1. Introduction

Smart city infrastructures increasingly rely on dense and reliable wireless connectivity to support public services, large-scale Internet of Things (IoT) deployments, campus networks, and outdoor urban applications. In such scenarios, wireless propagation is inherently three-dimensional and strongly influenced by complex building geometry and spatial layout, as illustrated by the real-world campus environment considered in this study (

Figure 1).

In this context, Wi-Fi has evolved beyond its traditional indoor role and has become a key access technology for urban-scale connectivity due to its cost efficiency, operation in unlicensed spectrum, and continuous evolution toward higher throughput and lower latency [

1,

2,

3]. Recent studies emphasize that next-generation Wi-Fi systems are expected to play a complementary role to cellular technologies in smart cities by enabling flexible, high-capacity access in outdoor and semi-outdoor environments such as campuses, pedestrian zones, and transportation hubs [

4,

5].

Providing accurate insights into Wi-Fi coverage in such scenarios is challenging due to the inherently three-dimensional (3D) nature of urban environments. Buildings of varying heights, irregular layouts, vegetation, and street canyons significantly influence radio propagation through reflection, diffraction, and shadowing effects, resulting in strong spatial variability of signal strength and link quality. Simplified two-dimensional planning assumptions and empirical propagation models are therefore often insufficient to capture the dominant physical mechanisms governing outdoor Wi-Fi performance in dense urban areas [

6,

7,

8].

Deterministic ray-tracing techniques are widely regarded as one of the most physically accurate approaches for modeling wireless propagation in complex 3D environments [

6]. By explicitly simulating electromagnetic interactions between radio waves and surrounding structures, ray tracing enables detailed analysis of multipath propagation, frequency-dependent attenuation, and non-line-of-sight behavior [

6,

7]. The increasing availability of high-resolution geographic data, such as OpenStreetMap (OSM), has further facilitated the construction of large-scale, realistic 3D urban radio environments. Such simulation-based representations align closely with the concept of a

digital twin, in which a virtual replica of the physical environment is used to analyze, predict, and optimize system behavior [

9,

10].

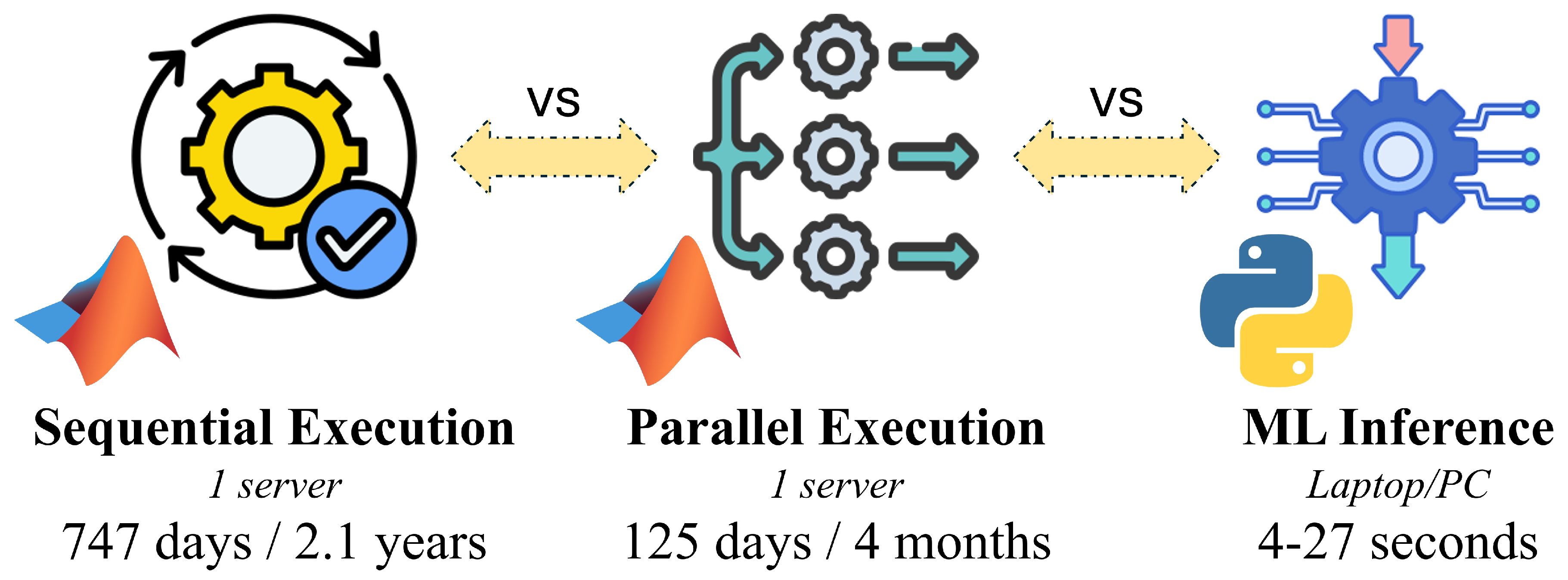

Despite their high fidelity, ray-tracing simulations suffer from two fundamental limitations. First, their computational cost grows rapidly with environmental complexity, carrier frequency, and the number of allowed reflections and diffractions, often requiring weeks or months of computation on powerful multi-core server infrastructures for exhaustive scenario exploration (see

Appendix C) [

6,

11]. Second, large-scale experimental validation of ray-tracing results is typically infeasible in real urban deployments, as acquiring comprehensive measurements across millions of transmitter–receiver combinations and diverse propagation conditions is prohibitively expensive and logistically impractical [

7,

8]. As a result, ray tracing should not be interpreted as a direct substitute for measurements, but rather as a digital twin mechanism that enables controlled exploration of propagation phenomena that cannot be directly observed at scale.

While ray-tracing-based digital twins offer valuable physical insight, there remains a lack of comprehensive studies providing statistical and system-level understanding of outdoor Wi-Fi propagation in realistic 3D urban environments. Existing Wi-Fi literature predominantly focuses on indoor scenarios or protocol-level optimizations, with comparatively fewer works addressing outdoor propagation behavior across multiple frequency bands under realistic geometric conditions [

1,

6]. This gap is particularly relevant for modern Wi-Fi systems operating in higher frequency bands, where propagation is more sensitive to obstructions and multipath complexity.

Recent advances in Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning provide a promising pathway to overcome the computational limitations of ray tracing. By learning directly from large ray-tracing-generated datasets, data-driven models can approximate complex propagation behavior with orders-of-magnitude lower computational cost at inference time [

1,

12,

13]. In particular, transformer-based architectures have demonstrated superior performance on structured and tabular data by modeling global feature dependencies through self-attention mechanisms [

14,

15]. In wireless communication research, attention-based models have shown strong potential for channel modeling and radio map generation, enabling fast and scalable prediction of spatial signal characteristics [

12,

13].

Motivated by these developments, this paper proposes a smart city–oriented digital twin framework for 3D outdoor Wi-Fi analysis that combines large-scale ray-tracing simulations with Transformer-based Machine Learning models. Using a detailed OSM-derived 3D (geographic) model of the Politehnica University of Timișoara campus and surrounding urban areas, we generate an extensive dataset capturing realistic outdoor Wi-Fi propagation across multiple frequencies, transmission powers, and propagation complexities (see

Appendix A). We further demonstrate that Transformer-based models can accurately learn the underlying ray-tracing behavior, enabling the generation of detailed Wi-Fi propagation estimates in seconds, what would otherwise require weeks or months of simulation time on high-performance computing infrastructure (such as that presented in

Appendix C).

The main contributions of this work are summarized as follows:

A comprehensive 3D outdoor Wi-Fi coverage analysis focused on smart city and campus-scale environments;

A ray-tracing-based digital twin framework for exploring propagation phenomena that are impractical to measure directly;

A large-scale dataset capturing millions of transmitter–receiver interactions across multiple frequencies and propagation conditions;

A transformer-based surrogate modeling approach that accurately approximates ray-tracing outputs with near-instantaneous inference;

A unified framework bridging physically grounded simulation and AI-driven acceleration for scalable wireless network planning.

3. Theoretical Foundation

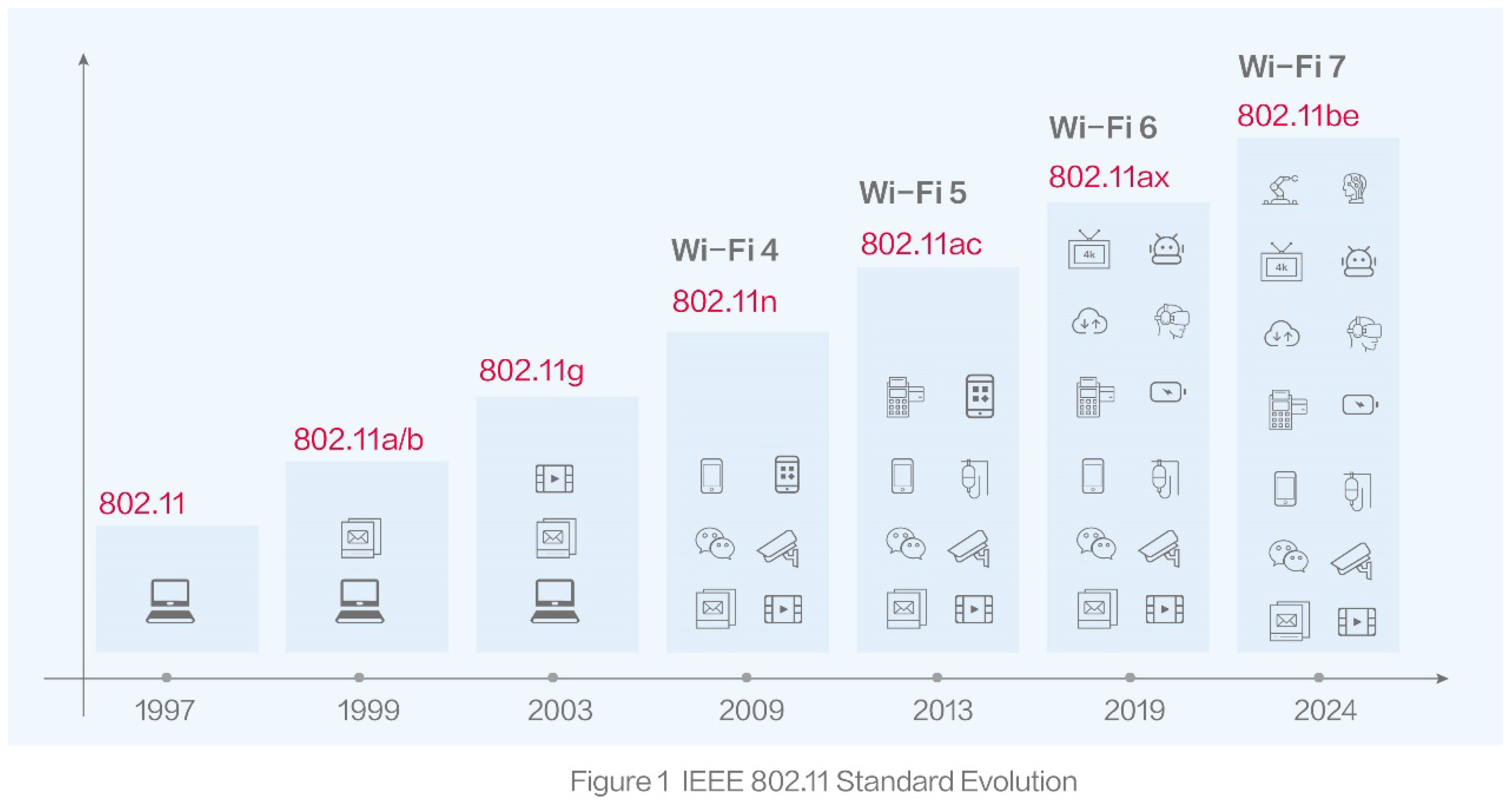

3.1. IEEE 802.11 Standard Evolution

The IEEE 802.11 standard, commonly known as Wi-Fi, has undergone significant evolution since its inception in 1997. Initially designed for basic wireless LAN communication, each new generation has improved spectral efficiency, throughput, latency, and support for modern applications.

Figure 2 summarizes the major milestones in Wi-Fi evolution.

802.11 / Wi-Fi 1 (1997): The original Wi-Fi standard, operating in the 2.4 GHz band, with speeds up to 2 Mbps.

802.11a/b / Wi-Fi 2 (1999): Introduced higher speeds (up to 54 Mbps) using OFDM in the 5 GHz band (802.11a), and a more cost-effective 11 Mbps 2.4 GHz option (802.11b).

802.11g / Wi-Fi 3 (2003): Combined the speed of 802.11a with the range and compatibility of 802.11b in the 2.4 GHz band.

802.11n / Wi-Fi 4 (2009): Added MIMO (multiple input, multiple output) antennas, channel bonding, and dual-band support for higher throughput and reliability.

802.11ac / Wi-Fi 5 (2013): Enhanced MIMO and introduced MU-MIMO and wider channels (up to 160 MHz), offering Gbps-level throughput.

802.11ax / Wi-Fi 6 (2019): Focused on high-density environments with OFDMA, uplink MU-MIMO, and target wake time (TWT) for better efficiency and power saving.

802.11be / Wi-Fi 7 (2024): Aims to deliver extremely high throughput (EHT) using 320 MHz channels, 4096-QAM modulation, and Multi-Link Operation (MLO), supporting demanding applications such as AR/VR, 8K streaming, and real-time cloud gaming.

The evolution of IEEE 802.11 standards reflects a growing need for higher bandwidth, lower latency, and better spectrum utilization, especially in high-density urban and indoor environments. Wi-Fi 6 and Wi-Fi 7 play a crucial role in enabling next-generation applications like industrial automation, wireless AI inference, and massive IoT deployments.

