1. Introduction

Diverticular disease of the colon involves protrusion of the mucosa and submucosa through the muscular tunica into an area of lower resistance of the intestinal wall. The term diverticular disease encompasses several disease entities ranging from diverticulosis to diverticulitis.

Diverticular disease has a worldwide prevalence, but it sees a higher incidence in Western countries with higher rates of industrialization, where it represents the most important disease of the gastrointestinal tract in terms of health and social impact. The formation of acquired diverticular disease correlates with well-defined etiologic factors such as low dietary fiber intake (which leads to a significant increase in endoluminal pressure), age, weakness of the colic wall, alterations in colonic motility, chronic constipation, the presence of other intestinal diseases (such as IBD that can cause cancer or IBS), absence of physical activity, and obesity. [

1,

2,

3,

4]

Although the pathogenesis of the evolution from diverticulosis to diverticulitis (inflammation of the diverticulum) is still uncertain, the role in this process

of alteration of the intestinal microbiota and visceral hypersensitivity is now well established, in addition, of course, to an ever-increasing proportion of

inflammation that is crucial to identify diverticulitis. [

5,

6]

The clinical picture of diverticular disease appears to be heterogeneous as well as divided into stages of increasing intensity. [

7] Asymptomatic diverticulosis is the first stage of diverticular disease; consists of the simple presence of diverticula with absence of symptoms. In these cases, the diverticula do not cause any discomfort, as they are not inflamed. Often at this stage, precisely because of the absence of symptoms, the disease is misdiagnosed or is diagnosed during instrumental examinations performed for other reasons.

The aim of this study is to evaluate how the use of probiotics is useful both for preventive purposes and to avoid the occurrence of pathological pictures affecting the intestinal mucosa, but also how effective their use is in uncomplicated diverticular disease, where the maintenance of eubiosis reduces the risk of diverticulitis.

2. Materials and Methods

The present study is a retrospective analysis of 876 colonoscopies performed by Prof. Giovanni Tomasello from 2019 to 2022, in which were selected 96 patients (48 males and 48 females) with a mean age of 58 (range 34-82 years old). Inclusion criteria were: patients with diverticular disease at low risk of complications (specifically class D.I.C.A. 1 and D.I.C.A. 2) and patients with mild symptomatic diverticular disease. Patients with IBS, IBD, acute and complicated diverticulitis, pre-cancerous lesions (polyps) and neoplastic pathology were excluded from the study.

The selected patients showed the following symptomatology: mild bloating, altered alvus (constipation/diarrhea), mild/moderate pain in the left iliac fossa.

The outpatient clinical case history of digestive endoscopy of Prof. Giovanni Tomasello was evaluated.

Instrumental diagnosis was performed using Olympus 190 Exera 3 HD, high-definition digital system. Endoscopic images obtained during the endoscopic examination were evaluated both in white light and using the virtual chromoendoscopy NBI (Narrow Band Imaging) approach. NBI uses electronic filters inserted into the endoscopic device to decompose the spectrophotometric properties of white light using short-band frequencies.

The NBI allows assessment of the vascular pattern of the mucosa and evaluation of its inflammation degree.

To treat patients was administered in 500 mg tablets a symbiotic composed of probiotics and prebiotics: Lactobacillus plantarum LP115 (400MLD/g), Lactobacillus rhamnosus LR32 (200MLD/g), Bifidobacterium Bifidum SGB02 (10MLD/g), Fructooligosaccharides (FOS), Inulin, Maltodextrin, Lactobacillus Acidophilus LA02 (100MLD/g), Silica Dioxide, Magnesium Stearate. (32)

Patients were divided into two groups according to the D.I.C.A. classification.

Group 1: 60 patients with diverticular disease classified as D.I.C.A. 1

Group 2: 36 patients with diverticular disease classified as D.I.C.A. 2

The patients were in turn divided according to the type of treatment into:

GROUP 1 (D.I.C.A.1):

Group A: probiotic mixture once a day.

Group B: probiotic mixture twice a day.

GROUP 2 (D.I.C.A.2):

Group A: probiotic mixture once a day.

Group B: probiotic mixture twice a day.

Group M: Mesalazine (5-ASA)

Group M+P: Mesalazine (5-ASA) + probiotic mixture once daily.

The clinical picture was evaluated at three different times:

T0: clinical picture before treatment administration.

T1: clinical picture 20 days after treatment administration.

T2: clinical picture 40 days after treatment administration.

3. Results

Patients with diverticular disease D.I.C.A. 1 (Group 1: 60 patients) are included in

Table 1.

Patients presented the following symptoms: stomach bloating, mild pain in the left iliac fossa, and diarrhea/constipation. They were given the probiotic tablets in two forms: single administration (one 500 mg tablet daily) and double administration (two 500 mg tablets daily).

The total duration of treatment is 40 days for both Group A (one tablet per day) and Group B (two tablets a day).

