Introduction

The use of herbal medicine remains widespread, particularly in developing countries where a large percentage of the population relies on traditional remedies for primary healthcare [

1]. Even in developed nations, there is growing interest in plant-based compounds as alternative or complementary therapies [

2]. However, the efficacy and safety of many traditionally used plants require rigorous scientific validation [

3].

A key mechanism of action for many medicinal plants is their antioxidant activity, often attributed to phenolic compounds and flavonoids. These compounds neutralize free radicals by donating hydrogen electrons, thereby preventing oxidative stress and cellular damage [

4]. Flavonoids, a group of polyphenolic compounds, are known for their free radical scavenging capabilities and inhibition of hydrolytic and oxidative enzymes [

5].

Nephrotoxicity is a serious adverse effect of certain drugs, including the chemotherapeutic agent cisplatin. While highly effective against various cancers, cisplatin’s clinical utility is limited by its dose-dependent kidney damage [

6]. This nephrotoxicity is partly due to the drug’s accumulation in renal tissues [

7], leading to acute kidney injury characterized by a rapid decline in function. Evidence suggests that intracellular oxidative stress is a primary mechanism underlying cisplatin-induced kidney damage [

8,

9]. Consequently, strategies to mitigate this toxicity often focus on reducing oxidative stress and inflammation using antioxidant and anti-inflammatory agents.

The pumpkin (

Cucurbita maxima), a member of the

Cucurbitaceae family, produces seeds that are a rich source of bioactive compounds. These seeds have been used in traditional medicine as diuretics, antihelminthics, and for treating prostate enlargement and kidney dysfunction [

10,

11]. Various studies have illustrated the medicinal potential of pumpkin seeds, including anti-diabetic [

12], anti-urolithic [

13], antioxidant, and anticancer properties [

14]. Given this historical use and documented bioactivity, we hypothesized that

Cucurbita maxima seed extract could protect against cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity via its antioxidant properties. This study aims to evaluate this renoprotective effect in a rat model, linking the findings to the broader context of mitigating the environmental impact of pharmaceutical pollutants.

Materials and Methods

Plant Material and Extract Preparation

Pumpkin fruits were obtained from a local market in Khartoum. The seeds were dried, reduced to a fine powder, and stored for analysis. The extraction was performed using 500 g of powder soaked in 80% ethanol for 72 hours with daily filtration [

15]. The solvent was evaporated under reduced pressure using a rotary evaporator, and the resulting extract was stored.

Phytochemical Analysis

Phytochemical screening of the methanolic pumpkin seed extract was carried out using standard qualitative methods to detect the presence of flavonoids, glycosides, alkaloids, saponins, phenolic compounds, and tannins [

16,

17,

18].

DPPH Radical Scavenging Assay

The antioxidant activity of the extract was determined using the DPPH (2,2-Diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl) radical scavenging assay [

19], with minor modifications. Briefly, test samples dissolved in DMSO were allowed to react with a DPPH solution in ethanol (300 µM) for 30 minutes at 37 °C. The decrease in absorbance was measured at 517 nm using a microplate reader. The percentage radical scavenging activity was calculated, with Propyl Gallate used as a standard. All tests were performed in triplicate.

Animals and Experimental Design

Forty adult albino rats (120-150 g) of both sexes were obtained from the Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Khartoum. They were housed under controlled temperature (22-24 °C) with free access to water and standard feed pellets and acclimatized for one week prior to the experiment. The animals were randomly divided into four groups (n=10):

Group A (Negative Control): Received food and water only.

Group B (Positive Control): Administered cisplatin intraperitoneally (IP).

Group C (Treatment): Administered pumpkin seed extract (300 mg/kg BW/day) orally for 10 days, with cisplatin IP from day 6 to 10.

Group D (Treatment): Administered pumpkin seed extract (600 mg/kg BW/day) orally for 10 days, with cisplatin IP from day 6 to 10.

Biochemical Analysis

Blood samples were collected from the ocular vein on days 0, 5, and 10. Serum was separated by centrifugation and stored at -20 °C until analysis. Serum concentrations of urea [

20], creatinine [

21], albumin [

22], and total protein [

23] were determined using standard methods.

