Submitted:

31 December 2025

Posted:

02 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Adsorbate

2.2. SBCT Preparation

2.3. Adsorbent Characterisation

2.4. Batch Adsorption of PFOA

2.5. Isotherm Modeling of Adsorption

2.6. Kinetic Modeling of Adsorption

2.7. Thermodynamic Studies

3. Results and Discussion

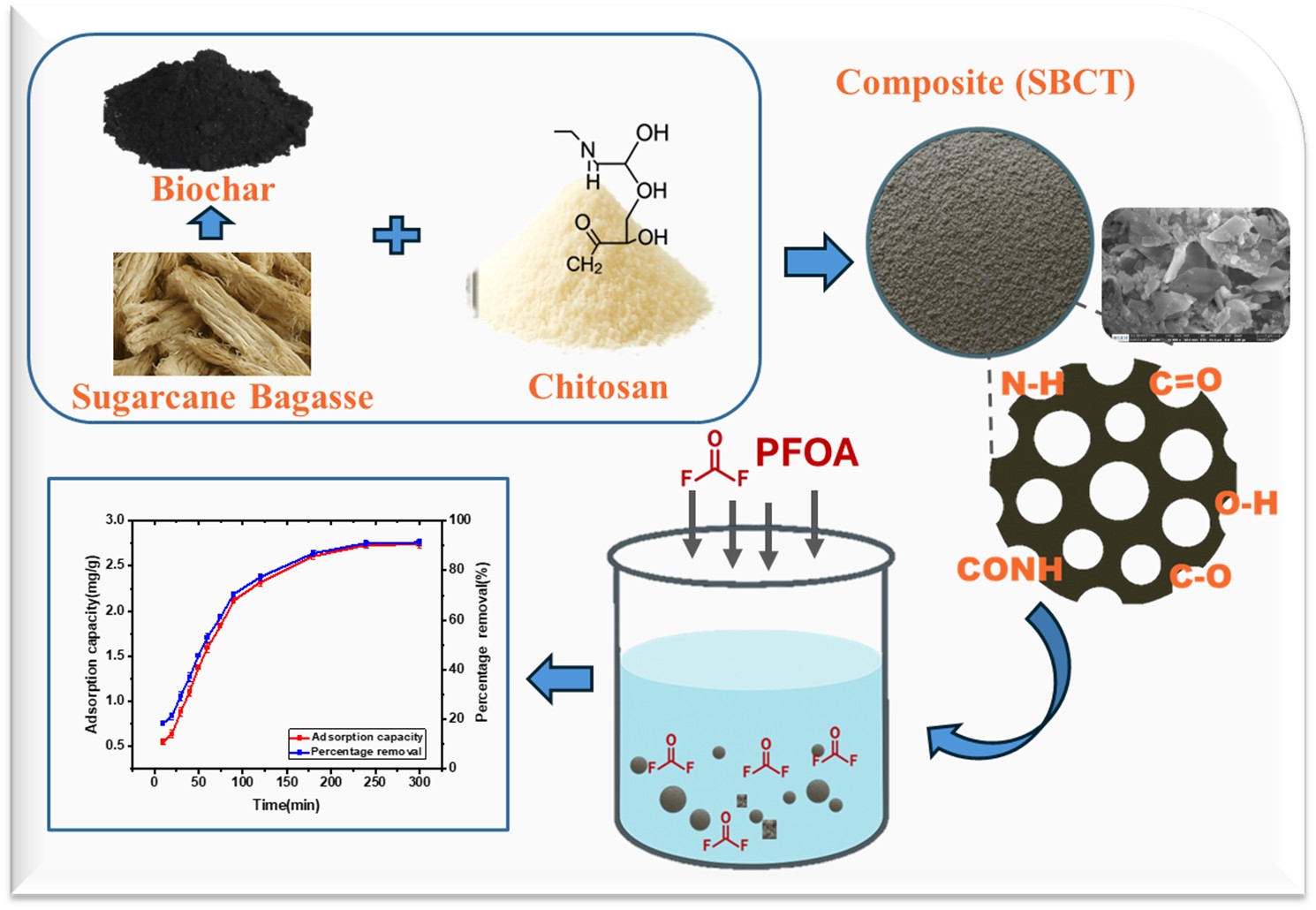

3.1. Novel Engineered SBCT

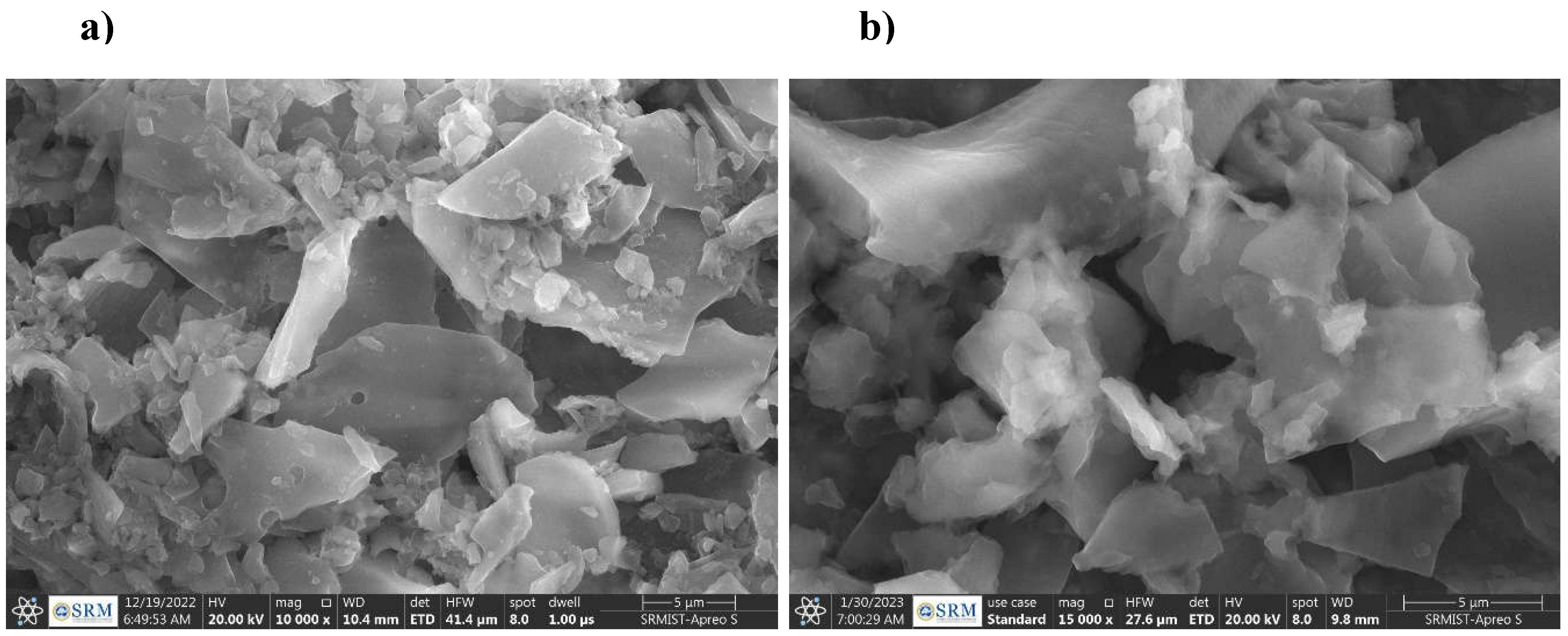

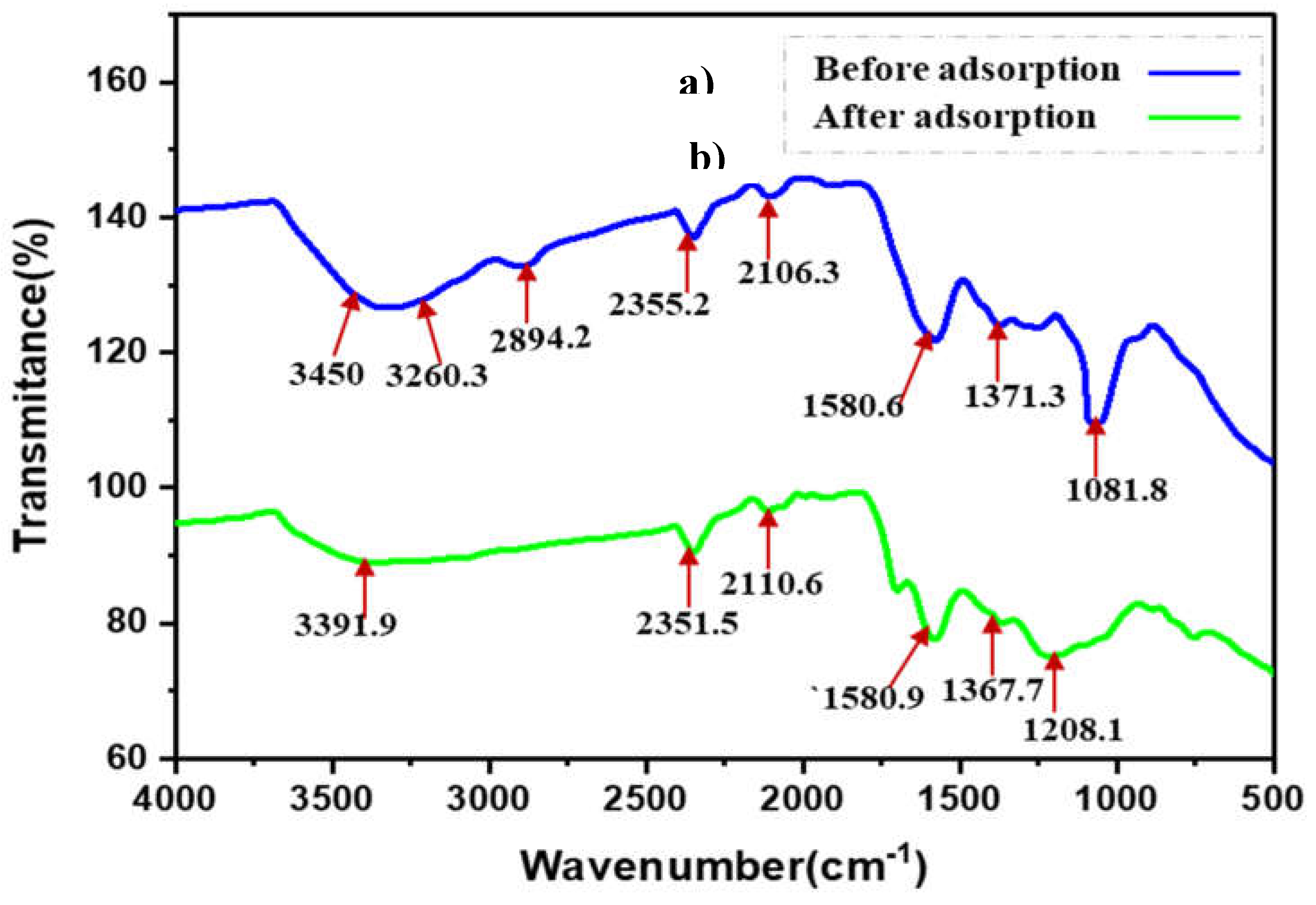

3.2. SBCT Characterization

3.3. Factors Governing PFOA Adsorption

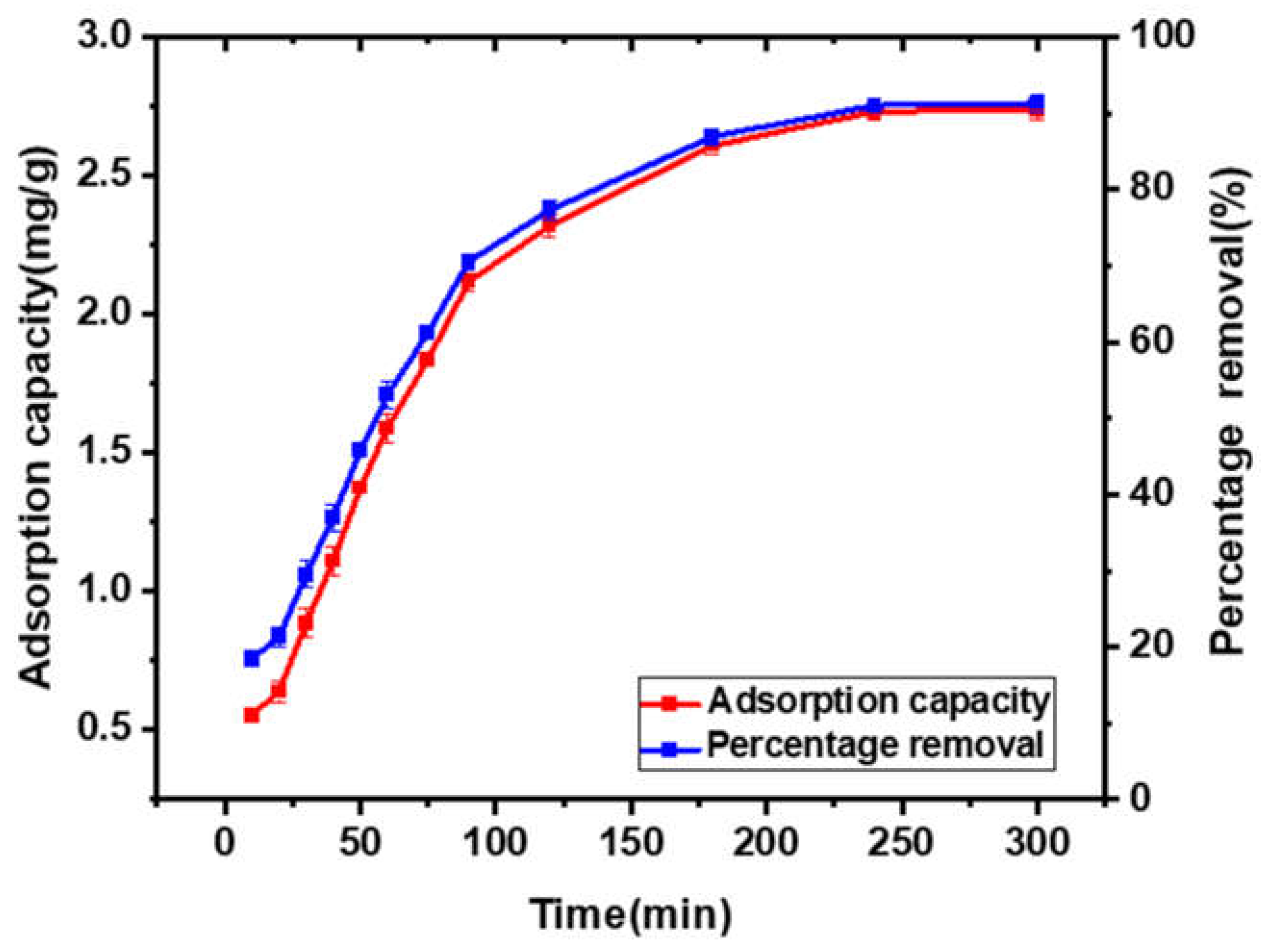

3.3.1. Contact Time

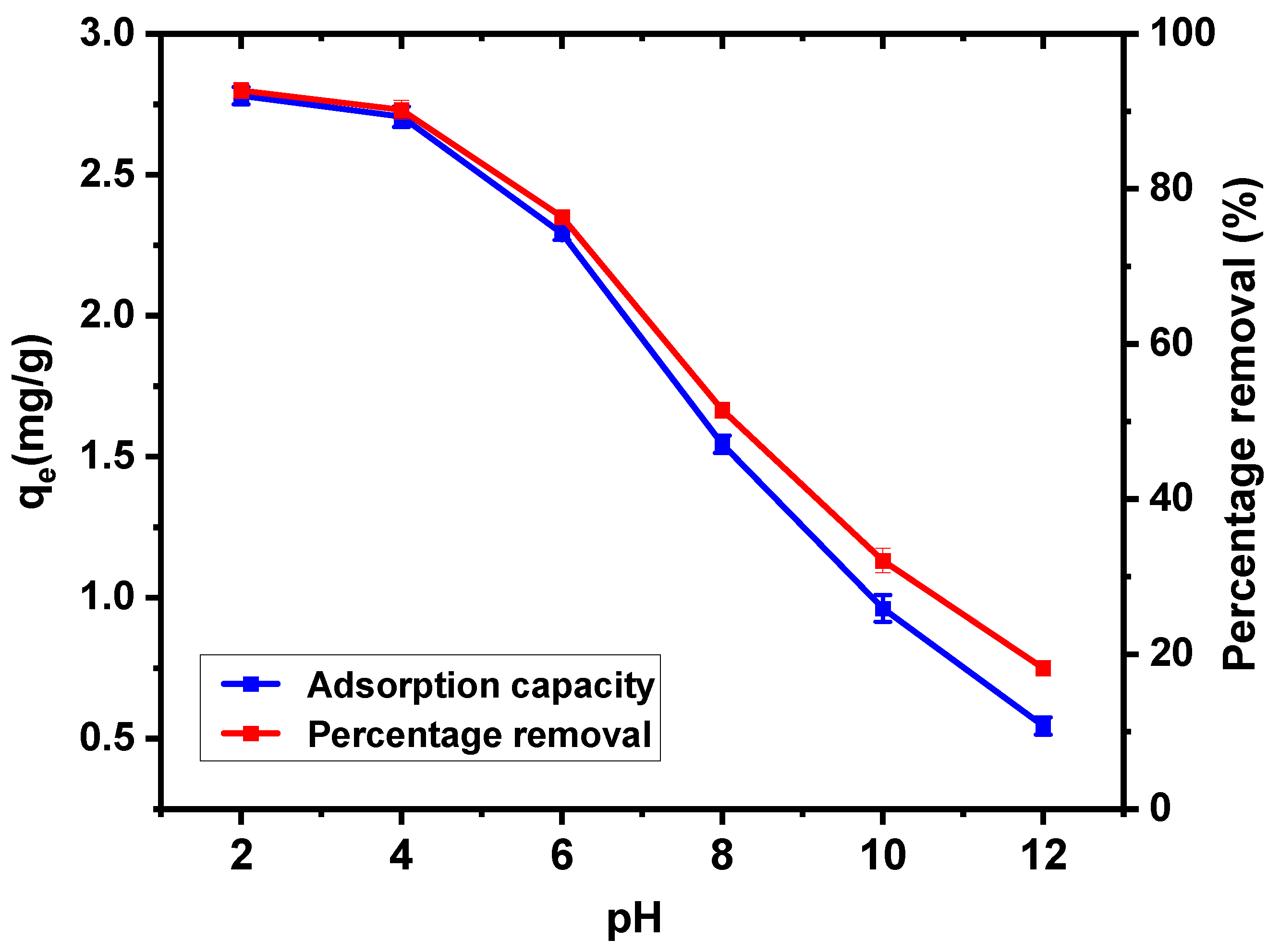

