1. Introduction

AI-enabled fitness services collect activity, physiological, and location data for guidance and monitoring, which can create privacy and security concerns. Yet many users continue using these services while reporting privacy worry, a pattern often discussed as a privacy paradox [

1,

2].

Recent work suggests that the phenomenon varies by domain and is shaped by contextual constraints rather than simple inconsistency [

3,

4]. Scenario-based security education research demonstrates that heightened awareness of vulnerabilities does not automatically translate into protective behavior, especially when perceived benefits and convenience sustain continued engagement [

8]. Compared with general social media, AI fitness involves more sensitive health-related data and tangible, recurring benefits, making privacy--use tension salient in everyday decisions [

5,

6,

7]. In this setting, examining how privacy concern and high use co-vary provides insight into how users manage perceived risk when disengagement is unlikely.

Because data disclosure is continuous in this setting, it is useful to examine how privacy concern and high use co-vary along a spectrum rather than treating the paradox as a binary condition.

From a governance angle, security education can improve awareness and protective practices [

8], while studies on public-service platforms show that misaligned information and accountability chains may suppress usage even when services are technically available [

9]. AI fitness presents the contrasting case: services are widely used despite unresolved privacy tension, raising a descriptive question about how users manage perceived risk when disengagement is unlikely.

Building on the Satisficing Equilibrium (SE) perspective, which emphasizes “good-enough” configurations under bounded rationality rather than theoretical optima [

10], this study examines AI fitness as a user-side, single-domain case. Using survey data from 596 adults (age ≥ 18), we construct a Deviation index (standardized privacy concern minus standardized risk acceptance) and examine how fitted high-use probability varies across this index. Perceived transparency (Information Control Level, ICL) and privacy trade-off attitudes are included as contextual factors. The contribution is primarily descriptive: we describe how high-use likelihood varies across the worry–risk configuration across the worry–risk configuration and discuss the pattern in relation to privacy satisficing and governance-oriented discussions of security education and platform conditions [

2,

3,

4,

5,

8,

9,

10].

