1. Introduction

Coffee is one of the most traded agricultural commodities worldwide, and demand has been on the rise, including high-quality specialty coffee as well [

1]. It is also a key economic activity in many tropical countries, as it is one of the world's most valuable agricultural products, according to the International Coffee Organization (ICO) [

2], both in terms of volume and value [

3]. Post-harvest processing, and especially drying, is critical to stabilizing the product, preventing microbial spoilage, and achieving the humidity range necessary for safe storage and desirable sensory quality [

4,

5]. In Colombia, the National Federation of Coffee Growers (FNC) of Colombia has regulated the quality conditions for the export of coffee and the penalties of the purchase price of bags based on their quality [

6,

7].

Traditional sun-drying is inexpensive but is highly climate-dependent, labor-intensive, and prone to inconsistency and contamination. Mechanical coffee dryers; As rotary drums, fixed-bed, and mixed-flow dryers, they were designed to reduce weather dependence, increase drying capacity and allow for more controllable process conditions [

4,

5]. In Colombia and other producing countries, mechanical dryers are now widely used at the agricultural and cooperative levels, often in combination with short pre-drying under ambient conditions [

5].

Despite this, mechanical coffee drying still faces several challenges: high specific energy consumption, heterogeneous moisture profiles within the dryer, and risks of quality degradation when temperature and airflow are not properly controlled [

8,

9,

10]. Numerous studies have proposed empirical and physics-based models for coffee drying, but their integration into online decision-making and control is still limited. At the level of small and medium-sized coffee growers, drying has been managed mostly by empirical methods, dependent on the intuition of the operator and subject to climate variability in the case of solar drying, or to severe energy inefficiencies in the case of mechanical drying [

5].

In the manufacturing and process industries, DT technology has been proposed as a core enabler of Industry 4.0, providing a dynamically updated virtual representation of a physical asset or process, synchronized using sensor data and used for simulation, prediction and optimization [

11,

12,

13]. In the food field, recent work has explored DTs for unit operations such as cooling, spray drying, freeze-drying and thermal processing [

14,

15,

16,

17,

18], and have specifically discussed its potential for drying operations [

20].

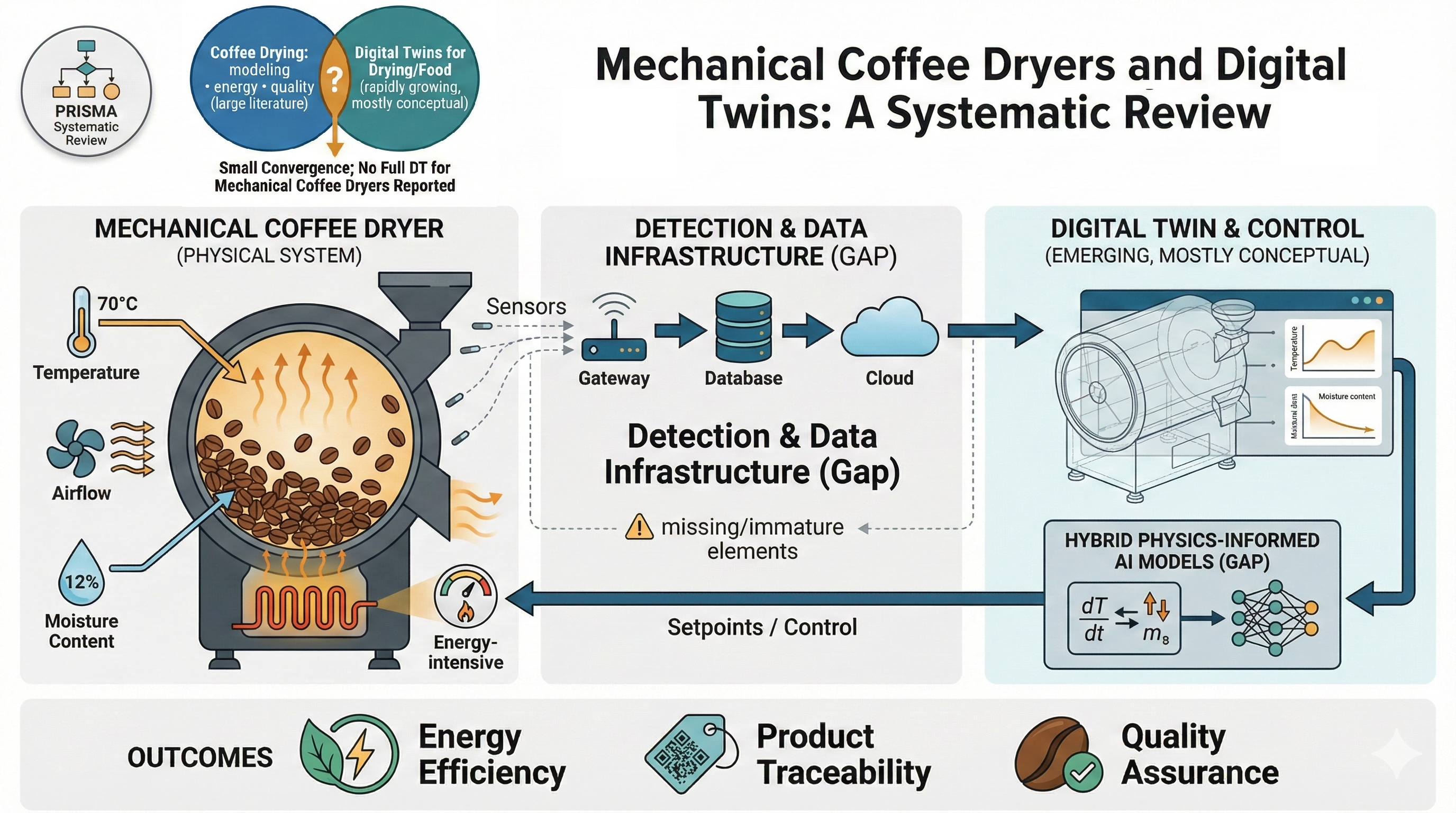

However, the intersection between mechanical coffee dryers and DT technology stays poorly mapped. To date, it was not possible to find a review that analyzes the state of technology and mechanical modeling of coffee drying, as well as the DT approaches applicable to coffee drying and analogous thermal bioprocesses.

