1. Introduction

Insects play a crucial role in biodiversity, and their community structure can indicate the interrelationship between insect populations and the environment [

1]. Investigating the diversity of insect community structure is essential for assessing environmental quality and understanding the mechanisms underlying pest outbreaks [

2,

3]. Lepidoptera moths, in particular, exhibit high sensitivity to environmental changes. They often exhibit close associations with their host plants [

4]. Analyzing the diversity characteristics of their community structure can provide insights into the quality of their habitat [

5,

6]. The niche of an ecological species reflects the spatio-temporal distribution of a given species within a region and the functional interactions and roles of different species within the region [

7,

8]. Exploring the ecological niche of dominant species will help us understand how different dominant species utilize the environmental resources and further reveal the relationships between competing species and the coexistence patterns between different insects [

9,

10].

The Chinese Cherry (

Prunus pseudocerasus Lindl.), belonging to the genus

Prunus, is widely cultivated in southwestern and northern China [

11]. In recent years, the area dedicated to cherry cultivation in the Loess Plateau of eastern Gansu has been steadily increasing. Here, the cherry industry has become a vital component of the local agricultural economy. However, as the scale of cherry cultivation expands, the issue of pest infestation has become increasingly pronounced [

12]. Moth species, including the oriental fruit moth and leaf-roller moths, pose significant threats to cherry crops [

13,

14]. Their larvae primarily inflict damage on fruits, leaves, and young shoots, resulting in substantial economic losses [

15,

16]. The Loess Plateau region in eastern Gansu features a typical semi-arid climate, characterized by a fragile ecological environment and a relatively simple agricultural ecosystem [

17]. The climatic conditions, including drought, limited rainfall, and significant diurnal temperature fluctuations, exert specific impacts on the moth insect community structure in this region. Currently, there is a scarcity of research focusing on the moth insect community structure within cherry orchards in this region. This study conducts relevant investigations on moths in cherry orchards in the arid plateau of Gansu. The purposes are: (1) to clarify the species composition, community structure, and diversity of moths; (2) to identify the dominant groups; (3) to analyze the ecological niche width and overlap of dominant species; (4) to explore the influence of environmental temperature and humidity on the diversity of moth communities. This research constructs baseline data for insect research, helps to understand the situation of pests, and provides assistance for future pest management.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Survey Site

The Cherry Orchard is located in Longdong University, Qingyang, Gansu (107°38' E, 35°43' N). There are places like Qingyang and Pingliang on the Loess Plateau in eastern Gansu, which are important agricultural and ecological regions, with a semi-arid climate, an annual average temperature of about 10°C, and an annual average precipitation of about 500 mm [

18]. Various plants such as cherries, roses, and peonies are planted in the orchard.

2.2. Investigation Methods

Moth samples were collected using a light-trapping method from March to August 2025. A 250-W high-pressure mercury lamp and a 2 m × 2.5 m white curtain were employed to attract moths within a 3 m × 3 m area surrounding the curtain. Surveys were conducted weekly, totaling four times per month, on sunny days from 19:00 to 23:00 [

19]. All moths attracted to the screen were photographed and counted. Specimens that could not be identified in the field were captured with an insect net, transferred to collection vials, and taken to the laboratory for morphological identification [

20]. All the specimens are deposited in the Zoological Museum of Longdong University.

2.3. Diversity Analysis

The calculation formulas for each diversity index are as follows:

Shannon-Wiener diversity index (

H') [

21]:

Margalef richness index (

R) [

22]:

Simpson dominance index (

D) [

23]:

Pielou uniformity index (

J) [

24]:

Relative multiplicity (

Ra):

In the formula, pi represents the individual ratio of the i-th species, Ni is the number of individuals of the i-th species, S is the number of species, and N is the total number of individuals of all species.

2.4. Ecological Niche Analysis

The Levins niche width index (

Bi) is adopted to calculate the niche width of dominant species [

25,

26]:

Here, Bi denotes the niche width of the i-th species, pij represents the proportion of individuals of the i-th species in the j-th resource state relative to the total number of individuals of the species, and j indicates the number of resource states. A greater value of ecological niche width indicates a wider range of resource utilization by the species.

The formula for the Pianka niche overlap index (

Qij) is [

27,

28]:

where

Qij is the niche overlap index of i-th and j-th species and

pik and

pjk are the ratio of the number of i and j species individuals in k-th resource state to the number or individuals of their species. The higher the niche overlapping index, the less similar resource is being used by both species and the more interesting the competition is. The range of value of the niche overlaps index is 0-1. The larger the value, the more overlap is observed.

Qij > 0.1 is a meaningful overlap and

Qij > 0.3 is a significant overlap.

