1. Introduction

The human body's microbiota is conceptualized as an extracorporeal organ, exerting a diverse array of functions, notably contributing to immune responsiveness and actively engaging in the functioning of nearly all physiological systems, encompassing the digestive, immune, and central nervous systems, as well as metabolic processes [

1]. A discernible correlation has been established between the compositional makeup of the gut microbiota and the onset of cancer, particularly colorectal cancer (CRC). Qualitative and quantitative perturbations in the gut microbiota are intricately linked to manifestations of immunological imbalance, typically evidenced by the suppression of innate and humoral immunity, proliferation of lymphoid tissue, and decoupling of growth limitation and tumor tissue lysis mechanisms [

2,

3,

4,

5].

According to the literature, discernible alterations in the gut microbiota are universally experienced by all patients with CRC. Despite the somewhat conflicting data revealed in a meta-analysis concerning the microbiota and metabolome composition in CRC, a prevalent pattern emerges, characterized by a reduction in biological diversity and an elevation in the abundance of specific taxa. Notably, an increased representation of genera such as Fusobacterium, Peptostreptococcus, Bacteroides, Eubacterium, Prevotella, Clostridium, Campylobacter, and members of the family Enterobacteriaceae is frequently observed [

6,

7]. Furthermore, a significant correlation is noted between CRC and an augmented abundance of specific bacterial species, including Bacteroides fragilis, Fusobacterium nucleatum, Streptococcus spp., Parvimonas micra, and Peptostreptococcus stomatis, Enterobacter spp. [

6,

8,

9]. A significant role in the genesis of CRC play pathogenic Escherichia coli [

10], Enterococcus faecalis [

11], mucolytic bacteria Akkermansia muciniphila [

12] and inducers of cholesterol synthesis Peptostreptococcus anaerobius, stimulating the proliferation of colonocytes [

13]. Conversely, bacteria belonging to the genera Collinsella, Slackia, Faecalibacterium and Roseburia exhibit an anti-oncogenic effect [

14,

15,

16,

17,

18].

Surgical intervention, coupled with the administration of antibacterial drugs, typically results in more pronounced consequences, as evidenced by significant alterations in clinical and laboratory parameters, along with shifts in microbiota composition. These changes set the stage for severe complications, including but not limited to abdominal sepsis, pseudomembranous colitis, antibiotic-associated dysbiosis, and colitis [

19,

20].

Probiotic bacteria, such as Streptococcus faecalis, Clostridium butyricum, Bacillus mesentericus, Lactobacillus plantarum 299v, L. plantarum, L. casei, Bifidobacterium spp. (particularly, B. longum) and Saccharomyces cerevisiae have demonstrated mechanisms of antitumor protection [

19,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25]. The anticarcinogenic efficacy of probiotics is associated with the inhibition of pathogenic bacteria colonization on the gut mucosa, reinforcement of barrier functions, stimulation of mucin production, and the expression of tight junction proteins. Additionally, they foster "homeostatic" immune responses by enhancing the proliferation of Treg cells, regulating the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, and increasing apoptosis in cancer cells [

26].

According to literature data, the intake of probiotics is recommended in the complex treatment of CRC patients across all stages, encompassing the perioperative and long-term postoperative periods, as well as during and after chemoradiotherapy. Traditional therapeutic modalities, including surgery and chemoradiotherapy, exert deleterious effects on the body, notably contributing to the exacerbation of gut dysbiosis [

19,

20,

27]. Nevertheless, in instances where probiotics exhibit insufficient efficacy, rapid elimination from the gut, or lead to side effects such as acidosis, dyspepsia, and infectious complications [

28] alternative methods for rectifying clinical and laboratory parameters in CRC have been found. It our research center (The Federal State Budgetary Institution "Institute of experimental medicine") has devised a medical technology enabling the isolation of indigenous beneficial bacteria (e.g., lactobacilli, bifidobacteria, or enterococci) from gut microbiota samples for gut microbiota restoration in different group of patients, particularly in patients with CRC [

29]. The application of autoprobiotics as a personalized functional food product (PFFP) represents an innovative therapeutic approach with several advantages over the use of commercial probiotics. Key advantages of employing indigenous non-pathogenic strains of lactobacilli, bifidobacteria, and enterococci include biological compatibility with other components of the host microbiota, adaptation to the body's living conditions, minimal immune system burden, and positive effects on digestion.

The aim of this study is to assess the effectiveness and safety of autoprobiotics based on indigenous enterococci in the early postoperative period in patients with CRC.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patient’s characteristics

A total of 36 patients diagnosed with CRC were enrolled in the study. The average age of the participants was 65.1±8.9 years, with a male-to-female ratio of 2:1. Informed consent was obtained from all patients before undergoing any study procedures or therapies.

Patients were included based on main inclusion criteria: localization of CRC: left flank, age: 50-75 years, no requirement for a course of antibiotic therapy (intravenous amoxicillin on the day of surgery was permitted for preventing infectious complications). Main un-inclusion criteria were localization of CRC: Right flank, severe cardiopulmonary pathology, cachexia.

2.2. Ethical Considerations

The study received approval from the Ethics Committee of the North-Western District Scientific and Clinical Center, named after L.G. Sokolov, Federal Medical and Biological Agency, Saint-Petersburg, Russian Federation. Written informed consent, following the principles outlined in the Helsinki Declaration of the World Medical Association, was obtained from all subjects. The study adhered to the "Rules of Clinical Practice in the Russian Federation" approved by the Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation (Order No. 266, June 19, 2003) and was authorized under Federal Law N323-FL dated November 21, 2011, "On Protection of Health of Citizens in the Russian Federation". The study maintained patient confidentiality.

2.3. Study design

The first fecal sample was collected 10–14 days before surgery. Patient allocation into groups A and C, along with randomization in a 2:1 ratio (receiving autoprobiotic: without autoprobiotic, respectively), occurred before surgery. Autoprobiotic strains of Enterococcus faecium or Enterococcus hirae were isolated from fecal samples of group A patients to obtain the autoprobiotic. The study group (Group A) comprised 24 CRC patients who received autoprobiotic therapy in the early postoperative period, while the control group (Group C) included 12 CRC patients without autoprobiotic therapy. In both groups age and the proportion of male/ female subjects was the similar.

The experimental group (Group A) received autoprobiotic personalized therapy starting from the third day after surgery. Patients consumed a soy-based autoprobiotic (SUPRO PLUS 2640 DS, “Solae”, Belgium) containing 5 × 10^8 CFU/mL autoprobiotic enterococci at a dose of 100 mL per day (50 mL twice a day) for 10 days. SUPRO PLUS 2640 DS, a protein-vitamin-mineral complex, is a high-quality instant dry protein product enriched with vitamin A, iron, iodine, and zinc. It has increased biological value due to the presence of soy protein and a low content of saturated fat and cholesterol [

30].

The second fecal sample was collected upon completion of the autoprobiotic course.

In Group C, all examinations and analyses were performed at the same time intervals.

Prior to surgery and between days 14-16 post-surgery, comprehensive evaluations were conducted on all patients, encompassing the following:

Stool Analysis: Assessment of stool frequency and consistency.

-

Digestive System and Psychoemotional Status Assessment with specialized questionnaires:

Gastrointestinal Symptom Rating Scale (GSRS)

Gastrointestinal Symptom Score (GIS)

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS)

Examination of the gut microbiota.