The goals of this review are as follows:

Review recent research on mechanical coffee dryers, with an emphasis on modeling, monitoring, control, energy performance, and quality results.

Review DT approaches to drying processes and food-related thermal operations, including their architecture, modeling strategies, and sensing requirements.

Find gaps, limitations, and opportunities to develop DT-enabled mechanical coffee dryers.

This review was conducted following the proposal of the PRISMA methodology for the presentation of systematic reviews [

20].

2. State of the Art

Mechanical Coffee Dryers

Mechanical coffee drying has evolved from emergency solutions for peak harvests to become the standard to produce high-quality specialty and commercial coffees, where consistency is paramount. Understanding them correctly is critical to building your digital counterparts using DT technology. Although the principles of operation are like other bean dryers, coffee presents challenges due to the risk of defects and the importance of preserving aromatic compounds. Critical variables in coffee drying include drying air temperature, relative humidity, airflow rate, bed depth, residence time, bean initial moisture, and energy consumption. Quality-relevant responses include final moisture, moisture uniformity, bean color and physical defects, storage stability, and sensory metrics. Empirical evidence indicates that drying air temperature affects quality outcomes during storage, with higher temperatures potentially increasing undesirable changes [

21].

Mechanical coffee dryers can be classified into rotary drum, fixed bed (deep bed or silo type) configurations, trays, and continuous or mixed flow configurations [

4,

5]. Rotary drum dryers are often fed by biomass such as coffee husks blend the beans by rotation, promoting uniform exposure to hot air. Fixed bed dryers use aerated silos or perforated floors, where hot air passes through a static layer of coffee. Mixed flow and crossflow dryers resemble grain dryers and are suitable for large capacities [

5].

Several research have addressed the transfer of heat and mass within green coffee or on tracing paper, using finite element models combined with thin-layer drying kinetics [

8,

22,

23,

24]. On coffee quality, the effect of drying temperature and air conditions on cupping scores and volatile profiles has been evaluated, showing a fundamental role of slow and moderate temperature regimes in specialty coffees [

9].

Energy performance analyses of agricultural-scale mechanical dryers show significant opportunities for improvement through improved insulation, heat recovery and control of recirculating air, as well as the use of renewable fuels [

10].

The challenge is to optimize mechanical drying to achieve the speed and consistency of industrial processing while maintaining the delicate quality preservation of coffee beans. We believe that the solution must be in the digitalization of the process. Technologies like the Internet of Things , Big Data Analytics, and DTs provide tools to monitor, model, and control the drying environment with unprecedented precision [

25].

Digital Twin

A DT has been defined as a high-fidelity virtual representation of a physical asset, continuously updated from data collected by sensors and used to understand, predict and optimize the behavior of the physical asset throughout its life cycle [

11,

12,

13]. In industrial environments, DTs are implemented as cyber-physical systems that integrate:

Physical layer: Dryer hardware (heaters, fans, ducts, drum/bed), sensors, actuators, and the coffee mass as an evolving material.

Communication layer: IoT gateways, time-synchronized data pipelines, data quality controls, and persistent storage.

Model layer: Physics-based approaches rely on first-principles models of heat/mass transfer and diffusion-driven moisture migration, often using reduced-order formulations. Data-driven approaches learn patterns from data via ML regression/classification, including LSTM/sequence models for drying kinetics prediction. Hybrid approaches combine physics structure with learning to improve fidelity and robustness.

Analytics and services: optimization, predictive control, rule-based/fuzzy control, anomaly detection, and operator-facing guidance.

Visualization and user interaction: Control panels and decision support.

According to the literature consulted, DTs can be divided into different classification schemes according to the level of the general process they represent. Likewise, challenges in interoperability, standardization and data management have been highlighted [

11,

12,

13].

In the agri-food sector, recent studies have analyzed the applications of DT throughout food supply chains, highlighting opportunities for quality assurance, resource efficiency and traceability [

14,

15,

16,

17], emphasizing the coupling of sensor networks, process models, and decision support tools [

17].

In the context of coffee drying, a DT is not merely a static simulation used for equipment design. It is a dynamic, operative model that runs in parallel with the physical dryer. It ingests real-time data from sensors, processes this through models created to predict internal states that cannot be measured directly, and then autonomously adjusts the dryer's actuators to follow an optimal trajectory [

26].

DT in Feeding and Drying Processes

DTs in food process operations are the next step beyond conventional process models thanks to real-time data integration and lifecycle alignment [

14]. The authors in [

15,

16] conducted a review on food DTs and their implementation in the food industry, documenting early case studies in bakery, brewery, dairy processing, and logistics.

DTs are increasingly discussed in food processing. A review of DT applications and opportunities in food processing highlights emerging use cases in monitoring, predictive quality, and energy efficiency, but also notes the early-stage nature of DTs in many food unit operations due to data and validation constraints [

27]. In food processing, the Virtual Entity typically integrates multi-physics models capturing hydrodynamics, thermodynamics, and kinetics [

26].