2.5. Acquisition of Environmental Factors

Two environmental and climate factors, temperature and humidity, were chosen to study their effects on the diversity of the moth insect community structure in the area. The temperature and the humidity were recorded using a temperature and atmosphere recorder (GSP-8G, Jiangsu Jingchuang Co., LTD.).

2.6. Statistical Analysis

The original data in the survey were obtained from Excel. Differences in the moths' diversity index during the seasons were calculated with a sample t-test on SPSS 22.0. For studying the dependence of the moth diversity index on the climate factors such as temperature and humidity, Pearson correlation was used. Visualizations using Origin Pro 2025 were generated.

3. Results

3.1. Moth Community Composition

A total of 79 species of moths from 10 families were collected by light-trapping in the cherry orchard during the study period(

Table 1). Geometridae was the most abundant family in terms of individuals, comprising 15 species (18.99%) and 308 individuals (43.75%), while Noctuidae had the highest species richness, with 25 species (31.65%) and 140 individuals (19.89%). Both families were present throughout each sampling month, confirming their status as the dominant taxa in the area. In contrast, only one species (1.27%) was recorded from each of the families Lecithoceridae, Sphingidae, Limacodidae, and Lasiocampidae, with low overall abundance. The relative abundance of

Semiothisa cinerearia was 32.95%, making it the dominant species in this study area. The locust inchworm was first seen in early May, and the peak of adult worms occurred in late May. The second peak period of adult insects occurred in mid-July, and they started to decline in late August. During this investigation period, the locust inchworm exhibited a multi-generation occurrence temporal dynamic characteristic, with the main occurrence peaks concentrated in the middle and late May and mid-July. This provides a scientific basis for the monitoring and control of the locust inchworm in terms of time nodes.

Moth species composition varied seasonally (

Table 2). In spring (March-May), 23 species were recorded, with Noctuidae showing the highest species richness and abundance. In summer (June-August), species richness increased to 59, and Pyralidae, Noctuidae, and Geometridae were the dominant families. These results indicated that summer supported the highest species diversity and abundance of moths, corresponding to a period of pronounced environmental and phenological change.

