Submitted:

30 December 2025

Posted:

31 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. lncRNAs as Orchestrators of Cancer Initiation and Progression

2.1. Biogenesis, Classification, and Regulatory Modalities of lncRNAs

2.2. lncRNAs in Cancer Hallmarks

2.3. Oncogenic and Tumor-Suppressive lncRNAs: Context Dependency and Regulatory Balance

2.4. Early lncRNA Dysregulation in Carcinogenesis: Implications for Prevention

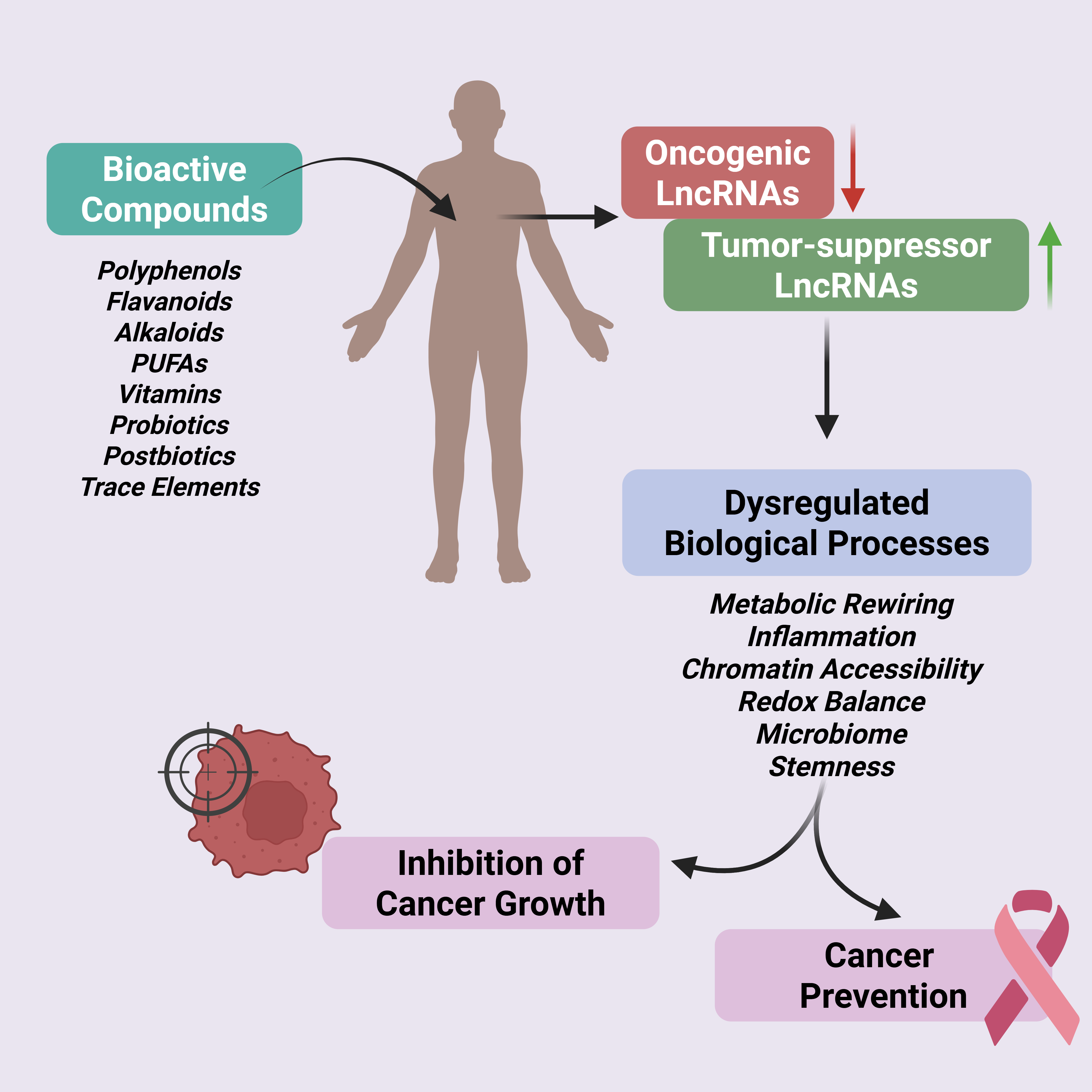

3. Nutritional Regulation of lncRNAs: A Precision Modulation Framework

3.1. Nutrition as a Modulator of lncRNA-Driven Oncogenic Pathways

3.2. Precision Nutrition as a Context for lncRNA-Mediated Cancer Modulation

3.3. Dietary Bioactive Compounds as Regulators of lncRNAs

3.4. Moving Beyond Antioxidant Paradigms Toward lncRNA-Centric Mechanisms

4. Nutritional Modulation of lncRNAs: Molecular and Pathway-Level Insights

4.1. Polyphenols and Flavonoids as lncRNA-Modulating Agents in Cancer

4.1.1. Curcumin: Repression of Oncogenic lncRNAs and EMT-Associated Programs

4.1.2. Resveratrol: Modulation lncRNA-Driven Proliferative and Stress-Response Pathways

4.1.3. EGCG, Quercetin, and Berberine: lncRNA Regulation Across Diverse Cancer Contexts

4.1.4. Convergent Signaling Axes Regulated by Polyphenol-Sensitive lncRNAs

4.2. Omega-3 and Omega-6 Fatty Acids: lncRNA-Mediated Control of Inflammation, Metabolism, and Tumor Progression

4.2.1. EPA and DHA: Repression of Pro-Tumorigenic lncRNAs and Epigenetic Remodeling

4.2.2. lncRNAs in Fatty Acid–Regulated Inflammation and Macrophage Polarization

4.2.3. lncRNA Control of Lipid-Sensitive Transcriptional Regulators: PPARγ and AMPK