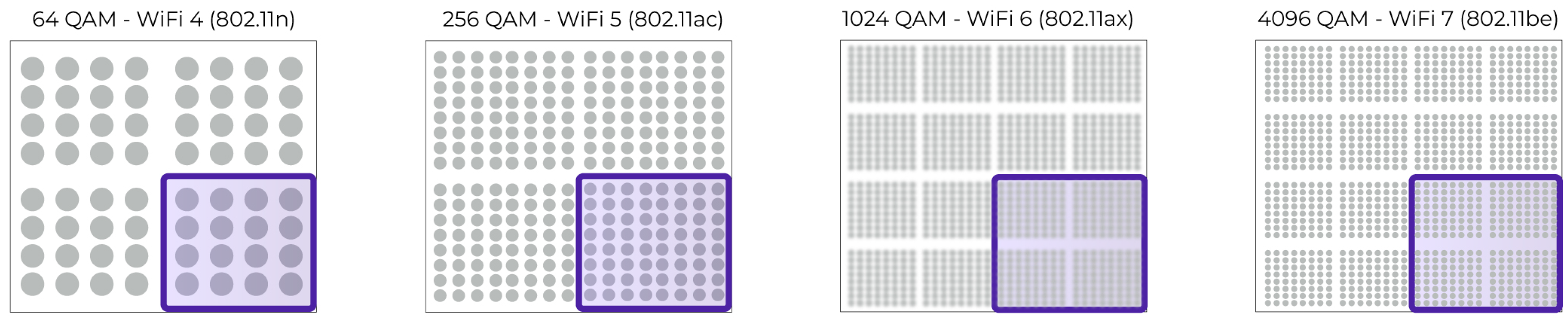

3.2. Advanced Modulation Schemes in Wi-Fi Standards

Modern Wi-Fi standards rely on advanced modulation techniques to increase spectral efficiency and boost data throughput. Quadrature Amplitude Modulation (QAM) allows a wireless signal to carry more bits per symbol by encoding both amplitude and phase information.

Wi-Fi 4 (802.11n) introduced support for up to 64-QAM, encoding 6 bits per symbol.

Wi-Fi 5 (802.11ac) expanded this to 256-QAM (8 bits/symbol).

Wi-Fi 6 (802.11ax) implemented 1024-QAM (10 bits/symbol), improving peak data rates by over 25%.

Wi-Fi 7 (802.11be) pushes the boundary further with 4096-QAM, encoding 12 bits per symbol.

While higher-order QAM schemes significantly increase capacity, they also demand:

Higher signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) at the receiver,

Precise channel estimation,

And minimal distortion from multipath effects.

As shown in

Figure 3, each increase in modulation order results in a denser constellation diagram, making it more sensitive to signal degradation caused by fading, interference, and environmental complexity. This directly motivates the need for accurate channel prediction techniques, particularly in Wi-Fi 7 environments, where the use of 4096-QAM imposes strict reliability constraints on signal quality.

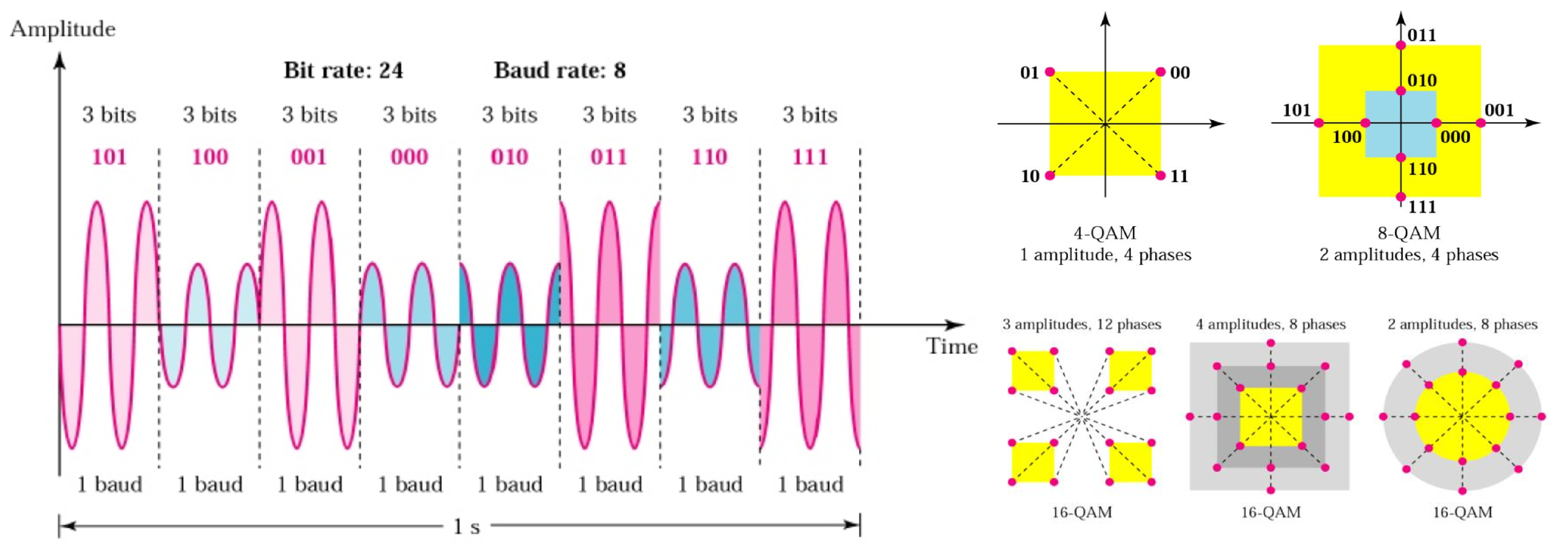

3.3. Modulation Principles and QAM Fundamentals

Quadrature Amplitude Modulation (QAM) is widely used in wireless communication standards, including Wi-Fi 6 and Wi-Fi 7, to increase data rates by encoding multiple bits per symbol. QAM modulates both the amplitude and the phase of a carrier wave, resulting in a two-dimensional constellation of unique symbols. Each symbol represents a distinct binary sequence, allowing more bits to be transmitted in each baud (symbol period).

The left side of

Figure 4 illustrates how a higher bit rate can be achieved by transmitting more bits per symbol at a fixed baud rate. The right side shows constellation diagrams for various QAM levels, highlighting the increasing symbol density and the corresponding need for higher signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) and more accurate channel prediction as modulation complexity increases.

Table 1 summarizes key characteristics of common QAM schemes used across Wi-Fi generations, including the required SNR under typical conditions and the bits carried per symbol.

3.4. Channels and Bandwidths in Wi-Fi Evolution

A foundational improvement in modern Wi-Fi standards lies in the expansion of available frequency bands and channel bandwidths. Wi-Fi signals are transmitted over defined channels, which occupy portions of the electromagnetic spectrum. The bandwidth of a channel (measured in MHz) determines how much data can be carried per transmission interval.

Earlier generations such as Wi-Fi 4 and Wi-Fi 5 supported 40 MHz and 80 MHz channel widths, respectively. Wi-Fi 6 expanded this to 160 MHz, significantly improving capacity and performance. The most recent advancement, Wi-Fi 7 (802.11be), introduces 320 MHz ultra-wide channels, allowing devices to transmit more data simultaneously and enabling maximum theoretical speeds of up to 46 Gbps, nearly five times that of Wi-Fi 6.

Figure 5 provides an intuitive visualization of this bandwidth evolution. Wider channels are metaphorically illustrated as multilane highways supporting faster vehicles, rockets for Wi-Fi 7, cars for Wi-Fi 6, bicycles for Wi-Fi 5, and pedestrians for Wi-Fi 4, reflecting increasing data transport capacity.

In addition to bandwidth, newer Wi-Fi standards take advantage of expanded frequency bands. Wi-Fi 4 and 5 primarily use the 2.4 GHz and 5 GHz bands, which are increasingly congested with legacy devices (e.g., Bluetooth, microwaves, older Wi-Fi). Wi-Fi 6E introduced the 6 GHz band, and Wi-Fi 7 fully exploits it, offering cleaner spectrum, minimal interference, and multiple contiguous 160 or 320 MHz channels for high-throughput, low-latency wireless communication. This combination of broader channels and cleaner spectrum is essential for next-generation applications such as AR/VR, cloud gaming, and wireless AI workloads.

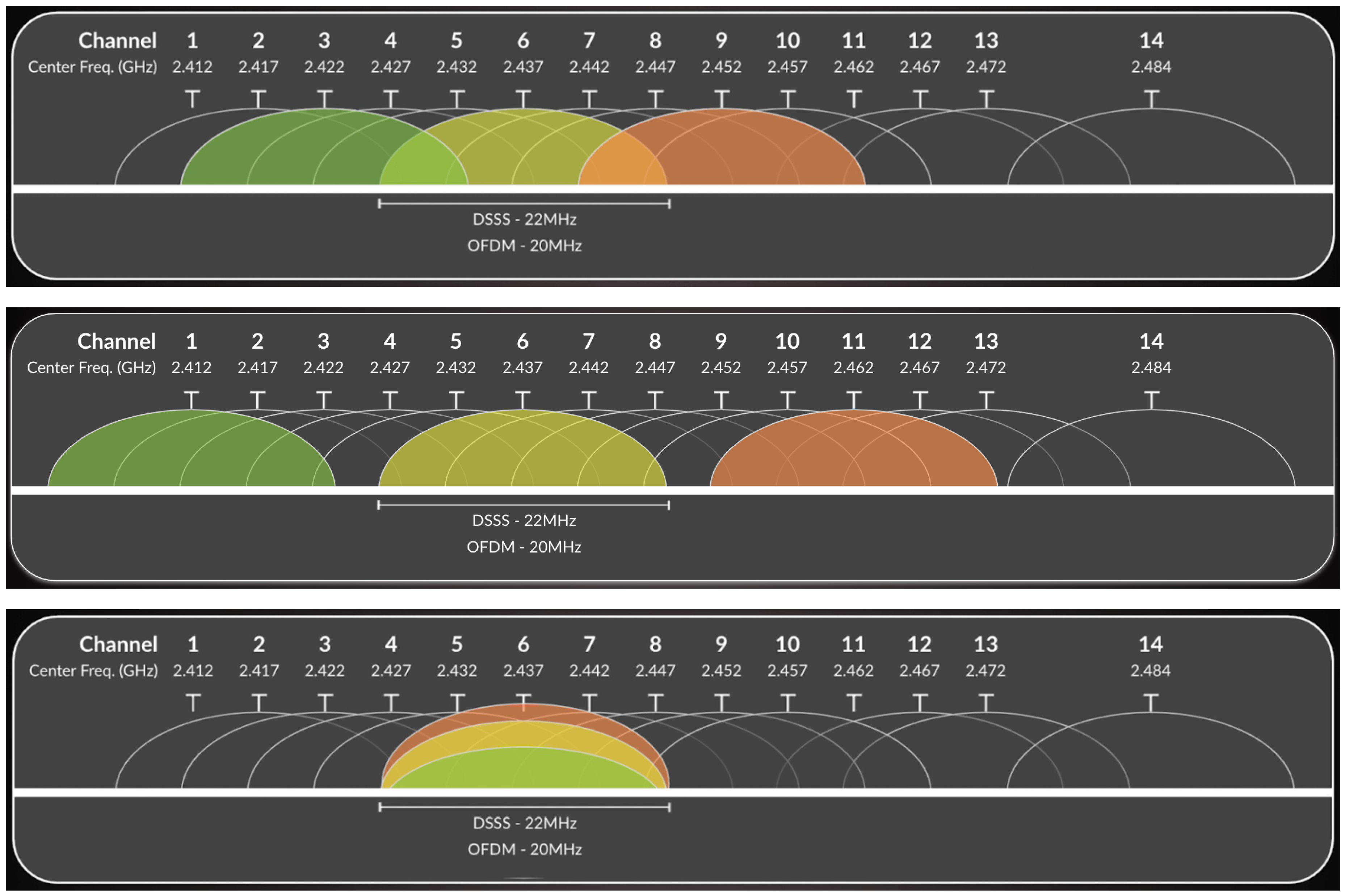

3.4.1. 2.4 GHz Wi-Fi Channels

The 2.4 GHz band represents the earliest and most widely deployed spectrum for Wi-Fi communications. In most regulatory domains, this band spans approximately 83.5 MHz, from 2.400 GHz to 2.4835 GHz, and is divided into 14 partially overlapping channels with center frequencies spaced 5 MHz apart. Despite the apparent availability of multiple channels, the effective usable spectrum is limited by the bandwidth requirements of Wi-Fi transmissions.

Traditional IEEE 802.11b systems employed direct-sequence spread spectrum (DSSS) with a channel bandwidth of approximately 22 MHz, while later standards such as IEEE 802.11g and IEEE 802.11n adopted orthogonal frequency-division multiplexing (OFDM) with an effective bandwidth of 20 MHz. As a consequence, adjacent channels in the 2.4 GHz band overlap significantly, leading to both adjacent-channel interference (ACI) and co-channel interference (CCI) when multiple access points operate in close proximity.

Figure 6 illustrates the channel structure of the 2.4 GHz band and highlights the overlap between neighboring channels. Due to this overlap, only a limited set of non-overlapping channels, typically channels 1, 6, and 11 in most regions, can be deployed simultaneously without causing severe interference. While co-channel interference can be partially mitigated through carrier sense multiple access with collision avoidance (CSMA/CA), adjacent-channel interference is particularly detrimental, as overlapping transmissions are not coordinated by the medium access protocol.

The high susceptibility of the 2.4 GHz band to interference significantly constrains network capacity and spatial reuse in dense deployments, especially in outdoor and campus-scale environments. As a result, performance in the 2.4 GHz band is often limited not by signal strength alone, but by interference dynamics arising from channel overlap and shared medium access.

3.4.2. 5 GHz Wi-Fi Channels

The expansion of Wi-Fi into the 5 GHz band significantly increased the amount of available spectrum compared to the 2.4 GHz ISM band, enabling a larger number of channels and wider channel bandwidths.