Specific for drying in [

18] the development of a physics-based DT is shown to explore the trade-offs between product quality and energy consumption in fruit drying, while in [

19] The prospects for DTs in drying technology were published. Recently, the authors in [

28] proposed a DT model of an indirect solar dryer based on artificial neural networks and global sensitivity analysis. Typical control is often insufficient for drying processes due to thermal inertia, time delays, and the nonlinear nature of the process. Digital twins enable advanced control strategies.

Other research has implemented DT or DT-like frameworks in related thermal processes, such as microwave cooking [

29], autonomous thermal food processing [

30] and freeze-drying [

31]. These studies provide methodological blocks that can be transferred to coffee drying.

3. Methodology

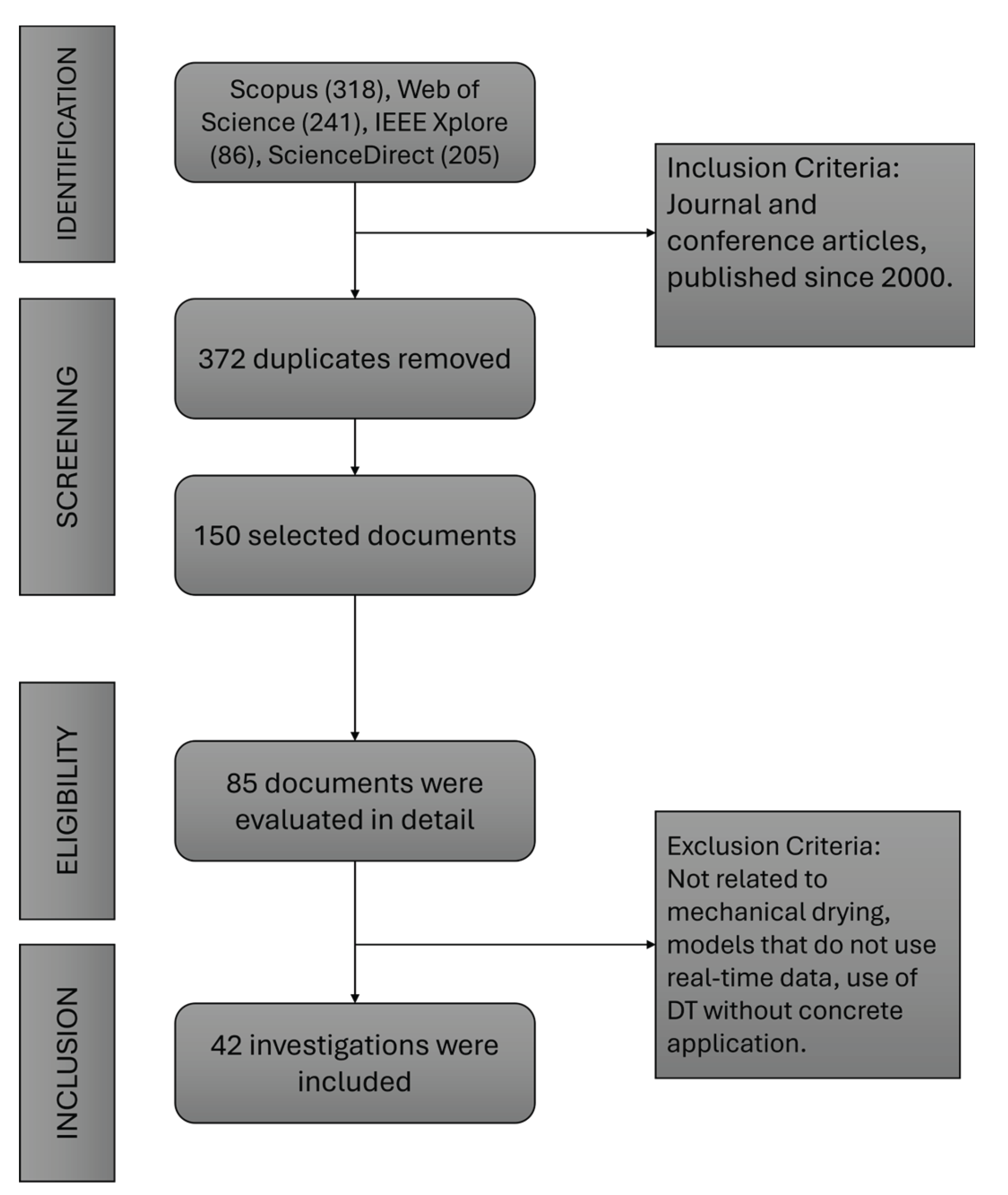

Based on the stages proposed in the PRISMA methodology, first, searches were carried out in the following databases: Scopus, Web of Science, IEEE Xplore and ScienceDirect, in a time window between the years 2000 and 2025, using various combinations of the key phrases for the research such as DT, Mechanical Coffee Drying, Coffee Drying Processes, Physical-Informed AI Models, etc. The summary of this process can be seen in

Figure 1.

In

Figure 1, we can see the inclusion criteria for the initial selection and filtering stage of the localized research, likewise, we can see the exclusion criteria that led us to the selection of the 32 studies that were used as support for this review.