T0 (at the time of diagnosis), T1 (after 20 days of treatment) and T2 (at the end of treatment) are the different types of control. Improvement was visible after 20 days of treatment with the probiotic mixture: in 20 % of patients with diarrhea, 25 % of patients with left iliac abdominal pain, and 28 % of patients with abdominal bloating when treated with one probiotic tablet a day; in contrast, patients treated with two tablets had a higher percentage of remission of symptoms: 40 % for diarrhea, 60 % for abdominal pain, and 34 % for abdominal bloating. The results were even more pronounced after 40 days: in patients treated with one daily administration, 40% remission was noted for diarrhea, 60% for pain and 30% for abdominal bloating. In Group B patients (two tablets daily), efficacy after 40 days was 80% for diarrhea, 85% toward abdominal pain, and 74% for abdominal bloating.

In addition, the patients did not complain in term of complications or side effects that arose as a result of the proposed treatment, and the evolution of the pathology toward diverticulitis was absent in 100% of the cases.

Table 1 shows that treatment leads to improvement in symptoms.

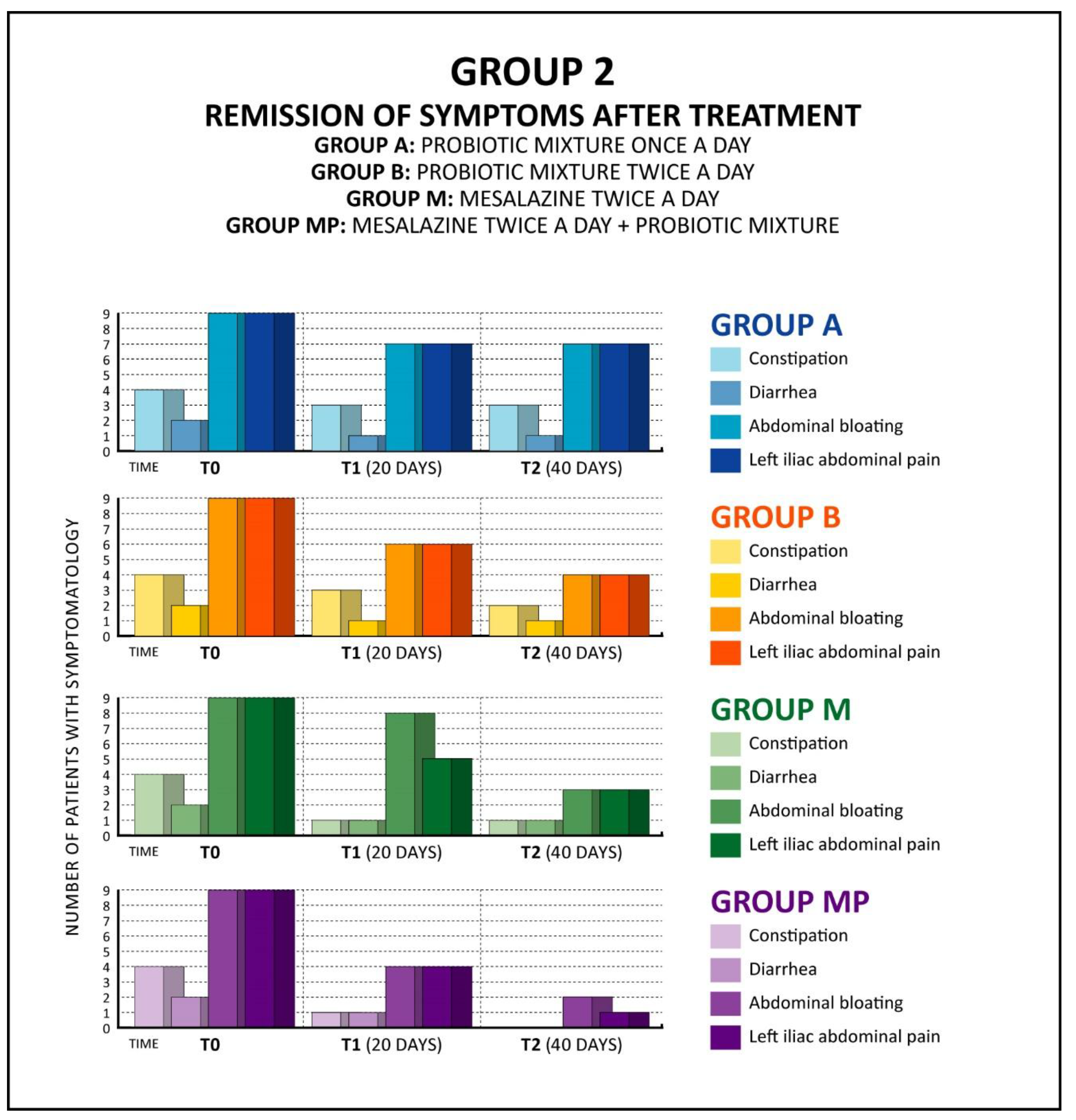

Table 2 shows the data of patients with diverticular disease D.I.C.A. 2 (Group 2: 36 patients).