Histopathological Examination

Kidney tissues were collected at the end of the experiment, processed routinely, embedded in paraffin, sectioned, and stained with Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) for microscopic examination.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using one-way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA). Results were expressed as mean ± standard error (SE), and a p-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Phytochemical and Antioxidant Activity

Phytochemical screening revealed the presence of abundant flavonoids (+++) and phenolic compounds (+++), with moderate levels of saponins (++) and tannins (++), and the presence of glycosides (+) and alkaloids (+). The DPPH assay demonstrated that the pumpkin seed extract possessed potent radical scavenging activity (92%), comparable to the Propyl Gallate standard (95%) (

Table 1 and

Table 2).

Table 1.

DPPH Radical Scavenging Activity of Cucurbita maxima Seed Extract. Comparison of the antioxidant activity of the pumpkin seed extract and the standard antioxidant, Propyl Gallate. The extract exhibited a high scavenging activity of 92%, comparable to the standard (95%).

Table 1.

DPPH Radical Scavenging Activity of Cucurbita maxima Seed Extract. Comparison of the antioxidant activity of the pumpkin seed extract and the standard antioxidant, Propyl Gallate. The extract exhibited a high scavenging activity of 92%, comparable to the standard (95%).

| Sample No. |

Sample code |

%RSD+SD (DPPH) |

| 1 |

Pumpkin seeds |

92%+0.01 |

| 2 |

Propel Gallate |

95%+0.01 |

Table 2.

Phytochemical Screening of Cucurbita maxima Seed Extract. Qualitative analysis revealing the presence of various bioactive compounds in the methanolic extract. (+++ = abundant, ++ = moderate, + = present).

Table 2.

Phytochemical Screening of Cucurbita maxima Seed Extract. Qualitative analysis revealing the presence of various bioactive compounds in the methanolic extract. (+++ = abundant, ++ = moderate, + = present).