3.3.2. pH

3.3.3. Adsorbent Dosage and Initial Concentration

3.4. Adsorption Modelling of PFOA Using SBCT

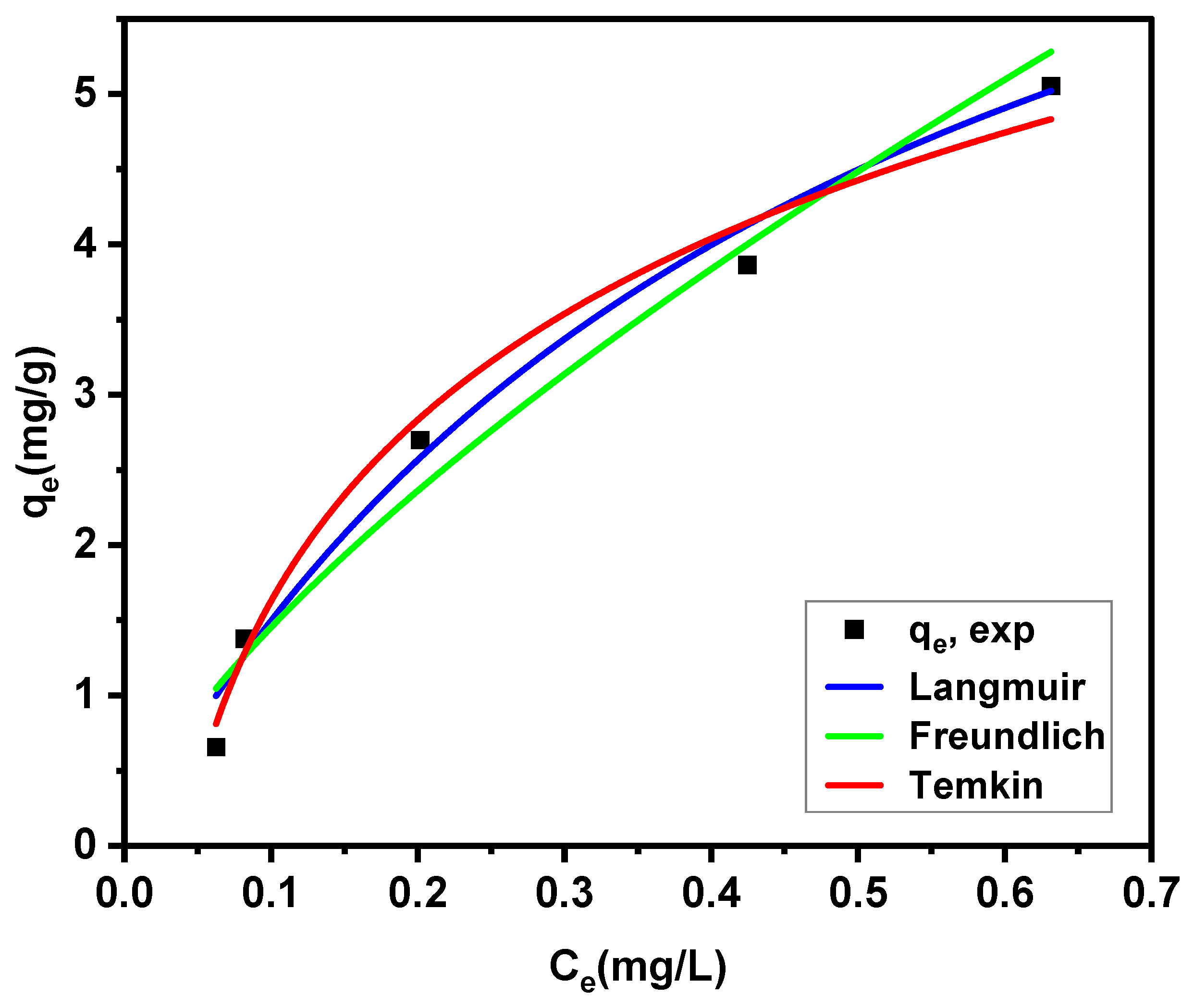

3.4.1. Isotherm Study

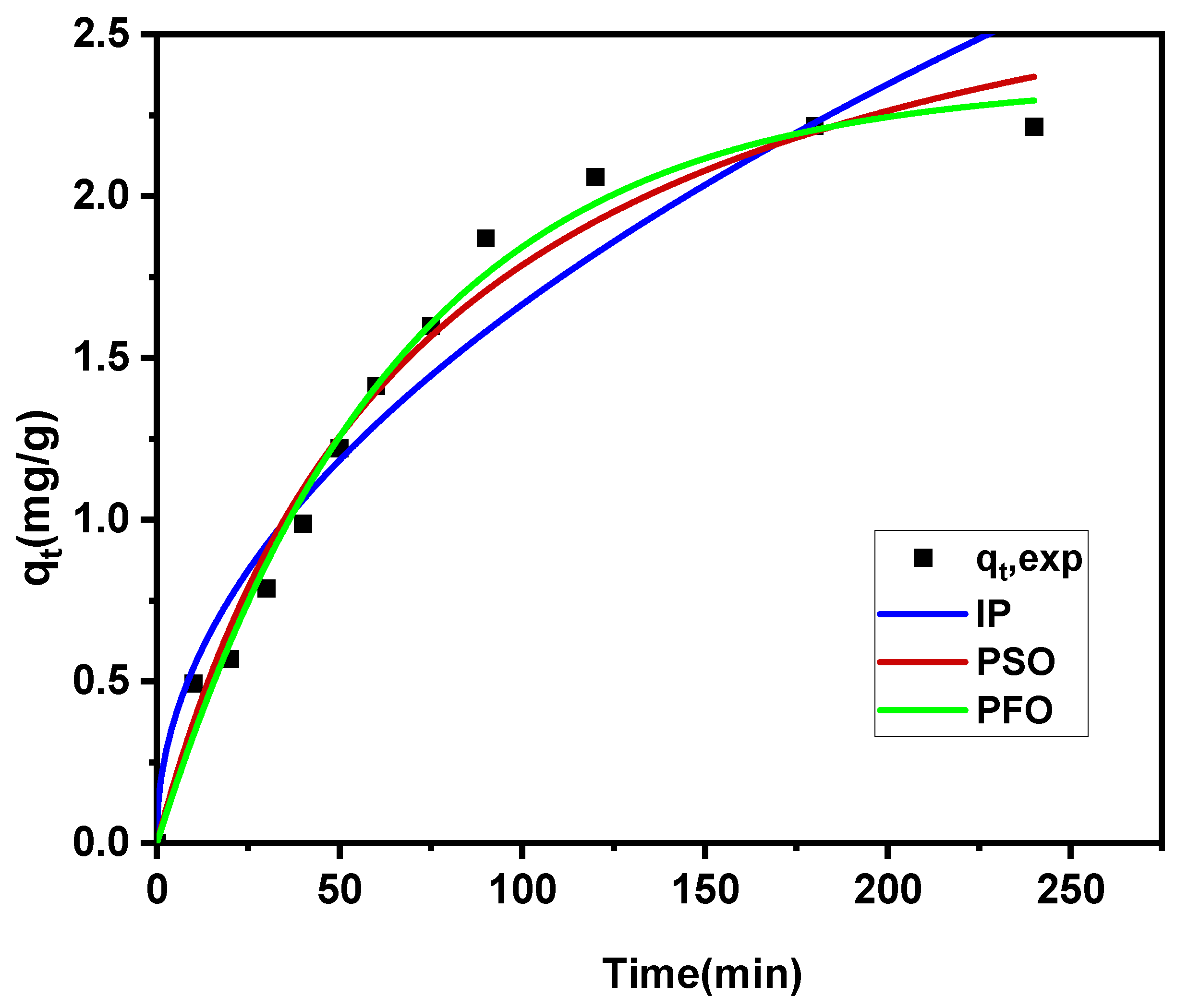

3.4.2. Kinetic Study

3.4.3. Thermodynamic Parameters

3.5. Regeneration Experiments

3.6. Comparative Analysis with Other Studies

3.7. Limitations and a Sustainable Way Forward

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Buck, R.C.; Franklin, J.; Berger, U.; Conder, J.M.; Cousins, I.T.; de Voogt, P.; Jensen, A.A.; Kannan, K.; Mabury, S.A.; van Leeuwen, S.P. Perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances in the environment: terminology, classification, and origins. Integr Environ Assess Manag 2011, 7, 513–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gluge, J.; Scheringer, M.; Cousins, I.T.; DeWitt, J.C.; Goldenman, G.; Herzke, D.; Lohmann, R.; Ng, C.A.; Trier, X.; Wang, Z. An overview of the uses of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS). Environ Sci Process Impacts 2020, 22, 2345–2373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Post, G.B.; Cohn, P.D.; Cooper, K.R. Perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA), an emerging drinking water contaminant: a critical review of recent literature. Environ Res 2012, 116, 93–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vierke, L.; Staude, C.; Biegel-Engler, A.; Drost, W.; Schulte, C. Perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA)—main concerns and regulatory developments in Europe from an environmental point of view. Environmental Sciences Europe 2012, 24, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OCED. WORKING TOWARDS A GLOBAL EMISSION INVENTORY OF PFASS: FOCUS ON PFCAS - STATUS QUO AND THE WAY FORWARD; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Lenka, S.P.; Kah, M.; Padhye, L.P. A review of the occurrence, transformation, and removal of poly- and perfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in wastewater treatment plants. Water Research 2021, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahman, M.F.; Peldszus, S.; Anderson, W.B. Behaviour and fate of perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) in drinking water treatment: a review. Water Res 2014, 50, 318–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- SC. Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants (POPs), The new POPs under the Stockholm Convention. Available online: https://chm.pops.int/TheConvention/ThePOPs/TheNewPOPs/tabid/2511/Default.aspx (accessed on 12 March 2025).

