Submitted:

31 December 2025

Posted:

31 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

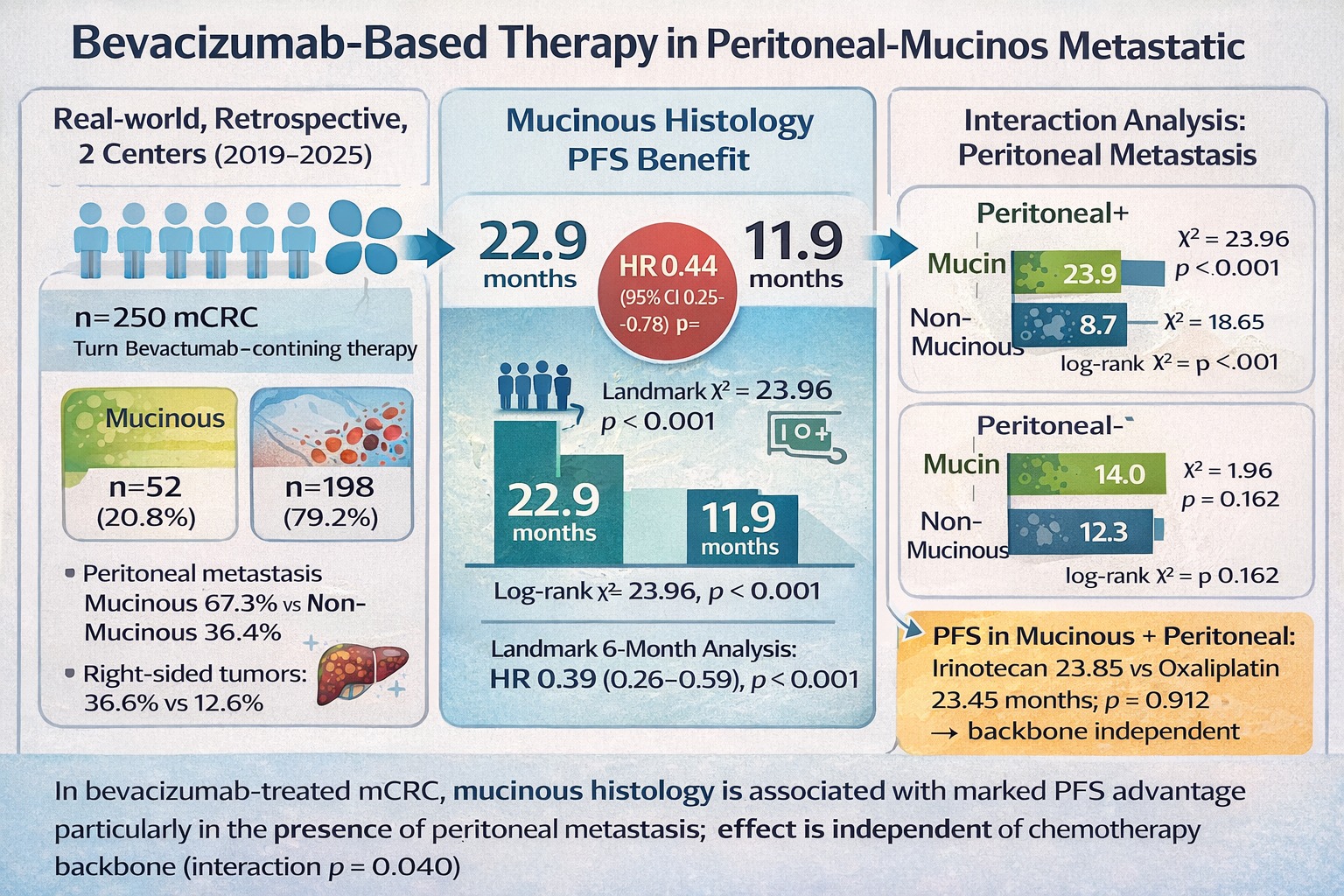

Objective: In metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC), mucinous histology has been associated with poor clinical outcomes, particularly in the presence of peritoneal metastasis. However, it remains unclear whether mucinous histology exerts a context-dependent effect on treatment outcomes by modifying the efficacy of anti–vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)–based therapies independently of metastatic dissemination patterns and chemotherapy backbone. Methods: We retrospectively analyzed 250 patients with mCRC treated with bevacizumab-containing systemic therapy. Tumors were classified as mucinous (n = 52) or non-mucinous (n = 198). Progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) were estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method and compared using the log-rank test. Cox proportional hazards regression models were applied for univariate and multivariate analyses. Predefined subgroup analyses were conducted according to peritoneal metastasis status and chemotherapy backbone (oxaliplatin- or irinotecan-based). A 6-month landmark analysis was performed to reduce early progression bias. Interaction analyses evaluated potential effect modification between histology, peritoneal metastasis, and chemotherapy backbone. Results: Mucinous tumors were more frequently right-sided and strongly associated with peritoneal metastasis. In the overall cohort, mucinous histology was associated with significantly longer median PFS compared with non-mucinous histology (22.9 vs. 11.9 months; p < 0.001). This benefit was driven by patients with peritoneal metastasis, in whom mucinous histology was associated with markedly prolonged PFS (23.9 vs. 8.7 months; p < 0.001). No significant PFS difference according to histology was observed in patients without peritoneal metastasis. On multivariate analysis, mucinous histology remained independently associated with improved PFS (HR 0.44; 95% CI 0.25–0.78; p = 0.005), an effect preserved in the landmark cohort (HR 0.39; 95% CI 0.26–0.59; p < 0.001). A significant interaction between mucinous histology and peritoneal metastasis was observed (p for interaction = 0.040), indicating that the prognostic impact of histology differed according to metastatic pattern. No significant PFS difference or interaction was detected according to chemotherapy backbone within the mucinous subgroup. Conclusion: Among bevacizumab-treated patients with mCRC, mucinous histology—particularly in the presence of peritoneal metastasis—is associated with a pronounced PFS advantage independent of chemotherapy backbone. These findings suggest that mucinous peritoneal mCRC represents a biologically and clinically distinct subgroup that may derive context-specific and disproportionate benefit from anti-VEGF–based strategies, warranting prospective validation.

Keywords:

Introduction

Materials and Methods

Study Design

Patient Population

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

- (i)

- age ≥18 years,

- (ii)

- presence of metastatic disease,

- (iii)

- receipt of bevacizumab-based systemic therapy,

- (iv)

- clearly documented histological subtype in pathology reports, and

- (v)

- availability of follow-up data after treatment initiation.