Analysis of interleukins parameters

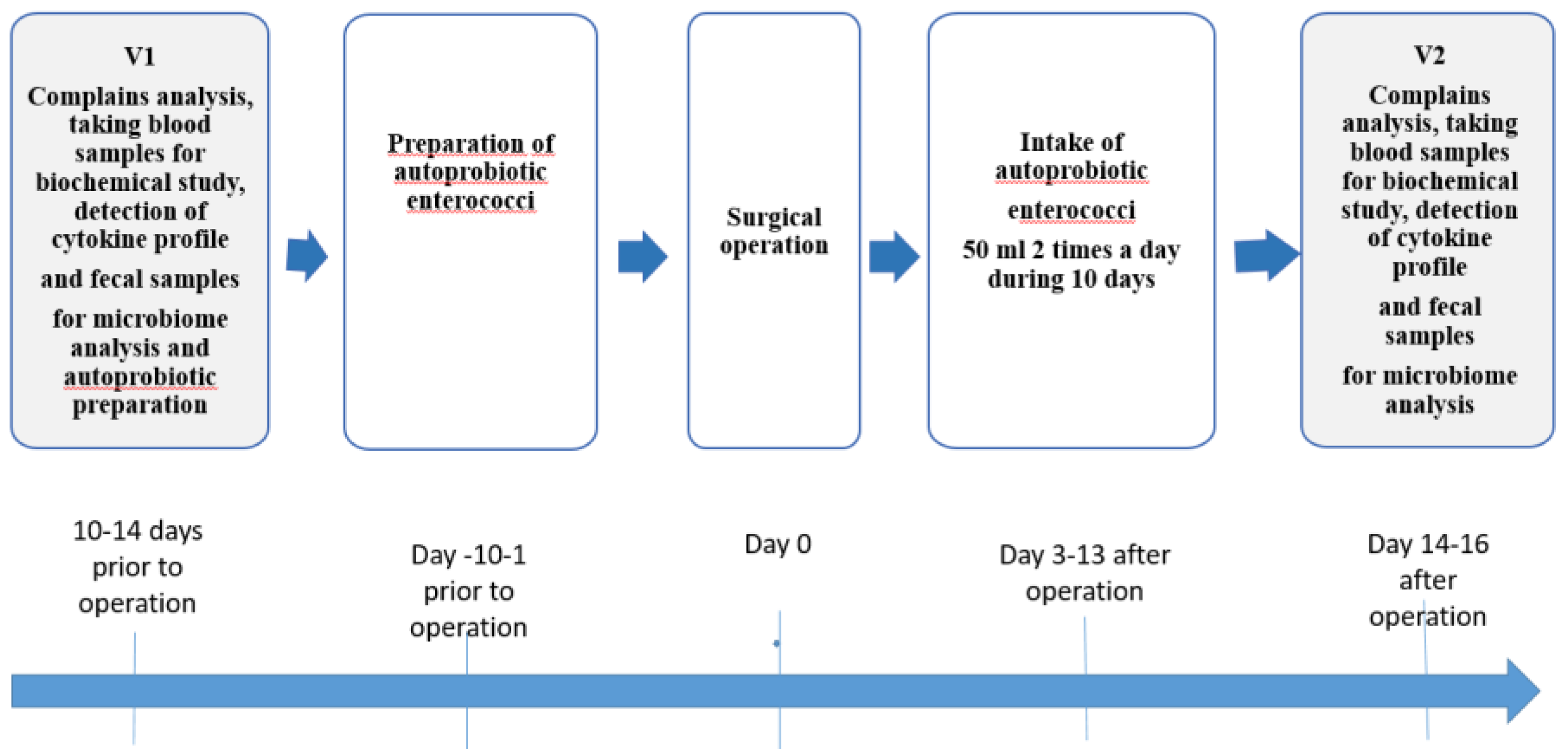

The schematic representation of the study design is depicted in

Figure 1.

The study group before the surgery was designated as AV1, and after receiving the autoprobiotic treatment it was designated as AV2, the control group before the surgery was designated as CV1, and 14-16 days after surgery - as CV2.

2.4. Autoprobiotic strains

The methodology for producing autoprobiotics based on non-pathogenic E. faecium, previously developed by our team [

31], was employed. All isolated cultures of autoprobiotic enterococci underwent species identification and were scrutinized for the presence of pathogenicity genes using a pre-established algorithm [

32]. The identification of enterococci was conducted through Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) and Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization Time-of-Flight Mass Spectrometry (MALDI-TOF).

Non-pathogenic strains of E. faecium and E. hirae, obtained from patients, were cultured in SuproPlus 2640 medium (Monsanto company, Missouri, USA, concentration 40 g/l), and subsequently, PFFP was prepared from these cultures. To isolate autoprobiotic strains of enterococci, we used fecal samples delivered to the laboratory no later than 2 h after defecation.

2.4.1. Preparation of autoprobiotic enterococci

A suspension of feces in PBS at a dilution of 1:10 was plated in an amount of 100 μL on azide agar (NICF, St. Petersburg) and cultured for 48 h at a temperature of 37 °C. Mainly enterococci grew on this selective medium. Colonies typical for E. faecium, with a pink rim and a burgundy center, were selected. Genetic characterization of the enterococci [

33,

34,

35,

36,

37] was performed employing PCR with species-specific primers and primers for identification of the virulence-related genes [

38]. A single colony of a selected, identified, pure culture of E. faecium was added to 10 mL of the culture medium SUPRO® 2649 and incubated for 48 h at 37 °C until fermentation. Then, the obtained 10 mL of starter culture was used as an inoculum to obtain 1 L of starter culture.

2.5. Questionaries

The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), developed in 1983 by Zigmond A.S and Snaith R.P. [

39], was employed as a straightforward and widely used method for evaluating anxiety and depression levels. Comprising 14 questions (7 each for anxiety and depression assessment), the scale requires 2-5 minutes for patient completion. Anxiety and depression levels are independently assessed using two subscales, where 0-7 points indicate normalcy, 8-10 points indicate subclinical expression, and 11 or more points indicate clinical expression. The maximum score for each subscale is 21 points.

The Gastrointestinal Symptom Rating Scale (GSRS), developed by the Quality of Life Department at ASTRA Hassle (Author: I. Wiklund, 1998) [

40], comprises 15 questions converted into 5 scales: abdominal pain (questions 1, 4), reflux syndrome (questions 2, 3, 5), diarrhea syndrome (questions 11, 12, 14), dyspeptic syndrome (questions 6, 7, 8, 9), constipation syndrome (questions 10, 13, 15). Additionally, points are calculated on a total measurement scale (1–15 questions). The questionnaire captures complaints that have troubled the patient in the week preceding its completion. Scores for each question range from 1 to 7, with higher scores indicating more severe symptoms of gastroenterological pathology and a lower quality of life.

The Gastrointestinal Symptoms Score (GIS) comprises 10 items assessing the degree of manifestation of a broad spectrum of gastroenterological symptoms. The severity of clinical symptoms is evaluated on a five-point Likert scale from 0 to 4, where 0 represents no symptom, 1 is mild, 2 is moderate, 3 is severe, and 4 is very severe [

41]. The maximum score on this scale is 40 points, with higher scores indicating more severe dyspepsia.

2.6. Study of the gut microbiota

2.6.1. Bacteriological study

Changes in the gut microbiota before and after therapy were tested by bacteriological analysis of the fecal samples using a previously described method [

42]. The time intervals between collection of samples and laboratory handling did not exceed 1 hour. The probes (1 g) were homogenized in 1 mL of phosphate buffered saline, PBS (8.00 g/l NaCl, 0.20 g/l KCl, 1.44 g/l Na2HPO4, 0.24 g/l KH2PO4, pH 7.4). Then the samples were diluted in 10–106 times employing method of serial dilutions. This made it possible to identify the following bacteria belonging to the genera Lactobacillus, Enterococcus, Bifidobacterium, Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia, Proteus and Klebsiella. The following selective and differential diagnostic culture media were used for the bacteriological studies: blood agar, mannitol salt agar, MacConkey’s agar, azide agar (NICF, St. Petersburg), MRS agar (Difco, USA) and Blaurock medium (Nutrient medium, Russia). These different morphotypes were isolated and submitted to microscopic examination. Microscopic examination were done by way of the gram stain procedure of pure cultures of bacteria. After enumeration of the colonies on the agar plates, three to four colonies presenting different microscopic appearances were analyzed by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry.