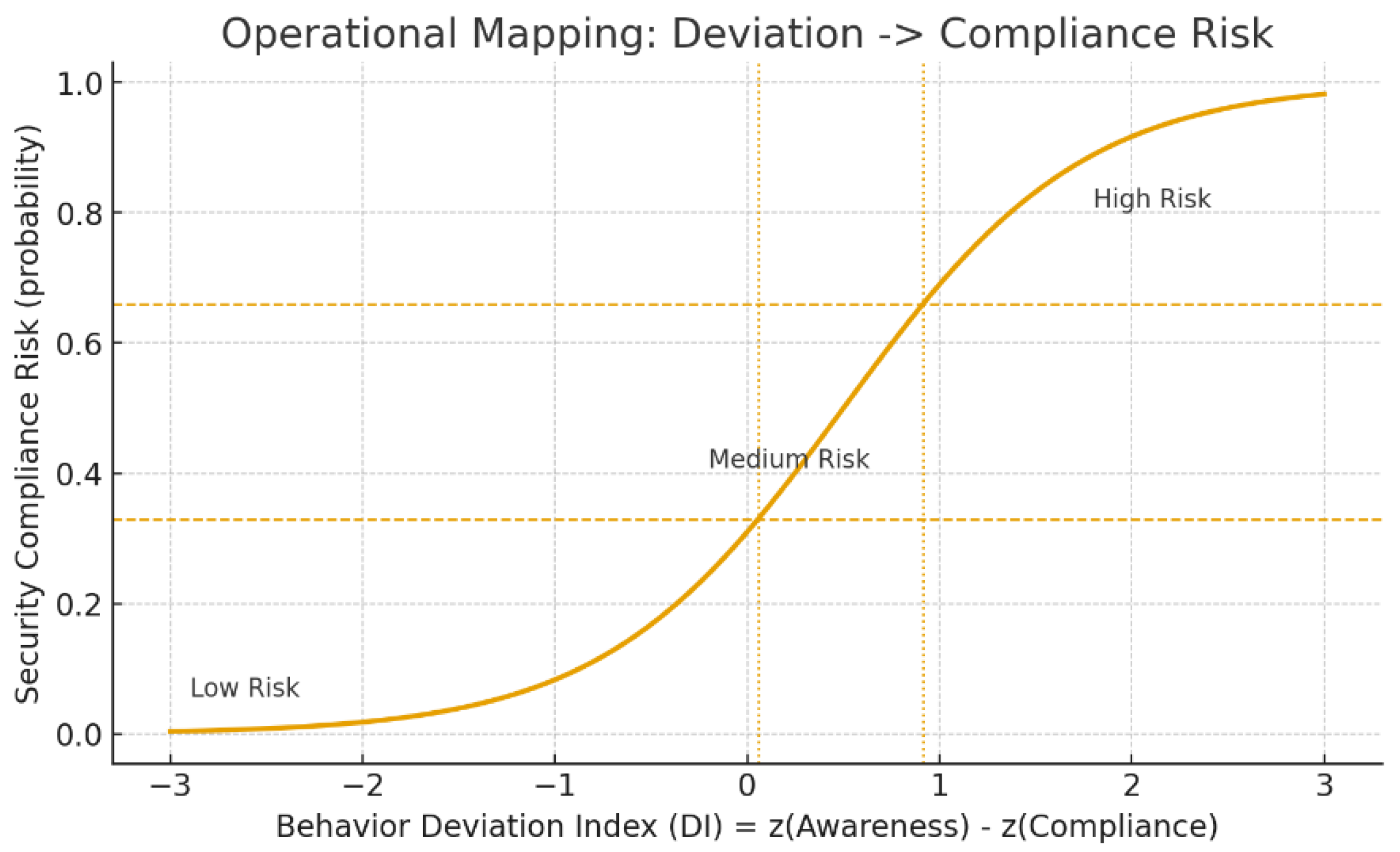

Figure 1 provides a conceptual overview.

Figure 1.

Conceptual illustration of the privacy satisficing perspective in AI fitness. Note. Deviation denotes standardized privacy concern minus standardized risk acceptance; ICL and privacy trade-off are contextual factors. The figure is conceptual; empirical results appear in

Figure 2.

Figure 1.

Conceptual illustration of the privacy satisficing perspective in AI fitness. Note. Deviation denotes standardized privacy concern minus standardized risk acceptance; ICL and privacy trade-off are contextual factors. The figure is conceptual; empirical results appear in

Figure 2.

