Submitted:

31 December 2025

Posted:

01 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

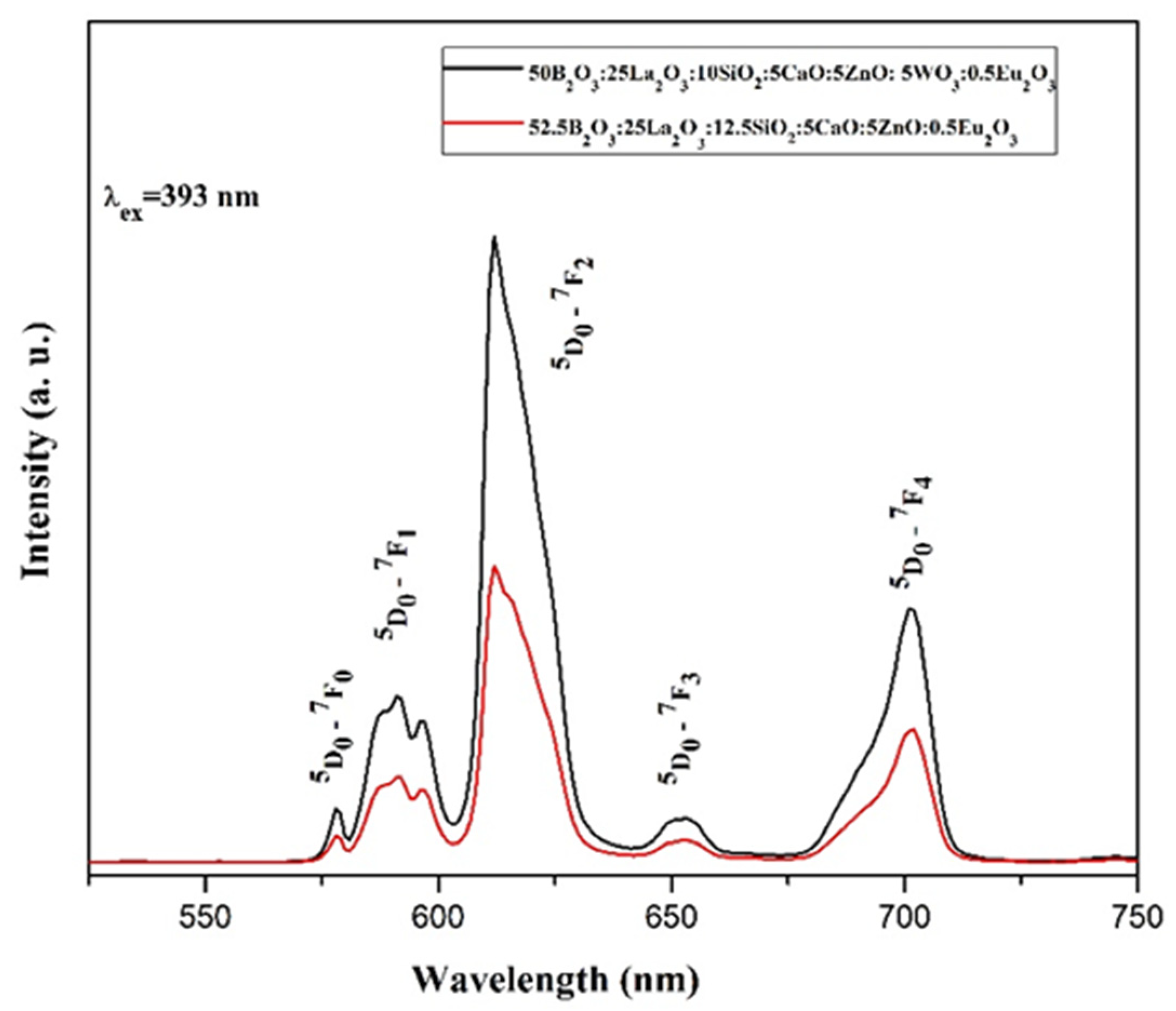

Glasses with compositions 52.5B2O3:12.5SiO2:25La2O3:5CaO:5ZnO:0.5Eu2O3 and50B2O3:10SiO2:25La2O3:5CaO:5ZnO:5WO3:0.5Eu2O3 (mol%) were prepared by conventional melt-quenching method and investigated by X-ray diffraction analyses, DSC analysis, DR-UV-Vis spectroscopy and photoluminescence spectroscopy. Physical properties like density, molar volume, oxygen molar volume and oxygen packing density were also determined. Glasses are characterized with high glass transition temperature (over 650 °C). DR-UV-Vis spectroscopy results indicate that the tungstate ions incorporate into the base borosilicate glass as tetrahedral WO4 groups. The lower band gap energy values show that the introduction of WO3 into the base borosilicate glass increases the number of non-bridging oxygen species in the glass structure. The emission intensity of the Eu3+ ion increases with the introduction of WO3 due to the occurrence of non-radiative energy transfer from the tungstate groups to the active ion. The most intense luminescence peak observed at 612 nm suggest that the glasses are potential materials for red emission.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