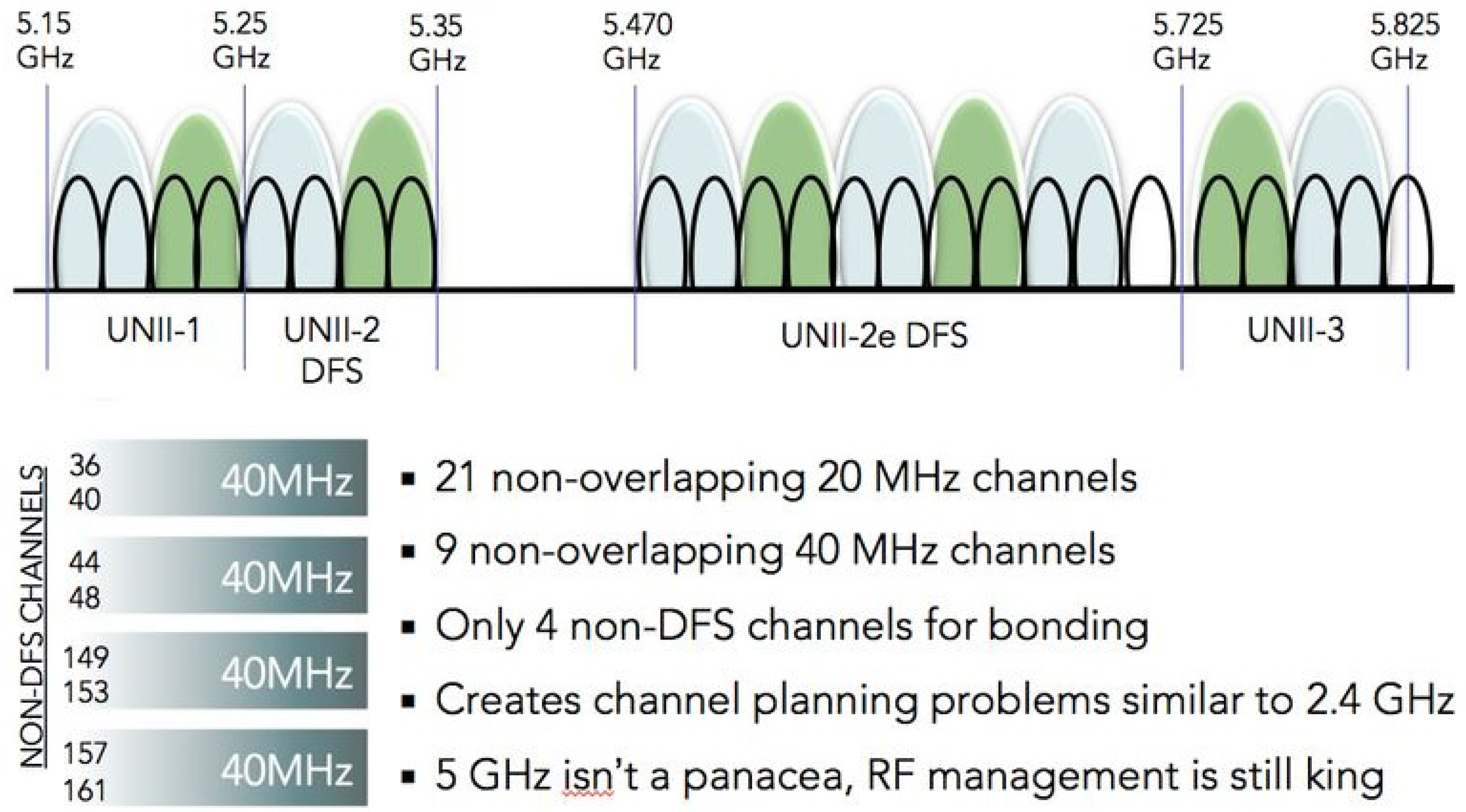

Figure 7 provides an overview of the 5 GHz Wi-Fi spectrum, illustrating channel allocation across the Unlicensed National Information Infrastructure (U-NII) sub-bands, including U-NII-1, U-NII-2, U-NII-2e, and U-NII-3, as well as the presence of Dynamic Frequency Selection (DFS)–regulated frequencies.

As shown in

Figure 7, the 5 GHz band supports a substantially higher number of non-overlapping channels for 20 MHz operation, which improves spatial reuse and reduces interference in dense deployments. Building on this increased spectral availability, channel bonding mechanisms introduced in IEEE 802.11n and extended in IEEE 802.11ac allow multiple adjacent channels to be combined, enabling bandwidths of 40 MHz, 80 MHz, and, in some configurations, 160 MHz.

However, the use of wider channels in the 5 GHz band introduces additional regulatory and operational constraints. A significant portion of the spectrum is subject to DFS requirements, which are intended to protect incumbent radar systems. Access points operating on DFS channels must perform channel availability checks and may be required to vacate channels upon radar detection, introducing delays and potential channel instability. As a result, despite the increased bandwidth compared to the 2.4 GHz band, effective channel availability in the 5 GHz band can be reduced in practice, particularly in outdoor and campus-scale deployments.

Overall, the 5 GHz band represents an important intermediate step in Wi-Fi evolution, alleviating many of the interference limitations of 2.4 GHz deployments while introducing new planning challenges related to regulatory constraints and channel bonding.

3.4.3. 6 GHz Wi-Fi Channels

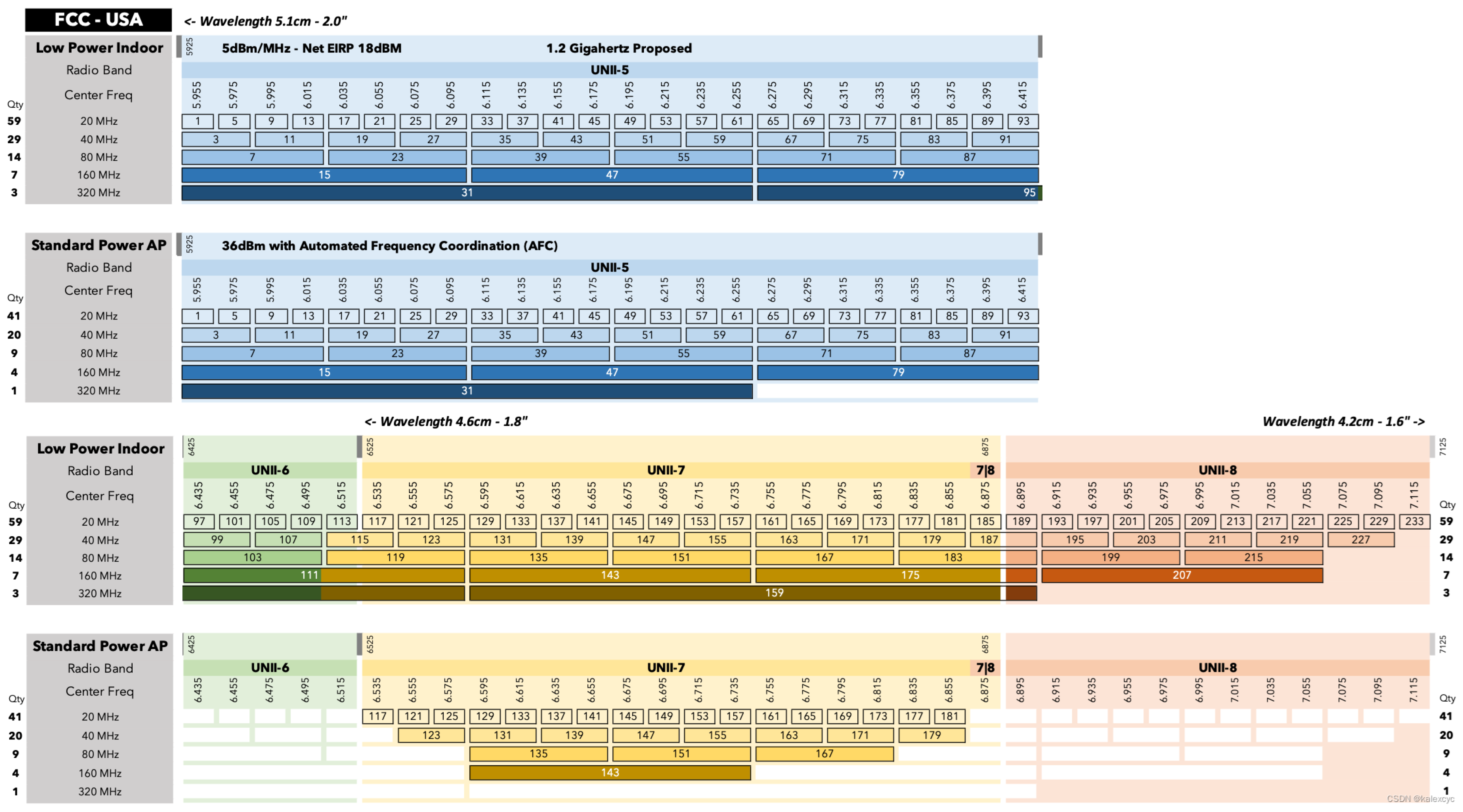

The opening of the 6 GHz band represents a major milestone in the evolution of Wi-Fi, providing a substantially larger and less congested spectrum compared to the legacy 2.4 GHz and 5 GHz bands. This spectrum expansion, introduced with Wi-Fi 6E and further extended in Wi-Fi 7, enables a dense and flexible channelization structure supporting both conventional and ultra-wide bandwidths.

Figure 8 illustrates the channel allocation of the 6 GHz band, including actual channel numbers, center frequencies, and permissible channel widths across the U-NII-5, U-NII-6, U-NII-7, and U-NII-8 sub-bands.

As shown in

Figure 8, the 6 GHz band supports a significantly larger number of non-overlapping 20 MHz channels, which can be aggregated to form wider channels of 40, 80, and 160 MHz without the extensive overlap constraints observed in lower-frequency bands. Most notably, the wide contiguous spectrum enables the use of 320 MHz channels, introduced with IEEE 802.11be (Wi-Fi 7), effectively doubling the maximum channel width supported by previous Wi-Fi generations.

The availability of such ultra-wide channels comes with important regulatory considerations. Depending on the region and deployment scenario, operation in the 6 GHz band may be restricted to low-power indoor (LPI) devices or may require automated frequency coordination (AFC) for standard-power access points. These constraints influence both channel availability and effective coverage, particularly in outdoor and campus-scale environments.

From a propagation perspective, the use of wider channels in the 6 GHz band shifts performance limitations away from spectral congestion toward environmental factors such as path loss, blockage, and multipath dispersion. While 320 MHz channels enable extremely high peak data rates, their practical performance is highly sensitive to three-dimensional urban geometry, reinforcing the need for accurate propagation modeling and data-driven digital twin approaches when analyzing next-generation Wi-Fi deployments.

3.5. Wireless Ray-Tracing

In wireless communication systems, the received power in a Line-of-Sight (LoS) scenario can be determined using the Friis transmission equation. This model provides a quantitative relationship between the transmitted power (

) and the received power (

), considering the impact of the propagation environment and antenna characteristics. The received power is given by

where

is the transmitted power,

is the signal wavelength,

is the transmitter–receiver separation, and

and

denote the transmitter and receiver antenna gains, respectively. The Friis model assumes free-space propagation with an unobstructed LoS path and therefore serves as a baseline for more complex propagation models.

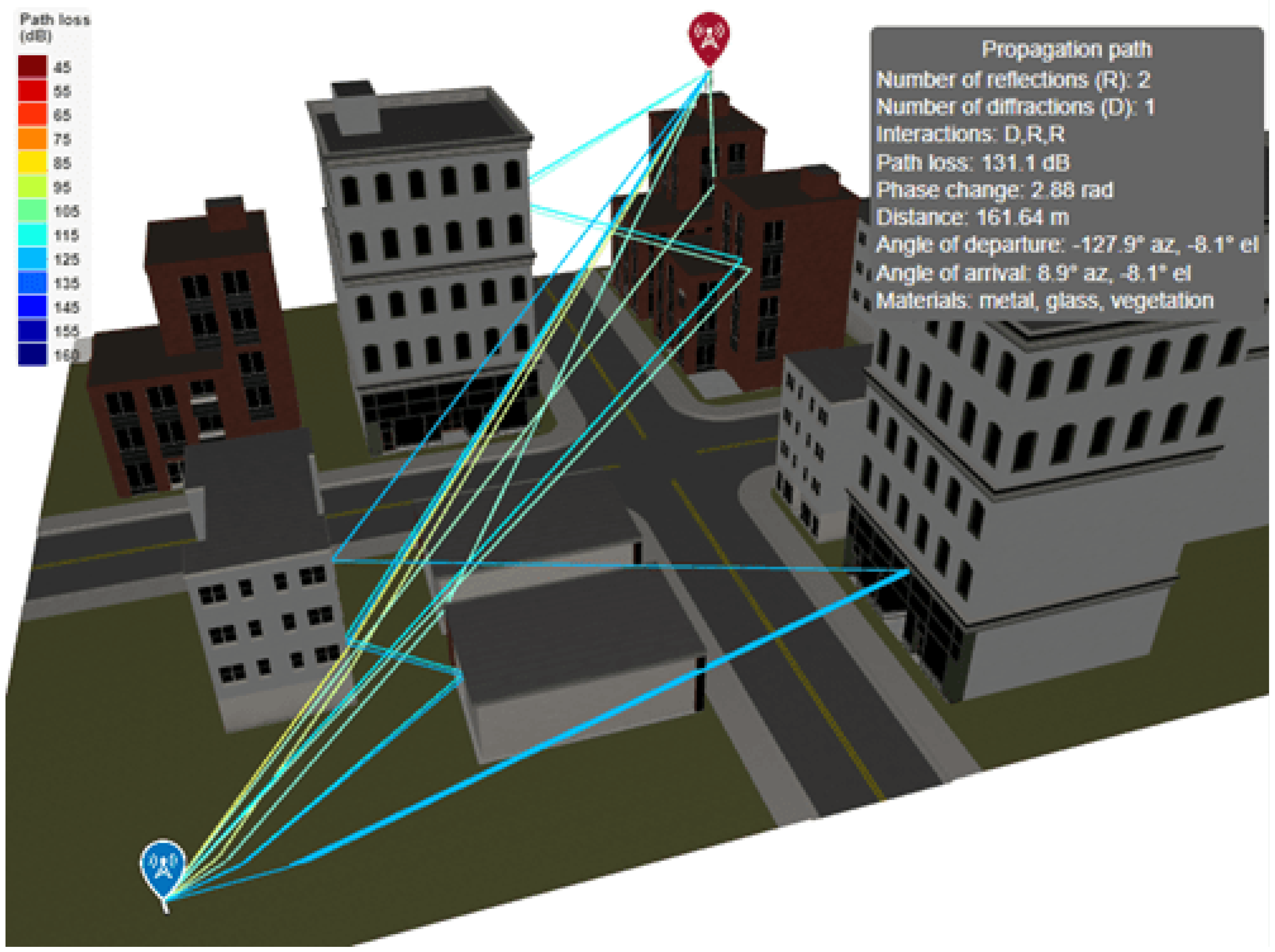

In realistic outdoor and urban environments, however, wireless propagation is strongly influenced by interactions between electromagnetic waves and surrounding objects such as buildings, terrain, and vegetation. Ray-tracing techniques extend the LoS model by explicitly accounting for multipath propagation mechanisms, including specular reflections, diffractions around edges, and, in some cases, scattering from rough surfaces. Each propagation path is modeled as a ray that undergoes successive interactions with the environment before reaching the receiver.

For reflected paths, the received power contribution of the

i-th ray can be expressed as

where

is the total propagation distance of the ray,

is the number of reflections encountered, and

denotes the Fresnel reflection coefficient at the

k-th interaction. The reflection coefficient depends on the angle of incidence, polarization, and electromagnetic properties of the reflecting surface, such as relative permittivity and conductivity.