4.3. Niacin, NAD⁺ Metabolism, and Sirtuin–lncRNA Axes in Cancer Regulation

4.3.1. Sirtuin-lncRNA Interactions in Chromatin Remodeling and Tumor Suppression

4.3.2. NAD⁺ Salvage Pathway, NAMPT, and lncRNA Control of Metabolic Plasticity

4.3.3. PARP Activity, DNA Damage Responses, and lncRNA Regulation

4.4. Folate, One-Carbon Metabolism, and lncRNA-Driven Epigenetic Regulation

4.4.1. Vitamin B-Dependent DNA Methylation and lncRNA Expression

4.4.2. lncRNAs as Regulators of One-Carbon Metabolic Enzymes

4.5. Vitamin D-lncRNA Networks in Cancer Regulation

4.5.1. VDR-Regulated lncRNAs in Proliferation and Differentiation

4.5.2. Vitamin D, Immune Regulation, and lncRNA-Mediated Tumor Microenvironment Control

4.6. Probiotics and Postbiotics in lncRNA-Mediated Prevention of Colorectal Carcinogenesis

4.7. Essential Trace Elements-lncRNA Axis in Cancer

5. Integrative and Systems-Level Approaches to Decode Nutrient–lncRNA-Cancer Networks

5.1. Rationale for Systems-Level Analysis of Nutrient-Responsive lncRNA Regulation

5.2. Multi-Omics Integration to Map lncRNA-Centered Cancer Regulatory Circuits

5.3. Network Inference and Pathway Modeling of Nutrient–lncRNA Interactions

5.4. Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning for Predictive lncRNA-Guided Nutrition Strategies

5.5. Translational Applications: Biomarkers, Liquid Biopsies, and Prevention-Focused Trials

5.6. Challenges and Future Directions

6. Therapeutic and Preventive Potential of Nutrition-lncRNA Axis

6.1. Targeting Oncogenic lncRNAs Through Dietary Bioactive Compounds

6.2. Modulating Inflammatory and Immune-Permissive lncRNA Networks

6.3. Metabolic Checkpoint lncRNAs as Leverage Points for Chemoprevention

6.4. Epigenetic Vulnerability Windows Defined by Folate- and Vitamin D–Responsive lncRNAs

6.5. Toward lncRNA-Guided Precision Prevention Strategies

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AI | Artificial intelligence |

| AMPK | AMP-activated protein kinase |

| APC | Adenomatous polyposis coli |

| AKT | Protein kinase B |

| ATP | Adenosine triphosphate |

| β-catenin | Beta-catenin |

| ccRNA | Competing endogenous RNA |

| DHA | Docosahexaenoic acid |

| DNMT | DNA methyltransferase |

| EGCG | Epigallocatechin gallate |

| EMT | Epithelial–mesenchymal transition |

| EPA | Eicosapentaenoic acid |

| FOXO | Forkhead box O |

| HOTAIR | HOX transcript antisense RNA |

| IL | Interleukin |

| lncRNA | Long non-coding RNA |

| MALAT1 | Metastasis-associated lung adenocarcinoma transcript 1 |

| MAPK | Mitogen-activated protein kinase |

| MEG3 | Maternally expressed gene 3 |

| miRNA | MicroRNA |

| ML | Machine learning |

| mTOR | Mechanistic target of rapamycin |

| NAD⁺ | Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide |

| NAMPT | Nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase |

| NBR2 | Neighbor of BRCA1 gene 2 |

| NEAT1 | Nuclear paraspeckle assembly transcript 1 |

| NF-κB | Nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells |

| PARP | Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase |

| PI3K | Phosphoinositide 3-kinase |

| PPARγ | Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma |

| PUFA | Polyunsaturated fatty acid |

| SAM | S-adenosylmethionine |

| SIRT | Sirtuin |

| STAT | Signal transducer and activator of transcription |

| TGF-β | Transforming growth factor beta |

| TNF-α | Tumor necrosis factor alpha |

| UCA1 | Urothelial carcinoma-associated 1 |

| VDR | Vitamin D receptor |

| Wnt | Wingless-related integration site |

References

- Hanahan, D. Hallmarks of Cancer: New Dimensions. Cancer Discov 2022, 12(1), 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; et al. Inflammation and tumor progression: signaling pathways and targeted intervention. Signal transduction and targeted therapy 2021, 6(1), 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- You, M.; et al. Signaling pathways in cancer metabolism: mechanisms and therapeutic targets. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy 2023, 8(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, S.; Almagro, J.; Fuchs, E. Beyond genetics: driving cancer with the tumour microenvironment behind the wheel. Nature Reviews Cancer 2024, 24(4), 274–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nadhan, R.; et al. LncRNAs and the cancer epigenome: Mechanisms and therapeutic potential. Cancer Letters 2024, 605, 217297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadhan, R.; et al. Signaling by LncRNAs: Structure, Cellular Homeostasis, and Disease Pathology. Cells 2022, 11(16), 2517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadhan, R.; Dhanasekaran, D.N. Decoding the Oncogenic Signals from the Long Non-Coding RNAs. Onco 2021, 1(2), 176–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadhan, R.; Dhanasekaran, D.N. Regulation of Tumor Metabolome by Long Non-Coding RNAs. Journal of Molecular Signaling 2022, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadhan, R.; et al. Long non-coding RNAs in cancer, in Handbook of Oncobiology: From Basic to Clinical Sciences; Springer, 2024; pp. 773–817. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, C.; et al. Role of long non-coding RNAs in cancer: From subcellular localization to nanoparticle-mediated targeted regulation. Molecular Therapy - Nucleic Acids 2023, 33, 774–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhan, A.; Soleimani, M.; Mandal, S.S. Long Noncoding RNA and Cancer: A New Paradigm. Cancer Research 2017, 77(15), 3965–3981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statello, L.; et al. Gene regulation by long non-coding RNAs and its biological functions. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology 2021, 22(2), 96–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayakawa, S.; et al. Contribution of Non-Coding RNAs to Anticancer Effects of Dietary Polyphenols: Chlorogenic Acid, Curcumin, Epigallocatechin-3-Gallate, Genistein, Quercetin and Resveratrol. Antioxidants 2022, 11(12), 2352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovell, C.D.; Anguera, M.C. Long Noncoding RNAs That Function in Nutrition: Lnc-ing Nutritional Cues to Metabolic Pathways. Annual Review of Nutrition 2022, 42(1), 251–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishida, A.; Andoh, A. The role of inflammation in cancer: mechanisms of tumor initiation, progression, and metastasis. Cells 2025, 14(7), 488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalhori, M.R.; et al. Regulation of Long Non-Coding RNAs by Plant Secondary Metabolites: A Novel Anticancer Therapeutic Approach. Cancers 2021, 13(6), 1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, V.K.; et al. Precision nutrition-based strategy for management of human diseases and healthy aging: Current progress and challenges forward. Frontiers in Nutrition 2024, 11, 1427608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, D.; et al. Nutrigenomics and Personalized Diets-Tailoring Nutrition for Optimal Health. In Applied Food Research; 2025; p. 100980. [Google Scholar]