2.6.2. Quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR)

A quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) was performed using the kit “Colonoflor” (AlphaLab, Russia) corresponding to the set of marker colonic bacteria on the qPCR used Mini-Opticon, BioRad. This methodology enables the estimation of the total bacterial count, along with the quantification of obligate and conditionally pathogenic members of the microbiota, including but not limited to Lactobacillus spp., Bifidobacterium spp., Enterococcus spp., Escherichia coli, Escherichia coli enteropathogenic, Bacteroides fragilis, Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron, Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, Proteus mirabilis/ vulgaris, Staphylococcusaureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Klebsiella oxytoca, Candida spp., Clostridioides difficile, Clostridium perfringens, Proteus spp., Enterobacter spp., Methanobrevibacter spp., Fusobacteria spp., Akkermansia sp., Acinetobacter spp., Prevotella spp.

2.6.3. Metagenome analysis (16 S rRNA)

The metagenome analysis (16S rRNA) was performed as it was early described [

38]. Fecal samples frozen on the day of the material’s collection were used for the metagenome analysis. Libraries of hypervariable regions, V3 and V4, of the 16S rRNA gene were analyzed on MiSeq (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). DNA were isolated from feces using the kit Express-DNA-Bio (Alkor bio, St. Petersburg, Russia). The standard method recommended by Illumina based on employing two rounds of PCR was used to prepare the libraries.

2.7. Serum analysis (cytokine status)

The concentrations of cytokines alpha-TNF, IL-8, IL-10, IL-1 beta, IL-6, IL-18, MCP-1, and gamma interferon in the blood serum were determined using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay with the "Vector-Best" test system (JSC, Novosibirsk, Russia) and an ELISA analytical equipment complex (Bio-Rad, USA).

2.8. Statistical analysis

The Kolmogorov–Smirnov criterion was employed to assess the normality of data distribution, leading to the utilization of nonparametric criteria.

Statistically significant differences among groups were ascertained using the Mann–Whitney U-criterion, adjusted for multiple comparisons through the Benjamini–Hochberg method. Additionally, Wilcoxon's T-test was applied for paired samples.

For comparative analysis, the post hoc test of honestly significant difference (HSD) for unequal N was utilized in the Statistica-8 software. Differences with p < 0.05 were deemed significant. Exploring correlations between the studied parameters involved Spearman’s test via the software package Statistica 8.0 (StatSoft, Tulsa, OK, USA).

Vectors for principal component analysis (PCA) using PERMANOVA were based on OTU abundances, filtered for noise, and normalized for total OTU counts in each sample.

3. Results

3.1. Clinical data

Analysis of the frequency and consistency of stool before treatment showed that in patients with CRC with tumor localization in the left flank, there are stool disorders both diarrhea (25% of patients) and constipation (25% of patients), in 50% of patients there were no stool disorders. Analysis of the appearance of the first independent stool after surgery showed that individuals receiving an autoprobiotic had an independent stool of normal consistency (3-4 types on the Bristol scale) earlier than those who did not receive it (the stool was either 1-2 types on the Bristol scale, or 5-6 types), and also against the background of rapid normalization of stool frequency, there were low severity of flatulence in group A. This corresponded to the results described when using probiotics by other authors in the treatment of oncological diseases [

43,

44].

Patients who took treatment with autoprobiotics had a hospital stay of 5-7 days post-surgery, signifying the absence of postoperative complications.

3.1.1. Analysis of the results of the questionnaires

Evaluation of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) scores prior to treatment indicated that, in the majority of patients, anxiety and depression levels remained below acceptable values (below 7 points), despite the established colorectal cancer diagnosis. The average anxiety level was 3 points, and the average depression level was 5.4 points. An elevated level of anxiety was identified in 1 patient (9 points), while depression was observed in 3 patients (8, 8, 10 points). These findings suggest that the psychoemotional factor may not be a primary contributor to colorectal cancer development, and the short period post-diagnosis may not significantly influence the patient's psychological well-being. After autoprobiotic intake there was a clear tendency to decrease the level of anxiety. This may be explained by the fact that indigenous enterococci are capable of synthesizing hormones and neurotransmitters (serotonin, gamma-aminobutyric acid, etc.), which positively affect the central nervous system, reduce the severity of anxiety and depressive disorders and improve the quality of life [

45,

46].

Based on GIS questionnaire results, a reduction in dyspeptic symptoms was observed with autoprobiotic use post-surgery (

Figure 2).

Furthermore, GSRS questionnaire results indicated that autoprobiotic use did not exacerbate the condition or lead to increased dyspeptic complaints after surgery (

Table 1). These findings underscore the high efficacy of autoprobiotics in preventing postoperative stool disorders and dyspepsia in CRC patients.

3.1.2. Assessment of adverse events

During the administration of the autoprobiotic, only two episodes of adverse events were documented. One patient experienced transient nausea on the third day of use, resolving spontaneously within 2 days. In another patient, stool consistency shifted from type 4 on the Bristol scale to type 1-2, which normalized following dietary adjustments. No serious adverse events were recorded.

3.2. Serum analysis (cytokine status)

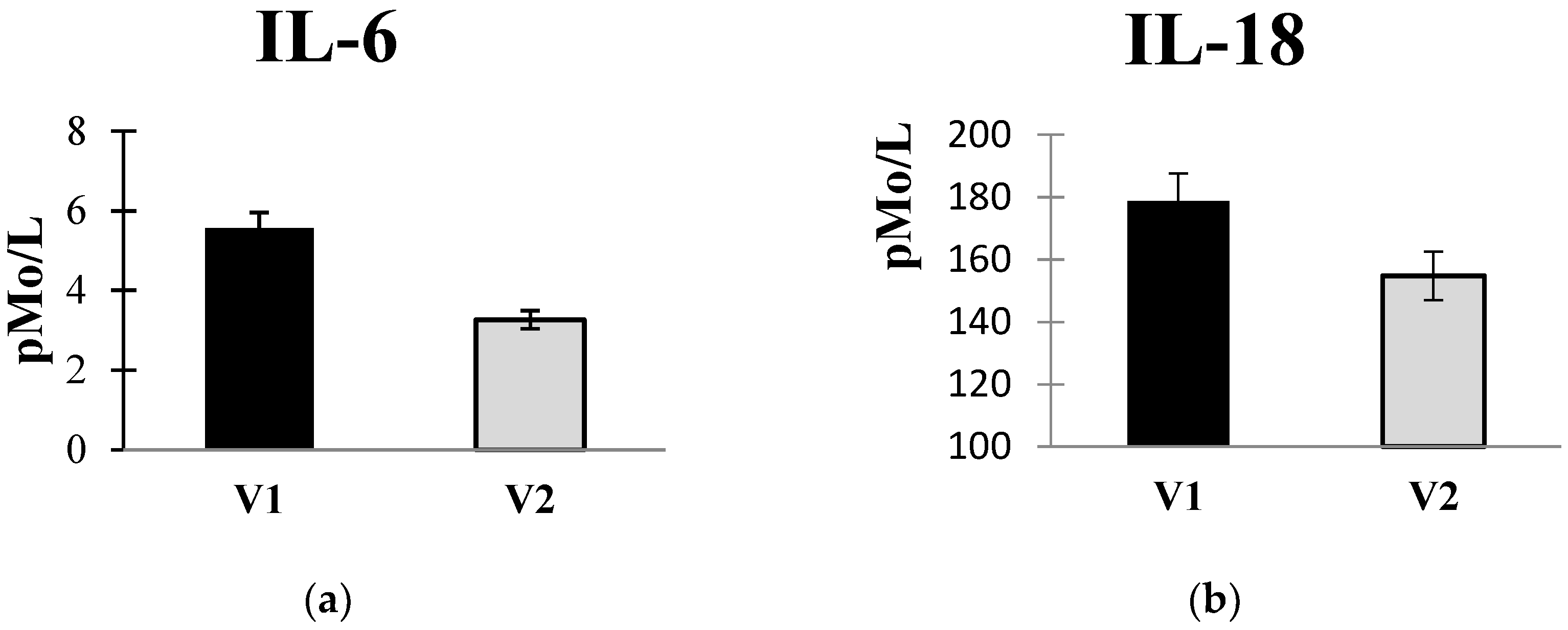

The introduction of autoprobiotics resulted in a reduction in pro-inflammatory cytokine levels in the blood serum (

Figure 3a,b). Interpretation of these findings is complex, as there is limited prior observation of changes in cytokine status in colorectal cancer patients. Major mechanisms contributing to neoplastic transformation involve disruptions in gut microbiota, synthesis of “pathological” metabolites, and the production of genotoxins by gastrointestinal bacteria. These factors lead to immune dysregulation and inflammation [

47,

48]. Pro-inflammatory cytokines and hormones play a significant role in colorectal cancer pathogenesis. Excessive human chorionic gonadotropin, a negative prognostic factor for CRC, stimulates TNFα and IL-6 hypersecretion, as well as the synthesis of IL-8 and matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), facilitating the invasion of microorganisms beyond the gut mucosa [

49,

50,

51]. Studies have reported negative prognoses for CRC with elevated IL-6 and TNFα levels in peritoneal fluid during the postoperative period [

52].

