Submitted:

14 July 2025

Posted:

15 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Identification of Volatile Compounds in Panamanian Geisha Coffee

2.1.1. N-Heterocyclic Compounds - Pyrazines

2.1.2. Terpenes

2.1.3. Aldehydes and Ketones

2.1.4. Esters

2.1.5. Furans

2.1.6. Fatty Acids

2.1.7. Organic Acids and Phenols

2.2. Sensory Evaluation

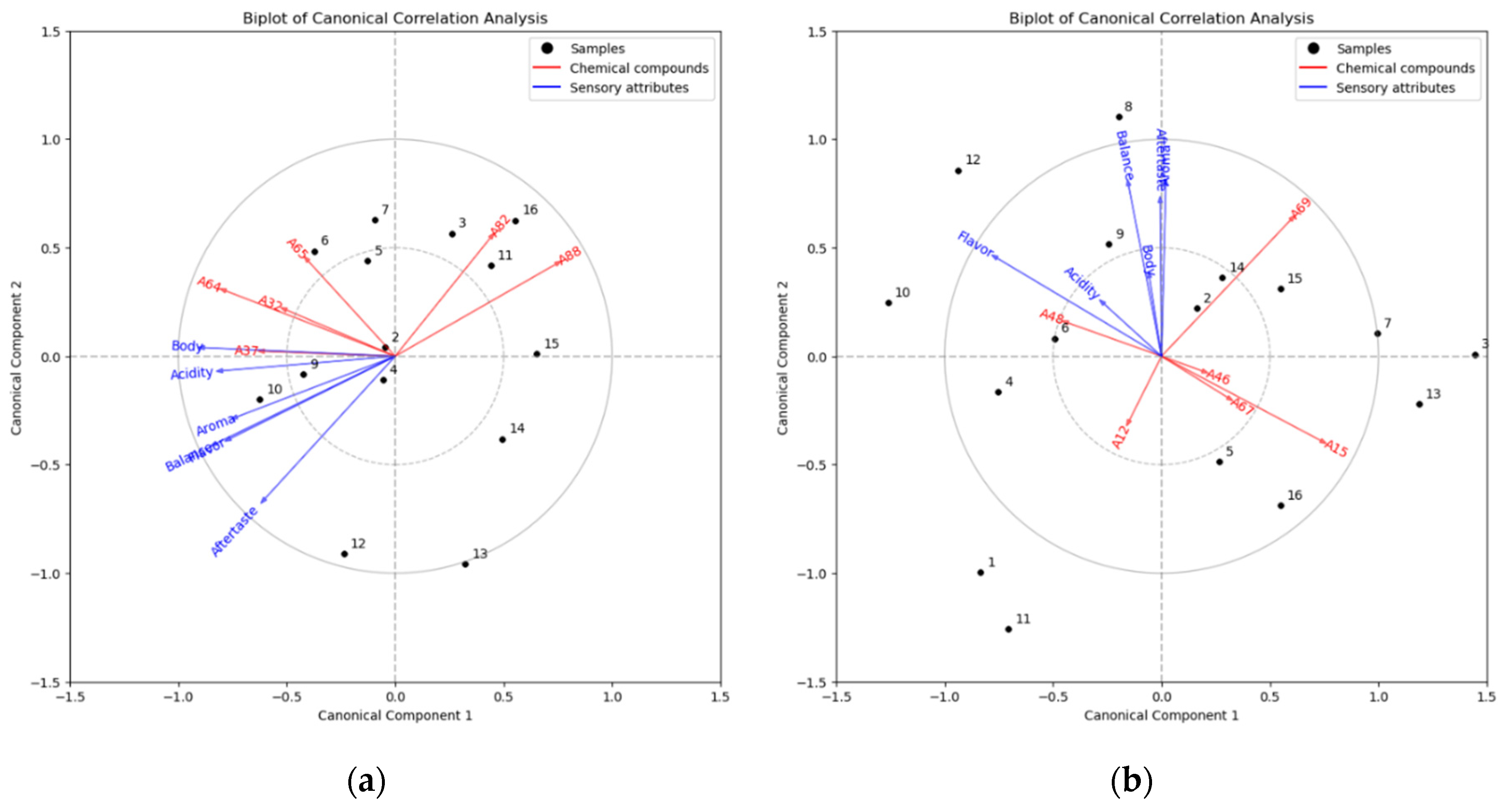

2.3. Chemometric Analysis

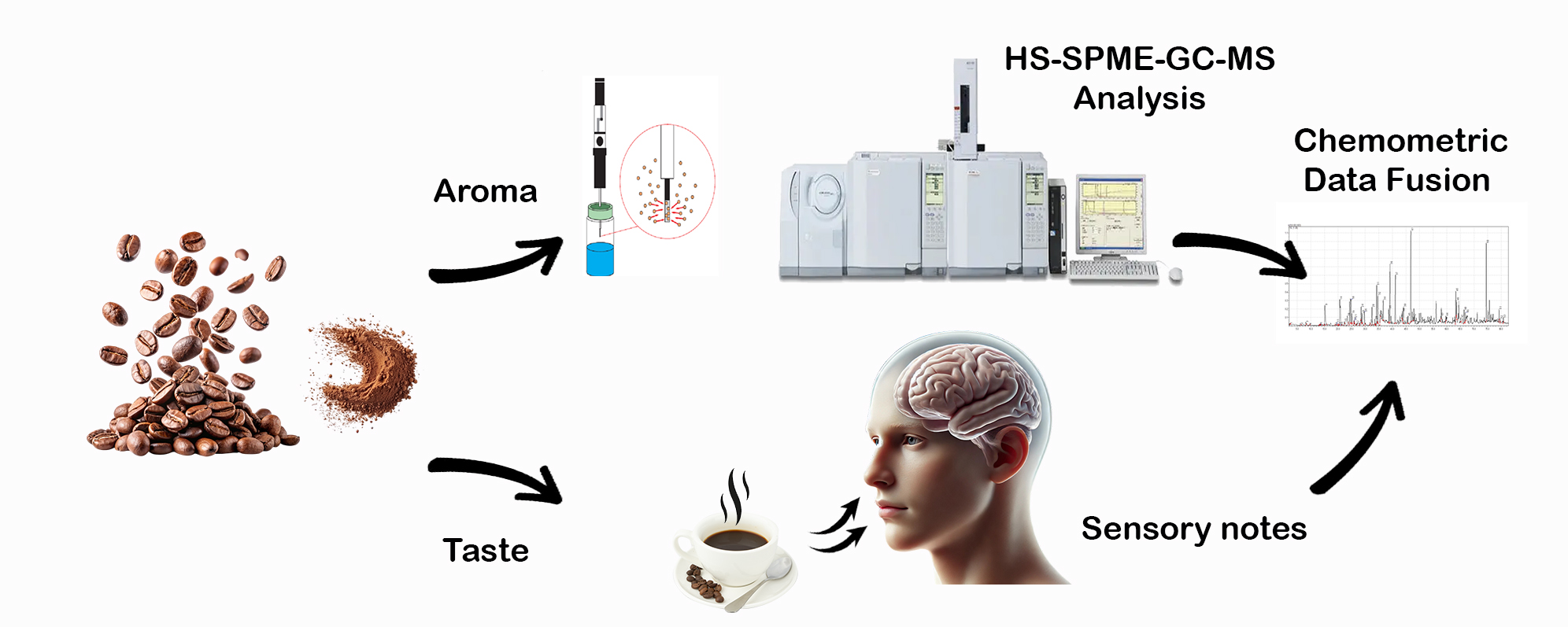

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Chemicals and Reagents

3.2. Sample Collection

3.3. Headspace Solid-Phase Microextraction Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (HS-SPME-GC-MS) for Identifying Volatile Compounds in Geisha Coffees

