Submitted:

31 December 2025

Posted:

02 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Some Principles to the Roles of ATRA and RARs

3. RARγ Agonism Blocks the Development of Stem/Progenitor Cells

4. RARγ Agonism Enhances the Generation of Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs)

5. RARγ Is a Cofactor to Other Transcription Factors

6. RARγ Agonism or Overexpression Enhances the Proliferation of Cancer Cells

7. RARγ Antagonism Kills Cancer Cells Including CSCs

8. The Role of RARγ Is Multifaceted

9. Concluding Remarks

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bonnet, D.; Dick, J.E. Human acute myeloid leukemia is organized as a hierarchy that originates from a primitive hematopoietic cell. Nat. Med. 1997, 3, 730–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, X.; Tian, W.; Ning, J.; Xiao, G.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhai, Z.; Tanzhu, G.; Yang, J.; Zhou, R. Cancer stem cells: Advances in knowledge and implications for cancer therapy. Sig. Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fialkow, P.J.; Denman, A.M.; Jacobson, G.J.; Lowenthal, M.N. Chronic myelocytic leukemia: Origin of some lymphocytes from leukemic stem cell. J. Clin. Invest. 1978, 62, 815–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graham, S.M.; Jorgensen, H.G.; Allan, E.; Pearson, C.; Alcorn, M.J.; Richmond, L.; Holyoake, T.L. Primitive, quiescent, Philadelphia-positive stem cells from patients with chronic myeloid leukemia are insensitive to STI571 in vitro. Blood 2002, 99, 319–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corbin, A.S.; Agarwal, A.; Loriaux, M.; Cortes, J.; Deininger, M.W.; Druker, B.J. Human chronic myeloid leukemia stem cells are insensitive to imatinib despite inhibition of BCR-ABL activity. J. Clin. Invest. 2011, 121, 396–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, Z.; Brand, R.; Martino, R.; van Biezen, A.; Finke, J.; Bacigalupo, A.; Beelen, D.; Devergie, A.; Alessandrino, E.; Willemze, R.; et al. Allogeneic hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation for patients 50 years or older with myelodysplastic syndromes or secondary acute myeloid leukemia. J. Clin. Oncol. 2010, 28, 405–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiozawa, Y.; Pienta, K.J.; Morgan, T.M.; Taichman, R.S. Cancer stem cells and their role in metastasis. Pharmacol. Ther. 2013, 138, 285–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, C-Q.; Jeong, Y.; Fu, M.; Bookout, A.L.; Garcia-Barrio, M. T.; Sun, T.; Kim, B-h.; Xie, Y.; Root, S.; Zhang, J; et al. Expression profiling of nuclear receptors in human and mouse embryonic stem cells. Mol. Endocrinol. 2009, 23, 724–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Thé, H.; Pandolfi, P.P.; Chen, Z. Acute promyelocytic leukemia: A paradigm for oncoprotein-targeted cure. Cancer Cell. 2017, 32, 552–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Testa, U.; Pelosi, E. Function of PML-RARA in acute promyelocytic leukemia. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2024, 1459, 321–339. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Thompson, A.; Quinn, M.F.; Grimwade, D.; O’Neill, C. M.; Ahmed, M.R.; Grimes, S.; McMullin, M.F.; Cotter, F.; Lappin, T.R.J. Global down-regulation of HOX gene expression in PML-RARa+ acute promyelocytic leukemia identified by small-array real-time PCR. Blood 2003, 101, 1558–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinelli, A.; Bossi, D.; Pelicci, P.G.; Minucci, S. A redundant potential of the retinoic receptor (RAR) a, b, and g isoforms in acute promyelocytic leukemia. Leukemia 2002, 21, 647–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conserva, M.R.; Redavid, I.; Anelli, L.; Zagaria, A.; Specchia, G.; Albano, F. RARG gene dysregulation in acute myeloid leukemia. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2019, 6, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Zhao, L.; Tan, Y.; Cen, X.; Gao, H.; Jiang, H.; Liu, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, T.; Zhao, C.; et al. Oncogenic role of RARG rearrangements in acute myeloid leukemia resembling acute promyelocytic leukemia. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, T.; Weng, T.; Qi, L.; Liu, Y.; Shen, M.; Wong, F.; Fang, Y.; Liu, S.; Wen, L.; Chen, S.; et al. CPSF-6-RARγ interacts with histone deacetylase 3 to promote myeloid transformation in RARG-fusion acute myeloid leukemia. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, G. Deregulation of all-trans retinoic acid signalling and development in cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 12089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stanger, B.Z.; Wahl, G.M. Cancer as a disease of development gone awry. Annu. Rev. Pathol. Mech. Dis. 2023, 19, 397–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thong, T.; Forte, C.A.; Hill, E.M.; Colacino, J.A. Environmental exposures, stem cells, and cancer. Pharmacol. Ther. 2019, 204, 107398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shannan, S.R.; Moise, A.R.; Trainor, P.A. News insights and challenging paradigms in the regulation of vitamin A metabolism in development. Wiley Interdiscip. Rep. Dev. Biol. 2017, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baltes, S.; Nau, H.; Lampen, A. All-trans retinoic acid enhances differentiation and influences permeability of intestinal Caco-2 cells under serum free conditions. Dev. Growth Differ. 2004, 46, 503–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, G.; Marchwicka, A.; Cunningham, A.; Toellner, K-M.; Marcinkowksa, E. Antagonising retinoic acid receptors increases myeloid cell production by cultured hematopoietic stem cells. Arch. Immunol. Ther. Exp. (Warsz) 2017, 65, 69–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Idres, N.; Marill, J.; Flexer, M.A.; Chabot, G.G. Activation of retinoic acid receptor-dependent transcription by all-trans-retinoic acid metabolites and isomers. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 31491–31498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farboud, B.; Hauksdottir, H.; Wu, Y.; Privalsky, M.L. Isotype-restricted corepressor recruitment: a constitutively closed Helix 12 conformation in retinoic acid receptors b and g interferes with corepressor recruitment and prevents transcriptional repression. Mol. Cell Biol. 2003, 23, 2844–2858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawksdottir, H.; Farboud, B.; Privalsky, M.L. Retinoic acid receptors b and g do not repress, but instead activate target gene transcription in both the absence and presence of hormone ligand. Mol. Endocrinol. 2003, 17, 373–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lehmann, J.M.; Zhang, X-K.; Pfahl, M. RAR72 expression is regulated through a retinoic acid response element embedded in Sp1 sites. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1992, 12, 2976–2985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engberg, N.; Kahn, M.; Peterson, D. R.; Hanson, M.; Serup, P. Retinoic acid synthesis promotes development of neural progenitors from mouse embryonic stem cells by suppressing endogenous Wnt-dependent nodal signaling. Stem Cells 2010, 28, 1498–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taneja, R.; Ray, B.; Plassat, J.L. Cell-type and promoter-context dependent retinoic acid receptor (RAR) redundancies for RARbeta2 and Hoxa-1 activation in F9 and P19 cells can be artefactually generated by gene knockouts. Proc Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1996, 93, 6197–6202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsukada, M.; Schroder, M.; Seltmann, H.; Orfanos, C.E.; Zouboulis, C.C. High albumin levels restrict the kinetics of 13-cis retonic acid uptake and intracellular isomerization into all-trans retinoic acid and inhibit its anti-proliferative effect on SZ95 sebocytes. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2002, 119, 182–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belatik, A.; Hotchandani, S.; Bariyanga, J.; Tajmir-Riahi, H.A. Binding sites of retinol and retinoic acid with serum albumins. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2012, 48, 114–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czuba, L.C.; Zhang, G.; Yabat, K.; Isoherranen, N. Analysis of vitamin A and retinoids in biological matrices. Methods Enzymol. 2020, 637, 309–340. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hughes, P.J.; Zhao, Y.; Chandraratna, R.A.; Brown, G. Retinoid-mediated stimulation of steroid sulfatase activity in myeloid leukemic cell lines requires RARa and RXR and involves the phosphinositide 3-kinase and ERK-MAP kinase pathways. J. Cell. Biochem. 2006, 97, 327–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunce, C.M.; Wallington, L.A.; Harrison, P.; Williams, G.R.; Brown, G. Treatment of HL60 cells with various combinations of retinoids and 1 alpha, 25 dihydroxyvitamin D3 results in differentiation towards neutrophils or monocytes or a failure to differentiate and apoptosis. Leukemia 1995, 9, 410–418. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jian, P.; Li, Z.; Fang, T.; Jian, W.; Zhuan, Z.; Mei, L.; Yan, W.; Jian, N. Retinoic acid induces HL-60 differentiation via the upregulation of miR-663. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2011, 4, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, S.J. The HL-60 promyelocytic leukaemic cell line: proliferation, differentiation, and cellular oncogene expression. Blood 1987, 70, 1233–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaser, T.; La Banca de Oliveira, S.; Cheffer, A.; Beco, R.; Martins, P.; Fornazari, M.; Lameu, C; Junior, H.M.C.; Coutino-Silva, R. Modulation of mouse embryonic stem cell proliferation and neural differentiation by the PZX7 receptor. PLoS One 2014, 9, e96281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, Z-Y.; Shan, J-L.; Li, Q-M.; Wang, Y.; Huang, X-Y.; Guo, T-Y.; Liu, H-W.; Lei, L.; Jin, L-H. pCREB is involved in neural induction of mouse embryonic stem cells. Anat. Rec. 2008, 291, 519–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rhinn, M.; Dolle, P. Retinoic acid signalling during development. Development 2012, 139, 843–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howard, W.B.; Willhite, C.C. Toxicity of retinoids in humans and animals. J. Toxicol. Toxin Rev. 1986, 5, 55–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudhud, L.; Chisholm, D.R.; Whiting, A.; Steib, A.; Pohoczky, K.; Kecskes, A.; Szoke, E.; Helyes, Z. Synthetic diphenylacetylene-based retinoids induce DNA damage in Chinese hamster ovary cells without altering viability. Molecules 2022, 27, 977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, G.S.; Liao, X.; Shimizu, H.; Collins, M.D. Genetic and pathological aspects of retinoic acid-induced limb malformations in the mouse. Birth Defects Res. A Clin. Mol. Teratol. 2010, 88, 863–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zile Maija, H. Function of vitamin A in vertebrate embryonic development. J. Nutr. 131, 705–708. [CrossRef]