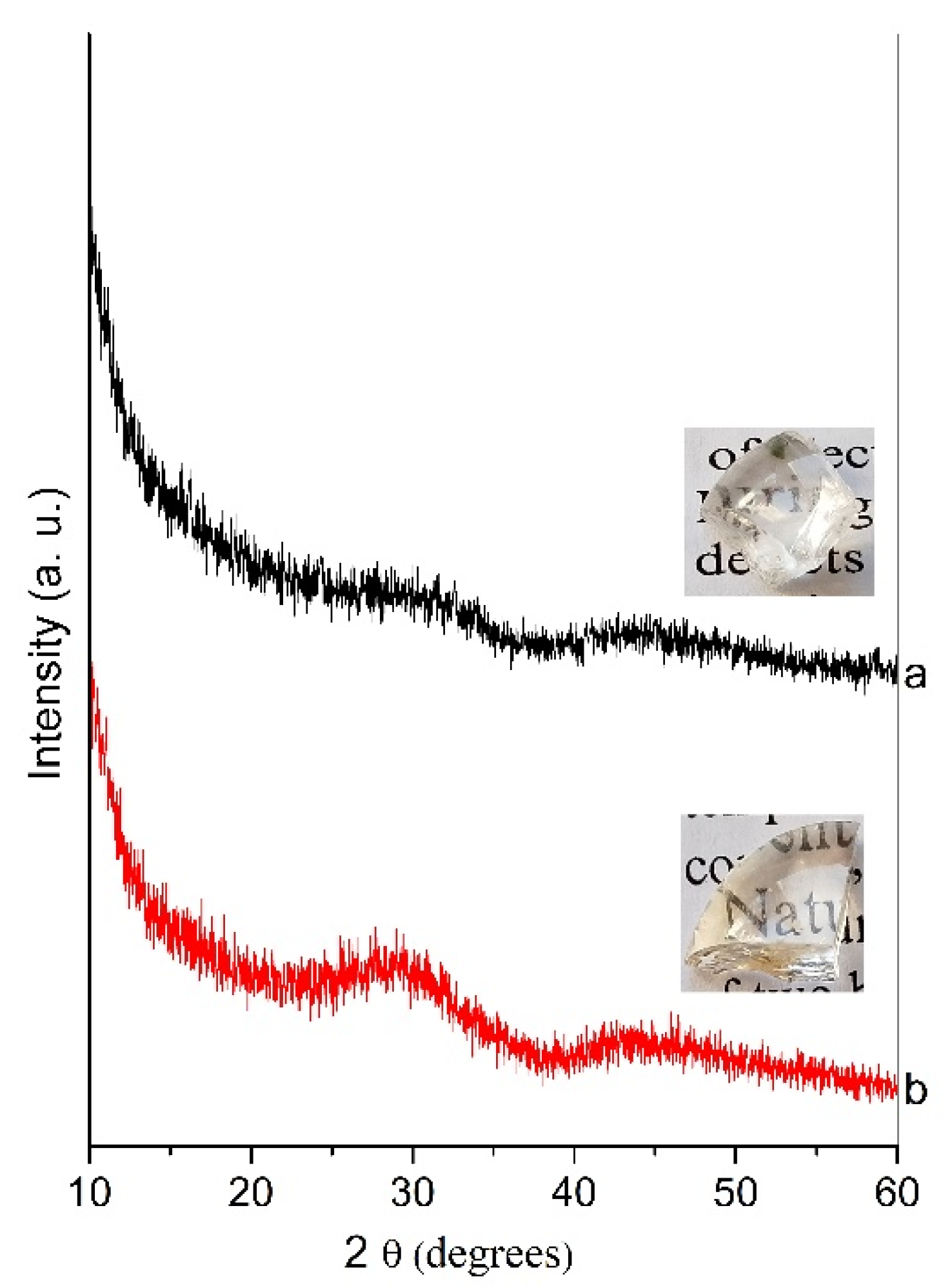

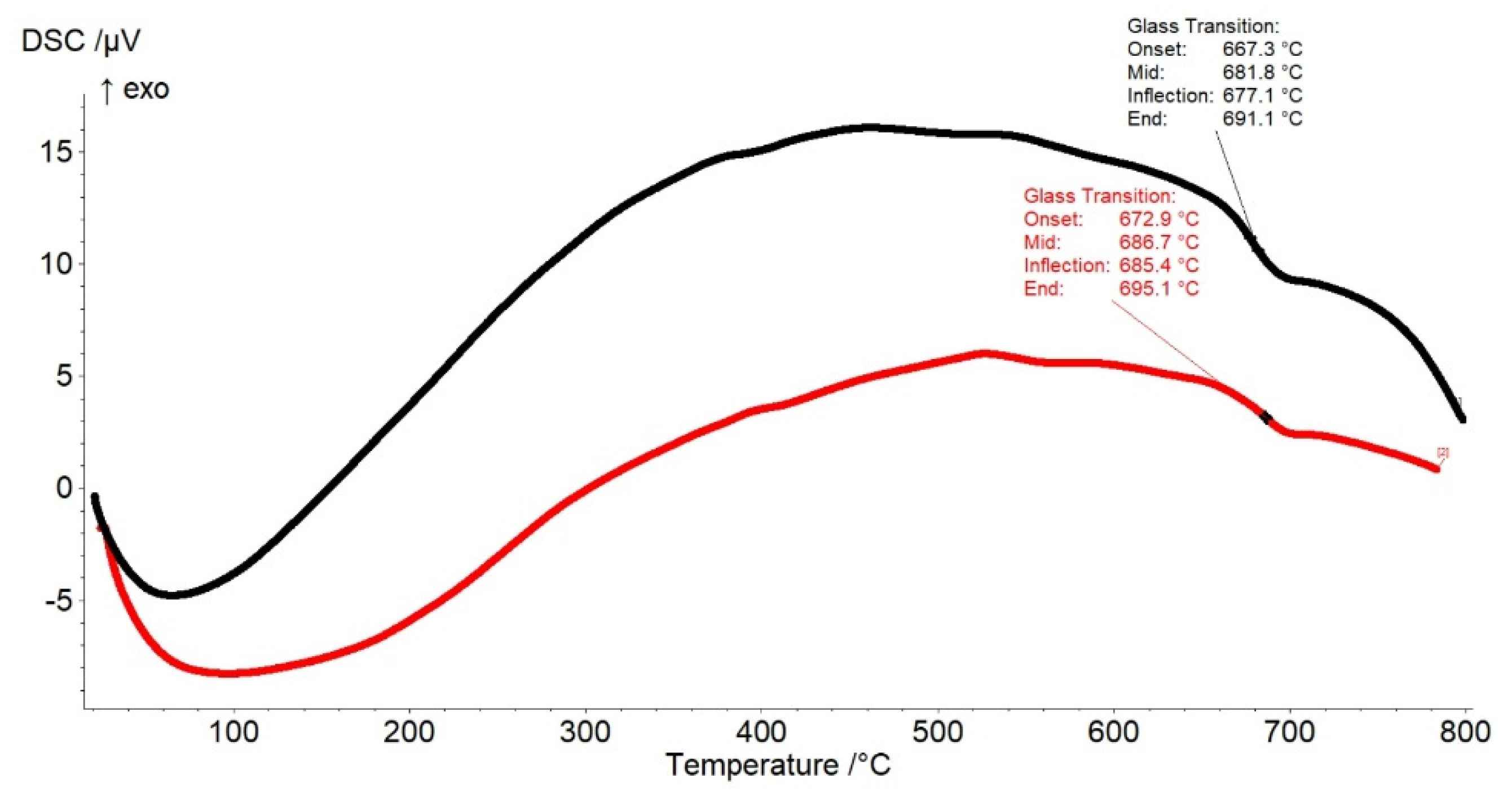

2.1. XRD Data and Thermal Analysis

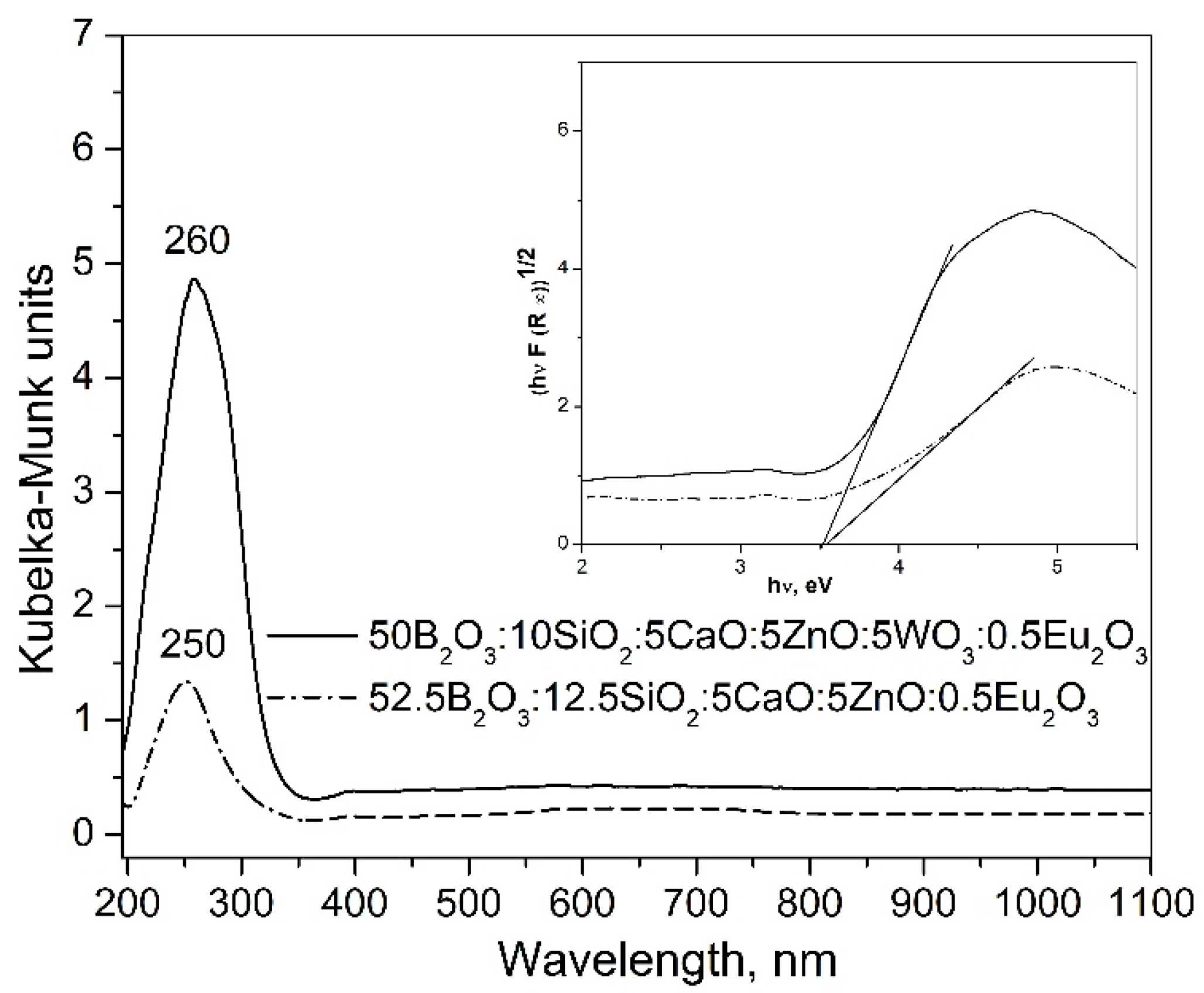

2.2. DR-UV–Vis Spectra

2.3. Density, Molar Volume, Oxygen Packing Density and Oxygen Molar Volume

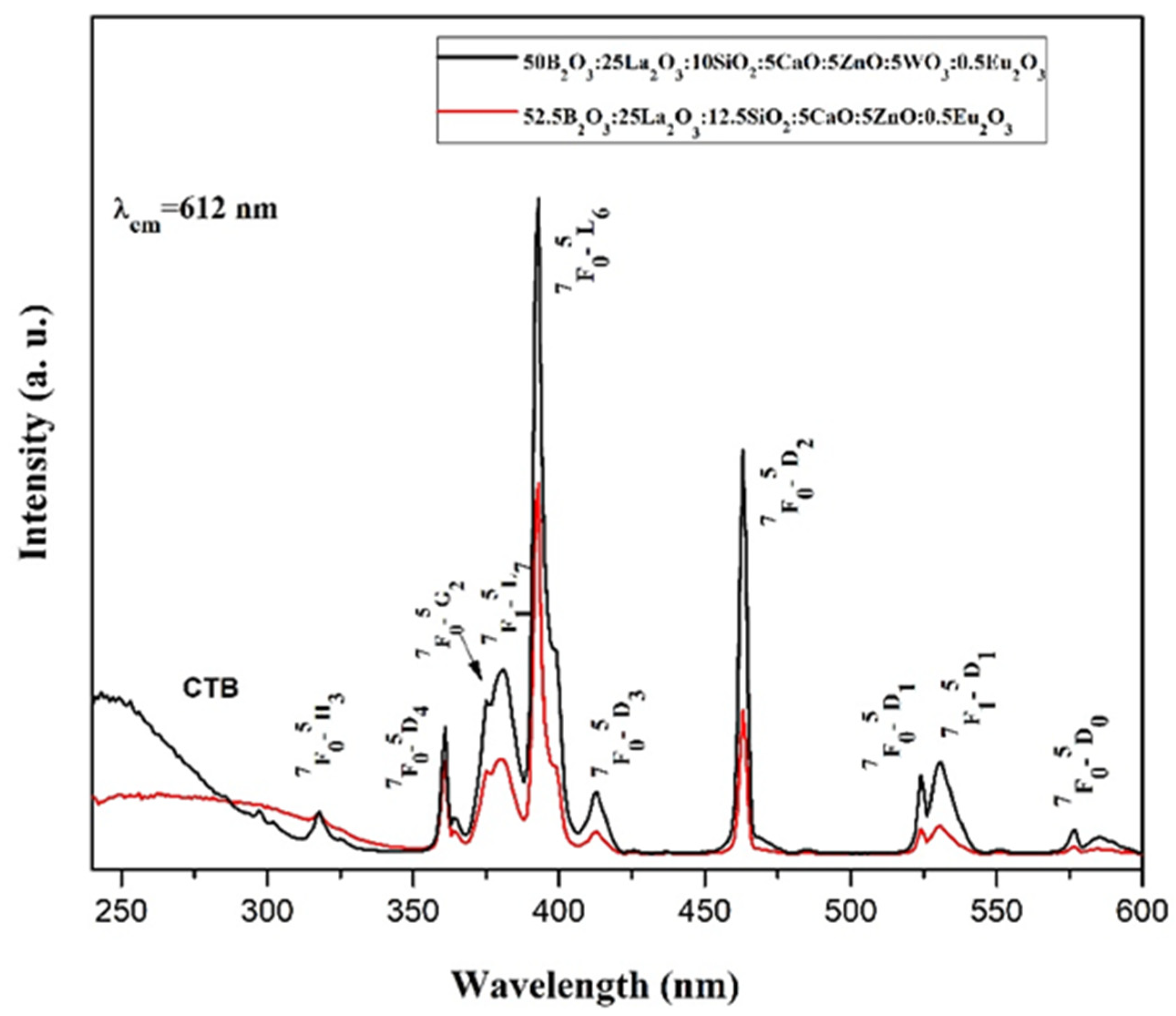

2.4. Photoluminescent Properties

3. Materials and Methods

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Reddy, B.N.K.; Raju, B.D.; Thyagarajan, K.; Ramanaiah, R.; Jho, Y.D.B.; Reddy, S. Optical characterization of Eu3+ ion doped alkali oxide modified borosilicate glasses for red laser and display device applications. Ceram. Int. 2017, 43(12), 8886–8892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakpanicha, S.; Wantana, N.; Kaewkhao, J. Development of bismuth borosilicate glass doped with Eu3+ for reddish orange emission materials application. Mater. Today: Proc. 2017, 4, 6389–6396. [Google Scholar]

- Reddy, B.N.K.; Raju, B.D.; Thyagarajan, K.; Ramanaiah, R.; Jhod, Y.D.; Reddy, B.S. Optical characterization of Eu3+ ion doped alkali oxide modified borosilicate glasses for red laser and display device applications. Ceram. Int. 2017, 43, 8886–8892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, N.S.; Reddy, Y.P.; Buddhudu, S. Luminescence properties of Eu3+ doped ZnO–B2O₃–SiO2 glasses. Spectrosc. Lett. 2002, 35, 