Data Collection and Variables

Treatment and Response Assessment

Endpoints

Ethics Approval

Statistical Analysis

Results

Patient Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

Progression-Free Survival in the Overall Cohort

Cox Regression Analysis

Subgroup Analysis by Peritoneal Metastasis

Subgroup Analysis by Chemotherapy Backbone

Overall Survival: Cox Regression Analysis

Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Morgan, E.; Arnold, M.; Gini, A.; Lorenzoni, V.; Cabasag, C.J.; Laversanne, M.; et al. Global burden of colorectal cancer in 2020 and 2040: incidence and mortality estimates from GLOBOCAN. Gut 2023, 72(2), 338–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eide, P.W.; Moosavi, S.H.; Eilertsen, I.A.; Brunsell, T.H.; Langerud, J.; Berg, K.C.G.; et al. Metastatic heterogeneity of the consensus molecular subtypes of colorectal cancer. NPJ Genom Med. 2021, 6(1), 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, C.; Cen, S.; Ding, G.; Wu, W. Mucinous colorectal adenocarcinoma: clinical pathology and treatment options. Cancer Commun (Lond) 2019, 39(1), 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dienstmann, R.; Vermeulen, L.; Guinney, J.; Kopetz, S.; Tejpar, S.; Tabernero, J. Consensus molecular subtypes and the evolution of precision medicine in colorectal cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 2017, 17(2), 79–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winder, T.; Lenz, H.J. Mucinous adenocarcinomas with intra-abdominal dissemination: a review of current therapy. Oncologist 2010, 15(8), 836–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catalano, V.; Bergamo, F.; Cremolini, C.; Vincenzi, B.; Negri, F.; Giordani, P.; et al. Clinical impact of first-line bevacizumab plus chemotherapy in metastatic colorectal cancer of mucinous histology: a multicenter, retrospective analysis on 685 patients. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2020, 146(2), 493–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekenkamp, L.J.; Heesterbeek, K.J.; Koopman, M.; Tol, J.; Teerenstra, S.; Venderbosch, S.; et al. Mucinous adenocarcinomas: poor prognosis in metastatic colorectal cancer. Eur J Cancer 2012, 48(4), 501–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Sandhu, J.; Fakih, M. Mucinous Histology Is Associated with Resistance to Anti-EGFR Therapy in Patients with Left-Sided RAS/BRAF Wild-Type Metastatic Colorectal Cancer. Oncologist 2022, 27(2), 104–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allodji, R.S.; Schwartz, B.; Diallo, I.; Agbovon, C.; Laurier, D.; de Vathaire, F. Simulation-extrapolation method to address errors in atomic bomb survivor dosimetry on solid cancer and leukaemia mortality risk estimates, 1950-2003. Radiat Environ Biophys. 2015, 54(3), 273–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catalano, V.; Loupakis, F.; Graziano, F.; Torresi, U.; Bisonni, R.; Mari, D.; et al. Mucinous histology predicts for poor response rate and overall survival of patients with colorectal cancer and treated with first-line oxaliplatin- and/or irinotecan-based chemotherapy. Br J Cancer 2009, 100(6), 881–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nozoe, T.; Anai, H.; Nasu, S.; Sugimachi, K. Clinicopathological characteristics of mucinous carcinoma of the colon and rectum. J Surg Oncol. 