3.2. Analysis of Moth Insect Diversity in Different Seasons

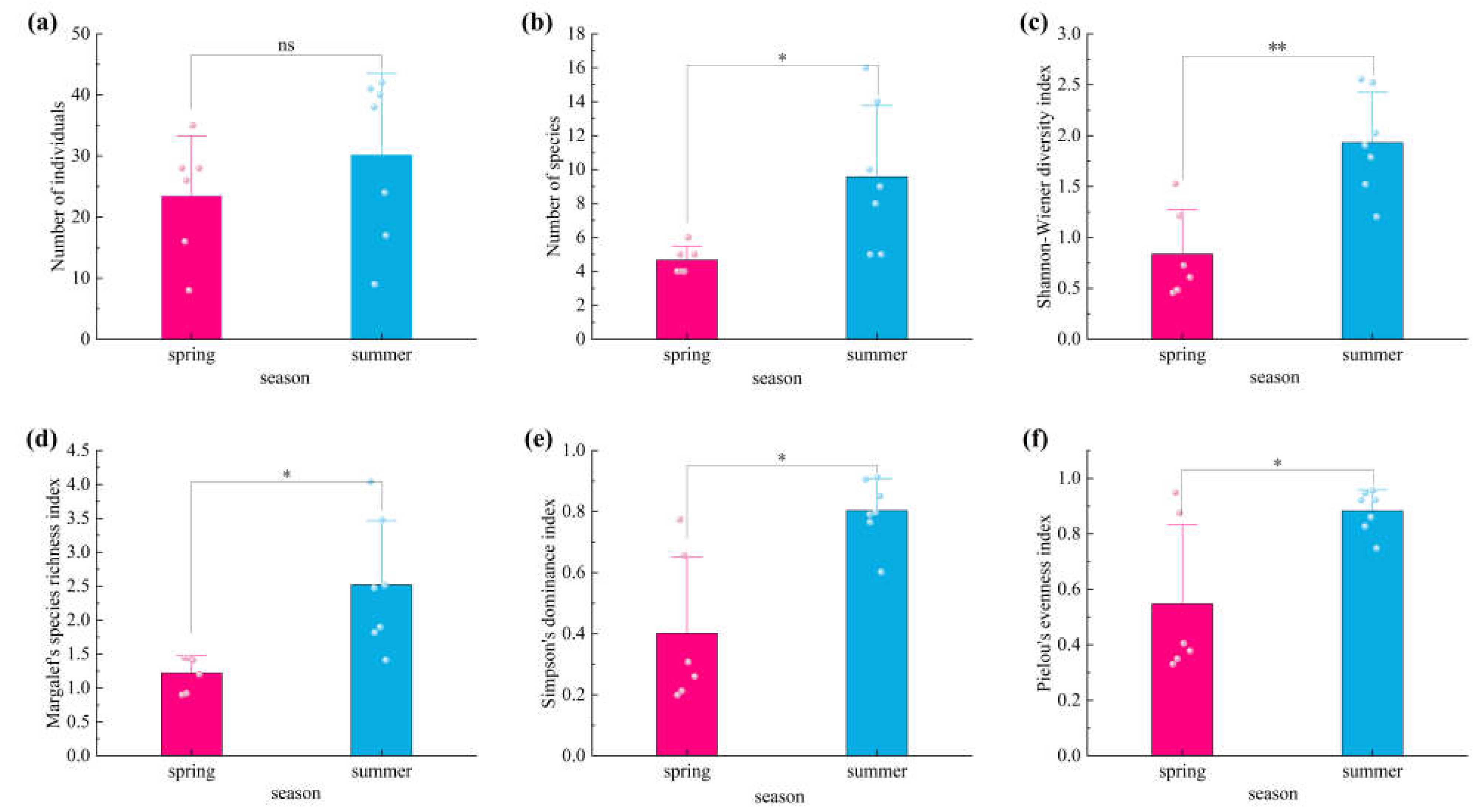

A comparison of moth insect diversity between spring and summer was illustrated (

Figure 1). Although the number of moths in summer exceeded that in spring, the difference was not statistically significant. All diversity indices were significantly higher in summer than in spring (

P < 0.05). Specifically, the Shannon–Wiener diversity index, species richness index, dominance index, and evenness index all showed significant seasonal increases in summer (

P < 0.05 for richness, dominance, and evenness;

P < 0.01 for Shannon–Wiener diversity). These results demonstrate that seasonal variation has a substantial influence on moth community diversity, richness, and dominance structure.

3.3. Temporal Niches of Moth Insects

Based on the family-level relative abundance (

Table 1), the relative abundances of five families (Geometridae, Pyralidae, Noctuidae, Tortricidae, Arctiidae) exceed 3%, which were the dominant families. Compare the temporal niche breadth (

Table 3). There were differences in the niche breadth of different families; in terms of being widespread and utilizing resources, the temporal niche of Geometridae was the widest (7.592); the temporal niche widths of the Tortriidae(3.492) and Lanternidae(3.072) were the narrowest, suggesting that the moths in these families exhibited greater temporal concentration and heightened activity during specific seasons or periods. This pattern may be linked to their reproductive cycles and the availability of food resources.

Analyzed the interspecific niche overlap of 5 dominant families, and 10 species pair combinations were obtained (

Table 3). Except for the combination of Geometridae and Tortricidae, there were obvious temporal overlaps (

Qij > 0.1) in the rest, among which 6 pairs showed high overlaps (

Qij > 0.3). The overlap degree between Pyralidae and Arctiidae was the highest, reflecting that interspecific competition was relatively intense; the overlap degree between Tortricidae and Geometridae was the lowest, indicating that the competitive effect was weak.