275–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheong, W.M.; Zaid, M.H.M.; Matori, K.A.; Fen, Y.W.; Tee, T.S.; Loh, Z.W.; Mayzan, M.Z.H. Promising reddish-orange light as Eu3+ incorporated in zinc-borosilicate glass derived from the waste glass bottle. J. Taibah Univ. Sci. 2023, 17, 2260080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajaj, R.; Rao, A.S.; Prakash, G.V. Photoluminescence down-shifting studies of thermally stable Eu3+ ions doped borosilicate glasses for visible red photonic device applications. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2022, 575, 121184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, G.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, R.; Li, C.; Liu, L.; Lin, H.; Zeng, F.; Su, Z. Regulation of luminescence properties of SBGNA:Eu3+ glass by the content of B2O₃ and Al2O₃. Opt. Mater. 2020, 106, 110025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakpanich, S.; Wantana, N.; Ruangtaweep, Y.; Kaewkhao, J. Eu3+ doped borosilicate glass for solid-state luminescence material. J. Met. Mater. Miner. 2017, 27, 35–38. [Google Scholar]

- Aryal, P.; Kesavulu, C.R.; Kim, H.J.; Lee, S.W.; Kang, S.J.; Kaewkhao, J.; Chanthima, N.; Damdee, B. Optical and luminescence characteristics of Eu3+-doped B2O₃:SiO2:Y2O₃:CaO glasses for visible red laser and scintillation material applications. J. Rare Earths 2018, 36, 482–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravita, A.; Rao, S. Effective sensitization of Eu3+ visible red emission by Sm3+ in thermally stable potassium zinc alumino borosilicate glasses for photonic device applications. J. Lumin. 