| Test |

Result |

Test |

Result |

| Flavanoids |

+++ |

Saponins |

++ |

| Glycosides |

+ |

Phenolic compounds |

+++ |

| Alkaloids |

+ |

Tanins |

++ |

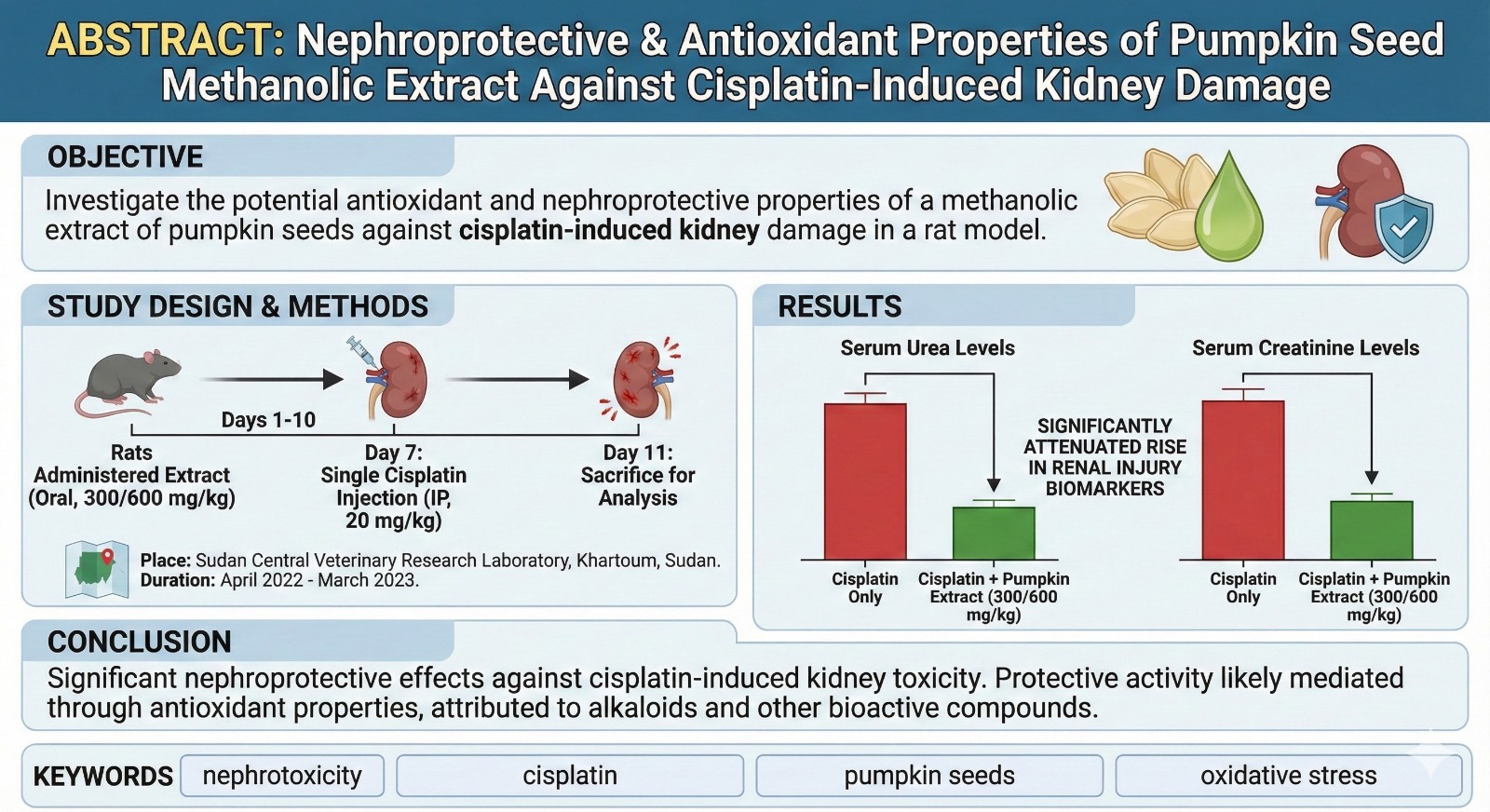

Effect on Renal Function Markers

Cisplatin administration (Group B) induced significant nephrotoxicity, marked by a substantial increase (p<0.05) in serum urea and creatinine levels by day 10 compared to the negative control (Group A). Co-treatment with the pumpkin seed extract significantly attenuated this rise in a dose-dependent manner. Group D (600 mg/kg extract) showed creatinine and urea levels much closer to the normal range than the cisplatin-only group (

Table 3,

Figure 1).

Effect on Biochemical Parameters

Cisplatin treatment (Group B) resulted in significant hypoproteinemia, hypoalbuminemia, hyperkalemia, and hyponatremia by day 10. These changes were ameliorated in the treatment groups, especially in Group D (600 mg/kg), where total protein, albumin, and electrolyte levels (sodium and potassium) were significantly restored towards normal values (

Table 4,

Figure 2 and

Figure 3).

Histopathological Findings

Kidney sections from the negative control group (A) showed normal renal histoarchitecture. In contrast, the cisplatin-only group (B) exhibited severe tubular necrosis, leukocytic infiltration, and glomerular shrinkage. Group C (300 mg/kg extract) showed moderate protection with reduced damage. Group D (600 mg/kg extract) demonstrated marked preservation of renal structure, with minimal leukocytic infiltration and near-normal appearance of glomeruli and tubules (

Figure 4).

Histological examination showed normal glomeruli with the control group whereas in the group that given Cisplatin only showed abnormal glomeruli and leucocytic infiltration and tubular degeneration, It seems that cisplatin can induce many quantitative and qualitative changes in proximal and distal convoluted tubules of nephron in rats. With the group that given 600 mg/kg BW it was found that the leucocytic infiltration Was less when compared to the group that received only cisplatin.

Discussion

This study demonstrates that the methanolic extract of Cucurbita maxima seeds provides substantial protection against cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity, an effect principally attributed to its strong antioxidant properties. This finding is particularly relevant given the increasing concern about pharmaceutical pollutants in the environment and the search for natural compounds to mitigate their toxic effects.