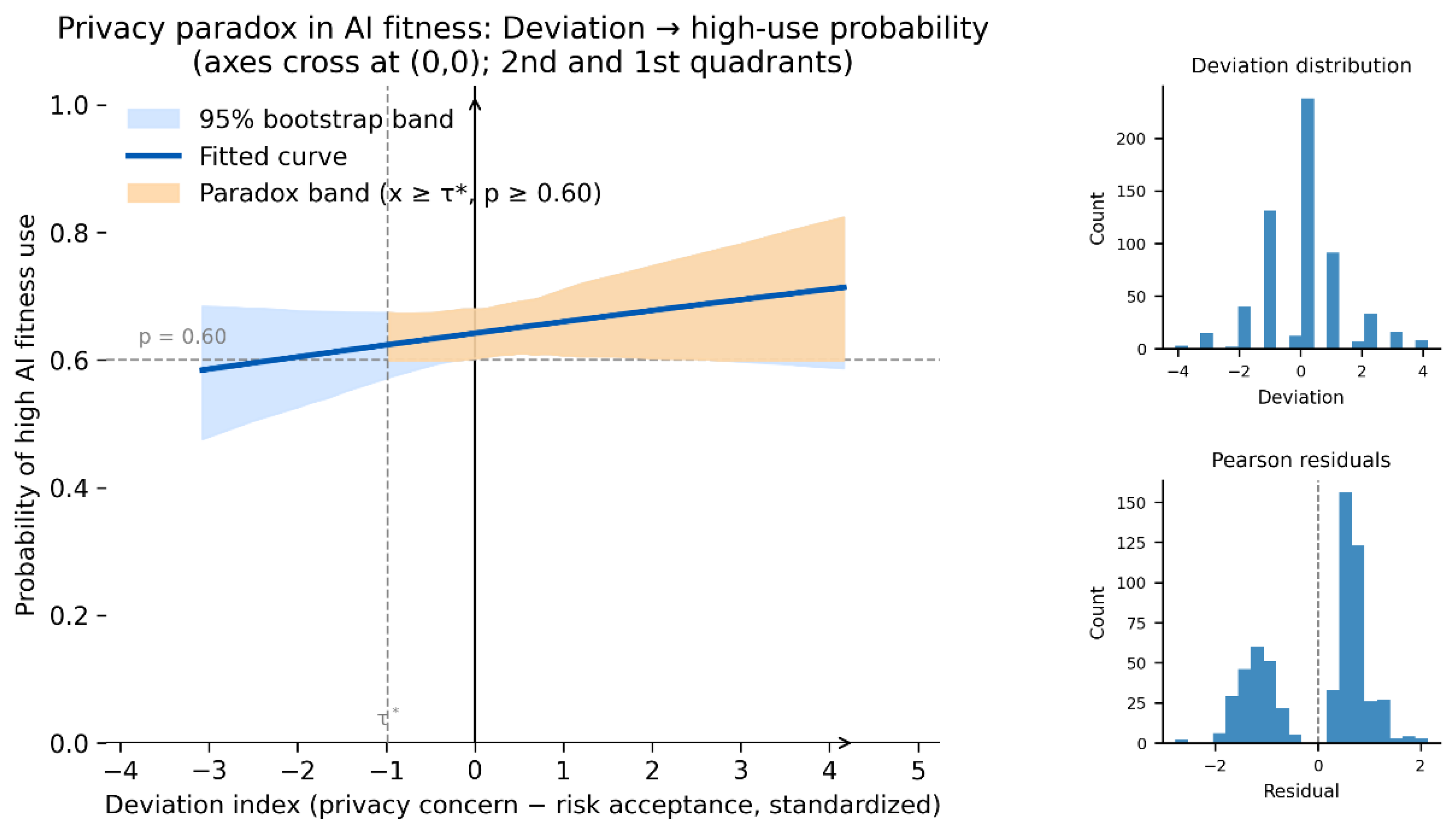

Figure 2.

Gradual privacy paradox in AI fitness: predicted probability of high use across the Deviation index (adult-only sample). Note. Fitted probabilities are plotted across Deviation with ICL and privacy trade-off held at their sample means. The shaded area indicates a 95% confidence band. Reference lines at p = 0.60 and τ are included for visual interpretation; side panels show the Deviation distribution and Pearson residuals.

Figure 2.

Gradual privacy paradox in AI fitness: predicted probability of high use across the Deviation index (adult-only sample). Note. Fitted probabilities are plotted across Deviation with ICL and privacy trade-off held at their sample means. The shaded area indicates a 95% confidence band. Reference lines at p = 0.60 and τ are included for visual interpretation; side panels show the Deviation distribution and Pearson residuals.

2. Theoretical Background

The privacy paradox refers to the gap between stated privacy concern and continued disclosure or tracking acceptance [

1,

2]. In digital health and AI fitness, this tension can be salient because services rely on ongoing, health-related data while offering recurring benefits such as feedback and self-management support [

5,

6,

7]. Prior studies on fitness trackers and wearables similarly report that privacy concern may coexist with sustained use [

5,

6,

7,

11,

12]. To organize this pattern, we adopt a privacy-satisficing lens grounded in bounded rationality and SE-oriented reasoning: rather than continuously optimizing privacy, individuals may tolerate a perceived risk level as long as benefits and basic safeguards appear “good enough” for everyday practice [

10,

14,

15]. Related risk perspectives likewise describe behavior as adjusting around a subjectively acceptable risk level rather than eliminating risk [

16].

Operationally, we define a Deviation index as the standardized difference between privacy concern and risk acceptance: Deviation = z(privacy concern) − z(risk acceptance). Lower (or negative) Deviation indicates lower concern and/or higher willingness to accept risk, whereas higher Deviation indicates a worry-dominant configuration. Treating Deviation as a continuous positioning measure allows us to examine whether fitted high-use probability varies smoothly across the worry–risk configuration rather than treating the paradox as a binary state. In the empirical models, we additionally account for perceived transparency (Information Control Level, ICL) and privacy trade-off attitudes as contextual factors [

5,

6,

7,

10]

.

This framing is consistent with security-awareness research showing that greater awareness does not necessarily translate into reduced use in high-benefit settings, where convenience, habits, or contextual pressures sustain continued engagement [

8,

10,

13,

17]. At a broader platform level, platform disconnection studies highlight how misaligned information, feedback, and responsibility chains can suppress usage even when services are technically available [

9]. AI fitness presents a contrasting configuration: services are typically accessible and actively used, while privacy and security concerns may remain salient. Accordingly, we treat AI fitness privacy as a case of continued use under acknowledged risk and we focus on how Deviation, perceived transparency (ICL), and trade-off attitudes relate to continued use patterns within the observed sample, without assuming a single optimal level of privacy behavior [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

13,

17,

18].