2000, 75(2), 103–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moretto, R.; Morano, F.; Ongaro, E.; Rossini, D.; Pietrantonio, F.; Casagrande, M.; et al. Lack of Benefit From Anti-EGFR Treatment in RAS and BRAF Wild-type Metastatic Colorectal Cancer With Mucinous Histology or Mucinous Component. Clin Colorectal Cancer 2019, 18(2), 116–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ten Hoorn, S.; de Back, T.R.; Sommeijer, D.W.; Vermeulen, L. Clinical Value of Consensus Molecular Subtypes in Colorectal Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2022, 114(4), 503–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franko, J.; Shi, Q.; Meyers, J.P.; Maughan, T.S.; Adams, R.A.; Seymour, M.T.; et al. Prognosis of patients with peritoneal metastatic colorectal cancer given systemic therapy: an analysis of individual patient data from prospective randomised trials from the Analysis and Research in Cancers of the Digestive System (ARCAD) database. Lancet Oncol. 2016, 17(12), 1709–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommariva, A.; Tonello, M.; Coccolini, F.; De Manzoni, G.; Delrio, P.; Pizzolato, E.; et al. Colorectal Cancer with Peritoneal Metastases: The Impact of the Results of PROPHYLOCHIP, COLOPEC, and PRODIGE 7 Trials on Peritoneal Disease Management. Cancers (Basel) 2022, 15(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zucchini, V.; D'Acapito, F.; Rapposelli, I.G.; Framarini, M.; Di Pietrantonio, D.; Turrini, R.; et al. Impact of RAS, BRAF mutations and microsatellite status in peritoneal metastases from colorectal cancer treated with cytoreduction + HIPEC: scoping review. Int J Hyperthermia 2025, 42(1), 2479527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, L.; Wang, F.; Li Z-z Ren, C.; Zhang D-s Zhao, Q.; et al. Chemotherapy plus bevacizumab versus chemotherapy plus cetuximab as first-line treatment for patients with metastatic colorectal cancer: Results of a registry-based cohort analysis. Medicine 2016, 95(51), e4531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westgaard, I.H.; Dissen, E.; Torgersen, K.M.; Lazetic, S.; Lanier, L.L.; Phillips, J.H.; et al. The lectin-like receptor KLRE1 inhibits natural killer cell cytotoxicity. J Exp Med. 2003, 197(11), 1551–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, D.; Schneeberger, C.; Czerwenka, K.; Schmutzler, R.K.; Speiser, P.; Kucera, E.; et al. Messenger RNA determination of estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, pS2, and plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 by competitive reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction in human breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 1999, 5(6), 1497–502. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Feagan, B. Infliximab in the treatment of Crohn's disease. Can J Gastroenterol. 2000, 14 Suppl C, 6c. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, L.; Wang, F.; Li, Z.Z.; Ren, C.; Zhang, D.S.; Zhao, Q.; et al. Chemotherapy plus bevacizumab versus chemotherapy plus cetuximab as first-line treatment for patients with metastatic colorectal cancer: Results of a registry-based cohort analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016, 95(51), e4531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guinney, J.; Dienstmann, R.; Wang, X.; de Reyniès, A.; Schlicker, A.; Soneson, C.; et al. The consensus molecular subtypes of colorectal cancer. Nat Med. 2015, 21(11), 1350–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | Total cohort (n=250) | Mucinous (n=52) | Non-mucinous (n=198) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic characteristics | ||||

