Submitted:

31 December 2025

Posted:

02 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Sample Size Calculation

2.3. Data Collection

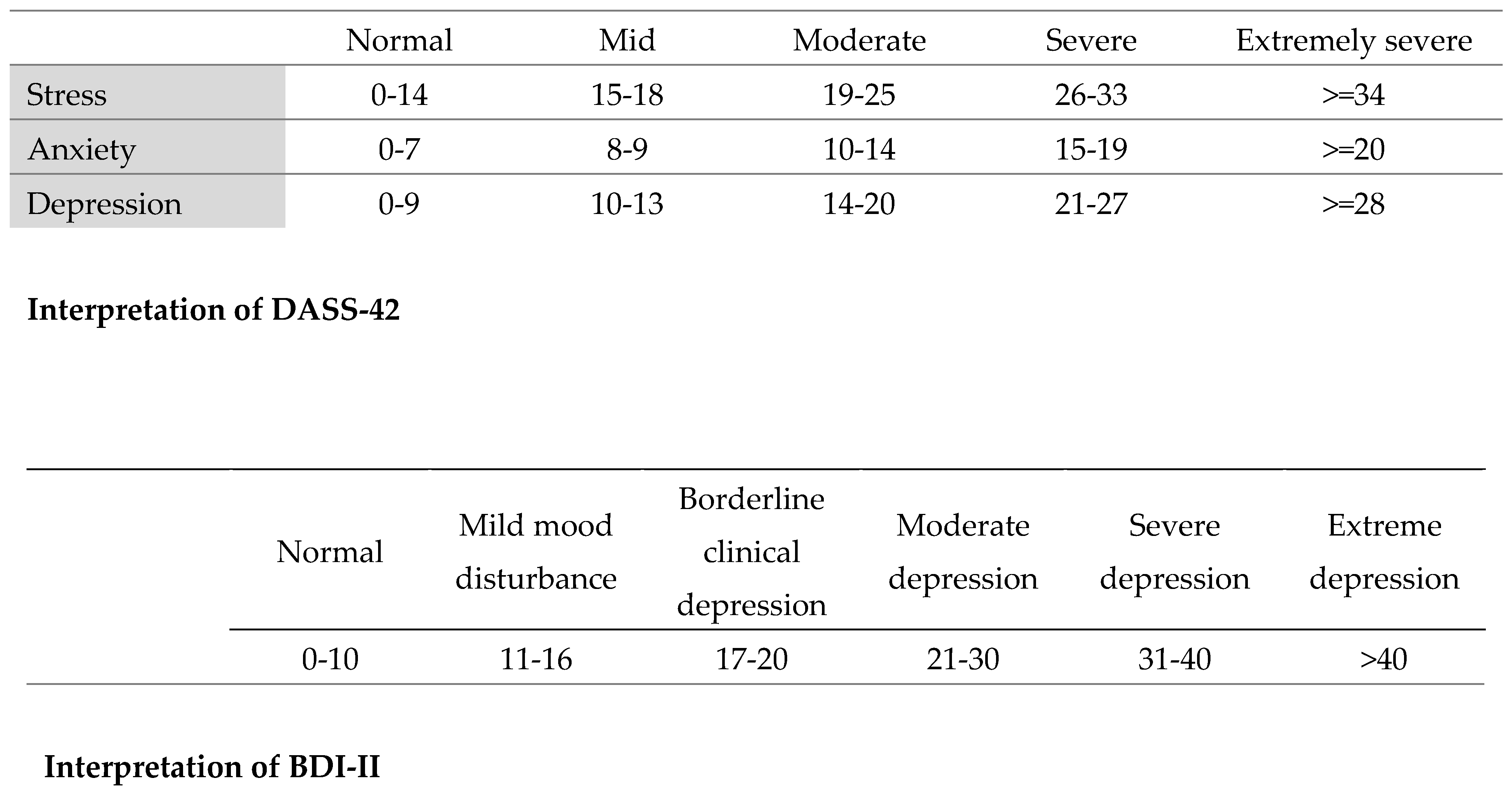

2.4. Questionnaire Interpretation

2.5. Data Entry and Statistical Analysis

3. Results

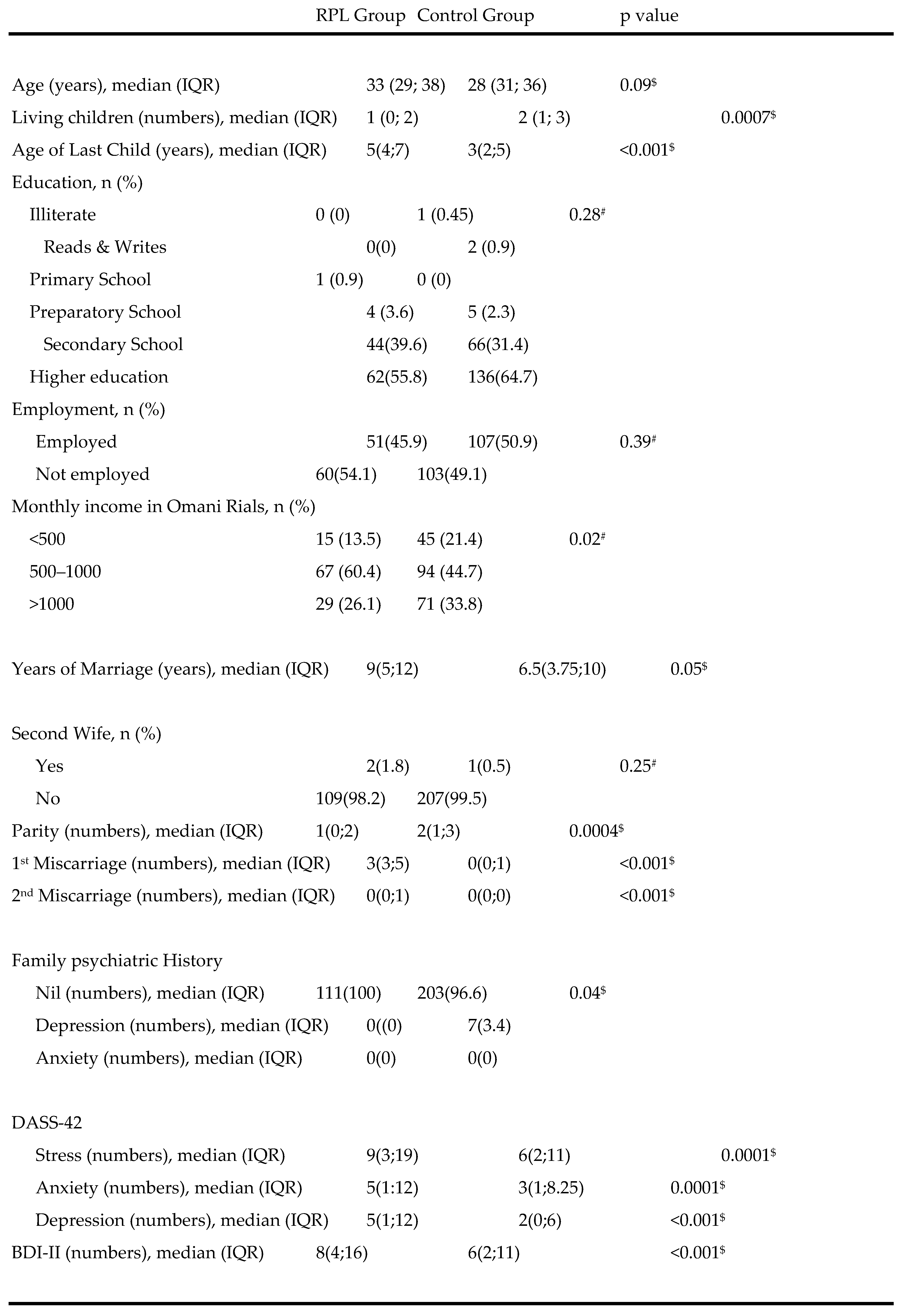

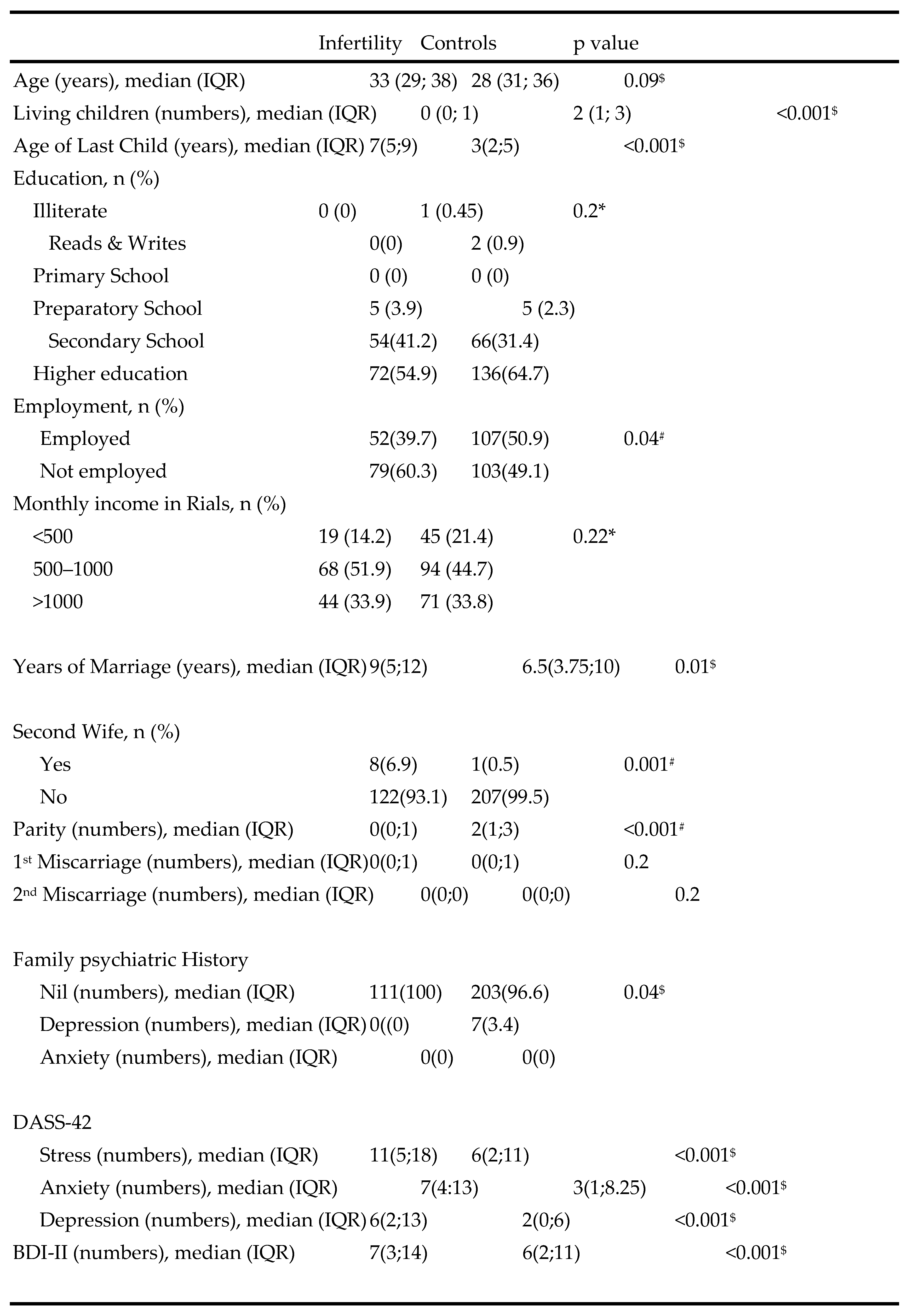

3.1. Study Population Demographics

|

|---|

|

|---|

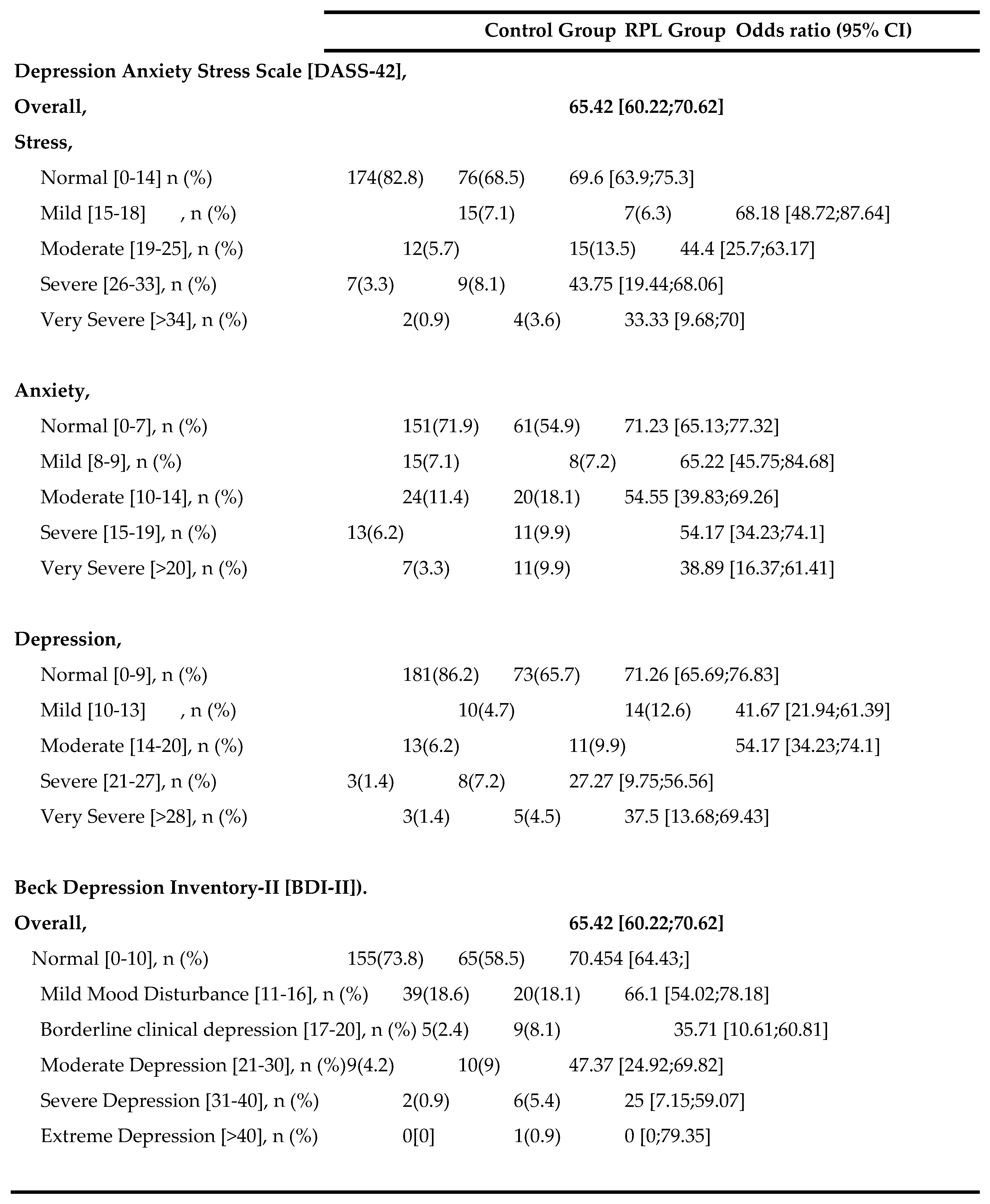

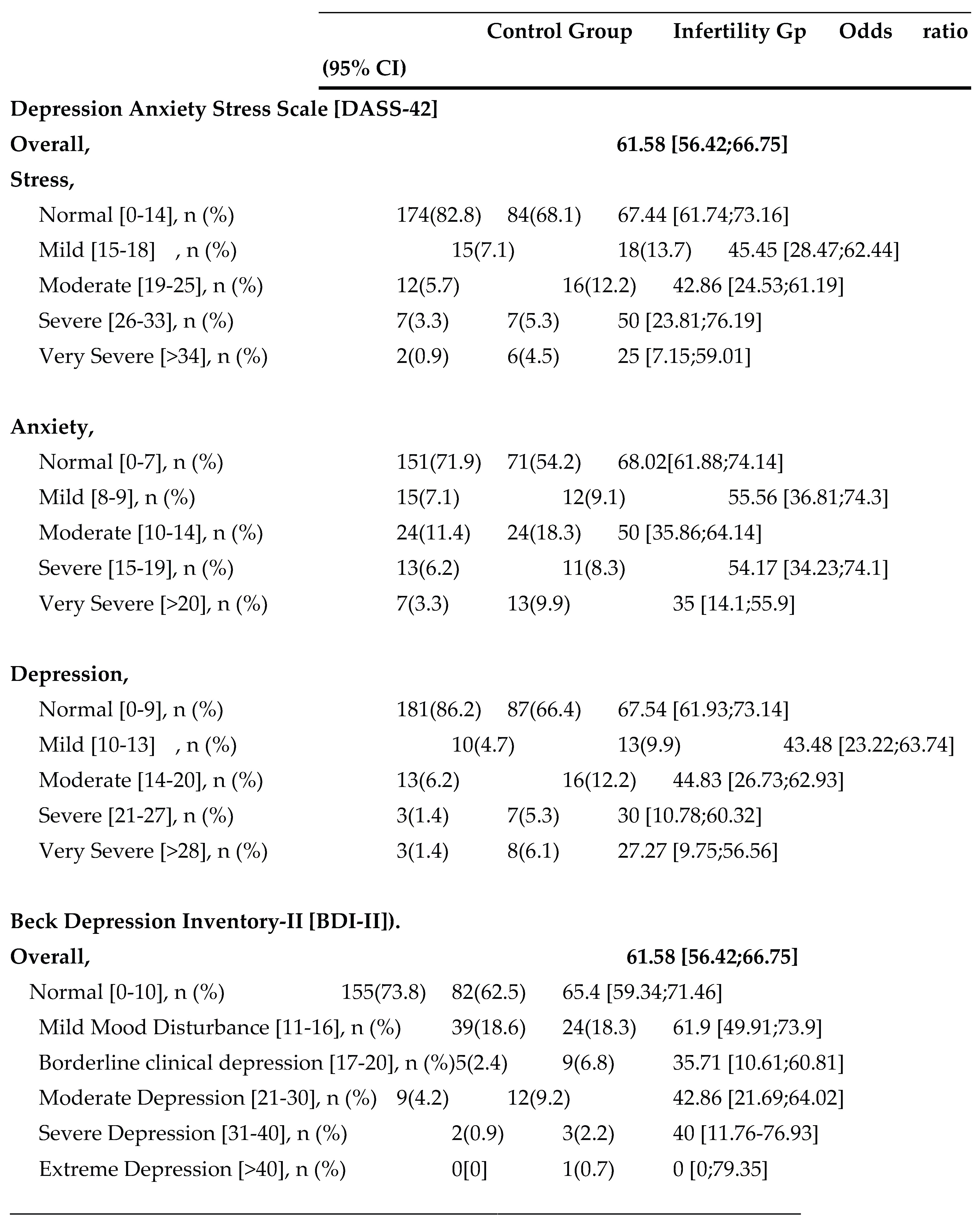

3.2. Prevalence of Stress, Anxiety, and Depression

|

|---|

|

|---|

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of interest

References

- Ewington, LJ; Tewary, S; Brosens, JJ. New insights into the mechanisms underlying recurrent pregnancy loss. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2019, 45, 258–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Hachem, H; Crepaux, V; May-Panloup, P; Descamps, P; Legendre, G; Bouet, PE. Recurrent pregnancy loss: current perspectives. Int J Womens Health. 