Other authors also observed an elevation in IL-6 and TNFα levels in the blood serum of colorectal cancer patients, with a subsequent decrease post-surgery by 40-60% [

49].

3.3. Cut microbiota study

3.3.1. Bacteriological study

The bacteriological study was mainly aimed to isolate non-pathogenic Enterococcus spp. for autoprobiotic production. Genetic analysis of DNA from enterococci grown on selective medium (azide agar) facilitated species identification and detection of pathogenicity and vancomycin resistance genes in the genome. Patients (24 individuals) from whom non-pathogenic E. faecium and/or E. hirae were isolated from feces were assigned to group A. E. faecalis were also isolated from fecal samples of patients with CRC.

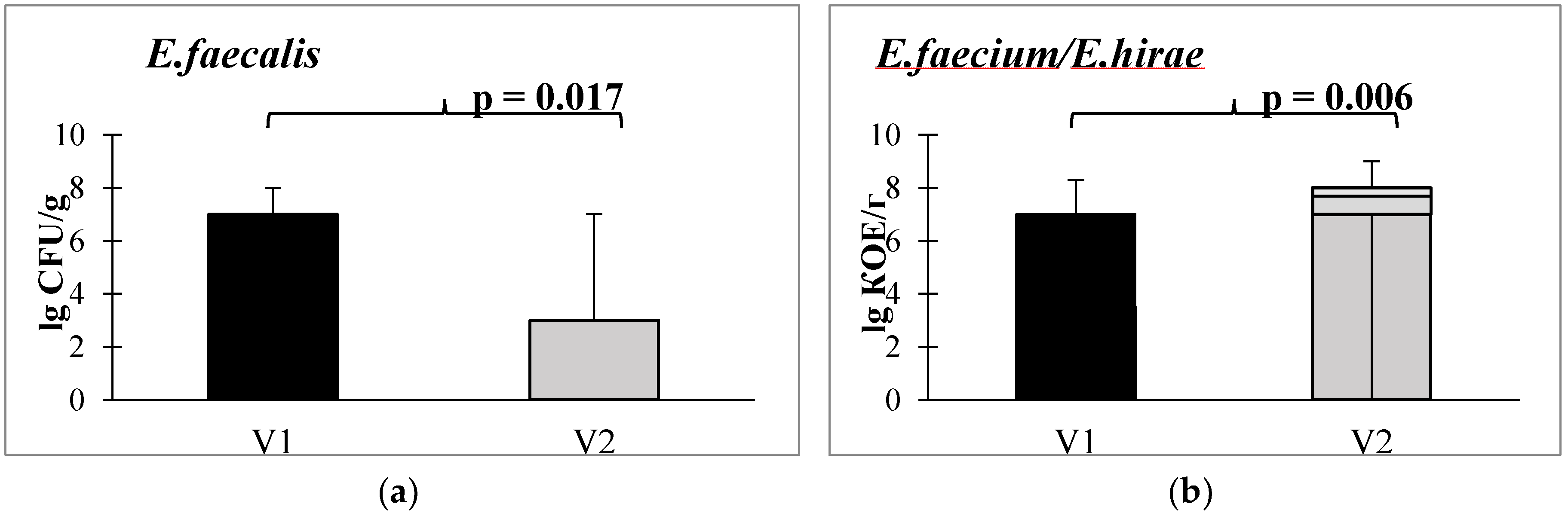

When assessing the content of non-pathogenic Enterococcus spp. in the stool after taking autoprobiotics. Alterations in the abundance of various enterococci species are depicted in

Figure 4: a statistically significant decrease in E. faecalis (

Figure 4A) and an increase in E. faecium or E. hirae was found (

Figure 4B).

A decline in E. faecalis levels and an elevation in the prevalence of generally non-pathogenic enterococci, specifically E. faecium and E. hirae, can be regarded as favorable changes. Primarily, this is attributed to the fact that E. faecalis has the capability to bind and locally activate human fibrinolytic protease plasminogen (PLG). The activation of PLG by E. faecalis induces excessive collagen degradation [

53]. Notably, E. faecalis is the pathogen most frequently identified in postsurgical colonic perforations in humans.

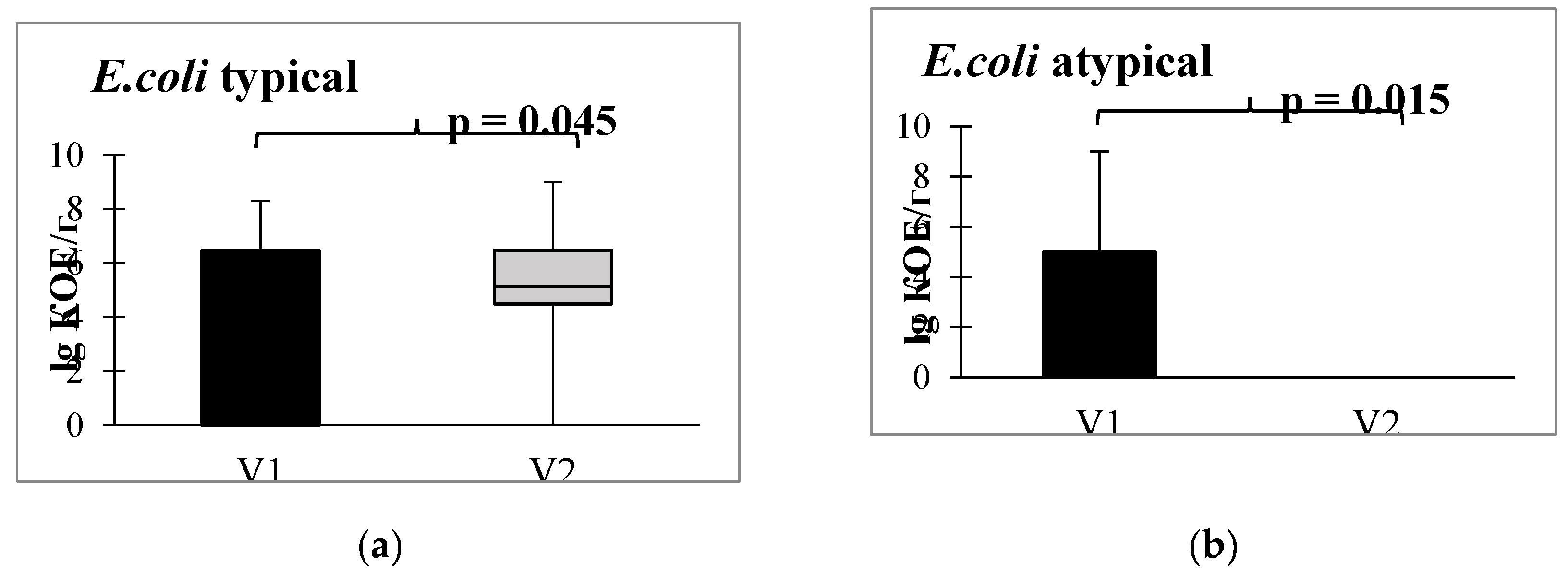

Furthermore, in the bacteriological analysis following the administration of autoprobiotics, a shift in escherichia populations was observed, transitioning from atypical (lactase-negative, hemolytic, sucrose-positive, and displaying low enzymatic activity) to typical forms (

Figure 5).