- Lohnes, D.; Mark, M.; Mendelsohn, C.; Colle, P.; Dierich, A.; Gorry, P.; Gansmuller, A.; Chambon, O. Function of retinoic acid receptors (RARs) during development: (1) craniofacial and skeletal abnormities in RAR double mutants. Development 1994, 120, 2723–2748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruberte, E.; Dolle, P.; Krust, A.; Zelent, A.; Morris-Kay, G.; Chambon, P. Specific spatial and temporal distribution of retinoic acid receptor gamma transcripts during mouse embryogenesis. Development 1990, 108, 213–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waxman, J.S.; Yelon, D. Comparison of the expression patterns of newly identified zebrafish retinoic acid and retinoid X receptors. Dev. Dyn. 2007, 236, 587–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hale, L.A.; Tallafuss, A.; Yan, Y.-L.; Dudley, L.; Eisen, J.S.; Postlethwait, J.H. Characterization of the retinoic acid receptor genes raraa, rarab and rarg during zebrafish development. Gene Expr. Patterns 2006, 6, 546–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elder, J.T.; Fisher, G.J.; Zhang, Q.Y.; Eisen, D.; Krust, A.; Kastner, P.; Chambon, P.; Voorhoes, J.J. Retinoic acid receptor expression in human skin. J. Invest. Dermatol. 1991, 96, 425–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finzi, E.; Blake, M.J.; Celano, P.; Skouge, J.; Diwan, R. Cellular localization of retinoic acid receptor-g expression in normal and neoplastic skin. Am. J. Pathol. 1992, 140, 1463–1471. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gericke, J.; Ittensohn, J.; Mihaly, J.; Alvarez, S.; Alvarez, R.; Torocsik, D.; de Lera, A.; Ruhl, R. Regulation of retinoid-mediated signaling involved in skin homeostasis by RAR and RXR agonists/antagonists in mouse skin. PLoS One 2013, 8, e62643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