- Salido-Guadarrama, I.; Romero-Cordoba, S.L.; Rueda-Zarazua, B. Multi-omics mining of lncRNAs with biological and clinical relevance in cancer. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2023, 24(23), 16600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biersack, B. Non-coding RNA/microRNA-modulatory dietary factors and natural products for improved cancer therapy and prevention: Alkaloids, organosulfur compounds, aliphatic carboxylic acids and water-soluble vitamins. Non-coding RNA Research 2016, 1(1), 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, S.; et al. Dietary flavonoids as modulators of non-coding RNAs in hormone-associated cancer. Food Chemistry Advances 2023, 2, 100321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, H.-S. Single-cell multi-omics as a window into the non-coding transcriptome. Hereditas 2025, 162(1), 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhang, X.; Liu, C. The computational approaches of lncRNA identification based on coding potential: status quo and challenges. Computational and Structural Biotechnology Journal 2020, 18, 3666–3677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.-L.; et al. Effects of dietary intervention on human diseases: molecular mechanisms and therapeutic potential. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy 2024, 9(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, V.K.; et al. Precision nutrition-based strategy for management of human diseases and healthy aging: current progress and challenges forward. Frontiers in Nutrition 2024, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajabi, S.; et al. Long Non-Coding RNAs as Novel Targets for Phytochemicals to Cease Cancer Metastasis. Molecules 2023, 28(3), 987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Homayoonfal, M.; Asemi, Z.; Yousefi, B. Targeting long non coding RNA by natural products: Implications for cancer therapy. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition 2023, 63(20), 4389–4417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, M.; Srinivasan, A. Epigenetic Gene Regulation by Dietary Compounds in Cancer Prevention. Advances in Nutrition 2019, 10(6), 1012–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, A.M.; Chang, H.Y. Long Noncoding RNAs in Cancer Pathways. Cancer Cell 2016, 29(4), 452–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattick, J.S.; et al. Long non-coding RNAs: definitions, functions, challenges and recommendations. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology 2023, 24(6), 430–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basu, S.; Nadhan, R.; Dhanasekaran, D.N. Long Non-Coding RNAs in Ovarian Cancer: Mechanistic Insights and Clinical Applications. Cancers 2025, 17(3), 472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridges, M.C.; Daulagala, A.C.; Kourtidis, A. LNCcation: lncRNA localization and function. Journal of Cell Biology 2021, 220(2). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, N.; et al. Long Non-Coding RNAs: The Regulatory Mechanisms, Research Strategies, and Future Directions in Cancers. Frontiers in Oncology 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eun, J.W.; et al. A New Understanding of Long Non-Coding RNA in Hepatocellular Carcinoma—From m6A Modification to Blood Biomarkers. Cells 2023, 12(18), 2272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, J.H.; et al. Deciphering a GPCR-lncrna-miRNA nexus: Identification of an aberrant therapeutic target in ovarian cancer. Cancer Letters 2024, 591, 216891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segal, D. J. Dostie, The Talented LncRNAs: Meshing into Transcriptional Regulatory Networks in Cancer. Cancers 2023, 15(13), 3433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, R.-Z.; Luo, D.-X.; Mo, Y.-Y. Emerging roles of lncRNAs in the post-transcriptional regulation in cancer. Genes & Diseases 2019, 6(1), 6–15. [Google Scholar]

- Herman, A.B.; Tsitsipatis, D.; Gorospe, M. Integrated lncRNA function upon genomic and epigenomic regulation. Molecular Cell 2022, 82(12), 2252–2266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, W.X.; Koirala, P.; Mo, Y.Y. LncRNA-mediated regulation of cell signaling in cancer. Oncogene 2017, 36(41), 5661–5667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.; et al. Signaling pathways involved in colorectal cancer: pathogenesis and targeted therapy. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy 2024, 9(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.-Z.; Liu, H.; Chen, S.-R. Mechanisms of Long Non-Coding RNAs in Cancers and Their Dynamic Regulations. Cancers 2020, 12(5), 1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baba, S.K.; et al. Long non-coding RNAs modulate tumor microenvironment to promote metastasis: novel avenue for therapeutic intervention. Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, M.; et al. Involvement of lncRNAs in cancer cells migration, invasion and metastasis: cytoskeleton and ECM crosstalk. Journal of Experimental & Clinical Cancer Research 2023, 42(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, J.; et al. LncRNAs in tumor metabolic reprogramming and tumor microenvironment remodeling. Frontiers in Immunology 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathy, N.W.; Chen, X.-M. Long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) and their transcriptional control of inflammatory responses. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2017, 292(30), 12375–12382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gluba-Sagr, A.; et al. The Role of Selected lncRNAs in Lipid Metabolism and Cardiovascular Disease Risk. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2024, 25(17), 9244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; et al. Regulatory function of glycolysis-related lncRNAs in tumor progression: Mechanism, facts, and perspectives. Biochemical Pharmacology 2024, 229, 116511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; et al. Role of LncRNAs in regulating cancer amino acid metabolism. Cancer Cell International 2021, 21(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kacso, T.P.; et al. Reactive Oxygen Species and Long Non-Coding RNAs, an Unexpected Crossroad in Cancer Cells. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2022, 23(17), 10133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Xie, Y.; Luo, Y. The Role of Long Non-Coding RNAs in the Tumor Immune Microenvironment. Frontiers in Immunology 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; et al. Pan-cancer characterization of lncRNA modifiers of immune microenvironment reveals clinically distinct de novo tumor subtypes. npj Genomic Medicine 2021, 6(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Y.-H. Crosstalk of lncRNA and Cellular Metabolism and Their Regulatory Mechanism in Cancer. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2020, 21(8), 2947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.; et al. Oncogene or tumor suppressor? Long noncoding RNAs role in patient's prognosis varies depending on disease type. Translational Research 2021, 230, 98–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taniue, K.; Akimitsu, N. The Functions and Unique Features of LncRNAs in Cancer Development and Tumorigenesis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2021, 22(2), 632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, Y.; et al. Tumor-suppressive function of long noncoding RNA MALAT1 in glioma cells by downregulation of MMP2 and inactivation of ERK/MAPK signaling. Cell Death & Disease 2016, 7(3), e2123–e2123. [Google Scholar]