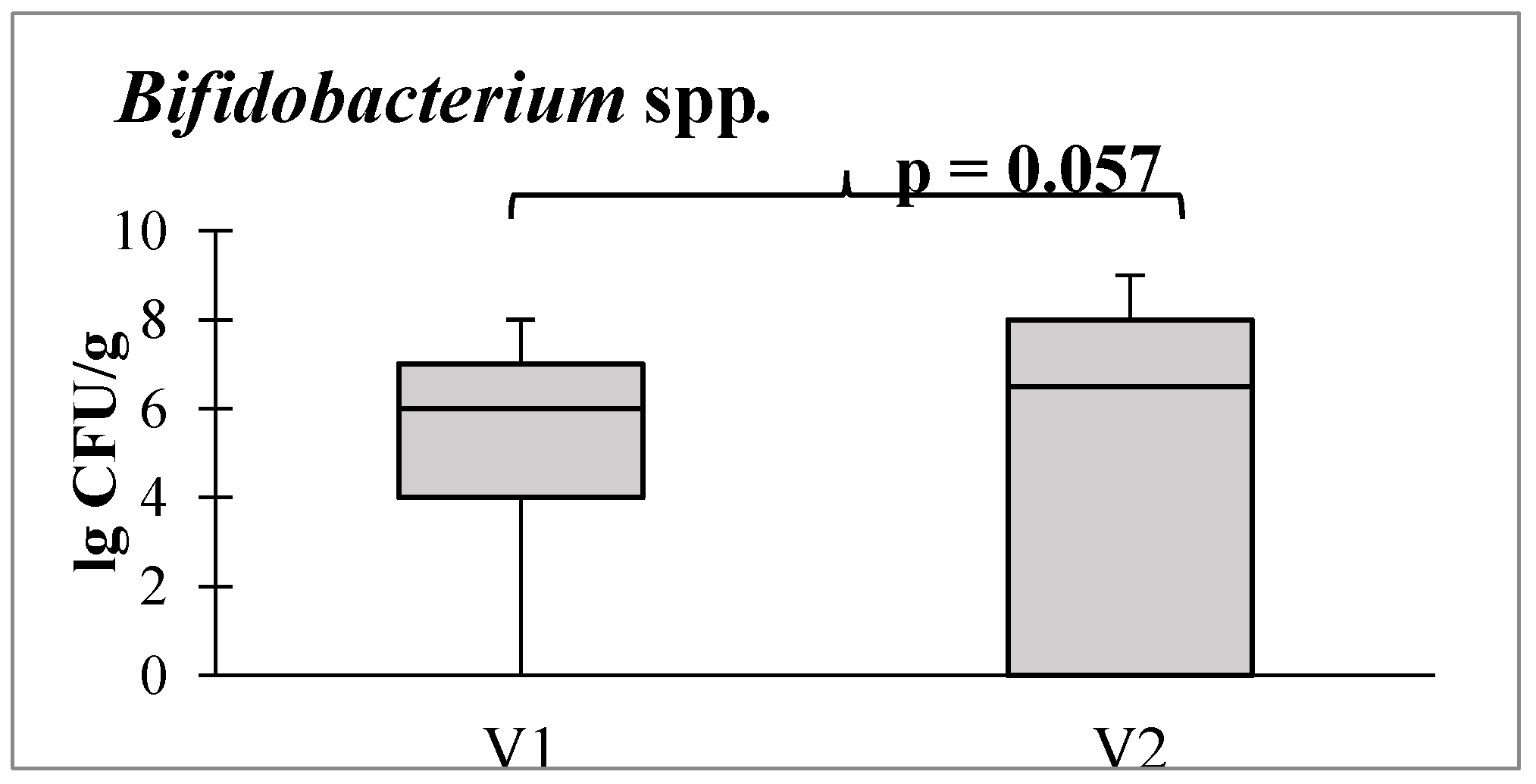

Additionally, there was a tendency toward an increase in the abundance of bifidobacteria, which are obligate beneficial members of the intestinal microbiota (

Figure 6).

3.3.2. qPCR study results

When analyzing the composition of the gut microbiota before and after autoprobiotic usage in early post-surgery period, there were no negative changes in people receiving an autoprobiotic, despite the appearance in the lives of patients of several factors contributing to the deterioration of the gut condition (surgery). After autoprobiotic intake we saw the increase of Lactobacillus spp. and Enterococcus faecium quantity, decrease Akkermantia muciniphyla and Clostridium perfringents populations, disappearance of microbial cancer marker Parvimonas micra and tendency to decrease the content of Enterobacter spp. (

Figure 7).

An important positive change after autoprobiotic therapy is the disappearance of P. micra and Fusobacterium nucleatum. It is well known, that Fusobactetium nucleatum is part of the commensal flora of the intestine and oral cavity, but its presence has been associated with pathological conditions including appendicitis, inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), periodontitis and CRC. Experimental biological models have demonstrated many mechanisms by which F. nucleatum can contribute to the progression of CRC, including E-cadherin-mediated activation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling.15 [

54]. It has also been suggested that F. nucleatum inhibits the antitumor immune response [

55] and decrease effect of chemotherapy [

56].

P. micra, like F. nucleatum, is a commensal of the oral cavity, participates in the pathogenesis of intracranial abscess, pericarditis and necrotizing fasciitis, as well as CRC [

57,

58,

59,

60]. However, the role of P. micra in the progression of CRC is still largely unknown, and the potential of these bacteria as a fecal marker for detecting CRC has not been fully elucidated [

61]. In this study, P. micra was completely eliminated after exposure to an autoprobiotic, which can be considered as one of the positive effects of complex therapy.

An increase in C. perfringens content is a characteristic feature of the microbiota in CRC, and a decrease in their content after therapy with autoprobiotics indicates its success.

According to a meta-analysis, Akkermansia sp. populations tend to increase in CRC, although there are publications indicating the opposite [

6]. In addition, it should be taken into account that mucin degradation caused by A. muciniphila may reduce the thickness of the mucin layer and increase the risk of infectious complications in the digestive tract [

62]. Moreover A. muciniphila protein (named Amuc_1100 protein) interacting with Toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2) , could induce a wide range of immunomodulatory responses, including the production of cytokines IL6, IL8 and IL10 [

63]. Consequently, the decrease in quantitative content akkermansia contributes not only to the stabilization of the intestinal mucosa, but also to a decrease in the level of interleukin, which we reviled during therapy.

