Submitted:

31 December 2025

Posted:

01 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

Methods

2. AMPs as Emerging Therapeutics for Gastrointestinal Pathogens

2.1. Interaction Between Intestinal Microbiota and Epithelial Antimicrobial Peptides

- (i)

- maintaining the spatial structure of microbial communities, forming distinct gastrointestinal niches for various taxa;

- (ii)

- preventing colonization by pathogens by limiting their adhesion and invasion;

- (iii)

- creating a sterile layer over the epithelium (especially due to RegIIIγ), preventing bacterial contact with the mucosa;

- (iv)

- regulating innate immunity, including modulating Toll-like receptors, producing cytokines, and controlling the inflammatory response.

2.1.1. Defensins as Key Epithelial Effector Molecules of Intestinal Innate Immunity

2.1.2. Cathelicidin LL-37 in the Gut: Immunomodulatory Mechanisms and Barrier-Protective Functions

2.1.3. Regenerating AMPs (RegIII) and the Spatial Organization of the Gut Microbiota

2.1.4. The Overall Role of Epithelial Antimicrobial Peptides in Intestinal Homeostasis

2.2. Natural Antimicrobial Peptides: Structural Organization and Mechanisms of Action

2.2.1. Structural Diversity of Natural AMPs

2.2.2. Molecular Mechanisms of Action of Natural AMPs

2.3. Synthetic Antimicrobial Peptides: A Modern Idea and Their Role in Medicine

3. Challenges and Innovations in AMP Development

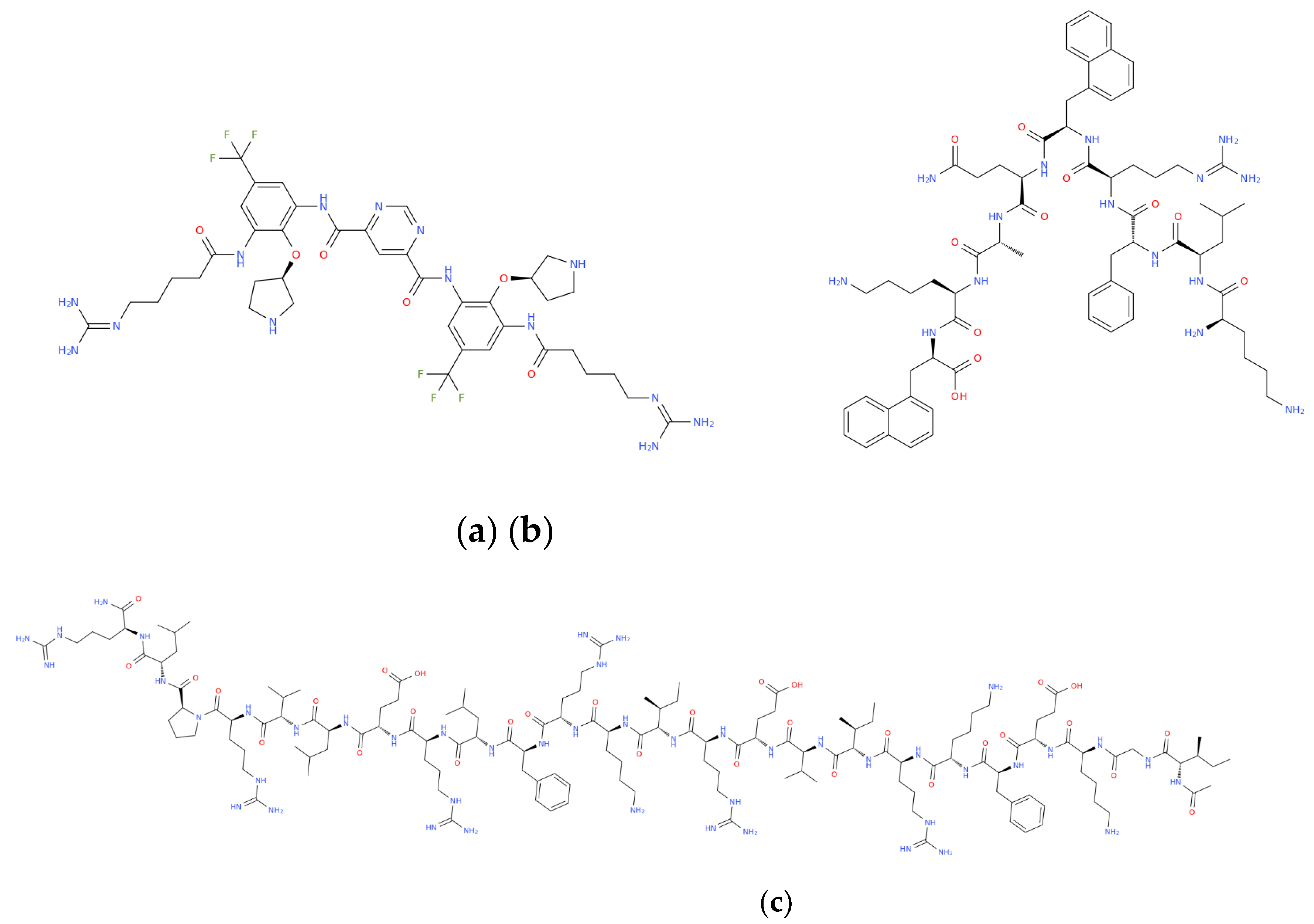

Structure–Activity Relationships and Selectivity of Antimicrobial Peptides

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Abbreviation | Full name / Meaning |

| AMP | Antimicrobial Peptide |

| CAMP | Cationic Antimicrobial Peptide |

| HD-5 / HD-6 | Human Defensin 5 / 6 |

| LL-37 | Human Cathelicidin Peptide |

| HBD | Human Beta-Defensin |

| MDR | Multidrug-Resistant |

| XDR | Extensively Drug-Resistant |

| MRSA | Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus |

| SSTI | Skin and Soft Tissue Infections |

| LPS | Lipopolysaccharide |

| LTA | Lipoteichoic Acid |

| QS | Quorum Sensing |

| GI Tract | Gastrointestinal Tract |

| IBD | Inflammatory Bowel Disease |

| NEC | Necrotizing Enterocolitis |

| PRR | Pattern-Recognition Receptor |

| TLR | Toll-Like Receptor |

| NF-κB | Nuclear Factor kappa B |

| MAPK | Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase |

| CFU | Colony-Forming Unit |

| MIC | Minimum Inhibitory Concentration |

| IDR | Innate Defense Regulator |

| PAMPs | Pathogen-Associated Molecular Patterns |

| APC | Antigen-Presenting Cell |

| IEC | Intestinal Epithelial Cells |

| SCFA | Short-Chain Fatty Acids |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

References

- World Health Organization. Global antimicrobial resistance and use surveillance system (GLASS) report: 2022; WHO Press: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022; Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240062702 (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Wang, B.; Chen, D.; Chen, H.; Wu, W.; Cheng, K.; Tao, Y.; Zhang, L.; Liu, C.; Ou, D.; Zhang, M.; Tang, X.; Wang, S.; Wang, G.; Luo, B. Global, regional, and national incidence and mortality for enteric infections from 1990 to 2019. BMC Public Health. 2025, 25, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Neill, J. Tackling Drug-Resistant Infections Globally: Final Report and Recommendations; UK Government: London, UK, 2016; Available online: https://amr-review.org (accessed on 9 November 2025).

