Introduction

Glioblastoma (GBM) is the most common and aggressive primary malignant brain tumor in adults, associated with a dismal prognosis despite multimodal therapy comprising surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy [

1,

2]. The inherent challenges in treating GBM stem from its aggressive invasiveness, profound intra- and inter-tumoral heterogeneity, and remarkable capacity for therapy resistance leading to near-universal recurrence [

3,

4]. A subpopulation of cells within the tumor, often exhibiting stem-like properties (cancer stem-like cells or CSCs), is increasingly recognized as a central driver of these malignant characteristics. These cells possess self-renewal capabilities, potential for multi-lineage differentiation, and are preferentially resistant to conventional therapies, enabling them to initiate tumor formation and repopulate the tumor mass after treatment [

5,

6,

7]. Key transcription factors and cytoskeletal proteins, such as SOX2 (SRY-Box Transcription Factor 2) and Nestin (NES), are associated with this stem-like state and are often used as markers [

8,

9]. Targeting pathways active in these subpopulations represents a critical unmet need for improving GBM patient outcomes.

Temozolomide (TMZ), an alkylating agent, is the cornerstone of current GBM chemotherapy [

10]. TMZ exerts its cytotoxic effect primarily by methylating DNA bases, particularly at the O⁶ position of guanine (O⁶-MeG). This lesion, if unrepaired, leads to DNA double-strand breaks during replication and triggers cell cycle arrest and apoptosis [

11]. However, the efficacy of TMZ is frequently limited by intrinsic and acquired resistance mechanisms. The most significant factor mediating TMZ resistance is the DNA repair enzyme O⁶-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase (MGMT) [

12,

13]. MGMT directly removes the methyl group from O⁶-MeG, thereby reversing the cytotoxic lesion and conferring resistance. High MGMT expression levels in tumor cells strongly correlate with poor response to TMZ and reduced patient survival [

14]. Epigenetic silencing of the MGMT promoter via methylation is a predictive biomarker for TMZ sensitivity, but many GBMs exhibit high MGMT expression due to an unmethylated promoter, posing a major clinical challenge [

15,

16]. Strategies to overcome MGMT-mediated resistance are urgently needed.

Differentiation therapy, which aims to force cancer cells out of their highly proliferative and resistant stem-like state into a more mature, less malignant phenotype, offers a compelling alternative or adjunct therapeutic strategy [

17]. By inducing differentiation, it is hypothesized that CSCs might lose their tumorigenic potential and become more susceptible to conventional therapies. All-trans retinoic acid (ATRA), a biologically active metabolite of vitamin A, is a well-established differentiation agent, most notably used successfully in the treatment of acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL) [

18]. ATRA functions primarily by binding to nuclear retinoic acid receptors (RARs), which act as ligand-dependent transcription factors regulating genes involved in cell growth, differentiation, and apoptosis [

19]. Preclinical studies have suggested potential roles for ATRA in modulating glioma cell behavior, including inducing differentiation, inhibiting proliferation, and reducing invasiveness [

20,

21,

22], although results can be variable. Some studies suggest ATRA might sensitize glioma cells to chemotherapy or radiation [

23,

24], but the underlying molecular mechanisms linking differentiation to specific resistance factors like MGMT remain incompletely understood, especially in models enriched for stem-like properties.

Specifically, the connection between ATRA-induced differentiation, the downregulation of stemness-associated markers, and the concurrent modulation of MGMT in established GBM models cultured under stem-enriching conditions has not been fully explored. We hypothesized that ATRA treatment would reduce the expression of stemness markers (SOX2, NES) and decrease the transcript levels of MGMT in established human GBM cell lines. To test this hypothesis, we utilized two widely studied human GBM cell lines, U87-MG and A172, cultured under neurosphere conditions designed to promote stem-like characteristics. Using quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR), we assessed the impact of ATRA treatment on the mRNA expression levels of SOX2, NES, and MGMT. Our findings provide molecular evidence linking ATRA treatment to the downregulation of both stemness markers and the pivotal chemoresistance gene MGMT in these GBM cell line models.