- U.S.EPA. TECHNICAL FACT SHEET – PFOS and PFOA. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Garg, S.; Kumar, P.; Mishra, V.; Guijt, R.; Singh, P.; Dumée, L.F.; Sharma, R.S. A review on the sources, occurrence and health risks of per-/poly-fluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) arising from the manufacture and disposal of electric and electronic products. Journal of Water Process Engineering 2020, 38, 101683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, G.W.; Burris, J.M.; Ehresman, D.J.; Froehlich, J.W.; Seacat, A.M.; Butenhoff, J.L.; Zobel, L.R. Half-life of serum elimination of perfluorooctanesulfonate, perfluorohexanesulfonate, and perfluorooctanoate in retired fluorochemical production workers. Environmental health perspectives 2007, 115, 1298–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvalaglio, M.; Muscionico, I.; Cavallotti, C. Determination of energies and sites of binding of PFOA and PFOS to human serum albumin. The journal of physical chemistry B 2010, 114, 14860–14874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castiglioni, S.; Valsecchi, S.; Polesello, S.; Rusconi, M.; Melis, M.; Palmiotto, M.; Manenti, A.; Davoli, E.; Zuccato, E. Sources and fate of perfluorinated compounds in the aqueous environment and in drinking water of a highly urbanized and industrialized area in Italy. J Hazard Mater 2015, 282, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, B.; Kang, P.; Wei, T.; Zhao, Y. Challenges of aqueous per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) and their foreseeable removal strategies. Chemosphere 2020, 250, 126316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Houtz, E.; Wang, M.; Park, J.-S. Identification and fate of aqueous film forming foam derived per-and polyfluoroalkyl substances in a wastewater treatment plant. Environmental science & technology 2018, 52, 13212–13221. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, C.; Chen, H.; Jiang, F. Adsorption of perflourooctane sulfonate (PFOS) and perfluorooctanoate (PFOA) on polyaniline nanotubes. Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochemical and Engineering Aspects 2015, 479, 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavithra, K.; Sharma, B.M.; Chakraborty, P. An overview of the occurrence and remediation of perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) in wastewater-recommendations for cost-effective removal techniques in developing economies. Current Opinion in Environmental Science & Health 2024, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanzana, S.; Fenti, A.; Iovino, P.; Panico, A. “A review of PFAS remediation: Separation and degradation technologies for water and wastewater treatment”. Journal of Water Process Engineering 2025, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, S.; Niu, L.; Bei, Y.; Wang, B.; Huang, J.; Yu, G. Adsorption of perfluorinated compounds on aminated rice husk prepared by atom transfer radical polymerization. Chemosphere 2013, 91, 124–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.; Li, D.; Li, C.; Ji, R.; Tian, X. Metal nanoparticles by doping carbon nanotubes improved the sorption of perfluorooctanoic acid. J Hazard Mater 2018, 351, 206–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, R.; Beckman, M.T.; Almquist, C.B.; Berberich, J.A.; Danielson, N.D. Fixed-bed adsorption of perfluorooctanoic acid from water by a polyamine-functionalized polychlorotrifluoroethylene-ethylene polymer coated on activated carbon. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering 2024, 12, 113001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, S.; López, J.F.; Solís, J.J.C.; Wong, M.S.; Villagrán, D. Enhanced adsorption of PFOA with nano MgAl2O4@CNTs: influence of pH and dosage, and environmental conditions. Journal of Hazardous Materials Advances 2023, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Xia, X.; Wang, X.; Qiao, J.; Chen, H. A comparative study on sorption of perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS) by chars, ash and carbon nanotubes. Chemosphere 2011, 83, 1313–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inyang, M.; Dickenson, E.R.V. The use of carbon adsorbents for the removal of perfluoroalkyl acids from potable reuse systems. Chemosphere 2017, 184, 168–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, D.; Li, C.; Chen, H.; Sørmo, E.; Cornelissen, G.; Gao, Y.; Reguyal, F.; Sarmah, A.; Ippolito, J.; Kammann, C. A critical review of biochar for the remediation of PFAS-contaminated soil and water. The Science of the Total Environment 2024, 951, 174962–174962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavan, D.; Mayilswamy, N.; Chame, S.; Kandasubramanian, B. Biochar Adsorption: A Green Approach to PFAS Contaminant Removal. CleanMat 2024, 1, 52–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, M.; Du, J.; Liu, Y.; Naidu, R.; Zhang, J.; Ahsan, M.A.; Qi, F. Magnetic biochar for removal of perfluorooctane sulphonate (PFOS): Interfacial interaction and adsorption mechanism. Environmental Technology & Innovation 2022, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saheed, I.O.; Oh, W.D.; Suah, F.B.M. Chitosan modifications for adsorption of pollutants - A review. J Hazard Mater 2021, 408, 124889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Huang, B.; Chai, L.; Liu, Y.; Zeng, G.; Wang, X.; Zeng, W.; Shang, M.; Deng, J.; Zhou, Z. Enhancement of As(v) adsorption from aqueous solution by a magnetic chitosan/biochar composite. RSC Advances 2017, 7, 10891–10900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Lang, Y.; Liu, B.; Zhao, H. Ofloxacin Adsorption on Chitosan/Biochar Composite: Kinetics, Isotherms, and Effects of Solution Chemistry. Polycyclic Aromatic Compounds 2018, 39, 287–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Gao, B.; Zimmerman, A.R.; Fang, J.; Sun, Y.; Cao, X. Sorption of heavy metals on chitosan-modified biochars and its biological effects. Chemical Engineering Journal 2013, 231, 512–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, M.M.; Ponnuchamy, M.; Kapoor, A.; Sivaraman, P. Bagasse based biochar for the adsorptive removal of chlorpyrifos from contaminated water. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering 2020, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponnusami, V.; Srivastava, S. Studies on application of teak leaf powders for the removal of color from synthetic and industrial effluents. Journal of hazardous materials 2009, 169, 1159–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Sun, H. Cost-effective detection of perfluoroalkyl carboxylic acids with gas chromatography: optimization of derivatization approaches and method validation. International journal of environmental research and public health 2020, 17, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foo, K.Y.; Hameed, B.H. Insights into the modeling of adsorption isotherm systems. Chemical engineering journal 2010, 156, 2–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, Y.-S.; McKay, G. Sorption of dye from aqueous solution by peat. Chemical engineering journal 1998, 70, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Zhao, J.; Wu, J.; Dai, G. Isotherm, thermodynamic, kinetics and adsorption mechanism studies of methyl orange by surfactant modified silkworm exuviae. Journal of hazardous materials 2011, 192, 246–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajapaksha, A.U.; Chen, S.S.; Tsang, D.C.; Zhang, M.; Vithanage, M.; Mandal, S.; Gao, B.; Bolan, N.S.; Ok, Y.S. Engineered/designer biochar for contaminant removal/immobilization from soil and water: Potential and implication of biochar modification. Chemosphere 2016, 148, 276–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, B.; Gao, B.; Fang, J. Recent advances in engineered biochar productions and applications. Critical Reviews in Environmental Science and Technology 2018, 47, 2158–2207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, X.-f.; Liu, S.-b.; Liu, Y.-g.; Gu, Y.-l.; Zeng, G.-m.; Hu, X.-j.; Wang, X.; Liu, S.-h.; Jiang, L.-h. Biochar as potential sustainable precursors for activated carbon production: Multiple applications in environmental protection and energy storage. Bioresource technology 2017, 227, 359–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, M.; Rajapaksha, A.U.; Lim, J.E.; Zhang, M.; Bolan, N.; Mohan, D.; Vithanage, M.; Lee, S.S.; Ok, Y.S. Biochar as a sorbent for contaminant management in soil and water: a review. Chemosphere 2014, 99, 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhuang, S. Removal of various pollutants from water and wastewater by modified chitosan adsorbents. Critical Reviews in Environmental Science and Technology 2017, 47, 2331–2386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, L.; Hu, X.; Yan, J.; Zeng, Y.; Zhang, J.; Xue, Y. Novel chitosan-ethylene glycol hydrogel for the removal of aqueous perfluorooctanoic acid. J Environ Sci (China) 2019, 84, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elanchezhiyan, S.S.; Preethi, J.; Rathinam, K.; Njaramba, L.K.; Park, C.M. Synthesis of magnetic chitosan biopolymeric spheres and their adsorption performances for PFOA and PFOS from aqueous environment. Carbohydr Polym 2021, 267, 118165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasilieva, T.; Chuhchin, D.; Lopatin, S.; Varlamov, V.; Sigarev, A.; Vasiliev, M. Chitin and cellulose processing in low-temperature electron beam plasma. Molecules 2017, 22, 1908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Xue, Y.; Long, L.; Zhang, K. Characteristics and batch experiments of acid- and alkali-modified corncob biomass for nitrate removal from aqueous solution. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int 2018, 25, 19932–19940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, S.; Zhang, Q.; Nie, Y.; Wei, H.; Wang, B.; Huang, J.; Yu, G.; Xing, B. Sorption mechanisms of perfluorinated compounds on carbon nanotubes. Environmental pollution 2012, 168, 138–144. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Du, Z.; Deng, S.; Chen, Y.; Wang, B.; Huang, J.; Wang, Y.; Yu, G. Removal of perfluorinated carboxylates from washing wastewater of perfluorooctanesulfonyl fluoride using activated carbons and resins. Journal of hazardous materials 2015, 286, 136–143. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tian, D.; Geng, D.; Tyler Mehler, W.; Goss, G.; Wang, T.; Yang, S.; Niu, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Zhang, Y. Removal of perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) from aqueous solution by amino-functionalized graphene oxide (AGO) aerogels: Influencing factors, kinetics, isotherms, and thermodynamic studies. Sci Total Environ 2021, 783, 147041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Shih, K. Adsorption of perfluorooctanesulfonate (PFOS) and perfluorooctanoate (PFOA) on alumina: influence of solution pH and cations. Water Res 2011, 45, 2925–2930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fagbayigbo, B.O.; Opeolu, B.O.; Fatoki, O.S.; Akenga, T.A.; Olatunji, O.S. Removal of PFOA and PFOS from aqueous solutions using activated carbon produced from Vitis vinifera leaf litter. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int 2017, 24, 13107–13120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, R.L.; Anschutz, A.J.; Smolen, J.M.; Simcik, M.F.; Penn, R.L. The adsorption of perfluorooctane sulfonate onto sand, clay, and iron oxide surfaces. Journal of Chemical & Engineering Data 2007, 52, 1165–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundquist, N.A.; Sweetman, M.J.; Scroggie, K.R.; Worthington, M.J.H.; Esdaile, L.J.; Alboaiji, S.F.K.; Plush, S.E.; Hayball, J.D.; Chalker, J.M. Polymer Supported Carbon for Safe and Effective Remediation of PFOA- and PFOS-Contaminated Water. ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering 2019, 7, 11044–11049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mall, I.D.; Srivastava, V.C.; Agarwal, N.K.; Mishra, I.M. Adsorptive removal of malachite green dye from aqueous solution by bagasse fly ash and activated carbon-kinetic study and equilibrium isotherm analyses. Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochemical and Engineering Aspects 2005, 264, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langmuir, I. The adsorption of gases on plane surfaces of glass, mica and platinum. Journal of the American Chemical society 1918, 40, 1361–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freundlich, H. Uber die adsorption in Iosungen. Zeitschrift fur physikalische Chemie (Leipzig) 1906, 57A. [Google Scholar]