These patients reported the following symptoms: abdominal bloating, moderate left iliac fossa pain, diarrhea/constipation. Patients were given 4 different treatments: single-dose probiotic mixture (one 500-mg tablet daily), double-dose probiotic mixture (two 500-mg tablets daily), Mesalazine 5-ASA (2 tablets of 1200 mg each), and single-dose probiotic together with Mesalazine 5-ASA (2 tablets of 1200 mg each).

The total duration of treatment is 40 days for the whole group.

A (intake of probiotic mixture once a day).

B (intake of probiotic mixture twice a day).

M (taking Mesalazine twice a day).

MP (taking Mesalazine twice a day and probiotic mixture once a day).

Controls were performed at T0 (at the time of diagnosis), T1 (after 20 days of treatment) and T2 (at the end of 40 days of treatment).

After only 20 days of probiotic mixture therapy, a significant improvement was already noticeable: in patients treated with 2 daily probiotic mixture tablets, an efficacy of 20% for diarrhea, 30% for constipation, 37% for left iliac abdominal pain and 34% for bloating was seen, while in patients treated with probiotic mixture and Mesalazine, a 70% improvement for diarrhea and 50% improvement for constipation, abdominal pain and abdominal bloating was seen. The results were even more evident at the end of 40 days of treatment, especially in the MP group (treatment with Mesalazine and probiotic mixture), with 99% efficacy toward constipation and diarrhea, 80% for abdominal pain and 90% toward abdominal bloating.

Combined administration of Mesalazine and probiotic mixture demonstrated greater efficacy in terms of clinical response compared to the treatment with only Mesalazine.

In addition, the patients did not complain of complications or side effects that arose as a result of the proposed treatment, and the evolution of the pathology toward diverticulitis was absent in 100% of the cases.

Table 2 shows significant improvement in symptoms following treatment.

Figure 1.

Trend of symptomatology at T0, T1 and T2, after the different types of treatment.

Figure 1.

Trend of symptomatology at T0, T1 and T2, after the different types of treatment.

Figure 2.

Trend of symptomatology at T0, T1 and T2, following the different types of treatments.

Figure 2.

Trend of symptomatology at T0, T1 and T2, following the different types of treatments.

4. Discussion

In symptomatic uncomplicated diverticular disease (SUDD) the symptoms appears to be correlated with minimal inflammatory changes in the diverticular mucosa and the action of toxic pro-inflammatory metabolites, produced by the dysbiotic microbial flora. [

8,

9] The clinical picture is characterized by abdominal pain, abdominal distension, stool emission with mucus, and alterations in alvus (diarrhea/constipation) [

10].

Acute diverticulitis, the macroscopic inflammation of one or more diverticula, occurs in 10-25% of patients with diverticula. The inflammatory picture arises from the diverticular mucosa and may extend to the entire diverticulum but also into the peri-diverticular tissue or into the peri-colic adipose tissue.

Diverticulitis is distinguished into uncomplicated diverticulitis and complicated diverticulitis.

In uncomplicated diverticulitis the predominant symptom is pain localized in the hypochondrium/left iliac fossa, which may be associated with other indices of inflammation of the intestinal wall, such as fever, leukocytosis, and increased CRP. The intensity of the pain and the extent of the overall clinical picture depend on the progression of the inflammatory process, which may be localized or diffuse.

The aggravation of the clinical picture (a condition that occurs in about 12% of patients) leads to complicated diverticulitis characterized by the same symptomatic parade, which may be associated with one or more complications: diverticular perforation, diverticular hemorrhage, intestinal perforation, diverticular and peri-diverticular abscesses, peritonitis, fistulas, scar fibrosis, and intestinal occlusion.

In addition to the clinical picture, the diagnosis of a patient who presents symptoms compatible with acute diverticulitis includes, among the early diagnostic investigations, physical examination, biohumoral findings and imaging techniques (such as ultrasonography and CT scan of the abdomen with contrast media). In particular, CT scan of the abdomen currently represents the diagnostic gold standard: it can diagnose both the presence of diverticula and any complications, with a sensitivity and specificity exceeding 90%. [

11]

Endoscopic diagnostic techniques (colonoscopy) also play an important role in the diagnosis of diverticular disease, particularly in diverticulosis (often diagnosed incidentally during the search for other diseases). In fact, it is believed that performing colonoscopy in a patient with a picture of acute diverticulitis is not recommended because of the risk of perforation related to insufflation and instrument manipulation maneuvers, with technical difficulties related to colonic spasms, narrowing of the lumen, and fixity of the viscera resulting from previous peri-colic inflammation and fibrosis [

12,

13]. Of paramount importance for diverticular evaluation at colonoscopy is the D.I.C.A. classification, which allows us to stadiate diverticular disease based on its extent, the number of diverticula, the presence of mucosal inflammation, the presence of reduced visceral distensibility and the degree of stenosis. The D.I.C.A. classification is critical as it allows us to understand the likelihood that patient has of developing complications. Colonoscopy can also be useful as a conservative treatment of diverticular bleeding. Other more innovative diagnostic techniques are virtual colonoscopy and colon-RMN.