For the most representative studies,

Table 1 summarizes four synthesis fields Process/Product, Drying Type, Modeling Approach, and Main Contribution, to provide a compact, decision-oriented mapping aligned with the review questions. The Process/Product column identifies the application domain, while Drying Type specifies the unit operation and configuration. The Modeling Approach column classifies the dominant methodological used in each work, consistent with how studies operationalize prediction and control. Finally, Main Contribution consolidates the most transferable outcome reported in the study enabling cross-study comparison and supporting the thematic synthesis across coffee mechanical drying evidence, DT enabling components for coffee drying, and DT implementations in drying and related thermal processes

4. Results

Mechanical Coffee Dryers Modeling and Assessment

The dryer’s mechanical design, energy system, and actuator capabilities determine how accurately the process can be modeled and how effectively it can be controlled. Across the reviewed evidence, recent engineering advances concentrate on improving energy efficiency and controllability, both essential for real-time sensing, state estimation, and DT-driven decision-making. The specific literature remains primarily focused on controllable drying conditions, kinetics, and quality outcomes rather than explicit DT architectures. Nevertheless, several studies provide empirical and modeling substrates needed for DT development.

The authors in [

8] developed a mechanistic model of heat and mass transfer during the drying of green coffee beans on a fixed bed, solving coupled partial differential equations for moisture diffusion and convective transfer with the drying air. The model successfully predicted internal temperature and humidity gradients and supported the design of multi-stage drying programs. Other work provides empirical kinetics for different coffee varieties and initial moistures, often using empirical equations commonly used for fruits and vegetables [

23,

24].

In [

10] an energy assessment of mechanical coffee drying was conducted on an agricultural scale, quantifying fuel consumption, thermal efficiency and the contribution of radiation and convective losses. They reported modest overall thermal efficiencies, in line with other convective dryers, and found considerable potential in heat recovery and better insulation.

The authors in [

9] investigated the impact of mechanical hot air-drying regimes on the sensory quality of specialty coffee, comparing different temperature steps and air conditioning. They found that excessively elevated temperatures or aggressive regimes can lead to the loss of desirable aromatics and the development of defects, while moderate, controlled profiles keep usage scores comparable to those of carefully managed drying. Several studies and white papers describe the implementation of simple feedback control and instrumentation, but do not yet integrate advanced model-based control or DT concepts [

4,

5,

10].

In [

32] a detailed experimental study of a coffee dryer evaluated temperature, airflow rate, and bed loading, complemented by an analysis of agitation as a mixing intervention. Drying time was found to be strongly governed by temperature and bed height, these findings suggest that, under the explored operating regime, coffee drying may be more diffusion-limited than advection-limited, implying that DT model structures should explicitly represent internal moisture migration and recognize diminishing returns from airflow increases beyond a threshold.

Regarding drying kinetics and thin-layer (moisture-ratio) modeling, these authors [

33,

34,

35] approaches yield compact parameterizations suitable for embedding into DTs as reduced-order models and for designing soft sensors that can improve predictability and mitigate over-drying risks.

DT for Drying and Related Thermal Processes

DT becomes impactful when coupled with decision-making and actions. Coffee drying is nonlinear, time-varying, and influenced by exogenous disturbances. These properties motivate robust control strategies.

A physics-based DT for fruit drying was developed in [

18], coupling detailed transport models with real-time process measurements to find best operating conditions that balance drying time, energy consumption and product quality. The study shows that DTs allow specific optimization for batches and for executions beyond static operation recipes.

In [

18] a hybrid and solar-assisted systems show that a complex control due to variable solar input is well managed by DTs that can fuse sensor data with weather forecasts to schedule auxiliary heating and maintain a consistent drying trajectory while improving renewable energy use.

The authors in [

28] proposed a DT for an indirect solar dryer using artificial neural networks trained on experimental data to predict dryer and product behavior. A global sensitivity analysis was then used to show the most influential parameters on performance, guiding design improvements and control strategies.

In [

19] they synthesized the status of DTs for drying and highlighted favorable conditions for their adoption: increasing availability of sensors and low-cost connectivity, maturity of physics simulation tools, and the need for real-time quality prediction, especially for products with high variability.

A conceptual framework for DT of food process operations was provided in [

14], emphasizing the integration of mechanistic models (e.g., computational fluid dynamics and multiscale transport models) with sensor data, and illustrating applications in cooling, maturation, and drying.

The authors in [

30] proposed a basic, physics-based DT framework for autonomous thermal food processing, making the case for simplified but accurate models connected to control systems that adjust in-line heating profiles.

A DT-enabled framework for freeze-drying was presented in [

31] that integrates scaled models of equipment and products with life cycle optimization and assessment, proving that DTs can be used to jointly improve process time, energy consumption, and environmental impacts.

The authors in [

15,

16] reflect on food DT at the system scale, encompassing applications from smart processing to logistics and supply chains. In [

17] DTs were introduced in agriculture, defining general architectures that integrate field sensors, crop models, and decision support for farm management. These frameworks, while not specific to drying, are directly relevant for integrating mechanical dryers into digital ecosystems at the farm level.

In [

36] a DT for semi-continuous fluidized-bed drying is proposed using physics-based process modeling to reduce energy consumption by informing operational adjustments, thereby supporting explicit energy-oriented objectives beyond moisture endpoint tracking.

A DT framework for smart control in vacuum filter-bed drying was presented in [

37], integrating sensor fusion, state estimation, predictive simulation, and closed-loop control to achieve target moisture under disturbances and time/energy constraints, which is directly transferable as an architectural blueprint for coffee drying DTs.

