Submitted:

02 January 2026

Posted:

04 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Background and Significance

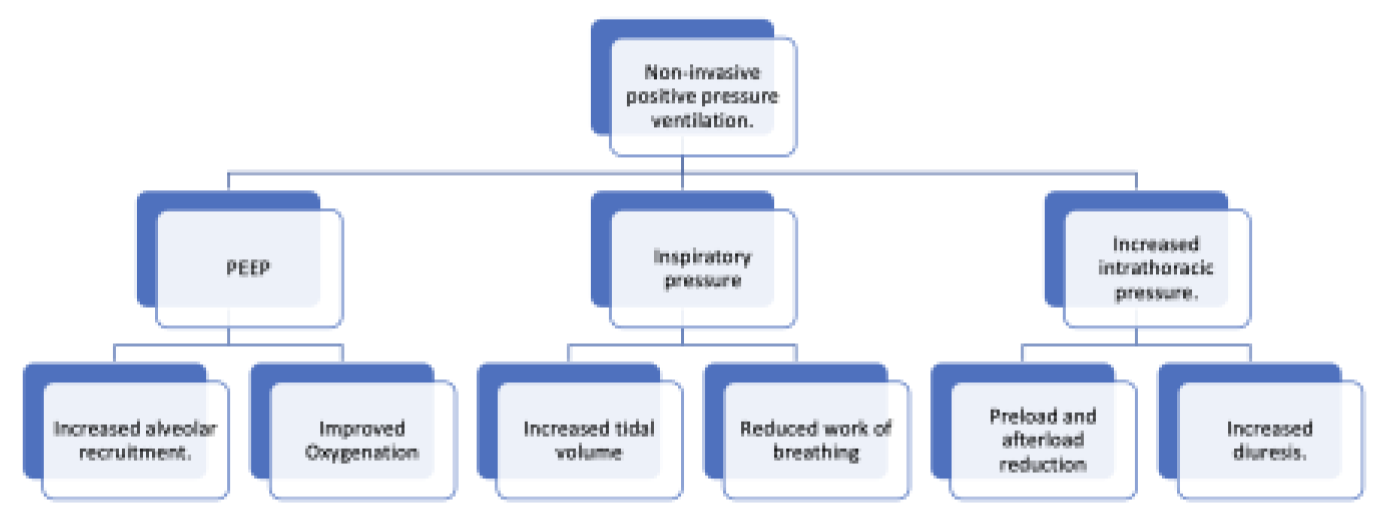

2. Mechanical Effects of NIPPV on Respiration

3. Disorders Commonly Managed with Noninvasive Ventilation

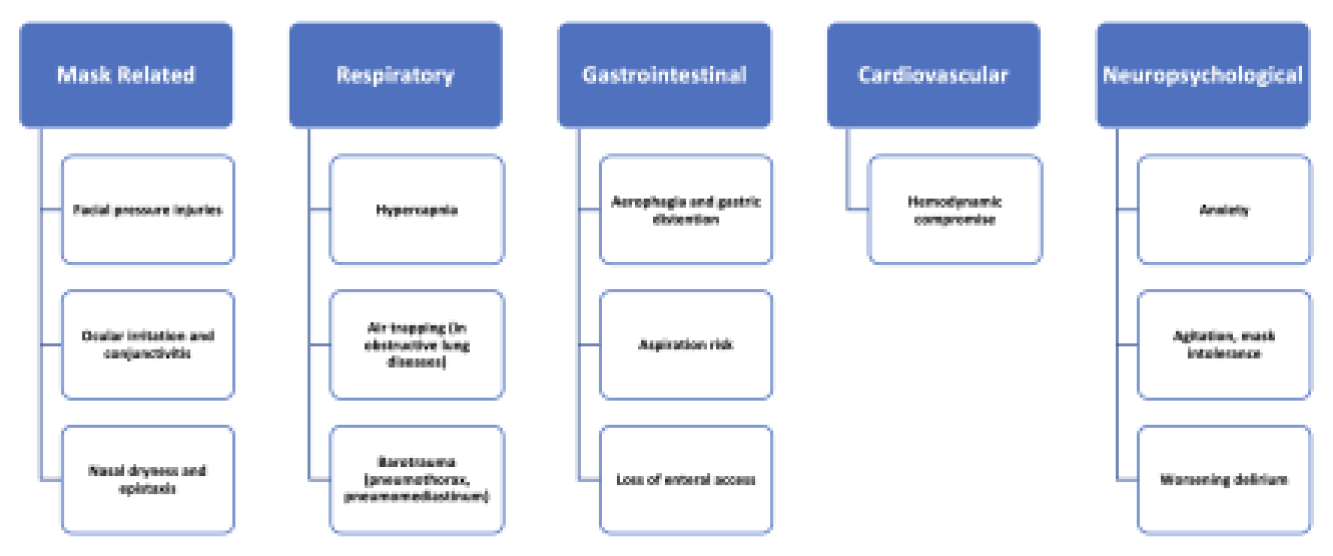

4. Complications from Prolonged NIPPV Support

5. Challenging Clinical Situations Encountered During Liberation from NIPPV

- i.