Diffraction effects become significant when the direct path is partially or fully obstructed. In ray-tracing models, diffraction is commonly approximated using knife-edge or uniform theory of diffraction (UTD) formulations, which introduce an additional diffraction loss term. For a diffracted ray, the received power can be modeled as

where

D is the diffraction coefficient, which captures the attenuation caused by wave bending around obstacles and depends on the geometry of the diffracting edge and the wavelength.

The total received power at a given receiver location is obtained by coherently or incoherently summing the contributions of all valid rays, including the LoS component (if present), reflected rays, and diffracted rays. In practice, many ray-tracing implementations compute the received power as

where

denotes the number of propagation paths considered, limited by parameters such as the maximum number of reflections and diffractions allowed in the simulation.

By explicitly modeling these propagation mechanisms, ray tracing provides a physically grounded representation of wireless channels in complex three-dimensional environments. However, the computational complexity of evaluating a large number of rays and interactions grows rapidly with environmental detail and frequency, motivating the use of data-driven surrogate models to approximate ray-tracing outputs in large-scale digital twin simulations.

3.6. MATLAB Ray-Tracing Support

MATLAB provides built-in support for deterministic wireless ray-tracing through its RF Propagation and Antenna Toolboxes, enabling physically grounded modeling of radio propagation in complex three-dimensional environments. Based on geometrical optics (GO) and uniform theory of diffraction (UTD) principles, the ray-tracing framework explicitly models line-of-sight (LoS), reflected, and diffracted propagation paths between a transmitter and multiple receiver locations.

Figure 9 illustrates a representative ray-tracing scenario in an urban environment, where multiple propagation paths are generated between a transmitter and a receiver by accounting for reflections from building facades and diffraction around edges. Each ray corresponds to a distinct propagation path characterized by its total path length, number of reflections, number of diffractions, interaction materials, and geometric parameters such as angles of departure and arrival.

For each valid propagation path, MATLAB computes the associated path loss by combining free-space attenuation with interaction-specific losses introduced by reflections and diffractions. Reflections are modeled using Fresnel reflection coefficients derived from the electromagnetic properties of the interacting surfaces, such as relative permittivity and conductivity, while diffraction losses are calculated using UTD-based formulations. Material properties (e.g., concrete, glass, metal, vegetation) can be explicitly assigned to scene objects, allowing the ray-tracing model to capture environment-dependent attenuation effects.

In addition to path loss, MATLAB provides access to detailed per-ray metadata, including phase shifts, angles of arrival and departure, and interaction points. This information enables coherent or incoherent summation of multipath components at the receiver, as well as fine-grained analysis of multipath structure and angular dispersion. Simulation complexity is controlled through user-defined parameters such as the maximum number of reflections and diffractions considered, allowing a trade-off between physical accuracy and computational cost.

While MATLAB’s ray-tracing framework enables high-fidelity modeling of wireless propagation in realistic environments, the computational burden increases rapidly with scene complexity, frequency, and the number of allowed interactions. This limitation motivates the use of data-driven surrogate models capable of learning ray-tracing behavior from simulation data, enabling fast propagation prediction within large-scale digital twin environments.

3.7. Significance for Wi-Fi 7 Channel Prediction

The continuous evolution of IEEE 802.11 standards, culminating in the emergence of Wi-Fi 7 (802.11be), introduces unprecedented complexity in wireless channel behavior. With support for ultra-wide 320 MHz bandwidths, 4096-QAM modulation, multi-link operation (MLO), and low-latency scheduling, Wi-Fi 7 deployments demand highly accurate, real-time channel knowledge.

Traditional empirical or simplified propagation models may struggle to reflect the dynamic and high-resolution behavior of Wi-Fi 7 channels, especially in indoor or dense urban environments. Ray-tracing provides a physically accurate foundation for modeling such behavior, but remains computationally expensive and configuration-dependent.

To bridge this gap, our proposed method leverages supervised machine learning on ray-tracing-generated datasets to learn patterns in signal strength, path complexity, and interaction features. By doing so, we aim to develop a scalable and portable channel predictor that captures the frequency-, spatial-, and power-specific characteristics of Wi-Fi 7 environments without relying solely on repeated full-resolution simulations.

Thus, understanding the trajectory of IEEE 802.11 evolution is not just historical context, it is foundational for justifying the need for intelligent, data-driven wireless modeling in next-generation networks.

Figure 1.

Politehnica Timișoara University Campus with AP on top of Mechatronics (building O).

Figure 1.

Politehnica Timișoara University Campus with AP on top of Mechatronics (building O).

Figure 2.

Timeline of IEEE 802.11 standard evolution from 1997 to 2024, highlighting key technical milestones and application trends from 802.11 (Wi-Fi 1) to 802.11be (Wi-Fi 7). Source: Ruijie Networks.

Figure 2.

Timeline of IEEE 802.11 standard evolution from 1997 to 2024, highlighting key technical milestones and application trends from 802.11 (Wi-Fi 1) to 802.11be (Wi-Fi 7). Source: Ruijie Networks.

Figure 3.

Constellation diagrams illustrating modulation complexity in Wi-Fi standards. The number of distinct symbols increases exponentially from 64-QAM (Wi-Fi 4) to 4096-QAM (Wi-Fi 7), highlighting increased data rates and signal precision requirements. Source: Alta Inc.

Figure 3.

Constellation diagrams illustrating modulation complexity in Wi-Fi standards. The number of distinct symbols increases exponentially from 64-QAM (Wi-Fi 4) to 4096-QAM (Wi-Fi 7), highlighting increased data rates and signal precision requirements. Source: Alta Inc.

Figure 4.

Visualization of QAM modulation. Left: Time-domain example of mapping 3-bit symbols at a baud rate of 8 symbols/s for a bit rate of 24 bps. Right: Constellation diagrams for 4-QAM, 8-QAM, and 16-QAM, showing the increased complexity and tighter spacing of symbols with higher-order modulation.

Figure 4.

Visualization of QAM modulation. Left: Time-domain example of mapping 3-bit symbols at a baud rate of 8 symbols/s for a bit rate of 24 bps. Right: Constellation diagrams for 4-QAM, 8-QAM, and 16-QAM, showing the increased complexity and tighter spacing of symbols with higher-order modulation.

Figure 5.

Comparison of channel bandwidth and data capacity across Wi-Fi generations. Wi-Fi 7 enables 320 MHz channels and up to 46 Gbps throughput. Earlier versions like Wi-Fi 6 and 5 are limited by narrower bandwidths and more congested bands. Sources: ASUS, SoundDD.

Figure 5.

Comparison of channel bandwidth and data capacity across Wi-Fi generations. Wi-Fi 7 enables 320 MHz channels and up to 46 Gbps throughput. Earlier versions like Wi-Fi 6 and 5 are limited by narrower bandwidths and more congested bands. Sources: ASUS, SoundDD.

Figure 6.

Channel allocation and interference mechanisms in the 2.4 GHz Wi-Fi band for 20–22 MHz channels. From top to bottom, the figure illustrates adjacent-channel interference, extensive channel overlap caused by 5 MHz channel spacing, and co-channel interference when multiple access points operate on the same channel. Due to the limited available spectrum, only a small number of non-overlapping channels can be used simultaneously, which significantly constrains capacity and spatial reuse in dense deployments. Images adapted from Ekahau.

Figure 6.

Channel allocation and interference mechanisms in the 2.4 GHz Wi-Fi band for 20–22 MHz channels. From top to bottom, the figure illustrates adjacent-channel interference, extensive channel overlap caused by 5 MHz channel spacing, and co-channel interference when multiple access points operate on the same channel. Due to the limited available spectrum, only a small number of non-overlapping channels can be used simultaneously, which significantly constrains capacity and spatial reuse in dense deployments. Images adapted from Ekahau.

Figure 7.

Overview of the 5 GHz Wi-Fi spectrum illustrating channel allocation across the U-NII sub-bands, including DFS-regulated frequencies and available non-overlapping channels for 20 MHz and 40 MHz operation. The figure highlights the increased spectral availability compared to the 2.4 GHz band, as well as the practical constraints introduced by Dynamic Frequency Selection in certain portions of the spectrum. Image adapted from publicly available sources.

Figure 7.

Overview of the 5 GHz Wi-Fi spectrum illustrating channel allocation across the U-NII sub-bands, including DFS-regulated frequencies and available non-overlapping channels for 20 MHz and 40 MHz operation. The figure highlights the increased spectral availability compared to the 2.4 GHz band, as well as the practical constraints introduced by Dynamic Frequency Selection in certain portions of the spectrum. Image adapted from publicly available sources.

Figure 8.

Channel allocation of the 6 GHz Wi-Fi band illustrating 20, 40, 80, 160, and 320 MHz channel groupings across the U-NII-5, U-NII-6, U-NII-7, and U-NII-8 sub-bands. The figure highlights actual channel numbers, center frequencies, and regulatory distinctions between low-power indoor (LPI) and standard-power access point operation with automated frequency coordination (AFC). The expanded contiguous spectrum enables ultra-wide 320 MHz channels introduced with IEEE 802.11be (Wi-Fi 7), supporting extremely high-throughput outdoor and campus-scale deployments. Image adapted from publicly available regulatory and technical sources.

Figure 8.

Channel allocation of the 6 GHz Wi-Fi band illustrating 20, 40, 80, 160, and 320 MHz channel groupings across the U-NII-5, U-NII-6, U-NII-7, and U-NII-8 sub-bands. The figure highlights actual channel numbers, center frequencies, and regulatory distinctions between low-power indoor (LPI) and standard-power access point operation with automated frequency coordination (AFC). The expanded contiguous spectrum enables ultra-wide 320 MHz channels introduced with IEEE 802.11be (Wi-Fi 7), supporting extremely high-throughput outdoor and campus-scale deployments. Image adapted from publicly available regulatory and technical sources.

Figure 9.

Example of deterministic ray-tracing visualization in MATLAB showing multiple propagation paths between a transmitter and a receiver in a three-dimensional urban environment. Each ray is characterized by its number of reflections and diffractions, interaction materials, path length, phase change, and angular properties. Color coding indicates path loss (dB), highlighting the attenuation differences between LoS, reflected, and diffracted paths (source: Mathworks website).

Figure 9.

Example of deterministic ray-tracing visualization in MATLAB showing multiple propagation paths between a transmitter and a receiver in a three-dimensional urban environment. Each ray is characterized by its number of reflections and diffractions, interaction materials, path length, phase change, and angular properties. Color coding indicates path loss (dB), highlighting the attenuation differences between LoS, reflected, and diffracted paths (source: Mathworks website).

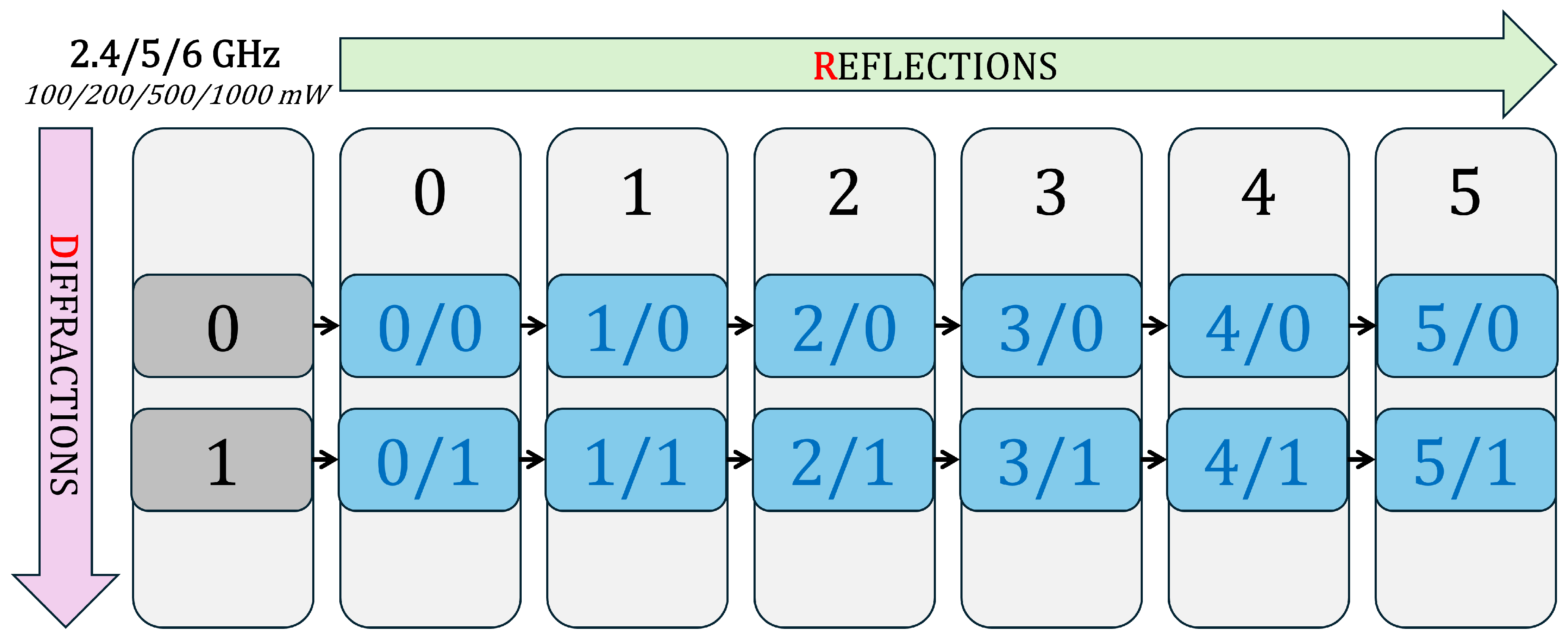

Figure 10.

Reflection–diffraction configuration matrix used in the MATLAB coverage map simulation. Each R/D cell corresponds to a unique propagation model setup that can be repeated across frequencies (2.4, 5, and 6 GHz) and transmit power levels (100, 200, 500, and 1000 mW).

Figure 10.

Reflection–diffraction configuration matrix used in the MATLAB coverage map simulation. Each R/D cell corresponds to a unique propagation model setup that can be repeated across frequencies (2.4, 5, and 6 GHz) and transmit power levels (100, 200, 500, and 1000 mW).

Figure 11.

3D radio coverage map generated in MATLAB’s siteviewer environment using the ray-tracing model (MaxNumReflections = 1, MaxNumDiffractions = 1) at 2.4 GHz, 0.1 W transmit power. The transmitter is positioned on top of the Mechatronics (building O) of the Politehnica University of Timișoara campus. The color scale indicates received power (dBm).

Figure 11.

