Submitted:

31 December 2025

Posted:

31 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature review

2.1. Understanding Platform in AI-Powered Fashion Curation

2.2. Fashion Curation-related Expectations and Demands of Consumers

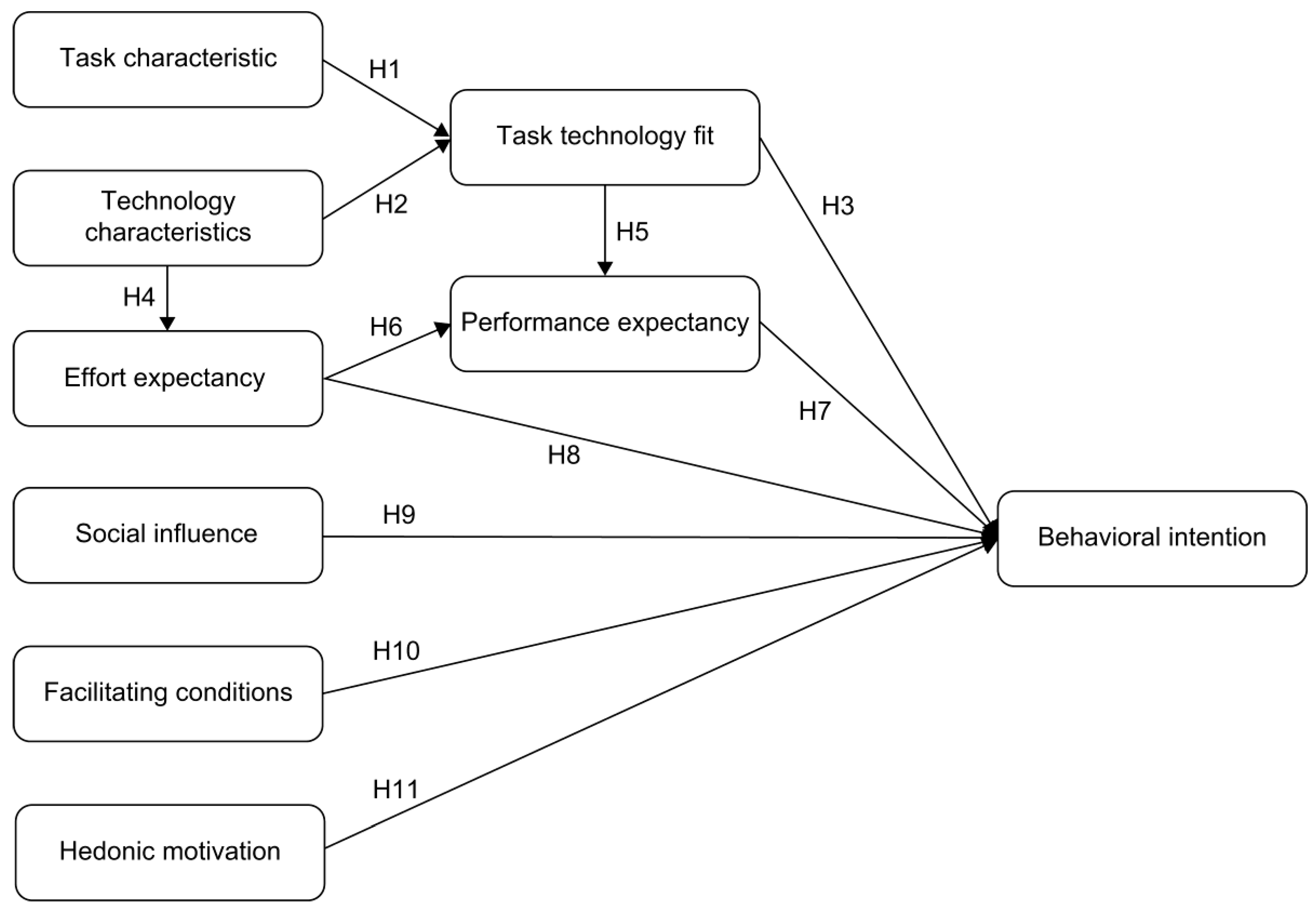

2.3. Extension of Task-Technology Fit and Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology

2.4. Hypothesis Development

3. Methods

3.1. Research Design and Data Sampling

3.2. Measurement Items and Analysis

3.3. Demographic Characteristics

4. Results

4.1. Factor and Reliability Analyses

4.2. Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analysis

4.3. Structural Equation Modeling Results

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Contributions

5.2. Practical Implications

6. Conclusion

6.1. Summary of Findings and Contributions

6.2. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AI | Artificial intelligence |

| AVE | Average variance extracted |

| BI | Behavioral intention |

| CFA | Confirmatory factor analysis |

| CFI | Comparative fit index |

| CR | Construct reliability |

| EE | Effort expectancy |

| EFA | Exploratory factor analysis |

| FC | Facilitating conditions |

| HM | Hedonic motivation |

| KMO | Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin |

| PE | Performance expectancy |

| RMSEA | Root mean square error of approximation |

| SEM | Structural equation modeling |

| SI | Social influence |

| SRMR | Standardized root mean square residual |

| TAC | Task characteristic |

| TEC | Technology characteristic |

| TTF | Task-Technology Fit |

| TLI | Tucker-Lewis index |

| UTAUT | Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology |

References

- Lee, G.; Kim, H.Y. Human vs. AI: The battle for authenticity in fashion design and consumer response. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2024, 77, 103690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christou, L. Artificial intelligence in fashion: Reshaping the entire industry. 3DLOOK. 2024. Available online: https://3dlook.ai/content-hub/artificial-intelligence-in-fashion/ (accessed on 2 October 2025).

- Sorbello, S. Heuritech: AI for fashion trends. Digit. Innov. Transform. 2022. Available online: https://d3.harvard.edu/platform-digit/submission/heuritech-ai-for-fashion-trends/ (accessed on 2 October 2025).

- Jeong, D. A study on the effect of the Internet self-efficacy of Generation MZ on use intention of luxury fashion platform—Focusing on the new exogenous mechanism of extended UTAUT. Korean Fash. Text. Res. J. 2022, 24, 577–592. [Google Scholar]

- Jeong, D. A study on the effect of consumer’s perception of digital technology on luxury fashion platform satisfaction and preference. J. Hum. Ecol. 2024, 28, 31–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, L.; Rivas-Echeverría, F.; Pérez, A.G.; Casas, E. Artificial intelligence and sustainability in the fashion industry: A review from 2010 to 2022. SN Appl. Sci. 2023, 5, 387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; Zhang, H.; Liu, L.; Zhou, D.; Xu, X.; Zhang, Z.; Yan, S. Toward intelligent design: An AI-based fashion designer using generative adversarial networks aided by sketch and rendering generators. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 2023, 25, 2323–2338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S. Artificial intelligence in the fashion and apparel industry. Tekstilec 2024, 67, 225–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, W.; Jang, S.; Kim, H.Y.; Lee, Y.; Lee, S.; Park, S. Developing an AI-based automated fashion design system: Reflecting the work process of fashion designers. Fash. Text. 2023, 10, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Zhu, Z.; Li, Y.; Cao, S.; Chen, H.; Wang, G. AI Assisted Fashion Design: A Review. Ieee Access 2023, 11, 88403–88415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, E.; Hwang, H.S. Exploring the key factors that lead to intentions to use AI fashion curation services through big data analysis. KSII Trans. Internet Inf. Syst. 2022, 16, 676–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giri, C.; Jain, S.; Zeng, X.; Bruniaux, P. A detailed review of artificial intelligence applied in the fashion and apparel industry. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 95376–95396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, G.; Kim, H. Algorithm fashion designer? Ascribed mind and perceived design expertise of AI versus human. Psychol. Mark. 2024, 42, 255–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ünlü, S.C. Enhancing user experience through AI-driven personalization in user interfaces. Hum. Comput. Interact. 2024, 8, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, E.; Kim, E.Y.; Lee, E. Modeling consumer adoption of mobile shopping for fashion products in Korea. Psychol. Mark. 2009, 26, 669–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paschen, J.; Kietzmann, J.H.; Kietzmann, T.C. Artificial intelligence (AI) and its implications for market knowledge in B2B marketing. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2019, 34, 1410–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Liu, H. Artificial intelligence-enabled personalization in interactive marketing: A customer journey perspective. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2022, 17, 663–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, J.F.; Kollat, D.T.; Blackwell, R.D. Consumer Behavior; Holt, Rinehart, and Winston: New York, NY, USA, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, J.A.; Sheth, J.N. The Theory of Buyer Behavior; John Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Goti, A.; Querejeta-Lomas, L.; Almeida, A.; Puerta, J.G.; López-de-Ipiña, D. Artificial intelligence in business-to-customer fashion retail: A literature review. Mathematics 2023, 11, 2943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.; Yan, L. Dynamic pricing and inventory strategies for fashion products using stochastic fashion level function. Axioms 2024, 13, 453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohn, K.; Sung, C.; Koo, G.; Kwon, O. Artificial intelligence in the fashion industry: Consumer responses to generative adversarial network (GAN) technology. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2020, 49, 61–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viñals, C.R.; Pretel-Jiménez, M.; Arriaga, J.L.D.O.; Pérez, A.M. The influence of artificial intelligence on Generation Z's online fashion purchase intention. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2024, 19, 2813–2827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khashan, M.A.; Elsotouhy, M.M.; Alasker, T.H.; Ghonim, M.A. Investigating retailing customers' adoption of augmented reality apps: Integrating the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology (UTAUT2) and task-technology fit (TTF). Mark. Intell. Plan. 2023, 41, 613–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baxi, C.O.; Patel, K.J.; Patel, K.M.; Patel, V.B.; Acharya, V.A. Consumers' digital wallet adoption: Integration of technology task fit and UTAUT. Int. J. Asian Bus. Inf. Manag. 2023, 15, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljarboa, S.; Miah, S.J. An integration of UTAUT and task-technology fit frameworks for assessing the acceptance of clinical decision support systems in the context of a developing country. In Proceedings of the Sixth International Congress on Information and Communication Technology, Singapore, 25–26 February 2021; Yang, X.S., Sherratt, S., Dey, N., Joshi, A., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2022; Volume 236, pp. 117–127. [Google Scholar]

- Goodhue, D.L. Development and measurement of validity of a task-technology fit instrument for user evaluations of information systems. Decis. Sci. 1998, 29, 105–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.-I.; Kim, C.-J. Delivery apps as new trend: An empirical study of the factors affecting customer continuance intention—Focused on UTAUT, TTF, and ECM. J. Korea Cult. Ind. 2021, 21, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marikyan, D.; Papagiannidis, S. Task-technology fit: A review. In TheoryHub Book; Papagiannidis, S., Ed.; Newcastle University Open Access: Newcastle, UK, 2023; Available online: http://open.ncl.ac.uk/ISBN:9781739604400 (accessed on 2 October 2025).

- Chen, L.; Jiang, M.; Jia, F.; Liu, G. Artificial intelligence adoption in business-to-business marketing: Toward a conceptual framework. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2021, 37, 1025–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, Y.; Kang, F.; Zhang, S.; Li, J. Impacts of task interdependence and equivocality on ICT adoption in the construction industry: A task-technology fit view. Archit. Eng. Des. Manag. 2021, 19, 92–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Han, X.; Lyu, T.; Ho, W.; Xu, Y.; Hsieh, T.; Zhu, L.; Zhang, L. Task-technology fit analysis of social media use for marketing in the tourism and hospitality industry: A systematic literature review. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 32, 2677–2715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Maatouk, Q.; Othman, M.; Aldraiweesh, A.; Alturki, U.T.; Al-rahmi, W.; Aljeraiwi, A.A. Task-technology fit and technology acceptance model application to structure and evaluate the adoption of social media in academia. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 78427–78440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanduhe, V.Z.; Nat, M.; Hasan, H. Continuance intentions to use gamification for training in higher education: Integrating the technology acceptance model (TAM), social motivation, and task technology fit (TTF). IEEE Access 2020, 8, 21473–21484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, C.-M. Factors determining the behavioral intention to use mobile learning: an application and extension of the UTAUT model. Front. in Psychol. 2019, 10, 1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tam, C.; Oliveira, T. Performance impact of mobile banking: Using the task-technology fit (TTF) approach. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2016, 34, 434–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedorko, I.; Bačík, R.; Gavurová, B. Effort expectancy and social influence factors as main determinants of performance expectancy using electronic banking. Banks Bank Syst. 2021, 16, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razak, F.Z.A.; Dom, M.M.; Baharudin, M.H. Impact of performance expectancy on continuance intention to use e-campus: An empirical study from Malaysia. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2021, 1793, 012014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Chen, Y.; Kittikowit, S.; Hongsuchon, T.; Chen, Y. Using unified theory of acceptance and use of technology to evaluate the impact of a mobile payment app on the shopping intention and usage behavior of middle-aged customers. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 830842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vărzaru, A.; Bocean, C.; Rotea, C.; Budică-Iacob, A. Assessing antecedents of behavioral intention to use mobile technologies in e-commerce. Electronics 2021, 10, 2231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, W.; Liang, R. Teachers’ continued VR technology usage intention: An application of the UTAUT2 model. SAGE Open 2024, 14, 21582440231220112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lestou, V.S.; Ondrusek, N.; Blajchman, M.A. Research ethics boards: The protection of human subjects. PLoS Med. 2006, 3, e472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, E.; Harrington, K.; Clark, S.; Miller, M.W. Sample size requirements for structural equation models. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2013, 73, 913–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.A.; Rhemtulla, M. Power analysis for parameter estimation in structural equation modeling: A discussion and tutorial. Adv. Methods Pract. Psychol. Sci. 2020, 4, 2515245920918253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakens, D. Sample size justification. Collabra Psychol. 2021, 8, 33267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, N.; Hadaya, P. Minimum sample size estimation in PLS-SEM: The inverse square root and gamma-exponential methods. Inf. Syst. J. 2018, 28, 227–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, W.H.; Lang, J.R. Sample composition bias and response bias in a mail survey: A comparison of inducement methods. J. Mark. Res. 1980, 17, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiner, P.M.; Cook, T.; Shadish, W.; Clark, M.H. The importance of covariate selection in controlling for selection bias in observational studies. Psychol. Methods 2010, 15, 250–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodhue, D.L.; Thompson, R.L. Task-technology fit and individual performance. MIS Q. 1995, 19, 213–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Thong, J.Y.L.; Xu, X. Consumer acceptance and use of information technology: Extending the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology. MIS Q. 2012, 36, 157–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, R.; Garg, N.; Khera, S.N. Adoption of AI-enabled tools in social development organizations in India: An extension of UTAUT model. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 893691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vongjaturapat, S.; Chaveesuk, S.; Chotikakamthorn, N.; Tongkhambanchong, S. Analysis of factor influencing the tablet acceptance for library information services: A combination of UTAUT and TTF model. J. Inf. Knowl. Manag. 2015, 14, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, 2nd ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Oğuz, A. Consumer behavior in the era of AI-driven marketing. Hum. Comput. Interact. 2024, 18, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bach, T.A.; Khan, A.; Hallock, H.P.; Beltrao, G.; Sousa, S. A systematic literature review of user trust in AI-enabled systems: An HCI perspective. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2022, 40, 1251–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedué, P.; Fritzsche, A. Can we trust AI? An empirical investigation of trust requirements and guide to successful AI adoption. J. Enterp. Inf. Manag. 2021, 35, 530–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schelble, B.G.; Lopez, J.; Textor, C.; Zhang, R.; McNeese, N.J.; Pak, R.; Freeman, G. Towards ethical AI: Empirically investigating dimensions of AI ethics, trust repair, and performance in human-AI teaming. Hum. Factors 2022, 66, 1037–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Category | 1. Need Recognition and Planning | 2. Information Search | 3. Evaluation of Alternatives | 4. Purchase Decision |

| Platform Functionality |

|

|

|

|

| AI Integration |

|

|

|

|

| Distinctive Contribution | Transitions consumers from passive browsing to active planning by offering personalized and anticipatory cues, creating a tailored shopping experience | Expedites the discovery process with AI tools that ensure the information is highly personalized and contextually relevant | Utilizes immersive technologies and data analytics to provide a tangible evaluation experience, empowering consumers to make informed comparisons | Uses real-time analytics and personalized incentives to reduce decision friction and increase conversion likelihood |

| Variable | Operational Description |

| Task Characteristics | Shopping characteristics on fashion curation platforms |

| Technology Characteristics | AI technology characteristics of fashion curation platform |

| Task-Technology Fit | How well the AI technology features match consumer needs |

| Performance Expectancy | Expectation that the AI curation platform will improve their shopping experience |

| Effort Expectancy | Ease of use and user-friendliness of the AI-based curation platform |

| Social Influence | Influence of others’ opinions or social media on platform usage |

| Facilitating Condition | Support or resources needed to leverage AI technology |

| Hedonic Motivation | Positive feelings about the overall shopping process |

| Behavioral Intention | Intent to continue using the AI-based curation platform |

| Variable | Category | Frequency | % |

| Gender | Male | 76 | 25.3 |

| Female | 224 | 74.7 | |

| Age Group | 20s | 68 | 22.7 |

| 30s | 75 | 25.0 | |

| 40s | 71 | 23.7 | |

| 50s | 86 | 28.6 | |

| Education | High school or below | 29 | 9.7 |

| In college | 26 | 8.7 | |

| College graduate | 211 | 70.3 | |

| Graduate school graduate | 34 | 11.3 | |

| Occupation | Student | 22 | 7.3 |

| General office worker | 142 | 47.3 | |

| Professional | 37 | 12.3 | |

| Public servant | 16 | 5.3 | |

| Self-employed | 21 | 7.0 | |

| Other | 62 | 20.8 | |

| Search Product Type | Clothing (tops, bottoms, underwear, etc.) | 283 | 49.6 |

| Accessories (shoes, hats, bags, etc.) | 185 | 32.5 | |

| Others (jewelry, beauty products, etc.) | 102 | 17.9 | |

| Purchase Product Type | Clothing | 279 | 54.1 |

| Accessories | 151 | 29.3 | |

| Others | 86 | 16.7 |

| Factor | Item | Factor Loading |

Eigen value |

% of explained variance (Cumulative variance %) |

Cronbach’s α |

| TTF4 | The platform meets my fashion-related needs. | .867 | 3.835 | 27.394 (27.394) |

.916 |

| TTF5 | The platform provides valuable information for my fashion decisions. | .835 | |||

| TTF2 | The platform helps me easily find the fashion information I need. | .745 | |||

| TTF3 | The platform’s features support my fashion selection process. | .727 | |||

| TTF1 | The platform effectively recommends items that match my fashion preferences. | .725 | |||

| TAC2 | Accessing detailed information about fashion items (e.g., material, size, brand) is necessary. | .780 | 3.194 | 22.814 (50.208) |

.835 |

| TAC4 | Suggestions for various outfit combinations are useful. | .752 | |||

| TAC3 | Finding fashion items that match personal preferences is essential. | .749 | |||

| TAC5 | Keeping up with the latest fashion trends is valuable. | .735 | |||

| TAC1 | Receiving recommendations for diverse clothing styles is important when using the fashion curation platform. | .708 | |||

| TEC3 | The platform provides fast response times. | .830 | 2.374 | 16.955 (67.163) |

.791 |

| TEC2 | The AI recommendation feature is accurate and reliable. | .727 | |||

| TEC4 | Personalized recommendations are offered by the platform. | .596 | |||

| TEC1 | The platform’s interface is user-friendly. | .515 | |||

| KMO measure of sampling adequacy = .922, Bartlett's test of sphericity. Chi-square X2=2335.336(df=91, p<.01)** | |||||

| PE4 | The platform increase the diversity of my fashion styles. | .801 | 3.702 | 14.807 (14.807) |

.888 |

| PE5 | The platform provides useful information for coordinating fashion items. | .760 | |||

| PE2 | The platform is effective in improving my sense of fashion style. | .743 | |||

| PE3 | The platform assists in making better fashion-related decisions. | .743 | |||

| PE1 | The platform helps me find the fashion items I want faster. | .687 | |||

| EE2 | Learning how to use the platform is simple. | .792 | 3.689 | 14.755 (29.563) |

.912 |

| EE3 | Understanding the platform’s functionality requires little effort. | .769 | |||

| EE4 | The platform has an intuitive, user-friendly interface. | .765 | |||

| EE1 | Using the platform is easy for me. | .711 | |||

| EE5 | Navigating the platform is straightforward. | .675 | |||

| SI2 | Important individuals want me to use the platform. | .774 | 3.645 | 14.580 (44.143) |

.869 |

| SI3 | Fashion experts support the use of the platform. | .756 | |||

| SI1 | People around me recommend using the platform. | .733 | |||

| SI5 | My family encourages me to use the platform. | .698 | |||

| SI4 | My friends have a positive attitude toward the platform. | .678 | |||

| HM1 | It's fun. | .781 | 3.601 | 14.405 (58.548) |

.924 |

| HM2 | It's enjoyable. | .770 | |||

| HM3 | It's very interesting. | .761 | |||

| HM5 | I feel good. | .736 | |||

| HM4 | It satisfies my needs well. | .651 | |||

| FC2 | Resources to support platform use are readily available. | .781 | 3.242 | 12.968 (71.517) |

.848 |

| FC4 | I own the necessary equipment to use the platform. | .766 | |||

| FC3 | Technical assistance for platform use is accessible. | .741 | |||

| FC5 | I can easily seek help when needed to use the platform. | .684 | |||

| FC1 | I have the knowledge required to use the platform. | .575 | |||

| KMO measure of sampling adequacy = .944, Bartlett's test of sphericity. Chi-square X2=5236.954(df=300, p<.01)** | |||||

| BI1 | I plan to shop through a fashion curation platform in the future. | .894 | 3.153 | 78.823 (78.823) |

.909 |

| BI3 | I will recommend the use of a fashion curation platform to people around me. | .892 | |||

| BI2 | I plan to continue to shop using a fashion curation platform. | .884 | |||

| BI4 | I will talk about the positive aspects of a fashion curation platform to people around me. | .881 | |||

| KMO measure of sampling adequacy = .786, Bartlett's test of sphericity. Chi-square X2=863.634(df=6, p<.01)** | |||||

| Variables | Mean | SD | Skewness | Kurtosis |

| TAC | 5.59 | .820 | -.603 | .289 |

| TEC | 5.00 | .771 | -.056 | -.290 |

| TTF | 4.99 | .869 | -.425 | .372 |

| PE | 5.08 | .845 | -.401 | .690 |

| EE | 5.35 | .914 | -.370 | -.136 |

| SI | 4.75 | .934 | -.195 | .162 |

| FC | 5.23 | .890 | -.214 | -.142 |

| HM | 5.15 | .943 | -.186 | -.225 |

| BI | 5.32 | .952 | -.263 | -.008 |

| TAC | TEC | TTF | PE | EE | SI | FC | HM | BI | |

| TAC | 1 | ||||||||

| TEC | .433** | 1 | |||||||

| TTF | .503** | .739** | 1 | ||||||

| PE | .561** | .629** | .809** | 1 | |||||

| EE | .495** | .669** | .606** | .560** | 1 | ||||

| SI | .358** | .602** | .595** | .571** | .514** | 1 | |||

| FC | .451** | .454** | .429** | .410** | .622** | .460** | 1 | ||

| HM | .444** | .594** | .631** | .619** | .643** | .583** | .570** | 1 | |

| BI | .527** | .553** | .587** | .596** | .647** | .610** | .602** | .737** | 1 |

| χ2 | df | p | TLI | CFI | RMSEA | SRMR | ||

| Value | Lower Bound |

Upper Bound |

||||||

| 1782.030 | 824 | .000 | .900 | .909 | .062 | .058 | .066 | .060 |

| TAC | TTF | TEC | PE | EE | SI | FC | HM | BI | |

| CR | .836 | .917 | .797 | .899 | .914 | .874 | .852 | .925 | .910 |

| AVE | .506 | .688 | .500 | .615 | .681 | .582 | .536 | .713 | .717 |

| Hypothesis and Path | Estimate | S.E. | β | C.R. | p | |||

| H1 | TAC | → | TTF | .231 | .067 | .209 | 3.426 | .001** |

| H2 | TEC | → | TTF | .992 | .106 | .737 | 9.360 | .001** |

| H3 | TTF | → | BI | -.039 | .161 | -.039 | -.244 | .807 |

| H4 | TEC | → | EE | .657 | .074 | .570 | 8.915 | .001** |

| H5 | TTF | → | PE | .782 | .057 | .896 | 13.649 | .001** |

| H6 | EE | → | PE | .042 | .044 | .041 | .952 | .341 |

| H7 | PE | → | BI | .285 | .182 | .249 | 1.565 | .118 |

| H8 | EE | → | BI | .058 | .083 | .050 | .704 | .481 |

| H9 | SI | → | BI | .195 | .064 | .196 | 3.056 | .002** |

| H10 | FC | → | BI | .213 | .075 | .224 | 2.836 | .005** |

| H11 | HM | → | BI | .448 | .075 | .428 | 5.943 | .001** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).