Submitted:

01 January 2026

Posted:

02 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Evidence Base for Sleep and Stress Management

2.1. Sleep and Neurodegeneration: Controlling “Conditions for Worsening,” Not Treatment

2.2. Stress, Emotion, and BPSD Management: Non-Pharmacological Interventions as First Line

3. Why Standard Sleep Hygiene and Stress Coping Often Fail in Dementia

3.1. Cognitive and Executive Constraints

3.2. Nighttime Problems as Environmental Design Issues, Not Patient Effort

3.3. More Is Not Always Better: The Implementation Gap Highlighted by PrAISED

3.4. Redefining Design Assumptions for Sleep and Stress Interventions

4. Dementia-Adapted Sleep & Stress Management Framework (D-SSM)

4.1. Design Principles

5. D-SSM Intervention Protocol (for Implementation)

5.1. Overall Structure

- Duration: Continuous (minimum 12 weeks)

- Frequency: Daily (each item requires only a few minutes)

- Recording: Simple caregiver checklist

- Setting: Home or institutional care

5.2. Sleep and Daily Rhythm Module (Three Mandatory Items)

5.3. Stress, Emotion, and BPSD Module (Three Mandatory Items + DICE)

5.4. Weekly Standardization Meeting

5.5. Progression Rule

5.6. Key Performance Indicators (Cost-Linked)

6. Implications for Research, Practice, and Policy

7. Conclusion

Appendix A

- To cure dementia itself

- To stop or reverse disease progression

- To reduce the frequency and severity of nighttime agitation, delirium, and BPSD

- To prevent acute events such as falls, emergency visits, and hospitalization

- To reduce the number of nighttime responses required of caregivers and to alleviate caregivers’ psychological and physical burden