3D radio coverage map generated in MATLAB’s siteviewer environment using the ray-tracing model (MaxNumReflections = 1, MaxNumDiffractions = 1) at 2.4 GHz, 0.1 W transmit power. The transmitter is positioned on top of the Mechatronics (building O) of the Politehnica University of Timișoara campus. The color scale indicates received power (dBm).

Figure 12.

Half-wave dipole antenna models and radiation behavior at 2.4 GHz, 5.0 GHz, and 6.0 GHz. Left: azimuthal directivity cut (near-omnidirectional in the horizontal plane). Center: 3D dipole geometry generated by MATLAB (design(dipole,f)). Right: 3D directivity distribution showing the expected toroidal pattern with nulls along the dipole axis.

Figure 12.

Half-wave dipole antenna models and radiation behavior at 2.4 GHz, 5.0 GHz, and 6.0 GHz. Left: azimuthal directivity cut (near-omnidirectional in the horizontal plane). Center: 3D dipole geometry generated by MATLAB (design(dipole,f)). Right: 3D directivity distribution showing the expected toroidal pattern with nulls along the dipole axis.

Figure 13.

Circular receiver array MATLAB visualization around a central transmitter (Electro building B, Polytechnic University Timișoara Campus). The receivers are evenly distributed along a circular perimeter, with coverage visualization shown both in 2D (left) and 3D (right).

Figure 13.

Circular receiver array MATLAB visualization around a central transmitter (Electro building B, Polytechnic University Timișoara Campus). The receivers are evenly distributed along a circular perimeter, with coverage visualization shown both in 2D (left) and 3D (right).

Figure 14.

Receiver site generation using a resolution-driven concentric-circle strategy. Multiple circles are placed around the transmitter with radial spacing , while the number of receivers per circle is computed from the circle circumference to maintain approximately meters spacing along the arc. Receivers are retained only if they fall inside the user-defined polygon footprint (campus area) and satisfy an optional elevation threshold; the inset emphasizes the dense sampling near the transmitter.

Figure 14.

Receiver site generation using a resolution-driven concentric-circle strategy. Multiple circles are placed around the transmitter with radial spacing , while the number of receivers per circle is computed from the circle circumference to maintain approximately meters spacing along the arc. Receivers are retained only if they fall inside the user-defined polygon footprint (campus area) and satisfy an optional elevation threshold; the inset emphasizes the dense sampling near the transmitter.

Figure 15.

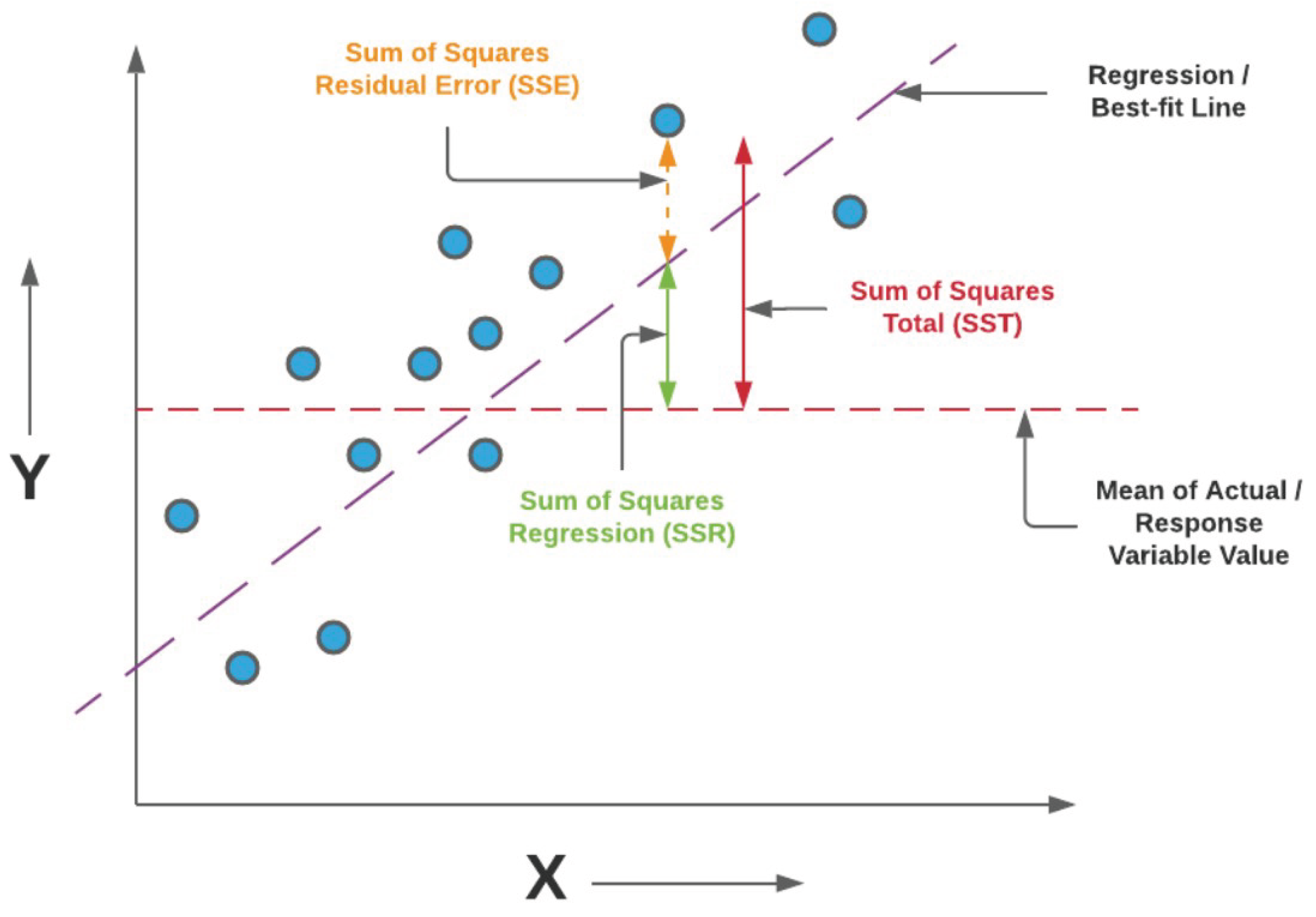

Illustration of the decomposition of variance in linear regression. The total sum of squares (SST) measures the variance of the observed data around the mean, the regression sum of squares (SSR) represents the variance explained by the model, and the sum of squared errors (SSE) captures the residual error. The coefficient of determination quantifies the ratio of explained variance to total variance (source: vitaflux.com).

Figure 15.

Illustration of the decomposition of variance in linear regression. The total sum of squares (SST) measures the variance of the observed data around the mean, the regression sum of squares (SSR) represents the variance explained by the model, and the sum of squared errors (SSE) captures the residual error. The coefficient of determination quantifies the ratio of explained variance to total variance (source: vitaflux.com).

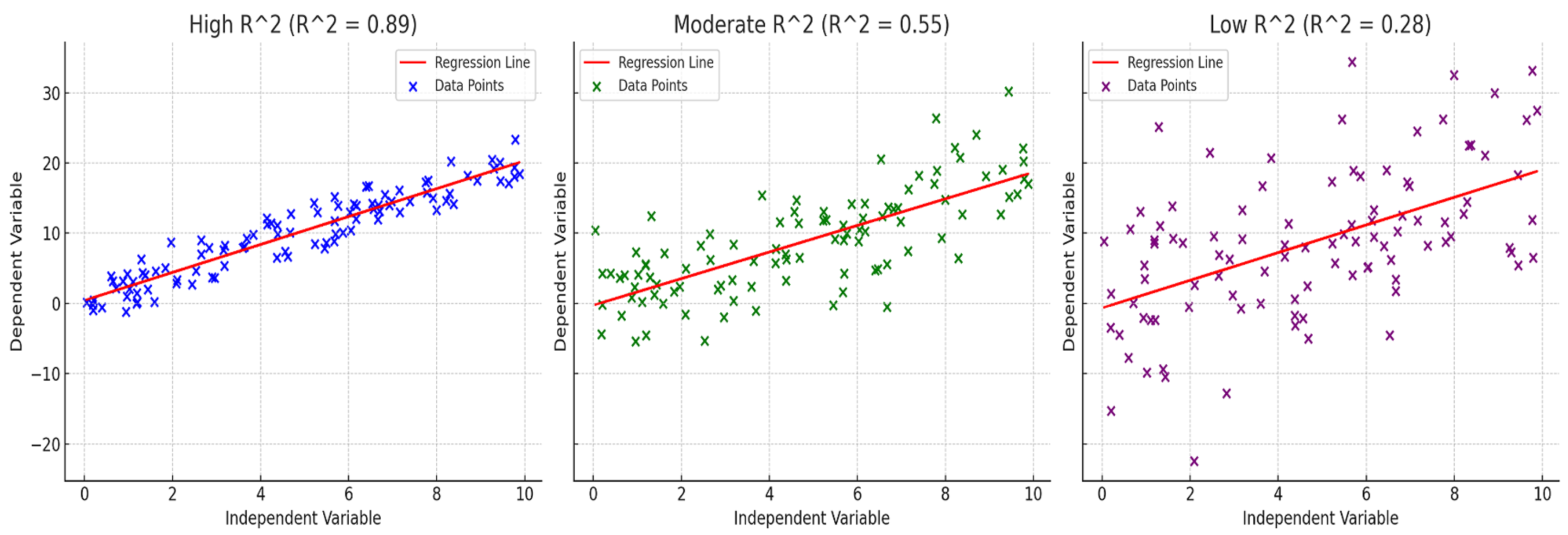

Figure 16.

Illustrative examples of regression performance for different values of the coefficient of determination . Left: High , where predictions closely follow the regression line and most variance is explained. Center: Moderate , indicating partial explanatory power with noticeable dispersion. Right: Low , where predictions exhibit weak alignment with observations and most variance remains unexplained (source: vitaflux.com).

Figure 16.

Illustrative examples of regression performance for different values of the coefficient of determination . Left: High , where predictions closely follow the regression line and most variance is explained. Center: Moderate , indicating partial explanatory power with noticeable dispersion. Right: Low , where predictions exhibit weak alignment with observations and most variance remains unexplained (source: vitaflux.com).

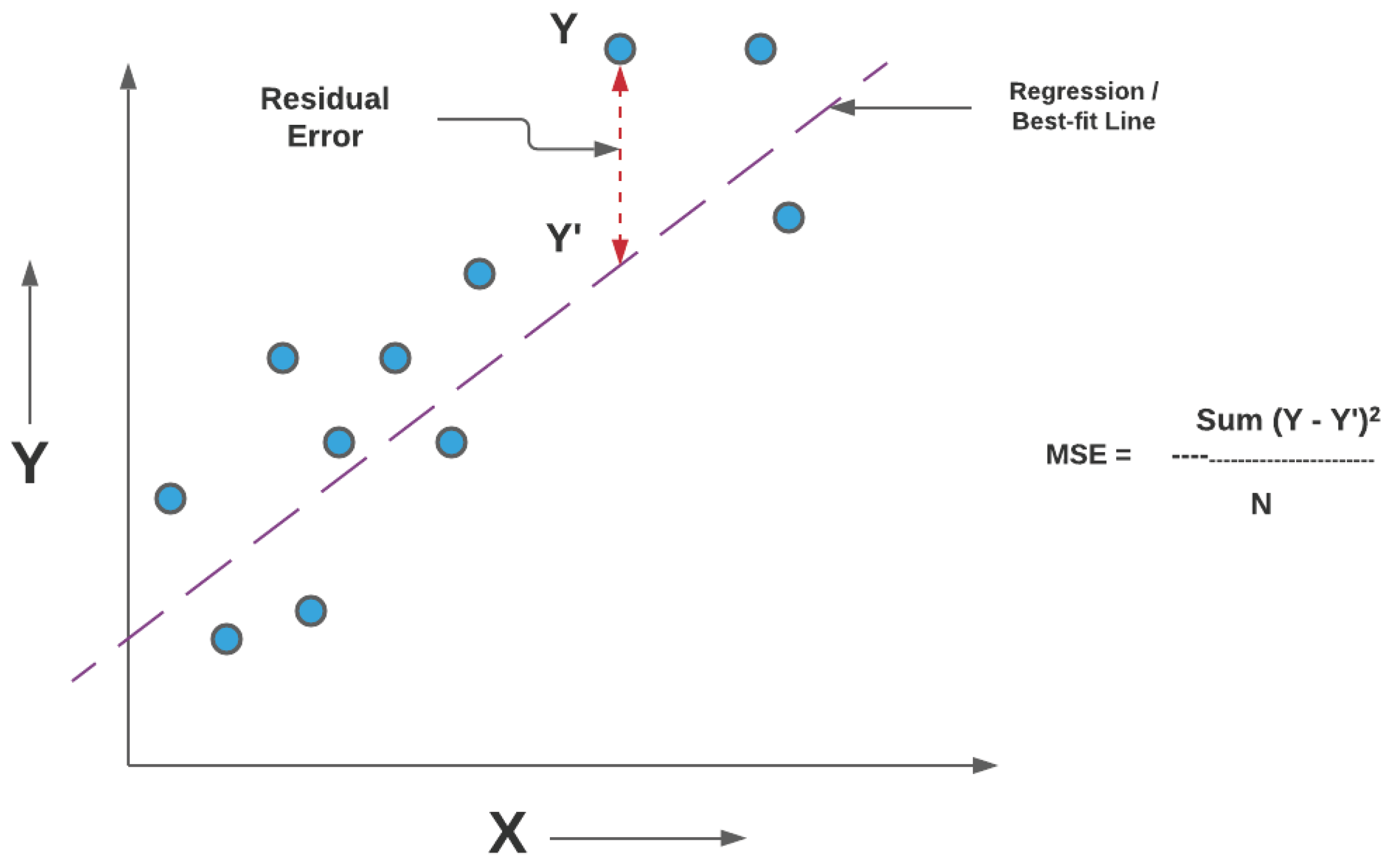

Figure 17.

Illustration of residual errors in a regression model and their contribution to the mean squared error (MSE), which forms the basis of the root mean squared error (RMSE).

Figure 17.

Illustration of residual errors in a regression model and their contribution to the mean squared error (MSE), which forms the basis of the root mean squared error (RMSE).