3. Methods

3.1. Data and Sample

This study uses data from an online survey on AI-enabled fitness services administered via Tencent Questionnaire (Tencent Wenjuan), a widely used survey platform operated by Tencent Technology Co., Ltd. The survey page received 645 views and 633 submissions; after data cleaning, 596 valid responses were retained. Invalid cases were excluded based on three criteria: (1) unrealistically short completion times (below 35 seconds); (2) duplicate response patterns across accounts or devices, with only one response retained per user; and (3) respondents under 18 years of age. The final dataset therefore consists exclusively of adult respondents (age ≥ 18). Tencent Questionnaire requires login via QQ, WeChat, email, or a mainland China mobile number and restricts each account to a single submission, which helps reduce duplicate entries. Most responses originated from mainland China (N = 537), with additional responses from the Republic of Korea (N = 58) and other regions (N = 1). The questionnaire covered platform use, perceived transparency and safety, service adequacy, willingness to use AI fitness services, privacy attitudes, and basic demographics (gender, age group, app-use experience). Perceptual items were measured using five-point Likert scales.

At the start of the survey, participants were informed (in Chinese and English) that the study targeted adults aged 18 and above, that participation was voluntary, and that no personally identifiable or sensitive information would be collected. Responses were anonymous, could be discontinued at any time, and were analyzed only in aggregated form for academic purposes. The study was designed as an anonymous, adult-only questionnaire without intervention, physical procedures, or the collection of identifiable personal data, and therefore falls within the scope of minimal-risk social science research. The research procedures were conducted in accordance with generally accepted ethical principles for human-subject research, including those articulated in the Declaration of Helsinki. Institutional ethics review consultation is currently in progress, and the final ethics status will be reported in the journal version if required.

3.2. Variables and Analytical Strategy

The dependent variable is high willingness to use AI fitness services. The original five-point item on “willingness to use AI fitness applications/devices” is recoded into a binary indicator for descriptive grouping and a parsimonious probability model: respondents at or above the sample median are coded as 1 (high-use group) and others as 0 (low-use group). This operationalization follows a common practice in prior studies that contrast relatively higher versus lower intention rather than relying on the full ordinal scale [

5,

6,

11,

12].

The key explanatory variable is the Deviation index, defined in Section 2.1 as the standardized difference between privacy concern and risk acceptance (z-privacy concern − z-risk acceptance). Larger Deviation values indicate that privacy concern is higher relative to stated risk acceptance, whereas lower or negative values indicate the opposite configuration. Importantly, Deviation is used here as a descriptive positioning measure within the sample and should not be interpreted as an objective risk or compliance metric [

2,

11,

12].

To capture perceived service context, we include two additional predictors. Perceived transparency (ICL) aggregates items on visible information, accountability expectation, and reliability/safety, summarizing how clearly respondents perceive information provision and safety-related assurances [

7,

10]. Privacy trade-off is measured by an item capturing the stated willingness to exchange personal data for convenience or improved service, consistent with privacy-calculus discussions of protection–service trade-offs [

2,

11]. Both variables are treated as continuous indices derived from Likert-scale items; composite-score construction follows standard index-building guidance [

21]. Gender (coded as 1 = female), age group, and prior app-use experience are included as control variables in extended specifications.

The analysis proceeds in two steps. First, we summarize the distribution of key variables and, for descriptive presentation, classify respondents into low-, medium-, and high-Deviation bands to examine how the share of high-use respondents varies across the Deviation spectrum. Second, we estimate logistic regression models with high-use membership as the dependent variable and Deviation, ICL, and privacy trade-off as the main predictors, with optional demographic controls. Logistic regression is used to model a binary outcome and to present results in terms of fitted probabilities [

19,

20]. The goal is to assess whether the fitted probability of high AI fitness use varies smoothly across Deviation after accounting for perceived transparency and stated privacy–convenience trade-offs, consistent with a privacy-satisficing interpretation framed as a descriptive pattern rather than a causal claim [

10].

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Patterns and User Types

Overall willingness to use AI fitness services is moderate to high in this sample. Using a median split of the five-point willingness item, a majority of respondents are classified into the high-use group (

Table 1). Privacy concern is generally mid-to-high, while risk acceptance shows greater dispersion, indicating heterogeneous tolerance for perceived risk alongside continued service interest [

2,

5,

6,

7,

11,

12].