Materials and Methods

Cell Lines and Culture Conditions

Established human glioblastoma cell lines U87-MG (ATCC® HTB-14™) and A172 (ATCC® CRL-1620™) were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection. To enrich for potential stem-like subpopulations and facilitate comparison with stem cell studies, cells were cultured as non-adherent neurospheres in serum-free NeuroCult™ NS-A Proliferation Medium supplemented with NeuroCult™ Proliferation Supplement (STEMCELL Technologies), 20 ng/mL recombinant human epidermal growth factor (EGF; PeproTech), 10 ng/mL recombinant human basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF; PeproTech), and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Cells were maintained in uncoated T75 flasks (Corning) at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO₂. Neurospheres were passaged every 5-7 days by mechanical dissociation followed by enzymatic dissociation using Accutase (STEMCELL Technologies) for 5-7 minutes at 37°C, followed by quenching with medium, centrifugation (300 x g, 5 min), and resuspension in fresh medium. Cell lines were routinely tested for mycoplasma contamination using a PCR-based detection kit (MycoAlert™, Lonza).

All-Trans Retinoic Acid (ATRA) Treatment

All-trans retinoic acid (Sigma-Aldrich) was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO; Sigma-Aldrich) to create a 10 mM stock solution, aliquoted, and stored protected from light at -80°C. For experiments, cells were dissociated into single cells as described above and seeded at a density of 1 x 10⁵ cells/mL in 6-well plates (Corning) containing 2 mL of complete NeuroCult medium per well. Cells were allowed to recover for 24 hours before treatment. ATRA stock solution was diluted in culture medium to achieve a final concentration of 1 µM. Vehicle control wells received an equivalent volume of DMSO (final concentration 0.01%). Treatments were performed in biological triplicate for each cell line and condition. Cells were incubated with ATRA or vehicle for 5 days at 37°C and 5% CO₂, with fresh medium containing the respective treatment added after 2.5 days. All procedures involving ATRA were performed under subdued light conditions. The concentration (1 µM) and duration (5 days) were selected based on established literature demonstrating ATRA-induced effects in glioma cells and were confirmed to exhibit minimal cytotoxicity under these culture conditions in preliminary viability assays (e.g., using Trypan Blue exclusion or a standard MTS/WST assay).

RNA Isolation and Quality Control

After the 5-day treatment period, neurospheres were collected by centrifugation (300 x g, 5 min), washed once with ice-cold Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS; Thermo Fisher Scientific), and total RNA was isolated using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer's protocol, including an on-column DNase I digestion step (RNase-Free DNase Set, Qiagen) to eliminate genomic DNA contamination. RNA concentration and purity were assessed using a NanoDrop™ 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Samples with A260/280 ratios between 1.9 and 2.1 and A260/230 ratios above 1.8 were considered high quality and used for downstream applications. RNA integrity was confirmed for representative samples (e.g., via visualization of distinct 18S and 28S rRNA bands on an agarose gel).

cDNA Synthesis

First-strand complementary DNA (cDNA) was synthesized from 1 µg of total RNA using the High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems, Thermo Fisher Scientific) in a 20 µL reaction volume, according to the manufacturer's instructions. The reaction mixture included random primers and MultiScribe™ Reverse Transcriptase. Reactions were performed in a thermal cycler (Veriti™ 96-Well Thermal Cycler, Applied Biosystems, Thermo Fisher Scientific) with the following program: 25°C for 10 min, 37°C for 120 min, and 85°C for 5 min. Control reactions lacking reverse transcriptase (-RT controls) were prepared for representative samples to verify the absence of significant genomic DNA amplification during subsequent qPCR. Synthesized cDNA was diluted 1:5 with nuclease-free water (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and stored at -20°C until use.

Quantitative Real-Time PCR (qPCR)

qPCR was performed on a StepOnePlus™ Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems) using PowerUp™ SYBR™ Green Master Mix (Applied Biosystems). Primers for human SOX2, NES, MGMT, GAPDH, and ACTB were designed using Primer3Plus software (

http://www.primer3plus.com/) and validated for specificity and efficiency. Primer sequences, obtained from Integrated DNA Technologies, are listed in

Table 1. Primer efficiency for each pair was confirmed to be between 90-110% using a standard curve generated from serial dilutions of pooled cDNA. Specificity was confirmed by melt curve analysis following each qPCR run, which showed single, sharp peaks for each amplicon.