| Age <65 years, n | 114 | 26 (22.8%) | 88 (77.2%) | 0.474 |

| Age ≥65 years, n | 136 | 26 (19.1%) | 110 (80.9%) | |

| Male sex, n | 156 | 35 (22.4%) | 121 (77.6%) | 0.412 |

| Female sex, n | 94 | 17 (18.1%) | 77 (81.9%) | |

| BMI <25 kg/m², n | 98 | 17 (17.3%) | 81 (82.7%) | 0.491 |

| BMI 25–29.9 kg/m², n | 99 | 24 (24.2%) | 75 (75.8%) | |

| BMI ≥30 kg/m², n | 53 | 11 (20.8%) | 42 (79.2%) | |

| Clinical status | ||||

| ECOG 0–1, n | 168 | 34 (20.2%) | 134 (79.8%) | 0.754 |

| ECOG ≥2, n | 82 | 18 (22.0%) | 64 (78.0%) | |

| Primary tumor characteristics | ||||

| Right colon, n | 71 | 26 (36.6%) | 45 (63.4%) | <0.001 |

| Left colon, n | 87 | 11 (12.6%) | 76 (87.4%) | |

| Rectum, n | 92 | 15 (16.3%) | 77 (83.7%) | |

| Molecular characteristics | ||||

| MSI-H†, n | 8 | 3 (37.5%) | 5 (62.5%) | 0.177 |

| MSS / MSI-L†, n | 143 | 26 (18.2%) | 117 (81.8%) | |

| RAS mutation present, n | 164 | 34 (20.7%) | 130 (79.3%) | 0.873 |

| BRAF V600E mutation present†, n | 11 | 3 (27.3%) | 8 (72.7%) | 0.435 |

| Disease presentation and metastatic pattern | ||||

| De novo metastatic disease, n | 153 | 30 (19.6%) | 123 (80.4%) | 0.560 |

| Recurrent metastatic disease, n | 97 | 22 (22.7%) | 75 (77.3%) | |

| Peritoneal metastasis present, n | 107 | 35 (32.7%) | 72 (67.3%) | <0.001 |

| Liver metastasis present, n | 181 | 30 (16.6%) | 151 (83.4%) | 0.008 |

| Lung metastasis present, n | 146 | 22 (15.1%) | 124 (84.9%) | 0.008 |

| Ovarian metastasis present, n | 19 | 8 (42.1%) | 11 (57.9%) | 0.017 |

| Bone metastasis present, n | 52 | 11 (21.2%) | 41 (78.8%) | 0.944 |

| Brain metastasis present, n | 9 | 2 (22.2%) | 7 (77.8%) | 0.915 |

| Treatment characteristics | ||||

| Bevacizumab 1st-line, n | 198 | 41 (20.7%) | 157 (79.3%) | 0.869 |

| Bevacizumab ≥2nd-line, n | 51 | 11 (21.6%) | 40 (78.4%) | |

| Oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy, n | 135 | 24 (17.8%) | 111 (82.2%) | 0.202 |

| Irinotecan-based chemotherapy, n | 115 | 28 (24.3%) | 87 (75.7%) | |

| Bevacizumab + FOLFOX, n | 125 | 20 (16.0%) | 105 (84.0%) | 0.088 |

| Bevacizumab + FOLFIRI, n | 115 | 28 (24.3%) | 87 (75.7%) | |

| Bevacizumab + CAPOX, n | 10 | 4 (40.0%) | 6 (60.0%) | |

| Treatment response | ||||

| Complete response (CR), n | 6 | 1 (16.7%) | 5 (83.3%) | 0.088 |

| Partial response (PR), n | 132 | 19 (14.4%) | 113 (85.6%) | |

| Stable disease (SD), n | 83 | 26 (31.3%) | 57 (68.7%) | |

| Progressive disease (PD), n | 29 | 6 (20.7%) | 23 (79.3%) |

| Analysis Stratum | Treatment Group | Median PFS (months) | 95% Confidence Interval | Log-rank χ² | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall cohort | Non-mucinous (n = 198) | 11.9 | 10.22–13.58 | ||

| Mucinous (n = 52) | 22.9 | 17.95–27.85 | 23.96 | <0.001 | |

| Patients with peritoneal metastasis | Non-mucinous (n = 72) | 8.7 | 6.29–11.12 | ||

| Mucinous (n = 35) | 23.9 | 19.81–27.89 | 18.65 | <0.001 | |

| Patients without peritoneal metastasis | Non-mucinous (n = 126) | 12.3 | 11.03–13.57 | ||