- Salam, M.A.; Al-Amin, M.Y.; Salam, M.T.; Pawar, J.S.; Akhter, N.; Rabaan, A.A.; Alqumber, M.A.A. Antimicrobial Resistance: A Growing Serious Threat for Global Public Health. Healthcare 2023, 11, 1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Exner, M.; Bhattacharya, S.; Christiansen, B.; Gebel, J.; Goroncy-Bermes, P.; Hartemann, P.; Heeg, P.; Ilschner, C.; Kramer, A.; Larson, E.; Merkens, W.; Mielke, M.; Oltmanns, P.; Ross, B.; Rotter, M.; Schmithausen, R.M.; Sonntag, H.G.; Trautmann, M. Antibiotic Resistance: What Is So Special about Multidrug-Resistant Gram-Negative Bacteria? GMS Hygiene and Infection Control 2017, 12, Doc05. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birlutiu, V.; Birlutiu, R.-M. An Overview of the Epidemiology of Multidrug Resistance and Bacterial Resistance Mechanisms: What Solutions Are Available? A Comprehensive Review. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, S.; Cerceo, E. Trends, Epidemiology, and Management of Multi-Drug Resistant Gram-Negative Bacterial Infections in the Hospitalized Setting. Antibiotics 2020, 9, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouanga-Ndzime, Y.; Bisseye, C.; Longo-Pendy, N.-M.; Bignoumba, M.; Dikoumba, A.-C.; Onanga, R. Trends in Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae Urinary Tract Infections and Antibiotic Resistance over a 5-Year Period in Southeastern Gabon. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.K.; Hussein, S.; Qurbani, K.; Ibrahim, R.H.; Fareeq, A.; Mahmood, K.A.; Mohamed, M.G. Antimicrobial Resistance: Impacts, Challenges, and Future Prospects. Global Medicine 2024, 100081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, M.; Antunes, W.; Mota, S.; Madureira-Carvalho, Á.; Dinis-Oliveira, R.J.; Dias da Silva, D. An Overview of the Recent Advances in Antimicrobial Resistance. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 1920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslam, B.; Wang, W.; Arshad, M.I.; Khurshid, M.; Muzammil, S.; Rasool, M.H.; Nisar, M.A.; Alvi, R.F.; Aslam, M.A.; Qamar, M.U.; Salamat, M.K.F.; Baloch, Z. Antibiotic resistance: A rundown of a global crisis. Infect. Drug Resist. 2018, 11, 1645–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huan, Y.; Kong, Q.; Mou, H.; Yi, H. Antimicrobial Peptides: Classification, Design, Application and Research Progress in Multiple Fields. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 582779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.; Garg, A.; Srivastava, A.; Arora, P.K. The Role of Antimicrobial Peptides in Overcoming Antibiotic Resistance. Microbe 2025, 7, 100337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, T.; Fu, J.; Shi, L.; Chen, X.; Zong, X. Antimicrobial Peptides in Gut Health: A Review. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 751010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saeed, S.I.; Mergani, A.; Aklilu, E.; Kamaruzzaman, N.F. Antimicrobial Peptides: Bringing Solution to the Rising Threats of Antimicrobial Resistance in Livestock. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 851052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- del Olmo, M.; Andreu, C. Current Status of the Application of Antimicrobial Peptides and Their Conjugated Derivatives. Molecules 2025, 30, 3070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.Y.; Yan, Z.B.; Meng, Y.M.; Gao, F.G.; Wang, L.; Zhu, X.Q.; Wang, R.; Qin, Y. Antimicrobial Peptides: Mechanism of Action, Activity and Clinical Potential. Mil. Med. Res. 2021, 8, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, D.; Dhiman, I.; Das, S.; Das, D.K.; Pramanik, D.D.; Dash, S.K.; Pramanik, A. Recent Advances in Therapeutic Peptides: Innovations and Applications in Treating Infections and Diseases. ACS Omega 2025, 10, 17087–17107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakare, O.O.; Gokul, A.; Niekerk, L.-A.; Aina, O.; Abiona, A.; Barker, A.M.; Basson, G.; Nkomo, M.; Otomo, L.; Keyster, M.; et al. Recent Progress in the Characterization, Synthesis, Delivery Procedures, Treatment Strategies, and Precision of Antimicrobial Peptides. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 11864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Lv, J.; Ma, Z.; Ma, J.; Chen, J. Advances in Antimicrobial Peptides: Mechanisms, Design Innovations, and Biomedical Potential. Molecules 2025, 30, 1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, C.J.L.; Ikuta, K.S.; Sharara, F.; Swetschinski, L.; Robles Aguilar, G.; Gray, A.; Han, C.; Bisignani, C.; Rao, P.; Wool, E.; Johnson, S.C.; Browne, A.J.; Chipeta, M.G.; Fell, F.; Hackett, S.; Haines-Woodhouse, G.; Kashef Hamadani, B.H.; Kumaran, E.A.P.; McManigal, B.; Agarwal, R.; Akech, S.; Albertson, S.; Amuasi, J.; Andrews, J.; Aravkin, A.; Ashley, E.; Bailey, F.; Baker, S.; Basnyat, B.; Bekker, A.; Bender, R.; Bethou, A.; Bielicki, J.; Boonkasidecha, S.; Bukosia, J.; Carvalheiro, C.; Castañeda-Orjuela, C.; Chansamouth, V.; Chaurasia, S.; Chiurchiù, S.; Chowdhury, F.; Cook, A.J.; Cooper, B.; Cressey, T.R.; Criollo-Mora, E.; Cunningham, M.; Darboe, S.; Day, N.P.J.; Feasey, N.; Musicha, P. Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019. a systematic analysis. The Lancet 2022, 399, 629–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Xu, N.; Lu, T.; Wang, T.; Hong, W.; Fu, Z.; Penuelas, J.; Gillings, M.; Qian, H. Antimicrobial Peptides in the Global Microbiome: Biosynthetic Genes and Resistance Determinants. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 57, 7698–7708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moravej, H.; Moravej, Z.; Yazdanparast, M.; Heiat, M.; Mirhosseini, A.; Moosazadeh Moghaddam, M.; Mirnejad, R. Antimicrobial Peptides: Features, Action, and Their Resistance Mechanisms in Bacteria. Microb. Drug Resist. 2018, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, T.-H.; Hall, K.; Aguilar, M.-I. Antimicrobial Peptide Structure and Mechanism of Action: A Focus on the Role of Membrane Structure. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2016, 16, 25–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guilhelmelli, F.; Vilela, N.; Albuquerque, P.; Derengowski, L.S.; Silva-Pereira, I.; Kyaw, C.M. Antibiotic Development Challenges: The Various Mechanisms of Action of Antimicrobial Peptides and of Bacterial Resistance. Front. Microbiol. 2013, 4, 353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pei, J.; Xiong, L.; Wu, X.; Chu, M.; Bao, P.; Ge, Q.; Guo, X. Bovine Lactoferricin Exerts Antibacterial Activity against Four Gram-Negative Pathogenic Bacteria by Transforming Its Molecular Structure. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2025, 15, 1508895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Smet, K.; Contreras, R. Human Antimicrobial Peptides: Defensins, Cathelicidins and Histatins. Biotechnol. Lett. 2005, 27, 1337–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morici, P.; Florio, W.; Rizzato, C.; et al. Synergistic Activity of Synthetic N-Terminal Peptide of Human Lactoferrin in Combination with Various Antibiotics against Carbapenem-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae Strains. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2017, 36, 1739–1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khurshid, Z.; Najeeb, S.; Mali, M.; Moin, S.F.; Raza, S.Q.; Zohaib, S.; Sefat, F.; Zafar, M.S. Histatin Peptides: Pharmacological Functions and Their Applications in Dentistry. Saudi Pharm. J. 2017, 25, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fassi, E.M.A.; Moretti, R.M.; Montagnani Marelli, M.; Garofalo, M.; Gori, A.; Pesce, C.; Albani, M.; Milano, E.G.; Sgrignani, J.; Cavalli, A.; et al. FYCO1 Peptide Analogs: Design and Characterization of Autophagy Inhibitors as Co-Adjuvants in Taxane Chemotherapy of Prostate Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 5365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, M.F.; Abdelkhalek, A.; Seleem, M.N. Evaluation of short synthetic antimicrobial peptides for treatment of drug-resistant and intracellular Staphylococcus aureus. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 29707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parra, A.L.; Bezerra, L.P.; Shawar, D.E.; Neto, N.A.; Mesquita, F.P.; da Silva, G.O.; Souza, P.F. Synthetic antiviral peptides: A new way to develop targeted antiviral drugs. Future Virol. 2022, 17, 577–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Tall, Y.; Alkurdi, Y.; Alshraiedeh, N.; Sabi, S.H. Designing Novel Antimicrobial Agents from the Synthetic Antimicrobial Peptide (Pep-38) to Combat Antibiotic Resistance. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mercer, D.K.; O’Neil, D.A. Innate inspiration: Antifungal peptides and other immunotherapeutics from the host immune response. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 2177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, H.-X.; Zou, Y.-L.; Duan, J.-J.; Jia, Z.-R.; Li, X.-J.; Wang, Z.; et al. The synthetic melanocortin (CKPV)2 exerts anti-fungal and anti-inflammatory effects against Candida albicans vaginitis via inducing macrophage M2 polarization. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e56004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhattacharjya, S.; Mohid, S.A.; Bhunia, A. Atomic-Resolution Structures and Mode of Action of Clinically Relevant Antimicrobial Peptides. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 4558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesiak, A.; Paprocka, P.; Wnorowska, U.; Mańkowska, A.; Król, G.; Głuszek, K.; Piktel, E.; Spałek, J.; Okła, S.; Fiedoruk, K.; Durnaś, B.; Bucki, R. Significance of host antimicrobial peptides in the pathogenesis and treatment of acne vulgaris. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1502242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brouwer, C.; van der Linden, Y.; Carrasco, M.R.; Alwasel, S.; Abalkhail, T.; Al-Otibi, F.O.; Boekhout, T.; Welling, M.M. Synthetic Human Lactoferrin Peptide hLF(1-11) Shows Antifungal Activity and Synergism with Fluconazole and Anidulafungin Towards Candida albicans and Various Non-Albicans Candida Species, Including Candidozyma auris. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, M.-D.; Won, H.-S.; Kim, J.-H.; Mishig-Ochir, T.; Lee, B.-J. Antimicrobial Peptides for Therapeutic Applications: A Review. Molecules 2012, 17, 12276–12286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.; Bhagwat, P.; Singh, S.; Pillai, S. A Review on the Diversity of Antimicrobial Peptides and Genome Mining Strategies for Their Prediction. Biochimie 2024, 227, 99–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niyonsaba, F.; Madera, L.; Afacan, N.; Okumura, K.; Ogawa, H.; Hancock, R.E. The Innate Defense Regulator Peptides IDR-HH2, IDR-1002, and IDR-1018 Modulate Human Neutrophil Functions. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2013, 94, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ming, L.; Huang, J.-A. The Antibacterial Effects of Antimicrobial Peptides OP-145 against Clinically Isolated Multi-Resistant Strains. Jpn. J. Infect. Dis. 2017, 70, 601–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, K.-T.; Wu, C.-L.; Yip, B.-S.; Chih, Y.-H.; Peng, K.-L.; Hsu, S.-Y.; Yu, H.-Y.; Cheng, J.-W. The Interactions between the Antimicrobial Peptide P-113 and Living Candida albicans Cells Shed Light on Mechanisms of Antifungal Activity and Resistance. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 2654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jang, W.S.; Li, X.S.; Sun, J.N.; Edgerton, M. The P-113 Fragment of Histatin 5 Requires a Specific Peptide Sequence for Intracellular Translocation in Candida albicans, Which Is Independent of Cell Wall Binding. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2008, 52, 497–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdelsattar, A.S.; Abutaleb, N.S.; Seleem, M.N. A Novel Peptide Mimetic, Brilacidin, for Combating Multidrug-Resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0325722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomes, A.R.; Varela, C.L.; Pires, A.S.; Tavares-da-Silva, E.J.; Roleira, F.M.F. Synthetic and Natural Guanidine Derivatives as Antitumor and Antimicrobial Agents: A Review. Bioorg. Chem. 2023, 138, 106600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hetta, H.F.; Sirag, N.; Alsharif, S.M.; Alharbi, A.A.; Alkindy, T.T.; Alkhamali, A.; Albalawi, A.S.; Ramadan, Y.N.; Rashed, Z.I.; Alanazi, F.E. Antimicrobial Peptides: The Game-Changer in the Epic Battle Against Multidrug-Resistant Bacteria. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odunitan, T.T.; Apanisile, B.T.; Afolabi, J.A.; Adeniwura, P.O.; Akinboade, M.W.; Ibrahim, N.O.; Alare, K.P.; Saibu, O.A.; Adeosun, O.A.; Opeyemi, H.S.; Ayiti, K.S. Beyond Conventional Drug Design: Exploring the Broad-Spectrum Efficacy of Antimicrobial Peptides. Chem. Biodivers. 2024, e202401349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, I.A.; Henriques, S.T.; Blaskovich, M.A.T.; Elliott, A.G.; Cooper, M.A. Investigations into the Membrane Activity of Arenicin Antimicrobial Peptide AA139. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gen. Subj. 2022, 1866, 130156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, A.G.; Huang, J.X.; Neve, S.; Johannes Zuegg, J.; Edwards, I.; K. Cain, A.; J. Boinett, Ch.; Barquist, L.; Lundberg, C.V.; Steen, J.; Butler, M.S.; Mobli, M.; Porter, K.M.; Blaskovich, M.A.T.; Lociuro, S.; Strandh, M.; Cooper, M.A. An Amphipathic Peptide with Antibiotic Activity against Multidrug-Resistant Gram-Negative Bacteria. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 3184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourreille, A.; Doubremelle, M.; Raingeard de la Blétière, D.; Segain, J.P.; Toquet, C.; Buelow, R.; Galmiche, J.P. RDP58, a Novel Immunomodulatory Peptide with Anti-Inflammatory Effects: A Pharmacological Study in Trinitrobenzene Sulphonic Acid Colitis and Crohn Disease. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2003, 38, 526–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vry, C.G.; Valdez, M.; Lazarov, M.; Muhr, E.; Buelow, R.; Fong, T.; Iyer, S. Topical Application of a Novel Immunomodulatory Peptide, RDP58, Reduces Skin Inflammation in the Phorbol Ester-Induced Dermatitis Model. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2005, 125, 473–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iseganan, I.B. IB 367, Protegrin IB 367. Drugs R D 2002, 3, 52–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolosov, I.A.; Panteleev, P.V.; Sychev, S.V.; Khokhlova, V.A.; Safronova, V.N.; Toropygin, I.Y.; Kombarova, T.I.; Korobova, O.V.; Pereskokova, E.S.; Borzilov, A.I.; et al. Design of Protegrin-1 Analogs with Improved Antibacterial Selectivity. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 2047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Koh, J.-J.; Liu, S.; Lakshminarayanan, R.; Verma, C.S.; Beuerman, R.W. Membrane Active Antimicrobial Peptides: Translating Mechanistic Insights to Design. Front. Neurosci. 2017, 11, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomes, A.; Gomes, P. Peptides and Peptidomimetics in the Development of Hydrogels toward the Treatment of Diabetic Wounds. Curr. Res. Biotechnol. 2025, 9, 100292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, A.C.; Janson, H.W.; Wold, H.; Fugelli, A.; Andersson, K.; Håkangård, C.; Olsson, P.; Olsen, W.M. LTX-109 Is a Novel Agent for Nasal Decolonization of Methicillin-Resistant and -Sensitive Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2015, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Midura-Nowaczek, K.; Markowska, A. Antimicrobial Peptides and Their Analogs: Searching for New Potential Therapeutics. Perspect. Med. Chem. 2014, 6, PMC.S13215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Ong, Z.Y.; Qu, S.; Wang, Y.; Xin, J.; Zheng, Z.; Wu, H. Omiganan-Based Synthetic Antimicrobial Peptides for the Healthcare of Infectious Endophthalmitis. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2024, 10, 7217–7226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Castaño, G.P.; Rosenau, F.; Ständker, L.; Firacative, C. Antimicrobial Peptides: Avant-Garde Antifungal Agents to Fight against Medically Important Candida Species. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.-L.; Jiang, A.-M.; Ma, Z.-Y.; Li, X.-B.; Xiong, Y.-Y.; Dou, J.-F.; Wang, J.-F. The Synthetic Antimicrobial Peptide Pexiganan and Its Nanoparticles (PNPs) Exhibit the Anti-Helicobacter pylori Activity in Vitro and in Vivo. Molecules 2015, 20, 3972–3985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottler, L.M.; Ramamoorthy, A. Structure, Membrane Orientation, Mechanism, and Function of Pexiganan—A Highly Potent Antimicrobial Peptide Designed from Magainin. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Biomembr. 2009, 1788, 1680–1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Hao, Y.; Yang, N.; Mao, R.; Teng, D.; Wang, J. Plectasin: From Evolution to Truncation, Expression, and Better Druggability. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1304825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.Q.; Hady, W.A.; Deslandes, A.; Rey, A.; Fraisse, L.; Kristensen, H.; Yeaman, M.R.; Bayer, A.S. Efficacy of NZ2114, a Novel Plectasin-Derived Cationic Antimicrobial Peptide Antibiotic, in Experimental Endocarditis Due to Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2011, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneider, T.; Kruse, T.; Wimmer, R.; Wiedemann, I.; Sass, V.; Pag, U.; Jansen, A.; Nielsen, A.K.; Mygind, P.H.; Raventós, D.S.; Neve, S.; Ravn, B.; Bonvin, A.M.; De Maria, L.; Andersen, A.S.; Gammelgaard, L.K.; Sahl, H.G.; Kristensen, H.H. Plectasin, a Fungal Defensin, Targets the Bacterial Cell Wall Precursor Lipid II. Science 2010, 328, 1168–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sader, H.S.; Dale, G.E.; Rhomberg, P.R.; Flamm, R.K. Antimicrobial Activity of Murepavadin Tested against Clinical Isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa from the United States, Europe, and China. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2018, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Gros, J.; Cajal, Y.; Marqués, A.M.; Rabanal, F. Synthesis of the Antimicrobial Peptide Murepavadin Using Novel Coupling Agents. Biomolecules 2024, 14, 526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernández-García, M.; Barbero-Herranz, R.; Bastón-Paz, N.; Díez-Aguilar, M.; López-Collazo, E.; Márquez-Garrido, F.J.; Hernández-Pérez, J.M.; Baquero, F.; Ekkelenkamp, M.B.; Fluit, A.C.; Fuentes-Valverde, V.; Moscoso, M.; Bou, G.; del Campo, R.; Cantón, R.; Avendaño-Ortiz, J. Unravelling the Mechanisms Causing Murepavadin Resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: Lipopolysaccharide Alterations and Its Consequences. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2024, 14, 1446626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Liu, X.; Song, Y.; Liu, Z.; Tang, X.; Tan, H. LC-AMP-I1, a Novel Venom-Derived Antimicrobial Peptide from the Wolf Spider Lycosa coelestis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2025, 69, e00424-24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohtsuka, Y.; Inagaki, H. In Silico Identification and Functional Validation of Linear Cationic α-Helical Antimicrobial Peptides in the Ascidian Ciona intestinalis. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 12619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Wang, J.; Liu, X.; Yu, S.; Tang, X.; Tan, H. LC-AMP-F1 Derived from the Venom of the Wolf Spider Lycosa coelestis, Exhibits Antimicrobial and Antibiofilm Activities. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jangra, M.; Travin, D.Y.; Aleksandrova, E.V.; Kaur, M.; Darwish, L.; Koteva, K.; Klepacki, D.; Wang, W.; Tiffany, M.; Sokaribo, A.; Chen, X.; Deng, Z.; Tao, M.; Coombes, B.K.; Vázquez-Laslop, N.; Polikanov, Y.S.; Mankin, A.S.; Wright, G.D. A Broad-Spectrum Lasso Peptide Antibiotic Targeting the Bacterial Ribosome. Nature 2025, 640, 1022–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, K.M.; Gadewar, C.K. Lariocidin A: A Promising Frontier in the Battle Against Antimicrobial Resistance—A Comprehensive Review. Int. J. Innov. Res. Technol. 2025, 11, 5098. [Google Scholar]

