Submitted:

30 December 2025

Posted:

31 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Established Models for Studying Nuclear Dynamics During Quiescence

2.1. Unicellular Eukaryotic Models

2.2. Multicellular Models

3. What Drives Transcriptional Reprogramming in Quiescent Cells?

3.1. Transcriptional Reprogramming During Metabolic Transitions in Yeast

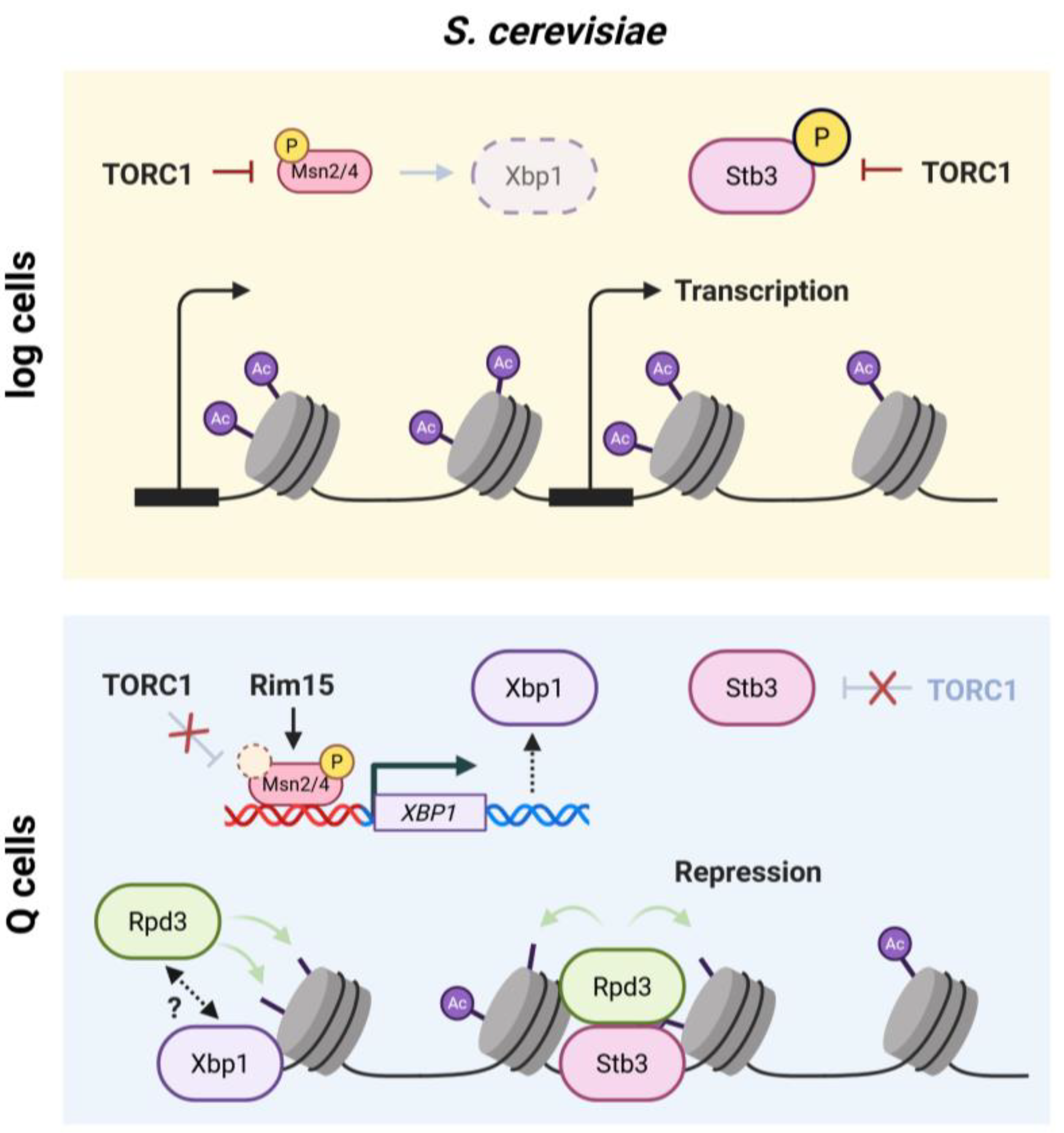

3.2. Transcription Factor Dynamics Orchestrate Chromatin Remodeling

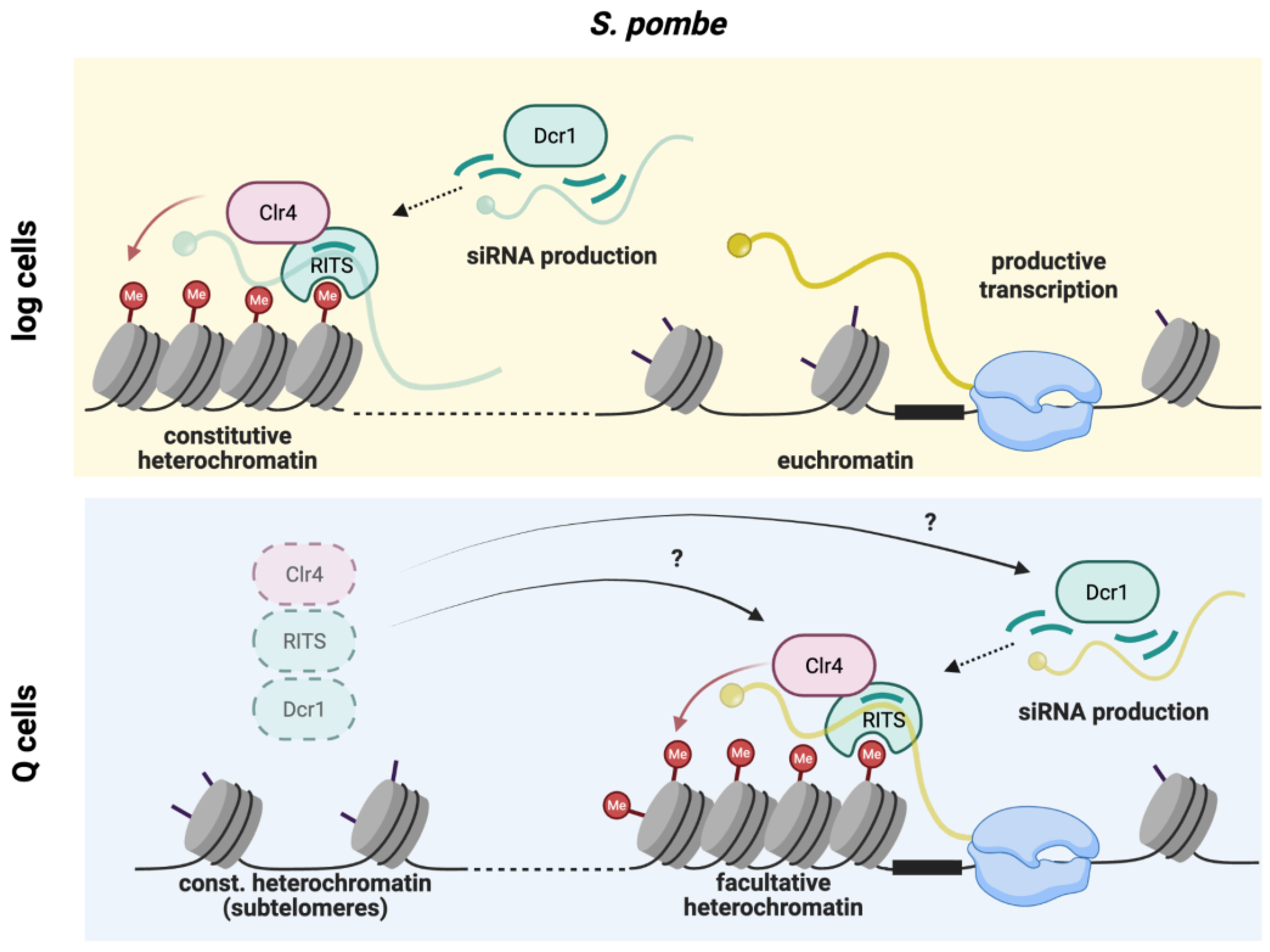

3.3. Establishment of Silent Chromatin Through Repressive Epigenetic Modifications

3.4. Persistence and Redistribution of Active Histone Methylation Marks

3.5. Epigenetic Reprogramming of Metabolic Genes Through Altered Histone Dynamics and Nucleosome Remodeling

4. Post-Transcriptional Mechanisms Shape Quiescence-Specific Gene Expression

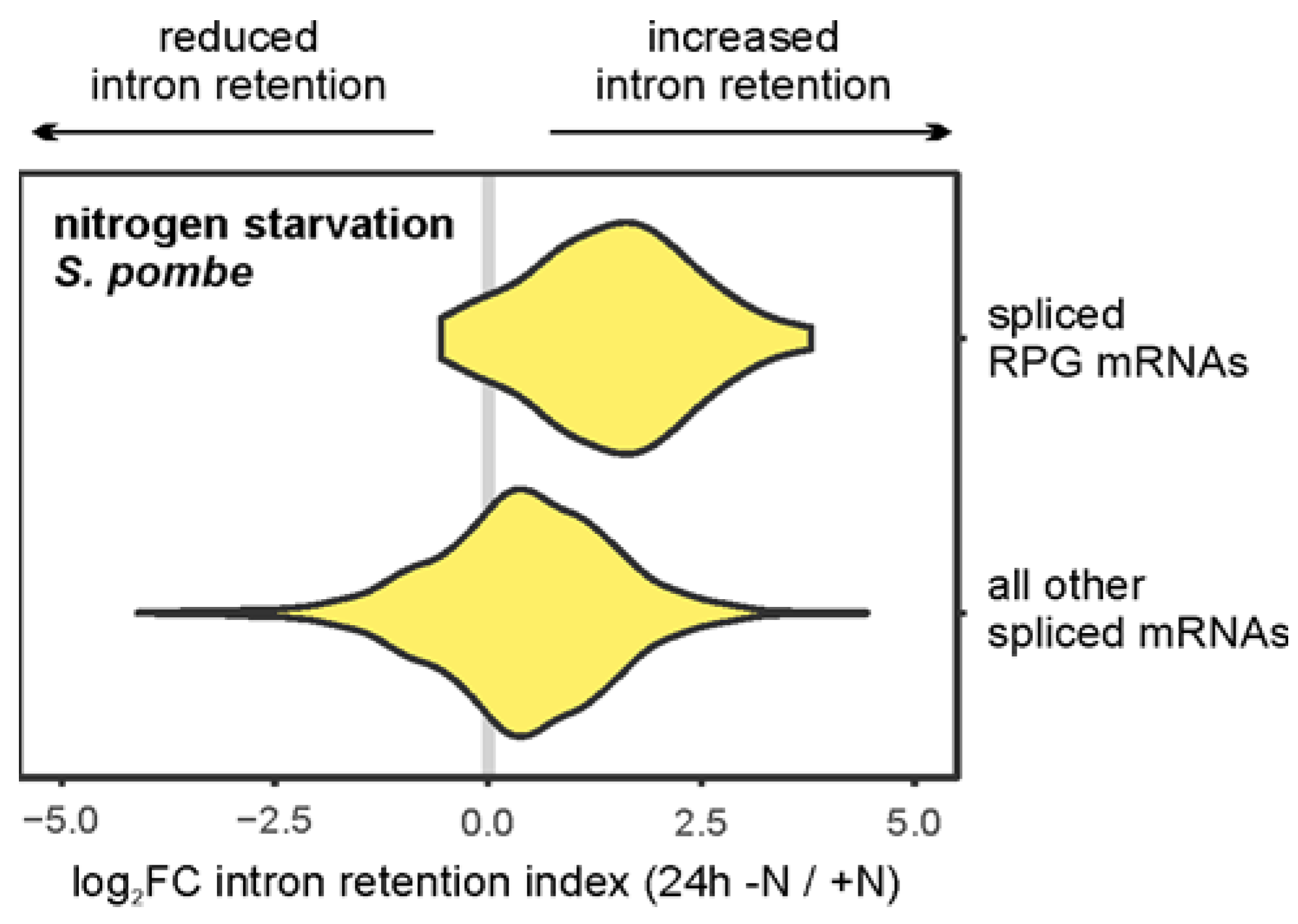

4.1. Intron Retention Regulates Protein Biogenesis Genes

4.2. 3’-UTR Lengthening Expands the Repertoire of Post-Transcriptional Regulation