According to the most up-to-date indications reported in the literature, the therapeutic management of diverticular disease is changeable in relevance to the clinical signs and symptoms presented by the patient. Therefore, the non-unique and varied symptomatology found in diverticular disease necessarily leads to a variability of therapeutic aids used. [

14]

Fundamental are indications to avoid the evolution of diverticular disease into diverticulitis, such as proper fiber intake (especially methylcellulose), adequate physical activity and avoidance of irritants such as cigarette smoke or foods containing proinflammatory substances.

The treatment of intestinal dysbiosis by probiotic implementation seems to have an important function in the improvement of diverticulum-related symptoms and contributes to stop the possible evolution from diverticulosis to diverticulitis. Moreover, being a low-cost and noninvasive treatment in recent years there are a growing number of studies aimed at evaluating its efficacy in single administration or in combination with the other therapeutic aids, to use probiotics in a more routinely way. [

15,

16,

17,

18]

Rifaximin, a topical antibiotic, is an effective treatment in SUDD because of its characteristics as a broad-spectrum antibiotic and excellent bioavailability in the gastrointestinal tract, given its non-systemic action. Assuming the role of low-grade inflammation in diverticular disease, an anti-inflammatory such as Mesalazine may be an interesting therapeutic option. There is evidence to show that its use improves symptoms and may even prevent diverticulitis. [

19]

Of fundamental importance in approaching acute diverticulitis is the assessment of the severity of the picture and its complexity, with particular attention to the possible presence of complications.

In acute, severe and complicated forms of diverticulitis, hospitalization, fasting, rehydration with parenteral fluids and systemic antibiotic therapy, as well as targeted treatment according to the complications that have arisen, is recommended by all European and American guidelines [

20,

21,

22,

23].

The first line in intravenous antibiotic therapy is the second-generation cephalosporins (Cefmetazole, Cefaclor, Cefamandolo, Cefonicid, Cefotetan, ect.) followed then by Metronidazole and Ciprofloxacin.

Due to the good response to medical therapy, the low risk of flare-ups, and the reduced risks of long-term consequences of emergency surgery (3-7%), there is no indication for prophylactic surgery in election after one or more episodes of acute diverticulitis, but it must be evaluated on a case-by-case basis. Despite this evidence, it has been seen that the highest risk of severe complications (perforation primarily) occurs during the first episode of acute diverticulitis and that surgery does not completely protect, especially in patients < 40 years old, from disease recurrence.

Surgical treatment of diverticular disease can be performed on an elective or emergency basis. It is to be considered the last therapeutic approach according to the latest guidelines; in fact, it is usually reserved for those cases that are non-responders to medical therapy or in cases of complications that have arisen. [

24]

Elective surgery tends to be adopted in those patients with diverticular pathology complicated by stenosis or fistulas, while emergency surgery is adopted in those cases of perforations with peritonitis. [

25]

In acute, complicated diverticulitis, the most commonly used surgical technique is the two-stage Hartmann surgery: it involves surgical induction of diversion colitis in the intestinal segment excluded from fecal transit. It involves surgical resection of the sigma and the proximal portion of the rectum. [

26]

The descending colon is abutted, temporarily, to the left anterior abdominal wall by packing a colostomy, and the sigmoid-rectal stump is sutured and left in place intraperitoneally. Subsequently, after a few months, intestinal continuity is reestablished. [

27]

The data for patients with D.I.C.A.1 diverticular disease shown in

Table 1 allow us to assess that improvement was visible as early as 20 days of probiotic mixture therapy (T1) and even more after 40 days of treatment (T2).

Table 1 shows, in fact, that there is an improvement in the clinical picture in 40-60 % of cases treated with one daily probiotic administration, and 75-85 % with two administrations instead, thus also emphasizing the greater effectiveness of the treatment when administered twice a day instead of once.

The efficacy of probiotics can also be valuated in cases of diverticular disease classified as D.I.C.A.2: symptomatic patients responded in terms of clinical improvement already after the first week of treatment (both single and double dose).

In all cases, the probiotic proved effective as a stand-alone treatment and even more in combination with Mesalazine.

The treatment gave better results at higher dosages of probiotic mixture, and the improvement was greater after 40 days of treatment. These results were in accordance to those found in literature. [

28,

29,

30,

31]

In addition, the use of probiotic mixture as monotherapy enabled the maintenance of well-being status throughout the observation period in patients in remission; patients treated exclusively and cyclically in preventive therapy with probiotic mixture once daily showed no occurrence of complications during the observation period. [

32]

The administration of Mesalazine and probiotic mixture gave an improvement in the clinical picture in 90% of cases, while treatment with Mesalazine alone was effective in 74% of cases. This finding suggests how the inclusion of probiotic as a treatment co-administered with Mesalazine could be a good therapeutic alternative in all of those clinical pictures of diverticular disease with mild/moderate symptoms.

The use of symbiotic products containing probiotic and prebiotic species has been proposed as a preventive and therapeutic measure to restore the healthy composition and function of the intestinal microbiota[

33,

34,

35,

36] . From the observation and analysis of the clinical data collected, it can be observed that the exclusive therapy, or even more in co-sommininstration with Mesalazine is a valuable support in significantly improving the clinical symptoms of patients with D.I.C.A. 1 and D.I.C.A.2 diverticular disease as early as after the first 20 days of treatment with a trend of improvement after 40 days.