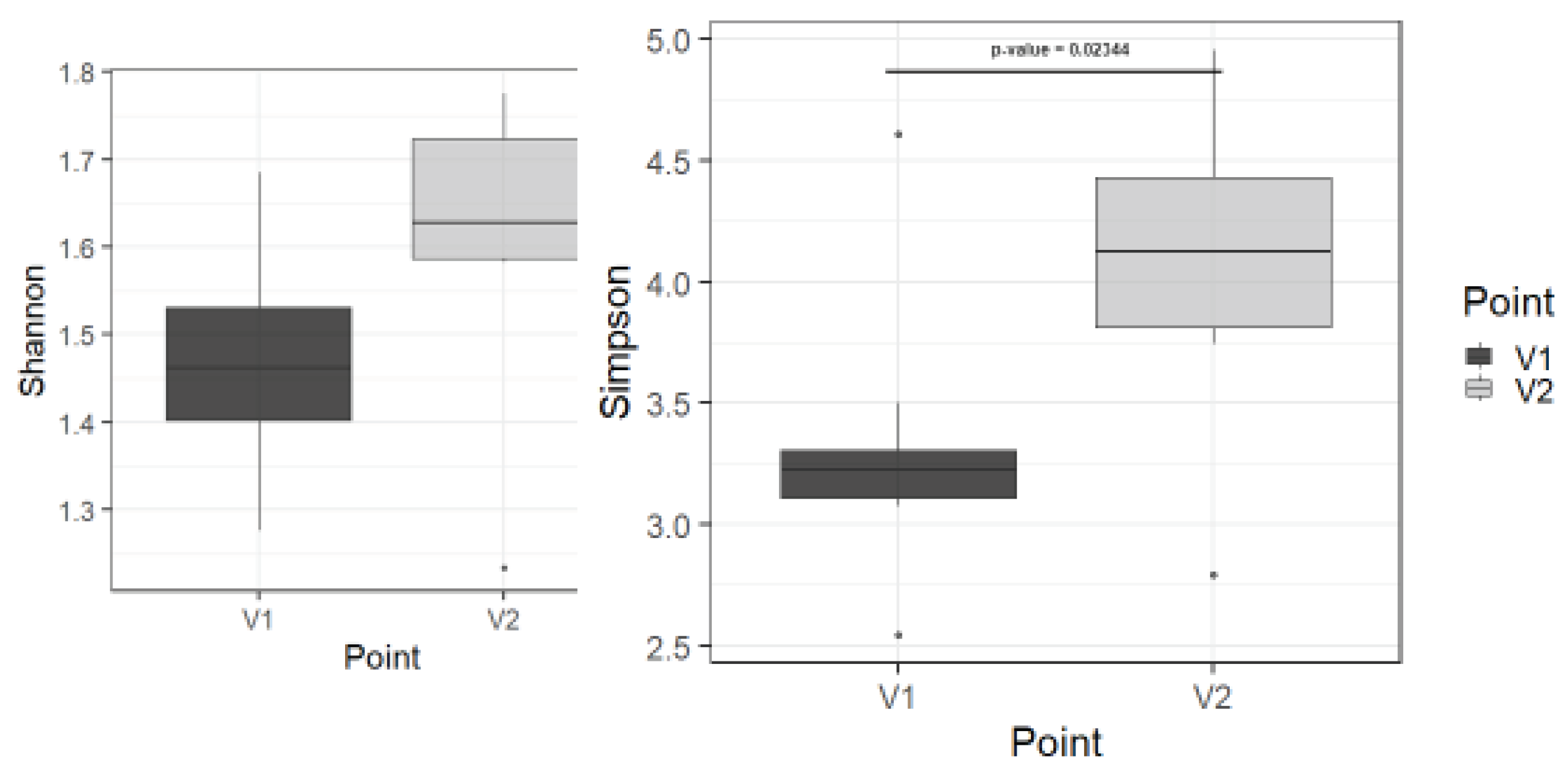

3.3.3. Metagenome analysis study

Using metagenome analysis, statistically significant differences before and after therapy in only in alpha biodiversity in class level (p=0,023) and tendency in other levels (

Figure 8 and

Figure S1). It can be considered as a sign of microbiota recovery.

4. Discussion

Autoprobiotics present a promising avenue for complementary therapy in colorectal cancer. Patients receiving autoprobiotics, compared to the control group, reported fewer postoperative complaints, as validated by GIS for dyspepsia assessment and GSRS for gastroenterological complaints.

The administration of autoprobiotics in the postoperative period is highly effective and safe in the comprehensive treatment of colorectal cancer patients, offering:

A personalized approach to patient care.

Expedited restoration of stool of normal consistency after surgery (type 3-4 on the Bristol scale).

Reduction of abdominal pain, dyspeptic symptoms, and inflammation post-surgery.

Lowering the risk of CRC relapse by diminishing pro-carcinogenic inflammation in the colon associated with gut dysbiosis.

Paper suggests a complex approach in the therapy of CRC the composition of the microbiota in complex therapy of CRC after surgical intervention with autoprobiotic enterococci. Future studies will allow the discovery of additional fine mechanisms of autoprobiotic therapy and its impact on the digestive, immune, endocrine and neural systems.

Early correction of gut microbiota disorders not only aids in reducing inflammation in the colon and swiftly restoring digestive tube motility but also holds promise for improving the prognosis of colorectal cancer. Autoprobiotics are recommended for correcting intestinal dysbiosis in this patient category. The presented studies conducted suggest the safety and high efficacy of autoprobiotic enterococci in colorectal cancer treatment. Postoperative use of autoprobiotics facilitates the postoperative course, enhances the clinical outlook, mitigates inflammation, and supports the restoration of gut microbiocenosis and its functions.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Figure S1. Alpha-biodiversity before and after therapy in the levels of phylum (A), family (B) and genus (C).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N. Baryshnikova and E. Ermolenko; methodology, V. Kashchenko, N. Baryshnikova and E. Ermolenko; software, N. Baryshnikova and E. Ermolenko; validation, N. Baryshnikova and E. Ermolenko; formal analysis, N. Baryshnikova and E. Ermolenko; investigation, A. Ilina, N. Lavrenova, A. Karaseva, N. Gladyshev, A. Morozova, A.Tsapieva, N. Baryshnikova and E. Ermolenko; resources, N. Baryshnikova and E. Ermolenko; data curation, O. Gushchina, T. Ovchinnikov, N. Baryshnikova and E. Ermolenko; writing—original draft preparation, N. Baryshnikova and E. Ermolenko; writing—review and editing, N. Baryshnikova and E. Ermolenko; visualization, N. Baryshnikova and E. Ermolenko; supervision, A. Suvorov and A. Dmitriev and E. Ermolenko; project administration, G. Alekhina, A. Zakharenko, O. Ten, E. Ermolenko. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The work was supported by the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Russian Federation, №075-15-2022-302 (20.04.2022) Federal State Budgetary Scientific Institution “Institute of Experimental Medicine” (FSBSI “IEM”) Scientific and educational center «Molecular bases of interaction of microorganisms and human» of the world-class research center “Center for personalized Medicine” FSBSI “IEM”.

Data Availability Statement

data in free internet access is unavailable due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Institute of Experimental medicine and World-Class re-search center for Personalized medicine for intellectual inspiration.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Baquero F, Nombela C. The microbiome as a human organ. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012, 18 (Suppl 4), 2–4. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hooper LV, Littman DR, Macpherson AJ. Interactions between the microbiota and the immune system. Science. 2012, 336, 1268–73. [CrossRef]

- Alexander KL, Targan SR, Elson CO 3rd. Microbiota activation and regulation of innate and adaptive immunity. Immunol Rev. 2014, 260, 206–20. [CrossRef]

- Zhang M, Sun K, Wu Y, Yang Y, Tso P, Wu Z. Interactions between Intestinal Microbiota and Host Immune Response in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Front Immunol. 2017, 8, 942. [CrossRef]

- Zhao Y, Chen F, Wu W, Sun M, Bilotta AJ, Yao S, Xiao Y, Huang X, Eaves-Pyles TD, Golovko G, Fofanov Y, D'Souza W, Zhao Q, Liu Z, Cong Y. GPR43 mediates microbiota metabolite SCFA regulation of antimicrobial peptide expression in intestinal epithelial cells via activation of mTOR and STAT3. Mucosal Immunol. 2018, 11, 752–762. [CrossRef]

- Tarashi S, Siadat SD, Ahmadi Badi S, Zali M, Biassoni R, Ponzoni M, Moshiri A. Gut Bacteria and their Metabolites: Which One Is the Defendant for Colorectal Cancer? Microorganisms. 2019, 7, 561. [CrossRef]

- Wu N, Yang X, Zhang R, Li J, Xiao X, Hu Y, Chen Y, Yang F, Lu N, Wang Z, Luan C, Liu Y, Wang B, Xiang C, Wang Y, Zhao F, Gao GF, Wang S, Li L, Zhang H, Zhu B. Dysbiosis signature of fecal microbiota in colorectal cancer patients. Microb Ecol. 2013, 66, 462–70. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson CM, Wei C, Ensor JE, Smolenski DJ, Amos CI, Levin B, Berry DA. Meta-analyses of colorectal cancer risk factors. Cancer Causes Control. 2013, 24, 1207–22. [CrossRef]