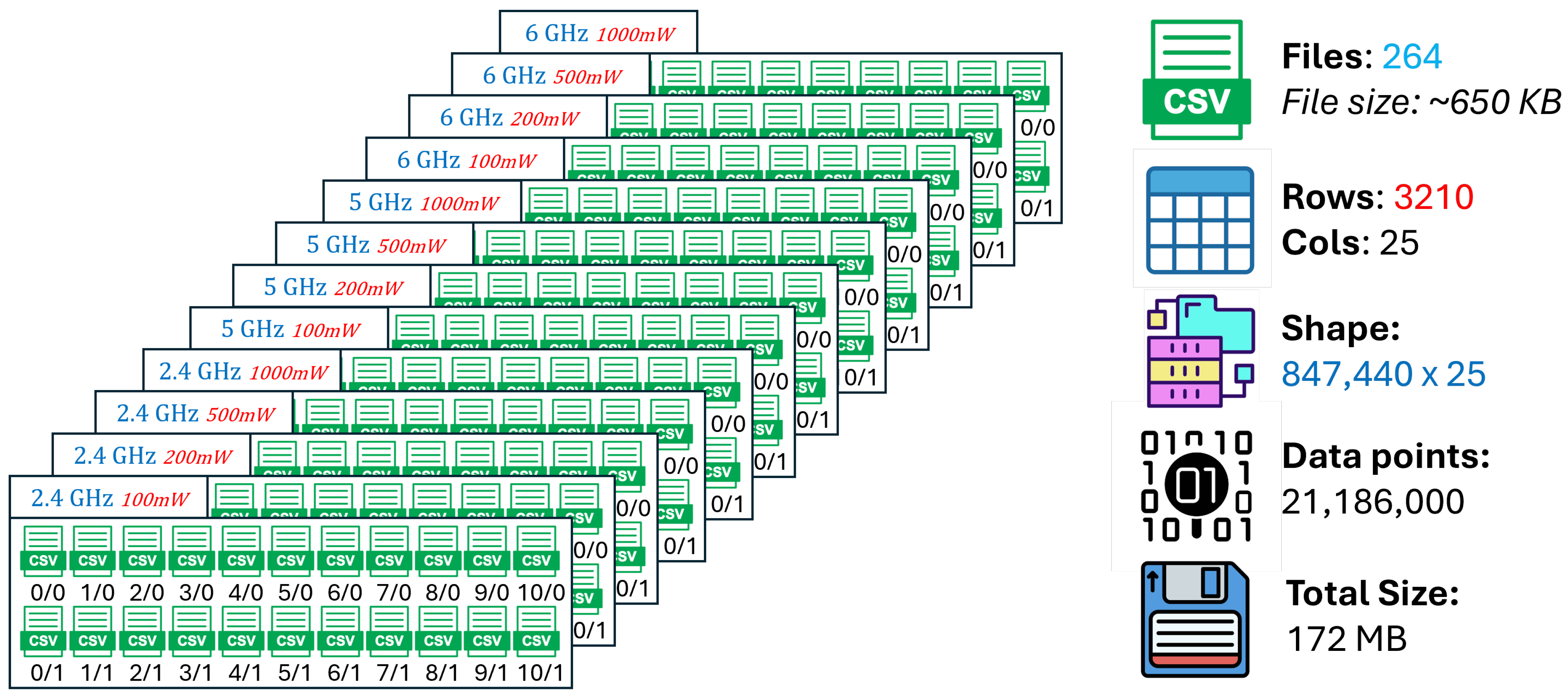

Figure 18.

Overview of the training dataset organization. Ray-tracing simulations are generated across three frequency bands (2.4, 5, and 6 GHz) and four transmit power levels (100, 200, 500, and 1000 mW). Each configuration produces multiple CSV files corresponding to different reflection–diffraction (R/D) settings, forming the complete training data corpus.

Figure 18.

Overview of the training dataset organization. Ray-tracing simulations are generated across three frequency bands (2.4, 5, and 6 GHz) and four transmit power levels (100, 200, 500, and 1000 mW). Each configuration produces multiple CSV files corresponding to different reflection–diffraction (R/D) settings, forming the complete training data corpus.

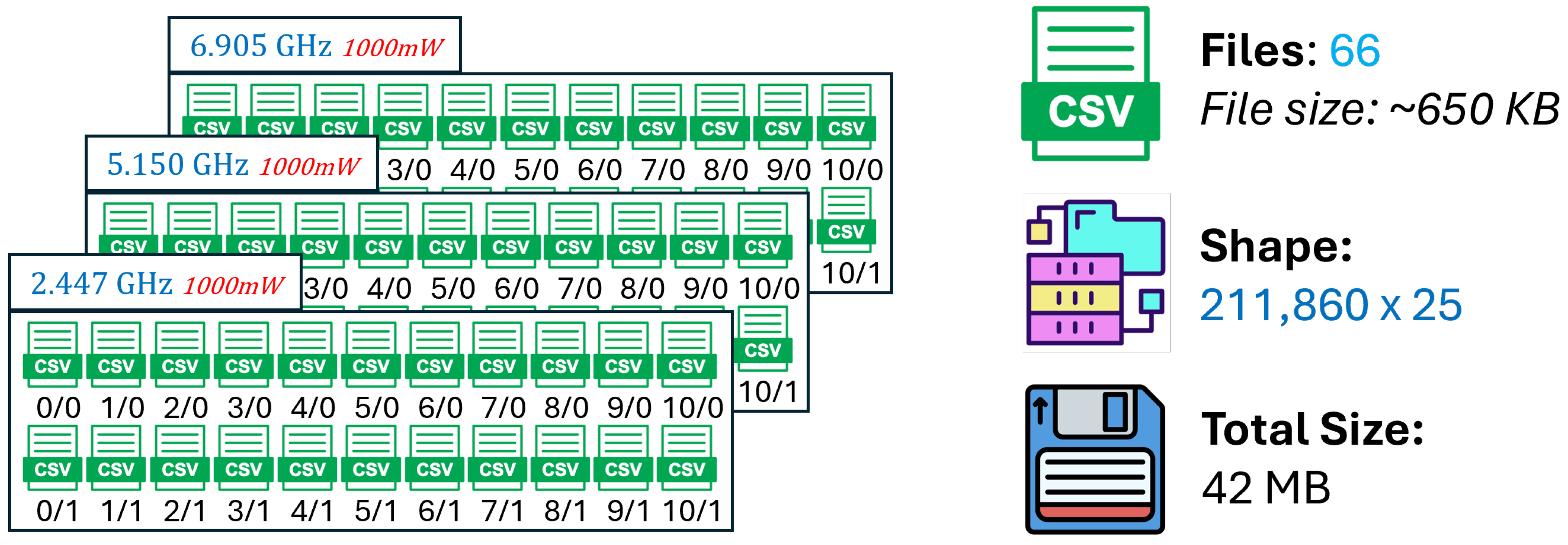

Figure 19.

Organization of the evaluation (validation) dataset. Ray-tracing simulations are generated for three representative channels at 2.4 GHz (2.447 GHz), 5 GHz (5.15 GHz), and 6 GHz (6.905 GHz), all at a fixed transmit power of 1000 mW. Each configuration includes multiple reflection–diffraction (R/D) settings, resulting in a structured set of CSV files used for validation.

Figure 19.

Organization of the evaluation (validation) dataset. Ray-tracing simulations are generated for three representative channels at 2.4 GHz (2.447 GHz), 5 GHz (5.15 GHz), and 6 GHz (6.905 GHz), all at a fixed transmit power of 1000 mW. Each configuration includes multiple reflection–diffraction (R/D) settings, resulting in a structured set of CSV files used for validation.

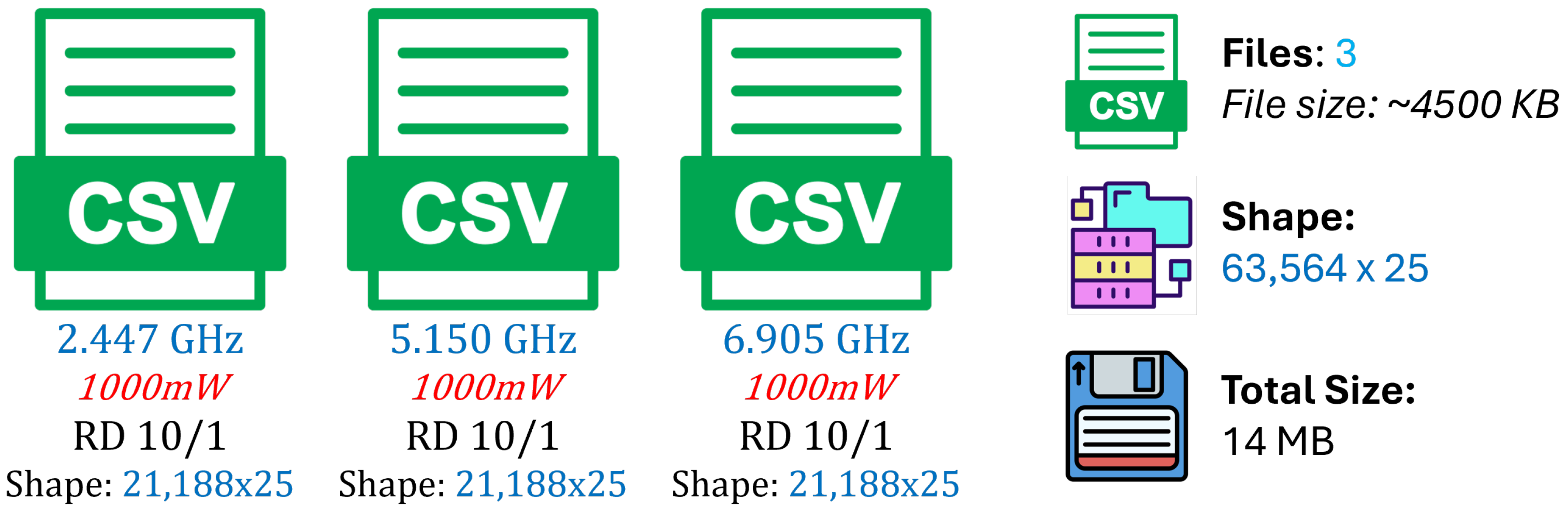

Figure 20.

Organization of the test dataset. High-resolution ray-tracing simulations are generated at 2.447 GHz, 5.15 GHz, and 6.905 GHz, all at a transmit power of 1000 mW, using a finer receiver spacing of 2 m. Each configuration produces a large CSV file containing dense spatial RSSI samples used to assess spatial generalization performance.

Figure 20.

Organization of the test dataset. High-resolution ray-tracing simulations are generated at 2.447 GHz, 5.15 GHz, and 6.905 GHz, all at a transmit power of 1000 mW, using a finer receiver spacing of 2 m. Each configuration produces a large CSV file containing dense spatial RSSI samples used to assess spatial generalization performance.

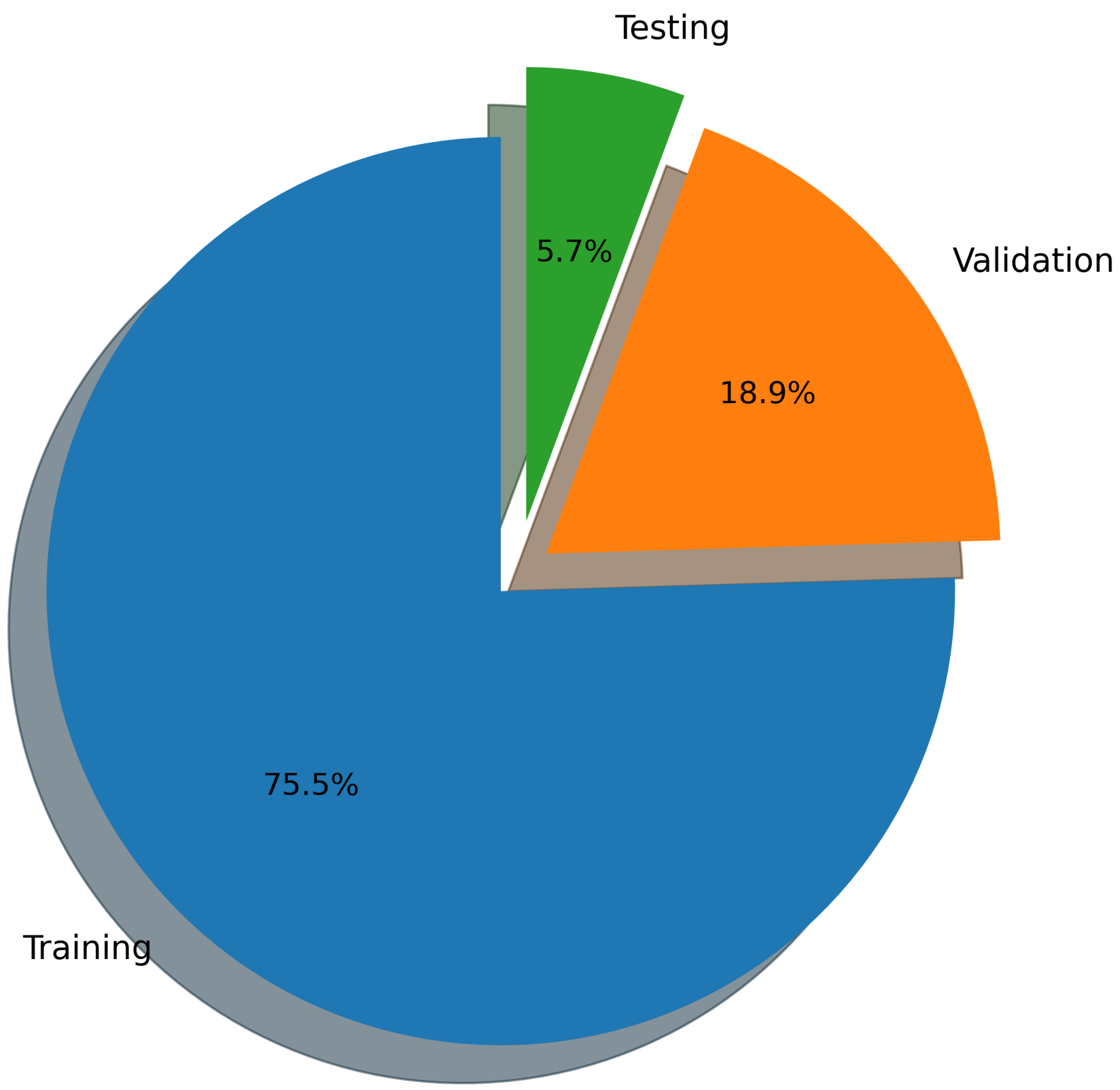

Figure 21.

Overall dataset composition showing the proportion of samples used for training (847,440), validation (211,860), and testing (63,564).

Figure 21.

Overall dataset composition showing the proportion of samples used for training (847,440), validation (211,860), and testing (63,564).