2022, 244, 118689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Rao, A.S.; Kishore, K. Energy transfer dynamics in thermally stable Sm3+/Eu3+ co-doped AEAlBS glasses for near UV triggered photonic device applications. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2022, 580, 121392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Z.; Zhu, Z. Luminescence and spectroscopic studies on Dy3+–Eu3+ doped SiO2–B2O₃–ZnO–La2O₃–BaO glass for WLED. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2024, 641, 123153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Wang, G.; Zheng, X.; Yu, L.; Zhang, J.; Qiu, Z.; Lian, S. Tunable colors and applications of Dy3+/Eu3+ co-doped CaO–B2O₃–SiO2 glasses. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2019, 102(10), 5890–5898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsafi, K.; Ismail, Y.A.; Aloraini, D.A.; Almutairi, H.M.; Al-Saleh, W.M.; Shaaban, K.S. Exploring the radiation shielding properties of B2O₃–SiO2–ZnO–Na2O–WO₃ glasses: A comprehensive study on mechanical, gamma, and neutron attenuation characteristics. Prog. Nucl. Energy 2024, 170, 105151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.S.; Alrowaily, A.W.; Issa, S.A.; Rashad, M.; Elsaman, R.; Zakaly, H.M. Unveiling the structural, optical, and electromagnetic attenuation characteristics of B2O₃–SiO2–CaO–Bi2O₃ glasses with varied WO₃ content. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 2023, 212, 111089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, N.H. Composition-properties relationship in Inorganic Oxide Glasses. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 1974, 15, 423–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yordanova, A.; Aleksandrov, L.; Milanova, M.; Iordanova, R.; Petrova, P.; Nedyalkov, N. Effect of the Addition of WO3 on the Structure and Luminescent Properties of ZnO-B2O3:Eu3+ Glass. Molecules 2024, 29(11), 2470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ElBatal, F.H.; Selim, M.; Marzouk, S.Y.; Azooz, M.A. UV-vis absorption of the transition metal-doped SiO2-B2O3-Na2O3 glasses. Phys. B 2007, 398, 126–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross-Medgaarden, E.I.; Wachs, I.E. Structural Determination of Bulk and Surface Tungsten Oxides with UV-vis Diffuse Reflectance Spectroscopy and Raman Spectroscopy. J. Phys. Chem. C 2007, 111, 15089–15099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouis, M.; El-Batal, H.A.; Azoz, M.; Abdelghany, A. Characterization of WO3-doped borophosphate glasses by optical, IR and ESR spectroscopic techniques before and after subjecting to gamma irradiation. Indian J. Pure Appl. Phys. 2013, 51, 11–17. [Google Scholar]

- Rani, S.; Sanghi, S.; Ahlawat, N.; Agarwal, A. Influence of Bi2O3 on thermal, structural and dielectric properties of lithium zinc bismuth borate glasses. J. Alloys Comp. 2014, 597, 110–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajaj, A.; Khanna, A.; Kulkarni, N.K.; Aggarwal, S.K. Effects of Doping Trivalent Ions in Bismuth Borate Glasses. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2009, 92, 1036–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saranya, S.; Balakrishnan, L.; Sangeetha, D.; Lakshmi Priya, S. Investigating the effects of Hg doping on WO3 nanoflakes: A hydrothermal route to tailored properties. Dig. J. Nanomater. Biostruct. 2025, 20(2), 669–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Yu, Y.; Cao, C.; Wang, J.; Wang, E.; Cao, Y. The existing states of doped B3+ions on the B doped TiO2. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2015, 345, 67–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevenson, A.J.; Li, X.; Martinez, M.A.; Anderson, J.M.; Suchy, D.L.; Kupp, E.R.; Dickey, E.C.; Mueller, K.T.; Messing, G.L. Effect of SiO2 on Densification and Microstructure Development in Nd:YAG Transparent Ceramics. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2011, 94(5), 1380–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villegas, M.A.; Navarro, J.M.F. Physical and structural properties of glasses in the TeO2–TiO2–Nb2O5 system. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2007, 27(7), 2715–2723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blasse, G.; Grabmaier, B.C. Luminescent Materials, 1st ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelber, Germany, 1994; p. 18. [Google Scholar]

- Hoefdraad, H.E. The charge-transfer absorption band of Eu3+ in oxides. J. Solid State Chem. 1975, 15, 175–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parchur, A.K.; Ningthoujam, R.S. Behaviour of electric and magnetic dipole transitions of Eu3+, 5D0-7F0 and Eu-O charge transfer band in Li+ co-doped YPO4:Eu3+. RSC Adv. 2012, 2, 10859–10868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariselvam, K.; Liu, J. Synthesis and luminescence properties of Eu3+ doped potassium titano telluroborate (KTTB) glasses for red laser applications. J. Lumin. 2021, 230, 117735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nimpoeno, W.A.; Lintang, H.O.; Yuliati, L. Zinc oxide with visible light photocatalytic activity originated from oxygen vacancy defects. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 833, 012080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, P.S.; Khanna, A. Eu3+ activated molybdate and tungstate based red phosphors with charge transfer band in blue region. ECS J. Solid State Sci. Technol. 2013, 2, R3153–R3167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thieme, C.; Herrmann, A.; Kracker, M.; Patzig, C.; Hoche, T.; Russel, C. Microstructure investigation and fluorescence properties of Europium-doped scheelite crystals in glass-ceramics made under different synthesis conditions. J. Lumin. 2021, 238, 118244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunzli, J.C.G. Lanthanide luminescence: From a mystery to rationalization, understanding, and applications. In Handbook on the Physics and Chemistry of Rare Earths; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016; Volume 50, pp. 141–176. [Google Scholar]

- Binnemans, K. Interpretation of europium (III) spectra. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2015, 295, 1–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sungpanich, J.; Thongtem, T.; Thongtem, S. Large-scale synthesis of WO3 nanoplates by a microwave-hydrothermal method. Ceram. Int. 2012, 38, 1051–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nimpoeno, W.A.; Lintang, H.O.; Yuliati, L. Zinc oxide with visible light photocatalytic activity originated from oxygen vacancy defects. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 833, 012080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devi, C.H.B.; Mahamuda, S.; Swapna, K.; Venkateswarlu, M.; Rao, A.S.; Prakash, G.V. Compositional dependence of red luminescence from Eu3+ ions doped single and mixed alkali fluoro tungsten tellurite glasses. Opt. Mater. 2017, 73, 260–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogami, M.; Umehara, N.; Hayakawa, T. Effect of hydroxyl bonds on persistent spectral hole burning in Eu3+ doped BaO-P2O5 glasses. Phys. Rev. B 1998, 58, 6166–6171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dejneka, M.; Snitzer, E.; Riman, R.E. Blue, green and red fluorescence and energy transfer of Eu3+ in fluoride glasses. J. Lumin. 1995, 65, 227–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yordanova, A.; Milanova, M.; Iordanova, R.; Fabian, M.; Aleksandrov, L.; Petrova, P. Network Structure and Luminescent Properties of ZnO–B2O3–Bi2O3–WO3: Eu3+ Glasses. Materials 2023, 16(20), 6779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milanova, M.; Aleksandrov, L.; Yordanova, A.; Iordanova, R.; Tagiara, N.S.; Herrmann, A.; Gao, G.; Wondraczek, L.; Kamitsos, E.I. Structural and luminescence behavior of Eu3+ ions in ZnO-B2O3-WO3 glasses. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2023, 600, 122006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iordanova, R.; Milanova, M.; Yordanova, A.; Aleksandrov, L.; Nedyalkov, N.; Kukeva, R.; Petrova, P. Structure and Luminescent Properties of Niobium-Modified ZnO-B2O3:Eu3+ Glass. Materials 2024, 17, 1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oomen, E.W.J.L.; Dongen, A.M.A. Europium (III) in oxide glasses: Dependence of the emission spectrum upon glass composition. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 1989, 111, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettinelli, M.; Speghini, A.; Ferrari, M.; Montagna, M. Spectroscopic investigation of zinc borate glasses doped with trivalent europium ions. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 1996, 201, 211–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annapurna, K.; Das, M.; Kundu, M.; Dwivedhi, R.N.; Buddhudu, S. Spectral properties of Eu3+: ZnO–B2O3–SiO2 glasses. J. Mol. Struct. 2005, 741, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, B.N.K.; Raju, B.D.; Thyagarajan, K.; Ramanaiah, R.; Jho, Y.D.; Reddy, B.S. Optical characterization of Eu3+ ion doped alkali oxide modified borosilicate glasses for red laser and display device applications. Ceram. Int. 2017, 43(12), 8886–8892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azeem, P.A.; Kalidasan, M.; Gopal, K.R.; Reddy, R.R. Spectral analysis of Eu3+: B2O3–Al2O3–MF2 (M= Zn, Ca, Pb) glasses. J. Alloys Compd. 2009, 474(1-2), 536–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajaj, R.; Rao, A.S.; Prakash, G.V. Photoluminescence down-shifting studies of thermally stable Eu3+ ions doped borosilicate glasses for visible red photonic device applications. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2022, 575, 121184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandyala, S.H.; Hungerford, G.; Santos, J.D.; Walsh, B.M.; Di Silvio, L.; Stamboulis, A. Time-resolved and excitation-emission matrix luminescence behaviour of boro-silicate glasses doped with Eu3+ ions for red luminescent application. Mater. Res. Bull. 2021, 140, 111340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Chen, B.; Sun, B.; Zhang, J.; Lu, S. Ultraviolet light-induced spectral change in cubic nanocrystalline Y2O3: Eu3+. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2003, 372(3-4), 368–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabir, M.; Ghahari, M.; Afarani, M.S. Co-precipitation synthesis of nano Y2O3: Eu3+ with different morphologies and its photoluminescence properties. Ceram. Int. 2014, 40(7), 10877–10885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Zhang, F.; Wu, L.; Yi, H.; Wang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, J. Structure refinement and one-center luminescence of Eu3+ activated ZnBi2B2O7 under UV excitation. J. Alloys Compd. 2015, 648, 500–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binnemans, K.; Gorller-Walrand, C. Application of the Eu3+ ion for site symmetry determination. J. Rare Earths 1996, 14, 173–180. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, T.; Guild, J. The CIE colorimetric standards and their use. Trans. Opt. Soc. 1931, 33, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paolini, T.B. SpectraChroma (Version 1.0.1) [Computer Software]. 2021. Available online: https://zenodo.org/records/4906590 (accessed on 7 June 2021).

- Trond, S.S.; Martin, J.S.; Stanavage, J.P.; Smith, A.L. Properties of Some Selected Europium—Activated Red. J. Electrochem. Soc. 1969, 116, 1047–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Glass Composition | Relative Intensity Ratio, R | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| 52.5B2O3:25La2O3:12.5SiO2:5CaO:5ZnO:0.5Eu2O3 | 4.12 | Current work |

| 50B2O3:25La2O3:10SiO2:5CaO:5ZnO:5WO3:0.5Eu2O3 | 4.42 | Current work |

| 50ZnO:(49–x)B2O3:1Bi2O3:xWO3: 0.5Eu2O3 x = 1, 5, 10, | 4.61-5.73 | 41 |

| 50ZnO:40B2O3:10WO3:xEu2O3 (0≤x≤10) | 4.54÷5.77 | 42 |

| 50ZnO:(50–x)B2O3:xNb2O5:0.5Eu2O3:, x= 0, 1, 3 and 5 mol% | 4.31-5.16 | 43 |

| 50ZnO:(50−x)B2O3:0.5Eu2O3:xWO3, x = 0, 1, 3, 5. | 4.34-5.57 | 17 |

| 89.5B2O3–10Li2O–0.5Eu2O3 64SiO2-16K2O-16BaO-4Eu2O3 0.5GeO2-63.5SiO2-16K2O-16BaO-4Eu2O3 |