The probiotic mixture has also been shown to be effective in maintaining the clinical remission state and reducing the risk of complications.

In addition, no patient undergoing the above treatments developed diverticular inflammation with evolution into diverticulitis, suggesting how the probiotic mixture use is also useful in maintaining the remission state of the condition and preventing its evolution. [

37,

38,

39]

The results observed in this analysis are in line with the international scientific literature, which increasingly predicts clinical trials based on the therapeutic use of pre-probiotic strains in the treatment of alimentary canal disorders. [

40,

41,

42]

Further studies are also desirable in order to have more clinical data that will allow us to better understand how to include probiotic implementation as a complementary therapy for diverticular disease.

5. Conclusions

96 patients with diverticular disease at low risk of complications ( D.I.C.A. 1 and D.I.C.A 2) were divided in two groups, group 1 treated by probiotic mixtre, group 2 treated by probiotic mixture, mesalazine alone, mesalazine + probiotic mixture.

Patients treated with probiotic mixture showed no occurrence of complications during the observation period.

The administration of mesalazine and probiotic mixture gave an improvement in the clinical picture in 90% of cases, while treatment with mesalazine alone was effective in 74% of cases.

The probiotic mixture has also shown to be effective in maintaining the clinical remission state and reducing the risk of complications.

References

- Tomasello, G.; et al. The fingerprint of the human gastrointestinal tract microbiota: a hypothesis of molecular mapping. Journal of Biol Regul & Homeost Agents 2017, 31, 245–249. [Google Scholar]

- Cappello, F.; Mazzola, M.; Jurjus, A.; Zeeny, M.N.; Jurjus, R.; carini, F.; Leone a Bonaventura, G.; Tomasello, G.; Bucchiari, F.; Conway de Macario, C.; Macario, A.J.L. Hsp 60 as a new target in the management of ibd: A perspective. Frontiers in Pharmacology 2019, 10, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jurjus, A.; Eid, A.; Al Kattar, S.; Zeeny Mn Gerges-Geagea, A.; Haydar, H.; Hilal, A.; Ouiedat, D.; Matar, M.; Tawilah, J.; Hussein Hajj, I.; Schembri-Wismayer Cappello, F.; Tomasello, G.; Leone, A.; Jurjus, R. Inflammatory bowel disease, colorectal cancer and type 2 diabetes mellitus: The links. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta-Clinical. 2016, 5, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SFukudo Pathogenesis of irritable bowel syndrome, J. Japanese Soc. Gastroenterol. 2014, 111, 1323–1333. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, J.; Li, R.; Raes, J.; Arumugam, M.; et al. A catalog of human intestinal microbiome genes established by metagenomic sequencing. Nature 2010, 4, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messina, M.; Mazzola, M.; Carini, F.; Scardina, A.S.; Tulone, L.; Milazzo, V.; Crapanzano, F.; Gagliardo, C.; Damiani, P.; Tomasello, G. Oral microbiota: Characteristics, related pathologies and future perspectives. International Journal of Clinical Dentistry. 2020, 13, 173–179. [Google Scholar]

- Tomasello, G.; Mazzola, M.; Jurjus, A.; Cappello, F.; Carini, F.; Damiani, P.; Gerges geagea, A.; Zeeny, M.N.; Leone, A. Fingerprinting the microbiota of the human gastrointestinal tract: A molecular mapping hypothesis. Journal of Biol Regul & Homeost Agents. 2017, 31, 245–249. [Google Scholar]

- Tomasello, G.; Tralongo, P.; Damiani, P.; Sinagra, E.; Di Trapani, B.; Zeenny, M.N.; Hussein, I.H.; Jurjus, A.; Leone, A. Dismicrobialism in inflammatory bowel disease and colorectal cancer: Changes in colocyte response. World J Gastroenterol. 2014, 20, 18121–18130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traina, G.; Casagrande Proletti, P.; Menchetti, L.; Leonardi, L.; Tomasello, G.; Barbato, O.; Piro, F.; Brecchia, G. Colonic microbial composition correlates with the severity of 2,4,6-trinitrobenzenesulfonic acid-induced colitis in mice. Euro Mediterranean Biomedical Journal 2016, 11, 165–175. [Google Scholar]

- Petruzziello, L.; Iacopini, F.; Bulajic, M.; Shah, S.; Costamagna, G. Review article: Uncomplicated diverticular disease of the colon. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2006, 23, 1379–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinagra, E.; Tomasello, G.; Raimondo, D.; Sturm, A.; Giunta, M.; Messina, M.; Damiano, G.; Palumbo, V.D.; Spinelli, G.; Rossi, F.; Facella, T.; Marasà, S.; Cottone, M.; Lo Monte, A.I. Advanced endoscopic imaging for surveillance of dysplasia and colorectal cancer in inflammatory bowel disease: Can the pathologist be further aided? Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2014, 20, 26–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinagra, E.; Raimondo, D.; Pompei, G.; Fusco, G.; Rossi, F.; Tomasello, G.; Leone, A.; Cappello, F.; Morreale, G.C.; Midiri, F.; Midiri, M.; Rizzo, A.G. Focal active colitis as a predictor of inflammatory bowel disease: Results from a single-center trial. Journal Biol regul Homeost Agents 2017, 31, 1119–1125. [Google Scholar]

- Tomasello, G.; Damiani, P. Dysbiosis, inflammatory bowel disease, and colon cancer: A correlation exists. Book chapter: Morphology and Clinical. Studies in honor of Prof. A. Jurjus. pp: 107-110. Plumelia Editor, 2017.