- Pickard, M.; Williams, G. Molecular and Cellular Mechanisms of Action of Tumour Suppressor GAS5 LncRNA. Genes 2015, 6(3), 484–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; et al. Long non-coding RNAs involved in cancer metabolic reprogramming. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences 2019, 76(3), 495–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; et al. Long non-coding RNAs in cancer glycolysis and metabolism: mechanisms and translational opportunities. Cell Death & Disease 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arunkumar, G. LncRNAs: the good, the bad, and the unknown. Biochemistry and Cell Biology 2024, 102(1), 9–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; et al. Long noncoding RNAs: fine-tuners hidden in the cancer signaling network. Cell Death Discovery 2021, 7(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badowski, C.; He, B.; Garmire, L.X. Blood-derived lncRNAs as biomarkers for cancer diagnosis: the Good, the Bad and the Beauty. npj Precision Oncology 2022, 6(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotfi, E.; et al. Circulating miRNAs and lncRNAs serve as biomarkers for early colorectal cancer diagnosis. Pathology - Research and Practice 2024, 255, 155187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; et al. A Plasma Long Noncoding RNA Signature for Early Detection of Lung Cancer. Translational Oncology 2018, 11(5), 1225–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connerty, P.; Lock, R.B.; De Bock, C.E. Long Non-coding RNAs: Major Regulators of Cell Stress in Cancer. Frontiers in Oncology 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Medina, M.; et al. A Comprehensive Review of Long Non-Coding RNAs in the Cancer–Immunity Cycle: Mechanisms and Therapeutic Implications. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2025, 26(10), 4821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marei, H.E. Epigenetic regulators in cancer therapy and progression. NPJ Precision Oncology 2025, 9(1), 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovell, C.D.; Anguera, M.C. Long noncoding rnas that function in nutrition: lnc-ing nutritional cues to metabolic pathways. Annual Review of Nutrition 2022, 42, 251–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondo, Y.; Shinjo, K.; Katsushima, K. Long non-coding RNA s as an epigenetic regulator in human cancers. Cancer science 2017, 108(10), 1927–1933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mbemi, A.; et al. Impact of Gene–Environment Interactions on Cancer Development. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2020, 17(21), 8089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, M.; et al. Epigenetic regulation in cancer. MedComm 2024, 5(2), p. e495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Souza, A.P.d.; Marinho, V.; Marques, M.R. The fundamental role of nutrients for metabolic balance and epigenome integrity maintenance. Epigenomes 2025, 9(3), 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munteanu, C.; Schwartz, B. The relationship between nutrition and the immune system. Frontiers in Nutrition 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munteanu, C.; Schwartz, B. Interactions between Dietary Antioxidants, Dietary Fiber and the Gut Microbiome: Their Putative Role in Inflammation and Cancer. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2024, 25(15), 8250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; et al. Novel insights into lncRNAs as key regulators of post-translational modifications in cancer: mechanisms and therapeutic potential. Cellular Oncology 2025, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ekine-Afolabi, B.A.; et al. The Impact of Diet on the Involvement of Non-Coding RNAs, Extracellular Vesicles, and Gut Microbiome-Virome in Colorectal Cancer Initiation and Progression. Frontiers in Oncology 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, Z.T.; Xing, Z.; Tran, E.J. LncRNAs: Bridging environmental sensing and gene expression. RNA biology 2016, 13(12), 1189–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mierziak, J.; et al. Influence of the Bioactive Diet Components on the Gene Expression Regulation. Nutrients 2021, 13(11), 3673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, F.; Leisegang, M.S.; Brandes, R.P. LncRNAs Are Key Regulators of Transcription Factor-Mediated Endothelial Stress Responses. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2024, 25(17), 9726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petre, M.L.; et al. Precision nutrition: Is tailor-made dietary intervention a reality yet? (Review). Biomed Rep 2025, 22(5), 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Toro-Martín, J.; et al. Precision Nutrition: A Review of Personalized Nutritional Approaches for the Prevention and Management of Metabolic Syndrome. Nutrients 2017, 9(8), 913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heianza, Y.; Qi, L. Gene-Diet Interaction and Precision Nutrition in Obesity. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2017, 18(4), 787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; et al. Regulation of main ncRNAs by polyphenols: A novel anticancer therapeutic approach. Phytomedicine 2023, 120, 155072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishra, S.; et al. Long non-coding RNAs are emerging targets of phytochemicals for cancer and other chronic diseases. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences 2019, 76(10), 1947–1966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, Z.; et al. Therapeutic target genes and regulatory networks of gallic acid in cervical cancer. Frontiers in Genetics 2025, 15, 1508869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellitto, A.; et al. Regulation of Metabolic Reprogramming by Long Non-Coding RNAs in Cancer. Cancers 2021, 13(14), 3485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; et al. Revisiting cancer hallmarks: insights from the interplay between oxidative stress and non-coding RNAs. Molecular Biomedicine 2020, 1(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munteanu, C.; Mârza, S.M.; Papuc, I. The immunomodulatory effects of vitamins in cancer. Frontiers in Immunology 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakrim, S.; et al. Epi-nutrients for cancer prevention: Molecular mechanisms and emerging insights. Cell Biology and Toxicology 2025, 41(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, S.-R.; et al. Dietary modulation of epigenetics: Implications for cancer prevention and progression. Journal of Nutritional Oncology 2025, 10(1), 8–15. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, P.C.-T.; et al. LncRNA-dependent mechanisms of transforming growth factor-β: from tissue fibrosis to cancer progression. Non-coding RNA 2022, 8(3), 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradas-Juni, M.; et al. A MAFG-lncRNA axis links systemic nutrient abundance to hepatic glucose metabolism. Nature Communications 2020, 11(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sung, W.J.; Hong, J. Targeting lncRNAs of colorectal cancers with natural products. Frontiers in Pharmacology 2023, 13, 1050032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.-P.; et al. LncRNAs in tumor microenvironment: The potential target for cancer treatment with natural compounds and chemical drugs. Biochemical Pharmacology 2021, 193, 114802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lv, H.; et al. Modulation of long noncoding RNAs by polyphenols as a novel potential therapeutic approach in lung cancer: A comprehensive review. Phytotherapy Research 2024, 38(6), 3240–3267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidoni, C.; et al. Epigenetic targeting of autophagy for cancer prevention and treatment by natural compounds. Seminars in Cancer Biology 2020, 66, 34–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, H.; et al. Modulation of long noncoding RNAs by polyphenols as a novel potential therapeutic approach in lung cancer: A comprehensive review. Phytotherapy Research 2024, 38(6), 3240–3267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, H.; Badehnoosh, B. Synergistic strength: unleashing exercise and polyphenols against breast cancer. Cancer Cell International 2025, 25(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nocito, M.C.; et al. Antitumoral Activities of Curcumin and Recent Advances to ImProve Its Oral Bioavailability. Biomedicines 2021, 9(10), 1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; et al. Silence of long noncoding RNA PANDAR switches low-dose curcumin-induced senescence to apoptosis in colorectal cancer cells. OncoTargets and therapy 2017, 483–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; et al. Curcumin suppresses glioblastoma cell proliferation by p-AKT/mTOR pathway and increases the PTEN expression. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics 2020, 689, 108412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.; et al. Curcumin attenuates lncRNA H19-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition in tamoxifen-resistant breast cancer cells. Molecular Medicine Reports 2020, 23(1), 1–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, B.-S.; et al. Curcumin inhibits the growth and invasion of gastric cancer by regulating long noncoding RNA AC022424.2. World Journal of Gastrointestinal Oncology 2024, 16(4), 1437–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussein, M.A.; et al. MALAT-1 Is a Key Regulator of Epithelial–Mesenchymal Transition in Cancer: A Potential Therapeutic Target for Metastasis. Cancers 2024, 16(1), 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Xia, L. Resveratrol inhibits the proliferation, invasion, and migration, and induces the apoptosis of human gastric cancer cells through the MALAT1/miR-383-5p/DDIT4 signaling pathway. Journal of gastrointestinal oncology 2022, 13(3), p. 985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, N.E.; et al. The Long and the Short of It: NEAT1 and Cancer Cell Metabolism. Cancers 2022, 14(18), 4388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geng, W.; et al. Resveratrol inhibits proliferation, migration and invasion of multiple myeloma cells via NEAT1-mediated Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2018, 107, 484–494. [Google Scholar]