- Temkin, M. Kinetics of ammonia synthesis on promoted iron catalysts. Acta physiochim. URSS 1940, 12, 327–356. [Google Scholar]

- Niu, B.; Yang, S.; Li, Y.; Zang, K.; Sun, C.; Yu, M.; Zhou, L.; Zheng, Y. Regenerable magnetic carbonized Calotropis gigantea fiber for hydrophobic-driven fast removal of perfluoroalkyl pollutants. Cellulose 2020, 27, 5893–5905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, W.J., Jr.; Morris, J.C. Kinetics of adsorption on carbon from solution. Journal of the sanitary engineering division 1963, 89, 31–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omo-Okoro, P.N.; Curtis, C.J.; Karásková, P.; Melymuk, L.; Oyewo, O.A.; Okonkwo, J.O. Kinetics, isotherm, and thermodynamic studies of the adsorption mechanism of PFOS and PFOA using inactivated and chemically activated maize tassel. Water, Air, & Soil Pollution 2020, 231, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, B.; Kan, E.; Zeng, S. Enhanced adsorption of aqueous perfluorooctanoic acid on iron-functionalized biochar: elucidating the roles of inner-sphere complexation. Science of The Total Environment 2024, 955, 176926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, F.; Wang, L.; Yao, Y.; Wu, F.; Sun, H.; Lu, S. Synthesis and application of a highly selective molecularly imprinted adsorbent based on multi-walled carbon nanotubes for selective removal of perfluorooctanoic acid. Environmental Science: Water Research & Technology 2018, 4, 689–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Luo, Q.; Gao, B.; Chiang, S.-Y.D.; Woodward, D.; Huang, Q. Sorption of perfluorooctanoic acid, perfluorooctane sulfonate and perfluoroheptanoic acid on granular activated carbon. Chemosphere 2016, 144, 2336–2342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Volchek, K.; Brown, C.E.; Robinson, A.; Obal, T. Comparative study on adsorption of perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS) and perfluorooctanoate (PFOA) by different adsorbents in water. Water Science and Technology 2014, 70, 1983–1991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, S.; Nie, Y.; Du, Z.; Huang, Q.; Meng, P.; Wang, B.; Huang, J.; Yu, G. Enhanced adsorption of perfluorooctane sulfonate and perfluorooctanoate by bamboo-derived granular activated carbon. Journal of hazardous materials 2015, 282, 150–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.; Wang, L.; Liu, J.; Tang, J.; Zhao, D. Removal of aqueous perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) using starch-stabilized magnetite nanoparticles. Science of the Total Environment 2016, 562, 191–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Xu, M.; Huang, D.; Xu, L.; Yu, M.; Zhu, Y.; Niu, J. Modulating hierarchically microporous biochar via molten alkali treatment for efficient adsorption removal of perfluorinated carboxylic acids from wastewater. Science of the Total Environment 2021, 757, 143719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, B.; Yu, M.; Sun, C.; Wang, L.; Niu, Y.; Huang, H.; Zheng, Y. A comparative study for removal of perfluorooctanoic acid using three kinds of N-polymer functionalized Calotropis gigantea fiber. Journal of Natural Fibers 2022, 19, 2119–2128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badruddoza, A.Z.M.; Bhattarai, B.; Suri, R.P. Environmentally friendly β-cyclodextrin–ionic liquid polyurethane-modified magnetic sorbent for the removal of PFOA, PFOS, and Cr (VI) from water. ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering 2017, 5, 9223–9232. [Google Scholar]

| Nonlinear Isotherm Models | Langmuir | Freundlich | Temkim | ||||||||

| Parameters | qmax (mg/g) |

KLq (L/mg) |

RLq | R2 | n | 1/n | Kfe | R2 | B | KTm (L/mg) |

R2 |

| SBCT | 9.01 | 6.80 | 0.18 | 0.95 | 0.69 | 0.318 | 7.28 | 0.92 | 1.73 | 25.51 | 0.91 |

| Kinetic Models | First order | Second order | Intraparticle diffusion model | ||||||

| Parameters |

qeq (mg/g) |

K1 (1/hr) |

R2 | qeq | K2 | R2 | Kipd | C | R2 |

| Value | 2.784 | 0.014 | 0.992 | 3.477 | 0.004 | 0.981 | 0.166 | 0.167 | 0.90 |

| Parameters | ΔGo(KJ mol−1) |

ΔHo (KJ/mol) |

ΔSo (J/mol/K) |

||||

|

293°K |

298°K | 303°K | 308°K | 313°K | |||

| Value | - 6.65±0.22 | -6.67±0.26 | -6.09±0.15 | -5.95±0.19 | -5.72±0.13 | -21.8 | -51.3 |

| Adsorbent | Initial concentrationC0 (mg/L) | pH | Equilibrium time tequi (h) | Equilibrium adsorption capacity qeq (mg/g) | Maximum adsorption capacity qmax (mg/g)/ Isotherm model | Reference |

| Rice husk BC | 100 - 200 | 5 | 5 | 550 | 1085/Lq | [19] |

| Multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNT) | 10-500 | 5 | 4 | 12.4 | 5.4 /Fe | [64] |

| Bamboo AC | 20-250 | 5.0 | 24 | 576 | 544/Fe | [65] |

| Starch-stabilized Fe3O4 nanoparticles | 0-4 | 6.8 | 0.5 | 15.53 | 62.5/Lq | [66] |

|

Granular activated carbon (GAC) |

0.5-10 |

5 | 120 | 12.6 | 52.8/Lq | [63] |

| Chitosan + hydrogel | 100-2000 | - | < 24 | 1050.83 | 1275.9/Lq- Fe | [43] |

| Sulfur polymer support activated carbon | 0.250 –5 | 5 | - | - | 0.355 / Lq-Fe | [53] |

| Magnetic carbonized fiber | 25 –250 | 3 | 2 | 41.85 | 204.7/Lq | [58] |

| Hierarchically microporous biochar (HMB) | 50–150 | 2-10 | 0.5 | 423 | 1269/Lq | [67] |

| Calotropis Gigantea fiber | 25–250 | - | 3 | 54.76 | 232.8/Lq | [68] |

| Polyurethane-modified magnetic sorbent | 0.05-1 | 5.5 | 46 | 243.9(µg/g) | 2.480/Sips | [69] |

| Multi-walled carbon nanotubes @Molecular imprinted polymers (MWCNTs@MIPs) | 0.10–20 | 5 | 2 | 1.44 | 12.4/Lq | [62] |

| Sugarcane bagasse biochar/Chitosan composite (SBCT) | 0.5-4 | 4 | 4 | 5.1 | 9.01/Lq | Our study |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.