3.4. Relationship Between Moth Diversity and Environmental Factors

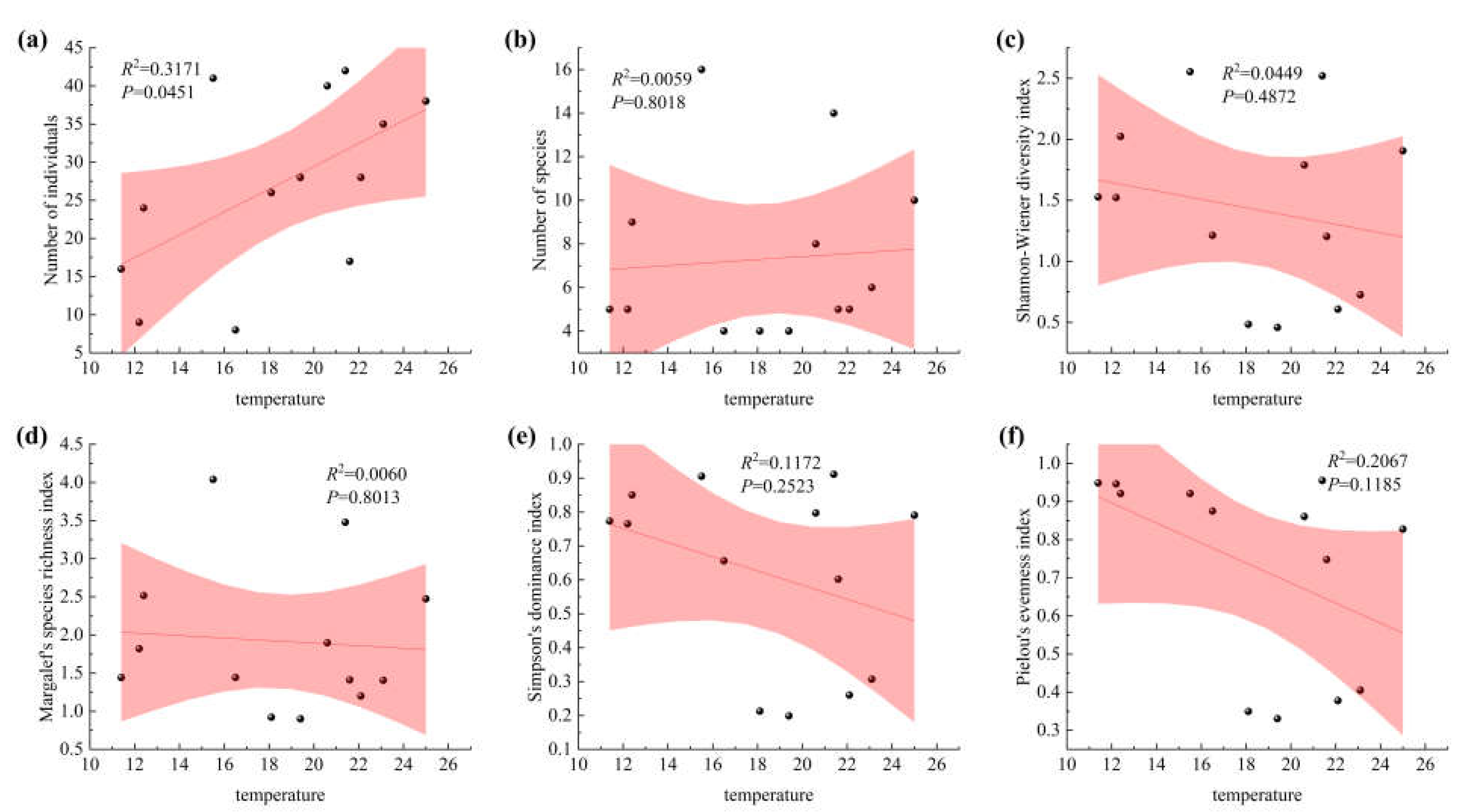

The correlations between moth community indices and environmental temperature are presented in

Figure 2. A significant positive correlation was observed between moth abundance and temperature (

P < 0.05). Species richness also increased with rising temperature. In contrast, the Shannon–Wiener diversity index, Simpson’s dominance index, and Pielou’s evenness index were all negatively correlated with temperature (

P < 0.05). These results suggest that while higher temperatures promote increases in moth abundance and species richness, they are associated with a decrease in overall community evenness and diversity. Other community indices showed no significant response to temperature variation.