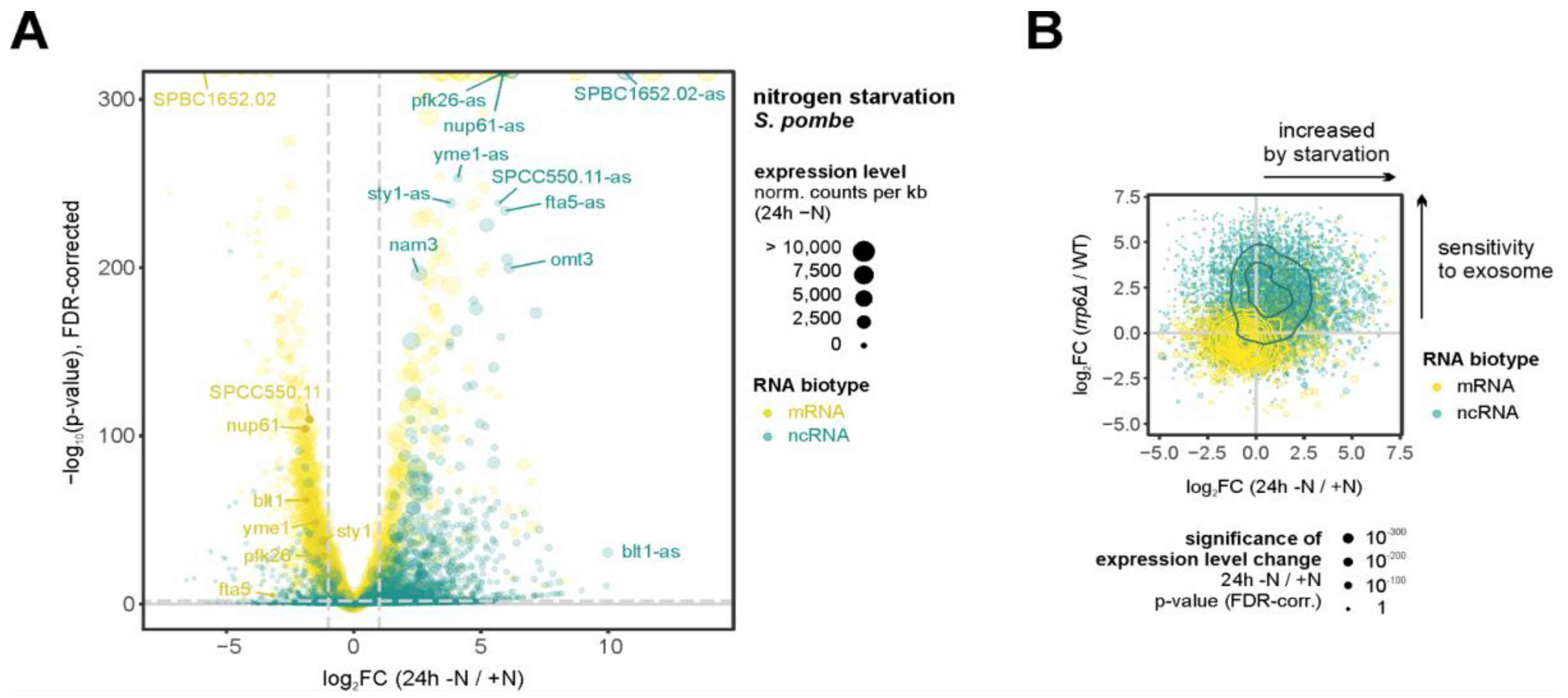

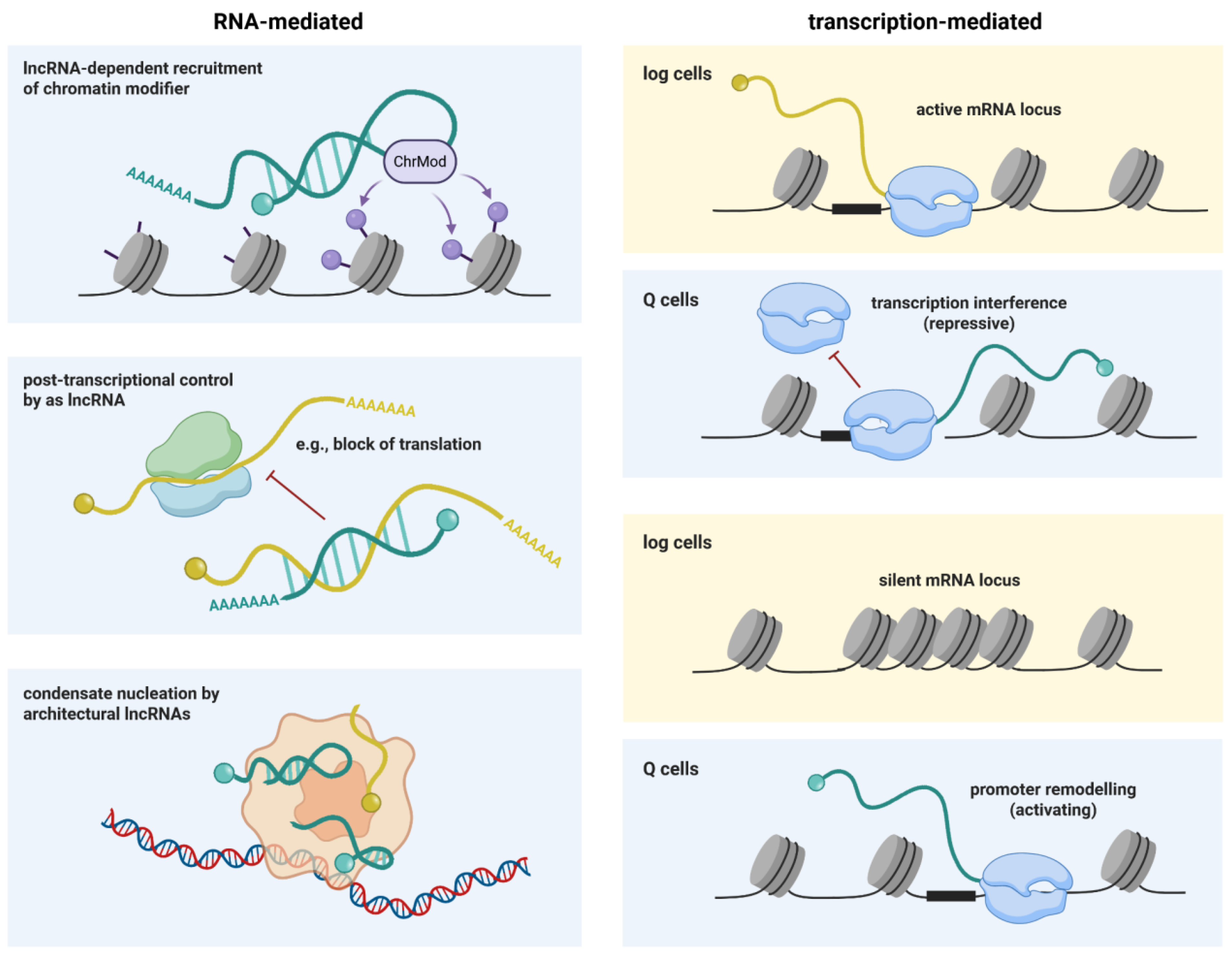

4.3. Regulatory Non-Coding RNAs Facilitate Rewiring of Gene Expression

5. Reorganisation of Nuclear Structures and Genome Architecture

5.1. Biosynthetic Condensates

5.2. Changes in Local and Higher-Order Chromatin Structures

5.3. Telomere Reorganization

5.4. Dynamic Relocalization of Stress-Induced Gene Clusters

6. Quiescence: Quo Vadis?

Acknowledgments

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- O'Farrell, P.H. Quiescence: early evolutionary origins and universality do not imply uniformity. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 2011, 366, 3498–3507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breeden, L.L.; Tsukiyama, T. Quiescence in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2022, 56, 253–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, J.V.; Petsko, G.A.; Johnston, G.C.; Ringe, D.; Singer, R.A.; Werner-Washburne, M. “Sleeping Beauty”: Quiescence in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2004, 68, 187–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laribee, R.N.; Weisman, R. Nuclear Functions of TOR: Impact on Transcription and the Epigenome. Genes 2020, 11, 641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulut-Karslioglu, A.; Biechele, S.; Jin, H.; Macrae, T.A.; Hejna, M.; Gertsenstein, M.; Song, J.S.; Ramalho-Santos, M. Inhibition of mTOR induces a paused pluripotent state. Nature 2016, 540, 119–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Virgilio, C. The essence of yeast quiescence. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2012, 36, 306–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laporte, D.; Sagot, I. Quiescence Multiverse. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sagot, I.; Laporte, D. The cell biology of quiescent yeast – a diversity of individual scenarios. J. Cell Sci. 2019, 132, jcs213025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacquel, B.; Aspert, T.; Laporte, D.; Sagot, I.; Charvin, G. Monitoring single-cell dynamics of entry into quiescence during an unperturbed life cycle. eLife 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medina-Menéndez, C.; Tirado-Melendro, P.; Li, L.; Rodríguez-Martín, P.; la Peña, E.M.-D.; Díaz-García, M.; Valdés-Bescós, M.; López-Sansegundo, R.; Morales, A.V. Sox5 controls the establishment of quiescence in neural stem cells during postnatal development. PLOS Biol. 2025, 23, e3002654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, B.; Wang, X.; Jiang, L.; Xu, J.; Zohar, Y.; Yao, G. Extracellular Fluid Flow Induces Shallow Quiescence Through Physical and Biochemical Cues. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 792719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwon, J.S.; Everetts, N.J.; Wang, X.; Wang, W.; Della Croce, K.; Xing, J.; Yao, G. Controlling Depth of Cellular Quiescence by an Rb-E2F Network Switch. Cell Rep. 2017, 20, 3223–3235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, N.; Occean, J.R.; Melters, D.P.; Shi, C.; Wang, L.; Stransky, S.; Doyle, M.E.; Cui, C.-Y.; Delannoy, M.; Fan, J.; et al. A hyper-quiescent chromatin state formed during aging is reversed by regeneration. Mol. Cell 2023, 83, 1659–1676.e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajiki, K.; Hatanaka, M.; Nakamura, T.; Takeda, K.; Shimanuki, M.; Yoshida, T.; Hanyu, Y.; Hayashi, T.; Nakaseko, Y.; Yanagida, M. Genetic control of cellular quiescence in S. pombe. J. Cell Sci. 2009, 122, 1418–1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sideri, T.; Rallis, C.; A Bitton, D.; Lages, B.M.; Suo, F.; Rodríguez-López, M.; Du, L.-L.; Bähler, J. Parallel Profiling of Fission Yeast Deletion Mutants for Proliferation and for Lifespan During Long-Term Quiescence. G3 Genes|Genomes|Genetics 2015, 5, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanagida, M. Cellular quiescence: are controlling genes conserved? Trends Cell Biol. 2009, 19, 705–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahedi, Y.; Durand-Dubief, M.; Ekwall, K. High-Throughput Flow Cytometry Combined with Genetic Analysis Brings New Insights into the Understanding of Chromatin Regulation of Cellular Quiescence. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 9022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutherford, K.M.; Lera-Ramírez, M.; Wood, V. PomBase: a Global Core Biodata Resource—growth, collaboration, and sustainability. Genetics 2024, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Gresham, D. Cellular quiescence in budding yeast. Yeast 2020, 38, 12–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marek, A.; Tomala, K.; Wloch-Salamon, D. Ecological History Shapes Transcriptome Variation in Quiescent Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Morree, A.; Rando, T.A. Regulation of Adult Stem Cell Quiescence and Its Functions in the Maintenance of Tissue Integrity. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2023, 24, 334–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gangloff, S.; Arcangioli, B. DNA repair and mutations during quiescence in yeast. FEMS Yeast Res. 2017, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, G.C.; Pringle, J.R.; Hartwell, L.H. Coordination of Growth with Cell Division in the Yeast Saccharomyces Cerevisiae. Exp. Cell Res. 1977, 105, 79–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lillie, S.H.; Pringle, J.R. Reserve carbohydrate metabolism in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: responses to nutrient limitation. J. Bacteriol. 1980, 143, 1384–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Werner-Washburne, M.; Braun, E.; Johnston, G.C.; A Singer, R. Stationary phase in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microbiol. Rev. 1993, 57, 383–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, C.; BütTner, S.; Aragon, A.D.; Thomas, J.A.; Meirelles, O.; Jaetao, J.E.; Benn, D.; Ruby, S.W.; Veenhuis, M.; Madeo, F.; et al. Isolation of quiescent and nonquiescent cells from yeast stationary-phase cultures. J. Cell Biol. 2006, 174, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Ren, Q.; Zhang, Z. Chromosome or chromatin condensation leads to meiosis or apoptosis in stationary yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) cells. FEMS Yeast Res. 2006, 6, 1254–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opalek, M.; Tutaj, H.; Pirog, A.; Smug, B.J.; Rutkowska, J.; Wloch-Salamon, D. A Systematic Review on Quiescent State Research Approaches in S. cerevisiae. Cells 2023, 12, 1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Miles, S.; Melville, Z.; Prasad, A.; Bradley, G.; Breeden, L.L. Key events during the transition from rapid growth to quiescence in budding yeast require posttranscriptional regulators. Mol. Biol. Cell 2013, 24, 3697–3709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, G.S.; Joe, R.M.; Roy, S.; Meirelles, O.; Allen, C.P.; Wilson, M.R.; Tapia, P.H.; Manzanilla, E.E.; Dodson, A.E.; Chakraborty, S.; et al. The proteomics of quiescent and nonquiescent cell differentiation in yeast stationary-phase cultures. Mol. Biol. Cell 2011, 22, 988–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, S.; Li, L.; Davison, J.; Breeden, L.L. Xbp1 Directs Global Repression of Budding Yeast Transcription during the Transition to Quiescence and Is Important for the Longevity and Reversibility of the Quiescent State. PLOS Genet. 2013, 9, e1003854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, S.; Lee, C.; Breeden, L. BY4741 cannot enter quiescence from rich medium. MicroPubl. Biol. 2023, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, S.S.; Tanaka, Y.; Samejima, I.; Tanaka, K.; Yanagida, M. A nitrogen starvation-induced dormant G0 state in fission yeast: the establishment from uncommitted G1 state and its delay for return to proliferation. J. Cell Sci. 1996, 109, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roche, B.; Arcangioli, B.; Martienssen, R. Transcriptional reprogramming in cellular quiescence. RNA Biol. 2017, 14, 843–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubbard, E.J.A.; Schedl, T. Biology of the Caenorhabditis elegans Germline Stem Cell System. Genetics 2019, 213, 1145–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rashid, S.; Wong, C.; Roy, R. Developmental plasticity and the response to nutrient stress in Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev. Biol. 2021, 475, 265–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gujar, M.R.; Wang, H. Signaling mechanisms in the reactivation of quiescent neural stem cells in Drosophila. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2025, 96, 102566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheung, T.H.; Rando, T.A. Molecular regulation of stem cell quiescence. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2013, 14, 329–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trumpp, A.; Essers, M.; Wilson, A. Awakening dormant haematopoietic stem cells. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2010, 10, 201–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Höfer, T.; Busch, K.; Klapproth, K.; Rodewald, H.-R. Fate Mapping and Quantitation of Hematopoiesis In Vivo. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2016, 34, 449–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, A.; Laurenti, E.; Oser, G.; van der Wath, R.C.; Blanco-Bose, W.; Jaworski, M.; Offner, S.; Dunant, C.F.; Eshkind, L.; Bockamp, E.; et al. Hematopoietic Stem Cells Reversibly Switch from Dormancy to Self-Renewal during Homeostasis and Repair. Cell 2008, 135, 1118–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Busch, K.; Klapproth, K.; Barile, M.; Flossdorf, M.; Holland-Letz, T.; Schlenner, S.M.; Reth, M.; Höfer, T.; Rodewald, H.-R. Fundamental properties of unperturbed haematopoiesis from stem cells in vivo. Nature 2015, 518, 542–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kucinski, I.; Campos, J.; Barile, M.; Severi, F.; Bohin, N.; Moreira, P.N.; Allen, L.; Lawson, H.; Haltalli, M.L.; Kinston, S.J.; et al. A time- and single-cell-resolved model of murine bone marrow hematopoiesis. Cell Stem Cell 2024, 31, 244–259.e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Weijden, V.A.; Bulut-Karslioglu, A. Molecular Regulation of Paused Pluripotency in Early Mammalian Embryos and Stem Cells. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 708318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Renfree, M.B.; Fenelon, J.C. The enigma of embryonic diapause. Development 2017, 144, 3199–3210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, S.M.; Evans, M. Non-surgical method for the induction of delayed implantation and recovery of viable blastocysts in rats and mice by the use of tamoxifen and Depo-Provera. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 1999, 52, 29–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paria, B.C.; Huet-Hudson, Y.M.; Dey, S.K. Blastocyst's state of activity determines the "window" of implantation in the receptive mouse uterus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1993, 90, 10159–10162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- zgüldez, H.Ö.; Bulut-Karslioğlu, A. Dormancy, Quiescence, and Diapause: Savings Accounts for Life. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2024, 40, 25–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyer, D.P.; Khoei, H.H.; van der Weijden, V.A.; Kagawa, H.; Pradhan, S.J.; Novatchkova, M.; McCarthy, A.; Rayon, T.; Simon, C.S.; Dunkel, I.; et al. mTOR activity paces human blastocyst stage developmental progression. Cell 2024, 187, 6566–6583.e22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boroviak, T.; Loos, R.; Lombard, P.; Okahara, J.; Behr, R.; Sasaki, E.; Nichols, J.; Smith, A.; Bertone, P. Lineage-Specific Profiling Delineates the Emergence and Progression of Naive Pluripotency in Mammalian Embryogenesis. Dev. Cell 2015, 35, 366–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scognamiglio, R.; Cabezas-Wallscheid, N.; Thier, M.C.; Altamura, S.; Reyes, A.; Prendergast, Á.M.; Baumgärtner, D.; Carnevalli, L.S.; Atzberger, A.; Haas, S.; et al. Myc Depletion Induces a Pluripotent Dormant State Mimicking Diapause. Cell 2016, 164, 668–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKnight, J.N.; Boerma, J.W.; Breeden, L.L.; Tsukiyama, T. Global Promoter Targeting of a Conserved Lysine Deacetylase for Transcriptional Shutoff during Quiescence Entry. Mol. Cell 2015, 59, 732–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, C.P.; Hillyer, C.; Hokamp, K.; Fitzpatrick, D.J.; Konstantinov, N.K.; Welty, J.S.; Ness, S.A.; Werner-Washburne, M.; Fleming, A.B.; Osley, M.A. Distinct histone methylation and transcription profiles are established during the development of cellular quiescence in yeast. BMC Genom. 2017, 18, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mews, P.; Zee, B.M.; Liu, S.; Donahue, G.; Garcia, B.A.; Berger, S.L. Histone Methylation Has Dynamics Distinct from Those of Histone Acetylation in Cell Cycle Reentry from Quiescence. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2014, 34, 3968–3980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marguerat, S.; Schmidt, A.; Codlin, S.; Chen, W.; Aebersold, R.; Bähler, J. Quantitative Analysis of Fission Yeast Transcriptomes and Proteomes in Proliferating and Quiescent Cells. Cell 2012, 151, 671–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenlaw, A.; Dell, R.; Tsukiyama, T. Initial acidic media promotes quiescence entry in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. 2024, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, M.B.; Laenen, G.; Loïodice, I.; Garnier, M.; Szachnowski, U.; Morillon, A.; Ruault, M.; Taddei, A. Intergenic accumulation of RNA polymerase II maintains the potential for swift transcriptional restart upon release from quiescence. Genome Res. 2025, 35, 2226–2239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radonjic, M.; Andrau, J.-C.; Lijnzaad, P.; Kemmeren, P.; Kockelkorn, T.T.; van Leenen, D.; van Berkum, N.L.; Holstege, F.C. Genome-Wide Analyses Reveal RNA Polymerase II Located Upstream of Genes Poised for Rapid Response upon S. cerevisiae Stationary Phase Exit. Mol. Cell 2005, 18, 171–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swygert, S.G.; Tsukiyama, T. Unraveling quiescence-specific repressive chromatin domains. Curr. Genet. 2019, 65, 1145–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aragon, A.D.; Rodriguez, A.L.; Meirelles, O.; Roy, S.; Davidson, G.S.; Tapia, P.H.; Allen, C.; Joe, R.; Benn, D.; Werner-Washburne, M. Characterization of Differentiated Quiescent and Nonquiescent Cells in Yeast Stationary-Phase Cultures. Mol. Biol. Cell 2008, 19, 1271–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, K.H.; Zhang, B.; Ramachandran, V.; Herman, P.K. Processing Body and Stress Granule Assembly Occur by Independent and Differentially Regulated Pathways inSaccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 2013, 193, 109–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, S.; Ekwall, K. Epigenome Mapping in Quiescent Cells Reveals a Key Role for H3K4me3 in Regulation of RNA Polymerase II Activity. Epigenomes 2024, 8, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joh, R.I.; Khanduja, J.S.; Calvo, I.A.; Mistry, M.; Palmieri, C.M.; Savol, A.J.; Sui, S.J.H.; Sadreyev, R.I.; Aryee, M.J.; Motamedi, M. Survival in Quiescence Requires the Euchromatic Deployment of Clr4/SUV39H by Argonaute-Associated Small RNAs. Mol. Cell 2016, 64, 1088–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zahedi, Y.; Zeng, S.; Ekwall, K. An essential role for the Ino80 chromatin remodeling complex in regulation of gene expression during cellular quiescence. Chromosom. Res. 2023, 31, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Westholm, J.O.; Nordberg, N.; Murén, E.; Ameur, A.; Komorowski, J.; Ronne, H. Combinatorial control of gene expression by the three yeast repressors Mig1, Mig2 and Mig3. BMC Genom. 2008, 9, 601–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treitel, M.A.; Kuchin, S.; Carlson, M. Snf1 Protein Kinase Regulates Phosphorylation of the Mig1 Repressor in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1998, 18, 6273–6280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Pastor, M.T.; Marchler, G.; Schüller, C.; Marchler-Bauer, A.; Ruis, H.; Estruch, F. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae zinc finger proteins Msn2p and Msn4p are required for transcriptional induction through the stress response element (STRE). EMBO J. 1996, 15, 2227–2235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santhanam, A.; Hartley, A.; DüvEl, K.; Broach, J.R.; Garrett, S. PP2A Phosphatase Activity Is Required for Stress and Tor Kinase Regulation of Yeast Stress Response Factor Msn2p. Eukaryot. Cell 2004, 3, 1261–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mai, B.; Breeden, L. Xbp1, a Stress-Induced Transcriptional Repressor of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae Swi4/Mbp1 Family. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1997, 17, 6491–6501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, A.; French, S.L.; Tekotte, H.; Yerlikaya, S.; Stahl, M.; Perepelkina, M.P.; Tyers, M.; Rougemont, J.; Beyer, A.L.; Loewith, R. Sch9 regulates ribosome biogenesis via Stb3, Dot6 and Tod6 and the histone deacetylase complex RPD3L. EMBO J. 2011, 30, 3052–3064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirai, H.; Ohta, K. Comparative Research: Regulatory Mechanisms of Ribosomal Gene Transcription in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonitto, K.; Sarathy, K.; Atai, K.; Mitra, M.; Coller, H.A. Is There a Histone Code for Cellular Quiescence? Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, R.; Chen, H.; Gao, C.; Xue, P.; Yang, F.; Han, J.-D.J.; Zhou, B.; Chen, Y.-G. Xbp1-mediated histone H4 deacetylation contributes to DNA double-strand break repair in yeast. Cell Res. 2011, 21, 1619–1633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nirello, V.D.; de Paula, D.R.; Araújo, N.V.; Varga-Weisz, P.D. Does chromatin function as a metabolite reservoir? Trends Biochem. Sci. 2022, 47, 732–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friis, R.M.N.; Wu, B.P.; Reinke, S.N.; Hockman, D.J.; Sykes, B.D.; Schultz, M.C. A glycolytic burst drives glucose induction of global histone acetylation by picNuA4 and SAGA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009, 37, 3969–3980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- E Cucinotta, C.; Dell, R.H.; Braceros, K.C.; Tsukiyama, T. RSC primes the quiescent genome for hypertranscription upon cell-cycle re-entry. eLife 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allshire, R.C.; Madhani, H.D. Ten principles of heterochromatin formation and function. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2017, 19, 229–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zofall, M.; Yamanaka, S.; Reyes-Turcu, F.E.; Zhang, K.; Rubin, C.; Grewal, S.I.S. RNA Elimination Machinery Targeting Meiotic mRNAs Promotes Facultative Heterochromatin Formation. Science 2012, 335, 96–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roche, B.; Arcangioli, B.; Martienssen, R.A. RNA interference is essential for cellular quiescence. Science 2016, 354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oya, E.; Durand-Dubief, M.; Cohen, A.; Maksimov, V.; Schurra, C.; Nakayama, J.-I.; Weisman, R.; Arcangioli, B.; Ekwall, K. Leo1 is essential for the dynamic regulation of heterochromatin and gene expression during cellular quiescence. Epigenetics Chromatin 2019, 12, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, X.; Feng, W.; Imhof, A.; Grummt, I.; Zhou, Y. Activation of RNA Polymerase I Transcription by Cockayne Syndrome Group B Protein and Histone Methyltransferase G9a. Mol. Cell 2007, 27, 585–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadeo, X.; Wang, J.; Kallgren, S.P.; Liu, J.; Reddy, B.D.; Qiao, F.; Jia, S. Elimination of shelterin components bypasses RNAi for pericentric heterochromatin assembly. Genes Dev. 2013, 27, 2489–2499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrales, R.R.; Forn, M.; Georgescu, P.R.; Sarkadi, Z.; Braun, S. Control of heterochromatin localization and silencing by the nuclear membrane protein Lem2. Genes Dev. 2016, 30, 133–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, A.; Sarkadi, Z.; Mazumder, A.; Saada, A.A.; van Emden, T.; Capella, M.; Fekete, G.; Sreechakram, V.N.S.; Al-Sady, B.; A E Lambert, S.; et al. A systematic quantitative approach comprehensively defines domain-specific functional pathways linked to Schizosaccharomyces pombe heterochromatin regulation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 52, 13665–13689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.; Cheung, T.H.; Charville, G.W.; Hurgo, B.M.C.; Leavitt, T.; Shih, J.; Brunet, A.; Rando, T.A. Chromatin Modifications as Determinants of Muscle Stem Cell Quiescence and Chronological Aging. Cell Rep. 2013, 4, 189–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margueron, R.; Li, G.; Sarma, K.; Blais, A.; Zavadil, J.; Woodcock, C.L.; Dynlacht, B.D.; Reinberg, D. Ezh1 and Ezh2 Maintain Repressive Chromatin through Different Mechanisms. Mol. Cell 2008, 32, 503–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evertts, A.G.; Manning, A.L.; Wang, X.; Dyson, N.J.; Garcia, B.A.; Coller, H.A. H4K20 methylation regulates quiescence and chromatin compaction. Mol. Biol. Cell 2013, 24, 3025–3037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bierhoff, H.; Dammert, M.A.; Brocks, D.; Dambacher, S.; Schotta, G.; Grummt, I. Quiescence-Induced LncRNAs Trigger H4K20 Trimethylation and Transcriptional Silencing. Mol. Cell 2014, 54, 675–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boonsanay, V.; Zhang, T.; Georgieva, A.; Kostin, S.; Qi, H.; Yuan, X.; Zhou, Y.; Braun, T. Regulation of Skeletal Muscle Stem Cell Quiescence by Suv4-20h1-Dependent Facultative Heterochromatin Formation. Cell Stem Cell 2016, 18, 229–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramponi, V.; Richart, L.; Kovatcheva, M.; Attolini, C.S.-O.; Capellades, J.; Lord, A.E.; Yanes, O.; Ficz, G.; Serrano, M. H4K20me3-Mediated Repression of Inflammatory Genes Is a Characteristic and Targetable Vulnerability of Persister Cancer Cells. Cancer Res. 2024, 85, 32–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Fan, R.; Chen, F.; Govindasamy, N.; Brinkmann, H.; Stehling, M.; Adams, R.H.; Jeong, H.-W.; Bedzhov, I. Analyzing embryo dormancy at single-cell resolution reveals dynamic transcriptional responses and activation of integrin-Yap/Taz prosurvival signaling. Cell Stem Cell 2024, 31, 1262–1279.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, Z.; Wang, B.; Wang, S.; Wu, W.; Wang, Q.; Chen, Y.; Kong, S.; Lu, J.; Tang, Z.; Ran, H.; et al. Integral Proteomic Analysis of Blastocysts Reveals Key Molecular Machinery Governing Embryonic Diapause and Reactivation for Implantation in Mice. Biol. Reprod. 2014, 90, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, A.M.; Wang, Y.; Mathieu, J.; Margaretha, L.; Song, C.; Jones, D.C.; Cavanaugh, C.; Miklas, J.W.; Mahen, E.; Showalter, M.R.; et al. Metabolic Control over mTOR-Dependent Diapause-like State. Dev. Cell 2020, 52, 236–250.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Weijden, V.A.; Bulut-Karslioğlu, A. Embryos Burn Fat in Standby. Trends Cell Biol. 2024, 34, 700–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stötzel, M.; Cheng, C.-Y.; Iiik, I.A.; Kumar, A.S.; Omgba, P.A.; van der Weijden, V.A.; Zhang, Y.; Vingron, M.; Meissner, A.; Aktaş, T.; et al. TET activity safeguards pluripotency throughout embryonic dormancy. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2024, 31, 1625–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, R.; Kim, Y.S.; Wu, J.; Chen, R.; Zeuschner, D.; Mildner, K.; Adachi, K.; Wu, G.; Galatidou, S.; Li, J.; et al. Wnt/Beta-catenin/Esrrb signalling controls the tissue-scale reorganization and maintenance of the pluripotent lineage during murine embryonic diapause. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 5499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furlan, G.; Martin, S.B.; Cho, B.; McClymont, S.A.; Robertson, E.J.; Collignon, E.; Ramalho-Santos, M. Nodal/Smad2 Signaling Sustains Developmental Pausing by Repressing Pparg-Mediated Lipid Metabolism. bioRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajiki, K.; Tahara, Y.; Uehara, L.; Sasaki, T.; Pluskal, T.; Yanagida, M. Genetic regulation of mitotic competence in G 0 quiescent cells. Sci. Adv. 2018, 4, eaat5685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, L.; Prasad, P.; Ekwall, K.; Cohen, A.; Svensson, J.P. The Paf1 Complex Factors Leo1 and Paf1 Promote Local Histone Turnover to Modulate Chromatin States in Fission Yeast. EMBO Rep. 2015, 16, 1673–1687. [Google Scholar]