Each 10 µL qPCR reaction contained 5 µL of PowerUp™ SYBR™ Green Master Mix (2X), 0.5 µL of forward primer (10 µM stock), 0.5 µL of reverse primer (10 µM stock), 2 µL of diluted cDNA (corresponding to 20 ng of initial RNA input), and 2 µL of nuclease-free water. Reactions were performed in technical triplicate for each biological replicate. Standard thermal cycling conditions were used: UDG activation at 50°C for 2 min, initial denaturation at 95°C for 2 min, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 15 seconds and annealing/extension at 60°C for 1 minute. Melt curve analysis was performed immediately after amplification (95°C for 15 s, 60°C for 1 min, followed by a ramp to 95°C at 0.3°C/s). No-template controls (NTCs) containing water instead of cDNA were included in each run to monitor for contamination. The -RT controls were also run to ensure no significant amplification from potential genomic DNA contamination.

Data Analysis

Raw amplification data (Ct values) were exported from the StepOnePlus™ Software v2.3. Data processing and analysis were performed using Microsoft Excel and GraphPad Prism. The stability of housekeeping genes (GAPDH, ACTB) across treatment conditions was verified by confirming low variance in their Ct values across all samples. The geometric mean of the Ct values for GAPDH and ACTB was calculated for each sample and used for normalization.Relative gene expression was calculated using the comparative Ct (ΔΔCt) method [

25]:

Normalization: ΔCt = Ct_Target - Ct_Housekeeping_Mean.

Calibration: ΔΔCt = ΔCt_Sample - ΔCt_Vehicle_Average.

Relative Quantification (Fold Change): Fold Change = 2^-ΔΔCt. The average fold change for the vehicle control group was set to 1.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed on the ΔCt values using unpaired, two-tailed Student's t-tests to compare the ATRA-treated group versus the vehicle control group for each gene within each cell line. Biological replicates (n=3 per condition per cell line) were used for statistical comparisons. Results are presented as mean fold change ± Standard Error of the Mean (SEM). A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

RNA Quality and qPCR Validation

Total RNA isolated from U87-MG and A172 cells treated with either vehicle (DMSO) or 1 µM ATRA for 5 days was of high quality, with A260/280 ratios consistently between 1.95 and 2.05 and A260/230 ratios above 1.9. qPCR analysis demonstrated reliable amplification, with single peaks observed in melt curve analyses for all primer sets, confirming amplification specificity. No amplification was detected in NTC wells. Amplification in -RT controls was negligible (Ct > 35 or undetectable), confirming minimal genomic DNA contamination. The housekeeping genes GAPDH and ACTB exhibited stable expression across all experimental conditions, validating their use for normalization.