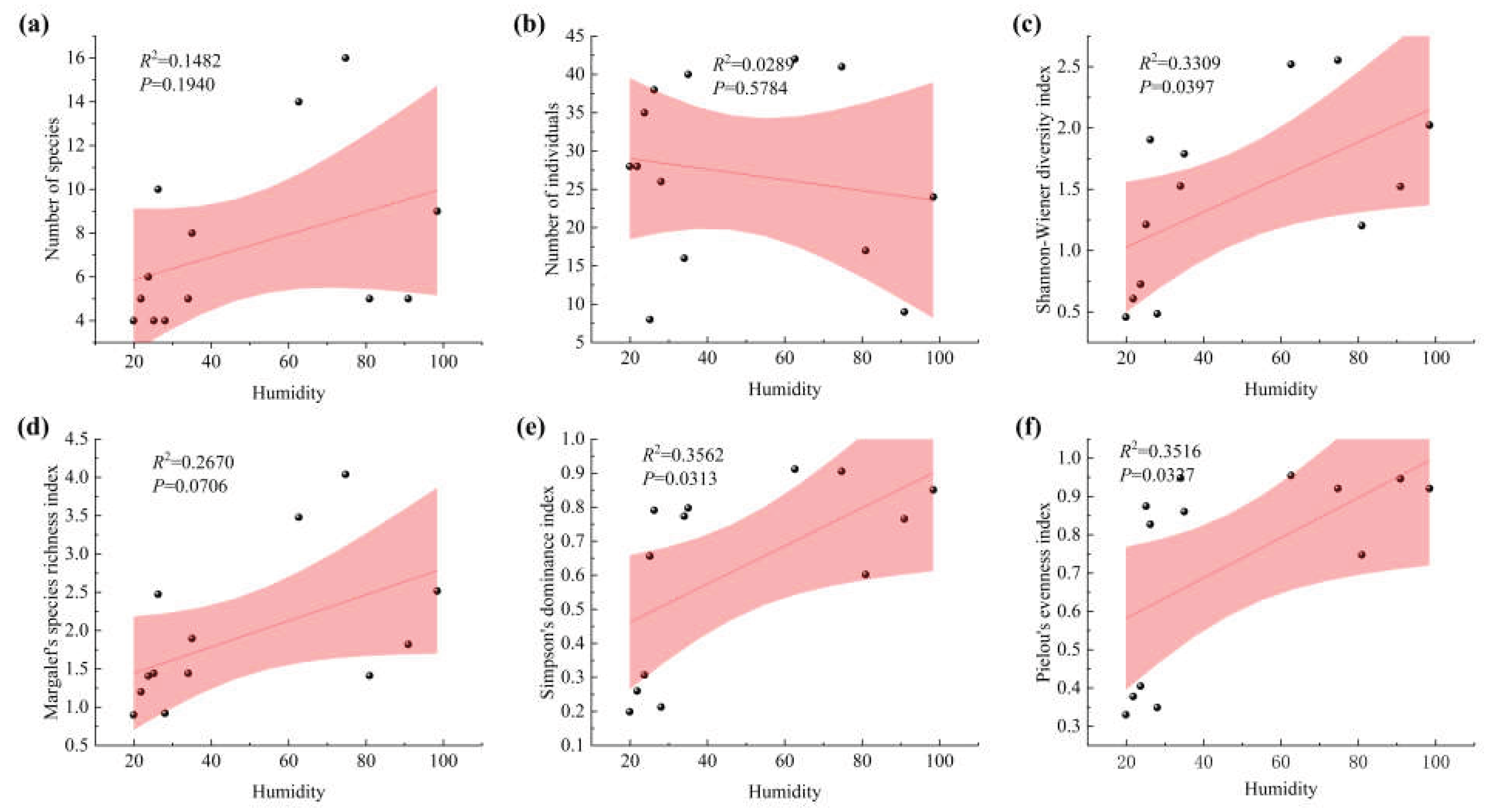

The relationships between moth community indices and humidity are shown in

Figure 3. Moth abundance was negatively correlated with humidity (

P < 0.05), whereas species richness showed a positive correlation (

P < 0.05). In addition, the Shannon–Wiener diversity index, Simpson’s dominance index, and Pielou’s evenness index were all positively correlated with humidity (

P < 0.05).

4. Discussion

A total of 79 moth species from 10 families were recorded in this study. The families Noctuidae and Geometridae displayed the highest species diversity and abundance, occurring consistently across all sampling months, confirming their dominance in the study area. This finding aligns with the community structure of moths observed in the Ziwuling Forest, which also belongs to the Loess Plateau region [

29]. Noctuids and Geometrids include many important agricultural and forestry pests, and their wide distribution and high abundance are likely linked to the availability of host plants in and around the cherry orchard [

30]. Tortricidae and Pyralidae were also commonly present in the study area; their larvae often exhibit concealed habits, such as leaf-rolling and stem-boring, complicating pest control efforts [

31]. In the study area,

S. cinerearia was dominant, and its multi-generation occurrence is in line with the known biological characteristics [

32]. There are black locust trees near the cherry orchard, which may make the population of

S. cinerearia relatively high. There were differences in moth diversity under seasonal dynamics, and the diversity of the summer community was higher than that of the spring. The changes in seasons may be affected by climate, food, and the characteristics of the insect life cycle. The temperatures of warm summers and more precipitation provide more resources for the development activities of moths [

33,

34].

The width and overlap of niches are key elements of the niche theory that affect species diversity and the stability of community structure [

35]. Quantitative evaluation of these indicators can tell how species use resources such as time in the community. Generally speaking, a larger niche width means stronger resource utilization ability, higher adaptability, and a wider taxonomic distribution [

36]. Analyzing five dominant families, the Geometridae had the widest temporal niche, suggesting that the moth insects within this group had inflicted persistent damage in the study area over an extended period. Such ability to use time resources may be associated with their multi-generational abundance of dominant species such as

S. cinerearia. The ecological niches of Tortricidae and Arctiidae were relatively narrow, and their distributions were relatively concentrated. Niche overlap further clarifies potential competitive relationships among taxa [

37]. The degree of temporal overlap between Pyralidae and Arctiidae was the highest, perhaps because their seasonal activities are relatively similar, resulting in strong interspecific competition. The degree of overlap between Tortricidae and Geometridae was the lowest. Their active periods were mostly separated throughout the year, thus reducing direct competition.