The phytochemical profile and high DPPH radical scavenging activity (92%) provide a clear rationale for the observed renoprotection. The abundant flavonoids and phenolic compounds are known to neutralize free radicals and chelate metal ions, thereby mitigating the oxidative stress that is a well-established primary pathway of cisplatin nephrotoxicity [

8,

9].

As expected, cisplatin administration in the positive control group induced a classic pattern of acute kidney injury, evidenced by elevated serum urea and creatinine, decreased total protein and albumin, and significant electrolyte imbalance. The histopathological evidence—showing tubular necrosis and leukocytic infiltration—corroborated the biochemical findings. Co-administration of the pumpkin seed extract, particularly at 600 mg/kg, significantly counteracted these dysfunctions. The dose-dependent restoration of renal function markers and the correction of electrolyte profiles indicate a preservation of glomerular filtration and tubular reabsorption functions.

The histology results offer direct visual confirmation of this protective effect. The reduction in leukocytic infiltration and the maintained integrity of glomeruli and tubules in the high-dose treatment group align perfectly with the biochemical data. This suggests that the antioxidant components in the extract alleviate intracellular oxidative stress in renal tissues, preventing cell death and the ensuing inflammatory response [

24].

In conclusion, our findings establish Cucurbita maxima seed extract as a promising source of nephroprotective agents against cisplatin-induced damage. While this study used a biomedical model, its implications extend to ecotoxicology, highlighting the potential of plant-derived compounds to counteract the adverse effects of persistent pharmaceutical contaminants. Future research should focus on isolating the specific active constituents and elucidating their precise molecular mechanisms of action.

Conclusions

The methanolic extract of Cucurbita maxima seeds exhibits a significant protective effect against cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity in rats. This renoprotection is mediated through the extract’s potent antioxidant properties, which are attributed to its rich content of phenolic compounds and flavonoids.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Tarig Bilal. and Sanusi M. Bello.; methodology, Tarig Bilal.; validation, Tarig Bilal., and Sanusi M. Bello.; formal analysis, Tarig Bilal.; investigation, Sanusi M. Bello.; resources, Nada M. Suliman.; data curation, Anil Bengaluru Shivappa.; writing—original draft preparation, Ahmed Hashim and Nuraddeen Ibrahim Ja’afar.; writing—review and editing, Sanusi M. Bello.; visualization, Sanusi M. Bello.; supervision, Tarig Bilal.; project administration, Tarig Bilal. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

“The animal study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Central Veterinary Research Laboratory, Khartoum, Sudan (protocol code CVRL/ERC/2023/-3577).” for studies involving animals.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data is available upon request.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the support given by the department of Biomedical Sciences, College of Dentistry, the department of Surgery and Diagnostic Sciences, College of Dentistry, and King Faisal University for their invaluable support throughout the research. During the preparation of this manuscript/study, the author(s) used Quill Bot premium for the purposes of grammar and sentence fluency and grammar error management. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no competing interest or personal relationships that could have otherwise influenced the results reported in this research.

References

- Ali, B. H.; Abdelrahman, A.; Al Suleimani, Y.; Monoj, P.; Ali, H.; Nemmar, A. Effect of concomitant treatment of circuit and melatonin on cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity in rats. Biomedical. Pharmacy. There 2020, 131 110761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, PM.; Bloom, B; Nahin, R.L. Natl, Health Stat. Report 10(12): 1-23. Chlon-Rzepa G,tal Pol J. Phamacol Rep 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Bravo, L. Polyphrnolic: Chemistry dietary sources, metabolism and nutritional significance. Nutr. Rev. 1998, 56, 317–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaili, F.; Han, S.; Quanhong, L. A review on pharmacological activities and utilization technologies of pumpkin. Plant Food Hum Nutr. 2006, 61(2), 73–80. [Google Scholar]

- Cardoso, V.M.; Solano, A.G. JP, 1973-Journal of pharmaceutical and biomedical analysis. United states patient specification 2006, 7, 230–137. [Google Scholar]