ATRA Treatment Downregulates Stemness Marker Expression in GBM Cell Lines

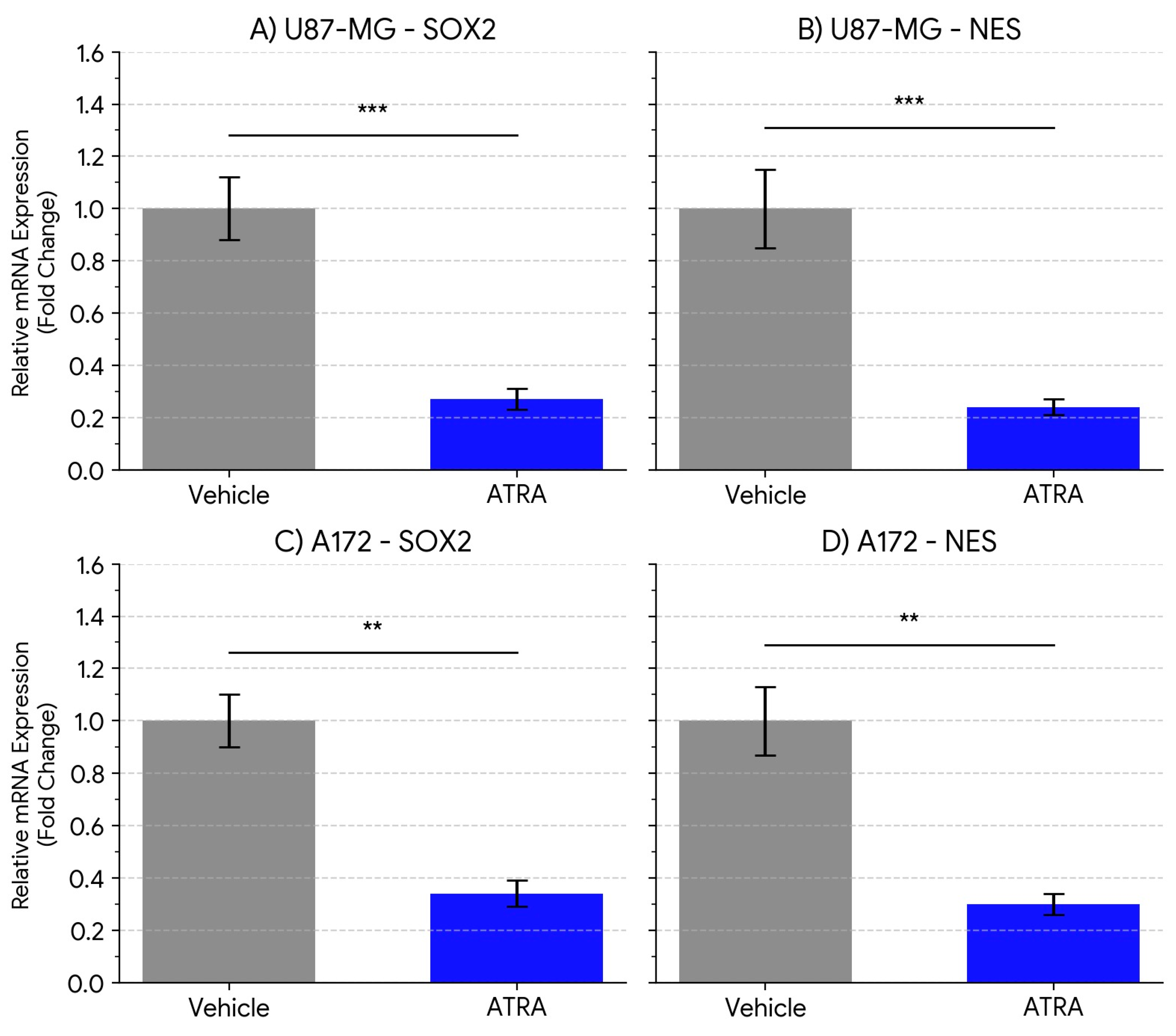

To determine the effect of ATRA on stemness-associated markers in GBM cells cultured under neurosphere conditions, we quantified the mRNA expression of the core stemness transcription factor SOX2 and the intermediate filament protein Nestin (NES).In the U87-MG cell line, treatment with 1 µM ATRA for 5 days resulted in a highly significant decrease in the expression of both markers compared to vehicle-treated controls (

Figure 1A, B). SOX2 mRNA levels were reduced by an average of 3.7-fold (Mean ± SEM: Vehicle 1.00 ± 0.12 vs. ATRA 0.27 ± 0.04; p = 0.0008). Similarly, NES mRNA expression was significantly downregulated by 4.1-fold following ATRA treatment (Vehicle 1.00 ± 0.15 vs. ATRA 0.24 ± 0.03; p = 0.0005).Similar effects were observed in the A172 cell line (

Figure 1C, D). ATRA treatment led to a significant reduction in SOX2 mRNA expression by 2.9-fold (Vehicle 1.00 ± 0.10 vs. ATRA 0.34 ± 0.05; p = 0.0041) and a significant decrease in NES mRNA expression by 3.3-fold (Vehicle 1.00 ± 0.13 vs. ATRA 0.30 ± 0.04; p = 0.0028).These results demonstrate that ATRA treatment effectively suppresses the expression of key genes associated with stem-like states in both established GBM lines when cultured under these conditions.