- Carini, F.; Mazzola, M.; Gagliardo, C.; Scaglione, M.; Giammanco, M.; Tomasello, G. Inflammatory bowel disease and infertility: Review of the literature and future perspectives. Acta Biomed 2021, 92, e2021264. [Google Scholar]

- Tomasello, G.; Mazzola, M.; Leone, A.; Sinagra, E.; Zummo, G.; Farina, F.; Damiani, P.; Cappello, F.; Gerges Geagea, A.; Jurjus, A.; Bou Assi, T.; Messina, M.; Carini, F. Nutrition, oxidative stress and intestinal dysbiosis: Influence of diet on the intestinal microbiota in inflammatory bowel disease. Biomed Pap Med Fac Univacky Olomouc Czech Repub. 2016, 160, 461–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzola, M.; Carini, F.; Leone, A.; Damiani, P.; Messina, M.; Jurjus, A.; Geagea Gerges, A.; Jurjus Rosalyn Tomasello, G. Ibd, malignancy, and the oral microbiota: Review of the literature. Intern Journ of Clinic Dentistry 2016, 9, 273–278. [Google Scholar]

- RTojo, A. Suárez, M.G. Clemente, C.G. De Los Reyes-Gavilán, A. Margolles, M. Gueimonde, P. Ruas-Madiedo, Intestinal microbiota in health and disease: Role of bifidobacteria in gut homeostasis. World J. Gastroenterol. 2014, 20, 15163–15176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palumbo, V.D.; Romeo, M.; Marino Gammazza, A.; Carini, F.; Damiani, P.; Damiano, G.; Buscemi, S.; Lo Monte, A.I.; Gerges-Geagea, A.; Jurjus, A.; Tomasello, G. The long-term effects of probiotics in the therapy of ulcerative colitis: A clinical study. Biomed Pap Med Fac Univ Palacky Olomouc Czech Repub. 2016, 160, 372–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerges Geagea, A.; Rizzo, M.; Jurjus, A.; Cappello, F.; Leone, A.; Tomasello, G.; Gracia, C.; Al Kattar, S.; Massaad-Massade, L.; Eid, A. A new therapeutic approach to colorectal cancer in diabetes: Role of metformin and rapamycin. Oncotarget. 2019, 10, 1284–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carini, F.; Mazzola, M.; Rappa, F.; Jurjus, A.; Gerges Geagea, A.; Al Kattar, S.; Bou-Assi Tarek Jurjus, R.; Damiani, P.; Leone, A.; Tomasello, G. Colorectal carcinogenesis: Role of oxidative stress and antioxidants. Anticancer Reasearch 2017, 37, 4759–4766. [Google Scholar]

- Mazzola, M.; Carini, F.; Leone, A.; Damiani, P.; Jurjus, A.; Geagen Gerges, A.; Jurjus, R.; Assi Bou, T.; Trovato, E.; Rappa, F.; Tomasello, G. Inflammatory bowel disease and colorectal cancer, nutraceutical aspects. Euro Mediterranean Biomedical Journal 2016, 11, 123–129. [Google Scholar]

- Altomare, R.; Damiano, G.; Abruzzo, A.; Palumbo Vd Tomasello, G.; Buscemi, S.; Lo Monte, A.I. Enteral nutrition support for the treatment of malnutrition in inflammatory bowel disease. Nutrients 2015, 7, 2125–2133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbruzzo, A.; Tomasello, G.; Sinagra, E.; Cappello, F.; Damiani, P.; Damiani, F.; Bellavia, M.; Campanella, C.; Rappa, F.; Marino Gammazza, A.; Cicero, L.; Lo Monte, A.I. Nutrition in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Journal of Biological Research 2015, 88, 16. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammed Vashist, N.; Samaan, M.; Mosli, M.H.; Parker, C.E.; MacDonald, J.K.; Nelson, S.A.; Zou, G.Y.; Feagan, B.G.; Khanna, R.; Jairath, V. Endoscopic scoring indices for evaluation of disease activity in ulcerative colitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018, 1, CD011450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simren, M.; Palsson, O.S.; Whitehead, W.E. Update on Rome IV criteria for colorectal disorders: Implications for clinical practice. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2017, 19, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Emara, M.H.; Salama, R.I.; Hamed, E.F.; Shoriet, H.N.; Abdel-Aziz, H.R. Nonspecific colitis among patients with colitis: Frequency relationship to inflammatory bowel disease a prospective study. J. Coloproctology. 2019, 3, 9319–9325. [Google Scholar]

- Sinagra E, Orlando A, Scalisi A, Mocciaro F, Criscuoli, V; Oliva L, Maisano S, Giunta M, La Seta F, Solina G, Rizzo AG, Leone A, Tomasello G, Cappello F, Cottone, M. Clinical course of severe colitis: A comparison between crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis. Journal of Biol. Regul. And Homeost. Agents. 2018, 32, 415–423.