- Oya, T.; Tanaka, M.; Hayashi, A.; Yoshimura, Y.; Nakamura, R.; Arita, K.; Murakami, Y.; Nakayama, J. Characterization of the Swi6/ HP1 binding motif in its partner protein reveals the basis for the functional divergence of the HP1 family proteins in fission yeast. FASEB J. 2025, 39, e70387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, A.G.; Smith, C.W.J. Intron Retention as a Component of Regulated Gene Expression Programs. Hum. Genet. 2017, 136, 1043–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pleiss, J.A.; Whitworth, G.B.; Bergkessel, M.; Guthrie, C. Rapid, Transcript-Specific Changes in Splicing in Response to Environmental Stress. Mol. Cell 2007, 27, 928–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parenteau, J.; Tsang, J.; Downs, S.R.; Zhou, D.; Scott, M.S.; A Pleiss, J.; Elela, S.A. Cells resist starvation through a nutrient stress splice switch. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parenteau, J.; Maignon, L.; Berthoumieux, M.; Catala, M.; Gagnon, V.; Elela, S.A. Introns are mediators of cell response to starvation. Nature 2019, 565, 612–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, J.T.; Fink, G.R.; Bartel, D.P. Excised linear introns regulate growth in yeast. Nature 2019, 565, 606–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yue, L.; Wan, R.; Luan, S.; Zeng, W.; Cheung, T.H. Dek Modulates Global Intron Retention during Muscle Stem Cells Quiescence Exit. Dev. Cell 2020, 53, 661–676.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitra, M.; Johnson, E.L.; Swamy, V.S.; E Nersesian, L.; Corney, D.C.; Robinson, D.G.; Taylor, D.G.; Ambrus, A.M.; Jelinek, D.; Wang, W.; et al. Alternative polyadenylation factors link cell cycle to migration. Genome Biol. 2018, 19, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukačišin, M.; Espinosa-Cantú, A.; Bollenbach, T. Intron-mediated induction of phenotypic heterogeneity. Nature 2022, 605, 113–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilchert, C.; Wittmann, S.; Passoni, M.; Shah, S.; Granneman, S.; Vasiljeva, L. Regulation of mRNA Levels by Decay-Promoting Introns that Recruit the Exosome Specificity Factor Mmi1. Cell Rep. 2015, 13, 2504–2515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harigaya, Y.; Tanaka, H.; Yamanaka, S.; Tanaka, K.; Watanabe, Y.; Tsutsumi, C.; Chikashige, Y.; Hiraoka, Y.; Yamashita, A.; Yamamoto, M. Selective elimination of messenger RNA prevents an incidence of untimely meiosis. Nature 2006, 442, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandberg, R.; Neilson, J.R.; Sarma, A.; Sharp, P.A.; Burge, C.B. Proliferating Cells Express mRNAs with Shortened 3' Untranslated Regions and Fewer MicroRNA Target Sites. Science 2008, 320, 1643–1647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Z.; Lee, J.Y.; Pan, Z.; Jiang, B.; Tian, B. Progressive lengthening of 3′ untranslated regions of mRNAs by alternative polyadenylation during mouse embryonic development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2009, 106, 7028–7033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Hoque, M.; Larochelle, M.; Lemay, J.-F.; Yurko, N.; Manley, J.L.; Bachand, F.; Tian, B. Comparative Analysis of Alternative Polyadenylation in S. Cerevisiae and S. Pombe. Genome Res. 2017, 27, 1685–1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schlackow, M.; Marguerat, S.; Proudfoot, N.J.; Bähler, J.; Erban, R.; Gullerova, M. Genome-wide analysis of poly(A) site selection in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. RNA 2013, 19, 1617–1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaels, K.K.; Mostafa, S.M.; Capella, J.R.; Moore, C.L. Regulation of alternative polyadenylation in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae by histone H3K4 and H3K36 methyltransferases. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 48, 5407–5425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, B.; Manley, J.L. Alternative polyadenylation of mRNA precursors. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2016, 18, 18–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geisberg, J.V.; Moqtaderi, Z.; Struhl, K. Chromatin regulates alternative polyadenylation via the RNA polymerase II elongation rate. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2024, 121, e2405827121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, J.-W.; Zhang, W.; Yeh, H.-S.; De Jong, E.P.; Jun, S.; Kim, K.-H.; Bae, S.S.; Beckman, K.; Hwang, T.H.; Kim, K.-S.; et al. mRNA 3′-UTR shortening is a molecular signature of mTORC1 activation. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 7218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geisberg, J.V.; Moqtaderi, Z.; Struhl, K. Condition-specific 3′ mRNA isoform half-lives and stability elements in yeast. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2023, 120, e2301117120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwakawa, H.-O.; Tomari, Y. Life of RISC: Formation, action, and degradation of RNA-induced silencing complex. Mol. Cell 2022, 82, 30–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Han, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Chen, J.; Li, W. Role of hypoxia inducible factor-1 in cancer stem cells (Review). Mol. Med. Rep. 2020, 23, 1–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macias, S.; Cordiner, R.A.; Gautier, P.; Plass, M.; Cáceres, J.F. DGCR8 Acts as an Adaptor for the Exosome Complex to Degrade Double-Stranded Structured RNAs. Mol. Cell 2015, 60, 873–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, T.H.; Quach, N.L.; Charville, G.W.; Liu, L.; Park, L.; Edalati, A.; Yoo, B.; Hoang, P.; Rando, T.A. Maintenance of muscle stem-cell quiescence by microRNA-489. Nature 2012, 482, 524–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.-M.; Pang, R.T.K.; Cheong, A.W.Y.; Ng, E.H.Y.; Lao, K.; Lee, K.-F.; Yeung, W.S.B. Involvement of microRNA Lethal-7a in the Regulation of Embryo Implantation in Mice. PLOS ONE 2012, 7, e37039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Hussein, A.M.; Somasundaram, L.; Sankar, R.; Detraux, D.; Mathieu, J.; Ruohola-Baker, H. MicroRNAs Regulating Human and Mouse Naïve Pluripotency. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 5864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Medvid, R.; Melton, C.; Jaenisch, R.; Blelloch, R. DGCR8 is essential for microRNA biogenesis and silencing of embryonic stem cell self-renewal. Nat. Genet. 2007, 39, 380–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, W.M.; Cheng, R.R.; Niu, Z.R.; Chen, A.C.; Ma, M.Y.; Li, T.; Chiu, P.C.; Pang, R.T.; Lee, Y.L.; Ou, J.P.; et al. Let-7 derived from endometrial extracellular vesicles is an important inducer of embryonic diapause in mice. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eaaz7070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kilchert, C. RNA Exosomes and Their Cofactors. Methods Mol. Biol. 2020, 2062, 215–235. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.-N.; Wang, M.-Y.; Ruan, J.-W.; Lyu, Y.-J.; Weng, Y.-H.; Brindangnanam, P.; Coumar, M.S.; Chen, P.-S. A transcription-independent role for HIF-1α in modulating microprocessor assembly. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 52, 11806–11821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenlaw, A.C.; Alavattam, K.G.; Tsukiyama, T. Post-transcriptional regulation shapes the transcriptome of quiescent budding yeast. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 52, 1043–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atkinson, S.R.; Marguerat, S.; Bitton, D.A.; Rodríguez-López, M.; Rallis, C.; Lemay, J.-F.; Cotobal, C.; Malecki, M.; Smialowski, P.; Mata, J.; et al. Long noncoding RNA repertoire and targeting by nuclear exosome, cytoplasmic exonuclease, and RNAi in fission yeast. RNA 2018, 24, 1195–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birot, A.; Kus, K.; Priest, E.; Al Alwash, A.; Castello, A.; Mohammed, S.; Vasiljeva, L.; Kilchert, C. RNA-binding protein Mub1 and the nuclear RNA exosome act to fine-tune environmental stress response. Life Sci. Alliance 2021, 5, e202101111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.; Wittmann, S.; Kilchert, C.; Vasiljeva, L. lncRNA recruits RNAi and the exosome to dynamically regulate pho1 expression in response to phosphate levels in fission yeast. Genes Dev. 2014, 28, 231–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, P.; Wu, Q.; Fang, H.; Wang, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Cong, M.; Wang, T.; He, Y.; Ma, C.; et al. Long non-coding RNA NR2F1-AS1 induces breast cancer lung metastatic dormancy by regulating NR2F1 and ΔNp63. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 5233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anver, S.; Sumit, A.F.; Sun, X.-M.; Hatimy, A.; Thalassinos, K.; Marguerat, S.; Alic, N.; Bähler, J. Ageing-associated long non-coding RNA extends lifespan and reduces translation in non-dividing cells. Embo Rep. 2024, 25, 4921–4949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirose, T.; Fujiwara, N.; Ninomiya, K.; Yamamoto, T.; Nakagawa, S.; Yamazaki, T. Architectural RNAs: blueprints for functional membraneless organelle assembly. Trends Genet. 2025, 41, 919–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirose, T.; Ninomiya, K.; Nakagawa, S.; Yamazaki, T. A guide to membraneless organelles and their various roles in gene regulation. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2022, 24, 288–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, D.-Q.; Okamasa, K.; Katou, Y.; Oya, E.; Nakayama, J.-I.; Chikashige, Y.; Shirahige, K.; Haraguchi, T.; Hiraoka, Y. Chromosome-associated RNA–protein complexes promote pairing of homologous chromosomes during meiosis in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 5598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydin, E.; Schreiner, S.; Böhme, J.; Keil, B.; Weber, J.; Žunar, B.; Glatter, T.; Kilchert, C. DEAD-box ATPase Dbp2 is the key enzyme in an mRNP assembly checkpoint at the 3’-end of genes and involved in the recycling of cleavage factors. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 6829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuman, S. Transcriptional interference at tandem lncRNA and protein-coding genes: an emerging theme in regulation of cellular nutrient homeostasis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 48, 8243–8254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, L.A.C.; Mori, M.; Yasuda, Y.; Galipon, J. Functional Consequences of Shifting Transcript Boundaries in Glucose Starvation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2023, 43, 611–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishizawa, M.; Komai, T.; Katou, Y.; Shirahige, K.; Ito, T.; Toh-E, A. Nutrient-Regulated Antisense and Intragenic RNAs Modulate a Signal Transduction Pathway in Yeast. PLOS Biol. 2008, 6, 2817–2830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miki, A.; Galipon, J.; Sawai, S.; Inada, T.; Ohta, K. RNA decay systems enhance reciprocal switching of sense and antisense transcripts in response to glucose starvation. Genes Cells 2016, 21, 1276–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirota, K.; Miyoshi, T.; Kugou, K.; Hoffman, C.S.; Shibata, T.; Ohta, K. Stepwise chromatin remodelling by a cascade of transcription initiation of non-coding RNAs. Nature 2008, 456, 130–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oda, A.; Takemata, N.; Hirata, Y.; Miyoshi, T.; Suzuki, Y.; Sugano, S.; Ohta, K. Dynamic transition of transcription and chromatin landscape during fission yeast adaptation to glucose starvation. Genes Cells 2015, 20, 392–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guidi, M.; Ruault, M.; Marbouty, M.; Loïodice, I.; Cournac, A.; Billaudeau, C.; Hocher, A.; Mozziconacci, J.; Koszul, R.; Taddei, A. Spatial reorganization of telomeres in long-lived quiescent cells. Genome Biol. 2015, 16, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Z.Y.; ShujunCai; Paithankar, S.A.; Liu, T.; Nie, X.; Shi, J. LuGan(甘露) Macromolecular and cytological changes in fission yeast G0 nuclei. J. Cell Sci. 2025, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiku, V.; Jain, C.; Raz, Y.; Nakamura, S.; Heestand, B.; Liu, W.; Späth, M.; Suchiman, H.E.D.; Müller, R.-U.; Slagboom, P.E.; et al. Small nucleoli are a cellular hallmark of longevity. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 16083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, X.; Yao, Q.; Horvath, A.; Jiang, Z.; Zhao, J.; Fischer, T.; Sugiyama, T. The fission yeast ortholog of Coilin, Mug174, forms Cajal body-like nuclear condensates and is essential for cellular quiescence. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 52, 9174–9192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schilling, M.; Prusty, A.B.; Boysen, B.; Oppermann, F.S.; Riedel, Y.L.; Husedzinovic, A.; Rasouli, H.; König, A.; Ramanathan, P.; Reymann, J.; et al. TOR signaling regulates liquid phase separation of the SMN complex governing snRNP biogenesis. Cell Rep. 2021, 35, 109277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swygert, S.G.; Lin, D.; Portillo-Ledesma, S.; Lin, P.-Y.; Hunt, D.R.; Kao, C.-F.; Schlick, T.; Noble, W.S.; Tsukiyama, T. Local chromatin fiber folding represses transcription and loop extrusion in quiescent cells. eLife 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schäfer, G.; McEvoy, C.R.E.; Patterton, H.-G. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae linker histone Hho1p is essential for chromatin compaction in stationary phase and is displaced by transcription. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 14838–14843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rutledge, M.T.; Russo, M.; Belton, J.-M.; Dekker, J.; Broach, J.R. The yeast genome undergoes significant topological reorganization in quiescence. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, 8299–8313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laporte, D.; Courtout, F.; Tollis, S.; Sagot, I. QuiescentSaccharomyces cerevisiaeforms telomere hyperclusters at the nuclear membrane vicinity through a multifaceted mechanism involving Esc1, the Sir complex, and chromatin condensation. Mol. Biol. Cell 2016, 27, 1875–1884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swygert, S.G.; Kim, S.; Wu, X.; Fu, T.; Hsieh, T.-H.; Rando, O.J.; Eisenman, R.N.; Shendure, J.; McKnight, J.N.; Tsukiyama, T. Condensin-Dependent Chromatin Compaction Represses Transcription Globally during Quiescence. Mol. Cell 2019, 73, 533–546.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsieh, T.-H.S.; Weiner, A.; Lajoie, B.; Dekker, J.; Friedman, N.; Rando, O.J. Mapping Nucleosome Resolution Chromosome Folding in Yeast by Micro-C. Cell 2015, 162, 108–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruault, M.; Loïodice, I.; Keister, B.D.; Even, A.; Garnier, M.; Baquero-Pérez, M.; Waterman, D.; Haber, J.E.; Blagoev, K.B.; Scolari, V.F.; et al. Esc1-Mediated Anchoring Regulates Telomere Clustering in Response to Metabolic Changes. bioRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocampo, A.; Liu, J.; Schroeder, E.A.; Shadel, G.S.; Barrientos, A. Mitochondrial Respiratory Thresholds Regulate Yeast Chronological Life Span and its Extension by Caloric Restriction. Cell Metab. 2012, 16, 55–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faure, G.; Jézéquel, K.; Roisné-Hamelin, F.; Bitard-Feildel, T.; Lamiable, A.; Marcand, S.; Callebaut, I. Discovery and Evolution of New Domains in Yeast Heterochromatin Factor Sir4 and Its Partner Esc1. Genome Biol. Evol. 2019, 11, 572–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshpande, I.; Keusch, J.J.; Challa, K.; Iesmantavicius, V.; Gasser, S.M.; Gut, H. The Sir4 H- BRCT domain interacts with phospho-proteins to sequester and repress yeast heterochromatin. EMBO J. 2020, 39, e103976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hocher, A.; Taddei, A. Subtelomeres as Specialized Chromatin Domains. BioEssays 2020, 42, e1900205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funabiki, H.; Hagan, I.; Uzawa, S.; Yanagida, M. Cell cycle-dependent specific positioning and clustering of centromeres and telomeres in fission yeast. J. Cell Biol. 1993, 121, 961–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chikashige, Y.; Yamane, M.; Okamasa, K.; Tsutsumi, C.; Kojidani, T.; Sato, M.; Haraguchi, T.; Hiraoka, Y. Membrane proteins Bqt3 and -4 anchor telomeres to the nuclear envelope to ensure chromosomal bouquet formation. J. Cell Biol. 2009, 187, 413–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimi, H.; Masuda, H.; Jain, D.; Cooper, J.P. Distinct ‘safe zones’ at the nuclear envelope ensure robust replication of heterochromatic chromosome regions. eLife 2018, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, C.; Inoue, H.; Sun, W.; Takeshita, Y.; Huang, Y.; Xu, Y.; Kanoh, J.; Chen, Y. The Inner Nuclear Membrane Protein Bqt4 in Fission Yeast Contains a DNA-Binding Domain Essential for Telomere Association with the Nuclear Envelope. Structure 2019, 27, 335–343.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steglich, B.; Strålfors, A.; Khorosjutina, O.; Persson, J.; Smialowska, A.; Javerzat, J.-P.; Ekwall, K. The Fun30 Chromatin Remodeler Fft3 Controls Nuclear Organization and Chromatin Structure of Insulators and Subtelomeres in Fission Yeast. PLOS Genet. 2015, 11, e1005101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tange, Y.; Chikashige, Y.; Takahata, S.; Kawakami, K.; Higashi, M.; Mori, C.; Kojidani, T.; Hirano, Y.; Asakawa, H.; Murakami, Y.; et al. Inner nuclear membrane protein Lem2 augments heterochromatin formation in response to nutritional conditions. Genes Cells 2016, 21, 812–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maestroni, L.; Reyes, C.; Vaurs, M.; Gachet, Y.; Tournier, S.; Géli, V.; Coulon, S. Nuclear envelope attachment of telomeres limits TERRA and telomeric rearrangements in quiescent fission yeast cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 48, 3029–3041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maestroni, L.; Audry, J.; Matmati, S.; Arcangioli, B.; Géli, V.; Coulon, S. Eroded telomeres are rearranged in quiescent fission yeast cells through duplications of subtelomeric sequences. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 1684–1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weierich, C.; Brero, A.; Stein, S.; von Hase, J.; Cremer, C.; Cremer, T.; Solovei, I. Three-dimensional arrangements of centromeres and telomeres in nuclei of human and murine lymphocytes. Chromosom. Res. 2003, 11, 485–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennarun, G.; Picotto, J.; Bertrand, P. Close Ties between the Nuclear Envelope and Mammalian Telomeres: Give Me Shelter. Genes 2023, 14, 775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mata, J.; Lyne, R.; Burns, G.; Bähler, J. The transcriptional program of meiosis and sporulation in fission yeast. Nat. Genet. 2002, 32, 143–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alfredsson-Timmins, J.; Kristell, C.; Henningson, F.; Lyckman, S.; Bjerling, P. Reorganization of chromatin is an early response to nitrogen starvation in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Chromosoma 2008, 118, 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taddei, A.; Gasser, S.M. Structure and Function in the Budding Yeast Nucleus. Genetics 2012, 192, 107–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, S.; Barrales, R.R. Beyond Tethering and the LEM domain: MSCellaneous functions of the inner nuclear membrane Lem2. Nucleus 2016, 7, 523–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skribbe, M.; Soneson, C.; Stadler, M.B.; Schwaiger, M.; Sreechakram, V.N.S.; Iesmantavicius, V.; Hess, D.; Moreno, E.P.F.; Braun, S.; Seebacher, J.; et al. A comprehensive Schizosaccharomyces pombe atlas of physical transcription factor interactions with proteins and chromatin. Mol. Cell 2025, 85, 1426–1444.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Abbreviation | Definition | Explanation | Species context |