- Chonoko, G.; Rufai, B. Phytochemical screening and antibacterial activity of Cucurbita pepo (Pumpkin) against staphylococcus aureus and salmonella typhi. Bajopas 2011, 4(1), 450–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cos, p.; Ying, L.; Calorie, M.; Hu, J. P.; Cimanga, K.; Van Powell, B. Structure-activity relationship and classification of Flavonoids as inhibitors of Xanthine oxidase and superoxide scavengers. J. Natural. Prod. 1998, 61, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Credo, S. A rich source of health in minerals and protein. In GC-MS Analysis of pumpkin seeds (Cucurbita maxima); 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Doumas, B. T.; Watson, W. A.; Biggs, H. G. Albumin standard and the measurement of serum albumin by bromcresol green. Clinic Chem Acta 1971, 31(1), 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doumas, B. T.; Base, D. D.; Carter, R. J.; Peters, T. J.; Schaefer, R A. A candidate reference method for Determination of total protein in serum, development and validation. Clinic Chem. 1981, 27(10), 1642–1650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehshahri, S.; Wink, M; Afsharypuor, S.; Ashgari, G.; Mohagheghzadeh, A. Antioxidant activity of methanol is leaf extract of Morning (Forssk.) Res. Pharmacy. Sci. 2012, 7(2), 111–118. [Google Scholar]

- Harborne, J. B. Phytochemical methods 2nd edition; Chapman and Hall, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Hung, J. B. Of; Prior, R. L. The chemistry behind antioxidant capacity assays. J. Agricultural, Food, Chemistry. 2005, 53(6), 1841–1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fawcett, J.K.; Scott, J.E. A rapid and precise method for the determination of urea. J. Clinic. Pathol. 1960, 13(2), 156–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gryglewski, R.J.; Moncada, S; Palmer, R.M. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1968, 87(4), 685–694. [CrossRef]

- Murray, Jennifer. Heath benefits of pumpkin seeds Retrieved on Oct 2012http//suite101com/artice/health-benefits-of-pumpkin-a1531140. Ethnopharmacol 2012, 90(1), 89–9. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, P.; Luo, L.; Guo, J.; Liu, H.; Wang, B.; Deng, B.; Long, C. Farewell induces apostolic and oxidative stress in the fungal pathogen Penicillin expansum Mycologia. 2010, 102(2), 311–318. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez, A.; Valencia, G; Martha, F. Manual design practices design Farmacognosia y Fitoquimica: 1999 1.st edition Medellin. In University design Antiquia; Phytochemical Screening Methods; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Miliauskas, G.; Venskutonis, P. R.; Beck, T. A. Screening of radical scavenging activity of some medical and aromatic plant extracts. Food Chemistry. 2003, 24(10). [Google Scholar]

- Philips, K. M.; Reggie, D. M.; Ashraf-Khorassani, M. Phytosterol composition of nuts and seeds commonly consumed in the United States. J Agricultural Food Chemistry 2005, 53(24), 9436–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, H.; Shi, H.; Yan, Y.; Tan., X. Ammonium tetrathiomolybdate relieves oxidative stress in cisplatin-induced acute kidney injury via NRF2 signaling pathway Cell Death. Dscov 2023, 9(1), 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pabla, N.; Dong, Z. Cisplatin nephrotoxicity: mechanisms and renoprotective strategies. Kidney Int 2008, 73(9), 994–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quanhong, L.; Caili, F.; Yukui, R.; Guanghui, H.; Tongyi, C. Effects of protein-bound polysaccharide isolated from pumpkin on insulin in diabetic rats. Plant. Foods. Hum. Nutr 2005, 60(1), 13–16. [Google Scholar]

- Shimada, K; Fujikawa, K; Yamaha, K; Nakamura, T. Antioxidative properties of Xanthan on the antioxidanTion of soybean oil in cyclodextrin emulsion. J Agricultural Food Chem 1992, 40, 945–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidhuraju, P.; Becker, K. Antioxidant properties of various solvent extracts of total phenolic constituents from three different agroclimatic origins of drumstick tree (Morgana oleifera Lam.) leaves. J Agricultural Food Chemistry 2003, 51, 2144–2155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sofowora, A. Medicinal plants and Traditional Medicine in Africa; Chichester John Willem & Sons New York 256, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Sukhadev, S. H.; Susan, P. S. K.; Gennaro, L.; Devon, D R. An overview Of extraction techniques for medicinal and aromatic plants. In Extraction technologies for medicinal and aromatic plants; Sukhdev, S H, Ed.; International Centre for Science and High Technology: Trieste, Italy, 2008; pp. 25–54. [Google Scholar]