ATRA Treatment Downregulates MGMT Expression in GBM Cell Lines

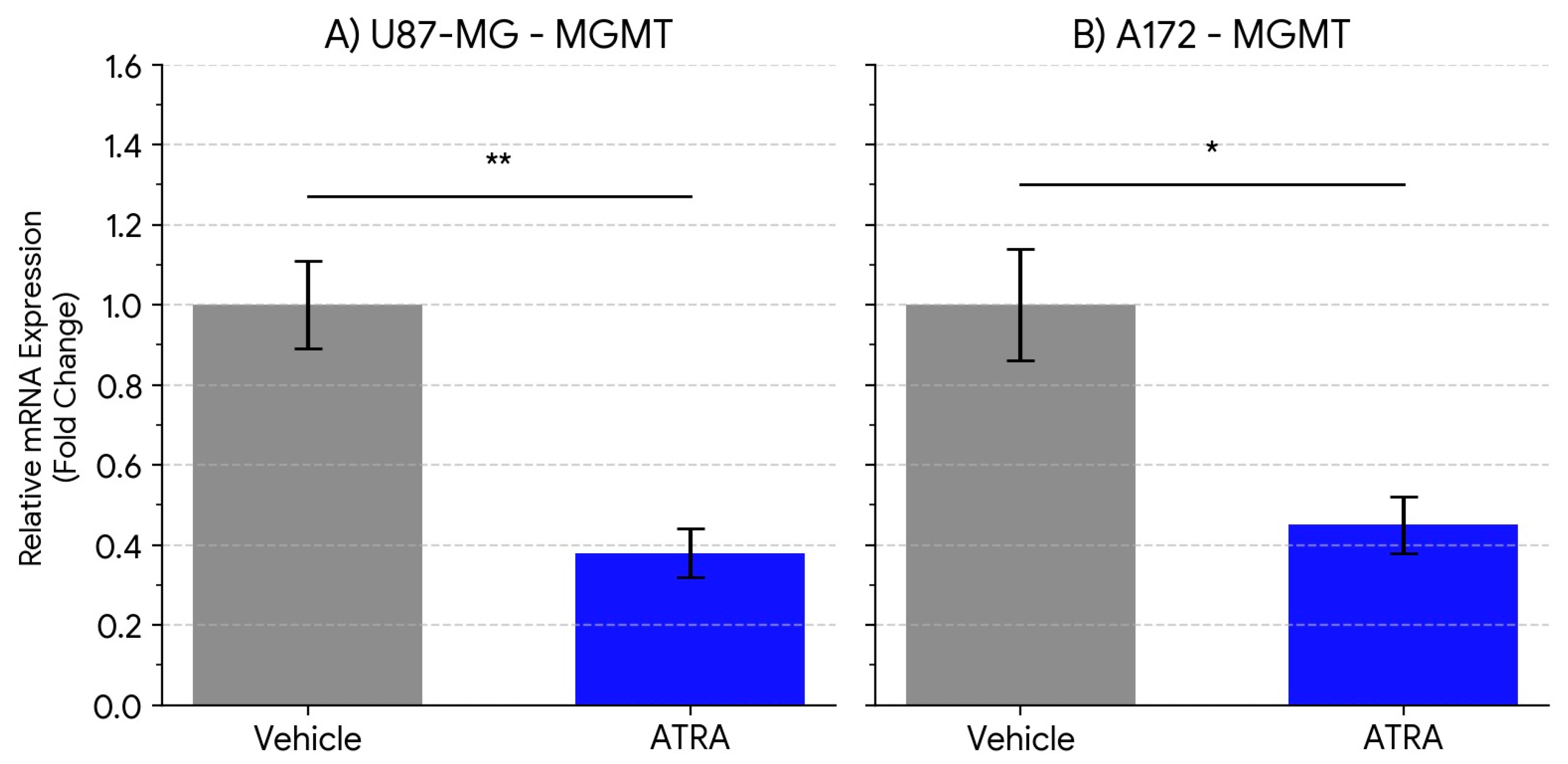

Given the critical role of MGMT in mediating TMZ resistance, we investigated whether ATRA treatment also modulates MGMT expression in these cell line models. We quantified MGMT mRNA levels in U87-MG and A172 cells following 5 days of vehicle or ATRA treatment.In U87-MG cells, ATRA treatment resulted in a statistically significant decrease in MGMT mRNA expression compared to the vehicle control group (

Figure 2A). The average MGMT transcript level was reduced by 2.6-fold (Vehicle 1.00 ± 0.11 vs. ATRA 0.38 ± 0.06; p = 0.0065).A similar significant downregulation of MGMT expression was observed in the A172 cell line following ATRA treatment (

Figure 2B). MGMT mRNA levels decreased by an average of 2.2-fold compared to vehicle controls (Vehicle 1.00 ± 0.14 vs. ATRA 0.45 ± 0.07; p = 0.0132).These findings indicate that ATRA treatment, concurrently with reducing stemness marker expression, also reduces the expression of the key TMZ resistance gene MGMT at the transcript level in both tested GBM cell lines under neurosphere culture conditions.

Summary of qPCR Results

The relative fold changes and statistical significance for all target genes in both cell lines are summarized in

Table 2.

Discussion

The resistance of glioblastoma to conventional therapies, particularly TMZ, represents a major obstacle in treating this disease. This study investigated the potential of ATRA-induced differentiation to concomitantly reduce stemness-associated properties and modulate the expression of the critical TMZ resistance gene, MGMT, in established human GBM cell lines cultured under neurosphere-promoting conditions. Our findings provide molecular evidence that treatment with 1 µM ATRA for 5 days significantly downregulates the mRNA expression of key stemness markers SOX2 and NES, as well as MGMT, in both U87-MG and A172 cell lines.