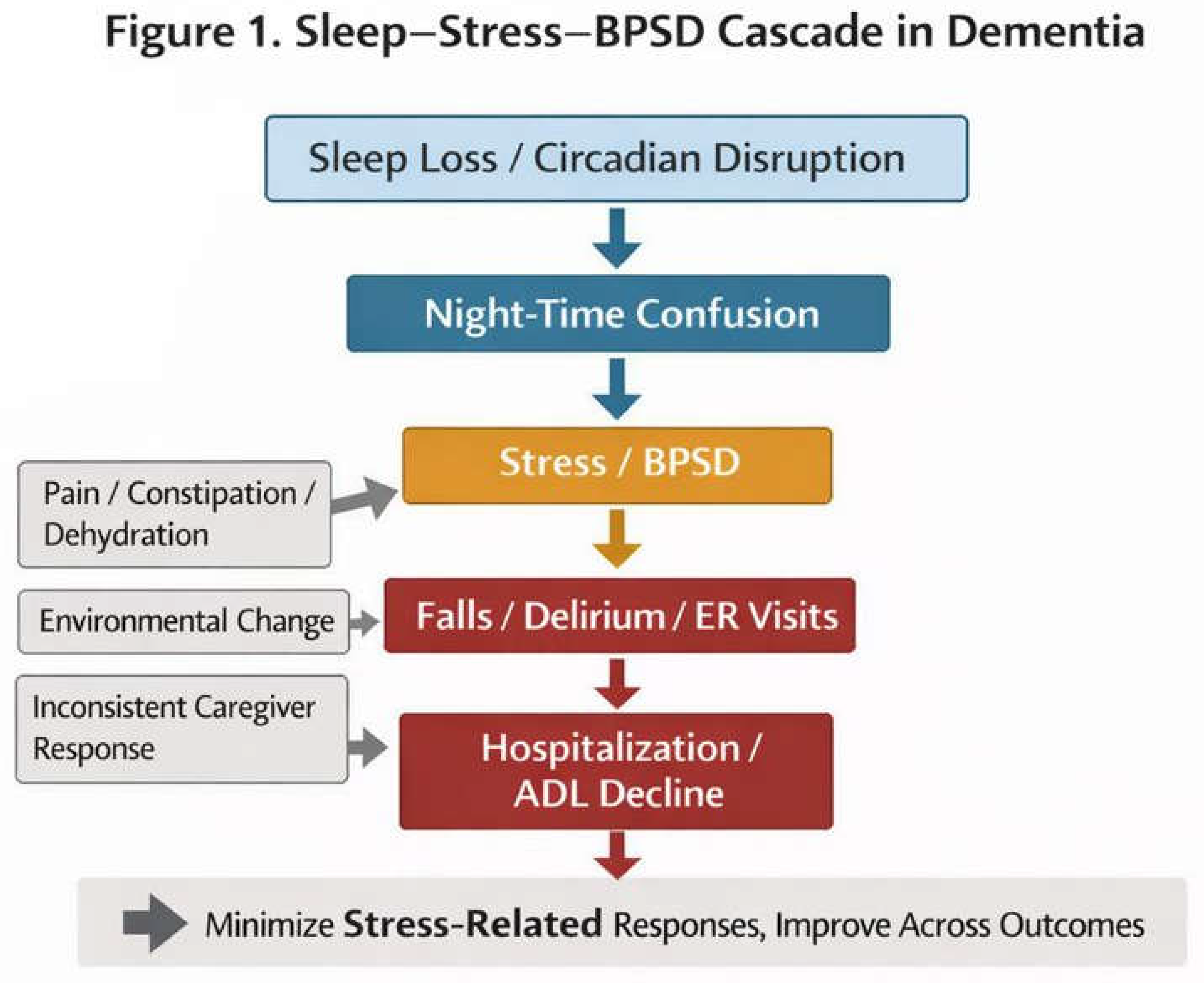

- Sleep disturbance and breakdown of circadian rhythms

- Nighttime agitation and confusion

- Manifestation of BPSD (irritability, refusal, wandering, etc.)

- Falls, delirium, and emergency visits

- Hospitalization, abrupt decline in ADL, and institutionalization

- Physical discomfort (pain, constipation, dehydration, urinary urgency, etc.)

- Environmental factors (noise, lighting, temperature, schedule changes)