- Suphakran, V. S.; yarnon, C.; Ngunboonsri, P. The effect of pumpkin seeds on oxalocrystalluria and urinary composition of children in a hyperendemic area. American Journal of clinical nutrition 1987, 45(1), 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.; Livingston, M J.; Liu, Z. Autopathy in Kidney homeostasis and disease. Nat Rev. Nephrol. 2020, 16(9), 489–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, C.; Livingston, M J.; Safirstein, R.; Dong, Z. Cisplatin nephrotoxicity: new insight and therapeutic implication. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2023, 19(1), 53–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toora, B.D.; Rajagopal, G. Measurement of creatine by Jaffe,so reaction-determination of concentration of sodium hydroxide required of maximum colour development in standard urine and protein free filtrate of serum Indian J. Exp. Biol. 2002, 40(3), 352–4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Vickers, A.J. J Soc Integr On-col. 2007, 5(3), 125–129. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wall, M E.; Eddy, C R.; McClenna, M L; Klum, ME. Detection and estimation of steroids and sapogenins in plant tissue. 1952. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. 2003. Who guidelines on good agricultural and collection practices (GACP) for medicinal plants. World Health Organization. http://iris.who.int/handle/10665/42783. Wayne). Broutllette and Garyl. Grunewald, 1983. Synthesis and anticonvulsant activity of N-substituted lactam ring compounds (2-Piperidinone, N-[4-bromo-n-butyl]-).

- Zhang, X; Ouyang, IZ; Zhang, YS; et al. Effect of the extracts of pumpkin seeds on the urodynamics of rabbits an experimental study. Tongji Med Univ 1994, 1994:14, 2358. [Google Scholar]

Figure 1.

Renal Function Markers Day 10. Bar graph showing the concentration of serum creatinine and urea in all experimental groups at the end of the study (Day 10). Cisplatin administration (Group B) resulted in a significant increase (*p* < 0.05) in both markers compared to the negative control (Group A). Co-treatment with Cucurbita maxima seed extract at 300 mg/kg (Group C) and 600 mg/kg (Group D) attenuated this rise in a dose-dependent manner. Data are presented as mean ± standard error (SE). (n=10). *A= negative control, B= cisplatin, C= cisplatin + 300 mg/kg extract, D= cisplatin + 600 mg/kg extract.*.

Figure 1.

Renal Function Markers Day 10. Bar graph showing the concentration of serum creatinine and urea in all experimental groups at the end of the study (Day 10). Cisplatin administration (Group B) resulted in a significant increase (*p* < 0.05) in both markers compared to the negative control (Group A). Co-treatment with Cucurbita maxima seed extract at 300 mg/kg (Group C) and 600 mg/kg (Group D) attenuated this rise in a dose-dependent manner. Data are presented as mean ± standard error (SE). (n=10). *A= negative control, B= cisplatin, C= cisplatin + 300 mg/kg extract, D= cisplatin + 600 mg/kg extract.*.

Figure 2.

Serum Electrolyte Levels at Day 10. The graph depicts the concentration of sodium and potassium in all experimental groups on Day 10. Group B (cisplatin only) showed a significant electrolyte imbalance, characterized by hyperkalemia (elevated potassium) and hyponatremia (low sodium). Treatment with Cucurbita maxima seed extract, especially at 600 mg/kg (Group D), helped restore electrolyte levels towards normal. Data are presented as mean ± standard error (SE). (n=10).

Figure 2.