The observed downregulation of SOX2 and NES (approx. 3- to 4-fold reduction) suggests that ATRA treatment promotes a shift away from a stem-like transcriptional state in these models. SOX2 is a master regulator crucial for maintaining stem cell identity, including in glioma [

8,

26]. Nestin is associated with neural progenitors and a more aggressive phenotype in GBM [

9,

27]. The reduction in transcripts for both factors aligns with previous reports indicating that ATRA can induce morphological and molecular changes consistent with differentiation in glioma cell lines [

20,

22,

28]. Our quantitative data support these observations at the transcript level in established lines cultured under conditions designed to enrich for stem-like features, suggesting ATRA can modulate these specific pathways in these models.

Perhaps the most significant finding of this study is the concurrent downregulation of MGMT mRNA expression following ATRA treatment (approx. 2.2- to 2.6-fold reduction). MGMT is the primary determinant of TMZ resistance in GBM, and its expression level is inversely correlated with treatment response [

12,

13,

14]. While differentiation therapy has been proposed as a means to sensitize cancer cells, direct evidence linking ATRA to the modulation of MGMT expression in GBM models has been limited. Our results demonstrate a clear reduction in MGMT transcripts associated with ATRA treatment in U87-MG and A172 cells. This finding provides a potential molecular mechanism by which ATRA could modulate pathways associated with TMZ sensitivity, particularly relevant for tumors expressing significant levels of MGMT. This could be important as many GBM patients present with unmethylated MGMT promoters and derive limited benefit from TMZ [

15].

The mechanism by which ATRA downregulates MGMT expression warrants further investigation. ATRA signaling via RAR/RXR heterodimers could directly or indirectly repress MGMT transcription, possibly through interactions with regulatory elements near the MGMT gene or via modulation of other transcription factors [

19,

29,

30]. Alternatively, ATRA-induced differentiation might lead to broader epigenetic reprogramming, although significant changes in DNA methylation are less likely over this 5-day timeframe. Future studies involving chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) for RAR binding or analysis of histone modifications at the MGMT locus would be valuable.

We observed consistent effects of ATRA on SOX2, NES, and MGMT expression across two distinct established GBM lines, U87-MG and A172, strengthening the potential generalizability of these findings within these specific model systems. Although the magnitude of downregulation varied slightly, the overall trend was robustly significant in both.

It is crucial, however, to acknowledge the limitations of this study. Firstly, we used established cell lines (U87-MG, A172) cultured under specific neurosphere conditions. While useful and widely employed, these models may not fully recapitulate the biological heterogeneity and complex characteristics of patient-derived GSCs or primary GBM tumors in situ. Findings should be interpreted within the context of these specific cell line models. Secondly, our analysis focused solely on mRNA expression. Confirmation at the protein level for SOX2, NES, and particularly the functional enzyme MGMT (via Western blotting and MGMT activity assays) is an essential next step. Thirdly, these experiments were conducted in vitro. The tumor microenvironment in vivo could significantly influence cellular responses to ATRA. Future studies should aim to validate these findings in orthotopic xenograft models, assessing tumor growth, marker expression, and the combinatorial efficacy of ATRA and TMZ in vivo. Finally, investigating a broader range of concentrations, time points, and additional differentiation/stemness markers would provide a more comprehensive understanding.

Despite these limitations, our findings have significant implications. They provide a strong molecular rationale supporting the further exploration of ATRA as a modulator of key pathways in GBM models. By simultaneously reducing the expression of stemness-associated markers and the MGMT gene in established GBM cell lines, ATRA demonstrates potential for impacting both stem-like properties and TMZ resistance mechanisms. This warrants further preclinical investigation into ATRA, potentially in combination with TMZ, assessing functional outcomes such as effects on cell proliferation, clonogenicity, TMZ sensitivity (IC50 determination), and ultimately, in vivo efficacy in appropriate GBM models.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this study demonstrates that All-Trans Retinoic Acid (ATRA) treatment effectively downregulates the mRNA expression of the key stemness markers SOX2 and Nestin in the established glioblastoma cell lines U87-MG and A172 cultured under neurosphere conditions. Critically, we show that ATRA concurrently reduces the expression of the pivotal DNA repair and temozolomide resistance gene, MGMT, in these models. These findings provide direct molecular evidence linking ATRA treatment to the suppression of a major chemoresistance-associated factor alongside markers of a stem-like state in established GBM cell lines. This dual action highlights the potential utility of exploring ATRA in therapeutic strategies, particularly in combination approaches aimed at modulating TMZ resistance pathways and targeting aggressive cell populations in glioblastoma. Further preclinical and translational studies are warranted to fully evaluate the therapeutic potential of ATRA in relevant GBM models.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: J.T. ; Methodology: R.Y., J.T. ; Investigation: R.Y., J.T.; Formal Analysis & Modeling: R.Y., J.T.; Data Curation: R.Y., J.T.; Writing – Original Draft: J.T.; Writing – Review & Editing: R.Y., J.T.; Supervision: R.Y.; Project Administration: R.Y. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. The study was conducted using institutional resources available to the Principal Investigator (R.Y.).