- Yu J, Feng Q, Wong SH, Zhang D, Liang QY, Qin Y, Tang L, Zhao H, Stenvang J, Li Y, Wang X, Xu X, Chen N, Wu WK, Al-Aama J, Nielsen HJ, Kiilerich P, Jensen BA, Yau TO, Lan Z, Jia H, Li J, Xiao L, Lam TY, Ng SC, Cheng AS, Wong VW, Chan FK, Xu X, Yang H, Madsen L, Datz C, Tilg H, Wang J, Brünner N, Kristiansen K, Arumugam M, Sung JJ, Wang J. Metagenomic analysis of faecal microbiome as a tool towards targeted non-invasive biomarkers for colorectal cancer. Gut. 2017, 66, 70–78. [CrossRef]

- Cougnoux A, Delmas J, Gibold L, Faïs T, Romagnoli C, Robin F, Cuevas-Ramos G, Oswald E, Darfeuille-Michaud A, Prati F, Dalmasso G, Bonnet R. Small-molecule inhibitors prevent the genotoxic and protumoural effects induced by colibactin-producing bacteria. Gut. 2016, 65, 278–85. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-Alcoholado L, Ramos-Molina B, Otero A, Laborda-Illanes A, Ordóñez R, Medina JA, Gómez-Millán J, Queipo-Ortuño MI. The Role of the Gut Microbiome in Colorectal Cancer Development and Therapy Response. Cancers (Basel). 2020, 12, 1406. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karamzin, A.M. , Ropot A.V., Boshian R.E. Relationship of the mucin-degrading bacterium Akkermansia muciniphila with colorectal cancer. Experimental and Clinical Gastroenterology. 2020, 178, 158–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsoi H, Chu ESH, Zhang X, Sheng J, Nakatsu G, Ng SC, Chan AWH, Chan FKL, Sung JJY, Yu J. Peptostreptococcus anaerobius Induces Intracellular Cholesterol Biosynthesis in Colon Cells to Induce Proliferation and Causes Dysplasia in Mice. Gastroenterology. 2017, 152, 1419–1433. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dulal S, Keku TO. Gut microbiome and colorectal adenomas. Cancer J. 2014, 20, 225–31. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dutilh BE, Backus L, van Hijum SA, Tjalsma H. Screening metatranscriptomes for toxin genes as functional drivers of human colorectal cancer. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2013, 27, 85–99. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu X, Wu Y, He L, Wu L, Wang X, Liu Z. Effects of the intestinal microbial metabolite butyrate on the development of colorectal cancer. J Cancer. 2018, 9, 2510–2517. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kochkina, S.O. , Gordeev S.S., Mamedli Z.Z. Role of human microbiota in the development of colorectal cancer. Tazovaya Khirurgiya i Onkologiya = Pelvic Surgery and Oncology 2019, 9, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alasiri, GA. Effect of gut microbiota on colorectal cancer progression and treatment. Saudi Med J. 2022, 43, 1289–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitsillides L, Pellino G, Tekkis P, Kontovounisios C. The Effect of Perioperative Administration of Probiotics on Colorectal Cancer Surgery Outcomes. Nutrients. 2021, 13, 1451. [CrossRef]

- Zakharenko, A.A. , Suvorov A.N., Shlyk I.V., Ten O.A., Dzhamilov S.R., Natkha A.S., Trushin A.A., Belyaev M.A. Disorders of a microbiocenosis of intestines at patients with a colorectal cancer and ways of their correction (review). Coloproctology. 2016, 2, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floch, MH. The Role of Prebiotics and Probiotics in Gastrointestinal Disease. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2018, 47, 179–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaharuddin L, Mokhtar NM, Muhammad Nawawi KN, Raja Ali RA. A randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial of probiotics in post-surgical colorectal cancer. BMC Gastroenterol. 2019, 19, 131. [CrossRef]

- Consoli ML, da Silva RS, Nicoli JR, Bruña-Romero O, da Silva RG, de Vasconcelos Generoso S, Correia MI. Randomized Clinical Trial: Impact of Oral Administration of Saccharomyces boulardii on Gene Expression of Intestinal Cytokines in Patients Undergoing Colon Resection. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2016, 40, 1114–1121. [CrossRef]

- Krebs, B. Prebiotic and Synbiotic Treatment before Colorectal Surgery--Randomised Double Blind Trial. Coll Antropol. 2016, 40, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kim CE, Yoon LS, Michels KB, Tranfield W, Jacobs JP, May FP. The Impact of Prebiotic, Probiotic, and Synbiotic Supplements and Yogurt Consumption on the Risk of Colorectal Neoplasia among Adults: A Systematic Review. Nutrients. 2022, 14, 4937. [CrossRef]

- Khakimova, G.G. , Tryakin A.A., Zabotina T.N., Tsukanov A.S., Aliev V.A., Gutorov S.L. The Role of the Intestinal Microbiome in the Immunotherapy of Colon Cancer. Malignant tumours. 2019, 9, 5–11, (In Russ.). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finlay BB, Goldszmid R, Honda K, Trinchieri G, Wargo J, Zitvogel L. Can we harness the microbiota to enhance the efficacy of cancer immunotherapy? Nat Rev Immunol. 2020, 20, 522–528. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa RL, Moreira J, Lorenzo A, Lamas CC. Infectious complications following probiotic ingestion: a potentially underestimated problem? A systematic review of reports and case series. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2018, 18, 329. [CrossRef]

- Suvorov, A.N., Ermolenko, E.I., Kotyleva, M.P., Tsapieva, A.N.: Method for preparing autoprobiotic based on anaerobic bacteria consortium. Patent for invention 2734896 C2, 10/26/2020. Application No. 2018147697 dated 12/28/2018 [available online]. 10 2020. Available online: https://patents.s3.yandex.net/RU2734896C2_20201026.pdf (accessed on 30 December 2023).

- Shuxrat, T. , Bakievich A.U., Ramizitdinovna A.R., Jo’raevich C.A. Research on the application of protein soya is from local raw materials from Uzbekistan. The American Journal of Agriculture and Biomedical Engineering 2021, 3, 107–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suvorov A.N., Simanenkov V.I., Sundukova Z.R., Ermolenko E.I., Tsapieva A.N., Donets V.N., Solovyova O.I. Method for producing autoprobiotic of enterocuccus faecium being representative of indigenic host intestinal microflora. Patent for invention RU2460778C1, Application RU2010154822/10A dated 12/30/2010 [available online]. 22 Application. Available online: https://patents.google.com/patent/RU2460778C1/en (accessed on 30 December 2023).

- Vershinin AE, Kolodzhieva VV, Ermolenko EI, Grabovskaia KB, Klimovich BV, Suvorov AN, Bondarenko VM. [Genetic identification as method of detection of pathogenic and symbiotic strains of enterococci]. Zh Mikrobiol Epidemiol Immunobiol 2008, (5), 83–87. [PubMed]

- Cheng S, McCleskey FK, Gress MJ, Petroziello JM, Liu R, Namdari H, Beninga K, Salmen A, DelVecchio VG. A PCR assay for identification of Enterococcus faecium. J Clin Microbiol. 1997, 35, 1248–50. [CrossRef]

- Creti R, Imperi M, Bertuccini L, Fabretti F, Orefici G, Di Rosa R, Baldassarri L. Survey for virulence determinants among Enterococcus faecalis isolated from different sources. J Med Microbiol. 2004, 53 Pt 1, 13–20. [CrossRef]

- Dutka-Malen S, Evers S, Courvalin P. Detection of glycopeptide resistance genotypes and identification to the species level of clinically relevant enterococci by PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 1995; 33, 24–7, Erratum in: J Clin Microbiol. 1995, 33, 1434. [CrossRef]

- Eaton TJ, Gasson MJ. Molecular screening of Enterococcus virulence determinants and potential for genetic exchange between food and medical isolates. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2001, 67, 1628–35. [CrossRef]

- Nallapareddy SR, Wenxiang H, Weinstock GM, Murray BE. Molecular characterization of a widespread, pathogenic, and antibiotic resistance-receptive Enterococcus faecalis lineage and dissemination of its putative pathogenicity island. J Bacteriol. 2005, 187, 5709–18. [CrossRef]