The authors in [

38] introduced a DT-aided transfer-learning strategy for thermal spray dryers under scarce labels, showing how DT-informed learning can improve energy optimization when high-quality labels are limited. The authors in [

39] demonstrated DT-oriented process modeling for lyophilization, emphasizing model-based representation, parameter management, and process supervision as core practices for robust calibration and validation that can be adopted as DT design principles in coffee drying despite differing thermodynamics.

Finally, authors in [

26] argued that DT applications in food drying remain nascent and outlined how DTs can enable operation under variable drying conditions and next-generation control, consistent with the observation that integrated DT deployments in coffee drying are still limited.

Several industrial case studies show DT-type implementations that combine models with plant data to diagnose faults and improve energy use [

13,

40]. These prove the feasibility of DTs in large-scale drying equipment and offer methodological insights for applications in coffee.

Convergence Between Coffee Dryers and DT

Systematic mapping reveals that, to date, no fully performed DTs have been explicitly reported for mechanical coffee dryers. The coffee-specific literature focuses on independent models and experiments, while DT case studies address other agricultural or food products or generic drying and thermal processes. The core technological constituents required for the convergence are already available. Nevertheless, they are commonly implemented as standalone solutions rather than as an integrated, continuously synchronized system.

However, there is conceptual and technological overlap in terms of modeling variables such as heat and mass transfer by convection, moisture diffusion, and product shrinkage. Likewise, the detection requirements are comparable between products [[

8,

18,

19,

22,

24,

28]. DT frameworks in food and agriculture already support integration with IoT platforms and cloud services that could host coffee dryer twins [

14,

15,

16,

17].

At DT Level 1 - Digital Model, there are robust mathematical representations of drying behavior as well as high-fidelity models that analyses airflow and heat/mass transfer characterization [

34]. At DT Level 2 - Digital Shadow, IoT-enabled monitoring platforms increasingly support real-time visualization of the drying process, improving operational awareness without necessarily providing predictive or bidirectional coupling [

41]. Progress toward DT Level 3 - Digital Twin is now evident through emerging closed-loop implementations; for example, fuzzy-logic-controlled rotary drying systems can be interpreted as proto-DT architectures in which measured states inform actuation in near real time [

42]. Nevertheless, fully realized, physics-grounded DT implementations represent the most immediate and transferable next step for coffee drying [

18].

5. Discussion

Although the literature on DTs for drying is expanding, it remains dominated by conceptual proposals or implementations in fruits, vegetables, and pharmaceutical contexts, while validated DT deployments for mechanical coffee dryers are notably scarce despite coffee’s economic relevance and the relative maturity of dryer modeling. Under common DT maturity classifications, the coffee field largely concentrates on a digital model/digital shadow that can be updated periodically but are not executed as continuously synchronized predictive twins and in cyber-physical systems with limited model coupling, where monitoring and control are achieved without maintaining a predictive multi-state virtual entity. By contrast, industrial drying settings more frequently instantiate explicit DT constructs suggesting that coffee DT scarcity is driven less by methodological absence and more by domain-specific data and deployment constraints such as cost, reliability, maintainability, and lot variability.

Most coffee drying models are developed and validated using controlled datasets, frequently decoupled from the real-time dynamics of commercial operations, which limit their direct use as DT cores. Moreover, agricultural-scale dryers in producing regions typically operate with minimal instrumentation, while real-time measurements of grain temperature, water activity, and internal moisture profiles remain rare; consequently, the synchronized, high-resolution datasets needed for DT quality-preserving optimization are fragmented and weakly standardized.

Coffee control practice also tends to privilege temperature and airflow, yet evidence from thin-layer studies indicates that jointly controlling temperature and relative humidity can be critical for predictability and reducing over-drying risk, implying that DT architectures that treat humidity as secondary may systematically mis predict kinetics and quality risks. Building effective coffee-dryer DTs therefore requires a pragmatic pathway that balances physical fidelity with computational flexibility and parameters that can be uniquely determined from observed data, while remaining robust and low-cost. Transferable Cyber-Physical Systems architectures indicate that multi-sensor integration is feasible at low cost, and industrial drying DTs show that mechanistic models can guide energy reduction and that DT-aided learning can mitigate sparse-label regimes through transfer learning.

In parallel, DTs can enable soft sensors for unmeasured variables like internal moisture, water activity, and expected cup quality, but adoption will depend on organizational readiness and operator trust, suggesting value in interpretable control layers and explainable machine learning for human-auditable recommendations. Ultimately, coffee DT deployment aligns with Industry 4.0 modernization goals but must respect post-harvest constraints; a realistic phased trajectory would be monitoring processes, follow by predictive soft sensors, advisory optimization, semi-autonomous control and finally, autonomous operation. All this is supported by standardized readiness and validation.

Sustainability and energy intensity emerge as primary drivers for DT adoption in coffee post-harvest operations, given that drying can account for more than 60% of the total energy demand in coffee processing. A DT can improve endpoint precision by forecasting the moisture trajectory and identifying the optimal termination point within the target range, helping to reduce systematic over-drying. DT benefits are further amplified in hybrid solar–mechanical systems, where energy input is time-varying; by assimilating weather forecasts, the DT can anticipate near-term solar availability and proactively modulate the auxiliary heat source to maximize the utilization of low-cost renewable energy while preserving a stable drying trajectory

The reviewed literature supports the feasibility of closing the loop through interpretable supervisory approaches and optimization-based strategies, which jointly manage constraint satisfaction and multi-objective performance targets. Collectively, these findings position DT technology not as a speculative add-on, but as an increasingly necessary engineering response for the coffee sector to achieve consistent quality, improved energy efficiency, and enhanced sustainability under market competition and climate-driven variability.