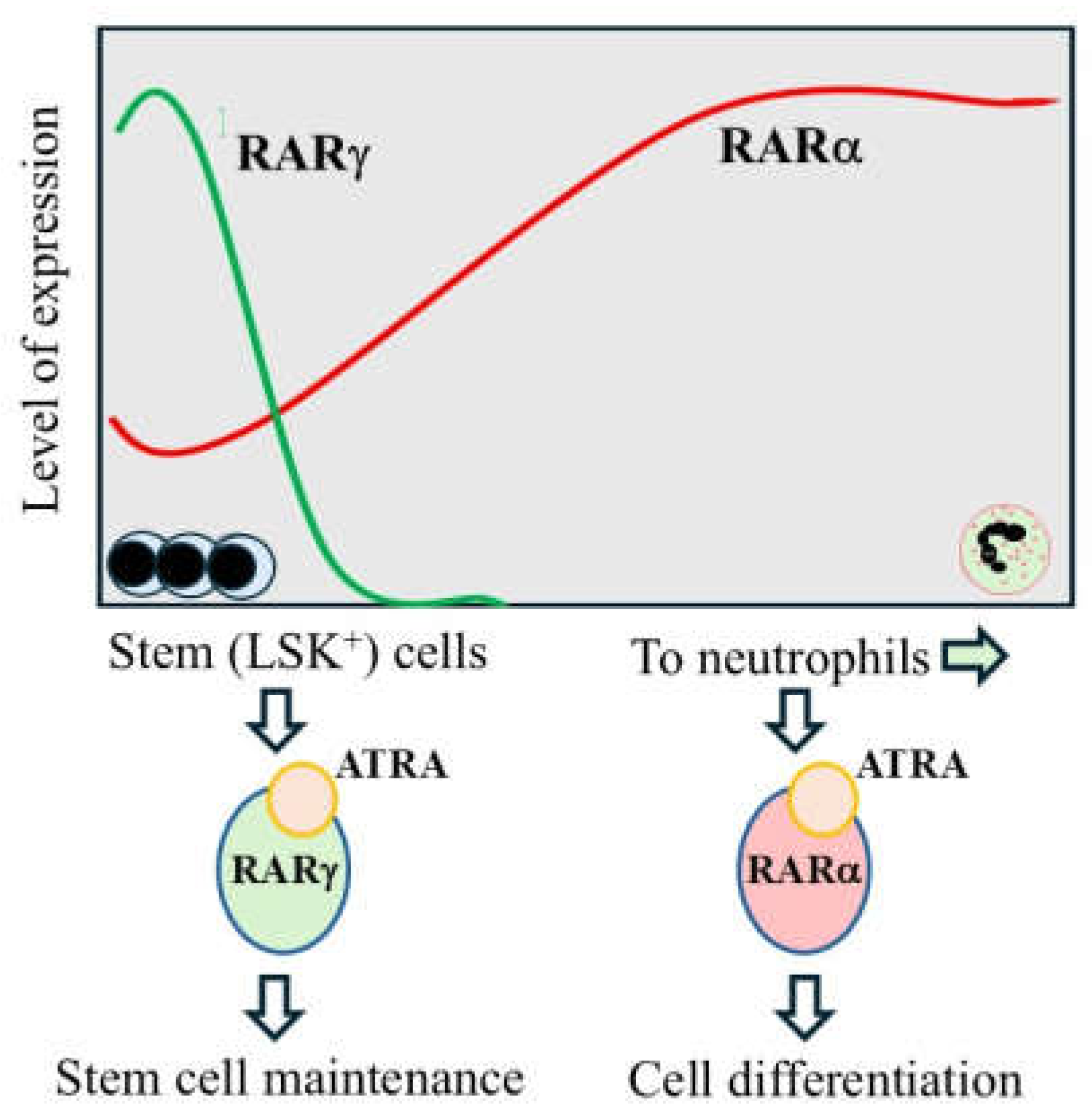

- Purton, L.E.; Dworkin, S.; Olsen, G.H.; Walkley, C.R.; Fabb, S.A.; Collins, S.J.; Chambon, P. RARγ is critical for maintaining a balance between hematopoietic stem cell self-renewal and differentiation. J. Exp. Med. 2006, 203, 1283–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kastner, P.; Chan, S. Function of RARa during the maturation of neutrophils. Oncogene 2001, 20, 7178–7185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, J.; Heyworth, C.M.; Glasgow, A.; Huang, Q.H.; Petrie, K.; Lanotte, M.; Benoit, G.; Gallagher, R.; Waxman, S.; Enver, T.; et al. Lineage restriction of the RARalpha gene expression in myeloid differentiation. Blood 2001, 98, 2563–2567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chee, L.H.Y.; Hendy, J.; Purton, L.E.; McArthur, G.A. The granulocyte-colony stimulating factor receptor (G-CSFR) interacts with retinoic acid receptors (RARs) in the regulation of myeloid differentiation. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2013, 93, 235–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaufmann, K.B.; Zeng, A.G.X.; Coyaud, E.; Garcia-Prat, L.; Papalexi, E.; Murison, A.; Laurent, R.M.N.; Chan-Seng-Yue, M.; Gan, O.L.; Pau, K; et al. A latent subset of hematopoietic stem cells resists regenerative stress to preserve stemness. Nat. Immunol. 2021, 22, 723–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Galen, P.; Mbong, N.; Kreso, A.; Schoof, E.M.; Wagenblast, E.; Ng, S.W.K.; Krivdova, G.; Jin, L.; Nakauchi, H.; Dick, J.E. Integrated stress response activity marks stem cells in normal haematopoiesis and leukemia. Cell Rep. 2018, 25, 1109–1117.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gery, S.; Park, G.J.; Vuong, P.T.; Chun, D.J.; Lemp, N.; Koeffler, H. P. Retinoic acid regulates C/EBP homologous protein expression (CHOP), which negatively regulates myeloid target genes. Blood 2004, 104, 3911–3917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melis, M.; Trasino, S.E.; Tang, X-H.; Rappa, A.; Zhang, T.; Qin, L.; Gudas, L.J. Retinoic acid receptor b loss in hepatocytes increases steatosis and elevates the integrated stress response in alcohol-associated liver disease. Int. J. Mol Sci. 2023, 24, 12035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neill, G.; Masson, G.R. A stay of execution: ATF4 regulation and potential outcomes for the integrated stress response. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2023, 16, 1112253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wai, H.A.; Kawakami, K.; Wada, H.; Muller, F.; Vernalis, A.B.; Brown, G.; Johnson, W.E.B. The development and growth of tissues derived from cranial neural crest and primitive mesoderm is dependent on the ligation status of retinoic acid receptor γ: Evidence that retinoic acid receptor γ functions to maintain stem/progenitors in the absence of retinoic acid. Stem Cells Dev. 2015, 24, 507–518. [Google Scholar]