- Palumbo, V.D.; Romeo, M.; Marino Gammazza, A.; Carini, F.; Damiani, P.; Damiano, G.; Buscemi, S.; Lo Monte, A.I.; Gerges-Geagea, A.; Jurjus, A.; Tomasello, G. The long-term effects of probiotics in the therapy of ulcerative colitis: A clinical study. Biomed Pap Med Fac Univ Palacky Olomouc Czech Repub. 2016, 160, 372–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altomare, R.; Damiano, G.; Gioviale, M.C.; Palumbo, V.D.; Maione, C.; Spinelli, G.; Sinagra, E.; Abruzzo, A.; Lo Monte, G.; Tomasello, G.; Lo Monte, A.I. The intestinal ecosystem and probiotics. Progress in Nutrition 2016, 18, 8–15. [Google Scholar]

- Abruzzo, A.; Damiano, G.; Altomare, R.; Palumbo, V.D.; Tomasello, G.; Buscemi, S.; Lo Monte, G.; Maione, C.; Buscemi, G.; Lo Monte, A.I. The influence of some dietary components on the gut microbiota Progress in Nutrition 2016, 18, 205-212.

- ME Sanders, D.J. Merenstein, G. Reid, G.R. Gibson, R.A. Rastall, Probiotics and prebiotics in intestinal health and disease: From biology to the clinic. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 16, 605–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tursi, A.; Brandimarte, G.; Elisei, W.; et al. Randomized clinical trial: Mesalazine and/or probiotics in maintaining remission of symptomatic uncomplicated diverticular disease - double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2013, 38, 741–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberti G, Mazzola, M; Gagliardo C, Pitruzzella A, Fucarini A, Giammanco M, Tomasello G, Carini, F. Extracellular vesicles derived from the intestinal microbiota in inflammatory bowel disease and colorectal cancer. Biomed Pap Med. 2021, 165, 233–240. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinagra E, Morreale GC, Mohammadian G, Fusco G, Guarnotta, V; Tomasello G, Cappello F, Rossi F, Amvrosiadis G, Raimondo, D. New therapeutic perspectives in irritable bowel syndrome: Targeting low-grade inflammation, immune-endocrine axis, motility, secretion and beyond. World Journal of Gastroenterology 2017, 23, 6593–6627. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giammanco, M.; Mazzola, M.; Giammanco, M.M.; Tomasello, G.; Carini, F. Omega-3 pufas and intestinal mycribiota: A preventive approach for colorectal cancer. Journal of Biological Research. 2021, 94, 9954. [Google Scholar]

- Carini F, David S, Tomasello G, Mazzola M, Damiani P, Rappa, F; Battaglia L, Cappello F, Jurjus A, Gerges Geagea A, Jurjus A, Leone, A. Colorectal cancer: An update on the effects of lycopene on tumor progression and cell proliferation. Journal of Biological regulators & Homeostatic Agents. 2017, 31, 769–774.

- Sinagra, E.; Pompei, G.; Tomasello, G.; Cappello, F.; Morreale, G.C.; Amvrosiadis, G.; Rossi, F.; Lo Monte, A.I.; Rizzo, A.G.; Raimondo, D. Inflammation in Irritable Bowel Syndrome: Myth or new therapeutic target. World J Gastroenterol. 2016, 22, 2242–2255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomasello, G.; Giammanco, M.; Mazzola, M.; Damiani, P.; Rà, W.; Giammanco, P.; Rappa, F.; Pitruzzella, A.; Saguto, D.; Di Trapani, B.; Taverna, G.; Carini, M.; Ciulla, A.; Carini, F. Antitumor activity of curcumin: An adjuvant therapeutic strategy. Journal of Biological Research 2020, 93, 8252. [Google Scholar]

- Cappello, F.; Rappa, F.; Carini, F.; Mazzola, M.; Tomasello, G.; Bonaventura, G.; Giuliana, G.; Leone, A.; Saguto, D.; Scalia, F.; Bucchieri, F.; Fucarino, A.; Campisi, G. Probiotics can cure oral aphthous-like ulcers in inflammatory bowel disease patients: A review of the literature and a working hypothesis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2019, 20, 5026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomasello, G.; Pirrotta, P. Probiotics in the complementary treatment of diseases of the large intestine". Ch. 9 (p. 159-169) of the text the Probiotics Edited by Luciano Lozio. Giampiero Casagrande Publisher, 2017.