6. Conclusions

This systematic review has enabled a consolidated assessment of the state of research on mechanical coffee dryers in relation to the broader adoption of DTs in thermal food-processing operations. The analysis indicates that mechanical coffee dryers deliver indispensable controllability, throughput, and weather independence for post-harvest processing, yet their operation remains frequently suboptimal, with persistent challenges related to energy intensity and quality risks.

At the same time, the coffee-drying literature provides robust foundations revealing clear opportunities for energy efficiency, product uniformity, and quality optimization. In parallel, DTs have emerged as a powerful paradigm across food processing, with demonstrated benefits in contexts such as fruit drying, solar-assisted systems, and freeze-drying, where real-time optimization, supervisory decision support, and sustainability-oriented assessment are increasingly feasible.

However, the review identifies a major gap in the convergence of these two domains: explicit DT deployments for mechanical coffee drying remain virtually unexplored. To date, fully realized and validated DT implementations tailored to mechanical coffee dryers have not been reported, even though the enabling building blocks are increasingly available. These include empirical evidence linking operating conditions to quality outcomes, kinetic models developed under controlled conditions, airflow models that support design and uniformity improvements, and early-stage cyber-physical monitoring approaches applied to rotary coffee drying. Moreover, transferable DT evidence from drying-intensive industries demonstrates repeatable DT patterns that can be adapted to coffee dryers when data limitations and field constraints are explicitly addressed.

Mechanical coffee drying is undergoing a marked transition toward smart dryer operation. The evidence indicates that this shift is being enabled by the concurrent development of dryer hardware with greater actuator authority and improved thermofluidic uniformity, predictive mathematical models capable of representing drying dynamics with sufficient accuracy for decision support and closed-loop control strategies that translate model predictions and sensor measurements into energy and quality-aware actuation. In combination, these elements define the technical basis for deploying DT oriented architectures in coffee post-harvest processing.

Coffee quality is strongly coupled with the product’s thermal exposure, as several chemical attributes are heat-sensitive and can degrade under excessive or poorly managed thermal stress. Within a DT framework, thermal history tracking enables estimation of the cumulative thermal load experienced by the bean mass and supports the enforcement of quality constraints during operation. As moisture content decreases a DT can recommend or execute a variable control policy, for instance, automatically ramping down inlet air temperature to mitigate scorching risk while maintaining drying progress.

This trajectory-based strategy is consistent with evidence from other food products, where non-constant temperature operation has been shown to preserve higher levels of heat-sensitive nutrients compared with constant-temperature drying, thereby supporting the broader premise of DT-enabled quality preservation through adaptive thermodynamic control.

A practical sequence begins with upgraded instrumentation and dependable data pipelines, followed by calibrated reduced-order physics models that explicitly incorporate humidity-aware kinetics, then hybrid soft sensors and explainable machine learning to infer moisture and quality proxies, and finally hierarchical closed-loop control capable of jointly optimizing energy, time, and quality. The potential impact of this integration is substantial: hybrid modeling, virtual sensing, and model-based predictive control could deliver meaningful energy savings, improved consistency in grain quality, and enhanced traceability across coffee-drying operations.

The research on mechanical coffee drying reflects the realities of coffee production: it is diverse, context-dependent, and shaped by practical constraints in the field. According to studies, dryers differ in design and scale, instrumentation ranges from minimal to moderately advanced, and operating practices vary with climate, fuel availability, and local expertise. Consequently, authors often report outcomes using metrics that best fit their setting—drying time, fuel or electricity consumption, final moisture, or a selection of quality and sensory indicators—yet these measures are not consistently defined or collected in comparable ways.

This makes it difficult to combine results into a single quantitative narrative without oversimplifying what is, in practice, a complex socio-technical process. For this reason, the present review adopts a qualitative and thematic synthesis, focusing on what repeatedly emerges across contexts: where energy is wasted, where quality is put at risk, and which sensing and modeling elements are most promising for DT deployment.

7. Future Work

Based on this synthesis, several lines of research are proposed to advance in this field. Firstly, the development and implementation of DT prototypes for existing rotary or fixed-bed dryers is essential, prioritizing architectures that define interoperable modules and interfaces rather than monolithic models. In this sense, the sensing layer should be strengthened by instrumenting inlet/outlet air temperature and relative humidity, airflow, multi-point bed/drum temperatures, batch mass, and energy metering. On this basis, state estimation capabilities must be incorporated through soft sensors that infer batch-average moisture content with explicit uncertainty bounds, and, where feasible, spatial estimation supported by distributed measurements.

Hybrid modeling and parameter estimation should be deepened through reduced-order models that couple mechanistic energy and moisture balances, complemented by kinetics models conditioned on processing method and variety. Also, the development of models that combine principles structure with data-driven learning is proposed to capture time-varying parameters dependent on grain properties or environmental conditions.

In addition, these systems must evolve into twins that allow estimating the quality of the grain, linking model outputs and drying trajectories with sensory and physicochemical indicators, supported by explainable AI tools. Near-term priorities include explainable soft sensors that leverage mass loss, humidity differentials, etc., as well as interpretable predictors with transparent uncertainty reporting; hybrid explanation schemes that integrate physics-based constraints with ML attributions are also recommended to improve operator trust and facilitate adoption.

Moreover, the transition from monitoring to actionable DTs requires the explicit integration of decision and control modules. It is proposed to embed multi-objective optimization for setpoint scheduling of temperature and airflow trajectories, combined with anomaly detection for early warning. Emphasis should be placed on real-time closed-loop endpoint control to stop at target moisture with minimal over-drying, adaptive schedule control under ambient humidity disturbances, and fault detection based on DT differences between measured and predicted states.