- Deslouches, B.; Steckbeck, J.D.; Craigo, J.K.; Doi, Y.; Mietzner, T.A.; Montelaro, R.C. Rational Design of Engineered Cationic Antimicrobial Peptides Consisting Exclusively of Arginine and Tryptophan, and Their Activity against Multidrug-Resistant Pathogens. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2013, 57, 2511–2521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buccini, D.F.; Cardoso, M.H.; Franco, O.L. Antimicrobial Peptides and Cell-Penetrating Peptides for Treating Intracellular Bacterial Infections. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2021, 10, 612931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernández-Aristizábal, I.; Ocampo-Ibáñez, I.D. Antimicrobial Peptides with Antibacterial Activity against Vancomycin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Strains: Classification, Structures, and Mechanisms of Action. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 7927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, Z.Y.; Cheng, J.; Huang, Y.; Xu, K.; Ji, Z.; Fan, W.; Yang, Y.Y. Effect of Stereochemistry, Chain Length and Sequence Pattern on Antimicrobial Properties of Short Synthetic β-Sheet Forming Peptide Amphiphiles. Biomaterials 2014, 35, 1315–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.Y.; Li, S.; Han, Y.L.; Shi, Y.F.; Wu, Y.Y.; Cheng, J.; Wang, C.Y.; Zhou, X.Y.; Zhang, Y.X. De novo-designed amphiphilic α-helical peptide Z2 exhibits broad-spectrum antimicrobial, anti-biofilm, and anti-inflammatory efficacy in acute Pseudomonas aeruginosa pneumonia. Bioorg. Chem. 2025, 157, 108309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pashinina, O.A.; Kartashova, O.L.; Pashkova, T.M.; Gritsenko, V.A. Influence of ZP2 Peptide, a Synthetic Analogue of the GM-GSF Active Center, on the Anticytokine Activity of Bacteria from Enterococcus Genus and Their Ability to Produce Cytokine-Like Substances. Russ. J. Immunol. 2022, 25, 477–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishio, S.; Emori, C.; Wiseman, B.; Fahrenkamp, D.; Dioguardi, E.; Zamora-Caballero, S.; Bokhove, M.; Han, L.; Stsiapanava, A.; Algarra, B.; Lu, Y.; Kodani, M.; Bainbridge, R.E.; Komondor, K.M.; Carlson, A.E.; Landreh, M.; de Sanctis, D.; Yasumasu, S.; Ikawa, M.; Jovine, L. ZP2 Cleavage Blocks Polyspermy by Modulating the Architecture of the Egg Coat. Cell. 2024, 187, 1440–1459.e24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kogoniya, L.M.; Orlova, R.V. Glutoxim: new about known. Supportive Therapy in Oncology (In Russ.). 2024, 1, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bugaev, P.A.; Basharin, V.A.; Antushevich, A.E. Comparative Effectiveness of Molixan and Glutoxim in the Model of Toxic Liver Lesions with Anti-Tuberculosis Drugs. Rev. Clin. Pharmacol. Drug Ther. 2019, 17, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Q.-L.; Zhang, Z.-X.; Zhang, T.; Dong, C.-M. Research Progress on the Defensin Acipensins1. Microenvironment Microecol. Res. 2022, 4, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamova, O.V.; Orlov, D.S.; Balandin, S.V.; Shramova, E.I.; Tsvetkova, E.V.; Panteleev, P.V.; Leonova, Y.F.; Tagaev, A.A.; Kokryakov, V.N.; Ovchinnikova, T.V. Acipensins—Novel Antimicrobial Peptides from Leukocytes of the Russian SturgeonAcipenser gueldenstaedtii. Acta Naturae 2014, 6, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talapko, J.; Meštrović, T.; Juzbašić, M.; Tomas, M.; Erić, S.; Horvat Aleksijević, L.; Bekić, S.; Schwarz, D.; Matić, S.; Neuberg, M.; Škrlec, I. Antimicrobial Peptides—Mechanisms of Action, Antimicrobial Effects and Clinical Applications. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, G.; Baeder, D.Y.; Regoes, R.R.; Rolff, J. Combination Effects of Antimicrobial Peptides. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2016, 60, 1717–1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeeq, M.; Li, Y.; Wang, C.; Hou, F.; Zuo, J.; Xiong, P. Unlocking the Power of Antimicrobial Peptides: Advances in Production, Optimization, and Therapeutics. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2025, 15, 1528583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bizzotto, E.; Zampieri, G.; Treu, L.; Filannino, P.; Di Cagno, R.; Campanaro, S. Classification of Bioactive Peptides: A Systematic Benchmark of Models and Encodings. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2024, 23, 2442–2452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jandhyala, S.M.; Talukdar, R.; Subramanyam, C.; Vuyyuru, H.; Sasikala, M.; Nageshwar Reddy, D. Role of the normal gut microbiota. World Journal of Gastroenterology 2015, 21, 8787–8803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kastl, A.J., Jr.; Terry, N.A.; Wu, G.D.; Albenberg, L.G. The Structure and Function of the Human Small Intestinal Microbiota: Current Understanding and Future Directions. Cell. Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 9, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemente, J.C.; Ursell, L.K.; Parfrey, L.W.; Knight, R. The Impact of the Gut Microbiota on Human Health: An Integrative View. Cell. 2012, 148, 1258–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuliani, A.; Pirri, G.; Rinaldi, A.C. Antimicrobial Peptides: The LPS Connection. Methods Mol. Biol. 2010, 618, 137–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez, A.; Pucket, B.; Engevik, M.A. Bifidobacterium and the Intestinal Mucus Layer. Microbiome Res. Rep. 2023, 2, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heimlich, D.R.; Harrison, A.; Mason, K.M. Host Antimicrobial Peptides in Bacterial Homeostasis and Pathogenesis of Disease. Antibiotics 2014, 3, 645–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cazorla, S.I.; Maldonado-Galdeano, C.; Weill, R.; De Paula, J.; Perdigón, G.D.V. Oral Administration of Probiotics Increases Paneth Cells and Intestinal Antimicrobial Activity. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnstone, K.F.; Herzberg, M.C. Antimicrobial Peptides: Defending the Mucosal Epithelial Barrier. Front. Oral Health 2022, 3, 958480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, X.; Jin, M.; Xu, C.; Gao, Y.; Yang, Y.; Qi, H.; Zhang, Q.; Yang, X.; Ya, W.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, R. FABP4 in Paneth Cells Regulates Antimicrobial Protein Expression to Reprogram Gut Microbiota. Gut Microbes 2022, 14, 2139978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lehrer, R.I.; Bevins, C.L.; Ganz, T. Defensins and Other Antimicrobial Peptides and Proteins. In Mucosal Immunology, 3rd ed.; Mestecky, J., Lamm, M.E., Ogra, P.L., Strober, W., Bienenstock, J., McGhee, J.R., Mayer, L., Eds.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2005; pp. 95–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.; Zong, X.; Jin, M.; Min, J.; Wang, F.; Wang, Y. Mechanisms and Regulation of Defensins in Host Defense. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chairatana, P.; Nolan, E.M. Human α-Defensin 6: A Small Peptide That Self-Assembles and Protects the Host by Entangling Microbes. Acc. Chem. Res. 2017, 50, 960–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sankaran-Walters, S.; Hart, R.; Dills, C. Guardians of the Gut: Enteric Defensins. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunliffe, R.N. α-Defensins in the Gastrointestinal Tract. Mol. Immunol. 2003, 40, 463–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehmann, D.; Wendler, J.; Koeninger, L.; Larsen, I.S.; Klag, T.; Berger, J.; Marette, A.; Schaller, M.; Stange, E.F.; Malek, N.P.; Jensen, B.A.H.; Wehkamp, J. Paneth Cell α-Defensins HD-5 and HD-6 Display Differential Degradation into Active Antimicrobial Fragments. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 3746–3751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cieślik, M.; Bagińska, N.; Andrzej Górski, A.; Jończyk-Matysiak, E. Human β-Defensin 2 and Its Postulated Role in Modulation of the Immune Response. Cells 2021, 10, 2991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esther, R.C.; Chadee, K. Antimicrobial Human β-Defensins in the Colon and Their Role in Infectious and Non-Infectious Diseases. Pathogens 2013, 2, 177–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danielian, A.; Danielian, M.; Y. Cheng, M.; Burton, J.; S. Han, P.; Kerr, R.P.R. Antiaging Effects of Topical Defensins. Facial Plastic Surgery Clinics of North America 2023, 31, 535–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, A.E.; C Fleming, D.; Critchley, H.; Kelly, W.R. Differential Expression of the Natural Antimicrobials, Beta-Defensins 3 and 4, in Human Endometrium. Journal of Reproductive Immunology 2003, 59, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riedl, S.; Zweytick, D.; Lohner, K. Membrane-active host defense peptides—challenges and perspectives for the development of novel anticancer drugs. Chemistry and Physics of Lipids 2011, 164, 766–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, J.; Liang, S.; Guo, X.K.; Hu, X. α-Defensins Promote Bacteroides Colonization on Mucosal Reservoir to Prevent Antibiotic-Induced Dysbiosis. Frontiers in Immunology 2020, 11, 2065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duplantier, A.J.; van Hoek, M.L. The Human Cathelicidin Antimicrobial Peptide LL-37 as a Potential Treatment for Polymicrobial Infected Wounds. Front. Immunol. 2013, 4, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nijnik, A.; Hancock, R.E.W. The Roles of Cathelicidin LL-37 in Immune Defences and Novel Clinical Applications. Curr. Opin. Hematol. 2009, 16, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Angarita, A.; Aragón, C.C.; Tobón, G.J. Cathelicidin LL-37: A New Important Molecule in the Pathophysiology of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. J. Transl. Autoimmun. 