Data Availability Statement

Due to institutional data management requirements, further datasets are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- Bao, S.; Wu, Q.; McLendon, R.E.; Hao, Y.; Shi, Q.; Hjelmeland, A.B.; Dewhirst, M.W.; Bigner, D.D.; Rich, J.N. Glioma stem cells promote radioresistance by preferential activation of the DNA damage response. Nature 2006, 444, 756–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campos, B.; Wan, F.; Farhadi, M.; Ernst, A.; Zeppernick, F.; Tagscherer, K.E.; Ahmadi, R.; Lohr, J.; Dictus, C.; Gdynia, G.; Combs, S.E.; Goidts, V.; Helmke, B.M.; Eckstein, V.; Roth, W.; Beckhove, P.; Lichter, P.; Unterberg, A.; Radlwimmer, B.; Herold-Mende, C. Differentiation therapy exerts antitumor effects on stem-like glioma cells. Clin. Cancer Res. 2010, 16, 2715–2728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powała, K.; Żołek, T.; Brown, G.; Kutner, A. Molecular interactions of selective agonists and antagonists with the retinoic acid receptor γ. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 6568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Begagić, E.; Pugonja, R.; Bečulić, H.; Čeliković, A.; Tandir Lihić, L.; Kadić Vukas, S.; Čejvan, L.; Skomorac, R.; Selimović, E.; Jaganjac, B.; et al. Molecular targeted therapies in glioblastoma multiforme: A systematic overview of global trends and findings. Brain Sci. 2023, 13, 1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlstrand, J.; Collins, V.P.; Lendahl, U. Expression of the class VI intermediate filament nestin in human central nervous system tumors. Cancer Res. 1992, 52, 5334–5341. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, J.; Amin, M.A.; Campian, J.L. Glioblastoma stem cells at the nexus of tumor heterogeneity, immune evasion, and therapeutic resistance. Cells 2025, 14, 562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangemi, R.M.; Griffero, F.; Marubbi, D.; Perera, M.; Capra, M.C.; Malatesta, P.; Ravetti, G.L.; Zona, G.L.; Daga, A.; Corte, G. SOX2 silencing in glioblastoma tumor-initiating cells causes stop of proliferation and loss of tumorigenicity. Stem Cells 2009, 27, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giese, A.; Bjerkvig, R.; Berens, M.E.; Westphal, M. Cost of migration: invasion of malignant gliomas and implications for treatment. J. Clin. Oncol. 2003, 21, 1624–1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glass, C.K.; Rosenfeld, M.G. The coregulator exchange in transcriptional functions of nuclear receptors. Genes Dev. 2000, 14, 121–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Karbhari, N.; Campian, J.L. Therapeutic targets in glioblastoma: Molecular pathways, emerging strategies, and future directions. Cells 2025, 14, 494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.E.; Ye, Y.C.; Chen, S.R.; Chai, J.R.; Lu, J.X.; Zhoa, L.; Gu, L.J.; Wang, Z.Y. Use of all-trans retinoic acid in the treatment of acute promyelocytic leukemia. Blood 1988, 72, 567–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaina, B.; Christmann, M.; Naumann, S.; Roos, W.P. MGMT: key node in the battle against genotoxicity, carcinogenicity and apoptosis induced by alkylating agents. DNA Repair 2007, 6, 1079–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lathia, J.D.; Mack, S.C.; Mulkearns-Hubert, E.E.; Valentim, C.L.; Rich, J.N. Cancer stem cells in glioblastoma. Genes Dev. 2015, 29, 1203–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lendahl, U.; Zimmerman, L.B.; McKay, R.D. CNS stem cells express a new class of intermediate filament protein. Cell 1990, 60, 585–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2^−ΔΔC_T method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coyle, K.M.; Dean, C.A.; Thomas, M.L.; Vidovic, D.; Giacomantonio, C.A.; Helyer, L.; Marcato, P. DNA methylation predicts the response of triple-negative breast cancers to All-Trans Retinoic Acid. Cancers 2018, 10, 397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, Q.T.; Patil, N.; Cioffi, G.; Waite, K.; Kruchko, C.; Barnholtz-Sloan, J.S. CBTRUS Statistical Report: Primary Brain and Other Central Nervous System Tumors Diagnosed in the United States in 2013–2017. Neuro Oncol. 