Finally, it is crucial to address the sustainability and scalability of these solutions by integrating dryers with renewable energy sources and using DT-driven scheduling according to energy availability. To ensure applicability in rural contexts, DT implementations should support edge devices under intermittent connectivity, prioritize low-cost and maintainable sensors, and provide interfaces adapted to smallholder producers. In parallel, the consolidation of standardized datasets is identified as a field-wide acceleration lever, including minimum dataset specifications, standardized protocols for quality labeling, and public benchmarks for moisture prediction and schedule optimization under realistic operational constraints.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Cristian Valencia-Payan, Juan Fernando Casanova Olaya and Juan Carlos Corrales.; methodology, Cristian Valencia-Payan.; writing—original draft preparation, Cristian Valencia-Payan.; writing—review and editing, Juan Fernando Casanova Olaya and Juan Carlos Corrales. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Telematics Engineering Group (GIT) of the University of Cauca and the AgroTIC Group of Ecotecma SAS, as well as the Ministry of Science, Technology and Innovation of Colombia (Minciencias) for the postdoctoral support granted to Cristian Valencia Payan, through the call “934-2023 CONVOCATORIA DE ESTANCIAS POSDOCTORALES ORIENTADAS POR MISIONES”

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| DT |

Digital Twin |

| ICO |

International Coffee Organization |

| FNC |

Federación Nacional de Cafeteros |

References

- Bhumiratana, N.; Adhikari, K.; Chambers, E. Evolution of sensory aroma attributes from coffee beans to brewed coffee. LWT - Food Science and Technology 2011, vol. 44(no. 10), 2185–2192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong, H. T. T. Community Initiatives and Local Networks among K’ho Cil Smallholder Coffee Farmers in the Central Highlands of Vietnam: A Case Study. J Asian Afr Stud 2020, vol. 55(no. 6), 880–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietz, T.; Estrella Chong, A.; Grabs, J.; Kilian, B. How Effective is Multiple Certification in Improving the Economic Conditions of Smallholder Farmers? Evidence from an Impact Evaluation in Colombia’s Coffee Belt. Journal of Development Studies 2020, vol. 56(no. 6), 1141–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, P.; Venkatachalapathy, N. Processing and Drying of Coffee-A Review. Dec 2014, vol. 3. Available online: www.ijert.org.

- Carlos, L.; Villalba, O.; Alexander, Eduardo; Grisales, D.; Rodriguez, E. State of the art of coffee drying technologies in Colombia and their global development Estado de las tecnologías de secado de café en Colombia y avances a nivel mundial. Pág 2017, vol. 38, 27. [Google Scholar]

- F. Federación Nacional de Cafeteros, “Resolución 02 de 2016.” Accessed: Jan. 08, 2021. Available online: https://federaciondecafeteros.org/app/uploads/2019/11/6.-Normas-de-calidad-para-café-verde-en-almendra-para-exportación-Resolución-2-2016.pdf.

- F. Federación Nacional de Cafeteros, Aprenda a vender su café. 07 Jan 2021. Available online: https://federaciondecafeteros.org/wp/servicios-al-caficultor/aprenda-a-vender-su-cafe/.