- Leerberg, D.M.; Hopton, R.E.; Draper. B.W. Fibroblast growth factor receptors function redundantly during zebrafish development. Genetics 2019, 1301–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, S.R.; Lee, Y.; Poss, K.D.; Yelon, D. Reiterative roles for FGF signaling in the establishment of size and proportion of the zebrafish heart. Dev. Biol. 2008, 321, 397–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimono, K.; Tung, W-e.; Maolino, C.; Chi, A.H.-T.; Didizian, J.H.; Mundy, C.; Chandraratna, R.A.; Mishina, Y.; Enomoto-Iwamoto, M.; Pacifici, M.; et al. Potent inhibition of heterotopic ossification by nuclear receptor-g agonists. Nat. Med. 2011, 17, 454–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janesick, A.; Nguyen, T.T.L.; Aisaki, K.-i.; Igarashi, K.; Kitajima, S.; Chandraratna, R.A.S.; Kanno, J.; Blumberg, B. Active repression by RARγ signalling is required for vertebrate axial elongation. Development 2014, 141, 2260–2270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Yang, J.; Liu, P. Rapid and efficient reprogramming of somatic cells into induced pluripotent stem cells by retonic acid receptor gamma and liver receptor homolog 1. 2011. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 18283–18288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Wang, W.; Ooi, J.; Campos, L.S.; Lu, L.; Liu, P. Signalling through retinoic acid receptors is required for reprogramming of both mouse embryonic fibroblast cells and epiblast stem cells to induced pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cells 2015, 33, 1390–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, K.; Yu, M.; Wang, H.; Zhao, P.; Zhao, G.; Zeng, W.; Chen, C.; Wang, Y.; Wang, A.; et al. Canonical and noncanonical Wnt signalling: multilayered mediators, signalling mechanisms and major signalling crosstalk. Genes Dis. 2024, 11, 103–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katoh, M. Regulation of WNT signalling molecules by retinoic acid during neuronal differentiation of NT2 cells: the threshold model of WNT action. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2002, 10, 683–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Gao, J.; Liao, Y.; Tang, S.; Lu, F. Retinoic acid alters the proliferation and survival of the epithelium and mesenchyme and suppresses Wnt/b-catenin signalling in the developing cleft palate. Cell Death Dis. 2013, 4, e898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiesinger, A.; Boink, G.J.J.; Christoffels, V.M.; Devalla, H.H. Retinoic acid signaling in heart development: Application in the differentiation of cardiovascular lineages from human pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cell Rep. 2012, 16, 2589–2606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, L.; Wang, F-y.; Zhang, W.; Wang, X.; Tang, Y-h.; Wang, T.; Chen, Y-t.; Huang, C-x. RA signalling pathway combined with Wnt signalling pathway regulates human induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs) differentiation to sinus node-like cells. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2022, 13, 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taei, A.; Kiani, T.; Taghizadeh, Z.; Moradi, S.; Samadian, A.; Mollamohammadi, S.; Sharifi-Zarchi, A.; Guenther, S.; Akhlaghpour, A.; Asgari, B.; et al. Temporal activation of LRH-1 and RAR-g in human pluripotent stem cells induces a functional naïve-like state. EMBO Rep. 2020, 21, EMBR2018475332020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mullen, A.C.; Wrana, J.L. TGF-β family signaling in embryonic and somatic stem-cell renewal and differentiation. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2017, 9, a022186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Kopp, J. Retinoic and TGFb families: Crosstalk in development, neoplasia, immunity and tissue repair. Semin. Nephrol. 2012, 32, 287–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brons, I.G.M.; Smithers, L.E.; Trotter, M.W.B.; Rugg-Gunn, P.; Sun, B.; Chuva de Sousa Lopes, S.M.; Howlett, S.K.; Clarkson, A.; Ahrlund-Richter, L.; Pedersen, R.A.; et al. Derivation of pluripotent epiblast stem cells from mammalian embryos. Nature 2007, 448, 191–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, D.; Levine, A.J.; Besser, D.; Hemmati-Brivanlou, A. TGFb/activin/nodal signalling is necessary for the maintenance of pluripotency in human embryonic stem cells. Development 2005, 132, 1273–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vallier, L.; Mendjan, S.; Brown, S.; Chng, Z.; Teo, A.; Smithers, L.E.; Trotter, M.W.B.; Cho, C.H.H.; Martinez, A.; Rugg-Gunn, P.; et al. Activin/Nodal signalling maintains pluripotency by controlling Nanog expression. Development 2009, 136, 1339–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osnato, A.; Brown, S.; Krueger, C.; Andrews, S.; Collier, A.J.; Nakanoh, S.; Londono, M.Q.; Wesley, B.T.; Muraro, D.; Brumm, S.; et al. TGFb is required to maintain pluripotency of human naïve pluripotent stem cells. eLife 2012, 10, e67259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Massague, J. TGFb in cancer. Cell 2008, 134, 215–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, H.; Hejna, M.; Liu, Y.; Percharde, M.; Wossidlo, M.; Blouin, L.; Durruthy-Durruthy, J.; Wong, P.; Qi, Z.; Yu, J.; et al. YAP induces human naive pluripotency. Cell Rep p 14, 2301–2312. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tollervey, J.R.; Lunyak, V.V. Judge, jury and executioner of stem cell fate. Epigenetics 2012, 7, 823–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kashyap, V.; Gudas, L.J.; Brenet, F.; Funk, P.; Viale, A.; Scandura, J.M. Epigenetic reorganization of the clustered Hox genes in embryonic stem cells induced by retinoic acid. J Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 3250–3260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kashyap, V.; Laursen, K.B.; Brenet, F.; Viale, A.J.; Scandura, J.M.; Gudas, L.J. RARg is essential for retinoic acid induced chromatin remodelling and transcriptional activation in embryonic stem cells. J. Cell Sci. 2012, 126, 999–1008. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chatagnon, A.; Veber, P.; Morin, V.; Bedo, J.; Triqueneaux, G.; Semon, M.; Laudet, V.; d’Alche-Buc, F.; Benoit, G. RAR/RXR binding dynamics distinguish pluripotency from differentiation associated cis-regulatory elements. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, 4833–4854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koyama, E.; Golden, E.B.; Kirsch, T.; Adams, S.L.; Chandraratna, R.A.; Michaille, J.J.; Pacifici, M. Retinoid signalling is required for chondrocyte maturation and endochondral bone formation. Dev. Biol. 1999, 208, 375–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, J.A.; Kondo, N.; Okabe, T.; Takeshita, N.; Pilchak, D.M.; Koyama, E.; Ochiai, T.; Jensen, D.; Chu, M.L.; Kane, M.A.; et al. Retinoic acid receptors are required for skeletal growth, matrix homeostasis and growth plate function in postnatal mouse. Dev. Biol. 2009, 328, 315–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasuhara, R.; Yuasa, T.; Willams, J.A.; Byers, S.W.; Shah, S.; Pacitici, M.; Iwamoto, M.; Enomoto-Iwamoto, M. Wnt/b-catenin and retinoic acid receptor signaling pathways interact to regulate chondrocyte function and matrix turnover. J. Bio.l Chem. 2010, 285, 317–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