- Vallino, L.; et al. Modulation of non-coding RNAs by resveratrol in ovarian cancer cells: In silico analysis and literature review of the anti-cancer pathways involved. Journal of Traditional and Complementary Medicine 2020, 10(3), 217–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asemi, R.; et al. Modulation of long non-coding RNAs by resveratrol as a potential therapeutic approach in cancer: A comprehensive review. Pathology-Research and Practice 2023, 246, 154507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Z.; et al. Resveratrol suppresses the invasion and migration of human gastric cancer cells via inhibition of MALAT1-mediated epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition. Experimental and Therapeutic Medicine 2019, 17(3), 1569–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, P.; et al. NEAT1 upregulates EGCG-induced CTR1 to enhance cisplatin sensitivity in lung cancer cells. Oncotarget 2016, 7(28), p. 43337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakrim, S.; et al. Epi-nutrients for cancer prevention: Molecular mechanisms and emerging insights. Cell Biology and Toxicology 2025, 41(1), 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaie, F.; Mokhtari, M.J.; Kalani, M. Quercetin arrests in G2 phase, upregulates INXS LncRNA and downregulates UCA1 LncRNA in MCF-7 cells. International Journal of Molecular and Cellular Medicine 2022, 10(3), 208. [Google Scholar]

- Xiong, R.-G.; et al. Anticancer effects and mechanisms of berberine from medicinal herbs: an update review. Molecules 2022, 27(14), 4523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Z.; et al. Berberine induces mitochondrial-mediated apoptosis and protective autophagy in human malignant pleural mesothelioma NCI-H2452 cells. Oncology reports 2018, 40(6), 3603–3610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, C.-Y.; et al. Berberine alleviates the proliferation and metastasis of ESCA by promoting CCDC18-AS1 expression based on bioinformatics and in vitro experimental verification. Scientific Reports 2025, 15(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veeraraghavan, V.P.; et al. Effects of polyphenols on ncRNAs in cancer—An update. Clinical and Experimental Pharmacology and Physiology 2022, 49(6), 613–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wenzel, U.; et al. Dietary flavone is a potent apoptosis inducer in human colon carcinoma cells. Cancer research 2000, 60(14), 3823–3831. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Han, S.; et al. Targeting lncRNA/Wnt axis by flavonoids: A promising therapeutic approach for colorectal cancer. Phytotherapy Research 2022, 36(11), 4024–4040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jantan, I.; et al. Dietary polyphenols suppress chronic inflammation by modulation of multiple inflammation-associated cell signaling pathways. The Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry 2021, 93, 108634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Marín, D.; et al. LncRNAs driving feedback loops to boost drug resistance: sinuous pathways in cancer. Cancer Letters 2022, 543, 215763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frankhouser, D.E.; et al. Dietary omega-3 fatty acid intake impacts peripheral blood DNA methylation-anti-inflammatory effects and individual variability in a pilot study. The Journal of nutritional biochemistry 2022, 99, 108839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tait, S.; et al. Gene and lncRNA Profiling of ω3/ω6 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acid-Exposed Human Visceral Adipocytes Uncovers Different Responses in Healthy Lean, Obese and Colorectal Cancer-Affected Individuals. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2024, 25(6), 3357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simopoulos, A.P. The importance of the ratio of omega-6/omega-3 essential fatty acids. Biomed Pharmacother 2002, 56(8), 365–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiyasu, Y.; et al. EPA, DHA, and resolvin effects on cancer risk: The underexplored mechanisms. Prostaglandins & Other Lipid Mediators 2024, 174, 106854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; et al. H19 lncRNA alters DNA methylation genome wide by regulating S-adenosylhomocysteine hydrolase. Nature communications 2015, 6(1), 10221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.-S.; et al. Dietary supplementation with polyunsaturated fatty acid during pregnancy modulates DNA methylation at IGF2/H19 imprinted genes and growth of infants. Physiological genomics 2014, 46(23), 851–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raju, G.S.R.; et al. HOTAIR: a potential metastatic, drug-resistant and prognostic regulator of breast cancer. Molecular cancer 2023, 22(1), 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, P.; Li, X. Regulatory mechanism of lncRNAs in M1/M2 macrophages polarization in the diseases of different etiology. Frontiers in Immunology 2022, 13, 835932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valverde, A.; Naqvi, R.A.; Naqvi, A.R. Non-coding RNA LINC01010 regulates macrophage polarization and innate immune functions by modulating NFκB signaling pathway. Journal of cellular physiology 2024, 239(5), p. e31225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zong, Y.; et al. Decoding the regulatory roles of non-coding RNAs in cellular metabolism and disease. Molecular Therapy 2023, 31(6), 1562–1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez-Quiles, M.; Broekema, M.F.; Kalkhoven, E. PPARgamma in Metabolism, Immunity, and Cancer: Unified and Diverse Mechanisms of Action. Frontiers in Endocrinology 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keerthana, C.K.; et al. The role of AMPK in cancer metabolism and its impact on the immunomodulation of the tumor microenvironment. Frontiers in Immunology 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, X.; et al. Long noncoding RNA lnc-HC regulates PPARγ-mediated hepatic lipid metabolism through miR-130b-3p. Molecular therapy Nucleic acids 2019, 18, 954–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; et al. LncRNA NBR2 engages a metabolic checkpoint by regulating AMPK under energy stress. Nature cell biology 2016, 18(4), 431–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; et al. LncRNAs are involved in regulating ageing and age-related disease through the adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase signalling pathway. Genes & Diseases 2024, 11(5), p. 101042. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.-H.; et al. Omega-3 fatty acids-enriched fish oil activates AMPK/PGC-1α signaling and prevents obesity-related skeletal muscle wasting. Marine drugs 2019, 17(6), 380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navas, L.E.; Carnero, A. NAD+ metabolism, stemness, the immune response, and cancer. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy 2021, 6(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, N.; et al. NAD+ metabolism: pathophysiologic mechanisms and therapeutic potential. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy 2020, 5(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Covarrubias, A.J.; et al. NAD+ metabolism and its roles in cellular processes during ageing. Nature reviews Molecular cell biology 2021, 22(2), 119–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadhan, R.; Dhanasekaran, D.N. Regulation of Tumor Metabolome by Long Non-Coding RNAs. Journal of Molecular Signaling 2022, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podyacheva, E.; Toropova, Y. The Role of NAD+, SIRTs Interactions in Stimulating and Counteracting Carcinogenesis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2023, 24(9), 7925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Izzo, L.T.; Affronti, H.C.; Wellen, K.E. The bidirectional relationship between cancer epigenetics and metabolism. Annual review of cancer biology 2021, 5(1), 235–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.-J.; et al. The sirtuin family in health and disease. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy 2022, 7(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Z.; et al. Lnc RNA H19 functions as a competing endogenous RNA to regulate AQP 3 expression by sponging miR-874 in the intestinal barrier. FEBS letters 2016, 590(9), 1354–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; et al. Enzymes in the NAD+ salvage pathway regulate SIRT1 activity at target gene promoters. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2009, 284(30), 20408–20417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; et al. A review of current evidence about lncRNA MEG3: a tumor suppressor in multiple cancers. Frontiers in cell and developmental biology 2022, 10, 997633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yaku, K.; et al. NAD Metabolism in Cancer Therapeutics. Frontiers in Oncology 2018, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.-J.; et al. The lncRNA UCA1 promotes proliferation, migration, immune escape and inhibits apoptosis in gastric cancer by sponging anti-tumor miRNAs. Molecular cancer 2019, 18(1), 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; et al. LncRNA UCA1 in anti-cancer drug resistance. Oncotarget 2017, 8(38), 64638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazarlou, F.; et al. Tracing vitamins on the long non-coding lane of the transcriptome: vitamin regulation of LncRNAs. Genes & nutrition 2024, 19(1), 5. [Google Scholar]

- Laspata, N.; Muoio, D.; Fouquerel, E. Multifaceted Role of PARP1 in Maintaining Genome Stability Through Its Binding to Alternative DNA Structures. Journal of Molecular Biology 2024, 436(1), 168207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, K.; et al. lncRNA EGFR-AS1 promotes DNA damage repair by enhancing PARP1-mediated PARylation. Journal of Cell Biology 2026, 225(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; et al. LINP1 facilitates DNA damage repair through non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) pathway and subsequently decreases the sensitivity of cervical cancer cells to ionizing radiation. Cell Cycle 2018, 17(4), 439–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surjana, D.; Halliday, G.M.; Damian, D.L. Role of nicotinamide in DNA damage, mutagenesis, and DNA repair. Journal of nucleic acids 2010, 2010(1), 157591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyon, P.; et al. B Vitamins and One-Carbon Metabolism: Implications in Human Health and Disease. Nutrients 2020, 12(9). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munteanu, C.; Schwartz, B.; Vitamins, B. Vitamins, Glucoronolactone and the Immune System: Bioavailability, Doses and Efficiency. Nutrients 2023, 16(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; et al. Overexpression of cytosolic long noncoding RNA cytb protects against pressure-overload-induced heart failure via sponging microRNA-103-3p. Molecular Therapy Nucleic Acids 2022, 27, 1127–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; et al. Long non-coding RNA NORAD serves as a promoter of oncogenesis and inhibits ferroptosis via miR-144-3p-mTOR-ferritinophagy axis in cancer. European Journal of Medical Research 2025, 30(1), 704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; et al. Systematic analysis of the role of SLC52A2 in multiple human cancers. Cancer Cell Int 2022, 22(1), p. 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, W.; et al. Pyridoxine 5'-phosphate oxidase is correlated with human breast invasive ductal carcinoma development. Aging (Albany NY) 2019, 11(7), 2151–2176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; et al. Interactome analysis reveals that lncRNA HULC promotes aerobic glycolysis through LDHA and PKM2. Nature communications 2020, 11(1), 3162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bitaraf, A.; et al. MALAT1 as a molecular driver of tumor progression, immune evasion, and resistance to therapy. Molecular Cancer 2025, 24(1), 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munteanu, C.; et al. E, K, B5, B6, and B9 vitamins and their specific immunological effects evaluated by flow cytometry. Front Med (Lausanne) 2022, 9, 1089476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel, Vitamin D Metabolism, Mechanism of Action, and Clinical Applications. Chemistry & Biology 2014, 21(3), 319–329.