For descriptive presentation, respondents are grouped into low-, medium-, and high-Deviation bands. High-use shares are compared across these bands as a simple descriptive check, motivating the probability-based analysis reported below [

5,

6,

7,

10].

4.2. Logistic Regression and the Gradual Privacy Paradox

Table 2 reports logistic regression estimates with high-use membership as the dependent variable and Deviation, perceived transparency (ICL), and privacy trade-off as the main predictors. In this specification, the estimated coefficient for Deviation is positive. The coefficients for ICL and privacy trade-off are likewise positive, consistent with higher fitted probabilities of high use under greater perceived transparency and stronger acceptance of privacy–convenience trade-offs.

To visualize the association for Deviation,

Figure 2 plots fitted high-use probability across the observed Deviation range while holding ICL and privacy trade-off at their sample means. The fitted curve increases smoothly across Deviation, and the confidence band indicates uncertainty around the fitted relationship. Reference lines at p = 0.60 and τ* are included as visual aids.

5. Discussion and Conclusion

5.1. Gradual Privacy Paradox as Privacy Satisficing

Across the models and visual summaries, fitted high-use probability varies systematically with the Deviation index. In this sample, higher Deviation (privacy concern higher relative to risk acceptance) is not accompanied by lower willingness to use AI fitness services; instead, fitted high-use probability varies gradually across the observed Deviation range (

Figure 2). This pattern is consistent with a privacy-satisficing interpretation under bounded rationality, where users may continue using high-benefit services while tolerating nonzero concern, provided perceived benefits and basic safeguards appear “good enough” for everyday practice [

10,

14,

15,

16].

In relation to governance-oriented discussions, the pattern contrasts with platform disconnection settings in which services remain technically available but are underused due to misaligned information and accountability chains [

9]. It is also consistent with security-awareness research suggesting that increased awareness does not necessarily translate into avoidance when convenience, habit, or perceived benefits sustain continued engagement [

10,

13,

17,

18]. Here, the empirical aim is to document the co-occurrence of concern and continued use in a simple, interpretable form rather than to attribute it to a single causal mechanism [

2,

5,

6,

7,

10,

14,

15,

16].

5.2. Implications and Limitations

A practical implication is that awareness-raising by itself may not be sufficient to change usage patterns in high-benefit contexts. Governance and design efforts may therefore benefit from visible, usable privacy controls and clear communication of what data are collected and how they are processed, consistent with privacy-by-design approaches and calibrated reliance in automation [

7,

10,

17,

18,

22,

23]. Under a satisficing framing, the emphasis shifts from pushing users toward full acceptance or full rejection to keeping continued-use conditions transparent and auditable, with conservative defaults and actionable choices [

7,

10,

14,

15,

22,

23]. This study has limitations. The data are cross-sectional and self-reported, so associations should not be interpreted as causal, and bidirectional relationships cannot be ruled out. The sample reflects adults with interest or exposure to AI fitness and may not generalize to non-users or clinical populations. The modeling strategy is intentionally simple and intended for pattern description rather than exhaustive explanation [

19,

20]. The sample is China-dominant due to the survey platform and recruitment context, so cross-region generalization should be cautious.

Future work could extend the approach using longitudinal designs or behavioral traces and compare the Deviation–use pattern across other AI-enabled services to assess domain variability [

2,

3,

5,

6,

7,

11,

12].

Author Contributions

To be completed in the journal version.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was designed as an anonymous, adult-only online questionnaire without intervention or the collection of identifiable personal data. It falls within the scope of minimal-risk social science research. Institutional ethics review consultation is currently in progress, and the final ethics status will be reported in the journal version if required.