2.41 3.42 3.46 |

44 |

| 4ZnO:3B2O3 0.5–2.5 mol % Eu2O3 | 2.74-3.94 | 45 |

| 60ZnO:20B2O3:(20 − x)SiO2−xEu2O3 (x = 0 and 1) | 3.166 | 46 |

| 74.5 B2O3+10SiO2+5 MgO+5x+0.5 Eu2O3, x= Li2O+Na2O; Li2O+K2O and K2O+Na2O | 2.102-2.266 | 47 |

| 20 MF2·69 B2O3·10 Al2O3·1Eu2O3, M = Ca, Pb and Zn | 3.77-5.89 | 48 |

| 35B2O3–20SiO2-(15-x) Al2O3–15ZnO-15Na2CO3-xEu2O3 (x = 0.0, 0.5, 1.0, 1.5, 2.0, 2.5 mol%) | 3.62–3.92 | 49 |

| 50B2O3-19SiO2-20Na2O-10CaO-1Eu2O3 50B2O3-14SiO2-20Na2O-10CaO-5ZnO-1Eu2O3 50B2O3-14SiO2-20Na2O-10CaO-5TeO2-1Eu2O3 |

3.151 3.352 4.269 |

50 |

| Eu3+:Y2O3 | 3.8-5.2 | 51, 52 |

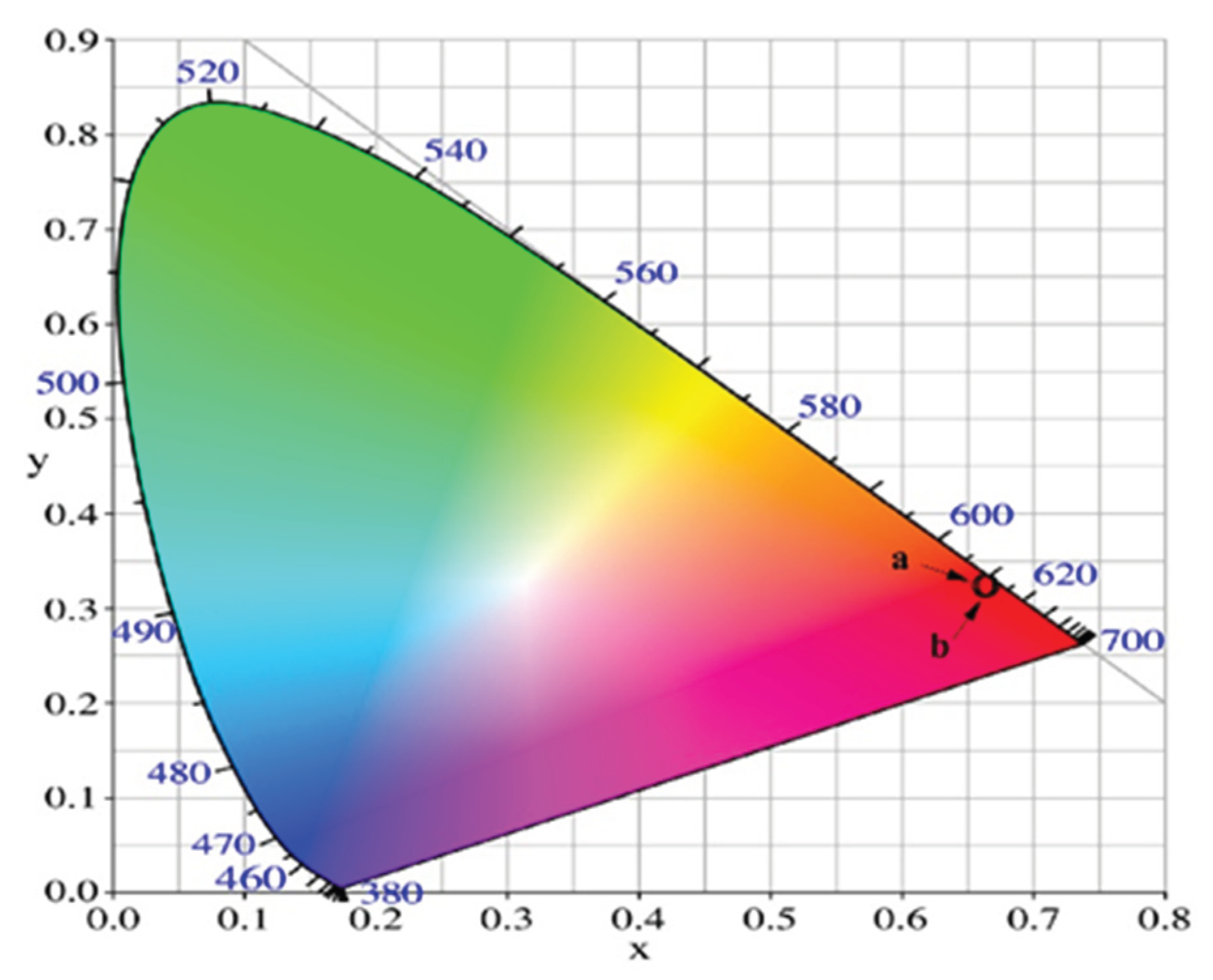

| Glass Composition | Chromaticity Coordinates (x, y) |

|---|---|

| 52.5 B2O3:25La2O3:12.5SiO2:5CaO:5ZnO:0.5Eu2O3 | 0.649, 0.348 |

| 50B2O3:25La2O3:10SiO2:5CaO:5ZnO:5WO3:0.5Eu2O3 | 0.652, 0.348 |

| NTSC standard for red light | 0.670, 0.330 |

| Y2O2S:Eu3+ | 0.658, 0.340 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.