2017, 9, 331–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eltayeb, SM; Ambusaidi, SK; Gowri, V; Alghafri, WM. Etiological profile of Omani women with recurrent pregnancy loss. Oman Med J. 2021, 36, 249–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morley, L; Shillito, J; Tang, T. Preventing recurrent miscarriage of unknown aetiology. Obstet Gynaecol. 2013, 15, 99–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lok, IH; Neugebauer, R. Psychological morbidity following miscarriage. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2007, 21, 229–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolte, AM; Olsen, LR; Mikkelsen, EM; Christiansen, OB; Nielsen, HS. Depression and emotional stress is highly prevalent among women with recurrent pregnancy loss. Hum Reprod. 2015, 30, 777–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bushnik, T; Cook, JL; Yuzpe, AA; Tough, S; Collins, J. Estimating the prevalence of infertility in Canada. Hum Reprod. 2012, 27, 738–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simionescu, G.; Doroftei, B.; Maftei, R.; Obreja, B.E.; Anton, E.; Grab, D.; Ilea, C.; Anton, C. The complex relationship between infertility and psychological distress (Review). Exp. Ther. Med. 2021, 21, 306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deka, PK; Sarma, S. Psychological aspects of infertility. Indian J Psychol Med. 2010, 32, 3–7. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, D.; Zhouchen, Y.-B.; Li, L.; Jiang, Y.-L.; Liu, Y.; Redding, S. R.; Wang, R.; Ouyang, Y.-Q. The Stigma and Infertility-Related Stress of Chinese Infertile Women: A Cross-Sectional Study. Healthcare 2024, 12, 1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, L; Wang, T; Xu, H; Chen, C; Liu, Z; Kang, X; et al. Prevalence of depression and anxiety in women with recurrent pregnancy loss and the associated risk factors. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2019, 300, 1061–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y; Meng, Z; Pei, J; Qian, L; Mao, B; Li, Y; et al. Anxiety and depression are risk factors for recurrent pregnancy loss: a nested case-control study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2021, 19, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yusuf, L. Depression, anxiety and stress among female patients of infertility; A case-control study. Pak J Med Sci. 2016, 32, 1340–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, A; Sharma, PSVN; Narayan, P; Binu, VS; Dinesh, N; Pai, PJ. Prevalence and predictors of infertility-specific stress in women diagnosed with primary infertility: A clinic-based study. J Hum Reprod Sci. 2016, 9, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maroufizadeh, S; Ghaheri, A; Almasi-Hashiani, A; Mohammadi, M; Navid, B; Ezabadi, Z; et al. The prevalence of anxiety and depression among people with infertility referring to Royan Institute in Tehran, Iran: A cross-sectional questionnaire study. Middle East Fertil Soc J. 2018, 23, 103–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omani-Samani, R; Maroufizadeh, S; Almasi-Hashiani, A; Amini, P. Prevalence of depression and its determinant factors among infertile patients in Iran based on the PHQ-9. Middle East Fertil Soc J. 2018, 23, 460–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haririan, HR; Mohammadpour, Y; Aghajanloo, A. Prevalence of depression and contributing factors of depression in the infertile women referred to Kosar infertility center, 2009. Iran J Obstet Gynecol Infertil. 2010, 13, 45–49. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Alqahtani, A; Al-Khedair, K; Al-Jeheiman, R; Al-Turki, H; Al Qahtani, N. Anxiety and depression during pregnancy in women attending clinics in a University Hospital in Eastern province of Saudi Arabia: prevalence and associated factors. Int J Womens Health. 2018, 10, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Azri, M; Al-Lawati, I; Al-Kamyani, R; Al-Kiyumi, M; Al-Rawahi, A; Davidson, R; et al. Prevalence and Risk Factors of Antenatal Depression among Omani Women in a Primary Care Setting. Sultan Qaboos Univ Med J. 2016, 16, e35–e41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- How Culture Affects Depression. Psychology Today. Available online: https://www.psychologytoday.com/intl/blog/between-cultures/201712/how-culture-affects-depression (accessed on 11 October 2024).

- General (US) Office of the Surgeon; Services (US) Center for Mental Health; Health (US) National Institutes of Mental Health. Chapter 2 Culture Counts: The Influence of Culture and Society on Mental Health. In: Mental Health: Culture, Race, and Ethnicity: A Supplement to Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (US). 2001. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK44249/ (accessed on 11 October 2024).

- Gotlib, IH; Hammen, CL (Eds.) Handbook of Depression, 2nd ed.; Guilford Press: New York, 2010. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).