| Mucinous (n = 17) | 14.0 | 9.51–18.49 | 1.96 | 0.162 | |

| Non-mucinous subgroup | Oxaliplatin-based (n = 111) | 11.6 | 8.59–14.67 | ||

| Irinotecan-based (n = 87) | 12.0 | 9.59–14.41 | 0.03 | 0.863 | |

| Mucinous subgroup | Oxaliplatin-based (n = 24) | 16.2 | 8.18–24.22 | ||

| Irinotecan-based (n = 28) | 24.1 | 18.34–29.86 | 1.72 | 0.190 | |

| Mucinous histology with peritoneal metastasis | Oxaliplatin-based (n = 13) | 23.45 | 15.61–31.29 | ||

| Irinotecan-based (n = 22) | 23.85 | 18.48–29.22 | 0.01 | 0.912 |

| Variable | Univariate HR (95% CI) | p value | Multivariate HR (95% CI) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age ≥65 years | 1,30 (0,97–1,74) | 0,085 | — | — |

| Male sex | 1,01 (0,75–1,36) | 0,960 | — | — |

| BMI ≥30 kg/m² | 0,78 (0,54–1,13) | 0,183 | — | — |

| ECOG performance status ≥2 | 1,22 (0,90–1,65) | 0,200 | — | — |

| Mucinous histology | 0,39 (0,26–0,58) | <0,001 | 0,44 (0,25–0,78) | 0,005 |

| Right-sided primary tumor | 1,28 (0,92–1,77) | 0,138 | — | — |

| De novo metastatic disease | 0,64 (0.47-0.88) | 0,005 | 0,79 (0,52–1,20) | 0,264 |

| Peritoneal metastasis present | 0,66 (0,48–0,90) | 0,008 | 0,92 (0,60–1,40) | 0,693 |

| Liver metastasis present | 2,35 (1,63–3,37) | <0,001 | 1,62 (0,95–2,78) | 0,079 |

| Lung metastasis present | 0,91 (0,68–1,23) | 0,547 | — | — |

| RAS mutation present | 0,99 (0,72–1,36) | 0,959 | — | — |

| BRAF V600E mutation present | 0,64 (0,31–1,32) | 0,233 | — | — |

| MSI-H status | 0,35 (0,13–0,96) | 0,040 | 0,39 (0,14–1,10) | 0,074 |

| Irinotecan-based chemotherapy (vs oxaliplatin-based) | 0,85 (0,64–1,14) | 0,285 | — | — |

| Bevacizumab used as ≥2nd-line therapy | 1,19 (0,84–1,69) | 0,323 | — | — |

| Interaction term | HR (95% CI) | p for interaction |

|---|---|---|

| Mucinous histology × Peritoneal metastasis | 0,45 (0,21 – 0,97) | 0,040 |

| Mucinous histology × Irinotecan-based chemotherapy | 0,73 (0,38 – 1,39) | 0,341 |

| Peritoneal metastasis × Irinotecan-based chemotherapy | 1,02 (0,63 – 1,64) | 0,935 |

| Variable | Univariate HR (95% CI) | p value | Multivariate HR (95% CI) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age ≥65 years | 1.44 (1.05–1.97) | 0.022 | 1.38 (1.01–1.89) | 0.041 |

| Male sex | 0.93 (0.68–1.27) | 0.644 | — | — |

| BMI ≥30 kg/m² | 0.86 (0.59–1.26) | 0.449 | — | — |

| ECOG performance status ≥2 | 1.29 (0.94–1.76) | 0.113 | — | — |

| Mucinous histology | 0.65 (0.44–0.97) | 0.036 | 0.81 (0.54–1.23) | 0.328 |

| Right-sided primary tumor | 1.05 (0.75–1.47) | 0.779 | — | — |

| De novo metastatic disease | 0.43 (0.31-0.60) | <0.001 | 0.49 (0.35–0.69) | <0.001 |

| Peritoneal metastasis present | 0.93 (0.68–1.26) | 0.624 | — | — |

| Liver metastasis present | 2.35 (1.62–3.41) | <0.001 | 1.80 (1.21–2.67) | 0.004 |

| Lung metastasis present | 1.34 (0.98–1.84) | 0.071 | 1.41 (1.01–1.95) | 0.043 |

| RAS mutation present | 1.29 (0.92–1.80) | 0.143 | — | — |

| BRAF V600E mutation present | 0.56 (0.25–1.23) | 0.144 | — | — |

| MSI-H status | 0.57 (0.21–1.58) | 0.276 | — | — |

| Irinotecan-based chemotherapy (vs oxaliplatin-based) | 0.84 (0.62–1.14) | 0.266 | — | — |

| Bevacizumab used as ≥2nd-line therapy | 0.70 (0.48–1.02) | 0.066 | 0.69 (0.47–1.02) | 0.062 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.