- Bikle, D.D. Vitamin D regulation of and by long non coding RNAs. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology 2021, 532, 111317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, S.; et al. Long Non-coding RNA MEG3 Activated by Vitamin D Suppresses Glycolysis in Colorectal Cancer via Promoting c-Myc Degradation. Frontiers in Oncology 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Y.; et al. MEG3 activated by vitamin D inhibits colorectal cancer cells proliferation and migration via regulating clusterin. EBioMedicine 2018, 30, 148–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; et al. The emerging roles of LINC00511 in breast cancer development and therapy. Frontiers in Oncology 2024, 14, 1429262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P. Influence of Foods and Nutrition on the Gut Microbiome and Implications for Intestinal Health. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2022, 23(17), 9588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garvey, M. Intestinal Dysbiosis: Microbial Imbalance Impacts on Colorectal Cancer Initiation, Progression and Disease Mitigation. Biomedicines 2024, 12(4), 740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garavaglia, B.; et al. The Anti-Inflammatory, Immunomodulatory, and Pro-Autophagy Activities of Probiotics for Colorectal Cancer Prevention and Treatment: A Narrative Review. Biomedicines 2025, 13(7), 1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; et al. A lncRNA from an inflammatory bowel disease risk locus maintains intestinal host-commensal homeostasis. Cell Research 2023, 33(5), 372–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, S.; et al. Effects of Long Non-Coding RNAs Induced by the Gut Microbiome on Regulating the Development of Colorectal Cancer. Cancers 2022, 14(23), 5813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, X.; et al. Long non-coding RNA EVADR induced by Fusobacterium nucleatum infection promotes colorectal cancer metastasis. Cell Reports 2022, 40(3), p. 111127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; et al. Fusobacterium nucleatum promotes colorectal cancer metastasis by modulating KRT7-AS/KRT7. Gut Microbes 2020, 11(3), 511–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorbani, E.; et al. Role of lactobacillus strains in the management of colorectal cancer: An overview of recent advances. Nutrition 2022, 103-104, 111828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallino, L.; et al. Cell-free Lactiplantibacillus plantarum OC01 supernatant suppresses IL-6-induced proliferation and invasion of human colorectal cancer cells: Effect on β-Catenin degradation and induction of autophagy. Journal of Traditional and Complementary Medicine 2023, 13(2), 193–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garavaglia, B.; et al. Butyrate Inhibits Colorectal Cancer Cell Proliferation through Autophagy Degradation of β-Catenin Regardless of APC and β-Catenin Mutational Status. Biomedicines 2022, 10(5), 1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; et al. LncRNA lncLy6C induced by microbiota metabolite butyrate promotes differentiation of Ly6Chigh to Ly6Cint/neg macrophages through lncLy6C/C/EBPβ/Nr4A1 axis. Cell Discovery 2020, 6(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Wei, L. Analysis of long Non-Coding RNA and mRNA expression in Clostridium butyricum-Induced apoptosis in SW480 colon cancer cells. Gene 2025, 940, 149208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khodaii, Z.; et al. Novel targets in rectal cancer by considering lncRNA–miRNA–mRNA network in response to Lactobacillus acidophilus consumption: a randomized clinical trial. Scientific Reports 2022, 12(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, R.; et al. A critical review on the relevance, essentiality, and analytical techniques of trace elements in human cancer. Metallomics 2025, 17(2). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayman, M.P. Selenium and human health. Lancet 2012, 379(9822), 1256–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendellaa, M.; et al. Roles of zinc in cancers: From altered metabolism to therapeutic applications. Int J Cancer 2024, 154(1), 7–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildiz, A.; Kaya, Y.; Tanriverdi, O. Effect of the Interaction Between Selenium and Zinc on DNA Repair in Association With Cancer Prevention. J Cancer Prev 2019, 24(3), 146–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lammi, M.J.; Qu, C. Selenium-Related Transcriptional Regulation of Gene Expression. Int J Mol Sci 2018, 19(9). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, E. Zinc deficiency, DNA damage and cancer risk. J Nutr Biochem 2004, 15(10), 572–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angelone, T.; et al. Expanding the frontiers of guardian antioxidant selenoproteins in cardiovascular pathophysiology. Antioxidants & Redox Signaling 2024, 40(7-9), 369–432. [Google Scholar]

- Stolwijk, J.M.; et al. Understanding the Redox Biology of Selenium in the Search of Targeted Cancer Therapies. Antioxidants (Basel) 2020, 9(5). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, H.; et al. Sodium Selenite Regulates the Proliferation and Apoptosis of Gastric Cancer Cells by Suppressing the Expression of LncRNA HOXB-AS1. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2022, 2022, 6356583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamaliyan, Z.; Clarke, T.L. Zinc finger proteins: guardians of genome stability. Front Cell Dev Biol 2024, 12, 1448789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; et al. Systems biology analysis of long non-coding RNAs and targets to identify key modules and biomarkers in breast cancer. Discov Oncol 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitra, R.; Adams, C.M.; Eischen, C.M. Systematic lncRNA mapping to genome-wide co-essential modules uncovers cancer dependency on uncharacterized lncRNAs. Elife 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Salido-Guadarrama, I.; Romero-Cordoba, S.L.; Rueda-Zarazua, B. Multi-Omics Mining of lncRNAs with Biological and Clinical Relevance in Cancer. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24(23). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; et al. Machine learning combined with multi-omics to identify immune-related LncRNA signature as biomarkers for predicting breast cancer prognosis. Sci Rep 2025, 15(1), 23863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, G.; Chen, D. Unveiling Long Non-coding RNA Networks from Single-Cell Omics Data Through Artificial Intelligence. Methods Mol Biol 2025, 2883, 257–279. [Google Scholar]