Serum Electrolyte Levels at Day 10. The graph depicts the concentration of sodium and potassium in all experimental groups on Day 10. Group B (cisplatin only) showed a significant electrolyte imbalance, characterized by hyperkalemia (elevated potassium) and hyponatremia (low sodium). Treatment with Cucurbita maxima seed extract, especially at 600 mg/kg (Group D), helped restore electrolyte levels towards normal. Data are presented as mean ± standard error (SE). (n=10).

Figure 3.

Temporal Changes in Serum Albumin. Line graph illustrates serum albumin levels across all groups at Day 0, Day 5, and Day 10. The negative control (Group A) maintained stable albumin levels, while the cisplatin group (Group B) showed a progressive and significant decline. Groups treated with the pumpkin seed extract (C and D) were protected against this cisplatin-induced hypoproteinemia. Data are presented as mean ± standard error (SE). (n=10).

Figure 3.

Temporal Changes in Serum Albumin. Line graph illustrates serum albumin levels across all groups at Day 0, Day 5, and Day 10. The negative control (Group A) maintained stable albumin levels, while the cisplatin group (Group B) showed a progressive and significant decline. Groups treated with the pumpkin seed extract (C and D) were protected against this cisplatin-induced hypoproteinemia. Data are presented as mean ± standard error (SE). (n=10).

Figure 4.

Representative photomicrographs of kidney sections from experimental groups (H&E stain). Group A - Negative Control: Photomicrograph showing normal renal histoarchitecture. Key structures are clearly visible: glomerulus (G), proximal convoluted tubules (PCT), and distal convoluted tubules (DCT), with intact epithelial linings and no signs of pathology. Group B - Cisplatin Control: Section from a rat treated with cisplatin alone, demonstrating severe nephrotoxic damage. Hallmark features include tubular necrosis (TN) in the proximal convoluted tubules, an abnormal glomerulus (G) with shrinkage, and significant leukocytic infiltration (LI), indicating intense inflammation and cellular injury. Group C - Cisplatin + 300 mg/kg Extract: Kidney section from a rat treated with cisplatin and the lower dose of pumpkin seed extract. The renal architecture shows moderate protection, with less severe tubular damage and reduced leukocytic infiltration compared to Panel B, though some pathological changes persist. Group D - Cisplatin + 600 mg/kg Extract: Section from a rat treated with cisplatin and the higher dose of pumpkin seed extract. This image demonstrates a marked preservation of renal structure, with minimal leukocytic infiltration and near-normal appearance of the glomerulus (G), proximal (PCT), and distal (DCT) convoluted tubules, underscoring the dose-dependent renoprotective effect of the extract.

Figure 4.

Representative photomicrographs of kidney sections from experimental groups (H&E stain). Group A - Negative Control: Photomicrograph showing normal renal histoarchitecture. Key structures are clearly visible: glomerulus (G), proximal convoluted tubules (PCT), and distal convoluted tubules (DCT), with intact epithelial linings and no signs of pathology. Group B - Cisplatin Control: Section from a rat treated with cisplatin alone, demonstrating severe nephrotoxic damage. Hallmark features include tubular necrosis (TN) in the proximal convoluted tubules, an abnormal glomerulus (G) with shrinkage, and significant leukocytic infiltration (LI), indicating intense inflammation and cellular injury. Group C - Cisplatin + 300 mg/kg Extract: Kidney section from a rat treated with cisplatin and the lower dose of pumpkin seed extract. The renal architecture shows moderate protection, with less severe tubular damage and reduced leukocytic infiltration compared to Panel B, though some pathological changes persist. Group D - Cisplatin + 600 mg/kg Extract: Section from a rat treated with cisplatin and the higher dose of pumpkin seed extract. This image demonstrates a marked preservation of renal structure, with minimal leukocytic infiltration and near-normal appearance of the glomerulus (G), proximal (PCT), and distal (DCT) convoluted tubules, underscoring the dose-dependent renoprotective effect of the extract.

Table 3.

Concentration of creatinine and urea following administration of pumpkin seed extract. Effect of Cucurbita maxima Seed Extract on Serum Creatinine and Urea. Serial measurements of creatinine and urea levels at Day 0, 5, and 10. Data are mean ± SE (n=10). Groups: A (negative control), B (cisplatin), C (cisplatin + 300 mg/kg extract), D (cisplatin + 600 mg/kg extract). * indicates a significant difference (p < 0.05) compared to Group A on the same day.