3.4. Sensory Evaluation

3.5. Chemometric Analysis

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CCA | Canonical Correlation Analysis |

| DVB/CAR/PDMS | Divinylbenzene/Carboxen/Polydimethylsiloxane |

| GC-MS | Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry |

| HS | Headspace |

| LRI | Linear Retention Index |

| NIST | National Institute of Standards and Technology |

| RT | Retention Time |

| SCAP | Specialty Coffee Association of Panama |

| SPME | Solid Phase Microextraction |

| VOCs | Volatile Organic Compounds |

References

- Piccino, S.; Boulanger, R.; Descroix, F.; Shum, A.; Sing, C. Aromatic Composition and Potent Odorants of the “Specialty Coffee” Brew “Bourbon Pointu” Correlated to Its Three Trade Classifications. Food Res. Int. 2013, 61, 264–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sepúlveda, W. S.; Chekmam, L.; Maza, M. T.; Mancilla, N. O. Consumers’ Preference for the Origin and Quality Attributes Associated with Production of Specialty Coffees: Results from a Cross-Cultural Study. Food Res. Int. 2016, 89, 997–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnoletti, B. Z.; Folli, G. S.; Pereira, L. L.; Pinheiro, P. F.; Guarçoni, R. C.; da Silva Oliveira, E. C.; Filgueiras, P. R. Multivariate Calibration Applied to Study of Volatile Predictors of Arabica Coffee Quality. Food Chem. 2022, 367, 130679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Córdoba, N.; Moreno, F. L.; Osorio, C.; Velásquez, S.; Fernandez-Alduenda, M.; Ruiz-Pardo, Y. Specialty and Regular Coffee Bean Quality for Cold and Hot Brewing: Evaluation of Sensory Profile and Physicochemical Characteristics. LWT. 2021, 145, 111363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torga, G. N.; Spers, E. E. Perspectives of Global Coffee Demand. In Coffee Consumption and Industry Strategies in Brazil: A Volume in the Consumer Science and Strategic Marketing Series; Elsevier. 2020, 21–49.

- Costa, B. D. R. Brazilian Specialty Coffee Scenario. In Coffee Consumption and Industry Strategies in Brazil: A Volume in the Consumer Science and Strategic Marketing Series; Elsevier. 2020, 51–64.

- Seninde, D. R.; Chambers, E. Coffee Flavor: A Review. Beverages. 2020, 6(3), 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laukaleja, I.; Kruma, Z. Quality of Specialty Coffee: Balance between Aroma, Flavour and Biologically Active Compound Composition: Review. Res. Rural Dev. 2018, 240–247. [Google Scholar]

- SCA. A Specialty Coffee Association Resource Protocols and Best Practices; 2018.

- Lingle, T. R.; Menon, S. N. Cupping and Grading-Discovering Character and Quality. In The Craft and Science of Coffee; Elsevier. 2017, 181–203.

- Wilson, A. P.; Wilson, N. L. W. The Economics of Quality in the Specialty Coffee Industry: Insights from the Cup of Excellence Auction Programs. Agric. Econ. 2014, 45(S1), 91–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toledo, P. R. A. B.; Pezza, L.; Pezza, H. R.; Toci, A. T. Relationship Between the Different Aspects Related to Coffee Quality and Their Volatile Compounds. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf. 2016, 15(4), 705–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girma, B.; Sualeh, A. A Review of Coffee Processing Methods and Their Influence on Aroma. Int. J. Food Eng. Technol. 2022, 6(1), 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarigan, E. B.; Wardiana, E.; Hilmi, Y. S.; Komarudin, N. A. The Changes in Chemical Properties of Coffee during Roasting: A Review. In IOP Conf. Ser.: Earth Environ. Sci.; IOP Publishing Ltd. 2022, 974(1), 012115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catão, A. A.; Mateus, N. de S.; Garcia, C. da C.; da Silva, M. C.; Novaes, F. J. M.; Alves, S.; Marriott, P. J.; da Silva, A. I. Coffee-Roasting Variables Associated with Volatile Organic Profiles and Sensory Evaluation Using Multivariate Analysis. Appl. Food Res. 2022, 2(2), 100223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordoba, N.; Fernandez-Alduenda, M.; Moreno, F. L.; Ruiz, Y. Coffee Extraction: A Review of Parameters and Their Influence on the Physicochemical Characteristics and Flavour of Coffee Brews. Trends Food Sci Technol. 2020, 96, 45–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, N.; Liu, C.; Liu, X.; Degn, T. K.; Munchow, M.; Fisk, I. Determination of Volatile Marker Compounds of Common Coffee Roast Defects. Food Chem. 2016, 211, 206–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bona, E.; Da Silva, R. S. D. S. F. Coffee and the Electronic Nose. In Electron. Noses Tongues Food Sci; Academic Press. 2016, 31–38.

- Hernandes, K. C.; Souza-Silva, É. A.; Assumpção, C. F.; Zini, C. A.; Welke, J. E. Matrix-Compatible Solid Phase Microextraction Coating Improves Quantitative Analysis of Volatile Profile throughout Brewing Stages. Food Res. Int. 2019, 123, 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamgang Nzekoue, F.; Angeloni, S.; Caprioli, G.; Cortese, M.; Maggi, F.; Marconi, U. M. B.; Perali, A.; Ricciutelli, M.; Sagratini, G.; Vittori, S. Fiber-Sample Distance, An Important Parameter to Be Considered in Headspace Solid-Phase Microextraction Applications. Anal Chem. 2020, 92(11), 7478–7484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shirey, R. E. SPME Commercial Devices and Fibre Coatings. In Handbook of Solid Phase Microextraction; Elsevier. 2012; 99–133.

- Billiard, K. M.; Dershem, A. R.; Gionfriddo, E. Implementing Green Analytical Methodologies Using Solid-Phase Microextraction: A Review. Molecules 2020, 25(22). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuwono, S. S.; Hanasasmita, N.; Sunarharum, W. B.; Harijono. Effect of Different Aroma Extraction Methods Combined with GC-MS on the Aroma Profiles of Coffee. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, IOP Publishing. 2019, 230 (1), 012044.