2020, 3, 100029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pahar, B.; Madonna, S.; Das, A.; Albanesi, C.; Girolomoni, G. Immunomodulatory Role of the Antimicrobial LL-37 Peptide in Autoimmune Diseases and Viral Infections. Vaccines 2020, 8, 517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Good, D.; Mosaiab, T.; Liu, W.; Ni, G.; Kaur, J.; Liu, X.; Jessop, C.; Yang, L.; Fadhil, R.; Yi, Z.; Wei, M.Q. Significance of LL-37 on Immunomodulation and Disease Outcome. Biomed. Res. Int. 2020, 2020, 349712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verjans, E.T.; Zels, S.; Luyten, W.; Landuyt, B.; Schoofs, L. Molecular Mechanisms of LL-37-Induced Receptor Activation: An Overview. Peptides 2016, 85, 16–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otte, J.-M.; Zdebik, A.-E.; Brand, S.; Chromik, A.M.; Strauss, S.; Schmitz, F.; Steinstraesser, L.; Schmidt, W.E. Effects of the cathelicidin LL-37 on intestinal epithelial barrier integrity. Regul. Pept. 2009, 156, 104–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, N.; Zhang, W.; Chen, X.; Qiu, G.; Shen, Y. Cathelicidin LL-37 in periodontitis: Current research advances and future prospects—A review. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2025, 150, 114277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinipardaz, Z.; Zhong, J.M.; Yang, S. Regulation of LL-37 in Bone and Periodontium Regeneration. Life 2022, 12, 1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaishnava, S.; Yamamoto, M.; Severson, K.M.; Ruhn, K.A.; Yu, X.; Koren, O.; Ley, R.; Wakeland, E.K.; Hooper, L.V. The antibacterial lectin RegIIIγ promotes the spatial segregation of microbiota and host in the intestine. Science 2011, 334, 255–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, J.H.; Seeley, R.J. Reg3 Proteins as Gut Hormones? Endocrinology. 2019, 160, 1506–1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Z.; Pang, W.; Zha, X.; Liu, Y.; Liu, S.; Xiao, F.; Wang, X.; Zhou, J.; Wang, W.; Liu, X. REG/Reg Family Proteins: Mediating Gut Microbiota Homeostasis and Implications in Digestive Diseases. Gut Microbes 2025, 17, 2568055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Huang, X.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, F.; Sun, M.; Yang, W.; Chen, L.; Yao, S.; Peniche, A.; Dann, S.M.; Sun, J.; Golovko, G.; Fofanov, Y.; Miao, Y.; Liu, Z.; Chen, D.; Cong, Y. Interleukin-33 Promotes REG3γ Expression in Intestinal Epithelial Cells and Regulates Gut Microbiota. Cell. Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 8, 21–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, J.H.; Bozadjieva-Kramer, N.; Seeley, R.J. Reg3γ: Current Understanding and Future Therapeutic Opportunities in Metabolic Disease. Exp. Mol. Med. 2023, 55, 1672–1677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Docampo, M.D.; Auletta, J.J.; Jenq, R.R. Emerging Influence of the Intestinal Microbiota during Allogeneic Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation: Control the Gut and the Body Will Follow. Biol. Blood Marrow Transplant. 2015, 21, 1360–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, S.; Zheng, H.; Derebe, M.G.; Callenberg, K.M.; Partch, C.L.; Rollins, D.; Propheter, D.C.; Rizo, J.; Grabe, M.; Jiang, Q.X.; Hooper, L.V. Antibacterial Membrane Attack by a Pore-Forming Intestinal C-Type Lectin. Nature 2014, 505, 103–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, A.; Huang, C.; Wang, X.; Zhou, R.; Hao, W.; Lin, Q. The Reg Protein Family: Potential New Targets for the Treatment of Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Colorectal Cancer. Front. Gastroenterol. 2024, 3, 1386069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muniz, L.R.; Knosp, C.; Yeretssian, G. Intestinal antimicrobial peptides during homeostasis, infection, and disease. Front Immunol. 2012, 3, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ra, Y.E.; Bang, Y.J. Balancing Act of the Intestinal Antimicrobial Proteins on Gut Microbiota and Health. J. Microbiol. 2024, 62, 167–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ostaff, M.J.; Stange, E.F.; Wehkamp, J. Antimicrobial Peptides and Gut Microbiota in Homeostasis and Pathology. EMBO Mol. Med. 2013, 5, 1465–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zong, X.; Fu, J.; Xu, B.; Wang, Y.; Jin, M. Interplay between Gut Microbiota and Antimicrobial Peptides. Anim. Nutr. 2020, 6, 389–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Chen, F.; Wu, W.; Sun, M.; Bilotta, A.J.; Yao, S.; Yi Xiao, Y.; Huang, X.; D Eaves-Pyles, T.; Golovko, G.; Fofanov, Y.; D’Souza, W.; Zhao, Q.; Liu, Z.; Cong, Y. GPR43 Mediates Microbiota Metabolite SCFA Regulation of Antimicrobial Peptide Expression in Intestinal Epithelial Cells via Activation of mTOR and STAT3. Mucosal Immunol. 2018, 11, 752–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khlystova, K.A.; Sarkisyan, N.G.; Kataeva, N.N. Natural and Synthetic Peptides in Antimicrobial Therapy. Russ. J. Immunol. 2023, 26, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abaturov, A.; Kryuchko, T.; Lezhenko, G. The Drugs Based on Molecular Structures of Antimicrobial Peptides and Their Therapeutic Potential in the Treatment of Infectious Diseases of the Respiratory Tract (Part 1). Child’s Health. 2021, 12, 925–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, D. Novel Natural and Synthetic Anticandidal Therapeutic Peptides to Combat Drug-Resistant Infections. Med. Sci. Forum 2024, 24, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loffredo, M.R.; Nencioni, L.; Mangoni, M.L.; Casciaro, B. Antimicrobial Peptides for Novel Antiviral Strategies in the Current Post-COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Pept. Sci. 2023, 29, e3534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pirtskhalava, M.; Amstrong, A.A.; Grigolava, M.; Chubinidze, M.; Alimbarashvili, E.; Vishnepolsky, B.; Gabrielian, A.; Rosenthal, A.; Hurt, D.E.; Tartakovsky, M. DBAASP v3: Database of Antimicrobial/Cytotoxic Activity and Structure of Peptides as a Resource for Development of New Therapeutics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, D288–D297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dilawari, R.; Chaubey, G.K.; Priyadarshi, N.; Barik, M.; Parmar, N. Antimicrobial Peptides: Structure, Function, Mechanism of Action and Therapeutic Applications in Human Diseases. Explor. Drug Sci. 2025, 3, 1008110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzain, M.; Daghistani, H.; Shamrani, T.; Almoghrabi, Y.; Daghistani, Y.; Alharbi, O.S.; Sait, A.M.; Mufrrih, M.; Alhazmi, W.; Alqarni, M.A.; Saleh, B.H.; Zubair, M.A.; Juma, N.A.; Niyazi, H.A.; Niyazi, H.A.; Halabi, W.S.; Altalhi, R.; Kazmi, I.; Altayb, H.N.; Ibrahem, K.; Alfadil, A. Antimicrobial Peptides: Mechanisms, Applications, and Therapeutic Potential. Infect. Drug Resist. 2025, 18, 4385–4426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Wang, Q.; Ren, K.; Xu, T.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, M.; Rao, Z.; Zhang, X. A Review of Antimicrobial Peptides: Structure, Mechanism of Action, and Molecular Optimization Strategies. Fermentation 2024, 10, 540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guith, T.; Gourishetti, K.; Banerjee, P.; Ghosh, N.; Rana, M.; Chatterjee, G.; Biswas, S.; Bagchi, D.; Roy, S.; Das, A. An overview of antimicrobial peptides. In Viral, Parasitic, Bacterial, and Fungal Infections, 2nd ed.; Bagchi, D., Das, A., Downs, D.W., Eds.; Academic Press: London, UK, 2023; Volume 3, pp. 101–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohlenkamp, C.; Geiger, O. Bacterial membrane lipids: diversity in structures and pathways. FEMS Microbiology Reviews 2016, 40, 133–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Ma, X.; Peng, F.; Wen, J.; Allahou, L.W.; Williams, G.R.; Knowles, J.C.; Poma, A. Advances in antimicrobial peptides: From mechanistic insights to chemical modifications. Biotechnology Advances 2025, 81, 108570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marciano, C.L.; Félix de Lima, J.V.; Couto Rosa, M.S.d.; do Nascimento, R.A.; Ferraz, A.d.O.; Silva, I.C.d.; Chrysostomo-Massaro, T.N.; Rosa-Garzon, N.G.d.; Cabral, H. A Comprehensive Overview of Antimicrobial Peptides: Broad-Spectrum Activity, Computational Approaches, and Applications. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontanot, A.; Ellinger, I.; Unger, W.W.J.; Hays, J.P. A Comprehensive Review of Recent Research into the Effects of Antimicrobial Peptides on Biofilms—January 2020 to September 2023. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xuan, J.; Feng, W.; Wang, J.; Wang, R.; Zhang, B.; Bo, L.; Chen, Z.-S.; Yang, H.; Sun, L. Antimicrobial Peptides for Combating Drug-Resistant Bacterial Infections. Drug Resistance Updates 2023, 68, 100954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gan, B.H.; Gaynord, J.; Rowe, S.M.; Deingruber, T.; Spring, D.R. The Multifaceted Nature of Antimicrobial Peptides: Current Synthetic Chemistry Approaches and Future Directions. Chemical Society Reviews 2021, 50, 7820–7880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mwangi, J.; Kamau, P.M.; Thuku, R.C.; Lai, R. Design methods for antimicrobial peptides with improved performance. Zoological Research 2023, 44, 1095–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitra, S.; Chen, M.-T.; Stedman, F.; Hernandez, J.; Kumble, G.; Kang, X.; Zhang, C.; Tang, G.; Reed, I.; Daugherty, I.Q.; Liu, W.; Klucznik, K.R.; Ocloo, J.L.; Li, A.A.; Klousnitzer, J.; Heinrich, F.; Deslouches, B.; Tristram-Nagle, S. Cyclization of Two Antimicrobial Peptides Improves Their Activity. ACS Omega 2025, 10, 9728–9740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijksteel, G.S.; Ulrich, M.M.W.; Middelkoop, E.; Boekema, B.K.H.L. Review: Lessons learned from clinical trials using antimicrobial peptides (AMPs). Frontiers in Microbiology. 