervision, R.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

We encourage all authors of articles published in MDPI journals to share their research data. In this section, please provide details regarding where data supporting reported results can be found, including links to publicly archived datasets analyzed or generated during the study. Where no new data were created, or where data is unavailable due to privacy or ethical restrictions, a statement is still required. Suggested Data Availability Statements are available in section “MDPI Research Data Policies” at

https://www.mdpi.com/ethics.

Acknowledgments

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Kawalec W (2009) Przenośniki taśmowe dalekiego zasięgu do transportu węgla brunatnego. Transport Przemysłowy i Maszyny Robocze 1:6–13.

- Bogacz P, Cieślik Ł, Osowski D, Kochaj P (2022) Analysis of the Scope for Reducing the Level of Energy Consumption of Crew Transport in an Underground Mining Plant Using a Conveyor Belt System Mining Plant. Energies (Basel) 15:7691. [CrossRef]

- Mathaba T, Xia X (2017) Optimal and energy efficient operation of conveyor belt systems with downhill conveyors. Energy Effic 10:405–417. [CrossRef]

- Krol R, Kawalec W, Gladysiewicz L (2017) An Effective Belt Conveyor for Underground Ore Transportation Systems. IOP Conf Ser Earth Environ Sci 95:042047. [CrossRef]

- Vijay A, Mathew M, Rohith PK (2017) Development of an economical digital control method for a continuously running conveyor belt. In: 2017 International Conference on Inventive Systems and Control (ICISC). IEEE, pp 1–5.

- Luo J, Huang W, Zhang S (2015) Energy cost optimal operation of belt conveyors using model predictive control methodology. J Clean Prod 105:. [CrossRef]

- Zhang S, Tang Y (2011) Optimal scheduling of belt conveyor systems for energy efficiency — With application in a coal-fired power plant. In: 2011 Chinese Control and Decision Conference (CCDC). IEEE, pp 1434–1439.

- Oliveira Neto R, Gastineau P, Cazacliu BG, et al (2017) An economic analysis of the processing technologies in CDW recycling platforms. Waste Management 60:277–289. [CrossRef]

- Salawu G, Glen B (2023) Improving the Efficiency of a Conveyor System in an Automated Manufacturing Environment Using a Model-Based Approach. International Journal of Mechanical Engineering and Robotics Research 107–112. [CrossRef]

- Rashid S, Bashir O, Majid I (2023) Different mechanical conveyors in food processing. In: Transporting Operations of Food Materials Within Food Factories. Elsevier, pp 253–263.

- Martin H (2018) Warehousing and Transportation Logistics: Systems, Planning, Application and Cost Effectiveness. Kogan Page Publishers, 2018, London.

- Draganová K, Semrád K, Spodniak M, Cúttová M (2020) Innovative analysis of the physical-mechanical properties of airport conveyor belts. Transportation Research Procedia 51:20–27. [CrossRef]

-

Jurdziak L (2017) Economic analysis of steel cord conveyor belts replacement strategy in order to undertake profitable refurbishment of worn out belts.

- Błażej R, Jurdziak L, Kirjanów-Błażej A, et al (2022) Profitability of conveyor belt refurbishment and diagnostics in the light of the circular economy and the full and effective use of resources. Energies (Basel) 15:. [CrossRef]

- Bajda M, Hardygóra M (2021) Analysis of the influence of the type of belt on the energy consumption of transport processes in a belt conveyor. Energies (Basel) 14:. [CrossRef]

- Bajda M, Hardygóra M (2022) Examination and assessment of the impact of working conditions on operating parameters of selected conveyor belts. Mining Science 29:165–178.

- Youssef G (2016) Development of Conveyor Belts Design for Reducing Energy Consumption in Mining Application. Master thesis, Ain Shams University.

- Kawalec W, Król R (2019) Sustainable Development Oriented Belt Conveyors Quality Standards. pp 327–336.