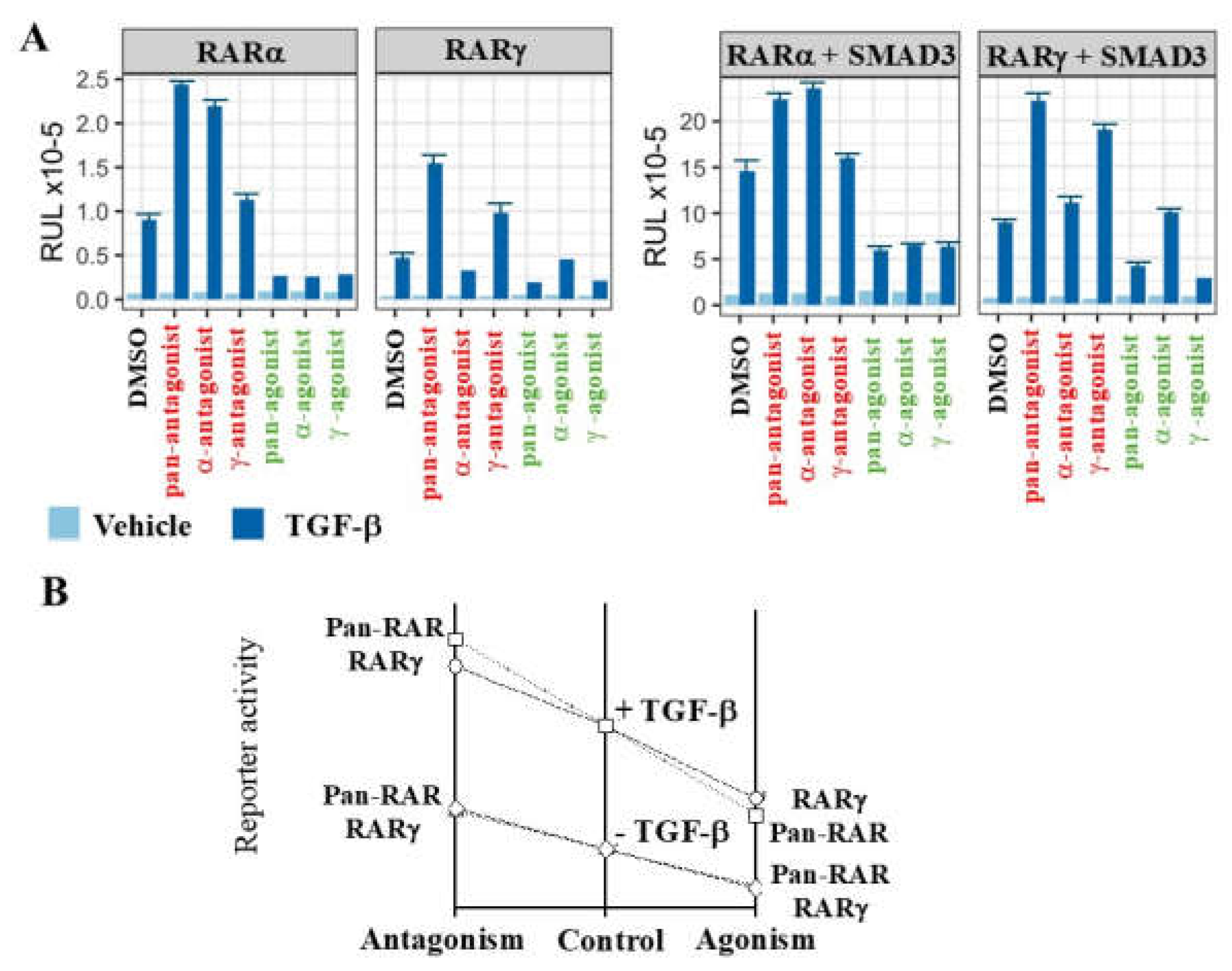

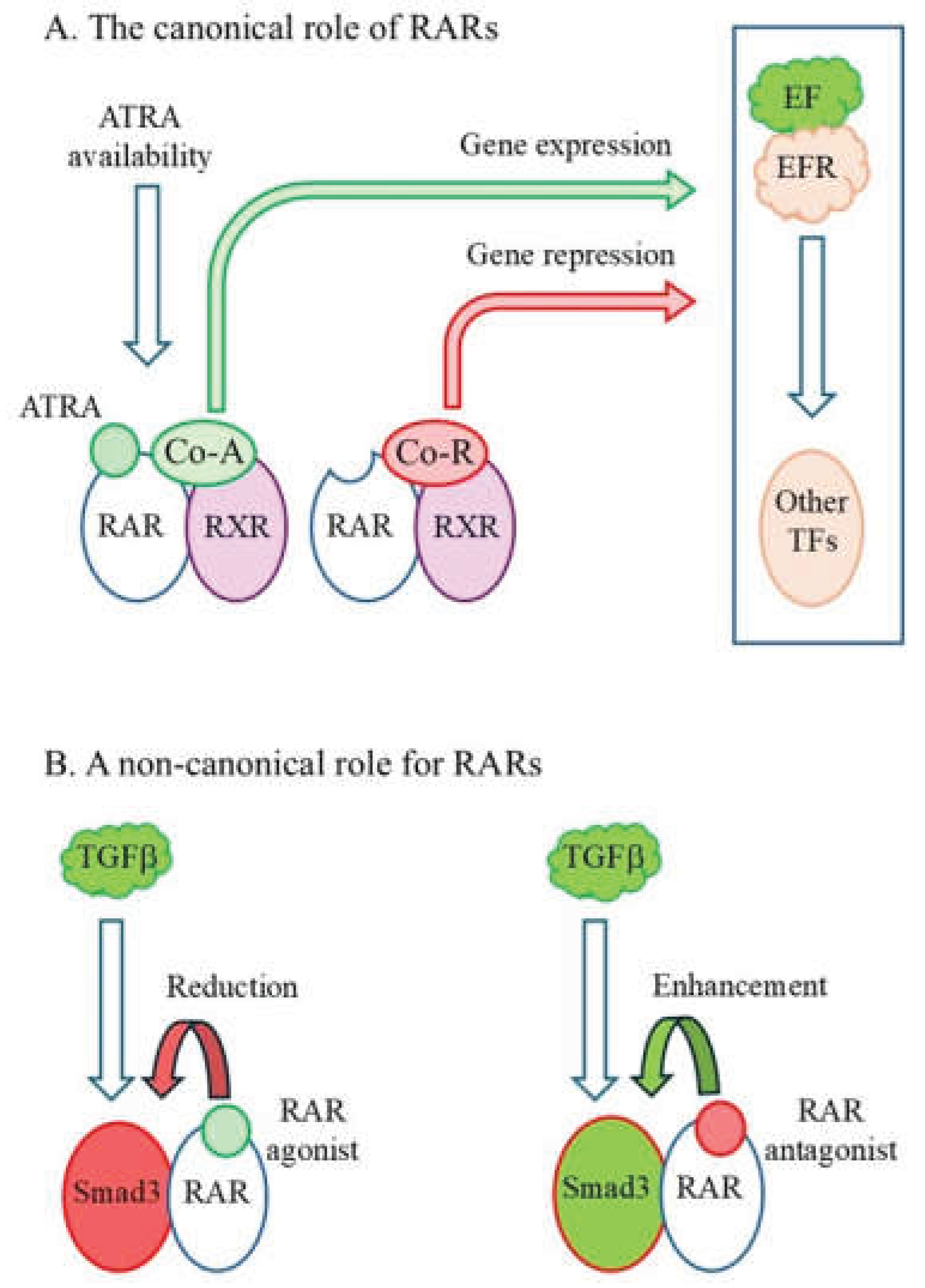

- Pendaries, V.; Verrecchia, F.; Michel, S.; Mauviel, A. Retinoic acid receptors interfere with TGF-b/Smad signaling pathway in a ligand-specific manner. Oncogene 2003, 22, 8212–8220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, W.; Zhang, C.; Cheng, H.; Wu, Y-L.; Liu, J.; Chen, Z.; Huang, J-g.; Erickson, R.E.; Chen, L.; Zhang, H.; et al. Targeting to the non-genomic activity of retinoic acid receptor-gamma by acacetin in hepatocellular carcinoma. Scientific Reports 2017, 7, 348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, E.D.; Beninghof, E.G.; Koenig, R.J. Dimerization interfaces of thyroid hormone, retinoic acid, vitamin D, and retinoid X receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 1993, 268, 11534–11541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glass, C.K.; Lipkin, S.M.; Devary, O.V.; Rosenfeld, M.G. Positive and negative regulation of gene transcription by a retinoic acid-thyroid hormone receptor heterodimer. Cell 1989, 59, 697–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yen, P.M.; Sugawara, A.; Chin, W.W. Triiodothyronine (T3) differentially affects T3-receptor/retinoic acid receptor and T3-receptor/retinoid X receptor heterodimer binding to DNA. J. Biol. Chem. 1992, 267, 23248–23252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrader, M.; Carlberg, C. Thyroid hormone and retinoic acid receptors form heterodimers with retinoid X receptors on direct repeats, palindromes, and inverted palindromes. DNA Cell Biol. 1994, 13, 333–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Privalsky, M.L. Heterodimers of retinoic acid receptors and thyroid hormone receptors display unique combinatorial regulatory properties. Mol. Endocrinol. 2005, 19, 863–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, C.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, F.; Xu, J.; Ren, Z.; Goday-Parejo, C.; Xiao, X.; Liu, W.; Zhou, Z.; Chen, G. Thyroid hormone enhances stem cell maintenance and promotes lineage-specific differentiation in human embryonic stem cells. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2002, 13, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.Y.; Chen, Z. Acute promyelocytic leukemia: from highly fatal to highly curable. Blood 2008, 111, 2505–2515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watts, J.M.; Perez, A.; Pereira, L.; Fan, Y-S.; Brown, G.; Vega, F.; Petrie, K.; Swords, R.T.; Zelent, A. A case of AML characterized by a novel t(4;15)(q31;q22) translocation that confers a growth-stimulatory response to retinoid-based therapy. Int. J, Mol. Sci 2017, 18, 1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