|---|---|---|---|

| G0 | G0 phase | Reversible cell-cycle arrest in which cells stop dividing but retain the ability to re-enter proliferation. | conserved |

| Q cells | Quiescent cells | Cells in a stable, non-proliferative state with reduced biosynthesis and extensive nuclear remodeling. | conserved |

| Diapause | Embryonic diapause | Reversible developmental arrest of the mammalian embryo, typically at the blastocyst stage. | metazoans (mammals) |

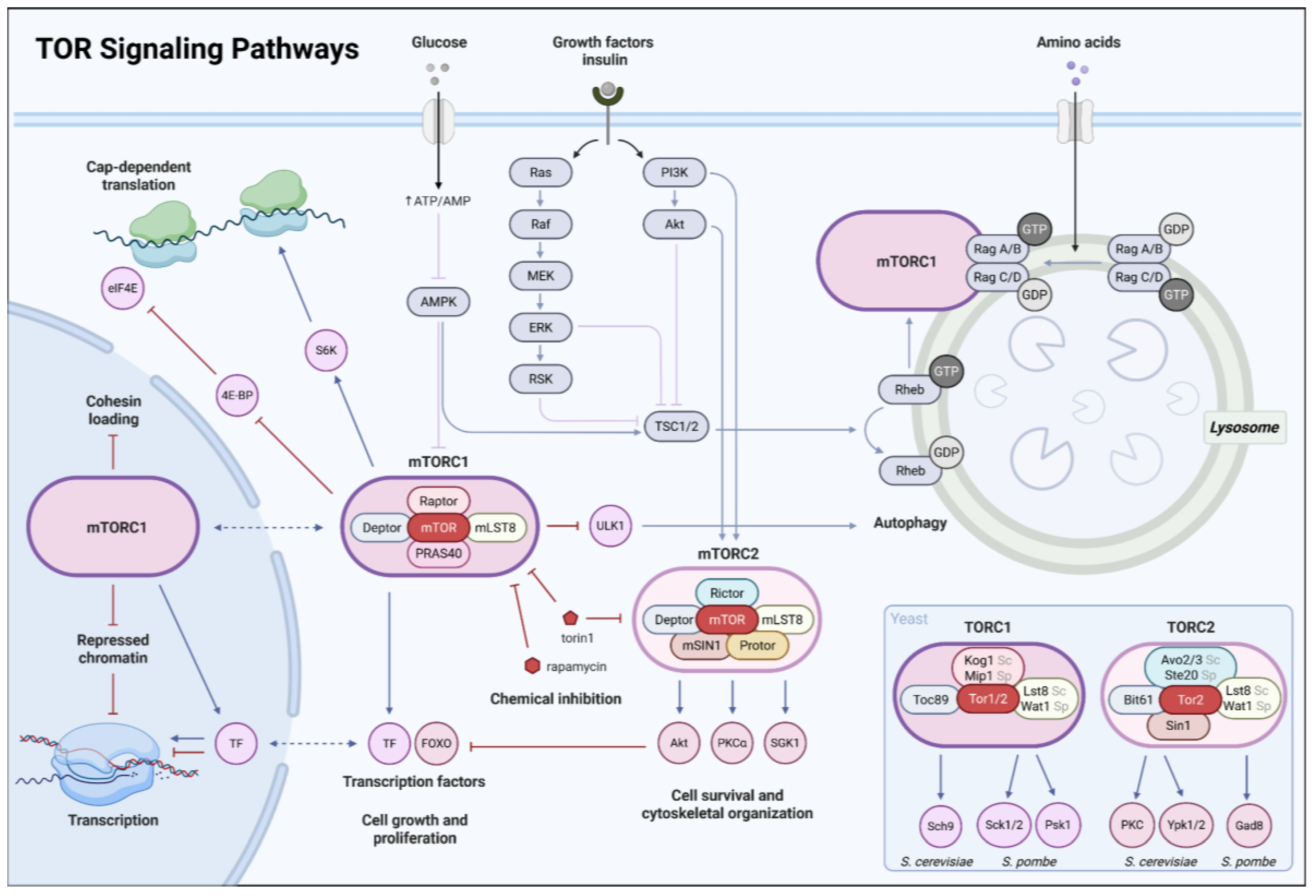

| TOR | Target of Rapamycin | Nutrient-sensing kinase pathway coordinating growth, metabolism, and quiescence. | yeast |