Informed Consent Statement

All participants provided electronic informed consent before participation and could withdraw at any time without penalty.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request and subject to ethical and institutional restrictions.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the corresponding author for guidance on research design and ethics consultation during the preparation of this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- P. F. Wu, “The privacy paradox in the context of online social networking: A self-identity perspective,” Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, Vol. 70, No. 3, pp. 207–217, 2019. [CrossRef]

- T. Dinev and P. Hart, “An extended privacy calculus model for e-commerce transactions,” Information Systems Research, Vol. 17, No. 1, pp. 61–80, 2006. [CrossRef]

- R. S. Hirschprung, “Is the privacy paradox a domain-specific phenomenon?,” Computers, Vol. 12, Article No. 156, 2023. [CrossRef]

- E. Arzoglou, Y. Kortesniemi, S. Ruutu, and T. Elo, “The Role of Privacy Obstacles in Privacy Paradox: A System Dynamics Analysis,” Systems, Vol. 11, No. 4, Article No. 205, 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. Abdelhamid, “Fitness tracker information and privacy management: Empirical study,” Journal of Medical Internet Research, Vol. 23, No. 11, Article No. e23059, 2021. [CrossRef]

- H. Kang and E. H. Jung, “The smart wearables–privacy paradox: A cluster analysis of smartwatch users,” Behaviour & Information Technology, Vol. 40, No. 16, pp. 1755–1768, 2021. [CrossRef]

- P. Zhang, M. N. K. Boulos et al., “Privacy-by-design environments for large-scale health research and federated learning from data,” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, Vol. 19, Article No. 11876, 2022. [CrossRef]

- G. So, “A study on scenario-based web application security education method,” The International Journal of Internet, Broadcasting and Communication, Vol. 15, No. 3, pp. 149–159, 2023. [CrossRef]

- H. Su and G. So, “Platform disconnection in rural revitalization: A multi-level analysis with reference to East Asia,” The International Journal of Internet, Broadcasting and Communication, Vol. 17, No. 3, pp. 183–196, 2025. [CrossRef]

- H. Su, J. Liao, and G. So, “Satisficing equilibrium and multi-actor trust in AI-enabled smart tourism: Nonlinear evidence from digital governance dynamics,” Preprints, 2025. [CrossRef]

- J. Y. Cho, D. Ko, and B. G. Lee, “Strategic approach to privacy calculus of wearable device user regarding information disclosure and continuance intention,” KSII Transactions on Internet and Information Systems, Vol. 12, No. 7, pp. 3356–3374, 2018. [CrossRef]

- R. Reith, C. Buck, B. Lis, and T. Eymann, “Integrating privacy concerns into the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology to explain the adoption of fitness trackers,” International Journal of Innovation and Technology Management, Vol. 17, No. 7, Article No. 2050049, 2020. [CrossRef]

- B. Lebek, J. Uffen, M. Neumann, B. Hohler, and M. H. Breitner, “Information security awareness and behavior: A theory-based literature review,” Management Research Review, Vol. 37, No. 12, pp. 1049–1092, 2014. [CrossRef]

- H. A. Simon, “A behavioral model of rational choice,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 69, No. 1, pp. 99–118, 1955. [CrossRef]

- G. Lilly, “Bounded rationality: A Simon-like explication,” Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control, Vol. 18, No. 1, pp. 205–230, 1994. [CrossRef]

- G. J. S. Wilde, “The Theory of Risk Homeostasis: Implications for Safety and Health,” Risk Analysis, Vol. 2, No. 4, pp. 209–225, 1982. [CrossRef]

- F. Bu and L. Ji, “Research on privacy-by-design behavioural decision-making of information engineers considering perceived work risk,” Systems, Vol. 12, Article No. 250, 2024. [CrossRef]

- J. D. Lee and K. A. See, “Trust in Automation: Designing for Appropriate Reliance,” Human Factors, Vol. 46, No. 1, pp. 50–80, 2004. [CrossRef]

- D. W. Hosmer, S. Lemeshow, and R. X. Sturdivant, Applied Logistic Regression, 3rd ed. Hoboken, NJ, USA: Wiley, 2013. [CrossRef]

- T. D. Mize, “Best practices for estimating, interpreting, and presenting average marginal effects,” Sociological Science, Vol. 6, pp. 81–117, 2019. [CrossRef]

- M. Nardo, M. Saisana, A. Saltelli, S. Tarantola, A. Hoffmann, and E. Giovannini, Handbook on Constructing Composite Indicators: Methodology and User Guide. Paris, France: OECD Publishing, 2008. [CrossRef]

- L. Aquilino, C. Di Dio, F. Manzi, D. Massaro, P. Bisconti, and A. Marchetti, “Decoding trust in artificial intelligence: A systematic review of quantitative measures and related variables,” Informatics, Vol. 12, Article No. 70, 2025. [CrossRef]

- L. A. Gordon and M. P. Loeb, “The economics of information security investment,” ACM Transactions on Information and System Security, Vol. 5, pp. 438–457, 2002. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).