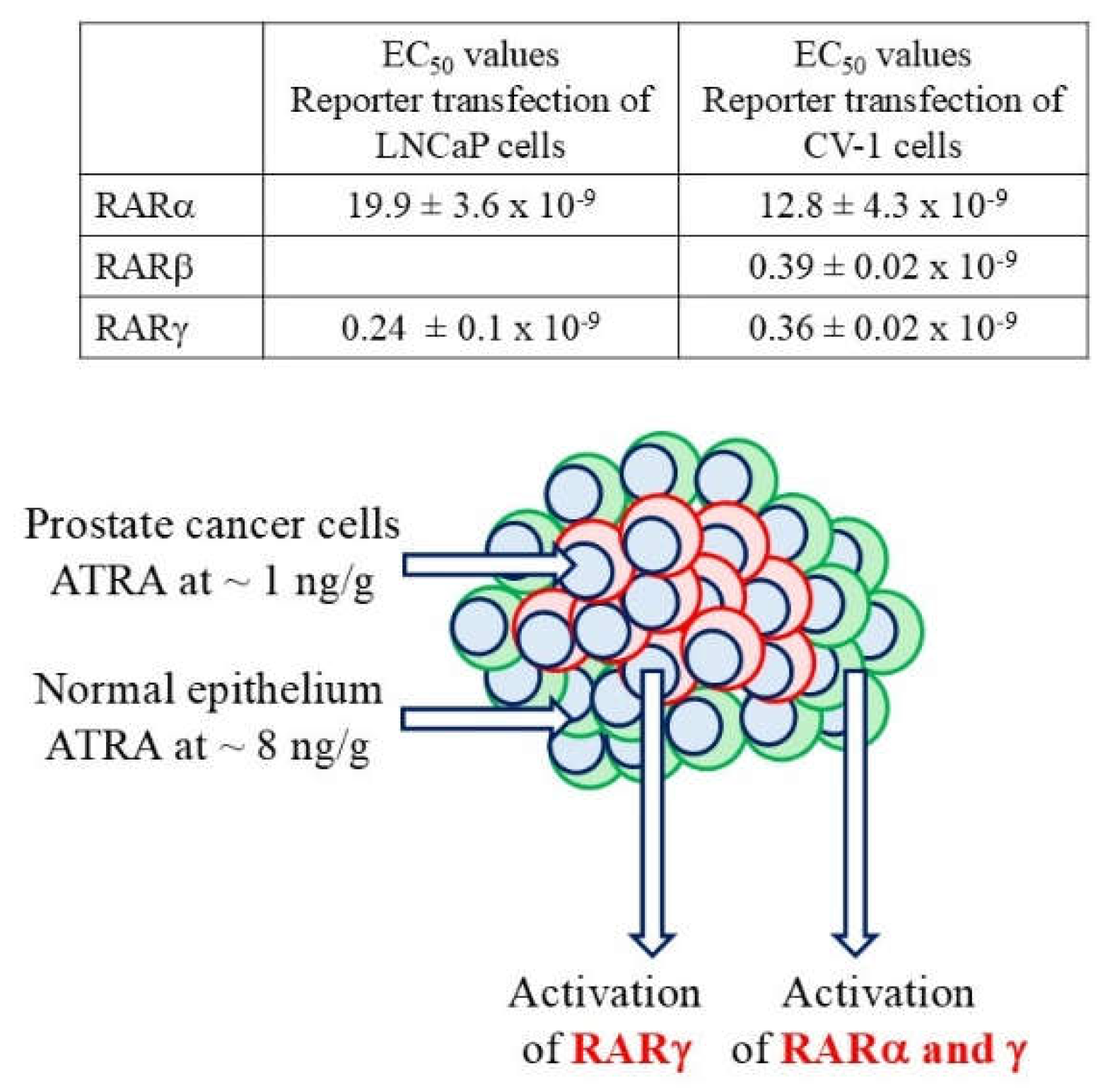

- Petrie, K.; Urban-Wojciuk, Z.; Sbirkov, Y.; Graham, A.; Hamann, A.; Brown, G. Retinoic acid receptor g is a therapeutically targetable drive of growth and survival in prostate cancer. Cancer Rep. (Hoboken) 2020, 3, e1284. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Su, Y-C.; Wu, S-Y.; Hsu, K-F.; jiang, S-S.; Kuo, P-C.; Shiao, A-L.; Wu, C-L.; Wang, Y-K.; Hsiao, J-R. Oncogenic RARg isoforms promote head and neck cancer proliferation through vinexin-b-mediated cell cycle acceleration and autocrine activation of EGFR signal. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2025, 21, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, T-D.; Wu, H.; Zhang, H-P.; Lu, N.; Ye, P.; Yu, F-H.; Zhou, H.; Li, W-G; Cao, X.; Lin, Y-Y.; et al. Oncogenic potential of retinoic acid receptor-g in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Res 2010, 70, 2285–2295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G-L.; Luo, Q.; Rui, G.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, Q-Y.; Chen, Q-X.; Shen, D-Y. Oncogenic activity of the retinoic acid receptor g is exhibited through activation of the Akt/NF-kB and Wnt/b-catenin pathways in cholangiocarcinoma. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2013, 33, 3416–3425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G-L.; Song, W.; Zhou, P.; Fu, Q-R.; Lin, C-L.; Chen, Q-X.; Shen, D-Y. Oncogenic retinoic acid receptor g knockdown reverses multidrug resistance of human colorectal cancer via Wnt/b-catenin pathway. Cell Cycle 2017, 16, 685–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cizmarikova, M.; Michalkova, R.; Franko, O.; Leskova, B.; Homolya, A.D.; Gabzdilova, J.; Takac, P., Jr. Targeting multidrug resistance in cancer: Impact of retinoids, rexinoids, and carotinoids on ABC transporters. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiu, L.; Zhao, Y.; Li, N.; Zeng, J.; Liu, J.; Fu, Y.; Gao, Q.; Wu, L. High expression of RARG accelerates ovarian cancer progression by regulating cell proliferation. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 1063031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, K.; Dou, X.; Zhang, N.; Wen, B.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, Q.; Xu, S.; Zhou, J.; Liu, T. Retinoic acid receptor gamma is required for proliferation of pancreatic cancer cells. Cell Biol. Int. 2023, 47, 144–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamakowa, K.; Koyangi-Aoi, M.; Machinaga, A.; Kakiuchi, N.; Hirano, T.; Kodama, Y.; Aoi, T. Blockage of retinoic acid signalling via RARgamma suppressed the proliferation of pancreatic cancer cells by arresting the cell cycle progression in G1-S phase. Cancer Cell Int. 2023, 23, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, K.; Dou, W.; Zhang, N.; Wen, B.; Zhong, M.; Zhang, Q.; Xu, s.; Zhou, J.; Liu, J. Retinoic receptor gamma is required for proliferation of pancreatic cancer cells. Cell Biol. Int. 2023, 47, 144–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, F.; Joyce, A.; Fromowitz, F.; Wang, S.; Watson, J.; Watson, R.; Irwin, R.J.; Huang, H.F.S. Immunological localization of the retinoic acid receptors in human prostate. J. Androl. 2002, 23, 830–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.F.; Goyette, O.; Lohnes, D. RARg acts as a tumor suppressor in mouse keratinocytes. Oncogene 2004, 23, 5350–5359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kadgamuwa, C.; Choksi, S.; Xu, Q.; Cataissan, C.; Greenbaum, S.S.; Yuspa, S.H.; Liu, Z-G. Retinoic acid receptor-g in DNA damage induced necroptosis. iScience 2019, 17, 74–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoxie, H.R.; Tang, X-H.; Gudas, L.J. Multiple modes of transcription regulation by the nuclear hormone receptor RARg in human squamous cell carcinoma. 2025, Nov20, 110905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, F.D.; Matushansky, I. Solid tumor differentiation therapy – is it possible? Oncotarget 2012, 3, 559–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, M.; Ossowski, L.; Ferrari, A.C. Activation of Rb and decline in androgen receptor protein precede retinoic acid induced apoptosis in androgen-dependent LNCaP cells and their androgen-independent derivative. J. Cell. Physiol. 1999, 179, 336–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammond, L.A.; Van Krinks, C.H.; Durham, J.; Tomkins, S.E.; Burnett, R.D.; Jones, E.L.; Chandraratna, R.A.S.; Brown, G. Antagonists of retinoic acid receptors (RARs) are potent growth inhibitors of prostate carcinoma cells. Br. J. Cancer 2001, 85, 453–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, X-P.; Fanjul, A.; Picard, N.; Shroot, B.; Pfahl, M. A selective retinoid with high activity against an androgen-resistant prostate cancer cell type. Int. J. Cancer 1999, 80, 272–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasquali, D.; Thaller, C.; Eichele, G. Abnormal level of retinoic acid in prostate cancer tissues. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1996, 81, 2186–2191. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bleul, T.; Ruhl, R.; Bulashevska, S.; Karakhanova, S.; Werner, J.; Bazhin, A.V. Reduced retinoids and retinoid receptors’ expression in pancreatic cancer: A link to patient survival. Mol. Carcinog. 2015, 54, 870–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, S.J.; Cvetkovic, D.; Hamilton, T.C. Vitamin A metabolism is impaired in human ovarian cancer. Gynecol. Oncol. 2009, 112, 637–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.-A.; Kwan, H.; Cho, H.; Chung, J.-Y.; Hewitt, S.M.; Kim, J.