| mTOR | Mechanistic Target of Rapamycin | Metazoan TOR pathway integrating nutrient and growth-factor signaling to regulate dormancy and growth. | metazoans |

| TORC1 | TOR complex 1 | TOR-containing complex promoting ribosome biogenesis and translation; inhibited during quiescence. | conserved |

| TORC2 | TOR complex 2 | TOR-containing complex regulating stress responses and survival pathways. | conserved |

| PKA | Protein kinase A | cAMP-dependent kinase promoting growth-associated transcription and antagonizing quiescence. | conserved |

| DS | Diauxic shift | Metabolic transition in which yeast cells switch from fermentative growth on glucose to respiratory metabolism of alternative carbon sources after glucose depletion. | S. cerevisiae |

| RNAPII | RNA polymerase II | Enzyme transcribing mRNAs and many non-coding RNAs; redistributes during quiescence. | conserved |

| Pol I | RNA polymerase I | Enzyme transcribing ribosomal RNA genes at the rDNA locus; tightly linked to growth state. | conserved |

| RiBi | Ribosome biogenesis | Coordinate transcriptional program encoding ribosomal proteins, rDNA processing factors, and ribosome assembly component. | S. cerevisiae (conserved in eukaryotes) |

| RRPE | rRNA processing element | Cis-regulatory promoter motif enriched in ribosome biogenesis genes that mediates coordinated transcriptional repression via binding of Stb3. | S. cerevisiae |

| RP | Ribosomal proteins | Structural and functional components of ribosomes; their expression is tightly repressed during quiescence. | conserved |

| Stb3 | Sin3-binding protein 3 | Nutrient regulated transcriptional repressor of RiBi genes that recruit Rpd3 to promote chromatin compaction and biosynthetic shutdown | S. cerevisiae |

| Xbp1 | XhoI site- binding protein 1 | Stress-induced transcriptional repressor that binds promoter regions of growth-associated genes | S. cerevisiae |

| HDAC | Histone deacetylase | Enzymes removing acetyl groups from histones, promoting chromatin compaction and repression. | conserved |

| Rpd3 | Reduced potassium dependency 3 | Class I HDAC broadly retargeted to promoters during budding yeast quiescence. | S. cerevisiae |

| Set1C / COMPASS | Set1 complex | H3K4 methyltransferase complex depositing H3K4me3 at promoters. | conserved |

| SAGA | Spt-Ada-Gcn5 acetyltransferase complex | Transcriptional coactivator complex with histone acetyltransferase and deubiquitylation activities that promotes transcription initiation at stress- and growth-related genes. | conserved |

| H3K4me3 | H3 lysine 4 trimethylation | Active promoter mark selectively retained or redistributed during quiescence. | conserved |

| H3K36me3 | H3 lysine 36 trimethylation | Histone modification associated with transcription elongation and gene body marking, largely maintained during quiescence (in yeast). | conserved |

| Ino80C | Ino80 chromatin remodeling complex | ATP-dependent remodeler evicting H2A.Z and regulating transcription during quiescence. | conserved |

| H2A.Z | H2A.Z histone variant | Histone variant modulating promoter responsiveness and chromatin boundaries. | conserved |

| Hho1 | Histone H1 homolog | Linker histone contributing to chromatin compaction without enforcing full silencing. | S. cerevisiae |

| Pac1C | Polymerase-associated factor 1 complex | Transcription elongation complex that associates with RNAPII and regulates histone modifications linked to active transcription | conserved |

| Clr3 / Clr6 | Cryptic loci regulators 3/6 | HDACs contributing to heterochromatin formation and quiescence maintenance. | S. pombe |

| Clr4 | Cryptic loci regulators 4 | Histone H3K9 methyltransferase/Suvar 39h homolog, heterochromatin initiation and spreading. | S. pombe |

| H3K9me2/3 | H3 lysine 9 methylation (di-/trimethylation) |

Repressive histone mark defining constitutive and facultative heterochromatin. | conserved (absent in S. cerevisiae) |

| H3K27me3 | H3 lysine 27 trimethylation | Polycomb-associated repressive mark controlling facultative repression. | metazoans |

| H4K20me3 | H4 lysine 20 trimethylation | Deeply repressive mark associated with chromatin compaction and long-term arrest. | metazoans |

| PRC2 | Polycomb repressive complex 2 | Complex depositing H3K27me3 to mediate stable transcriptional repression. | metazoans |

| EZH1 | Enhancer of zeste homolog 1 | PRC2 catalytic subunit prevalent in non-proliferative and quiescent cells. | metazoans |

| EZH2 | Enhancer of zeste homolog 2 | PRC2 catalytic subunit associated with proliferation and activation. | metazoans |

| HP1 | Heterochromatin protein 1 | Chromodomain protein binding H3K9me and promoting heterochromatin spreading. | conserved (functional analogs in S. pombe) |

| RNAi | RNA interference | Small RNA–guided silencing pathway coupling transcripts to heterochromatin formation. | S. pombe, metazoans |

| Dcr1 | Dicer | RNase III enzyme producing siRNAs; also performs RNAi-independent roles in quiescence survival. | S. pombe |

| Ago1 | Argonaute 1 | Small-RNA effector protein targeting transcripts and chromatin. | S. pombe, metazoans |

| RITS | RNA-induced transcriptional silencing complex | RNAi effector complex linking siRNAs to chromatin-based repression. | S. pombe |

| lncRNA | Long non-coding RNA | >200-nt RNAs regulating chromatin, transcription, and nuclear organization. | conserved |

| asRNA | Antisense RNA | Non-coding RNA transcribed opposite a gene, often mediating transcriptional interference. | conserved |

| PAS | Polyadenylation site | RNA cleavage site determining 3′-UTR length and post-transcriptional regulation. | conserved |

| 3′-UTR | 3′ untranslated region | mRNA region controlling stability, localization, and translation efficiency. | conserved |

| CID | Chromosomal interaction domain | Local self-interacting chromatin unit detected by Hi-C. | yeast (conceptually conserved) |

| L-CID | Large chromosomal interaction domain | Larger chromatin domains that become more insulated during quiescence. | S. cerevisiae |

| Condensin | Condensin complex | SMC complex organizing higher-order chromosome structure via loop formation. | conserved |

| Cajal body | Cajal body | Nuclear condensate coordinating snRNA and snoRNA maturation with growth state. | metazoans, S. pombe |

| SMN | Survival of motor neurons protein | snRNP/sn(o)RNP assembly factor regulated by mTOR signaling. | metazoans |

| Myc | Myelocytomatosis oncogene family transcription factor | Global regulator of cell growth and proliferation, repressed during quiescence. | metazoans |

| Cellular process | Hallmarks/phenotype | Nuclear mechanism/factors |

|---|---|---|

| Cell cycle | Stable arrest with ability to re-enter proliferation | TOR1/mTOR2 inhibition, PKA1 signaling, Myc2 downregulation |

| Growth and metabolism | Reduced protein synthesis and metabolic activity | Repression of ribosomal- RNA and protein biogenesis1,2, translational control1,2, intron retention1,2 |

| Autophagy and survival | Increased autophagy and stress resistance | TOR1 inactivation, nutrient sensing pathways1,2 |

| Transcriptional regulation | Global transcriptional repression with selective gene activation | RNAPII redistribution)1,2 transcriptional repressors (Xbp11, Stb31), chromatin remodeling1,2 |

| Chromatin state | Increased chromatin compaction and heterochromatin formation | HDACs (Rpd31, Clr31, Clr61), histone methyltransferases (Clr41, PRC22) |

| Histone modifications | Global hypoacetylation, accumulation of repressive methylation marks | Histone deacetylation1,2, H3K91,2 / H3K272 / H4K202 methylation pathways |

| Genome organization | Nuclear and 3D genome reorganization | Condensin1,2, heterochromatin dynamics1,2, telomere clustering1, stress-induced gene cluster relocalization1 |

| RNA abundance | Strong reduction in total mRNA levesl | Reduced RNAP II initiation and elongation1, RNA decay modulation1,2 |

| RNA processing | Widespread intron retention | Splicing repression1,2, spliceosome retention1, TOR signaling1 |

| Post-transcriptional regulation | 3′-UTR lengthening, altered RNA stability | Polyadenylation site selection bias1, reduced cleavage1 |

| Transcript storage | Accumulation of RNAs in condensates | RNA-Protein phase separation1,2 |

| Non-coding RNA levels | Increased lncRNAs and other ncRNAs | Reduced nuclear exosome activity1,2, lncRNA-mediated recruitment of chromatin modifiers2 |

| Stress and metabolic genes |

Relative enrichment of stress-response and nutrient scavenging transcripts | Ino80C1, PafC1, histone turnover1, replication-independent chromatin remodeling1 |

| Re-proliferation capacity | Transcriptional reactivation upon nutrient readdition | Histone acetyltransferases (SAGA1, NuA41), TOR reactivation1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).