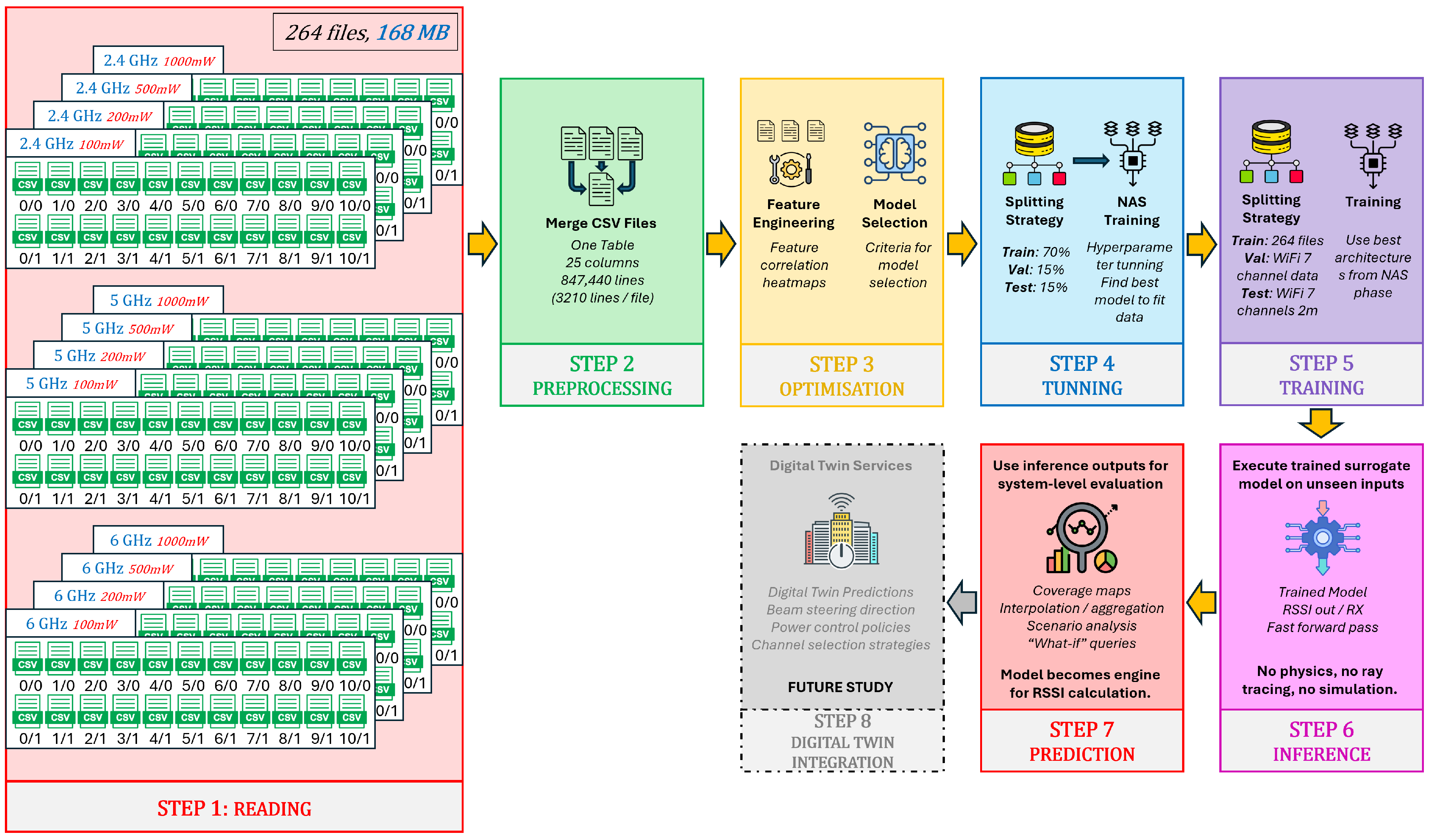

Figure 22.

End-to-end machine learning pipeline for RSSI surrogate modeling. The workflow spans from large-scale ray-tracing data ingestion and preprocessing (Steps 1–2), through feature engineering, model selection, and NAS-based tuning (Steps 3–4), to model training and fast inference (Steps 5–6). Prediction outputs are used for coverage analysis and system-level evaluation (Step 7), with a forward-looking integration into wireless digital twin services and network intelligence applications (Step 8).

Figure 22.

End-to-end machine learning pipeline for RSSI surrogate modeling. The workflow spans from large-scale ray-tracing data ingestion and preprocessing (Steps 1–2), through feature engineering, model selection, and NAS-based tuning (Steps 3–4), to model training and fast inference (Steps 5–6). Prediction outputs are used for coverage analysis and system-level evaluation (Step 7), with a forward-looking integration into wireless digital twin services and network intelligence applications (Step 8).

Figure 23.

Feature–target correlation heatmaps showing Pearson, Spearman, and Kendall correlation coefficients between ray-tracing-derived input features and the RSSI targets (RSSI1, RSSI2). Positive and negative correlations reflect physical propagation effects such as transmit power scaling, distance-dependent path loss, frequency-dependent attenuation, and multipath interactions.

Figure 23.

Feature–target correlation heatmaps showing Pearson, Spearman, and Kendall correlation coefficients between ray-tracing-derived input features and the RSSI targets (RSSI1, RSSI2). Positive and negative correlations reflect physical propagation effects such as transmit power scaling, distance-dependent path loss, frequency-dependent attenuation, and multipath interactions.

Figure 24.

Signal coverage maps for different ray-tracing configurations, RT 0/0 to RT 2/1, at 5 GHz with a transmission power of 100mW, showing the effects of reflections and diffractions on signal strength in an urban campus setting.

Figure 24.

Signal coverage maps for different ray-tracing configurations, RT 0/0 to RT 2/1, at 5 GHz with a transmission power of 100mW, showing the effects of reflections and diffractions on signal strength in an urban campus setting.

Figure 25.

RSSI versus Tx-Rx distance for 2.4, 5, and 6 GHz aggregated across RT 10/1 ray-tracing configurations and all transmit power levels (100, 200, 500, 1000 mW). Solid lines represent binned-median trends ( bins), and faded points correspond to downsampled individual measurements. Linear regression metrics are intentionally omitted due to the multipath-dominated nature of the dataset.

Figure 25.

RSSI versus Tx-Rx distance for 2.4, 5, and 6 GHz aggregated across RT 10/1 ray-tracing configurations and all transmit power levels (100, 200, 500, 1000 mW). Solid lines represent binned-median trends ( bins), and faded points correspond to downsampled individual measurements. Linear regression metrics are intentionally omitted due to the multipath-dominated nature of the dataset.

Figure 26.

RSSI as a function of the total number of reflections aggregated across all ray-tracing configurations, receiver locations, transmit power levels, and operating frequencies (2.4, 5, and 6 GHz). Light scatter points represent individual receiver samples, while solid curves indicate the median RSSI per reflection-count bin with interquartile range (IQR) error bars. The figure illustrates the systematic degradation of received signal strength with increasing multipath complexity and highlights frequency-dependent sensitivity to cumulative reflection losses.

Figure 26.

RSSI as a function of the total number of reflections aggregated across all ray-tracing configurations, receiver locations, transmit power levels, and operating frequencies (2.4, 5, and 6 GHz). Light scatter points represent individual receiver samples, while solid curves indicate the median RSSI per reflection-count bin with interquartile range (IQR) error bars. The figure illustrates the systematic degradation of received signal strength with increasing multipath complexity and highlights frequency-dependent sensitivity to cumulative reflection losses.

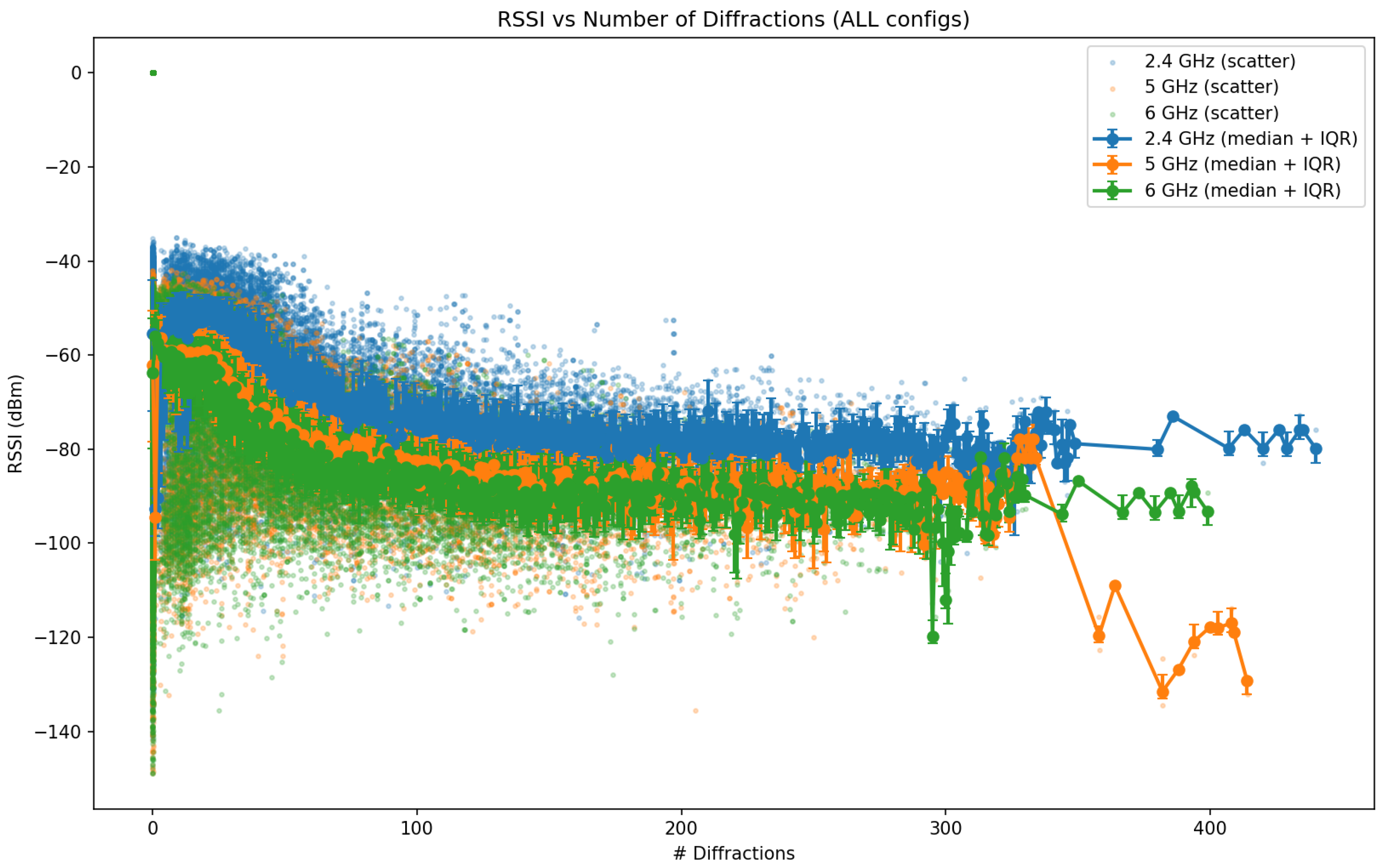

Figure 27.

RSSI versus total number of diffractions aggregated over all ray-tracing configurations and frequencies (2.4, 5, and 6 GHz). Scatter points represent individual samples, while solid curves show the median RSSI with interquartile ranges, highlighting the strong attenuation associated with diffraction-dominated propagation.

Figure 27.

RSSI versus total number of diffractions aggregated over all ray-tracing configurations and frequencies (2.4, 5, and 6 GHz). Scatter points represent individual samples, while solid curves show the median RSSI with interquartile ranges, highlighting the strong attenuation associated with diffraction-dominated propagation.

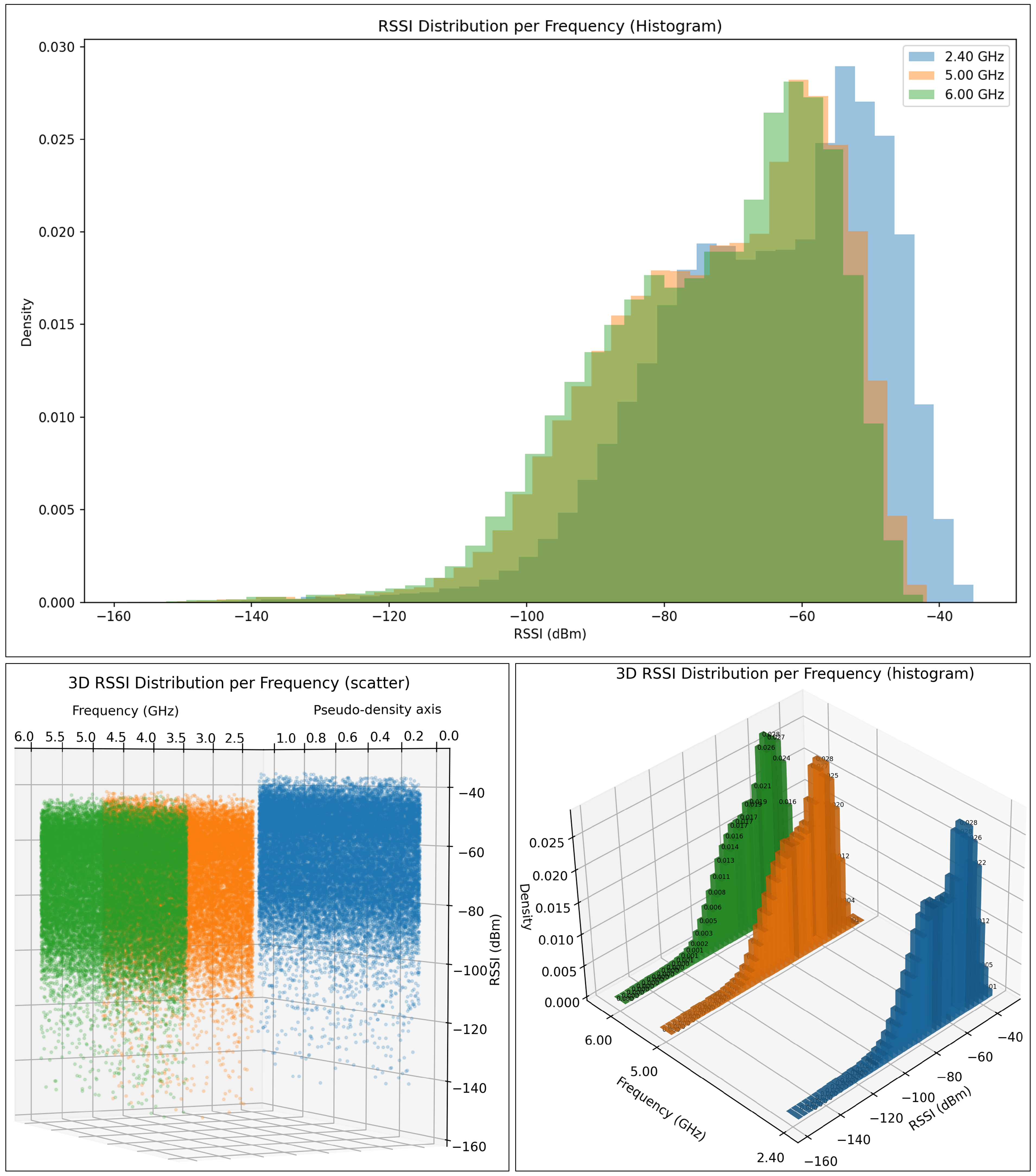

Figure 28.