-H. ALDH1A2 is a candidate tumor suppressor gene in ovarian cancer. Cancer 2019, 11, 1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kroptova, E.S.; Zinov’eva, O.L.; Zyranova, A.F.; Chinzonov, E.L.; Afanas’ev, S.G.; Cherdyntseva, N.V.; Berensten, S.F.; lu Oparina, N.; Mashkeva, T.D. Expression of genes involved in retinoic acid biosynthesis in human gastric cancer. Mol. Biol. 2013, 47, 317–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuznetsova, E.S.; Zinovieva, O.L.; Oparina, N.Y.; Prokofjeva, M.M.; Spirin, P.V.; Favorskaya, I.A.; Zborovskaya, I.B.; Lisitsyn, N.A.; Prassolov, V.S.; Mashkova, T.D. Abnormal expression of genes that regulate retinoid metabolism in non-small-cell lung cancer. Mol. Biol. 2016, 50, 220–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidensaal, K.; Nollert, A.; Fiege, A.H.; Muller, M.; Fleming, T.; Gunkel, N.; Zaoui, K.; Grabe, N.; Weichert, N.; Weber, K.-J.; et al. Impaired aldehyde dehydrogenase subfamily member 2A-dependent retinoic acid signaling is related with a mesenchymal-like phenotype and an unfavourable prognosis of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Mol. Cancer 2015, 14, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudryavtseva, A.V.; Nyushko, K.M.; Zaretsky, A.R.; Shagin, D.A.; Kaprin, A.D.; Alekseev, B.Y.; Snezhkina, A.V. Upregulation of Rarb, Rarg, and Rorc Genes in Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma. Biomed. Pharmacol. J. 2016, 9, 967–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Nanys, D.M.; Ruiz, A.; Rando, R.R.; Bok, L.J. Reduced levels of retinyl esters and vitamin A in human renal cancers. Cancer Res. 2001, 61, 2774–2781. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, G.; Petrie, K. The RARg oncogene: An Achilles heel for some cancers. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 3632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawada, T; Kamei, Y; Fujita, A; Hida, Y.; Takahashi, N.; Sugimoto, E.; Fushiki, T. Carotenoids and retinoids as suppressors on adipocyte differentiation via nuclear receptors. Biofactors 2000, 13, 103–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berry, D.C.; DeSantis, D.; Soltanian, H.; Croniger, C.M.; Noy, N. Retinoic acid upregulates preadipocyte genes to block adipogenesis and suppress diet-induced obesity. Diabetes 2012, 61, 112–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhau, H.E.; He, H.; Wang, C.Y.; Zayafoon, M.; Morrissey, C.; Vesselle, R.L.; Marshall, F.F.; Chung, L.W.K.; Wang, T. Human prostate cancer harbors the stem cell properties of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells. Clin. Cancer Res. 2011, 17, 2159–2169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamakowa, K.; Koyangi-Aoi, M.; Machinaga, A.; Kakiuchi, N.; Hirano, T.; Kodama, Y.; Aoi, T. Blockage of retinoic acid signalling via RARgamma suppressed the proliferation of pancreatic cancer cells by arresting the cell cycle progression in G1-S phase. Cancer Cell Int. 2023, 23, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyan, C.H.; Baur, K.; Hackl, H.; Scherka, A.; Koller, E.; Hladik, A.; Stoiber, D.; Zuber, J.; Staber, P.B.; Hoelbl-Kovacic, A. All trans retinoic acid enhances, and a pan-RAR antagonist counteracts, the stem cell promoting activity of EV11 in acute myeloid leukemia. Cell Death Dis. 2019, 10, 944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chefetz, I.; Grimley, E.; Yang, K.; Hong, L.; Vinogradova, E.V.; Suciu, R.; Kovalenko, I.; Karnak, D.; Morgan, C.A.; Chtcherbinine, M.; et al. A pan-ALDH1A inhibitor induces necroptosis in ovarian cancer stem-like cells. Cell Rep. 2019, 26, 3061–3075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebollido-Rios, R.; Venton, G.; Sancchez-Redondo, S.; Felip, C.I.; Fournet, G.; Gonzalez, E.; Romero-Fernandez, W.; Esuaela, D.O.B.; Di Stefano, B.; Penarroche-Diaz, R.; et al. Dual disruption of aldehyde dehydrogenases 1 and 3 promotes functional changes in the glutathione redox system and enhances chemosensitivity in non-small cell lung cancer. Oncogene 2020, 39, 2756–2771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mori, Y.; Yamawaki, K.; Ishiguro, T.; Yoshihara, K.; Ueda, H.; Sato, A.; Ohata, H.; Yoshida, Y.; Minamino, T.; Okamoto, K.; et al. ALDH-dependent glycolytic activation mediates stemness and paclitaxel resistance in patient-derived spheroid models of uterine endometrial cancer. Stem Cell Rep. 2019, 13, 730–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Song, H.; Jiang, L.; Qiao, Y.; Yang, D.; Wang, D.; Li, J. Silybin prevents prostate cancer by inhibited the ALDH1A1 expression in the retinol metabolism pathway. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 8, 574394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.-H.; Chiu, W.-T.; Young, M.-Y.; Change, T.-H.; Huang, Y.-F.; Chou, C.-Y. Solanum incanum extract downregulates aldehyde dehydrogenase 1-mediated stemness and inhibits tumor formation in ovarian cancer cells. J. Cancer 2015, 6, 1011–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khillan, J.S. Vitamin A/retinol and the maintenance of pluripotency of stem cells. Nutrients 2014, 6, 1209–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Khillan, J.S. A novel signaling by vitamin a/retinol promotes self-renewal of mouse embryonic stem cells by activating PI3K/Akt signaling pathway via insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor. Stem Cells 2010, 28, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simandi, Z.; Balint, B.L.; Poliski, S.; Ruhl, R.; Nagy, L. Activation of retinoic acid receptor signalling coordinates lineage commitment of spontaneously differentiating mouse embryonic stem cells in embryoid bodies. FEBS Lett. 2010, 584, 3123–3130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duester, G. Retinoic acid synthesis and signalling during early organogenesis. 2008, 19(134), 921–931. [Google Scholar]