- Borém, F. M.; Abreu, G. F. de; Alves, A. P. de C.; Santos, C. M. dos; Teixeira, D. E. Volatile Compounds Indicating Latent Damage to Sensory Attributes in Coffee Stored in Permeable and Hermetic Packaging. Food Packag Shelf Life. 2021, 29, 100705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacalone, D.; Degn, T. K.; Yang, N.; Liu, C.; Fisk, I.; Münchow, M. Common Roasting Defects in Coffee: Aroma Composition, Sensory Characterization and Consumer Perception. Food Qual Prefer. 2019, 71, 463–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fassio, L. O.; Malta, M. R.; Liska, G. R.; Alvarenga, S. T.; Sousa, M. M. M.; Farias, T. R. T.; Pereira, R. G. F. A. Sensory Profile and Chemical Composition of Specialty Coffees from Matas de Minas Gerais, Brazil. J. Agric. Sci. 2017, 9(9), 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, M. de S. G.; Scholz, M. B. dos S.; Kitzberger, C. S. G.; Benassi, M. de T. Correlation between the Composition of Green Arabica Coffee Beans and the Sensory Quality of Coffee Brews. Food Chem. 2019, 292, 275–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bressanello, D.; Marengo, A.; Cordero, C.; Strocchi, G.; Rubiolo, P.; Pellegrino, G.; Ruosi, M. R.; Bicchi, C.; Liberto, E. Chromatographic Fingerprinting Strategy to Delineate Chemical Patterns Correlated to Coffee Odor and Taste Attributes. J Agric Food Chem. 2021, 69(15), 4550–4560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, J. S.; Augusto, F.; Salva, T. J. G.; Ferreira, M. M. C. Prediction Models for Arabica Coffee Beverage Quality Based on Aroma Analyses and Chemometrics. Talanta. 2012, 101, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, J. S.; Augusto, F.; Salva, T. J. G.; Thomaziello, R. A.; Ferreira, M. M. C. Prediction of Sensory Properties of Brazilian Arabica Roasted Coffees by Headspace Solid Phase Microextraction-Gas Chromatography and Partial Least Squares. Anal Chim Acta. 2009, 634(2), 172–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uurtio, V., Monteiro, J. M., Kandola, J., Shawe-Taylor, J., Fernandez-Reyes, D., & Rousu, J. A tutorial on canonical correlation methods. ACM Comput. Surv. (CSUR) 2017, 50(6), 1–33.

- Vega, A.; De León, J. A.; Reyes, S. M.; Gallardo, J. M. Modelo Matemático Para Determinar La Correlación Entre Parámetros Fisicoquímicos y La Calidad Sensorial de Café Geisha y Pacamara de Panamá. Inf. Tecnol. 2021, 32(1), 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega, A.; De León, J. A.; Reyes, S. M.; Miranda, S. Y. Componentes Bioactivos de Diferentes Marcas de Café Comerciales de Panamá. Relación Entre Ácidos Clorogénicos y Cafeína. Inf. Tecnol. 2018, 29(4), 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santamaría, N.; Meléndez, F.; Arroyo, P.; Calvo, P.; Sánchez, F.; Lozano, J.; Sánchez, R. Olfactory Evaluation of Geisha Coffee from Panama Using Electronic Nose. Chemosensors. 2023, 11(11), 559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortzfeld, F. B.; Hashem, C.; Vranková, K.; Winkler, M.; Rudroff, F. Pyrazines: Synthesis and Industrial Application of These Valuable Flavor and Fragrance Compounds. Biotechnol. J. 2020, 15(11), 2000064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bressanello, D.; Liberto, E.; Cordero, C.; Sgorbini, B.; Rubiolo, P.; Pellegrino, G.; Ruosi, M. R.; Bicchi, C. Chemometric Modeling of Coffee Sensory Notes through Their Chemical Signatures: Potential and Limits in Defining an Analytical Tool for Quality Control. J Agric Food Chem. 2018, 66(27), 7096–7109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhalis, H.; Cox, J.; Frank, D.; Zhao, J. The Role of Wet Fermentation in Enhancing Coffee Flavor, Aroma, and Sensory Quality. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2021, 247(2), 485–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dippong, T.; Dan, M.; Kovacs, M. H.; Kovacs, E. D.; Levei, E. A.; Cadar, O. Analysis of Volatile Compounds, Composition, and Thermal Behavior of Coffee Beans According to Variety and Roasting Intensity. Foods. 2022, 11(19), 3146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbosa, M. de S. G.; Francisco, J. S.; dos Santos Scholz, M. B.; Kitzberger, C. S. G.; Benassi, M. de T. Dynamics of Sensory Perceptions in Arabica Coffee Brews with Different Roasting Degrees. J Culin Sci Technol. 2019, 17(5), 453–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakidou, P.; Plati, F.; Matsakidou, A.; Varka, E. M.; Blekas, G.; Paraskevopoulou, A. Single Origin Coffee Aroma: From Optimized Flavor Protocols and Coffee Customization to Instrumental Volatile Characterization and Chemometrics. Molecules. 2021, 26(15), 4609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmud, M. M. C.; Shellie, R. A.; Keast, R. Unravelling the Relationship between Aroma Compounds and Consumer Acceptance: Coffee as an Example. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf. 2020, 19(5), 2380–2420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunarharum, W. B.; Williams, D. J.; Smyth, H. E. Complexity of Coffee Flavor: A Compositional and Sensory Perspective. Food Res. Int. 2014, 62, 315–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bressani, A. P. P.; Martinez, S. J.; Sarmento, A. B. I.; Borém, F. M.; Schwan, R. F. Organic Acids Produced during Fermentation and Sensory Perception in Specialty Coffee Using Yeast Starter Culture. Food Res. Int. 2020, 128, 108773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toci, A. T.; Farah, A. Volatile Fingerprint of Brazilian Defective Coffee Seeds: Corroboration of Potential Marker Compounds and Identification of New Low Quality Indicators. Food Chem. 2014, 153, 298–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batool, Z.; Xu, D.; Zhang, X.; Li, X.; Li, Y.; Chen, Z.; Li, B.; Li, L. A Review on Furan: Formation, Analysis, Occurrence, Carcinogenicity, Genotoxicity and Reduction Methods. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021, 61(3), 395–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y. J.; Choi, J.; Lee, G.; Lee, K. G. Analysis of Furan and Monosaccharides in Various Coffee Beans. J Food Sci Technol. 2021, 58(3), 862–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petisca, C.; Pérez-Palacios, T.; Farah, A.; Pinho, O.; Ferreira, I. M. P. L. V. O. Furans and Other Volatile Compounds in Ground Roasted and Espresso Coffee Using Headspace Solid-Phase Microextraction: Effect of Roasting Speed. Food Bioprod. Process. 2013, 91(3), 233–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vezzulli, F.; Lambri, M.; Bertuzzi, T. Volatile Compounds in Green and Roasted Arabica Specialty Coffee: Discrimination of Origins, Post-Harvesting Processes, and Roasting Level. Foods. 2023, 12(3), 489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Böger, B. R.; Mori, A. L. B.; Viegas, M. C.; Benassi, M. T. Quality Attributes of Roasted Arabica Coffee Oil Extracted by Pressing: Composition, Antioxidant Activity, Sun Protection Factor and Other Physical and Chemical Parameters. Grasas y Aceites. 2021, 72(1), e394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demianová, A.; Bobková, A.; Lidiková, J.; Jurčaga, L.; Bobko, M.; Belej, Ľ.; Kolek, E.; Poláková, K.; Iriondo-DeHond, A.; Dolores del Castillo, M. Volatiles as Chemical Markers Suitable for Identification of the Geographical Origin of Green Coffea Arabica L. Food Control. 2022, 136, 108869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poisson, L.; Blank, I.; Dunkel, A.; Hofmann, T. Poisson, L.; Blank, I.; Dunkel, A.; Hofmann, T. The Chemistry of Roasting-Decoding Flavor Formation. In The Craft and Science of Coffee, Academic Press. 2017, 273–309.