Temperature is an important factor affecting the number of insects and community diversity [

33,

38]. Moths are poikilothermic and are particularly sensitive to temperature changes, which directly affect their growth, development, and survival [

39]. The number and species diversity of moths in this study were positively correlated with temperature. Warm conditions may accelerate the metabolism of insects, shorten the development time, and also promote reproduction, thus promoting population growth [

40]. In contrast, multiple diversity indices—including the Shannon–Wiener, Simpson’s dominance, and Pielou’s evenness indices—showed negative correlations with temperature. This pattern suggests that while warming may stimulate overall moth activity, it does not benefit all species equally. Certain eurythermal species can rapidly expand their populations under higher temperatures, increasing their dominance and reducing community evenness [

41]. Consequently, although total abundance may rise, community diversity can decline when a few species become disproportionately abundant. Thus, temperature not only drives changes in insect population size but also plays a key role in restructuring community composition and influencing ecosystem stability. These findings highlight the importance of considering temperature-mediated shifts in pest dominance when designing monitoring and ecological management strategies.

Humidity also has an impact on the survival, reproduction, development, and behavior of moths [

33,

42]. In this study, the diversity, dominance, and evenness of the moth community were related to humidity. The study area is in the eastern arid plateau of Gansu, and the overall humidity is low. Relatively high humidity may create a more suitable microenvironment for moths, thereby causing changes in the distribution of community diversity and evenness.

The interaction between temperature and humidity in influencing the distribution, survival, and reproduction of moths is relatively crucial [

43]. Favorable temperature and humidity range often contribute to the growth, development, and reproduction of moths, while extreme conditions may have adverse effects on the persistence of the population [

43,

44]. Understanding these environmental drivers is important for predicting moth population dynamics and formulating effective management strategies in similar arid or semi-arid agricultural ecosystems.