- Mercatelli, D.; et al. Gene regulatory network inference resources: A practical overview. Biochim Biophys Acta Gene Regul Mech 2020, 1863(6), 194430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le, K.; et al. Gene and lncRNA co-expression network analysis reveals novel ceRNA network for triple-negative breast cancer. Sci Rep 2019, 9(1), 15122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qu, C.; et al. The landscape of immune checkpoint-related long non-coding RNAs core regulatory circuitry reveals implications for immunoregulation and immunotherapy responses. Commun Biol 2024, 7(1), 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadhan, R.; et al. Decoding lysophosphatidic acid signaling in physiology and disease: mapping the multimodal and multinodal signaling networks. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2025, 10(1), p. 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benso, A.; Politano, G. Artificial intelligence and machine learning heuristics for discovery of ncRNAs. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci 2025, 214, 145–162. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y.; Lee, M. Deep Learning Approaches for lncRNA-Mediated Mechanisms: A Comprehensive Review of Recent Developments. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24(12). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Gonzalo-Calvo, D.; et al. Machine learning for catalysing the integration of noncoding RNA in research and clinical practice. EBioMedicine 2024, 106, 105247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; et al. Identification of Accessible Hepatic Gene Signatures for Interindividual Variations in Nutrigenomic Response to Dietary Supplementation of Omega-3 Fatty Acids. Cells 2021, 10(2). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, L.; et al. Liquid biopsy in cancer current: status, challenges and future prospects. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2024, 9(1), 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maleki Dana, P.; et al. The role of polyphenols in overcoming cancer drug resistance: a comprehensive review. Cellular & Molecular Biology Letters 2022, 27(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong, T.T.; et al. Plant-Derived Antioxidants as Modulators of Redox Signaling and Epigenetic Reprogramming in Cancer. Cells 2025, 14(24), 1948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saghafi, T.; et al. Phytochemicals as Modulators of Long Non-Coding RNAs and Inhibitors of Cancer-Related Carbonic Anhydrases. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2019, 20(12), 2939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazurek, M.; et al. Plasma Circulating lncRNAs: MALAT1 and NEAT1 as Biomarkers of Radiation-Induced Adverse Effects in Laryngeal Cancer Patients. Diagnostics 2025, 15(6), 676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allam-Ndoul, B.; et al. Effect of n-3 fatty acids on the expression of inflammatory genes in THP-1 macrophages. Lipids in Health and Disease 2016, 15(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; et al. The Roles of H19 in Regulating Inflammation and Aging. Frontiers in Immunology 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; et al. Modulation of lncRNA H19 enhances resveratrol-inhibited cancer cell proliferation and migration by regulating endoplasmic reticulum stress. Journal of Cellular and Molecular Medicine 2022, 26(8), 2205–2217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garavaglia, B.; et al. Probiotic-Derived Metabolites from Lactiplantibacillus plantarum OC01 Reprogram Tumor-Associated Macrophages to an Inflammatory Anti-Tumoral Phenotype: Impact on Colorectal Cancer Cell Proliferation and Migration. Biomedicines 2025, 13(2), 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, K.; et al. Resolvin D1 and D2 inhibit tumour growth and inflammation via modulating macrophage polarization. Journal of Cellular and Molecular Medicine 2020, 24(14), 8045–8056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, P.; et al. Effect of Dietary Omega-3 Fatty Acids on Tumor-Associated Macrophages and Prostate Cancer Progression. The Prostate 2016, 76(14), 1293–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westheim, A.J.F.; et al. Fatty Acids as a Tool to Boost Cancer Immunotherapy Efficacy. Frontiers in Nutrition 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; et al. Long Noncoding RNA GAS5 Regulates Macrophage Polarization and Diabetic Wound Healing. Journal of Investigative Dermatology 2020, 140(8), 1629–1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chini, A.; et al. Novel long non-coding RNAs associated with inflammation and macrophage activation in human. Scientific Reports 2023, 13(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; et al. LncRNA NBR2 engages a metabolic checkpoint by regulating AMPK under energy stress. Nature Cell Biology 2016, 18(4), 431–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; et al. Long non-coding RNA UCA1 promotes glycolysis by upregulating hexokinase 2 through the mTOR–STAT3/microRNA143 pathway. Cancer Science 2014, 105(8), 951–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myong, S.; Nguyen, A.Q.; Challa, S. Biological Functions and Therapeutic Potential of NAD+ Metabolism in Gynecological Cancers. Cancers 2024, 16(17), 3085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobral, A.F.; et al. Unveiling the Therapeutic Potential of Folate-Dependent One-Carbon Metabolism in Cancer and Neurodegeneration. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2024, 25(17), 9339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; et al. H19 lncRNA alters DNA methylation genome wide by regulating S-adenosylhomocysteine hydrolase. Nature Communications 2015, 6(1), 10221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjbar, M.; et al. Mutual interaction of lncRNAs and epigenetics: focusing on cancer. Egyptian Journal of Medical Human Genetics 2023, 24(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, K.; et al. Identification of MYC and STAT3 for early diagnosis based on the long noncoding RNA-mRNA network and bioinformatics in colorectal cancer. Frontiers in Immunology 2025, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo, J.; Stueve, T.R.; Marconett, C.N. Intersecting transcriptomic profiling technologies and long non-coding RNA function in lung adenocarcinoma: discovery, mechanisms, and therapeutic applications. Oncotarget 2017, 8(46), 81538–81557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trujano-Camacho, S.; et al. Vitamin D as an Epigenetic Regulator: A Hypothetical Mechanism for Cancer Prevention via Inhibition of Oncogenic lncRNA HOTAIR. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2025, 26(16), 7997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).