- Barone, R.; Rappa, F.; Macaluso, F.; Caruso Bavisotto, C.; Sangiorgi, C.; Di Paola, G.; Tomasello, G.; Di Felice, V.; Marcianò, V.; Farina, F.; Zummo, G.; Conway de Macario, E.; Macario, A.J.; Cocchi, M.; Cappello, F.; Gammazza, M. Alcoholic liver disease: A mouse model reveals protection by Lactobacillus fermentum. A. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2016, 7, e138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EMM Quigley. Prebiotics and probiotics in digestive health. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 17, 333–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Table 1.

Endoscopic and clinical evaluation of patients was included in Group 1 according to the criteria of the D.I.C.A. classification.

Table 1.

Endoscopic and clinical evaluation of patients was included in Group 1 according to the criteria of the D.I.C.A. classification.

Symptoms

D.I.C.A 1 [60 Patients] |

T0 Diagnosis

Patient Group

A + B |

T1A Clinical improvement after 20 days of therapy

1 tablet after breakfast |

T1B Clinical improvement after 20 days of therapy

2 tablet after breakfast/dinner |

T2A Clinical improvement after 40 days of therapy

1 tablet after breakfast |

T2B Clinical improvement after 40 days of therapy

2 tablet after breakfast/dinner |

| Diarrhea |

5A + 5B

Total patients= 10

|

Improvement in 20% of clinical cases treated

(1 Patients) |

Improvement in 40% of clinical cases treated

(2 Patients)

|

Improvement in 40% of clinical cases treated

(2 Patients)

|

Improvement in 80% of clinical cases treated

(4 Patients)

|

| Left iliac abdominal pain |

20A + 20B

Total patients= 40

|

Improvement in 25% of clinical cases treated

(5 Patients)

|

Improvement in 60% of clinical cases treated

(12 Patients)

|

Improvement in 60% of clinical cases treated

(12 Patients)

|

Improvement in 85% of clinical cases treated

(17 Patients)

|

| Abdominal bloating |

30A + 30B

Total patients= 60

|

Improvement in 28% of clinical cases treated

(8 Patients)

|

Improvement in 34% of clinical cases treated

(10 Patients)

|

Improvement in 30% of clinical cases treated

(9 Patients)

|

Improvement in 74% of clinical cases treated

(22 Patients)

|

Table 2.

Endoscopic and clinical evaluation of patients included in Group 2.

Table 2.

Endoscopic and clinical evaluation of patients included in Group 2.

Symptoms

D.I.C.A 2 [36 Patients] |

Constipation |

Diarrhea |

Left iliac abdominal pain |

Abdominal bloating |

T0 Diagnosis

Patient Group

A + B + M + MP

|

4A + 4B + 4M + 4MP

Total patients= 16

|

2A + 2B + 2M + 2MP

Total patients= 8

|

9A + 9B + 9M + 9MP

Total patients= 36

|

9A + 9B + 9M + 9MP

Total patients= 36

|

| T1A Clinical improvement after 20 days of therapy: probiotic mixture 1 tablet after breakfast |

Improvement in 20% of clinical cases treated

(1 Patient) |

Improvement in 50% of clinical cases treated

(1 Patients) |

Improvement in 25% of clinical cases treated

(2 Patients)

|

Improvement in 20% of clinical cases treated

(2 Patients)

|

| T1B Clinical improvement after 20 days of therapy: probiotic mixture 2 tablet after breakfast/dinner |

Improvement in 20% of clinical cases treated

(1 Patient) |

Improvement in 50% of clinical cases treated

(1 Patient) |

Improvement in 37% of clinical cases treated

(3 Patients)

|

Improvement in 34% of clinical cases treated

(3 Patients)

|

| T1M Clinical improvement after 20 days of therapy: Mesalazine 2 tablet |

Improvement in 34% of clinical cases treated

(3 Patients)

|

Improvement in 50% of clinical cases treated

(1 Patient) |

Improvement in 50% of clinical cases treated

(1 Patient) |

Improvement in 45% of clinical cases treated

(4 Patients)

|

| T1M+P Clinical improvement After 20 days of therapy: Probiotic mixture 1 tablet + Mesalazine 2 tablet |

Improvement in 70% of clinical cases treated

(3 Patients) |

Improvement in 50% of clinical cases treated

(1 Patient) |

Improvement in 50% of clinical cases treated

(5 Patients)

|

Improvement in 51% of clinical cases treated

(5 Patients)

|

| T2A Clinical improvement after 40 days of therapy: probiotic mixture 1 tablet after breakfast |

Improvement in 20% of clinical cases treated

(1 Patient) |

Improvement in 50% of clinical cases treated

(1 Patient) |

Improvement in 30% of clinical cases treated

(2 Patients)

|

Improvement in 30% of clinical cases treated

(2 Patients)

|

| T2B Clinical improvement after 40 days of therapy: probiotic mixture 2 tablet after breakfast/dinner |

Improvement in 50% of clinical cases treated

(2 Patients) |

Improvement in 50% of clinical cases treated

(1 Patient) |

Improvement in 50% of clinical cases treated

(5 Patients)

|

Improvement in 70% of clinical cases treated

(5 Patients)

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).