Table 3.

Concentration of creatinine and urea following administration of pumpkin seed extract. Effect of Cucurbita maxima Seed Extract on Serum Creatinine and Urea. Serial measurements of creatinine and urea levels at Day 0, 5, and 10. Data are mean ± SE (n=10). Groups: A (negative control), B (cisplatin), C (cisplatin + 300 mg/kg extract), D (cisplatin + 600 mg/kg extract). * indicates a significant difference (p < 0.05) compared to Group A on the same day.

| Groups |

|

Creatinine |

Urea |

| |

Days |

Day 0 |

Day 5 |

Day 10 |

Day 0 |

Day 5 |

Day 10 |

| Group A |

0.32±0.04 |

0.32±0.04 |

0.42±0.02 |

13.67±0.51 |

14.64±0.62 |

16.45±0.68 |

| Group B (cisplatin) |

0.34±0.04 |

0.62±0.04 |

3.62±0.34 |

14.46±0.62 |

21.24±1.21 |

38.98±0.97 |

| Group C (300) |

0.32±0.04 |

0.72±0.06 |

2.26±0.24 |

15.34±0.54 |

20.12±0.82 |

29.21±0.86 |

| Group D (600) |

0.38±0.05 |

0.54±0.12 |

0.82±0.06 |

13.64±0.54 |

18.24±0.84 |

22.46±0.92 |

Table 4.

The effect of pumpkin seeds extracts on biochemical parameters when administered with Cisplatin. Effect of Cucurbita maxima Seed Extract on Biochemical Parameters. Serial measurements of total protein, albumin, potassium, and sodium levels. Data are mean ± SE (n=10). Cisplatin treatment (Group B) caused significant hypoproteinemia, hypoalbuminemia, hyperkalemia, and hyponatremia by Day 10, which were ameliorated by co-treatment with the pumpkin seed extract.

Table 4.

The effect of pumpkin seeds extracts on biochemical parameters when administered with Cisplatin. Effect of Cucurbita maxima Seed Extract on Biochemical Parameters. Serial measurements of total protein, albumin, potassium, and sodium levels. Data are mean ± SE (n=10). Cisplatin treatment (Group B) caused significant hypoproteinemia, hypoalbuminemia, hyperkalemia, and hyponatremia by Day 10, which were ameliorated by co-treatment with the pumpkin seed extract.

| Group |

|

Total Protein |

Albumin |

Potassium |

Sodium |

| |

Days |

Day 0 |

Day 5 |

Day 10 |

Day 0 |

Day 5 |

Day 10 |

Day 0 |

Day 5 |

Day 10 |

Day 0 |

Day 5 |

Day 10 |

| Group A |

5.63±0.21 |

5.78±0.22 |

6.21±0.24 |

4.64±0.24 |

5.21±0.21 |

4.89±0.23 |

3.49±0.30 |

4.12±0.41 |

4.23±0.36 |

135.2±6.23 |

136.3±5.82 |

141.3±6.42 |

| Group B |

5.86±0.21 |

6.21±0.42 |

4.82±0.08 |

4.48±0.16 |

3.82±0.08 |

2.64±0.04 |

3.50±0.30 |

5.62±0.21 |

6.84±0.42 |

134.2±6.38 |

128.7±6.21 |

119.9±5.37 |

| Group C |

5.48±0.08 |

6.84±0.44 |

6.92±0.48 |

4.52±0.12 |

4.84±0.16 |

4.14±0.18 |

3.52±0.31 |

5.21±0.22 |

6.42±0.24 |

135.2±6.23 |

134.2±6.38 |

132.3±5.42 |

| Group D |

5.92±0.28 |

6.21±0.42 |

7.21±0.68 |

4.38±0.21 |

4.86±0.14 |

5.22±0.42 |

3.49±0.30 |

4.68±0.23 |

4.26±0.32 |

135.2±6.23 |

139.3±5.74 |

148.4±6.64 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).