- Caporaso, N.; Whitworth, M. B.; Cui, C.; Fisk, I. D. Variability of Single Bean Coffee Volatile Compounds of Arabica and Robusta Roasted Coffees Analysed by SPME-GC-MS. Food Res. Int. 2018, 108, 628–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueiredo, L. P.; Borem, F. M.; Ribeiro, F. C.; Giomo, G.; Taveira, J. H. da S.; Malta, M. R. Fatty Acid Profiles and Parameters of Quality of Specialty Coffees Produced in Different Brazilian Regions. Afr J Agric Res. 2015, 10(35), 3484–3493. [Google Scholar]

- Toci, A. T.; Azevedo, D. A.; Farah, A. Effect of Roasting Speed on the Volatile Composition of Coffees with Different Cup Quality. Food Res. Int. 2020, 137, 109546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z., Xi, G., Fu, Y., Wang, Q., Cai, L., Zhao, Z.,... & Ma, Y. Synthesis of 2, 3-dihydro-3, 5-dihydroxy-6-methyl-4H-pyran-4-one from maltol and its taste identification. Food Chem. 2021, 361, 130052.

- Dorfner, R., Ferge, T., Kettrup, A., Zimmermann, R., & Yeretzian, C. Real-time monitoring of 4-vinylguaiacol, guaiacol, and phenol during coffee roasting by resonant laser ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2003, 51(19), 5768–5773.

- Adams, R. P. Essential Oil Components by Chromatography/Quadrupole Mass Spectrometry. Diablo Analytical: California 2007.

| *RT a (min) | Compound name | N° CAS | odor descriptor b |

formula | LRI Supelcowax 10 c |

LRI SH Rxi-5HT d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alcohol | ||||||

| 4.71 | Ethanol | 64 - 17 - 5 | - | C2H6O | <1010 | |

| 6.00 | 1,3-butanediol | 107 - 88 - 0 | - | C4H10O2 | <810 | |

| 6.43 | 4-methyl-2-pentanol | 108-11-2 | pungent, alcoholic | C6H14O | <810 | |

| 6.51 | 2-butanol | 78 - 92 - 2 | sweet, apricot | C4H10O | <810 | |

| 12.31 | 2-methyl-1-pentanol | 105 - 30 - 6 | - | C6H14O | 1136.0 | |

| 12.31 | 2-ethylbutanol | 97 - 95 - 0 | sweet, musty, alcoholic | C6H14O | 948.1 | |

| 23.29 | Acetol | 116 - 09 - 6 | pungent, sweet, caramellic, ethereal | C3H6O2 | 1297.0 | |

| 41.52 | 2,3-butanediol | 513 - 85 - 9 | fruity, creamy, buttery | C4H10O2 | 1572.2 | <810 |

| 78.28 | Hexadecanol | 36653 - 82 - 4 | waxy, clean, greasy, floral, oily | C16H34O | 2377.6 | |

| Aldehyde | ||||||

| 2.33 | Acetaldehyde | 75 - 07 - 0 | pungent, ethereal, aldehydic, fruity | C2H4O | <1010 | |

| 4.29 | 2-methylbutanal | 96 - 17 - 3 | musty, cocoa, phenolic coffee, nutty, malty, fermented, fatty alcoholic | C5H10O | <1010 | |

| 37.47 | Benzaldehyde | 100 - 52 - 7 | sharp, sweet, bitter, almond, cherry | C7H6O | 1506.1 | |

| 41.24 | 5-acetoxymethyl-2-furaldehyde | 10551 - 58 - 3 | baked, bread | C8H8O4 | 1296.4 | |

| 44.82 | 2-furancarboxaldehyde | 23074 - 10 - 4 | - | C7H8O2 | 1626.8 | |

| 52.89 | Cumaldehyde | 122 - 03 - 2 | Spicy, green, cumin-like with green herbal spice, nuances | C10H12O | 1765.2 | |

| 54.79 | (E, E)-2,4-decadienal | 25152 - 84 - 5 | oily, cucumber, melon, citrus, pumpkin, nut, meat | C10H16O | 1798.6 | |

| 61.21 | Benzene acetaldehyde | 4411 - 89 - 6 | sweet, narcissus, cortex, beany, honey, cocoa, nutty radish | C10H10O | 1917.6 | |

| Aromatic compound | ||||||

| 26.96 | 2-ethyl-p-xylene | 1758 - 88 - 9 | - | C10H14 | 1350.6 | |

| 56.57 | (1-butylheptyl)benzene | 4537 - 15 - 9 | - | C17H28 | 1831.3 | |

| 58.63 | trimethyl pentanyl diisobutyrate | 6846 - 50 - 0 | - | C16H30O4 | 1869.0 | |

| 58.62 | Benzenemethanol | 100 - 51 - 6 | - | C7H8O | 1869.2 | |

| 58.78 | (1-ethylnonyl)benzene | 4536 - 87 - 2 | - | C17H28 | 1872.0 | |

| 60.36 | Benzeneethanol | 60 - 12 - 8 | - | C8H10O | 1901.3 | |

| 61.54 | (1-pentylheptyl)benzene | 2719 - 62 - 2 | - | C18H30 | 1923.9 | |

| 61.96 | (1-butyloctyl)benzene | 2719 - 63 - 3 | - | C18H30 | 1932.1 | |

| 70.28 | (1-ethylundecyl)benzene | 4534 - 52 - 5 | - | C19H32 | 2082.9 | |

| 78.69 | Coumaran | 496 - 16 - 2 | - | C8H8O | 2400.9 | |

| Ester | ||||||

| 2.97 | isopropenyl acetate | 108 - 22 - 5 | ethereal, acetic, fruity, sweet, berry, grape, skin | C5H8O2 | <1010 | |