- Opasiak T, Marglewicz J, Gąska D, Haniszewski T (2022) Rollers for belt conveyors in terms of rotation resistance and energy efficiency. Transport Problems 17:57–68. [CrossRef]

- Masaki MS, Zhang L, Xia X (2018) A design approach for multiple drive belt conveyors minimizing life cycle costs. J Clean Prod 201:526–541. [CrossRef]

- Zhang M, Jiang K, Cao Y, et al (2022) A deep learning-based method for deviation status detection in intelligent conveyor belt system. J Clean Prod 363:132575. [CrossRef]

- Luo J, Huang W, Zhang S (2015) Energy cost optimal operation of belt conveyors using model predictive control methodology. J Clean Prod 105:196–205. [CrossRef]

- Subba Rao DV (2020) The Belt Conveyor. CRC Press.

- Dick JS (2023) Testing Rubber Products for Performance: An Overview of Commercial Rubber Product Performance Requirements for the Non-product Specialists. ASTM International, West Conshohocken.

- Ambriško Ľ, Marasová D (2020) Experimental Research of Rubber Composites Subjected to Impact Loading. Applied Sciences 10:8384. [CrossRef]

- Andrejiova M, Grincova A, Marasova D (2020) Analysis of tensile properties of worn fabric conveyor belts with renovated cover and with the different carcass type. Eksploatacja i Niezawodnosc 22:. [CrossRef]

- Bajda M, Błażej R, Jurdziak L (2017) Partial replacements of conbeyor belt loop analysis with regard to its reliability. In: 17th International Multidisciplinary Scientific GeoConference, SGEM 2017. Sofia.

- David L (2024) The Competitive Conveyor Belt Market. In: https://www.agg-net.com/resources/articles/materials-handling/the-competitive-conveyor-belt-market.

- Bajda M, Hardygóra M (2019) Laboratory tests of operational durability and energy-efficiency of conveyor belts. E: In: IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science.

- Ambriško Ľ, Marasová D, Grendel P, Lukáč S (2015) Application of logistics principles when designing the process of transportation of raw materials. Acta Montanistica Slovaca 20:141–147.

- Knežo D, Andrejiová M, Kimáková Z, Radchenko S (2016) Determining of the Optimal Device Lifetime using Mathematical Renewal Models. TEM Journal 5:.

- Grinčová A, Andrejiová M, Grendel P (2014) Application the Renewal Theory to Determining the Models of the Optimal Lifetime for Conveyor Belts. Applied Mechanics and Materials 683:97–101. [CrossRef]

- Parmar P, Burduk A, Jurdziak L (2024) Ishikawa Diagram Indicating Potential Causes for Damage Occurring to the Rubber Conveyor Belt Operating at Coal Mining Site. pp 704–713.

- Webb C, Sikorska J, Khan RN, Hodkiewicz M (2020) Developing and evaluating predictive conveyor belt wear models. Data-Centric Engineering 1:. [CrossRef]

- Fedorko G, Molnár V, Živčák J, et al (2013) Failure analysis of textile rubber conveyor belt damaged by dynamic wear. Eng Fail Anal 28:. [CrossRef]

- Fedorko G, Molnár V, Ferková Ž, et al (2016) Possibilities of failure analysis for steel cord conveyor belts using knowledge obtained from non-destructive testing of steel ropes. Eng Fail Anal 67:. [CrossRef]

- Bortnowski P, Kawalec W, Król R, Ozdoba M (2022) Types and causes of damage to the conveyor belt – Review, classification and mutual relations. Eng Fail Anal 140.

- Ilanković N, Živanić D, Zuber N (2023) The Influence of Fatigue Loading on the Durability of the Conveyor Belt. Applied Sciences 13:3277. [CrossRef]

- Sikorska JZ (2021) Variable Selection for Conveyor-Belt Mean Wear Rate Prediction. Insights in Mining Science & Technology 02. [CrossRef]

- Temerzhanov A, Stolpovskikh I, Sładkowski A (2012) Analysis of reliability parameters of conveyor belt joints. Transport Problems 7:.

- Webb C, Hodkiewicz M, Khan N, et al (2013) Conveyor Belt Wear Life Modelling. CEED Seminar Proceedings 2013.

- Al-Attar RT, AL-Khafaji MS, AL-Ani FH (2021) Fuzzy - Based Multi - Criteria Decision Support System for Maintenance Management of Wastewater Treatment Plants. Civil and Environmental Engineering 17:654–672. [CrossRef]

- Patyk M, Bodziony P, Krysa Z (2021) A Multiple Criteria Decision Making Method to Weight the Sustainability Criteria of Equipment Selection for Surface Mining. Energies (Basel) 14:3066. [CrossRef]

- Roumpos C, Partsinevelos P, Agioutantis Z, et al (2014) The optimal location of the distribution point of the belt conveyor system in continuous surface mining operations. Simul Model Pract Theory 47:19–27. [CrossRef]

- Bajda M, Błażej R, Jurdziak L (2019) Analysis of changes in the length of belt sections and the number of splices in the belt loops on conveyors in an underground mine. Eng Fail Anal 101:. [CrossRef]

- Jurdziak L, Kawalec W (1990) System informatyczny wspomagający gospodarkę taśmami przenośnikowymi w KWB Turów. Górnictwo Odkrywkowe 32:69–76.

- (2024) Contitech. In: https://www.continental-industry.com/en/solutions/conveyor-beltsystems/conveyor-services/digital-solutions/conveyor-data-software.

- Jurdziak L, Kawalec W (1990) Komputerowo wspomagana gospodarka taśmami w KWB Turów. Górnictwo Odkrywkowe 3–4.

- Blazej R, Jurdziak L (2017) Condition-Based Conveyor Belt Replacement Strategy in Lignite Mines with Random Belt Deterioration. IOP Conf Ser Earth Environ Sci 95:042051. [CrossRef]

- (2024) https://diagbeltplus.pwr.edu.pl/.

- (2024) https://beltsonic.pwr.edu.pl/.

- Kirjanów-Błażej A, Jurdziak L, Błażej R, Rzeszowska A (2023) Calibration procedure for ultrasonic sensors for precise thickness measurement. Measurement 214:112744. [CrossRef]

- Kirjanów-Błażej A, Błażej R, Jurdziak L, et al (2022) Innovative diagnostic device for thickness measurement of conveyor belts in horizontal transport. Sci Rep 12:. [CrossRef]

- Blazej R, Jurdziak L, Kirjanow-Blazej A, Kozlowski T (2021) Identification of damage development in the core of steel cord belts with the diagnostic system. Sci Rep 11:. [CrossRef]

- Jurdziak L, Błażej R, Kirjanów-Błażej A, et al (2024) Improving the effectiveness of the DiagBelt+ diagnostic system - analysis of the impact of measurement parameters on the quality of signals. Eksploatacja i Niezawodność – Maintenance and Reliability. [CrossRef]

- Jurdziak L, Błażej R, Kirjanów-Błażej A, Rzeszowska A (2023) Transverse Profiles of Belt Core Damage in the Analysis of the Correct Loading and Operation of Conveyors. Minerals 13:1520. [CrossRef]

- Ruuth E, Sanchis-Sebastiá M, Larsson PT, et al (2022) Reclaiming the Value of Cotton Waste Textiles: A New Improved Method to Recycle Cotton Waste Textiles via Acid Hydrolysis. Recycling 7:57. [CrossRef]

- Idriss LK, Gamal YAS (2022) Properties of Rubberized Concrete Prepared from Different Cement Types. Recycling 7:39. [CrossRef]

- Abdulrahman AS, Jabrail FH (2022) Treatment of Scrap Tire for Rubber and Carbon Black Recovery. Recycling 7:27. [CrossRef]

- Li J, Xiao X, Chen Z, et al (2022) Internal de-crosslinking of scrap tire crumb rubber to improve compatibility of rubberized asphalt. Sustainable Materials and Technologies 32:e00417. [CrossRef]

- Kirjanów-Błażej A, Jurdziak L, Burduk R, Błażej R (2019) Forecast of the remaining lifetime of steel cord conveyor belts based on regression methods in damage analysis identified by subsequent DiagBelt scans. Eng Fail Anal 100:. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).