- Mendoz-Parra, M.A.; Walia, M.; Sankar, M.; Gronemeyer, H. Dissecting the retinoid-induced differentiation of F9 embryonal stem cells by integrative genomics. Molecular Systems Biology 2011, 7, 538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, y-H.; Zhou, H.; Kim, J-H.; Yan, T-d.; Lee, K-H.; Wu, H.; Lin, F.; Lu, N.; Liu, J.; Zeng, J-z.; et al. A unique cytoplasmic localization of retinoic acid receptor-g and its regulations. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 18503–18514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grishechkin, A.; Mukherjee, A.; Karin, D. Mathematical framework for hierarchical cell identity controlling collective enhancer dynamics. PRX LIFE 2025, 3, 043007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, S.S.W.; Wang, X.; Roberts, S.S.; Griffey, S.M.; Reczek, P.R.; Wolgemuth, D.J. Oral administration of a retinoic receptor antagonist reversibly inhibits spermatogenesis in mice. Endocrinology 2011, 152, 2492–2502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schulze, G.E.; Clay, R.J.; Mezza, L.E.; Bregman, C.L.; Buroker, R.A.; Frantz, J.D. BMS-189453, a novel retinoid receptor antagonist, is a potent testicular toxin. Toxicol. Sci. 2001, 59, 297–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venton, G.; Perez-Alea, M.; Baier, C.; Pournet, G.; Quash, G.; Labiad, Y.; Martin, G.; Sanderson, F.; Poulin, P.; Suchon, P.; et al. Aldehyde dehydrogenases inhibition eradicated leukaemia stem cells while sparing normal progenitors. Blood Cancer J. 2016, 6, e469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Cells | Pan-RAR antagonist (AGN194310) |

RARg antagonist (AGN205728) |

ATRA |

| For CSC-like colony forming cells (IC50 values, relative to control) | |||

| LNCaP | 1.6 ± 0.5 x 10-8 M | 4.2 ± 0.1 x 10-8 M | 34.4 ± 3.2 x 10-8 M |

| PC3 | 1.8 ± 0.6 x 10-8 M | 4.7 ± 0.2 x 10-8 M | 41.9 ± 12 x 10-8 M |

| DU145 | 3.4 ± 0.7 x 10-8 M | 40.2 ± 7.4 x 10-8 M | |

| For cell line cultures (IC50 values, viable cells) | |||

| LNCaP | 3.9 ± 0.2 x 10-7 M | 4.5 ± 0.2 x 10-7 M | > 2 x 10-6 M |

| PC3 | 3.5 ± 0.4 x 10-7 M | 4.7 ± 0.2 x 10-7 M | >2 x 10-6 M |

| DU145 | 5.0 ± 0.4 x 10-7 M | 5.6 ± 0.2 x 10-7 M | >2 x 10-6 M |

| Non-malignant RWPE-1 | 23 ± 4.0 x 10-7 M | ||

| For primary cell cultures (IC50 values, viable cells) | |||

| Prostate cancer cells | 4.6 ± 1.9 x 10-7 M* | 3.0 x 10-7 M | > 2 x 10-6 M |

| Non-malignant epithelium | 9.5 ± 0.8 x 10-7 M | 7.2 ± 0.5 x 10-7 M | |

| Normal fibroblasts | 8.0 ± 0.7 x 10-7 M | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).