5. Conclusions

From March to August 2025, the light-trapping method was used to investigate the moth community structure and diversity in the cherry orchard of the arid plateau area. A total of 79 species of moths belonging to 10 families were recorded. Among them, the Geometridae and Noctuidae families were the most abundant and had a large number, and S. cinerearia was the dominant species. The diversity of moths in summer was significantly higher than that in spring. Among the five dominant families (Geometridae, Noctuidae, Pyralidae, Arctiidae, and Tortricidae), the time niche of Geometridae was the broadest, and the time niches of Arctiidae and Tortricidae were narrower. There was an obvious time niche overlap between most families. The overlap degree between Pyralidae and Arctiidae was the highest, which means they had relatively strong potential to compete for seasonal resources. There was a positive correlation between temperature and moth abundance, and a negative correlation with community diversity indices (Shannon-Wiener, Simpson dominance, Pielou evenness). Humidity had a positive correlation with these diversity indices. The moth community structure had seasonal dynamics driven by temperature and humidity. This study provides basic data on the moth community in cherry orchards in arid plains, and also provides a scientific basis for the monitoring, prediction, and management of major pests in the local agricultural ecosystem.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.X. and Y.Y.; methodology, S.X.; software, S.X.; validation, S.X., and Y.Y.; formal analysis, S.X. and Y.Y.; investigation, Q.Y., X.Z., S.G., L.A., B.W.; resources, S.X., Y.Y., Q.Y., X.Z.; data curation, S.X., Q.Y., X.Z., S.G., L.A., B.W.; writing—original draft preparation, S.X.; writing—review and editing, S.X. and Y.Y.; visualization, S.X. and Y.Y; supervision, Q.Y. and X.Z.; project administration, S.X.; funding acquisition, S.X.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by Gansu Provincial Natural Science Foundation Project (24JRRM003), Qingyang Science and Technology Plan Project (QY-STK-2022A-023), Gansu Province Higher Education Institutions Innovation Fund Project (2020B-221) and Gansu Province Youth Doctoral Fund Project (2021QB-120).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Edgar, C.B.; Burk, T.E. A Simulation Study to Assess the Sensitivity of a Forest Health Monitoring Network to Outbreaks of Defoliating Insects. Environ Monit Assess. 2006, 122, 289–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, J.; Huang, J.; Wu, Y.; Gong, Z.; Li, H.; Zhang, G.; Duan, Y.; Li, T.; Jiang, Y. Climate Factors Associated with the Population Dynamics of Sitodiplosis Mosellana (Diptera: Cecidomyiidae) in Central China. Sci Rep. 2019, 9, 12361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, J.R.L.; Fernandes, O.A.; Higley, L.G.; Peterson, R.K.D. Do Patterns of Insect Mortality in Temperate and Tropical Zones Have Broader Implications for Insect Ecology and Pest Management? PeerJ. 2022, 10, e13340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- An, J.S.; Choi, S.W. Forest Moth Assemblages as Indicators of Biodiversity and Environmental Quality in a Temperate Deciduous Forest. Eur. J. Entomol. 2013, 110, 509–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozojević, I.; Ivković, M.; Cetinić, K.A.; Previšić, A. Peeling the Layers of Caddisfly Diversity on a Longitudinal Gradient in Karst Freshwater Habitats Reveals Community Dynamics and Stability. Insects. 2021, 12, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enkhtur, K.; Brehm, G.; Boldgiv, B.; Pfeiffer, M. Alpha and Beta Diversity Patterns of Macro-Moths Reveal a Breakpoint along a Latitudinal Gradient in Mongolia. Sci Rep. 2021, 11, 15018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brzić, I.; Brener, M.; Čarni, A.; Ćušterevska, R.; Čulig, B.; Dziuba, T.; Golub, V.; Irimia, I.; Jelaković, B.; Kavgacı, A.; et al. Different Ecological Niches of Poisonous Aristolochia Clematitis in Central and Marginal Distribution Ranges—Another Contribution to a Better Understanding of Balkan Endemic Nephropathy. Plants. 2023, 12, 3022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Psaila, B.; Lyden, D. The Metastatic Niche: Adapting the Foreign Soil. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009, 9, 285–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefan, L.M.; Gómez-Díaz, E.; Elguero, E.; Proctor, H.C.; McCoy, K.D.; González-Solís, J. Niche Partitioning of Feather Mites within a Seabird Host, Calonectris Borealis. PLoS ONE. 2015, 10, e0144728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrozzi, F.; Gonedele Bi, S.; Segniagbeto, G.H.; Pacini, N.; Fa, J.E.; Luiselli, L. Trophic Resource Use by Sympatric vs. Allopatric Pelomedusid Turtles in West African Forest Waterbodies. Biology. 2023, 12, 1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, C.; Cao, X.; Tian, T.; Hou, Q.; Wen, Z.; Qiao, G.; Wen, X. Cross-Talk between Transcriptome Analysis and Dynamic Changes of Carbohydrates Identifies Stage-Specific Genes during the Flower Bud Differentiation Process of Chinese Cherry (Prunus Pseudocerasus L.). IJMS. 2022, 23, 15562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W. Occurrence of Major Diseases and Pests of Cherries in China and Green Control Techniques. China Fruit News. 2025, 42, 70–71+74. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, H.; Zhang, R.; Li, X. Study on the Effeet of Disorientated Wire of the Oriental Fruit Moth in Cherry Orchard,2023,39(10):113-116. Chinese Agricultural Science Bulletin. 2023, 39, 113–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ze, F.; Lv, H.; Yu, Y. Occurrence and Management of Adoxophyes Orana on Large Cherry. Deciduous Fruits. 2011, 43, 51–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, W.T.; Li, J.; Ban, L.P. Genome-Wide Selective Signature Analysis Revealed Insecticide Resistance Mechanisms in Cydia Pomonella. Insects. 2021, 13, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, H.; Yu, X.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, D. Sugar–Acetic Acid–Ethanol–Water Mixture as a Potent Attractant for Trapping the Oriental Fruit Moth (Lepidoptera: Tortricidae) in Peach–Apple Mixed-Planting Orchards. Plants. 2019, 8, 401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, R.; Li, X.; Zhu, W.; Wang, K.; Guo, S.; Misselbrook, T.; Hatano, R. Effects of the Ridge Mulched System on Soil Water and Inorganic Nitrogen Distribution in the Loess Plateau of China. Agricultural Water Management. 2018, 203, 277–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Jiang, C.; Ma, R.; Gao, W.; Shou, N.; Shen, Y.; Yang, X. Suitability of Five Forage Sweet Sorghum Varieties for Production in the Dry Plateau Area of Longdong. Acta Prataculturae Sinica. 2024, 33, 50–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Zhang, K.; Zhou, T.; Hu, Y.; Sun, X.; Li, K. Characteristics of Moth Community in Different Types of Urban Forest Planta Tions in Beijing. Chinese Journal of Ecology. 2022, 41, 316–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Xue, D. Insecta.Vol.54,Lepidoptera,Geometridae; Science Press: Beijing, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Shannon, C.E.; Weaver, W.; Wiener, N. The Mathematical Theory of Communication. Physics Today. 1950, 3, 31–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, A. Perspectives in Ecological Theory; Princeton University Press, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Simpson, E.H. Measurement of Diversity. Nature. 1949, 163, 688–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pielou, E.C. An Introduction to Mathematical Ecology. Bioscience. 2011, 24, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, E.P. Niche Breadth, Resource Availability, and Inference. Ecology. 1982, 63, 1675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandit, S.N.; Kolasa, J.; Cottenie, K. Contrasts between Habitat Generalists and Specialists: An Empirical Extension to the Basic Metacommunity Framework. Ecology. 2009, 90, 2253–2262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pianka, E.R. The Structure of Lizard Communities. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 1973, 4, 53–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Hu, X.; Li, M.; Liu, J.; Tang, M.; Liu, W.; Zhan, J.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, W. Diet Composition and Interspecific Niche of Taohongling Sika Deer (Cervus Nippon Kopschi) and Its Sympatric Reeve’s Muntjac (Muntiacus Reevesi) and Chinese Hare (Lepus Sinensis) in Winter (Animalia, Mammalia). ZK. 2023, 1149, 17–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dang, R.; Xu, S.; Qi, L. Analysis of Moth Insect Diversity in Ziwuling National Nature Reserve, Shaanxi Province. In Proceedings of the Compilation of the 8th Western China Zoology Academic Symposium, Guizhou, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Heppner, J.B. Butterflies and Moths (Lepidoptera). In Encyclopedia of Entomology; Springer: Dordrecht, 2008; pp. 626–672. [Google Scholar]