- Morbid obesity

- ii.

- Delirium and dementia

- iii.

- Advanced COPD

- iv.

- Neuromuscular disorders

- v.

- Pulmonary hypertension

6. Approach to Liberation in Complex Patients

- i.

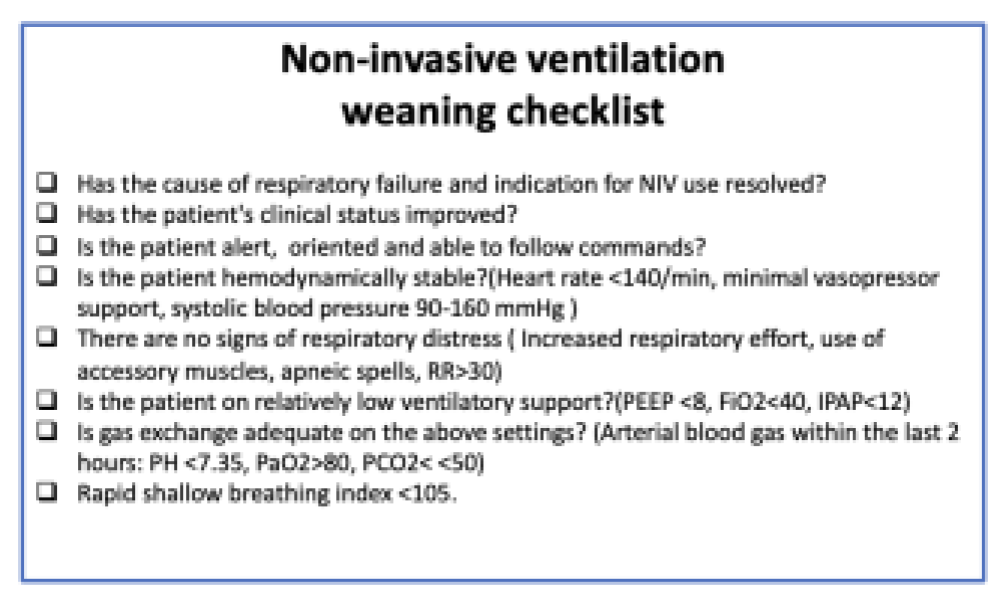

- Assessing readiness to wean from noninvasive ventilatory support

- In patients with chronic hypercapnia PaCO2>50 is acceptable if PH remains in the normal range (7.35-7.45).

- In patients with neuromuscular disease the RSBI may not be particularly helpful. In these patients the diaphragm thickening fraction (DTF) can be used as an additional tool to predict successful weaning of NIV. DTF is an ultrasound-based measurement of diaphragmatic strength. Diaphragm thickness is sonographically measured at end-expiration and end inspiration. The percentage change in diaphragmatic thickness (DTF) accurately predicts weaning success [66].

- In patients with pulmonary hypertension requiring inhaled vasodilator therapy in the ICU, any ventilator weaning strategy must incorporate assessment of continued need for vasodilator therapy. Weaning from NIV must proceed concomitantly with a transition to an oral/ intravenous domiciliary regimen.

- Agitation and delirium are independent risk factors for failure to wean from NIV. Agitated patients may need initiation and continuation of antipsychotic (Seroquel, haloperidol) or sedative(dexmedetomidine) medications.

- ii.

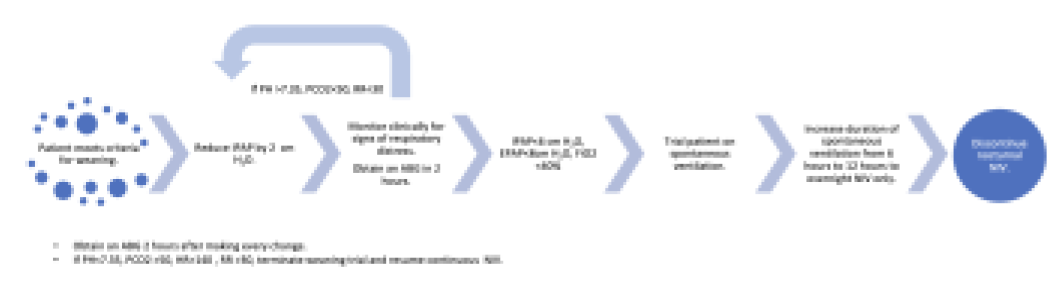

- Weaning strategies:

7. Summary

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| NIV | Non-invasive ventilation |

| PEEP | Positive end expiratory pressure |

| IMV | Invasive mechanical ventilation |

| BiPAP | Bilevel positive airway pressure |

| CPAP | Continuous positive airway pressure |

| COPD | Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease |

| CHF | Congestive heart failure |

| COVID-19 | Coronavirus Disease 2019 |

| ICU | Intensive care unit |

| NIPPV | Non-invasive positive pressure ventilation |

| EPAP | End expiratory positive airway pressure |

| IPAP | Inspiratory positive airway pressure |

| RSBI | Rapid shallow breathing index |

| PH | Pulmonary hypertension |

| PAH | Pulmonary arterial hypertension |

| SCAPE | Sympathetic crashing acute pulmonary edema |

| AHA | American Heart Association |

| DTF | Diaphragm thickening fraction |

References

- Zimnoch M, Eldeiry D, Aruleba O, Schwartz J, Avaricio M, Ishikawa O, Mina B, Esquinas A. Non-Invasive Ventilation: When, Where, How to Start, and How to Stop. J Clin Med. 2025 Jul 16;14(14):5033. PMID: 40725723; PMCID: PMC12295356. [CrossRef]

- Salvador Díaz Lobato, Sagrario Mayoralas Alises,Modern Non-Invasive Mechanical Ventilation Turns 25,Archivos de Bronconeumología (English Edition),Volume 49, Issue 11,2013,Pages 475-479,ISSN 1579-2129. [CrossRef]

- Slutsky AS. History of Mechanical Ventilation. From Vesalius to Ventilator-induced Lung Injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015 May 15;191(10):1106-15. PMID: 25844759. [CrossRef]

- Lobato, Salvador Díaz, and Sagrario Mayoralas Alises. “Modern non-invasive mechanical ventilation turns 25.” Archivos de Bronconeumología (English Edition) 49, no. 11 (2013): 475-479.

- Brochard L, Mancebo J, Wysocki M, Lofaso F, Conti G, Rauss A, Simonneau G, Benito S, Gasparetto A, Lemaire F, et al. Noninvasive ventilation for acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 1995 Sep 28;333(13):817-22. PMID: 7651472. [CrossRef]

- Plant PK, et al. Early use of non-invasive ventilation for acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease on general respiratory wards: a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2000;355(9219):1931–1935.

- Masip J, Betbesé AJ, Paez J, et al. Non-invasive pressure support ventilation versus conventional oxygen therapy in acute cardiogenic pulmonary oedema: a randomized trial. Chest. 2000;117(4):1085–1090.

- Ozsancak Ugurlu A, Sidhom SS, Khodabandeh A, Ieong M, Mohr C, Lin DY, Buchwald I, Bahhady I, Wengryn J, Maheshwari V, Hill NS. Use and outcomes of noninvasive positive pressure ventilation in acute care hospitals in Massachusetts. Chest. 2014 May;145(5):964-971. PMID: 24480997. [CrossRef]

- Ozsancak Ugurlu A, Sidhom SS, Khodabandeh A, Ieong M, Mohr C, Lin DY, Buchwald I, Bahhady I, Wengryn J, Maheshwari V, Hill NS. Where is Noninvasive Ventilation Actually Delivered for Acute Respiratory Failure? Lung. 2015 Oct;193(5):779-88. Epub 2015 Jul 26. PMID: 26210474. [CrossRef]

- Schnell D, Timsit JF, Darmon M, Vesin A, Goldgran-Toledano D, Dumenil AS, Garrouste-Orgeas M, Adrie C, Bouadma L, Planquette B, Cohen Y, Schwebel C, Soufir L, Jamali S, Souweine B, Azoulay E. Noninvasive mechanical ventilation in acute respiratory failure: trends in use and outcomes. Intensive Care Med. 2014 Apr;40(4):582-91. Epub 2014 Feb 7. PMID: 24504643. [CrossRef]

- Munshi L, Mancebo J, Brochard LJ. Noninvasive Respiratory Support for Adults with Acute Respiratory Failure. N Engl J Med. 2022 Nov 3;387(18):1688-1698. PMID: 36322846. [CrossRef]

- Rochwerg B, Brochard L, Elliott MW, Hess D, Hill NS, Nava S, Navalesi P Members Of The Steering Committee, Antonelli M, Brozek J, Conti G, Ferrer M, Guntupalli K, Jaber S, Keenan S, Mancebo J, Mehta S, Raoof S Members Of The Task Force. Official ERS/ATS clinical practice guidelines: noninvasive ventilation for acute respiratory failure. Eur Respir J. 2017 Aug 31;50(2):1602426. PMID: 28860265. [CrossRef]

- Thille AW, Muller G, Gacouin A, Coudroy R, Decavèle M, Sonneville R, Beloncle F, Girault C, Dangers L, Lautrette A, Cabasson S, Rouzé A, Vivier E, Le Meur A, Ricard JD, Razazi K, Barberet G, Lebert C, Ehrmann S, Sabatier C, Bourenne J, Pradel G, Bailly P, Terzi N, Dellamonica J, Lacave G, Danin PÉ, Nanadoumgar H, Gibelin A, Zanre L, Deye N, Demoule A, Maamar A, Nay MA, Robert R, Ragot S, Frat JP; HIGH-WEAN Study Group and the REVA Research Network. Effect of Postextubation High-Flow Nasal Oxygen With Noninvasive Ventilation vs High-Flow Nasal Oxygen Alone on Reintubation Among Patients at High Risk of Extubation Failure: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2019 Oct 15;322(15):1465-1475. Erratum in: JAMA. 2020 Feb 25;323(8):793. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.0373. PMID: 31577036; PMCID: PMC6802261. [CrossRef]

- Burns KEA, Stevenson J, Laird M, et al. Non-invasive ventilation versus invasive weaning in critically ill adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Thorax 2022;77:752-761.

- Jaber S, Pensier J, Futier E, Paugam-Burtz C, Seguin P, Ferrandiere M, Lasocki S, Pottecher J, Abback PS, Riu B, Belafia F, Constantin JM, Verzilli D, Chanques G, De Jong A, Molinari N; NIVAS Study Group. Noninvasive ventilation on reintubation in patients with obesity and hypoxemic respiratory failure following abdominal surgery: a post hoc analysis of a randomized clinical trial. Intensive Care Med. 2024 Aug;50(8):1265-1274. Epub 2024 Jul 29. PMID: 39073580. [CrossRef]

- Jaber S, Lescot T, Futier E, et al. Effect of Noninvasive Ventilation on Tracheal Reintubation Among Patients With Hypoxemic Respiratory Failure Following Abdominal Surgery: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2016;315(13):1345–1353. [CrossRef]

- Pettenuzzo T, Boscolo A, Pistollato E, Pretto C, Giacon TA, Frasson S, Carbotti FM, Medici F, Pettenon G, Carofiglio G, Nardelli M, Cucci N, Tuccio CL, Gagliardi V, Schiavolin C, Simoni C, Congedi S, Monteleone F, Zarantonello F, Sella N, De Cassai A, Navalesi P. Effects of non-invasive respiratory support in post-operative patients: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Crit Care. 2024 May 8;28(1):152. PMID: 38720332; PMCID: PMC11077852. [CrossRef]

- Abrard S, Rineau E, Seegers V, Lebrec N, Sargentini C, Jeanneteau A, Longeau E, Caron S, Callahan JC, Chudeau N, Beloncle F, Lasocki S, Dupoiron D. Postoperative prophylactic intermittent noninvasive ventilation versus usual postoperative care for patients at high risk of pulmonary complications: a multicentre randomised trial. Br J Anaesth. 2023 Jan;130(1):e160-e168. Epub 2022 Jan 5. PMID: 34996593. [CrossRef]

- Torres MF, Porfírio GJ, Carvalho AP, Riera R. Non-invasive positive pressure ventilation for prevention of complications after pulmonary resection in lung cancer patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019 Mar 6;3(3):CD010355. PMID: 30840317; PMCID: PMC6402531. [CrossRef]

- Schallom M, Cracchiolo L, Falker A, Foster J, Hager J, Morehouse T, Watts P, Weems L, Kollef M. Pressure Ulcer Incidence in Patients Wearing Nasal-Oral Versus Full-Face Noninvasive Ventilation Masks. Am J Crit Care. 2015 Jul;24(4):349-56; quiz 357. PMID: 26134336. [CrossRef]

- Emami Zeydi A, Zare-Kaseb A, Nazari AM, Ghazanfari MJ, Sarmadi S. Mask-related pressure injury prevention associated with non-invasive ventilation: A systematic review. Int Wound J. 2024 Jun;21(6):e14909. PMID: 38826030; PMCID: PMC11144948. [CrossRef]

- Matossian C, Song X, Chopra I, Sainski-Nguyen A, Ogundele A. The Prevalence and Incidence of Dry Eye Disease Among Patients Using Continuous Positive Airway Pressure or Other Nasal Mask Therapy Devices to Treat Sleep Apnea. Clin Ophthalmol. 2020 Oct 15;14:3371-3379. PMID: 33116388; PMCID: PMC7573305. [CrossRef]

- Fukutome T. Prevalence of continuous positive airway pressure-related aerophagia in obstructive sleep apnea: an observational study of 753 cases undergoing CPAP/BiPAP treatment in a sleep clinic - part one of a two-part series. Sleep Breath. 2024 Dec;28(6):2481-2489. Epub 2024 Aug 31. PMID: 39215936. [CrossRef]

- Destrebecq AL, Elia G, Terzoni S, Angelastri G, Brenna G, Ricci C, Spanu P, Umbrello M, Iapichino G. Aerophagia increases the risk of ventilator-associated pneumonia in critically-ill patients. Minerva Anestesiol. 2014 Apr;80(4):410-8. Epub 2013 Nov 26. PMID: 24280810.

- Schmidt M, Boutmy-Deslandes E, Perbet S, Mongardon N, Dres M, Razazi K, Guerot E, Terzi N, Andrivet P, Alves M, Sonneville R, Cracco C, Peigne V, Collet F, Sztrymf B, Rafat C, Reuter D, Fabre X, Labbe V, Tachon G, Minet C, Conseil M, Azoulay E, Similowski T, Demoule A. Differential Perceptions of Noninvasive Ventilation in Intensive Care among Medical Caregivers, Patients, and Their Relatives: A Multicenter Prospective Study-The PARVENIR Study. Anesthesiology. 2016 Jun;124(6):1347-59. PMID: 27035854. [CrossRef]

- Shah NM, Kaltsakas G. Respiratory complications of obesity: from early changes to respiratory failure. Breathe (Sheff). 2023 Mar;19(1):220263. Epub 2023 Mar 14. PMID: 37378063; PMCID: PMC10292783. [CrossRef]

- Lemyze M, Taufour P, Duhamel A, Temime J, Nigeon O, Vangrunderbeeck N, Barrailler S, Gasan G, Pepy F, Thevenin D, Mallat J. Determinants of noninvasive ventilation success or failure in morbidly obese patients in acute respiratory failure. PLoS One. 2014 May 12;9(5):e97563. PMID: 24819141; PMCID: PMC4018299. [CrossRef]

- Deppe, M., Lebiedz, P. Obesity (permagna) – Special features of invasive and noninvasive ventilation. Med Klin Intensivmed Notfmed 114 , 533–540 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Jennings M, Burova M, Hamilton LG, Hunter E, Morden C, Pandya D, Beecham R, Moyses H, Saeed K, Afolabi PR, Calder PC, Dushianthan A; REACT COVID-19 Investigators. Body mass index and clinical outcome of severe COVID-19 patients with acute hypoxic respiratory failure: Unravelling the “obesity paradox” phenomenon. Clin Nutr ESPEN. 2022 Oct;51:377-384. Epub 2022 Aug 6. PMID: 36184231; PMCID: PMC9356629. [CrossRef]

- Jaber S, Pensier J, Futier E, Paugam-Burtz C, Seguin P, Ferrandiere M, Lasocki S, Pottecher J, Abback PS, Riu B, Belafia F, Constantin JM, Verzilli D, Chanques G, De Jong A, Molinari N; NIVAS Study Group. Noninvasive ventilation on reintubation in patients with obesity and hypoxemic respiratory failure following abdominal surgery: a post hoc analysis of a randomized clinical trial. Intensive Care Med. 2024 Aug;50(8):1265-1274. Epub 2024 Jul 29. PMID: 39073580. [CrossRef]

- Carrillo A, Ferrer M, Gonzalez-Diaz G, Lopez-Martinez A, Llamas N, Alcazar M, Capilla L, Torres A. Noninvasive ventilation in acute hypercapnic respiratory failure caused by obesity hypoventilation syndrome and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012 Dec 15;186(12):1279-85. Epub 2012 Oct 26. PMID: 23103736. [CrossRef]

- Sequeira TCA, BaHammam AS, Esquinas AM. Noninvasive Ventilation in the Critically Ill Patient With Obesity Hypoventilation Syndrome: A Review. Journal of Intensive Care Medicine. 2016;32(7):421-428. [CrossRef]

- “Managing Acute Respiratory Decompensation in the Morbidly Obese.” Respirology., vol. 17, no. 5, 2012, pp. 759–71. [CrossRef]

- Bry C, Jaffré S, Guyomarc’h B, Corne F, Chollet S, Magnan A, Blanc FX. Noninvasive Ventilation in Obese Subjects After Acute Respiratory Failure. Respir Care. 2018 Jan;63(1):28-35. Epub 2017 Oct 3. PMID: 28974645. [CrossRef]

- Krewulak KD, Stelfox HT, Leigh JP, Ely EW, Fiest KM. Incidence and Prevalence of Delirium Subtypes in an Adult ICU: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Crit Care Med. 2018 Dec;46(12):2029-2035. PMID: 30234569. [CrossRef]

- Tabbì L, Tonelli R, Comellini V, Dongilli R, Sorgentone S, Spacone A, Paonessa MC, Sacchi M, Falsini L, Boni E, Ribuffo V, Bruzzi G, Castaniere I, Fantini R, Marchioni A, Pisani L, Nava S, Clini E; Respiratory Intensive Care Study group. Delirium incidence and risk factors in patients undergoing non-invasive ventilation for acute respiratory failure: a multicenter observational trial. Minerva Anestesiol. 2022 Oct;88(10):815-826. Epub 2022 Jun 15. PMID: 35708040. [CrossRef]

- Zhang R, Bai L, Han X, Huang S, Zhou L, Duan J. Incidence, characteristics, and outcomes of delirium in patients with noninvasive ventilation: a prospective observational study. BMC Pulm Med. 2021 May 11;21(1):157. PMID: 33975566; PMCID: PMC8111378. [CrossRef]

- Devlin, John W. PharmD, FCCM (Chair)1,2; Skrobik, Yoanna MD, FRCP(c), MSc, FCCM (Vice-Chair)3,4; Gélinas, Céline RN, PhD5; Needham, Dale M. MD, PhD6; Slooter, Arjen J. C. MD, PhD7; Pandharipande, Pratik P. MD, MSCI, FCCM8; Watson, Paula L. MD9; Weinhouse, Gerald L. MD10; Nunnally, Mark E. MD, FCCM11,12,13,14; Rochwerg, Bram MD, MSc15,16; Balas, Michele C. RN, PhD, FCCM, FAAN17,18; van den Boogaard, Mark RN, PhD19; Bosma, Karen J. MD20,21; Brummel, Nathaniel E. MD, MSCI22,23; Chanques, Gerald MD, PhD24,25; Denehy, Linda PT, PhD26; Drouot, Xavier MD, PhD27,28; Fraser, Gilles L. PharmD, MCCM29; Harris, Jocelyn E. OT, PhD30; Joffe, Aaron M. DO, FCCM31; Kho, Michelle E. PT, PhD30; Kress, John P. MD32; Lanphere, Julie A. DO33; McKinley, Sharon RN, PhD34; Neufeld, Karin J. MD, MPH35; Pisani, Margaret A. MD, MPH36; Payen, Jean-Francois MD, PhD37; Pun, Brenda T. RN, DNP23; Puntillo, Kathleen A. RN, PhD, FCCM38; Riker, Richard R. MD, FCCM29; Robinson, Bryce R. H. MD, MS, FACS, FCCM39; Shehabi, Yahya MD, PhD, FCICM40; Szumita, Paul M. PharmD, FCCM41; Winkelman, Chris RN, PhD, FCCM42; Centofanti, John E. MD, MSc43; Price, Carrie MLS44; Nikayin, Sina MD45; Misak, Cheryl J. PhD46; Flood, Pamela D. MD47; Kiedrowski, Ken MA48; Alhazzani, Waleed MD, MSc (Methodology Chair)16,49. Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Prevention and Management of Pain, Agitation/Sedation, Delirium, Immobility, and Sleep Disruption in Adult Patients in the ICU. Critical Care Medicine 46(9):p e825-e873, September 2018. |. [CrossRef]

- Girard TD, Exline MC, Carson SS, Hough CL, Rock P, Gong MN, Douglas IS, Malhotra A, Owens RL, Feinstein DJ, Khan B, Pisani MA, Hyzy RC, Schmidt GA, Schweickert WD, Hite RD, Bowton DL, Masica AL, Thompson JL, Chandrasekhar R, Pun BT, Strength C, Boehm LM, Jackson JC, Pandharipande PP, Brummel NE, Hughes CG, Patel MB, Stollings JL, Bernard GR, Dittus RS, Ely EW; MIND-USA Investigators. Haloperidol and Ziprasidone for Treatment of Delirium in Critical Illness. N Engl J Med. 2018 Dec 27;379(26):2506-2516. Epub 2018 Oct 22. PMID: 30346242; PMCID: PMC6364999. [CrossRef]

- Oh ES, Fong TG, Hshieh TT, Inouye SK. Delirium in Older Persons: Advances in Diagnosis and Treatment. JAMA. 2017;318(12):1161–1174. [CrossRef]

- Reade, M. C., & Finfer, S. (2014). Sedation and Delirium in the Intensive Care Unit. New England Journal of Medicine, 370(5), 444-454. [CrossRef]

- Yang B, Gao L, Tong Z. Sedation and analgesia strategies for non-invasive mechanical ventilation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Heart Lung. 2024 Jan-Feb;63:42-50. Epub 2023 Sep 26. PMID: 37769542. [CrossRef]

- Pandharipande PP, Pun BT, Herr DL, et al. Effect of Sedation With Dexmedetomidine vs Lorazepam on Acute Brain Dysfunction in Mechanically Ventilated Patients: The MENDS Randomized Controlled Trial. JAMA. 2007;298(22):2644–2653. [CrossRef]

- Purro A, Appendini L, De Gaetano A, Gudjonsdottir M, Donner CF, Rossi A. Physiologic determinants of ventilator dependence in long-term mechanically ventilated patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000 Apr;161(4 Pt 1):1115-23. PMID: 10764299. [CrossRef]

- Marchioni A, Tonelli R, Fantini R, Tabbì L, Castaniere I, Livrieri F, Bedogni S, Ruggieri V, Pisani L, Nava S, Clini E. Respiratory Mechanics and Diaphragmatic Dysfunction in COPD Patients Who Failed Non-Invasive Mechanical Ventilation. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2019 Nov 22;14:2575-2585. PMID: 31819395; PMCID: PMC6879385. [CrossRef]

- Burns KEA, Stevenson J, Laird M, Adhikari NKJ, Li Y, Lu C, He X, Wang W, Liang Z, Chen L, Zhang H, Friedrich JO. Non-invasive ventilation versus invasive weaning in critically ill adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Thorax. 2022 Aug;77(8):752-761. Epub 2021 Oct 29. PMID: 34716282. [CrossRef]

- Luo Z, Li Y, Li W, et al. Effect of High-Intensity vs Low-Intensity Noninvasive Positive Pressure Ventilation on the Need for Endotracheal Intubation in Patients With an Acute Exacerbation of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: The HAPPEN Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2024;332(20):1709–1722. [CrossRef]

- Yu J, Lee MR, Chen CT, Lin YT, How CK. Predictors of Successful Weaning from Noninvasive Ventilation in Patients with Acute Exacerbation of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: A Single-Center Retrospective Cohort Study. Lung. 2021 Oct;199(5):457-466. Epub 2021 Aug 21. PMID: 34420091; PMCID: PMC8380010. [CrossRef]

- Sellares J, Ferrer M, Anton A, Loureiro H, Bencosme C, Alonso R, Martinez-Olondris P, Sayas J, Peñacoba P, Torres A. Discontinuing noninvasive ventilation in severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbations: a randomised controlled trial. Eur Respir J. 2017 Jul 5;50(1):1601448. PMID: 28679605. [CrossRef]

- Venkatesan, P. GOLD COPD report: 2026 update. The Lancet Respiratory Medicine. [CrossRef]

- Duan J, Tang X, Huang S, Jia J, Guo S. Protocol-directed versus physician-directed weaning from noninvasive ventilation: the impact in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012 May;72(5):1271-5. PMID: 22673254. [CrossRef]

- Patel N, Howard IM, Baydur A. Respiratory considerations in patients with neuromuscular disorders. Muscle Nerve. 2023 Aug;68(2):122-141. Epub 2023 May 29. PMID: 37248745. [CrossRef]

- Kucukdemirci Kaya P, Iscimen R. Management of mechanical ventilation and weaning in critically ill patients with neuromuscular disorders. Respir Med. 2025 Feb;237:107951. Epub 2025 Jan 16. PMID: 39826762. [CrossRef]

- Chabert P, Bestion A, Fred AA, Schwebel C, Argaud L, Souweine B, Darmon M, Piriou V, Lehot JJ, Guérin C. Ventilation Management and Outcomes for Subjects With Neuromuscular Disorders Admitted to ICUs With Acute Respiratory Failure. Respir Care. 2021 Apr;66(4):669-678. Epub 2020 Dec 29. PMID: 33376187. [CrossRef]

- Bach JR, Gonçalves MR, Hamdani I, Winck JC. Extubation of patients with neuromuscular weakness: a new management paradigm. Chest. 2010 May;137(5):1033-9. Epub 2009 Dec 29. PMID: 20040608. [CrossRef]

- GBD 2021 Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of pulmonary arterial hypertension, 1990-2021: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet Respir Med. 2025 Jan;13(1):69-79. Epub 2024 Oct 18. PMID: 39433052; PMCID: PMC11698691. [CrossRef]

- Lowery MM, Hill NS, Wang L, Rosenzweig EB, Bhat A, Erzurum S, Finet JE, Jellis CL, Kaur S, Kwon DH, Nawabit R, Radeva M, Beck GJ, Frantz RP, Hassoun PM, Hemnes AR, Horn EM, Leopold JA, Rischard FP, Mehra R; Pulmonary Vascular Disease Phenomics (PVDOMICS) Study Group. Sleep-Related Hypoxia, Right Ventricular Dysfunction, and Survival in Patients With Group 1 Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2023 Nov 21;82(21):1989-2005. PMID: 37968017; PMCID: PMC11060475. [CrossRef]

- Long B, Brady WJ, Gottlieb M. Emergency medicine updates: Sympathetic crashing acute pulmonary edema. Am J Emerg Med. 2025 Apr;90:35-40. Epub 2025 Jan 5. PMID: 39799613. [CrossRef]

- Ammar MA, Sasidhar M, Lam SW. Inhaled Epoprostenol Through Noninvasive Routes of Ventilator Support Systems. Ann Pharmacother. 2018 Dec;52(12):1173-1181. Epub 2018 Jun 12. PMID: 29890848. [CrossRef]

- Sharma S, Fox H, Aguilar F, Mukhtar U, Willes L, Bozorgnia B, Bitter T, Oldenburg O. Auto positive airway pressure therapy reduces pulmonary pressures in adults admitted for acute heart failure with pulmonary hypertension and obstructive sleep apnea. The ASAP-HF Pilot Trial. Sleep. 2019 Jul 8;42(7):zsz100. PMID: 31004141. [CrossRef]

- Becker H, Grote L, Ploch T, Schneider H, Stammnitz A, Peter JH, Podszus T. Intrathoracic pressure changes and cardiovascular effects induced by nCPAP and nBiPAP in sleep apnoea patients. J Sleep Res. 1995 Jun;4(S1):125-129. PMID: 10607188. [CrossRef]

- Rajagopal, S., Ruetzler, K., Ghadimi, K., Horn, E. M., Kelava, M., Kudelko, K. T., Moreno-Duarte, I., Preston, I., Rose Bovino, L. L., Smilowitz, N. R., Vaidya, A., on behalf of the American Heart Association Council on Cardiopulmonary, C. C. P., Resuscitation, the Council on, C., & Stroke, N. (2023). Evaluation and Management of Pulmonary Hypertension in Noncardiac Surgery: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation, 147(17), 1317-1343. [CrossRef]

- Yu L, Chen X, Wang X, Cui R. Efficacy and safety of high-flow nasal cannula versus noninvasive ventilation for pulmonary arterial hypertension-associated acute respiratory failure: A retrospective cohort study stratified by the severity of right ventricular dysfunction. Medicine (Baltimore). 2025 Jul 4;104(27):e43185. PMID: 40629562; PMCID: PMC12237310. [CrossRef]

- Pinsky MR. Cardiovascular issues in respiratory care. Chest. 2005 Nov;128(5 Suppl 2):592S-597S. PMID: 16306058. [CrossRef]

- Trivedi V, Chaudhuri D, Jinah R, Piticaru J, Agarwal A, Liu K, McArthur E, Sklar MC, Friedrich JO, Rochwerg B, Burns KEA. The Usefulness of the Rapid Shallow Breathing Index in Predicting Successful Extubation: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Chest. 2022 Jan;161(1):97-111. Epub 2021 Jun 26. PMID: 34181953. [CrossRef]

- Poddighe D, Van Hollebeke M, Choudhary YQ, Campos DR, Schaeffer MR, Verbakel JY, Hermans G, Gosselink R, Langer D. Accuracy of respiratory muscle assessments to predict weaning outcomes: a systematic review and comparative meta-analysis. Crit Care. 2024 Mar 7;28(1):70. PMID: 38454487; PMCID: PMC10919035. [CrossRef]

- Faverio P, Stainer A, De Giacomi F, Messinesi G, Paolini V, Monzani A, Sioli P, Memaj I, Sibila O, Mazzola P, Pesci A. Noninvasive Ventilation Weaning in Acute Hypercapnic Respiratory Failure due to COPD Exacerbation: A Real-Life Observational Study. Can Respir J. 2019 Mar 25;2019:3478968. PMID: 31019611; PMCID: PMC6452557. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.