- Variability in caregivers’ responses

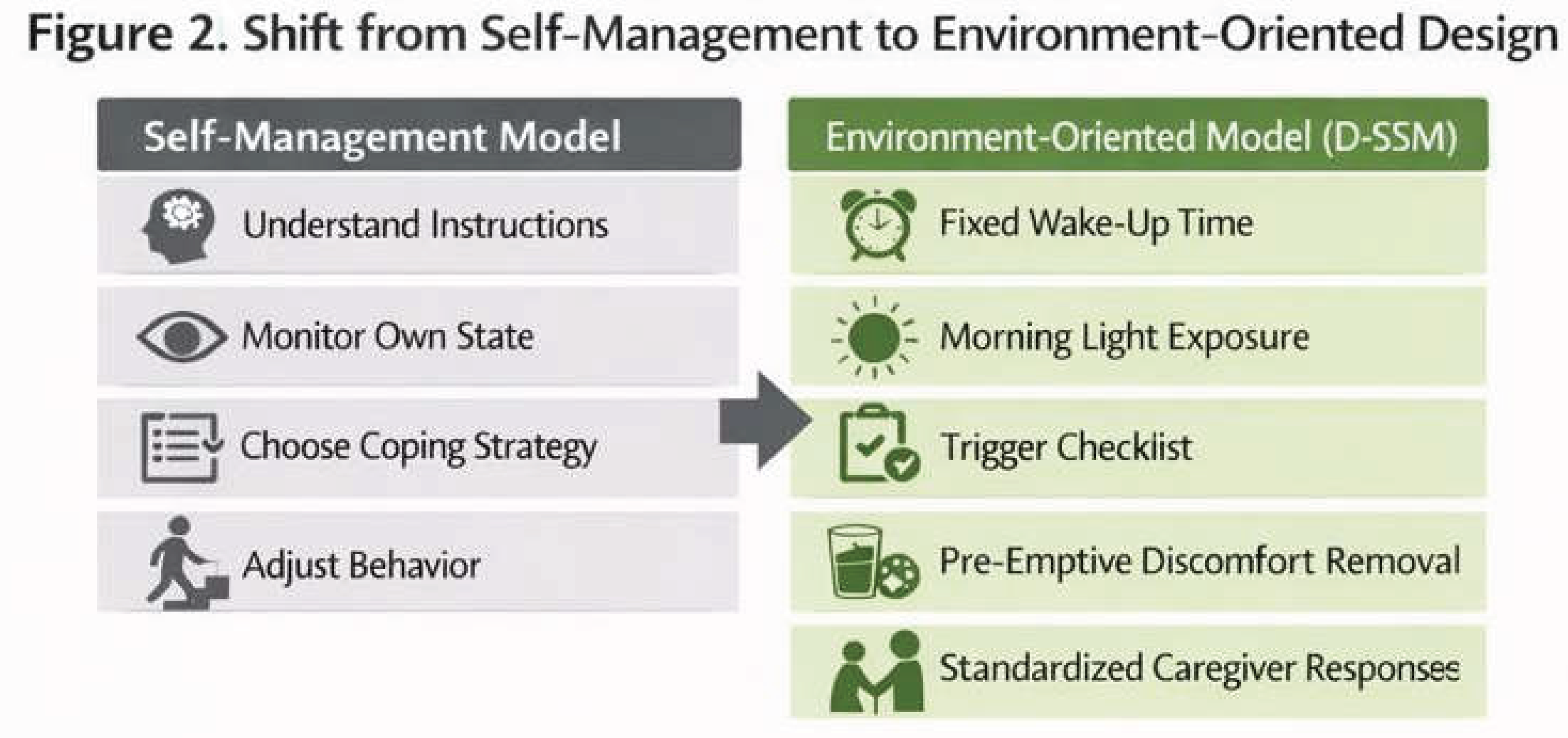

- Do not leave behavioral choice, memory, or self-regulation to the person

- Fix the contents, order, and timing of what is done

- Avoid exceptional operations as much as possible

- Do not center the approach on handling sleepless nights

- Improve nighttime sleep indirectly by stabilizing wake time and the morning environment

- Do not interpret anger, refusal, or agitation as intentional behavior

- Treat them as reactions to some form of discomfort or difficulty

- Do not adopt designs that assume caregiver exhaustion

- Emphasize operations that are short, simple, and shareable among multiple people

- Wake up at the same time every day regardless of bedtime

- Do not “adjust” by sleeping in

- Did the person wake up at the scheduled time today?

- Use natural outdoor light exposure as the default (about 5–15 minutes)

- If difficult, substitute with a bright indoor environment

- Did the person receive sufficient light after waking?

- Limit naps to within 30 minutes

- Keep naps before 3:00 p.m.

- If possible, use a chair rather than a bed

- Was the nap short and taken early in the day?

- Lack of sleep

- Urinary urgency / toileting discomfort

- Constipation

- Possible pain

- Dehydration

- Hunger

- Environmental stimuli such as noise and lighting

- Sudden changes in schedule or environment

- Do not make it standard practice to respond only after behavioral problems become apparent

- Adjust physical discomfort and environmental stimuli in advance

- If restlessness is observed, first guide to the toilet or provide fluids

- If irritability is high, move to a low-stimulation environment

- Do not deny

- Do not correct

- Do not rush

- “It’s okay.”

- “Let’s do it together.”

- “I’m here with you.”

- Describe: What happened, when, and where

- Investigate: Whether urinary urgency, pain, sleepiness, or environmental stimulation were present

- Create: Environmental adjustment, changes in verbal approach, preemptive responses

- Evaluate: Share and evaluate the response the next day

- Share among family or staff what responses worked well

- Standardize verbal approaches and environmental adjustments

- Viewing sleep problems as the person’s responsibility

- Forcing the person to go to bed

- Physically restraining behavior

- Changing responses depending on each situation

- Having a caregiver handle problems alone without support

- Number of nighttime responses required

- Frequency of agitation / irritable behavior

- PRN use or dose increases of psychotropic medications

- Occurrence of falls, emergency visits, and hospitalization

- Cure of dementia

- Elimination of all BPSD

- Stopping of disease progression

References

- Amieva, H.; Stoykova, R.; Matharan, F.; Helmer, C.; Antonucci, T. C.; Dartigues, J. F. What aspects of social network are protective for dementia? Not the quantity but the quality of social interactions is protective up to 15 years later. Psychosomatic Medicine 2010, 72(9), 905–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Booth, V.; Hood-Moore, V.; Logan, P.; et al. Promoting activity, independence and stability in early dementia and mild cognitive impairment (PrAISED): Development of an intervention. Clinical Rehabilitation 2018, 32(7), 855–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen-Mansfield, J.; Thein, K.; Dakheel-Ali, M.; Marx, M. S. The underlying meaning of stimuli: Impact on engagement of persons with dementia. Psychiatry Research 2010, 177(1–2), 216–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harwood, R. H.; Goldberg, S. E.; Brand, A.; et al. Promoting Activity, Independence and Stability in Early Dementia and Mild Cognitive Impairment (PrAISED): A randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2023, 382, e074787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kales, H. C.; Gitlin, L. N.; Lyketsos, C. G. Assessment and management of behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia. BMJ 2015, 350, h369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Livingston, G.; Sommerlad, A.; Orgeta, V.; et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care. The Lancet 2017, 390(10113), 2673–2734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Musiek, E. S.; Holtzman, D. M. Mechanisms linking circadian clocks, sleep, and neurodegeneration. Science 2016, 354(6315), 1004–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Holtzman, D. M. Bidirectional relationship between sleep and Alzheimer’s disease: Role of amyloid, tau, and other factors. Neuropsychopharmacology 2020, 45(1), 104–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).