RSSI distribution across the 2.4 GHz, 5 GHz, and 6 GHz Wi-Fi bands. The top panel shows the normalized 2D histogram of RSSI values, highlighting the central tendency and overlap between frequency bands under identical geometric and environmental conditions. The bottom-left panel presents a 3D scatter plot where each frequency band forms a distinct layer, illustrating the spread and density of individual measurements. The bottom-right panel shows the corresponding 3D histograms with semi-transparent bars to allow direct visual comparison of distribution shapes. Together, these views provide a comprehensive characterization of frequency-dependent signal behavior, revealing that 2.4 GHz yields the strongest and most concentrated RSSI distribution, while 5 GHz and 6 GHz exhibit progressively weaker and more dispersed signal characteristics due to increased attenuation and reduced diffraction efficiency at higher frequencies.

Figure 28.

RSSI distribution across the 2.4 GHz, 5 GHz, and 6 GHz Wi-Fi bands. The top panel shows the normalized 2D histogram of RSSI values, highlighting the central tendency and overlap between frequency bands under identical geometric and environmental conditions. The bottom-left panel presents a 3D scatter plot where each frequency band forms a distinct layer, illustrating the spread and density of individual measurements. The bottom-right panel shows the corresponding 3D histograms with semi-transparent bars to allow direct visual comparison of distribution shapes. Together, these views provide a comprehensive characterization of frequency-dependent signal behavior, revealing that 2.4 GHz yields the strongest and most concentrated RSSI distribution, while 5 GHz and 6 GHz exhibit progressively weaker and more dispersed signal characteristics due to increased attenuation and reduced diffraction efficiency at higher frequencies.

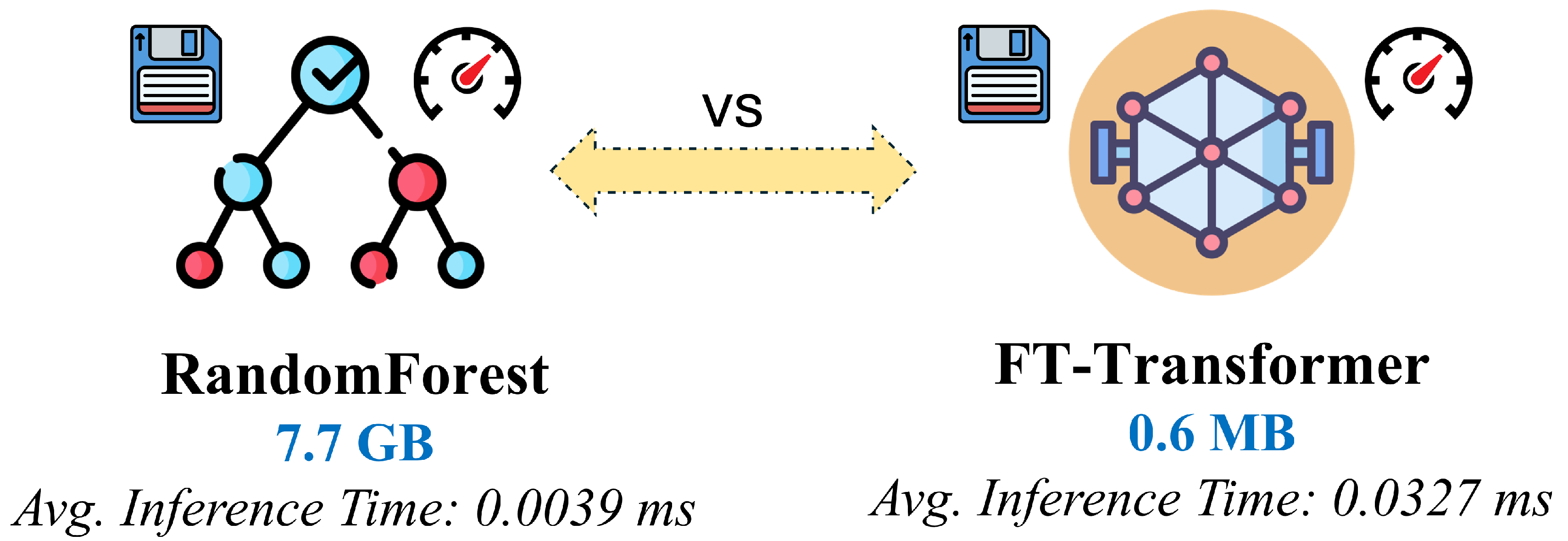

Figure 29.

Comparison of model size and average inference execution time for the RandomForest regressor and the FT-Transformer. The RandomForest model achieves faster per-target inference but requires significantly higher storage (7.7 GB), whereas the FT-Transformer offers a compact model footprint (0.6 MB) at the cost of higher per-target inference latency.

Figure 29.

Comparison of model size and average inference execution time for the RandomForest regressor and the FT-Transformer. The RandomForest model achieves faster per-target inference but requires significantly higher storage (7.7 GB), whereas the FT-Transformer offers a compact model footprint (0.6 MB) at the cost of higher per-target inference latency.

Figure 30.

Comparison between high-fidelity (offline computation, non-real-time simulations) MATLAB ray-tracing data generation and ML–based inference (online real-time computation). The left side illustrates the offline ray-tracing pipeline, where extensive parameter sweeps and multi-ray interactions require weeks/months of computation on dual-CPU servers. The right side highlights the trained FT-Transformer surrogate model, which enables near-instantaneous RSSI prediction through fast forward passes, allowing large-scale coverage analysis and scenario exploration in seconds rather than months.

Figure 30.

Comparison between high-fidelity (offline computation, non-real-time simulations) MATLAB ray-tracing data generation and ML–based inference (online real-time computation). The left side illustrates the offline ray-tracing pipeline, where extensive parameter sweeps and multi-ray interactions require weeks/months of computation on dual-CPU servers. The right side highlights the trained FT-Transformer surrogate model, which enables near-instantaneous RSSI prediction through fast forward passes, allowing large-scale coverage analysis and scenario exploration in seconds rather than months.

Figure 31.

High-resolution 3D model of the Politehnica University of Timișoara campus, obtained from architectural and LiDAR-based reconstructions. The model includes detailed building geometry and vegetation, enabling more realistic ray-tracing simulations for future studies.

Figure 31.

High-resolution 3D model of the Politehnica University of Timișoara campus, obtained from architectural and LiDAR-based reconstructions. The model includes detailed building geometry and vegetation, enabling more realistic ray-tracing simulations for future studies.

Table 1.

Comparison of QAM Modulation Schemes Used in Wi-Fi Standards

Table 1.

Comparison of QAM Modulation Schemes Used in Wi-Fi Standards

| QAM Order |

Bits per Symbol |

Approx. Required SNR |

Wi-Fi Standard(s) |

| 4-QAM (QPSK) |

2 |

9 dB |

Wi-Fi 1, fallback mode |

| 16-QAM |

4 |

16 dB |

Wi-Fi 2–7 |

| 64-QAM |

6 |

24 dB |

Wi-Fi 4 (802.11n) |

| 256-QAM |

8 |

30 dB |

Wi-Fi 5 (802.11ac) |

| 1024-QAM |

10 |

35 dB |

Wi-Fi 6 (802.11ax) |

| 4096-QAM |

12 |

41–43 dB |

Wi-Fi 7 (802.11be) |

Table 2.

Statistical summary of RSSI distributions (in dBm) for the 2.4 GHz, 5 GHz, and 6 GHz Wi-Fi bands across all ray-tracing configurations.

Table 2.

Statistical summary of RSSI distributions (in dBm) for the 2.4 GHz, 5 GHz, and 6 GHz Wi-Fi bands across all ray-tracing configurations.

| Frequency [GHz] |

Count |

Mean |

Median |

Std |

Min |

P5 |

P25 |

P75 |

P95 |

Max |

IQR |

| 2.4 |

1,076,698 |

-65.05 |

-62.82 |

16.06 |

-150.12 |

-92.96 |

-75.96 |

-52.16 |

-43.93 |

-35.06 |

23.80 |

| 5.0 |

1,081,920 |

-72.00 |

-69.47 |

16.37 |

-156.58 |

-100.42 |

-83.31 |

-58.79 |

-50.42 |

-41.84 |

24.52 |

| 6.0 |

1,049,220 |

-73.34 |

-70.56 |

16.48 |

-158.17 |

-102.25 |

-84.65 |

-60.13 |

-51.88 |

-42.40 |

24.52 |

Table 3.

FT-Transformer RSSI [dBm] results over five independent runs. Metrics reported per split; bottom rows show mean and standard deviation across runs.

Table 3.

FT-Transformer RSSI [dBm] results over five independent runs. Metrics reported per split; bottom rows show mean and standard deviation across runs.

| Run |

|

|

|

MAE [dBm] |

RMSE [dBm] |

MAE [dBm] |

RMSE [dBm] |

MAE [dBm] |

RMSE [dBm] |

| 1 |

0.9971 |

0.9962 |

0.9962 |

0.9536 |

1.4632 |

1.0510 |

1.6675 |

1.0502 |

1.6670 |

| 2 |

0.9967 |

0.9958 |

0.9958 |

1.0158 |

1.5602 |

1.1067 |

1.7559 |

1.1093 |

1.7494 |

| 3 |

0.9969 |

0.9960 |

0.9960 |

0.9936 |

1.5124 |

1.0872 |

1.7178 |

1.0858 |

1.7153 |

| 4 |

0.9976 |

0.9968 |

0.9968 |

0.8735 |

1.3382 |

0.9579 |

1.5333 |

0.9576 |

1.5252 |

| 5 |

0.9974 |

0.9966 |

0.9967 |

0.9045 |

1.3849 |

0.9908 |

1.5795 |

0.9903 |

1.5654 |

| Mean |

0.9971 |

0.9963 |

0.9963 |

0.9482 |

1.4518 |

1.0387 |

1.6508 |

1.0386 |

1.6445 |

| Std |

0.00036 |

0.00041 |

0.00044 |

0.05948 |

0.09074 |

0.06315 |

0.09314 |

0.06375 |

0.09619 |

Table 4.

RandomForestRegressor RSSI [dBm] results over five independent runs. Metrics reported per split; bottom rows show mean and standard deviation across runs.

Table 4.

RandomForestRegressor RSSI [dBm] results over five independent runs. Metrics reported per split; bottom rows show mean and standard deviation across runs.

| Run |

|

|

|

MAE [dBm] |

RMSE [dBm] |

MAE [dBm] |

RMSE [dBm] |

MAE [dBm] |

RMSE [dBm] |

| 1 |

0.9993 |

0.9947 |

0.9947 |

0.3329 |

0.7318 |

0.9017 |

1.9685 |

0.8946 |

1.9625 |

| 2 |

0.9993 |

0.9947 |

0.9946 |

0.3337 |

0.7332 |

0.9029 |

1.9695 |

0.8975 |

1.9676 |

| 3 |

0.9993 |

0.9947 |

0.9946 |

0.3334 |

0.7331 |

0.9017 |

1.9669 |

0.8969 |

1.9681 |

| 4 |

0.9993 |

0.9947 |

0.9947 |

0.3326 |

0.7316 |

0.9011 |

1.9676 |

0.8952 |

1.9624 |

| 5 |

0.9993 |

0.9947 |

0.9946 |

0.3334 |

0.7335 |

0.9019 |

1.9683 |

0.8956 |

1.9669 |

| Mean |

0.9993 |

0.9947 |

0.9946 |

0.3334 |

0.7331 |

0.9017 |

1.9683 |

0.8956 |

1.9669 |

| Std |

0.00000 |

0.00000 |

0.00005 |

0.00044 |

0.00087 |

0.00065 |

0.00098 |

0.00121 |

0.00282 |

Table 5.

Comparison of FT-Transformer and RandomForestRegressor on RSSI [dBm] prediction. Values shown are mean ± standard deviation over five independent runs.

Table 5.

Comparison of FT-Transformer and RandomForestRegressor on RSSI [dBm] prediction. Values shown are mean ± standard deviation over five independent runs.

| Model |

|

|

|

MAE

|

RMSE

|

MAE

|

RMSE

|

MAE

|

RMSE

|

| FT-Transformer |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| RF-Regressor |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Table 6.

FT-Transformer fine-tuning results for RSSI prediction [dBm] over five independent runs using a fixed file-based split.

Table 6.

FT-Transformer fine-tuning results for RSSI prediction [dBm] over five independent runs using a fixed file-based split.

| Run |

|

|

|

MAE

|

RMSE

|

MAE

|

RMSE

|

MAE

|

RMSE

|

| Run #1 |

0.9955 |

0.9532 |

0.8003 |

1.1605 |

1.7763 |

3.5178 |

5.3811 |

4.7906 |

6.5370 |

| Run #2 |

0.9953 |

0.9536 |

0.8041 |

1.1860 |

1.8130 |

3.4920 |

5.3570 |

4.7410 |

6.4750 |

| Run #3 |

0.9968 |

0.9559 |

0.8103 |

0.9734 |

1.5080 |

3.3892 |

5.2230 |

4.6377 |

6.3727 |

| Run #4 |

0.9955 |

0.9532 |

0.8003 |

1.6052 |

1.7763 |

3.5178 |

5.3811 |

4.7906 |

6.5371 |

| Run #5 |

0.9954 |

0.9564 |

0.8074 |

1.1646 |

1.7955 |

3.3962 |

5.1931 |

4.7101 |

6.4201 |

| Avg |

0.9955 |

0.9536 |

0.8041 |

1.1646 |

1.7763 |

3.4920 |

5.3570 |

4.7410 |

6.4750 |

| Std |

0.00062 |

0.00156 |

0.00440 |

0.23288 |

0.12716 |

0.06472 |

0.09153 |

0.06384 |

0.07239 |