2020, 22, iv1–iv96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pokorná, M.; Hudec, M.; Juříčková, I.; Vácha, M.; Polívková, Z.; Kútna, V.; Pala, J.; Ovsepian, S.V.; Černá, M.; O’Leary, V.B. All-trans retinoic acid fosters the multifarious U87MG cell line as a model of glioblastoma. Brain Sci. 2021, 11, 812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sell, S. Stem cell origin of cancer and differentiation therapy. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2004, 51, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, S.-M.; Trikannad, A.K.; Vellanki, S.; Hussain, M.; Malik, N.; Singh, S.R.; Jillella, A.; Obulareddy, S.; Malapati, S.; Bhatti, S.A.; et al. Stem cell origin of cancer: Clinical implications beyond immunotherapy for drug versus therapy development in cancer care. Cancers 2024, 16, 1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanskikh, D.; Kuziakova, O.; Baklanov, I.; Penkova, A.; Doroshenko, V.; Buriak, I.; Zhmenia, V.; Kumeiko, V. Cell-based glioma models for anticancer drug screening: From conventional adherent cell cultures to tumor-specific three-dimensional constructs. Cells 2024, 13, 2085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campos, B.; Wan, F.; Farhadi, M.; Ernst, A.; Zeppernick, F.; Tagscherer, K.E.; Ahmadi, R.; Lohr, J.; Dictus, C.; Gdynia, G.; Combs, S.E.; Goidts, V.; Helmke, B.M.; Eckstein, V.; Roth, W.; Beckhove, P.; Lichter, P.; Unterberg, A.; Radlwimmer, B.; Herold-Mende, C. Differentiation therapy exerts antitumor effects on stem-like glioma cells. Clin. Cancer Res. 2010, 16, 2715–2728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almeida Lima, K.; Osawa, I.Y.A.; Ramalho, M.C.C.; de Souza, I.; Guedes, C.B.; Souza Filho, C.H.D.d.; Monteiro, L.K.S.; Latancia, M.T.; Rocha, C.R.R. Temozolomide resistance in glioblastoma by NRF2: Protecting the evil. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kampers, L.F.C.; Metselaar, D.S.; Vinci, M.; Scirocchi, F.; Veldhuijzen van Zanten, S.; Eyrich, M.; Biassoni, V.; Hulleman, E.; Karremann, M.; Stücker, W.; et al. The complexity of malignant glioma treatment. Cancers 2025, 17, 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2^−ΔΔC_T method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangemi, R.M.; Griffero, F.; Marubbi, D.; Perera, M.; Capra, M.C.; Malatesta, P.; Ravetti, G.L.; Zona, G.L.; Daga, A.; Corte, G. SOX2 silencing in glioblastoma tumor-initiating cells causes stop of proliferation and loss of tumorigenicity. Stem Cells 2009, 27, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassn Mesrati, M.; Behrooz, A.B.; Y. Abuhamad, A.; Syahir, A. Understanding glioblastoma biomarkers: Knocking a mountain with a hammer. Cells 2020, 9, 1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerstmeier, J.; Possmayer, A.-L.; Bozkurt, S.; Hoffmann, M.E.; Dikic, I.; Herold-Mende, C.; Burger, M.C.; Münch, C.; Kögel, D.; Linder, B. Calcitriol promotes differentiation of glioma stem-like cells and increases their susceptibility to temozolomide. Cancers 2021, 13, 3577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuber, U.A.; Rieger, K.M.; Weller, M.; Kaina, B. Retinoic acid suppresses O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase expression in human embryonal carcinoma cells. Cancer Res. 1998, 58, 2054–2058. [Google Scholar]

- Jafari, H.; Hussain, S.; Campbell, M.J. Nuclear receptor coregulators in hormone-dependent cancers. Cancers 2022, 14, 2402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).