2021, 12, 616979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masihi, K.N.; Schäfer, H. Overview of biologic response modifiers in infectious disease. Infectious Disease Clinics of North America 2011, 25, 723–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Costa, J.P.; Cova, M.; Ferreira, R.; Vitorino, R. Antimicrobial peptides: An alternative for innovative medicines? Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology 2015, 99, 2023–2040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Yang, M. Antimicrobial Peptides: From Design to Clinical Application. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.-J.; Nam, S.H.; Lee, B.-J. Engineering Approaches for the Development of Antimicrobial Peptide-Based Antibiotics. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Xu, H.; Xia, J.; Ma, J.; Xu, J.; Li, Y.; Feng, J. D- and Unnatural Amino Acid Substituted Antimicrobial Peptides withImproved Proteolytic Resistance and Their Proteolytic Degradation Characteristics. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 563030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapil, S.; Sharma, V. d-Amino Acids in Antimicrobial Peptides: A Potential Approach to Treat and Combat Antimicrobial Resistance. Can. J. Microbiol. 2021, 67, 119–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, J.; Zhang, X.; Liu, Y.; Geng, Z.; Dai, J.; Guo, Y. Rational Design and Synthesis of Potent Active Antimicrobial Peptides Based on American Oyster Defensin Analogue A3. RSC Adv. 2025, 15, 19954–19965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Song, Z.; Tan, Z.; Cheng, J. Recent Advances in Design of Antimicrobial Peptides and Polypeptides toward Clinical Translation. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2021, 170, 261–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCarver, S.J.; Qiao, J.X.; Carpenter, J.; Borzilleri, R.M.; Poss, M.A.; Eastgate, M.D.; Miller, M.M.; MacMillan, D.W.C. Decarboxylative Peptide Macrocyclization through Photoredox Catalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 728–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, P.; Pang, W.-K.; Xuan, S.; Chan, W.-L.; Leung, K.C.-F. Recent Advances in Peptide Macrocyclization Strategies. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2024, 53, 11725–11771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicente-Garcia, C.; Colomer, I. Lipopeptides as Tools in Catalysis, Supramolecular, Materials and Medicinal Chemistry. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2023, 7, 710–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rounds, T.; Straus, S.K. Lipidation of Antimicrobial Peptides as a Design Strategy for Future Alternatives to Antibiotics. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 9692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makowska, M.; Kosikowska-Adamus, P.; Zdrowowicz, M.; Wyrzykowski, D.; Prahl, A.; Sikorska, E. Lipidation of Naturally Occurring α-Helical Antimicrobial Peptides as a Promising Strategy for Drug Design. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 3951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allison, J.R.; Müller, M.; van Gunsteren, W.F. A Comparison of the Different Helices Adopted by α- and β-Peptides Suggests Different Reasons for Their Stability. Protein Sci. 2010, 19, 2186–2195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shankar, S.; Ur Rahim, J.; Rai, R. Self-Assembly in Peptides Containing β- and γ-Amino Acids. Curr. Protein Pept. Sci. 2020, 21, 584–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobo-Ruiz, A.; Tulla-Puche, J. Synthetic Approaches of Naturally and Rationally Designed Peptides and Peptidomimetics. Peptide Applications in Biomedicine, Biotechnology and Bioengineering 2018, 23–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guha, S.; Majumder, K. Comprehensive Review of γ-Glutamyl Peptides (γ-GPs) and Their Effect on Inflammation Concerning Cardiovascular Health. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2022, 70, 7851–7870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piller, P.; Wolinski, H.; Cordfunke, R.A.; Drijfhout, J.W.; Keller, S.; Lohner, K.; Malanovic, N. Membrane Activity of LL-37 Derived Antimicrobial Peptides against Enterococcus hirae: Superiority of SAAP-148 over OP-145. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voronko, O.E.; Khotina, V.A.; Kashirskikh, D.A.; Lee, A.A.; Gasanov, V.A.o. Antimicrobial Peptides of the Cathelicidin Family: Focus on LL-37 and Its Modifications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 8103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ridyard, K.E.; Overhage, J. The Potential of Human Peptide LL-37 as an Antimicrobial and Anti-Biofilm Agent. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Qin, J.; Huang, Y.; Kang, X.; Wei, J.; Peng, J.; Chen, J. The Antimicrobial Effects of PLGA Microspheres Containing the Antimicrobial Peptide OP-145 on Clinically Isolated Pathogens in Bone Infections. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 14541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costanzo, M.; De Giglio, M.A.R.; Gilhen-Baker, M.; et al. The chemical basis of seawater therapies: a review. En-viron. Chem. Lett. 2024, 22, 2133–2149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicidomini, C.; Roviello, G.N. Therapeutic Convergence in Neurodegeneration: Natural Products, Drug Repur-posing, and Biomolecular Targets. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costanzo, M.; Roviello, G.N. Precision Therapeutics Through Bioactive Compounds: Metabolic Reprogramming, Omics Integration, and Drug Repurposing Strategies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 10047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sargsyan, T.; Simonyan, H.M.; Stepanyan, L.; Tsaturyan, A.; Vicidomini, C.; Pastore, R.; Guerra, G.; Roviello, G.N. Neuroprotective Properties of Clove (Syzygium aromaticum): State of the Art and Future Pharmaceutical Applica-tions for Alzheimer’s Disease. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roviello, G.N. The Multifunctional Role of Salix spp.: Linking Phytoremediation, Forest Therapy, and Phyto-medicine for Environmental and Human Benefits. Forests 2025, 16, 1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roviello, G.N. Nature-Inspired Pathogen and Cancer Protein Covalent Inhibitors: From Plants and Other Natu-ral Sources to Drug Development. Pathogens 2025, 14, 1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrara, B.T.; Thompson, E.P.; Roviello, G.N.; Gale, T.F. C-Terminal Analogues of Camostat Retain TMPRSS2 Protease Inhibition: New Synthetic Directions for Antiviral Repurposing of Guanidinium-Based Drugs in Res-piratory Infections. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 6761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scognamiglio, P.L.; Tesauro, D.; Roviello, G.N. Metallogels as Supramolecular Platforms for Biomedical Appli-cations: A Review. Processes 2025, 13, 3671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fik-Jaskółka, M.A.; Mkrtchyan, A.F.; Saghyan, A.S.; Palumbo, R.; Belter, A.; Hayriyan, L.A.; Simonyan, H.; Rovi-ello, V.; Roviello, G.N. Spectroscopic and SEM evidences for G4-DNA binding by a synthetic alkyne-containing amino acid with anticancer activity. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2020, 229, 117884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roviello, V.; Musumeci, D.; Mokhir, A.; Roviello, G.N. Evidence of protein binding by a nucleopeptide based on a thymine-decorated L-diaminopropanoic acid through CD and in silico studies. Curr. Med. Chem. 2021, 28, 5004–5015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzano, M.; Falanga, A.P.; Marasco, D.; Borbone, N.; D’Errico, S.; Piccialli, G.; Roviello, G.N.; Oliviero, G. Eval-uation of an Analogue of the Marine ε-PLL Peptide as a Ligand of G-quadruplex DNA Structures. Mar. Drugs 2020, 18, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roviello, G.N.; Ricci, A.; Buccia, E.M.; Pedone, C. Synthesis, biological evaluation and supramolecular assembly of novel analogues of peptidyl nucleosides. Mol. BioSyst. 2011, 7, 1331–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roviello, G.N.; Musumeci, D.; Buccia, E.M.; Pedone, C. Evidences for supramolecular organization of nucleo-peptides: synthesis, spectroscopic and biological studies of a novel dithymine L-serine tetrapeptide. Mol. BioSyst. 2011, 7, 1073–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roviello, G.; Musumeci, D.; Pedone, C.; Bucci, E.M. Synthesis, characterization and hybridization studies of an alternate nucleo-ε/γ-peptide: complexes formation with natural nucleic acids. Amino Acids 2010, 38, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musumeci, D.; Oliviero, G.; Roviello, G.N.; Bucci, E.M.; Piccialli, G. G-quadruplex-forming oligonucleotide con-jugated to magnetic nanoparticles: synthesis, characterization, and enzymatic stability assays. Bioconjug. Chem. 2012, 23, 382–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roviello, G.N.; Di Gaetano, S.; Capasso, D.; Cesarani, A.; Bucci, E.M.; Pedone, C. Synthesis, spectroscopic studies and biological activity of a novel nucleopeptide with Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase in-hibitory activity. Amino Acids 2010, 38, 1489–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sargsyan, T.; Hakobyan, H.; Mardiyan, Z.; Khachaturyan, N.; Gevorgyan, S.; Jamgaryan, S.; Gyulumyan, E.; Danghyan, Y.; Saghyan, A. Synthesis of (S)-alanyl-(S)-β-(thiazol-2-yl-carbamoyl)-α-alanine, a dipeptide con-taining it, and in vitro investigation of antifungal activity. Farmacia 2022, 70, 1148–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadayan, A.; Sargsyan, A.; Hakobyan, H.; Mardiyan, Z.; Jamharyan, S.; Hovhannisyan, N.; Sargsyan, T. Modeling, synthesis and in vitro screening of unusual amino acids and peptides as protease inhibitors. J Chem Technol Metall. 2023, 615–620. [Google Scholar]