| 3.91 | Ethyl acetate | 141 - 78 - 6 | - | C4H8O2 | <1010 | |

| 12.29 | isoamyl acetate | 123 - 92 - 2 | sweet, fruity, banana | C7H14O2 | 1135.8 | |

| 19.33 | Furfuryl methyl ether | 13679 - 46 - 4 | coffee roasted, coffee | C6H8O2 | 1240.4 | |

| 27.06 | Glycidyl methyl ether | 930 - 37 - 0 | - | C4H8O2 | 1352.2 | |

| 34.62 | 1,2-ethanediol, diacetate | 111 - 55 - 7 | green, floral, estery, alcoholic | C6H10O4 | 1463.3 | |

| 35.23 | Furfuryl pentanoate | 36701 - 01 - 6 | C10H14O3 | 1212.1 | ||

| 38.87 | 2-butanone, 1-(acetyloxy) | 1575 - 57 - 1 | - | C6H10O3 | 1528.9 | |

| 38.91 | Furfuryl acetate | 623 - 17 - 6 | sweet, fruity, banana, horseradish | C7H8O3 | 1529.5 | 987.0 |

| 52.59 | Methyl salicylate | 119 - 36 - 8 | - | C8H8O3 | 1759.9 | |

| 72.70 | phenoxyethanol | 122-99-6 | rose, balsamic, cinnamyl | C8H10O2 | 2141.5 | |

| 73.74 | Hexahydrofarnesyl acetone | 502 - 69 - 2 | C18H36O | 1844.69 | ||

| Fatty acids | ||||||

| 8.73 | Ethyl 2-methylbutanoate | 7452 - 79 - 1 | Fruity, estry, and berry with fresh tropical nuances | C7H14O2 | 1073.6 | |

| 9.45 | ethyl isovalerate | 108 - 64 - 5 | Sweet, diffusive, estry, fruity, sharp, pineapple, apple, green, and orange | C7H14O2 | 1073.6 | |

| 26.40 | ethyl lactate | 97 - 64 - 3 | Sweet, fruity, acidic, etherial with a brown nuance | C5H10O3 | 1342.5 | |

| 26.67 | Vinyl butyrate | 123 - 20 - 6 | - | C6H10O2 | 1346.4 | |

| 38.60 | vinyl propionate | 105-38-4 | - | C5H8O2 | 1524.4 | |

| 47.48 | diethyl succinate | 123-25-1 | mild, fruity, cooked, apple, ylang | C8H14O4 | 1671.4 | |

| 55.57 | β-methylcrotonic acid | 541 - 47 - 9 | green, phenolic, dairy | C5H8O2 | 1813.0 | 931.6 |

| 58.88 | Hydrocinnamic acid, ethyl ester | 2021 - 28 - 5 | hyacinth, rose, honey, fruity, rum | C11H14O2 | 1873.9 | |

| 71.85 | Myristic acid, ethyl ester | 124 - 06 - 1 | sweet, waxy, violet orris | C16H32O2 | 1792.1 | |

| 75.88 | Palmitic acid, ethyl ester | 628 - 97 - 7 | soft, waxy | C18H36O2 | 2252.8 | 1987.1 |

| 75.90 | Hexadecanoic acid, methyl ester | 112 - 39 - 0 | oily, waxy, fatty, orris | C17H34O2 | 1920.6 | |

| 76.73 | palmitic acid | 57 - 10 - 3 | waxy, fatty | C16H32O2 | 1960.3 | |

| 80.33 | linoleic acid | 60 - 33 - 3 | - | C18H32O2 | 2138.8 | |

| 81.04 | Linoleic acid ethyl ester | 544-35-4 | mild, fatty, fruity oily | C20H36O2 | 2527.4 | 2139.1 |

| 80.36 | Linolelaidic acid, methyl ester | 2566-97-4 | - | C19H34O2 | 2140.1 | |

| Furan | ||||||

| 18.88 | 2-pentyl furan | 3777 - 69 - 3 | fruity, green, earthy, beany, vegetable, metallic | C9H14O | 1234.0 | |

| 19.35 | 2-propanoyl furan | 3194-15-8 | fruity | C7H8O2 | 998.0 | |

| 20.59 | 2,5-dimethyl-3(2H)-furanone | 3188 - 00 - 9 | sweet, solvent, bready, buttery, nutty | C5H8O2 | 1261.0 | <810 |

| 34.09 | Furfural | 98 - 01 - 1 | sweet, woody, almond, bread baked | C5H4O2 | 1455.4 | 820.4 |

| 36.50 | Ethanone, 1-(2-furanyl) | 1192 - 62 - 7 | sweet, balsamic, almond, cocoa, caramellic, coffee | C6H6O2 | 1491.1 | 899.5 |

| 40.94 | 5-methyl furfural | 620 - 02 - 0 | spicy, caramellic, maple | C6H6O2 | 1562.7 | 952.1 |

| 42.39 | 2,2’-Bifuran | 5905 - 00 - 0 | - | C8H6O2 | 1586.5 | |

| 46.59 | 2-Furanmethanol | 98 - 00 - 0 | alcoholic, chemical, musty, sweet, caramellic, bready, coffee | C5H6O2 | 1656.4 | 852.3 |

| 47.59 | Furan, 2-(2-furanylmethyl)-5-methyl | 13678 - 51 - 8 | C10H10O2 | 1673.2 | ||

| 58.26 | (2E)-3-(2-furyl)-2-methyl-2-propenal | 108576 - 21 - 2 | C8H8O2 | 1862.6 | ||

| 80.67 | 5-hydroxymethylfurfural | 67 - 47 - 0 | fatty, buttery, musty, waxy, caramellic | C6H6O3 | 2509.6 | 1229.2 |

| Ketone | ||||||

| 3.42 | 2-pentanone | 107-87-9 | sweet, fruity, ethereal, winey, banana, woody | C5H10O | <810 | |

| 5.21 | 1-hydroxy-2-butanone | 5077 - 67 - 8 | sweet, coffee, musty, grain, malty, butterscotch | C4H8O2 | <810 | |

| 5.99 | 2,3-butanedione | 431 - 03 - 8 | buttery, sweet, creamy, pungent, caramellic | C4H6O2 | 1014.0 | |

| 6.56 | 2-hidroxi-3-pentanone | 5704 - 20 - 1 | truffle, earthy, nutty | C5H10O2 | <810 | |

| 9.14 | 2,3-pentanedione | 600-14-6 | buttery, nutty, toasted, caramellic, buttery | C5H8O2 | 1082.4 | <810 |

| 12.20 | 3-penten-2-one | 3102 - 33 - 8 | - | C5H8O | 1134.3 | |

| 12.81 | 2,3-hexanedione | 3848 - 24 - 6 | sweet, creamy, caramellic, buttery, fruity, jammy | C6H10O2 | 1143.6 | |

| 12.33 | Ethanone, 1-cyclopropyl | 765 - 43 - 5 | - | C5H8O | 1136.3 | |

| 12.97 | 2,4-dimethyl-3-pentanone | 565 - 80 - 0 | - | C7H14O | 1146.1 | |

| 13.38 | 3,4-hexanedione | 4437 - 51 - 8 | buttery, almond, toasted, almond, nutty, caramellic | C6H10O2 | 1152.4 | |

| 20.99 | 1,2-cyclopentanedione, 3-methyl | 765 - 70 - 8 | sweet, caramellic, maple, sugar, coffee, woody | C6H8O2 | 1020.0 | |

| 22.21 | Acetoin | 513 - 86 - 0 | sweet, buttery, creamy, dairy, milky, fatty | C4H8O2 | 1281.6 | |

| 38.29 | 2,3-dimethyl-2-cyclopenten-1-one | 1121 - 05 - 7 | - | C7H10O | 1519.3 | |

| 38.55 | 3,3-dimethyl-2-butanone | 75 - 97 - 8 | - | C6H12O | 1523.6 | |

| 55.28 | (E)-β-damascenone | 23726 - 93 - 4 | apple, rose, honey, tobacco, sweet | C13H18O | 1807.5 | |

| 59.43 | 2-cyclopenten-1-one, 3-ethyl-2-hydroxy | 21835 - 01 - 8 | Sweet, brown, caramellic, maple, brown sugar, rum, whiskey | C7H10O2 | 1884.1 | 1111.8 |

| 59.93 | (E)-furfural acetone | 41438 - 24 - 8 | - | C8H8O2 | 1893.2 | |

| 65.04 | 4-hydroxy-3-methyl acetophenone | 876 - 02 - 8 | - | C9H10O2 | 1991.3 | |

| 67.24 | Furaneol | 3658 - 77 - 3 | sweet, cotton, candy, caramellic, strawberry, sugar | C6H8O3 | 2030.2 | 1073.2 |

| Lactones | ||||||

| 36.07 | 2,5-dimethyl-3(2H)-furanone | 62873 - 16 - 9 | milky, fatty, lactonic | C6H8O2 | 1484.8 | |

| 44.02 | Butyrolactone | 96 - 48 - 0 | creamy, oily, fatty, caramellic | C4H6O2 | 1613.3 | 895.6 |

| 63.04 | Maltol | 118 - 71 - 8 | sweet, caramellic, cotton, candy, jammy, fruity, bread, baked | C6H6O3 | 1952.8 | 1102.6 |

| 68.53 | 2(3H)-furanone, 5-acetyldihydro | 29393 - 32 - 6 | - | C6H8O3 | 2052.6 | |

| 76.37 | 4H-pyran-4-one, 2,3-dihydro-3,5-dihydroxy-6-methyl | 28564 - 83 - 2 | - | C6H8O4 | 2275.1 | 1142.3 |

| N-heterocycle | ||||||

| 13.07 | 1-methyl pyrrole | 96 - 54 - 8 | smoky, woody, herbal | C5H7N | 1147.6 | |

| 15.06 | Pyridine | 110 - 86 - 1 | sour fishy, ammoniacal | C5H5N | 1178.0 | <810 |

| 22.16 | 1H-pyrrole-2-carboxaldehyde, 1-ethyl | 2167 - 14 - 8 | burnt, roasted, smoky | C7H9NO | 1035.5 | |

| 41.49 | Piracetam | 7491-74-9 | - | C6H10N2O2 | 1299.9 | |

| 45.62 | Ethanone, 1-(1-methyl-1H-pyrrol-2-yl)- | 932 - 16 - 1 | earthy | C7H9NO | 1640.1 | |

| 48.23 | 1-ethyl-2-pyrrolidinone | 2687 - 91 - 4 | - | C6H11NO | 1683.9 | |

| 49.81 | 4(H)-pyridine, N-acetyl | 67402 - 83 - 9 | green, nut, skin, sulfurous, burnt, cocoa, corn | C7H9NO | 1710.9 | |

| 62.59 | 2-methyl quinoxaline | 7251 - 61 - 8 | toasted, coffee, nutty, fruity | C9H8N2 | 1944.3 | |

| 63.46 | 2-acetyl pyrrole | 1072 - 83 - 9 | musty, nutty, coumarinic | C6H7NO | 1960.9 | 1059.2 |

| 64.18 | 4(1H)-quinazolinone | 491 - 36 - 1 | - | C8H6N2O | 1974.8 | |

| 66.19 | 1H-pyrrole-2-carboxaldehyde | 1003 - 29 - 8 | musty, beefy, coffee | C5H5NO | 2012.1 | 1014.1 |

| 66.55 | 2-pyrrolidinone | 616 - 45 - 5 | - | C4H7NO | 2018.4 | |

| 71.02 | 1H-pyrrole-2-carboxaldehyde, 1-methyl | 1192 - 58 - 1 | - | C6H7NO | 2095.7 | |

| 73.62 | Caffeine | 58 - 08 - 2 | - | C8H10N4O2 | 2409.8 | 1832.5 |

| 79.13 | 3-pyridinol | 109 – 00 - 2 | - | C5H5NO | 2425.4 | |

| 79.57 | Indole | 120 - 72 - 9 | pungent, naphthyl, fecal, animal, musty | C8H7N | 2449.9 | 1283.5 |

| Organic acids | ||||||

| 18.43 | Crotonic acid | 638 - 10 - 8 | - | C7H12O2 | 1227.6 | |

| 34.60 | Acetic acid | 64 - 19 - 7 | - | C2H4O2 | 1463.0 | <810 |

| 43.89 | 4-hydroxybutyric acid | 591 - 81 - 1 | - | C4H8O3 | 1611.1 | |

| 48.22 | isovaleric acid | 503 - 74 - 2 | Cheese, dairy, acidic, sour, pungent, | C5H10O2 | 1683.8 | 894.1 |

| Phenol | ||||||

| 13.95 | p-cresol | 106 - 44 - 5 | - | C7H8O | 1161.0 | |

| 38.99 | 2-acetylresorcinol | 699 - 83 - 2 | - | C8H8O3 | 1264.9 | |

| 66.74 | 4-ethyl guaiacol | 2785 - 89 - 9 | spicy, smoky, bacon, phenolic, clove | C9H12O2 | 2021.7 | |

| 74.52 | 2-methoxy-4-vinyl phenol | 7786 - 61 - 0 | spicy, clove, carnation, phenolic, peppery, smoky, woody, powdery | C9H10O2 | 2191.2 | 1307.1 |

| 77.24 | 2,4-di-tert-butylphenol | 96-76-4 | - | C14H22O | 2318.2 | |

| Pyrazine | ||||||

| 13.06 | 4,6-dimethylpyrazine | 1558 - 17 - 4 | - | C6H8N2 | 909.07 | |

| 17.25 | Pyrazine | 290 – 37 - 9 | pungent, sweet, corn, roasted, hazelnut | C4H4N2 | 1210.6 | <810 |

| 18.87 | 2-ethyl-3-methylpyrazine | 15707 - 23 - 0 | nutty, peanut, musty, corn, raw, earthy, bready | C7H10N2 | 991.3 | |

| 20.47 | 2-methylpyrazine | 109 - 08 - 0 | nutty, cocoa, roasted, chocolate, peanut, green | C5H6N2 | 1256.7 | 811.6 |

| 24.10 | 2,5-dimethylpyrazine | 123 - 32 - 0 | cocoa, roasted, nutty, beefy, roasted, beefy, woody, grassy, medicinal | C6H8N2 | 1308.8 | 903.0 |

| 24.56 | 2,6-dimethylpyrazine | 108 - 50 - 9 | ethereal, cocoa, nutty, roasted, meaty, roasted, meaty, beefy, brown, coffee, buttermilk | C6H8N2 | 1315.6 | 903.22 |

| 25.01 | Ethylpyrazine | 13925 - 00 - 3 | peanut butter musty, nutty, woody, roasted, cocoa | C6H8N2 | 1322.1 | 905.3 |

| 25.70 | 2,3-dimethylpyrazine | 5910 - 89 - 4 | nutty, nut, skin, cocoa, peanut, butter, coffee, walnut, caramellic, roasted | C6H8N2 | 1332.2 | |

| 27.53 | 2-acetyl-3-methylpyrazine | 23787 - 80 - 6 | nutty, nut, flesh, hazelnut, roasted | C7H8N2O | 1107.1 | |

| 28.40 | 2-ethyl-6-methylpyrazine | 13925 - 03 - 6 | roasted, potato | C7H10N2 | 1371.7 | 988.1 |

| 28.74 | 2-ethyl-5-methylpyrazine | 13360 - 64 - 0 | coffee, beany,, nutty,, grassy, roasted | C7H10N2 | 1376.7 | 991.0 |

| 29.52 | 2,3,5-trimethylpyrazine | 14667 - 55 - 1 | nutty, nut, skin, earthy, powdery, cocoa, potato, baked potato, peanut, roasted peanut, hazelnut, musty | C7H10N2 | 1388.1 | 993.2 |

| 30.57 | N-propilpyrazine | 18138 - 03 - 9 | green, vegetable, nutty, hazelnut, barley, roasted, barley, corn | C7H10N2 | 1403.5 | |

| 31.91 | Vinylpyrazine | 4177 - 16 - 6 | nutty | C6H6N2 | 1423.3 | |

| 32.35 | 2,5-dimethyl-3-ethylpyrazine | 13360 - 65 - 1 | potato, cocoa, roasted, nutty | C8H12N2 | 1429.9 | 1070.2 |

| 33.16 | 2,3-diethylpyrazine | 15707 - 24 - 1 | raw, nutty, pepper, bell pepper | C8H12N2 | 1441.2 | |

| 33.39 | 2,5-diethylpyrazine | 13238 - 84 - 1 | nutty, hazelnut | C8H12N2 | 1445.2 | |

| 33.43 | 2,6-diethylpyrazine | 13067 - 27 - 1 | nutty, hazelnut | C8H12N2 | 1445.7 | |

| 33.54 | 4-methylpyrrolo [1,2-a]pyrazine | 64608 - 60 - 2 | - | C8H8N2 | 1188.8 | |

| 33.72 | 2-methyl-6-propyl pyrazine | 29444 - 46 - 0 | burnt, hazelnut, nutty | C8H12N2 | 1450.0 | |

| 35.29 | 2-methyl-6-vinyl- pyrazine | 13925 - 09 - 2 | hazelnut, nutty | C7H8N2 | 1473.2 | |

| 35.62 | 3,5-diethyl-2-methylpyrazine | 18138 - 05 - 1 | nutty, meaty, vegetable | C9H14N2 | 1478.2 | 1150.8 |

| 36.87 | 2,3,5-trimethyl-6-ethylpyrazine | 17398 - 16 - 2 | - | C9H14N2 | 1496.6 | |

| 41.95 | (1-methylethenyl) pyrazine | 38713 - 41 - 6 | caramellic, chocolate, nutty, roasted | C7H8N2 | 1579.2 | |

| 43.14 | 5H-5-methyl-6,7-dihydrocyclopentapyrazine | 23747 - 48 - 0 | earthy, potato, baked potato, peanut, roasted peanut | C8H10N2 | 1598.7 | 1126.9 |

| 45.90 | 2,3-dimethyl-5-isopentylpyrazine | 18450 - 01 - 6 | green, floral | C11H18N2 | 1645.0 | |

| 47.78 | 1-(6-Methyl-2-pyrazinyl)-1-ethanone | 22047 - 26 - 3 | roasted coffee, cocoa, popcorn | C7H8N2O | 1676.4 | |

| 48.75 | 2-methyl-5-(1-propenyl) pyrazine | 18217 - 82 - 8 | - | C8H10N2 | 1692.6 | 1180.6 |

| Terpene | ||||||

| 11.46 | 2,6-dimethyl-2-cis-6-octadiene | 2609 - 23 - 6 | - | C10H18 | 1123.0 | |

| 14.54 | β-myrcene | 123 - 35 - 3 | peppery, terpenic, spicy, balsamic, plastic | C10H16 | 1170.1 | |

| 16.24 | D-limonene | 5989 - 27 - 5 | citrus, orange, fresh, sweet | C10H16 | 1196.0 | |

| 19.03 | β-trans-ocimene | 3779 - 61 - 1 | sweet, herbal | C10H16 | 1236.2 | |

| 21.22 | limonene | 138 - 86 - 3 | citrus, herbal, terpenic, camphoreous | C10H16 | 1022.9 | |

| 20.09 | β-cis-ocimene | 3338 - 55 - 4 | warm, floral, herbal, sweet | C10H16 | 1251.2 | 1044.3 |

| 21.67 | Terpinolen | 586 - 62 - 9 | sweet, fresh, pine, citrus, woody, lemon, peel | C10H16 | 1273.9 | |

| 22.82 | α-ocimene | 502 - 99 - 8 | fruity, floral, cloth, laundered, cloth | C10H16 | 1044.3 | |

| 28.04 | (E,Z)-alloocimene | 7216 - 56 - 0 | - | C10H16 | 1366.4 | |

| 33.25 | L-α-terpineol | 10482 - 56 - 1 | lilac, floral, terpenic | C10H18O | 1184.9 | |

| 34.44 | (E)-linalool oxide (furanoid) | 34995 - 77 - 2 | floral | C10H18O2 | 1460.7 | 1081.2 |

| 34.52 | (Z)-linalool oxide (furanoid) | 5989 - 33 - 3 | earthy, floral, sweet, woody | C10H18O2 | 1461.9 | 1065.6 |

| 34.85 | Carvomenthenal | 29548 - 14 - 9 | spicy, herbal | C10H16O | 1206.9 | |

| 39.76 | Linalool | 78 - 70 - 6 | citrus, orange, floral, terpenic, waxy, rose | C10H18O | 1543.3 | 1096.3 |

| 47.52 | Citral | 106 - 26 - 3 | sweet, citrus, lemon, lemon peel | C10H16O | 1672.0 | |

| 48.49 | α-terpineol | 98 - 55 - 5 | pine, terpenic, lilac, citrus, woody, floral | C10H18O | 1688.3 | 1185.2 |

| 49.07 | Geranyl formate | 105 - 86 - 2 | fresh, rose, neroli, rose, tea rose, green | C11H18O2 | 1698.0 | |

| 49.09 | cis- geranyl acetate | 141 - 12 - 8 | floral, rose, soapy, citrus, dewy, pear | C12H20O2 | 1698.4 | |

| 52.07 | Geranyl acetate | 105 - 87 - 3 | floral, rose, lavender, green, waxy | C12H20O2 | 1750.7 | |

| 54.55 | cis-geraniol | 106 - 25 - 2 | sweet, natural, neroli, citrus, magnolia | C10H18O | 1794.3 | 1224.2 |

| 56.38 | 2,6-octadien-1-ol, 2,7-dimethyl- | 22410 - 74 - 8 | - | C10H18O | 1827.9 | |

| 56.35 | 2,6-dimethyl-octa-2,6-dien-1-ol | C10H18O | 1827.3 | - | ||

| 57.21 | Geraniol | 106 - 24 - 1 | sweet, floral, fruity, rose, waxy, citrus | C10H18O | 1843.1 | 1251.9 |

| Others | ||||||

| 2.08 | 1,2-propanediamine | 78 - 90 - 0 | - | C3H10N2 | <1010 | |

| 5.36 | heptane, 2,2,4,6,6-pentamethyl- | 13475 - 82 - 6 | - | C12H26 | <1010 | |

| 34.62 | N-acetyl-L-alanine | 97 - 69 - 8 | - | C5H9NO3 | 1463.3 | |

| 40.96 | Difurfuryl ether | 4437 - 22 - 3 | coffee, nutty, earthy | C10H10O3 | 1292.60 | |

| 57.66 | Mequinol | 150 - 76 - 5 | - | C7H8O2 | 1851.5 | |

| 51.53 | (+)-δ-cadinene | 483 - 76 - 1 | thyme, herbal, woody, dry | C15H24 | 1741.3 | 1523.1 |

| 73.62 | Caprolactam | 105 - 60 - 2 | amine, spicy | C6H11NO | 2168.2 |

| sample | Fragance/ Aroma |

Flavor | Aftertaste | Acidity | Body | Balance | Uniformity | Clean Cup | Sweetness | Overall | score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 8.50 | 8.42 | 8.47 | 8.42 | 8.36 | 8.75 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 8.53 | 89.44 |

| 2 | 8.39 | 8.36 | 8.31 | 8.44 | 8.39 | 8.58 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 8.25 | 88.72 |

| 3 | 8.31 | 8.44 | 8.33 | 8.42 | 8.36 | 8.64 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 8.31 | 88.81 |

| 4 | 8.36 | 8.25 | 8.17 | 8.28 | 8.31 | 8.39 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 8.08 | 87.83 |

| 5 | 8.17 | 8.08 | 8.14 | 8.33 | 8.33 | 8.44 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 8.14 | 87.64 |

| 6 | 8.39 | 8.36 | 8.25 | 8.33 | 8.33 | 8.58 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 8.28 | 88.53 |

| 7 | 8.31 | 8.39 | 8.31 | 8.42 | 8.36 | 8.67 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 8.33 | 88.78 |

| 8 | 8.50 | 8.44 | 8.33 | 8.61 | 8.56 | 8.58 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 8.36 | 89.39 |

| 9 | 8.44 | 8.39 | 8.31 | 8.47 | 8.39 | 8.67 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 8.44 | 89.11 |

| 10 | 8.42 | 8.39 | 8.28 | 8.33 | 8.47 | 8.50 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 8.31 | 88.69 |

| 11 | 8.47 | 8.14 | 8.31 | 8.42 | 8.19 | 8.50 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 8.42 | 88.44 |

| 12 | 8.53 | 8.31 | 8.25 | 8.47 | 8.28 | 8.61 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 8.44 | 88.89 |

| 13 | 8.42 | 8.47 | 8.39 | 8.53 | 8.42 | 8.64 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 8.42 | 89.28 |

| 14 | 8.56 | 8.47 | 8.42 | 8.53 | 8.33 | 8.64 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 8.42 | 89.36 |

| 15 | 8.16 | 8.13 | 8.03 | 8.16 | 8.22 | 8.22 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 7.97 | 86.88 |

| 16 | 8.07 | 7.89 | 7.89 | 8.11 | 8.00 | 8.25 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 8.00 | 86.21 |

| Column Type | VOCs | Code a |

|---|---|---|

| Supelcowax 10 column | α-ocimene | A32 |

| Acetol | A37 | |

| 2,5-dimethyl-3(2H)-furanone | A64 | |

| Ethanone, 1-(2-furanyl) | A65 | |

| Ethanone, 1-(1-methyl-1H-pyrrol-2-yl) | A82 | |

| 1-(6-Methyl-2-pyrazinyl)-1-ethanone | A88 | |

| SH Rxi-5HT column | 2,5-dimethyl-3(2H)-furanone | A12 |

| 2-furanmethanol | A15 | |

| 2-cyclopenten-1-one, 3-ethyl-2-hydroxy | A46 | |

| 4H-pyran-4-one, 2,3-dihydro-3,5-dihydroxy-6-methyl | A48 | |

| 2-methoxy-4-vinylphenol | A67 | |

| Myristic acid, ethyl ester | A69 |

| Wilks’Lambda | F-approximation | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Column Supelcowax 10 | Canonical variate | stat | approx | p-value | R2 |

| 1 | 4.607x10-6 | 8.704 | 1.674x10-6 | 0.999 | |

| 2 | 3.124x10-3 | 2.991 | 7.408x10-3 | 0.989 | |

| 3 | 1.463x10-1 | 1.038 | 4.636x10-1 | 0.803 | |

| 4 | 4.124x10-1 | 0.838 | 5.920x10-1 | 0.640 | |

| 5 | 6.988x10-1 | 0.785 | 5.515x10-1 | 0.543 | |

| 6 | 9.908x10-1 | 0.083 | 7.794x10-1 | 0.096 | |

| Column SH Rxi-5HT | 1 | 8.505x10-6 | 7.496 | 5.960x10-6 | 0.999 |

| 2 | 1.542x10-2 | 1.666 | 1.234x10-1 | 0.941 | |

| 3 | 1.359x10-1 | 1.093 | 4.220x10-1 | 0.844 | |

| 4 | 4.738x10-1 | 0.686 | 7.122x10-1 | 0.633 | |

| 5 | 7.900x10-1 | 0.500 | 7.359x10-1 | 0.381 | |

| 6 | 9.242x10-1 | 0.738 | 4.125x10-1 | 0.275 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).