- Hernández-Díaz, W. N.; Ruiz-López, I. I.; Salgado-Cervantes, M. A.; Rodríguez-Jimenes, G. C.; García-Alvarado, M. A. Modeling heat and mass transfer during drying of green coffee beans using prolate spheroidal geometry. J Food Eng 2008, vol. 86(no. 1), 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Largo-Avila, E. , The influence of hot-air mechanical drying on the sensory quality of specialty Colombian coffee. AIMS Agriculture and Food 2023 3 2023, 789, vol. 8(no. 3), 789–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres Mejía, F. , Energy Evaluation of the Mechanical Drying of the Grain of Coffea arabica from Honduras. Asian Journal of Biology 2021, vol. 11(no. 1), 64446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, F.; Zhang, H.; Liu, A.; Nee, A. Y. C. Digital Twin in Industry: State-of-the-Art. IEEE Trans Industr Inform 2019, vol. 15(no. 4), 2405–2415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Fang, S.; Dong, H.; Xu, C. Review of digital twin about concepts, technologies, and industrial applications. J Manuf Syst 2021, vol. 58, 346–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semeraro, C.; Lezoche, M.; Panetto, H.; Dassisti, M. Digital twin paradigm: A systematic literature review. Comput Ind 2021, vol. 130, 103469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verboven, P.; Defraeye, T.; Datta, A. K.; Nicolai, B. Digital twins of food process operations: the next step for food process models? Curr Opin Food Sci 2020, vol. 35, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krupitzer, C.; Noack, T.; Borsum, C.; Krupitzer, C.; Noack, T.; Borsum, C. Digital Food Twins Combining Data Science and Food Science: System Model, Applications, and Challenges. Processes 2022, Vol. 10, vol. 10(no. 9). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henrichs, E. , Can a Byte Improve Our Bite? An Analysis of Digital Twins in the Food Industry. Sensors 2022, Vol. 22, vol. 22(no. 1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pylianidis, C.; Osinga, S.; Athanasiadis, I. N. Introducing digital twins to agriculture. Comput Electron Agric 2021, vol. 184, 105942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prawiranto, K.; Carmeliet, J.; Defraeye, T. Physics-Based Digital Twin Identifies Trade-Offs Between Drying Time, Fruit Quality, and Energy Use for Solar Drying. Front Sustain Food Syst 2021, vol. 4, 606845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thijs, D.; Onwude, D. I. The future of digital twins for drying. Drying Technology 2020, vol. 39(no. 1), 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M. J. , The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, vol. 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peñuela-Martínez, A. E.; Sanz-Uribe, J. R.; Medina-Rivera, R. D. Influence of drying air temperature on coffee quality during storage. Rev Fac Nac Agron Medellin 2023, vol. 76(no. 3), 10493–10503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamidi, R. O.; Jiang, L.; Pathare, P. B.; Wang, Y. D.; Roskilly, A. P. Recent advances in sustainable drying of agricultural produce: A review. Appl Energy 2019, vol. 233–234, 367–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Zhang, M.; Mujumdar, A. S.; Chitrakar, B. Recent developments in physical field-based drying techniques for fruits and vegetables. Drying Technology 2019, vol. 37(no. 15), 1954–1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onwude, D. I.; Hashim, N.; Janius, R. B.; Nawi, N. M.; Abdan, K. Modeling the Thin-Layer Drying of Fruits and Vegetables: A Review. In Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf; 2016; vol. 15, no. 3, pp. 599–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collazos-Escobar, G. A.; Gutiérrez-Guzmán, · Nelson; Henry; Váquiro, A.; García-Pérez, J. V; Cárcel, J. A. Analysis of Machine Learning Algorithms for the Computer Simulation of Moisture Sorption Isotherms of Coffee Beans; 1947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arefi, A. Convergence of Digital Twins and food drying technology: How to bring the next generation of dryers to life!? 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purlis, E. Digital Twin Methodology in Food Processing: Basic Concepts and Applications. Current Nutrition Reports 2024 13 2024, 4, vol. 13(no. 4), 914–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cetina-Quiñones, A. J.; Arıcı, M.; Cisneros-Villalobos, L.; Bassam, A. Digital twin model and global sensitivity analysis of an indirect type solar dryer with sensible heat storage material: An approach from exergy sustainability indicators under tropical climate conditions. J Energy Storage 2023, vol. 58, 106368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nget, S. , The Development of a Digital Twin to Improve the Quality and Safety Issues of Cambodian Pâté: The Application of 915 MHz Microwave Cooking. Foods 2023, Vol. 12, vol. 12(no. 6). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kannapinn, M.; Pham, M. K.; Schäfer, M. Physics-based digital twins for autonomous thermal food processing: Efficient, non-intrusive reduced-order modeling. Innovative Food Science & Emerging Technologies 2022, vol. 81, 103143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juckers, A. , Digital Twin Enabled Process Development, Optimization and Control in Lyophilization for Enhanced Biopharmaceutical Production. Processes 2024 2024, Vol. 12, vol. 12(no. 1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orozco-Blanco, D.-A. , Mechanical Drying of Coffee: Influence of Operating Parameters on Cup Quality. Biotecnología en el Sector Agropecuario y Agroindustrial 2025, vol. 23(no. 1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sihombing, H. V.; Ambarita, H.; Silalahi, J. F. Comparative study of mathematical and experimental models of coffee bean drying rate in a solar dryer simulator. E3S Web of Conferences 2024, vol. 519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phitakwinai, S.; Thepa, S.; Nilnont, W. Thin-layer drying of parchment Arabica coffee by controlling temperature and relative humidity. Food Sci Nutr 2019, vol. 7(no. 9), 2921–2931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernando, M.; Vargas, V.; Durán Barón, R.; Alean, J.; Velásquez, H. J. Ciro. Drying kinetics of organic parchment coffee beans (Coffea arabica L.) using microwave fluidised bed: Semi-theoretical modeling. Revista Ingenierías Universidad de Medellín 2021, vol. 20(no. 39), 167–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntamo, D.; Kuliss, V.; Soulatiantork, P.; Omar, C.; Zandi, M. Optimising energy usage of a semi-continuous fluidised bed dryer using digital twin technology and energy management strategies. International Journal of Sustainable Engineering 2025, vol. 18(no. 1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irndorfer, S. , A digital twin of a vacuum filter-bed dryer. Int J Pharm 2026, vol. 687, 126427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bardeeniz, S.; Panjapornpon, C.; Fongsamut, C.; Ngaotrakanwiwat, P.; Hussain, M. Azlan. Digital twin-aided transfer learning for energy efficiency optimization of thermal spray dryers: Leveraging shared drying characteristics across chemicals with limited data. Appl Therm Eng 2024, vol. 242, 122431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klepzig, L. S. , Digital Twin for Lyophilization by Process Modeling in Manufacturing of Biologics. Processes 2020, Vol. 8, vol. 8(no. 10), 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero-Hernández, V. , Digital Twins: A Solution Under the Standard k-ε Model in Industrial CFD, to Predict Ideal Conditions in a Sugar Dryer. Fluids 2025, Vol. 10, vol. 10(no. 6). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta-Minoli, C.; Carmona, P.-C.; Mesa-Mazo, M.; Vargas-Gil, J.-D.; Velásquez, J.-P. Tecnología basada en IoT para el análisis de datos del proceso de secado de café de pequeños agricultores. Revista Facultad de Ingeniería 2024, vol. 33(no. 69), e17404–e17404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nafisah, N.; Syamsiana, I. N.; Putri, R. I.; Kusuma, W.; Sumari, A. D. W. Implementation of fuzzy logic control algorithm for temperature control in robusta rotary dryer coffee bean dryer. MethodsX 2024, vol. 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).