- Suvorov A, Karaseva A, Kotyleva M, Kondratenko Y, Lavrenova N, Korobeynikov A, Kozyrev P, Kramskaya T, Leontieva G, Kudryavtsev I, Guo D, Lapidus A, Ermolenko E. Autoprobiotics as an Approach for Restoration of Personalised Microbiota. Front Microbiol. 2018, 9, 1869. [CrossRef]

- Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983, 67, 361–70. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Revicki DA, Wood M, Wiklund I, Crawley J. Reliability and validity of the Gastrointestinal Symptom Rating Scale in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease. Qual Life Res. 1998, 7, 75–83. [CrossRef]

- Adam B, Liebregts T, Saadat-Gilani K, Vinson B, Holtmann G. Validation of the gastrointestinal symptom score for the assessment of symptoms in patients with functional dyspepsia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005, 22, 357–63. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monreal MT, Pereira PC, de Magalhães Lopes CA. Intestinal microbiota of patients with bacterial infection of the respiratory tract treated with amoxicillin. Braz J Infect Dis. 2005, 9, 292–300. [CrossRef]

- Vorob'ev AA, Gershanovich ML, Petrov LN. Predposylki i perspektivy primeneniia probiotikov v kompleksnoĭ terapii onkologicheskikh bol'nykh [Prerequisites and perspectives for use of probiotics in complex therapy of cancer]. Vopr Onkol. 2004, 50, 361–5. [PubMed]

- Bagnenko, S.F. , Zakharenko A.A., Suvorov A.N., Shlyk I.V., Ten O.A., Dzhamilov Sh.R., Belyaev M.A., Trushin A.A., Natkha A.S., Zaitsev D.A., Vovin K.N., Rybal’Chenko V.A. Perioperative changes of colon microbiocenosis in patients with colon cancer. Grekov's Bulletin of Surgery. 2016, 175, 33–37, (In Russ.). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyte, M. Probiotics function mechanistically as delivery vehicles for neuroactive compounds: Microbial endocrinology in the design and use of probiotics. Bioessays. 2011, 33, 574–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desbonnet L, Garrett L, Clarke G, Kiely B, Cryan JF, Dinan TG. Effects of the probiotic Bifidobacterium infantis in the maternal separation model of depression. Neuroscience. 2010, 170, 1179–88. [CrossRef]

- O'Keefe SJ, Ou J, Aufreiter S, O'Connor D, Sharma S, Sepulveda J, Fukuwatari T, Shibata K, Mawhinney T. Products of the colonic microbiota mediate the effects of diet on colon cancer risk. J Nutr. 2009, 139, 2044–8. [CrossRef]

- Wang X, Huycke MM. Colorectal cancer: role of commensal bacteria and bystander effects. Gut Microbes. 2015, 6, 370–6. [CrossRef]

- Zorina, V.N. , Promzeleva N.V., Zorin N.A., Ryabicheva T.G., Zorina R.M. Production of proinflammatory cytokines and alpha-2-macroglobulin by peripheral blood cells in the patients with colorectal cancer. Medical Immunology (Russia). 2016, 18, 483–488, (In Russ.). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim YW, Kim SK, Kim CS, Kim IY, Cho MY, Kim NK. Association of serum and intratumoral cytokine profiles with tumor stage and neutrophil lymphocyte ratio in colorectal cancer. Anticancer Res. 2014, 34, 3481–7. [PubMed]

- Khare P, Bose A, Singh P, Singh S, Javed S, Jain SK, Singh O, Pal R. Gonadotropin and tumorigenesis: Direct and indirect effects on inflammatory and immunosuppressive mediators and invasion. Mol Carcinog. 2017, 56, 359–370. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sparreboom CL, Wu Z, Dereci A, Boersema GS, Menon AG, Ji J, Kleinrensink GJ, Lange JF. Cytokines as Early Markers of Colorectal Anastomotic Leakage: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2016, 2016, 3786418. [CrossRef]

- Jacobson RA, Wienholts K, Williamson AJ, Gaines S, Hyoju S, van Goor H, Zaborin A, Shogan BD, Zaborina O, Alverdy JC. Enterococcus faecalis exploits the human fibrinolytic system to drive excess collagenolysis: implications in gut healing and identification of druggable targets. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2020, 318, G1–G9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zorron Cheng Tao Pu L, Yamamoto K, Honda T, Nakamura M, Yamamura T, Hattori S, Burt AD, Singh R, Hirooka Y, Fujishiro M. Microbiota profile is different for early and invasive colorectal cancer and is consistent throughout the colon. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020, 35, 433–437. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gur C, Ibrahim Y, Isaacson B, Yamin R, Abed J, Gamliel M, Enk J, Bar-On Y, Stanietsky-Kaynan N, Coppenhagen-Glazer S, Shussman N, Almogy G, Cuapio A, Hofer E, Mevorach D, Tabib A, Ortenberg R, Markel G, Miklić K, Jonjic S, Brennan CA, Garrett WS, Bachrach G, Mandelboim O. Binding of the Fap2 protein of Fusobacterium nucleatum to human inhibitory receptor TIGIT protects tumors from immune cell attack. Immunity. 2015, 42, 344–355. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang SS, Xie YL, Xiao XY, Kang ZR, Lin XL, Zhang L, Li CS, Qian Y, Xu PP, Leng XX, Wang LW, Tu SP, Zhong M, Zhao G, Chen JX, Wang Z, Liu Q, Hong J, Chen HY, Chen YX, Fang JY. Fusobacterium nucleatum-derived succinic acid induces tumor resistance to immunotherapy in colorectal cancer. Cell Host Microbe. 2023, 31, 781–797. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drewes JL, White JR, Dejea CM, Fathi P, Iyadorai T, Vadivelu J, Roslani AC, Wick EC, Mongodin EF, Loke MF, Thulasi K, Gan HM, Goh KL, Chong HY, Kumar S, Wanyiri JW, Sears CL. High-resolution bacterial 16S rRNA gene profile meta-analysis and biofilm status reveal common colorectal cancer consortia. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes. 2017; 3, 34Erratum in: NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes. 2019, 5, 2. [CrossRef]

- Purcell RV, Visnovska M, Biggs PJ, Schmeier S, Frizelle FA. Distinct gut microbiome patterns associate with consensus molecular subtypes of colorectal cancer. Sci Rep. 2017, 7, 11590. [CrossRef]

- Shah MS, DeSantis TZ, Weinmaier T, McMurdie PJ, Cope JL, Altrichter A, Yamal JM, Hollister EB. Leveraging sequence-based faecal microbial community survey data to identify a composite biomarker for colorectal cancer. Gut. 2018, 67, 882–891. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu J, Feng Q, Wong SH, Zhang D, Liang QY, Qin Y, Tang L, Zhao H, Stenvang J, Li Y, Wang X, Xu X, Chen N, Wu WK, Al-Aama J, Nielsen HJ, Kiilerich P, Jensen BA, Yau TO, Lan Z, Jia H, Li J, Xiao L, Lam TY, Ng SC, Cheng AS, Wong VW, Chan FK, Xu X, Yang H, Madsen L, Datz C, Tilg H, Wang J, Brünner N, Kristiansen K, Arumugam M, Sung JJ, Wang J. Metagenomic analysis of faecal microbiome as a tool towards targeted non-invasive biomarkers for colorectal cancer. Gut. 2017, 66, 70–78. [CrossRef]

- Löwenmark T, Löfgren-Burström A, Zingmark C, Eklöf V, Dahlberg M, Wai SN, Larsson P, Ljuslinder I, Edin S, Palmqvist R. Parvimonas micra as a putative non-invasive faecal biomarker for colorectal cancer. Sci Rep. 2020, 10, 15250. [CrossRef]

- Hansson, GC. Role of mucus layers in gut infection and inflammation. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2012, 15, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shenderov, B.A. ,Yudin S.M., Zagaynova A.Z., Shevyreva M.P. Akkermansia muciniphila is a new universal probiotic on the basis of live human commensal gut bacteria: the reality or legend? Zh. Mikrobiol. (Moscow) 2019, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).