- Sargsyan, A.S.; Sargsyan, T.H.; Hovhannisyan, N.A. Modeling, synthesis and in vitro testing of peptides based on unusual amino acids as potential antibacterial agents. Biomed. Khim 2024, 70, 413–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sargsyan, T.; Saghyan, A. The synthesis and in vitro study of 9-fluorenylmethoxycarbonyl protected non-protein amino acids antimicrobial activity. Eurasian Chem.-Technol. J. 2024, 25, 235–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadayan, A.S.; Mkrtchyan, A.F.; Poghosyan, A.S.; Dadayan, S.A.; Stepanyan, L.A.; Israyelyan, M.H.; Tovmasyan, A.S.; Tsaturyan, A.H.; Hovhannisyan, N.A.; Topuzyan, V.O.; Sargsyan, T.H.; Saghyan, A.S. Unnatural phosphorus-containing α-amino acids and their N-FMOC derivatives: Synthesis and in vitro investigation of anticholinesterase activity. ChemSelect 2024, 9, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mkrtchyan, A.F.; Hayriyan, L.A.; Karapetyan, A.J.; Tovmasyan, A.S.; Tsaturyan, A.H.; Khrustalev, V.N.; Maleev, V.I.; Saghyan, A.S. Using the Ni-[(benzylprolyl)amino]benzophenone complex in the Glaser reaction for the synthesis of bis α-amino acids. New J. Chem. 2020, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tovmasyan, A.S.; Mkrtchyan, A.F.; Khachatryan, H.N.; Hayrapetyan, M.V.; Hakobyan, R.M.; Poghosyan, A.S.; Tsaturyan, A.H.; Minasyan, E.V.; Maleev, V.I.; Larionov, V.A.; et al. Synthesis, Characterization, and Study of Catalytic Activity of Chiral Cu(II) and Ni(II) Salen Complexes in the α-Amino Acid C-α Alkylation Reaction. Molecules 2023, 28, 1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stepanyan, L.; Sargsyan, T.; Mittova, V.; Tsetskhladze, Z.R.; Motsonelidze, N.; Gorgoshidze, E.; Nova, N.; Is-rayelyan, M.; Simonyan, H.; Bisceglie, F.; et al. The synthesis, characterization, and biological evaluation of a fluorenyl-methoxycarbonyl-containing thioxo-triazole-bearing dipeptide: Antioxidant, antimicrobial, and BSA/DNA binding studies. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sargsyan, T.; Hakobyan, H.; Simonyan, H.; Soghomonyan, T.; Tsaturyan, A.; Hovhannisyan, A.; Sardaryan, S.; Saghyan, A.; Roviello, G.N. Biomacromolecular interactions and antioxidant properties of novel synthetic ami-no acids targeting DNA and serum albumin. J. Mol. Liq. 2025, 128700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saubenova, M.; Rapoport, A.; Yermekbay, Z.; Oleinikova, Y. Antimicrobial Peptides, Their Production, and Po-tential in the Fight Against Antibiotic-Resistant Pathogens. Fermentation 2025, 11, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moretta, A.; Scieuzo, C.; Petrone, A.M.; Salvia, R.; Manniello, M.D.; Franco, A.; Lucchetti, D.; Vassallo, A.; Vogel, H.; Sgambato, A.; Falabella, P. Antimicrobial Peptides: A New Hope in Biomedical and Pharmaceutical Fields. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2021, 11, 668632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gagat, P.; Ostrówka, M.; Duda-Madej, A.; Mackiewicz, P. Enhancing Antimicrobial Peptide Activity through Modifications of Charge, Hydrophobicity, and Structure. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 10821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, K.H.; Kim, K.H.; Ki, M.-R.; Pack, S.P. Antimicrobial Peptides and Their Biomedical Applications: A Review. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straus, S.K. Tryptophan- and Arginine-Rich Antimicrobial Peptides: Anti-Infectives with Great Potential. Bio-chim. Biophys. Acta Biomembr. 2024, 1866, 184260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; Tu, Y.; Li, B.; et al. Antimicrobial Peptide Biological Activity, Delivery Systems and Clinical Transla-tion: Status and Challenges. J. Transl. Med. 2025, 23, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li Petri, G.; Di Martino, S.; De Rosa, M. Peptidomimetics: An Overview of Recent Medicinal Chemistry Efforts toward the Discovery of Novel Small Molecule Inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 2022, 65, 7438–7475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezende, B.S.; Oshiro, K.G.N.; Júnior, N.G.O.; Franco, O.L.; Cardoso, M.H. Advances on chemically modified antimicrobial peptides for generating peptide antibiotics. Chemical Communications 2021, 88, 11578–11590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roque-Borda, C.A.; Zhang, Q.; Nguyen, T.P.T.; Nguyen, T.T.H.; Medhi, H.; Rodrigues, H.L.S.; Canales Carnero, C.S.; Sutherland, D.; Helmy, N.M.; Araveti, P.B.; de la Torre, B.G.; Albericio, F.; Pavan, F.R. Synergistic Combina-tions of Antimicrobial Peptides and Conventional Antibiotics: A Strategy to Delay Resistance Emergence in WHO Priority Bacteria. Pharmacol. Rev. 2025, 78, 100104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramazi, S.; Mohammadi, N.; Allahverdi, A.; Khalili, E.; Abdolmaleki, P. A review on antimicrobial peptides da-tabases and the computational tools. Database 2022, 2022, baac011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Li, X.; Wang, Z. APD3: The antimicrobial peptide database as a tool for research and education. Nu-cleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, D1087–D1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mondal, R.K.; Sen, D.; Arya, A.; Samanta, S.K. Developing anti-microbial peptide database version 1 to provide comprehensive and exhaustive resource of manually curated AMPs. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 17843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feurstein, C.; Meyer, V.; Jung, S. Structure–Activity Predictions from Computational Mining of Protein Databases to Assist Modular Design of Antimicrobial Peptides. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 812903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jenssen, H.; Hamill, P.; Hancock, R.E.W. Peptide Antimicrobial Agents. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2006, 19, 491–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fjell, C.D.; Hiss, J.A.; Hancock, R.E.W.; Schneider, G. Designing Antimicrobial Peptides: Form Follows Function. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2011, 11, 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahlapuu, M.; Håkansson, J.; Ringstad, L.; Björn, C. Antimicrobial Peptides: An Emerging Category of Thera-peutic Agents. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2016, 6, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, B.; Basu, A.; Shehadeh, F.; Felix, L.; Kollala, S.S.; Chhonker, Y.S.; Naik, M.T.; Dellis, C.; Zhang, L.; Gane-san, N.; Murry, D.J.; Gu, J.; Sherman, M.B.; Ausubel, F.M.; Sotiriadis, P.P.; Mylonakis, E. Antimicrobial Peptide Developed with Machine Learning Sequence Optimization Targets Drug-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Mice. J. Clin. Invest. 2025, 135, e185430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiradharma, N.; Khoe, U.; Hauser, C.A.; Seow, S.V.; Zhang, S.; Yang, Y.Y. Synthetic Cationic Amphiphilic α-Helical Peptides as Antimicrobial Agents. Biomaterials 2011, 32, 2204–2212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guha, R. On exploring structure–activity relationships. Methods Mol. Biol. 2013, 993, 81–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zelezetsky, I.; Tossi, A. Alpha-helical antimicrobial peptides—Using a sequence template to guide structure–activity relationship studies. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Biomembr. 2006, 1758, 1436–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maher, S.; McClean, S. Investigation of the cytotoxicity of eukaryotic and prokaryotic antimicrobial peptides in intestinal epithelial cells in vitro. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2006, 71, 1289–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Name | Sequence/structural details | Activity / Mechanism | Phase | Peptide Type | Developer | Ref. |