- Sutrisno, H. Moth Diversity at Gunung Halimun-Salak National Park, West Java. HAYATI Journal of Biosciences. 2008, 15, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, D.; Yuan, J.; Ding, J.; Li, J.; Zhang, H. The Complete Mitochondrial Genome of Semiothisa Cinerearia Bremer & Grey 1853 (Lepidoptera: Geometridae: Ennominae) and Its Phylogenetic Analysis. Mitochondrial DNA Part B. 2023, 8, 1248–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonason, D.; Franzén, M.; Ranius, T. Surveying Moths Using Light Traps: Effects of Weather and Time of Year. PLoS ONE. 2014, 9, e92453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holyoak, M.; Jarosik, V.; Novák, I. Weather-induced Changes in Moth Activity Bias Measurement of Long-term Population Dynamics from Light Trap Samples. Entomologia Exp Applicata. 1997, 83, 329–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhao, R.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, G.; Zhang, F. Prediction of Potential Distribution Areas and Priority Protected Areas of Agastache Rugosa Based on Maxent Model and Marxan Model. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1200796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, P.; Cheng, J.; Hu, J.; Jing, Y.; Wang, J.; Yang, H.; Ding, X.; Yan, X. Quercus Wutaishanica Shrub Affects Temperate Forest Community Composition and Soil Properties under Different Restoration Stage. PLoS ONE. 2023, 18, e0294159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, R.; Gong, X.; Feng, J.; Yang, R. Niche and Range Dynamics of Tasmanian Blue Gum ( Eucalyptus Globulus Labill.), a Globally Cultivated Invasive Tree. Ecology and Evolution. 2022, 12, e9305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Zou, X.; Wang, D.; Wan, S.; Wang, L.; Guo, J. Responses of Community-Level Plant-Insect Interactions to Climate Warming in a Meadow Steppe. Sci Rep 2015, 5, 18654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khabir, M.; Izadi, H.; Mahdian, K. The Supercooling Point Depression Is the Leading Cold Tolerance Strategy for the Variegated Ladybug, [Hippodamia Variegata (Goezel)]. Front. Physiol. 2023, 14, 1323701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, L.; He, H.; Huang, L.; Geng, T.; Fu, S.; Xue, F. Variation of Life-history Traits of the Asian Corn Borer, Ostrinia Furnacalis in Relation to Temperature and Geographical Latitude. Ecology and Evolution. 2016, 6, 5129–5143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagata, K.; Gibb, H. The Effect of Temperature Increases on an Ant-Hemiptera-Plant Interaction. PLoS ONE. 2016, 11, e0155131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maharjan, R.; Hong, S.; Yoon, Y.; Jang, Y.; Park, K. Temperature and Relative Humidity Mediated Life Processes of Spodoptera Species (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). Bull. Entomol. Res. 2024, 114, 606–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, X.; Wang, X.; Li, P.; Peng, P. Research Progress on the Effects of Several Enviromental Factors on Adaptability of Insects. Chinese Agricultural Science Bulletin. 2015, 31, 79–82, doi:CNKI:SUN:ZNTB.0.2015-14-014. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, D.; Xu, C.; Yin, L.; Zhang, S.; Liu, X. Effects of Ecological Factors on Mating and Reproduction in Moths. Journal of Environmental Entomology. 2017, 39, 963–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |