Submitted:

30 December 2025

Posted:

31 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

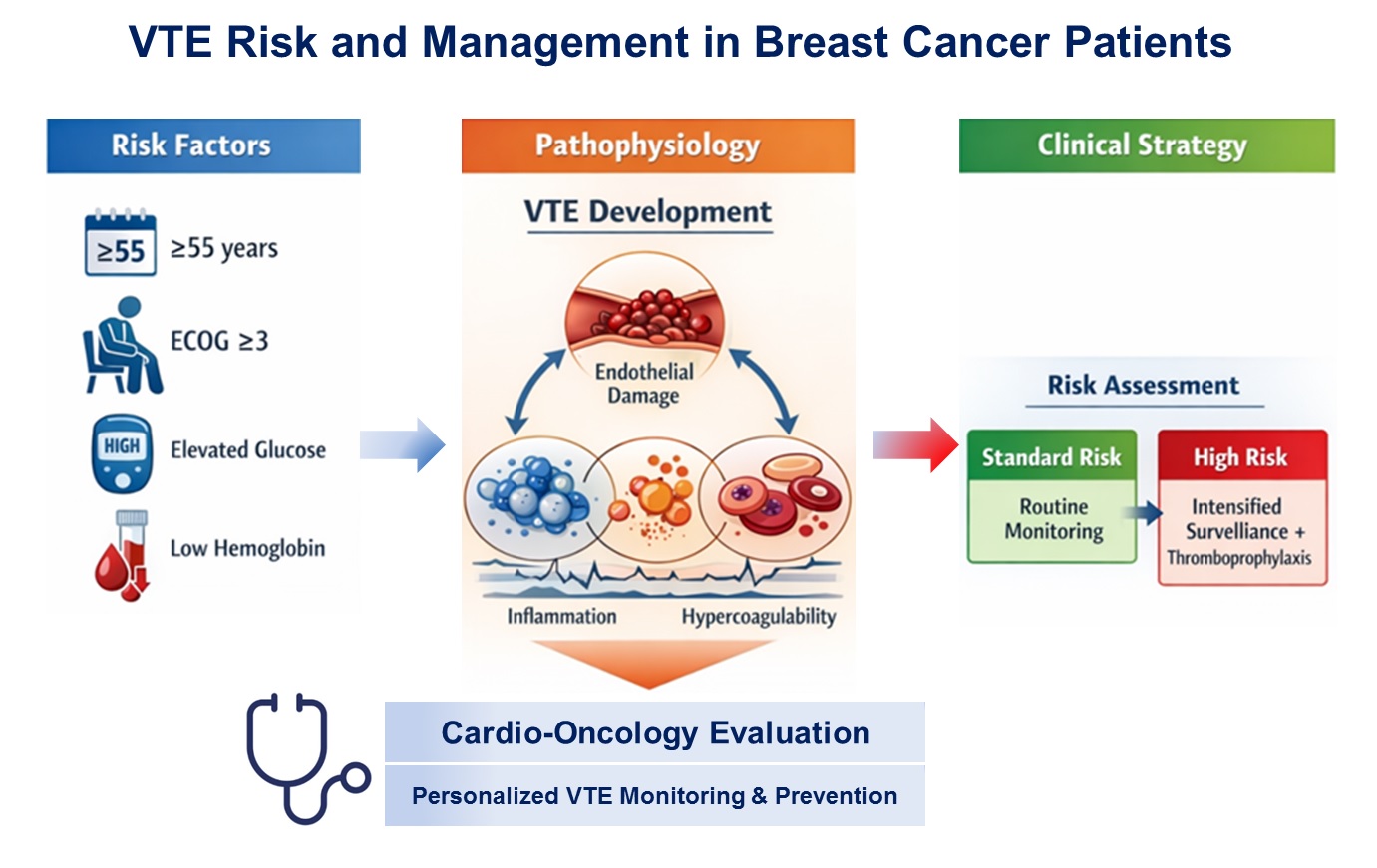

Background & Objectives: Venous thromboembolism (VTE) is a major cardiovascular complication in cancer patients and leading cause of morbidity and mortality. The aim of the study was to evaluate the incidence, timing, clinical predictors, and management of VTE in patients with breast cancer (BC), undergoing oncological therapy, and to propose a risk-adapted strategy for thrombosis monitoring and prevention. Methods: In this retrospective single-center study, 116 women with histologically confirmed BC (stages I–IV) treated between 2021 and 2024 were included. Patients were divided according to the occurrence of objectively confirmed VTE. Clinical characteristics, comorbidities, laboratory parameters, cancer-related factors, and treatment modalities were analyzed. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were performed to identify independent predictors of VTE. Results: VTE occurred in 25 patients (21.6%), predominantly within the first 12 months after cancer diagnosis. Patients who developed VTE were significantly older and more frequently had hypertension, dyslipidemia, hyperglycemia, anemia, and leukocytosis. Multivariate analysis identified age≥55 years, poor performance status (ECOG ≥3), and elevated glucose level as independent predictors of VTE. Deep vein thrombosis of the lower and upper extremities was the most common manifestation (52%), while pulmonary embolism was present in 24% of cases, either alone or in combination (20%). Direct oral anticoagulants were the most frequently used long-term anticoagulant therapy. Conclusions: VTE is a clinically relevant and relatively frequent complication in patients with BC, particularly during the early period of anticancer treatment. Patient-related and metabolic factors play a key role in thrombosis risk, underscoring the need for individualized, risk-adapted approaches to VTE prevention and monitoring in these populations.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Study Endpoint and Group Stratification

2.3. Definition and Diagnosis of VTE

2.4. Clinical and Cardiovascular Assessment

2.5. Laboratory Assessment

2.6. Assessment of Cardiovascular Risk Factors and Comorbidities

2.7. Anticoagulant Therapy

2.8. Statistical analysis

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristic of the Study Population

3.2. Incidence of Venous Thromboembolism

3.3. Predictors of Venous Thromboembolism

3.4. Risk-Adapted Monitoring and Prevention Strategy

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BC | Breast cancer |

| VTE | Venous thromboembolism |

| DVT | Deep vein thrombosis |

| PE | Pulmonary embolism |

| PH | Pulmonary hypertension |

| CAT | Cancer associated thrombosis |

| CCT | Comprehensive antitumor therapy |

| CT | Chemotherapy |

| RT | Radiation therapy |

| BMI | Body mass index |

| CAD | Coronary artery disease |

| DM | Diabetes mellitus |

| DOAC | Direct oral anticoagulants |

| LMWH | Low molecular weight heparin |

References

- Wan, T.; Song, J.; Zhu, D. Cancer-associated venous thromboembolism: a comprehensive review. Thrombosis J 2025, 23(1), 35. [Google Scholar]

- Cancer in Ukraine 2022-2023: Incidence, mortality, prevalence and other relevant statistics. Bulletin of the National Cancer Registry of Ukraine 2024, 25, 130 p.

- Razouki, ZA; Ali, NT; Nguyen, VQ; Escalante, CP. Risk factors associated with venous thromboembolism in breast cancer: a narrative review. Support Care Cancer 2022, 30(10), 8589–8597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirwan, CC; Blower, EL. Contemporary breast cancer treatment-associated thrombosis. Thromb Res 2022, 213, S8–S15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubovszky, G; Kocsis, J; Boér, K; Chilingirova, N; Dank, M; Kahán, Z; Kaidarova, D; Kövér, E; Krakovská, BV; Máhr, K; et al. Systemic Treatment of Breast Cancer. 1st Central-Eastern European Professional Consensus Statement on Breast Cancer. Pathol Oncol Res 2022, 28, 1610383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Key, NS; Khorana, AA; Kuderer, NM; Bohlke, K; Lee, AYY; Arcelus, JI; Wong, SL; Balaban, EP; Flowers, CR; Francis, CW; et al. Venous Thromboembolism Prophylaxis and Treatment in Patients With Cancer: ASCO Guideline Update. J Clin Oncol 2023, 41(16), 3063–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gradishar, WJ; Moran, MS; Abraham, J; Abramson, V; Aft, R; Agnese, D; Allison, KH; Anderson, B; Bailey, J; Burstein, HJ; et al. Breast Cancer, Version 3.2024, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2024, 22(5), 331–57. [Google Scholar]

- Falanga, A; Ay, C; Di Nisio, M; Gerotziafas, G; Jara-Palomares, L; Langer, F; Lecumberri, R; Mandala, M; Maraveyas, A; Pabinger, I; et al. ESMO Guidelines Committee. Venous thromboembolism in cancer patients: ESMO Clinical Practice Guideline. Ann Oncol 2023, 34(5), 452–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overvad, TF; Ording, AG; Nielsen, PB; Skjøth, F; Albertsen, IE; Noble, S; Vistisen, AK; Gade, IL; Severinsen, MT; Piazza, G; Larsen, TB. Validation of the Khorana score for predicting venous thromboembolism in 40 218 patients with cancer initiating chemotherapy. Blood Adv 2022, 6(10), 2967–2976. [Google Scholar]

- Mulder, FI; Candeloro, M; Kamphuisen, PW; Di Nisio, M; Bossuyt, PM; Guman, N; Smit, K; Büller, HR; van Es, N. CAT-prediction collaborators. The Khorana score for prediction of venous thromboembolism in cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Haematologica 2019, 104(6), 1277–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maesaka, JY; Reis, YN; Elias, LM; Akerman, D; Baracat, EC; Filassi, JR. Venous thromboembolism incidence in postoperative breast cancer patients. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 2023, 78, 100229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ikeda, S; Yamashita, Y; Morimoto, T; Chatani, R; Kaneda, K; Nishimoto, Y; Ikeda, N; Kobayashi, Y; Ikeda, S; Kim, K; et al. Association Between White Blood Cell Counts at Diagnosis and Clinical Outcomes in Venous Thromboembolism - From the COMMAND VTE Registry-2. Circ J 2025, 89(5), 592–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douce, DR; Holmes, CE; Cushman, M; MacLean, CD; Ades, S; Zakai, NA. Risk factors for cancer-associated venous thromboembolism: The venous thromboembolism prevention in the ambulatory cancer clinic (VTE-PACC) study. J Thromb Haemost 2019, 17(12), 2152–59. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Carmona-Bayonas, A; Gómez, D; Martínez de Castro, E; Pérez Segura, P; Muñoz Langa, J; Jimenez-Fonseca, P; Sánchez Cánovas, M; Ortega Moran, L; García Escobar, I; Rupérez Blanco, AB; et al. A snapshot of cancer-associated thromboembolic disease in 2018–2019: First data from the TESEO prospective registry. Eur J Intern Med 2020, 78, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Walker, AJ; West, J; Card, TR; Crooks, C; Kirwan, CC; Grainge, MJ. When are breast cancer patients at highest risk of venous thromboembolism? A cohort study using English health care data. Blood 2016, 127(7), 849–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, UT; Walker, AJ; Baig, S; Card, TR; Kirwan, CC; Grainge, MJ. Venous thromboembolism and mortality in breast cancer: cohort study with systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Cancer 2017, 17(1), 747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand, JS; Hedayati, E; Bhoo-Pathy, N; Bergh, J; Hall, P; Humphreys, K; Ludvigsson, JF; Czene, K. Time-dependent risk and predictors of venous thromboembolism in breast cancer patients: A population-based cohort study. Cancer 2017, 123(3), 468–75. [Google Scholar]

- Girardi, L; Wang, TF; Ageno, W; Carrier, M. Updates in the Incidence, Pathogenesis, and Management of Cancer and Venous Thromboembolism. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2023, 43(6), 824–31. [Google Scholar]

- Park, JH; Ahn, SE; Kwon, LM; Ko, HH; Kim, S; Suh, YJ; Kim, HY; Park, KH; Kim, D. The Risk of Venous Thromboembolism in Korean Patients with Breast Cancer: A Single-Center Experience. Cancers 2023, 15, 3124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harder, EM; Desai, O; Marshall, PS. Clinical Probability Tools for Deep Venous Thrombosis, Pulmonary Embolism, and Bleeding. Clin Chest Med 2018, 39(3), 473–482. [Google Scholar]

- Ioffe, D; Bhatia-Patel, SC; Gandhi, S; Hamad, EA; Dotan, E. Cardiovascular Concerns, Cancer Treatment, and Biological and Chronological Aging in Cancer: JACC Family Series. JACC CardioOncol 2024, 6(2), 143–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drăgan, A; Drăgan, AŞ. Novel Insights in Venous Thromboembolism Risk Assessment Methods in Ambulatory Cancer Patients: From the Guidelines to Clinical Practice. Cancers 2024, 16, 458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez Cánovas, M; López Robles, J; Adoamnei, E; Cacho Lavin, D; Diaz Pedroche, C; Coma Salvans, E; Quintanar Verduguez, T; García Verdejo, FJ; Cejuela Solís, M; García Adrián, S; et al. Thrombosis in breast cancer patients on cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors: Survival impact and predictive factors. A study by the Cancer and Thrombosis Group of the Spanish Society of Medical Oncology (SEOM). Eur J Intern Med 2024, 130, 98–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozhukhov, S; Dovganych, N. Thromboembolism in Patients with Cancer: A Practical Guide to Recurrent Events. Rev Cardiovasc Med 2024, 25(11), 406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakai, NA; Walker, RF; MacLehose, RF; Adam, TJ; Alonso, A; Lutsey, PL. Impact of anticoagulant choice on hospitalized bleeding risk when treating cancer-associated venous thromboembolism. J Thromb Haemost 2018, 16(12), 2403–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Value of the indicator (n=116) |

|---|---|

| Baseline characteristics | |

| Age, years | 53.1±1.2 |

| Patients >65 years old, n (%) | 16 (13.8) |

| Smoking, n (%) | 2 (1.7) |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 28.1±0.6 |

| Dyslipidemia, n (%) | 31 (26.7) |

| Comorbidity | |

| Coronary artery disease, n (%) | 12 (10.3) |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 3 (2.6) |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 45 (38.8) |

| Variable | VTE group (n=25) | Non- VTE group (n=91) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 63.8±1.9 | 50.2±1.3 | р<0.01 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 29.3±0.9 | 27.8±0.8 | NS |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 14 (56.0) | 31 (34.1) | р<0.01 |

| Coronary artery disease, n (%) | 4 (16.0) | 8 (8.8) | NS |

| Smoking, n (%) | 1 (4.0) | 1 (1.1) | NS |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 2 (8.0) | 1 (1.1) | NS |

| Dyslipidemia, n (%) | 10 (40.0) | 21 (23.1) | р<0.05 |

| Cancer stage, n (%) І II III |

019 (76.0) 3 (12.0) |

2 (2.2) 66 (72.5) 21 (23.1) |

|

| IV | 3 (12.0) | 2 (2.2) | |

| ECOG performance status ≥ 3 | 6 (24.0) | 14 (15.4) | NS |

| Laboratory parameters | |||

| Creatinine, μmol/L | 79.4±3.3 | 71.8±3.2 | NS |

| Total cholesterol, mmol/L | 6.1±0.1 | 5.3±0.3 | р<0.05 |

| Glucose, mmol/L | 6.4±0.7 | 5.3±0.2 | р<0.05 |

| White blood cells, ×109/L | 6.8±0.7 | 5.1±0.3 | р<0.05 |

| Hemoglobin, g/L | 114.7±3.1 | 126.2±3.2 | р<0.05 |

| Red blood cells, ×1012/L | 4.1±0.1 | 4.5±0.1 | р<0.05 |

| Hemodynamics | |||

| Systolic BP, mm Hg | 123.6±3.2 | 128.1±2.0 | NS |

| Diastolic BP, mm Hg | 80.6±12.0 | 87.4±1.6 | NS |

| Heart rate, beats/min | 85.2±2.8 | 87.2±2.0 | NS |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction, (%) | 58.1±1.2 | 61.8±0.5 | р<0.05 |

| Variable | VTE group (n=25) | Non- VTE group (n=91) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anthracycline-based chemotherapy, n (%) | 12 (48.0) | 62 (68.1) | р<0.05 |

| Cumulative anthracycline dose mg/m2 | 224.5±11.2 | 227.5±16.8 | NS |

| Trastuzumab, n (%) | 5 (20.0) | 31 (34.1) | р<0.05 |

| Radiation therapy, n (%) | 8 (32.0) | 30 (33.0) | NS |

| Endocrine therapy, n (%) | 4 (16.0) | 18 (19.8) | NS |

| Surgical treatment, n (%) | 10 (40.0) | 58 (63.7) | р<0.05 |

| Variable | Value |

|---|---|

| Type of VTE, n (%) | |

| Pulmonary embolism (PE) | 6 (24.0) |

| Deep vein thrombosis (DVT) | 12 (48.0) |

| PE + DVT | 5 (20.0) |

| Upper extremity DVT | 1 (4.0) |

| Catheter-related DVT (port-associated) | 1 (4.0) |

| Time of VTE occurrence after BC diagnosis, n (%) | |

| 0-6 months | 10 (40.0) |

| 6-12 months | 11 (44.0) |

| > 12 months | 4 (16.0) |

| D-dimer, ng/mL | 2261.1± 492 |

| Risk factors for VTE, n (%) | |

| Surgical treatment within 30 days | 2 (8.0) |

| Varicose veins / thrombophlebitis | 10 (40.0%) |

| Anticoagulant therapy, n (%) | |

| Low-molecular-weight heparin | 6 (24.0) |

| Direct oral anticoagulants | 19 (76.0) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).