| CZEN-002 (CKPV)2 | (CKPV)2 | Antifungal, immunomodulatory (α-MSH analog) | IIb | Synthetic octapeptide | Zengen | [34,35] |

| HB1345 | Decanoyl-KFKWPW | Lipopeptide; membrane disruption | Pre-clinical | Synthetic (lipidated AMP) | Helix BioMedix | [36,37][ |

| hLF1-11 | GRRRRSVQWCA | Lactoferrin fragment; immune-activating | I/II | Synthetic | AM-Pharma | [38,39] |

| IMX-942 (IDR-1) | KSRIVPAIPVSLL | Innate defense regulator (IDR) | I/II | Synthetic cationic peptide | Inimex | [40,41] |

| OP-145 | LL-37 derivative | Anti-biofilm, antibacterial | II | Synthetic | OctoPlus | [40,42] |

| PAC-113 (P-113) | AKRHHGYKRKFH | Anti-Candida (histatin-5 fragment) | IIb | Semi-synthetic | Pacgen | [43,44] |

| Brilacidin | Not disclosed | Defensin-mimetic; membrane disruption | II | Peptidomimetic | Cellceutix / Innovation Pharma | [40,45,46] |

| XOMA-629 | KLFR-(d-naphtho-Ala)-QAK-(d-naphtho-Ala) | Antimicrobial activity via an immunomodulatory mechanism | IIa | Peptidomimetic | XOMA | [40,47,48] |

| Arenicin-3 | β-sheet AMP | Anti-MDR; membrane-active | Pre-clinical | Natural AMP | Adenium | [49,50] |

| RDP58 | D-amino acid decapeptide | TNF-α suppression, anti-inflammatory (immunomodulator) | II | All-D synthetic peptide | Genzyme | [51,52] |

| Iseganan (IB-367) | RGGLCYCRGRFCVCVGR-NH2 | Protegrin analog; antibacterial | III | Semi-synthetic | Ardea Biosciences | [53,54] |

| LTX-109 | Not disclosed | Membrane-active peptidomimetic | II | Peptidomimetic | Lytix Biopharma | [55,56,57] |

| Omiganan | ILRWPWWPWRRK | Indolicidin analog; anti-biofilm | II/III | Semi-synthetic | Cutanea Life Sciences | [58,59,60] |

| Pexiganan (MSI-78) | MSI-78 | Pore-forming antimicrobial | III | Semi-synthetic (magainin analog) | MacroChem | [61,62] |

| Plectasin-212 (NZ2114 class) | Defensin variant | Lipid II binding | Pre-clinical | Engineered defensin | Novozymes | [63,64,65] |

| Murepavadin (POL7080) | β-peptide | LptD inhibitor (P. aeruginosa) | Advanced clinical development (systemic use limited by toxicity) | Peptidomimetic | Polyphor | [66,67,68] |

| LC-AMP-I1 | GRMQEFIKKLK | Ultra-short AMP; MDR activity | Pre-clinical | Natural-derived (spider venom) | Chongqing University | [69,70,71] |

| Lariocidin | Lasso peptide | Pore-forming antimicrobial | Pre-clinical | Natural RiPP | Spanish research groups | [72,73] |

| WR12 | RWKIFKKIEKMGRNIR | Anti-MRSA / VRSA | Pre-clinical | Synthetic de novo peptide | Hong Kong University | [74,75,76] |

| D-IK8 | All-D peptide | Protease-resistant AMP; MDR Gram- | Pre-clinical | All-D synthetic | Korean research groups | [74,77] |

| ZP2 | Synthetic AMP | Quorum-sensing inhibition | Pre-clinical | Synthetic | Chinese research institutes | [78,79,80] |

| Glutoxim | γ-glutamyl-cysteine | Immunomodulator | Marketed | Synthetic (glutathione analog) | Pharmasyntez | [81,82] |

| Acipensin-1 | Fish-derived AMP | Membrane lysis | Pre-clinical | Natural AMP | Far East Biomedical Labs | [83,84] |

| Database | Dataset size* | Content | Website** |

| APD | 2 619 | Natural and some synthetic AMPs | https://aps.unmc.edu/AP/ |

| CAMPR4 | Natural AMPs: 11827 Synthetic AMPs: 12416 |

Collection of Anti-Microbial Peptides | https://camp.bicnirrh.res.in/ |

| DRAMP | 30260 | Data repository of antimicrobial peptides | http://dramp.cpu-bioinfor.org/ |

| BACTIBASE | 177 | Bacteriocins | http://bactibase.pfba-lab.org |

| MilkAMP | 371 | Milk bioactive peptide database | http://mbpdb.nws.oregonstate.edu/ |

| PhytAMP | 273 | Plant AMPs | https://phytamp.hammamilab.org/entrieslist.php |

| AVPdb | 2 683 | Database of antiviral peptides | http://crdd.osdd.net/servers/avpdb/ |

| HIPdb | 981 | Database of experimentally validated HIV inhibiting peptides. | http://crdd.osdd.net/servers/hipdb/index.php |

| DBAASP | ~8 000 | Database of antimicrobial activity and structure of peptides | https://dbaasp.org/home |

| Hemolytik | ~5 000 | Database of hemolytic and non-hemolytic peptides | http://crdd.osdd.net/raghava/hemolytik/ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).